Introduction: The Storage Problem We've Been Ignoring

Your phone probably has somewhere around 128 gigabytes of storage. Maybe more. But here's the uncomfortable truth: it'll be mostly unusable in a decade. Hard drives degrade. Flash memory loses charge. Data centers consume enough electricity to power small countries. We've optimized for speed and density, but we've completely botched durability.

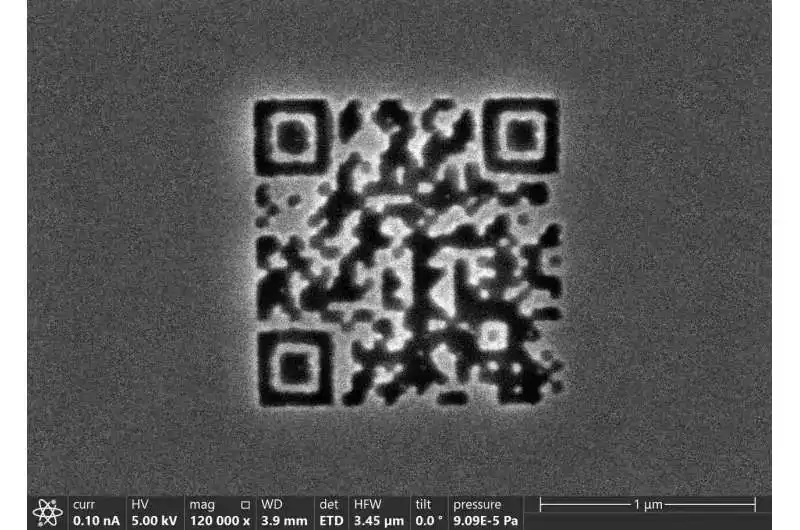

That's why a tiny ceramic disk with a microscopic QR code etched into it might actually represent the most important breakthrough in data storage in the past twenty years.

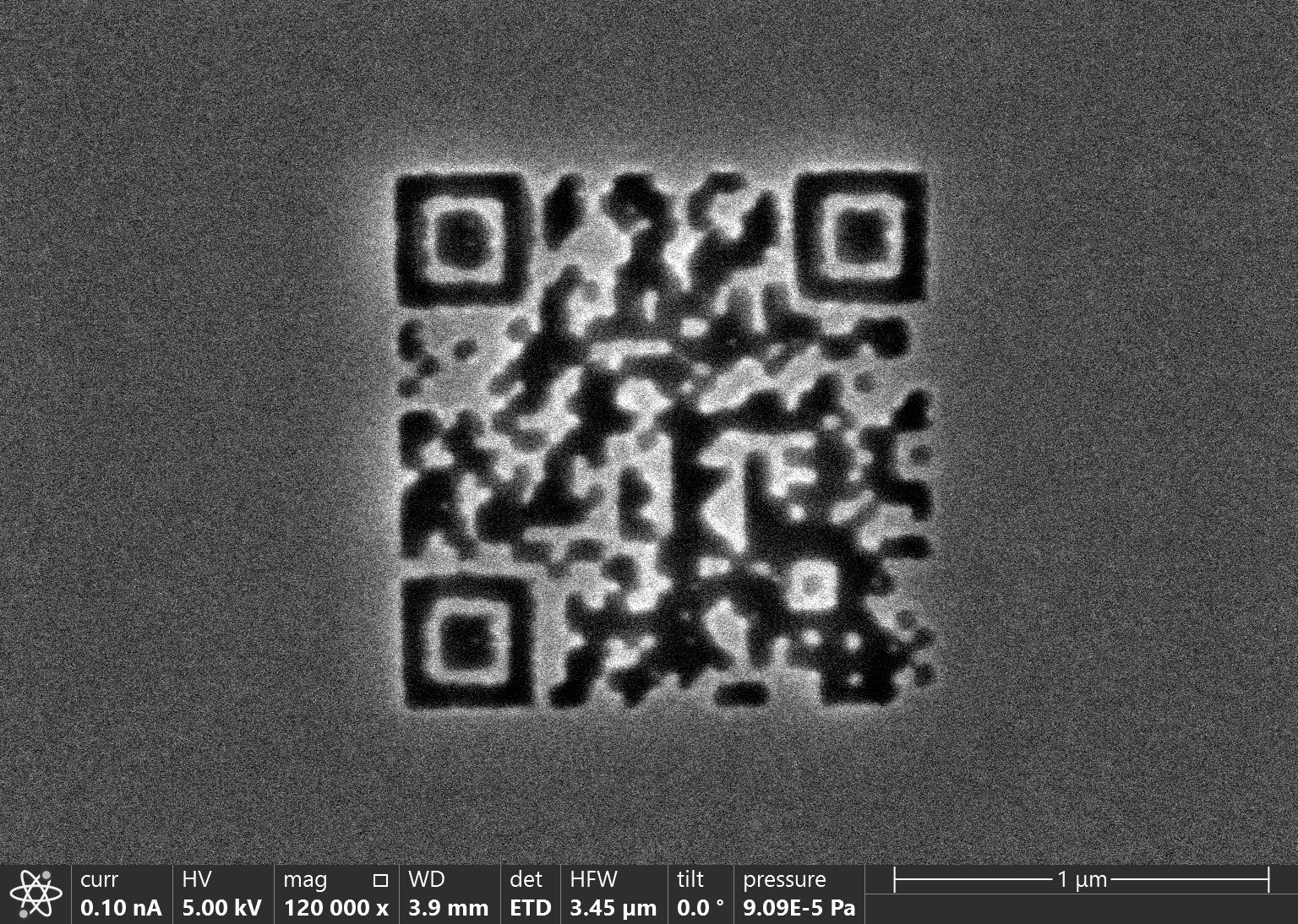

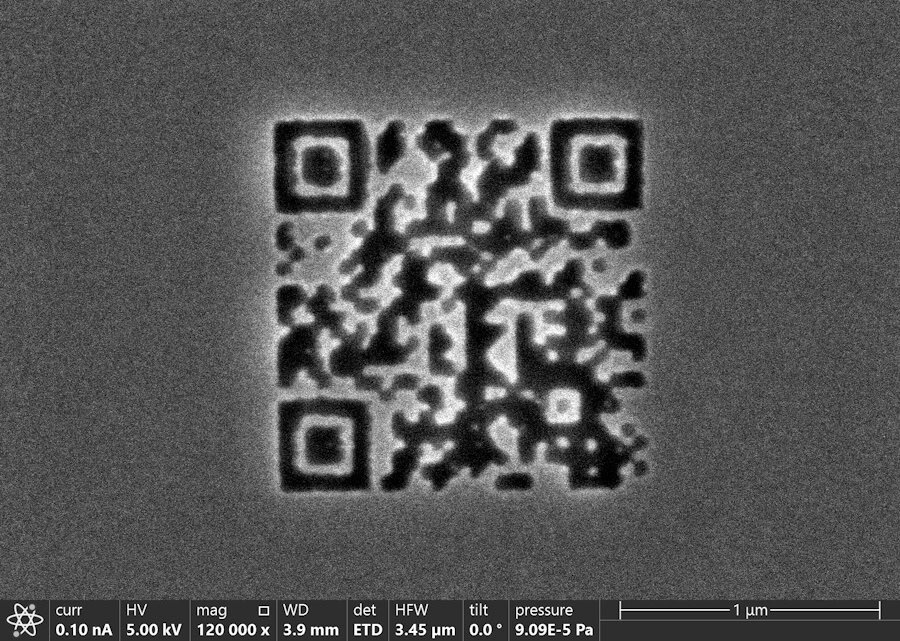

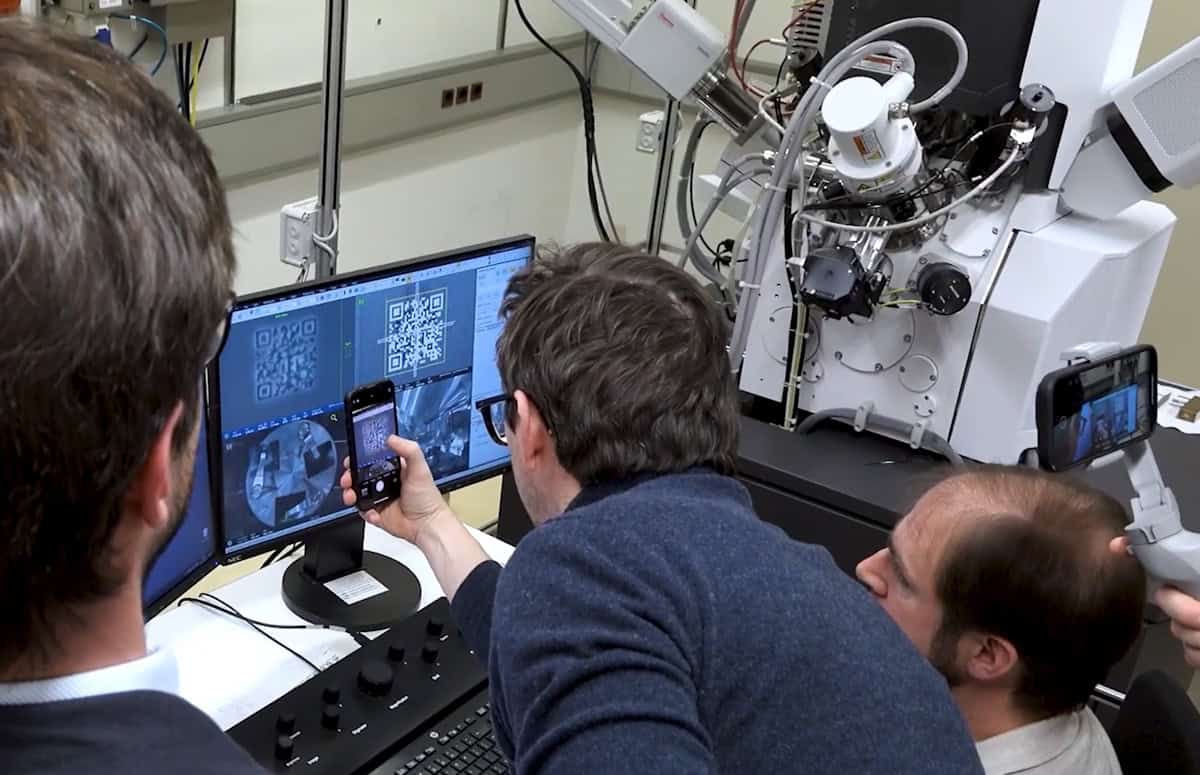

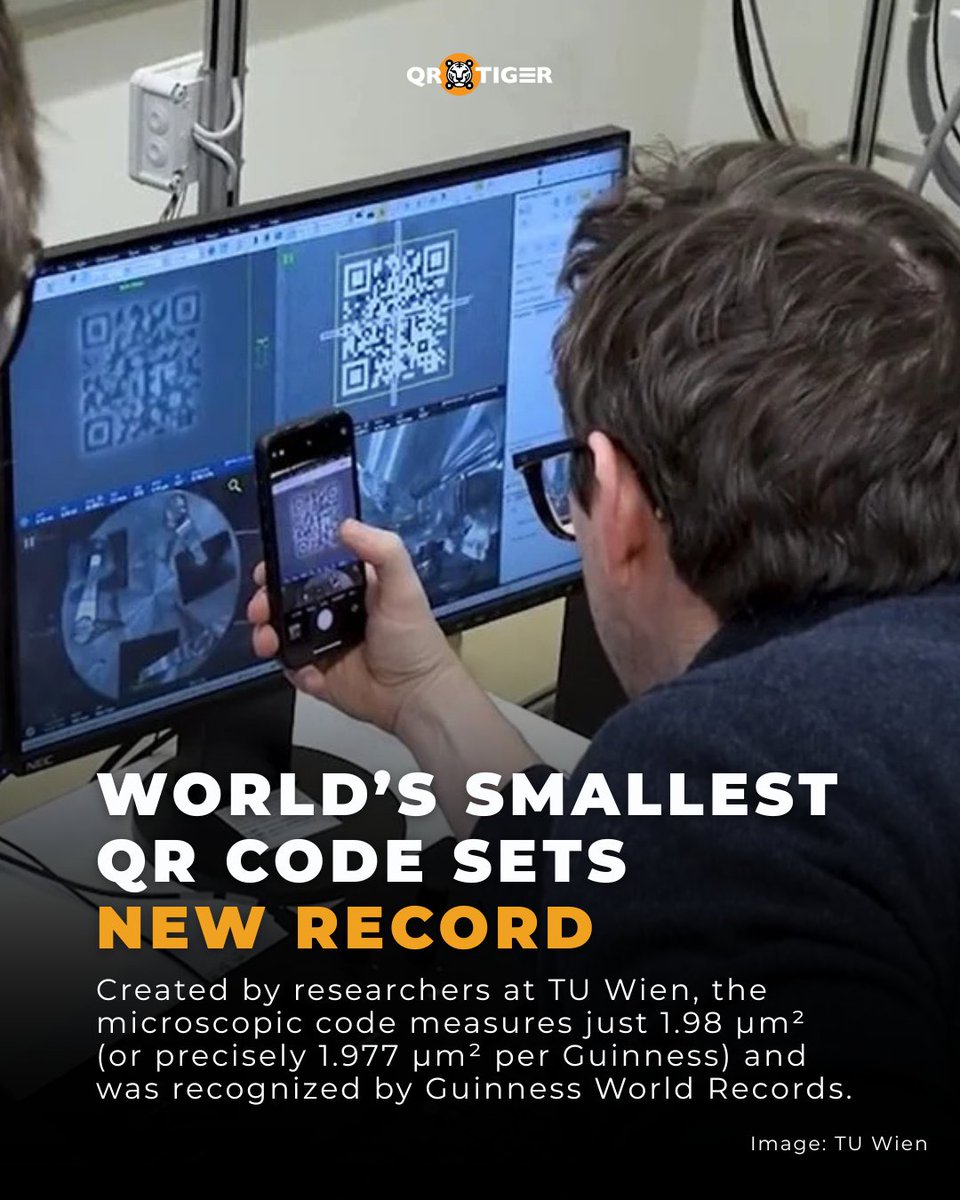

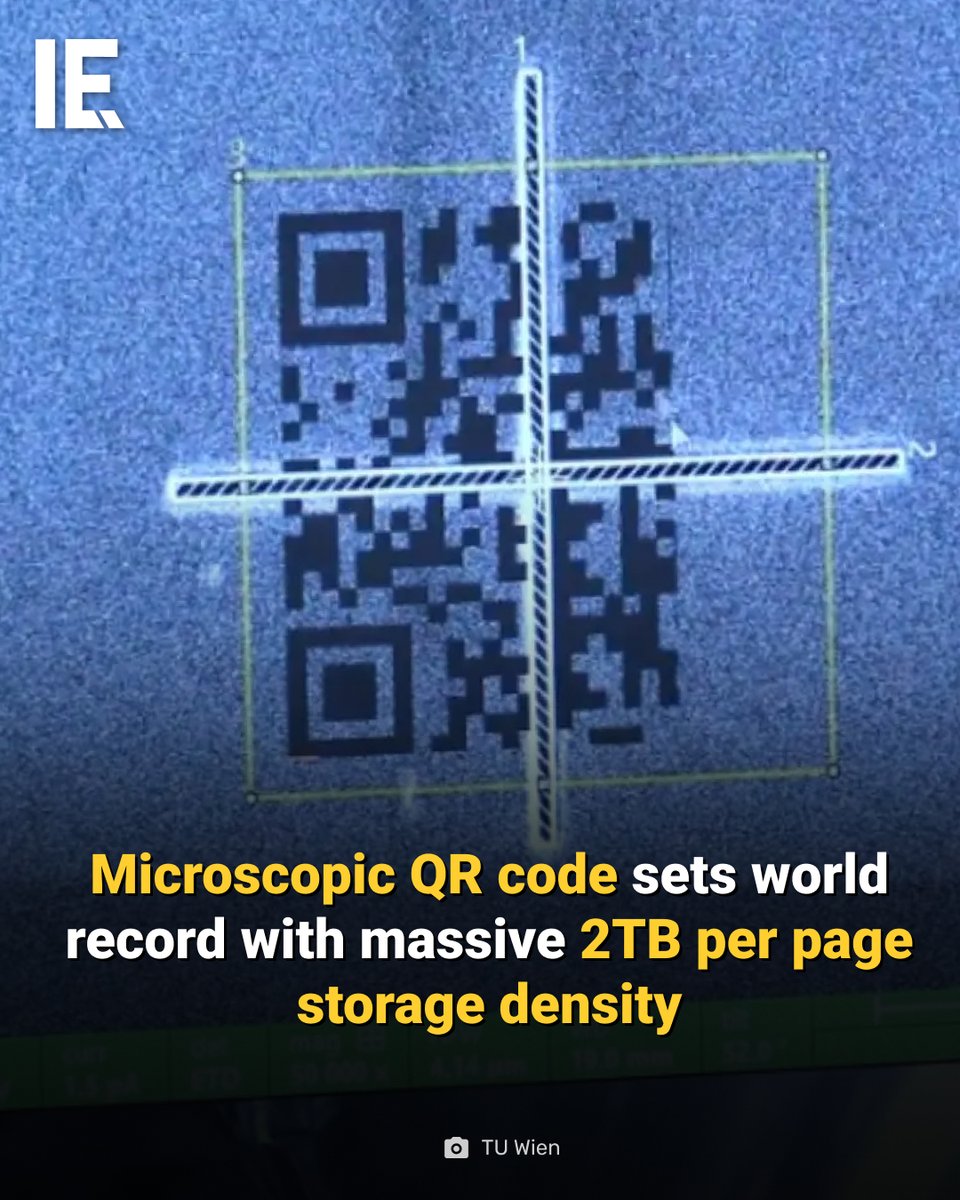

In 2025, researchers at TU Wien and Cerabyte achieved something that sounds like science fiction: they created and successfully read QR codes with pixels measuring just 49 nanometers. To give you scale, that's roughly 1/2000th the width of a human hair. These codes are so small they require an electron microscope to read. They're also so efficient that a single A4-sized ceramic layer could theoretically hold more than 2 terabytes of data. And here's the kicker: once the data is written, it requires zero power, zero cooling, and zero maintenance to preserve indefinitely.

This isn't just about breaking records. It's about fundamentally rethinking how humanity stores information for the long term. While cloud providers spend billions keeping servers cool, while enterprises struggle with data center sustainability, while governments debate how to preserve digital heritage for future generations, these researchers cracked something that's been theoretically possible but practically impossible: indefinite storage that costs almost nothing to maintain.

The implications ripple across industries. Archives could preserve centuries of digital history in a shoebox. Enterprises could slash infrastructure costs and carbon footprint simultaneously. Governments could create permanent records that survive political upheaval, natural disasters, and technological obsolescence. The research is real. The record is verified. But the journey from laboratory breakthrough to practical reality is just beginning.

Let's dig into what's happening, why it matters, and whether this actually changes everything or remains locked in the research world.

TL; DR

- Record-breaking density: 49-nanometer QR code pixels are 37% smaller than the previous record, storing over 2TB per A4 ceramic layer

- Zero-power storage: Ceramic media requires no electricity, cooling, or environmental control after initial write, enabling indefinite preservation

- Electron microscope required: Codes are smaller than bacteria and cannot be read with standard optical tools, requiring specialized equipment

- Commercial development underway: Cerabyte is working toward manufacturing scalability with Western Digital as an investor

- Timeline to commercialization: Practical systems likely 3-5 years away, pending manufacturing breakthroughs and read speed optimization

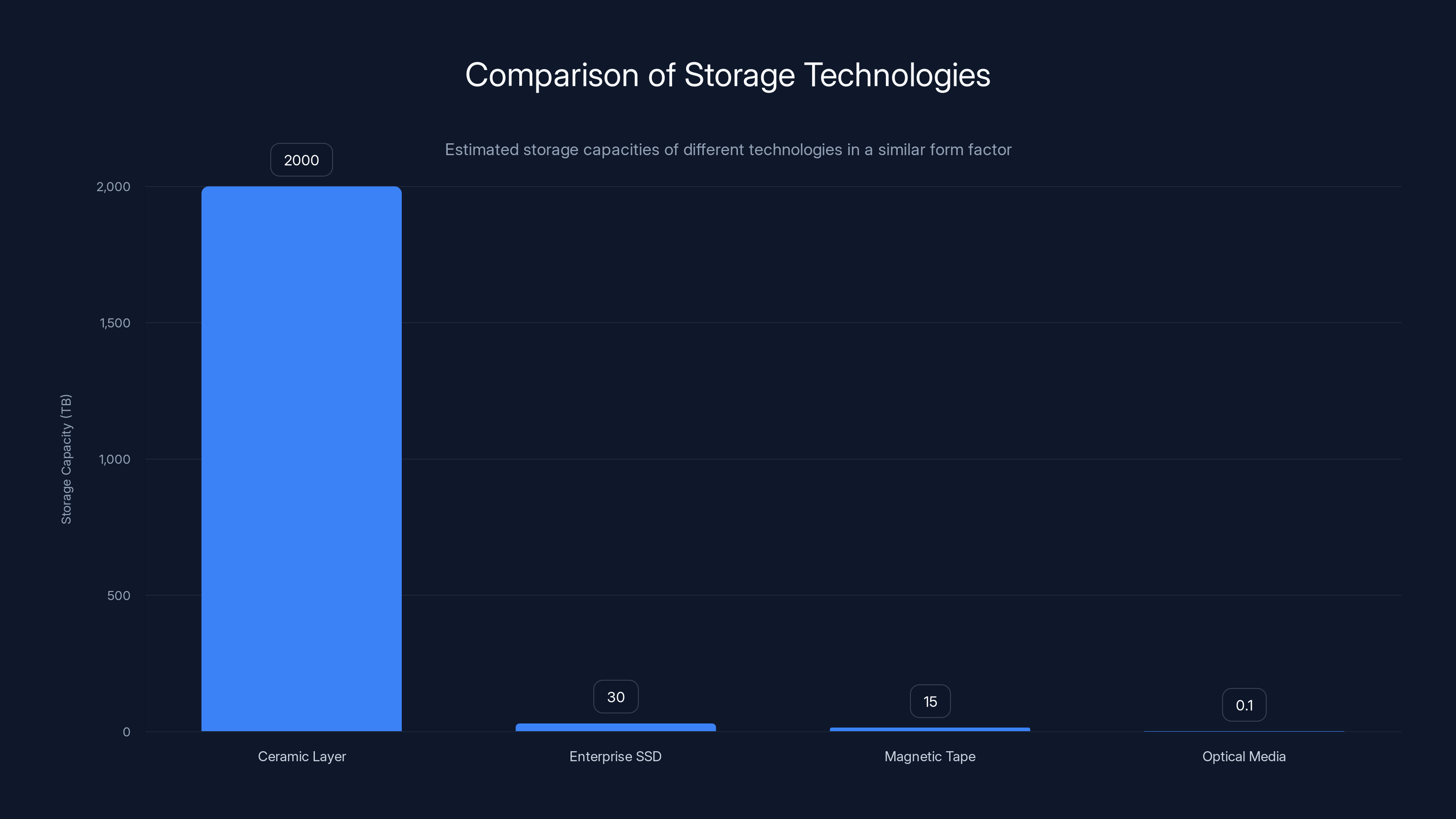

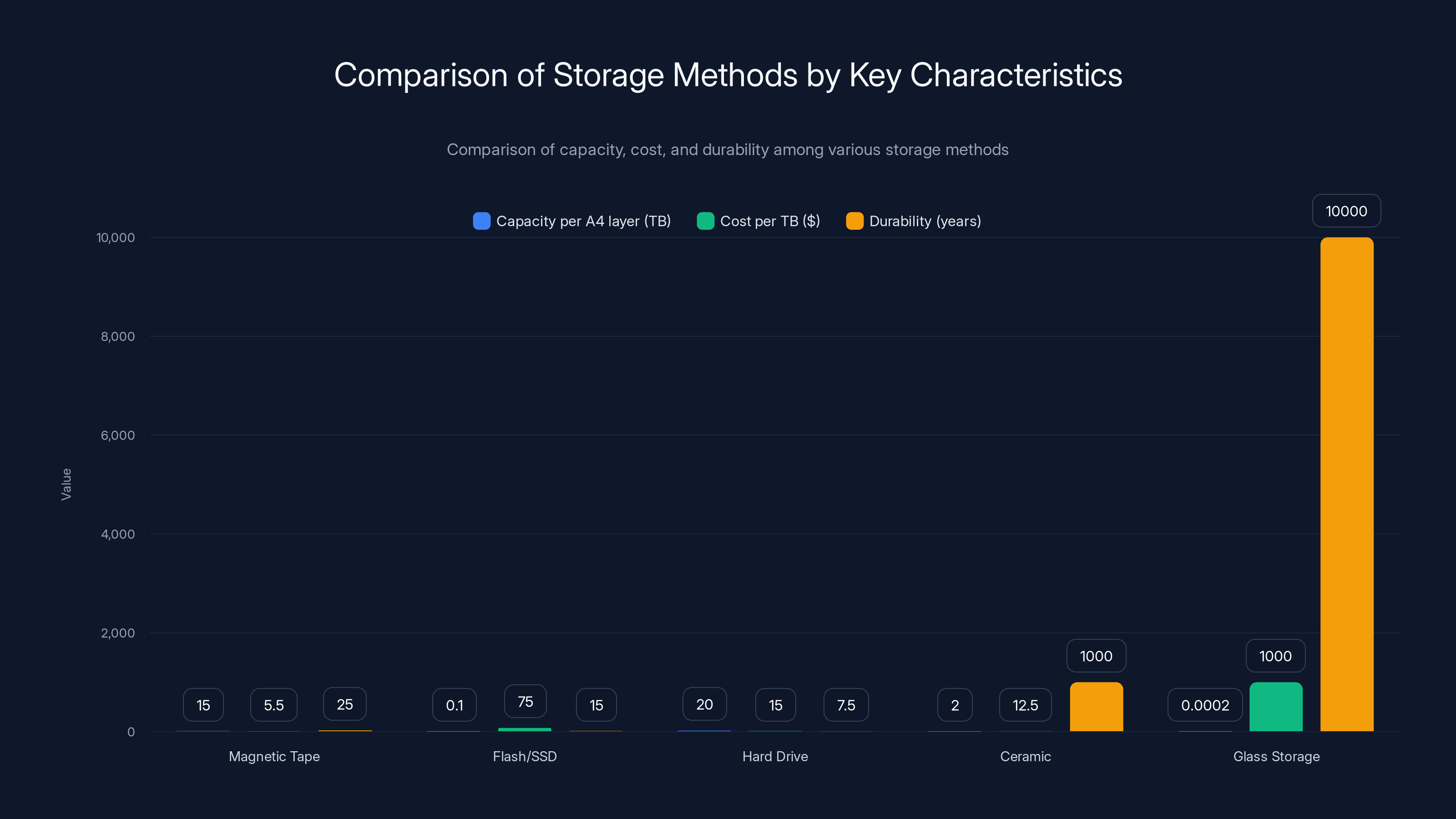

Ceramic storage offers significantly higher data density, achieving up to 2000TB in a compact form, surpassing traditional storage technologies. Estimated data based on theoretical calculations.

Understanding the Technology: How Nanometer Storage Actually Works

The Physics of Microscopic QR Codes

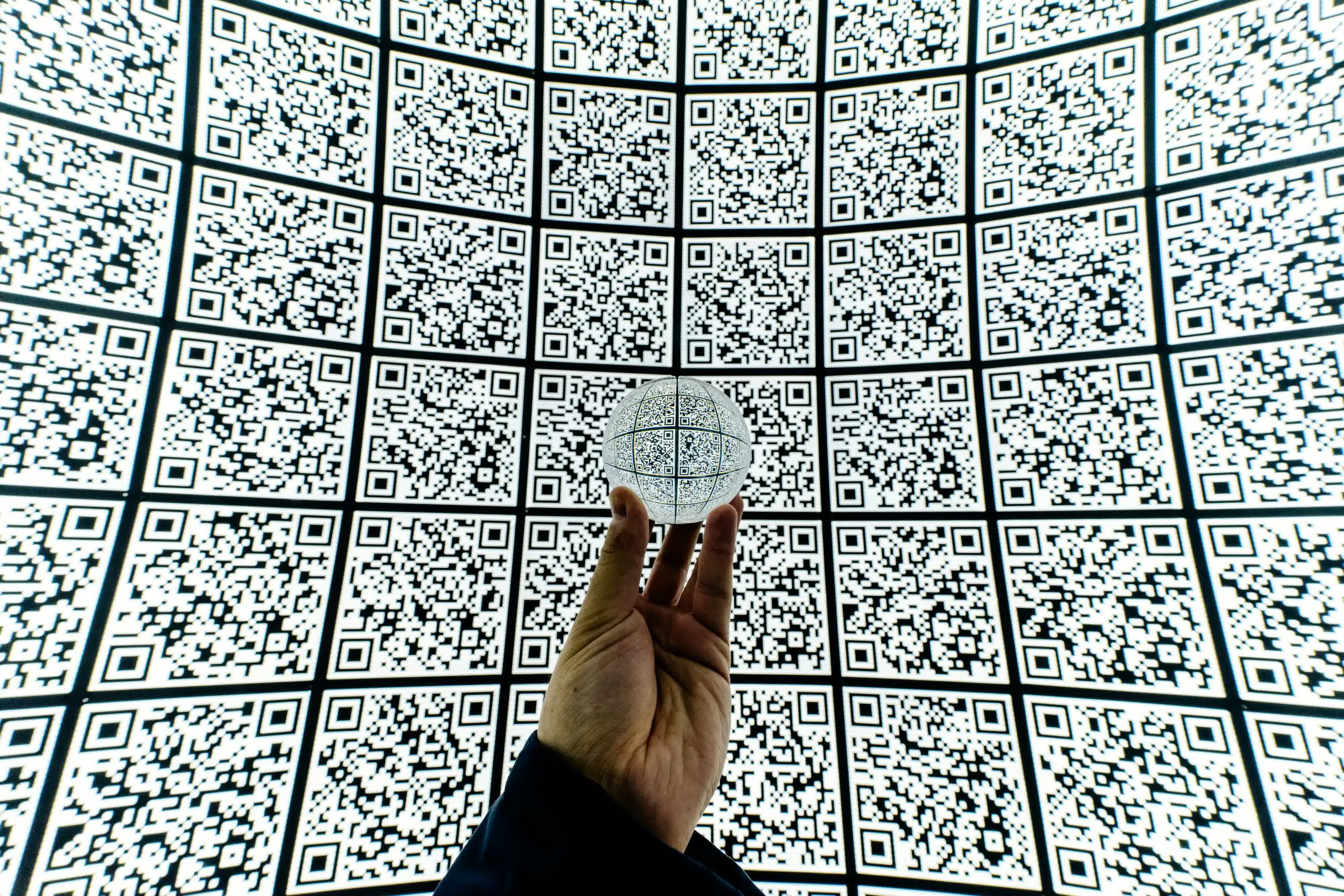

QR codes are conceptually simple: a grid of black and white squares encoding information. Scale one down to readable proportions and you've just made storage more efficient. Scale it down to 49 nanometers per pixel and you've entered a completely different territory.

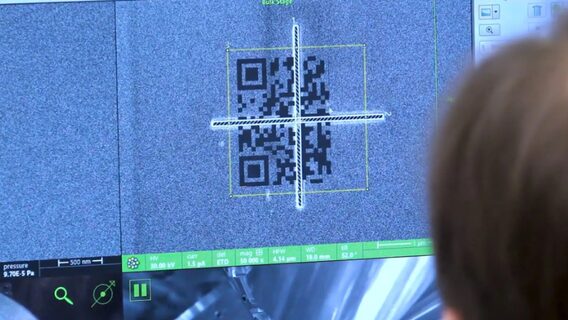

At this scale, individual pixels are smaller than the wavelength of visible light. You can't see them. A standard optical scanner designed for QR codes won't even detect them. Instead, researchers use an electron microscope, which bombards the ceramic surface with electrons and detects how they scatter or reflect, creating an image at nanometer resolution.

The encoding logic remains identical to standard QR codes. Error correction still works. Data integrity remains intact. The only difference is you need industrial equipment to read it.

This creates an interesting technological asymmetry: writing is complex (requires electron beam nanofabrication), but reading becomes pure physics. An electron microscope is expensive, sure, but it's not a custom instrument. It's research-grade equipment that already exists in thousands of labs and industrial facilities worldwide.

Why Ceramic Is the Answer to Permanent Storage

Hard drives use spinning platters coated with magnetic material. Flash memory relies on trapped electrons in silicon gates. Both degrade. Magnetic material magnetization weakens. Electrons leak away over time, especially at higher temperatures. Both technologies require active power to maintain data integrity.

Ceramic works differently. When researchers mill nanoscale structures into ceramic material, they're literally carving data into stone (well, engineered ceramic). There's no magnetic field to decay. There's no charge to dissipate. The atoms don't spontaneously move. Unlike paper that yellows, unlike magnetic tape that flakes, ceramic endures.

Consider the analogy: ancient civilizations carved important information into stone tablets. That data sometimes survived thousands of years. Not because of clever engineering, but because stone simply doesn't degrade like biological or electronic materials do. Ceramic storage applies that same principle at nanometer scale with modern precision.

The ceramic substrate used by TU Wien and Cerabyte is specifically engineered for data retention. Different ceramic formulations have different properties. Some are more scratch-resistant. Some resist thermal stress better. The research team selected compositions optimized for data stability, which is why durability predictions stretch to "indefinite" without much hedging.

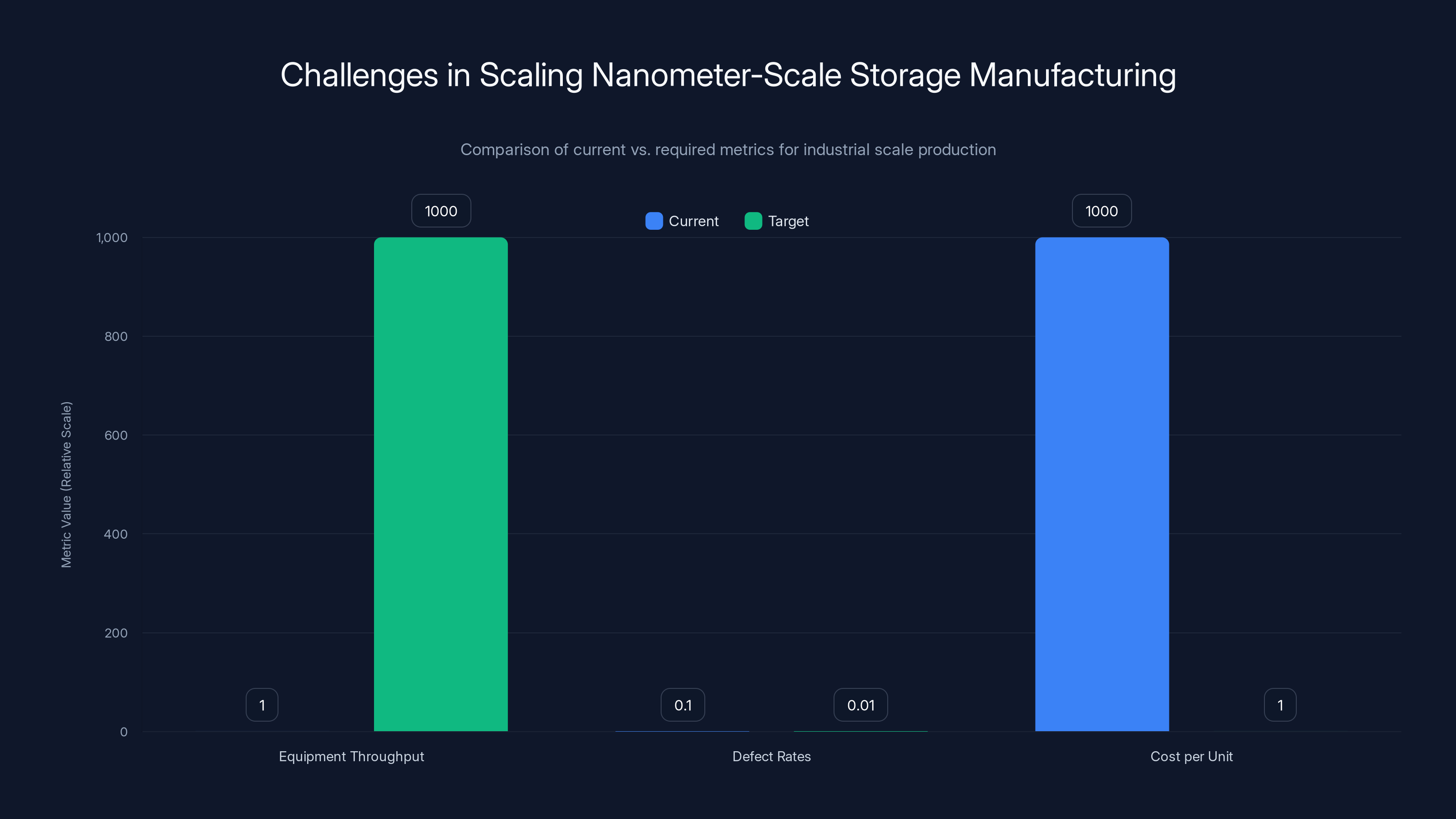

The Manufacturing Challenge: From Research to Reality

Here's where enthusiasm hits practical reality. Creating a single record-breaking QR code in a laboratory is one thing. Manufacturing thousands, millions, or billions of them at consistent quality is another dimension entirely.

The current process involves using electron beam lithography or similar techniques to mill nanoscale patterns into ceramic. These are not fast processes. They're not cheap processes. A single 49-nanometer QR code takes time and precision equipment to create. Scaling this to industrial volumes while maintaining quality is the actual hard problem.

Cerabyte's stated goal is reaching 500GB proof-of-concept systems in 2026. That's a significant engineering jump from single codes to practical storage media. They'll need to solve:

- Write speed optimization: How quickly can bulk data be transferred to ceramic without introducing errors?

- Manufacturing scalability: Can electron beam lithography be industrialized, or does a different writing mechanism emerge?

- Cost reduction: Research equipment costs thousands per code. Commercial systems need per-unit costs measured in dollars, not kilobucks.

- Error handling: What happens when a write fails mid-process? Can recovery happen automatically?

- Data access protocols: Is every read destructive? Can the same ceramic be read repeatedly?

Western Digital's investment signals commercial interest, but investment doesn't equal solved problems. The company is hedging its bets across multiple storage technologies simultaneously.

To achieve industrial scale production, equipment throughput must increase 1000x, defect rates must decrease to below 0.01%, and cost per unit must reduce by 1000x. Estimated data based on industry targets.

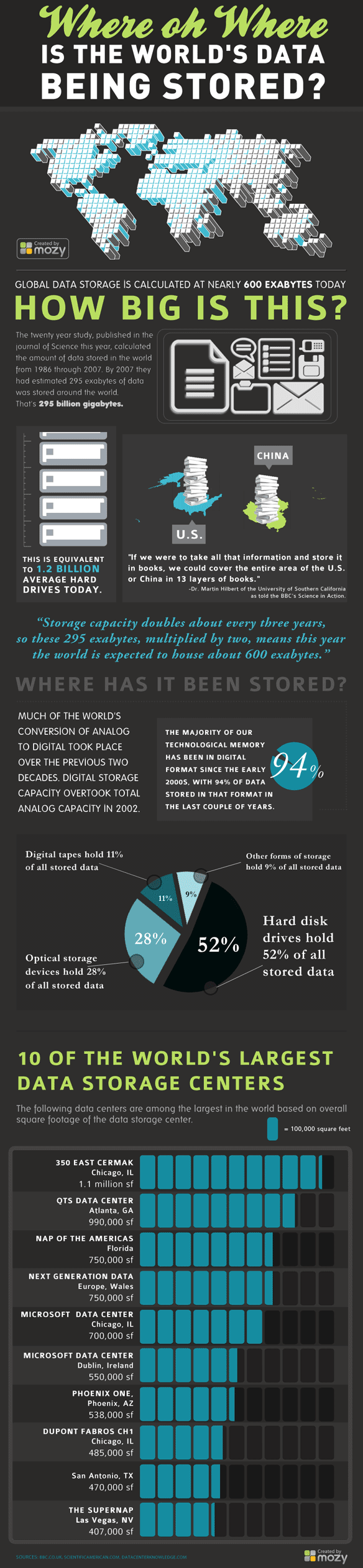

The Storage Landscape Before This Breakthrough

Existing Long-Term Storage Methods and Their Limitations

What do enterprises use today when they need data to last decades?

Magnetic Tape remains the dominant archival medium. It's cheap. It's relatively durable. Data centers worldwide maintain tape archives for compliance, disaster recovery, and cold storage. The problem: magnetic tape needs environmental control (temperature, humidity), occasional refresh cycles to ensure magnetization hasn't degraded, and replacement every 20-30 years. It's not indefinite. It requires active management.

Hard Disk Drives suffer from mechanical failure rates, thermal stress degradation, and firmware obsolescence. A drive manufactured in 2005 might not work in 2025 because the interface became obsolete. Even if it spins, the data encoding might not be readable by modern systems.

Flash Memory and SSDs are faster than tape but degrade through electron trap mechanisms. Without power, electrons slowly escape. With power, they escape more slowly but eventually. Specifications talk about "10-20 year retention" which is optimistic under perfect conditions.

Optical Media (DVDs, Blu-rays) promised longevity. The reality is more complicated. Polycarbonate substrate degrades. Dye layers fade. Recordable media is worse than pressed media. The Blu-ray Disc Association claims 100-year longevity, but real-world data suggests 20-30 years for consumer media is more realistic.

Cloud Storage trades physical durability for provider dependency. Your data survives hardware failures because it's replicated. But what happens when the company goes bankrupt? When regulatory changes occur? When geopolitical events disrupt operations? You don't actually own the storage; you rent it.

Each method has painful trade-offs. Durability versus cost. Accessibility versus permanence. Speed versus energy efficiency.

Project Silica and Competing Approaches

Microsoft's Project Silica, developed with Microsoft Research, takes a different approach: encoding data in glass using femtosecond laser pulses. The technique stores information in three-dimensional patterns within glass, theoretically lasting thousands of years without degradation or power consumption.

Project Silica demonstrated storing 200MB of data on a glass disc the size of a sugar cube. Durability predictions suggest the glass could survive 10,000 years, potentially outlasting human civilization. Microsoft positioned it for long-term archival of important cultural data.

However, Project Silica faces significant hurdles: reading speed is slow, writing is extremely slow, and scaling to commercial production remains unsolved. The research is sound, but practical deployment is years away.

Ceramic storage and glass storage aren't competitors so much as complementary technologies for different use cases. Glass might excel for truly permanent archival (centuries+). Ceramic might optimize for balance: reasonable capacity, faster access, industrial scalability.

The 49-Nanometer Achievement: Breaking Down the Record

What Makes This Specific Record Significant

TU Wien and Cerabyte's 49-nanometer QR code pixels represent a 37% size reduction compared to the previous record holder. That might sound incremental until you consider information density mathematics.

With linear reduction of 37%, area reduction is proportional to the square of the linear dimension. A 37% linear reduction means roughly 60% reduction in pixel area. If you can fit more data in the same physical space, you've fundamentally changed the economics of storage.

A single A4-sized (210×297mm) ceramic layer with 49-nanometer pixels can theoretically store over 2 terabytes. Compare that to:

- Modern enterprise SSDs: 15-30TB in a 3.5-inch form factor, but requiring power and maintenance

- Magnetic tape cartridges: 15TB in a larger physical package, requiring environmental control

- Optical media: 100GB maximum in a 12cm disc, requiring mechanical reading

Ceramic storage wins on three fronts simultaneously: higher density than tape, no power requirement like tape, and theoretical longevity exceeding everything.

Pixel Size and Information Density Calculations

Let's work through the math. A 49-nanometer pixel represents:

Convert to micrometers for practical thinking:

For an A4 ceramic layer (210mm × 297mm = 62,370mm²):

If each pixel represents one bit (binary 0 or 1), that's roughly 2.6 exabits, or about 325 exabytes of raw storage capacity. Real QR codes use error correction, redundancy, and address overhead, reducing effective capacity to perhaps 5-10%, but even that yields petabyte-scale storage from a single layer.

The 2TB figure mentioned in research represents a conservative estimate accounting for error correction, address space, and practical limitations. This isn't theoretical maximum; it's engineered capacity.

Reading Process and Limitations

Reading these nanometer-scale QR codes requires an electron microscope. Specifically, a scanning electron microscope (SEM) that can resolve features at 10-50 nanometer scale. These instruments exist in thousands of locations: research universities, semiconductor fabrication facilities, materials science labs, quality control departments.

SEMs aren't portable or consumer-grade, but they're not exotic either. A decent SEM costs

The reading process works like this:

- Insert ceramic storage media into the SEM chamber

- Bombard the surface with electrons at controlled intensity

- Detect backscattered or secondary electrons

- Software reconstructs the surface topology from electron patterns

- Image processing identifies black and white pixels of the QR code

- Standard QR decoding algorithms extract the data

This process is non-destructive. The ceramic surface isn't damaged by reading. Theoretically, the same media can be read millions of times without degradation.

Speed is the limitation. An electron microscope scan producing an image of a nanometer-scale structure takes time. Reading a single 2TB ceramic layer might require hours, not minutes. This makes ceramic storage ideal for archival (write once, read rarely) but impractical for active databases or frequently accessed data.

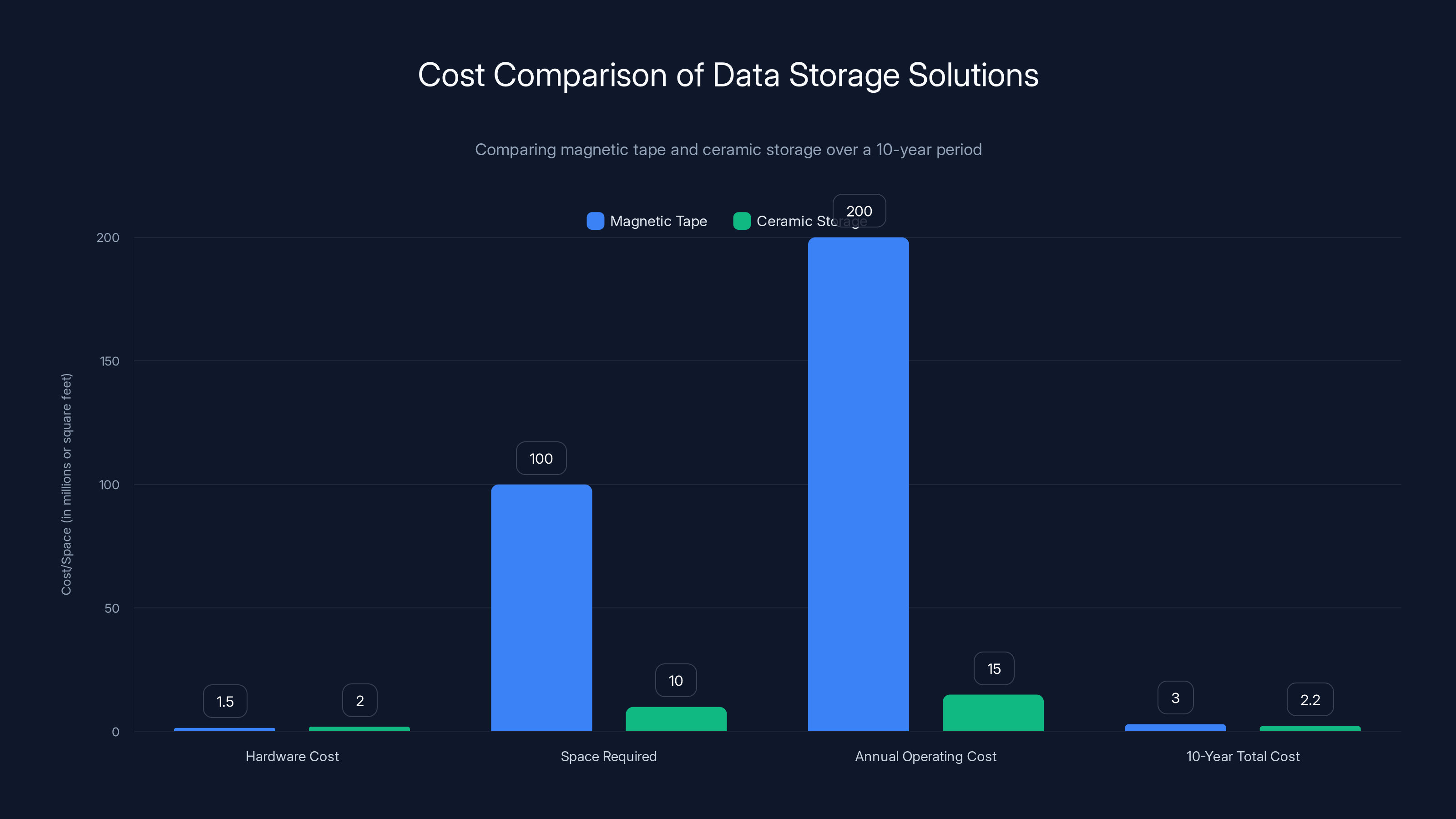

Ceramic storage shows a higher initial hardware cost but significantly lower space and operating costs, leading to a lower total cost over 10 years. Estimated data for ceramic storage.

Why This Matters: The Durability Problem We Haven't Solved

The Hidden Cost of Data Center Energy Consumption

Data centers globally consume roughly 3-4% of worldwide electricity. That's about 1,000 terawatt-hours annually. For context, that's more electricity than Japan uses in a year.

Most of that energy goes to three things: powering servers (compute), cooling systems (removing heat), and storage devices (spinning disks, maintaining flash charge). A typical data center spends 20-30% of operating costs on electricity alone.

Now consider archival workloads. A company needs to preserve financial records for seven years (regulatory requirement). Need to keep customer data for compliance. Need to maintain backups of backups. This data is rarely accessed. It just sits there, consuming electricity, generating heat, requiring cooling infrastructure.

With ceramic storage, you write the data once, then remove power. The data persists indefinitely without electrical input. The economic impact would be significant. Imagine reducing data center electricity by 10-20% through better handling of archival workloads.

Technological Obsolescence and Format Preservation

Here's a problem that doesn't get enough attention: your data might be intact, but you can't read it because the format is obsolete.

Consider floppy disks from the 1980s. The media probably still stores data correctly. But finding a working 3.5-inch floppy drive is harder every year. Finding one that connects to modern computers? Nearly impossible. The format became obsolete before the physical media degraded.

This happened with:

- Betamax tape: Superior in many ways to VHS, but lost the format wars

- Zip drives: Once widespread, now completely absent

- Sony Memory Stick: Specialized format that disappeared

- Early flash drives: Non-standard connectors, formats that modern systems don't recognize

Ceramic storage sidesteps this through QR code standardization. QR codes have been standardized since the 1990s. The decoding algorithm is simple, well-documented, and mathematically trivial. A QR decoder written in 2025 will read QR codes the same way a decoder written in 2050 will (assuming the humans still understand basic mathematics).

This isn't guaranteed, but it's more probable than proprietary formats surviving a century unchanged.

Government and Institutional Need for Permanent Records

Governments and cultural institutions have a problem: how do you preserve information for centuries without knowing what technology will exist in the future?

The Library of Congress, national archives, and UNESCO all grapple with this. Digital preservation requires active maintenance. Systems require replacement. Formats require migration. It's expensive, it's ongoing, and it's fragile.

Ceramic storage offers a different model: write important documents, scientific data, cultural records to ceramic, and trust that the atomic structure will outlast human civilization. The cost of reading equipment (scanning electron microscopes) is trivial compared to maintaining active digital preservation systems.

Countries like Denmark, Germany, and the UK have explored ceramic storage for long-term record keeping. The technical capabilities are there; the scaling problem is what remains.

Manufacturing at Scale: The Real Challenge Ahead

Current Production Bottlenecks

Laboratory demonstrations of nanometer-scale storage use electron beam lithography, a process where a focused beam of electrons writes patterns directly onto the material. It's precise. It works. It's also slow, expensive, and designed for research quantities (dozens of devices), not industrial volumes (millions).

To move from lab to factory, Cerabyte needs to overcome several engineering challenges:

Equipment Throughput: Electron beam lithography tools typically write a few square centimeters per hour. To produce even one ceramic storage layer per day at industrial scale requires 100-1000 times higher throughput. This might mean developing entirely new writing mechanisms, or discovering optical/mechanical alternatives that can achieve similar precision.

Defect Rates: Manufacturing at nanometer scale means any imperfection ruins the device. Dust particles, vibration, thermal drift all introduce defects. A 99.9% success rate sounds good until you realize that 0.1% defect rate means scrapping thousands of devices daily. Industrial processes need defect rates below 0.01% to be economical.

Cost per Unit: Current research processes cost thousands of dollars per storage device. Commercial viability requires cost reduction to dollars per terabyte, matching or beating magnetic tape and flash memory economics. This is a 1,000x improvement target.

Material Consistency: Different batches of ceramic might have slightly different properties. Manufacturing needs to maintain consistency across sources, suppliers, and production runs spanning years.

Alternative Writing Mechanisms Under Exploration

Electron beam lithography probably won't be the final manufacturing technique. Researchers are exploring alternatives:

Femtosecond Laser Inscription: Using ultrafast laser pulses to create nanoscale features directly in ceramic without etching. Faster than electron beams, potentially more scalable.

Nanoimprint Lithography: Creating a template pattern, then stamping it into material like a printing press. Once the template exists, replication becomes fast and cheap.

Ion Beam Milling: Using focused ion beams instead of electrons. Different physics, potentially different performance characteristics and manufacturing implications.

Directed Self-Assembly: Materials that automatically organize into desired patterns under specific conditions. This would be the most scalable approach if achievable, as it requires no precision tool movement, just chemical processes.

Cerabyte hasn't publicly detailed which approach they're pursuing, but the diversity of research indicates no single obvious winner yet. Manufacturing will likely involve breakthrough discoveries in precision engineering, not incremental improvements to existing processes.

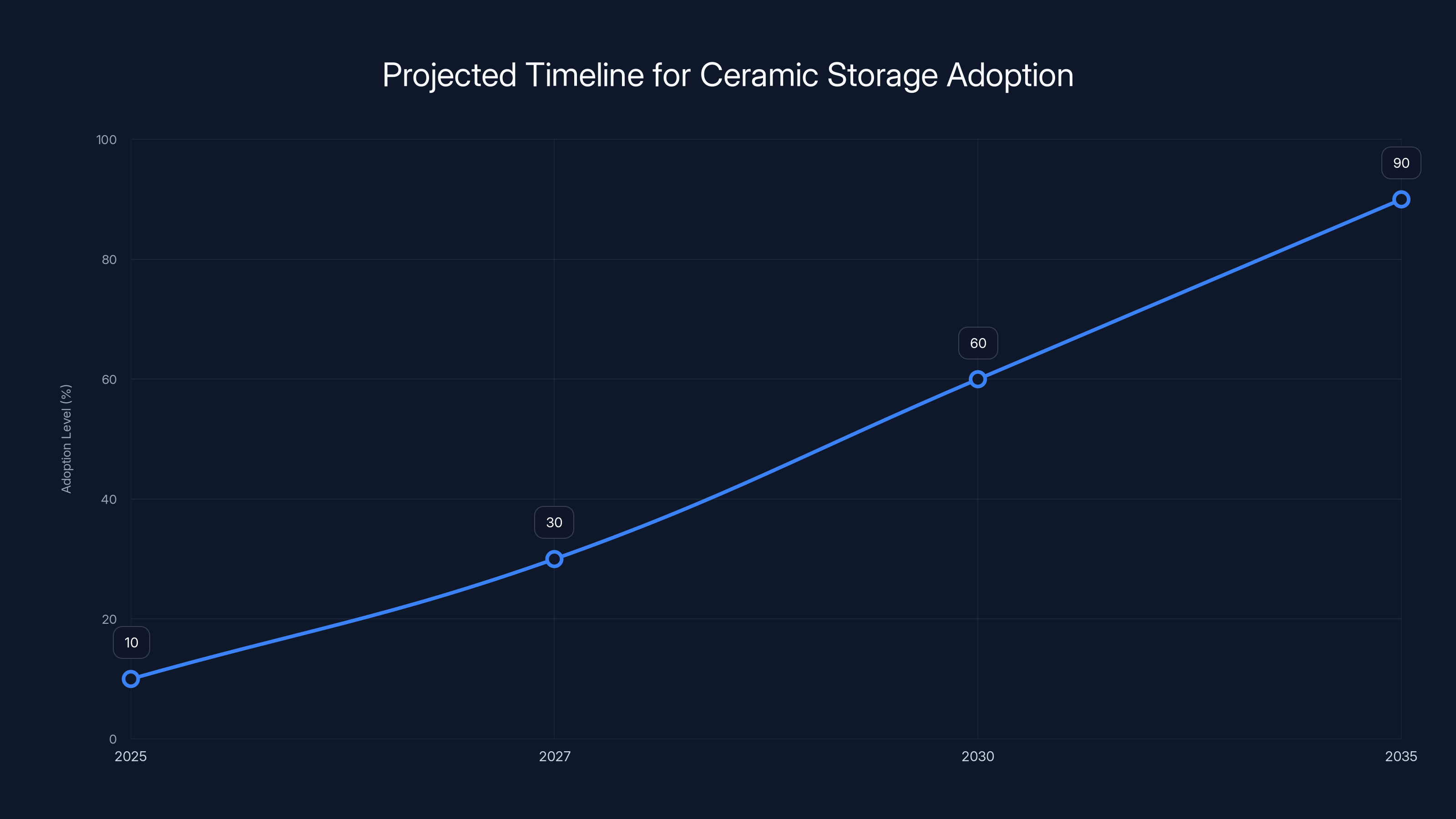

Timeline to Commercial Viability

Cerabyte's public timeline targets 500GB proof-of-concept systems in 2026. This would be a significant milestone: a practical device, not just a laboratory record, with meaningful capacity.

However, proof-of-concept and commercial viability are different. A 500GB proof-of-concept might demonstrate technical feasibility while still operating at research costs and volumes. Commercial viability requires:

- Consistent production: Manufacturing thousands of units per month

- Quality control: Defect rates low enough for economic viability

- Performance: Write speeds acceptable for practical use cases

- Cost structure: Unit economics competitive with existing storage

- Supply chain: Ceramic materials sourced reliably and affordably

Realistic timeline from proof-of-concept to production deployment: 3-5 years. By late 2028 or 2029, we might see ceramic storage in actual use for archival applications. Consumer-grade systems or mainstream enterprise deployment would follow another 2-3 years later, by early 2030s.

This assumes no major setbacks, adequate funding, and successful engineering breakthroughs. Innovation timelines often stretch longer than projections.

This chart compares various storage methods by capacity, cost, and durability. Glass storage offers the highest durability but at a significantly higher cost, while magnetic tape provides a balance of capacity and cost for archival purposes.

Competing Technologies and the Storage Wars

Glass Storage and Project Silica's Different Approach

Microsoft's Project Silica uses an entirely different mechanism: storing data in three-dimensional patterns within glass using femtosecond laser pulses. The technology stores information spatially in the glass structure, not surface topology like ceramic.

Advantages over ceramic:

- Theoretical durability: Glass claims 10,000+ year retention, longer than ceramic's "indefinite" claims

- 3D storage: Information isn't limited to surface; you can layer information in glass depth, potentially multiplying capacity

- No wear from reading: The laser reading process is optical, potentially less invasive than electron scanning

Disadvantages:

- Read speed: Significantly slower than ceramic due to laser scanning requirements

- Write speed: Comparable to ceramic, still measured in hours or days

- Manufacturing scalability: Femtosecond lasers are exotic equipment; scaling might be harder than electron beams

- Cost: Laser-based systems might prove more expensive to manufacture at scale

Project Silica remains in research phase. Microsoft hasn't announced commercialization timelines. Glass storage and ceramic storage might both emerge, targeting different market segments: glass for ultra-permanent archival, ceramic for faster access and broader deployments.

DNA Storage: The Biological Alternative

Another competing approach: encoding data directly into DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) molecules. DNA stores information in biological bases, requires no power, and remains stable for millennia if kept dry.

Theoretical advantages:

- Extreme density: DNA stores information in four dimensions (the four different bases), giving it theoretical information density far exceeding ceramics

- Biological preservation: We understand DNA stability from archaeology; 100,000-year-old DNA has been successfully extracted

- Self-replication: DNA can theoretically copy itself, enabling redundancy without additional storage

Practical disadvantages:

- Write speed: Synthesizing DNA is currently slow and expensive

- Read speed: DNA sequencing is fast but not fast enough for large-scale random access

- Cost: DNA synthesis is measured in dollars per megabyte, far more expensive than tape

- Contamination risk: Biological material can degrade from environmental contamination, chemical attacks, or nuclease enzymes

DNA storage remains primarily research-stage. Organizations like Microsoft Research and academic institutions pursue it, but practical deployment is probably 5-10 years away at minimum.

Magnetic Tape: The Incumbent That Won't Go Away

Magnetic tape remains the data center standard for cold storage and archival. It's cheap, reasonably durable, and proven. The tape industry continues innovating: tape cartridges with higher capacity, better error correction, improved durability specifications.

Tape advantages:

- Proven economics: Cost per terabyte continues declining

- Scalable manufacturing: Production processes are mature and efficient

- Energy efficiency: Tape uses zero power when not actively reading/writing

- Established infrastructure: Entire industries built around tape libraries and management

Tape disadvantages:

- Mechanical degradation: Tape ages, magnetization degrades, mechanisms fail

- Format obsolescence: Tape drives become obsolete faster than tape media itself

- Environmental sensitivity: Temperature and humidity variations affect tape longevity

- Access latency: Reading specific data from tape cartridges requires mechanical manipulation

Ceramic storage won't immediately replace tape. The economics aren't competitive yet, and manufacturing doesn't scale. But as ceramic technology matures, it could gradually displace tape for long-term archival applications where reading speed matters less than permanence.

Economic Impact and Infrastructure Implications

Data Center Cost Restructuring

If ceramic storage achieves manufacturing scale and cost parity with existing solutions, data center economics fundamentally shift.

Current economics for 100 petabytes of archival storage (typical for a mid-size enterprise):

Magnetic Tape Approach:

- Hardware: ~$1.5M (tape cartridges + library equipment)

- Space: ~100 square feet

- Annual operating cost: $150K-250K (maintenance, environmental control, staff)

- 10-year total cost: ~$3M

Ceramic Storage Approach (projected):

- Hardware: ~$2M (ceramic media + reading equipment)

- Space: ~10 square feet

- Annual operating cost: $10K-20K (minimal maintenance)

- 10-year total cost: ~$2.2M

The calculation shows tape remaining competitive on first cost but ceramic winning on lifecycle cost. Add environmental impact (data centers consume massive electricity), and ceramic's advantage grows more significant.

As manufacturing scales and ceramics costs decline, ceramic storage becomes the default for archival. The displaced tape industry must reinvent itself for shorter-term storage roles where mechanical access remains necessary.

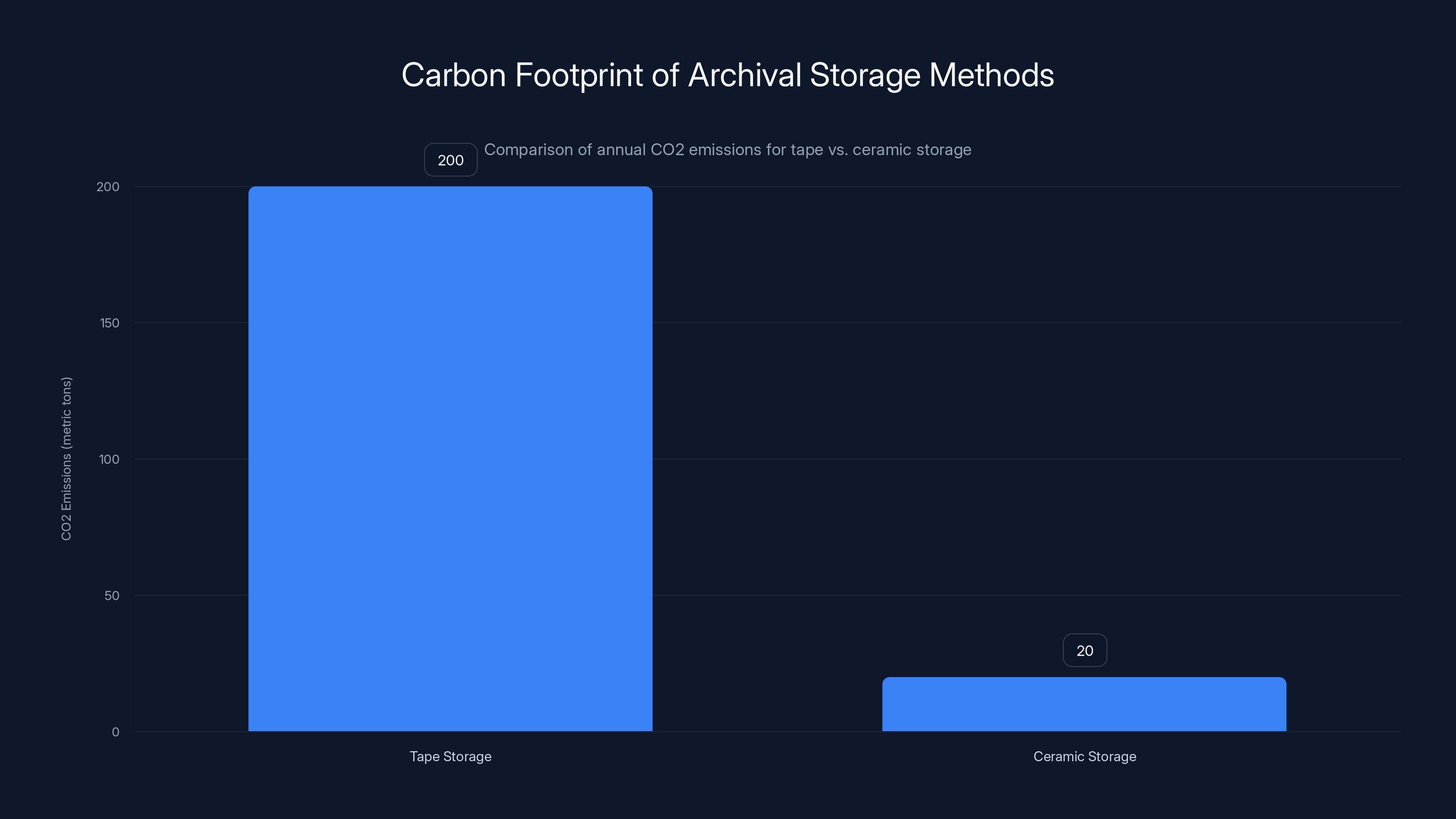

Energy Consumption Reduction

Globally, data centers consume ~1,000 terawatt-hours annually, primarily for compute and active storage. Archival storage (write once, read rarely) represents maybe 10-15% of that consumption: ~100-150 terawatt-hours per year.

If ceramic storage successfully displaces archival workloads:

(Conservative estimate: 5-10% of archival energy is required post-transition for reading and indexing equipment)

Ten terawatt-hours saved annually equals the electricity consumption of ~1 million homes. The carbon footprint reduction: roughly 5-10 million metric tons of CO2 annually, assuming typical grid electricity generation.

For context, that's equivalent to taking 1-2 million cars off the road. It's significant.

Employment and Workforce Disruption

Magnetic tape storage represents an industry employing thousands: tape manufacturer technicians, data center tape management specialists, tape library software engineers, media logistics coordinators.

Whole job categories would disappear or transform if ceramic storage dominates archival:

- Tape cartridge manufacturing would reduce or consolidate

- Tape drive maintenance positions would decline

- Tape library management software companies would pivot to other storage domains

- Tape data migration specialists would be less needed

Conversely, new employment emerges:

- Ceramic material specialists and manufacturing technicians

- Electron microscope technicians trained for reading operations

- Ceramic storage systems integration and consulting

- Failure analysis and forensics specialists (if problems develop at scale)

Net employment impact is probably neutral to slightly positive (manufacturing jobs in new technology typically outnumber displacement). But geographic disruption would be significant; existing tape manufacturing infrastructure wouldn't easily transition to ceramic production.

The adoption of ceramic storage is projected to grow steadily, achieving significant market presence by 2035. Estimated data based on industry trends.

Real-World Use Cases: Where This Technology Solves Actual Problems

Government Records and National Archives

Governments accumulate records at staggering rates. The US federal government generates roughly 300 exabytes of data annually across thousands of agencies. Most is ephemeral, but critical records (legislation, regulatory decisions, scientific data) must preserve indefinitely.

Current approach: maintain multiple copies across different systems, in different geographic locations, on different media types. Update systems every 5-10 years as technology evolves. Migrate data formats to prevent obsolescence. This costs billions annually.

Ceramic storage solution: Write critical records to ceramic once. Store in climate-controlled vault. No maintenance, no migration, no active management. The ceramic remains readable 500 years from now if historians can access an electron microscope (extremely likely given the technology simplicity).

Countries like Denmark and Germany have already expressed interest in ceramic storage for national archival. Implementation would likely begin within 5 years of commercial availability.

Scientific Data Preservation

Science generates data faster than institutions can meaningfully preserve it. Genomic sequencing produces petabytes. Climate models generate terabytes daily. Telescope observations accumulate continuously. Most disappears; selected datasets are preserved for decades or centuries of future analysis.

Scientific institutions would benefit enormously from archival storage that requires no maintenance. Write genomic sequences once, store indefinitely. Write raw telescope data, preserve for future analysis with better algorithms. The economic logic is compelling.

Institutions like CERN, major universities, and national labs would be early adopters, using ceramic storage to preserve scientific data that might yield insights decades or centuries from discovery.

Cultural Heritage and Digital Preservation

Museums, libraries, and cultural institutions struggle with digital preservation. Books digitized for preservation require migration every decade. Born-digital content (digital art, email archives, digital recordings) faces format and media obsolescence.

Ceramic storage could preserve cultural heritage indefinitely. Write digitized manuscripts, museum catalogs, cultural records to ceramic. Store in standard vault conditions. The information survives centuries while remaining accessible to future generations with minimal technological effort.

Projects like the Internet Archive and UNESCO digital preservation initiatives would shift from active maintenance focus to archival focus, reducing costs and improving longevity.

Enterprise Compliance and Legal Holds

Enterprises must maintain legally mandated records: financial data (7 years typical), healthcare data (10-30 years), employment records (7 years), intellectual property (decades to forever). Legal holds can extend retention indefinitely for litigation or regulatory purposes.

Ceramic storage solves the "write once, hold forever" use case perfectly. Compliance data written to ceramic once, stored in secure vault, requires no active management, no power, no periodic migration. The cost per byte stored essentially approaches zero after the initial write.

This particularly benefits highly regulated industries: finance, healthcare, pharmaceutical companies, utilities. Billions spent annually on compliance storage could reduce significantly with ceramic archival.

Potential Limitations and Realistic Concerns

Reading Speed Isn't Competitive for Active Workloads

Ceramic storage is exceptional for archival (write once, read rarely) but inadequate for active databases. An electron microscope scan to read data from ceramic might require hours for large datasets. This disqualifies ceramic from any application requiring rapid data access.

If you need to query data, perform analytics, or access information interactively, you'll still use traditional storage (flash, disk) fronted by ceramic archival for long-term retention.

Electron Microscope Access and Equipment Requirements

While SEMs exist worldwide, they're not ubiquitous. Accessing an SEM for reading ceramic storage requires institutional connections. This creates dependency on equipment availability and operator expertise.

In scenario where data preservation is critical (medical records, financial transactions), institutional or national requirements would probably mandate maintaining accessible SEM equipment. But this adds infrastructure cost and complexity compared to tape's simpler mechanical access.

Manufacturing Unknown Unknowns

Scaling nanometer-precision manufacturing typically encounters unexpected challenges. Thermal drift, vibration sensitivity, material variations, equipment degradation all introduce defects that don't exist in small-scale research.

Cerabyte's timeline assumes no major manufacturing surprises. If development encounters unforeseen challenges (material brittleness issues, defect rates that don't improve, yield problems at scale), commercialization could delay significantly.

Data Mutation Risk from Environmental Exposure

While ceramic is theoretically stable, real-world archival involves risk: physical damage from impacts, contamination from water infiltration, temperature shock from fire, ionizing radiation exposure in rare scenarios.

Ceramic offers robustness against time, but not immunity from catastrophic environmental events. A proper ceramic storage vault must still provide physical protection and climate control, similar to tape archival requirements.

This means ceramic storage doesn't eliminate vault infrastructure costs; it just shifts the cost ratio from operational to capital.

Format Preservation Isn't Guaranteed

QR codes are standardized, but QR standards evolve. QR codes created in 2025 might need different decoding than QR codes from 2075 if standards change.

This is less likely than with proprietary formats, but it's a real concern. Institutions relying on ceramic storage probably need to maintain metadata about QR code version, error correction level, and other specifics to ensure future readability.

Ceramic storage reduces annual carbon emissions by 90% compared to tape storage, highlighting its environmental benefits. Estimated data for potential impact.

Comparison with Traditional Storage Methods

| Characteristic | Magnetic Tape | Flash/SSD | Hard Drive | Ceramic | Glass Storage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capacity per A4 layer | 15TB (cartridge) | 100GB | 20TB | 2TB+ (projected) | 200MB (proven) |

| Power requirement | None when inactive | None when inactive | Continuous | None | None |

| Environmental control | Required | Not required | Required | Minimal | None required |

| Access speed | Hours (mechanical) | Milliseconds | Milliseconds | Hours (SEM read) | Hours (laser scan) |

| Durability estimate | 20-30 years | 10-20 years | 5-10 years | Indefinite* | 10,000 years |

| Cost per TB (estimate) | $3-8 | $50-100 | $10-20 | $5-20 (future) | $1,000+ (research) |

| Manufacturing maturity | Mature | Mature | Mature | Emerging | Research |

| Read equipment cost | $50K-200K | $200-500 | $200-500 | $250K-500K | $500K+ |

| Ideal use case | Archival/cold storage | Active databases | Consumer/active storage | Indefinite archival | Ultra-permanent records |

*Ceramic durability is projected based on material science; proven long-term data not yet available

Industry Reactions and Investor Sentiment

Western Digital's Strategic Position

Western Digital invested in Cerabyte for strategic reasons, not charity. The company is diversifying beyond flash memory and hard drives, both mature markets with limited growth.

Ceramic storage offers Western Digital several strategic advantages:

- New market opportunity: Archival market represents hundreds of billions in annual spending globally

- Differentiation from competitors: First-mover advantage in ceramic storage could establish market leadership

- Hedge against flash/HDD decline: As flash and mechanical drives mature, new storage paradigms reduce dependency on legacy technologies

- Enterprise relationships: Enterprises exploring ceramic storage become customers for related services

Western Digital's involvement signals genuine confidence but also indicates the company is hedging bets, not going all-in on ceramic. They continue investing in flash technology simultaneously, maintaining optionality.

Startup Ecosystem and Competitive Pressure

Cerabyte isn't alone in the ceramic storage space, though they're the most visible. Several startups and research groups pursue related technologies:

- Atomic storage systems exploring different material architectures

- German and European startups building on research from TU Wien

- Established storage vendors quietly researching to avoid commitment until technology matures

Competition drives innovation but also fragments the ecosystem. Standards and interoperability become critical concerns. If multiple incompatible ceramic storage formats emerge, adoption becomes fragmented and slow.

Stock Market and VC Sentiment

VC funding for archival storage startups increased substantially from 2023-2025. Investors recognize the market opportunity and the secular tailwinds: data growth, energy cost pressure, sustainability concerns all favor archival storage innovation.

However, investor enthusiasm hasn't translated to massive funding rounds for ceramic-specific companies. Most funding remains in established storage companies and promising but still-early-stage DNA storage ventures. This suggests sophisticated investors see ceramic storage as real but still 5+ years from meaningful revenue.

What Success Looks Like: Defining Commercial Viability

Milestones That Would Signal Genuine Progress

Watch for these developments indicating ceramic storage is transitioning from research to commercial reality:

2026-2027 Milestones:

- Proof-of-concept system demonstration (Cerabyte's 500GB target)

- Independent verification of data integrity after 1,000+ read cycles

- Cost analysis showing per-terabyte economics competitive with tape

- First customer pilots from major enterprises or government agencies

2027-2028 Milestones:

- Production capacity reaching 1 exabyte annually

- Standardization efforts progressing (QR code variants, error correction protocols)

- Integration with major backup/archival software vendors

- Second-source manufacturers entering market

2028-2030 Milestones:

- Commercial production at cost parity with tape archival

- Adoption in at least 10% of enterprises managing archival data

- Regulatory approval for government record preservation

- Manufacturing locations in multiple countries

If these milestones are achieved on schedule, ceramic storage becomes mainstream for archival by early 2030s. If milestones slip 12-18 months, deployment extends to mid-2030s. If fundamental manufacturing challenges emerge, viability extends to late 2030s or beyond.

What Would Cause Failure or Abandonment

Several scenarios could derail ceramic storage commercialization:

Manufacturing breakthroughs enabling better alternatives: If DNA storage or quantum storage advances faster than expected, ceramic's relative advantage diminishes.

Cost escalation due to material or equipment constraints: If ceramic production proves more expensive at scale than projected, economics fail to justify transition from tape.

Ceramic degradation discoveries: If long-term testing reveals unexpected degradation modes or failure mechanisms, durability claims collapse.

Competitive commoditization of alternatives: If tape technology improves dramatically or flash costs decline further, ceramic's economic advantage narrows.

Geopolitical disruptions: If rare materials required for ceramic manufacturing become restricted or unavailable, scaling becomes impossible.

None of these are probable, but they're possible. Innovation rarely follows perfect trajectories.

The Sustainability and Environmental Angle

Carbon Footprint Impact of Archival Storage

Data center electricity is increasingly clean (solar, wind, hydro) but still represents significant emissions. A typical kilowatt-hour from the US grid generates roughly 0.4 kg of CO2 equivalents (lower in renewable-heavy regions, higher in coal-heavy regions).

A data center archiving 100 petabytes with tape:

Ceramic storage of equivalent data:

A 90% reduction in operational carbon footprint, with additional reductions from eliminating cooling infrastructure, water usage, and facility overhead.

Globally, if ceramic storage captured 20% of archival storage market by 2035:

This is meaningful climate impact from a single technology transition.

Water Usage and Cooling Systems

Data center cooling consumes enormous amounts of water. A typical facility uses 3-5 liters of water per kilowatt-hour of electricity for cooling systems. Reducing electricity consumption directly reduces water usage.

Archival storage transition to ceramic could reduce global data center water consumption by 50-100 million gallons annually in the US alone, scaled globally to several billion gallons.

In water-constrained regions (California, Middle East, parts of Asia), this impact is more significant than carbon alone.

Longevity and E-Waste Reduction

Unlike tape cartridges that must be replaced every 20-30 years, ceramic storage persists indefinitely. This eliminates the replacement cycle that drives e-waste from storage media.

Magnetic tape manufacturing generates significant waste through rejected cartridges, environmental remediation, and end-of-life processing. Ceramic storage, being inert, eliminates this waste stream entirely.

Implementation Strategy for Early Adopters

Organizations That Should Consider Ceramic Storage Now

Even before commercial viability, certain organizations should actively monitor ceramic storage development and prepare for adoption:

Government agencies maintaining national records, historical archives, or long-term research data. Begin conversations with vendors, evaluate SEM equipment access, plan data format strategies.

Research institutions with substantial scientific data preservation requirements. Budget SEM equipment acquisition and staff training. Start pilot projects when commercial systems become available.

Large enterprises in regulated industries (healthcare, finance, pharma) maintaining compliance data indefinitely. Evaluate ceramic storage alongside traditional archival solutions for cost-benefit analysis.

Cultural institutions (libraries, museums, archives) managing digital heritage. Ceramic storage aligns perfectly with long-term preservation mandates.

Migration Strategy: From Current Systems to Ceramic

When ceramic storage becomes commercially viable, migration won't mean replacing all existing storage. A hybrid approach is more realistic:

- Identify retention-critical data: Which datasets must be preserved 100+ years? These are ceramic candidates.

- Validate data integrity: Before migrating, verify data integrity of source systems. Corruption in, corruption out.

- Convert to QR format: Transcode data from current formats to QR-encoded ceramic. This requires software development and testing.

- Establish verification process: Periodically read ceramic media to verify data integrity. Schedule re-reading every 10 years to confirm retention.

- Maintain metadata: Document QR code versions, error correction algorithms, and any format specifics. Future readers need this information.

- Decommission old storage: Once successfully migrated to ceramic, decommission tape/disk systems, recovering facility and infrastructure costs.

Migration takes time and requires careful planning. Organizations starting now will have smooth transitions by 2030-2032.

The Path Forward: Timeline and Realistic Expectations

Near-term (2025-2027): Research Validation and Proof of Concept

Expect continued research publications demonstrating ceramic storage viability. Cerabyte likely publishes detailed specifications of their 500GB proof-of-concept system. Western Digital and competitors invest in development programs.

Key question answered: Does manufacturing scale without fundamental barriers?

Mid-term (2027-2030): Early Commercial Deployment

First commercial systems reach market, priced premium to tape. Early adopters (governments, research institutions) begin pilots. Manufacturing processes improve; costs decline slowly but steadily.

Key question answered: Can ceramic compete economically with established solutions?

Long-term (2030-2035): Market Maturation

Ceramic storage becomes standard for archival workloads. Commodity markets develop around ceramic media and reading equipment. Competing formats consolidate around standards. Integration with major backup software vendors completes.

Key question answered: Does ceramic become the default archival storage medium?

Far-future (2035+): Normal Technology

Ceramic storage is background technology, neither novel nor remarkable. Like tape archival is today, organizations use it routinely without thinking about it being innovative. New storage paradigms emerge to displace ceramic for different applications.

Critical Success Factors

Ceramic storage commercialization depends on:

- Manufacturing breakthrough: Finding a scalable, economical manufacturing process

- Cost reduction: Achieving $5-10 per terabyte, competitive with tape

- Standardization: Establishing universal QR encoding standards

- Customer education: Convincing enterprises that no-power archival is superior to maintained systems

- Ecosystem development: Building software tools, integration partners, and service providers

- Investor patience: Maintaining funding through long commercialization cycle

All are achievable, but all are non-trivial. Success isn't guaranteed, but the technology foundation is sound.

The Bigger Question: Does This Change Everything?

Why This Matters Beyond Storage Efficiency

The significance of nanometer QR codes in ceramic isn't just about density or durability, though those are important. It's about decoupling information preservation from infrastructure maintenance.

For most of human history, important information was inscribed in durable materials: stone, papyrus, parchment. Preservation required no electricity, no cooling, no active management. The information sat until someone needed it.

Digital information inverted this: fast, powerful, but requiring constant active maintenance. Ceramic storage inverts it back. Information that lasts centuries with zero maintenance, readable by future humans who understand basic physics.

This has philosophical implications beyond the technical. It means cultural heritage, scientific records, and governmental decisions can be preserved with confidence they'll survive indefinitely. No more institutional dependencies on specific companies, formats, or technological paradigms.

Limitations on Changing Everything

But ceramic storage won't revolutionize all computing. It's exceptional for archival and terrible for active workloads. Most data generated daily requires fast access, frequent modification, and interactive analysis. That won't change.

The real transformation is structural: separating archival (preserve forever) from active storage (use today). Different technologies optimize for each. Ceramic dominates archival. Traditional storage remains optimal for active workloads.

This shift toward specialization is healthy. One technology trying to optimize for every scenario usually optimizes for nothing. Ceramic storage as archival specialist, flash as active specialist, allows each to be optimized for its actual requirements.

Conclusion: A Bet on Permanence

Scientists achieved something meaningful in 2025: encoding information at nanometer scale in ceramic, creating storage that could outlast human civilization without consuming power or requiring maintenance.

It's not immediately practical. It won't revolutionize computing in 2025 or 2026. Manufacturing remains unsolved. Reading requires specialized equipment. Integration with existing systems is incomplete.

But the fundamental problem is solved. We know how to create information preservation that lasts indefinitely. The engineering work ahead is execution, not discovery.

For governments deciding how to preserve national heritage. For institutions tasked with maintaining scientific records. For enterprises drowning in compliance storage costs. For humanity worrying about information loss. This research points toward a solution.

The timeline is realistic: commercial viability in the early 2030s, mainstream adoption by mid-2030s. This isn't the distant future. It's near enough to plan for, implement for, invest in.

The question isn't whether ceramic storage will work. The physics is sound, the research is validated, the concept is proven. The question is whether the people building this technology can execute the engineering required to scale it.

Given the talent involved (TU Wien is excellent), the investment (Western Digital backing), and the market opportunity (hundreds of billions annually in archival spending), the probability of success is high.

We're watching the beginning of a transition. In a decade, the way we preserve information long-term will have changed fundamentally. Ceramic storage won't be revolutionary. It'll just be obvious.

FAQ

What exactly is a nanometer QR code and how does it differ from regular QR codes?

A standard QR code uses pixels roughly 100-1000 nanometers in size, readable by smartphone cameras. The TU Wien record uses 49-nanometer pixels, roughly 20 times smaller, visible only with electron microscopes. Functionally, the encoding remains identical; only the scale changes, enabling dramatically higher information density in the same physical space.

How long can ceramic storage actually preserve data?

Demonstrated durability extends only a few years so far. However, material science predicts indefinite preservation based on ceramic's chemical stability. Unlike magnetic tape (degrading through magnetization loss) or flash memory (degrading through electron leakage), ceramic doesn't have degradation mechanisms. Projections of "indefinite" duration are reasonable but not yet empirically verified for decades-long timescales.

What does an electron microscope cost and would organizations really buy one for reading data?

Scanning electron microscopes cost

Why hasn't ceramic storage already replaced tape in data centers?

Ceramic storage remains in research phase, not commercial production. Manufacturing hasn't scaled. Read speeds are inadequate for active workloads. Cost per unit is still prohibitively high in lab conditions. These are engineering challenges, not fundamental physics problems, but solving them takes time, resources, and sometimes breakthrough discoveries.

Could ceramic storage ever become cheap enough to compete with tape on cost?

Yes, potentially. Tape costs roughly

What happens if the ceramic storage industry doesn't solve manufacturing at scale?

Ceramic storage might remain a niche solution for specialized archival (governments, major institutions) where higher costs are acceptable. Alternatively, competing technologies like DNA storage or improved glass storage might displace it. Most likely, ceramic finds a permanent home as premium archival medium for critical data while tape remains the economical standard for routine archival.

How do you ensure data isn't corrupted during the conversion to ceramic format?

Data verification before and after migration is essential. Prior to transferring to ceramic, verify source data integrity using checksums and redundancy validation. After writing to ceramic, read the data back and verify exact match with original. Periodic re-reading (every 5-10 years) maintains confidence in data preservation. Error correction in QR encoding provides additional protection against degradation.

Will this technology work internationally, or is it limited to specific countries?

Nanometer-scale storage technology isn't geographically restricted. Multiple research groups worldwide (Europe, Asia, North America) pursue similar approaches. Once commercial products emerge, manufacturing will likely happen globally with multiple suppliers. International standards development is already beginning. By 2030s, ceramic storage adoption won't be limited by geography.

Could quantum computers break ceramic storage security?

Ceramic storage doesn't rely on cryptographic security; it's purely physical encoding. Quantum computers don't affect the ability to read physically etched information. That said, if data stored on ceramic is encrypted, encryption key protection remains a separate concern. Ceramic storage and data encryption are complementary, not competitive technologies.

What's the difference between ceramic storage and Microsoft's Project Silica glass storage?

Ceramic uses QR codes etched on ceramic surface. Glass storage uses three-dimensional patterns within glass volume. Ceramic potentially offers faster read speeds and simpler manufacturing. Glass potentially offers higher density (3D storage) and longer durability (10,000+ year claims). Both are viable archival technologies targeting different optimization priorities. They'll likely coexist, not compete for dominance.

Call to Action for Runable Integration

For organizations beginning to think about long-term data preservation and documentation, planning ahead matters. If you're managing archives, documentation, or compliance records, you'll need to document your storage strategy, create preservation metadata, and establish access protocols.

Use Case: Automatically generate comprehensive data preservation documentation and archival strategy reports, reducing weeks of manual documentation to hours

Try Runable For FreeAs ceramic storage develops and commercialization approaches, creating detailed implementation roadmaps and technical specifications becomes essential. Runable helps organizations automate documentation creation for archival planning, preservation strategies, and long-term data management protocols, letting you focus on the strategic questions rather than the document assembly.

Key Takeaways

- TU Wien and Cerabyte created 49-nanometer QR codes, 37% smaller than the previous record, enabling 2TB+ storage on a single A4 ceramic layer

- Ceramic storage requires zero power and zero maintenance once written, offering true indefinite preservation unlike tape, flash, or hard drives

- Reading ceramic storage requires electron microscopes, not accessible to consumers but available at thousands of research and manufacturing facilities

- Manufacturing remains the critical challenge: scaling from laboratory demonstration to mass production within 3-5 years is ambitious but achievable

- Ceramic storage solves archival use cases (write once, preserve forever) but can't compete with flash or disk for active, frequently accessed workloads

- Commercial viability likely by 2029-2030, mainstream adoption by 2032-2035, enabling massive energy and cost savings for data preservation

- Success depends on manufacturing breakthroughs, cost reduction to $5-20 per terabyte, standardization, and ecosystem development around ceramic archival

Related Articles

- Project Silica: Glass Data Storage for 10,000 Years [2025]

- Heron Power's $140M Bet on Grid-Altering Solid-State Transformers [2025]

- DG Matrix Raises $60M: Solid-State Transformers Transform Data Center Power [2025]

- Mesh Optical Technologies $50M Series A: AI Data Center Interconnect Revolution [2025]

- Holographic Tape Storage Finally Meets Real-World Deployments in 2025 [2025]

- Laser-Tuned Magnets at Room Temperature: The Future of Storage & Chips [2025]

![Nanometer QR Codes: The Ceramic Storage Revolution That Could Last Forever [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/nanometer-qr-codes-the-ceramic-storage-revolution-that-could/image-1-1771709825700.png)