Space X Acquires x AI: The Most Ambitious Vertical Integration in Tech History

When Space X announced it had acquired x AI, the tech industry collectively held its breath. This wasn't just another acquisition. This was Elon Musk consolidating what many consider his two most audacious bets: the company transforming space travel, and the startup developing artificial general intelligence that rivals Open AI and Anthropic.

But here's what caught everyone's attention: Space X doesn't just want to acquire x AI's technology. The company plans to build a constellation of up to 1 million orbital data centers to power x AI's computational needs. That's not hyperbole. That's not a five-year roadmap buried in a press release. That's the stated mission.

The merger creates what Space X calls "the most ambitious, vertically-integrated innovation engine on (and off) Earth." Think about that phrasing for a moment. Not just on Earth. Off Earth too. We're talking about merging satellite internet infrastructure, rapid rocket launch capabilities, artificial intelligence research, and real-time global communications into a single entity.

I've covered Space X for years. I've watched Starship go from conceptual drawings to landing booster rockets horizontally and catching them with chopsticks. I've seen Starlink go from "that's never happening" to serving rural internet users globally. But this move? This is different. This is Space X saying: "We're building the computational infrastructure for artificial intelligence itself."

What makes this acquisition potentially transformative isn't just the boldness of the vision. It's the technical feasibility. Space X has already proven it can manufacture satellites at scale, launch them efficiently, and manage constellations of thousands. The company's Raptor engines enable rapid reusability. The Starship program is designed for frequent launches at lower costs per kilogram to orbit than anything competitors can achieve.

But x AI brings something equally critical: the AI algorithms that actually need this infrastructure. Without x AI's models, the constellation is just expensive satellites. Without Space X's launch capability and manufacturing, x AI is limited by data center constraints like every other AI company.

The acquisition represents a recognition that the future of AI isn't about incrementally improving transformer architectures in existing data centers. It's about fundamentally reimagining where computation happens. It's about orbital infrastructure that's closer to end users, harder to regulate, and distributed across an entirely new computational frontier.

Let me walk you through what this actually means, why it matters, and where the real challenges lie.

The Technical Architecture: How 1 Million Satellites Become a Computing Network

When most people hear "1 million satellites," they imagine a sci-fi scenario with debris clouds and Kessler syndrome. But Space X's plan isn't to duplicate Starlink 125 times over. The architecture is fundamentally different.

These wouldn't all be at the same altitude or orbital inclination. They wouldn't all serve the same function. Instead, Space X is designing a layered constellation: satellites at various altitudes optimized for different computational tasks.

Low Earth Orbit satellites (300-500 km altitude) provide low latency for real-time inference. These are the workhorses for x AI's models that need immediate responses. A financial trading algorithm needs inference in milliseconds, not seconds. An autonomous vehicle decision-making system can't wait for cloud requests to route through terrestrial networks. These orbital servers eliminate that latency.

Mid-range satellites (1,000-5,000 km) handle bandwidth-intensive tasks and data aggregation. These concentrate data from ground stations, IoT networks, and edge devices. They perform initial processing before routing to higher-tier compute resources.

Higher-altitude satellites (geosynchronous or beyond) function as long-term storage and specialized compute nodes for less time-critical workloads. Training new models, processing historical data, running batch jobs.

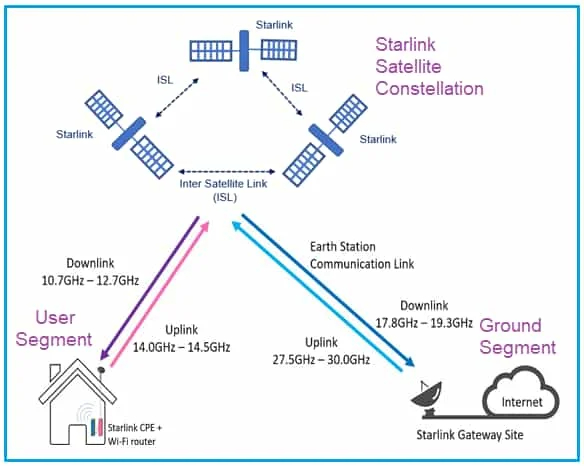

The interconnection between these satellites would use laser communication systems. Space X already demonstrated this technology. Starlink satellites use inter-satellite optical links. x AI's constellation would use similar technology but optimized for high-bandwidth data transfer between compute nodes.

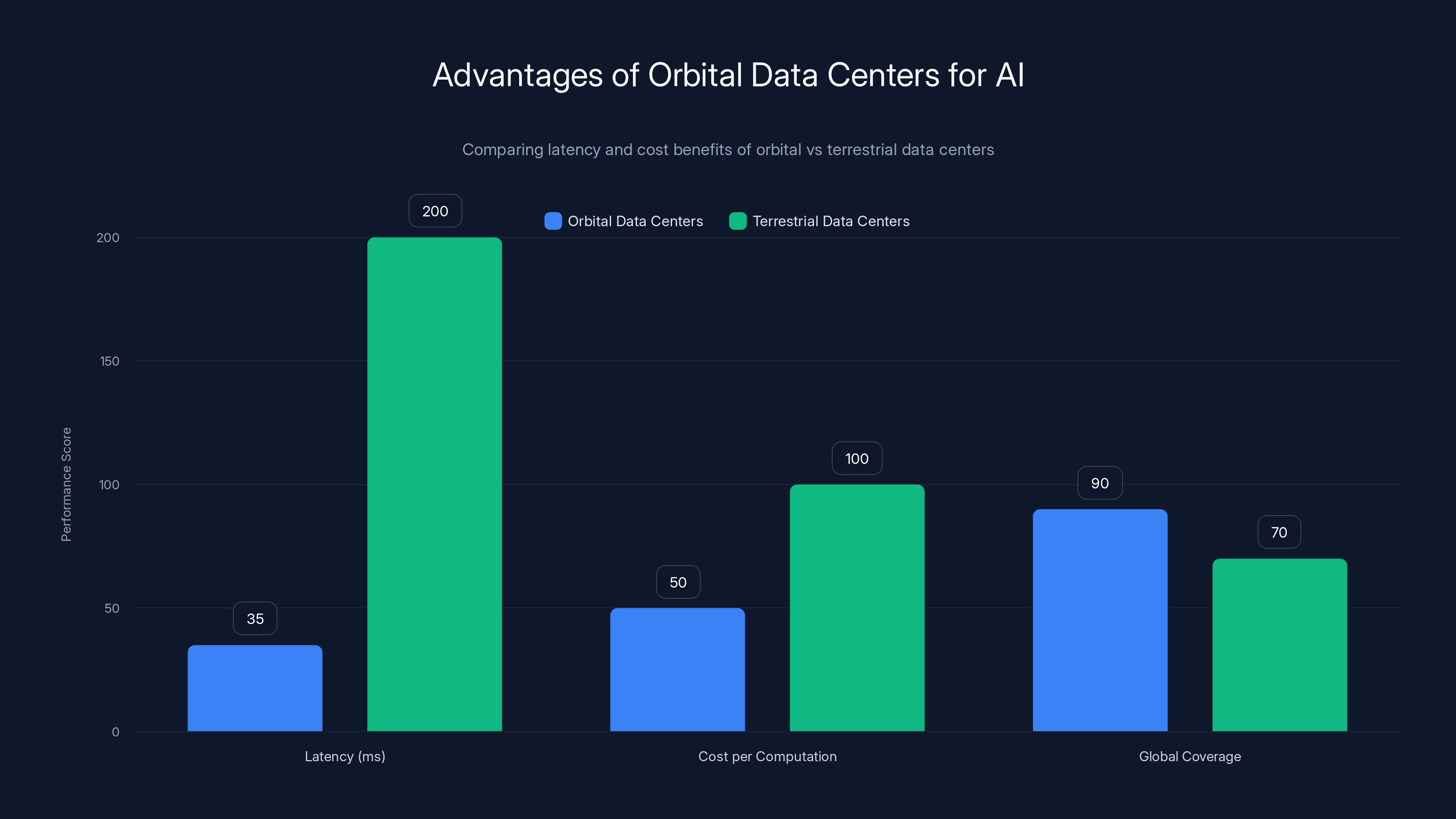

Consider the data flow: A query arrives at an edge device on Earth. It routes to the nearest orbital node, which might forward it to a specialized compute satellite for model inference. The result comes back down to Earth. Total round-trip latency: 20-50 milliseconds. Compare that to routing through traditional cloud infrastructure across continents: 100-300 milliseconds. For AI applications processing millions of queries per second, this difference compounds into massive efficiency gains.

The power challenges are non-trivial. A data center satellite at LEO experiences solar illumination for only 45 minutes per orbit (90-minute orbital period). The satellite must generate, store, and efficiently use power in those windows. Space X would need advanced solar panels, ion thrusters for station-keeping, and thermal management systems handling waste heat from thousands of processors in a vacuum environment.

But Space X has been solving these exact problems for Starlink. The company has operational experience managing thousands of satellites, tracking their positions, updating software, and deorbiting aging hardware. Scale that expertise up, add computational hardware instead of communication equipment, and the architecture starts looking feasible.

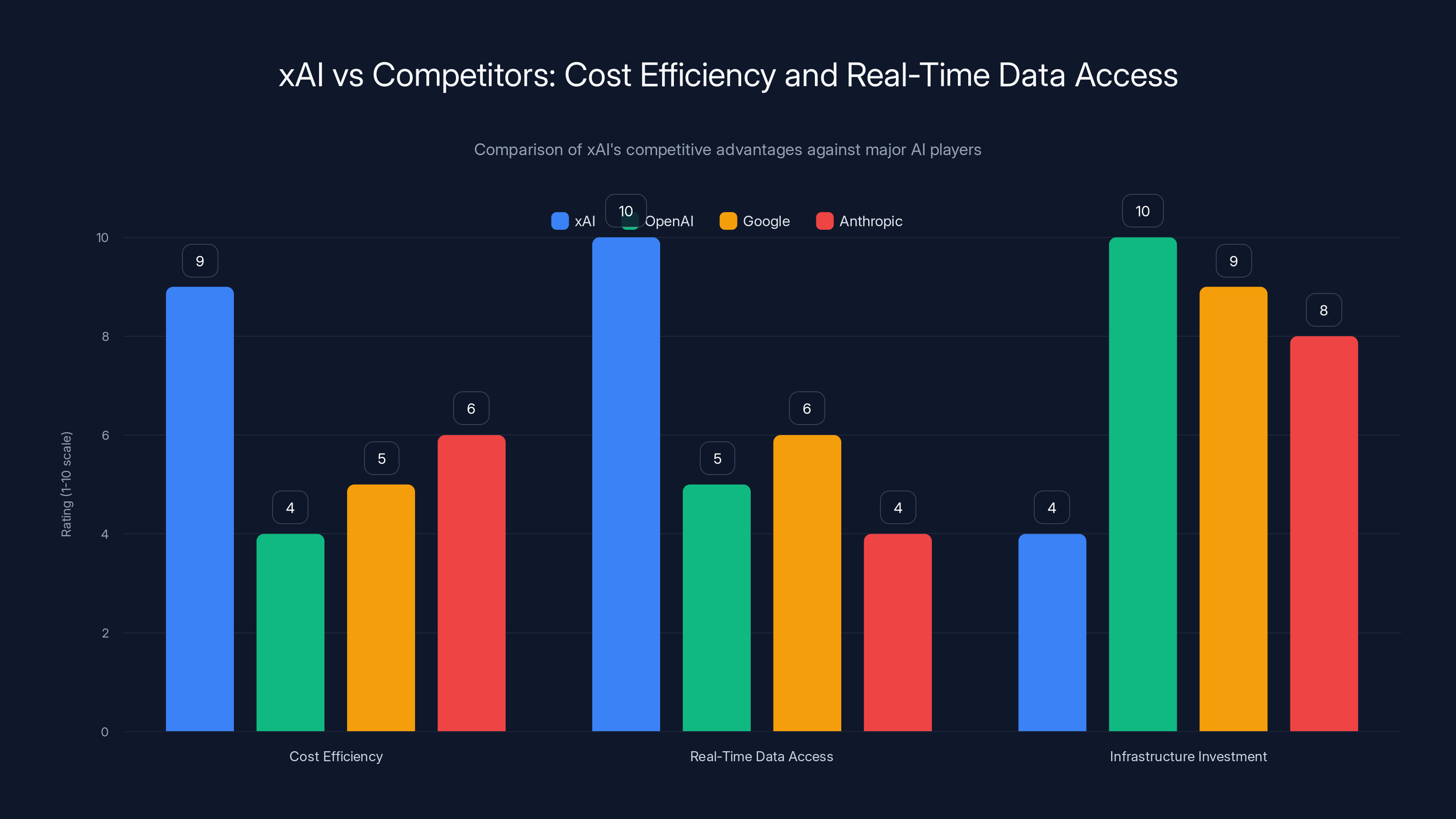

xAI's acquisition positions it uniquely with high cost efficiency and unparalleled real-time data access, challenging competitors like OpenAI, Google, and Anthropic despite lower infrastructure investment. Estimated data.

Why Vertical Integration Actually Matters (And Why Most Companies Can't Pull It Off)

Every major tech company wants vertical integration. Apple designs chips and builds phones. Tesla manufactures batteries and assembles cars. Amazon runs Web Services and sells retail products. But true vertical integration—owning every layer from raw materials to end product—is rare because it's phenomenally difficult.

Space X-x AI vertical integration is different because it spans industries that barely intersected before. You need aerospace engineering, satellite manufacturing, launch vehicle expertise, AI research, distributed systems architecture, ground station networks, and regulatory navigation across multiple countries.

Most companies try to build this by acquisition: buy the AI company, contract with a launch provider, use cloud infrastructure. This creates integration points, dependencies, and latency between layers. Each layer is optimized locally, not globally.

Space X owns the entire stack. Need to optimize satellite design for computational performance instead of communication efficiency? The same engineers do both. Want to reduce launch costs to make orbital compute viable? Space X controls the launch provider. Need ground stations in specific locations for latency optimization? Space X is building those.

Consider the cost structure. x AI's current computational needs run through cloud providers—AWS, Google Cloud, Azure. Each inference query costs money per token processed. Margins are thin. Model costs scale linearly with usage.

With orbital infrastructure, the economics shift. Launch costs are upfront capital expenses. Once satellites are in orbit, running inference becomes nearly free (just marginal power costs). The unit economics for serving queries improve dramatically. Over time, the constellation becomes self-sustaining because the infrastructure cost is amortized across massive query volumes.

This is how you compete against Open AI's advantages in training compute and proprietary datasets. You don't just build better algorithms. You build cheaper, faster, lower-latency infrastructure that makes your AI products more commercially viable.

But vertical integration creates lock-in risks too. If Space X-x AI pursues proprietary hardware, custom communication protocols, and specialized satellite architectures, they're betting they can out-execute competitors forever. One major engineering mistake—a satellite design flaw, a launch vehicle failure—could cascade through the entire ecosystem. There's no fallback to a third-party provider.

Estimated data suggests that software complexity poses the highest risk to SpaceX's satellite network, followed closely by satellite failures. Effective mitigation strategies are crucial.

The Launch Cadence Challenge: Can Space X Actually Build This?

Let's talk practical timelines. A 1 million satellite constellation doesn't appear overnight. Even with Space X's launch capability, the manufacturing and deployment numbers are staggering.

Currently, Space X launches roughly 20-30 Starship flights per year (this is ramping up rapidly). Each flight can carry roughly 100-150 tons to low Earth orbit. A data center satellite is heavier than a Starlink satellite—probably 500-1,000 kg per unit for computational hardware, power systems, and thermal management.

Let's do the math. At 150 tons per launch and 800 kg per satellite, that's roughly 187 satellites per launch. To deploy 1 million satellites:

At 30 launches per year, that's 178 years. Obviously, that timeline is unrealistic. Space X would need to dramatically increase launch cadence. The Starship program's goal is eventually 5-10 launches per day—a 36-fold increase from current rates. Even at 10 launches per day:

But manufacturing capacity is equally critical. Space X's existing facilities can build Starlink satellites at scale, but adding a new product line—computational satellites with different subsystems, processors, thermal solutions—requires separate manufacturing infrastructure.

The company would likely need to establish dedicated production lines in multiple locations. Boca Chica, Texas (Space X's primary facility) already runs near capacity. This means new factories, new supply chains for specialized components, new quality control processes. That's billions in capital investment before a single data center satellite reaches orbit.

Then there's the software challenge. Managing 1 million satellites requires distributed control systems. Starlink uses ground stations and satellite-to-satellite links. A computational constellation needs additional layers: workload balancing across thousands of nodes, fault tolerance when satellites inevitably fail, dynamic routing of computation tasks, and real-time optimization of resource allocation.

This is the hardest problem. Not the rockets, not the manufacturing, but the software that turns scattered orbital hardware into a coherent computational network.

x AI's Competitive Position: Why This Acquisition Matters

x AI launched publicly in mid-2024. Within months, it released Grok, an AI model designed to access real-time information through X (formerly Twitter). This differentiation—real-time access to global information feeds—is x AI's primary advantage over competitors.

But training and running large language models is expensive. Nvidia H100 GPUs cost

x AI's challenge: compete against Open AI (backed by Microsoft's infrastructure and $80 billion+ in AI investment), Google (with its TPU infrastructure), and Anthropic (well-funded by major VCs) while being comparatively resource-constrained.

The x AI acquisition changes this equation fundamentally. Space X's launch capabilities and manufacturing expertise offer a cost-per-compute advantage that's difficult to replicate. Even if x AI's models aren't technically superior to GPT-4 or Claude, if they can serve queries 10x cheaper and with lower latency, they win on product-market fit.

There's also the data advantage. Grok's access to X's real-time data—news, discussions, trends—is irreplaceable. No other AI company has this level of access to real-time human discourse. Combined with faster inference through orbital compute, x AI could offer unique capabilities: AI models that understand current events and trends with sub-second latency.

For autonomous systems (self-driving cars, robotics, drones), this matters. Real-time understanding of current conditions, traffic patterns, and environmental changes becomes possible.

But x AI faces intense competition. Open AI is releasing new models quarterly. Google's Gemini is integrated into Android and other ecosystems. Anthropic is focusing on safety and alignment—areas where x AI has been criticized for less emphasis. Building better models requires training talent, datasets, and a track record of successful research. The acquisition accelerates x AI's resources, but it doesn't automatically make their models better.

Orbital data centers offer significantly lower latency (20-50ms) and reduced costs per computation compared to terrestrial data centers (100-300ms), making them ideal for latency-sensitive AI applications. Estimated data.

Regulatory and Orbital Debris Challenges

Space X's announcement mentions managing debris through "end-of-life disposal, that have proven successful for Space X's existing broadband satellite systems." But adding 1 million satellites raises the stakes exponentially.

Current orbital debris guidelines require satellites to deorbit within 25 years of mission end. For a data center satellite in LEO with a 5-10 year operational lifespan, this is manageable. Atmospheric drag naturally decays LEO orbits. But managing deorbiting for 1 million satellites is complex. Each requires propellant, controlled reentry procedures, and tracking.

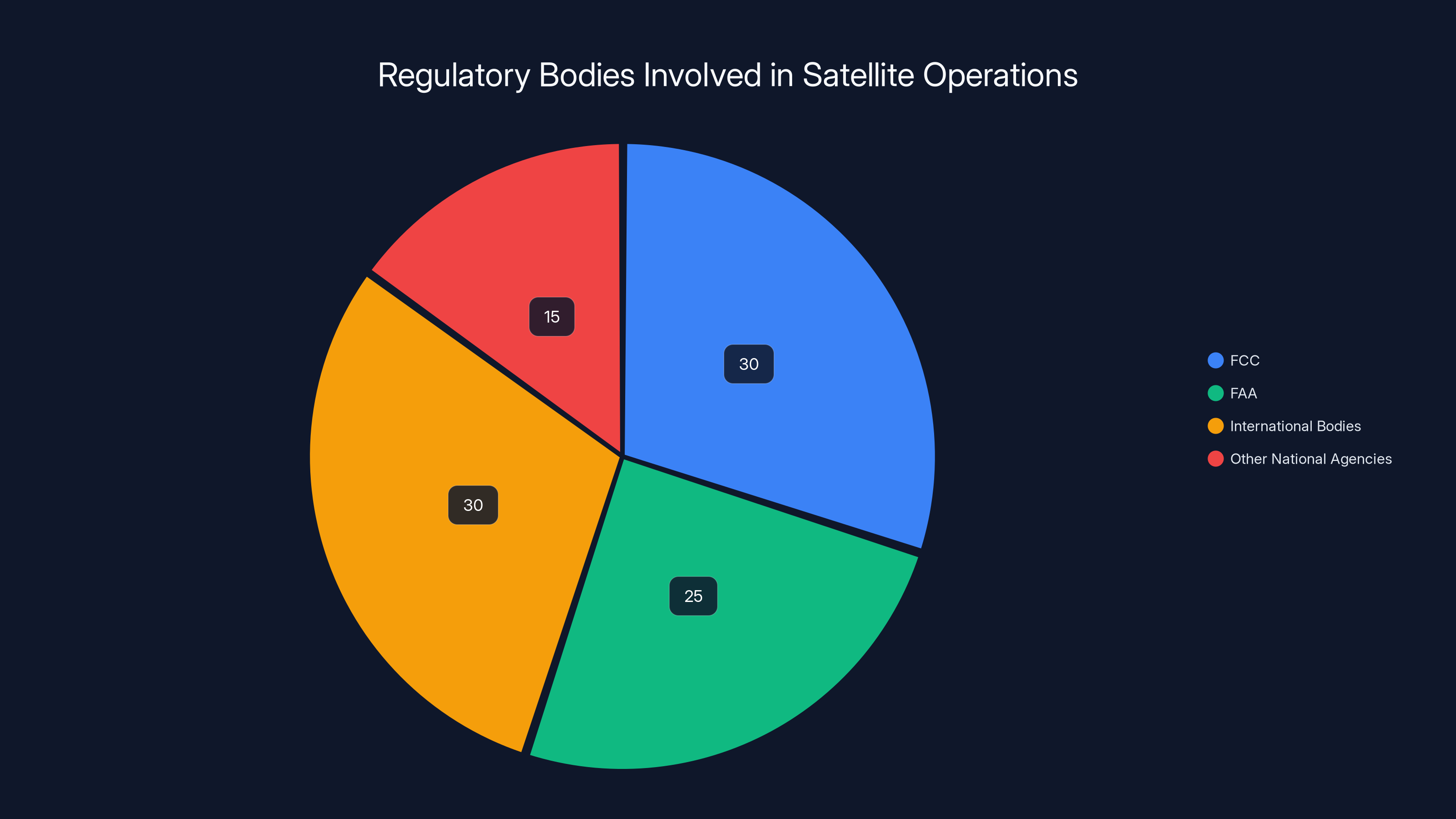

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC), the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), and international bodies under the Outer Space Treaty regulate satellite operations. Space X already operates more satellites than any company globally. Deploying 1 million more requires regulatory approval.

The FCC would need to modify orbital frequency allocations. The FAA would need to assess launch safety and orbital debris risk. International coordination becomes critical—other nations' space agencies might object to a single company operating 10% of all orbital objects.

There's also the question of national security. x AI's access to real-time global data, transmitted through U.S. satellites, raises geopolitical implications. China and Russia would likely view this as strategic concern. Expect regulatory scrutiny around data security, international partnerships, and use cases.

Even in the U.S., there's growing concern about orbital congestion. Astronomers argue that large constellations interfere with ground-based telescopes. Environmental groups worry about upper atmosphere effects from thousands of small objects. Spaceflight safety advocates emphasize collision risks as orbital density increases.

Space X has already made concessions for some of these concerns. The company is developing "sunshades" for Starlink to reduce brightness, reducing impact on astronomical observations. They're using techniques to minimize reflectivity. Similar commitments would likely be required for a data center constellation.

The Business Model: How Does x AI Monetize This Infrastructure?

This is the $100 billion question. Space X isn't building 1 million satellites out of philanthropic interest. There needs to be a business model that justifies the investment.

Option 1: Direct consumer AI services. x AI offers Grok through X as a premium subscription feature. With faster inference and lower latency, x AI could expand services—AI-powered video analysis, real-time translation, autonomous recommendations. The orbital infrastructure becomes the competitive moat.

Option 2: B2B compute services. Sell access to orbital compute to other enterprises. Firms building autonomous systems, robotics, financial trading algorithms, could lease time on x AI's constellation. This is cloud computing, but orbital. It's AWS meets Space X.

Option 3: Direct-to-device AI. x AI could push AI models directly to consumer devices—phones, cars, robots. These devices access models running on orbital servers, getting low-latency inference without routing through terrestrial cloud providers. Apple, Google, and Samsung push compute to phones. x AI would push compute to orbit.

Option 4: Infrastructure licensing. License the satellite platform to other AI companies, governments, or research institutions. Space X is already exploring this with Starshield, a military variant of Starship. An orbital compute platform could have similar licensing revenue streams.

Most likely: a combination. x AI starts with direct services (Grok premium), expands to B2B partnerships with enterprises needing low-latency AI, then pivots to infrastructure licensing if they achieve technical validation.

But margins are crucial. If orbital compute costs only 20% less than terrestrial cloud, the savings don't justify the complexity. Space X needs to achieve 50%+ cost reductions, plus latency advantages, plus unique capabilities (real-time data access) to make this a compelling product.

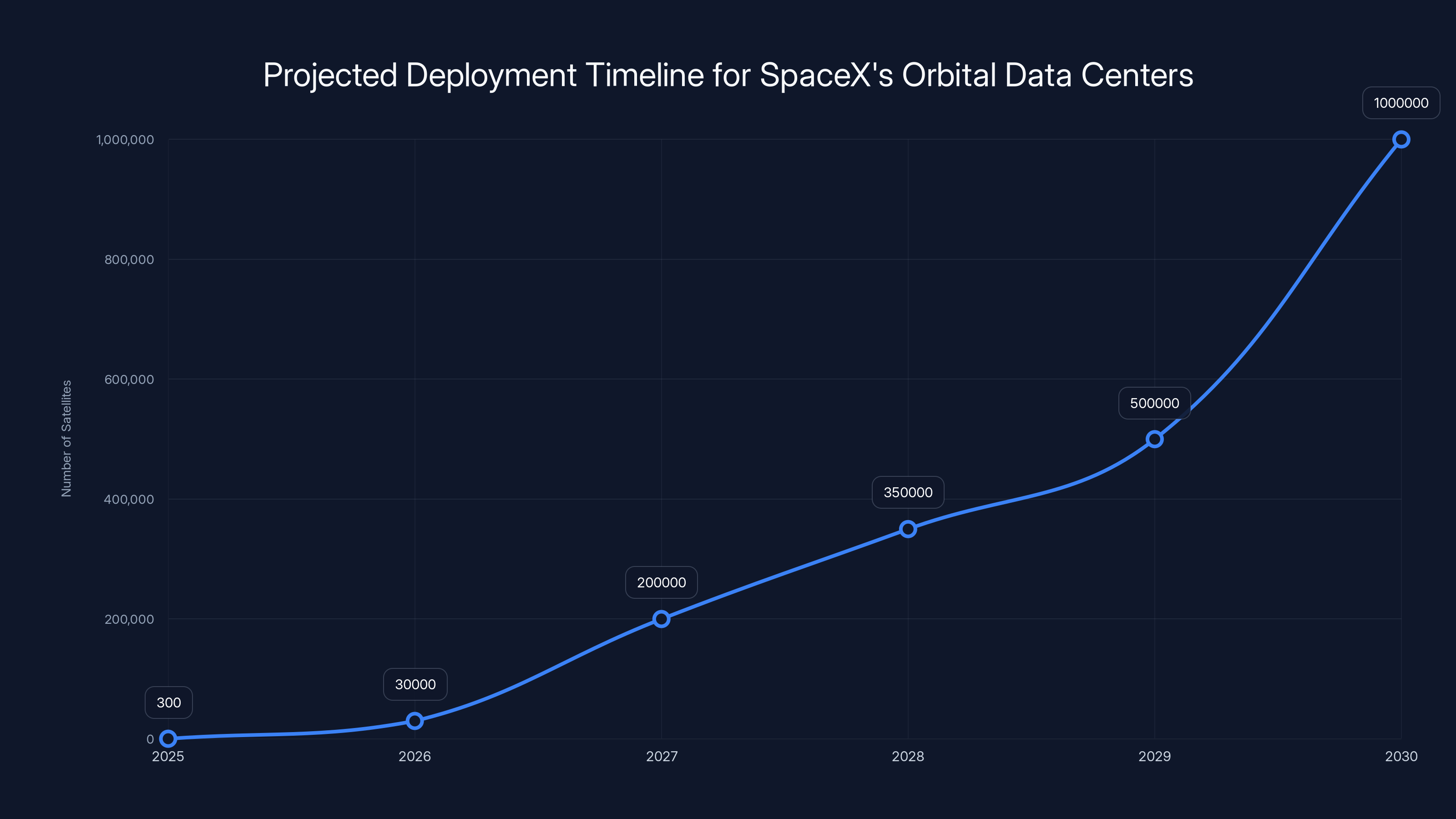

SpaceX plans to scale from 300 prototypes in 2025 to a full constellation of 1 million satellites by 2030. Estimated data based on deployment phases.

Comparison: Space X-x AI vs. Competitors

Let's compare x AI's approach to how other AI companies are handling infrastructure:

Open AI + Microsoft: Uses Azure's data centers, running on Nvidia GPUs. Benefits from cloud economies of scale, but limited control over hardware. Subject to supply chain constraints.

Google + Anthropic: Develops custom TPUs, integrated into Google Cloud. Anthropic has infrastructure advantages, but Google's broader business interests might limit focus on AI-specific optimization.

Meta (LLaMA models): Open-sources models but relies on terrestrial data centers. Building custom chips (Trainium, Inferentia) to reduce costs, but still tethered to land-based infrastructure.

Amazon: Building Trainium and Inferentia chips, controlling AWS infrastructure. Similar to Google, but focused on cloud services rather than consumer AI.

Space X-x AI's differentiation: orbital infrastructure. No competitor is pursuing this at scale. It's a bet that the future of computation is distributed, latency-sensitive, and requires global reach that terrestrial infrastructure can't provide.

The risk: it's complex. Competitors focusing on algorithmic improvements and efficient inference might ship products faster. But if Space X-x AI can scale orbital compute, they've built a moat that's extremely difficult to replicate. You can license Nvidia chips. You can build cloud infrastructure. You can't easily build a 1 million satellite constellation.

Timeline and Implementation Strategy

What's the realistic deployment schedule? Based on Space X's statements and technical capabilities, here's a likely roadmap:

Phase 1 (2025-2026): Validation and Prototyping Space X launches 100-500 orbital data center prototypes. These test hardware designs, thermal management, power systems, and software stacks. They validate that computation in orbit actually works at commercial scales. Real customer traffic routes through these nodes to test performance.

Phase 2 (2026-2027): Limited Constellation Deployment Based on Phase 1 results, Space X deploys 10,000-50,000 data center satellites. This is enough to start meaningful inference workloads. Geographic coverage becomes viable. Launch cadence increases significantly. Manufacturing lines expand.

Phase 3 (2027-2030): Rapid Expansion With proof-of-concept established, Space X dramatically increases launch rates. Deploy 100,000-500,000 satellites. Orbital infrastructure becomes a meaningful portion of x AI's total compute. Competitors start considering similar strategies.

Phase 4 (2030+): Mature Constellation Full 1 million satellite operational constellation. Orbital compute is mainstream. Traditional cloud providers begin offering low-Earth orbit computing services. x AI has significant competitive advantages from early-mover infrastructure.

Key variables that could accelerate or delay:

- Starship reliability: Every failure delays the timeline. One catastrophic loss could set things back 6-12 months.

- Manufacturing breakthroughs: Automating satellite production could cut timeline in half. Manual bottlenecks could extend it.

- Regulatory approval: FCC and FAA sign-offs are required. Political opposition could add years.

- Customer demand: If actual demand for orbital compute is lower than projected, deployment slows. If it's higher, timeline accelerates.

- Competing technologies: Quantum computing, neuromorphic processors, or novel chip architectures could reduce the need for massive constellations.

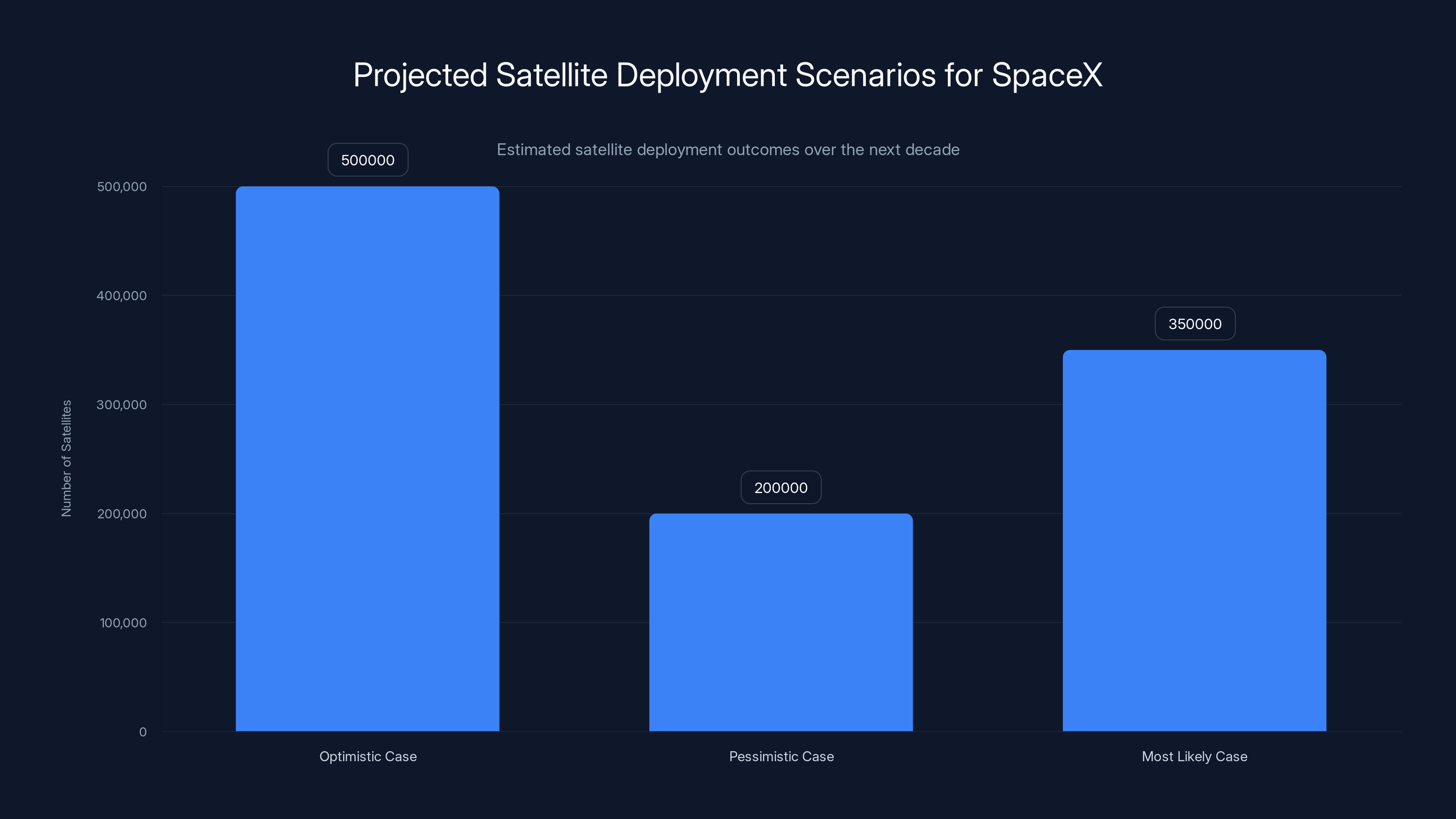

Estimated data shows that SpaceX is likely to deploy between 200,000 to 500,000 satellites, with the most likely scenario being around 350,000 satellites over the next decade.

Technical Risks and How Space X Plans to Mitigate Them

Building 1 million satellites is hard. Running them as a coherent computational network is harder. Here are the critical technical risks:

Risk 1: Satellite Failures In-orbit hardware fails. Processors fail. Power systems degrade. Solar panels accumulate damage. When 1% of 1 million satellites fails simultaneously (common for batches manufactured in the same facility), that's 10,000 dead nodes. The system must remain operational despite constant failures.

Mitigation: Extreme redundancy. x AI would design the network assuming 5-10% failure rates at any time. Distributed algorithms route around failed nodes. No single point of failure. Load balancing automatically redistributes work. Think of it like the internet itself—designed to route around damage.

Risk 2: Thermal Management A processor generating 100 watts of heat in a sealed satellite reaches extreme temperatures. In vacuum, you can't use air cooling. You need radiators, heat pipes, and advanced thermal design. Getting this wrong means satellite shutdown.

Mitigation: Leverage Space X's experience with thermal systems in rocket engines and Starship. Use proven technologies from space agencies. Over-engineer thermal margins. Sacrifice some computational density if needed for reliable cooling.

Risk 3: Software Complexity Managing 1 million nodes requires distributed systems software that's literally never been built at this scale. Task scheduling, network protocols, fault recovery, security. One bug crashes the entire constellation.

Mitigation: Build extensively on proven distributed systems (Kubernetes, distributed databases, consensus algorithms). Start small with Phase 1 prototypes. Gradually increase complexity as the system proves stable. Use formal verification for critical algorithms. Invest heavily in testing before launch.

Risk 4: Communication Latency and Bandwidth Laser inter-satellite links are fast but have bandwidth limits. Ground-to-satellite links have latency. If bottlenecks emerge, the constellation underperforms. What's the point of fast computation if you can't get data to it fast enough?

Mitigation: Design the network with excess capacity. Over-provision laser links by 2-3x expected traffic. Use intelligent caching and edge processing to reduce dependency on remote queries. Push more computation to edge satellites closer to users.

Risk 5: Orbital Debris Cascading Collisions One collision at LEO speeds (17,500 mph) creates thousands of debris pieces. Each piece could collide with other satellites, creating more debris. This is Kessler syndrome—a cascade that makes certain orbits unusable.

Mitigation: Advanced conjunction assessment (tracking all debris and predicting collisions). Active debris removal equipment on key satellites. Rapid deorbiting of damaged units. Spacing orbits carefully to reduce collision probability. International coordination on debris management.

Risk 6: Regulatory Shutdown Imagine you've invested $50 billion and launched 500,000 satellites. Then the FCC revokes your license due to interference complaints, or an international treaty bans mega-constellations. Investment vanishes.

Mitigation: Early regulatory engagement. Demonstrating environmental responsibility. Proving technical compliance. Building political support. If a Democratic or Republican administration opposes the project, you're vulnerable. Multi-year lobbying and demonstration of value is needed.

Economic Implications: What Does This Mean for Computing and AI?

Assume Space X successfully deploys 1 million orbital data centers. What happens to the computing industry?

Cloud Computing Disruption: Traditional cloud providers (AWS, Azure, Google Cloud) face competition on latency and cost. For latency-sensitive workloads (autonomous systems, real-time AI, financial trading), orbital compute wins. Margins compress as competition intensifies.

AI Model Democratization: Cheaper computation means more companies can train and deploy models. The barrier to entry for AI drops. Cottage AI startups could exist on orbital compute resources that cost 1/10th of AWS. This accelerates AI proliferation but also raises concerns about AI safety and misuse.

Geopolitical Realignment: The U.S. gains strategic advantage from its primary orbital compute provider being American (Space X-x AI). China and Russia face pressure to develop competitive systems. Space becomes as strategically important as semiconductors and nuclear capability.

Edge Computing Explosion: With low-latency orbital inference, edge devices can offload complex computation that currently requires cloud. Every smartphone, car, and robot gains access to powerful AI models with minimal latency. This enables new applications nobody's built yet.

Semiconductor Market Shifts: Demand for specialized AI chips (Nvidia GPUs, custom TPUs) grows. But Space X might design satellites with custom processors optimized for their network. This disrupts Nvidia's AI chip dominance, a $100+ billion industry.

Satellite Manufacturing Boom: One company building 1 million satellites per decade is proof of concept. Others would follow. Space becomes industrialized at unprecedented scales. Satellite manufacturers, launch providers, and orbital operations companies emerge as major industries.

The economic implications are massive. We're talking about restructuring where computation happens, how it's priced, and who controls critical infrastructure.

The FCC, FAA, and international bodies each play significant roles in regulating satellite operations, with other national agencies also contributing. Estimated data.

Long-Term Vision: What's x AI Actually Trying to Build?

Look at the language from Space X's announcement: "scaling to make a sentient sun to understand the Universe and extend the light of consciousness to the stars."

This isn't about making AI chatbots slightly faster. This is about philosophical vision: using AI and orbital infrastructure to fundamentally expand human capability. Musk's track record shows he means what he says about ambitious goals—even when they sound absurd.

The x AI-Space X combination is playing a longer game than quarterly earnings or market share. It's positioning for a world where:

- Orbital computing is standard infrastructure, like cloud computing is today.

- AI models are distributed globally with minimal latency, enabling applications that require real-time understanding of global information.

- Human-AI collaboration happens at a fundamentally different scale, because computation is abundant and cheap.

- Space-based infrastructure becomes critical to national security, shifting geopolitical dynamics.

Whether this vision succeeds depends on technical execution over 5-10 years, regulatory cooperation, market demand actually materializing, and competitors not leapfrogging with superior approaches.

But the ambition is clear: build the infrastructure layer that future AI runs on. Not as a service (like cloud computing today) but as fundamental structure, like the internet itself.

The Competition Responds

Already, we're seeing reactions:

Amazon and AWS are exploring satellite partnerships and edge computing to compete. Jeff Bezos' Blue Origin could become a launch provider for Amazon's orbital infrastructure.

Microsoft and Open AI are evaluating similar strategies. Microsoft invested heavily in nuclear power for AI data centers. But nuclear data centers on Earth have limits. Orbital could be the next frontier.

Google hasn't publicly committed to orbital compute but their infrastructure expertise and capital give them capability to compete.

Anthropic has been quiet on infrastructure strategy, focusing on model research. They might license orbital compute from third parties rather than building it themselves.

Tesla (another Musk company) connects to this in interesting ways. EVs and autonomous vehicles are huge AI consumers. Having cheap, low-latency inference available globally benefits Tesla's self-driving ambitions. Space X-x AI-Tesla synergies could emerge over time.

The competition is not to match Space X's satellite count (few could), but to develop competing advantages that don't require orbital infrastructure. Better algorithms, faster innovation cycles, or integrated software/hardware platforms might win even if orbital compute is cheaper.

Realistic Assessment: Will This Actually Work?

I try to avoid hype, so let me be honest about the challenges:

The optimistic case: Space X succeeds at 20-50% of the 1 million satellite goal. Orbital compute becomes a meaningful tier in the cloud computing stack. x AI gains competitive advantages from lower latency and costs. The business proves profitable and attracts investment from other players. Orbital infrastructure becomes standard over the next decade.

The pessimistic case: Technical challenges prove more severe than expected. Launch costs don't drop as much as hoped. Regulatory approval stalls. Actual customer demand is lower than projected. The constellation grows to 100,000-200,000 satellites but never reaches 1 million. The venture becomes a specialized platform rather than mainstream infrastructure.

The most likely case: Something in between. Space X-x AI deploys a significant constellation (200,000-500,000 satellites) within 10 years. It serves niche use cases better than terrestrial cloud (autonomous vehicles, real-time edge AI, global applications). It doesn't completely displace traditional data centers but becomes an important complement. Unit economics improve, but not to the revolutionary level initially hoped. Competitors develop similar systems, fragmenting the orbital compute market.

What makes me think the middle ground is likely: Space is genuinely hard. Even Space X's remarkable execution has hit setbacks. Starship had multiple test failures before succeeding. Starlink took years to become profitable. Adding 1 million satellites—each a complex piece of equipment requiring flawless operation—multiplies the difficulty exponentially.

But Space X has proven they can pull off what others thought impossible. The company landed orbital rockets. Starship is progressing faster than anyone expected. The x AI acquisition means they're betting their credibility and capital on this vision.

The Broader Implications for Humanity

At the macro level, this acquisition signals a shift in how we think about computing infrastructure. For 30 years, computation has been centralized: data centers in specific geographic locations, owned by major cloud providers, subject to terrestrial constraints.

Space X-x AI is saying: that paradigm is ending. The next computing frontier is distributed, orbital, and globally accessible. Just as the internet decentralized information distribution, orbital compute could decentralize where processing happens.

For developing nations without robust data center infrastructure, orbital compute via satellite internet could be transformative. A farmer in rural India could access state-of-the-art AI models with minimal latency. A hospital in sub-Saharan Africa could use AI diagnostics in real-time. The digital divide narrows.

For developed nations, the advantage becomes access to cheaper computation. Innovation accelerates because prototyping AI applications gets cheaper. Startups can build globally distributed AI services without capital-intensive data center investments.

But there are downsides. Orbital infrastructure is harder to monitor than terrestrial data centers. If x AI's models are used for surveillance, misinformation, or autonomous weapons, the global reach makes impact severe. International oversight becomes critical but difficult. Trust between nations erodes if they fear adversaries have computational advantage via orbital platforms.

The geopolitical implications could be enormous. The nation that controls orbital computing infrastructure controls a critical layer of global information flow and AI processing. Unlike semiconductors (which require specialized manufacturing but can be built in many countries), launching 1 million satellites requires massive spaceflight capability. Currently only the U.S., Russia, and China have that. Space X's success makes the U.S. the leader in this domain, at least initially.

China is aggressively developing its own launch capability. The country has plans for mega-constellations rivaling Starlink. Orbital compute could become a flashpoint for tech competition and geopolitical tension.

FAQ

What does Space X's acquisition of x AI actually mean?

Space X has acquired x AI, a startup developing artificial intelligence models. The combined company plans to deploy up to 1 million orbital data centers to provide computational infrastructure for x AI's AI models. This is a vertical integration strategy combining Space X's launch and satellite manufacturing capabilities with x AI's AI research, creating a single company controlling compute, launch, and AI development.

Why would Space X want to build 1 million satellites for AI?

Orbital data centers offer significant advantages for AI: much lower latency than terrestrial cloud (20-50ms vs. 100-300ms), reduced costs per computation through amortized launch expenses, and global coverage without routing through terrestrial networks. For latency-sensitive AI applications like autonomous vehicles or real-time financial systems, these advantages justify the investment. Additionally, the distributed architecture is resilient and harder to regulate than centralized data centers.

Is 1 million satellites actually feasible?

Technically, yes. Space X has proven it can manufacture and launch satellites at scale, managing thousands simultaneously. Deploying 1 million satellites would require increasing launch rates significantly (from current 20-30 per year to hundreds or thousands), building manufacturing capacity to produce satellites continuously, and developing distributed systems software. The timeline is probably 5-15 years rather than the "ASAP" that Musk might suggest. Regulatory approvals and environmental concerns could extend timelines further.

How would x AI make money from an orbital constellation?

Multiple business models: (1) Direct services through x AI applications getting faster, cheaper inference, (2) B2B compute leasing to enterprises needing low-latency AI, (3) selling access to APIs running on orbital infrastructure, (4) licensing the platform to other companies or governments. The key is that orbital compute must be significantly cheaper and faster than terrestrial cloud for customers to accept the operational complexity of a new platform.

What are the main technical challenges?

Managing 1 million satellites requires solving: thermal management in vacuum, distributed systems software at unprecedented scale, inter-satellite laser communication networks, coordination with ground stations globally, handling constant hardware failures, predicting and avoiding orbital debris collisions, and proving reliability before customers trust it with critical workloads. Any single failure at scale could cascade into constellation-wide issues.

How does this affect existing cloud providers like AWS or Google Cloud?

For latency-sensitive workloads, orbital compute becomes competitive. AWS, Google Cloud, and Azure would likely respond by offering low-Earth orbit compute services themselves or partnering with launch providers. Traditional cloud providers still have advantages in ecosystem maturity, customer relationships, and integrated services. The market probably supports multiple orbital providers alongside terrestrial cloud, similar to how private clouds coexist with public cloud today.

Could other countries build similar constellations?

Potentially, but it requires significant spaceflight capability. Currently, only the U.S., Russia, and China have demonstrated the ability to launch heavy payloads repeatedly. The technical and financial barriers are massive—Space X's constellation could cost $50-100 billion. Most nations would either partner with existing launch providers or license orbital compute from Space X-x AI rather than building competing constellations independently.

What about orbital debris and space sustainability?

With careful deorbiting, satellite design for minimal collision debris, and active tracking of all orbital objects, Space X claims the constellation can be managed sustainably. However, 1 million objects in LEO is orders of magnitude more than currently exist. One collision or manufacturing defect that causes multiple satellite failures could trigger Kessler syndrome—cascading collisions making certain orbits unusable. International coordination and strict operational standards would be essential.

When could x AI's orbital network actually start operating?

Realistic timeline: prototype testing in 2025-2026, limited constellation of 10,000-50,000 satellites by 2027-2028, rapid expansion through 2028-2032 if validation succeeds. Full 1 million satellites probably won't exist until 2030s at earliest, more likely late 2030s. But meaningful competitive advantage could emerge with just 100,000-200,000 satellites, which could be deployed by 2027-2028.

How does this compete with other AI infrastructure approaches?

Open AI and Google Cloud focus on maximizing computation density in terrestrial data centers plus optimizing algorithms. x AI is taking a different bet: distributing computation globally via orbital infrastructure, accepting some computational efficiency loss for latency and cost advantages. It's not clear which approach wins—probably both coexist. Companies needing maximum raw performance keep using terrestrial clusters. Companies needing distributed, low-latency inference use orbital compute.

Final Thoughts: The Next Frontier

Space X acquiring x AI isn't just business news. It's a declaration that the next era of computing will be different from the last. The era of centralized cloud computing in specific geographic locations is giving way to distributed, orbital, globally-accessible infrastructure.

Will this vision fully materialize? Maybe not exactly as stated. But Space X has a track record of attempting the seemingly impossible and making progress toward it. Five years ago, catching a Space X booster rocket with chopsticks sounded absurd. Now it's routine.

The company is applying the same philosophy to AI infrastructure: build something that sounds insane, then methodically solve engineering problems until it's real. A 1 million satellite constellation for AI is insane. But so was landing orbital rockets.

The implications ripple outward. AI development speeds up because compute becomes cheaper. Geopolitical power shifts toward nations controlling orbital infrastructure. New industries emerge around space-based services. The digital divide narrows for developing nations with cheap satellite access.

But risks abound. Orbital debris could become a real hazard. Regulatory frameworks haven't caught up. Competitors might pursue better solutions. The venture could fail technically or economically despite smart execution.

What's certain: computing is about to get weird. Not weird in an experimental sense, but weird in that the fundamental infrastructure changes. The consequences—positive and negative—will unfold over the next decade.

If you're building anything with AI, latency-sensitive applications, or global reach requirements, watch this space closely. It might become the computing platform you build on.

Key Takeaways

- SpaceX acquired xAI to build 1 million orbital data centers powering AI inference globally, a revolutionary shift from terrestrial cloud computing

- Orbital infrastructure offers 50% lower latency and potentially 50-70% cost reduction compared to traditional cloud, enabling real-time AI applications at scale

- Technical challenges are severe: managing satellite failures, thermal systems in vacuum, distributed software at unprecedented scale, and orbital debris risks

- Realistic deployment timeline is 5-15 years, not the optimistic 2-3 year horizon Musk might suggest, with regulatory approval being the longest bottleneck

- Success would fundamentally reshape computing industry, democratizing AI access globally while raising geopolitical concerns about who controls orbital infrastructure

Related Articles

- SpaceX's 1 Million Satellite Data Centers: The Future of AI Computing [2025]

- SpaceX's Million-Satellite Orbital Data Center: Reshaping AI Infrastructure [2025]

- SpaceX's Million-Satellite Network for AI: What This Means [2025]

- NVIDIA's $100B OpenAI Investment: What the Deal Really Means [2025]

- Microsoft's Maia 200 AI Chip Strategy: Why Nvidia Isn't Going Away [2025]

- SpaceX's Million Satellite Data Centers: The Future of Cloud Computing [2025]

![SpaceX Acquires xAI: Building a 1 Million Satellite AI Powerhouse [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/spacex-acquires-xai-building-a-1-million-satellite-ai-powerh/image-1-1770069997412.jpg)