Space X's Audacious Plan to Build the Ultimate Orbital Data Center

When Space X filed its application with the Federal Communications Commission on Friday, the aerospace industry collectively held its breath. One million satellites. Not 7,500. Not 30,000. A million.

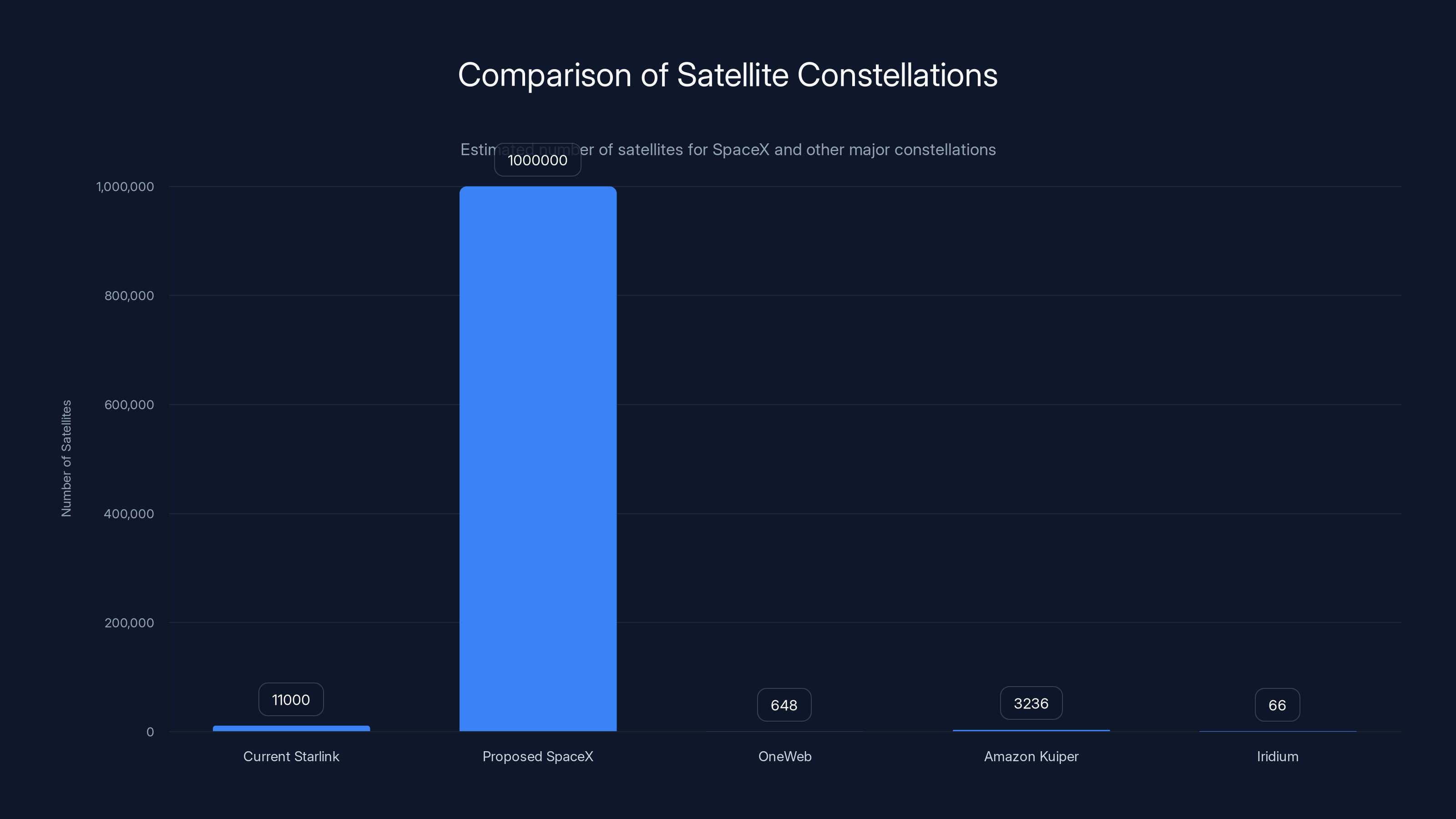

To understand what that actually means, let me give you some context. Right now, humans have launched roughly 11,000 Starlink satellites into orbit, with around 9,600 actively operating as of January 2026. Space X built the largest satellite constellation humanity has ever seen. And now they're saying, "Yeah, we're going to do that roughly 100 times over."

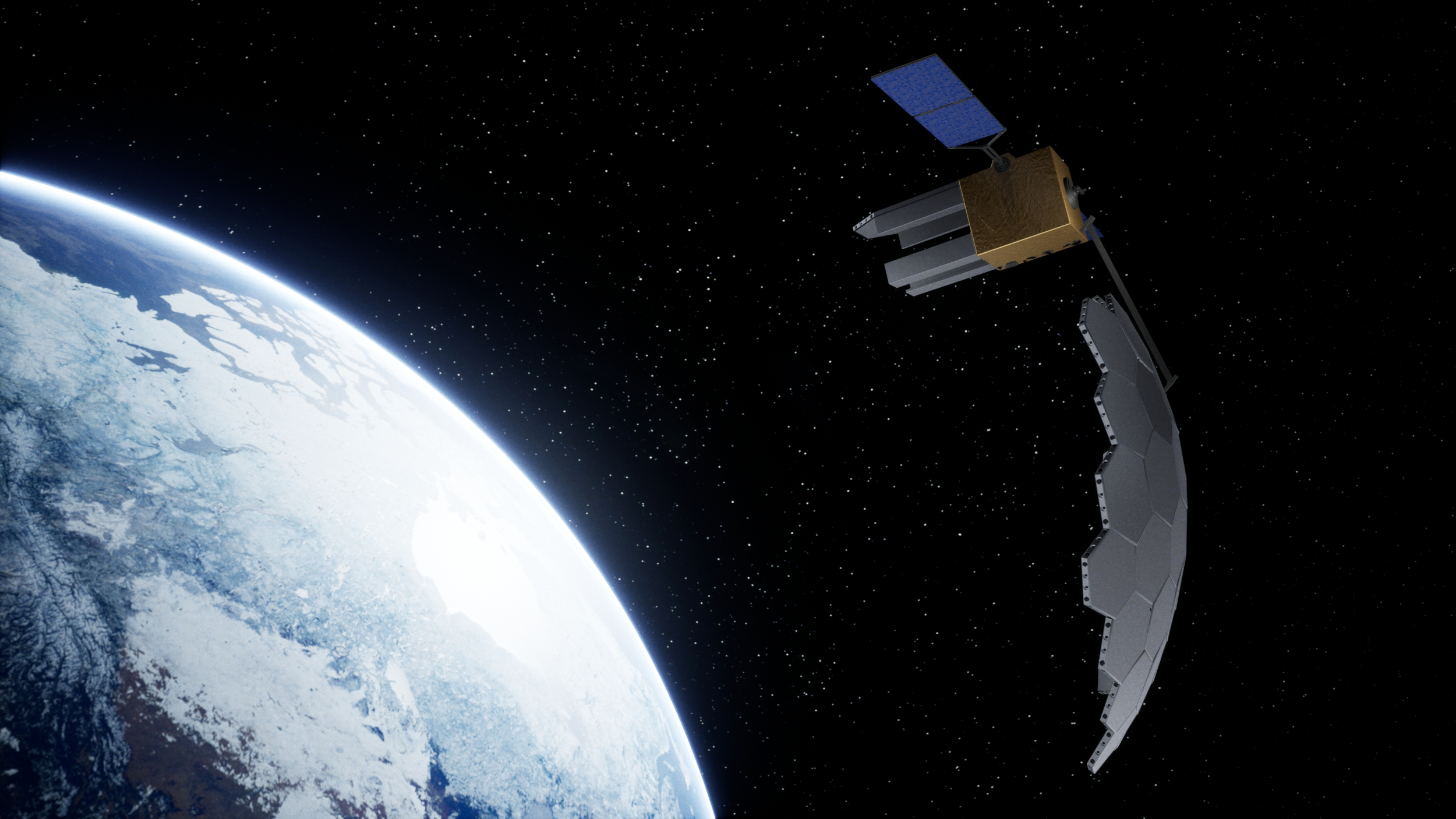

The filing isn't just about launching more satellites into the void. This is fundamentally different. Space X is proposing to build an "orbital data center" that runs on solar power and provides computing capacity specifically designed to handle artificial intelligence workloads. Think about that for a second. Instead of processing AI requests on Earth-based servers powered by increasingly strained electrical grids, Space X wants to move that computation into space.

Why does this matter right now? Because AI is consuming electricity like nothing we've seen before. Data centers training and running large language models are voracious power consumers. Google, Microsoft, and Meta are all racing to build bigger, more efficient data centers. Meanwhile, the power grid is struggling to keep pace. Solar panels in space? Unlimited, consistent energy. That's not just a competitive advantage—that's a fundamental reimagining of computing infrastructure.

The filing details are sparse but telling. Space X is asking for permission to "deploy a system of up to one million satellites to operate within narrow orbital shells spanning up to 50 km each." The company emphasizes that orbital data centers represent "the most efficient way to meet the accelerating demand for AI computing power" because they harness solar power with "little operating and maintenance costs."

But here's where things get complicated. The FCC historically scales back Space X's ambitions. In 2020, the company requested permission to launch nearly 30,000 Starlink satellites. The FCC approved 7,500. Then, earlier this year, Space X asked for 7,500 more, and the FCC said yes. So what happens when you ask for a million?

This proposal arrives at a moment when the space economy itself is transforming. Companies like Axiom Space are building commercial space stations. Blue Origin is expanding suborbital tourism. But nobody's thinking as big as Space X. And that's both the appeal and the controversy.

The Current State of Satellite Constellations: How We Got Here

To understand why Space X's proposal is so radical, you need to understand where satellite technology actually stands today.

When Starlink launched its first satellites in 2019, the space industry was skeptical. A constellation of thousands of small satellites, all linked together, providing broadband to the entire planet? It sounded like science fiction. But it worked. Starlink now provides internet connectivity in remote areas where fiber and cable operators have zero interest in building infrastructure. A farmer in rural Montana can get gigabit speeds that rival urban broadband. That's revolutionary for connectivity, but it's also just the beginning of what Space X believes is possible.

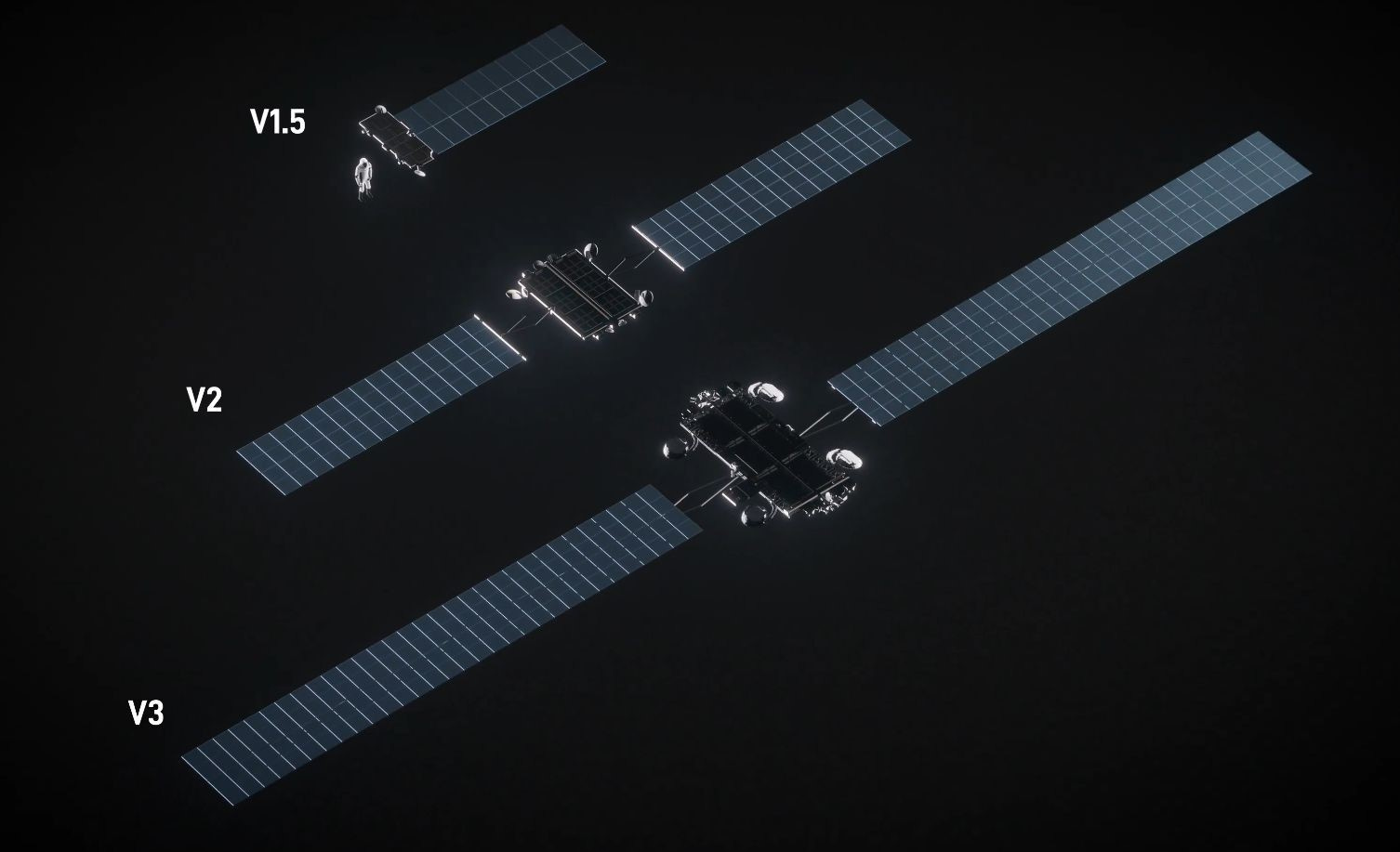

The current Starlink constellation demonstrates several key capabilities that make the orbital data center proposal credible. First, Space X has proven it can manufacture and deploy satellites at scale. The company launches new Starlink satellites regularly, in batches of 50-60 at a time. The production pipeline is mature. The launch logistics are dialed in. This isn't theoretical anymore.

Second, the ground station infrastructure exists. Starlink users have small dishes on their roofs that communicate with satellites overhead. For an orbital data center, you'd need more sophisticated ground stations, but the fundamental architecture is already proven. Space X has installed thousands of ground stations around the world. The network is distributed, redundant, and operational.

Third, and perhaps most importantly, Space X has demonstrated that satellite-to-satellite communication works. Starlink satellites are connected to each other, creating a mesh network in space. Data doesn't always travel directly from satellite to ground station to your device. Instead, it can hop between satellites, routing around congestion or failures. This same capability would be essential for an orbital data center. Compute requests would need to be routed intelligently across the constellation.

Compare this to other satellite internet providers like Amazon's Project Kuiper or One Web. Both are building substantial constellations, but neither has the production scale or operational experience that Space X brings to the table. Kuiper is still in the testing phase. One Web, after emerging from bankruptcy, is rebuilding its constellation from scratch. Space X already has 9,600 working satellites in orbit.

That operational advantage matters enormously when you're talking about deploying something a hundred times larger. The lessons learned from operating Starlink—thermal management, power systems, software updates, collision avoidance, deorbiting obsolete satellites—all become crucial as you scale up. A million satellites would be exponentially more complex to manage, but Space X has the foundational experience.

The economics have shifted too. Launch costs have plummeted thanks to Space X's Falcon 9 reusability. A decade ago, launching a satellite cost tens of millions of dollars. Now, with reusable rockets, the marginal cost of adding another satellite to a launch is relatively modest. The rocket is going up anyway. You might as well pack it with 50-60 more satellites.

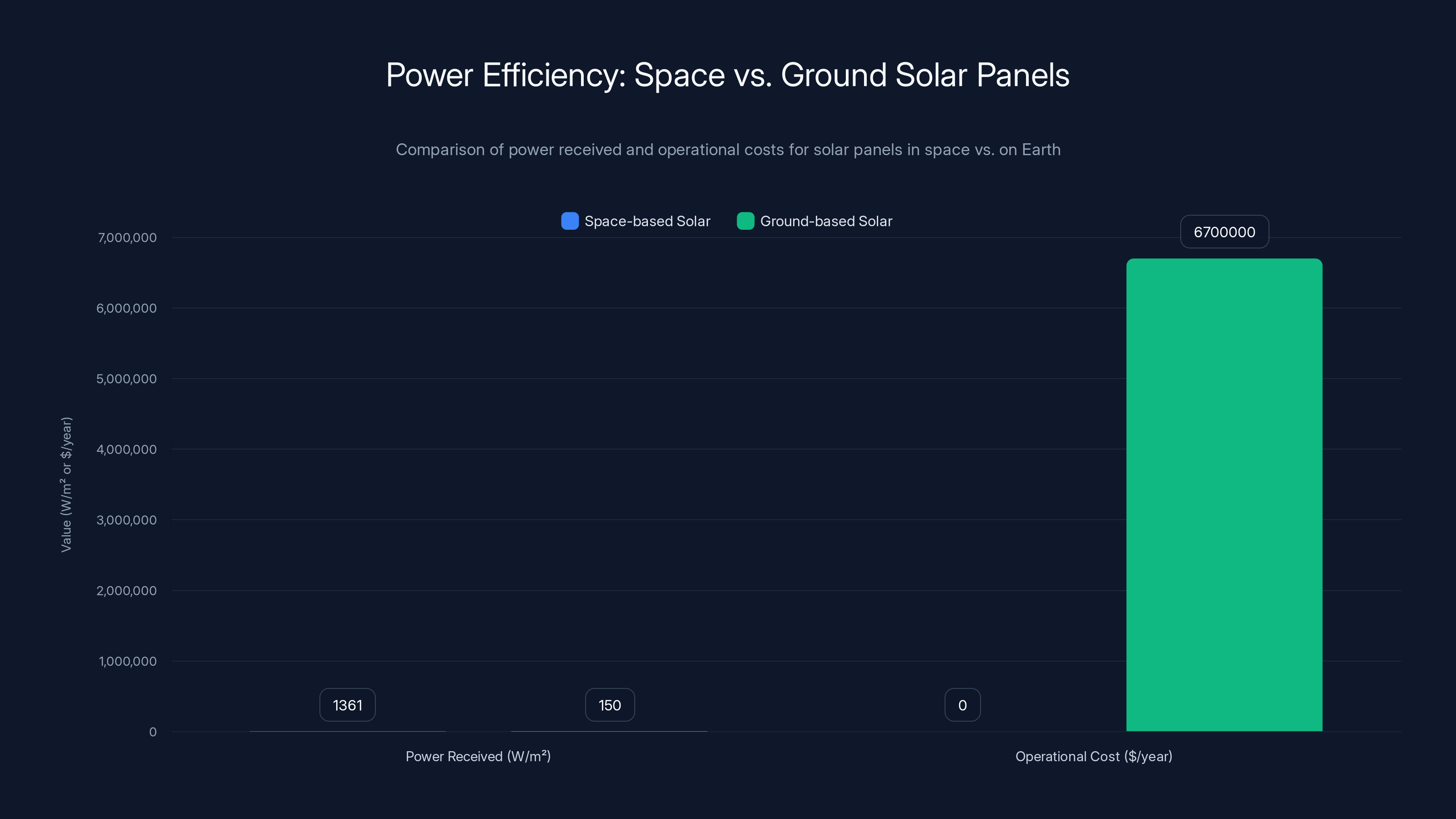

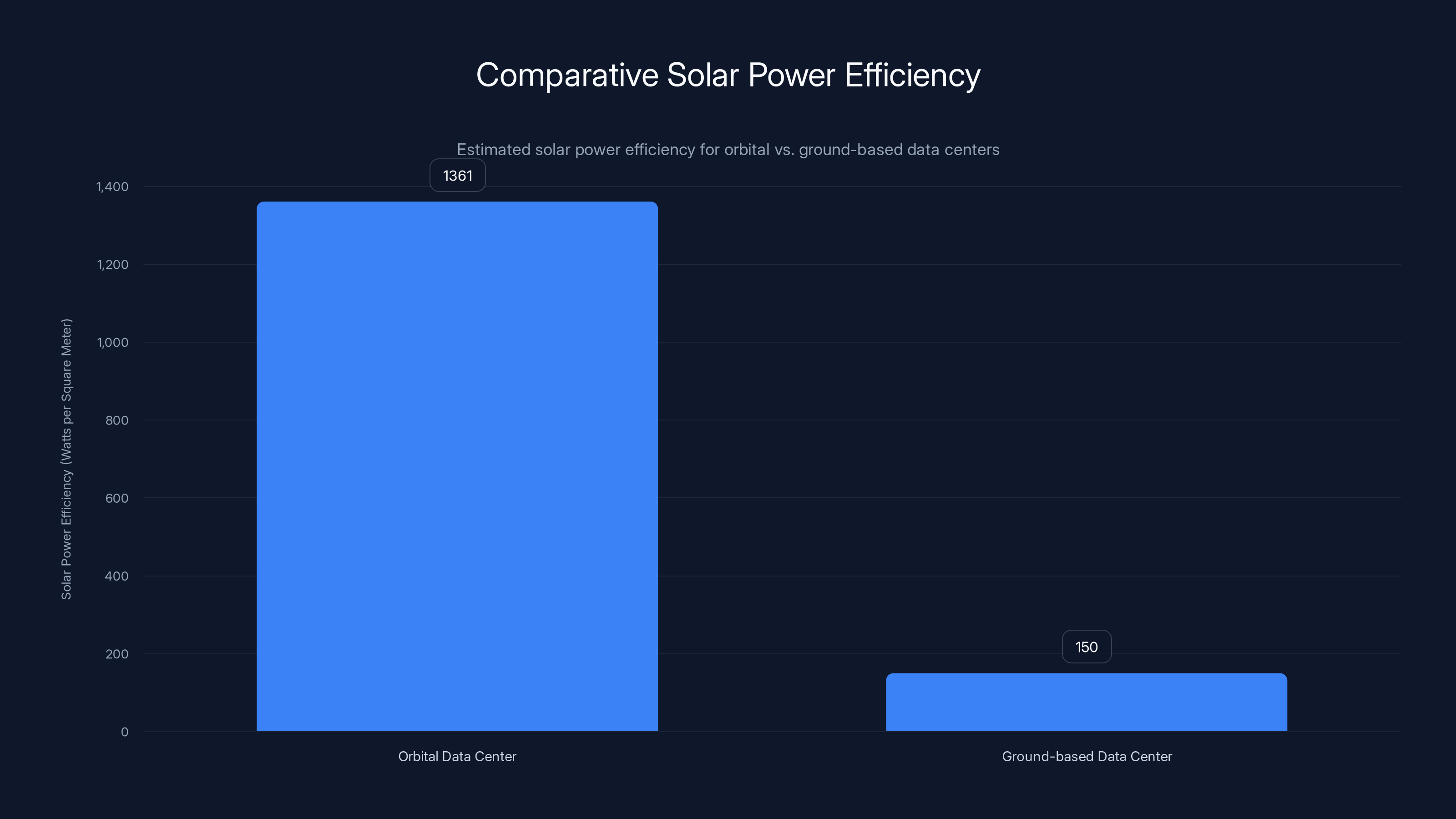

Space-based solar panels receive approximately 9 times more power than ground-based ones and have negligible operational costs, highlighting their efficiency despite higher initial deployment costs. (Estimated data)

Why AI Computing Demands Are Pushing This Ambition

None of this makes sense without understanding the underlying driver: AI is fundamentally transforming computing infrastructure requirements.

Consider what happens when you run a large language model. Open AI's GPT-4, Anthropic's Claude, Google Deep Mind's models—they all require massive GPU or TPU clusters to function. A single inference request might involve billions of mathematical operations across thousands of compute nodes. That's not just electricity-intensive. It's also latency-sensitive. Delays compound. Inefficiencies add up.

The power consumption is staggering. Industry estimates suggest that training a state-of-the-art language model consumes between 1-100 megawatt-hours of electricity, depending on model size and optimization. For inference at scale, a popular model running millions of queries per day might consume 5-10 megawatts continuously. That's the electricity draw of a small industrial facility, running 24/7.

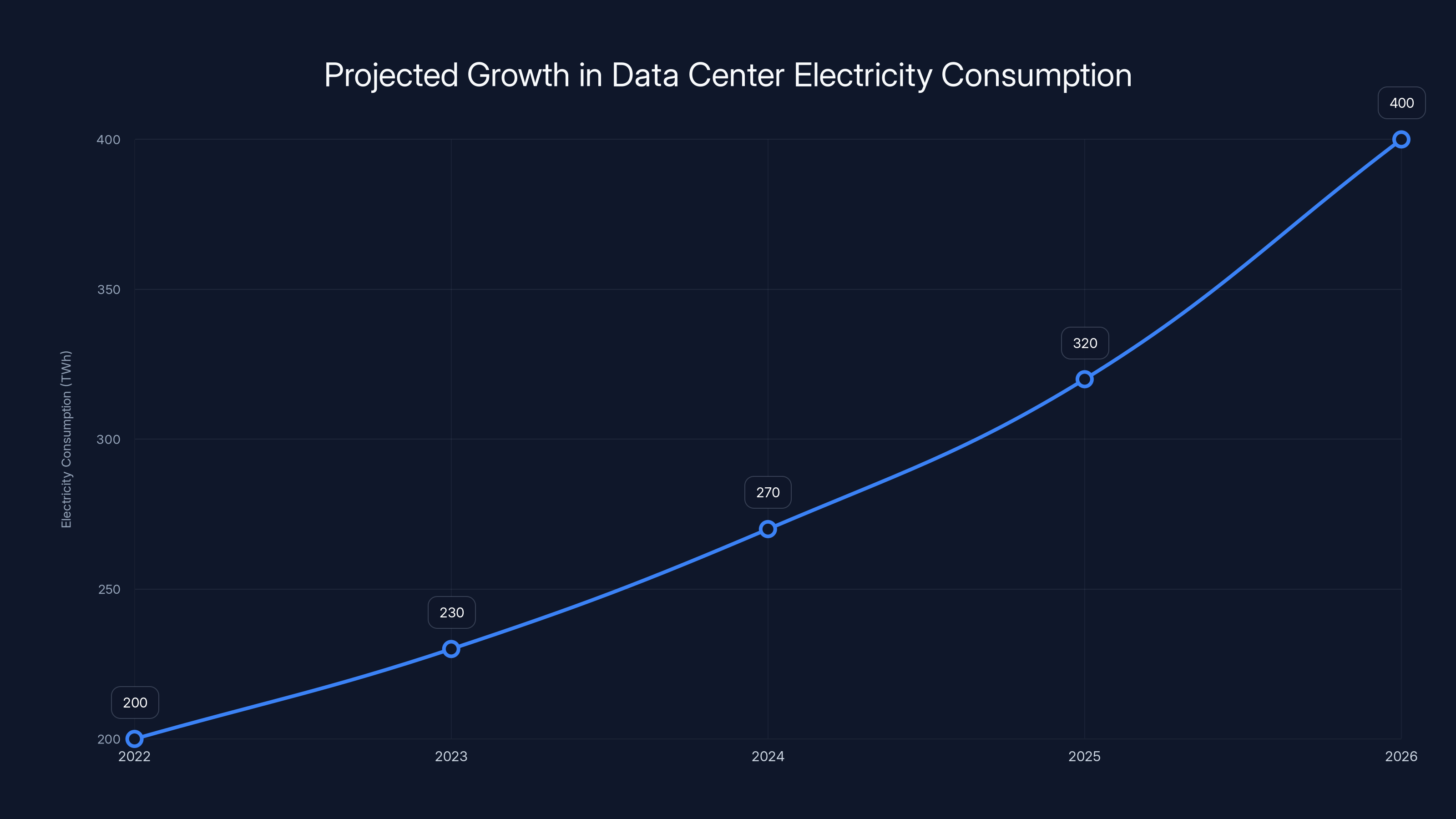

Where does that electricity come from? Increasingly, it's straining the grid. The International Energy Agency projects that data center electricity consumption will double between 2022 and 2026. AI data centers will account for a substantial portion of that growth. Some regions are already experiencing power shortages specifically because of data center demand.

This creates a problem for companies running AI services. You want to place data centers near your customers to minimize latency. But you also need cheap, reliable electricity. These two requirements increasingly conflict. Your customer in Tokyo needs low latency to a data center in Tokyo. But Tokyo's power grid is expensive and constrained. You could build a data center, but it would cost a fortune to operate.

Space changes this equation entirely. Solar panels in orbit receive constant, unfiltered sunlight. No clouds. No seasonal variation. An orbital data center could theoretically generate far more power per square meter than any Earth-based solar installation. And that power is available at any latitude, any time of year, at full intensity.

There's also a latency angle that's often overlooked. Current AI inference happens at data centers located thousands of kilometers away from end users. A query travels from your device to a data center, the model processes it, and the response travels back. Even at the speed of light (299,792 kilometers per second), that round trip introduces noticeable delay. An orbital data center positioned at a lower altitude than geostationary orbit could serve users with latency competitive with ground-based infrastructure, while offering unlimited power and no geographical constraints.

Elon Musk and Space X aren't the only ones thinking about space-based computing. Various researchers and companies have explored concepts like orbital manufacturing data centers, edge computing satellites, and space-based AI accelerators. But Space X is the first to seriously pursue deploying this at civilization-scale magnitude.

The timing is also crucial. Five years ago, AI was a niche technology. Today, it's becoming essential infrastructure. The power crunch is real. The demand is explosive. And the technology to deploy satellites at scale is finally mature enough to make the proposal feasible.

Orbital data centers receive approximately 1361 watts per square meter of solar power, significantly more than the 100-200 watts per square meter typical for ground-based centers. Estimated data.

Understanding the Orbital Data Center Architecture

Let's dig into what an orbital data center would actually look like, because Space X hasn't released detailed specifications, and speculation is rampant.

First, imagine a traditional hyperscale data center. You have thousands of GPUs or TPUs arranged in racks. Those compute nodes are connected by high-bandwidth, low-latency networking. They share access to massive amounts of memory and storage. Cooling systems manage thermal output. Power systems distribute electricity efficiently. The whole facility is carefully engineered to maximize performance while minimizing waste.

Now take that design and make it work in space. Every single challenge becomes harder.

Thermal management is the first problem. On Earth, data centers use enormous cooling systems. Giant fans draw ambient air (or water) across hot components and dump heat into the environment. In space, there's no air. There's no water to recirculate. Thermal energy has to radiate away into the void. That's actually more efficient in theory, but the engineering is complex. You need large radiator panels to dissipate heat across the vacuum of space.

Power systems need to be completely self-contained. Orbital platforms can't plug into the electrical grid. They rely entirely on solar panels. A one-megawatt data center would need substantial solar panel area—probably hundreds or thousands of square meters. Those panels need to maintain orientation toward the sun, which requires attitude control systems. And at night (roughly half the orbit for satellites at lower altitudes), you need batteries to store energy generated during daylight portions of the orbit.

Actually, wait. This is where Space X's filing gets clever. It specifies "narrow orbital shells spanning up to 50 km each." That's not describing a single altitude. It's describing a range. And more importantly, it's hinting at something called sun-synchronous orbits. If you position satellites in the right orbit, you can maintain constant illumination from the sun. You never enter Earth's shadow. Power generation becomes continuous.

For a communications constellation like Starlink, this doesn't matter much. But for a power-hungry data center, it's transformative. Continuous solar power means you don't need massive battery systems. You can run full compute loads 24/7 without power interruption.

Networking is another major consideration. Orbital data center nodes need to communicate at very high bandwidth. Within the constellation, satellite-to-satellite links would probably use laser or millimeter-wave communication. These technologies can transmit data at terabit per second rates over short distances. Between the constellation and Earth, you'd need substantial ground stations with enormous antenna arrays to handle the data flow.

But here's the challenge: latency becomes a factor. A query arrives at a ground station, travels to the nearest orbital node, gets routed through multiple compute nodes in the constellation, and the result comes back down. Even at the speed of light, this takes time. For latency-critical AI workloads, this might be problematic. For batch processing, inference on pre-computed results, and model training, it's probably acceptable.

Software is perhaps the most complex component. Managing a million satellites requires sophisticated distributed computing frameworks. You need automatic load balancing across the constellation. You need failure detection and recovery. You need mechanisms to detect hardware faults, route around them, and maintain service continuity. You need ways to push software updates to a million satellite nodes without disrupting service. These are solvable problems, but they're not trivial.

There's also the question of redundancy. Satellites fail. Micrometeorite impacts. Solar flares. Radiation damage. Thermal cycling. Any number of things can go wrong with a satellite. In a constellation this massive, failures would be frequent. You'd need massive redundancy built in, with spare capacity to handle failed nodes.

The architecture would probably involve layered compute nodes at different orbital altitudes. Lower latency nodes closer to Earth for interactive workloads. Higher altitude nodes for batch processing and less latency-sensitive tasks. Different orbital planes for geographic distribution. Storage nodes holding model weights and training data. Network nodes handling inter-node communication.

It's complex. It's ambitious. But it's not theoretically impossible.

The Power Efficiency Argument: Solar Energy in Space

Space X's filing emphasizes that orbital data centers would use "solar power with little operating and maintenance costs." This is the core business case, and it deserves scrutiny.

First, the facts about space-based solar. A solar panel in orbit receives roughly 1,361 watts of power per square meter—the solar constant. On Earth's surface, after passing through the atmosphere and accounting for cloud cover, you typically get 100-200 watts per square meter on a good day. That's roughly a 7-13x advantage right there.

But space solar has complications. Solar panels degrade under radiation exposure and thermal cycling. They need orientation control systems to track the sun. They accumulate dust and micrometeorite damage over time. Current space-rated solar panels have efficiency around 30%, similar to high-performance terrestrial panels.

Still, even accounting for these factors, space-based solar is dramatically more efficient than ground-based options. For a one-megawatt data center, you might need roughly 4,000 square meters of solar panels in orbit. That's substantial, but a million-satellite constellation could incorporate that easily across the total deployed area.

Now consider the operational costs. A ground-based data center pays for electricity every month. That cost varies by location but typically ranges from 3-10 cents per kilowatt-hour in developed countries. Over a year, powering a single megawatt continuously costs roughly

An orbital data center has high initial capital costs—manufacturing and launching satellites is expensive. But once deployed, the operational electricity cost is essentially zero. You pay for maintenance and replacement of failed components, but you're not continuously paying a utility bill.

Let's do rough math. Assume launching a satellite costs

Compare that to a ground-based data center constellation of equivalent compute capacity. You'd need expensive land, power infrastructure, cooling systems, redundant electricity feeds, and continuous power payments. The total cost of ownership might be comparable or even higher when you factor in the energy costs alone.

But this glosses over complexity. The capital costs of space infrastructure are notoriously hard to predict. Every Space X cost estimate has historically been optimistic. The true cost might be 2x or 3x higher than these rough calculations.

There's also the question of practical efficiency. A theoretical 7-13x advantage in raw solar power doesn't directly translate to 7-13x cheaper compute. You need to account for power conversion losses, transmission losses, battery inefficiency (during nighttime orbits, if applicable), and thermal management overhead.

Real-world space power systems typically achieve 60-70% overall efficiency from solar panel to usable compute power. Ground-based data centers can achieve similar or better efficiency with modern power delivery and cooling systems. So the advantage might be more like 3-5x in practical terms, not 7-13x.

Still, 3-5x is substantial. That's the difference between a profitable business and a money-losing one. That's why Space X is pursuing this.

SpaceX's proposed orbital data center would increase their satellite count to 1 million, dwarfing current constellations. Estimated data for context.

FCC Review: What's the Process and What Could Go Wrong?

Here's where the regulatory rubber meets the orbital road. Space X doesn't get to just launch a million satellites. The FCC has to approve it.

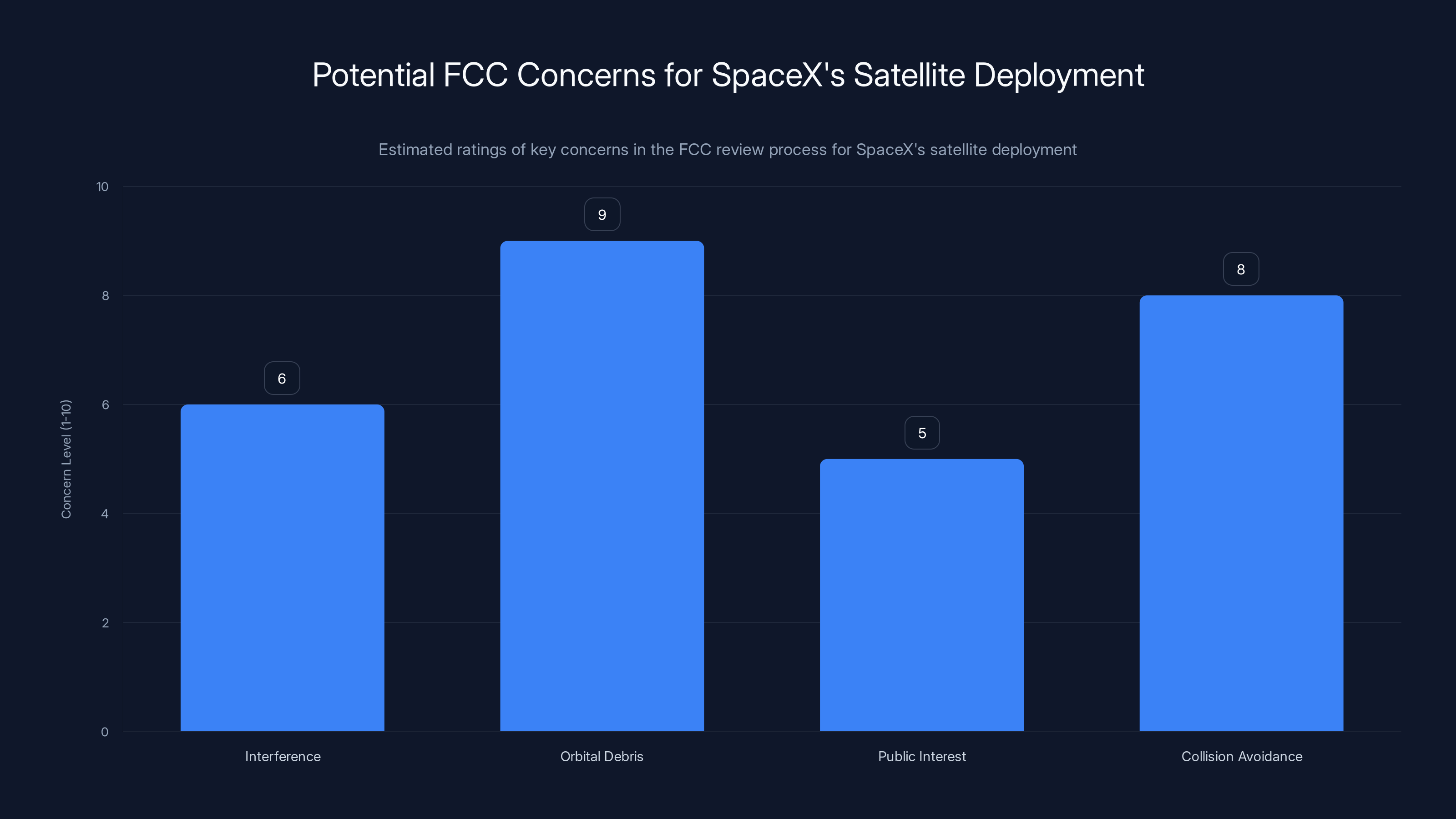

The FCC's authority over satellite deployments comes from the Communications Act. The agency grants licenses for orbital slots and frequency allocations. Space X must demonstrate that its proposal doesn't interfere with existing communications systems, doesn't create excessive orbital debris, and serves legitimate public interest purposes.

For Starlink, the FCC historically approved Space X's requests, though often scaled down from initial proposals. The agency has been relatively permissive of Space X's constellation growth, recognizing that satellite broadband serves underserved communities.

But a million satellites is different. The scale alone raises questions.

First, there's space debris. Every satellite in orbit is potential debris if it malfunctions or collides with something else. Orbital debris travels at roughly 17,500 miles per hour. At those speeds, even a millimeter-sized paint fleck can damage or destroy a satellite. A swarm of a million satellites dramatically increases the likelihood of collisions. One collision creates debris that causes more collisions in a cascade effect called Kessler Syndrome.

The FCC will likely require Space X to demonstrate robust collision avoidance systems. The company would need to show that it can track all million satellites, predict potential collisions, perform maneuvers to avoid them, and ensure that any deorbited satellites burn up in the atmosphere rather than creating long-lived debris.

Space X has actually been working on this. Starlink satellites are designed to deorbit at end-of-life, burning up completely in the atmosphere. The company also routinely performs collision avoidance maneuvers for existing satellites. But scaling this to a million units is a different challenge.

Second, there's spectrum and interference. The FCC grants licenses for specific frequency bands. If two satellite operators use overlapping frequencies in the same orbital region, they interfere with each other. The FCC will need to determine whether one million satellites can coexist with existing communications satellites without mutual interference.

Amazon's Kuiper constellation, One Web, and various other satellite operators are all competing for similar frequency allocations. A million Space X satellites could potentially crowd out competitors. The FCC might view this as anti-competitive and reject or drastically scale back the proposal.

Third, there's the question of whether an orbital data center serves "legitimate public interest." The FCC approved Starlink partly because it provides broadband to remote areas. But an orbital data center primarily serves Open AI, Google Deep Mind, Microsoft, and other AI companies. Does that count as public interest? The FCC might argue that it does—these AI services benefit the general public. Or it might argue that Space X is primarily seeking private benefit. The regulatory calculus is uncertain.

Historically, the FCC has scaled back Space X's proposals. The 30,000-satellite request became 7,500. The next 7,500 request was approved, but there were lengthy review periods. For a million satellites, expect extensive review, multiple rounds of comments from competitors and interest groups, and likely a final approval that's substantially smaller than the initial request.

A realistic scenario might be that Space X ultimately deploys 100,000-300,000 satellites. Enough to create meaningful orbital data center capability. Not enough to threaten space traffic. Not so large that it forecloses opportunities for competitors.

But that's speculation. The FCC review process is opaque, influenced by political considerations, and unpredictable.

Environmental and Space Traffic Considerations

Beyond the FCC's immediate regulatory authority, deploying a million satellites raises broader environmental and space sustainability questions.

One often-overlooked impact is light pollution. Starlink satellites are visible from the ground, especially shortly after launch before they reach operational altitude. Astronomers have been vocal about the interference with telescope observations. A million satellites would be dramatically more visible, potentially hampering ground-based astronomy.

Space X has been working on this problem. The company developed a darkening coating that reduces satellite brightness. But for a million satellites, the cumulative effect would still be substantial.

There's also the question of atmospheric pollution from deorbiting satellites. Current plans involve controlled atmospheric reentry where satellites burn up. But a million satellites means a million reentry events over time. The cumulative effect of aluminum oxide particulates from satellite burnup in the upper atmosphere is poorly understood. Could it harm the ozone layer? Impact stratospheric chemistry? These questions need rigorous study.

On the space traffic side, a million satellites fundamentally changes orbital operations. Every spacecraft launching to orbit needs to be aware of satellite swarms. Every maneuver requires collision checking against a million objects. This isn't impossible, but it requires new infrastructure and coordination mechanisms.

Space X proposed something called the Space Development Agency, which coordinates space traffic among military and commercial operators. But current capacity exists to track roughly 25,000 orbital objects reliably. A million satellites exceeds this by 40x.

The industry would need to develop automated, decentralized collision avoidance systems. Satellites would need to communicate their positions continuously. They'd need to execute autonomous maneuvers to avoid potential collisions. The technical feasibility is questionable with current technology.

There's also a geopolitical dimension. The United States has long pursued space superiority. A constellation of one million U.S.-based satellites would give American technology and military interests an enormous advantage in space. Other nations, particularly China and Russia, are unlikely to accept this without developing counter-capabilities. The orbital environment could become crowded with competing mega-constellations.

Orbital debris and collision avoidance are major concerns for the FCC in approving SpaceX's satellite deployment, with high ratings of 9 and 8 respectively. Estimated data.

Competing Visions: Other Companies and Approaches

Space X isn't the only company thinking big about orbital infrastructure. But they're ahead of everyone else.

Amazon's Project Kuiper is the closest competitor. The company is deploying a constellation of roughly 3,200 satellites providing broadband internet. That's substantially smaller than even current Starlink, much less the million-satellite proposal. Amazon is moving at a slower pace, with a first launch scheduled for early 2025. The company hasn't discussed using Kuiper for computing or data center purposes.

One Web, after emerging from bankruptcy, is rebuilding its constellation. But again, the scale is limited compared to Space X. One Web focuses on broadband, not computing infrastructure.

On the pure computing side, various researchers have published papers about space-based data centers. NASA has funded concept studies. But nobody is aggressively pursuing deployment like Space X.

There's also the terrestrial alternative. Companies like NVIDIA and AMD are developing increasingly efficient AI accelerators. Cooling technologies are improving. Data center architectures are optimizing. The efficiency gap between ground-based and space-based computing is narrowing.

Some argue that Space X should focus on improving terrestrial infrastructure rather than pursuing space-based alternatives. Renewable energy sources like wind and solar are becoming cheaper. Geothermal energy offers consistent, clean power. Hydroelectric dams and other water-based systems can provide massive compute capacity with existing technology.

But Space X's perspective is different. Space offers unlimited power, unlimited cooling, unlimited space for infrastructure. Why constrain yourself to Earth when you can expand outward?

Technical Challenges: Engineering at the Million-Satellite Scale

Let's talk about the actual challenges of engineering and operating a million satellites. This isn't just about scaling up Starlink 100x. The problems multiply exponentially.

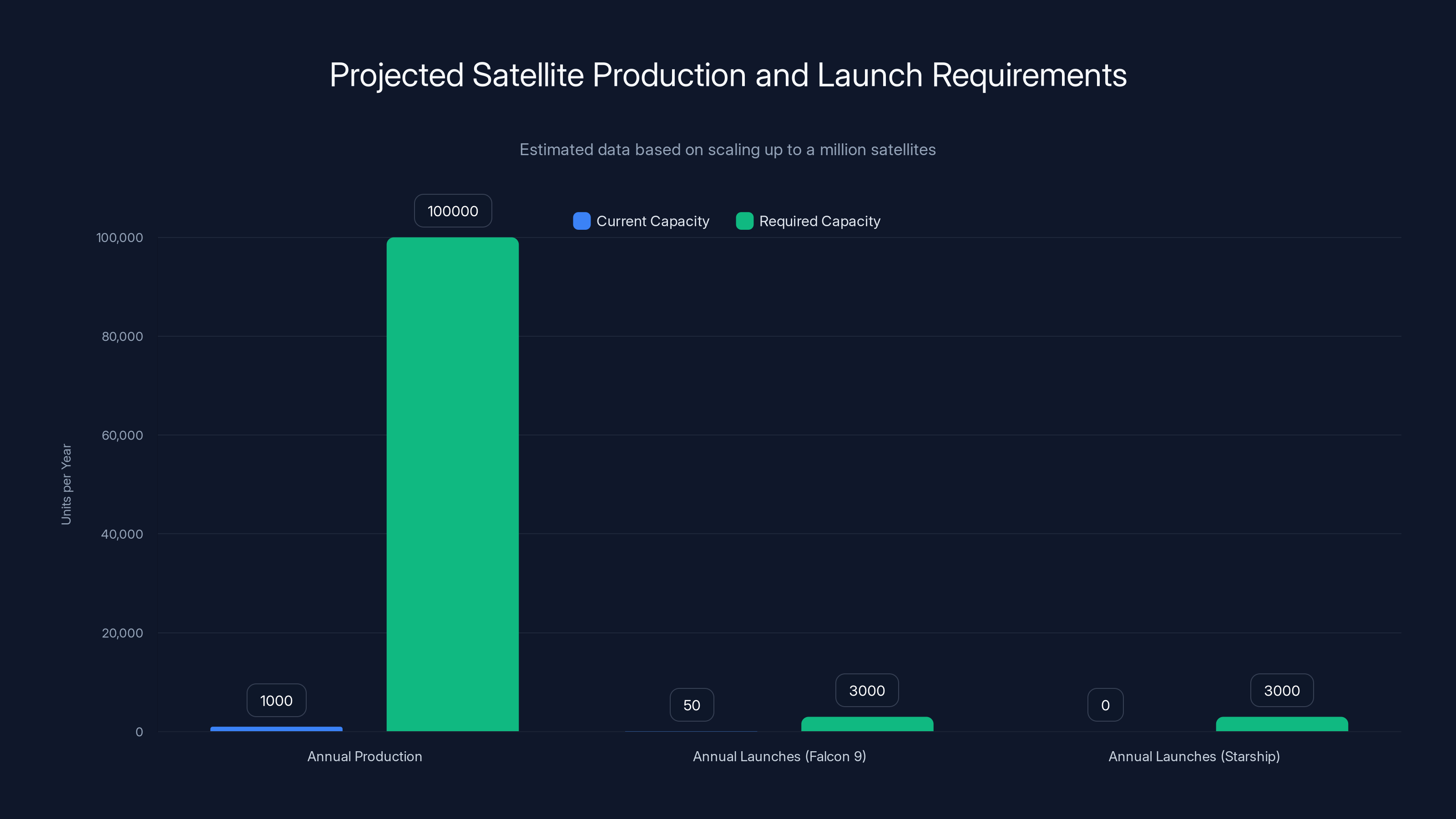

First, manufacturing. Space X currently produces Starlink satellites at a rate of roughly 1,000 per year. Ramping up to deploy a million satellites would require producing roughly 10,000-20,000 satellites annually for 50-100 years, or 100,000+ annually for a decade. That's not just a factory expansion. That's building an entire industrial ecosystem for space manufacturing.

Component sourcing becomes a bottleneck. Modern satellites use specialized semiconductors, sensors, and communications equipment. The global supply chain for these components would need to expand 10-100x. This might require developing new manufacturing capacity, new suppliers, new quality control processes.

Quality control is critical. A defective satellite isn't just a financial loss. It's potential debris. Each satellite needs to function correctly, execute maneuvers, maintain attitude control, and eventually deorbit properly. A single percent failure rate among a million satellites means 10,000 failed units. Even 0.1% failure is 1,000 failed satellites.

Second, deployment logistics. Space X would need to launch a million satellites. Even with Falcon 9 carrying 60 satellites per mission, that's roughly 17,000 launches. At current rates of 40-50 launches per year, deployment would take centuries.

Space X is developing Starship, a fully reusable super-heavy-lift vehicle. Starship could theoretically carry 400+ Starlink satellites per launch. That reduces the requirement to roughly 2,500-3,000 launches. But that's still a massive undertaking. The company would need to operate Starship at a frequency never achieved before.

Launch cadence creates another bottleneck. The launch pad and assembly infrastructure can only support a certain number of launches per month. Space X's current facilities are designed for roughly 50 launches annually. To support 300-400 launches annually (necessary for rapid deployment), the company would need to build multiple launch facilities, multiple production lines, and massive logistical networks.

Third, orbital mechanics and traffic management. The filing mentions "narrow orbital shells spanning up to 50 km each." This implies multiple orbital layers at different altitudes. Precise deployment of one million satellites into correct orbital planes, at specific altitudes, with proper spacing, is extraordinarily complex. Any error in deployment could result in collisions or incorrect positioning.

Traffic management is equally challenging. At any given time, roughly 100-200 Space X satellites are maneuvering—adjusting altitude, avoiding debris, or repositioning. With a million satellites, you might have 10,000+ simultaneously performing maneuvers. The coordination required is immense.

Fourth, ground station infrastructure. Current Starlink relies on thousands of ground stations to relay signals to and from satellites. An orbital data center would require ground stations with far greater bandwidth and precision. You'd need major facilities in multiple continents to maintain continuous connectivity and balanced load distribution across the constellation.

These aren't insurmountable challenges. They're substantial engineering problems, but Space X has demonstrated the capability to solve difficult space problems. The company went from zero orbital rockets to reusable rockets and a functional satellite internet service in less than two decades.

Data center electricity consumption is projected to double from 2022 to 2026, driven by AI computing demands. Estimated data based on industry trends.

The Economic Case: Who Benefits and Who Pays?

If Space X deploys an orbital data center constellation, who actually benefits? And more importantly, who pays for it?

The direct beneficiaries would be AI companies running inference on their models. If Space X can deliver compute capacity at significantly lower cost than ground-based data centers, those companies would shift workloads to the orbital platform. That's billions of dollars in potential revenue for Space X.

End users of AI services would benefit indirectly. Cheaper compute might translate to cheaper or better AI services. If Open AI's costs drop 30-50% by using orbital infrastructure, some of those savings might flow to consumers through lower subscription prices or better model capabilities.

There's also a geopolitical benefit for the United States. The country maintains technological and strategic dominance in space. A million-satellite constellation controlled by an American company extends that advantage. Other nations would be dependent on this infrastructure for their own AI capabilities.

On the cost side, Space X bears the enormous capital expenditure. Launching and maintaining a million satellites costs tens of billions of dollars. That capital comes from Space X's revenues (if the company is profitable) or from external investors (if seeking funding).

There's also a broader societal cost. Orbital resources are finite. Space isn't infinite, even if it feels that way. A million satellites occupy orbital real estate that other operators (governments, competitors, future innovators) could use. There's a scarcity cost that isn't reflected in Space X's business model.

Climate implications are mixed. Building an orbital data center avoids terrestrial electrical generation, which means less coal, gas, or nuclear energy consumption. That's positive for carbon emissions. But manufacturing and launching a million satellites consumes resources and energy. The net climate impact might be slightly negative, neutral, or slightly positive depending on assumptions.

There are also labor implications. Manufacturing a million satellites might create substantial employment. But it would also potentially displace workers in terrestrial data center operations, if those facilities become less competitive.

The economic analysis ultimately depends on whether the orbital data center actually works as envisioned. If latency, power efficiency, and reliability all match theoretical expectations, the business case is compelling. If real-world performance falls short, the entire venture becomes economically dubious.

Alternative Approaches to Solving the AI Power Crunch

Before concluding that an orbital data center is inevitable, let's consider alternatives.

Terrestrial renewable energy expansion is the most obvious. The cost of solar and wind power has plummeted. Grid-scale battery storage is improving. A concerted effort to build renewable energy infrastructure could power AI data centers indefinitely without the complexity of space-based systems. This approach has the advantage of mature technology and lower capital requirements.

Nuclear power offers another path. Modern small modular reactors (SMRs) can be built near data center facilities, providing reliable, low-carbon power. Companies like Terra Power are developing advanced reactor designs. The advantage is concentrated, scalable power. The disadvantage is lengthy permitting and construction timelines.

Geothermal energy provides consistent baseload power with minimal land footprint. Iceland and New Zealand already power data centers with geothermal systems. Expanding this approach globally would require developing geothermal resources in more regions, but it's technologically straightforward.

Efficiency improvements in AI models themselves could reduce compute requirements. Some researchers are exploring sparse models, pruned networks, and other techniques that maintain performance while reducing computational demands. If models could become 10x more efficient, the power crunch becomes manageable with terrestrial infrastructure.

Quantum computing, if successfully developed, could solve certain AI problems far more efficiently than classical computers. The hype around quantum AI is overblown, but breakthroughs in specific domains could reduce the raw compute requirements for certain tasks.

Each of these alternatives has advantages and disadvantages compared to space-based infrastructure. The optimal solution probably involves a combination: renewable energy for some loads, nuclear for baseload, geothermal where available, efficiency improvements in software, and space-based systems for specific high-value applications.

Space X's proposal isn't necessarily an either-or proposition. Even if terrestrial solutions improve, orbital infrastructure could still provide incremental capacity for the most demanding applications.

To deploy a million satellites, production must increase to 100,000 units annually, with 3,000 launches needed using Starship. Estimated data.

Timeline and Realistic Deployment Scenarios

Let's think realistically about when an orbital data center constellation might actually become operational.

First, the FCC review and approval. Historical precedent suggests this takes 1-3 years for major proposals. Space X filed this proposal in January 2026. Assuming a typical timeline, FCC approval (likely for a scaled-down version) might come in 2027-2028.

Second, development and testing. Space X would need to build and test prototype orbital data center nodes. This could run in parallel with FCC review, but you're looking at 2-4 years of engineering work.

Third, manufacturing ramp-up. Building the production capacity to manufacture 100,000+ satellites annually requires new factories, supply chain development, and process optimization. This probably takes 3-5 years.

Fourth, deployment. Even with aggressive launch schedules, deploying a large constellation takes time. Space X might deploy 10,000-50,000 satellites in the first operational phase (roughly 2-5 years), then continue expanding capacity.

That puts meaningful orbital data center capability somewhere in the 2029-2032 timeframe. The full constellation, if ever deployed, might take 15-20 years.

But this timeline assumes everything goes smoothly. Regulatory delays, technical challenges, manufacturing bottlenecks, or economic downturns could extend this significantly.

Moreover, Space X might never deploy the full million satellites. The company could stop at 300,000-500,000 if that provides sufficient compute capacity for customer demand. The filing asks for permission to deploy up to a million, but that doesn't mean Space X intends to actually deploy that many.

What This Means for the Future of Computing

Regardless of whether Space X's specific proposal succeeds, the orbital data center concept represents a fundamental shift in how we might approach computing infrastructure.

For decades, computing has been grounded. Data centers are built on Earth, powered by terrestrial electricity grids, cooled with water or air. That paradigm has served us well, but it's hitting constraints. The power grid can't easily expand capacity. Real estate is expensive. Cooling is challenging. These aren't insurmountable problems, but they're real.

Space-based computing removes some of these constraints. It's not a magic solution—there are new constraints in space (vacuum, radiation, isolation). But those constraints might be easier to manage than terrestrial ones.

If Space X (or someone else) successfully deploys orbital data centers, it would open possibilities. Distributed compute across multiple continents with latency similar to terrestrial systems. Unlimited power for energy-intensive applications. Redundancy that's geographically distributed across the planet. These capabilities could transform how we build infrastructure.

For AI specifically, orbital computing might enable applications that are impractical with current terrestrial infrastructure. Real-time AI inference at global scale. Distributed training across geographically diverse nodes. AI running in the very infrastructure that connects the world together.

It's speculative, but not unreasonable. Space X has a track record of pursuing ambitious visions and achieving them, often faster than skeptics expect.

The Immediate Outlook: What Happens Next?

The FCC will examine Space X's proposal. The company will face opposition from competitors, environmentalists, and space security advocates. There will be lengthy comment periods and potentially legal challenges.

Most likely outcome: Approval for a smaller constellation (100,000-500,000 satellites) rather than the full million. The FCC will likely impose conditions around debris mitigation, spectrum coordination, and astronomy protection.

Space X will proceed with development. The company will build prototype nodes, test orbital data center functionality, and demonstrate proof of concept. This happens over 2-4 years.

If testing succeeds, deployment begins. Space X accelerates Starship launches and starts filling orbital shells with compute nodes. By 2030-2031, the first commercially available orbital data center capacity comes online.

AI companies begin experimenting. Open AI, Google, Microsoft, and others run inference workloads on Space X's orbital infrastructure. Performance and cost data accumulate. If numbers are favorable, workload migration accelerates.

Competitors respond. Amazon might accelerate Project Kuiper and add compute nodes. Other companies might develop competing orbital infrastructure. China and Russia certainly explore similar capabilities.

Within a decade, orbital computing becomes another tool in the infrastructure toolkit—not dominant, but significant. It's used for specific applications where the advantages justify the complexity.

FAQ

What exactly is an orbital data center?

An orbital data center is a concept where computing infrastructure (servers, processors, storage) is deployed in orbit around Earth, rather than on the ground. Space X's proposal specifically refers to a constellation of satellites equipped with computing capabilities, powered by solar panels, and networked together to provide distributed computational resources. These would process artificial intelligence workloads while taking advantage of unlimited solar power available in space and avoiding terrestrial power grid constraints.

How would an orbital data center communicate with Earth?

Orbital data centers would use ground stations equipped with large antenna arrays to send and receive data from the satellite constellation. Within the constellation, satellites would communicate using laser or millimeter-wave inter-satellite links, creating a mesh network that routes information efficiently across the orbital nodes. Users would send AI inference requests to ground stations, which relay them to the nearest satellite node, and the computed results return through the same path. This is similar to how current Starlink satellites communicate, but with much higher bandwidth requirements for data center operations.

Why does Space X think an orbital data center would be more efficient than ground-based data centers?

Space X argues that orbital data centers offer superior efficiency primarily through unlimited solar power. Solar panels in orbit receive roughly 1,361 watts per square meter continuously (after accounting for inefficiencies), compared to 100-200 watts per square meter on Earth's surface. Additionally, space offers unlimited thermal capacity for cooling, as heat can be radiated directly into the vacuum without requiring air conditioning or water cooling systems. Space X emphasizes that operational costs would be minimal once deployed, since you're not continuously paying electricity bills to a utility company. However, this advantage is offset by high initial capital costs for manufacturing and launching satellites.

What regulatory approval is required for Space X to deploy a million satellites?

Space X requires approval from the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), which grants licenses for orbital operations and frequency allocations. The FCC must assess whether the constellation creates excessive orbital debris risk, interferes with existing communications systems, and serves the public interest. The agency has historically scaled back Space X's requests—the company initially requested nearly 30,000 Starlink satellites, but received approval for roughly 7,500-15,000. For the million-satellite proposal, the FCC review will likely take 1-3 years and probably result in approval for a smaller number than initially requested. Other regulatory bodies in different countries may also require approval for orbital operations in their regions.

Could a million satellites create a space debris problem?

Yes, this is a legitimate concern. A million satellites dramatically increases collision risk. At orbital velocities of 17,500+ mph, even tiny impacts can damage or destroy satellites, creating debris that causes more collisions in a cascade effect called Kessler Syndrome. Space X would need to demonstrate robust collision avoidance systems, continuous tracking of all satellites, and ensure proper deorbiting (controlled atmospheric reentry) when satellites reach end-of-life. The FCC typically requires that 90% of satellites deorbit within 25 years. For a million satellites, even a 1% failure rate would leave 10,000 pieces of long-lived debris—a catastrophic outcome. Rigorous safety engineering is essential.

How does latency compare between orbital and terrestrial data centers?

Orbital data centers would have higher latency than local terrestrial servers but potentially competitive with distant data center locations. Starlink satellites operate at 340-500 km altitude, resulting in roughly 25-50 millisecond round-trip latency. Terrestrial networks typically achieve 10-20 millisecond latency. However, for AI applications, computation time often dominates total response time, making slightly higher latency acceptable if other benefits (power efficiency, cost) are substantial. For real-time interactive applications, the latency difference might be problematic. For batch processing, model inference, and non-latency-critical workloads, orbital infrastructure could be acceptable.

What is the realistic timeline for orbital data center deployment?

Based on historical Space X timelines and regulatory processes, meaningful orbital data center capability might emerge around 2029-2032. FCC approval would take approximately 1-3 years (possibly 2027-2028). Development and testing of prototype nodes would require 2-4 years. Manufacturing ramp-up to support significant deployment would take 3-5 years. Actual constellation deployment would be gradual, potentially starting with 10,000-50,000 satellites in initial operational phases, then expanding over subsequent years. The full million-satellite constellation, if ever deployed, might require 15-20 years of sustained effort. This timeline assumes no major setbacks—regulatory delays, technical challenges, or economic downturns could extend these estimates significantly.

Who are the competitors to Space X in orbital infrastructure?

Amazon's Project Kuiper is the closest competitor, deploying a constellation of roughly 3,200 satellites for broadband, though not currently designed for computing infrastructure. One Web, after emerging from bankruptcy, is rebuilding a smaller constellation. On the pure computing side, no other company is aggressively pursuing orbital data center deployment at scale. NASA and various research institutions have published conceptual studies, but nothing approaching commercial deployment. Amazon's Kuiper could potentially add compute capabilities, but the company has not announced such plans. The lack of competition suggests either that other companies don't believe the concept is viable, or that Space X's launch cost advantages and manufacturing expertise create insurmountable competitive barriers.

What are the environmental impacts of deploying a million satellites?

Environmental impacts are mixed and partially uncertain. Positively, orbital data centers would avoid terrestrial electricity generation, reducing coal, gas, and nuclear power consumption and associated emissions. This could provide climate benefits if orbital infrastructure displaces high-carbon terrestrial power sources. Negatively, manufacturing and launching a million satellites consumes substantial resources and energy. Additionally, deorbiting a million satellites means a million controlled reentries, releasing aluminum oxide particulates in the upper atmosphere at scales not well-studied. Light pollution from visible satellites would increase dramatically, hampering astronomical observations. The net environmental impact depends on the comparison baseline—versus fossil fuel-powered data centers, orbital infrastructure might be positive; versus renewable-powered terrestrial alternatives, it might be negative.

Conclusion: Space as the New Frontier for Computing Infrastructure

Space X's filing to deploy one million satellites as an orbital data center represents more than just an engineering proposal. It's a statement about where computing infrastructure might go in an era of artificial intelligence abundance.

The audacity is unmistakable. One million satellites. One hundred times larger than the current Starlink constellation. A project so ambitious that most people reflexively dismiss it as impossible. And yet, Space X has a track record of achieving things others said were impossible.

The core argument is compelling. AI computing demands are escalating exponentially. Terrestrial power grids are constrained. Data center costs are rising. Space-based infrastructure, powered by unlimited solar energy, offers a potential escape from these constraints. The economics might work if execution succeeds.

But there are genuine risks and challenges. The FCC might reject or drastically scale back the proposal. Orbital debris concerns could prove insurmountable. Manufacturing and deployment might encounter unforeseen bottlenecks. Technical performance might fall short of theoretical expectations. Any of these could derail the entire vision.

Most likely, we'll see something in between. Space X deploys 100,000-500,000 satellites providing meaningful orbital compute capacity. The FCC approves a scaled version. Competitors develop alternative approaches. Within a decade, orbital computing becomes one tool among many for infrastructure operators, used where advantages justify the complexity.

It's not a silver bullet that solves all computing challenges. But it's a genuinely innovative approach to a real problem. And if there's one thing we've learned about Space X, it's that ambitious visions have a way of becoming reality, just not always on the timeline originally imagined.

For the AI industry, for space entrepreneurs, for everyone interested in where technology is heading, Space X's filing deserves serious attention. The future of computing might quite literally be out of this world.

Key Takeaways

- SpaceX filed for FCC approval to deploy up to one million satellites as an orbital data center powered by solar energy to meet AI computing demands

- A million satellites would be roughly 100x larger than current Starlink constellation, dramatically increasing infrastructure but also collision and debris risks

- Solar power in orbit provides 7-13x greater power density than Earth's surface, offering fundamental cost advantages if engineering challenges are solved

- FCC historically scales back SpaceX proposals, so approved deployment will likely be smaller than one million, probably 100,000-500,000 satellites

- Realistic orbital data center deployment timeline spans 5-10 years from FCC approval through manufacturing ramp-up and orbital operations, not immediate

- Orbital infrastructure faces competition from terrestrial alternatives including renewable energy, nuclear power, geothermal sources, and AI model efficiency improvements

- A million operational satellites would require solving unprecedented challenges in space traffic management, debris mitigation, and manufacturing scale

Related Articles

- SpaceX and xAI Merger: What It Means for AI and Space [2025]

- Major Cybersecurity Threats & Digital Crime This Week [2025]

- Context-Aware Agents & Open Protocols in Enterprise AI [2025]

- Amazon's CSAM Crisis: What the AI Industry Isn't Telling You [2025]

- Why Publishers Are Blocking the Internet Archive From AI Scrapers [2025]

- Energy-Based Models: The Next Frontier in AI Beyond LLMs [2025]

![SpaceX's Million-Satellite Orbital Data Center: Reshaping AI Infrastructure [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/spacex-s-million-satellite-orbital-data-center-reshaping-ai-/image-1-1769882807539.png)