Supreme Court Case Could Strip FCC of Fine Authority: What's at Stake

The Supreme Court just agreed to hear a case that could fundamentally reshape how federal agencies regulate industries. AT&T and Verizon are challenging the FCC's authority to issue fines, arguing the commission violated their right to a jury trial when it penalized them for selling customer location data without consent. On the surface, it sounds like a narrow telecom dispute. But the implications are massive. If these carriers win, the FCC could lose one of its most powerful enforcement tools. And that's just the beginning.

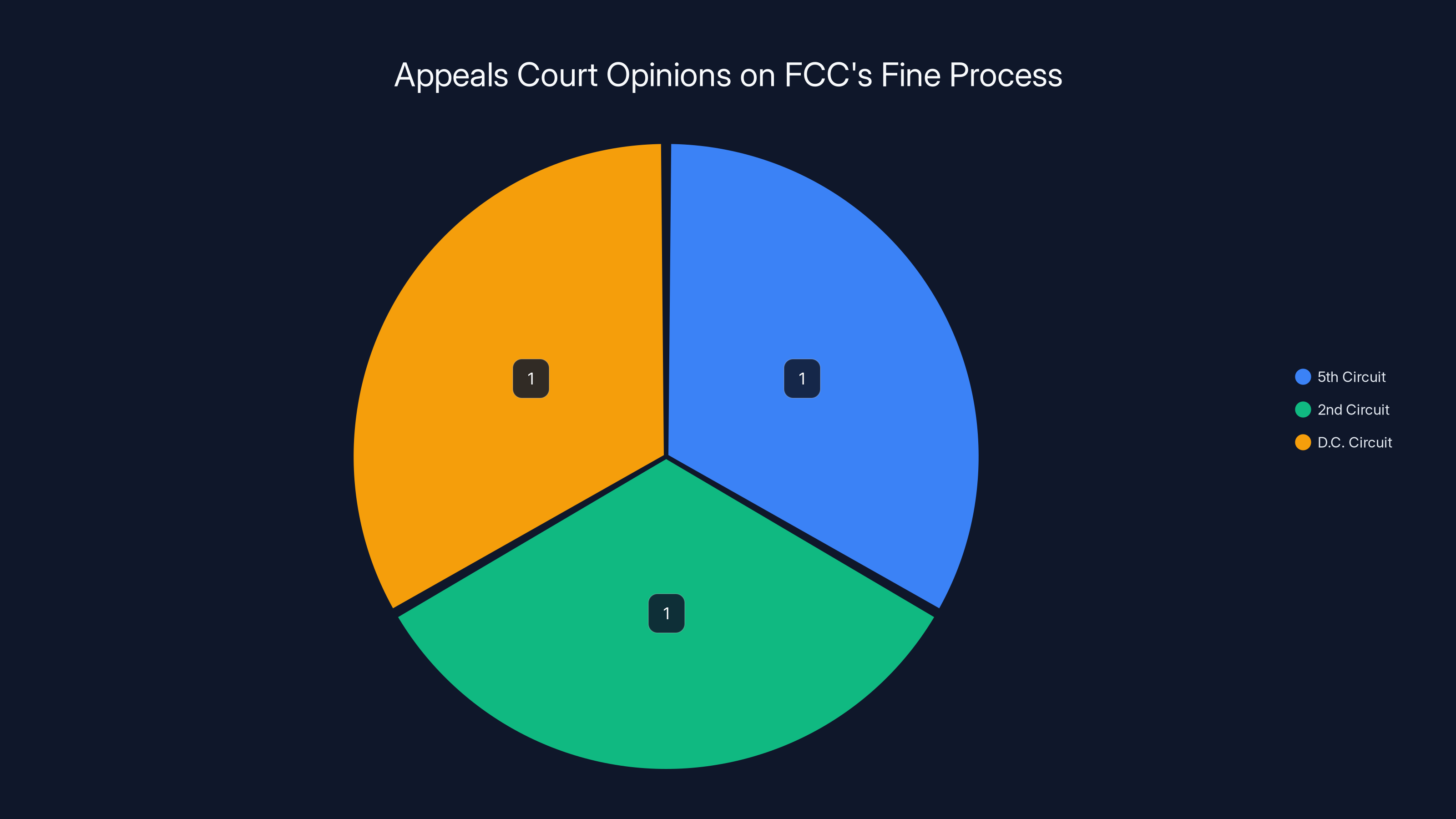

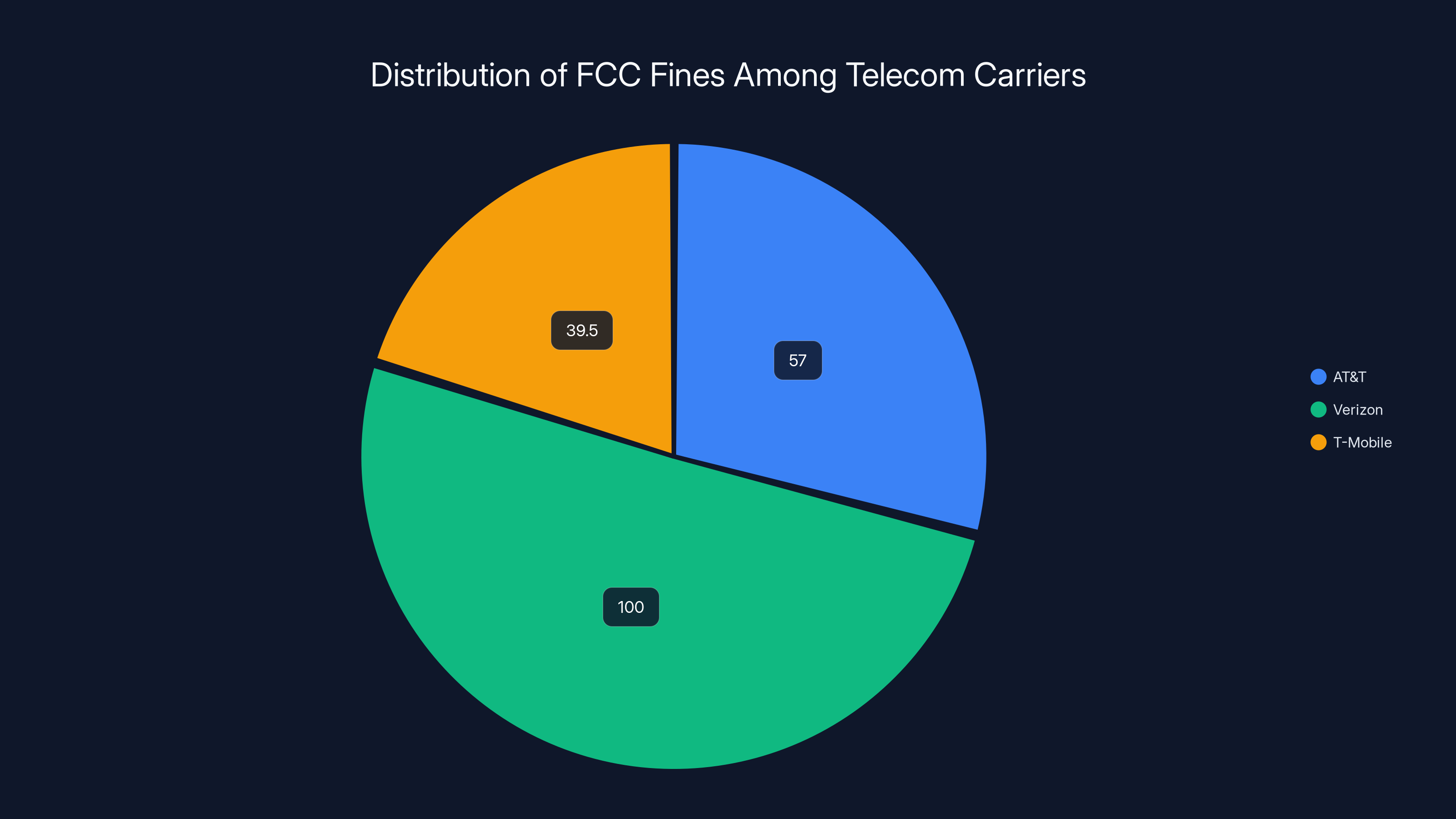

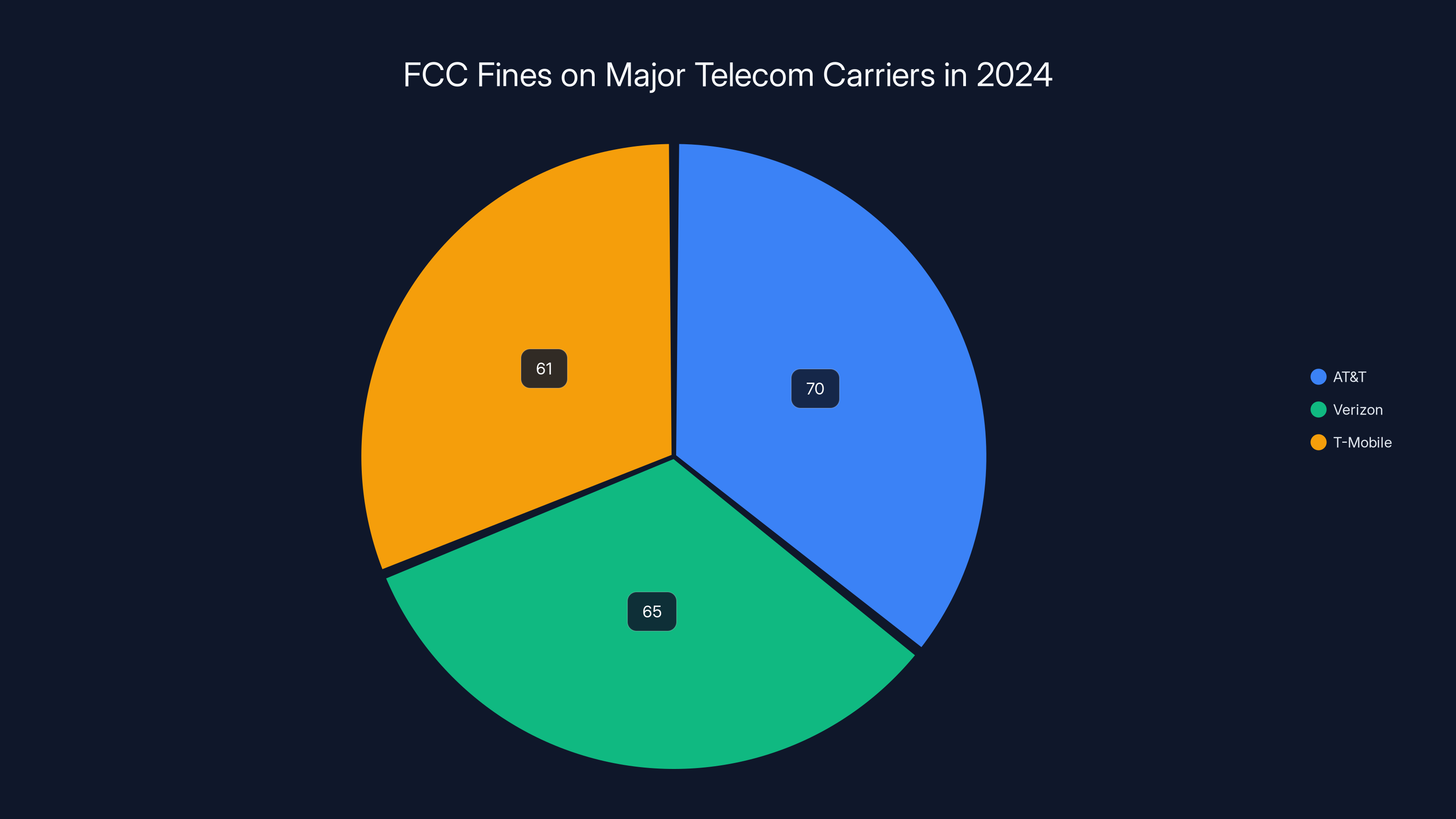

This case matters because it sits at the intersection of constitutional law, regulatory power, and corporate accountability. The FCC fined the big three carriers—AT&T, Verizon, and T-Mobile—a combined $196 million in 2024 for improperly sharing customers' location information. The companies argued they were never given the chance to defend themselves before a jury. The appeals courts split three ways. Now the Supreme Court is jumping in to settle it. This decision will affect not just telecom companies, but every regulated industry from utilities to banks to tech platforms.

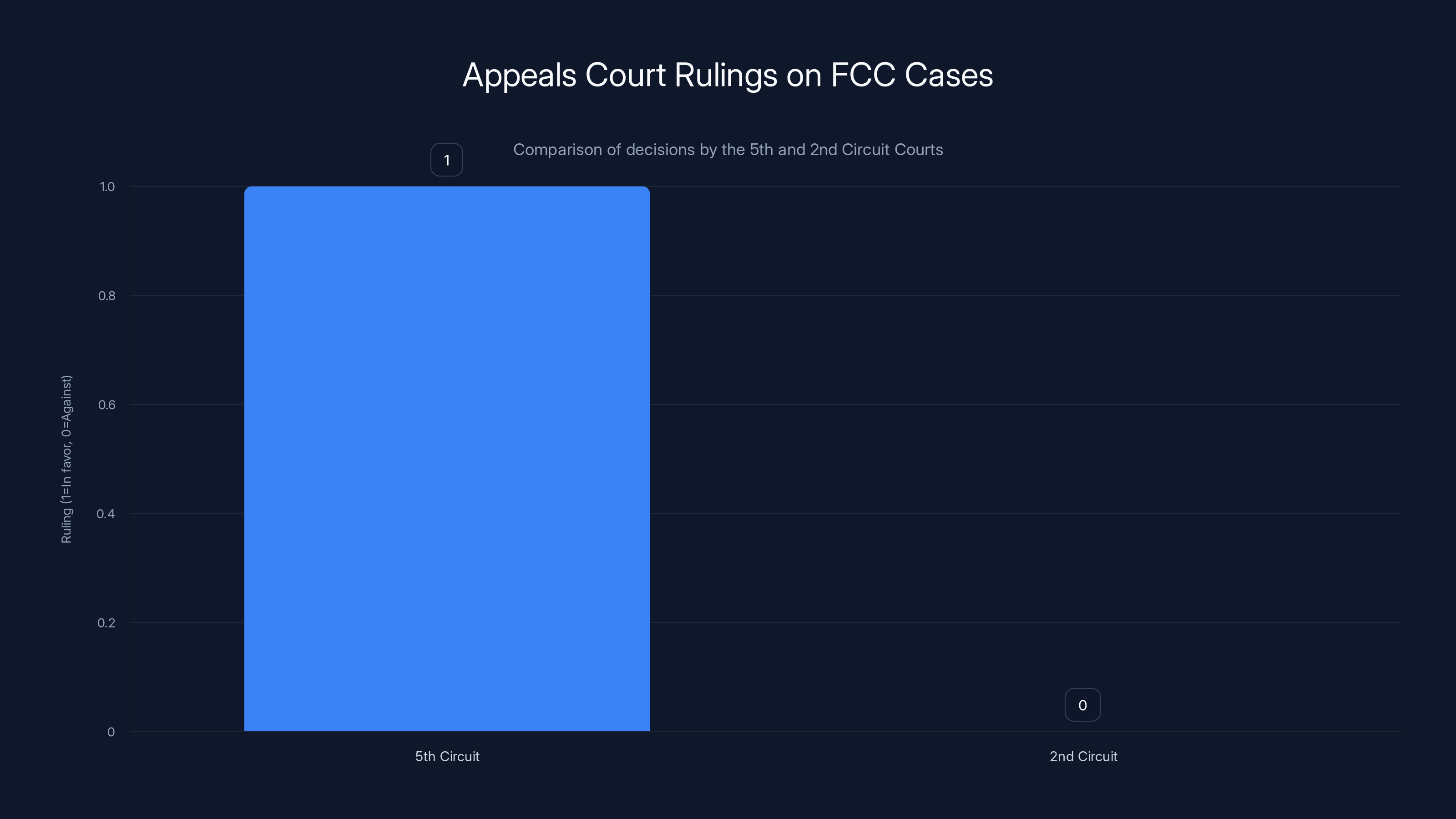

Here's what you need to understand: the case hinges on a Supreme Court precedent from June 2024 called SEC v. Jarkesy. That ruling said the Securities and Exchange Commission's process for issuing fines without guaranteeing a jury trial violated the Seventh Amendment. The telecom carriers are now saying the FCC's process has the same problem. The government and the FCC are defending their authority to issue fines before a jury trial happens. The conservative-leaning 5th Circuit agreed with AT&T. The 2nd Circuit and D. C. Circuit disagreed with Verizon and T-Mobile. The Supreme Court will finally settle the conflict.

What's particularly interesting is how the Trump administration is positioning itself. Even though Trump's FCC chairman Brendan Carr voted against the location data fines last year, the administration is defending the FCC's legal authority to issue them. That tells you this isn't about left versus right politics. It's about whether regulatory agencies can function effectively in the modern economy. Let's dig into what happened, why it matters, and what might come next.

The $196 Million FCC Fines Explained

Back in 2018, investigative journalists discovered something that should have shocked more people than it did. The big telecom carriers—AT&T, Verizon, and T-Mobile—had been selling access to customer location data to third parties. Not in some abstract way. Real-time tracking information about where customers were, where they were going, and where they'd been. The companies claimed they had location services people could opt into, but the problem was the data was leaking to brokers, bail bondsmen, and anyone else with $300 to spend on a location lookup service.

It took years for enforcement to happen. In 2024, the FCC finally issued fines totaling

But here's where things get complicated. The carriers didn't pay the fines and then appeal quietly. Instead, they fought back on a constitutional level. They argued the entire process violated their rights. In particular, they claimed the FCC acted as "prosecutor, jury, and judge" all at once. They had to pay the fine or potentially face legal consequences, but they never got a chance to present their case to an actual jury before the FCC decided they were guilty.

The 5th Circuit Court of Appeals (based in New Orleans) agreed with AT&T. Judge Jennifer Elrod wrote that the FCC's process violated the Seventh Amendment guarantee of a jury trial for civil cases involving money damages. She noted that the FCC issued the fine, collected it, and then AT&T had to appeal to try to get it back. That's backward from how jury trials normally work. Usually, you get your trial first, and the government collects money only if it wins in court, not before.

But the 2nd Circuit Court of Appeals (covering New York and the Northeast) saw it differently when Verizon appealed. The judges wrote that Verizon actually had a choice. The company could refuse to pay the FCC's fine and wait for the Department of Justice to sue in district court to collect it. In that lawsuit, Verizon could demand a jury trial. The problem with that logic, Verizon's lawyers pointed out, is that the DOJ might never sue. Verizon would then be stuck refusing to pay while suffering "serious practical and reputational harms" just to maybe get its day in court.

The D. C. Circuit sided with the 2nd Circuit when T-Mobile appealed. So now you had three different federal courts interpreting the same constitutional question three different ways. That's exactly why the Supreme Court exists. Someone has to settle these conflicts, and only the Supreme Court can do it across the whole country.

The 5th Circuit ruled in favor of AT&T, citing a violation of the Seventh Amendment, while the 2nd and D.C. Circuits sided with the government, suggesting jury trials could occur if the DOJ sues for fine collection.

The SEC v. Jarkesy Precedent Everyone's Talking About

The whole dispute comes down to a Supreme Court decision that's only eight months old. In June 2024, the Supreme Court ruled in SEC v. Jarkesy that the Securities and Exchange Commission violated the Seventh Amendment when it issued a $300,000 fine against an investment adviser named George Jarkesy without giving him a jury trial option.

Jarkesy had allegedly committed securities violations. The SEC issued an administrative order finding him liable and ordering him to pay. He appealed to the SEC's own internal tribunal, which upheld the finding. Then he could appeal to the federal courts, but only on a limited basis. He couldn't present new evidence or have a jury. The Supreme Court said that process was unconstitutional because the Seventh Amendment guarantees the right to a jury trial in civil cases where the government is seeking money damages.

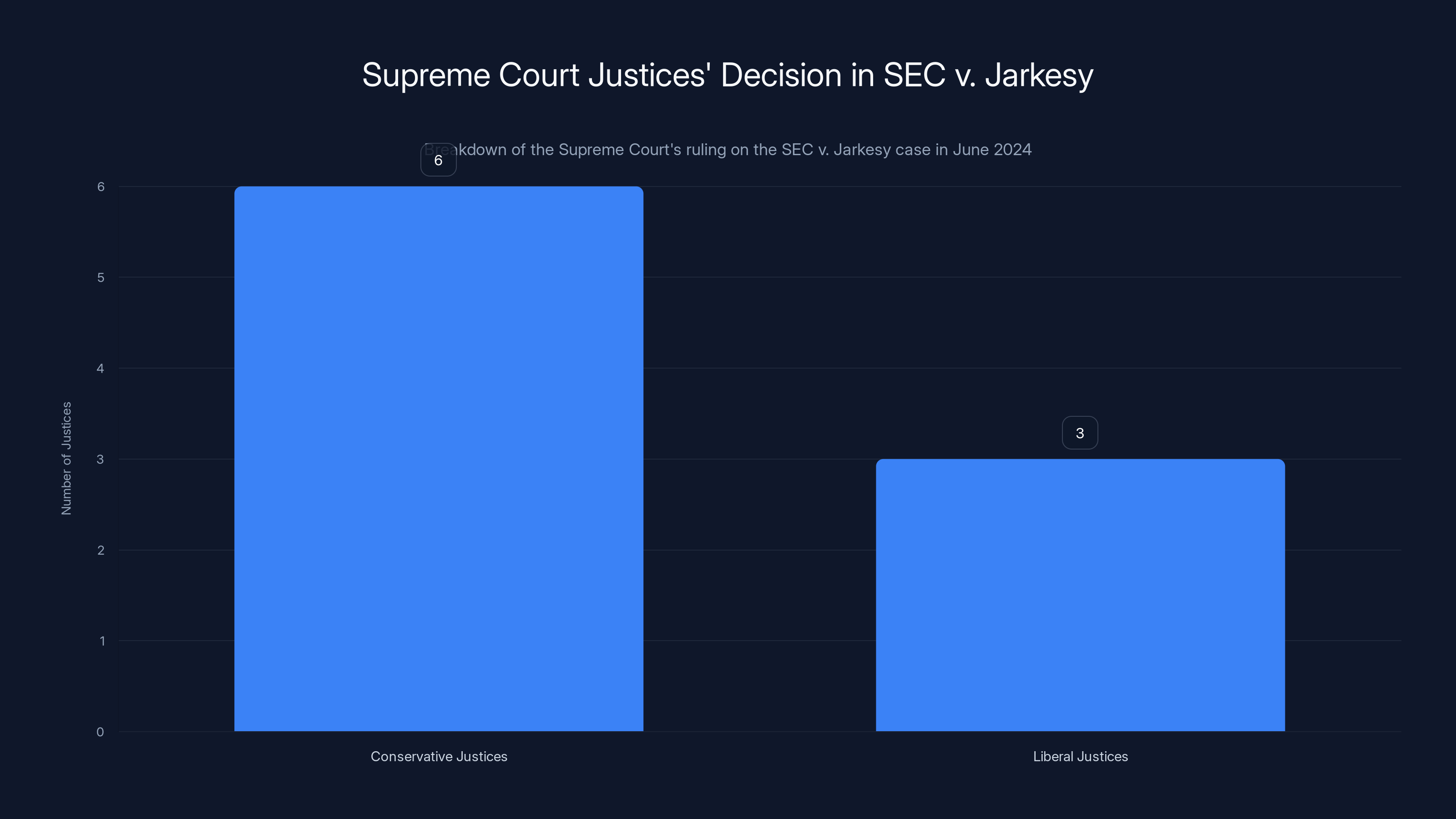

The conservative wing of the Court (Chief Justice Roberts, Justices Thomas, Alito, Gorsuch, Barrett, and Kavanaugh) decided that agency-issued fines without jury trial options violated that constitutional right. The liberal justices disagreed, arguing that agencies had been handling this way for a century, and Congress knew about it and hadn't changed the law. But the conservatives had the votes.

Telecom carriers immediately seized on Jarkesy. They said if the SEC can't issue fines without offering a jury trial, then neither can the FCC. Their lawyers filed appeals in all three circuits making essentially the same argument. And here's the key: the 5th Circuit actually agreed with them. Judge Elrod's opinion directly cited Jarkesy and said the FCC's process failed the constitutional test.

But the 2nd and D. C. Circuits distinguished their cases. They pointed out that securities law and telecom law are actually different in important ways. Under the Communications Act, there's a theoretical pathway to a jury trial if you refuse to pay the FCC's fine and force the DOJ to collect. Under securities law, that pathway didn't exist. You got your internal hearing at the SEC, and then you got limited appellate review, period. No jury trial option at any stage.

That's a genuine legal difference, and it's probably why the 2nd and D. C. Circuits went the way they did. But Verizon's legal team argued—and the 5th Circuit agreed—that a theoretical pathway to a jury trial that requires a company to refuse to pay and hope the DOJ files suit isn't a real pathway. It's a mirage.

Verizon received the largest fine of

How the Appeals Courts Split Three Ways

When three federal appeals courts reach three different conclusions about the same legal question, that's a red flag the Supreme Court can't ignore. Let's walk through what each court decided and why.

The 5th Circuit, which covers Texas and the South, ruled in AT&T's favor. This court leans conservative and has been skeptical of agency power in recent years. Judge Elrod's majority opinion was blunt. The FCC, she wrote, was acting as "prosecutor, jury, and judge." The agency investigated AT&T, charged AT&T, held a hearing where AT&T presented its case, and then issued a fine all on its own. Only after all that could AT&T appeal to a federal court for review, and even then, that review would be limited. The court would defer to the FCC's factual findings and only check whether the agency had any reasonable basis for its decision.

Elrod concluded this process violated the Seventh Amendment. She relied heavily on Jarkesy and noted that the Supreme Court had already said agency processes that don't guarantee jury trials for money damages are unconstitutional. The 5th Circuit vacated AT&T's fine and sent the case back to the FCC.

The 2nd Circuit Court of Appeals, which covers New York, Connecticut, and Vermont, took a completely different approach. The judges acknowledged the problem but said Verizon had a solution available: refuse to pay. If Verizon refused to pay the FCC's fine, the Department of Justice would likely sue in district court to collect it. In a district court lawsuit, Verizon could demand a jury trial. The company would then get to present its full case to a jury.

The 2nd Circuit's opinion quoted its own precedent from 1999 in a case called Bechtel v. United States. In that case, the court said that administrative agencies can issue orders requiring payment, and those orders become final if not appealed. But if the government wants to actually collect on a judgment that's been appealed and lost in court, it has to sue in district court where the Constitution applies fully. And in that district court lawsuit, the defendant gets a jury trial.

So according to the 2nd Circuit's logic, Verizon did have a jury trial right. It just had to take the lumps first by refusing to pay and then waiting for the DOJ to sue. The court acknowledged this might be annoying, but it wasn't unconstitutional. The judges wrote: "Verizon could have gotten such a trial if it had declined to pay the forfeiture and preserved its opportunity for a de novo jury trial if the government sought to collect." Instead, Verizon chose to pay and appeal, which waived its jury trial right.

The D. C. Circuit, which covers Washington D. C. and handles many regulatory appeals, sided with the 2nd Circuit on the same logic. T-Mobile could theoretically get a jury trial by refusing to pay. The judges applied the Administrative Procedure Act's standards for judicial review and concluded the FCC's process passed muster. T-Mobile lost its appeal.

So now you had the 5th Circuit saying: jury trial right violated, the carriers win. And you had the 2nd and D. C. Circuits saying: jury trial right is available if you refuse to pay, the government wins. The Supreme Court couldn't let this stand. It granted cert in both cases—Verizon's petition and the FCC's petition in the AT&T case—and consolidated them.

The Seventh Amendment Right to Jury Trial Explained

Most people think the right to a jury trial is straightforward. You get accused of something, you get a trial in front of a jury of your peers, and the jury decides if you're guilty. But constitutional law is rarely that simple, especially when administrative agencies are involved.

The Seventh Amendment says: "In Suits at common law, where the value in controversy shall exceed twenty dollars, the right of trial by jury shall be preserved." That language dates to 1791, and courts have been arguing about what it means ever since. Does it apply to administrative agencies? Only if they're ordering specific sums of money from people. Or can Congress just decide to skip the jury trial when regulation is involved?

For most of American history, federal agencies could issue orders imposing penalties without any jury trial involvement. The Interstate Commerce Commission could fine railroads. The Federal Trade Commission could fine companies for unfair practices. The Environmental Protection Agency could fine polluters. Congress designed these agencies precisely because they could operate faster and cheaper than courts. You didn't want to drag every regulatory case before a jury.

But the Supreme Court's 2024 Jarkesy decision changed that analysis. The Court said that if an administrative agency is issuing a final order requiring a company to pay money, and that case arose from a dispute about money damages rather than purely regulatory standards, then the Seventh Amendment applies. The company gets a jury trial right.

That sounds simple until you start asking questions. What counts as a "suit at common law"? Is a regulatory fine a suit at common law? What about penalties that are partly compensatory and partly punitive? The Supreme Court in Jarkesy tried to set some boundaries, but the boundaries are blurry.

For the FCC case, the question is whether a fine for violating communications law is the kind of claim where you traditionally had jury trials at common law. Historically, juries decided disputes over money between private parties. They decided whether one merchant owed money to another. They decided contract disputes. But did they decide regulatory violations? That's trickier. Regulatory law is relatively new. Most of it didn't exist in 1791 when the Seventh Amendment was written.

The FCC's argument is that telecom regulation is entirely statutory. Congress created the FCC, Congress gave it authority to regulate communications, and Congress authorized it to impose fines for violations. There's no common law equivalent to "failing to properly safeguard customer location data." This is purely a creature of statute. Therefore, the Seventh Amendment doesn't apply. The FCC can issue fines the same way other agencies always have.

But the carriers' argument is that underneath the regulatory language, there's still a claim for money. The FCC is saying: you wrongfully harmed customers, and now you have to pay us money to compensate. That sounds like a traditional damages claim to a jury, even if it's dressed up in regulatory language. If it walks like a damages claim and quacks like a damages claim, it gets a jury trial, regardless of what the agency calls it.

The Supreme Court's Jarkesy decision leaned toward the carriers' interpretation. Chief Justice Roberts wrote that even though securities violations are creatures of statute, the underlying claim—pay money because you did something wrong—is the kind of claim that would have been tried to a jury at common law. Therefore, a jury trial right applies.

In 2024, the FCC fined AT&T, Verizon, and T-Mobile a total of $196 million for sharing customer location data without consent. The distribution shows AT&T received the largest fine.

The Government's Defense of FCC Authority

The Trump administration's Justice Department filed a brief defending the FCC's authority to issue fines without first guaranteeing a jury trial. Interestingly, this wasn't a party-line issue. The FCC itself also defended the fines, even though Trump's FCC chairman Brendan Carr had voted against them last year. The government's brief made several key arguments.

First, the Justice Department argued that Supreme Court precedent going back to 1899 allows agencies to issue initial decisions finding people liable for money damages, with a jury trial available only later on appeal. The government cited United States v. Bitty (1899), which upheld a similar scheme where an executive agency could issue initial decisions, subject to later review by a jury in an Article III court. The government also cited United States v. Grimaud (1911) and another case from 1915 upholding similar processes.

The Justice Department brief stated: "A 1915 Supreme Court ruling upheld a similar scheme under which an executive agency could issue initial decisions finding regulated parties liable for money damages, subject to review by a jury in an Article III court." That's the core argument. These processes aren't new. They've been around for over a century. The Supreme Court has already approved them. Unless the Supreme Court explicitly overrules those old cases, the FCC's process should be constitutional.

Second, the government argued that the 5th Circuit's ruling would have serious practical consequences. The brief said the ruling "deprives the Commission of one of its most important regulatory remedies and severely impairs the agency's ability to enforce federal communications law." In other words, if every FCC fine has to be tried before a jury, the whole enforcement system breaks down. Cases move slower, juries are unpredictable, and companies can afford better lawyers to fight in jury trials than in administrative proceedings. The FCC might as well throw away its enforcement authority.

Third, the government distinguished telecom law from securities law. In the SEC case, the government conceded that the SEC's process was flawed and didn't provide a real jury trial pathway. But the Communications Act is different. A company can refuse to pay an FCC fine and force the DOJ to sue in district court for collection. In that lawsuit, the company gets a full jury trial. It's not ideal—you have to refuse to pay first—but it's a real option.

The government also made a practical point. The FCC's fining authority has existed for decades under the Communications Act. Congress knew the FCC could issue fines without a jury trial, and Congress kept the statute that way. If Congress thought this violated the Constitution, Congress had plenty of opportunity to fix it. The fact that Congress never changed the law suggests Congress didn't think there was a problem.

FCC Chairman Brendan Carr has been public about disagreeing with the location data fines on policy grounds. He thought the Biden-era FCC overreached in its interpretation of privacy regulations. But that's different from saying the FCC lacks legal authority to issue fines at all. The government's brief doesn't back down from the FCC's authority. It just argues the current process, while not perfect, is constitutional because there's a theoretical jury trial pathway if a company refuses to pay.

Why AT&T Won in the 5th Circuit

Judge Jennifer Elrod's majority opinion in AT&T's case at the 5th Circuit was particularly sharp in its critique of the FCC's process. She focused on what she called the agency's triple role: investigator, prosecutor, and judge all in one institution.

Here's how the actual FCC process works. The FCC's Enforcement Bureau investigates potential violations. If it finds evidence of wrongdoing, it issues a Notice of Apparent Liability. The company gets a chance to file a response and present arguments. After reviewing the response, the FCC issues a Forfeiture Order that imposes a fine. The company can appeal to the FCC itself, asking it to reconsider. If that fails, the company can appeal to federal court.

Judge Elrod called this process fundamentally backward. "The FCC, which investigated the violation, prosecuted the violation, and then adjudicated the violation, imposed the penalty first and allowed judicial review afterward," she wrote. She pointed to the Jarkesy case for support. The Supreme Court in Jarkesy said that when a government agency is imposing a significant penalty for wrongdoing, the target of that penalty needs some procedural protection. A jury trial is one form of that protection.

Elrod noted that in the AT&T case specifically, the FCC never gave AT&T a chance to present its case to a neutral decision-maker before the fine was imposed. Yes, AT&T could file a response to the Notice of Apparent Liability. But the FCC reviewed that response itself, as the same institution that had already decided AT&T violated the law. There's no independence there.

Furthermore, Elrod was skeptical of the "refuse to pay and hope the DOJ sues" argument. She noted that AT&T would suffer significant reputational harm in the interim. The FCC order would be public. AT&T would be known as a company that violated FCC rules and refused to pay the fine. That might be enough to pressure AT&T into paying even if it wanted to fight the penalty. A company doesn't want its name in headlines as a defiant scofflaw.

Judge Elrod also looked at the standard of review AT&T would get if it appealed the FCC's fine to federal court. The appeals court wouldn't hear the case fresh. It would review the FCC's decision under the Administrative Procedure Act's "arbitrary and capricious" standard. That's a very deferential standard that usually favors the agency. An appeals court will typically uphold an agency decision if it had any rational basis for making it.

Compare that to a jury trial. In a jury trial, AT&T could present its entire case from scratch. A jury would hear evidence from both sides and decide who was more credible. A jury wouldn't defer to the FCC. A jury might even vote to acquit even if the FCC had presented evidence of wrongdoing. Juries are unpredictable that way. They're supposed to be.

For all these reasons, Judge Elrod concluded the FCC's process violated the Seventh Amendment. The fine was vacated, and the case was sent back to the FCC. The FCC would have to either drop the fine or pursue it through a different process—presumably one that included a jury trial opportunity.

The Supreme Court's decision in SEC v. Jarkesy was split along ideological lines, with 6 conservative justices ruling against the SEC's process and 3 liberal justices dissenting.

Why the 2nd and D. C. Circuits Disagreed

The judges in the 2nd Circuit took a different approach to the jury trial question. They acknowledged the problem the 5th Circuit identified but said the solution was available to the carriers. The carriers just didn't like the solution.

The key distinction in the 2nd Circuit's opinion was about when the jury trial right had to be available. The judges wrote that the Constitution doesn't require a jury trial at the initial administrative stage. The government can issue an administrative order. But if the government wants to enforce that order in court, then the Constitution kicks in and requires a jury trial option.

This is actually a longstanding principle in administrative law. Administrative agencies can make initial determinations about money damages. But if the company refuses to pay and the government has to sue in federal court to collect, then the company gets a full jury trial in that court proceeding.

The 2nd Circuit applied this principle to the FCC case. The FCC issued its fine administratively. But if Verizon refuses to pay, the DOJ has to sue in district court for collection. In that district court lawsuit, Verizon gets a jury trial. The company can present its entire case to a jury. The jury can decide whether the FCC's fine was justified.

Did the judges acknowledge this isn't ideal? Actually, yes. The opinion recognized that Verizon would face reputational harm while refusing to pay and waiting for the DOJ to sue. But the judges said that's the price of exercising your jury trial right. You can't demand a jury trial while also getting to pay the fine and appeal quickly. You have to pick one.

The 2nd Circuit relied on the APA's standards for judicial review of agency decisions. Under the APA, when you appeal an agency decision to federal court, the court reviews the agency's action for abuse of discretion. The court defers to the agency's reasonable interpretations of law and clear factual findings. But if a jury is involved, there's no deference. The jury makes its own judgment.

The judges also noted that Congress knew how the FCC's fining process worked when it passed the Communications Act. Congress authorized the FCC to issue forfeiture orders (which is what the fines are called). Congress knew the FCC didn't hold jury trials administratively. If Congress thought that violated the Constitution, Congress could have required the FCC to hold jury trials. Congress didn't do that, which suggests Congress thought the process was okay.

The D. C. Circuit adopted similar reasoning in the T-Mobile case. The judges there emphasized that the Communications Act has been around for decades and the FCC's fining authority has been around just as long. Changing it now based on the Jarkesy decision would require the Supreme Court to explicitly overrule the older precedents the government cited.

Impact on Federal Regulatory Authority

This case matters far beyond telecom. If the Supreme Court sides with AT&T and Verizon, it would affect how dozens of federal agencies can enforce the law. The EPA, the FTC, the FDA, the SEC, the Labor Department, the EEOC—all of these agencies rely on the ability to issue fines without first holding jury trials.

Consider the EPA. The EPA sets environmental standards and fines companies that violate them. If every EPA fine required a jury trial, the enforcement system would slow dramatically. Companies could tie up EPA fines in jury trials for years. The litigation would be expensive. The EPA's enforcement authority would effectively be weakened.

The FTC fights fraud and unfair business practices. The agency issues cease-and-desist orders and fines companies for violating them. A jury trial requirement would complicate the process. Companies would demand juries in hopes of getting sympathetic jurors who might not fully understand the regulatory issues.

The SEC enforces securities laws. After the Jarkesy decision, the SEC already had to modify its process to offer jury trials. But if the Supreme Court goes further and says jury trials are required for all regulatory fines, the SEC would face even more constraints.

The labor agencies enforce wage laws and workplace safety rules. They issue citations and civil penalties. If jury trials become required, the enforcement system would be overwhelmed.

On the flip side, some argue that's actually a good thing. Maybe federal agencies have too much power. Maybe requiring jury trials would force agencies to be more careful about which cases to pursue and more honest about the evidence. Juries are more skeptical than judges. Juries might push back against aggressive enforcement.

There's a real constitutional tension here. On one hand, the Seventh Amendment says people have a right to jury trials in civil cases involving money damages. On the other hand, Congress has created agencies that need to function efficiently without going through jury trials for everything. The Supreme Court has to find a balance.

The Court's decision could go several ways. It could side with the carriers and say jury trials are always required for significant fines. It could side with the government and say the current system is constitutional because jury trials are available on appeal if you refuse to pay. Or it could split the baby and say jury trials are required for some kinds of fines but not others, depending on how they're characterized.

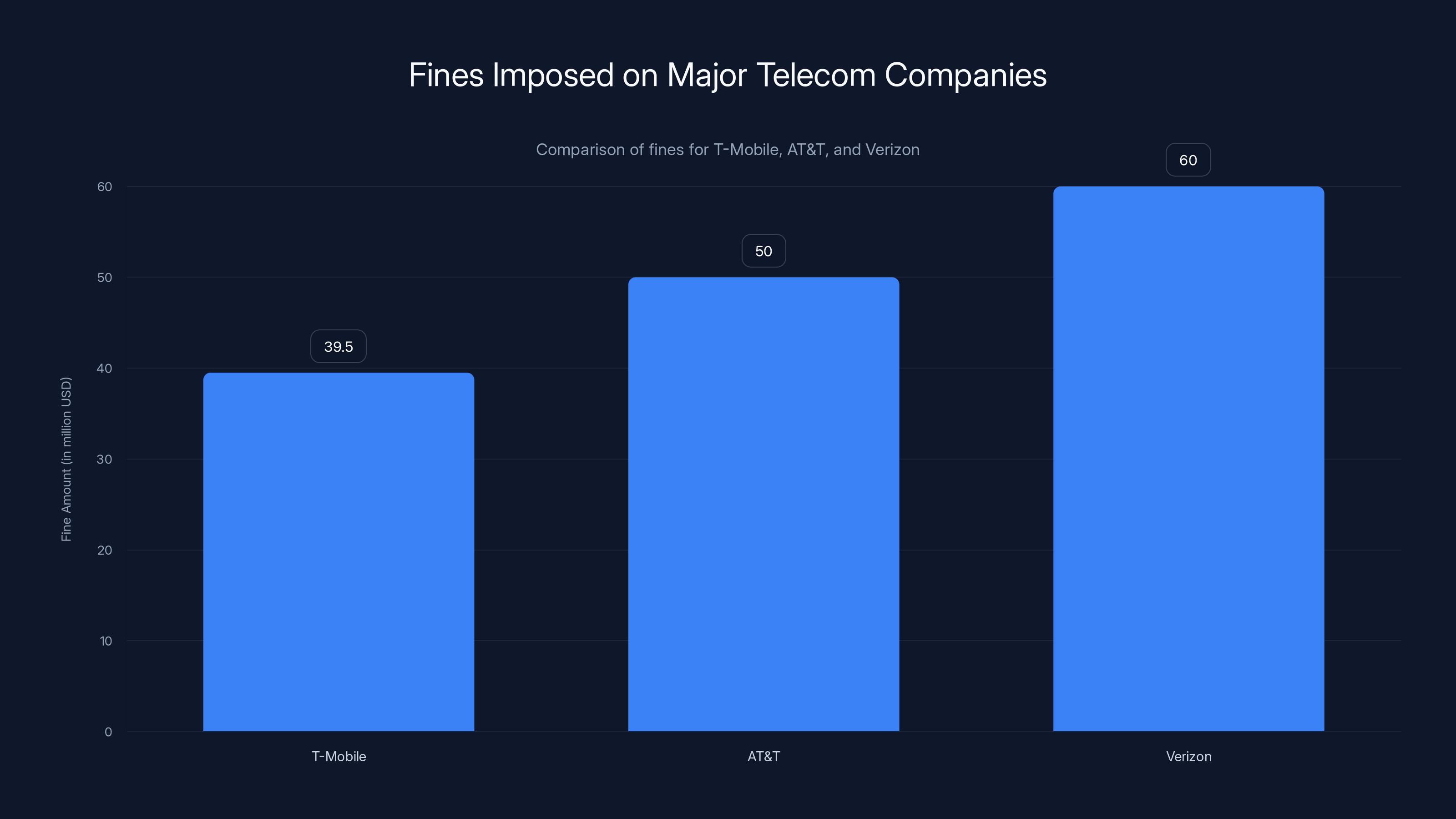

T-Mobile was fined $39.5 million, the smallest among the three major telecom companies, with AT&T and Verizon facing larger fines. Estimated data for AT&T and Verizon.

The Location Data Scandal That Sparked It All

It's worth understanding the actual facts that led to these fines because they matter for the Court's analysis. This isn't about some technical regulatory violation. This is about the telecom carriers selling access to real-time tracking data about customers' locations.

In 2018, investigative journalists, including those from Senator Ron Wyden's office, discovered that location data brokers could sell access to cellular location information. The companies providing this data were the big carriers themselves or companies they worked with. A location data broker could sell information about where someone was to bail bondsmen, debt collectors, auto repo companies, or anyone else with a few hundred dollars to spend.

The implications are serious. Your cell phone's location data is incredibly sensitive. It reveals where you live, work, worship, what political meetings you attend, what health clinics you visit. If that information is sold to the wrong people, it enables stalking, harassment, blackmail, and worse. The fact that this was happening without explicit customer consent was a serious privacy violation.

The carriers claimed they had location services that customers could opt into, and those services came with consent screens. But the data being sold to third parties wasn't limited to customers who had opted into specific services. It was much broader than that. And the consent mechanisms were either unclear or non-existent for much of the data.

The FCC finally acted in 2024, nearly six years after the initial revelations. By then, the carriers had presumably changed their practices somewhat, but the damage was done and so were the fines. The question is whether the FCC had the authority to impose those fines without holding jury trials.

Here's the interesting part: both sides of the constitutional dispute agree the carriers did something wrong. They agree the FCC had authority to regulate the carriers' practices. They even agree the FCC could issue some kind of fine or penalty. The only question is the procedure. Did the FCC have to give the carriers a jury trial before imposing the fine, or could it impose the fine first and let the carriers appeal?

It's a genuinely difficult constitutional question. It's not about whether location data brokers should be regulated. It's about how the government should regulate them.

What Oral Arguments Might Focus On

When the Supreme Court hears oral arguments in this case, the justices will probably focus on several specific questions. First, they'll want to know what counts as a "suit at common law" under the Seventh Amendment. Is a regulatory fine a suit at common law? What about a penalty that's partly compensatory and partly punitive?

Second, they'll want to explore the jury trial pathway the government says is available. How real is it? If a company has to refuse to pay and suffer reputational harm and then hope the DOJ sues, is that really a meaningful jury trial right? Or is it a theoretical right that companies can't practically exercise?

Third, the justices will probably ask about precedent. The government cites cases from 1899, 1911, and 1915 upholding agency fining authority without jury trials. Do those cases apply, or did Jarkesy implicitly overrule them? The conservative justices who voted for Jarkesy will face questions about whether they meant to go even further and require jury trials for regulatory fines.

Fourth, the Court will probably ask about practical consequences. If jury trials are required for all significant regulatory fines, how will agencies function? Will enforcement effectively collapse? Or will agencies adapt and work more carefully with juries the way they work with judges?

Fifth, the justices might ask about the specific Communications Act language. Does the Act's structure contemplate jury trials? Did Congress authorize jury trials? Or did Congress intend for the FCC to have complete authority to impose fines administratively?

The oral argument will be where the real fight happens. The written briefs set out the legal positions, but oral argument is where the justices ask the hard questions and the lawyers have to think on their feet. Justice Elena Kagan is known for asking sharp, probing questions about regulatory authority. Justice Clarence Thomas is skeptical of broad agency power. Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson will likely focus on practical consequences and real-world impacts. The dynamic at oral argument will give us clues about which way the Court is leaning.

The 5th Circuit ruled against the FCC's process, favoring AT&T, while the 2nd Circuit suggested a different approach, allowing Verizon to refuse payment and seek a jury trial. Estimated data based on narrative.

T-Mobile's Unique Position

T-Mobile's situation is interesting because it's been somewhat overshadowed by the AT&T and Verizon cases, but the D. C. Circuit's ruling against T-Mobile means the company is currently waiting to see what happens. T-Mobile was fined $39.5 million, the smallest of the three fines but still significant. The company filed an appeal in the D. C. Circuit, which ruled against it on the same logic the 2nd Circuit used: you can get a jury trial if you refuse to pay and the DOJ sues.

T-Mobile then petitioned for a rehearing in the D. C. Circuit, a request that's still pending. The company is probably hoping the Supreme Court's decision will make that rehearing request moot or result in a ruling in T-Mobile's favor. If the Supreme Court sides with AT&T, T-Mobile wins its appeal and the fine is vacated. If the Supreme Court sides with the government, T-Mobile might get its rehearing request denied and have to accept the fine.

T-Mobile's case isn't formally before the Supreme Court yet, but the Court's decision will definitely affect it. That's another reason the Supreme Court wanted to consolidate and resolve this issue. There's too much regulatory uncertainty with three different court rulings and multiple carriers in limbo.

The Broader Implications for Tech Regulation

This case comes at a moment when tech regulation is heating up. Congress is considering bills to strengthen privacy protections. States are passing their own privacy laws. The FTC is cracking down on tech companies. Tech CEOs are testifying before Congress. In this environment, the question of how much authority agencies actually have to enforce rules is crucial.

If the Supreme Court sides with the carriers, it would weaken the FCC's hand in future privacy enforcement. The FCC might have to be more selective about which cases to pursue, knowing that all significant fines could be tied up in jury trials. That could mean fewer fines issued and more companies getting away with privacy violations.

Alternatively, if the FCC knows jury trials are coming, the agency might pursue more criminal cases through the Department of Justice instead of administrative fines. Criminal cases are different from the jury trial issue. Those definitely get jury trials, but the standard of proof is "beyond a reasonable doubt" instead of the lower "preponderance of the evidence" standard in civil cases. That might make prosecutions harder.

For tech companies and other regulated industries, the question is whether they want jury trials for regulatory fines. On one hand, juries might be more sympathetic to companies than judges are. Juries are made up of regular people who might understand business concerns. On the other hand, juries are unpredictable. They might side with consumers over corporations. They might not understand the technical arguments. Companies might prefer the current system where they get administrative hearings and then appeals to judges who understand regulatory issues.

The case also touches on a bigger question about separation of powers. The Constitution divides power between the executive, legislative, and judicial branches. Agencies are part of the executive branch, but they make rules (legislative function) and hold hearings (judicial function). The Jarkesy decision was part of a broader trend on the conservative Supreme Court to question whether agencies have too much power and whether constitutional protections apply more strictly to agency action.

For those who think agencies are too powerful, this case is an opportunity to put more constraints on agency enforcement. For those who think agencies need flexibility to regulate complex industries, this case is a threat. The Supreme Court's decision will reflect which view controls the current Court majority.

Trump Administration's Strategic Positioning

One last point worth noting: the Trump administration's Justice Department is defending the FCC's authority even though Trump's FCC chairman disagreed with how the authority was used. This tells you something important about how government institutions work. The executive branch has institutional interests that transcend any particular administration's policy views.

Chairman Carr opposed the location data fines because he disagreed with the Obama-era precedent that established the FCC's authority over carriers' privacy practices. He probably would have preferred to see the FCC's regulatory reach over privacy reduced. But that's a different question from whether the FCC has any authority to enforce rules through fines.

The Justice Department probably reasoned as follows: if we let the courts strip the FCC of its fining authority, then future administrations (including Democratic administrations) will have even less ability to regulate anything. The institutional power of the executive branch as a whole is weakened. Better to defend the FCC's authority across administrations, even if you disagree with how a previous administration used that authority.

This dynamic matters because it suggests the Supreme Court might be getting more pressure from institutional actors to preserve agency authority than you'd otherwise expect. The Justice Department is typically one of the most powerful forces before the Supreme Court because the government appears in so many cases. When the Justice Department makes a position, the Court pays attention.

At the same time, the six conservative justices have shown skepticism of broad agency power in recent decisions. The Court's decision to take this case suggests at least some justices think there might be a real constitutional problem with the FCC's fining process. If the Court were confident the process was clearly constitutional, it might not have taken the case at all.

What a Victory Would Mean for Each Side

If AT&T and Verizon win, they would get their fines vacated or significantly reduced. The FCC would have to figure out a new process for issuing fines that either guarantees jury trials or finds another way to penalize carriers. The agency would probably move toward criminal prosecution or civil litigation in federal court rather than administrative proceedings. The entire regulatory system would shift.

For other agencies, a loss would be serious. Every agency that issues fines would have to evaluate whether those fines are constitutional. Some agencies might be able to work with the new system. Others might effectively lose enforcement authority if jury trials become the default.

If the government wins, the FCC keeps its fining authority largely intact. The carriers have to accept their fines or refuse to pay and wait for the DOJ to sue. The status quo continues. Other agencies keep their current fining systems. Administrative law continues pretty much as it has for decades.

The Supreme Court could also split the difference. It could say jury trials are required for truly massive fines but not for smaller ones. Or it could say jury trials are required for consumer protection violations but not for purely technical regulatory breaches. Or it could say the FCC has to offer a jury trial option before issuing the fine, not just after the company appeals. There are various middle-ground positions.

Timeline and What Comes Next

The Supreme Court granted the petitions in January 2025, consolidating the AT&T and Verizon cases. Oral arguments will happen sometime this spring or early summer, most likely in May or June. The Supreme Court typically releases decisions by the end of its term in June.

Between now and oral arguments, both sides will file additional briefs. Other parties might file amicus curiae briefs (friend of the court briefs) arguing for one side or the other. The FTC, the EPA, and other agencies that rely on fining authority might file a joint brief with the Justice Department arguing that the government's position is correct.

Meanwhile, T-Mobile's case sits in the D. C. Circuit waiting for the Supreme Court decision. The same with any other regulatory cases involving fines that might be pending in lower courts. Everything is sort of in limbo.

Once the Supreme Court decides, the impact will be felt across the regulatory landscape. If the Court sides with the carriers, agencies will have to adapt enforcement strategies. If the Court sides with the government, the case law will continue largely as before. Either way, this decision will be cited and analyzed for decades.

Final Analysis: Why This Matters to You

You might be thinking: I'm not a telecom carrier, I'm not an investor in AT&T or Verizon, I don't work for the FCC. Why should I care about this case?

You should care because this case affects how the government can regulate industries you depend on. Your internet service provider is regulated by the FCC. Your bank is regulated by the Federal Reserve and the Comptroller of the Currency. Your workplace is governed by OSHA and the Labor Department. Your food is regulated by the FDA. Your environment is protected by the EPA. All of these agencies rely on fining authority to enforce the law. If that authority is weakened, enforcement becomes harder.

On the other hand, if agencies have too much power and use it abusively, that hurts consumers and businesses too. Unreasonable fines discourage innovation. Unfair enforcement process damages companies unfairly. So there's a legitimate balance to strike between agency power and constitutional protection.

This case is asking the Supreme Court to find that balance. It's a genuinely hard question with reasonable arguments on both sides. The outcome will shape the regulatory landscape for years to come. That's why the Supreme Court took the case and why the entire business world is watching closely.

FAQ

What is the Seventh Amendment right to a jury trial?

The Seventh Amendment to the U. S. Constitution guarantees the right to a jury trial in civil cases involving disputes over money. The amendment states: "In Suits at common law, where the value in controversy shall exceed twenty dollars, the right of trial by jury shall be preserved." This right traditionally applied to cases between private parties in court, but the question of whether it applies to regulatory penalties imposed by government agencies has been contested, especially after the SEC v. Jarkesy decision.

How did the FCC's fine process work for the location data violations?

The FCC's Enforcement Bureau investigated whether AT&T, Verizon, and T-Mobile improperly shared customer location data. After the investigation, the FCC issued a Notice of Apparent Liability, giving the carriers a chance to respond. The carriers submitted arguments but didn't get a jury trial at this stage. The FCC then issued a Forfeiture Order imposing the fine. The carriers could appeal to the FCC itself for reconsideration, and then appeal to federal court, but those appeals were limited reviews of the FCC's decision, not full jury trials.

Why do the three appeals courts have different opinions on this case?

The 5th Circuit ruled that the FCC's process violated the Seventh Amendment because it didn't guarantee a jury trial before imposing the fine. The 2nd and D. C. Circuits said the carriers could get jury trials by refusing to pay the fine and forcing the DOJ to sue in federal court for collection. That difference in how they viewed the availability of jury trials led to opposite outcomes—the 5th Circuit sided with AT&T, while the 2nd and D. C. Circuits sided with the government.

What was the SEC v. Jarkesy decision and how does it relate to this case?

In SEC v. Jarkesy (2024), the Supreme Court ruled that the SEC violated the Seventh Amendment when it issued a $300,000 fine against an investment adviser without offering him a jury trial. The Court said that for money damages claims that arose from disputes traditionally tried to juries at common law, the government must provide a jury trial right. The telecom carriers are now arguing that the same logic applies to the FCC's fines for location data violations.

How would an FCC loss affect other federal agencies' enforcement power?

If the Supreme Court rules against the FCC, other agencies that issue fines—including the EPA, FTC, FDA, SEC, and Labor Department—would face similar challenges. They might have to modify their processes to include jury trial options, which could slow enforcement, increase litigation costs, and potentially reduce their effectiveness. Alternatively, agencies might pursue more criminal prosecutions through the DOJ or find other enforcement methods that don't rely on administrative fines.

What are the practical consequences if companies can refuse to pay FCC fines and demand jury trials?

In theory, carriers could refuse to pay fines and wait for the DOJ to sue in federal court, at which point they'd get a jury trial. However, the practical consequences would be severe. The company would suffer reputational harm with a public FCC order against it. It would face uncertainty about whether the DOJ would actually file suit. It would have to pay legal fees defending the case while the fine remains unpaid. These practical barriers might discourage companies from actually exercising the jury trial right, even if it's theoretically available.

When will the Supreme Court decide this case?

The Supreme Court granted the petitions in January 2025 and consolidated the AT&T and Verizon cases. Oral arguments are expected in the spring or early summer of 2025, likely in May or June. The Court typically releases decisions by the end of its term in June, so a decision is expected by mid-2025.

Could the Supreme Court split the difference with a middle-ground ruling?

Yes, absolutely. The Supreme Court doesn't have to pick one side or the other completely. The Court could rule that jury trials are required for some types of fines but not others, depending on size, nature of the violation, or other factors. It could require jury trial options before the FCC issues the fine rather than after. It could carve out exceptions for certain regulatory violations. There are various compromise positions the Court might take.

Why is the Trump administration defending the FCC's authority when Trump's FCC chairman voted against the fines?

The Justice Department is defending the FCC's institutional authority to issue fines, which is separate from whether a particular administration agrees with how that authority is used. The DOJ's position is that even if Chairman Carr disagrees with the location data fines on policy grounds, the FCC still has legal authority to impose them. Defending agency authority across administrations protects the executive branch's regulatory power long-term.

What do the location data violations tell us about why the FCC issued these fines in the first place?

The carriers had been selling access to real-time customer location information to third parties, including bail bondsmen and debt collectors, often without explicit customer consent or meaningful opt-out options. Location data is extremely sensitive—it reveals where people live, work, worship, and what health facilities they visit. The FCC's position was that the carriers violated federal law by improperly sharing this data. The fines were meant to punish the violations and deter future similar conduct.

Key Takeaways

- The Supreme Court is hearing AT&T and Verizon's challenge to the FCC's authority to issue $196 million in fines for location data sales without first providing jury trials

- Three federal appeals courts split 1-2, with the 5th Circuit siding with carriers and the 2nd and D.C. Circuits siding with the government on jury trial rights

- The case hinges on the June 2024 SEC v. Jarkesy Supreme Court decision, which said regulatory agencies cannot impose significant penalties without guaranteeing jury trial options

- A ruling against the FCC could weaken enforcement across dozens of federal agencies including the EPA, FTC, FDA, and SEC that rely on fining authority

- The Trump administration is defending the FCC's fining authority despite Chairman Carr voting against these specific fines, emphasizing institutional executive branch power

Related Articles

- App Store Age Verification: The New Digital Battleground [2025]

- Porn Taxes & Age Verification Laws: The Constitutional Battle [2025]

- Porn Taxes and Age Verification Laws: The Constitutional Crisis [2025]

- Appeals Court Blocks Trump's Research Funding Cuts: What It Means [2025]

- Offshore Wind Developers Sue Trump: $25B Legal Showdown [2025]

- Trump's Offshore Wind Pause Faces Legal Challenge: Data Center Power Demand Crisis [2025]

![Supreme Court Case Could Strip FCC of Fine Authority [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/supreme-court-case-could-strip-fcc-of-fine-authority-2025/image-1-1768248451644.jpg)