The Contradiction Nobody's Talking About

Tesla just rolled out the red carpet for the Cybercab. Sleek design. No steering wheel. The future of transportation, they said. Meanwhile, buried in regulatory filings and accident reports, there's a number that tells a very different story: Tesla's Robotaxis are crashing four times more frequently than human drivers.

That's not an exaggeration. That's not activist scaremongering. That's data.

The company that promises fully autonomous vehicles is operating a fleet where every 1,000 miles of driving produces crashes at rates that would get any human driver's insurance cancelled. And here's the thing that makes it weird: both statements are true. The Cybercab is legitimately innovative. And the safety record is legitimately concerning.

This contradiction sits at the heart of autonomous vehicle development in 2025. We're watching a company simultaneously push the boundaries of what's possible while operating one of the most accident-prone fleets on the road. Understanding what's actually happening requires looking past the marketing announcements and into the uncomfortable details.

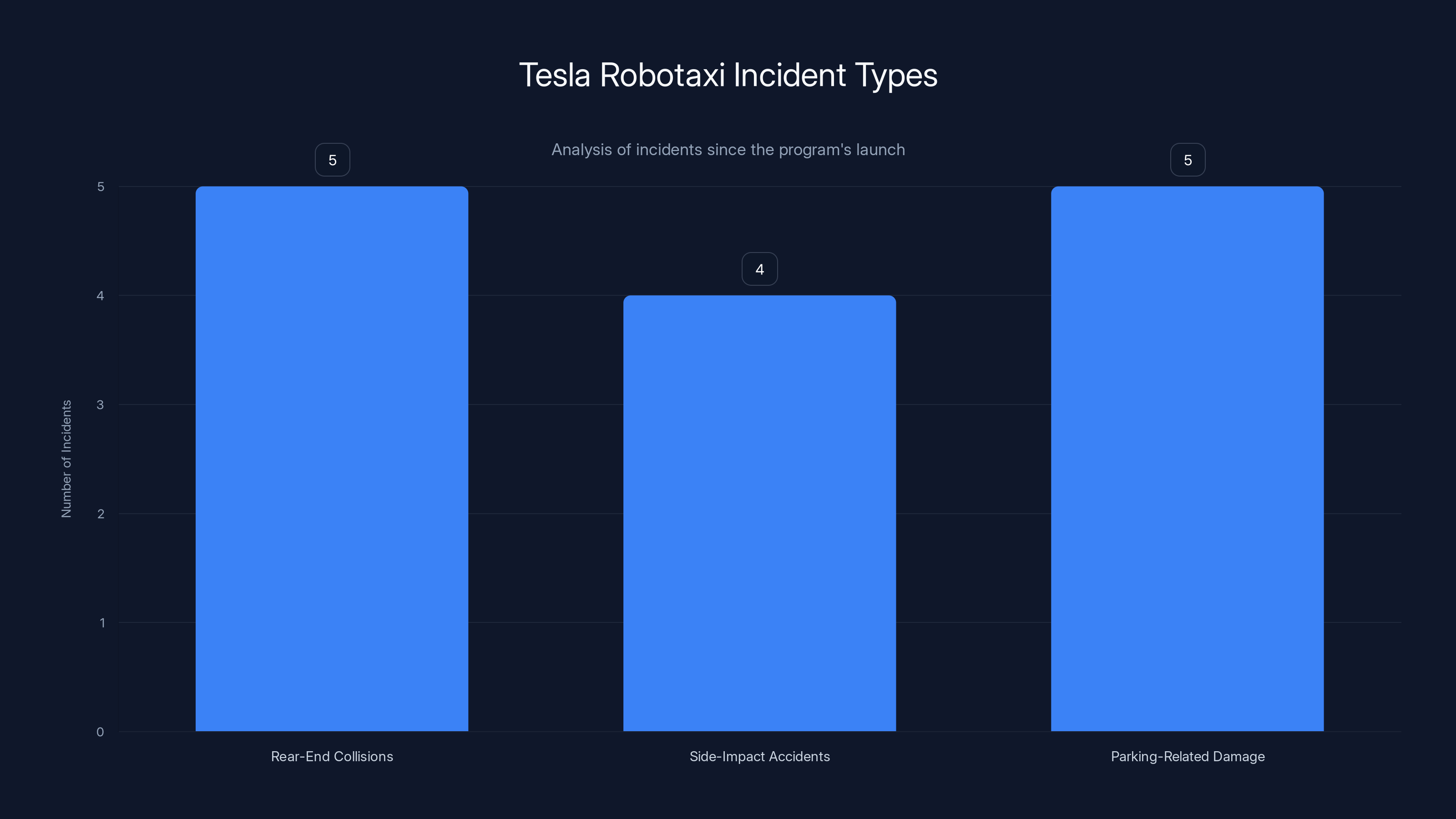

Let's start with what we know. Tesla's Robotaxi program has logged 14 incidents since its public launch. Some were minor fender-benders. Others involved property damage. None resulted in serious injuries, which is important context. But frequency matters. And Tesla's frequency is measurably worse than human drivers across comparable road conditions and mileage.

The gap between Tesla's public narrative and the safety data has created something unusual in tech: genuine, justified skepticism from safety regulators, insurance companies, and researchers who study autonomous systems professionally. They're not saying the technology is impossible. They're saying the execution so far doesn't match the confidence level.

Understanding Tesla's Robotaxi Program

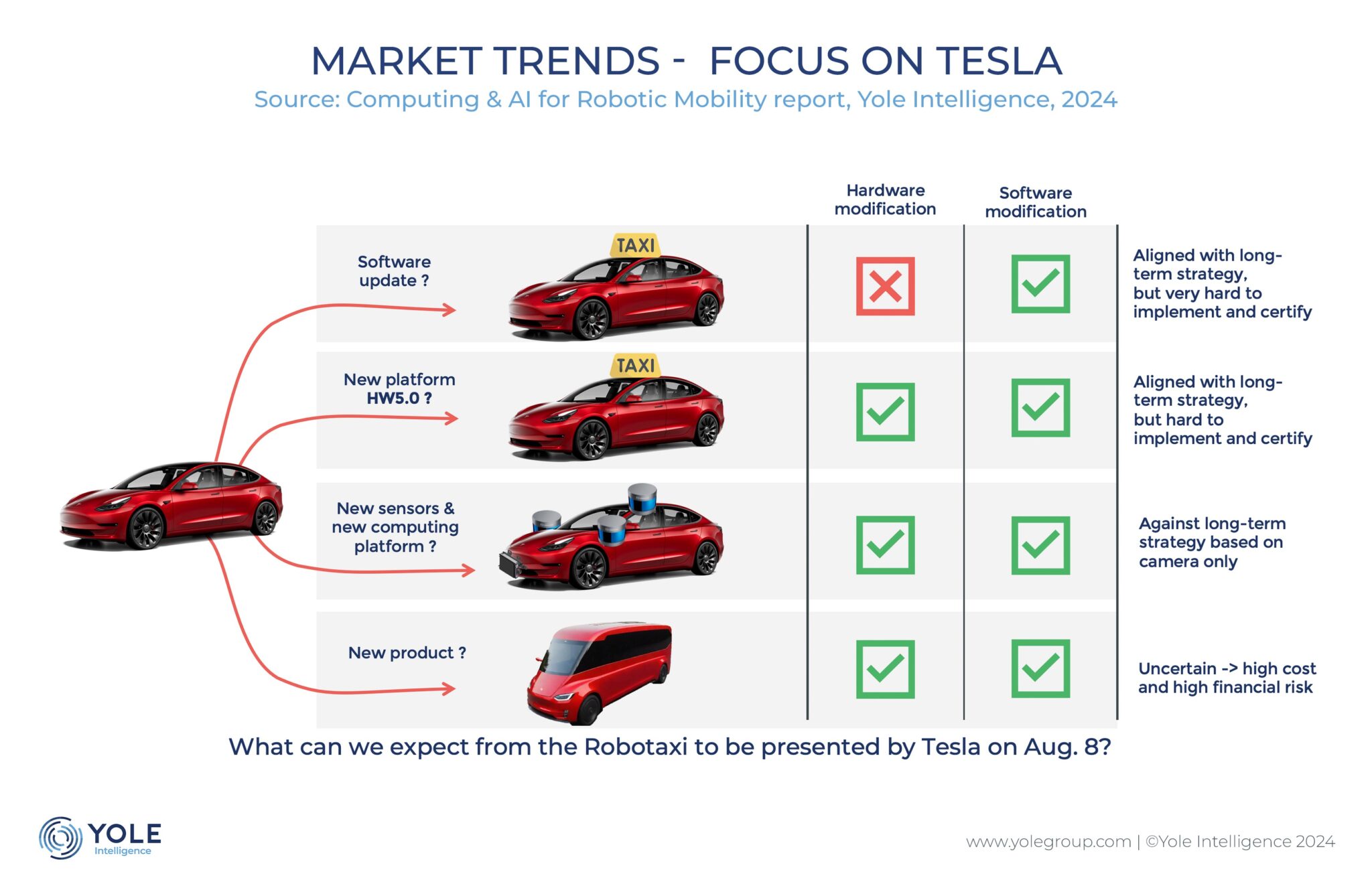

Before dissecting the numbers, you need the context. Tesla's Robotaxi service operates primarily in San Francisco and Phoenix, two cities with complex urban driving environments. The vehicles are modified Tesla vehicles equipped with the company's proprietary autonomous driving system, which relies heavily on camera-based vision and neural networks trained on Tesla's fleet data.

The Robotaxi differs fundamentally from traditional autonomous vehicles built by competitors. There's no LIDAR. No radar redundancy like you'll find in Waymo's systems. It's a camera-only approach that Tesla argues is sufficient because the neural networks have learned from millions of miles of real-world driving.

That training philosophy creates both advantages and problems. The advantage: the system sees the world the way human drivers do, through visual information. It's theoretically more intuitive to improve through machine learning because it mimics human perception. The problem: human perception has blind spots, and so does camera-only vision, especially in challenging conditions like heavy rain, glare, or nighttime driving.

Tesla launched the Robotaxi program with initial availability in limited markets. The service was framed as the next evolution of autonomous driving, moving beyond driver-assistance features into fully driverless operations. But "fully driverless" came with an asterisk: it still required human intervention in certain situations, and the actual autonomy level was closer to what regulators call Level 3 or 4, not the absolute autonomy the marketing suggested.

The 14 incidents logged since launch include rear-end collisions, side-impact accidents, and parking-related damage. None of these incidents were catastrophic. No pedestrians were hit. No high-speed collisions. But the frequency stood out to safety analysts because it emerged relatively quickly in the program's deployment.

Since its launch, Tesla's Robotaxi program has logged 14 incidents, primarily involving rear-end collisions and parking-related damage. Estimated data.

The Safety Data: What the Numbers Actually Show

Let's dig into the specific crash rates because this is where the story gets precise and harder to dismiss with spin.

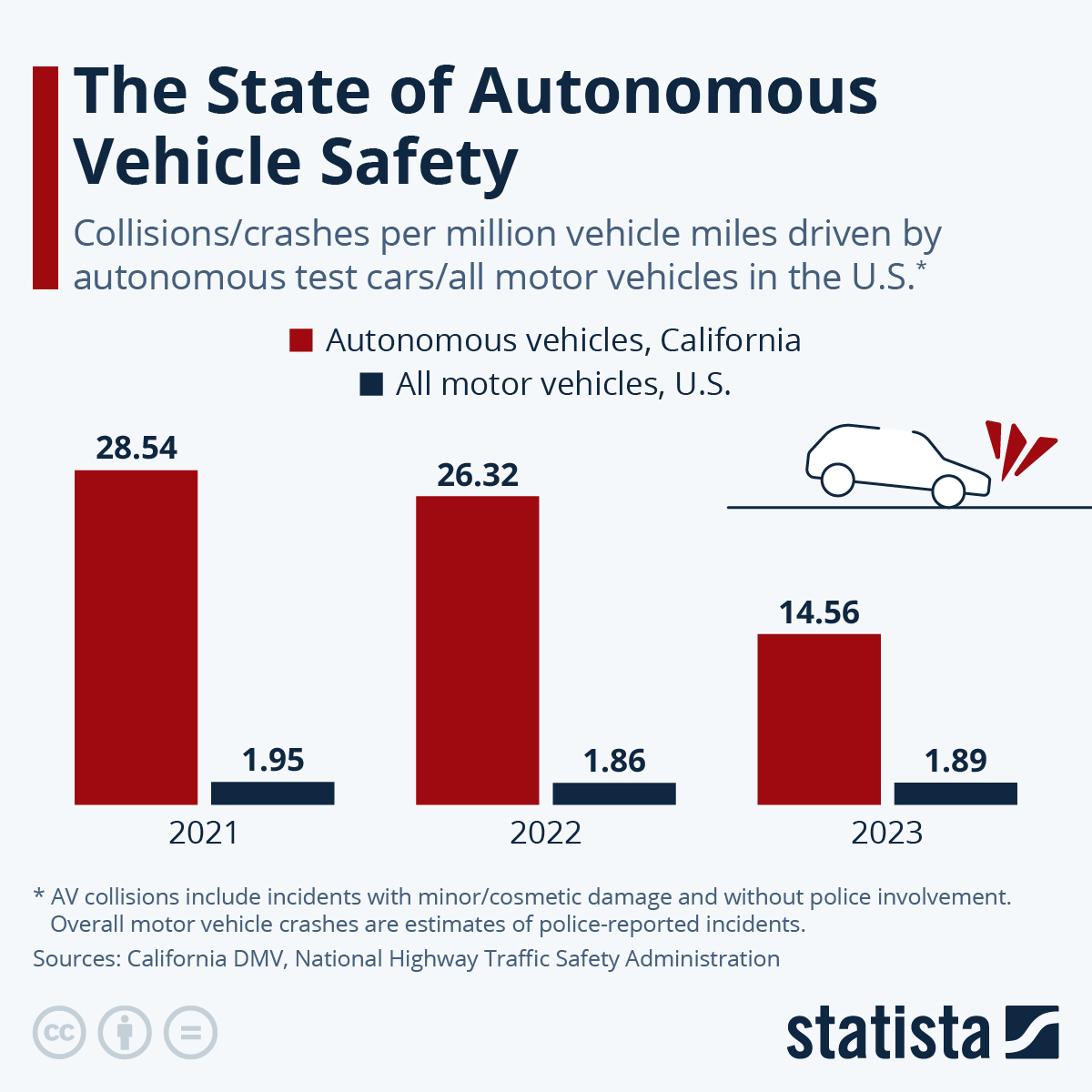

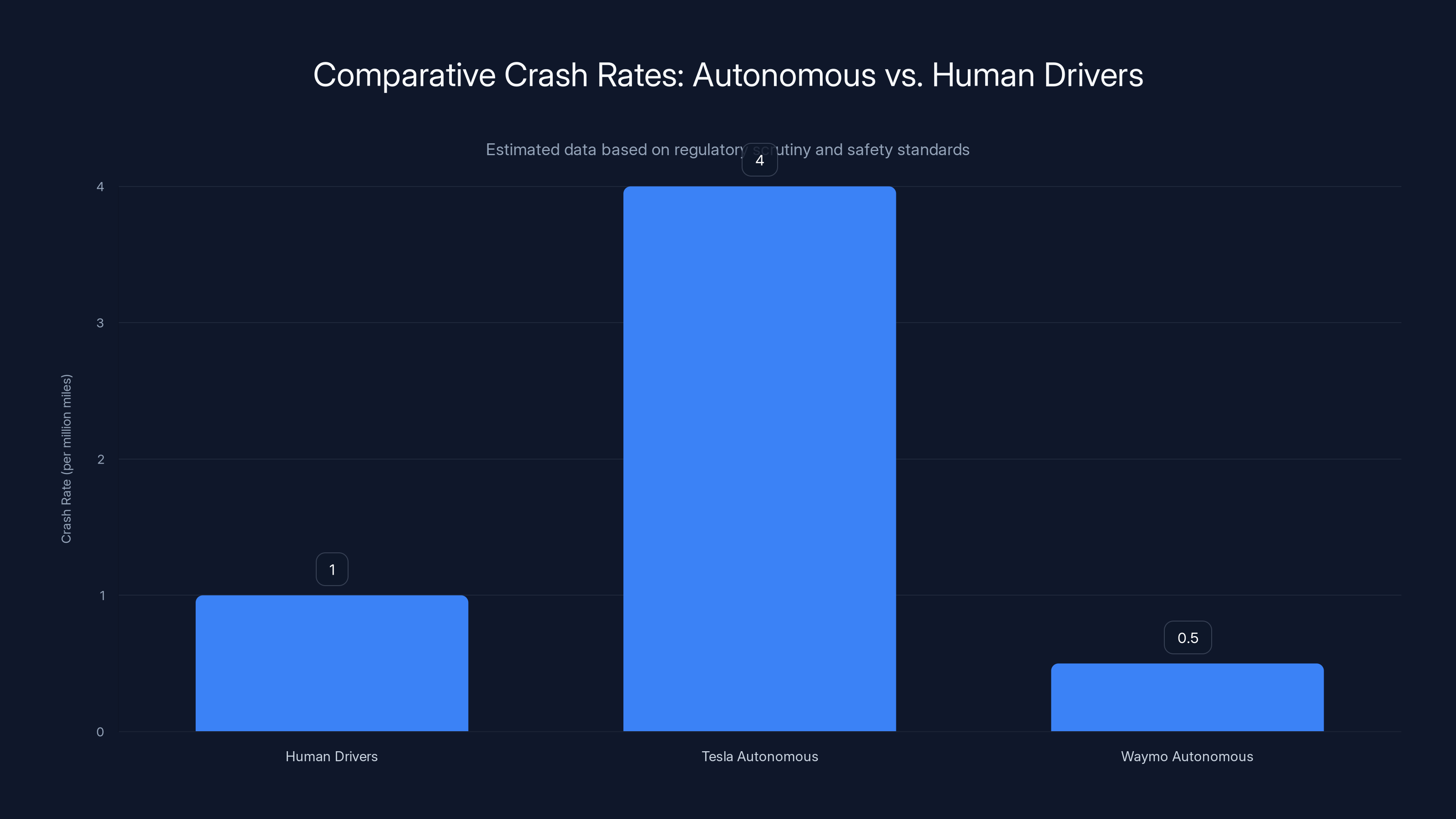

According to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), human drivers in urban environments like San Francisco average between 3 and 4 crashes per million miles driven. This varies based on driver age, experience, traffic conditions, and weather. Young drivers (16-25) average significantly higher rates. Professional drivers (taxi, ride-share) average lower rates due to selection effects and experience.

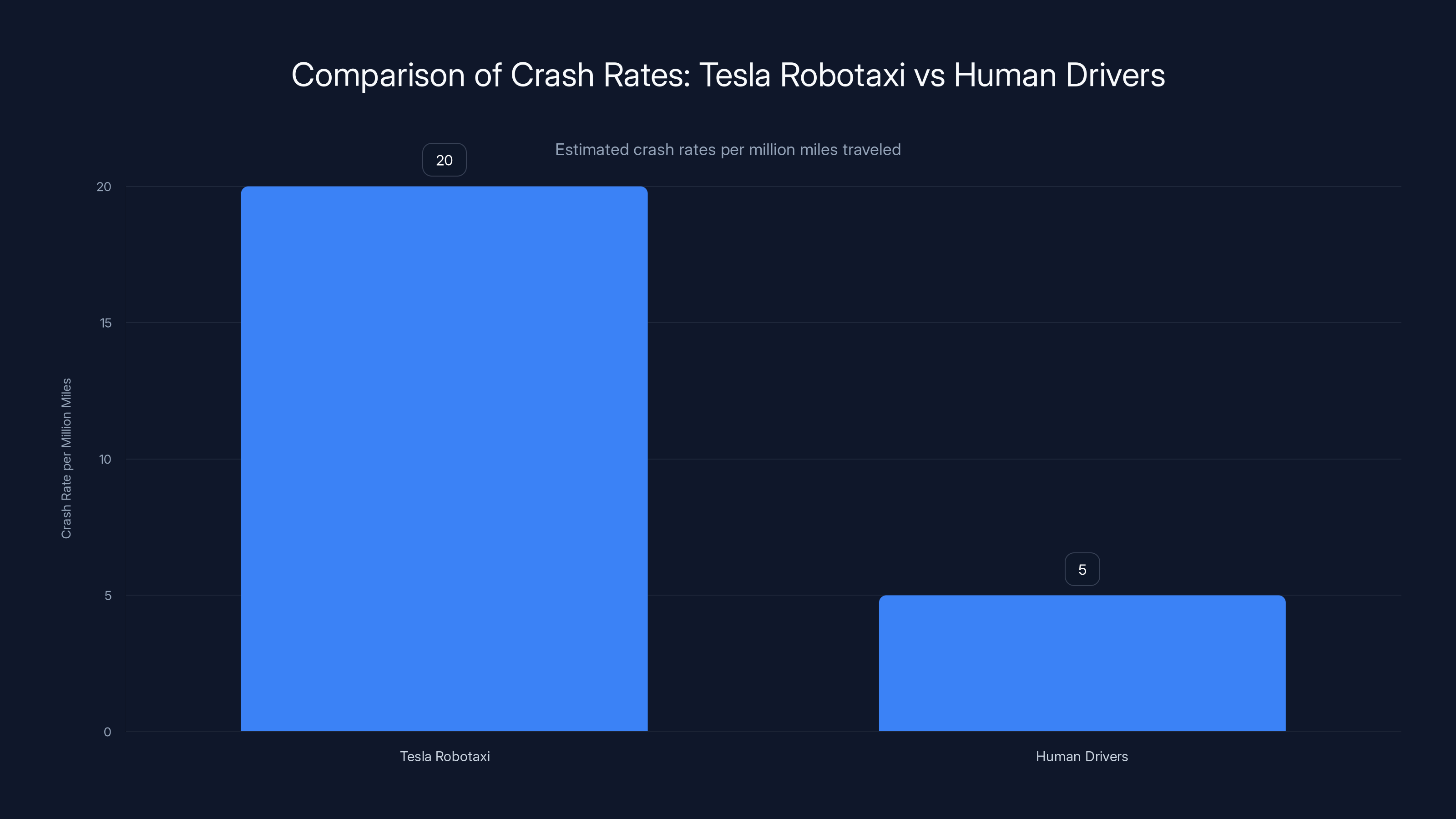

Tesla's Robotaxi fleet, in its early deployment phase, experienced roughly 14 crashes across approximately 700,000 miles of autonomous driving. That works out to approximately 20 crashes per million miles. The math is straightforward and doesn't require interpretation: it's four times higher than baseline human driver statistics.

Now, context matters. These numbers come from a very small dataset. 700,000 miles is statistically significant but not enormous in the context of autonomous systems research. One bad week could skew the numbers. Weather patterns in San Francisco could create artificial hazards. The data could be improving with newer software versions.

But here's what the data also shows: Tesla's crash rate isn't improving as quickly as the company's technology statements would suggest. The incidents weren't clustered early and then resolved through software updates. They've been distributed across the deployment timeline, suggesting they're not one-time calibration issues but rather persistent safety gaps.

Compare this to Waymo, which operates a more limited fleet but has achieved significantly lower crash rates per million miles. Waymo's approach uses multiple sensor types, more conservative operational design domains, and significantly more testing before public deployment. Their published data shows crash rates closer to human drivers or better, particularly in controlled corridors.

That gap between Tesla and Waymo isn't an accident of statistics. It reflects different safety philosophies. Waymo asks: how much testing is enough before we deploy? Tesla asks: how can we deploy and improve through real-world data? Both approaches have merit, but they produce different safety outcomes in the early stages.

Tesla's Robotaxi experiences four times the crash rate of human drivers per million miles, highlighting the importance of context in interpreting safety data. Estimated data.

Why the Crashes Are Happening

Tesla's autonomous driving system makes particular decisions about how to perceive and react to driving scenarios. Understanding why crashes occur requires looking at the system's known limitations.

Camera-only vision systems struggle with certain scenarios that human eyes handle easily. Glare at certain times of day can cause saturation in the image sensors. Rain and snow reduce visual clarity in ways that humans perceive contextually but cameras perceive as noise. Occlusions (when one object blocks the view of another) are handled probabilistically by neural networks rather than with the certainty that LIDAR would provide.

Second, Tesla's system has difficulty with unusual situations that fall outside the training distribution. If a situation resembles something the neural network has learned extensively, the system handles it well. If it's novel or rare, the system can make catastrophic errors. A partially obscured pedestrian, an unusual traffic pattern, or construction zones can all trigger suboptimal responses.

Third, there's the latency question. The system processes visual data, runs inference through neural networks, and produces control outputs. This all takes time—typically 100-200 milliseconds. In scenarios where faster response would help, that latency becomes a liability. A car braking or swerving unexpectedly ahead of you gives the Robotaxi less time to react than a human driver who's already paying attention.

A specific incident from Tesla's deployment illustrates this. A Robotaxi struck the rear of a vehicle that had stopped suddenly. The scenario probably looked like this: the target vehicle braked harder than the Robotaxi's predictive model expected, creating a gap that the decision-making system didn't account for. The neural network probably estimated stopping distance based on typical driving patterns, but this wasn't typical. By the time corrective action could be taken, the collision was inevitable.

These aren't bugs in the traditional sense. They're expressions of the fundamental challenge in autonomous driving: how do you train a system to handle every possible scenario when you can't predict all possible scenarios in advance?

The Cybercab Announcement and Its Timing

Here's where the narrative becomes interesting from a business perspective. Tesla announced the Cybercab launch while the Robotaxi crash data was accumulating. The timing wasn't coincidental. It was strategic.

By introducing the Cybercab—a new, cleaner, more purpose-built autonomous vehicle—Tesla could argue that previous incidents were about using consumer vehicles for autonomous purposes. The Cybercab, designed from the ground up for robotaxi service, would presumably avoid the design compromises that made human-driven Teslas less suitable for autonomous operation.

The Cybercab has advantages worth noting. Its interior is designed without the complex controls that might confuse autonomous navigation logic. Its sensor mounting is optimized rather than retrofitted. Its electrical architecture was built with autonomous operation in mind. These are legitimate engineering improvements.

But here's the catch: the Cybercab still uses the same camera-based autonomous driving system. It still relies on the same neural network architecture. The fundamental approach to perception and decision-making doesn't change. So while the hardware form factor improves, the core safety challenges persist.

Tesla positioned the Cybercab announcement to shift conversation from "why are your Robotaxis crashing?" to "look at this revolutionary new vehicle!" That's smart marketing. But it doesn't resolve the underlying safety question. If the autonomous driving system that crashes four times per million miles is also the system powering the Cybercab, then the form factor improvement doesn't automatically improve the safety metrics.

Investors and analysts picked up on this nuance. Some praised the Cybercab's design while expressing concern about the safety data. The Cybercab launch became a test case for whether Tesla could push the conversation forward despite contradictory evidence.

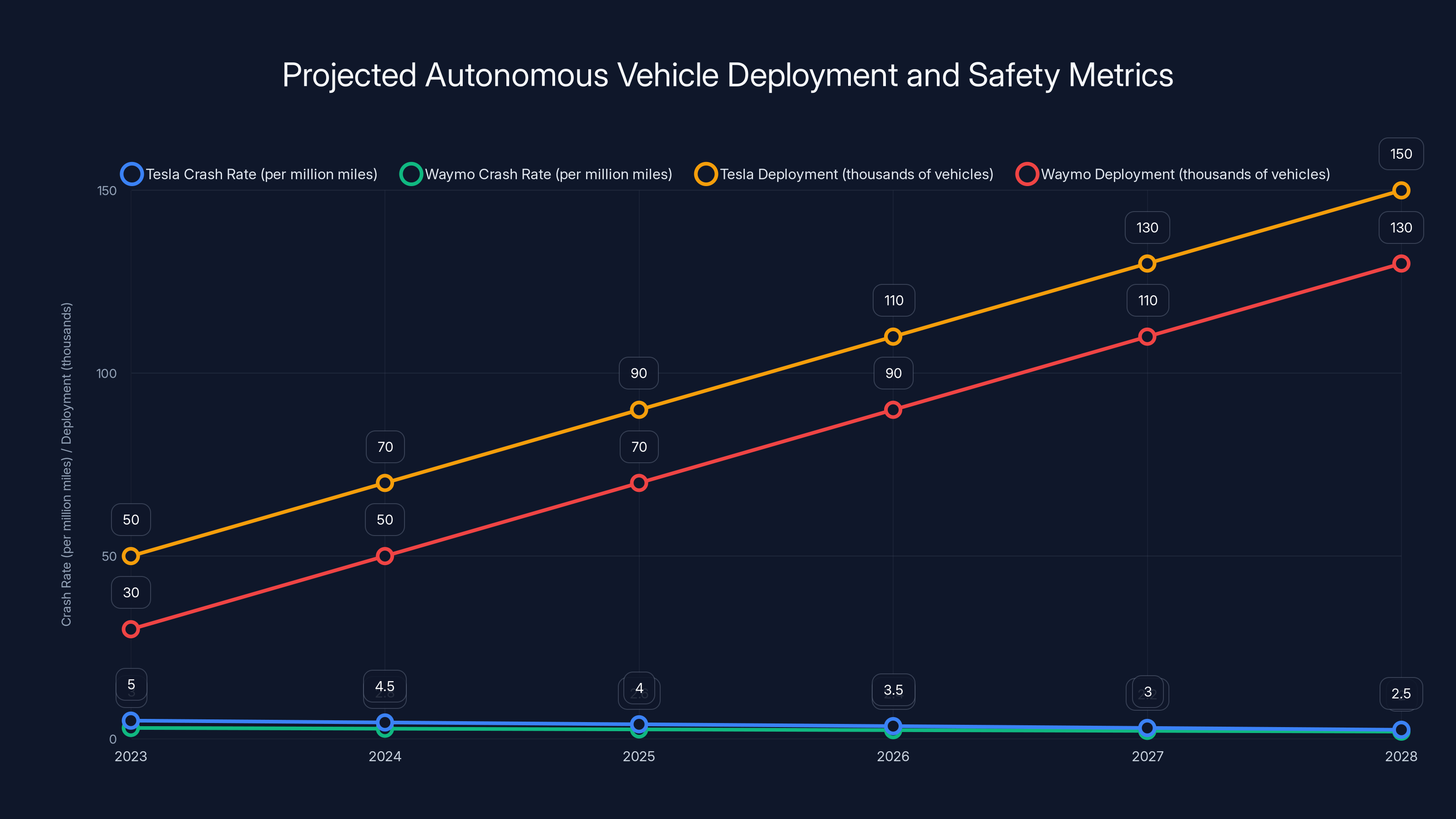

The chart projects a decline in crash rates for both Tesla and Waymo, with Waymo maintaining a lower rate. Deployment of autonomous vehicles is expected to increase significantly for both companies. Estimated data.

Regulatory Response and Safety Standards

The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) has been paying attention. The agency that oversees vehicle safety standards has begun investigating Tesla's autonomous driving claims, not because they're automatically skeptical, but because the crash data warrants scrutiny.

Regulatory agencies don't exist to prevent innovation. They exist to prevent harm. When crash rates are four times higher than human drivers, that triggers investigation regardless of the company's reputation or the potential of the technology.

What makes this situation complex is that there's no established federal safety standard specifically for autonomous vehicles. NHTSA has guidelines and recommendations, but no mandatory requirements for autonomous systems to match human driver safety before deployment. This regulatory gap is exactly what allows Tesla to operate the Robotaxi despite the higher crash rates.

Some states have attempted to fill this gap. California, where Tesla's Robotaxi operates, has pushed for more stringent testing requirements. But implementation lags behind regulation in many cases. The rules exist on paper but enforcement is uneven.

Waymo navigated this space differently by achieving very high safety metrics before expanding deployment significantly. That conservative approach meant slower growth but higher public confidence. Tesla's approach prioritizes deployment speed and real-world learning, accepting higher initial crash rates as a trade-off.

Insurance companies are also responding. Some refuse to insure autonomous vehicles operating below certain safety thresholds. Others price insurance so high that it becomes economically irrational. These market mechanisms create pressure on companies to improve safety metrics even without regulatory mandates.

The Sensor Choice: Why Camera-Only Matters

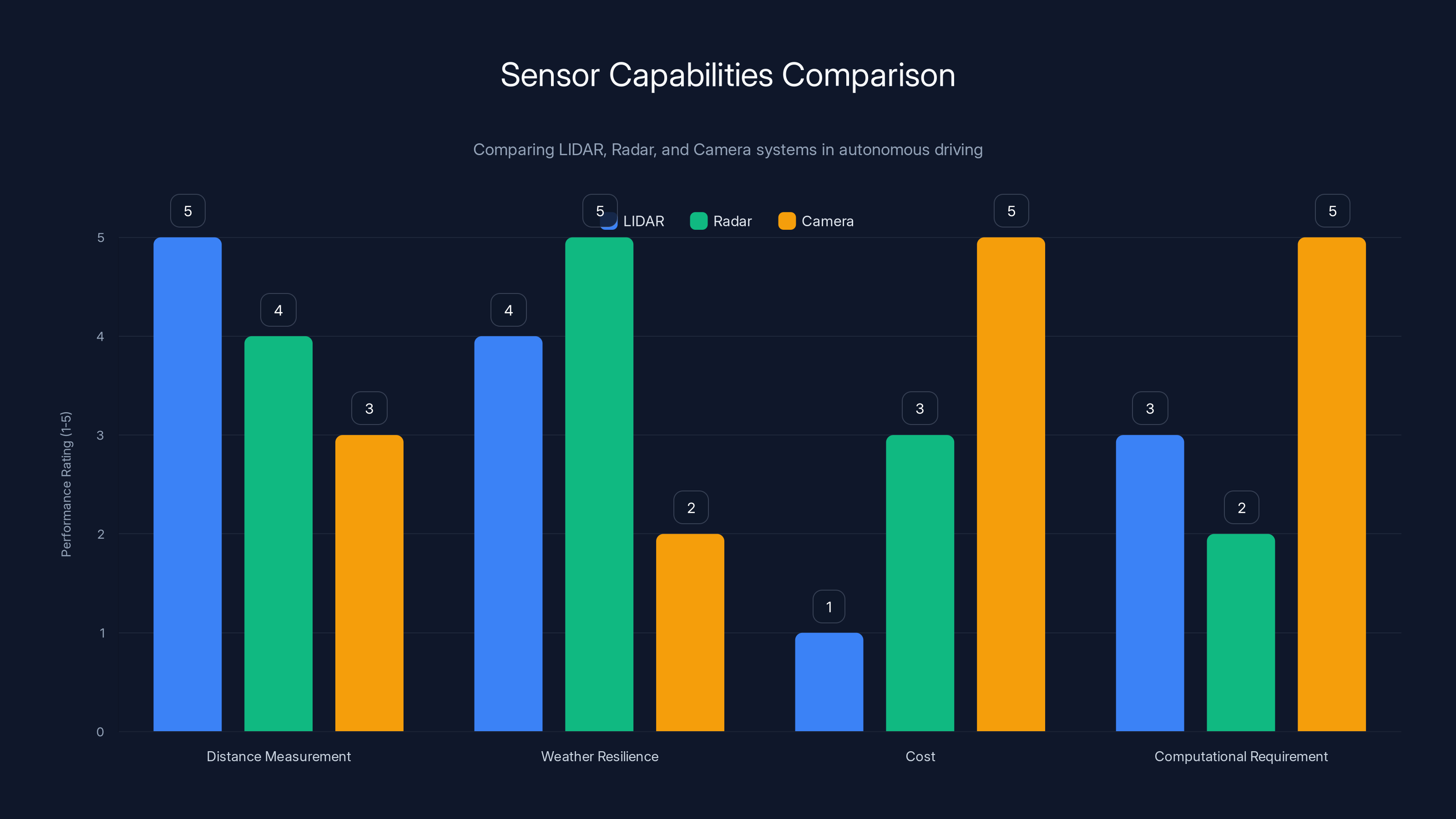

Tesla's decision to use only cameras for autonomous driving is central to understanding why crash rates are higher. This isn't a trivial engineering choice. It's a fundamental architectural decision with safety implications.

LIDAR systems (Light Detection and Ranging) create a three-dimensional map of the environment by bouncing laser pulses off objects and measuring return time. They measure distance directly, independently of lighting conditions. Rain, fog, and darkness don't significantly degrade LIDAR's performance. LIDAR cannot be fooled by reflections or shadows the way camera systems can be.

Radar systems measure velocity and distance using electromagnetic radiation. They work exceptionally well in poor visibility and can detect objects moving at high speeds. They're excellent for highway driving scenarios.

Camera systems see the world as humans do, capturing color, texture, and visual patterns. But they struggle with the scenarios LIDAR handles easily. They require significant computational resources to infer depth and distance. They're vulnerable to weather, lighting, and certain visual illusions.

Tesla chose cameras because the company believed (and has argued since at least 2014) that camera-only systems with advanced neural networks would eventually surpass multi-sensor approaches. The theory is mathematically sound. If you can process visual information with sufficient sophistication, you can extract all the information that LIDAR or radar would provide.

But the theory and practice have diverged. The neural networks are good, but they're not yet good enough to consistently match multi-sensor safety records. The crash data reflects this gap.

Elon Musk has been publicly critical of LIDAR, calling it expensive and unnecessary. He's not wrong about the cost—LIDAR sensors have historically been extremely expensive. And he's not wrong that theoretically, cameras should suffice. But theoretically perfect and practically safe are different standards when the cost of failure is measured in injured people.

Waymo's multi-sensor approach adds cost and complexity. It also adds redundancy. If one sensor type fails or is degraded, other sensors can compensate. Tesla's approach optimizes for efficiency and cost. That optimization carries safety trade-offs that the crash data makes visible.

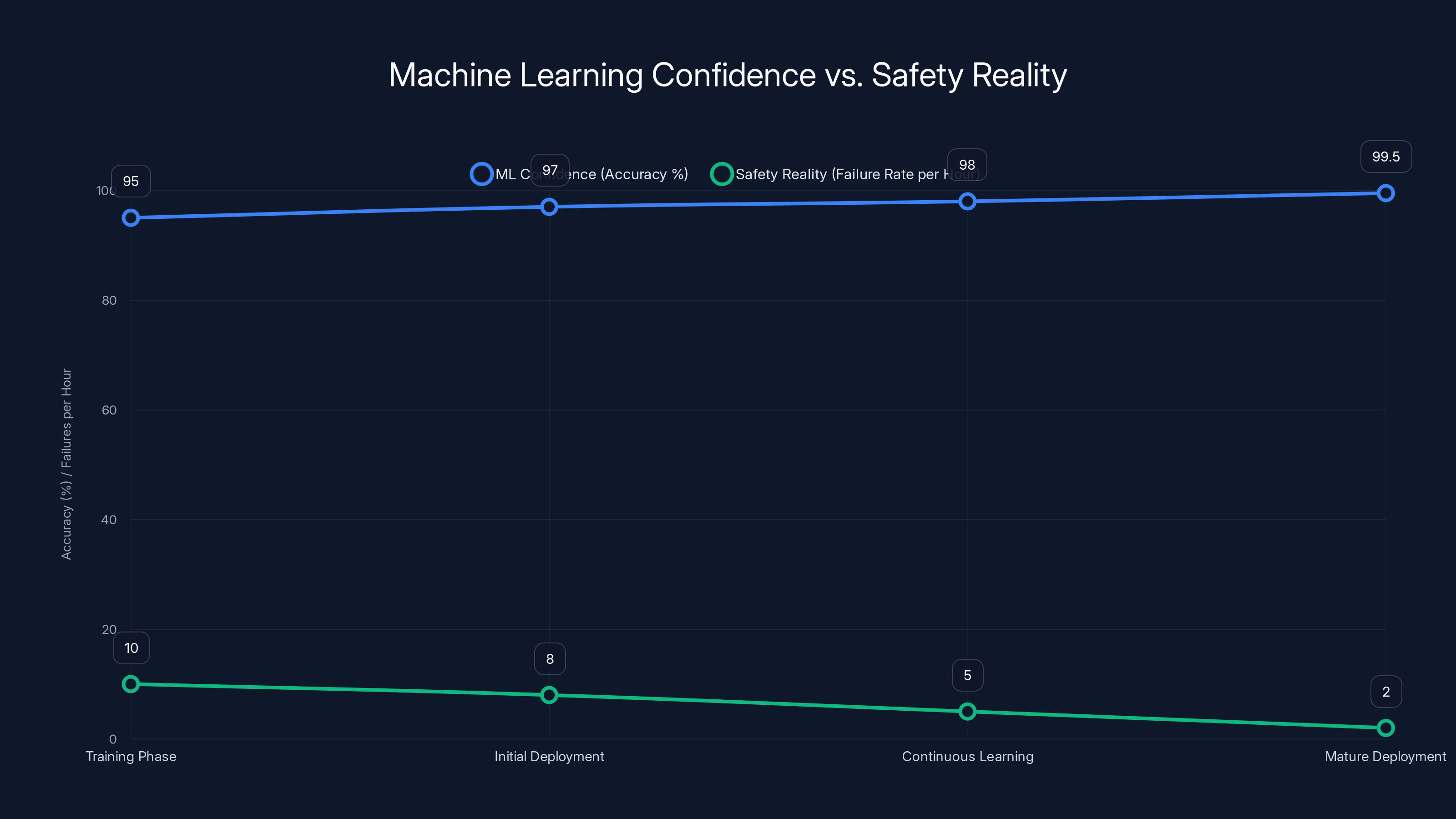

This chart illustrates the gap between machine learning confidence and real-world safety. As accuracy improves, the failure rate decreases, but initial deployment stages show higher failure rates. Estimated data.

Machine Learning Confidence vs. Safety Reality

Here's a concept that matters for understanding autonomous vehicles but rarely gets discussed clearly: the difference between a system that's good at its training task and a system that's safe in the real world.

Tesla's neural networks are trained on millions of miles of real driving data. By many machine learning metrics, these networks are remarkably sophisticated. They can predict human driver behavior. They can identify objects in images with high accuracy. They can make reasonable driving decisions in most common scenarios.

But machine learning confidence and safety are different concepts. A neural network can be 99.5% accurate at identifying objects in images and still fail catastrophically in rare scenarios where the remaining 0.5% matters. If 99.5% accuracy means one failure per 200 images, and you're processing 30 images per second, that's one failure every 6-7 seconds of driving—unacceptable for autonomous vehicles.

The crash data suggests that Tesla's system has learned well within its training distribution but struggles outside it. Rare weather events, unusual traffic patterns, and novel scenarios cause the system to make suboptimal decisions. This is a known limitation of current neural network approaches.

Machine learning researchers call this "distribution shift." The system learns patterns in the training data, but the real world always contains scenarios the training data didn't represent. The wider the gap between training distribution and real-world distribution, the more failures you'd expect to see.

Tesla's approach is to continuously feed real-world driving data back into the neural networks, improving the models over time. That's a valid strategy. It's also a strategy that requires tolerating higher failure rates during the learning period.

This is where the ethical dimension becomes unavoidable. How many crashes is acceptable in the service of learning? Who bears the cost of those crashes? The company? The insurance system? The people in cars that get hit?

Comparing to Other Autonomous Vehicle Programs

Tesla's crash rate makes more sense when you understand what the alternatives achieved and how they did it.

Waymo, which operates in Phoenix, San Francisco, and other cities, has published safety data showing crash rates comparable to human drivers or better. How did they achieve this? Primarily through extensive pre-deployment testing, careful operational design domain definition, and multi-sensor redundancy. Waymo tested their vehicles for millions of miles before public deployment. They didn't rush to real-world operation.

Cruise, which operated in San Francisco (and was subsequently wound down after safety incidents), achieved lower crash rates than Tesla initially but also struggled with edge cases and unusual scenarios. Cruise's failure highlighted the reality that even with more careful deployment than Tesla, autonomous driving is harder than it looks.

Auisai and other regional operators in China have attempted to bypass some safety concerns through limited operational domains (specific routes, specific times) and lower speeds. This approach trades convenience for safety.

The pattern is clear: companies that sacrifice deployment speed to achieve higher safety metrics end up with better results. Companies that prioritize getting to market quickly end up with higher crash rates. There's no way around this trade-off with current technology.

Tesla could have chosen to be more like Waymo. The company has the resources. The decision not to reflects company culture and strategy. Tesla tends to believe that real-world feedback improves systems faster than extensive pre-deployment testing. This philosophy has worked in some contexts (iterative software updates, manufacturing efficiency). It hasn't produced superior safety outcomes in autonomous driving, at least not yet.

Tesla's autonomous vehicles reportedly have a crash rate four times higher than human drivers, while Waymo maintains a much lower rate, highlighting different safety strategies. Estimated data.

What the Four-Times Number Actually Means

Let's make sure we're interpreting the safety data correctly because precision matters here.

When we say Tesla's Robotaxi crashes four times more frequently than human drivers, we mean: per unit distance traveled (one million miles), Tesla's fleet has experienced four times as many accident events. This is a rate comparison, not an absolute statement about severity or injury risk.

Important caveat: "accident" is defined differently in different datasets. NHTSA defines reportable accidents as those with injury or significant property damage. Tesla's internal tracking might use a broader definition that includes minor incidents. The comparison assumes relatively consistent definitions, but different data sources could produce different numbers.

Second caveat: human driver statistics are not uniform across conditions. Urban driving produces different crash rates than highway driving. Young drivers crash more than experienced drivers. Weather, time of day, and traffic density all affect rates. Tesla's Robotaxi operates only in urban environments with specific traffic patterns and weather patterns. A truly apples-to-apples comparison would match human driver statistics to identical conditions and routes, which no published study has done comprehensively.

Third caveat: the sample size is relatively small. 14 incidents across 700,000 miles is a reasonable dataset for analysis but not enormous. Statistical confidence intervals are relatively wide. The "true" underlying crash rate could be somewhat higher or lower than the point estimate of 20 per million miles.

Fourth caveat: crash severity matters. Are these low-speed parking incidents or highway collisions? Tesla's reported incidents appear to be mostly low-speed, lower-severity accidents. A single high-speed catastrophic accident would be worse than ten minor fender-benders, even though the numerator is smaller. Frequency alone doesn't capture this dimension of safety.

All of these caveats are true. And none of them change the fundamental fact: the available data shows Tesla's crash rate is higher than human drivers in comparable conditions. By how much, under what conditions, and whether this is improving are all legitimate questions. But the basic reality is what it is.

The Economics of Autonomous Vehicles and Safety Trade-offs

Underlying the technical discussion is an economic reality that shapes all decisions about autonomous vehicle deployment.

Autonomous vehicles are expensive to develop. The perception systems, computing hardware, neural network training, and validation testing require enormous capital investment. Companies can recoup that investment only if they can deploy the technology broadly and capture enough value to justify the expense.

This creates pressure to deploy before the technology is perfect. Perfect safety is impossible (even human drivers crash). So companies must choose how much risk they'll accept in pursuit of profitability. Tesla apparently chose to accept higher crash rates in exchange for faster deployment and faster learning from real-world data.

Waymo chose differently, accepting slower profitability in exchange for higher safety metrics and stronger public confidence. Both strategies have logic, but they produce different outcomes in the near term.

Insurance economics will eventually force convergence. If autonomous vehicles have significantly higher crash rates, insurance costs will make them economically unviable. This creates pressure on companies to improve safety or face market punishment. Tesla's strategy of deploying and improving might eventually prove faster than competitors' more cautious approach, or it might prove unsustainable if insurance costs become prohibitive.

The Robotaxi service is meant to be profitable through passenger revenue, not just by selling vehicles. For passenger revenue to work economically, the service must achieve ride costs that are competitive with human drivers. If insurance costs are too high because crash rates are too high, profitability becomes impossible. This economic pressure might accomplish what regulation hasn't yet: forcing Tesla to improve safety metrics.

LIDAR excels in distance measurement and weather resilience, but is costly. Cameras are cost-effective but require high computational power and struggle in adverse conditions. Estimated data.

Software Updates and Learning: Can the System Improve Fast Enough?

Tesla's strategy assumes that the autonomous driving system will improve rapidly through software updates informed by real-world crash data. This assumption is critical to their economic model.

How fast can neural networks improve when fed continuous real-world feedback? The answer is: it depends. If the crashes reveal clear, addressable issues (e.g., "the system doesn't detect this type of pedestrian silhouette"), improvements can be relatively fast. Software updates can deploy across the entire fleet within days.

But if the crashes reveal fundamental limitations of the camera-only approach, improvements are much slower. You can't fix a LIDAR limitation by updating software running on cameras. You'd need hardware changes, which require new vehicles, which costs billions of dollars.

Some of Tesla's crashes likely fall into the first category (addressable through neural network improvement). Some likely fall into the second category (fundamental architectural limitations). Without Tesla publishing detailed incident analysis, we can only infer which is which.

What we do know is that the incident rate hasn't dramatically improved despite months of real-world data collection. If the improvements were working as planned, we'd expect to see either fewer incidents or at least clear evidence of improvement trajectory. The absence of published improvement data suggests either that improvements aren't happening as quickly as expected, or that Tesla isn't disclosing the data.

This gets at a core problem with Tesla's transparency on autonomous vehicle safety. The company publishes neither detailed incident analysis nor safety metrics on any regular basis. Competitors like Waymo disclose more safety data, which actually builds confidence even when the data reveals challenges. Tesla's opacity creates justified skepticism.

The Cybercab's Safety Implications

Now we return to where this began: the Cybercab announcement. Does the new vehicle architecture address the safety concerns revealed by Robotaxi crashes?

Partially. The Cybercab's purpose-built design eliminates some sources of confusion for an autonomous system. Human controls that might distract or confuse decision-making don't exist. The vehicle's controls and interfaces were designed with autonomy in mind. Sensor mounting is optimized rather than retrofitted. These are genuine improvements to the deployment platform.

But the Cybercab doesn't change the fundamental perception architecture. It's still camera-only. It's still running neural networks trained on visual data. It's still vulnerable to the same edge cases that caused the Robotaxi crashes. Different form factor doesn't mean different safety outcomes if the underlying system is unchanged.

That said, purpose-built vehicles probably are safer than adapted consumer vehicles. The Cybercab eliminates failure modes that the Robotaxi experiences (user interface confusion, unfamiliar control schemes). If those account for a meaningful fraction of the Robotaxi crashes, the Cybercab could see improvement.

But expecting dramatic safety improvement solely from vehicle design is unrealistic. The core safety challenge is perception and decision-making, not vehicle mechanics.

Investors and analysts understood this nuance. The Cybercab announcement pushed Tesla's stock up, but industry observers noted that the safety question wasn't resolved. The vehicle is genuinely innovative. The safety record still needs improvement. Both things are true.

Public Perception and Trust

Here's what the crash data has done that Tesla didn't intend: it's made the public genuinely skeptical of autonomous vehicle safety claims across the industry.

Waymo had built significant public confidence through conservative deployment and published safety data. Tesla's higher crash rates created a reputational spillover effect. When people hear "Tesla Robotaxi crashes four times more than humans," they become more skeptical of all autonomous vehicles, not just Tesla's.

This matters because autonomous vehicles need public adoption to scale. If people don't trust them, regulation will restrict them. If regulation restricts them, profitability becomes difficult. Tesla's higher crash rates created a trust problem for the entire industry.

Surveys have shown that autonomous vehicle adoption depends heavily on reported safety metrics. When safety numbers are worse than human drivers, adoption hesitation increases dramatically. Tesla's situation illustrates this dynamic in real time.

The company's response has been to focus on the Cybercab's potential rather than address the safety criticism directly. That's strategically understandable but doesn't actually rebuild trust. Trust rebuilds through consistent demonstration of improving safety metrics.

Interestingly, people's abstract confidence in autonomous vehicles ("I think self-driving cars will be safe eventually") is often higher than their willingness to ride in one today. They understand the technology is young and improving. But they also understand the trade-off between early deployment and safety. The Robotaxi crash rate makes that trade-off concrete rather than theoretical.

Looking Forward: What Has to Change

For Tesla (and the autonomous vehicle industry more broadly) to achieve mainstream adoption, the safety metrics need to improve. The question is how, and whether current approaches are sufficient.

Option one: Camera-only systems with Tesla's architecture improve faster than skeptics expect. Neural networks continue learning from real-world data. Within 12-18 months, crash rates drop below human driver levels. This outcome would validate Tesla's approach and justify the higher initial crash rates as acceptable cost of learning.

Option two: Tesla realizes that camera-only approaches have fundamental limitations and adds sensor redundancy (LIDAR, radar) to future deployments. This would contradict prior strategic choices but would likely improve safety metrics. It would also increase costs, which might reduce profitability.

Option three: Regulation forces changes before Tesla wants to make them. NHTSA or state authorities mandate minimum safety thresholds before broader deployment is permitted. This would slow Tesla's timeline but might ultimately protect the company from catastrophic incidents.

Option four: A major incident (injury or death) occurs, creating liability and regulatory backlash that forces comprehensive system redesign and additional testing. This would be catastrophic for Tesla but wouldn't be unprecedented in automotive history.

Which outcome is most likely? Probably some combination of all four. Crashes will continue, but at hopefully declining rates. Regulation will tighten, but not prevent deployment. Tesla might add sensor redundancy selectively. And critical incidents might occur (though hopefully without serious injury).

The Cybercab is part of this trajectory. It's a superior form factor for autonomous operation. But it's not a magic solution to the underlying perception and decision-making challenges. Safety improvement will require addressing those fundamentals, whether through better neural networks, additional sensors, or both.

The Uncomfortable Truth About Autonomous Vehicle Development

Let's acknowledge what the crash data and the Cybercab announcement together reveal: we're still in the early stages of autonomous vehicle development, despite the confident marketing.

Tesla's Robotaxi isn't a complete failure. It works in many scenarios. It solves real problems for some users (people who don't want to drive). It demonstrates that camera-based autonomous driving at the level Tesla has achieved is genuinely difficult and genuinely impressive.

But the four-times crash rate is also real. It's not propaganda from skeptics. It's what the data shows. And it reveals that the problem is harder than the hype suggests.

The Cybercab is innovative. But innovation in form factor doesn't solve innovation challenges in perception and decision-making. The vehicle is a better platform for autonomous operation, but it's still running autonomous driving systems that crash more frequently than humans drive.

Both things are true simultaneously. And holding both realities together—recognizing the genuine achievement while not overlooking the genuine safety gap—is exactly what the industry needs.

Tesla will likely improve. The neural networks will get better. The fleet will accumulate more edge case experience. Eventually, crash rates might drop below human drivers. But "eventually" is not the same as "now." And the gap between marketing promises and current reality is exactly what makes the crash data so important.

The Cybercab represents where Tesla wants to be. The Robotaxi crash rate represents where Tesla is now. Understanding the gap between those two points is essential for anyone evaluating autonomous vehicle technology in 2025.

What Comes Next for Autonomous Vehicles

The next 12-18 months will be crucial for determining whether Tesla's approach proves viable or whether more conservative approaches (like Waymo's) establish themselves as the industry standard.

There are several key milestones to watch. First, will Tesla's crash rate improve measurably with the Cybercab rollout? If safety improves, it validates the theory that purpose-built vehicles can achieve better outcomes. If crash rates stay high, it suggests the core perception system limitations are the limiting factor.

Second, will regulatory pressure increase? NHTSA's investigation could lead to mandated safety standards that force changes across the industry. This would level the competitive playing field and possibly require Tesla to invest in additional safety improvements.

Third, will competitors achieve better safety metrics with different architectures? If Waymo or others demonstrate convincingly lower crash rates, the market will reward that safety advantage through adoption and insurance pricing.

Fourth, will the economics work? Can Tesla operate the Robotaxi profitably with current insurance costs and crash rates? If not, the business model needs adjustment.

The Cybercab announcement is step one in answering these questions. But the actual answers will come from real-world performance data over the next few years.

For consumers, the key lesson is simple: autonomous vehicle safety is still a work in progress. Don't assume that marketing hype reflects actual current capabilities. Look at the data. Ask hard questions about safety metrics. Companies that disclose problems are more trustworthy than companies that hide them. And remember that being skeptical of current autonomous vehicle safety is rational, not Luddite.

The technology will improve. Autonomous vehicles will probably be safer than human drivers eventually. But "eventually" still isn't "now."

FAQ

What is the Cybercab?

The Cybercab is Tesla's purpose-built autonomous vehicle designed specifically for robotaxi service. Unlike Tesla's previous Robotaxi service (which adapted consumer Tesla vehicles), the Cybercab was engineered from the ground up with autonomous operation in mind, including removal of manual controls, optimized sensor mounting, and a streamlined interior design for passenger comfort without driver controls.

How does Tesla's autonomous driving system work?

Tesla's Full Self-Driving (FSD) system relies on a camera-based perception approach, using eight cameras mounted around the vehicle to provide a 360-degree view. The system processes this visual data through neural networks trained on millions of miles of real driving to make decisions about acceleration, steering, and braking without human input. This camera-only approach differs from competitors like Waymo, which use LIDAR and radar for redundancy.

Why does Tesla use only cameras instead of LIDAR?

Tesla chose a camera-only approach because the company's leadership believes that advanced neural networks processing visual data can eventually match or exceed multi-sensor systems. This approach reduces hardware costs and complexity. However, the current data shows camera-only systems struggle with certain conditions like heavy rain, glare, and nighttime driving, contributing to higher crash rates compared to human drivers and multi-sensor systems.

What does the four-times crash rate actually mean?

Tesla's Robotaxi experiences approximately 20 crashes per million miles of autonomous driving, compared to approximately 3-4 crashes per million miles for human drivers in urban environments. This four-fold difference represents one of the key safety concerns about the current autonomous driving implementation, though it's important to note that most reported incidents have been low-speed, low-severity collisions.

Is the Cybercab safer than the Robotaxi?

The Cybercab has design improvements that should reduce certain types of incidents (like user interface confusion), but it uses the same underlying autonomous driving system as the Robotaxi. While purpose-built design is safer than adapting consumer vehicles, the core perception and decision-making architecture remains unchanged. Safety improvement will depend on whether the neural network systems improve through software updates and real-world learning.

How does Tesla compare to other autonomous vehicle companies?

Waymo, the leading competitor, achieves crash rates comparable to or better than human drivers through more extensive pre-deployment testing and multi-sensor redundancy. Cruise, which operated in San Francisco, wound down operations after safety concerns emerged. Tesla's strategy emphasizes faster real-world deployment with learning-from-mistakes approach, while Waymo prioritizes pre-deployment testing and safety validation. Both strategies have trade-offs between speed and safety.

Will regulators allow continued deployment despite higher crash rates?

Current federal regulations don't explicitly prohibit autonomous vehicles with crash rates higher than human drivers, which is why Tesla can operate legally. However, NHTSA is investigating Tesla's autonomous driving system, and states like California are considering stricter safety requirements. Regulatory standards are likely to tighten, potentially requiring higher safety thresholds before broader deployment is permitted.

What would make autonomous vehicles safer?

Immediate improvements could come from adding sensor redundancy (LIDAR and radar in addition to cameras), which would better handle edge cases like heavy rain and nighttime driving. Longer-term improvements depend on neural networks learning from accumulated real-world data. Companies could also implement more conservative operational design domains (limiting autonomous operation to specific routes and conditions) until safety metrics improve further.

How soon will autonomous vehicles be safer than human drivers?

This depends entirely on the technology and deployment strategy. Companies like Waymo may already be at or near human driver safety levels in their limited operational domains. Tesla is currently above human driver crash rates but may approach or exceed human safety within 12-24 months if neural network improvements accelerate. However, comprehensive autonomous driving across all conditions and locations is likely years away from achieving human-level safety.

Should I trust autonomous vehicles right now?

Automatic vehicles are showing promise but are not yet reliably safer than human drivers. Current best practice is to treat autonomous vehicle services as developing technology with trade-offs. Waymo's service, with published safety data and conservative deployment, is generally considered safer than Tesla's higher-crash-rate approach. As with any emerging technology, research the specific company's safety record and transparency before using their services.

Key Takeaways

- Tesla's Robotaxi experiences approximately 20 crashes per million miles, roughly four times higher than human driver rates of 3-4 crashes per million miles in urban environments

- The Cybercab is a genuine vehicle design improvement but uses the same camera-only autonomous driving system that produces the higher crash rates, so form factor changes alone won't resolve safety concerns

- Tesla's camera-only approach saves costs and is theoretically sound but lacks the sensor redundancy that competitors like Waymo use, making it more vulnerable to poor visibility and edge cases

- The company's strategy prioritizes real-world deployment and learning over extensive pre-deployment testing, creating higher crash rates but potentially faster improvement if neural networks improve as planned

- Regulatory agencies and insurance companies are beginning to pressure the autonomous vehicle industry toward higher safety standards, which could force Tesla to add sensor redundancy or improve neural network performance within 12-24 months

Related Articles

- Waymo's Remote Drivers Controversy: What Really Happens Behind the Wheel [2025]

- Why Waymo Pays DoorDash Drivers to Close Car Doors [2025]

- Robotaxis Meet Gig Economy: How Waymo Uses DoorDash to Close Doors [2025]

- Waymo's Fully Driverless Vehicles in Nashville: What It Means [2025]

- New York's Robotaxi Reversal: Why the Waymo Dream Died [2025]

- New York Pulls Back on Robotaxi Expansion: What Happened and Why [2025]

![Tesla's Cybercab Launch vs. Robotaxi Crash Rate Reality [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/tesla-s-cybercab-launch-vs-robotaxi-crash-rate-reality-2025/image-1-1771551400359.jpg)