Waymo's Fully Driverless Vehicles in Nashville: What It Means for the Future of Autonomous Transportation

Something quietly shifted in Nashville last year. Waymo's vehicles started rolling through the streets without a human safety driver sitting in the front seat—nobody ready to grab the wheel if things went sideways. For most people, that's just another autonomous vehicle experiment in another American city. But for anyone paying attention to how we're actually going to get around in the future, this moment matters.

Waymo hit a genuine milestone. Not the kind that makes headlines for a day and gets forgotten. The kind that signals we're moving from "controlled testing" to "something that actually works." The company has been chasing full autonomy for over a decade. They've crashed into gates, failed to detect school buses, and had to issue recalls more times than anyone really wants to count. But somewhere in that messy process, the technology got better. Good enough that a major city is letting them operate without a safety net.

Here's what you need to know: Waymo announced in September 2025 that it planned to bring robotaxis to Nashville. Within months, they'd removed their safety drivers entirely. Now the company is running fully autonomous vehicles around the city before opening paid rides to the public sometime in 2025. That timeline might sound fast. It's actually incredibly deliberate. Each city is different. Different traffic patterns, different weather, different road conditions. Waymo doesn't just copy and paste their San Francisco playbook into Nashville. They map it. Test it. Update their software. Wait. Test more.

But here's the thing that keeps getting buried in the technical details: this is actually happening. Not in some distant future. Not in a controlled test track. On real streets. With real pedestrians. With real consequences if something breaks.

This article dives into what Waymo's Nashville achievement actually means, why it matters, what could still go wrong, and where autonomous vehicles are headed next. Whether you're curious about self-driving technology, interested in the transportation future, or just wondering why your Uber might soon have nobody in the driver's seat, you're in the right place.

TL; DR

- Waymo removed safety drivers from its Nashville testing fleet, marking a major step toward fully autonomous operation in a new city

- Testing before launch is crucial: Waymo maps each city, tests software extensively, and waits weeks or months before offering paid rides

- Safety has improved significantly, though recalls still happen, most recently for failing to detect school buses

- Paid rides coming in 2025 for Nashville residents, with expansion planned to dozens of cities worldwide

- Revenue opportunity is enormous: autonomous vehicle services could fundamentally reshape urban transportation and generate billions in revenue

- Competition is intensifying: Tesla, Apple, and other companies are racing to deploy their own autonomous systems

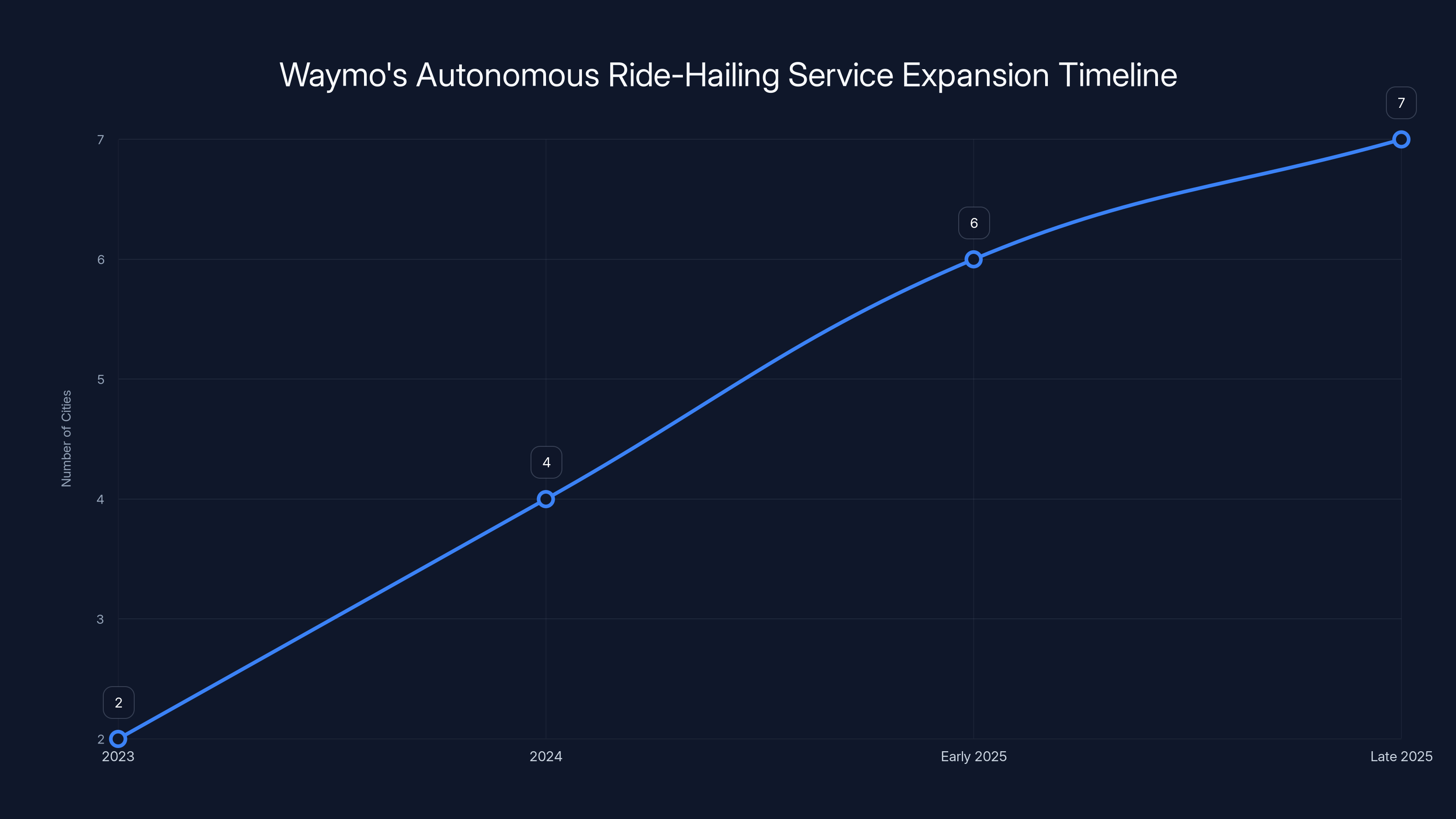

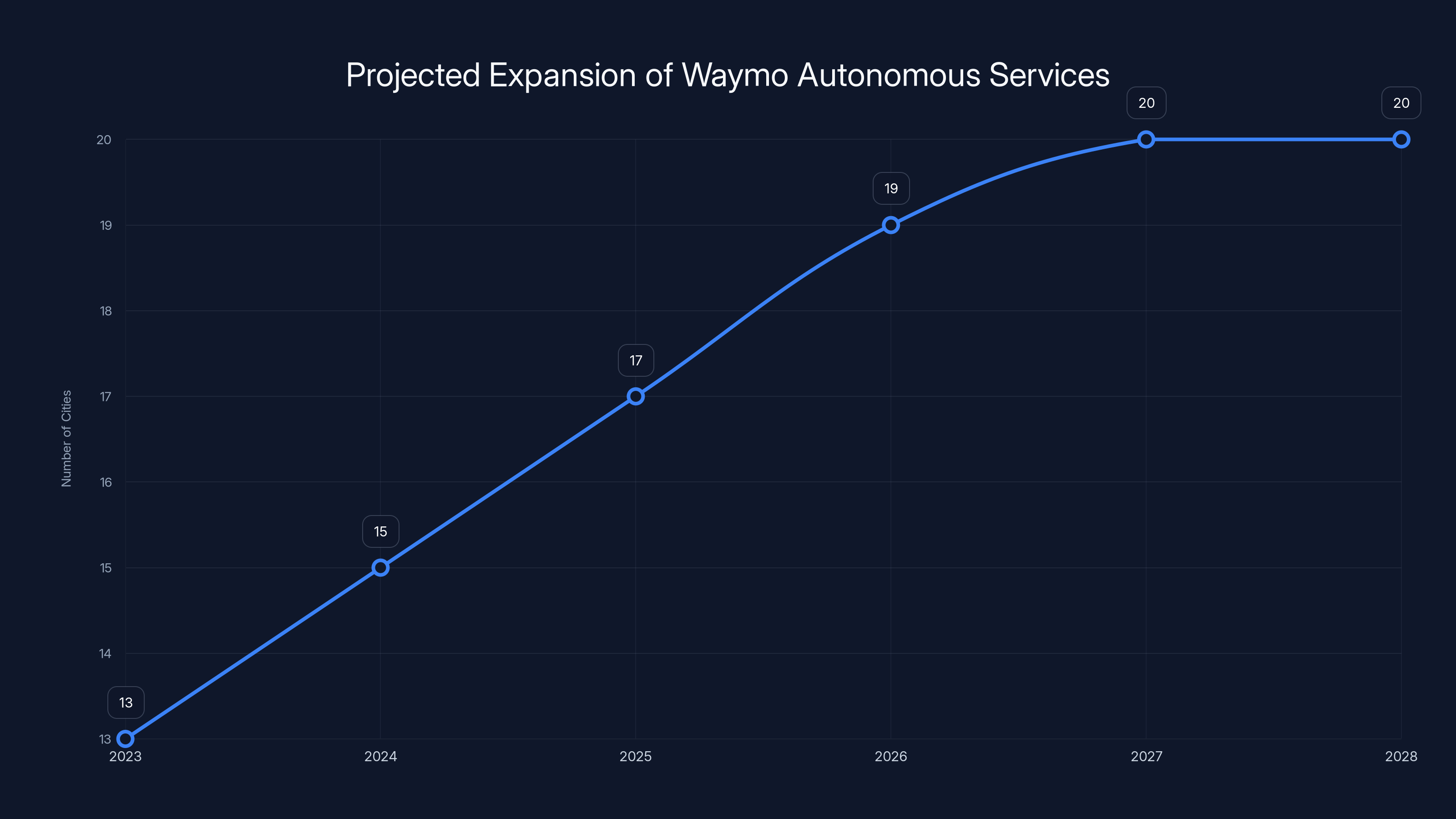

Waymo's autonomous ride-hailing service is projected to expand from 2 cities in 2023 to 7 cities by late 2025, including the anticipated launch in Nashville. Estimated data based on current trends.

What Waymo Actually Achieved in Nashville

Removing safety drivers from a testing fleet sounds deceptively simple. In practice, it's proof that Waymo's autonomous systems work reliably enough that a team of engineers has signed off on letting them operate without a human backup. That doesn't mean the cars are perfect. It means they're reliable enough that the company is willing to take the liability risk.

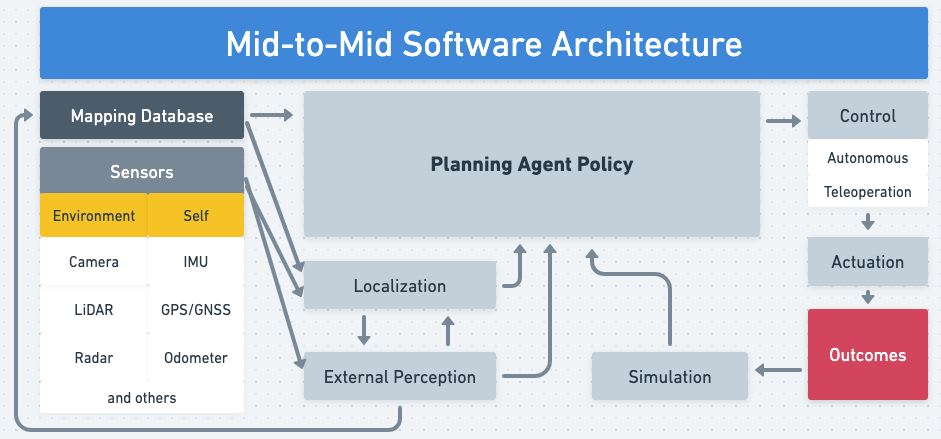

To understand why this matters, you need to understand what's actually happening in those cars. Waymo's system isn't just a computer looking at camera feeds. It's multiple overlapping systems working simultaneously. There's lidar, which uses laser pulses to build a 3D map of everything around the vehicle. There are cameras pointing in every direction. There's radar that works through rain, fog, and darkness when cameras struggle. There's real-time software processing all of that data, identifying pedestrians, predicting their behavior, deciding when to accelerate, brake, or turn.

When a safety driver was sitting in the front seat, they were there as a backup. Not a perfect backup—studies show that human safety drivers get bored, zone out, and aren't actually paying attention most of the time. But they existed. They represented a line of defense if something went genuinely wrong.

Now that line of defense is gone in Nashville. Waymo is saying that their autonomous system can handle the driving better than humans would. That's a wild claim. But when you look at the actual driving data, it's starting to hold up.

The company operates in six cities with driverless service: San Francisco, Los Angeles, Phoenix, Miami, and Atlanta and Austin through Uber partnerships. All of those deployments prove the same thing: when you spend enough time testing, when you iterate enough, when you actually listen to failure data, autonomous systems get competent. Not perfect. Competent.

Nashville is the next proving ground. The city offers different challenges than Waymo's existing deployments. More hills. Different traffic patterns. Different weather patterns, especially during winter. Different road infrastructure. All of that forces Waymo's software to adapt, to learn, to get better.

The Testing Strategy: Why Waymo Doesn't Just Deploy Everywhere

Waymo has been clear about its approach: every new city gets extensive testing before any revenue-generating rides happen. This isn't caution for caution's sake. It's engineering discipline.

The process usually works like this. First, safety drivers map the area. They drive specific routes repeatedly, recording everything. That data feeds into Waymo's simulation software. The company runs hundreds of thousands of virtual miles, stress-testing their system against the patterns they've recorded. They identify edge cases. They find scenarios where the software gets confused.

Then they update. They refine. They push new code to the testing fleet. Real-world testing resumes. They measure performance against their own benchmarks. They look for safety issues, regulatory problems, operational headaches.

Only when all of that is satisfied do they move to driverless testing. That's what just happened in Nashville. The company spent enough time in the test phase that they felt confident removing the safety driver.

But here's where it gets interesting: Waymo still hasn't announced when paid rides will actually start in Nashville. They've said "sometime in 2025." That could mean February. It could mean December. They're not rushing. They're going to wait until they're sure the system is working, that they understand the edge cases, that they can operate at scale without constant intervention.

This approach is completely different from how traditional ride-sharing companies launched. Uber and Lyft threw their apps into new cities, let real drivers figure it out, and cleaned up problems afterward. Waymo is doing the opposite. Test first. Perfect second. Revenue third.

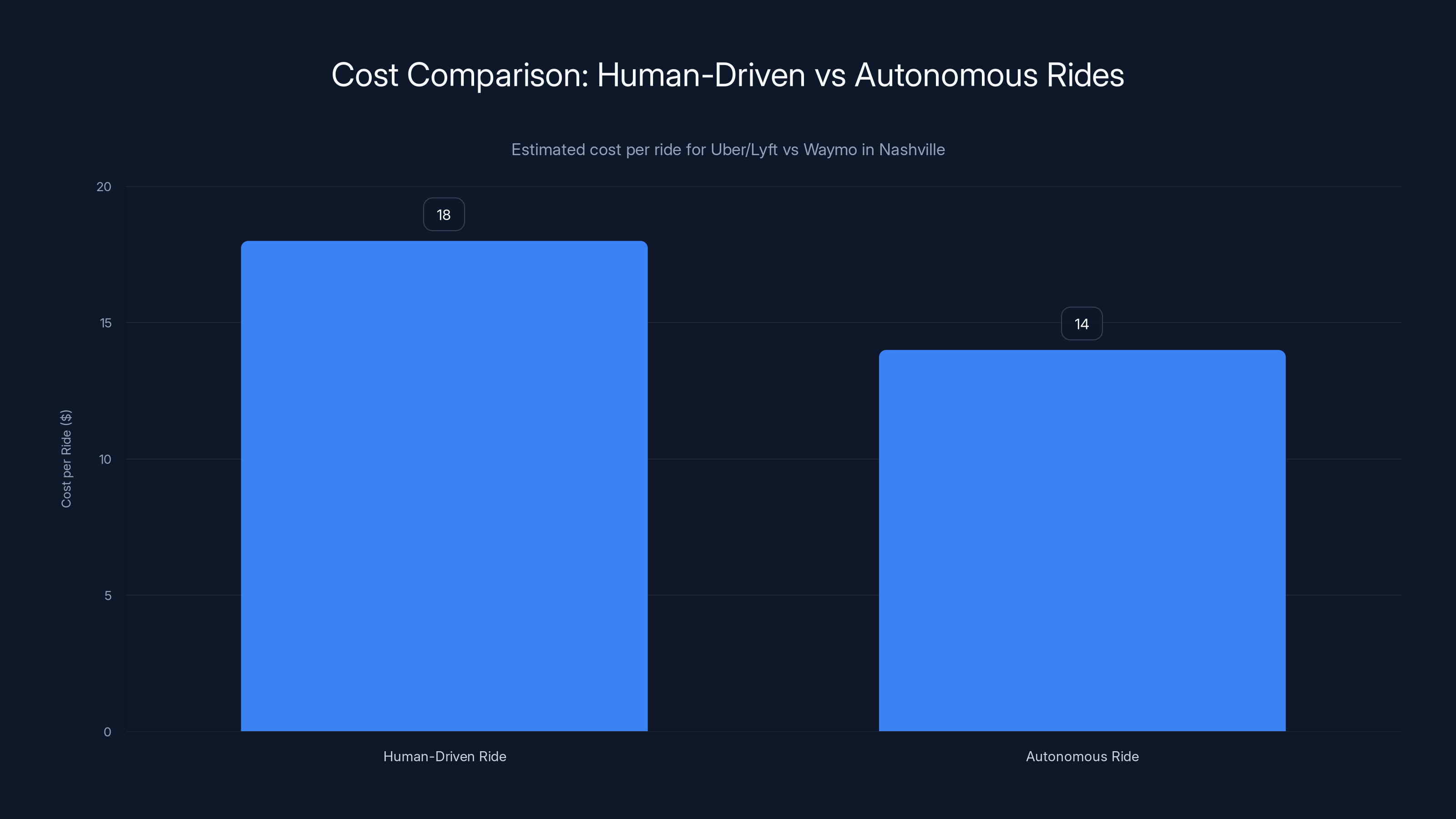

Waymo's autonomous rides are estimated to be 20-30% cheaper than human-driven rides, offering a competitive edge in Nashville's ride-hailing market. Estimated data.

Safety Record: The Recalls That Matter

Waymo's safety record is genuinely complicated. On one hand, their vehicles have driven millions of miles in testing with relatively few significant incidents. On the other hand, they've had to issue multiple recalls for problems that should frankly be embarrassing for a company claiming to build self-driving cars.

The most recent recall, which happened before the Nashville driverless rollout, was particularly telling. Waymo's vehicles were failing to stop for school buses. Not occasionally. Systematically. The software wasn't reliably detecting school buses with their lights flashing, which is literally the most important safety scenario for any driving system in America.

Before that, Waymo had to deal with vehicles hitting stationary objects. Gates. Chains. Telephone poles. Parked cars. These aren't edge cases. They're core driving scenarios. The fact that Waymo's vehicles struggled with them, then had to issue software recalls to fix them, tells you something important: autonomous driving is harder than it looks.

But here's the thing that gets lost in the criticism: every one of those recalls was caught and fixed before causing serious injury. Waymo's system identified the problems, the company issued updates, and the vehicles got better. That's exactly how safety improvements should work.

Compare that to traditional cars. A typical car has a critical flaw? Maybe a few people die before it becomes a news story. Maybe the NHTSA investigates. Maybe there's a recall. Waymo's approach is different: catch the problem, fix it, deploy the fix, improve the system. Over and over again until it works.

The reality is that Waymo's vehicles are probably safer than human drivers at this point. The data suggests that autonomous vehicles cause fewer accidents per mile than humans do. But "safer than human drivers" sets a pretty low bar. Humans are terrible at driving. We're distracted, tired, emotional, and we drive 4,000-pound metal boxes at 70 miles per hour while texting.

What matters more is whether Waymo's vehicles are safe enough that regulators are comfortable with them operating without safety drivers in cities. Apparently, they are. Nashville is proof of that.

How Nashville is Different From Waymo's Other Testing Cities

Waymo's existing autonomous operations are clustered in the Southwest and Southeast. Phoenix, where Waymo has been testing for years, is mostly sprawl with predictable weather. San Francisco and Los Angeles offer dense urban environments with complex traffic patterns, but they're cities Waymo has spent enormous amounts of time studying.

Nashville presents a genuinely different set of challenges. The city sits on the Cumberland River in a hilly area. That terrain matters for autonomous vehicle sensors and software. The winter weather is inconsistent. Sometimes it snows. Sometimes it rains. Sometimes it's 65 degrees and sunny. That variation forces Waymo's system to adapt in ways that Phoenix's consistent desert climate never required.

The traffic patterns are different too. Nashville is a tourist city with significant seasonal variations. Country Music Festival, CMA Awards, major sporting events. The city swells with visitors during certain times of year, then empties out. Traffic patterns that apply in July don't apply in April. Waymo's software has to learn and adapt to that variation.

The road infrastructure is different as well. Nashville has a mix of older roads and newer ones. Some streets are genuinely weird from an autonomous vehicle perspective. The city has more inconsistent traffic signaling than some of Waymo's other testing areas. There are higher numbers of jaywalkers and unpredictable pedestrians.

All of that means Waymo's Nashville deployment isn't just a copy-paste from their Phoenix or San Francisco playbooks. It's a real test of whether their autonomous system is actually general enough to handle different cities. That's a crucial distinction. A self-driving car that only works in Phoenix isn't actually self-driving. A self-driving car that works in Nashville, San Francisco, Phoenix, and everywhere else? That's the real technology.

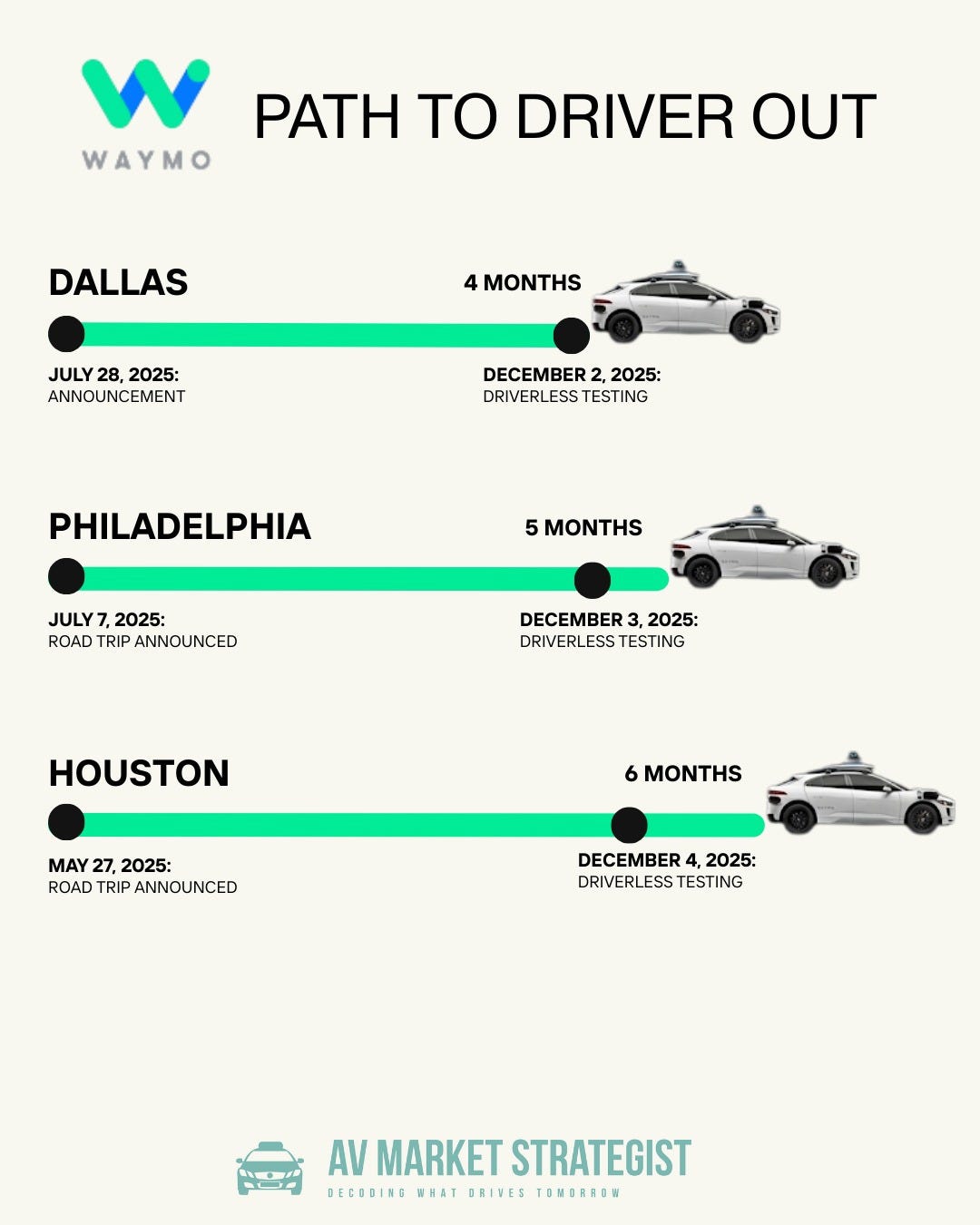

Early indications suggest Waymo's system is actually transferable. The fact that they're confident enough to remove safety drivers in Nashville after just a few months of testing suggests the software adapted quickly to the new environment. Whether that continues to be true as they expand to Boston, Dallas, Denver, Detroit, and the other cities on their roadmap will be genuinely important.

The Timeline: From Testing to Revenue

Waymo's journey in Nashville has been remarkably fast when you consider the company's typical timeline. Here's what actually happened:

September 2024 (approximately): Waymo announced plans to bring robotaxis to Nashville. The company committed to testing and eventually offering paid rides to the public.

Late 2024 to Early 2025: Safety drivers began extensive testing in Nashville. Waymo mapped routes, ran simulations, identified edge cases, and stressed the system.

Early 2025: Waymo removed safety drivers from the Nashville fleet. The company announced it was moving to fully autonomous testing.

2025: Paid rides will launch "sometime." Waymo hasn't committed to a specific date.

This timeline matters because it tells you something about how confident Waymo is in their technology and how ready Nashville is to host autonomous vehicles. The company didn't spend years testing. They moved relatively quickly. That suggests they had a solid understanding of what Nashville required based on their experience in other cities, and the Nashville environment wasn't dramatically different from what they'd already solved.

But they're also not rushing toward revenue. The paid launch is still months away, even though driverless testing has started. That's deliberate. Waymo is going to watch data. They're going to monitor how the system performs. They're going to make sure operational details are figured out. Only then will they start charging money.

Compare that to how fast companies typically try to monetize technology. Waymo's approach is almost absurdly patient. Which is probably why it's working.

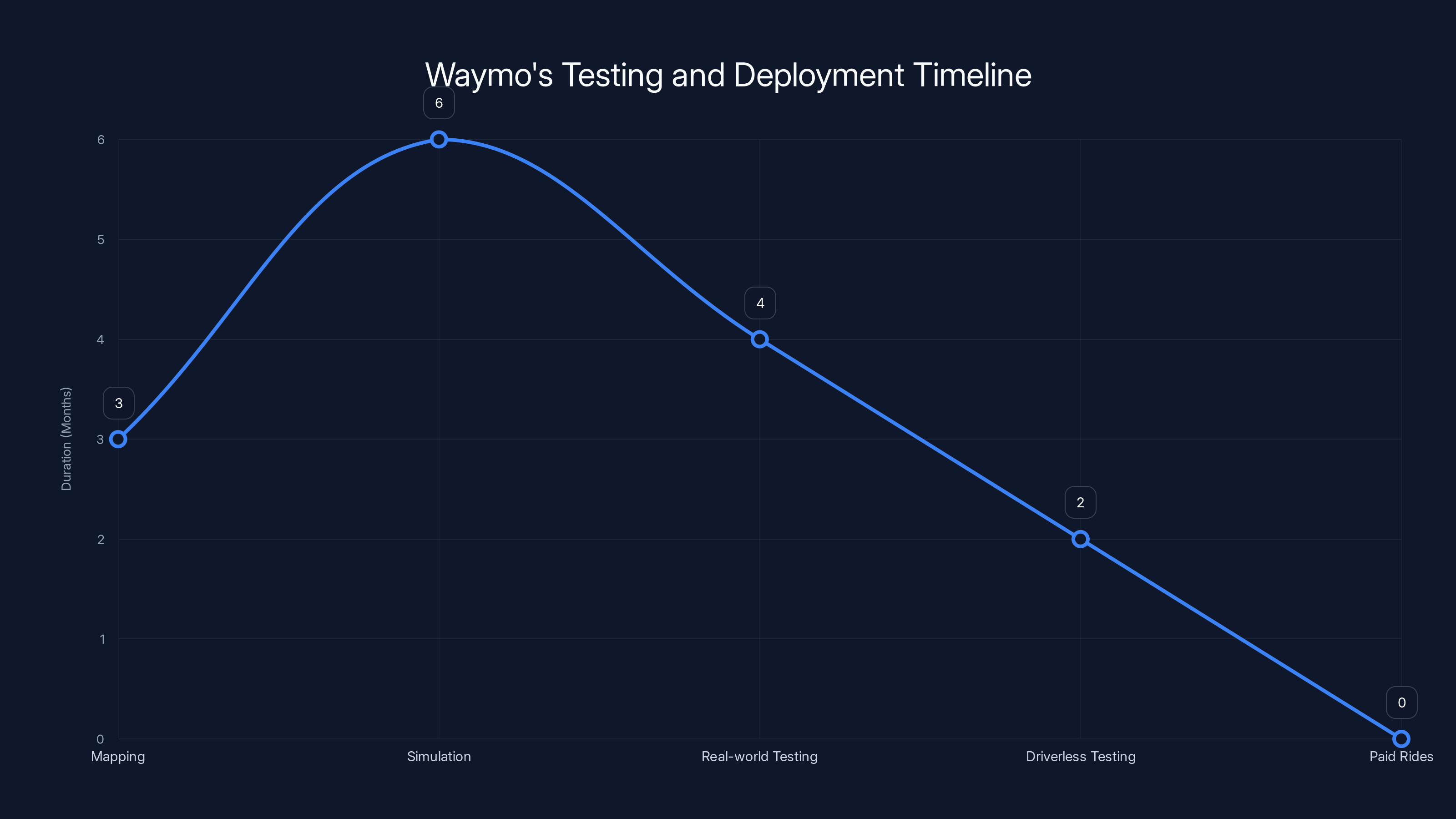

Waymo spends significant time in each testing phase before launching paid rides, emphasizing safety and system reliability. Estimated data based on typical testing processes.

Revenue Opportunity: Why Waymo Cares About Nashville

Nashville isn't Waymo's largest market. San Francisco and Phoenix are bigger, more established revenue bases. So why expand to Nashville at all? Why spend money testing there? Why not focus resources on optimizing existing deployments?

The answer is that Nashville represents something valuable that San Francisco doesn't: proof of scalability. Waymo can't build a trillion-dollar business in three cities. They need to demonstrate that their technology works everywhere. Nashville is one of many tests of that premise.

But there's also specific value in Nashville itself. The city is growing. Tennessee has favorable regulatory conditions for autonomous vehicles. The local government has been supportive. There's a significant ride-hailing market. Nashville residents currently spend money on Ubers and Lyfts every day.

Waymo sees an opportunity to capture some of that spending. If autonomous vehicles are 20 to 30% cheaper to operate than human-driven ride-sharing services, then Waymo can undercut Uber and Lyft on price while maintaining profitability. That's a compelling economic case.

The numbers are interesting. A typical Uber or Lyft driver earns roughly

Waymo's autonomous vehicles don't need wages. They don't need benefits. They don't need to be replaced constantly because drivers quit. They need maintenance, insurance, and software updates, but those costs are generally lower per mile than paying a human driver. That creates opportunity for Waymo to offer cheaper rides, capture market share, and still be profitable.

If that works in Nashville, it can work in Boston, Dallas, Denver, and two dozen other cities on Waymo's expansion roadmap. Suddenly you're looking at a transportation business that could be worth tens of billions of dollars.

That's why Nashville matters. It's a test market for a business model that could reshape how people get around cities.

Regulatory Environment: Why Regulators Are Letting This Happen

One of the biggest surprises about Waymo's autonomous vehicle success is how little regulatory friction they've encountered. Federal regulators haven't tried to shut them down. Local governments have largely been supportive. Ride-sharing regulators have adapted existing rules instead of blocking the new technology.

That's not accidental. Waymo has spent years building relationships with regulators, demonstrating safety, and proving that their technology works. They've been transparent about problems, including recalls. They've cooperated with investigations and requests for data.

Tennessee, where Nashville is located, has been particularly welcoming to autonomous vehicle testing. The state has favorable regulatory conditions and hasn't created unnecessary barriers. That's partly ideology (Republican-led states have tended to be more skeptical of heavy regulation) and partly pragmatism (states want the economic benefits that autonomous vehicle companies bring).

But the regulatory environment could change. Federal regulators could get more aggressive. Local governments could demand more safety data or more public testing time before allowing revenue-generating rides. Insurance companies could raise rates or impose stricter requirements.

Waymo is aware of all of this. They're moving deliberately partly because they're confident in their technology, but also because they want to demonstrate safety and reliability to regulators before those rules potentially get stricter. Better to show regulators you're safe now, when they're inclined to be permissive, than to get caught in a more restrictive regulatory environment later.

Competition: Who Else is Building Autonomous Vehicles

Waymo's Nashville deployment isn't happening in a vacuum. Multiple companies are racing to deploy autonomous vehicles, and some of them are taking radically different approaches.

Tesla is the obvious competitor. Elon Musk has been promising full self-driving capability for years. Tesla's approach is fundamentally different from Waymo's. Waymo uses lidar, radar, and cameras redundantly. Tesla uses only cameras and neural networks, betting that computer vision alone is sufficient. That's a riskier bet, but if it works, it's cheaper to deploy.

Tesla's Full Self-Driving beta is available to some drivers today, but it's not truly autonomous. A human needs to supervise. The system still makes mistakes. But Tesla has a massive distribution advantage: millions of cars on the road that can potentially receive autonomous driving features. Waymo has thousands of purpose-built vehicles.

Apple spent billions developing autonomous vehicle technology before reportedly shelving the full robotaxi program, though rumors suggest they're continuing development in some form. If Apple enters the market, they bring brand trust, distribution through their ecosystem, and massive capital.

Other players include Cruise (formerly a General Motors subsidiary), which operates autonomous vehicles in San Francisco but has faced more regulatory hurdles than Waymo. Aurora, which is building autonomous technology for trucks. Mobileye, which is developing autonomous systems for traditional automakers. And various startups trying different technical approaches.

Waymo's advantage is that they're first to scale beyond single-city deployments. They have genuine operating experience across multiple cities. They've dealt with different regulatory environments, different weather, different traffic patterns. That experience is valuable and hard to replicate.

But competition is intensifying. Over the next five years, you'll probably see multiple companies operating autonomous vehicles in major American cities. That competition will drive prices down, improve service quality, and accelerate adoption. Waymo's Nashville move is partly about being first to capture market share before competition gets serious.

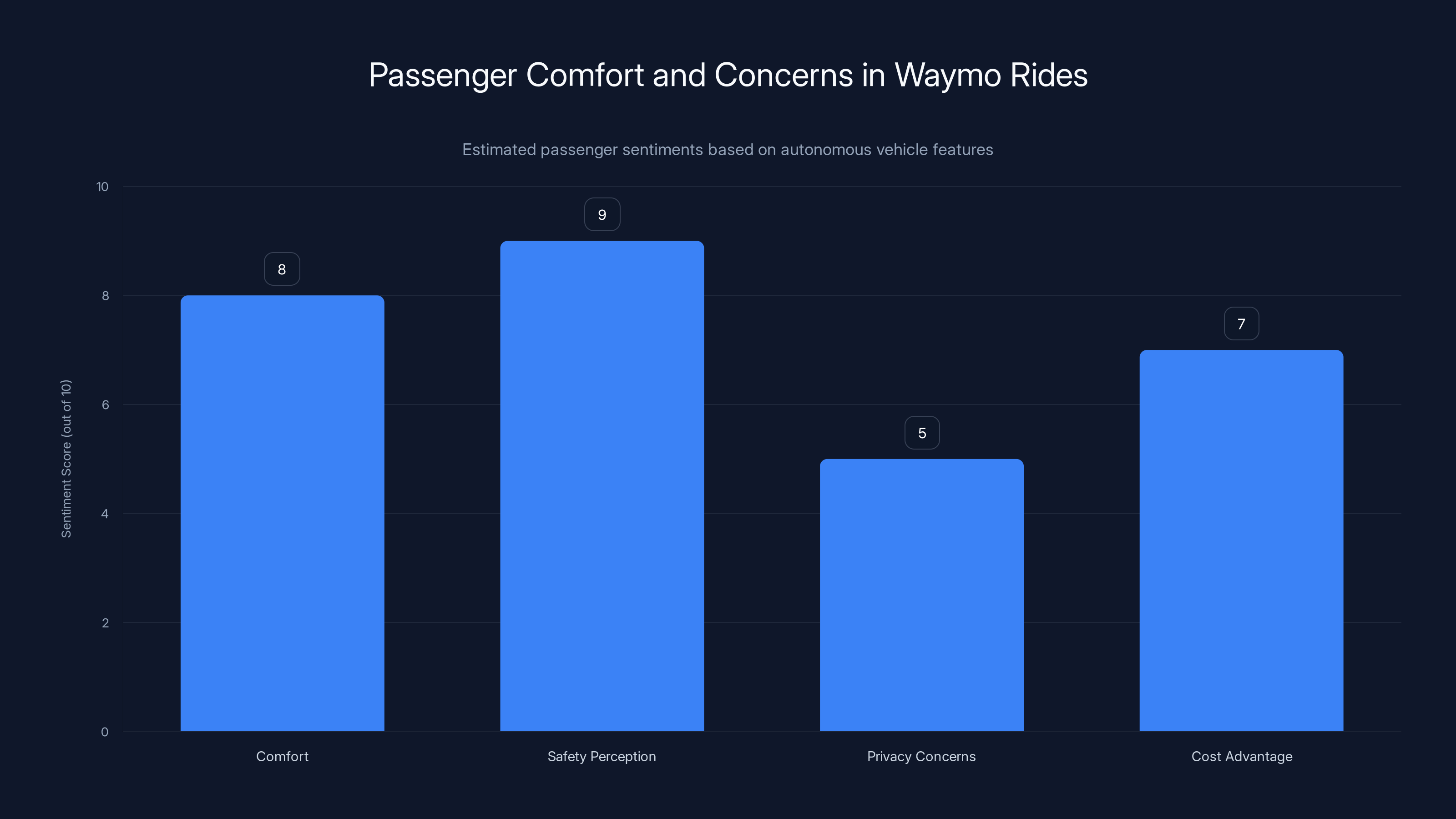

Estimated data suggests passengers find Waymo rides comfortable and perceive them as safe, though privacy concerns are moderate. Cost advantage is notable if prices are competitive.

Technical Deep Dive: How Waymo's Autonomous System Actually Works

Understanding Waymo's technology requires understanding what autonomous driving actually requires. It's not a single sensor or a single algorithm. It's a complex system of overlapping capabilities that all need to work together reliably.

Start with perception. Waymo's vehicles use lidar, which stands for light detection and ranging. Essentially, the car shoots laser pulses in all directions and measures how long they take to bounce back. That creates a 3D map of everything around the vehicle with incredible precision. Lidar can see in darkness, in rain, in fog. It's fundamentally more reliable than cameras for mapping physical space.

But lidar has limitations. It's expensive (though prices are coming down). It has limited range. And it doesn't tell you what things are. Is that a person? A dog? A plastic bag? Lidar just sees objects.

That's where cameras come in. Waymo's vehicles have cameras pointing in all directions, constantly recording video. Computer vision algorithms look at that video and identify what's happening. That's a person crossing the street. That's a stop sign. That's a road construction zone. The algorithms then combine the lidar data (precise 3D location) with the camera data (semantic understanding of what things are) to build a comprehensive model of the driving environment.

Radar adds another layer. It works through rain and darkness where cameras struggle. It's good at measuring velocity. If something is moving toward the car, radar will detect that clearly. Waymo uses radar as a third layer of redundancy.

Now you have perception: the car understands what's around it. Next comes prediction. Based on what's currently happening, what's likely to happen next? If a pedestrian is walking toward the street, they might cross in front of the car. The autonomous system predicts that and prepares to brake. If a car two vehicles ahead has its brake lights lit, the system predicts that the vehicle in front will slow down and plans accordingly.

Prediction is genuinely hard. It requires modeling human behavior and traffic patterns. But Waymo's system has learned from millions of miles of test data. The algorithms have seen thousands of variations of "pedestrian approaching intersection." They've learned what usually happens and can predict with reasonable accuracy.

Finally, there's planning and control. The system decides what to do. Go faster, go slower, brake, turn, wait. It controls the accelerator, the brake, and the steering. All of this happens in real time, dozens of times per second.

The reason Waymo can operate without a safety driver is that all of these systems are good enough. Not perfect. But good enough that the car rarely encounters situations it doesn't know how to handle.

Waymo's software runs on purpose-built hardware. The company doesn't use consumer GPUs. They've built custom silicon optimized for the specific computations that autonomous driving requires. That hardware costs money, which is one reason Waymo's vehicles are expensive compared to a regular car with Uber's driver installed.

Safety Considerations: What Could Still Go Wrong

Even though Waymo's system is genuinely sophisticated, it's not perfect. There are categories of problems that autonomous systems still struggle with.

Weather is one. Heavy snow or fog can degrade sensor performance. Lidar beams scatter in fog. Cameras can't see through heavy snow. Roads become less visible. Waymo's system handles rain and light snow, but blizzard conditions are genuinely problematic for all autonomous vehicles currently deployed.

Malicious actors are another. Someone could spray paint cameras, throw dirt on lidar windows, or place objects intentionally to confuse sensors. Waymo's system is somewhat robust to these attacks, but determined adversaries could probably cause problems.

Edge cases are the third category. Situations that the training data didn't include, that the algorithms have never seen before. A person in a costume. An unusual traffic pattern caused by an accident. A road configuration that's slightly different than expected. Autonomous systems sometimes struggle with edge cases because they're extrapolating beyond their training data.

Software bugs are always possible. Despite extensive testing, bugs can slip through. There could be edge cases where the system behaves unexpectedly. That's why companies like Waymo test in simulation for hundreds of millions of miles: to catch those bugs before they happen on real roads.

But the most important thing to understand is that Waymo's system doesn't need to be perfect. It needs to be good enough. Better than human drivers, or at least comparable. The data suggests they've achieved that. Which is why Nashville is letting them operate without safety drivers.

The Expansion Roadmap: Where Waymo Goes Next

Waymo has publicly committed to expanding autonomous vehicle services to numerous cities. The confirmed list includes Boston, Dallas, Denver, Detroit, Houston, Las Vegas, Orlando, Sacramento, San Antonio, San Diego, Washington DC, and London in the UK.

That's an ambitious roadmap. Each city represents a different technical and regulatory challenge. But Waymo has demonstrated they can figure out those challenges. Nashville is just the latest example.

The expansion strategy appears to be geographic clustering initially. Get solid coverage of major metropolitan areas in the US, then expand internationally. London is the one international deployment so far, which is a test of whether Waymo's technology works with left-hand traffic and British road infrastructure.

Over the next five years, you'll probably see Waymo operating in 15-20 major cities globally. That would create a significant network of autonomous ride-sharing services. Not universal coverage, but enough that it genuinely changes how people get around in those cities.

The economic opportunity is enormous. If autonomous vehicles capture even 10% of the ride-hailing market globally, that's tens of billions of dollars in annual revenue. The market is large enough that multiple companies can succeed. Waymo won't be alone. But being first to scale matters. First-mover advantage in a market this large compounds over time.

Ride-hailing is projected to be Waymo's primary revenue driver, contributing an estimated 60% of total revenue. Other streams like technology licensing and partner services also play significant roles. Estimated data.

Passenger Experience: What Will Riding in a Waymo Actually Feel Like

When Waymo launches paid rides in Nashville, what will the experience actually be like? That's the question most people care about.

First, there's the mental adjustment of not having a driver. For some people, that's exciting. For others, it's unsettling. Riding in a fully autonomous vehicle feels different psychologically than riding with a human driver present, even if technically it's safer.

The ride itself is smooth. Waymo's vehicles are programmed to drive conservatively. They don't accelerate aggressively or brake hard unless absolutely necessary. Many passengers find the experience more comfortable than riding with an aggressive human driver, but less sporty. It's like riding with your grandmother: safe, smooth, maybe a little slower than you'd like.

Security and privacy are considerations. There are cameras in the vehicle recording the ride. Waymo claims they don't store the video, but passengers need to trust that. Some people will be uncomfortable with that level of surveillance. Others won't care.

Cost is the big question. Waymo hasn't announced Nashville pricing, but their existing markets suggest rides will be competitive with or cheaper than Uber and Lyft. If they can undercut ride-hailing prices by 20-30% while still being profitable, that's a massive competitive advantage.

Practical logistics: you'll use an app to request a ride, just like Uber. A car will show up without a driver. You'll get in, punch in your destination (or it will be pre-loaded from the app), and the car will take you there. No tipping required. No small talk. Just point A to point B.

The experience won't be revolutionary. It'll feel normal. Which is exactly the point. Autonomy should be boring. Transparent. Just a different way to get where you're going.

The Insurance Question: Who's Liable if Something Goes Wrong

One of the thorniest problems with autonomous vehicles is insurance and liability. If an autonomous vehicle hits someone, who's responsible? The car company? The software? The passenger inside?

Traditionally, the driver is responsible. But with autonomous vehicles, there's no driver (or the driver isn't driving). So liability shifts. Insurance regulators have been working on this for years. Most states have concluded that the autonomous vehicle company is primarily liable, similar to how the manufacturer of a traditional car is liable for defects.

Waymo presumably has comprehensive insurance for their autonomous vehicles. They're operating under the assumption that their cars will cause accidents (anything can cause accidents), and they'll need to cover the legal and medical costs when that happens.

From a passenger perspective, riding in a Waymo is probably less legally risky than riding with an Uber driver who might not have adequate insurance. Waymo definitely has insurance. They've structured themselves to be liable. They're financially capable of paying claims.

But the insurance question is still being worked out. There's no long-term data on how insurance companies will price autonomous vehicle coverage. There's no settled case law on liability in complex scenarios (was it the passenger's fault? The manufacturer's? The infrastructure's?). Over time, as autonomous vehicles become more common, these questions will get clearer.

For Nashville, Waymo presumably has insurance that covers their operations. The regulators who approved driverless testing checked that presumably. The legal framework is messy, but it's not a blocker for deployment.

Public Perception: How Nashville Residents are Reacting

Waymo's success with autonomous vehicles isn't just about technology. It's about public acceptance. People need to trust the technology enough to get in the car and trust that they'll arrive safely.

Public perception data suggests that acceptance of autonomous vehicles is growing, but there's still skepticism. People are generally more comfortable with autonomous vehicles on highways (which are simpler, more predictable) than in city streets. Nashville testing and eventually rides will test whether that skepticism breaks down when people actually experience the technology.

Early adopters will be the initial passengers. People who follow tech closely, who are curious about new things, who are willing to be the test case. Over time, as they report positive experiences, more mainstream customers will try the service.

But there will definitely be detractors. People will worry about safety. Some will see driverless cars as job-threatening (they are, at least for professional drivers). Some will just prefer human interaction and conversation with a driver.

Waymo's advantage is that they're being transparent. They're not hiding their technology or their failures. They publicize recalls. They share safety data. They work with regulators openly. That transparency builds trust. Not universal trust (some people will never be comfortable), but enough that most people are willing to try the service.

Nashville will be a real test of whether that works at scale. San Francisco and Phoenix are tech-forward cities where people expect innovation. Nashville is more mainstream. If Waymo can succeed there, it suggests autonomous vehicles can succeed in less tech-forward markets too.

Waymo plans to expand its autonomous vehicle services to 15-20 cities globally by 2028. This expansion will significantly impact urban transportation in these areas. (Estimated data)

The Bigger Picture: Autonomous Vehicles and Urban Transportation

Waymo's Nashville deployment is significant, but it's part of a much larger transformation in how cities work. Over the next decade, autonomous vehicles will probably reshape urban transportation entirely.

The current system is based on personal vehicle ownership. You buy a car, park it (taking up space most of the time), drive it yourself. That's inefficient. A typical car is parked 95% of the time. It requires insurance, maintenance, registration, parking. It causes traffic, pollution, accidents.

Autonomous ride-hailing offers a different model. Fewer cars on the road, but they're always in use. Shared, not owned. Cheaper per trip because there's no driver to pay. Safer because machines don't get distracted.

If autonomous vehicles become the default way people get around cities, parking lots will disappear. Traffic will decrease. Accident rates will plummet. Pollution will drop. Cities could be fundamentally more livable.

Waymo is betting that Nashville is one step toward that future. Not the whole future, but a genuine proof of concept. If they can prove autonomous ride-hailing works in a mid-sized American city with normal traffic and weather, then the path to widespread adoption gets clearer.

That future isn't inevitable. There are regulatory, technical, and social hurdles. But Waymo's success in Nashville suggests those hurdles are surmountable.

Waymo's Business Model: How They'll Make Money

Waymo's revenue model is straightforward: charge for rides. Similar to Uber, but without the driver cost. That should make the business more profitable than traditional ride-hailing, assuming they capture enough volume.

But Waymo's journey to profitability has been long and expensive. The company has been burning cash for over a decade. Alphabet (Google's parent) has been funding the development. At some point, Waymo needs to prove it can be a standalone business that's actually profitable.

Nashville is a test of that. Can they launch a revenue-generating service, keep costs low enough, and attract enough customers that they actually make money?

Other revenue opportunities exist. Waymo could license their technology to automakers. They could operate autonomous ride-hailing services under partner brands. They could sell data about driving patterns to city planners. But ride-hailing is almost certainly the primary revenue driver.

The unit economics are roughly this: a Waymo vehicle costs more than a regular car (all that sensor hardware is expensive, maybe

If Waymo can achieve unit profitability (make more money per mile than they spend), then fleet growth becomes purely a capital allocation question. Profitability is what separates viable businesses from vaporware.

Nashville will show whether Waymo can actually achieve that. Not immediately, but over the next 12-24 months as the service scales up and they collect real operational data.

Remaining Challenges: What Could Derail Autonomous Vehicles

Despite Waymo's progress, significant challenges remain. Acknowledging them is important.

Scale is the first. Operating in three cities with driverless service is different from operating in thirty. Software issues might emerge only after millions of miles in diverse cities. Customer service at scale is harder than in limited deployments. Supply chain problems for vehicle hardware become bigger. As Waymo scales, new problems will emerge.

Regulatory backlash is possible. A serious accident involving an autonomous vehicle could trigger regulatory crackdowns. Drivers' unions could lobby for restrictions on autonomous vehicles. Conservative politicians might see opportunity in blocking a technology associated with Silicon Valley.

Competition could get serious. If Tesla figures out camera-only autonomous driving and deploys it at massive scale, or if Apple enters the market with a trusted brand, Waymo's advantage erodes. Market saturation could happen faster than expected, compressing margins.

Technical limitations might not be as surmountable as Waymo believes. Maybe 90% of driving scenarios can be handled by current technology, but the last 10% is genuinely hard. In that case, autonomous vehicles could plateau at current capabilities instead of achieving true full autonomy.

Public acceptance might not materialize. Maybe people prefer human drivers for reasons psychological and economic. Maybe job losses from driver displacement trigger political opposition.

None of these challenges are certain. But all of them are possible. Waymo's Nashville deployment addresses some of them. It doesn't eliminate any.

Looking Ahead: What's Next for Autonomous Vehicles

Assuming Waymo continues to execute well, what's the trajectory for autonomous vehicles over the next five to ten years?

Short term (next 12-24 months): Waymo and competitors launch paid services in 10-15 major cities. Early adopters use the service, report positive experiences, and word of mouth grows. Market share of ride-hailing shifts gradually from Uber/Lyft to autonomous options. Prices drop as competition intensifies.

Medium term (2-5 years): Autonomous ride-hailing becomes normalized in major cities. A significant portion of urban mobility shifts away from personal vehicles toward shared autonomous services. Pricing reaches parity with or undercuts Uber. Some traditional ride-sharing drivers transition to other work or exit the industry.

Long term (5+ years): Autonomous vehicles become the default in urban areas where they're deployed. Personal car ownership for city dwellers becomes less common. Traffic patterns change significantly. Parking availability increases as demand decreases. Insurance industry restructures around autonomous vehicles instead of human drivers.

That's the optimistic case. The pessimistic case is much slower adoption, technical limitations that prevent full autonomy, regulatory restrictions that limit deployment, and autonomous vehicles remaining a niche service.

Reality will probably be somewhere in between. Waymo's Nashville deployment is evidence that the optimistic case is plausible. It's not certain. But it's plausible. And that matters.

FAQ

What does it mean that Waymo removed safety drivers from Nashville vehicles?

Removing safety drivers means Waymo's autonomous system is operating without a human backup present in the vehicle. It's proof that the company is confident enough in their technology that they're willing to let it operate unsupervised. This doesn't mean the cars are perfect or that nothing could go wrong. It means the system is reliable enough for the company to take the liability risk of operating fully autonomous vehicles in a real city.

How long will Waymo test in Nashville before launching paid rides?

Waymo hasn't specified an exact timeline, saying only that paid rides will launch "sometime in 2025." The company is watching performance data, monitoring safety metrics, and ensuring operational details are figured out. Based on their approach in other cities, the driverless testing phase typically lasts weeks to months before revenue service begins, but Waymo prioritizes safety over speed.

Where can I actually use Waymo's autonomous ride-hailing service right now?

As of early 2025, Waymo operates driverless ride-hailing services in San Francisco, Los Angeles, Phoenix, and Miami for fully autonomous operations. Additionally, Waymo provides autonomous rides in Atlanta and Austin through partnership with Uber. Nashville is not yet open to public rides but is expected to launch in 2025.

How does Waymo's technology detect pedestrians and avoid hitting them?

Waymo uses multiple overlapping sensors including lidar (which creates 3D maps), cameras (which provide visual identification), and radar (which works in poor visibility). Computer vision algorithms process camera data to identify pedestrians, and the autonomous system predicts likely behavior based on position and movement. The system can detect a pedestrian and brake well before a human driver could react in most scenarios.

What happens if a Waymo autonomous vehicle gets in an accident?

Waymo maintains comprehensive insurance coverage for their autonomous vehicles and is structured to be liable for accidents caused by their technology. The liability framework treats autonomous vehicle companies similarly to traditional vehicle manufacturers—responsible for defects or failures. Passengers and third parties would file claims with Waymo's insurance, just as they would with any other vehicle accident.

Why is Nashville a good test market for Waymo's expansion?

Nashville presents different challenges than Waymo's existing test cities. The city has rolling terrain, variable winter weather, inconsistent traffic patterns from seasonal tourism, and road infrastructure that differs from desert climates. Successfully deploying autonomous vehicles in Nashville demonstrates that Waymo's technology is transferable to different environments, which is crucial evidence that the system can scale to other diverse cities.

How much will Waymo rides cost compared to Uber or Lyft?

Waymo hasn't announced Nashville pricing yet. However, autonomous vehicles eliminate driver costs, which is roughly $15-20 per ride. That economic advantage suggests Waymo could undercut traditional ride-sharing on price while remaining profitable. Pricing will be competitive or cheaper than Uber and Lyft in most scenarios.

What's the difference between Waymo's approach and Tesla's Full Self-Driving?

Waymo uses redundant sensors including lidar, radar, and cameras, betting that multiple sensing systems provide safety through redundancy. Tesla uses cameras and neural networks exclusively, claiming computer vision alone is sufficient. Waymo's approach is more expensive but arguably safer. Tesla has a distribution advantage with millions of cars on the road, but Tesla's system still requires human supervision. Waymo's system in these cities is truly autonomous.

Could autonomous vehicles really eliminate traffic congestion in cities?

Potentially, yes. Autonomous vehicles could reduce traffic through more efficient routing, elimination of human driver errors that cause accidents and traffic jams, optimized traffic flow from vehicle-to-vehicle communication, and shift from personal car ownership to shared ride-hailing (fewer vehicles total). However, this assumes widespread adoption and proper urban planning. Increased autonomous vehicle availability could also encourage more driving, offsetting some benefits.

What are the main safety concerns with autonomous vehicles that still need to be addressed?

Key remaining challenges include performance in severe weather (heavy snow, dense fog), handling of edge cases and scenarios the system hasn't encountered before, cybersecurity (preventing hacking or malicious interference), potential software bugs that could cause failures, and unusual traffic situations caused by accidents or road construction. Waymo's system handles most of these adequately, but perfection isn't achievable. The goal is to be safer than human drivers, which the data suggests Waymo has achieved.

Conclusion

Waymo's removal of safety drivers from Nashville represents a genuine inflection point in autonomous vehicle development. Not because it's the first time a company has tested driverless vehicles—that's happened for years. But because it's proof that a company can take a technology from the lab, test it in a real city, and be confident enough to remove human backup systems. That confidence is earned through millions of miles of testing, iterative improvement, and careful attention to safety.

The path to this moment wasn't straight. Waymo had to deal with failures, recalls, skepticism, and genuine technical challenges. The company had to build relationships with regulators, prove their technology's reliability, and convince skeptics that autonomous driving was actually feasible. That took over a decade and billions of dollars.

But it's working. Nashville is the evidence. In a few months, residents of that city will be able to get into a car with nobody driving, punch in a destination, and arrive safely. That won't feel revolutionary. It'll feel normal. Which is exactly how transformative technology should work.

The larger implication is that we're moving past the theoretical phase of autonomous vehicles. We're into the practical phase. The question now isn't whether autonomous vehicles will work in principle. They work. The questions now are operational: Can they scale to 50 cities? Can they remain profitable? Can they maintain safety as fleet sizes grow? Can regulatory environments stay supportive as adoption expands?

Waymo's Nashville deployment is a test of all of those questions simultaneously. Early indications are positive. But the real test will be the next 12-24 months, when fully autonomous ride-hailing actually happens in a mid-sized American city with normal traffic and weather. That's when we'll learn whether Waymo's vision of autonomous transportation is actually viable at scale.

Based on what we're seeing now, I'd bet it is. Which means your transportation options are about to get a whole lot more interesting.

Key Takeaways

- Waymo achieved a major milestone by removing safety drivers from Nashville autonomous vehicles, proving their driverless technology is reliable enough for real-world operation

- The company follows a deliberate deployment strategy: extensive testing in each new city before launching paid rides, with Nashville paid service expected sometime in 2025

- Waymo's multi-sensor approach using lidar, cameras, and radar provides redundancy that has proven safer than camera-only competing systems in published safety data

- The economics strongly favor autonomous vehicles: eliminating driver costs ($15-20 per ride) enables Waymo to undercut Uber and Lyft while remaining profitable

- Nashville's expansion to 12+ additional cities through 2026 suggests autonomous ride-hailing is transitioning from niche testing to mainstream urban transportation service

Related Articles

- Waymo's $16 Billion Funding Round: The Future of Robotaxis [2025]

- Waymo's Nashville Robotaxis: The Future of Autonomous Mobility [2025]

- Waymo's $16B Funding: Inside the Robotaxi Revolution [2025]

- Waymo's $16B Funding Round: The Future of Autonomous Mobility [2025]

- How Waymo Uses AI Simulation to Handle Tornadoes, Elephants, and Edge Cases [2025]

- Waymo's Genie 3 World Model Transforms Autonomous Driving [2025]

![Waymo's Fully Driverless Vehicles in Nashville: What It Means [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/waymo-s-fully-driverless-vehicles-in-nashville-what-it-means/image-1-1770727336997.jpg)