Introduction: The Resurrection of Dojo

When Tesla quietly dismantled its Dojo supercomputer team in mid-2025, it seemed like a definitive end to the company's ambitious custom silicon project. The departure of Dojo lead Peter Bannon, followed by approximately 20 engineers who jumped ship to Density AI, left many wondering whether Tesla had finally admitted defeat in competing with Nvidia's entrenched AI infrastructure dominance.

Then, unexpectedly, Elon Musk announced something nobody saw coming: Dojo is coming back. Not as a terrestrial training platform for autonomous driving. Instead, it's being reimagined as the computational backbone for what Musk calls "space-based AI compute"—artificial intelligence infrastructure launched into orbit and powered by perpetual sunlight.

This pivot represents far more than a simple restart. It's a strategic repositioning that reveals deeper truths about the future of AI infrastructure, the geopolitics of computing power, and why some of the world's most ambitious technologists believe the next frontier for data centers isn't underground or in hyperscale facilities, but 400 kilometers above Earth's surface.

The announcement dropped on a weekend in January 2026, delivered via a post on X (formerly Twitter) where Musk simultaneously began recruiting. "If you're interested in working on what will be the highest volume chips in the world, send a note to AI_Chips@Tesla.com with 3 bullet points on the toughest technical problems you've solved." It was classic Musk: bold claim, immediate execution, public challenge to the industry.

But what does space-based AI compute actually mean? Why would Tesla pivot away from terrestrial AI infrastructure? And what technical, financial, and logistical challenges stand between concept and reality?

This article explores the full context behind this decision, examining Tesla's failed terrestrial strategy, the emergence of space-based computing as a serious contender, the engineering challenges involved, competitive dynamics, and what this means for the future of AI infrastructure globally.

TL; DR

- Dojo 3's New Mission: Tesla is restarting its abandoned Dojo 3 chip project specifically for space-based AI compute rather than terrestrial autonomous driving applications

- Strategic Pivot: The move follows five months after Tesla disbanded its original Dojo team, suggesting a fundamental rethinking of computational architecture

- Power Grid Constraints: Earth-based data centers face increasingly constrained power grids, making orbital infrastructure attractive to multiple AI leaders including Sam Altman

- Space X Advantage: Musk controls launch vehicle infrastructure through Space X, providing Tesla a significant competitive advantage over rival AI companies

- Massive Engineering Challenge: Thermal management, radiation hardening, latency optimization, and power generation in vacuum represent unprecedented technical obstacles

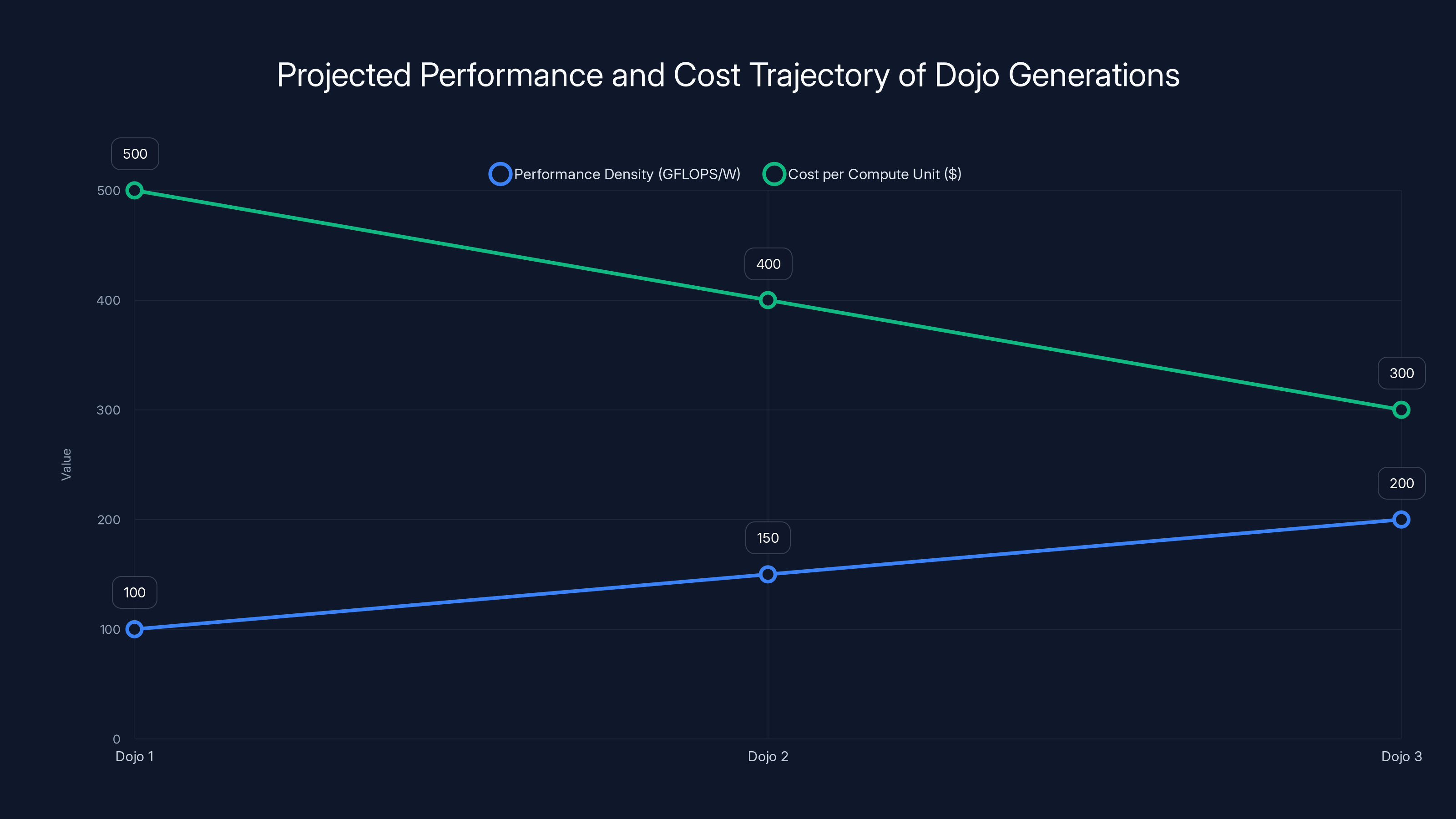

Estimated data shows that while each Dojo generation aimed to improve performance density and reduce costs, external factors like Nvidia's advancements and production complexities hindered these goals.

Why Dojo Failed Terrestrially: The Original Strategy and Its Collapse

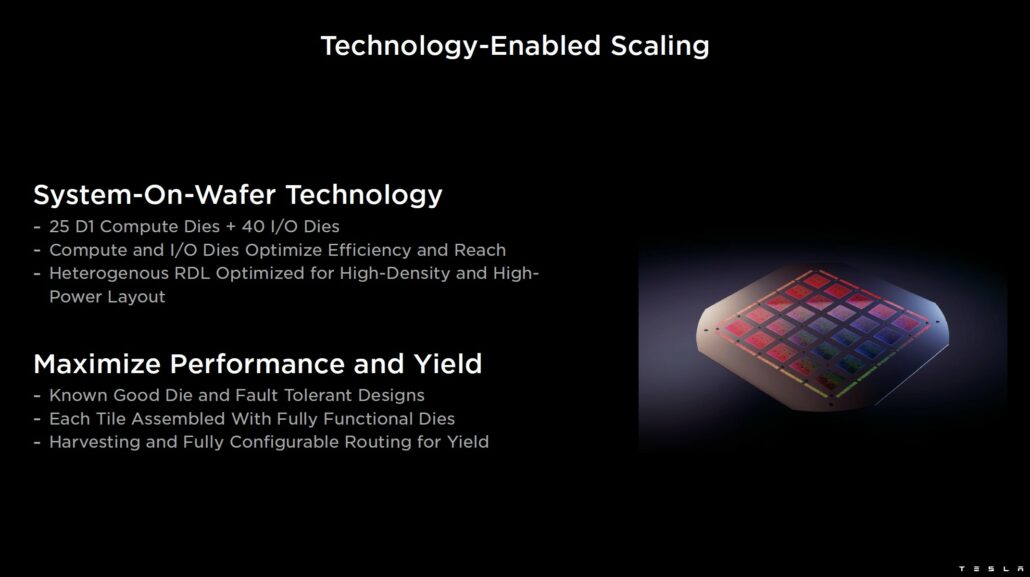

Tesla's initial Dojo vision was straightforward and ambitious: build custom silicon optimized for training deep learning models at scale, specifically targeting the computational demands of autonomous driving systems. The reasoning made sense at the time.

Nvidia dominated the market with A100 and H100 GPUs, but these chips were designed for general-purpose deep learning across thousands of applications. Tesla needed something narrower: silicon specifically engineered for the mathematical operations involved in processing camera and lidar data, predicting object trajectories, and making real-time driving decisions.

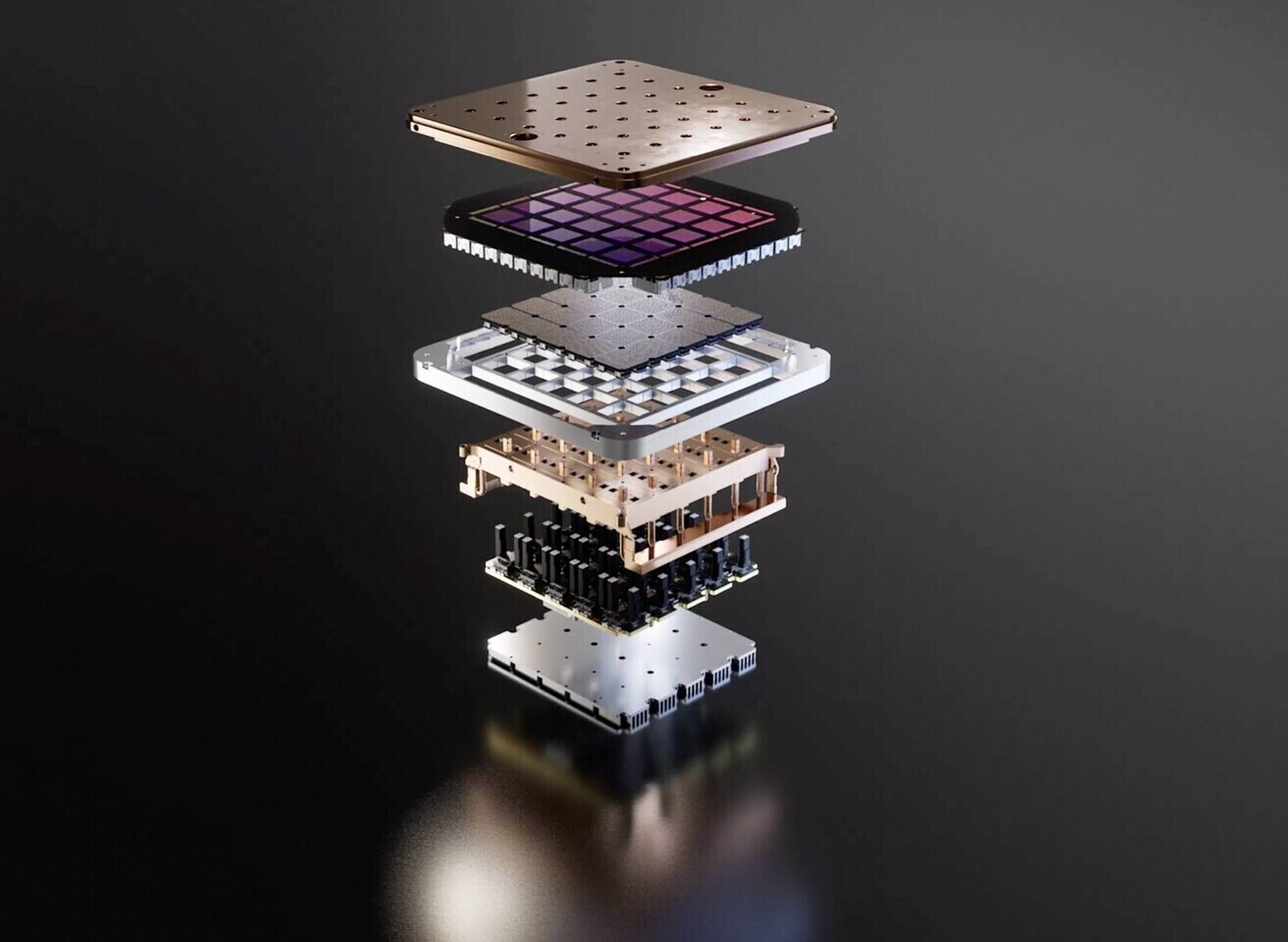

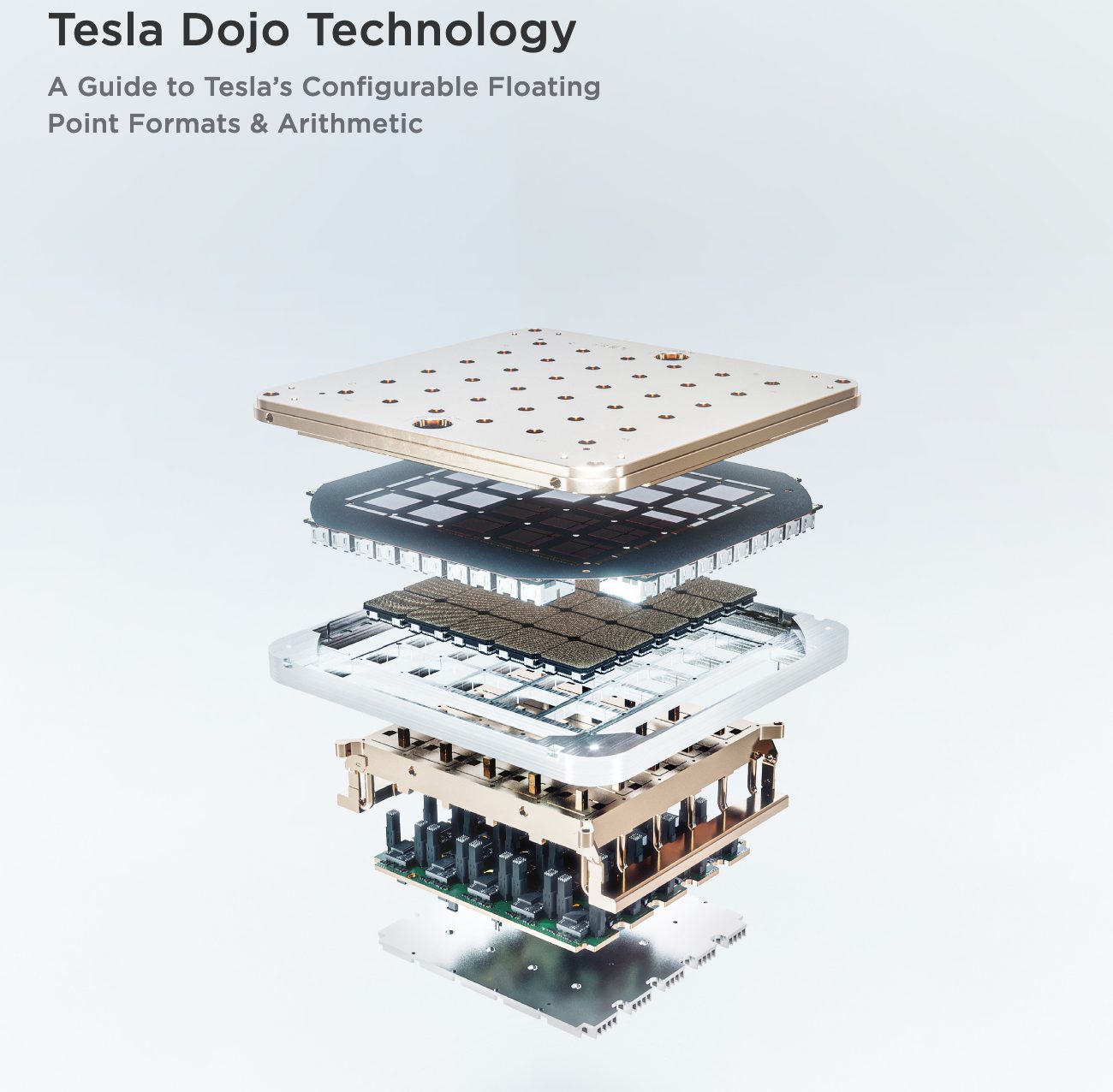

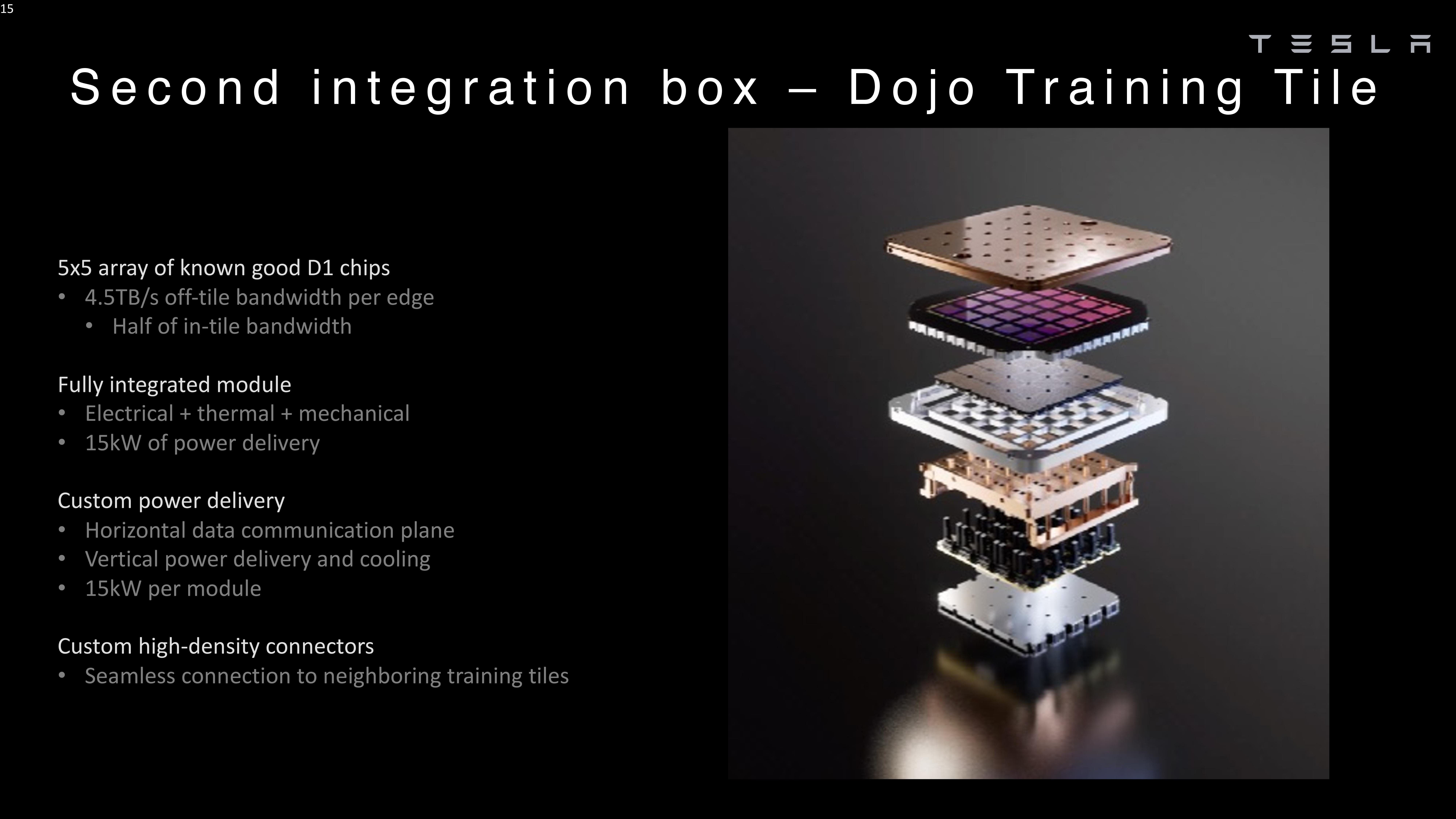

Peter Bannon led this effort with significant resources and genuine technical talent. The Dojo roadmap included three generations: Dojo 1, Dojo 2, and eventually Dojo 3. Each iteration was supposed to improve performance density, reduce power consumption, and lower costs per unit of compute.

But several factors conspired to derail the project. First, the transition from Dojo design phase to production proved far more complex and expensive than anticipated. Manufacturing partnerships with Samsung involved intricate negotiations and technical integrations that consumed far more time and capital than initial projections suggested.

Second, Nvidia kept moving the goalpost. Each new GPU generation (H100, then Blackwell) delivered surprising performance improvements, shrinking the theoretical advantage custom silicon provided. The economics of buying off-the-shelf chips—despite premium pricing—began looking more attractive than funding a multi-year custom silicon effort.

Third, talent retention became critical. The 20 engineers who departed for Density AI weren't random contractors. They represented core institutional knowledge about cache hierarchies, interconnect topology, and thermal design. Once that knowledge walked out the door, project momentum became increasingly difficult to maintain.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, the fundamental premise of Dojo began to feel outdated. Large language models emerged as the dominant paradigm for AI development, and those models train more effectively on Nvidia's tensor-optimized hardware than on silicon designed specifically for autonomous driving computations. When the entire industry pivoted toward foundation models and transformers, Dojo's specialized architecture suddenly felt like a relic.

By mid-2025, continuing the project seemed increasingly irrational. Musk approved the shutdown. Bloomberg reported that Tesla planned to expand partnerships with AMD and rely more heavily on Nvidia infrastructure, while Samsung would handle manufacturing for subsequent generation chips (AI6, AI7) without the custom design overhead.

That decision appeared final. Dojo was dead.

Then came the January 2026 announcement.

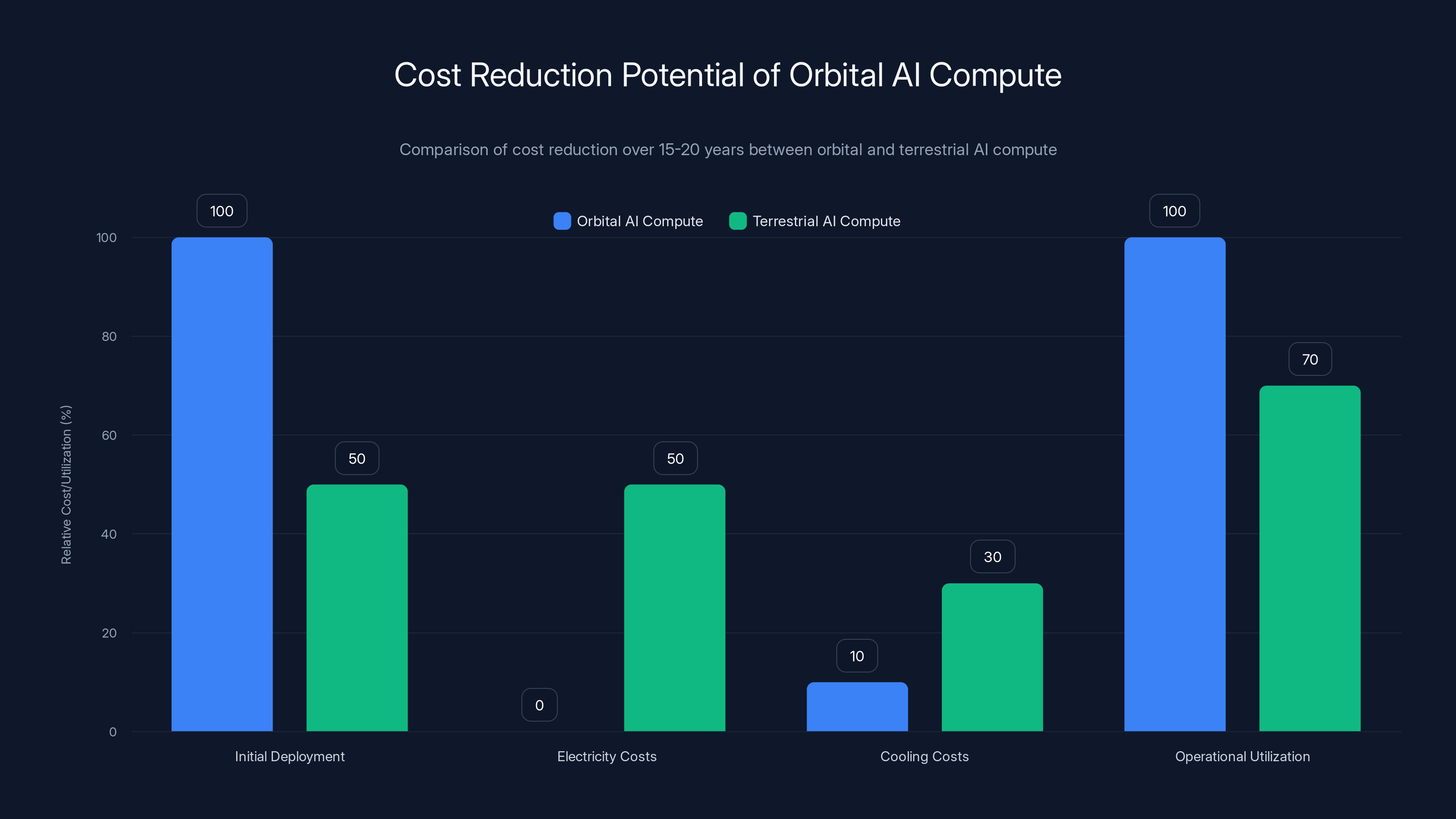

Orbital AI compute can achieve up to 30-50% cost reduction over 15-20 years due to free solar power and efficient radiative cooling, despite high initial deployment costs. Estimated data.

The Paradigm Shift: Why Space-Based AI Compute Suddenly Makes Sense

To understand why Musk resurrected Dojo for space-based applications, it's essential to understand the power crisis facing terrestrial data centers.

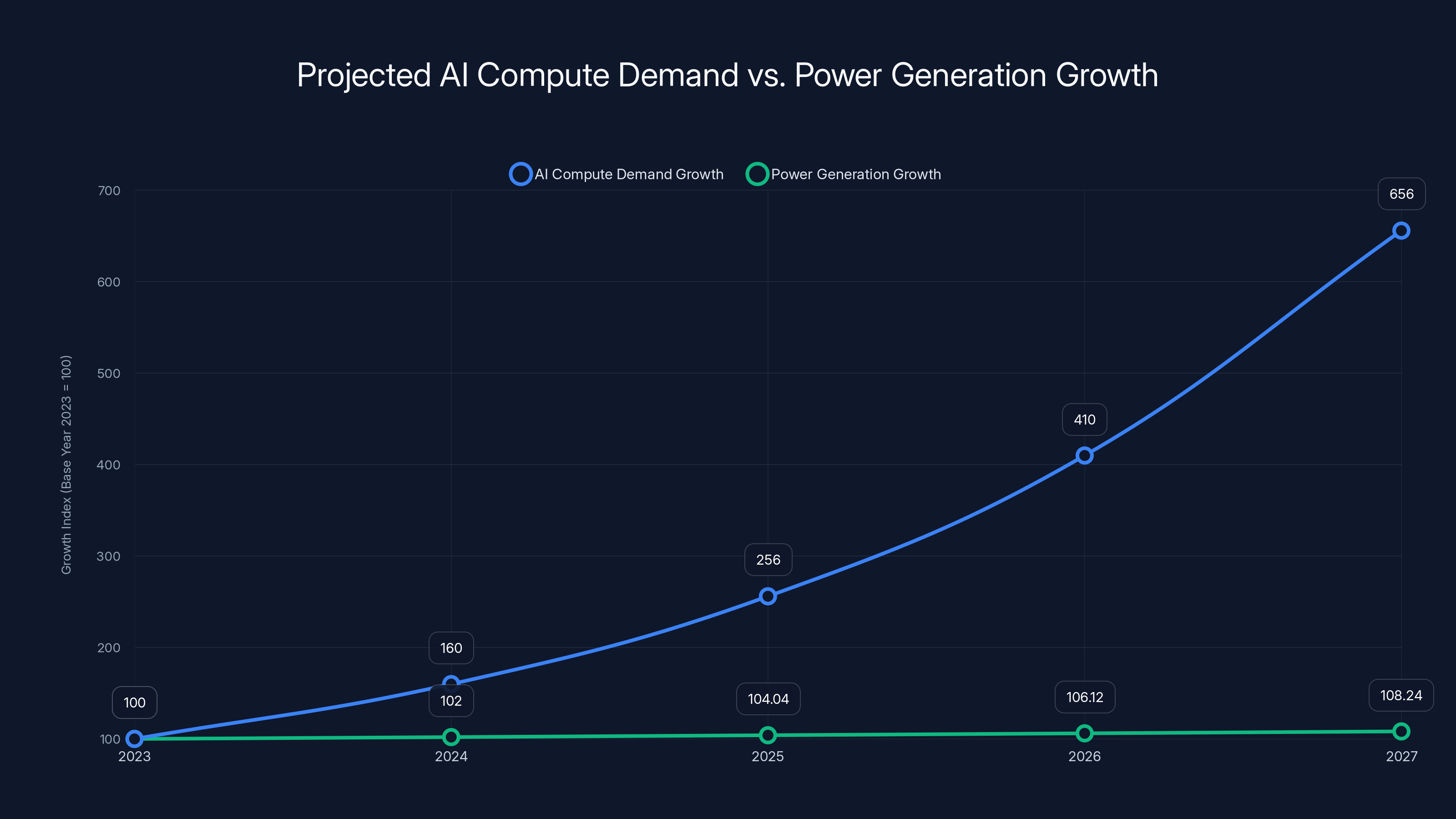

Global AI infrastructure demand is growing exponentially. Training models requires constant, enormous quantities of electricity. A single training run for a frontier model like Claude or GPT-4 consumes megawatts of power for weeks. Inference at scale across millions of users requires continuous power draw that rivals small nations.

Meanwhile, Earth's electrical grids are constrained. Utilities cannot simply build new power plants overnight. Environmental regulations restrict expansion in many regions. Nuclear is decades away from meaningful additions. Renewables are growing but face intermittency challenges.

The arithmetic becomes clear: demand for AI compute is growing at ~60% annually while power generation growth is ~2-3% annually. Within roughly five years, the limiting factor for AI development shifts from chip availability or algorithmic innovation to raw electrical power.

This is where space-based infrastructure becomes not just clever, but potentially necessary.

In orbit, solar panels receive uninterrupted sunlight 24/7 (except during brief eclipse periods). A kilowatt of solar capacity in space generates roughly 8-10x more power annually than an equivalent terrestrial installation when accounting for weather, cloud cover, day-night cycles, and seasonal variation.

Moreover, space offers unlimited "land" for expansion. You don't need planning permission. You don't compete with residential electricity needs. You don't negotiate with municipal utilities. You launch satellites, deploy massive reflective mirrors to direct sunlight onto solar arrays, and harvest power in quantities limited only by the scale of your infrastructure.

Thermally, space presents both problems and opportunities. The vacuum makes traditional air cooling impossible—waste heat cannot be dissipated through convection. But radiators pointing toward deep space can dump heat through radiation at remarkably efficient rates. Some theoretical analyses suggest space-based coolers could be more efficient than Earth-based cooling systems, particularly for extreme-density computing.

Open AI CEO Sam Altman has publicly expressed enthusiasm for orbital data centers, according to multiple industry sources. Musk possesses a unique advantage: he controls Space X, which operates the only operational heavy-lift launch vehicle in the world and is actively developing Starship, a rocket designed for ultra-high payload capacity and reusability.

Musk has explicitly stated that Space X's upcoming IPO will partially fund a constellation of compute satellites. That constellation, powered by continuous solar energy and cooled by radiation to absolute-zero space, represents the next frontier of AI infrastructure.

From this perspective, the resurrection of Dojo makes perfect sense. You can't use off-the-shelf GPUs for space-based compute in the same way you use them terrestrially. Radiation in orbit degrades semiconductor performance. Thermal constraints are different. Power distribution architecture is fundamentally different. The entire value proposition of custom silicon—optimized for a specific application domain with unique constraints—suddenly becomes compelling again.

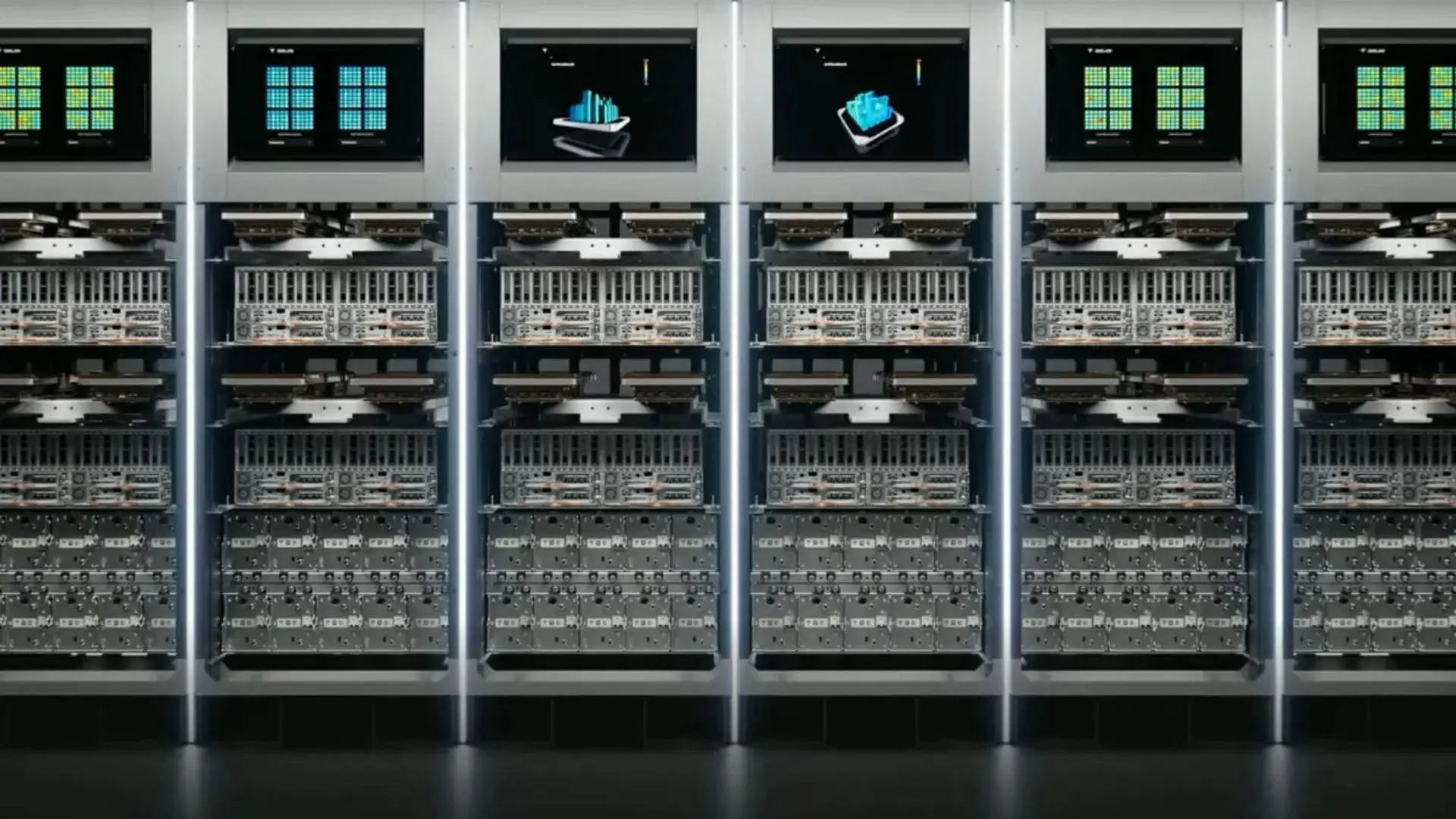

Dojo 3 isn't just about creating another chip. It's about building silicon specifically engineered for orbital operation: radiation-hardened, thermally optimized for radiative cooling, architected for power efficiency in the context of solar-powered infrastructure, and designed to operate reliably in an environment where replacement or repair is impossible for years at a time.

Understanding Space-Based AI Compute: Technical Architecture

Before exploring the challenges, let's establish how space-based AI compute would actually work.

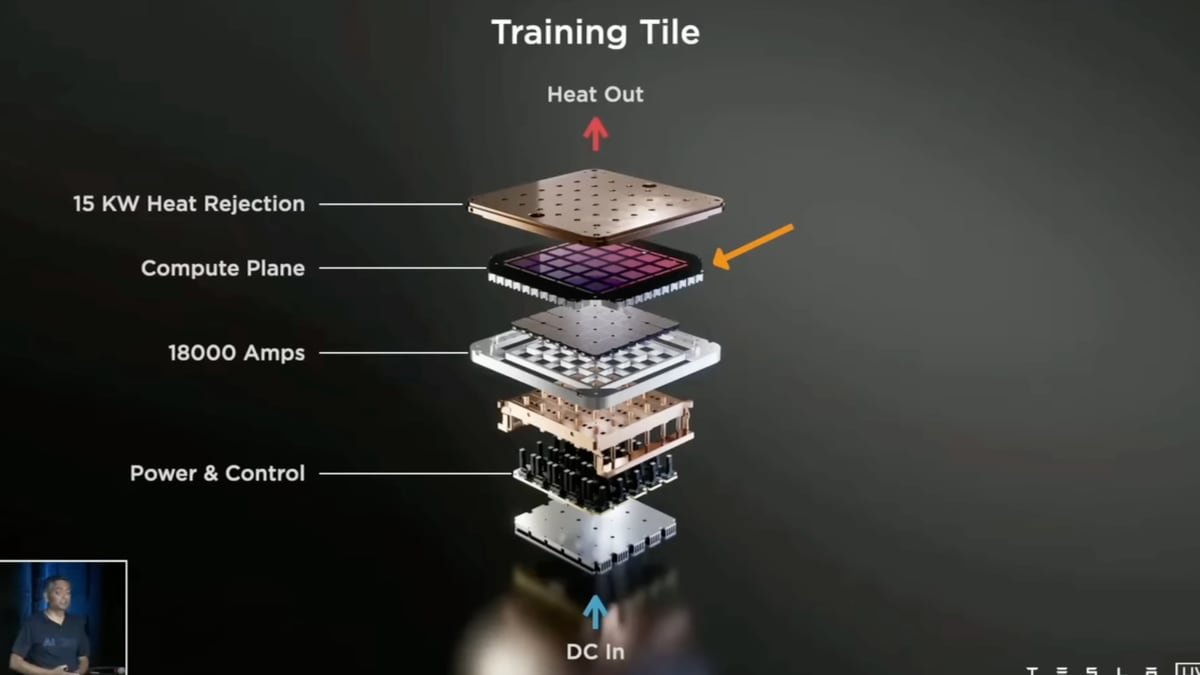

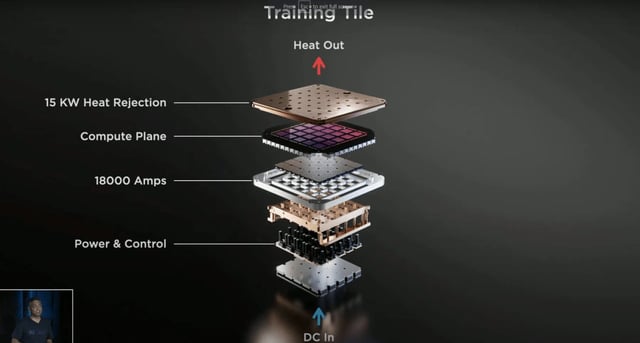

The basic architecture involves three integrated systems: solar power generation, compute infrastructure, and thermal management.

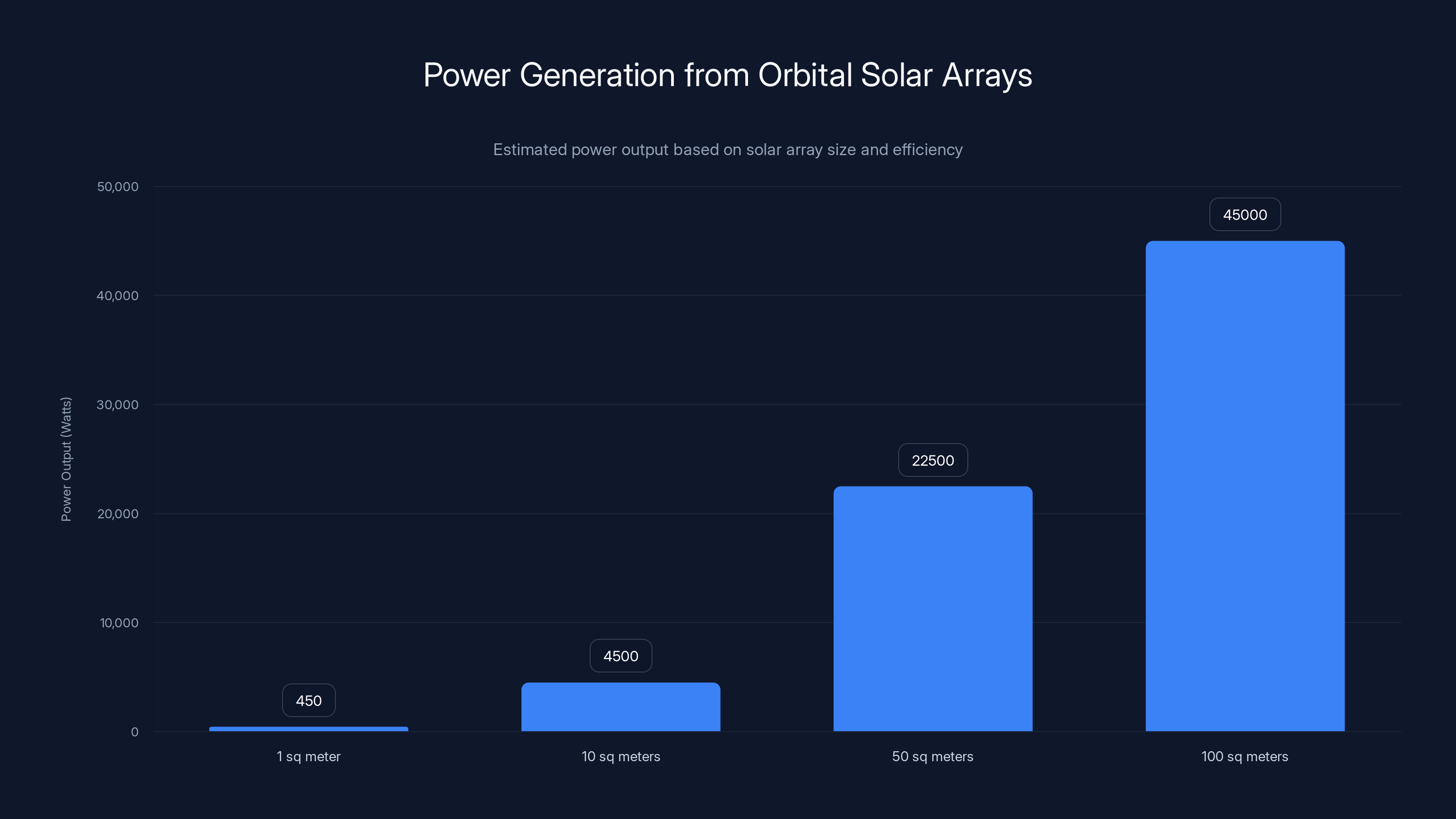

Solar Power Generation: Massive solar arrays deployed in synchronous orbit, constantly oriented toward the sun. Unlike Earth-based solar, these arrays never experience night, clouds, or weather. Theoretical power density in space reaches 1.37 kilowatts per square meter at Earth's distance from the sun (the solar constant). High-efficiency modern solar cells achieve 30-40% conversion efficiency, meaning a single square meter of orbital solar generates roughly 400-500 watts continuously.

Scaling this across multiple large satellites, you could generate gigawatts of power. A constellation of satellites each carrying 100 square meters of solar arrays could generate hundreds of megawatts continuously.

Compute Infrastructure: This is where Dojo 3 enters the picture. The actual processors need to be radiation-hardened variants of standard AI chips, or entirely custom designs. Radiation in space—cosmic rays, solar particle events, trapped radiation in the Van Allen belts—damages semiconductor junctions over time. Standard chips degrade rapidly. Space-qualified processors require redundancy, error correction, and architectural changes to handle single-event upsets (where cosmic rays flip individual bits in computations).

Tesla's custom silicon approach allows them to build processors specifically architected for these constraints. They can implement redundancy where it matters most (computation) while accepting higher risk where redundancy is cheaper (memory). They can optimize for the specific power/performance tradeoff of orbital operation: high compute density accepting higher absolute power consumption, since power is abundant from solar arrays.

Thermal Management: This represents perhaps the highest engineering challenge. Data centers on Earth reject waste heat through air conditioning—blowing cooler air through servers to cool components. In orbit, there's no air. Heat must be radiated directly to space.

Radiators work via the Stefan-Boltzmann law: radiative heat transfer is proportional to the fourth power of absolute temperature difference.

Where:

- = radiated power

- = emissivity (how well the surface radiates)

- = Stefan-Boltzmann constant (W/m²K⁴)

- = radiator surface area

- = radiator temperature

- = effective space temperature (roughly 2.7K, the cosmic microwave background)

Because space is so cold (2.7K), the temperature difference is enormous. A radiator at 350K radiating to 2.7K space achieves remarkable heat rejection per unit area compared to terrestrial cooling. Paradoxically, space might provide more efficient cooling than Earth for extreme-density computing.

But implementing this requires extensive radiator surface area, careful thermal management throughout the satellite, and redundancy to handle radiator degradation from atomic oxygen erosion and micrometeorite impacts.

Data Transmission: This is the under-discussed challenge. Processing terabytes of training data requires not just compute satellites but massive data transport. You can't train a frontier AI model with latency-constrained data transmission. Either the training algorithm must be fundamentally redesigned to tolerate high latency between compute and data, or you need to move enormous datasets into orbit, which requires additional launch capacity.

Inference applications actually make more sense for orbital deployment. You send query data up to the satellite, it processes it using local models, and sends results back down. Inference latency tolerates higher delays than training.

Estimated data shows that a 100 sq meter solar array in space can generate approximately 45,000 watts continuously, leveraging the high solar constant and conversion efficiency.

The Engineering Gauntlet: Technical Challenges Ahead

Theoretical benefits are compelling. Execution is another matter entirely.

Radiation Hardening and Single-Event Upsets

Space is hostile to electronics. The radiation environment varies dramatically by orbit altitude and latitude. Low Earth orbit (LEO) at 400km altitude, where most current mega-constellations operate, intersects the Van Allen radiation belts. Solar energetic particle events can bathe satellites in dangerous radiation levels unexpectedly.

When a cosmic ray hits a transistor junction, it can cause a "single-event upset" (SEU)—a bit flip in memory or a miscalculation in logic. For a training computation spanning trillions of floating-point operations, SEUs accumulate and corrupt results.

Tesla needs to implement error correction at multiple levels. Memory can use error-correcting codes (ECC). Logic circuits need redundancy: triple-modular redundancy where three copies of a computation vote on the correct result. This overhead—both in area and power consumption—is significant.

Industry experience suggests radiation-hardened computing costs 5-15x more than standard silicon, requires more power to implement redundancy, and runs slower due to protective circuitry. Tesla's custom design advantage appears here: they can optimize the tradeoff between radiation hardening and performance more efficiently than general-purpose designs.

Thermal Architecture Complexity

Moving hundreds of megawatts of waste heat from processors to radiators requires engineering sophistication beyond typical data center experience. Servers on Earth have a straightforward thermal path: components generate heat, fans blow air across heat sinks, hot air exits the data center. Done.

In space, you need:

- Heat pipe networks: Copper tubes containing working fluid that transfers heat through capillary action, potentially across meters of distance

- Radiator design: Massive panels with specialized coatings to maximize emissivity while minimizing solar absorption

- Thermal redundancy: If one heat pipe fails, thermal runaway could destroy the satellite

- Micro-meteorite shielding: Radiators are exposed surfaces vulnerable to micrometeorite impacts

- Atomic oxygen protection: LEO contains atomic oxygen that oxidizes radiator coatings over time

This is essentially space-qualified liquid cooling but at scales and complexities orders of magnitude beyond current satellites. The International Space Station has advanced thermal systems, but even ISS thermal infrastructure operates at the scale of hundreds of kilowatts, not gigawatts.

Power Distribution Architecture

Earth-based data centers use efficient AC distribution: solar arrays or backup generators produce power at useful voltages (hundreds of volts), transmission lines distribute it through the facility, transformers step it down, and power supplies convert it to the DC voltages needed by servers (12V, 3.3V, etc.).

In space, solar arrays produce DC power directly, and transmission losses increase with distance. A satellite spanning hundreds of meters needs to distribute power efficiently across that distance without incurring unacceptable losses.

Tesla likely needs to develop entirely novel power distribution architecture: possibly radiative power transmission, or innovative ultra-high-voltage DC distribution with specialized rectification. This technology exists in concept but hasn't been deployed at the scales required for computational satellites.

Latency and Data Transmission

Processors in an orbital constellation sit 400+ kilometers overhead, relaying data through ground stations. Speed of light gives theoretical latency of 2.7 milliseconds for transmission to space and back. In practice, accounting for ground station unavailability, queue delays, and signal processing, latency to orbital compute is likely 50-200 milliseconds.

For inference applications, this is acceptable. For training, it's catastrophic. Neural network training requires constant gradient flows, parameter updates, and loss calculations. 100+ millisecond latency isn't tolerable for synchronous training algorithms.

Tesla would need to either:

- Deploy complete training datasets into orbit before training begins (massive logistics challenge)

- Develop asynchronous training algorithms that tolerate long latencies

- Partition models such that subsets train locally in orbit with periodic synchronization

All are complex, and none are current best practices in AI model development.

Manufacturing and Integration Complexity

Building space-qualified semiconductors is dramatically harder than terrestrial chips. Every stage requires additional testing, documentation, and validation:

- Pre-flight testing: Radiation exposure testing, thermal cycling, mechanical vibration testing, vacuum bake-out

- Qualification batches: Space agencies typically require qualification through multiple batches with extensive historical data

- Cost and timeline: Space-qualified chips typically cost 10-100x more than commercial equivalents and require 2-4x longer development cycles

Tesla's Dojo team previously worked on commercial-grade silicon for terrestrial data centers. Space qualification is a different discipline entirely, with few specialists worldwide. Rebuilding that expertise is non-trivial.

The Competitive Landscape: Who Else Is Pursuing This?

Tesla isn't alone in envisioning orbital compute infrastructure, though its position is uniquely advantageous.

Open AI and Microsoft: Both have discussed space-based infrastructure. Both have almost unlimited funding. Neither controls launch vehicles. Both would depend on Space X or emerging launch providers for access to orbit. This dependency limits their ability to execute quickly.

Google: Similar position to Open AI. Abundant capital, no launch capability. Additionally, Google's search and cloud infrastructure businesses generate enormous capital and ongoing revenue, making them less likely to bet existentially on unproven space-based compute.

Amazon: AWS generates substantial revenue. Jeff Bezos founded Blue Origin, which has launch capability. However, Blue Origin's current cadence (roughly one New Shepard suborbital flight per month) is far below what space-based compute would require. Developing new orbital launch vehicles takes years.

Chinese tech companies: Alibaba and Baidu have resources and some launch capability through Chinese government channels, but face export restrictions limiting access to advanced chips and technology.

Musk's advantage is structural: Space X launches weekly to LEO and is building Starship specifically for high-volume payload transport. Tesla can develop Dojo 3 knowing it has reliable, cost-effective access to launch capacity. Competitors face years of delay waiting for launch providers to scale.

Space-based compute initially appears 3-5x more expensive than terrestrial options, but long-term cost reductions are possible due to factors like free solar power and high utilization rates. Estimated data.

Dojo 3 Specifications: What Tesla Is Likely Building

While Tesla hasn't released detailed specifications, we can infer likely design choices based on the space-based requirements and Musk's public comments.

Core Architecture: Dojo 3 will almost certainly follow a different design than Dojo 1/Dojo 2. Those earlier chips were optimized for terrestrial autonomous driving inference—taking sensor data and making driving decisions in milliseconds.

Dojo 3 needs to optimize for orbital operation:

- High compute density (watts per square inch) to minimize radiator size

- Radiation tolerance through redundancy and error correction

- Power efficiency in absolute terms—each additional watt requires additional solar arrays and radiators

- Thermal architecture supporting liquid cooling with extensive heat pipe integration

Tesla likely targets 1-2 exa FLOPS per satellite (1-2 quintillion floating-point operations per second), achievable with 100-200 specialized processors each delivering 5-10 peta FLOPS.

Node Density: Compute nodes will be densely packed to maximize power per unit volume. Traditional server designs emphasize airflow and accessibility. Orbital nodes can be sealed, filled with liquid coolant, and optimized purely for thermal and power efficiency.

Tesla might achieve 10-100x higher compute density than terrestrial servers, accepting that individual nodes become impossible to upgrade or repair in place.

Memory Architecture: Orbital compute likely includes on-satellite memory measured in petabytes—terabytes of high-speed cache and memory local to processors, with only essential data transmitted to ground stations. This means Dojo 3 requires innovation in memory architecture as well as compute.

Interconnect: Communications between compute nodes within a satellite must handle enormous bandwidth. Optical interconnects (fiber optic) are likely, as they offer higher bandwidth density than electrical interconnects and are inherently rad-hard (photons aren't affected by radiation the way electrons are).

Power Stages: Unlike terrestrial Dojo chips designed for 12V and 3.3V rail voltages, Dojo 3 likely operates at unusual voltages optimized for space power distribution: possibly hundreds of volts directly from solar arrays, with specialized voltage conversion at the load.

Mask is recruiting engineers specifically to work on "the highest volume chips in the world," suggesting Dojo 3 is being designed not as a one-off space experiment but as a platform for massive volume production. This implies:

- Manufacturing partnerships with advanced foundries

- Design for manufacturability at scale

- Cost targets (likely targeting sub-$100k per chip despite space qualification)

- Standardized interfaces enabling multiple generations and variants

Timeline and Feasibility: When Could This Actually Happen?

Musk's characteristic optimism suggests a timeline of 2-3 years to first orbital Dojo 3 deployment. Industry reality suggests 4-6 years more likely, possibly 8-10 years for significant operational capacity.

Year 1-2: Chip Development

- Detailed architecture definition

- Radiation simulation and testing

- First silicon tape-out

- Space-grade manufacturing qualification

Year 2-3: Prototype Satellites

- Thermal design validation

- Power distribution prototyping

- Ground testing of orbital thermal systems

- First satellite assembly

Year 3-4: Launch and Commissioning

- Launch of prototype satellites (2-4 units)

- On-orbit testing and validation

- Thermal and power systems debugging

- Algorithm refinement for orbital operation

Year 5+: Production Constellation

- Manufacturing and launch of production satellites

- Constellation expansion to useful scale

- Operational AI compute services

This timeline is optimistic. Space projects commonly experience 2-3x schedule slippage. Thermal and radiation issues could emerge post-launch that require ground redesign and satellite repair missions. Data transmission bottlenecks might force algorithmic research taking years to resolve.

Realistic assessment: Dojo 3 in early operational form within 5-6 years, meaningful computational capacity within 8-10 years.

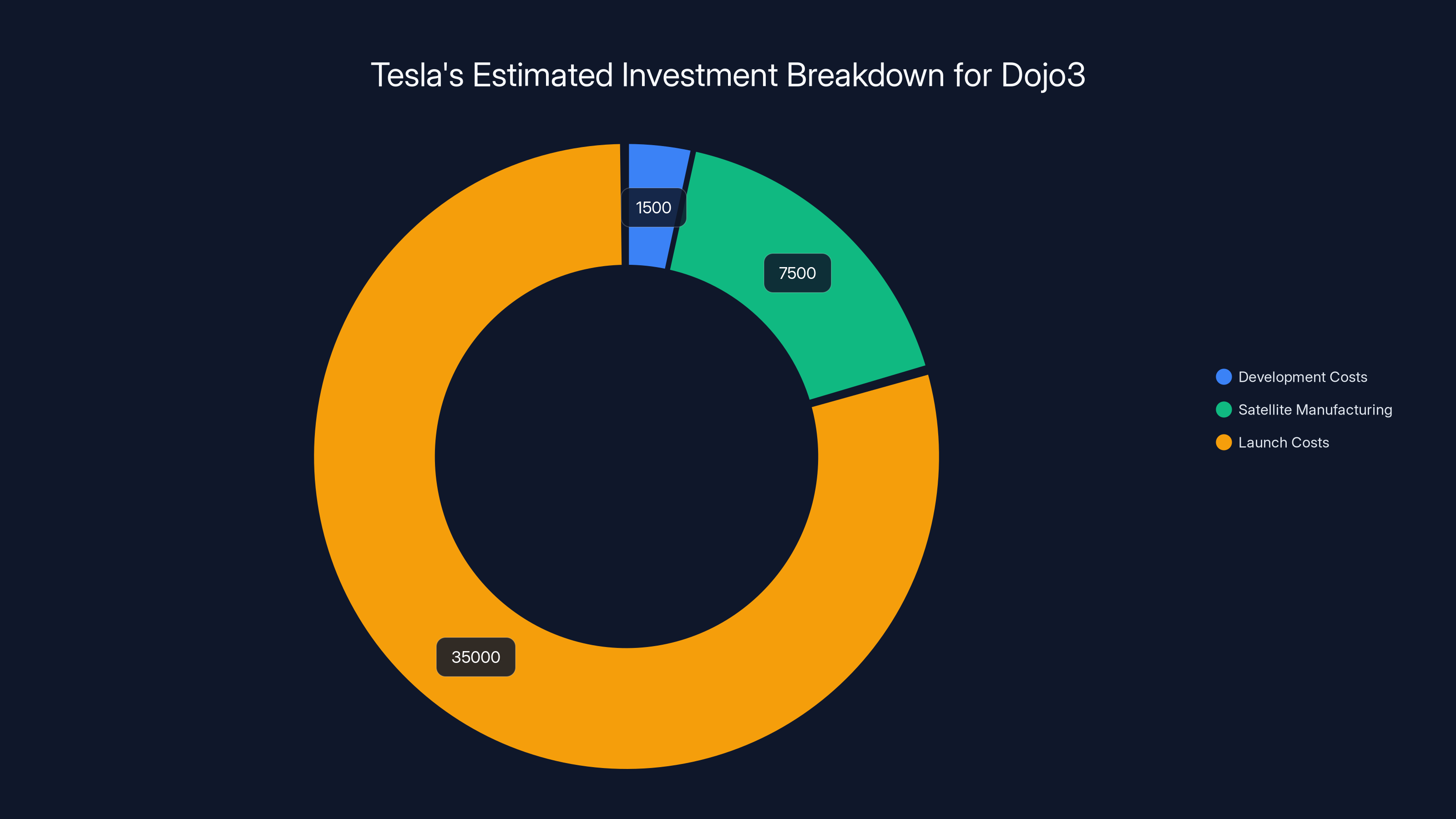

Launch costs represent the largest portion of Tesla's estimated $25-60B investment in Dojo3, highlighting the significant financial commitment required for satellite deployment. Estimated data.

The Economics: Could This Actually Be Cheaper?

Space-based compute sounds expensive. Let's examine whether it could actually reduce costs compared to terrestrial alternatives.

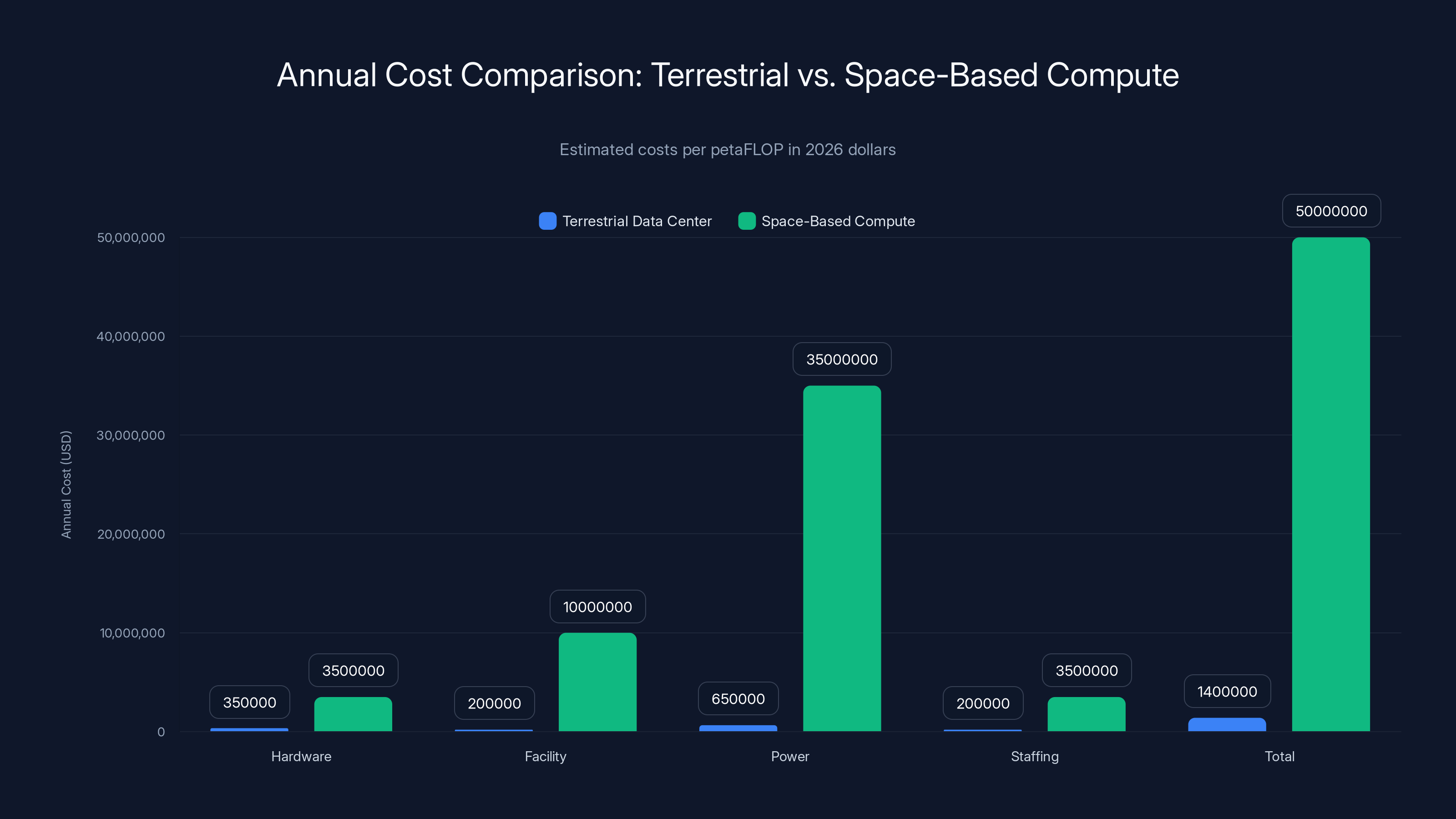

Terrestrial Data Center Economics (2026 dollars per peta FLOP annually):

- Hardware: 500,000 (GPUs, CPUs, memory, storage, networking)

- Facility: 300,000 (building, cooling infrastructure, power conditioning)

- Power: 1,000,000 (electricity costs, backup power)

- Staffing and maintenance: 300,000

- Total: ~$1-3 million per peta FLOP annually

Space-Based Compute Economics (hypothetical, 2026 dollars per peta FLOP annually):

- Space-qualified hardware: $2-5 million (Dojo 3 chips, radiation-hardened memory, specialized interconnect)

- Satellite manufacturing and integration: $5-15 million

- Launch costs: $20-50 million per satellite (assuming 10-100 peta FLOP per satellite)

- Power infrastructure (solar arrays): $2-5 million per satellite

- Amortization over 10-year satellite lifetime: $2.9-7 million per peta FLOP annually

Initially, space-based compute appears 3-5x more expensive. But the math changes when accounting for:

- No marginal power costs: Terrestrial electricity rises annually. Space solar is free after launch investment.

- Utilization rates: Terrestrial data centers operate at 40-60% utilization. Orbital infrastructure, once deployed, runs continuously at 100% utilization.

- Cooling efficiency: Orbital radiators could reduce cooling overhead by 50-80% compared to terrestrial facilities.

- Space advantage: After the first constellation is deployed, each additional satellite costs only incremental launch and satellite manufacturing. Terrestrial expansion requires new facilities.

Over 15-20 years, space-based compute could achieve 30-50% lower cost per peta FLOP than terrestrial alternatives, particularly if launch costs continue declining and orbital manufacturing scales.

This economics-driven shift aligns with historical patterns: expensive, unproven technology eventually becomes cheaper than established alternatives through volume production and optimization. Lithium-ion batteries seemed absurdly expensive in 2000. Renewable energy seemed uneconomical in 2005. Now both are cheaper than legacy alternatives.

Space-based compute follows the same trajectory.

Regulatory and Geopolitical Dimensions

Launching AI compute infrastructure into space raises complex regulatory and geopolitical questions that Tesla will inevitably encounter.

Space Traffic Management: As satellite constellations grow, space becomes congested. The Federal Communications Commission (FCC), through its coordination with the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), manages spectrum allocation and orbital slot assignments. Tesla will need to navigate licensing requirements for each satellite, justifying the orbital position and frequency bands.

Export Controls: Dojo 3 chips incorporate advanced semiconductor technology. U. S. export control regulations (EAR, ITAR) restrict the distribution of advanced semiconductors to certain countries. If Dojo 3 satellites operate globally, Tesla faces questions about controlling access to the compute infrastructure from restricted jurisdictions.

Debris and Safety: More satellites means more space debris risk. The U. S. Space Force and international bodies track orbital objects and monitor collision risk. Tesla must demonstrate adherence to space situational awareness requirements and debris mitigation strategies (e.g., designing satellites for de-orbit within 25 years).

Data Sovereignty and Privacy: If Dojo 3 satellites train or process data, which nation's privacy laws apply? EU data localization requirements restrict where European citizen data can be processed. China requires data servers within Chinese borders. Operating globally across multiple jurisdictions presents complex compliance challenges.

National Security: The U. S. Department of Defense and intelligence community will scrutinize Dojo 3 as critical infrastructure. Military and intelligence agencies rely on satellite communications and AI systems. A private company controlling significant AI compute in orbit could eventually trigger national security concerns, particularly if Musk maintains operational control.

These regulatory questions won't derail the project, but they'll complicate timelines and operations more than pure engineering challenges.

AI compute demand is projected to grow at an annual rate of 60%, significantly outpacing the 2-3% growth in power generation. Estimated data highlights the potential power crisis for AI infrastructure.

Comparison to Terrestrial Alternatives: Where Orbital Compute Wins and Loses

Orbital AI infrastructure won't replace terrestrial data centers. Instead, it will specialize in specific use cases where orbital infrastructure provides advantages.

Where Orbital Compute Wins:

- Inference at massive scale: Once deployed, orbital inference can handle billions of queries without additional power costs

- Long-duration training of specific models: Models trained once, then deployed globally via the orbital constellation

- Regulatory arbitrage: If a jurisdiction restricts AI development, companies can train in orbit rather than terrestrially

- Long-term cost reduction: After 8-10 year amortization, orbital compute becomes cheaper than continually expanding terrestrial infrastructure

- Geographic distribution: Global constellation enables low-latency inference worldwide without complex international agreements

Where Terrestrial Compute Retains Dominance:

- Development and prototyping: Iterative ML work requires rapid experimentation with latency tolerance

- Real-time systems: Autonomous driving, robotics, and other real-time applications need <100ms latency

- Data ingestion for training: Getting new data into orbital training pipelines introduces bottlenecks

- Short-term needs: Building orbital infrastructure takes years; terrestrial solutions scale in months

- Cost-sensitive inference: Established terrestrial infrastructure has years of amortization advantage

The most likely scenario: hybrid architecture. Companies maintain substantial terrestrial capacity for development and real-time applications. Orbital compute handles validated inference workloads, large-scale training of proven models, and applications with flexible latency requirements.

Industry Implications: What This Means for Nvidia, AMD, and Chip Suppliers

Tesla's pivot to orbital compute has significant implications for the semiconductor industry.

Nvidia's Position: Nvidia dominates terrestrial AI infrastructure through entrenched relationships with data center operators. Nvidia benefits from Tesla's continued reliance on consumer GPUs for Optimus development and other non-orbital applications. However, if space-based compute becomes economically viable, Nvidia faces commoditization of portions of its market. A 50% reduction in terrestrial data center demand growth (redirected to orbital) would significantly impact Nvidia's growth trajectory.

Nvidia will likely develop space-qualified GPUs in response, though doing so requires acquiring space expertise or partnering with space-qualified manufacturers. This compounds its exposure to a new technology domain.

AMD's Opportunity: AMD has historically been more willing to partner with non-traditional customers. AMD could potentially position its EPYC or MI-series processors as terrestrial alternatives while developing space-qualified variants. This dual approach could capture demand from companies building hybrid orbital-terrestrial infrastructure.

Intel's Challenges: Intel faces the dual burden of losing terrestrial market share to AMD and Nvidia while also needing to develop space-qualified variants. Intel's historical struggles with execution make this particularly challenging.

Foundry Consolidation: Samsung, TSMC, and Intel (as a foundry through Intel Foundry Services) will compete for orbital processor manufacturing. Space qualification creates barriers to entry, potentially favoring established foundries with aerospace experience. Samsung, which already manufactures AI chips for Tesla, holds an advantage.

New Entrants: Companies like Graphcore and other AI chip startups face questions about investment returns. If computing shifts to orbit with custom silicon requirements, the economics of vertical integration become more favorable than licensing IP to numerous customers. This could accelerate consolidation in the AI chip market.

Investment and Financing: Can Tesla Afford This?

Dojo 3 development and deployment is expensive but not prohibitive for Tesla.

Development Costs:

Satellite Manufacturing and Integration: $5-10B for first constellation (50-100 satellites). Substantial but achievable through Space X's cost reductions.

Launch Costs: $20-50B for launching initial constellation, depending on payload mass and Space X's evolving pricing. This is the largest single expense.

Total Program: $25-60B for initial operational constellation. For context:

- U. S. federal government spent $1.7B on semiconductor manufacturing in 2022

- Global semiconductor R&D spending is ~$30B annually

- Space X has raised $10B+ across multiple funding rounds

Tesla could finance this through multiple mechanisms:

- Internal cash flow: Tesla generates sufficient free cash to fund this over 5-7 years

- Space X IPO proceeds: If Space X launches an IPO (which Musk has indicated), proceeds could fund infrastructure

- Strategic partnerships: Google, Microsoft, and others might co-invest in orbital infrastructure, sharing costs and usage rights

- Debt financing: Tech companies can access debt markets relatively cheaply; $10-20B in bonds could supplement equity

The financial constraint isn't whether funding exists, but whether investors and creditors have confidence in the program's eventual profitability. Space ventures historically carry high perceived risk. That said, Musk's track record with Space X—transforming a seemingly impossible venture into a profitable, operational company—gives institutional confidence.

Alternative Interpretations: Is This Actually About Optimus Robots?

Musk might also be positioning Dojo 3 for an alternative purpose: powering distributed intelligence for Optimus robots globally.

The vision would be: Optimus robots deployed worldwide communicate with orbital AI systems rather than ground-based data centers. This enables:

- Low-latency coordination for swarm robotics and multi-robot tasks

- Distributed compute without reliance on centralized data center capacity

- Resilience through geographic redundancy

- Cost advantages if orbital compute becomes cheaper

From Musk's comments ("highest volume chips in the world"), this interpretation seems plausible. If Tesla eventually deploys hundreds of millions of Optimus robots, each requiring continuous AI inference, orbital compute becomes strategically valuable.

This dual-purpose framing (space-based training compute + Optimus inference backbone) potentially accelerates investment justification and regulatory approval.

The Path Forward: What Needs To Happen Next

For Dojo 3 to progress from announcement to operational reality, Tesla needs to:

-

Hire specialist talent: Recruit radiation hardness engineers, space thermal specialists, and orbital systems architects. These are scarce skills outside aerospace/defense.

-

Partner strategically: Secure relationships with space-qualified manufacturing partners, foundries capable of aerospace-grade production, and potentially defense contractors with relevant expertise.

-

Validate designs: Conduct extensive simulations and ground testing of thermal systems, power distribution, and radiation tolerance before committing to satellite manufacturing.

-

Secure regulatory approval: Work with FCC, State Department, Department of Defense, and international bodies to secure all necessary licenses and clearances.

-

Demonstrate economics: Conduct detailed analysis proving that orbital compute achieves promised cost benefits, publishing findings to justify investor confidence.

-

Build manufacturing infrastructure: Either internally develop satellite manufacturing capability or establish partnerships with established manufacturers.

-

Execute launches: Work with Space X to secure dedicated launch slots and develop deployment strategies for constellation.

Each represents a significant project independently. Together, they represent a multi-year, multi-billion-dollar commitment that will test organizational discipline and execution ability.

Historical Parallels: Learning From Previous Moonshots

Tesla's space-based AI compute announcement echoes previous industry disruptions that seemed implausible initially but became transformative:

Space X and Reusable Rockets: In 2002, the idea that Space X could cheaply and reliably land orbital rockets for reuse seemed absurd to traditional aerospace experts. Today, Space X lands boosters weekly and has dramatically reduced launch costs.

Tesla and EV Manufacturing: In 2009, claims that Tesla would revolutionize automotive manufacturing seemed unrealistic to legacy automakers. Tesla now produces millions of vehicles annually with manufacturing efficiency exceeding traditional competitors.

Starlink and Global Broadband: In 2015, Starlink's plan to deploy thousands of satellites for global broadband was dismissed as wasteful. Today, Starlink operates the largest satellite constellation, changing expectations for global connectivity.

Musk's track record suggests that dismissing his claims as impossible is frequently incorrect. He possesses a pattern of achieving technically ambitious goals through combination of obsessive focus, organizational commitment, and genuine technical talent.

That said, space-based AI compute is genuinely difficult in ways previous ventures weren't. Orbital thermal management at gigawatt scales is fundamentally constrained by physics in ways rocket recovery or EV manufacturing aren't. Success isn't guaranteed.

But the likelihood of meaningful progress is high.

Broader Implications: Beyond Tesla

Even if Tesla's Dojo 3 project faces delays or modifications, the concept of orbital AI infrastructure has already shifted from science fiction to serious industry consideration.

Accelerated Research: Universities and research institutions will increase funding for orbital thermal systems, radiation-hardened computing, and space-based infrastructure modeling.

Regulatory Evolution: Governments will need to develop policies governing AI compute infrastructure in orbit, establishing precedent for space-based computational sovereignty.

Infrastructure Shift: Within 15-20 years, expect major AI companies to operate hybrid terrestrial-orbital infrastructure, with allocation decisions based on workload characteristics and cost.

Launch Market Expansion: Increased demand for orbital infrastructure will drive launch market growth, benefiting Space X and accelerating emergence of competitor launch providers.

Talent Migration: Aerospace and space industries will attract AI and semiconductor talent as orbital compute becomes a major frontier. This could revitalize space sector employment and capability.

The announcement, regardless of ultimate success, is already reshaping industry thinking about infrastructure's future.

Conclusion: The Next Frontier of Computing Infrastructure

Elon Musk's January 2026 announcement that Tesla is restarting Dojo 3 as a space-based AI compute platform is either a brilliant strategic repositioning or a quixotic commitment to a technologically improbable venture. Reasonable people disagree on which.

What's clear is the announcement reflects genuine industry recognition that terrestrial power constraints will eventually limit AI development and that orbital infrastructure represents a plausible solution.

Tesla's unique advantages—control of Space X launch vehicles, significant capital, talented engineering organization, and Musk's demonstrated ability to execute difficult technical projects—create genuine possibility of success.

The technical challenges are substantial: radiation hardening, thermal management at unprecedented scale, power distribution architecture, and algorithmic redesign for orbital operation. None are individually insurmountable; collectively, they represent perhaps the most ambitious infrastructure engineering project since the Apollo program.

The economics potentially work: after 8-10 year amortization, orbital compute could achieve 30-50% cost advantages over terrestrial alternatives when accounting for perpetual solar power, radiative cooling efficiency, and operational utilization rates.

The timeline is likely longer than Musk's optimistic public projections: 5-6 years to prototype, 8-10 years to meaningful operational capacity.

The geopolitical and regulatory implications are complex but manageable: space traffic, export controls, data sovereignty, and national security questions will require navigation but won't block progress.

For Tesla specifically, Dojo 3 represents a pivot from providing custom silicon for Tesla's own applications (autonomous driving training, Optimus robotics) to becoming an infrastructure company selling orbital compute capacity globally. This represents a strategic departure from Tesla's historical role.

For the AI industry broadly, space-based infrastructure is no longer theoretical. It's a plausible future state, worth serious investment and preparation.

Either Tesla successfully develops operational orbital AI infrastructure, fundamentally reshaping computing's future trajectory. Or the project experiences delays and modifications, but still advances the state of the art in radiation-hardened computing, thermal management, and orbital operations.

Winning conditions exist on multiple paths. That's what makes this announcement genuinely significant.

FAQ

What is space-based AI compute?

Space-based AI compute refers to artificial intelligence infrastructure—processors, memory, and cooling systems—deployed in orbit and powered by solar arrays. Instead of training and running AI models in terrestrial data centers, this infrastructure harnesses continuous solar energy in orbit and radiates waste heat directly to deep space, potentially achieving cost and efficiency advantages over Earth-based systems.

How does Dojo 3 differ from earlier Dojo generations?

Dojo 1 and Dojo 2 were designed for terrestrial autonomous driving inference, optimized for low latency and specific driving-related computations. Dojo 3 is being redesigned specifically for orbital operation with radiation hardening, thermal architecture for radiative cooling in vacuum, and power distribution systems compatible with solar-powered satellite infrastructure. The design priorities are fundamentally different.

Why would orbital AI compute be cheaper than terrestrial data centers?

Orbital infrastructure has several cost advantages over extended timelines: continuous, free solar power eliminates electricity expenses; radiative cooling in space is potentially more efficient than air conditioning; operational utilization can reach 100% unlike terrestrial facilities; and after initial infrastructure investment, incremental costs per additional compute become marginal. While initial deployment costs are high, amortized over 15-20 years, orbital compute could achieve 30-50% cost reduction compared to continually expanding terrestrial capacity.

What are the main technical challenges for space-based AI compute?

The primary challenges include: radiation hardening to protect processors from cosmic rays and solar particle events; thermal management to reject waste heat via radiation to vacuum (rather than air cooling); power distribution architecture across orbital infrastructure; data transmission latency for training workloads; and extreme-altitude thermal stress testing. Each represents significant engineering difficulty with few real-world precedents.

When could Tesla's Dojo 3 actually become operational?

While Musk has suggested 2-3 years optimistically, realistic timelines suggest 5-6 years for prototype orbital deployment and 8-10 years for meaningful operational capacity. Space projects routinely experience 2-3x timeline slippage due to unexpected technical challenges, regulatory delays, and integration complexity. The most probable scenario involves prototype satellites demonstrating feasibility by 2030-2031, with production constellation deployment through the mid-2030s.

How does orbital compute compare to terrestrial alternatives for AI training?

Orbital infrastructure faces challenges for AI training due to latency constraints around data transmission to orbit—high-latency connections make synchronous gradient descent difficult. Orbital systems excel at inference applications with flexible latency requirements. Most likely, hybrid architectures emerge where training happens terrestrially with rapid iteration, while validated models deploy to orbital infrastructure for inference at massive scale.

Could other companies compete with Tesla's orbital AI infrastructure?

Open AI, Microsoft, Google, and other AI companies have discussed orbital infrastructure interest, but face competitive disadvantages versus Tesla: none control launch vehicle providers comparable to Space X; all must negotiate with external launch companies, adding cost and timeline uncertainty; and all lack Tesla's experience in custom silicon design combined with orbital systems knowledge. Tesla's structural advantage—owning launch capability and hardware expertise—is difficult for competitors to replicate quickly.

What happens to terrestrial data centers if orbital compute becomes viable?

Terrestrial data centers won't disappear but will specialize differently. Development, prototyping, and applications requiring real-time response will remain terrestrial. Long-duration training, global inference, and applications with flexible latency will migrate to orbital infrastructure. Most likely outcome is hybrid architecture where companies operate both terrestrial and orbital infrastructure, with workload allocation based on characteristics and cost. This mirrors previous transitions: cloud didn't eliminate enterprise IT, it complemented it.

What regulatory obstacles does orbital AI infrastructure face?

Key regulatory challenges include: spectrum allocation through FCC and ITU coordination; export controls on advanced semiconductors under U. S. trade regulations; space debris mitigation and orbital slot management; data sovereignty and privacy requirements varying by jurisdiction; and potential national security concerns if private companies control significant computational infrastructure in orbit. These challenges will delay timelines but are unlikely to prevent development.

Could orbital compute enable new AI capabilities impossible terrestrially?

Yes, potentially. Continuous power availability and abundant cooling enable extreme-scale inference that terrestrial power grids constrain. Global constellation enables low-latency inference worldwide without international data transfer complexity. Radiation-hardened processors designed for orbit could enable AI systems in space-based platforms (satellites, spacecraft) that currently lack adequate compute. The combination of capabilities opens possibilities not feasible terrestrially.

Why is Musk reviving Dojo after shutting it down?

The original Dojo program targeted terrestrial autonomous driving—a use case where Nvidia's GPUs proved economically sufficient despite premium pricing. Custom silicon didn't provide compelling advantages. However, orbital infrastructure has fundamentally different constraints: radiation, thermal management, power limitations. Custom silicon designed specifically for orbital operation offers genuine advantages that justify the investment. Musk's pivot reflects recognition that the original terrestrial use case didn't justify investment, while space-based applications do.

Expanding Your Knowledge on AI Infrastructure

If you're interested in exploring how AI infrastructure is rapidly evolving, consider exploring automation tools that help teams collaborate efficiently on complex technical projects. Runable offers AI-powered automation for creating presentations, documents, and reports—useful when your team needs to synthesize research, coordinate across departments, or communicate findings about emerging infrastructure technologies like orbital compute.

Use Case: Generate detailed technical reports on emerging AI infrastructure trends and prepare presentations summarizing orbital compute feasibility for executive stakeholders

Try Runable For Free

Key Takeaways

- Tesla is restarting Dojo3 specifically for space-based AI compute infrastructure, representing a pivot from terrestrial autonomous driving applications

- Orbital infrastructure offers potential 30-50% cost advantages over terrestrial data centers when amortized over 15-20 years, due to continuous solar power and efficient radiative cooling

- Technical challenges are substantial but surmountable: radiation hardening, thermal management at unprecedented scale, and power distribution architecture require specialized expertise

- Tesla's unique structural advantage—control of SpaceX launch vehicles—makes it more capable of executing this vision than competitor companies with similar funding but no launch capability

- Space-based compute will likely specialize in inference applications and long-duration training workloads, while terrestrial infrastructure retains advantages for real-time applications and iterative development

Related Articles

- Elon Musk's Tesla Roadster Safety Warning: Why Rocket Boosters Don't Mix With Cars [2025]

- Haven-1 Commercial Space Station: Assembly, Launch Timeline & Future Impact 2027

- Dr. Gladys West: The Hidden Mathematician Behind GPS [2025]

- Elon Musk's $134B OpenAI Lawsuit: What's Really at Stake [2025]

- OpenAI vs. Elon Musk: Silicon Valley's Biggest Legal Battle Headed to Trial [2025]

- Meta Compute: The AI Infrastructure Strategy Reshaping Gigawatt-Scale Operations [2025]