The SCAM Act Explained: How Congress Plans to Hold Big Tech Accountable for Fraudulent Ads

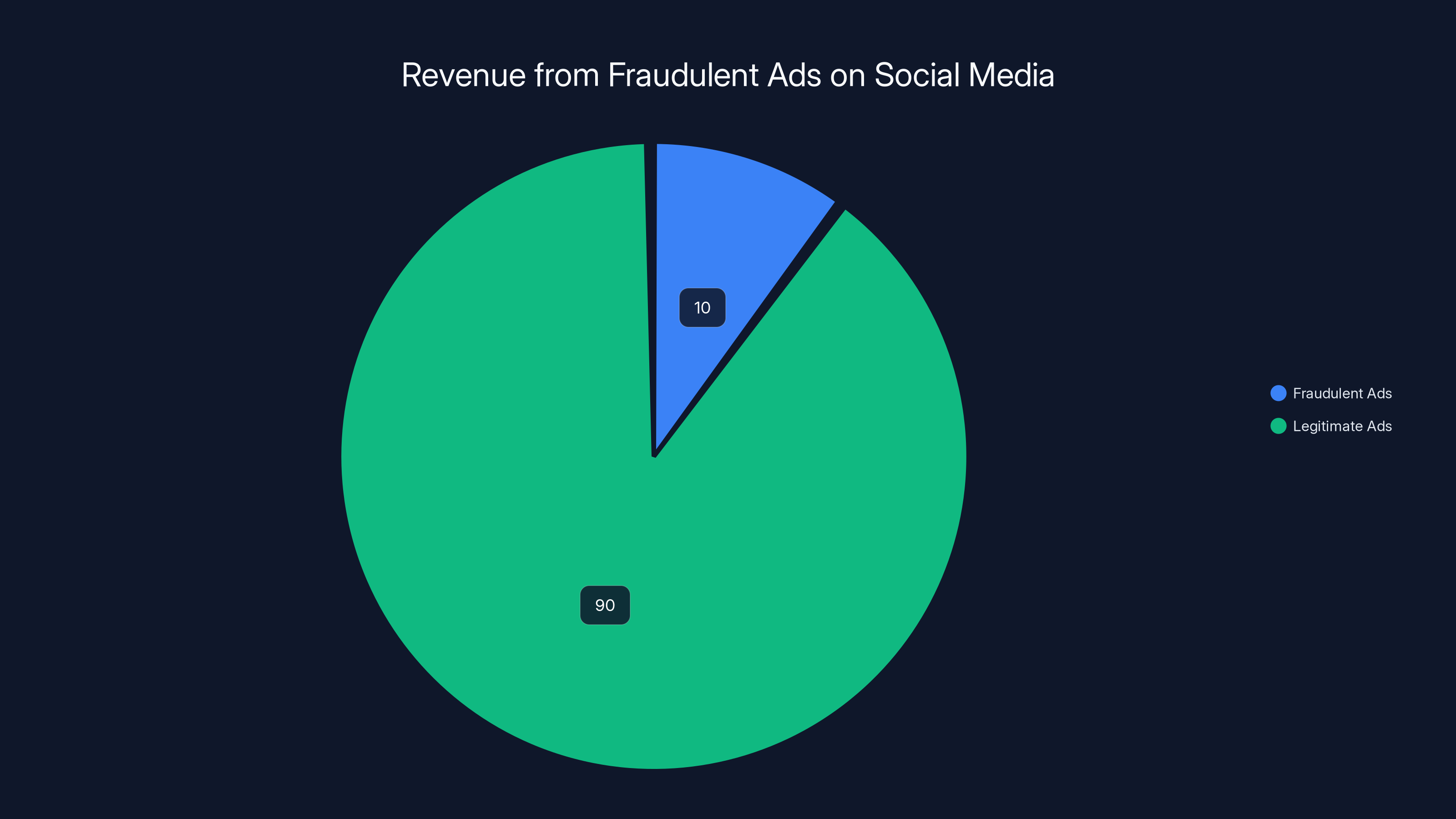

Let me be straightforward with you: scammers are making a fortune on your favorite social media platforms, and the platforms themselves know it. They're profiting from it. In fact, one major social network reportedly estimated that roughly 10 percent of its entire annual revenue came from fraudulent ads in 2024. That's not speculation. That's not hyperbole. That's billions of dollars flowing directly into company coffers while seniors lose their life savings to investment schemes and everyday people get duped by fake product listings.

For years, this reality sat behind closed doors. Executives fretted about it internally, calculated the cost of inaction, and decided it was cheaper to let fraud flourish than to police their own platforms aggressively. But last year, a major investigative report cracked the story open, and now Congress is finally responding with real teeth.

On a Wednesday in early 2025, two senators from opposite sides of the aisle—one Democrat, one Republican—introduced the Safeguarding Consumers from Advertising Misconduct (SCAM) Act. This legislation isn't flashy. It doesn't make headlines for flashy promises or sweeping bans. Instead, it does something more practical: it establishes a clear legal framework that could force social media companies to actually care about the ads they profit from.

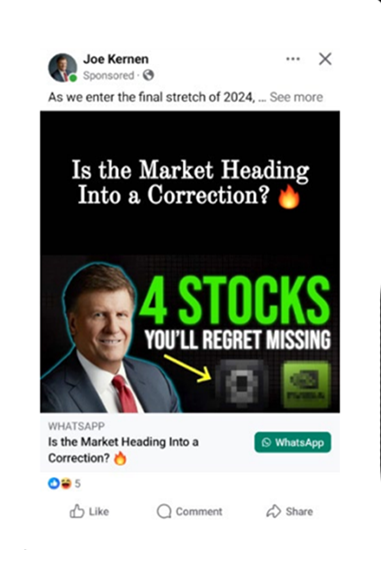

If you're a regular user of social media, you've probably seen these scam ads. They're everywhere. They promise unrealistic returns on crypto investments. They pretend to be celebrities endorsing weight loss pills. They dangle "exclusive opportunities" for dropshipping fortunes. Some are sophisticated enough to fool anyone. Others are so obviously fake that you wonder who falls for them. And yet, they persist. They multiply. They evolve.

The reason is simple: the business model incentivizes them. As long as someone clicks, as long as someone spends money, the platform makes money. The fraud is someone else's problem. Law enforcement's problem. The victim's problem. Not the platform's problem.

The SCAM Act changes that equation. Here's everything you need to understand about why this legislation matters, what it actually does, how it might work in practice, and what comes next in the fight against online fraud.

Understanding the Scale of the Fraud Problem

Before we can talk about solutions, we need to face the magnitude of the problem. The numbers are staggering, and they've been accelerating for years.

According to the Federal Trade Commission, Americans lost nearly

What's particularly insidious is that these aren't always sophisticated, difficult-to-spot frauds. Some are just obvious lies amplified by massive advertising budgets on social platforms. A scammer can spend a thousand dollars to reach a million people, and if even 0.1 percent of those people fall for it, they've made money. The economics of scale favor fraud when distribution is cheap and consequences are nonexistent.

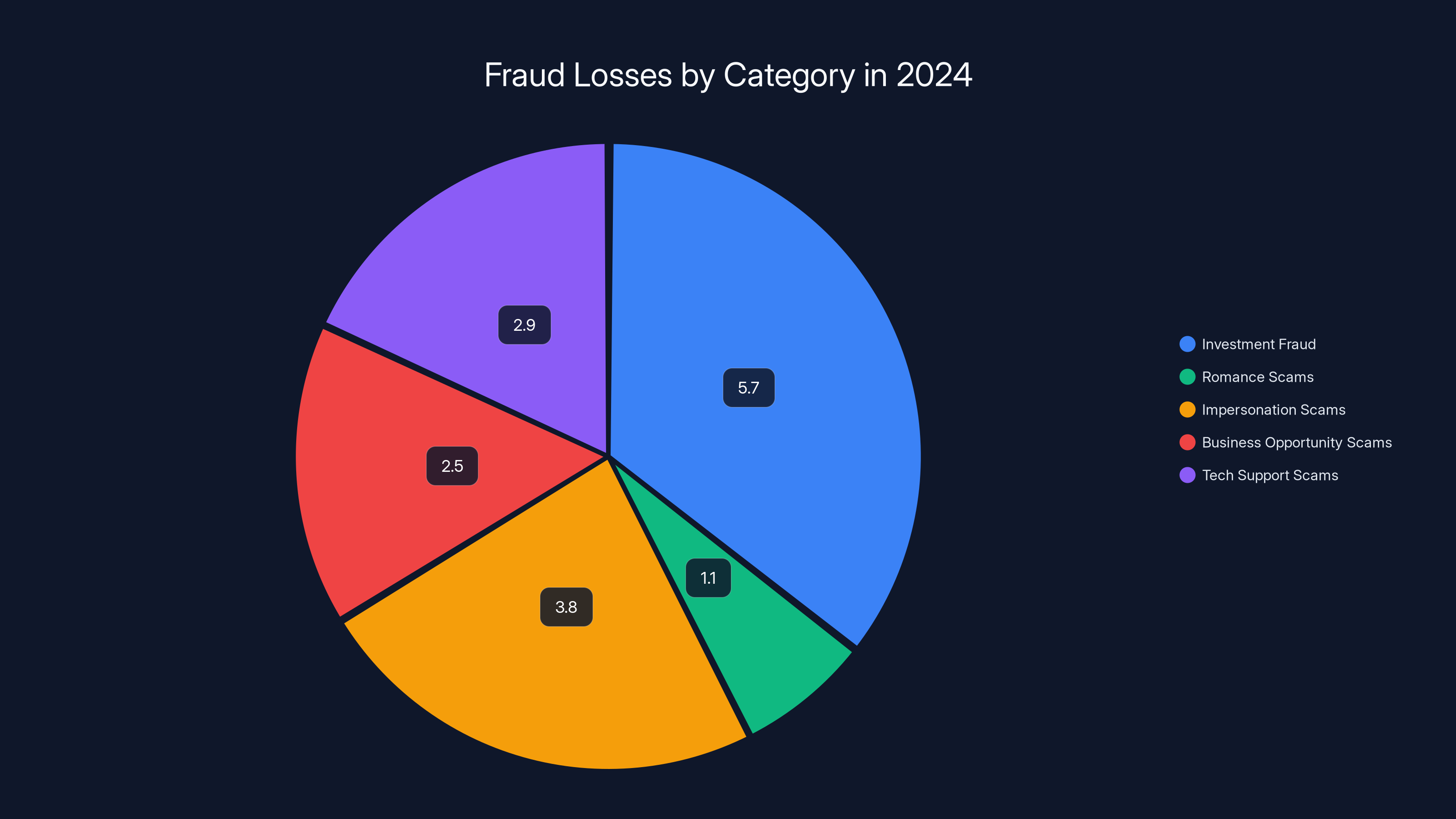

The breakdown of fraud losses tells the story. Investment fraud accounts for a massive chunk. Romance scams prey on emotional vulnerability. Impersonation scams exploit trust in authority and celebrity. Business opportunity scams dangle the promise of easy income. Tech support scams terrify people into paying for fake services. Each category has grown year over year, and each one is amplified through social media advertising.

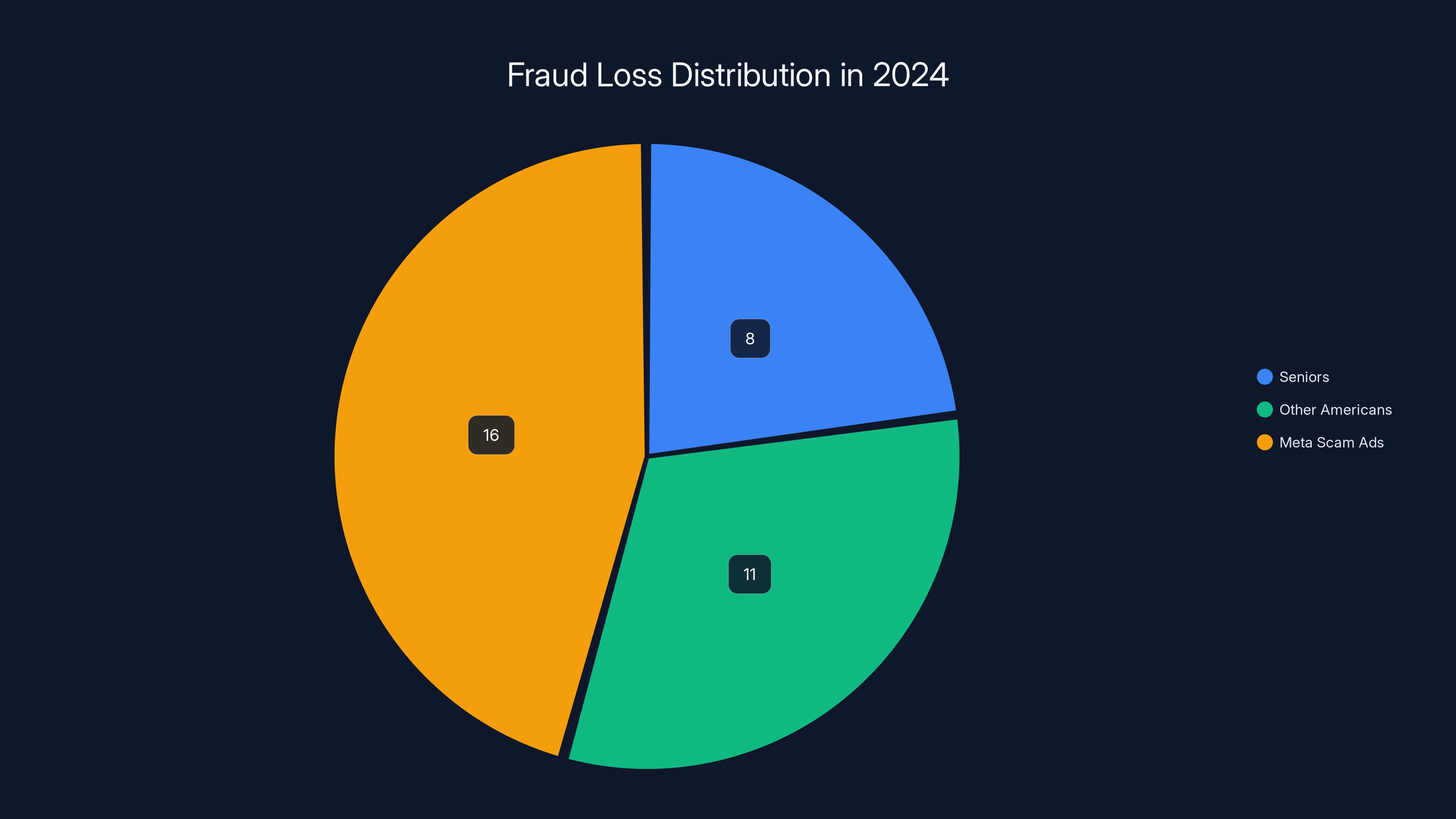

What makes this problem acute right now is the investigation that exposed the internal calculations at Meta. A Reuters investigation in late 2024 revealed something that seemed almost surreal: Meta had quantified exactly how much fraud revenue it was collecting. The company estimated that approximately $16 billion of its 2024 revenue came from scam ads. That's roughly 10 percent of total revenue. Ten percent. Not a rounding error. Not a negligible externality. A meaningful chunk of the company's business model.

More damning than the number itself was what executives were allegedly told in response. According to reporting, managers were instructed not to take actions that would cost the company more than 0.15 percent of total revenue. In other words, the company had done the math. They knew fraud was happening. They knew how much money it represented. And they decided that cleaning it up would be too expensive.

The internal policies that emerged from these calculations were equally telling. Small fraudsters were allowed to operate until their ads had been flagged at least eight times. But larger advertisers, the ones spending serious money, accumulated hundreds of strikes—allegedly up to 500 in some cases—before being removed. The message was clear: your ability to commit fraud on our platform is directly proportional to how much money you're spending.

This revelation created a unique moment in Congress. For once, there was bipartisan agreement that something needed to change. And from that agreement came the SCAM Act.

Investment fraud leads with estimated losses of

What Exactly Is the SCAM Act?

The Safeguarding Consumers from Advertising Misconduct Act is straightforward in its design, which is rare for legislation. It doesn't attempt to regulate speech or set arbitrary restrictions on advertising. It doesn't create new government agencies or massive bureaucracies. Instead, it does something simpler: it imposes a duty of care on platforms that profit from advertising.

The core requirement of the SCAM Act is this: online platforms must "take reasonable steps" to prevent and remove fraudulent or deceptive ads from their networks. That's it. That's the core of the legislation. Reasonable steps. Prevent. Remove.

Now, you might be thinking that platforms should already be doing this. And you'd be right. They should be. Many of them claim they already are. But here's the problem: there's no legal obligation, and there are no consequences for failure. The SCAM Act changes that by creating enforceable accountability.

If a platform fails to take reasonable steps, the legislation grants enforcement authority to two key players. First, the Federal Trade Commission can take civil legal action against the company. Second, state attorneys general can do the same. This means that if Meta, or Twitter, or Tik Tok, or any other platform isn't sufficiently aggressive in removing fraud, they could face lawsuits, penalties, and public embarrassment.

The sponsors of the bill were clear about the intent. Senator Ruben Gallego from Arizona, a Democrat, emphasized the responsibility angle: "If a company is making money from running ads on their site, it has a responsibility to make sure those ads aren't fraudulent." His language is direct. You profit. You're responsible.

Senator Bernie Moreno from Ohio, a Republican, focused on the victims and the enablers: "It is critical that we protect American consumers from deceptive ads and shameless fraudsters who make millions taking advantage of legal loopholes." He also called out the platforms explicitly: "We can't sit by while social media companies have business models that knowingly enable scams that target the American people."

Both senators understand what many in Congress are only beginning to grasp: these aren't accidental problems. These aren't edge cases. These are architectural features of business models that have proven profitable because fraud, at scale, is profitable.

The Bipartisan Nature of the SCAM Act Matters

If you've been paying attention to Congress for the past five years, you know that bipartisan agreement on tech regulation is rare. Usually, Democrats want to regulate for privacy and consumer protection. Republicans worry about Section 230 and free speech. They talk past each other. They introduce competing bills. Nothing passes.

But the SCAM Act cut through that. When you're talking about elderly people losing their retirement savings to scammers, when you're talking about ordinary Americans being defrauded by tens of billions annually, the partisan lines fade. This isn't about left versus right. It's about protecting people from fraud.

Gallego and Moreno have different constituencies. Gallego represents Arizona, a state where older voters are numerous. Moreno represents Ohio. But they share a common concern: their constituents are being victimized by fraud at scale. And the platforms enabling that fraud are doing so deliberately, having calculated that the profit is worth the cost to consumers.

Bipartisanship also matters from a practical standpoint. It signals that this legislation has staying power. A partisan bill can be reversed when control of Congress shifts. A bipartisan bill, especially one addressing consumer protection, tends to have longer life. It sets a precedent.

The bipartisan nature also makes it harder for platforms to dismiss as overreach or partisan attacks. When both parties agree that something is broken, it's harder to argue that critics are just trying to score political points.

Historically, bipartisan consumer protection bills tend to move. The legislation addressing junk text messages passed. Efforts to increase transparency around AI algorithms have gained bipartisan support. Consumer protection is one of the few areas where Congress can still find common ground.

In 2024, seniors lost over

How Would Platforms Actually Comply?

Here's where the SCAM Act gets interesting. The bill requires platforms to take "reasonable steps" to prevent and remove fraudulent ads. But what does that mean in practice? How would a platform like Meta or Tik Tok actually demonstrate compliance?

The answer isn't spelled out precisely in the legislation, which is intentional. Congress didn't want to mandate specific technical approaches because the tech landscape changes too fast. What counts as reasonable today might be obsolete in two years. Instead, the law establishes the goal and leaves flexibility in how platforms achieve it.

But we can imagine what reasonable steps might look like based on existing industry practices and capabilities. First, platforms could implement more aggressive automated detection systems. They already use machine learning to identify spam, misleading content, and policy violations. They could dial up the sensitivity on those systems for fraud detection specifically.

Second, they could hire more human reviewers focused on fraud. This is expensive, which is probably why they don't do it now at scale, but it's effective. Human reviewers can spot sophisticated scams that automated systems miss. They can understand context and intent in ways algorithms struggle with.

Third, platforms could verify advertisers more rigorously before approving their ads. Currently, the verification process is often minimal, especially for small advertisers. Requiring proof of business legitimacy, checking against fraud databases, and requiring identity verification would catch many fraudsters before they even launch their first ad.

Fourth, they could implement better user reporting systems and respond more quickly to reports. Right now, reporting a scam ad often feels futile. You report it, the platform sends an automated response, and the ad stays live. Faster response times and better feedback loops would help.

Fifth, they could be more transparent about what they're doing. Currently, most platforms publish transparency reports that give vague numbers about content removed. They could publish more detailed data about fraud specifically: how much fraud they detected, removed, and prevented.

The flexibility in the "reasonable steps" standard is both a strength and a potential weakness. It's a strength because it allows platforms to innovate and choose approaches that work for their architecture. It's a weakness because it gives platforms room to argue that whatever they're already doing constitutes reasonable steps, even if it's clearly insufficient.

This is where FTC and state attorney general enforcement becomes crucial. If a platform argues that their current efforts meet the reasonable steps standard, regulators will need to prove otherwise. That means examining internal documents, understanding the company's technical capabilities, and demonstrating that they could have done better.

The Meta revelations about internal calculations are particularly relevant here. If a company has determined that fraud is costing them nothing while earning them money, and then they claim they're taking reasonable steps to prevent it, that claim will be hard to defend in court.

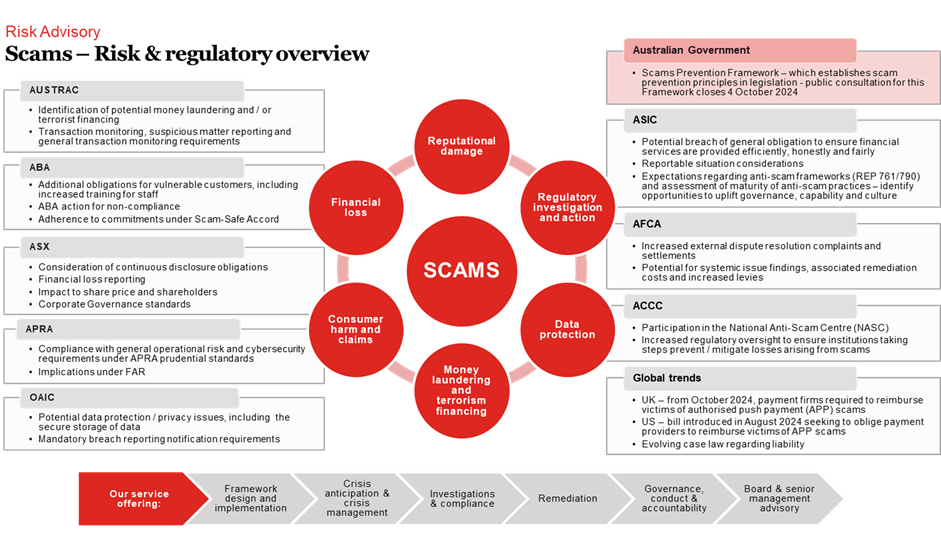

The FTC's Role in Enforcement

The Federal Trade Commission has been remarkably active in recent years when it comes to tech regulation. Under Chair Lina Khan, the FTC has taken an aggressive stance toward Big Tech, filing lawsuits against Amazon, Meta, and others over anticompetitive practices and consumer protection issues.

The SCAM Act would give the FTC explicit authority over platform fraud, which is significant. The FTC's core mandate is consumer protection, and fraud is perhaps the most fundamental consumer protection issue. The FTC has the expertise, the resources, and the infrastructure to take on fraud cases.

When the SCAM Act passes (and given its bipartisan support, it seems likely to eventually), the FTC could theoretically initiate investigations into any platform it believes isn't taking reasonable steps to prevent fraud. These investigations could lead to settlements, which often involve requirements for the company to implement specific changes, hire additional resources, and submit to monitoring.

The FTC has a track record with this kind of enforcement. In recent years, it has settled cases with Amazon over deceptive practices, with Twitter over privacy violations, and with numerous other companies. The pattern typically involves an investigation, alleged violations, negotiation, and a final settlement with ongoing compliance requirements.

For the SCAM Act specifically, the FTC's approach would likely involve establishing what "reasonable steps" means in a practical sense. They might examine company policies, review internal documents, audit fraud detection systems, and compare platforms' approaches against industry standards. Any company falling below the standard they establish could face enforcement action.

One advantage the FTC brings is its ability to conduct civil investigations without waiting for criminal fraud to be proven. The agency can compel companies to produce documents and respond to interrogatories. That power would be invaluable in understanding what platforms are actually doing—or not doing—to prevent fraud.

However, the FTC is also resource-constrained. The agency has to prioritize its enforcement actions. There's no guarantee that it would immediately or aggressively pursue every potential violation. The agency would need to make choices about which platforms and which types of fraud to prioritize.

This is where state attorneys general come in. The SCAM Act grants them concurrent enforcement authority, meaning they can sue independently. This is significant because it creates multiple enforcement pathways. A state attorney general might be particularly motivated to pursue a case if it involves significant losses in their state. This distributed enforcement model is actually quite clever—it reduces the burden on any single agency and creates multiple pressure points.

State Attorneys General as Enforcement Partners

Including state attorneys general in enforcement authority is a deliberate design choice that reflects how tech regulation often works in practice. States have been leading the way on tech regulation for years, sometimes pushing beyond what the federal government has been willing to do.

State AGs have the advantage of being closer to their constituents. If seniors in Florida are losing money to investment scams, the Florida attorney general faces direct political pressure to do something. If California is seeing massive fraud losses across its population, the California attorney general has incentive to act. This localized pressure can drive enforcement in ways that national agencies sometimes can't match.

State AGs also have been effective in coordinating multistate actions against tech companies. We've seen this with privacy cases, antitrust cases, and consumer protection cases. When multiple states band together to pursue enforcement action, the financial impact on a company can be significant. A settlement with 10 state AGs is much more expensive and disruptive than a settlement with a single agency.

The challenge with state enforcement is coordination. If every state goes after platforms slightly differently, companies could end up having to implement 50 different compliance regimens, one for each state. The legislation tries to prevent this by using a national standard—the same "reasonable steps" requirement applies everywhere.

However, interpretation could still vary state to state. One state's AG might argue that deleting a fraudulent ad within 24 hours is reasonable. Another might argue that 1 hour is necessary. These conflicts could lead to litigation and inconsistency.

Despite these challenges, state AG involvement is crucial. It decentralizes enforcement and makes it harder for platforms to ignore the problem or lobby their way out of accountability. It also means that enforcement can happen in multiple jurisdictions simultaneously, making it harder to drag out litigation.

Estimated data suggests that hiring more human reviewers is the most effective strategy for fraud prevention, followed by automated detection systems.

How Platforms Might Actually Respond

Assuming the SCAM Act passes and gets enforced, what would platforms actually do? How would they change their behavior? The answer likely involves a combination of technical, organizational, and financial changes.

First, expect significant investment in fraud detection and prevention. This means hiring more engineers, data scientists, and fraud analysts. It means building better machine learning models trained specifically on fraud detection. It means integrating with external fraud databases and intelligence sources.

Second, expect stricter advertiser verification. Platforms would likely implement more rigorous identity verification, business verification, and possibly even source-of-funds verification for advertisers. This creates friction in the onboarding process, which some advertisers won't like, but it's effective at keeping fraudsters off the platform.

Third, expect higher costs for advertisers overall. Some of these costs get passed through as fees. Some get absorbed as profit reduction. Either way, platforms will spend more on fraud prevention, and that has to come from somewhere.

Fourth, expect more transparency reporting. Platforms will likely publish more detailed data about fraud detection and prevention, both to satisfy regulatory requirements and to demonstrate to advertisers that their ad spend is going to legitimate placements.

Fifth, expect possible changes to advertising business models. Some platforms might reduce the volume of ads shown to users, particularly in high-risk categories. They might implement review delays for certain types of ads, slowing down ad deployment in exchange for better fraud prevention. They might increase minimum advertiser spending or require credit cards instead of accepting prepaid cards.

Sixth, there could be litigation. Platforms will likely challenge the SCAM Act or specific enforcement actions on constitutional grounds. Free speech arguments will be made. The courts will ultimately have to decide whether the government can require platforms to be more aggressive in removing fraudulent ads.

What's unlikely to happen is a platform shutting down advertising entirely. Advertising is too central to these companies' business models. Instead, you'll see managed change: more friction, more oversight, more resources dedicated to fraud prevention, but ultimately advertising remaining as a major revenue driver.

The Constitutional and Legal Questions

One of the reasons the SCAM Act was written so carefully is because there are real legal questions about whether Congress can require private platforms to police advertising more aggressively. These questions involve the First Amendment, Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, and the proper role of regulation in speech.

The First Amendment is relevant because advertising is a form of speech. The government generally can't compel private entities to censor speech just because it's offensive or even deceptive. This is different from regulation that prohibits certain types of speech—that's allowed. But regulation that requires platforms to remove speech faces more scrutiny.

However, fraud isn't protected speech. Even under a robust First Amendment interpretation, the government can criminalize fraud. The question is whether it can require platforms to do more to identify and remove fraudulent advertising. The answer is probably yes, but it's not certain.

Section 230 is also relevant. This provision of the Communications Decency Act protects platforms from liability for third-party content. It's been interpreted broadly to protect platforms from suits over moderation decisions. However, Section 230 applies to liability—to being sued. It doesn't prevent the government from regulating platforms directly.

So the legal question isn't whether the government can hold platforms liable for fraudulent ads under Section 230. It's whether the government can impose affirmative duties on platforms to police content. This is different, and the answer is almost certainly yes. Courts have consistently held that the government can impose reasonable regulations on commercial actors without violating the First Amendment.

The SCAM Act is crafted in a way that should survive constitutional challenge. It doesn't prohibit any particular speech. It doesn't require platforms to use specific techniques. It doesn't give the government direct editorial control. Instead, it imposes a duty of care—a requirement that platforms take reasonable steps to prevent fraud.

Duties of care are common in regulation. Your bank has a duty of care to prevent money laundering. Your hospital has a duty of care to follow safety protocols. Your restaurant has a duty of care to inspect food. These aren't seen as infringing First Amendment rights even though they impose significant compliance costs.

That said, platforms might still challenge the SCAM Act. They could argue that the reasonable steps standard is too vague. They could argue that increased fraud prevention costs will reduce the quantity of speech on their platforms (a kind of chilling effect). They might argue that the law discriminates against them while leaving other advertisers (in newspapers, on billboards) unregulated.

These arguments have some merit, which is why the legal question is genuinely uncertain. But on balance, most legal experts who have looked at this believe the SCAM Act would survive constitutional challenge. The precedent for government regulation of fraud, and for imposing duties of care on companies that facilitate fraud, is quite strong.

Comparing Global Approaches to Platform Accountability

The United States isn't alone in trying to tackle fraudulent advertising on platforms. Other countries and regions have taken different approaches, and understanding those provides context for evaluating the SCAM Act.

The European Union has been notably aggressive in regulating online platforms through the Digital Services Act and the Digital Markets Act. These regulations go further than anything currently proposed in the U. S., imposing sweeping requirements on how platforms operate, moderate content, and handle advertising.

The UK has taken a different approach with the Online Safety Bill, which focuses on illegal content, content harmful to children, and user protection more broadly. The regulations include a duty of care for platforms, similar in spirit to what the SCAM Act proposes but broader in scope.

Canada is working on digital legislation that emphasizes user protection and platform accountability. Australia has been particularly aggressive in forcing platforms to pay news publishers for content and in requiring stronger action against misinformation.

The SCAM Act is relatively narrow compared to these global approaches. It focuses specifically on fraud in advertising, not broader misinformation, privacy, or content moderation. In some ways, this narrowness is a strength—it makes the legislation easier to pass and harder to challenge legally. In other ways, it's a limitation—it addresses only one aspect of platform harms.

What's interesting about the SCAM Act in the global context is that it suggests the U. S. is moving toward the regulatory model that other countries have already adopted. Rather than relying solely on platforms' self-regulation, governments are imposing explicit duties and creating enforcement mechanisms.

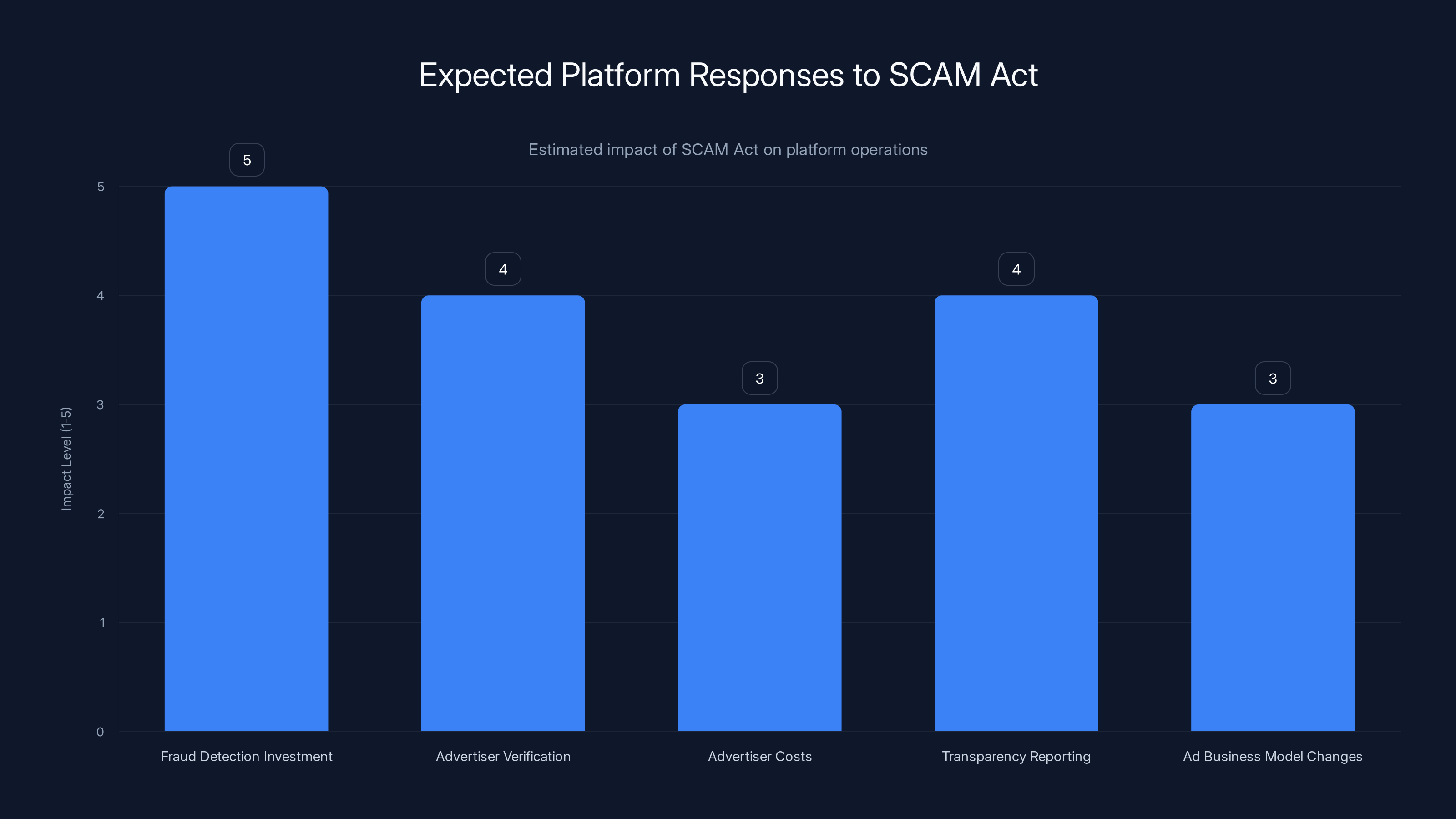

Platforms are expected to significantly invest in fraud detection and implement stricter advertiser verification, with moderate impacts on costs, transparency, and business models. Estimated data.

The Timeline and Prospects for Passage

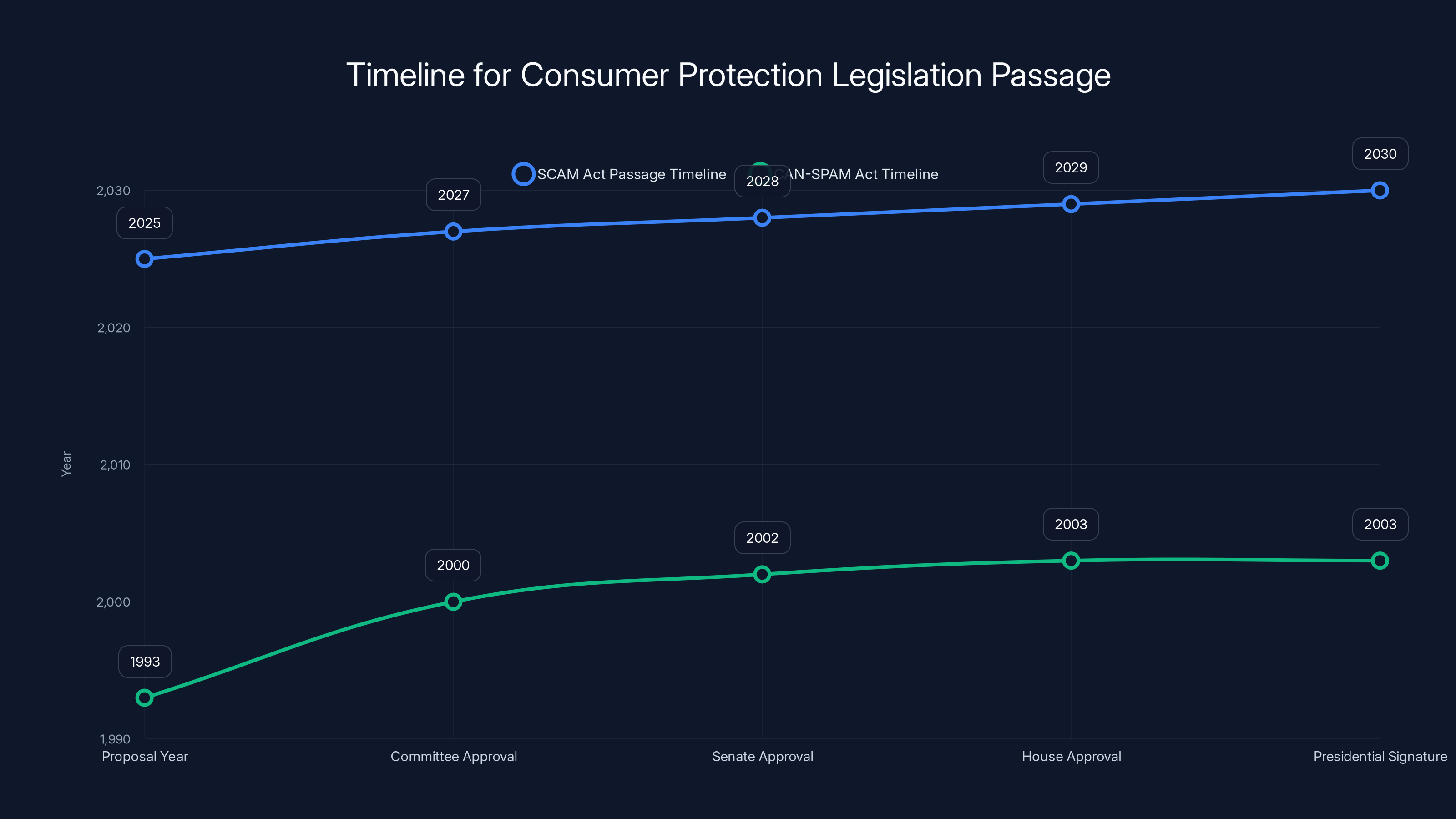

Bipartisan legislation in Congress moves slowly, but when it moves, it often moves further than anyone expects. The SCAM Act was introduced in early 2025, and as of now, it doesn't have a clear path to a vote. However, its bipartisan sponsorship suggests that patience might be rewarded.

Historically, consumer protection bills take time to build support but often ultimately pass. The legislation addressing robocalls and junk text messages took years to develop but ultimately passed with strong support. Bills addressing data breaches and privacy have followed similar patterns.

The SCAM Act would likely need to navigate several hurdles. First, it would need to gain co-sponsors and build momentum in the relevant committees (likely the Commerce Committee in the Senate). Second, it would need to be marked up and passed out of committee. Third, it would need to pass the Senate, then the House, then be signed by the President.

Each of these steps could involve modifications to the bill. Congressional negotiations often water down legislation. The SCAM Act might come out of committee looking somewhat different from how it was introduced. Definitions might be clarified. The reasonable steps standard might be defined more precisely. Enforcement mechanisms might be tweaked.

There's also the question of platform lobbying. Tech companies spend enormous amounts on lobbying, and they will undoubtedly lobby against the SCAM Act or for modifications to it. They have substantial resources to deploy, and they have relationships with members of Congress.

However, the fraud angle is powerful politically. If you're a senator and you vote against a bill designed to stop fraud targeting seniors and ordinary Americans, you're vulnerable politically. The platforms will have to lobby carefully, probably not directly opposing the bill but instead advocating for modifications that reduce its impact.

One likely modification would be trying to narrow the definition of fraud or "reasonable steps," making it easier for platforms to claim compliance. Another would be trying to build in safe harbors or carve-outs for certain types of content or advertisers.

Despite these challenges, the political environment seems favorable for the SCAM Act in some form. Consumer protection is one of the few areas where Congress can agree. The investigation revealing Meta's calculations about fraud revenue has soured public opinion. And the human impact—elderly people losing retirement savings—is compelling and nonpartisan.

If I had to guess, I'd say the SCAM Act in some form passes within the next 18-24 months. It might not be exactly as introduced, but the core requirement—that platforms take reasonable steps to prevent fraud—seems likely to become law.

What Platforms Claim They're Already Doing

It's important to note that platforms will argue that they're already taking significant steps to prevent fraud. Meta, Google, and other major platforms have published information about their fraud prevention efforts, their investment in safety teams, and their willingness to work with law enforcement.

These claims aren't entirely baseless. Platforms do use machine learning to identify fraudulent ads. They do maintain teams focused on safety and fraud. They do remove millions of violative pieces of content every day. They do cooperate with law enforcement on fraud investigations.

But here's the crucial point: they do this within the constraints of their business model. If being more aggressive about fraud prevention would cost more than the revenue from fraud, they won't do it. The Meta revelations made this explicit, but it's true more broadly. Platforms optimize for profit while meeting a minimum threshold of user safety and regulatory compliance.

The SCAM Act would change those incentives. By creating legal liability for insufficient fraud prevention, the cost-benefit calculation changes. Being more aggressive about fraud becomes necessary, not optional.

Platforms might claim that the SCAM Act sets an impossibly high standard, that fraud will always exist and they can't eliminate it entirely. And that's true. Some fraud will slip through. But that's not what the legislation requires. It requires reasonable steps, not perfection. It's a duty of care, not a guarantee.

The Economic Impact on Advertisers and Platforms

Implementing the SCAM Act would have economic consequences. These aren't reasons to oppose the legislation—consumer protection has costs—but they're worth understanding.

For platforms, the direct costs would include hiring additional fraud prevention staff, developing better detection systems, and implementing stricter advertiser verification. These costs could add up to hundreds of millions annually across the major platforms.

These costs might be passed to advertisers through higher advertising fees. Legitimate advertisers already pay in the form of higher costs and reduced placements due to fraud. If fraud is reduced, advertising ROI might improve, which could offset higher fees.

For small advertisers, stricter verification might create barriers to entry. A small business might have difficulty proving business legitimacy quickly enough to meet platform requirements. This could reduce competition in some markets, as larger, more established companies have easier time with verification.

However, these costs need to be weighed against the billions of dollars in fraud losses that continue under the status quo. If the SCAM Act reduces fraud by even a modest percentage, the economic benefit to consumers dwarfs the compliance costs to platforms.

Consumer protection bills like the SCAM Act often take several years to pass. The CAN-SPAM Act took 10 years from proposal to passage. Estimated data for SCAM Act based on historical trends.

Implementation Challenges and Solutions

Implementing the SCAM Act effectively will require solving several practical challenges. How do you define fraud with precision sufficient for legal enforcement? How do you distinguish fraud from exaggerated marketing claims? How do you handle borderline cases?

These questions don't have perfect answers, which is why the "reasonable steps" standard exists. It acknowledges that fraud prevention is an art and a science. It requires good faith efforts but doesn't demand perfection.

One implementation challenge is the global nature of fraud. Many scammers operate from outside the United States. They use foreign payment processors, create shell companies in other countries, and hide behind anonymity services. A U. S. law requiring platforms to prevent fraud does nothing to stop scammers from committing fraud in the first place. It just shifts responsibility to the platforms.

Platforms can, however, prevent fraudsters from advertising at scale. By blocking accounts, removing ads, and refusing payment from known fraudsters, platforms make it harder for fraud to reach large numbers of people. This is within their power.

Another implementation challenge is false positives. If fraud detection systems are too aggressive, they might block legitimate advertising. For example, a cryptocurrency exchange might look like a scam to an automated system. A new dietary supplement might trigger fraud filters. Getting the balance right requires both technology and human review.

The Broader Conversation About Platform Accountability

The SCAM Act is one piece of a broader conversation happening in Congress and around the world about how to hold tech platforms accountable. This conversation includes debates about antitrust, privacy, content moderation, and algorithm transparency.

Some people argue that the real solution to platform harms is to break up large tech companies. Others argue that you need more regulation of their data practices. Still others focus on algorithm transparency or content moderation.

The SCAM Act takes a different approach. It doesn't break up platforms, regulate their data practices, or mandate specific content moderation standards. Instead, it focuses on a specific, measurable harm—fraud—and makes platforms legally liable if they don't take reasonable steps to prevent it.

This narrower approach has advantages and disadvantages. The advantage is that it's achievable. It doesn't require a wholesale reimagining of how platforms operate. The disadvantage is that it addresses only one problem. Even if the SCAM Act works perfectly and eliminates 90 percent of fraud on platforms, there are still other harms that remain unaddressed.

But progress often works this way. You address one problem, then move on to the next. The SCAM Act establishes the principle that platforms have duties to consumers and that courts and regulators can enforce those duties. That principle, once established, could extend to other harms.

Looking Ahead: What Comes After Passage

If and when the SCAM Act passes, the real work begins. Platforms will implement changes, often grudgingly and with legal challenges. The FTC and state AGs will develop enforcement guidance. Test cases will move through the courts. Platforms will argue about what "reasonable steps" actually means.

Over time, the legislation will settle into its practical role. It will become another constraint on platform behavior, another cost of doing business, another factor in the platforms' decision-making. Some fraud will be prevented. Some won't. The system won't be perfect.

But imperfect progress is still progress. If the SCAM Act reduces fraud losses by even 5-10 percent, that's billions of dollars annually staying out of scammers' hands and in the pockets of consumers. That's the bar to clear.

Beyond fraud, the SCAM Act establishes an important precedent: platforms can be held accountable for harms associated with their business models. This principle will inevitably extend. If fraud requires reasonable prevention steps, what about misinformation? What about illegal content? What about manipulation and dark patterns designed to addict users?

The SCAM Act might be narrow, but it's not unimportant. It cracks open the door to platform accountability, and what comes through that door next remains to be seen.

In 2024, fraudulent ads accounted for an estimated 10% of a major social network's annual revenue, highlighting the significant financial impact of scam ads. Estimated data.

The Role of Users in Reporting and Prevention

Platform-level fraud prevention is important, but user vigilance also matters. One element of the SCAM Act's implicit framework is that users will report fraudulent ads, and platforms will respond to those reports effectively.

Currently, most users don't report scam ads. They see them, recognize them as scams, and scroll past. Why report something the platform probably won't do anything about? If the SCAM Act creates real consequences for failing to address reported fraud, the incentive structure changes. Users might start reporting more aggressively. Platforms might start responding more quickly.

Education also plays a role. The Federal Trade Commission publishes guidance on avoiding scams. Schools and libraries offer financial literacy classes. Trusted voices speak out about red flags in fraudulent ads. This education helps people avoid being scammed in the first place.

However, education and user vigilance have limits. Sophisticated scams fool smart, educated people. Vulnerable populations—particularly the elderly—face specific challenges in identifying fraud. Relying solely on users to protect themselves isn't sufficient. Platforms must also prevent scams from reaching users in the first place.

The SCAM Act doesn't eliminate the need for user education or individual vigilance. It just adds another layer of protection by making it costly for platforms to ignore fraud.

Common Objections and Counterarguments

The SCAM Act will face objections from multiple directions. Understanding these objections and the responses to them is important for evaluating the legislation.

Objection 1: This is overregulation that will stifle innovation. Counterargument: The SCAM Act doesn't prescribe specific technical approaches to fraud prevention. It allows platforms flexibility in how they prevent fraud. And preventing fraud isn't innovation—it's basic consumer protection.

Objection 2: You can't eliminate fraud entirely, so this standard is impossible to meet. Counterargument: The law doesn't require eliminating fraud. It requires reasonable steps. Meeting a reasonable standard is achievable and is already being done by some platforms more aggressively than others.

Objection 3: This will raise advertising costs for legitimate advertisers. Counter Argument: Legitimate advertisers are already paying higher costs due to fraud-driven inflation in the ad market. Reducing fraud should improve their ROI and likely lower costs overall.

Objection 4: The definition of fraud is unclear and will lead to First Amendment problems. Counter Argument: Fraud has a well-established legal definition. The government has long criminalized fraud. Fraud isn't protected speech. Adding a duty to prevent fraud doesn't create a novel First Amendment problem.

Objection 5: International scammers will just find other platforms or workarounds. Counter Argument: Probably some will. But making it harder to advertise fraud at scale on major U. S. platforms is still valuable. It reduces the damage even if it doesn't eliminate fraud entirely.

Lessons from Other Fraud Prevention Efforts

The U. S. has experience regulating fraud in other contexts. The credit card industry, for instance, has developed sophisticated fraud prevention systems. The banking system uses various fraud prevention techniques. These experiences offer lessons for the SCAM Act.

One lesson is that fraud prevention requires investment. Banks spend billions annually on fraud prevention. Credit card companies employ thousands of people in fraud detection and prevention. This isn't cheap, but it's effective. The fraud rate in credit cards is less than 0.1 percent in most cases, despite billions in transactions annually.

Another lesson is that fraud prevention requires both technology and people. Algorithms are good at identifying patterns and anomalies. But humans are better at understanding intent and context. The most effective fraud prevention systems use both.

A third lesson is that transparency and accountability help. When institutions are required to report fraud rates and fraud prevention efforts, they tend to invest more in prevention. Knowing you'll be held accountable motivates better performance.

A fourth lesson is that prevention is cheaper than enforcement. Stopping fraud before it happens is much cheaper than prosecuting fraudsters after the fact. Every dollar spent on fraud prevention saves multiple dollars in fraud losses.

The SCAM Act implicitly uses all of these lessons. It requires platforms to invest in fraud prevention. It creates accountability through enforcement authority. It uses both technological and human-based approaches implicitly in the "reasonable steps" standard.

The Future of Online Advertising If the SCAM Act Becomes Law

Assuming the SCAM Act passes and gets enforced effectively, what does the future of online advertising look like? How will the landscape change?

First, there will be more friction in the ad creation process. Advertisers will face more verification requirements. There might be review delays for new ads or advertisers. This is inconvenient but effective at preventing fraud.

Second, advertising quality should improve. With fraudsters pushed off platforms, the average quality of ads will increase. Users will see fewer scams. Legitimate advertisers will get better placement and better ROI.

Third, advertising costs might change. In the short term, they might increase due to compliance costs. But in the long term, reducing fraud could lower costs by reducing the inflation in ad prices caused by fraud.

Fourth, platforms might become more transparent about their fraud prevention efforts. This helps legitimate advertisers understand that their ad spend is going to reach real people, not fraud victims being retargeted.

Fifth, there might be more regulation. The SCAM Act establishes the principle of platform accountability for advertising harms. Subsequent legislation might extend this to other harms or to other aspects of platform operation.

Overall, the landscape moves toward greater accountability and less friction for legitimate users and advertisers, with more friction for bad actors.

Conclusion: Why the SCAM Act Matters Now

The SCAM Act doesn't sound revolutionary. It doesn't promise to transform the internet or dismantle Big Tech or solve all problems with online platforms. It just requires platforms to take reasonable steps to prevent fraud.

But in the context of platform accountability, this is significant. For years, platforms have operated with minimal legal responsibility for the harms associated with their business models. They publish transparency reports touting their content moderation efforts while simultaneously optimizing their systems to maximize engagement and profit, consequences be damned.

The revelations about Meta's internal calculations—the idea that executives consciously decided fraud was worth the revenue—represent a breaking point. Congress is responding with legislation that makes this calculation impossible. If you're profiting from fraud and not aggressively preventing it, you'll face legal consequences.

This matters for fraud victims immediately. If platforms become more aggressive about fraud prevention, fewer people will be scammed. That's direct benefit.

It also matters for the long-term evolution of tech regulation. The SCAM Act establishes that platforms have duties to consumers that can be enforced through the courts. That principle, once established, will be difficult to roll back. Future regulations can build on it.

It matters for legitimate advertisers and users too. A cleaner advertising environment, with less fraud, is better for everyone except scammers.

The SCAM Act isn't perfect legislation. It's somewhat vague in places. It faces legal challenges. Its enforcement will be imperfect. But it represents a meaningful step toward holding platforms accountable for the harms associated with their business models.

For the people losing billions to fraud, for the seniors watching their retirement savings disappear, for the ordinary people being scammed out of money they can't afford to lose, the SCAM Act is long overdue. It's not a perfect solution, but it's a real one.

FAQ

What is the SCAM Act?

The Safeguarding Consumers from Advertising Misconduct (SCAM) Act is bipartisan legislation introduced by Senators Ruben Gallego and Bernie Moreno that requires online platforms to take reasonable steps to prevent and remove fraudulent or deceptive advertisements. The bill grants enforcement authority to the Federal Trade Commission and state attorneys general to pursue civil legal action against platforms that fail to meet this standard. The legislation targets the epidemic of fraud losses affecting millions of Americans, particularly seniors who lose billions annually to investment schemes, romance scams, and other frauds advertised on social media.

Why is the SCAM Act needed?

According to the Federal Trade Commission, Americans lost nearly

How would platforms comply with the SCAM Act?

Platforms would be required to take "reasonable steps" to prevent and remove fraudulent ads, with flexibility in how they achieve this. Compliance likely involves implementing more sophisticated automated fraud detection systems, hiring additional fraud analysts and human reviewers, verifying advertiser identity and business legitimacy before approving accounts, improving user reporting systems and response times, and publishing more detailed transparency reports on fraud detection and prevention efforts. The intentional vagueness of "reasonable steps" allows platforms flexibility in their approaches while still holding them accountable for results, with enforcement agencies like the FTC determining whether actions meet the standard through investigation and litigation if necessary.

Who enforces the SCAM Act?

The Federal Trade Commission and state attorneys general share concurrent enforcement authority under the SCAM Act. The FTC can initiate investigations and take civil legal action against platforms failing to meet the reasonable steps standard, while state attorneys general can pursue enforcement independently. This distributed enforcement model is significant because it creates multiple pressure points and makes it harder for platforms to ignore the problem. State attorneys general are particularly motivated to pursue enforcement when seniors or residents in their states are experiencing significant fraud losses, ensuring localized accountability.

What happens if platforms violate the SCAM Act?

If regulators determine that a platform isn't taking reasonable steps to prevent fraud, they can file civil lawsuits seeking enforcement. These typically result in settlements that include requirements for specific compliance measures, increased resource allocation to fraud prevention, regular reporting and monitoring obligations, and potentially financial penalties. Companies might also face reputational damage and increased regulatory scrutiny. Settlements often include provisions for third-party auditing to verify compliance, meaning companies must pay for independent verification of their fraud prevention efforts, creating ongoing accountability rather than one-time penalties.

Is the SCAM Act constitutional?

Yes, legal experts generally believe the SCAM Act would survive constitutional challenges. The legislation doesn't prohibit or restrict speech but instead imposes an affirmative duty of care on platforms that profit from advertising. Duties of care are common in regulation—banks have them for money laundering prevention, hospitals for patient safety, restaurants for food inspection—and have been consistently upheld. Fraud is not protected speech, giving the government clear authority to regulate it. While platforms might challenge the vagueness of the "reasonable steps" standard or argue for specific carve-outs, these challenges face an uphill battle given the established legal framework for regulating fraud.

How does the SCAM Act compare to international regulation?

The SCAM Act is narrower than some international approaches like the EU's Digital Services Act, which imposes sweeping requirements on platform operation and content moderation. However, it's similar in principle to the UK's Online Safety Bill, which includes a duty of care for platforms. The SCAM Act's focus on a specific, measurable harm—fraud—makes it more achievable politically and legally than broader regulatory frameworks. This narrow approach has tradeoffs: it's easier to pass and defend, but it addresses only one category of platform harms, leaving other issues like misinformation or privacy to be addressed through separate legislation.

What's the timeline for the SCAM Act?

The SCAM Act was introduced in early 2025 and is building bipartisan support, but bills of this type typically take time to reach a vote. Similar legislation, like bills regulating robocalls and junk text messaging, have taken years to pass but often ultimately succeeded. The legislative process involves committee markup, potential modifications, passage through both chambers, and presidential signature. During negotiations, the bill might be modified, with potential refinements to definitions or enforcement mechanisms. Given the bipartisan sponsorship and political resonance of consumer fraud protection, the legislation is likely to become law in some form within 12-24 months, though perhaps with modifications from its original introduction.

How would the SCAM Act affect legitimate advertisers?

Legitimate advertisers might experience some short-term friction from stricter verification requirements and potential review delays. However, the long-term effects are likely positive: a cleaner advertising ecosystem with less fraud-driven inflation in ad costs, improved return on advertising investment due to better-quality placements, and increased confidence that their ads reach real customers rather than fraud victims. Many legitimate advertisers already support stricter fraud prevention because they're harmed by the inflated competition from fraudulent ads. The removal of fraudulent competitors should benefit legitimate business advertising.

Can the SCAM Act eliminate fraud entirely?

No, and the legislation doesn't require platforms to eliminate fraud entirely. It requires "reasonable steps," which acknowledges that perfect fraud prevention is impossible. Some sophisticated scams will slip through. Some international scammers will find workarounds. However, reducing the volume and reach of fraud, which is what the SCAM Act aims to do, has enormous practical value. If the legislation reduces fraud losses by even 5-10 percent, that represents billions of dollars annually staying in the pockets of consumers rather than scammers. That's a meaningful achievement even if it doesn't achieve perfection.

Key Takeaways

- The SCAM Act requires platforms to take 'reasonable steps' to prevent fraudulent advertising, with FTC and state AG enforcement authority

- Meta's own estimates showed ~10% of its 2024 revenue ($16 billion) came from scam ads, revealing platforms profit knowingly from fraud

- Americans lost nearly 8.1 billion—indicating the scale of the problem the legislation targets

- The bill is bipartisan (Gallego-D/Moreno-R) because fraud affects all constituencies, giving it stronger prospects for passage than partisan tech regulation

- Legal experts believe the SCAM Act would survive constitutional challenges since fraud isn't protected speech and duties of care are established in regulation

Related Articles

- Amazon's $309M Returns Settlement: What Consumers Need to Know [2025]

- Meta's "IG is a Drug" Messages: The Addiction Trial That Could Reshape Social Media [2025]

- Apple Pay Unusual Activity Scam: How to Spot Fake Messages [2025]

- How Right-Wing Influencers Are Weaponizing Daycare Allegations [2025]

- Malwarebytes and ChatGPT: The AI Scam Detection Game-Changer [2025]

- Grok's Deepfake Problem: Why AI Keeps Generating Nonconsensual Intimate Images [2025]

![The SCAM Act Explained: How Congress Plans to Hold Big Tech Accountable for Fraudulent Ads [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/the-scam-act-explained-how-congress-plans-to-hold-big-tech-a/image-1-1770241093527.jpg)