Meta's "IG is a Drug" Messages: The Addiction Trial That Could Reshape Social Media

Something extraordinary happened in January 2026. For the first time in social media history, a major platform faced a jury trial over addiction allegations. Not a Congressional hearing where executives apologized and nothing changed. Not a regulatory investigation that dragged on for years. An actual trial with the stakes crystal clear: Meta could lose billions, and the entire industry might be forced to redesign how their platforms work.

The case centers on a 19-year-old called K. G. M. who joined Instagram at 11 and watched YouTube since age 6. By her teenage years, she was battling depression, anxiety, and self-harm. She claims social media companies deliberately designed their platforms to trap her. And here's where it gets interesting: internal company messages support her argument in ways that would make any juror squirm.

One Meta employee wrote in a leaked internal discussion: "oh my gosh yall IG is a drug." That's not speculation. That's not a critic's opinion. That's someone working inside Meta, at the company that created Instagram, describing their own product using drug addiction language. Other unsealed documents showed Meta executives discussing how "teens can't switch off from Instagram even if they want to." Another internal memo outlined plans to keep kids engaged "for life," even while internal research revealed Facebook use correlated with lower well-being among young users.

These aren't hypothetical harms anymore. They're evidence that could reshape an entire industry.

Why This Trial Matters More Than Congress Ever Did

Social media companies have survived Congressional grilling for years. Mark Zuckerberg sat before Congress. TikTok's CEO answered questions from lawmakers. Facebook took regulatory heat after the Cambridge Analytica scandal. In each case, there were apologies, promises of change, and then... very little actually changed. The platforms stayed profitable. The engagement metrics kept climbing. The features that allegedly cause harm remained.

This trial is different because a jury isn't interested in PR narratives. They're examining evidence. They're hearing from people who actually experienced harm. And crucially, they're looking at what companies said in private versus what they said publicly. That gap matters enormously.

The financial stakes explain why. A loss could cost Meta billions in damages. Not millions. Billions. That's the kind of number that forces actual product changes because shareholders start getting nervous. When it's potential punitive damages on top of compensatory damages, companies start seriously considering whether their business model survives the verdict.

Moreover, K. G. M.'s case sets precedent. There are over 1,000 similar lawsuits sitting in the pipeline, most treating this case as a "bellwether," meaning if K. G. M. wins, dozens of similar cases probably win too. If she loses, those cases probably collapse. So the stakes aren't just about one 19-year-old's medical bills. They're about whether social media companies can ever be held liable for deliberately addictive product design.

That's why TikTok settled hours before the trial started. Snapchat settled days before. Both companies looked at the evidence and apparently decided that betting against a jury wasn't worth it. YouTube and Meta stayed in the fight, but the fact that competitors blinked first tells you something about how their legal teams assessed the situation.

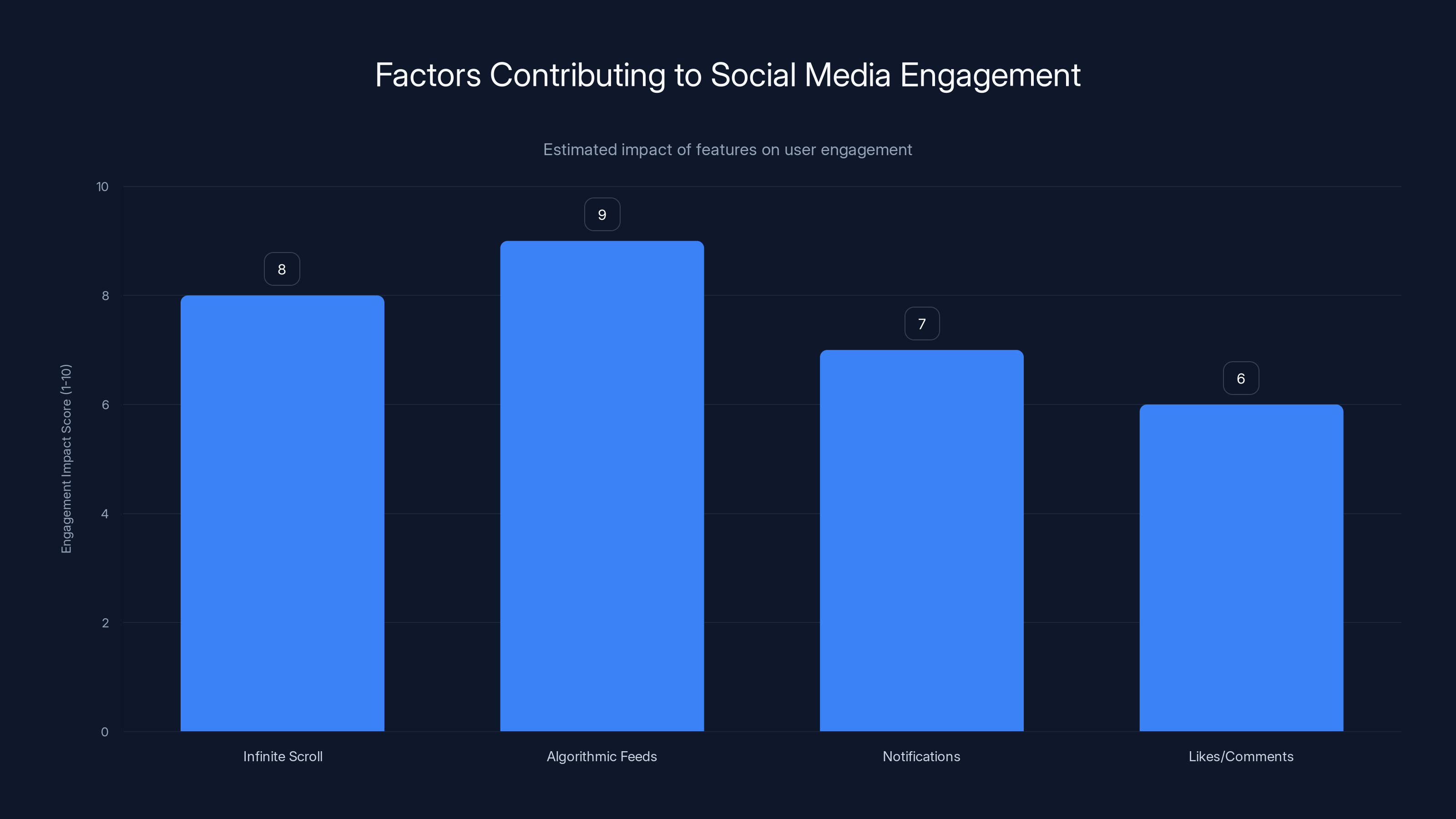

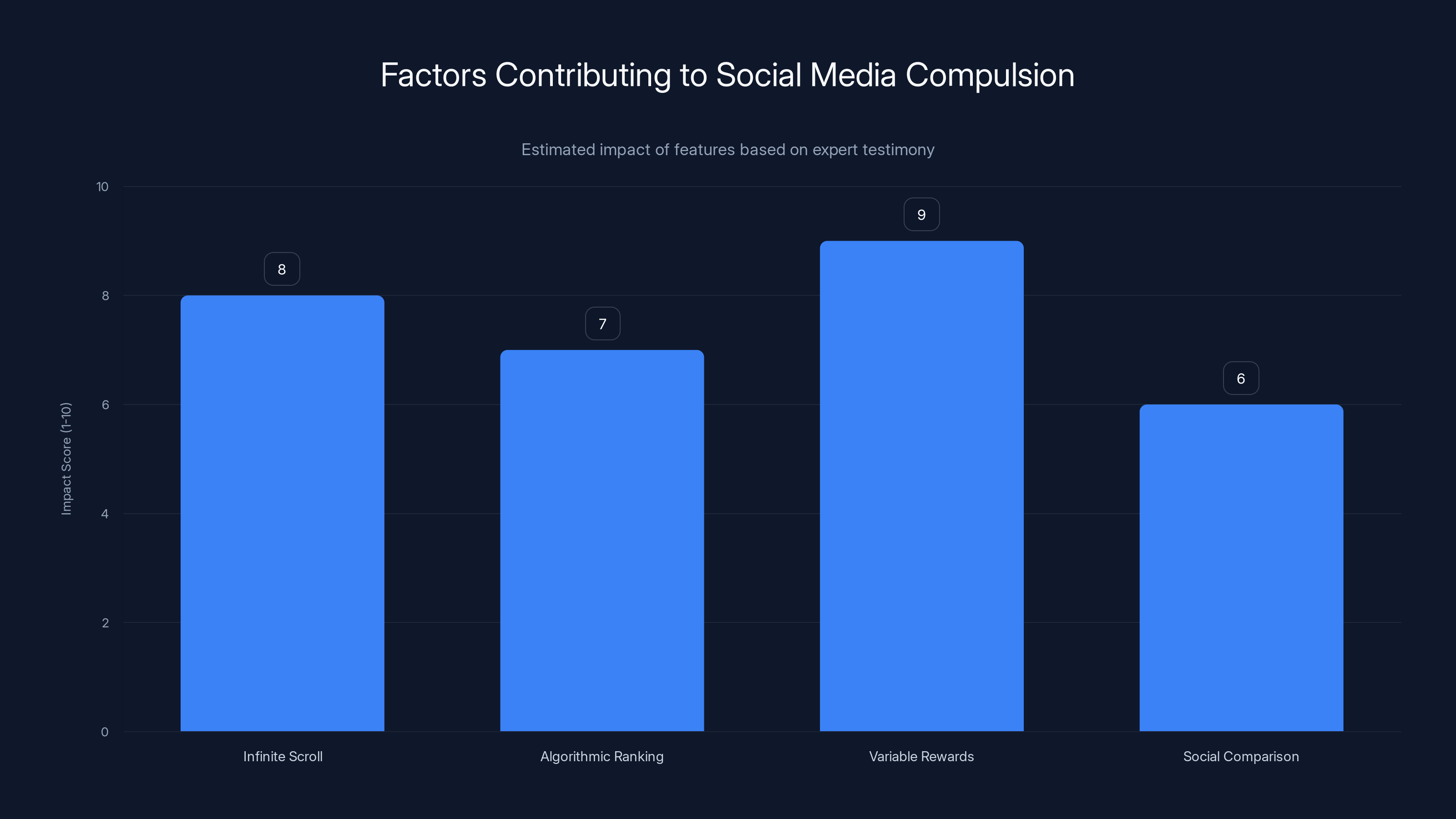

Infinite scroll and algorithmic feeds are estimated to have the highest impact on user engagement, suggesting deliberate design choices to maximize time spent on platforms. Estimated data.

The Addiction Evidence: When Internal Research Becomes a Problem

Here's what makes the internal documents so damaging: they show intent. Social media platforms have always claimed they're just neutral platforms where users choose what to engage with. But the unsealed messages suggest something else entirely. Meta's own documents show executives discussing how to manipulate teenager behavior deliberately.

One key document revealed that Mark Zuckerberg decided in 2017 that Meta's top priority was getting teenagers "locked in" to using the company's family of apps. That's not language about engagement or retention. That's language about addiction. The company wasn't trying to build products teenagers liked. It was trying to build products teenagers couldn't escape from.

The next year, an internal Facebook memo discussed letting younger users access a private mode inspired by "finstas," the fake Instagram accounts teenagers created to escape their public personas. The memo included a disturbing line: an "internal discussion on how to counter the narrative that Facebook is bad for youth and admission that internal data shows that Facebook use is correlated with lower well-being." Let that sink in. Meta's own researchers found that their platform hurt young people's mental health. And the internal conversation wasn't about fixing the problem. It was about how to convince the public the problem didn't exist.

That's the difference between legal liability and innocent business competition. It's the difference between saying "we created a product people like" and saying "we created a product that we know is harmful, and we're covering it up while we continue promoting it to kids."

Google's internal documents revealed something equally damaging. A 2020 memo outlined the company's plan to keep children engaged "for life," despite YouTube's own research showing that young users exposed to extended engagement features experienced worse mental health outcomes. The phrase "for life" is important here because it suggests the goal isn't serving the user. It's capturing them indefinitely.

These documents matter because they transform the legal question from "Did your platform cause harm?" to "Did you know your platform caused harm and hide it while continuing to promote it?" The first question is complicated. It requires proving causation, which is notoriously difficult in mental health research. The second question is straightforward. Either the company knew or it didn't.

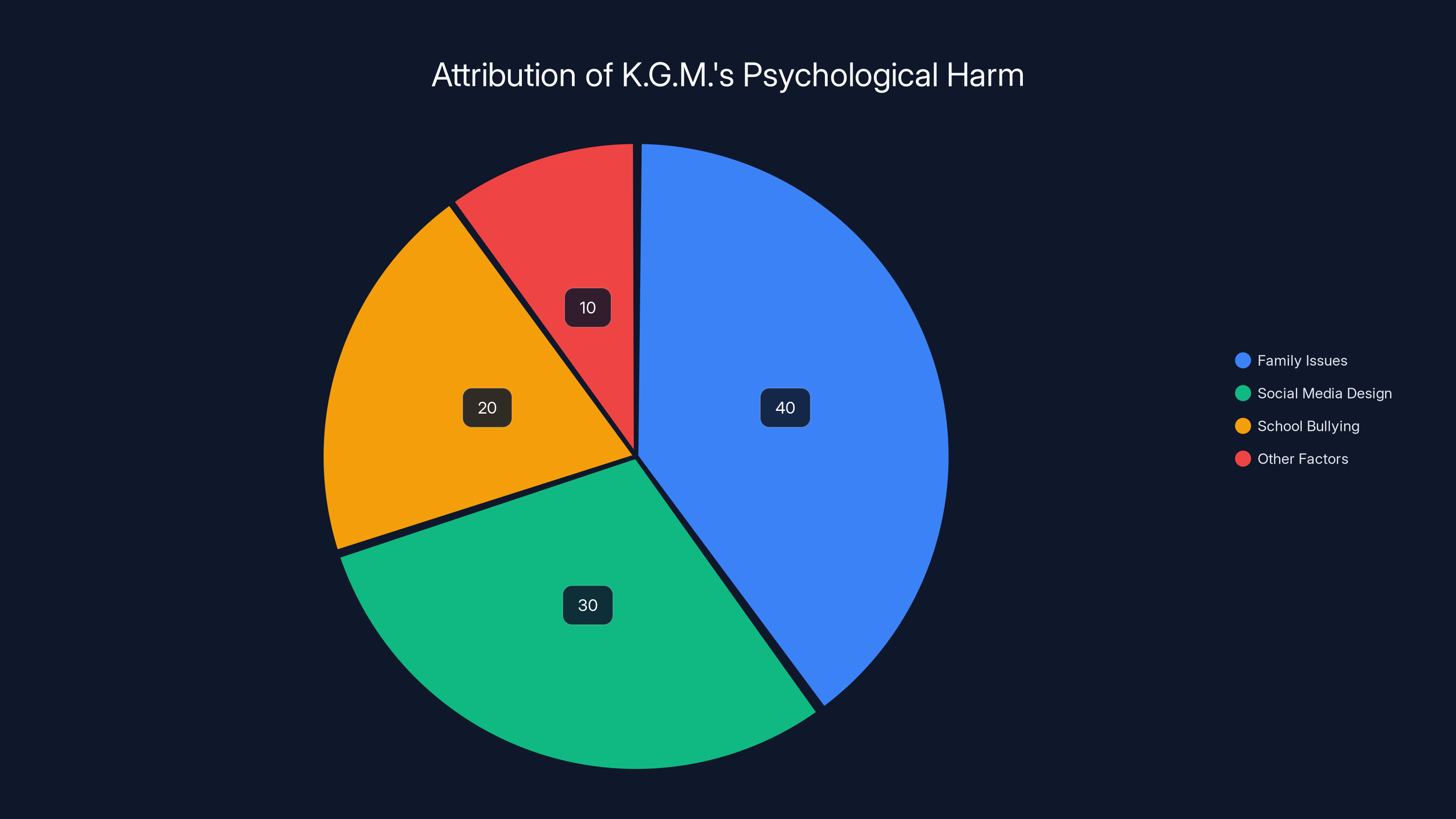

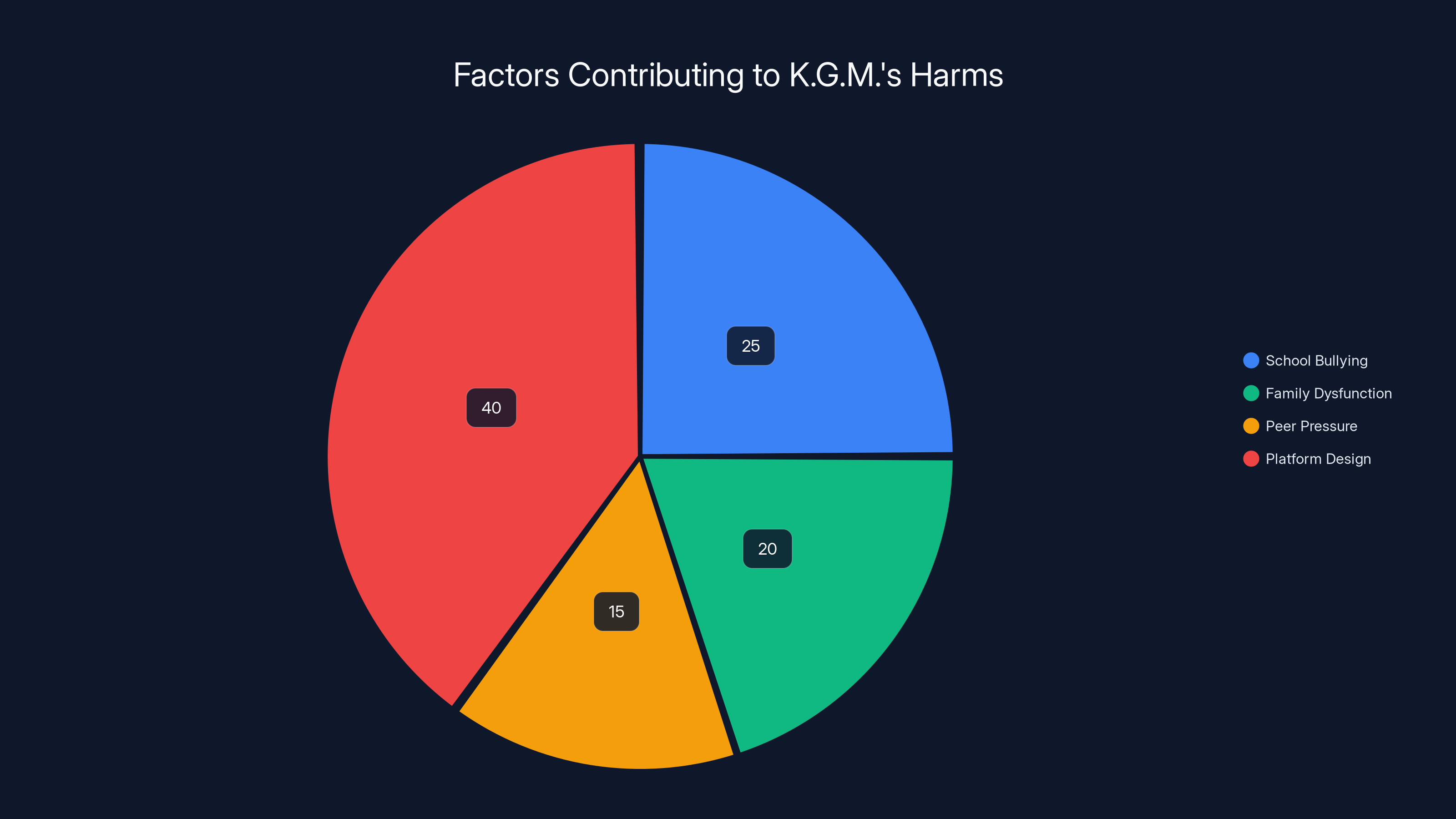

Estimated data suggests that family issues contribute 40% to K.G.M.'s depression, while social media design accounts for 30%. School bullying and other factors make up the rest.

The Addictive Design Features That Drove K. G. M.'s Case

K. G. M.'s lawsuit focuses on specific features that platforms deliberately designed to maximize engagement at the expense of user well-being. These aren't subtle. They're engineered patterns that anyone who's used social media for more than five minutes recognizes.

Infinite scroll is the obvious one. Instead of reaching the bottom of a feed, the content just keeps loading. Technically, users can stop scrolling anytime. Practically, the interface removes the natural stopping point. Research from psychology and neuroscience suggests that visual completion creates a feeling of accomplishment. Infinite scroll removes that feeling. You stop when you hit social fatigue, which takes longer than hitting a page break.

Autoplay is another example. When you finish watching one YouTube video, the next one starts automatically. You're not clicking "play" anymore. You're actively deciding to stop watching. That's a much higher friction point than clicking a link to watch something. So users watch more videos than they otherwise would. Netflix uses autoplay the same way. The difference is Netflix is trying to keep people entertained while they have time. YouTube has explicitly designed features to extend watch time during periods when young users would normally do homework, sleep, or interact with friends.

Like counters and notification badges trigger dopamine feedback loops. That's not accidental psychology. It's deliberate. The companies employ neuroscientists and psychologists specifically to understand how to create compulsive usage patterns. These aren't engineers taking a random guess at what engages users. These are teams with dedicated budgets designing systems to exploit psychological vulnerabilities.

The algorithm amplification is the most subtle and most powerful. Platforms don't just show you chronological feeds anymore. They predict what will keep you engaged longest and promote that content. For vulnerable teenagers dealing with body image issues or social anxiety, the algorithm learns this and keeps feeding them content that triggers those vulnerabilities because that content generates engagement. A teenager concerned about their appearance gets shown more fitness content, dieting content, or curated highlight reels that worsen those concerns. This drives engagement because the teenager keeps scrolling to find content that makes them feel better (or sometimes worse, which still drives engagement).

K. G. M.'s legal team needs to prove that these specific features caused her specific harms. That's the challenge the lawsuit faces. A jury understands that if you design a slot machine to be addictive, you're responsible for people who become addicted. But proving that Instagram's algorithmic feed is essentially a slot machine for teenage dopamine requires explaining complex product design and psychology in a way that makes intuitive sense to twelve people who may or may not understand how social media works.

The Addiction Definition Problem

Here's where K. G. M.'s case hits a real barrier: social media addiction isn't officially recognized in the DSM-5, the diagnostic manual psychiatrists use. There's Internet Gaming Disorder, which the manual lists as a condition warranting further research. But there's no official diagnosis of "social media addiction" or "Instagram addiction" specifically.

This matters because platforms' lawyers will argue that if addiction isn't a recognized medical condition, then K. G. M. wasn't actually addicted. She was just a teenager who used social media a lot, which is normal. Her other problems—family troubles, school stress, bullying—are what actually caused her depression and anxiety. Social media was just the background noise.

The science doesn't fully support this line of argument, but it's not completely wrong either. Research shows correlation between heavy social media use and poor mental health outcomes in teenagers. But correlation isn't causation. You can't draw a clean line from "teenage girl uses Instagram" to "teenage girl develops depression." Some girls use Instagram heavily and maintain good mental health. Others use it barely and still struggle.

However, the research also shows that the features platforms deliberately designed to maximize engagement—the infinite scroll, the algorithmic feeds, the notification systems—do increase usage time, and increased usage time is correlated with increased mental health symptoms. So it's not that Instagram caused K. G. M.'s depression. It's that Meta deliberately engineered Instagram to maximize K. G. M.'s engagement, knowing that increased engagement among vulnerable teenagers is associated with psychological harm.

This is actually more damaging legally than simple causation would be. Because it suggests negligence. Meta didn't just create a platform. It specifically designed the platform to maximize engagement from teenagers while possessing internal research showing that increased engagement among teenagers correlates with harm. That's a different liability question.

Tamar Mendelson, a professor at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, pointed out that the actual causal mechanism is still unclear. Does Instagram cause depression? Or do depressed teenagers use Instagram more heavily? The research shows both things happen. But what Meta's internal documents show is that the company designed features to increase usage specifically among teenagers, without adequately warning parents or teens about the risks, even though Meta's own research suggested those risks were real.

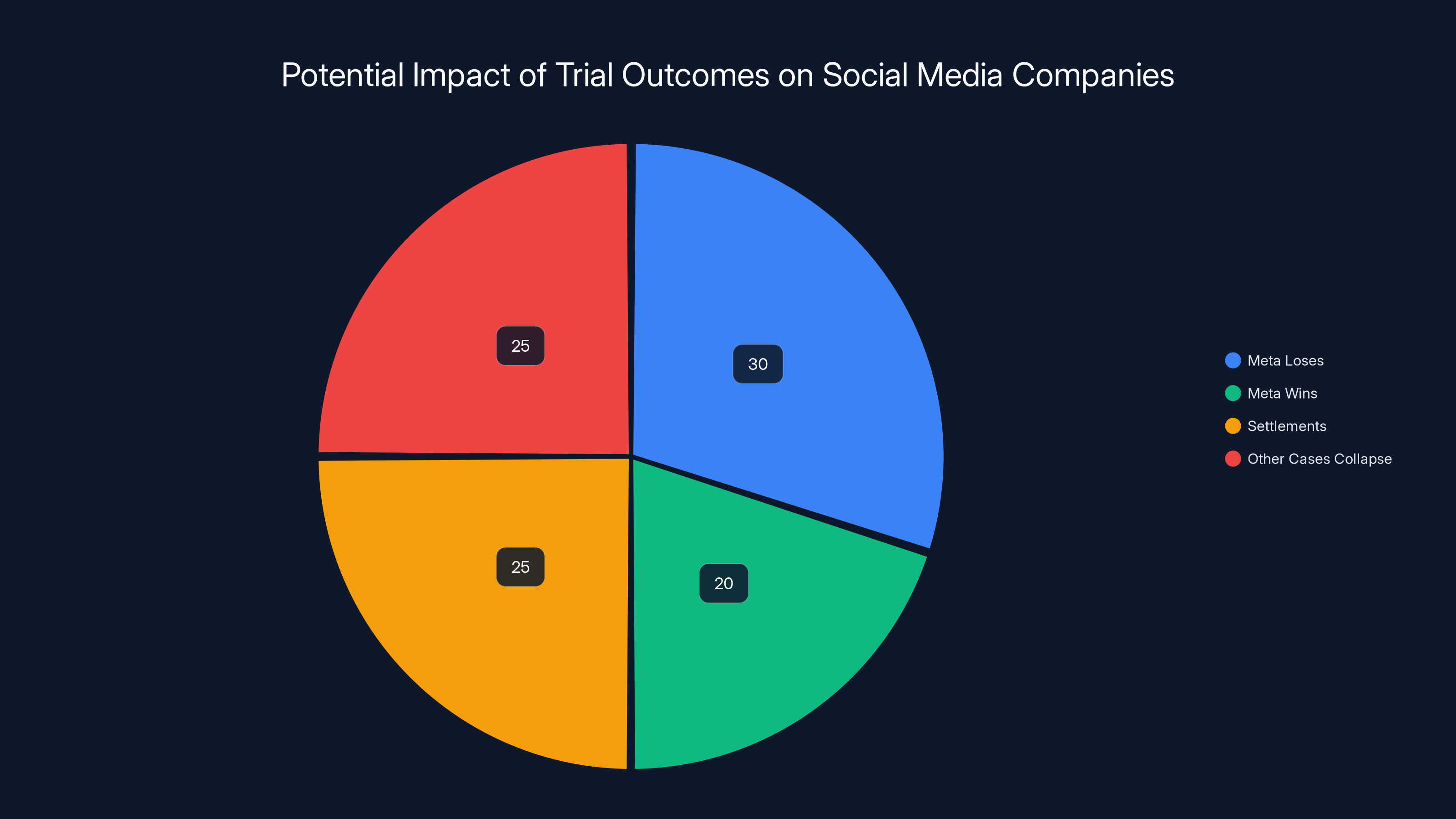

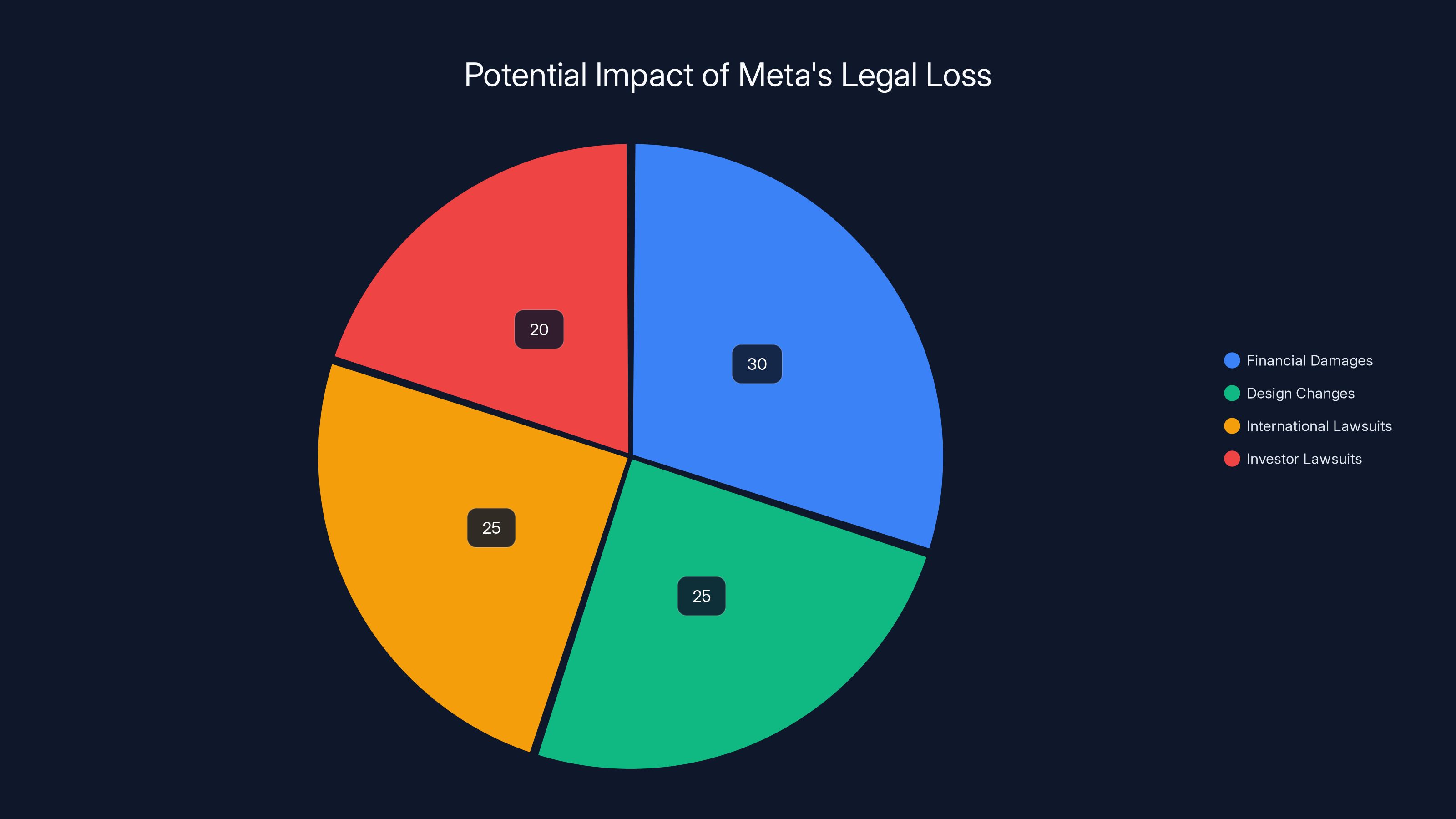

Estimated data: A loss for Meta could lead to billions in damages and set a precedent affecting over 1,000 similar lawsuits. Settlements by TikTok and Snapchat indicate the high stakes involved.

The Defense Strategy: Blame Everything Else

Meta and YouTube's defense is straightforward: K. G. M.'s harms came from sources other than product design. School bullying. Family dysfunction. Peer pressure. These external factors caused her depression and anxiety, not algorithmic feeds.

The platforms also lean heavily on Section 230, the law that shields internet companies from liability for user-generated content. They argue that even if their design features encouraged engagement, they're not responsible for what content users encountered. That's a First Amendment argument: the companies are protected from liability for speech, even if their design features amplified certain speech.

But Judge Carolyn B. Kuhl, the judge overseeing K. G. M.'s case, ruled that this defense doesn't work when the lawsuit focuses on design features rather than content. K. G. M. isn't suing because she saw bullying comments on Instagram. She's suing because Instagram's infinite scroll and algorithmic feed deliberately kept her engaged longer than she otherwise would have been, exposing her to more content generally, and doing so in a way that platforms designed knowing it would drive engagement and harm.

That ruling was the key moment in the case. It meant the trial could proceed. It meant a jury would get to hear evidence and decide whether Meta deliberately designed harmful products. If Meta had won on summary judgment, the case would have been dismissed entirely before trial.

The defense will also argue that responsibility for online safety falls to parents, not platforms. Parents should monitor their children's internet usage. Parents should set restrictions. Parents should talk to their kids about social media risks. This argument has some surface appeal—parents should play an active role in supervising their teenagers. But it breaks down when you consider that most teenagers can circumvent parental controls relatively easily, that platforms deliberately design features to be appealing despite parental concerns, and that Meta's own internal documents show the company was specifically trying to hook teenagers in ways that parents wouldn't notice.

TikTok and Snapchat's Settlements: A Huge Signal

The fact that TikTok and Snapchat settled just before and just after the trial started is a massive signal about how these companies viewed their legal exposure. TikTok announced its settlement on Tuesday, literally hours before jury selection began. Snapchat settled the week before.

We don't know the settlement amounts because they're confidential. But settlements happen when companies decide that losing at trial would be worse than settling. TikTok's move is particularly telling because TikTok has faced relentless criticism from U. S. lawmakers and has been threatened with a ban. If any platform had political cover to take a hard line against these lawsuits, it would be TikTok, which might face regulatory action regardless of trial outcomes.

Instead, TikTok chose to settle. That suggests TikTok's legal team looked at the evidence—the internal messages, the expert testimony about addictive design, the testimony from K. G. M. about how the platform affected her life—and decided the risk of losing was unacceptable.

Snapchat's settlement is interesting because Snapchat has faced other addiction-related lawsuits from school districts, which the company hasn't settled. This suggests that Snapchat made a strategic choice about which lawsuits posed the biggest threat. The individual injury lawsuit brought by K. G. M. posed a bigger threat than the school district suits, probably because individual damages can be multiplied across thousands of similar cases, whereas school district suits have different legal mechanics.

Meta and YouTube clearly did the opposite calculation. They looked at the evidence and decided to take their chances with a jury. This is either bold or reckless depending on how the trial goes. If they win, they've beaten back thousands of similar lawsuits. If they lose, they're looking at billions in exposure.

A potential legal loss for Meta could lead to significant financial damages, enforce design changes, inspire international lawsuits, and trigger investor lawsuits. Estimated data.

How K. G. M.'s Case Could Win

Mathew Bergman, K. G. M.'s attorney and founder of the Social Media Victims Law Center, has been explicit about the strategy: make K. G. M.'s story clear and compelling, then connect that story to Meta and YouTube's deliberate design choices.

Bergman told The Washington Post: "She is going to be able to explain in a very real sense what social media did to her over the course of her life and how in so many ways it robbed her of her childhood and her adolescence." This is the human element. K. G. M. joined Instagram at 11. By her teenage years, she was struggling with depression, anxiety, and self-harm. These aren't abstract harms. This is a person whose development was disrupted.

Then the legal team connects this story to Meta's product design. They show the internal documents where Meta employees describe Instagram as a drug. They present expert testimony about how the features Meta designed—infinite scroll, algorithmic ranking, notification systems—deliberately maximize engagement. They explain the psychology of compulsive usage patterns. They show Meta's own research indicating that increased Instagram usage among teenagers correlates with decreased well-being.

The jury's job becomes: Did Meta deliberately design features that it knew would maximize K. G. M.'s engagement? Yes, the evidence shows that. Did Meta know that maximizing engagement among vulnerable teenagers could cause psychological harm? Yes, Meta's internal research shows that. So did Meta bear responsibility for the harm that resulted? That's the question for the jury.

Where K. G. M.'s case might struggle is in proving that Meta's specific design choices caused her specific harms, rather than school bullying or family problems causing those harms. Clay Calvert, a technology policy expert at the American Enterprise Institute, noted that the legal team will need to carefully "parcel out" the harm attribution. Maybe 40% of K. G. M.'s depression stems from family issues, 30% from school bullying, and 30% from social media. The jury would then decide what portion Meta should be liable for.

But the internal documents change this calculation. If Meta deliberately designed Instagram to trap K. G. M. while knowing this could cause harm, Meta bears some responsibility for making K. G. M. more vulnerable to those other harms. The depression and anxiety that resulted from intensive Instagram use may have made her more susceptible to bullying or family stress.

What a Meta Loss Could Mean: Industry Reshaping

If K. G. M. wins, the consequences ripple across the entire industry. First, the immediate financial hit. A verdict finding Meta liable for K. G. M.'s harms could result in compensatory damages covering her medical costs and pain and suffering, potentially in the millions. More consequentially, the jury might award punitive damages intended to punish Meta for its behavior and deter future harm. Punitive damages are multiples of compensatory damages, sometimes 10x or more, depending on how egregious the jury finds the conduct.

Meta faces a similar lawsuit from dozens of state attorneys general on the same addiction claims. If K. G. M. wins, those state cases become much stronger. A jury verdict establishes precedent. It shows that addiction claims have merit, that design features can constitute negligence, and that internal company documents demonstrating knowledge of harm are admissible and persuasive.

Second, the precedent forces design changes. Even without legislative action, a jury verdict creates liability exposure for certain features. Companies would face pressure to remove infinite scroll, disable autoplay by default, reduce algorithmic feed optimization, and make engagement-limiting features more prominent. These changes wouldn't destroy social media, but they would significantly reduce engagement metrics and advertising opportunities, because the whole point of these features is to maximize engagement.

Third, the verdict would likely inspire copycat lawsuits internationally. Europe already regulates social media more aggressively through the Digital Services Act. A U. S. jury verdict would strengthen the hand of international regulators pushing for stricter rules. You'd see similar cases in the UK, Canada, Australia, and other countries with strong product liability traditions.

Fourth, an investor lawsuit becomes plausible. If a jury finds that Meta knowingly designed harmful products, Meta shareholders could sue the company for failing to disclose these risks. The company might have known these design practices created long-term liability exposure, but didn't adequately warn shareholders. That's securities fraud. Meta's stock could face significant downward pressure if major institutional investors start questioning the sustainability of the engagement-focused business model.

For YouTube, a loss means Google faces the same exposure. Google's advertising business is built on engagement metrics. YouTube's aggressive autoplay and recommendation algorithms are core to that business. Changing those features would reduce Google's most profitable division.

The broader point: a K. G. M. victory doesn't just hurt Meta and YouTube. It fundamentally challenges the business model that all social media companies rely on. Platforms make money by selling advertising, which requires attention. The more engagement, the more valuable the advertising. Features that maximize engagement are therefore core to the business model. But if those features create legal liability, companies have to choose between profit and legal safety.

Estimated data suggests that variable rewards have the highest impact on compulsive usage patterns, followed closely by infinite scroll and algorithmic ranking.

The Expert Witness Challenge

One reason the platforms settled might relate to expert witness testimony. K. G. M.'s legal team is expected to present experts in psychology, neuroscience, and addiction who can explain how features like infinite scroll and algorithmic ranking create compulsive usage patterns.

Meta's defense experts will argue that the research on social media addiction is unclear, that causation hasn't been proven, and that other factors drove K. G. M.'s harms. But explaining why compulsive usage patterns exist while claiming the platforms didn't deliberately design them to be compulsive is challenging. It's the software equivalent of saying "yes, we engineered a slot machine to be addictive, but you can't prove slot machines actually cause gambling addiction."

The research actually supports K. G. M. here. Neuroscience shows that infinite scroll triggers variable reward patterns—the same neurological mechanism that makes slot machines addictive. Variable rewards (you don't know when you'll see a great post) create stronger compulsion than consistent rewards (you always get the same thing). Platforms deliberately implemented variable reward systems because they understood this neuroscience.

Similarly, algorithmic feeds that prioritize content most likely to drive engagement create feedback loops. If you're vulnerable to social comparison, the algorithm learns this and shows you more comparison content because it drives engagement. This isn't a bug. It's the intentional outcome of the algorithm.

Explaining this to a jury is easier than Meta's defense team might hope, because jurors have used social media themselves. Most people intuitively understand that apps are designed to be hard to put down. The platforms' denial of intentional design feels disingenuous when the internal documents explicitly discuss making products people "can't switch off from."

The Parent Blame Deflection

Meta's defense will emphasize parental responsibility. Parents should monitor their children. Parents should set usage limits. Parents should have conversations about social media risks. All of this is true. But it's also a deflection from the real question: Did Meta deliberately design addictive products while knowing they could cause harm?

The parent blame argument also ignores what platforms know about their users. Meta possesses detailed data about every user's age, location, and behavior patterns. The company could implement mandatory parental controls for accounts of teenagers under 16. Instagram could require parental approval for accounts belonging to users under 13. These features could be default, not optional.

They're not default because defaults drive usage. Making features "opt-in" instead of "opt-out" dramatically reduces adoption. Meta understands this because Meta conducts A/B testing on interface changes constantly. If the company wanted parents supervising teenager accounts, the company would make supervision the default. Instead, supervision is hidden in settings that most parents never find.

This is the difference between enabling parental responsibility and enabling parental responsibility. Meta has the technical capability to make parental oversight easy and automatic. The company chooses not to because it would reduce engagement metrics. That's negligence, not neutrality.

Estimated data suggests platform design features may contribute significantly to user engagement and potential harm, alongside other external factors.

The International Regulatory Response

Even if Meta and YouTube win the K. G. M. case, regulators globally are moving toward stricter controls on social media products targeting teenagers. The European Union's Digital Services Act already requires platforms to assess and minimize risks to minors. Australia recently passed legislation requiring age verification and parental consent for teenage social media accounts.

These regulations exist regardless of litigation outcomes. But a jury verdict finding Meta liable for addictive design would accelerate regulatory action. Regulators would point to the verdict as evidence that the platforms' self-regulation is insufficient. That would lead to faster, stricter rules requiring design changes.

The UK's Online Safety Bill, scheduled for enforcement in 2025, includes provisions requiring platforms to consider user well-being, not just legal compliance. This moves the needle from "is this illegal?" to "is this harmful?" and requires platforms to act on harms even if they're not illegal. A jury verdict in K. G. M.'s case would strengthen arguments that certain design features are harmful and should be restricted.

China's approach is instructive. Chinese platforms face strict government regulation on engagement-optimizing features. Algorithms are audited. Recommendation systems must include safety criteria. The result is that Douyin (TikTok's Chinese version) shows less engagement-maximizing content than the international version of TikTok. This suggests that regulated platforms can operate profitably while using less aggressive engagement tactics. It's not a question of whether the business model survives with restrictions. It's a question of how much profit platforms are willing to sacrifice for safety and legal compliance.

What About Freedom of Speech?

Meta and YouTube will argue that restricting how they design their platforms violates their First Amendment rights. The platforms are engaged in speech (the content they host) and editorial discretion (deciding what to show to whom). Forcing them to change their algorithms or limit engagement-maximizing features violates this protected speech.

But the First Amendment doesn't protect conduct that violates other laws. If Meta's design choices constitute negligent product design that harms vulnerable users, the First Amendment doesn't shield that conduct. Courts have long held that the First Amendment doesn't protect fraudulent speech, deceptive speech, or speech connected to illegal conduct. If Meta deliberately designed harmful products, the design itself might be subject to product liability law.

Moreover, the First Amendment protects against government censorship, not private liability. A jury verdict finding Meta liable doesn't violate Meta's free speech rights. Meta would be free to continue operating however it wants. The company would just face financial consequences for doing so. That's not suppression. That's accountability.

The platforms will make these arguments because they have nothing to lose. But they're not strong arguments. Courts have increasingly rejected the idea that the First Amendment provides blanket immunity for technology companies' product design choices.

The Timeline and Next Steps

The trial is already underway. Jury selection happened in January 2026. The trial is expected to last several weeks. Mark Zuckerberg was subpoenaed to testify, along with other Meta executives. YouTube executives are expected to testify for Google.

A verdict could come in weeks or months depending on trial length and jury deliberation time. If the jury finds for K. G. M., the case likely appeals to higher courts. Appeals on novel questions like this often take years. But the precedent will exist even during appeals.

The bigger timeline is the broader litigation wave. Over 1,000 addiction lawsuits are pending. If K. G. M. wins, many will move toward trial quickly. If K. G. M. loses, many will be dismissed. The lawsuit landscape for social media is about to shift significantly based on this one verdict.

Meanwhile, legislators are watching closely. Federal legislation on social media regulation has stalled repeatedly in Congress, but a major jury verdict changes the political calculation. If a jury decides that Meta knowingly created harmful products, lawmakers face pressure to pass strict regulations quickly, rather than letting liability litigation drag on for years.

What K. G. M. Is Seeking Beyond Money

K. G. M. wants damages to compensate for her medical bills and pain and suffering. But she's also seeking a mandatory court order requiring Meta to display prominent safety warnings to parents and users. This requirement would essentially force Meta to explicitly tell parents and teenagers that the platform is designed to maximize engagement in ways that could be psychologically harmful.

This is actually more consequential than the financial damages. A safety warning requirement changes how the platform presents itself publicly. Parents would see these warnings. Teenagers would see them. Media coverage of the case will amplify the warnings. Over time, the warnings shape social perception of the product.

This happened with cigarettes. After the Surgeon General's warning requirement, cigarette sales didn't immediately collapse, but social perception of smoking shifted. Younger generations saw smoking as dangerous because warnings were ubiquitous. A similar dynamic could apply to social media if courts impose prominent warning requirements.

Meta would absolutely appeal any ruling requiring safety warnings because the warnings directly conflict with the company's brand messaging. Meta wants people to see Instagram as a fun, social, positive place. Mandatory warnings saying "this product is designed to be addictive and may cause depression and anxiety" would undermine that brand positioning.

The Broader Addiction Conversation

Apart from the legal questions, K. G. M.'s case raises fundamental questions about technology design and responsibility. When is a product addictive by design versus addictive by nature? Is engagement always wrong, or only when it targets vulnerable populations?

Video games are designed to be engaging. Streaming services recommend content to maximize watch time. Even email is designed with notifications that drive engagement. Where do you draw the line on what's acceptable product design and what crosses into negligence or harm?

The answer probably depends on vulnerable populations. Products can be engaging for most users without causing harm. But if a product is deliberately designed to maximize engagement specifically among people with diagnosed mental illness or emotional vulnerabilities, that's a different question. It's the difference between making a product enjoyable and making a product that exploits psychological vulnerabilities.

Meta's documents suggest the company did exactly this. It designed Instagram to maximize engagement among teenagers generally, knowing that some teenage users face mental health challenges and are more vulnerable to compulsive engagement. That's not a failing of the product. That's a deliberate choice to optimize engagement even among vulnerable users.

This case might establish a principle that technology companies bear some responsibility for how their products affect vulnerable populations, not just whether the products are technically legal or whether parental supervision is theoretically possible.

Implications for Artificial Intelligence and Recommendation Systems

An interesting angle emerging from K. G. M.'s case relates to how AI algorithms amplify engagement. Modern recommendation systems don't just show popular content. They predict what specific users will engage with based on behavior patterns and use reinforcement learning to improve predictions.

For a vulnerable teenager, this could mean the algorithm learns their vulnerabilities and optimizes content delivery around those vulnerabilities. A teen with body image concerns gets shown more content about fitness or beauty. A teen with social anxiety gets shown content about social situations. The algorithm isn't making moral judgments. It's maximizing engagement by showing content most likely to drive user interaction.

This creates a feedback loop where algorithms effectively exploit user vulnerabilities at scale. It's automated psychological manipulation. K. G. M.'s case touches on this but doesn't fully explore how AI amplifies the addiction risk.

Future cases will probably focus more directly on algorithmic recommendation systems. How much responsibility do companies bear for what their AI systems recommend? If the AI system learns to exploit vulnerabilities, is that a design failure or a feature? These questions will likely dominate the next wave of social media litigation.

Historical Precedent: Lessons from Tobacco, Opioids, and Guns

Product liability law has precedent for holding companies responsible for designing products that they know cause harm. Tobacco companies faced massive liability after research proved the companies knew their products caused cancer but marketed them anyway. Pharmaceutical companies faced liability for designing opioid medications with addictive properties and marketing them for chronic pain despite knowing the addiction risk.

These cases took years to litigate and years more to appeals. But they established that companies can't hide behind "user choice" arguments when they've deliberately designed harmful products and failed to disclose risks.

K. G. M.'s case follows the same pattern. Meta designed features it knew would maximize engagement among teenagers. Meta's internal research suggested increased engagement correlated with harm. Meta didn't adequately disclose these risks to users or parents. So Meta bears legal responsibility for the resulting harm.

The tobacco and opioid precedents suggest that Meta faces significant liability exposure. But they also suggest that even if Meta loses, the battle continues for years through appeals. The real change in those industries came from regulation and settlements, not from individual verdicts.

Where This Goes From Here

The K. G. M. trial is just the beginning. Dozens of similar cases will follow. Regulators globally are moving toward stricter controls. Investors will increasingly pressure platforms to address mental health risks. The question isn't whether social media companies will face consequences for addictive design. It's how those consequences will manifest—through litigation, regulation, or some combination of both.

Meta and YouTube staying in the fight for this trial suggests they believe the design practices are defensible, or at least that the legal risk is manageable. But the settlements from TikTok and Snapchat suggest those companies made a different calculation. They apparently decided that the cost of litigation and potential liability exceeded the benefit of defending the practices.

For parents and teenagers, the immediate question is what changes if K. G. M. wins. Will Instagram's infinite scroll disappear? Will algorithmic ranking become less aggressive? Will parental controls become easier to access? Probably not immediately. But over time, regulatory pressure and litigation exposure will force platforms to make meaningful design changes that prioritize user well-being over engagement metrics.

What seems clear is that the era of unchecked engagement optimization is ending. Social media companies spent the last decade designing products that captured and held teenage attention with ruthless efficiency. That was profitable. But it was also unsustainable legally and politically. K. G. M.'s trial might be the moment when the industry's bill comes due.

FAQ

What does "bellwether case" mean in K. G. M.'s trial?

A bellwether case is a trial that serves as a test case for larger litigation. If K. G. M. wins, it establishes legal precedent that makes thousands of similar pending lawsuits more likely to succeed. If K. G. M. loses, those cases probably collapse. The trial's outcome has outsized impact because it determines whether the basic claims—that social media deliberately designs addictive products and causes harm—can be proven in court.

Why is Meta's "IG is a drug" internal message so damaging?

The message is damaging because it shows Meta employees themselves recognized Instagram was designed to be addictive and used drug addiction language to describe the product. This undermines Meta's defense that the platform is just a neutral tool. It suggests the company knew what it was building and built it deliberately. That's the difference between negligence and intentional wrongdoing.

Can Meta defend against these claims by pointing to parental responsibility?

Parental supervision is important, but it doesn't shield Meta from liability if the company deliberately designed addictive products targeting teenagers. It's like arguing that tobacco companies aren't responsible for lung cancer because parents could have prevented kids from smoking. The company still bears responsibility if it deliberately marketed a harmful product to vulnerable populations. Meta's choices about default settings and feature accessibility show the company prioritized engagement over parental supervision capability.

How do infinite scroll and algorithmic feeds deliberately maximize engagement?

Infinite scroll removes the natural stopping point that occurs when you reach the end of a page. Algorithmic feeds predict what content will keep you engaged longest and prioritize that content. For vulnerable users, this means the algorithm learns their vulnerabilities and shows them content that exploits those vulnerabilities because it drives engagement. These features aren't accidental. They're specifically engineered based on neuroscience understanding of compulsive usage patterns.

What is Section 230 and why doesn't it protect Meta in this case?

Section 230 shields internet platforms from liability for user-generated content. It protects platforms from being sued over what users post. But K. G. M.'s lawsuit focuses on Meta's product design features, not user-generated content. The infinite scroll and algorithmic ranking are Meta's own designs, not content users created. So Section 230 doesn't apply. This distinction was crucial in Judge Kuhl's ruling allowing the case to proceed to trial.

Why did TikTok and Snapchat settle if they could have won like Meta might?

Settlement suggests those companies' legal teams assessed their risk and decided losing at trial would be worse than settling. The internal documents, expert testimony, and compelling personal story from K. G. M. apparently convinced them that a jury would likely find against them. They chose certain financial consequences (the settlement) over uncertain but potentially much larger consequences (punitive damages if a jury found them liable). Meta and YouTube apparently made the opposite calculation—that their chances at trial were worth the risk.

Could K. G. M. win but still lose on damages?

Yes. The jury could find that Meta's design was negligent and caused harm while disagreeing about how much damage Meta should pay. Alternatively, the jury could apportion responsibility, determining that 30% of K. G. M.'s harm came from Instagram, 40% from family issues, and 30% from school bullying. Meta would only be liable for its 30% share. This is why the lawsuit includes requests for punitive damages—compensatory damages might not adequately punish the conduct, so the jury should multiply the award by a factor to create real deterrence.

What happens to the other 1,000 pending addiction lawsuits after K. G. M.'s verdict?

If K. G. M. wins, most of the 1,000 cases will likely settle before trial because the precedent makes Meta's liability more likely. If K. G. M. loses, many will be dismissed. Settlement amounts would probably be much lower after a loss, because Meta could point to the verdict as evidence the claims are weak. This explains why the trial matters far beyond K. G. M.'s individual case—the verdict affects an entire category of litigation.

Could these design practices be legal but still subject to regulation?

Absolutely. Even if Meta wins at trial, regulators could still ban infinite scroll, require algorithmic transparency, mandate parental controls as default settings, or force algorithmic ranking to consider user well-being, not just engagement. The First Amendment doesn't protect conduct, only speech. If regulators decide certain design practices are harmful, they can restrict them regardless of litigation outcomes. Europe's Digital Services Act is already moving in this direction.

What role will Mark Zuckerberg's testimony play?

Zuckerberg was subpoenaed to testify about Meta's internal decisions and knowledge regarding addictive design and risks to teenagers. His testimony could be pivotal because he can either confirm that Meta deliberately designed addictive features or try to distance himself from those decisions. Either way, his testimony will likely be heavily covered by media and could significantly influence jury perception of Meta's intent. Zuckerberg's earlier Congressional testimony about Facebook being a positive force for society will be compared to the internal documents showing Meta knew about harms.

Key Takeaways

- K.G.M. trial marks the first jury trial holding major social media platforms liable for addiction, with potential billion-dollar damages and precedent for 1,000+ pending lawsuits

- Unsealed internal Meta documents showing "IG is a drug" messaging and deliberate engagement manipulation constitute evidence of negligent design intent

- TikTok and Snapchat's eleventh-hour settlements suggest legal teams assessed high liability risk, while Meta and YouTube chose to fight

- Algorithmic feeds deliberately learn and exploit user vulnerabilities to maximize engagement, creating feedback loops that disproportionately harm vulnerable teenagers

- A Meta loss would likely trigger global regulatory acceleration, investor pressure, and precedent enabling similar litigation internationally

Related Articles

- Social Media Companies' Internal Chats on Teen Engagement Revealed [2025]

- Meta Pauses Teen AI Characters: What's Changing in 2025

- Amazon's $1 Billion Returns Settlement: What Customers Need to Know [2025]

- X's Grok Deepfakes Crisis: EU Investigation & Digital Services Act [2025]

- EU Investigating Grok and X Over Illegal Deepfakes [2025]

- SEC Drops Gemini Lawsuit: What It Means for Crypto Regulation [2025]

![Meta's "IG is a Drug" Messages: The Addiction Trial That Could Reshape Social Media [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/meta-s-ig-is-a-drug-messages-the-addiction-trial-that-could-/image-1-1769539195593.jpg)