The Smart Glasses Bet: Why Every Tech Giant Is Suddenly All In

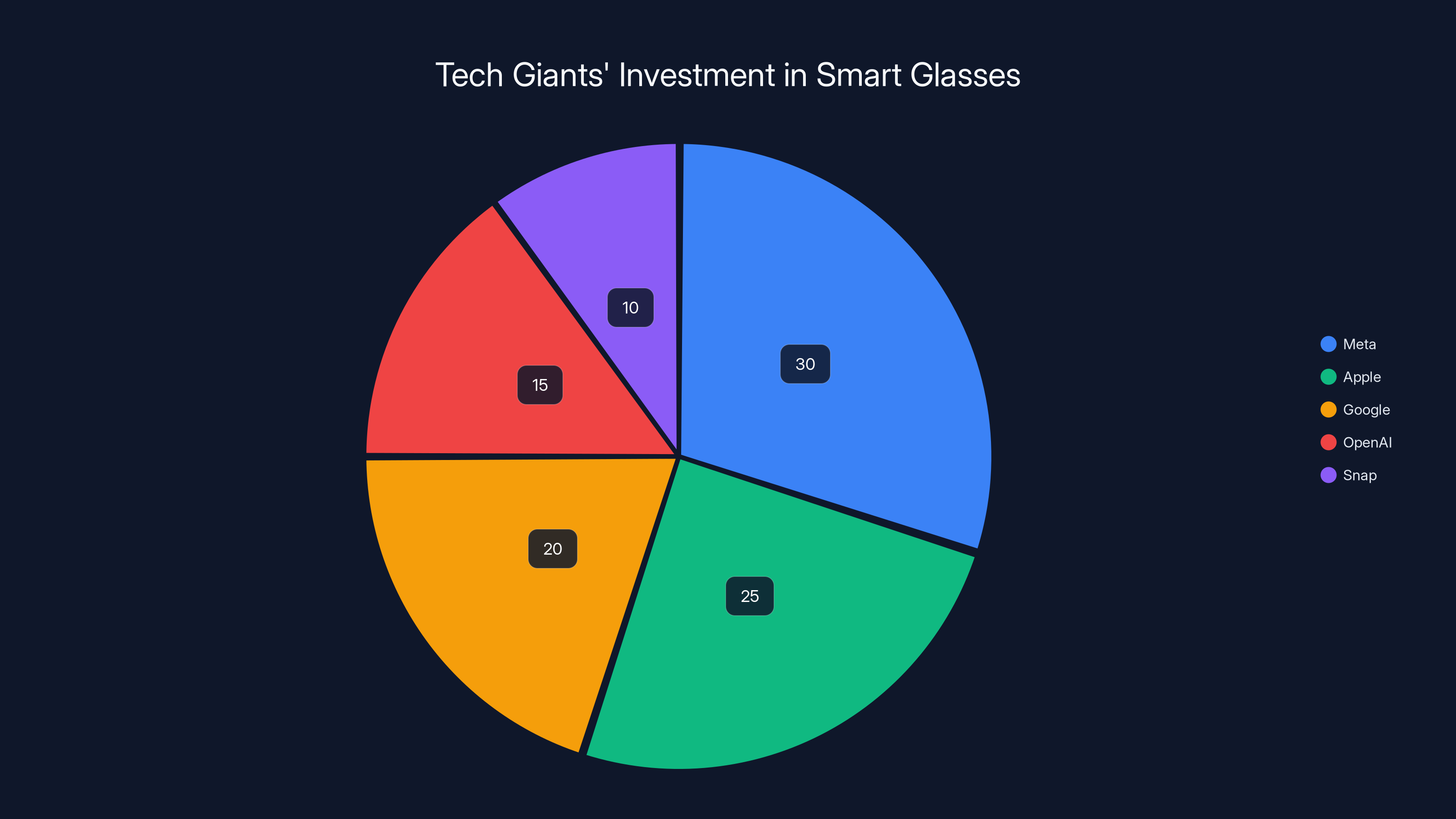

Mark Zuckerberg made a bold claim during Meta's Q4 2025 earnings call. "It's hard to imagine a world in several years where most glasses that people wear aren't AI glasses," he said. On the surface, that sounds like the kind of future-speak tech leaders throw around. But here's what's interesting: he's not alone in this belief. Apple is reportedly shifting staff away from Vision Pro headsets to focus on smart glasses. Google just signed a $150 million deal with Warby Parker to bring smart glasses to market. OpenAI is exploring AI wearables. Snap is spinning out its AR glasses division into a separate company. Even Meta's own glasses sales allegedly tripled in the past year.

Yet there's legitimate reason to take Zuckerberg's optimism with skepticism. This is the same person who spent billions betting that the metaverse would become our primary way of working and socializing. That didn't happen. The vision he painted of avatar legs and virtual offices feels like ancient history now. So when he talks about the inevitable future of smart glasses, you have to ask: is this genuine foresight, or is he seeing what he wants to see?

The difference this time is that the industry's behavior suggests something real is happening. It's not just Meta betting on this future. When Google, Apple, and OpenAI all move money and talent toward the same technology, it's worth paying attention. This isn't hype cycle noise anymore. It's capital allocation. And that usually means something.

But before we accept that smart glasses are the next smartphone, we need to understand what's actually driving this push. What problems are they solving? Why now? And what would need to change for them to become as ubiquitous as Zuckerberg claims?

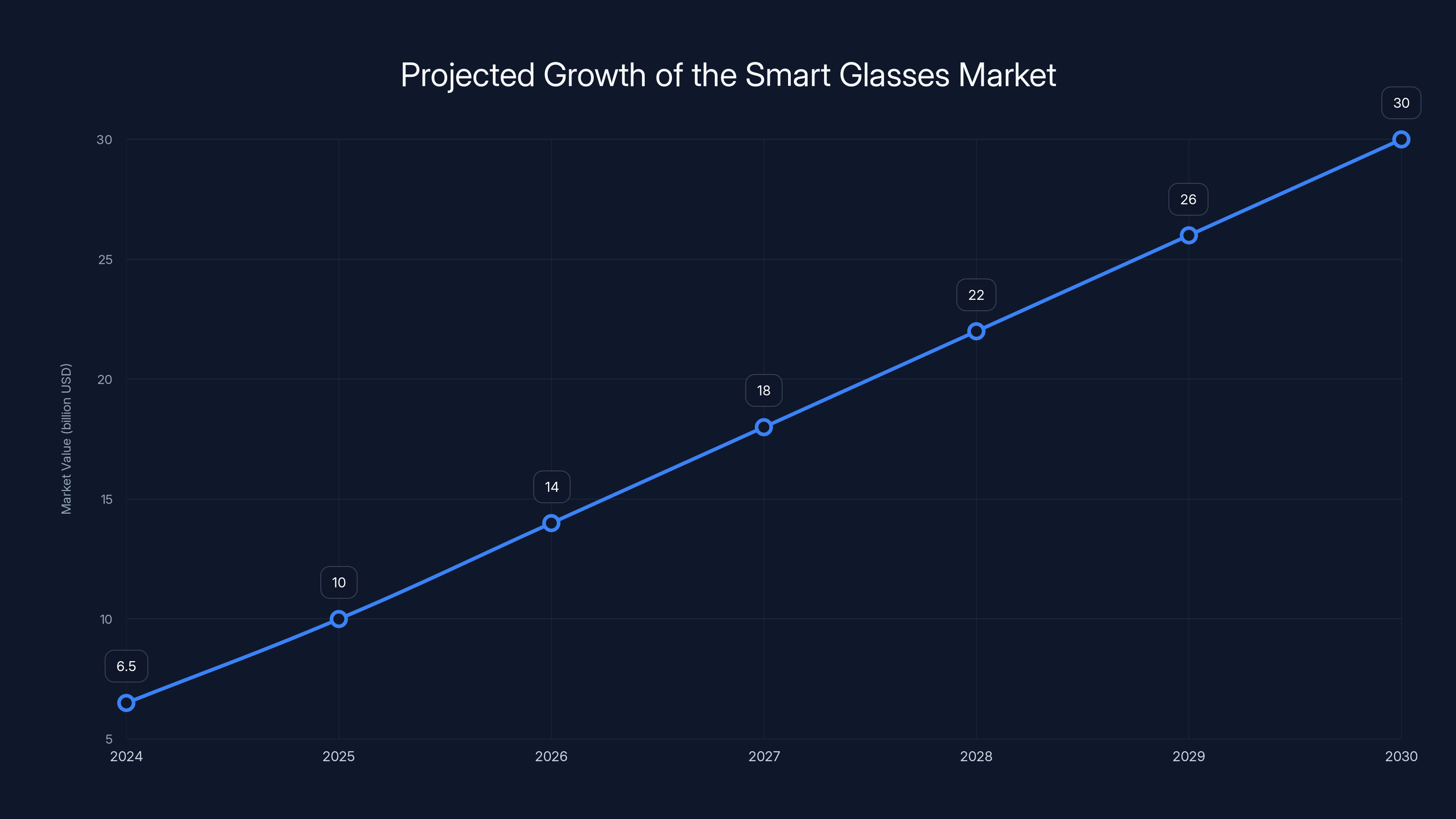

The Numbers That Started the Rush

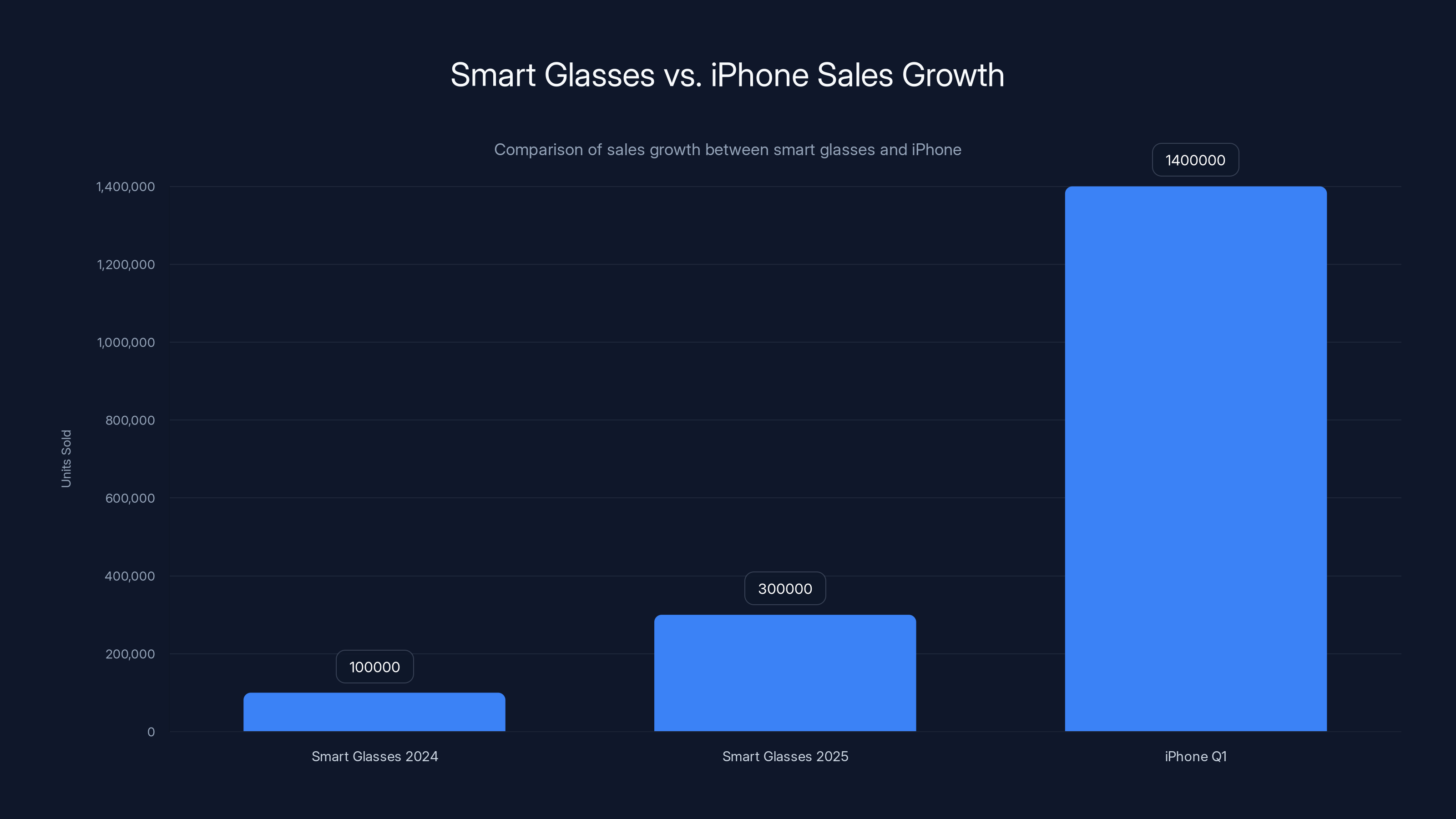

Let's start with Meta's claim that smart glasses sales tripled in the last year. That sounds impressive until you ask the next question: tripled from what? If they sold 100,000 pairs in 2024, then tripling to 300,000 in 2025 is real growth. But the iPhone sold 1.4 million units in its first quarter. To call smart glasses "some of the fastest growing consumer electronics in history" requires either amazing growth or a very selective definition of history.

That said, the growth is real enough that Meta felt comfortable highlighting it to investors. The current lineup includes the standard Ray-Ban Meta smart glasses, plus Oakley-branded models designed for athletic use. Meta's been iterating on these devices for years, slowly adding features and improving battery life. What changed recently is that the company stopped positioning them as metaverse accessories and started positioning them as genuine AI assistants.

This is the key shift nobody noticed. Smart glasses aren't being sold as a way to enter virtual worlds anymore. They're being sold as a better way to interact with AI in the real world. You can point at something, ask a question, and get an instant answer. You can see directions overlaid on your actual surroundings. You can get real-time information about what's in front of you. That's a fundamentally different value proposition than "hang out in a virtual meeting room."

The smartphone comparison Zuckerberg made is actually useful here. When smartphones arrived, they solved a genuine problem: you could do on the go what previously required a computer. Smartphones weren't just miniature computers. They were fundamentally new tools. Smart glasses might follow a similar path, but not for the reasons tech executives initially thought. Not for social VR. For AI assistance that's always available and contextually aware.

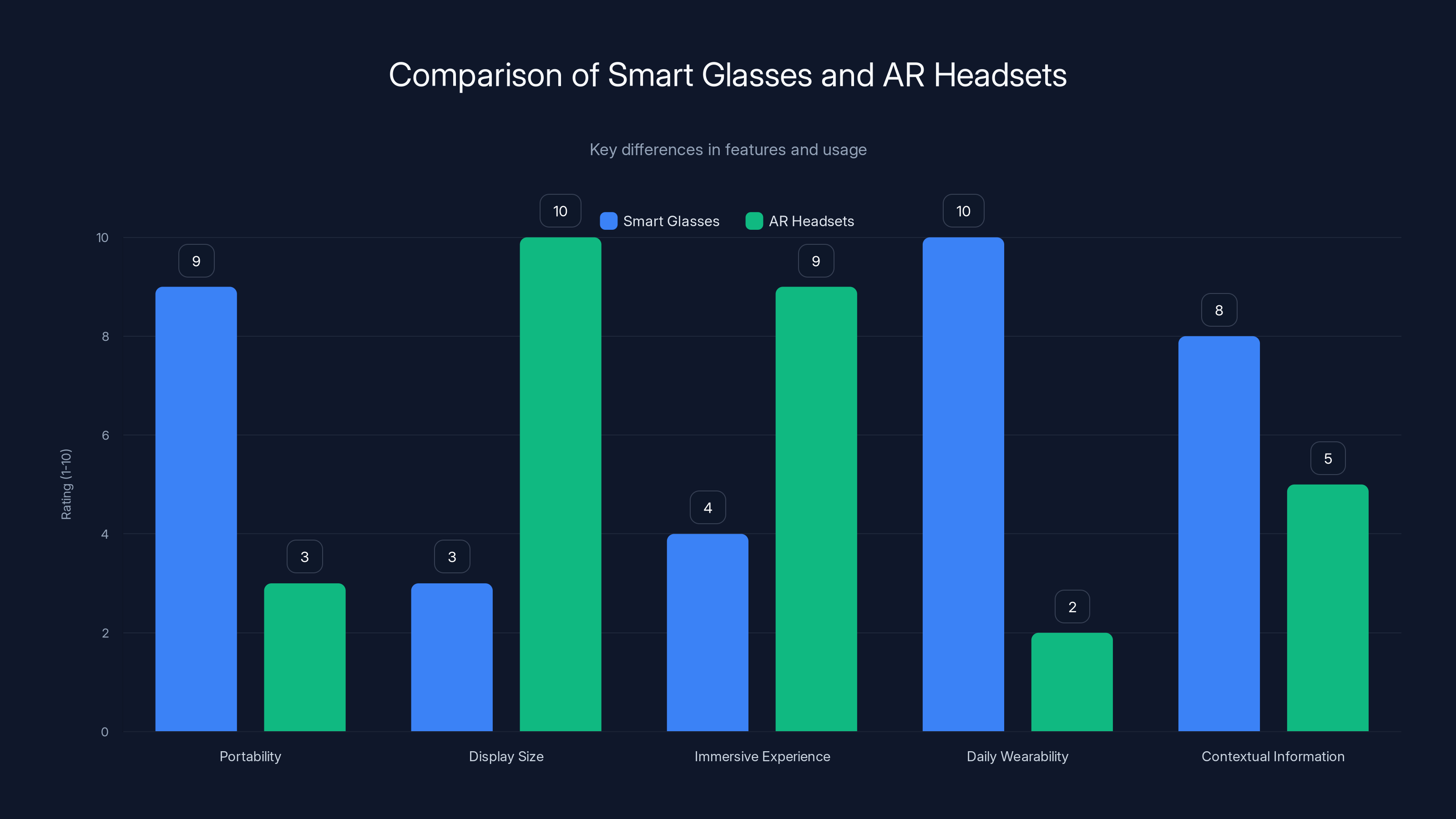

Smart glasses are highly portable and suitable for daily wear, offering contextual information, whereas AR headsets excel in immersive experiences with larger displays. Estimated data based on typical characteristics.

Why Google's Move Signals Something Different

Google's decision to invest $150 million in a partnership with Warby Parker is worth analyzing carefully. This isn't Google building their own hardware from scratch. This is Google partnering with one of the largest eyewear retailers in the United States to integrate smart technology into existing frames.

That's a smarter approach than it initially sounds. Warby Parker has retail locations, a supply chain, and relationships with optometrists. They understand how to fit glasses to faces. Google has AI and software. When you combine those capabilities, you get smart glasses that could actually be sold through normal eyewear channels, not just online or at specialty retailers.

This also tells you something about where the market is heading. The tech isn't going to be the bottleneck. Google's AI is sophisticated. Meta's computer vision is solid. The real challenge is manufacturing, distribution, and making these things at a price point that regular people will accept. That requires the kind of operational infrastructure that a company like Warby Parker brings to the table.

The fact that Google chose to partner rather than build in-house suggests they understand this. They're betting that smart glasses become a feature, not a device. A feature that gets bundled with your normal eyewear purchase. That's closer to the smartphone moment than VR headsets ever were.

Smart glasses sales tripled from 100,000 to 300,000 units from 2024 to 2025, but still lag behind the iPhone's initial sales of 1.4 million units in its first quarter. Estimated data.

Apple's Quiet Pivot: What It Means

According to reporting, Apple is shifting staff from Vision Pro development to smart glasses projects. If you've used a Vision Pro, you understand why this matters. The device is incredible for specific use cases: gaming, watching movies, spatial computing tasks. But it's a headset you put on. It's not something you wear all day. It's not something that integrates seamlessly into your normal life.

Apple learned what others are also figuring out: the future of wearable computing isn't about better displays or more immersive experiences. It's about ubiquity. It's about a device that works so naturally with how you already interact with the world that you barely think about it. Vision Pro is amazing, but it's a special-purpose tool. Smart glasses could be everyday accessories.

The problem Apple faces is the same one everyone faces: making smart glasses that people actually want to wear. They need to be fashionable enough that people are comfortable wearing them in public. They need to be light enough that you don't think about them. They need to have battery life measured in days, not hours. And they need to do all this while containing sophisticated AI, cameras, and displays.

Apple has the design expertise, the software integration skills, and the supply chain to potentially pull this off. But they're not there yet. The reporting suggests a reallocation, not a product. They're investing in the possibility, not the certainty.

The Snap Subplot: When Startups Become Midwives

Snap announced that it's spinning out Specs, its AR glasses product, into a separate subsidiary. This is significant for a specific reason. Snap invented the concept of glasses-based AR before it was cool. Snapchat Spectacles were actually early smart glasses. They flopped in the original implementation, but the company never stopped iterating.

Now Snap is saying that smart glasses need to be a standalone business, not a side project within a social media company. This is either an admission that Snapchat's parent company isn't the right home for this technology, or it's a strategic move to attract investment and partnerships. Possibly both.

What Snap understands that others are still learning is that AR glasses need an ecosystem. They need apps. They need developers building for them. They need a reason to exist beyond "it's a new interface." Snapchat's strength has always been filters and camera-based visual experiences. That actually maps onto what AR glasses could do well. But Snapchat the social network might not be the right distribution mechanism.

This is why spinning it out matters. A separate company can form partnerships with other hardware manufacturers. A separate company can license its technology. A separate company can exist in a different business model than social media advertising. Snap might be onto something here that larger, more integrated companies are missing.

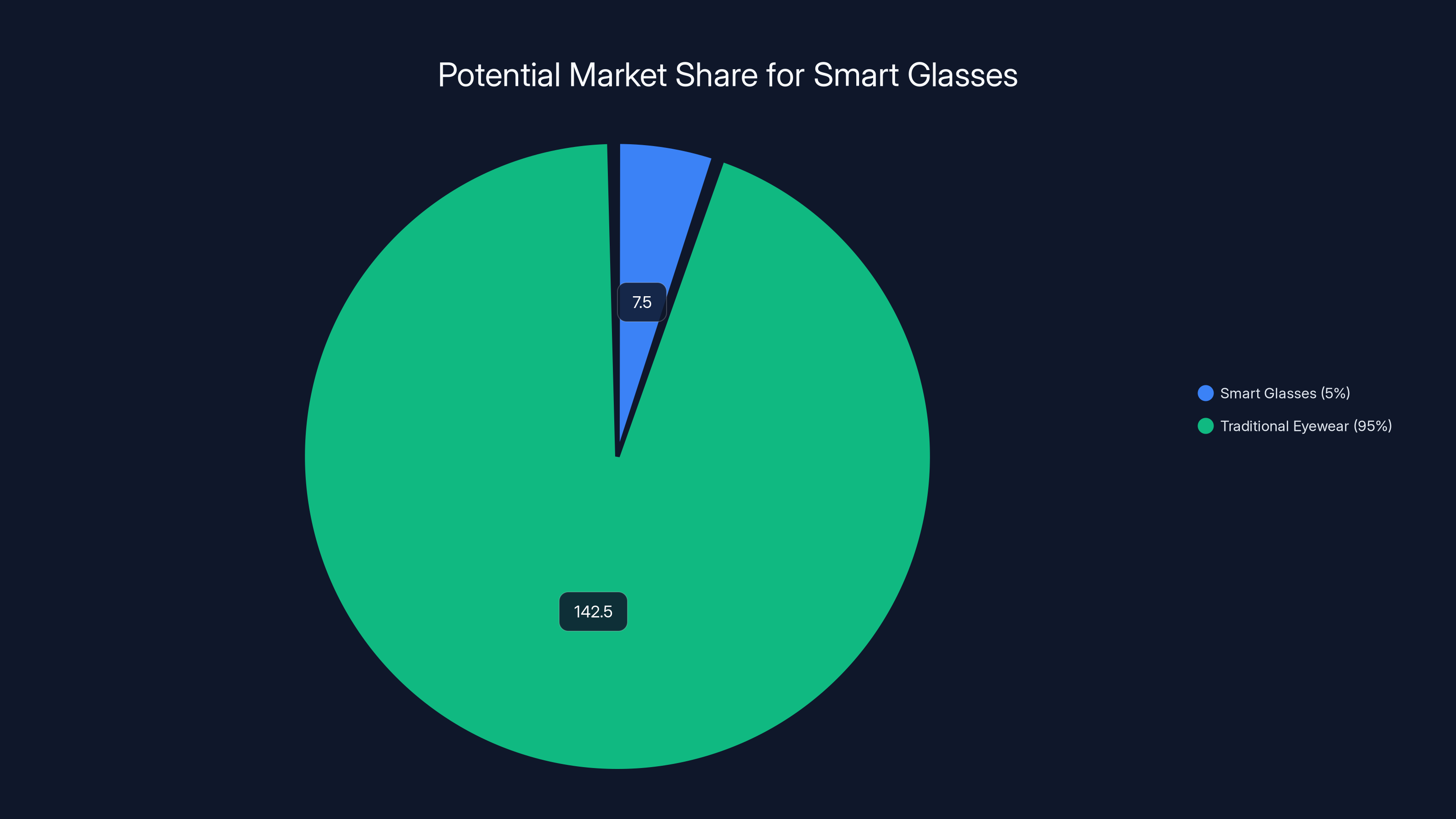

If a company captures 5% of the

OpenAI's Hardware Play: The Unexpected Entry

OpenAI, a company known for software and AI models, is exploring hardware. Specifically, wearables. The current thinking seems to be something like an AI pin or earbuds, rather than full glasses. But the fact that they're exploring hardware at all is worth examining.

OpenAI doesn't have the manufacturing expertise that Apple or Google has. They don't have retail infrastructure like Amazon or Best Buy. What they have is the best large language model on the planet. If anyone can build wearable AI that actually understands what you're asking and provides useful answers, it might be them.

The challenge OpenAI faces is that AI hardware is a capital-intensive business. You need factories. You need supply chains. You need quality control. You need customer support. These are things that software companies typically don't do well. The fact that OpenAI is even considering this suggests they see something that justifies the complexity.

Maybe they see wearable AI becoming such a dominant interface that they can't let others control that layer. If Apple owns the glasses, Google owns the partner ecosystem, and Meta owns the software-first approach, OpenAI might feel pressure to have a direct relationship with users. That's speculative, but it makes sense from a strategic perspective.

The Humane AI Pin Lesson: Why Hardware Is Hard

Before we get too excited about smart glasses becoming ubiquitous, let's talk about the Humane AI Pin. Here was a company that raised massive funding, had former Apple executives, and built an AI wearable that was supposed to be a smartphone replacement. It failed so spectacularly that it's become a cautionary tale.

The pin had decent technology. The AI could theoretically do useful things. But the execution was poor. Battery life was terrible. The interface was confusing. The price was absurd. And most importantly, it didn't solve a problem people actually had. It was a solution looking for a problem.

This is the real risk with smart glasses. The technology is advancing. The software is getting better. But if the devices don't solve genuine user problems, they'll end up as expensive novelties. Zuckerberg talks about smart glasses as vision correction devices that happen to have AI built in. That's a smarter positioning than "replacement for your phone." But execution matters way more than positioning.

Meta's advantage here is that they've been iterating for years. The Oakley glasses for athletic use is actually a promising category. Athletes want to see real-time data about their performance. They want navigation without looking down at their phone. They want to stay hydrated and paced correctly. Smart glasses could genuinely improve their experience. That's a better starting point than trying to replace every interaction you have with a computer.

The smart glasses market is expected to grow from

The Smartphone Comparison: Is It Fair?

Zuckerberg compared smart glasses to the moment when smartphones arrived. The idea is that just as flip phones evolved into smartphones over a few years, regular glasses will evolve into AI glasses. This comparison is both useful and misleading.

It's useful because it captures something real: a transition period where old technology gets enhanced with new capabilities. When smartphones arrived, phones still made calls and sent texts. They just did other things too. Smart glasses could work the same way. Regular glasses with vision correction, but also with AI assistance, cameras, and displays.

It's misleading because it underestimates how transformative smartphones actually were. Smartphones didn't just make phones smarter. They fundamentally changed how humans access information, communicate, and navigate the world. They created network effects that made them indispensable. They enabled entire new industries. Smart glasses might become very successful without achieving that level of transformation.

A more honest comparison might be to smartwatches. Smartwatches are everywhere now. Almost nobody lives without one in developed countries. But smartwatches didn't replace phones. They complemented phones. They added convenience without fundamentally transforming how humans interact with technology. Smart glasses could follow a similar path. Hugely successful and widely adopted, but as a complement to phones rather than a replacement.

The Physics Problem Nobody's Solved Yet

Here's something that gets glossed over in all this optimistic talk about smart glasses: the engineering is genuinely difficult. You need displays that are bright enough to be readable in daylight. You need them small enough that they don't make the glasses look ridiculous. You need them to show information without being distracting. You need batteries that last all day. You need cameras that can understand what they're looking at. You need all of this in a frame that weighs less than regular glasses.

Meta's current glasses weigh about 100 grams. That's not terrible, but it's heavier than standard glasses. The displays are decent, but not as bright or clear as you'd want for detailed information. Battery life is okay, but not amazing. None of these are deal-breakers, but they're all constraints that still need solving.

The companies working on this are making progress. But progress isn't the same as solved. Until smart glasses can match the weight, comfort, and visual clarity of regular glasses while adding significant AI capabilities, adoption will be limited. The people who'll buy them first are the ones for whom the AI features justify the added complexity. Athletes. People who need navigation. People who work with their hands and need information without looking down.

Mass market adoption requires solving at least two of the three hard problems: weight, display brightness, or battery life. Maybe solving all three. That's still a few years away, not months away.

Estimated data suggests Meta leads with 30% focus on smart glasses, followed by Apple and Google. This indicates a significant industry shift towards AI wearables.

Why AI Changed The Equation

The reason we're suddenly seeing all this investment in smart glasses is because AI got dramatically better at actually understanding context. This is crucial. Early smart glasses were often just cameras mounted on frames. You could see stuff overlaid, but the device didn't really understand what you were looking at or what you might want to know.

Now you can train a language model to understand images, answer questions about what it's seeing, and provide relevant information in real time. You can ask your smart glasses "what breed is that dog?" and get an accurate answer. You can point at a plant and learn its name. You can see nutritional information overlaid on the food in front of you. These are the kinds of experiences that make the device useful rather than gimmicky.

Meta's pitch during earnings was basically this: we have good AI, we have decent hardware, and we're selling the combination as a tool for real-time information and assistance. That's a fundamentally different value proposition than the metaverse pitch ever was. And it's one that actually maps onto genuine user needs.

Google's partnership with Warby Parker makes sense in this context too. Google provides the AI. Warby Parker provides the distribution and the physical product expertise. Together, they might actually create something that people want to wear.

Apple's pivot toward glasses makes sense because Apple's strength has always been taking technology that exists elsewhere and integrating it in a way that just works. If they can take whatever AI capabilities they develop and bake them into a pair of glasses that work seamlessly with your iPhone and Apple ecosystem, that's a compelling product.

The Real Competition Isn't Between Companies

Here's a perspective shift that matters: the competition isn't really between Meta, Apple, and Google. The competition is between smart glasses and smartphones. Will people adopt smart glasses as a complement to their phones? Absolutely, probably. Will they adopt them as a replacement? That's much less certain.

Phones are incredibly versatile. You can do almost anything on a phone that you can do on a computer, just smaller. Trying to replicate that versatility on glasses seems misguided. But using glasses to handle specific, contextual tasks? That works. Navigation. Real-time information lookup. Video calling. Hands-free controls. These are things glasses could do better than phones for specific use cases.

The winners in the smart glasses space won't necessarily be the ones who sell the most glasses. They'll be the ones who control the software layer. If Google wins the partnership game and gets their AI on millions of Warby Parker frames, they win even if they never directly manufacture glasses. If Apple wins by making smart glasses that seamlessly integrate with their ecosystem, they win. If Meta wins by being the first to scale production and iterate to a really good product, they win.

These aren't mutually exclusive. Multiple companies can be successful here. The question isn't "will smart glasses be huge?" It's "will smart glasses become an important interface, and which company will be the one people trust for that interface?"

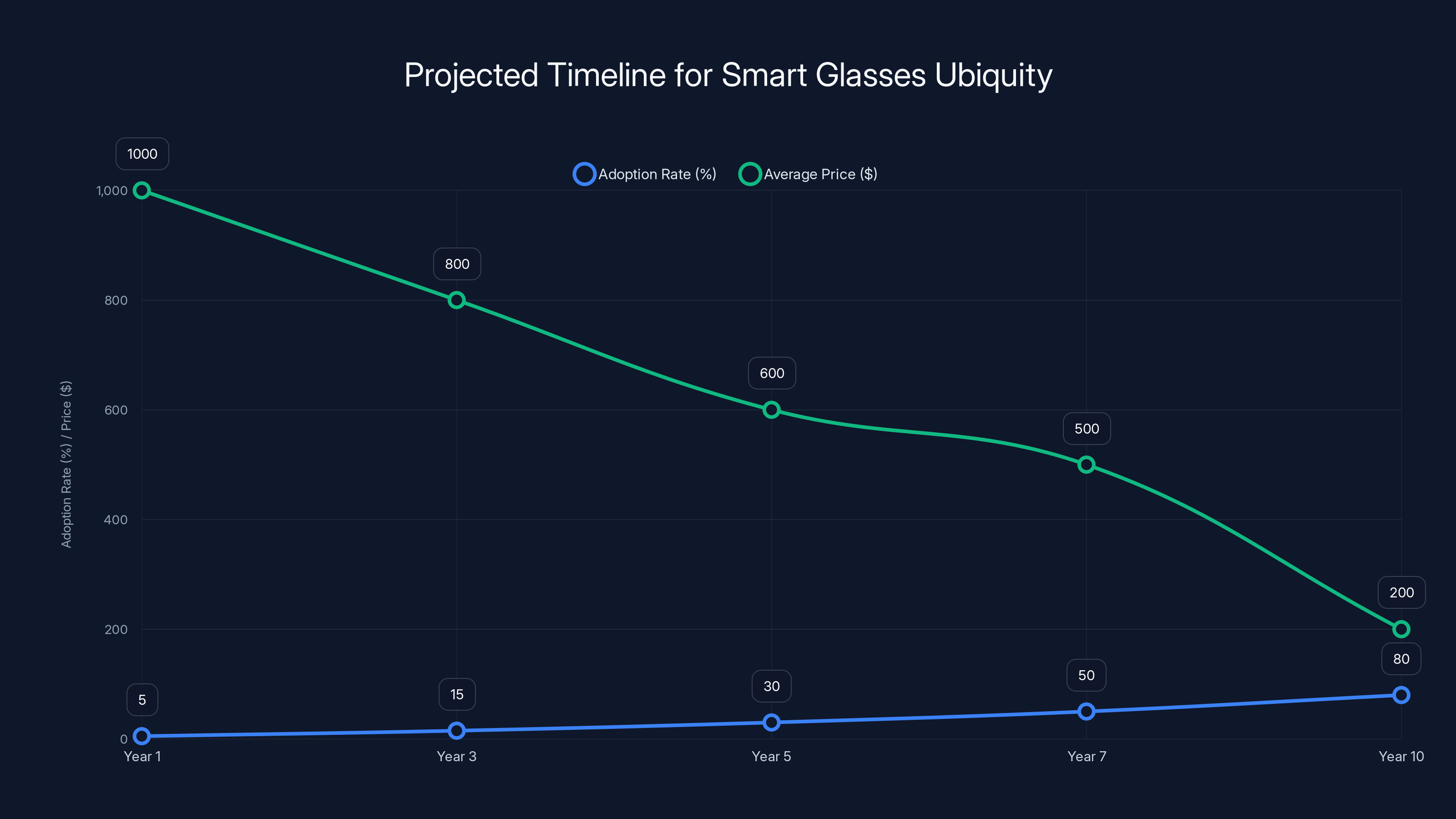

Estimated data shows smart glasses adoption rising to 80% over a decade, with prices dropping from

What Would Actually Make This Work

For smart glasses to achieve Zuckerberg's vision, a few things need to happen. First, the technology needs to be invisible. The displays need to be so good that you forget they're there. The weight needs to match regular glasses. The battery needs to last a full day without charging.

Second, the interface needs to be natural. You shouldn't need to learn a new way to interact with the world. You should be able to glance at information the way you glance at your phone screen now, except it's always there and contextually relevant. This is hard. Really hard. It requires understanding not just what the user is looking at, but what the user wants to know about what they're looking at.

Third, there need to be regulations about privacy and recording. People won't wear glasses with cameras all day if they think their privacy is being violated or if the glasses are recording everything they see. The fact that this is still unresolved in many jurisdictions is a significant barrier to adoption.

Fourth, there needs to be a killer app. For the iPhone, it was the internet in your pocket combined with apps. For smart glasses, the killer app might be real-time visual AI assistance. Or it might be something nobody's thought of yet. But there needs to be something that makes people say "I can't live without this."

Right now, we're at the stage where smart glasses can do useful things. They're not yet at the stage where they're indispensable. Zuckerberg's prediction assumes that indispensability arrives within a few years. Maybe it does. But the path from "useful tool" to "everyone wears them" is longer than it appears.

The Metaverse Hangover: Why Skepticism Is Warranted

Here's the thing nobody wants to say directly: Zuckerberg's track record on predicting the future is... mixed. He genuinely believed that the metaverse was the next chapter of the internet. He invested enormous resources into making that happen. It didn't work. Not because the technology was bad, but because the value proposition didn't resonate with regular people.

That doesn't mean he's wrong about smart glasses. But it does mean his optimism should be weighted against his previous optimism. He might see possibilities that others miss. Or he might be seeing what he wants to see because he needs the smart glasses bet to work after the metaverse didn't.

The difference is that this time, other companies are making similar bets. Google, Apple, OpenAI. If only Meta were pushing smart glasses, you could dismiss it as Zuckerberg chasing another vision. But when the entire industry shifts capital toward something, it suggests there's genuine belief that it matters.

That doesn't mean Zuckerberg's timeline is right. He said it's hard to imagine a world in "several years" where most glasses aren't AI glasses. Several years is vague. It could mean 3 years or 7 years. And "most glasses" is an extremely high bar. If smart glasses capture 30% of the eyewear market in 5 years, that would be extraordinary success. It wouldn't be "most glasses," but it would be massive adoption.

The Athletic Use Case: The Closest Thing To a Killer App

If smart glasses are going to succeed anywhere first, it might be in athletics and fitness. Meta's Oakley smart glasses are designed for this. And for good reason. Athletes have strong use cases for real-time data. Runners want to know their pace and distance without stopping. Cyclists want to see their power output and heart rate. Swimmers want to track their stroke count and splits.

Currently, athletes use dedicated sports watches or phone apps for this information. Smart glasses could integrate all of that information into the visual field, giving athletes critical data without breaking focus. That's genuinely useful. That could drive adoption.

The challenge is that the athletic market is a relatively small fraction of the total eyewear market. If smart glasses succeed in fitness and never expand beyond that, it's a niche product. A successful niche product, but a niche nonetheless. To achieve Zuckerberg's vision, smart glasses need to solve problems for regular people doing regular things. Not just for people exercising.

But athletic use cases could be the wedge. They could be how the technology gets refined and improved. Every generation of athletic smart glasses could get better, lighter, more capable. Eventually, some of those capabilities migrate to consumer versions. That's how many technologies reach the mass market: start with enthusiasts, evolve with iteration, then reach regular people.

Privacy, Regulation, and the Elephant in the Room

Smart glasses with cameras and AI raise fundamental privacy questions that haven't been fully answered. If you're wearing glasses that can record everything you see, are you recording the people you see? What happens to that data? Who controls it? Can it be subpoenaed?

These aren't trivial questions. They're probably more important than the technical questions about battery life and display brightness. If societies decide that always-on recording glasses are a privacy nightmare, smart glasses adoption will be limited to specific use cases. If societies find a way to balance privacy concerns with the benefits of the technology, adoption could be much broader.

Right now, the regulatory landscape is unclear. In some countries, wearing recording devices is restricted in public places. In others, it's completely legal. This fragmentation means that smart glasses companies will have different rules in different markets. That makes global scaling harder.

This is one place where the smartphone comparison breaks down. Smartphones have cameras, but they're clearly phones. They're not discrete devices hidden in regular glasses. The privacy implications of smart glasses are genuinely different, and they haven't been solved yet.

The Path to Ubiquity: How It Actually Happens

If smart glasses do become ubiquitous, here's probably how it happens. First, they become popular among specific user groups: athletes, construction workers, surgeons, people who work with their hands and need information without looking down. These early adopters drive iteration and improvement.

Second, the technology improves significantly. Displays get brighter and clearer. Weight decreases. Battery life improves. The software gets more useful at understanding context and providing relevant information. This takes a few years, but by year 5 or so, smart glasses are legitimately comparable to regular glasses in terms of weight and comfort.

Third, the price comes down. At first, smart glasses cost

Fourth, the software gets addictive. Someone builds an app or a feature that becomes so useful that people want it on their smart glasses. Maybe it's real-time translation of text they see. Maybe it's a social feature. Maybe it's something that hasn't been invented yet. But there's something that makes people say "okay, now I need this."

Fifth, they become normal. A decade after serious adoption starts, smart glasses are just another form of eyewear. You can get them at regular optometrists. They come with regular glasses. Most people have a pair, just like most people have a phone.

Does that timeline match Zuckerberg's "several years"? Not really. It's more like "a decade." But it's also plausible. And it doesn't require smart glasses to replace phones. It just requires them to become a normal part of how people interact with the world.

The Counter-Argument: Why Smart Glasses Might Fail

We should also consider the possibility that Zuckerberg is wrong. Smart glasses might never become ubiquitous. Here are some reasons why.

First, they might solve too many problems badly instead of solving one problem well. A multi-tool that does everything is often worse than specialized tools that do one thing really well. Your phone might remain the primary interface for information and communication, and smart glasses might remain a niche accessory.

Second, the aesthetic might never be solved. People don't want to look like they're wearing sci-fi gear. If smart glasses have to look futuristic to contain all the necessary technology, regular people won't wear them. Fashion and comfort matter more than functionality for everyday products.

Third, the information overload might be overwhelming. Imagine seeing a constant stream of AI-generated suggestions and information overlaid on everything you see. That could be annoying rather than useful. The interface challenge might be harder than it seems.

Fourth, something else might become the next big interface before smart glasses get good enough. Maybe AR contact lenses become viable. Maybe neural interfaces become consumer products. Maybe the interface of the future is voice, not visual.

Fifth, privacy concerns might create regulatory frameworks that make smart glasses impractical. If you can't wear recording glasses in public without special permission, the value proposition collapses.

These aren't crazy possibilities. They're legitimate reasons to think that Zuckerberg might be wrong this time too.

What To Watch: Signals That Smart Glasses Are Actually Happening

If you want to know whether smart glasses are actually becoming ubiquitous or whether this is another tech bubble, watch for these signals.

First, watch whether the major tech companies actually ship products and iterate on them, or whether this remains a limited release thing. If Google, Apple, and Meta all have multiple generations of smart glasses on the market within 3 years, that's a signal that they're serious.

Second, watch whether indie developers start building apps and services for smart glasses. If there's a thriving ecosystem of third-party developers creating useful experiences, that's a signal of health. If smart glasses remain platform-only experiences from the companies that make them, that's a signal of weakness.

Third, watch the pricing. If smart glasses are expensive luxury items, adoption will be limited. If prices fall to competitive with regular glasses plus a phone, adoption could be real.

Fourth, watch the form factor. If the glasses look increasingly like regular glasses rather than like sci-fi gadgets, that's a good signal. If they keep looking weird, adoption will struggle.

Fifth, watch what actual users say. Reviews matter. If people who buy smart glasses find them genuinely useful, adoption will accelerate. If reviews are lukewarm, adoption will stall.

Final, watch whether the use cases expand beyond athletics and niche applications. If smart glasses remain useful mainly for specific professions or activities, they'll be successful but niche. If they become useful for everyday tasks, adoption could be exponential.

The Bottom Line: Possibility Doesn't Equal Certainty

Zuckerberg is probably right that smart glasses will become more common over the next several years. The technology is advancing. The investment is real. The industry is moving in that direction. But he might be wrong about the timeline, the adoption rate, and the form that ubiquity takes.

What's clear is that smart glasses are no longer science fiction. They're here, they're being refined, and multiple companies are betting significant resources on them. Whether they become as ubiquitous as Zuckerberg predicts depends on solving genuine engineering challenges, finding genuinely useful applications, navigating privacy regulations, and dealing with the forever-wild variable of consumer preference.

The smartphone comparison is instructive, but not in the way Zuckerberg intends. Smartphones succeeded because they solved multiple problems better than previous solutions and created network effects that made them indispensable. Smart glasses will need to do something similar. Right now, they solve some specific problems well. They might eventually solve broader problems. Or they might remain a useful niche product that never achieves the ubiquity of smartphones.

The smart money right now is on smart glasses becoming significantly more common and useful than they are today. But the smartest approach is to remain skeptical until the technology actually works as promised and people actually want to use it in their daily lives. Zuckerberg's track record doesn't inspire blind faith. But the broader industry consensus does suggest that something real is happening.

In a few years, we'll know whether this was a genuine inflection point or another false dawn in wearable computing. Until then, watch the signals. Pay attention to what gets built. Notice what people actually use. That's where the truth lives, not in what executives predict.

FAQ

What exactly are smart glasses?

Smart glasses are eyewear devices that combine traditional vision correction or cosmetic lenses with built-in cameras, displays, and AI processing. They overlay digital information onto your view of the physical world, allow you to take photos and video, and can interact with AI assistants that understand what you're looking at. Meta's Ray-Ban smart glasses, for example, have high-resolution outward-facing cameras, tiny displays, and integration with Meta's AI models. They're not the same as virtual reality headsets or augmented reality headsets you hold in your hands. They're glasses you wear like normal eyewear.

How do smart glasses differ from augmented reality headsets?

Augmented reality headsets, like the Apple Vision Pro, are bulky devices that you put on and take off. Smart glasses are designed to be worn all day as regular eyewear. AR headsets have high-resolution displays and are designed for immersive experiences. Smart glasses have smaller displays and are designed to provide contextual information without being distracting. AR headsets might show you a detailed virtual environment overlaid on reality. Smart glasses might show you navigation directions or the name of a plant you're looking at. One is meant for extended sessions. The other is meant to be worn continuously.

What can smart glasses currently do?

Current smart glasses like Meta's Ray-Ban models can identify objects and people, answer questions about what the camera sees, provide real-time language translation, show navigation directions, allow hands-free video calling, and integrate with AI assistants to execute commands. Some models have fitness tracking capabilities. The specific features depend on the device and the AI software running on it. They're getting better at understanding context, which means they can provide more relevant information without needing explicit instructions.

Why are tech companies suddenly investing heavily in smart glasses?

Three factors are converging. First, AI got dramatically better at understanding images and context, which makes smart glasses genuinely useful rather than gimmicky. Second, supply chain maturity and component miniaturization made smart glasses actually feasible to manufacture at scale. Third, the smartphone market is mature and growth has slowed, so tech companies are looking for the next platform. Smart glasses represent a potentially massive new interface layer between users and AI.

What are the biggest challenges smart glasses still need to overcome?

The engineering challenges are substantial: displays that are bright enough to see in sunlight but small enough to be unobtrusive, batteries that last all day, processors that are powerful enough for AI but efficient enough for long battery life, and form factors that look like normal glasses rather than sci-fi equipment. Beyond engineering, there are privacy and regulatory challenges around always-on cameras and recording. Finally, there's the user experience challenge of creating an interface that's useful and natural without being overwhelming or distracting.

Will smart glasses actually replace smartphones?

Unlikely in the near term. Smart glasses might replace phones for specific tasks like navigation and hands-free communication. But phones are so versatile for so many uses that replacing them entirely would require smart glasses to be nearly as capable, which presents enormous engineering and interface challenges. More likely, smart glasses become a complement to phones, the way smartwatches complement phones now. You'll still use your phone for detailed tasks. You'll use your smart glasses for quick information and hands-free interactions.

How much do smart glasses cost right now?

Current models range from around

What does the privacy situation look like for smart glasses?

Privacy regulations around smart glasses are still developing. In some jurisdictions, recording in public is legal and unrestricted. In others, there are significant restrictions. Some countries and cities have specific rules about recording others without consent. Companies are working on privacy features like indicators that the device is recording and encryption of data. But there's no global consensus yet on acceptable use. This regulatory uncertainty could affect adoption rates in different regions.

Which company's smart glasses should I buy if I want to get ahead of the curve?

Meta's Ray-Ban smart glasses are the most mature product on the market right now with good reviews and actual AI capabilities. If you want something that exists and works today, that's probably your best bet. But remember that this is still an emerging category. If you're not sure you'll find the device genuinely useful for specific tasks you do regularly, you might want to wait another generation or two. The technology will be cheaper, better, and more capable in a few years.

The Future Is Coming, But Slowly

Mark Zuckerberg's prediction about smart glasses might be right. Or it might be another case of a tech executive seeing the future they want to see. The truth is probably somewhere in the middle. Smart glasses will almost certainly become more common and more capable. But Zuckerberg's timeline is probably optimistic, and his vision of ubiquity might need refinement.

What matters now is execution. Meta, Google, Apple, and others are no longer just talking about smart glasses. They're building them, selling them, and iterating on them. That's different from the metaverse moment, where most of the work was internal R&D with limited public products. This time, there are products people can actually buy and use.

So Zuckerberg might be right this time. Or he might be wrong again. But this time, the industry's behavior suggests there's genuine substance behind the vision. And that's worth paying attention to, even if you take his optimism with skepticism.

Key Takeaways

- Smart glasses sales have tripled for Meta in the past year, but this growth needs context about the absolute scale of the market

- Google, Apple, OpenAI, and Snap are all investing heavily in smart glasses, suggesting broader industry confidence beyond just Meta's vision

- The technology has fundamentally improved with advanced AI that can understand context, making current smart glasses genuinely useful rather than gimmicky

- Major engineering challenges remain: display brightness, weight, battery life, and form factor still need solving before mass adoption becomes realistic

- Privacy and regulatory uncertainty around always-on recording glasses could significantly impact adoption rates in different geographic markets

- Athletic and professional use cases offer the most promising near-term opportunities for smart glasses adoption and scaling

- Smartphone comparison is useful but potentially misleading—smart glasses are more likely to complement phones than replace them

- Zuckerberg's timeline of 'several years' may be optimistic given how long hardware typically takes to reach mass market maturity

Related Articles

- Snap's AR Glasses Spinoff: What Specs Inc Means for the Future [2025]

- Snap's Specs Subsidiary: The Bold AR Glasses Bet [2025]

- Tesla's $2B xAI Investment: What It Means for AI and Robotics [2025]

- AirPods 4 Noise Canceling at $120: Best Deal & Comparison [2025]

- iPhone 18 Pricing Strategy: How Apple Navigates the RAM Shortage [2025]

- Best Fitness Trackers & Watches [2026]: Complete Buyer's Guide

![The Smart Glasses Revolution: Why Tech Giants Are All In [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/the-smart-glasses-revolution-why-tech-giants-are-all-in-2025/image-1-1769641805937.jpg)