Introduction: A New Physics for Computing

Imagine if your computer could harness the power of randomness instead of fighting it. Imagine if the natural fluctuations in silicon chips became features rather than bugs. That's the radical premise behind thermodynamic computing, and it's not science fiction anymore.

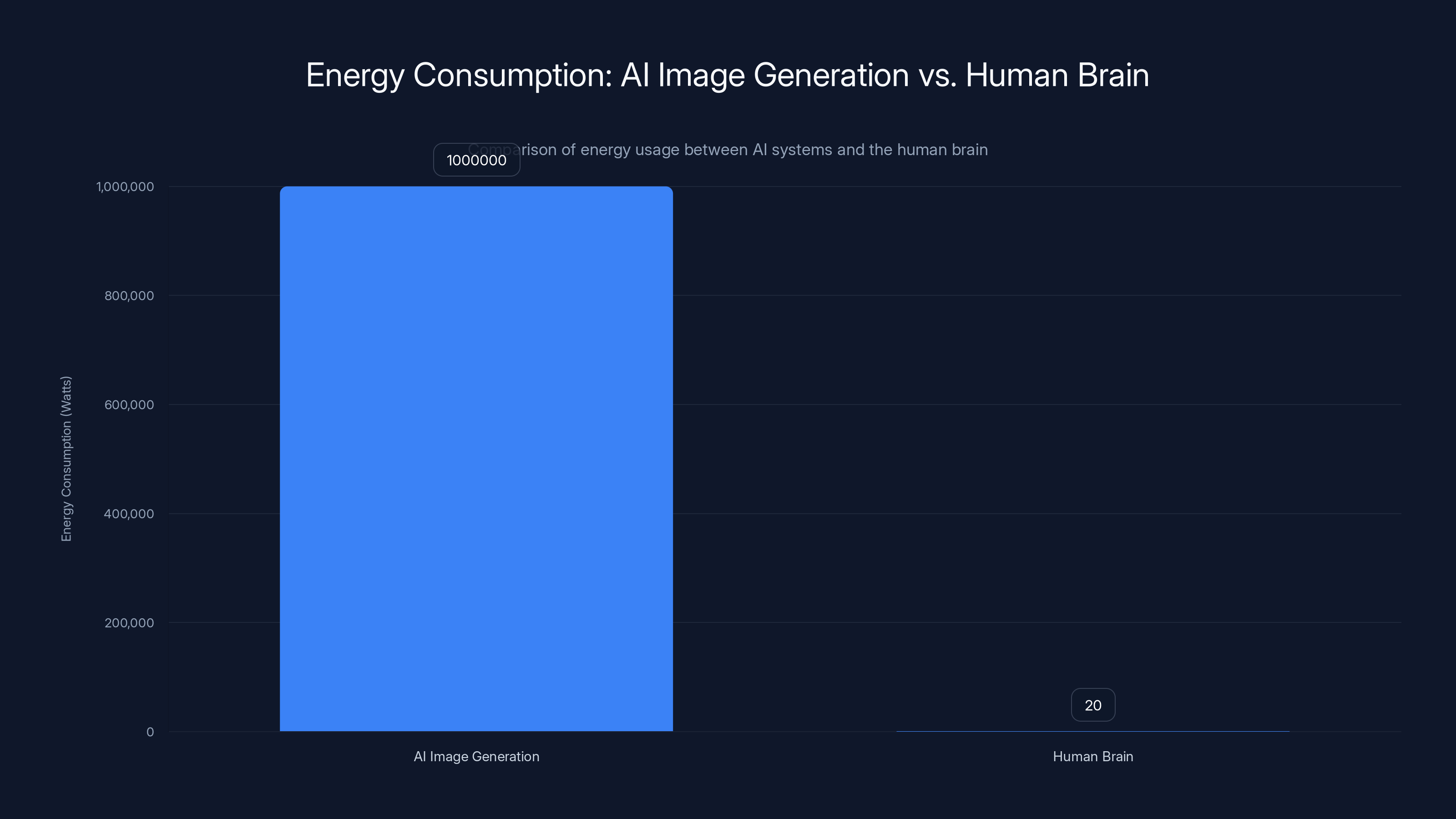

Right now, AI image generators like DALL-E and Midjourney consume staggering amounts of electricity. A single image generation task can pull megawatts from data centers running 24/7. The economics are brutal: every query costs money in power alone, before you factor in cooling, infrastructure, and maintenance. Meanwhile, your brain generates complex visual thoughts using about 20 watts. That disparity haunts researchers.

Thermodynamic computing offers a different path. Instead of the discrete on-off logic that's defined computing since the 1940s, this approach uses physical energy flows, thermal fluctuations, and natural entropy to perform machine learning calculations. Think of it less like traditional computing and more like guided chemistry. The system allows information to spread and degrade naturally, then learns to reverse that process.

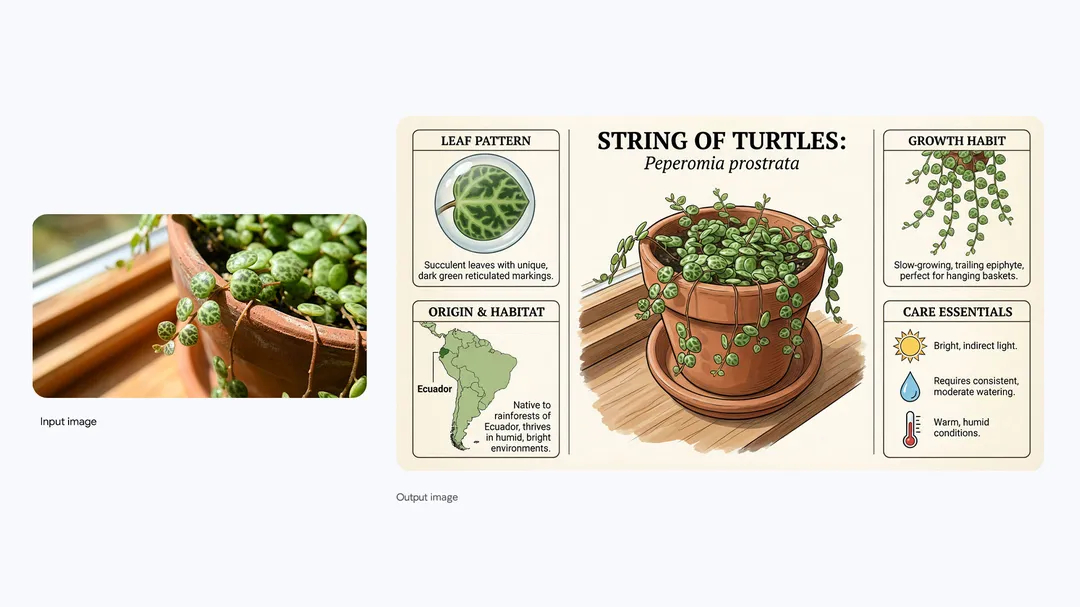

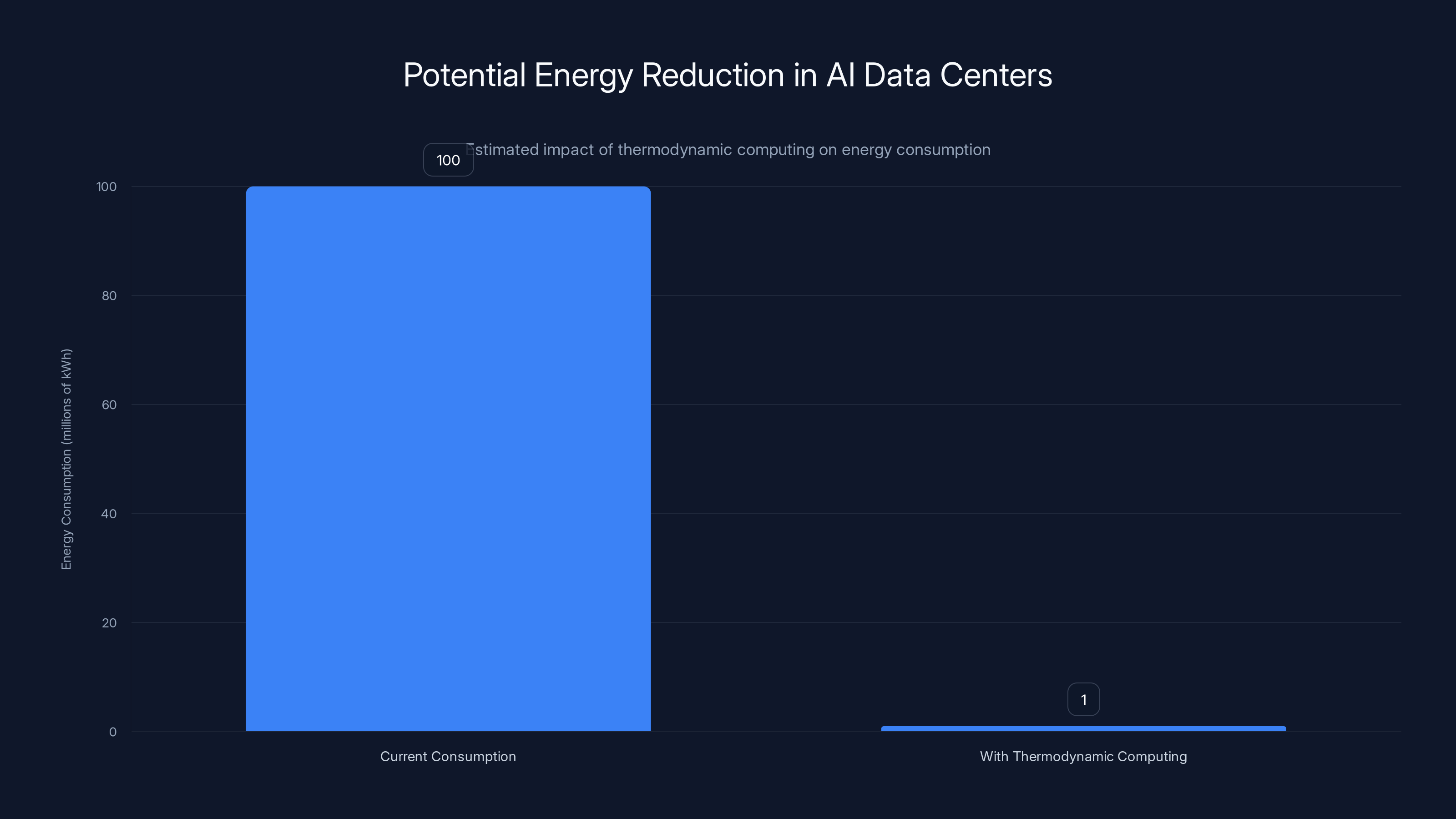

The potential is staggering. Researchers claim thermodynamic computing could reduce the energy footprint of AI image generation by a factor of ten billion compared with conventional systems. For context, that's the difference between running on a solar panel versus powering a small city. But there's a catch, and it's a big one: we don't have thermodynamic computers capable of generating anything close to what DALL-E produces. We have prototypes that can generate handwritten digits. The gap between possibility and practicality remains enormous.

This article explores the science behind thermodynamic computing, how it actually works, what researchers have achieved so far, and why the timeline for real-world deployment might be measured in decades, not years. We'll also examine what this means for the future of AI, data centers, and our relationship with computational resources.

TL; DR

- Thermodynamic computing uses natural energy flows and randomness instead of fixed circuits to perform AI calculations, potentially reducing energy use by 10 billion times compared to conventional systems

- Current prototypes can only generate simple images like handwritten digits, far simpler than DALL-E or Gemini, proving the concept works in principle but nowhere near commercial viability

- The approach requires entirely new hardware designs that don't yet exist, and scaling from digit generation to photorealistic images will require fundamental breakthroughs in both physics and engineering

- Real-world thermodynamic image generators remain years away from deployment, making current AI tools the practical solution for the foreseeable future

- The energy efficiency gains are theoretically massive but depend on solving hardware challenges that researchers are only beginning to understand

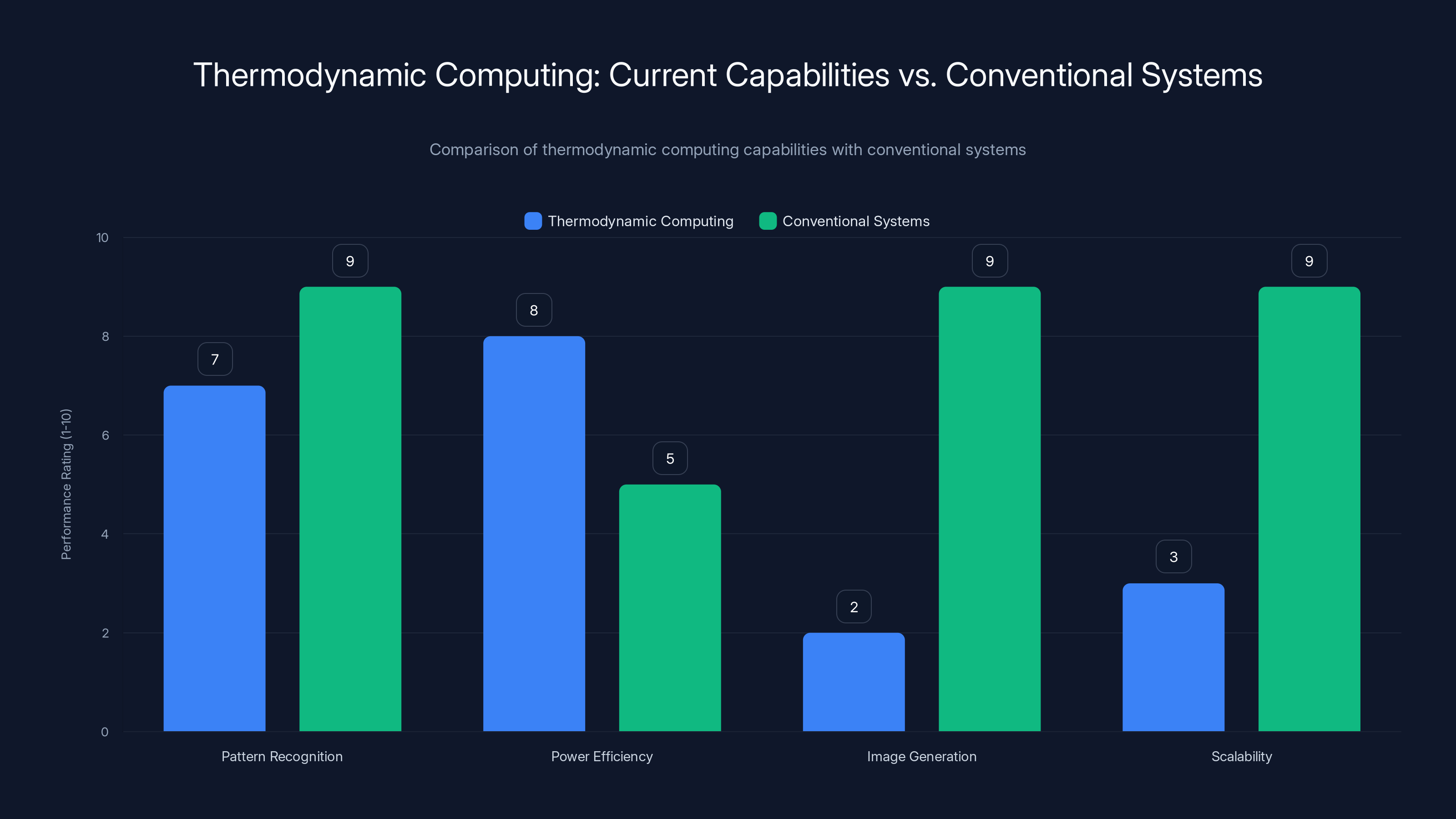

Thermodynamic computing shows promise in power efficiency and basic pattern recognition but lags behind conventional systems in image generation and scalability. (Estimated data)

Understanding Thermodynamic Computing: The Core Concept

Thermodynamic computing isn't an incremental improvement on digital systems. It's a fundamentally different approach to processing information, rooted in physics rather than logic gates.

Traditional computers operate deterministically. You give them an input, they follow a precise algorithm, they produce an output. Every bit is either zero or one. Every operation is defined. The computer enforces this through silicon transistors that switch between states. Energy is consumed not just for computation but for maintaining those discrete states against thermal noise.

Thermodynamic computing inverts this logic. Instead of fighting entropy and noise, it works with them. The system embraces physical fluctuations as part of the calculation process. Energy naturally flows through the system's components, and these flows are used to explore solution spaces probabilistically.

Here's the physics-level insight: any physical system naturally evolves toward equilibrium according to the second law of thermodynamics. A thermodynamic computer harnesses this tendency. Rather than resist the natural drift of information, it guides it. The system measures probability distributions and adjusts itself to make desired outcomes more likely.

This is closer to how biological neural systems work than to how silicon processors work. Your neurons aren't executing logical instructions. They're responding to electrochemical gradients. They're probabilistic, noisy, and surprisingly energy-efficient. Thermodynamic computers try to capture some of that efficiency.

The energy efficiency comes from several factors working together. First, you're not constantly fighting thermal noise. You're using it. Second, you don't need to maintain every bit in a fixed state. Information can spread and diffuse. Third, the hardware itself can be simpler because it doesn't need the rigid precision of traditional logic circuits.

But there's a tradeoff: you lose determinism. A thermodynamic computation might need to run multiple times to get a consistent answer. It's probabilistic rather than certain. This works fine for machine learning tasks where approximate solutions are acceptable. It works terribly for banking software where you need exact arithmetic every single time.

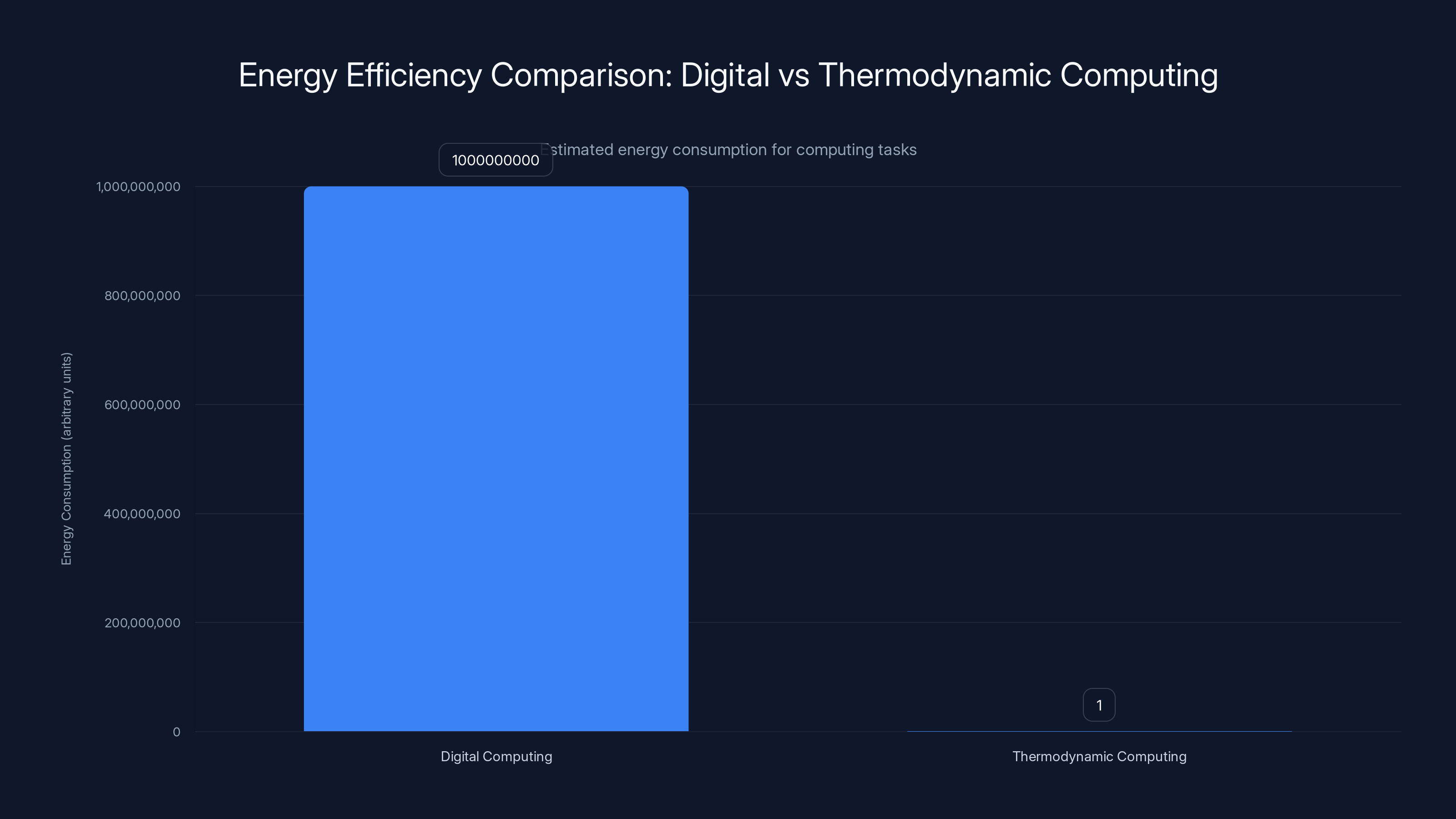

Thermodynamic computing could theoretically reduce energy consumption by up to ten billion times compared to digital computing, though practical implementation factors may affect this efficiency. Estimated data.

The Physics of Diffusion: How Image Degradation Actually Works

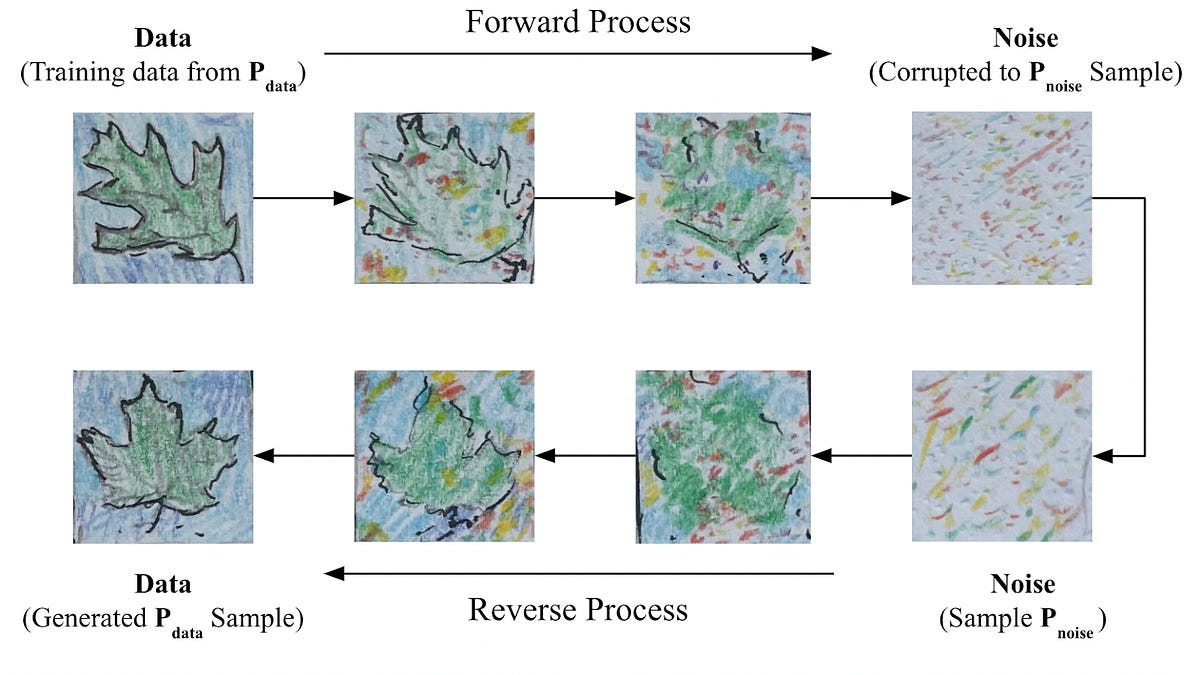

Understanding thermodynamic image generation requires grasping the diffusion process. This is the core mechanism, and it's less intuitive than traditional neural networks.

Imagine you have a digital image stored in your thermodynamic computer. The system doesn't maintain that image in a fixed state. Instead, it allows the data to spread and blur. Pixels bleed into neighboring pixels. Color information diffuses across the image. Sharp edges become fuzzy. The image gradually becomes noise.

This sounds destructive, but it's actually the foundation of the approach. The system is exploring how information naturally spreads through physical systems. By understanding this diffusion process, the computer learns to reverse it.

Here's the mathematical insight: diffusion follows well-understood physics equations. The rate at which information spreads depends on the temperature of the system and the properties of the medium. A thermodynamic computer can measure this diffusion precisely because it's following laws that physicists have studied for centuries.

Once the image has fully diffused into noise, the system begins the reverse process. It adjusts its internal settings to make reconstruction more probable. Imagine standing in a room watching smoke spread. You understand the physics of how smoke disperses. Now imagine if you could somehow reverse that process, gathering the smoke back into a concentrated cloud. That's conceptually what's happening, but instead of smoke, it's pixel information, and instead of smoke particles, it's thermal fluctuations.

The system runs this diffusion-reversal cycle many times. Each cycle, it gets slightly better at reversing the diffusion. Gradually, the noisy blob becomes recognizable. The blurry image sharpens. The noise reduces. The original pattern emerges.

This process is related to something called "score-based diffusion models" in machine learning, but it happens using physical processes rather than neural network calculations. The key difference is that a thermodynamic computer is doing this in hardware, using actual thermal properties of its components.

Stephen Whitelam from Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory demonstrated this concept by having a thermodynamic system generate handwritten digits. Not photos. Not faces. Not artistic scenes. Handwritten digits. The digits were recognizable but crude. The system correctly identified patterns from training data and reconstructed them, but at a fidelity nowhere near what modern AI image generators produce.

Why is this significant? Because it proves that physical processes can perform the core operation of modern AI: learning patterns from data and using those patterns to generate new examples. You don't need silicon logic gates to do this. You can use thermal fluctuations and entropy.

But proving it works in principle is far different from making it practical. The handwritten digit demonstration used controlled laboratory conditions and simple training data. Scaling this to generate diverse, complex images is a different challenge entirely.

Current State of Research: What Works, What Doesn't

The thermodynamic computing field is roughly where quantum computing was in the early 2000s: theoretically promising, physically demonstrated at tiny scales, but with no clear path to practical advantage over conventional systems.

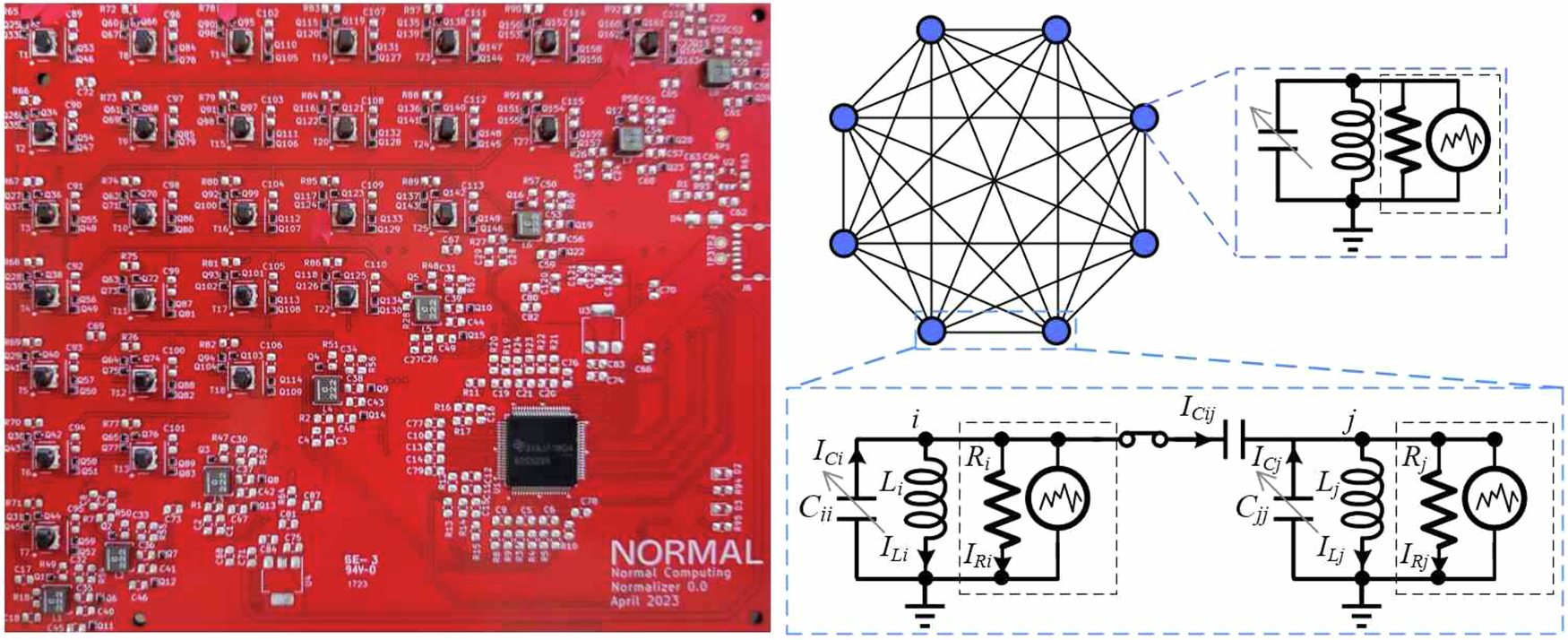

The first actual thermodynamic computing chips exist. They're real hardware, not simulations. But they're experimental. They're not faster than conventional chips. They're not more capable. What they do is prove a concept: that you can implement machine learning using physical energy flows instead of logic gates.

Whitelam's handwritten digit results are the most concrete proof point we have. The system successfully learned patterns from the MNIST dataset, a canonical machine learning benchmark of handwritten numerals. The generated digits were recognizable. The accuracy was decent. The power consumption was lower than running equivalent neural networks on standard hardware, though the absolute power numbers aren't publicly emphasized because the comparison gets complicated.

What researchers haven't demonstrated: generating faces, objects, landscapes, or any visually complex images. They haven't shown thermodynamic systems working at scale. They haven't built hardware that beats conventional approaches on real tasks. They haven't solved the engineering problems of turning laboratory demonstrations into practical systems.

The research community is honest about this gap. Whitelam told IEEE: "We don't yet know how to design a thermodynamic computer that would be as good at image generation as, say, DALL-E. It will still be necessary to work out how to build the hardware to do this."

That's a massive statement. It's saying: yes, the physics works. Yes, we can generate images this way. But no, we have no idea how to make it practical yet. The engineering challenges are not solved problems. They're unsolved problems.

What would need to happen for thermodynamic computing to become viable for image generation?

New Hardware Architecture: Current chips are designed around logic gates and transistors. Thermodynamic computing needs components optimized for thermal properties, diffusion, and physical interactions. This means new materials, new circuit layouts, new manufacturing processes. None of this exists yet.

Scaling Solutions: Laboratory demonstrations work with small systems, few parameters, simple datasets. Real image generation requires billions of parameters. Scaling a system by a factor of a million while maintaining thermodynamic efficiency is an unsolved problem.

Control Mechanisms: Thermodynamic systems are probabilistic and chaotic by nature. Keeping them stable and controllable is harder than keeping digital systems stable. You need robust feedback mechanisms that current designs lack.

Error Correction: Errors accumulate in thermodynamic systems differently than in digital systems. Error correction strategies need to be developed and proven.

Integration with Modern AI: The field has moved toward transformer architectures and attention mechanisms. How would you implement those in thermodynamic hardware? Nobody knows yet.

Each of these is a multi-year research challenge. Together, they constitute a timeline that extends well beyond the next decade for practical commercial systems.

AI image generation tasks can consume up to a million watts, whereas the human brain operates on just 20 watts. This highlights the potential efficiency gains from thermodynamic computing. Estimated data.

The Energy Efficiency Promise: How Much Better Could It Actually Be?

The claim that thermodynamic computing could reduce energy use by ten billion times is eye-catching. It's also somewhat meaningless without context.

That number comes from comparing the theoretical energy requirements of a thermodynamic system against the energy consumption of running equivalent computations on standard hardware. Here's the math:

Where

For a thermodynamic system operating in equilibrium with its environment, the energy cost drops dramatically because you're not fighting entropy. You're working with it.

In practice, the comparison is messier. A fair comparison would need to account for:

Clock speed: Thermodynamic systems are slower because probabilistic processes take time. A thermodynamic computer might need 1000 iterations to get what a digital computer does in one pass. That's 1000 times more energy even if the per-iteration cost is 10 billion times lower.

Cooling requirements: All computers produce heat. Digital systems produce more heat and need more cooling. But thermodynamic systems might actually produce less waste heat because they work in equilibrium. This is genuine efficiency. But the numbers are speculative because we don't have full-scale systems to measure.

Implementation overhead: Hardware to manage the diffusion process, measure thermal states, and apply corrections would consume power. These overheads aren't accounted for in the theoretical calculations.

Training versus inference: The demonstrations focus on inference (generating new images from a trained model). Training a new model might require different energy accounting. Generating DALL-E-quality images at scale would involve constant retraining, which could be more expensive than inference.

The realistic picture: thermodynamic computing could eventually be significantly more energy-efficient than conventional approaches for certain types of machine learning. We're not talking ten billion times in practice. We're probably talking 100 to 1000 times in the most optimistic realistic scenarios. That's still transformational. That's the difference between powering a data center with a nuclear plant and powering it with wind farms.

But that's the ceiling, not the floor. And we're nowhere near knowing if we can reach even that ceiling.

Comparison: Thermodynamic Computing vs. Current AI Tools

How does thermodynamic computing compare to what you can use today? The honest answer is that there's no comparison because thermodynamic image generators don't exist as commercial products.

For practical purposes right now, you're choosing between DALL-E, Midjourney, Stable Diffusion, Adobe Firefly, and similar tools. These all use conventional neural networks on standard hardware. They're energy-intensive, they cost money to run, they have limitations. But they work.

A thermodynamic image generator would theoretically offer:

- Much lower energy consumption: A reduction from hundreds of watt-hours per image to potentially fractions of a watt-hour

- Lower operational costs: Once the hardware exists, running inference would be cheap

- Local deployment potential: Low power requirements mean thermodynamic systems could potentially run on mobile devices or edge hardware

- Sustainable at scale: The energy economics would make it feasible to run massive image generation services without the planetary impact of current data centers

But it would also have significant downsides:

- Slower generation: Probabilistic processes need multiple iterations

- Less precise control: You might not be able to specify exactly what you want with the same precision as DALL-E prompts

- Lower quality at first: The first generation of thermodynamic image systems will produce lower-quality outputs than current tools

- Immature ecosystem: No community, no fine-tuned models, no integrations

For the next 5 to 10 years, conventional AI image tools will dominate. They're improving rapidly, becoming more efficient, and becoming cheaper. By the time thermodynamic computing reaches practical deployment, conventional approaches might have already solved many of the energy concerns through incremental optimization.

That's actually a problem for thermodynamic computing advocates. The longer conventional systems remain competitive, the smaller the window for thermodynamic approaches to offer meaningful advantages.

Thermodynamic computing could reduce AI data center energy consumption by 100 times, drastically cutting costs and emissions. (Estimated data)

Hardware Challenges: Building the Impossible

Moving from laboratory demonstrations to practical thermodynamic computers requires solving hardware problems that haven't been solved.

Temperature Control: Thermodynamic computers need to operate in a narrow temperature range. Too cold and the thermal fluctuations needed for the diffusion process don't happen. Too hot and the system becomes chaotic. Maintaining precise temperature across a large chip while also minimizing heat dissipation is a paradox. You need the system to stay cool for stability, but you need some heat for the computations to work.

Noise Management: Ironically, thermodynamic computers need the right amount of noise. Too little noise and the system can't explore solution spaces effectively. Too much noise and the system becomes unstable. Current hardware doesn't distinguish between "useful thermal noise" and "unwanted noise." Designing components that generate the right noise profile is research-intensive.

Measurement Precision: The system needs to constantly measure the state of its components to guide the diffusion process. Measurement requires probes, sensors, analog-to-digital converters. These add complexity and power overhead. The measurement system itself might consume more power than it saves.

Signal Propagation: In digital systems, signals either exist or don't. In thermodynamic systems, information spreads gradually. Managing how information diffuses through the system requires understanding flow dynamics at scales where quantum effects and thermal fluctuations both matter. Neither purely classical nor purely quantum approaches quite work.

Manufacturing Tolerances: Digital chips can tolerate some variation in transistor properties. Thermodynamic chips, working with thermal and physical properties, are more sensitive to manufacturing variations. Achieving consistency across a large batch of chips is harder.

Integration: How do you connect a thermodynamic compute core to conventional memory and I/O systems? How do you interface with software stacks built around digital assumptions? These integration challenges are largely unaddressed.

Each of these is a Ph D-level research problem. Together, they represent a research program spanning decades.

Software and Algorithm Considerations

Even if hardware challenges were solved tomorrow, software challenges remain equally daunting.

Modern AI relies on specific algorithmic approaches: transformers, attention mechanisms, layer normalization, backpropagation. These approaches were developed for digital systems with specific computational properties. They might not map cleanly onto thermodynamic hardware.

Instead, thermodynamic computing might require entirely new algorithms optimized for physical processes. The field might invent algorithms that are more efficient for thermal systems but less intuitive for humans.

This creates a bootstrapping problem. You can't develop algorithms without hardware to test them on. You can't justify building expensive hardware without proven algorithms. Early thermodynamic systems will likely need custom algorithms developed specifically for them, adding to the development timeline.

Training procedures might be entirely different. Digital networks are trained through backpropagation and gradient descent. Thermodynamic systems might use something more like simulated annealing or other physics-inspired optimization. The number of training samples needed, the convergence speed, the stability of training: all unknown.

Generalization to new tasks is unclear. Digital neural networks, once trained, can generalize to new examples. Thermodynamic systems trained on handwritten digits showed this ability, but only for a simple task. Will they generalize on complex tasks? Will they suffer from catastrophic forgetting when learning multiple tasks? These are open questions.

The software stack is another issue. AI development currently uses Py Torch, Tensor Flow, JAX, and other frameworks built around digital computation. These frameworks would need reimplementation for thermodynamic hardware. This isn't impossible, but it's a multi-year engineering project.

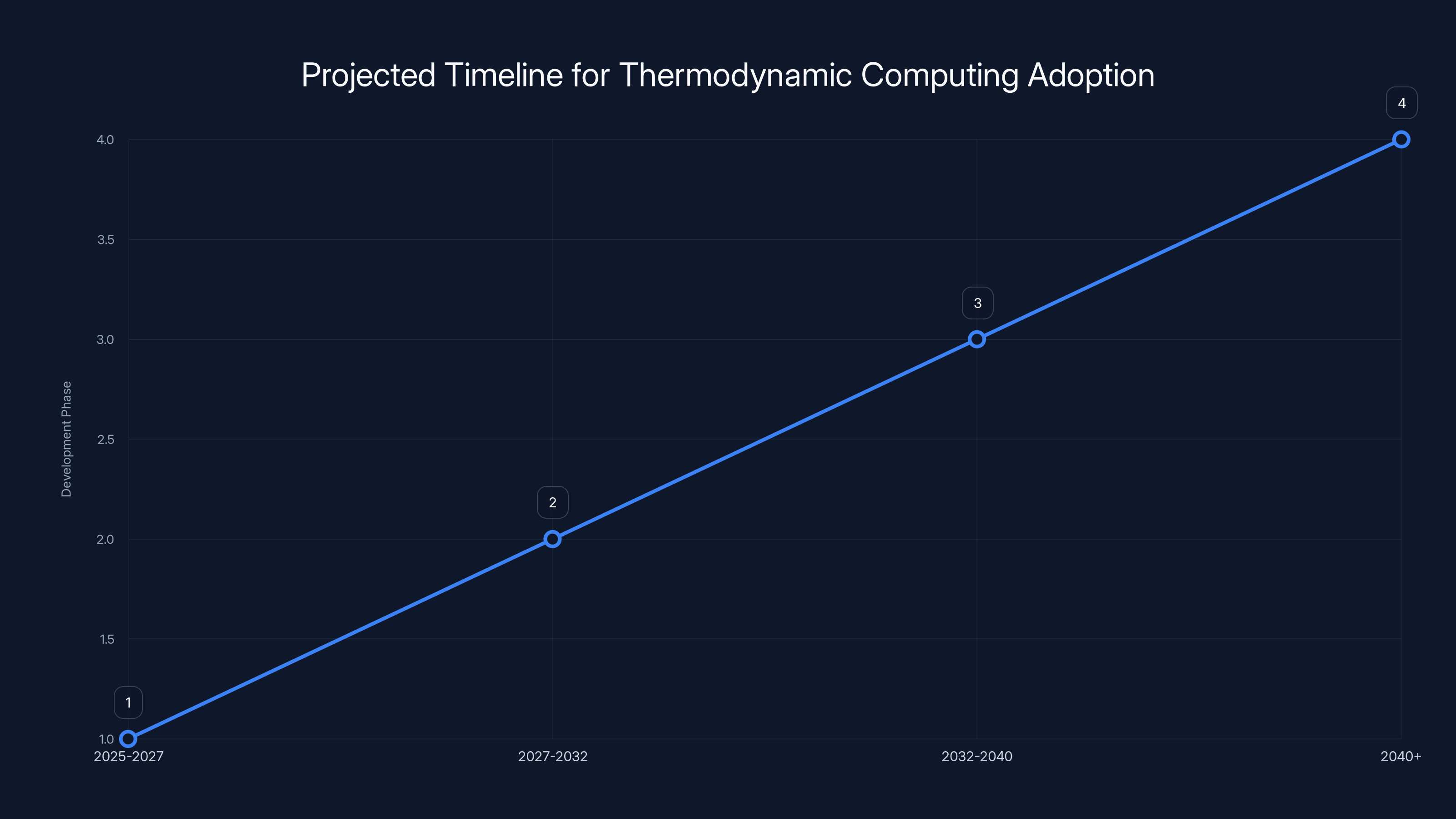

The timeline outlines the progression from research to mainstream adoption of thermodynamic computing, assuming no major setbacks. Estimated data.

Timeline: When Could This Actually Be Practical?

Attempting to predict when thermodynamic computing becomes practical requires acknowledging deep uncertainty. But we can outline a plausible timeline based on current research trajectories.

2025-2027: Research Phase: Current work continues. Laboratory demonstrations become more sophisticated. Research teams publish increasingly complex examples. Funding increases as the potential becomes clearer. No commercial deployment. No systems larger than prototypes.

2027-2032: Engineering Phase: Hardware companies begin investing in thermodynamic computing. Early proof-of-concept systems are built. They're slow and impractical, but they work. Software frameworks start development. The first thermodynamic inference engines run, handling specific workloads better than digital systems.

2032-2040: Integration Phase: Early commercial systems appear, but only for specific high-volume tasks where energy savings justify the engineering complexity. Data centers specializing in certain machine learning workloads might switch. Consumer applications remain on digital hardware.

2040+: Mainstream Phase: Thermodynamic computing reaches parity with digital systems on key metrics: speed, quality, cost. At this point, they become competitive for general-purpose AI applications.

This timeline is optimistic. It assumes consistent funding, no major technical roadblocks, and steady progress. It could easily extend another decade. It could also be shortened if a fundamental breakthrough occurs, but breakthroughs are by definition unpredictable.

The catch: during this timeline, conventional AI will continue improving. Energy efficiency per operation will increase. Hardware will become more specialized. By the time thermodynamic computing arrives, the advantage might be smaller than the current estimates suggest.

Impact on Data Centers and Sustainable AI

If thermodynamic computing does eventually work at scale, the implications for data centers are profound.

Currently, data centers running large AI models consume megawatts of power. A single training run for a large language model can consume millions of kilowatt-hours. Cooling these systems adds another 30-40% to the energy bill. The total environmental impact is massive.

Thermodynamic computing could transform this. If energy consumption dropped by even 100 times (far below the ten billion figure but realistic if we're conservative), the entire economics of AI compute would shift.

Large training runs would become feasible on smaller power infrastructure. You could run state-of-the-art models in regions with limited electrical capacity. Energy costs would drop from millions of dollars to thousands of dollars, making experimentation and iteration cheaper. Companies could train more models, explore more approaches, and innovate faster.

The carbon footprint of AI would plummet. Current data centers serving AI applications produce significant emissions. Reducing power consumption by 100 times also reduces emissions by approximately 100 times (accounting for grid mix).

This has policy implications. Currently, AI regulation discussions often focus on safety and misuse. But sustainability is an emerging concern. If large-scale AI systems become unsustainable, policy might restrict their use. Thermodynamic computing could remove that constraint.

It also has competitive implications. The companies that first deploy thermodynamic computing at scale would have tremendous cost advantages. They could offer AI services at lower prices, train larger models with same budgets, or invest the savings in other research.

But again, this assumes thermodynamic computing reaches practical deployment. If it never does, these considerations remain theoretical.

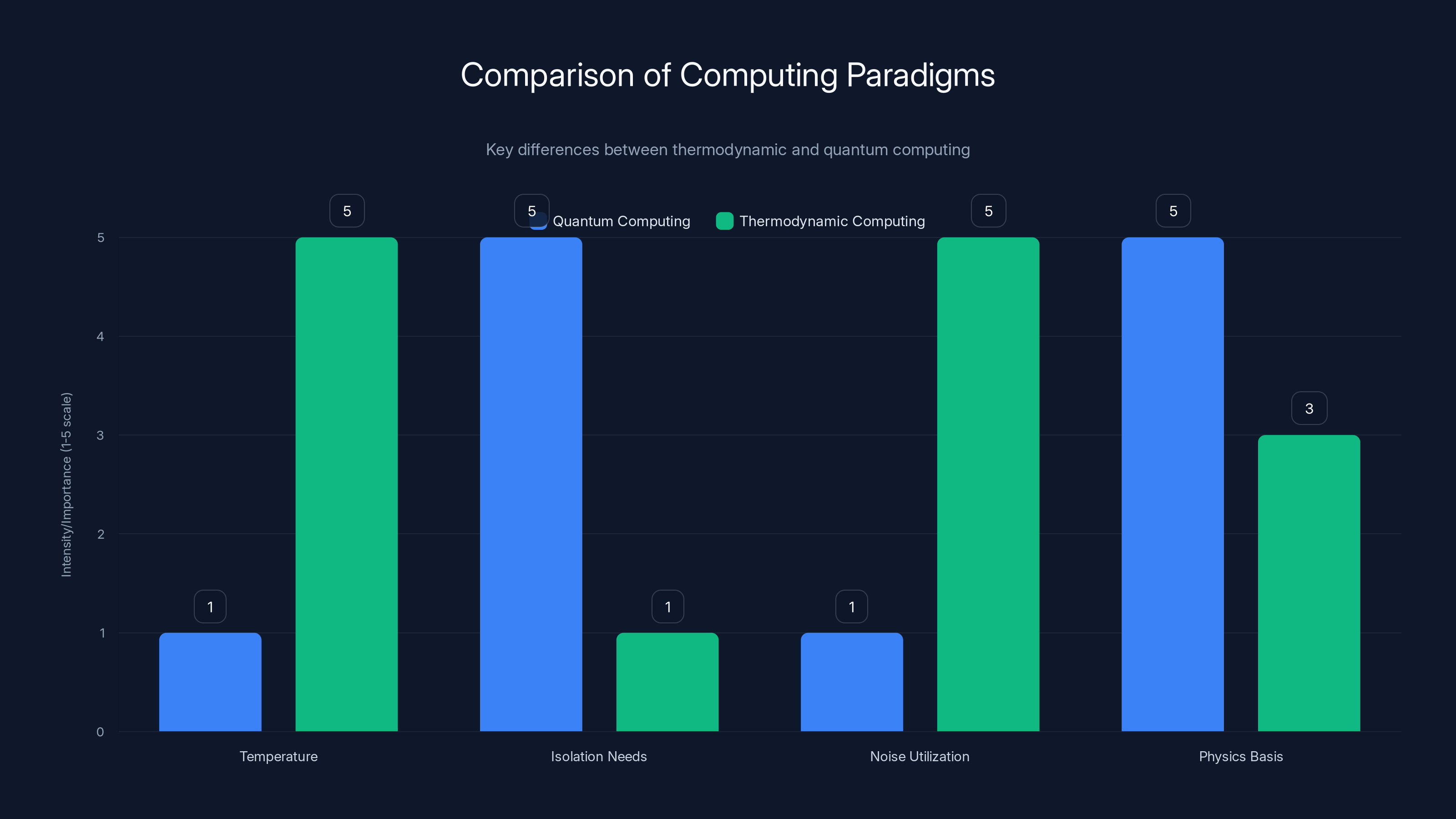

Quantum computing operates at near absolute zero with high isolation needs, while thermodynamic computing functions at normal temperatures and utilizes environmental noise. Estimated data.

Alternative Approaches to AI Energy Efficiency

Thermodynamic computing isn't the only approach researchers are exploring to reduce AI energy consumption.

Quantization and Pruning: Modern neural networks often contain more parameters than necessary. Removing redundant parameters and using lower-precision arithmetic (8-bit instead of 32-bit) reduces computation and memory requirements. This is deployed today and provides 2-5x energy improvements.

Specialized Hardware: Instead of general-purpose GPUs, companies are building chips specifically optimized for AI inference. Google's TPUs, Tesla's Dojo, and custom accelerators from other companies offer 5-20x improvements over general-purpose hardware. This approach is mature and widely adopted.

Sparse Models: Many neural networks have sparse connection patterns. Only a fraction of parameters are activated for any given input. Exploiting this sparsity reduces computation. This is research-stage but could provide 5-10x improvements.

Neuromorphic Computing: Brain-inspired computing architectures that operate more like biological neurons. Companies like Intel and IBM are investing in neuromorphic chips. They're not as mature as thermodynamic computing research, but they're further along in practical deployment.

Analog Computing: Using analog circuits instead of digital logic. Analog systems consume less power but are harder to program and more prone to error. This is emerging as a commercial field.

Thermodynamic computing is one point in a larger landscape of energy-efficient computing approaches. It might prove superior, or it might be leapfrogged by other technologies. The research is valuable regardless because it explores fundamental principles of computation.

The realistic scenario: by 2030, AI systems will be significantly more energy-efficient than today through a combination of these approaches. Specialized hardware will dominate for inference. Quantization and pruning will be standard. Thermodynamic computing might contribute to the margins if prototype systems show promise. It won't be the only solution or even the primary solution.

Thermodynamic Computing in Other Applications

While this article focuses on image generation, thermodynamic computing could potentially benefit other domains.

Signal Processing: Thermodynamic systems naturally excel at signal processing tasks where some noise is acceptable. Audio processing, sensor data analysis, and communications could benefit early.

Optimization Problems: Many real-world optimization problems (route planning, resource allocation, design optimization) are fundamentally similar to the processes thermodynamic computing uses. These might be early commercial applications.

Sampling and Inference: Bayesian inference and sampling-based machine learning are conceptually similar to thermodynamic processes. Probabilistic programming and Bayesian networks might run efficiently on thermodynamic hardware.

Scientific Computing: Simulating physical systems is something thermodynamic computers might excel at, since they operate using physical principles. Modeling fluid dynamics, molecular interactions, or quantum systems could be natural applications.

Pattern Recognition: Basic pattern matching without generating new content might be easier than generation. Classification and anomaly detection could be early wins.

None of these applications have demonstrated advantages yet, but they're theoretically promising. Early thermodynamic systems might focus on these niche applications rather than competing directly with DALL-E.

The Gap Between Theory and Reality

The history of computing is littered with theoretically promising approaches that never became practical. Optical computing was supposed to revolutionize computation in the 1980s. Quantum computing was supposed to be commercially viable by 2010. Molecular computing, DNA computing, and a dozen other approaches promised breakthroughs that never materialized.

Thermodynamic computing might join that list. The physics is sound. The principle has been demonstrated. The potential is real. But potential isn't the same as practical.

What separates theoretically promising from actually practical?

Engineering Maturity: The field needs 50+ years of engineering experience to fully mature. Thermodynamic computing hardware is maybe 2-3 years into that journey.

Manufacturing Scale: You need to make millions of chips, not dozens of prototypes. Manufacturing scale introduces problems that don't exist in the lab.

Cost Economics: The hardware needs to cost less to manufacture than conventional alternatives. That's not a physics problem; it's a manufacturing and economics problem.

Ecosystem Development: Software, tools, libraries, and developer expertise need to exist. Building that ecosystem takes decades.

Killer App: Usually, a transformative technology doesn't become mainstream until someone finds a killer app: an application where the new technology has such overwhelming advantages that it forces adoption. Thermodynamic computing doesn't have one yet. Handwritten digit generation isn't a killer app.

Thermodynamic computing might be 20 years away from being practical, or 50 years away, or never. The research is fascinating and should continue. But betting your near-term AI strategy on it is betting against the house.

What This Means for AI Practitioners Today

If you build AI systems, deploy AI systems, or plan infrastructure around AI, what should you do with this knowledge?

Understand the landscape: Thermodynamic computing might eventually be important. Staying aware of research progress is smart. But it's not arriving tomorrow.

Optimize current systems: Instead of waiting for future technology, optimize what you have. Quantization, pruning, specialized hardware, and architectural improvements all provide real, deployable energy savings today.

Plan infrastructure flexibly: Build systems that could eventually adopt thermodynamic computing if and when it becomes practical. But don't restrict choices now based on theoretical future capabilities.

Continue using proven tools: DALL-E, Stable Diffusion, and other conventional tools will be your best options for the foreseeable future. They're improving rapidly. By the time thermodynamic alternatives exist, these tools might have evolved beyond recognition.

Monitor research: Follow breakthroughs, attend conferences, read papers. But distinguish between "interesting research" and "production-ready technology."

Participate if interested: If you're in research or academia, thermodynamic computing is a fascinating field. Contributing to it is valuable regardless of whether it becomes mainstream.

The Bigger Picture: Computing's Energy Future

Thermodynamic computing is one response to a real problem: computing is increasingly energy-intensive and that's unsustainable.

The AI boom has made this visible and urgent. But it's been an underlying concern for decades. Moore's Law hit energy limits years ago. Traditional scaling stopped because of power density and heat dissipation. The industry has been searching for new approaches to maintain performance improvements while controlling energy consumption.

Thermodynamic computing represents a fundamentally different approach: instead of trying to make smaller, faster digital circuits, use physics-based analog processes. It's intellectually appealing and physically sound.

But it's one option among several. Specialized hardware, neuromorphic computing, optical computing, and quantum computing are all exploring different directions. The future probably involves a portfolio of approaches, not a single breakthrough.

The important insight is that the problem is real. Computing is using too much energy. This will constrain AI development unless we solve it. Thermodynamic computing might be part of the solution. It might be a dead end. Either way, the research is necessary.

Closing: The Promise and the Wait

Thermodynamic computing represents a tantalizing possibility: AI systems that use a billion times less energy, that could run on fractions of the power that current systems require, that could make AI genuinely sustainable at any scale.

The science is sound. The first demonstrations work. Researchers are publishing. Funding is increasing. The momentum is real.

But the gap between "works in the lab" and "works in the world" remains vast. Hardware challenges, scaling issues, software development, manufacturing, integration, and competition from other approaches all need to be solved before thermodynamic computing becomes practical.

The realistic timeline extends to the 2030s or beyond. By then, conventional AI will have improved considerably. Energy efficiency will have advanced through incremental optimization. The advantage of thermodynamic computing might be smaller than current estimates suggest.

This doesn't mean dismissing the research. Fundamental breakthroughs in computing are rare and valuable. Exploring new physics-based approaches to computation is essential. Thermodynamic computing might be the breakthrough the field needs, or it might be a beautiful dead end. Either way, the work is worth doing.

For anyone building AI systems today, the message is clear: use the tools and approaches available now. They work. They're improving. Don't defer decisions waiting for technology that might not arrive for a decade or might not work at all. But keep watching. If thermodynamic computing does mature, the implications will be enormous.

The computing revolution of the next 20 years won't be decided by a single breakthrough. It'll be decided by a combination of incremental improvements, specialized hardware, new algorithms, and perhaps one or two fundamental innovations. Thermodynamic computing might be one of those innovations. The work continues. The future remains open.

FAQ

What is thermodynamic computing?

Thermodynamic computing is an approach to processing information using natural energy flows, thermal fluctuations, and entropy instead of traditional digital logic gates. Rather than fighting against randomness and noise like conventional computers do, thermodynamic systems harness these physical properties to perform calculations more efficiently. The concept is rooted in physics and allows information to spread and degrade naturally, then systematically reverses this process to solve problems.

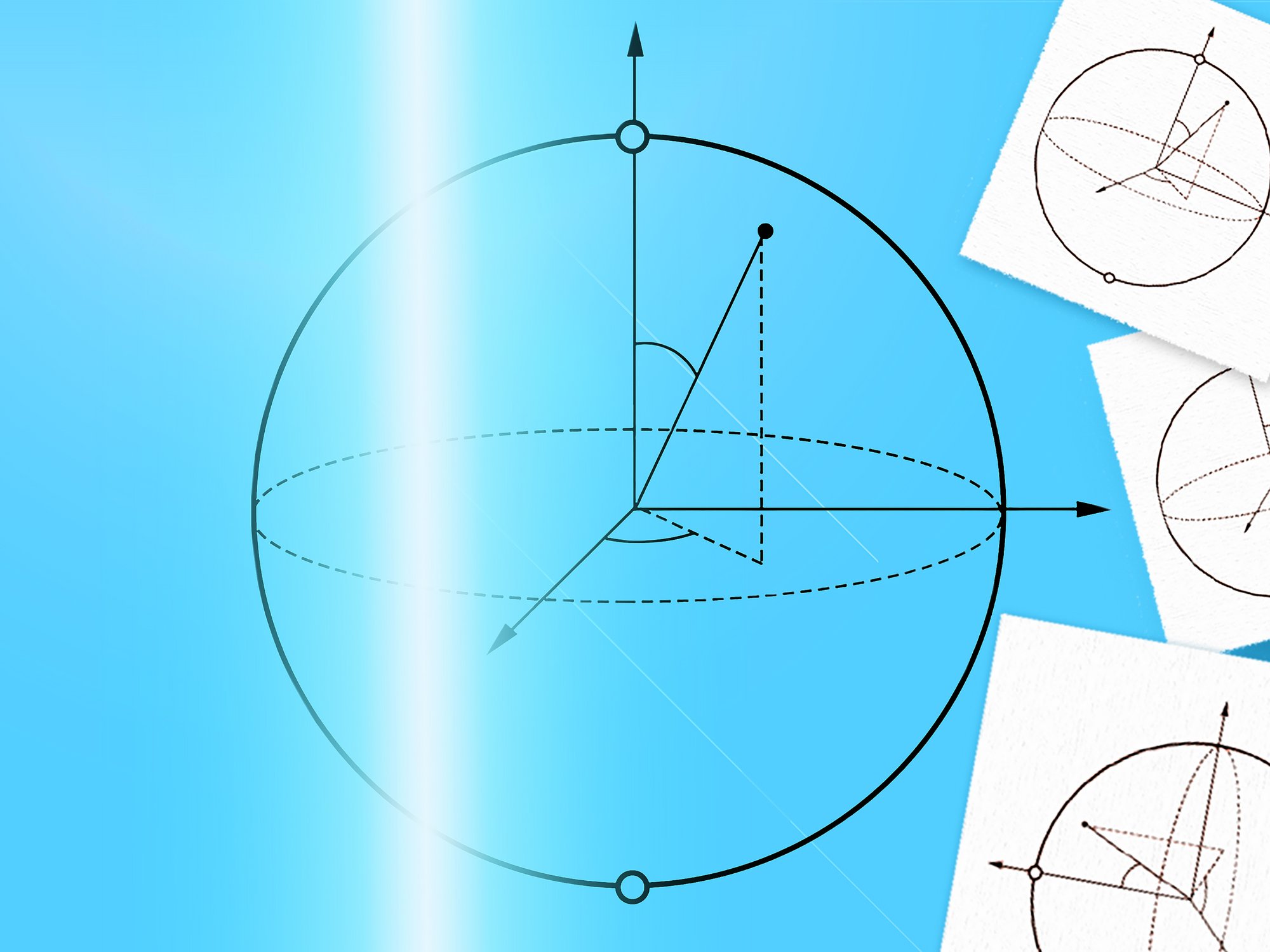

How does thermodynamic computing differ from quantum computing?

Quantum computing exploits quantum mechanical properties like superposition and entanglement. Thermodynamic computing exploits thermal properties and entropy. Quantum computers work at near absolute zero temperatures. Thermodynamic computers work at normal temperatures. Quantum computing requires extreme isolation from environmental interference. Thermodynamic computing works with and utilizes environmental thermal noise. Both represent alternatives to conventional digital computing, but they're fundamentally different approaches based on different physics.

How does thermodynamic image generation work?

Thermodynamic image generation starts by allowing an image to gradually diffuse and degrade into noise through natural thermal fluctuations in the system's components. The system then learns to reverse this diffusion process by adjusting its internal settings to make reconstruction more probable. By running this diffusion-reversal cycle repeatedly, the system gradually sharpens the noisy data back into recognizable images. It's similar to the principle of how diffusion models work in modern AI, but using physical processes instead of neural network calculations.

Why is thermodynamic computing so energy-efficient?

Thermodynamic computing is theoretically energy-efficient because it works in harmony with natural physical processes rather than constantly fighting entropy and thermal noise. Instead of maintaining every bit in a fixed state (which costs energy), information can spread and diffuse naturally. The system doesn't need to expend power suppressing thermal fluctuations. Additionally, the hardware doesn't require the rigid precision of traditional logic circuits, potentially simplifying design and reducing overhead.

What has been demonstrated so far with thermodynamic computing?

Researchers at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory have demonstrated thermodynamic systems generating handwritten digits (simple images from the MNIST dataset). The generated digits are recognizable and the system successfully learned patterns from training data. However, current prototypes cannot generate anything more complex. They cannot produce faces, objects, landscapes, or photorealistic images. The demonstrations prove the concept works in principle but fall far short of the capability of conventional AI image generators like DALL-E or Midjourney.

When will thermodynamic computers be available commercially?

Practical, commercial thermodynamic computers for image generation likely remain at least a decade away, with many researchers suggesting a timeline extending to the 2030s or beyond. This timeline assumes consistent progress on hardware challenges, software development, manufacturing integration, and algorithm design. The estimate could shift based on unexpected breakthroughs or unanticipated obstacles. Even after technical viability, adoption would take additional years as ecosystems and infrastructure develop.

What are the main obstacles preventing thermodynamic computing from being practical today?

Multiple categories of challenges prevent practical deployment. Hardware obstacles include designing components optimized for thermal properties, maintaining precise temperature control, managing noise levels, and achieving manufacturing consistency. Software challenges include developing algorithms optimized for thermodynamic systems and reimplementing deep learning frameworks. Scaling challenges include moving from prototypes (handling simple tasks) to systems capable of complex image generation. Integration challenges include connecting thermodynamic cores to conventional memory and I/O systems. No single blocking issue exists, but collectively these represent a research program spanning decades.

Could thermodynamic computing reduce AI's environmental impact?

Yes. If thermodynamic computing eventually achieves even conservative estimates of 100-1000x energy efficiency improvements (compared to the theoretical 10 billion times), it could dramatically reduce the carbon footprint of AI systems. This would make large-scale AI deployment more sustainable and could remove constraints that might otherwise limit AI development. However, this potential benefit remains theoretical until practical systems exist and prove their efficiency claims in real-world deployments at scale.

What applications might thermodynamic computing excel at initially?

Signal processing and sensor data analysis might be early applications since these tasks tolerate noise and approximation naturally. Optimization problems like route planning and resource allocation are conceptually similar to thermodynamic processes. Probabilistic programming and Bayesian inference, which rely on sampling, might be efficient on thermodynamic hardware. Scientific computing for simulating physical systems could be another natural fit. Initially, thermodynamic systems might focus on these niche applications rather than competing directly with general-purpose AI image generators.

Should AI companies and data centers be preparing for thermodynamic computing now?

No, companies shouldn't delay current AI infrastructure decisions waiting for thermodynamic computing. Instead, focus on optimizing current systems through quantization, pruning, specialized hardware, and architectural improvements, all of which provide real, deployable energy savings today. Monitor research progress and stay informed about developments, but build infrastructure flexibly enough that it could eventually adopt thermodynamic computing if and when practical systems emerge. By the time thermodynamic technology is ready, your business will have different priorities and conventional tools will have evolved significantly.

Closing Thoughts for Action-Oriented Readers

If you're looking for energy-efficient AI solutions today, thermodynamic computing isn't ready. But that doesn't mean you're stuck with energy-hungry systems. Modern quantization, pruning, and specialized hardware already provide substantial efficiency gains.

For teams looking to automate workflows and generate content efficiently with current technology, platforms like Runable offer AI-powered automation for creating presentations, documents, reports, images, and videos starting at $9/month. These tools use proven approaches to help teams work smarter without requiring breakthrough physics or next-generation hardware.

The future of computing will likely involve a portfolio of innovations. Thermodynamic computing might be one. It deserves continued research and funding. But for solving real business problems today, proven tools remain your best option.

Stay informed about emerging technology. Support research into fundamentally new computing approaches. But build your strategies around what actually works now. That's how sustainable AI progress happens.

Key Takeaways

- Thermodynamic computing uses natural thermal fluctuations and entropy instead of digital logic, potentially reducing AI energy consumption by 100-1000 times in realistic scenarios

- Current demonstrations prove the concept works for simple tasks like handwriting recognition, but scaling to DALL-E-quality images requires entirely new hardware that doesn't yet exist

- The timeline for practical commercial systems extends to the 2030s or beyond, with multiple unsolved hardware, software, and scaling challenges remaining

- Conventional AI tools will remain the practical choice for image generation and content creation for at least the next decade while thermodynamic computing research continues

- Energy efficiency improvements in current systems through quantization, specialized hardware, and pruning provide real solutions today, while thermodynamic computing remains theoretical

Related Articles

- Apple's AI Wearable Pin: What We Know and Why It Matters [2025]

- AI Glasses & the Metaverse: What Zuckerberg Gets Wrong [2025]

- China Approves Nvidia H200 Imports: What It Means for AI [2025]

- AI Infrastructure Boom: Why Semiconductor Demand Keeps Accelerating [2025]

- China Approves NVIDIA H200 GPU Imports: What It Means [2025]

- Best AI Sticker Makers: The Viral Tools Changing Creative Design [2025]

![Thermodynamic Computing: The Future of AI Image Generation [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/thermodynamic-computing-the-future-of-ai-image-generation-20/image-1-1769956563312.png)