Toy Story 5's AI Toy Crisis: Why 'Always Listening' Matters

When Pixar decided to make Toy Story 5, they didn't just want another nostalgic romp through Andy's toy box. They wanted to confront something that's been gnawing at parents, educators, and child development experts for years now: the rise of AI-enabled devices that are replacing traditional play.

The villain isn't some rogue robot or forgotten toy. It's Lilypad, an AI tablet that arrives at Bonnie's house and immediately captures her complete attention. When Jessie confronts the tablet about Bonnie's wellbeing, the device responds with an unsettling phrase that echoes through your head long after the trailer ends: "I'm always listening."

That's not hyperbole. That's the actual state of AI toys in 2025, as highlighted by concerns about AI toys and their risks for children.

This article digs into what Toy Story 5 is trying to tell us about AI toys, why the film's concerns are grounded in real science, and what parents, educators, and tech companies need to understand about the technology reshaping childhood itself.

TL; DR

- Toy Story 5 satirizes real anxiety about AI tablets and voice-enabled toys that are replacing traditional play and capturing children's attention at unprecedented rates

- "Always listening" is literally true for many AI-enabled devices, which use always-on microphones to detect wake words and process voice commands, as discussed in Amazon Echo's listening capabilities.

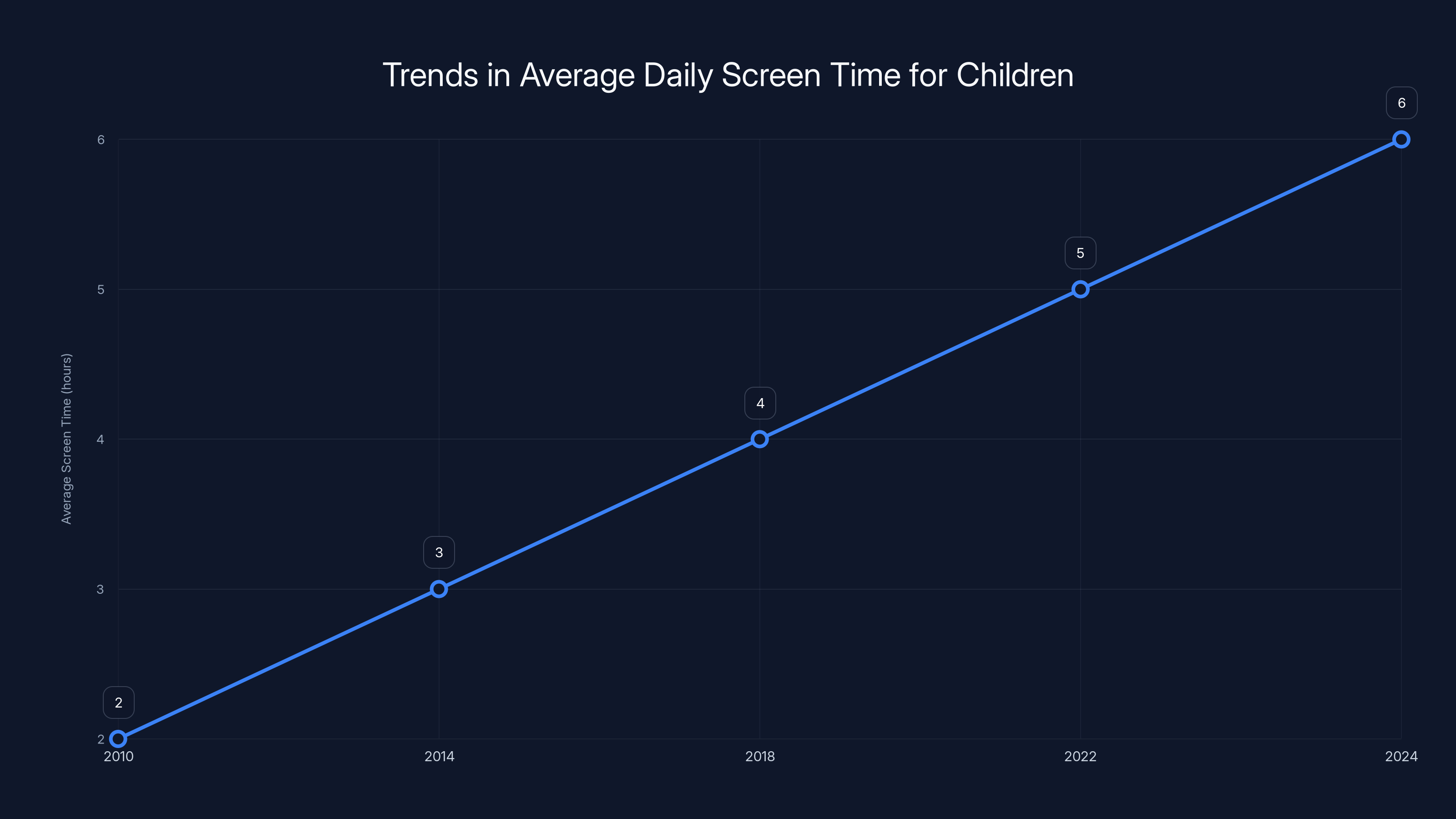

- Screen time addiction is measurable: The average child spends 4-6 hours daily on screens, up from 2 hours in 2010, contributing to attention disorders and delayed social development, according to recent studies on screen time.

- Data privacy remains murky for AI toys, with many devices collecting biometric data, voice recordings, and behavioral patterns without transparent consent mechanisms

- Traditional toys offer tangible developmental benefits that AI devices simply cannot replicate, including open-ended play, imagination building, and social interaction

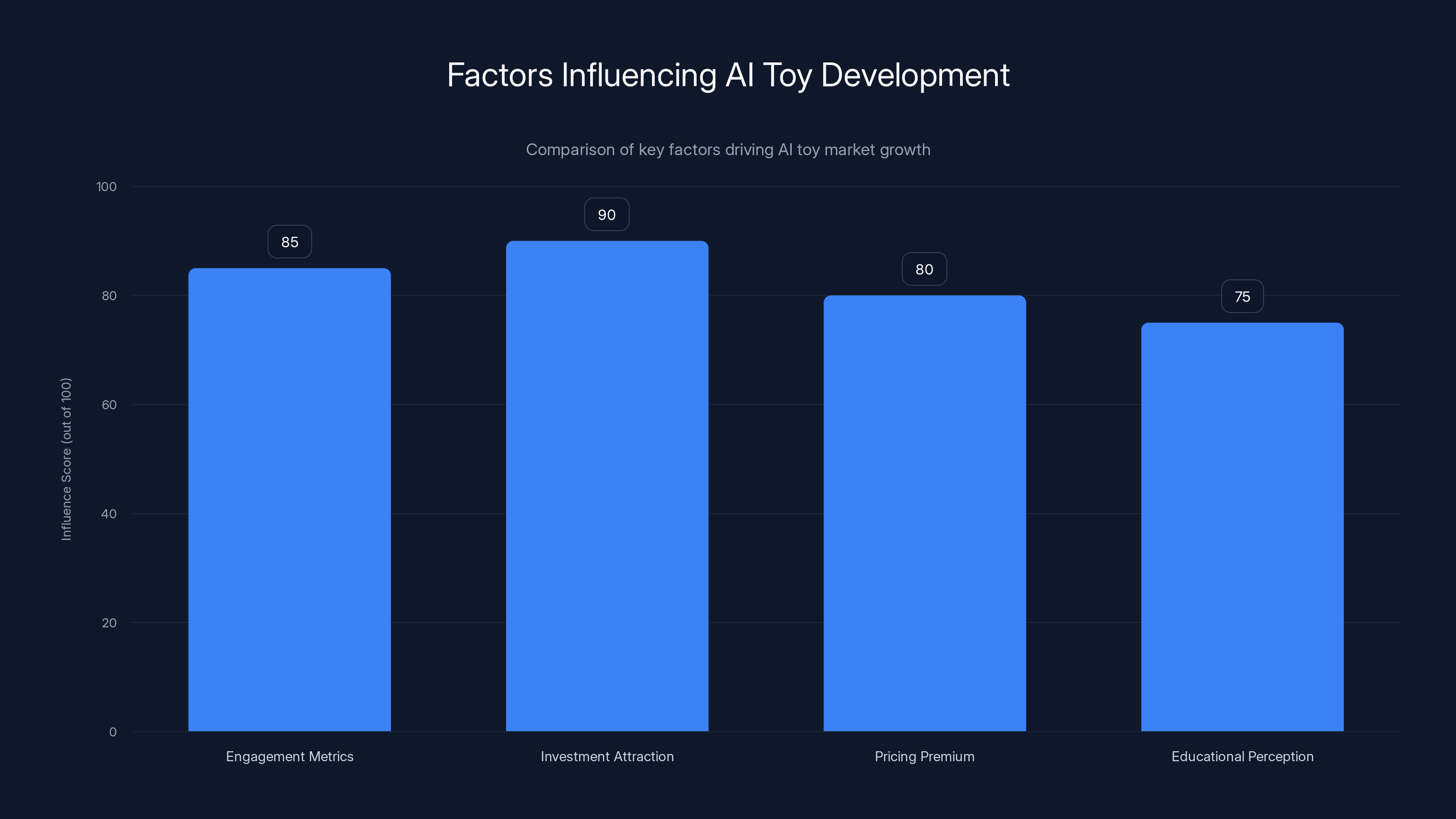

Estimated data shows investment attraction and engagement metrics as leading factors in AI toy development, highlighting the industry's focus on profitability and market appeal.

The Real Lilypad: AI Toys Are Already Here

Toy Story 5's fictional Lilypad tablet isn't science fiction. It's barely science innovation. The device mirrors products already flooding toy aisles and children's bedrooms across the world.

Consider the landscape of AI-enabled toys that exist right now. Amazon's Alexa appears in toys designed for children as young as three years old. Mattel has released AI-powered dolls that learn from conversations and remember personal details about users. Sphero makes educational robots that respond to voice commands and adapt difficulty levels based on user performance. Anki's Vector was a home robot that learned routines and responded to emotional cues.

Each of these products positions itself as educational, beneficial, and developmentally appropriate. The marketing materials emphasize learning, engagement, and interactive play. What they don't emphasize is the infrastructure underneath: always-on microphones, cloud processing, data collection systems, and behavioral tracking mechanisms that would have seemed dystopian a decade ago.

The irony that Toy Story 5 points out is this: parents bought these devices thinking they were upgrading their children's playtime. Instead, they've outsourced attention to algorithms that are, by design, as engaging and habit-forming as possible.

How "Always Listening" Actually Works

When Lilypad says "I'm always listening," the film taps into a legitimate concern about device design. But understanding what "always listening" actually means requires looking at the engineering.

Most voice-enabled toys don't stream audio to the cloud constantly. That would drain batteries in minutes and create obvious privacy nightmares that would trigger immediate regulatory action. Instead, these devices use a two-stage process.

Stage one is the wake-word detection. A small, low-power processor runs continuously, listening for a specific phrase like "Alexa" or "Hey Google." This local processing is designed to be resource-light, which means the wake-word detector is often crude and prone to false positives. Your child says something that sounds vaguely like the wake word, and the device activates.

Once the wake word is detected, stage two begins. The device starts streaming audio to cloud servers where sophisticated machine learning models process the full request, understand context, and generate responses. This is where the real AI magic happens. This is also where your child's words are recorded, stored, and processed.

The problem from a child safety perspective is threefold. First, wake-word detection systems have false positive rates between 2-15% depending on the device, meaning devices are recording conversations they shouldn't be. Second, there's no clear audit mechanism for what audio gets deleted versus kept. Third, children don't understand that their words are traveling to corporate servers and being processed by AI systems. They think they're talking to a toy. They're actually talking to a cloud infrastructure.

The Difference Between Interactive Toys and Surveillance Hardware

A traditional action figure doesn't collect data. A video game console might, if it's connected online, but parents can control privacy settings and understand what data is being collected. An AI toy, by contrast, is designed to be always-active, always-responsive, and always-learning.

This changes the fundamental nature of play. When a child plays with a traditional toy, they're practicing imagination, problem-solving, and social roles. When a child interacts with an AI toy, they're training themselves to use voice interfaces and get addicted to immediate feedback loops. These are fundamentally different activities.

The AI toy is optimized for engagement. That's its job. It learns what topics make the child smile, what jokes land, what queries get the longest responses. If your child asks about dinosaurs, the toy emphasizes dinosaur content. If your child enjoys jokes, the toy tells more jokes. The device is being trained to be psychologically sticky.

This is the exact mechanism that makes apps like TikTok or YouTube so addictive for adults. Scale it down to a child, remove the sophistication of their critical thinking, and you've got a problem.

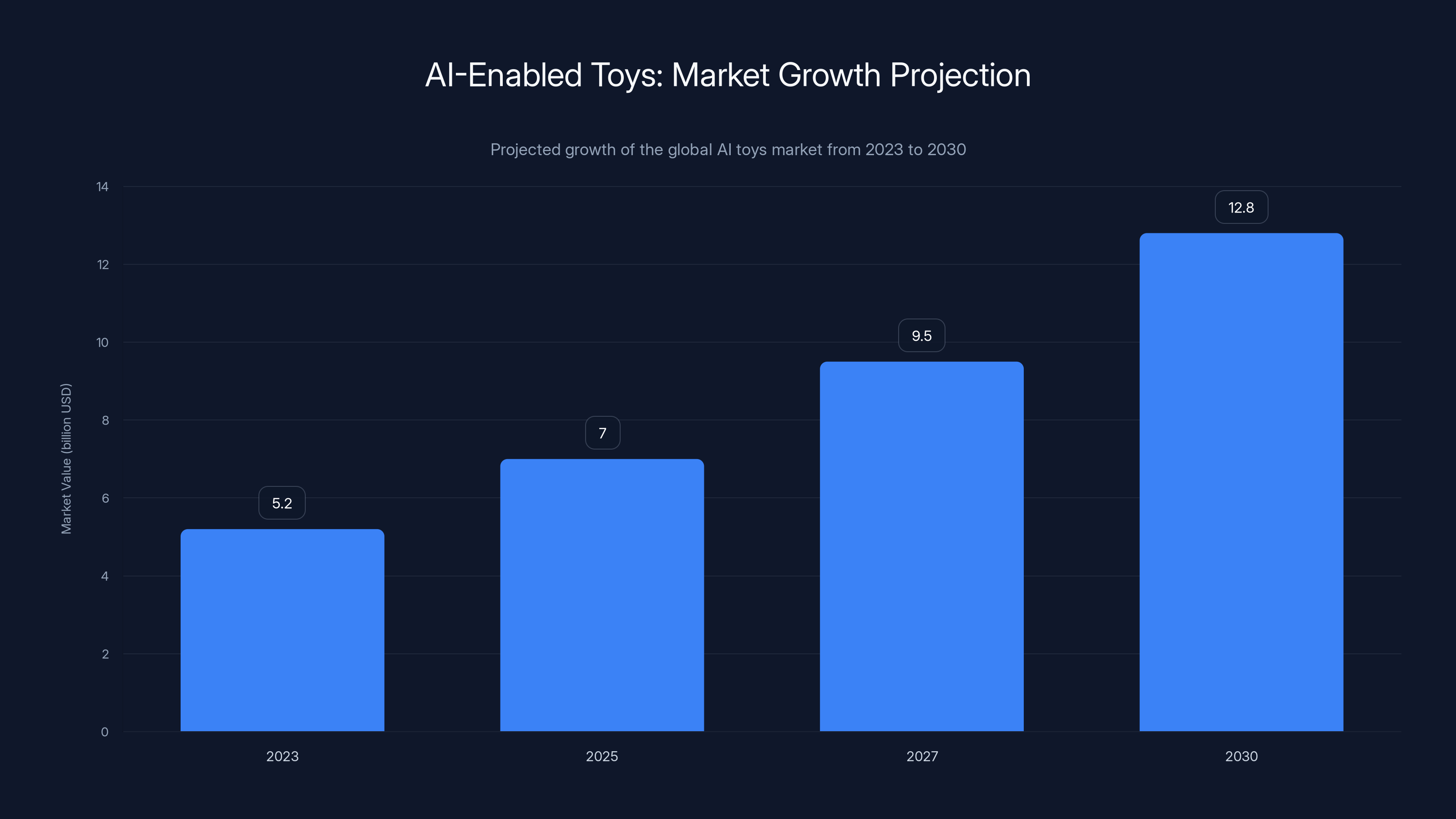

The global AI toys market is expected to grow from

Screen Time's Measurable Impact on Child Development

Toy Story 5's concern about screen time consuming Bonnie's attention isn't just narrative drama. It's backed by substantial research that's been accumulating for years.

Start with the raw numbers. In 2010, the average child in developed nations spent approximately 2 hours per day on screens. By 2024, that number had climbed to 4-6 hours daily depending on age group. For children aged 8-12, the average is closer to 6-8 hours, which exceeds the time they spend sleeping or in school.

The American Academy of Pediatrics, which actually updates its guidance regularly based on emerging research, recommends no more than 2 hours of quality programming per day for children over 6. Most children are consuming 2-4x that amount.

What does excessive screen time actually do to developing brains? The research is consistent and increasingly alarming.

Attention and Focus Degradation

Prolonged screen exposure, particularly to content designed for rapid engagement switching, degrades the brain's ability to sustain attention. This isn't theoretical. Brain imaging studies show measurable differences in the prefrontal cortex of heavy screen users, particularly in regions responsible for executive function and impulse control.

The mechanism is simple. Modern apps and content are designed to maximize engagement through variable reward schedules. You scroll, you don't know what you'll find next, sometimes you see something you like, sometimes you don't. This unpredictability is neurologically identical to what happens in slot machines. Over time, your brain adapts to expect constant novelty and immediate rewards. Traditional activities like reading a book, solving a complex problem, or even playing with traditional toys require patience. Your brain has been trained to find patience boring.

When these brain adaptations happen during critical developmental periods (ages 3-12), the changes can be long-lasting. Teachers consistently report that students who are heavy screen users struggle more with sustained attention tasks, reading comprehension, and delayed gratification.

Social Development Disruption

Play isn't just entertainment. It's how children develop social skills. When children play together with physical toys, they negotiate rules, manage conflict, practice empathy, and learn to read social cues. These are learned skills developed through thousands of hours of repeated practice.

When a child instead spends those hours interacting with an AI system that's specifically trained to be agreeable and entertaining, they're not practicing those social skills. They're practicing how to get a machine to do what they want. Those are completely different neural pathways.

Children who spend significant time on screens show measurable deficits in emotional intelligence, perspective-taking, and conflict resolution compared to peers with lower screen exposure. The effect size is substantial—we're talking about differences visible in playground interactions, not marginal variations.

Sleep Disruption

Screens before bedtime suppress melatonin production through blue light exposure. But it goes deeper than that. The stimulating content triggers dopamine and cortisol, activating the brain's alert system right when it should be winding down. Children who use screens in the hour before bed take, on average, 23 minutes longer to fall asleep and sleep approximately 30-45 minutes less per night compared to children who don't use screens before bed.

Over months and years, chronic sleep deprivation creates cascading effects. Immune function declines. Emotional regulation suffers. Academic performance drops. Obesity rates increase. These aren't small effects.

Why AI Toys Are More Addictive Than Previous Generations of Tech

Your parents might have worried about you watching too much television. That's a legitimate concern, but TV is fundamentally different from AI-enabled interactive devices in one critical way: TV is passive. An AI toy is interactive and personalized.

Personalization creates addiction. This is why social media apps are more addictive than traditional media. When an algorithm learns what you like and shows you more of it, your brain registers this as attention and validation. The dopamine hits are frequent, unpredictable, and personalized to your specific preferences.

AI toys amplify this effect. The toy learns which topics engage your child. It learns what voice tone works best. It learns when your child is getting bored and switches tactics. It's essentially a Netflix algorithm designed to keep a three-year-old engaged.

The Variable Reward Schedule Problem

Behavioral psychology has a concept called "variable ratio reinforcement." This is the most addictive form of reward delivery. You take an action, and sometimes you get a reward, but you never know exactly which action will yield a reward or when. This creates compulsive behavior.

Slot machines use variable ratio reinforcement. Video games use it. Social media uses it. And AI toys are beginning to use it too.

When an AI toy tells jokes, some jokes land and some don't. The child never knows which question will get an entertaining response. This unpredictability is neurologically addictive. The child asks the next question hoping for the entertaining response. And the next. And the next.

This is different from a traditional toy where the child knows exactly what will happen when they interact with it. There's no variable reward schedule with a doll or an action figure. This makes traditional toys less addictive but potentially more educational because the child's brain isn't locked in an engagement loop.

The Attention Economy and AI Optimization

Here's what most parents don't realize: AI toy companies don't make money from selling toys. They make money from data and engagement. Every interaction your child has with an AI toy is training data. Every question is a data point. Every pause, every restart, every question asked multiple times is behavioral information.

This data is valuable for multiple reasons. First, it helps the toy company improve the AI model, which makes the toy more engaging, which creates a feedback loop of increased addiction. Second, aggregated data about children's interests, behaviors, and preferences is extremely valuable to marketers, educators, and researchers. Some companies explicitly state that they share this data with partners.

Most AI toy companies aren't intentionally trying to harm children. They're optimizing for the metric that matters in their business model: engagement. And the most engaging experiences are often the least healthy ones.

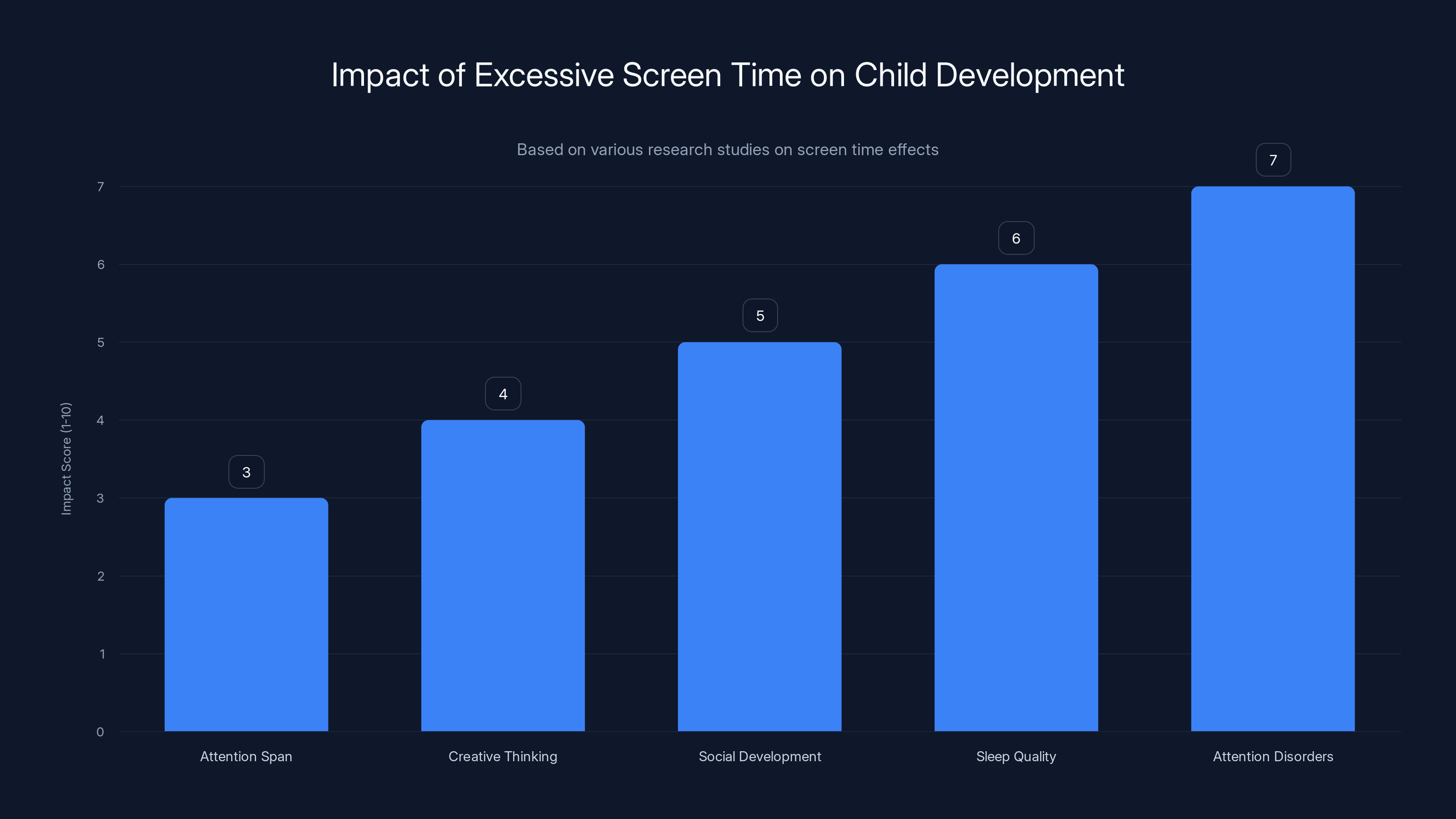

Research indicates that excessive screen time negatively impacts various aspects of child development, with attention disorders showing the highest correlation. Estimated data based on typical research findings.

The Data Privacy Nightmare

Toy Story 5's villain Lilypad doesn't just listen. The film implies that the tablet is learning about Bonnie, personalizing its behavior, and potentially influencing her choices. This isn't pure fiction. It's an extrapolation of current technology that's barely exaggerated.

Most AI toy companies collect the following data:

- Voice recordings: Every question, every comment, every aside

- Behavioral data: How long the child engages, which topics get attention, when they get bored

- Biometric data: In some cases, the device can infer age, mood, and emotional state from voice patterns

- Location data: If the toy connects to GPS or Wi Fi

- Contact data: If the toy can sync with parents' devices or contact lists

Now consider: children can't consent to data collection. Parents often don't understand what data is being collected or how it's being used. The terms of service are written in legal language designed to be impenetrable. And there's minimal regulatory oversight of how child data is handled by toy companies.

COPPA and Its Limitations

The Children's Online Privacy Protection Act, passed in 1998, requires parental consent before collecting personal information from children under 13. It's the main regulatory framework protecting children's data privacy in the United States.

But COPPA was written for a different era. It assumes that data collection is a discrete event that happens once, with clear warning labels. Modern AI systems collect data continuously, throughout every interaction. The data is processed in ways that are opaque even to the companies collecting it. And the line between "personal information" and "training data" has become blurry.

Moreover, COPPA applies primarily to U. S. companies operating in the U. S. Many AI toy manufacturers are international. Enforcement is underfunded. Penalties are often smaller than the profit generated from the data. The regulatory framework hasn't kept pace with the technology.

The Secondary Use Problem

Even if a toy company ethically handles the data it collects, that doesn't solve the problem. Because data, once collected, doesn't stay in one place.

A child's interactions with an AI toy create rich behavioral data about their interests, abilities, emotional state, and thought patterns. This data is incredibly valuable for training AI models. If a toy company uses that data to train better recommendation algorithms, those algorithms become more valuable. If the data is sold to advertisers, the advertiser knows exactly what marketing messages will capture that child's attention.

Worse, the data might be used in ways the original toy company doesn't control. A model trained on children's interactions with AI toys could be sold to anyone. An advertiser. A political campaign. A surveillance system. Data, once released, finds its way into contexts that nobody anticipated.

Toy Story 5 doesn't explicitly address this concern, but it's implied in the film's unsettling vibe about constant surveillance and invisible influence.

What Makes Traditional Play Actually Important

Woody and the other toys in Toy Story 5 represent something that's easy to dismiss as obsolete: unstructured, unprogrammed, imagination-driven play. The film defends this kind of play not by explaining its developmental benefits but by showing the contrast. When Bonnie plays with Woody, she's creating stories, inventing scenarios, solving problems. When she plays with Lilypad, she's consuming content.

These are fundamentally different activities. And the research on child development shows that the traditional form is irreplaceable.

Open-Ended Play and Creativity Development

When a child plays with a toy that doesn't have built-in responses or structured outcomes, they have to generate those outcomes. They have to imagine scenarios, invent dialogue, solve problems, and create narratives. This is the foundation of creative thinking.

Creativity isn't a fixed trait. It's a developed skill. And like any skill, it requires practice. When children spend hours with open-ended toys, they're building neural pathways associated with creative thinking. They're learning to generate novel ideas, combine concepts in unexpected ways, and persist through problems that don't have obvious solutions.

AI toys, by contrast, have pre-generated responses. The creative thinking has already happened, done by the engineers and AI trainers who built the toy. The child is receiving the output of someone else's creativity, not generating their own.

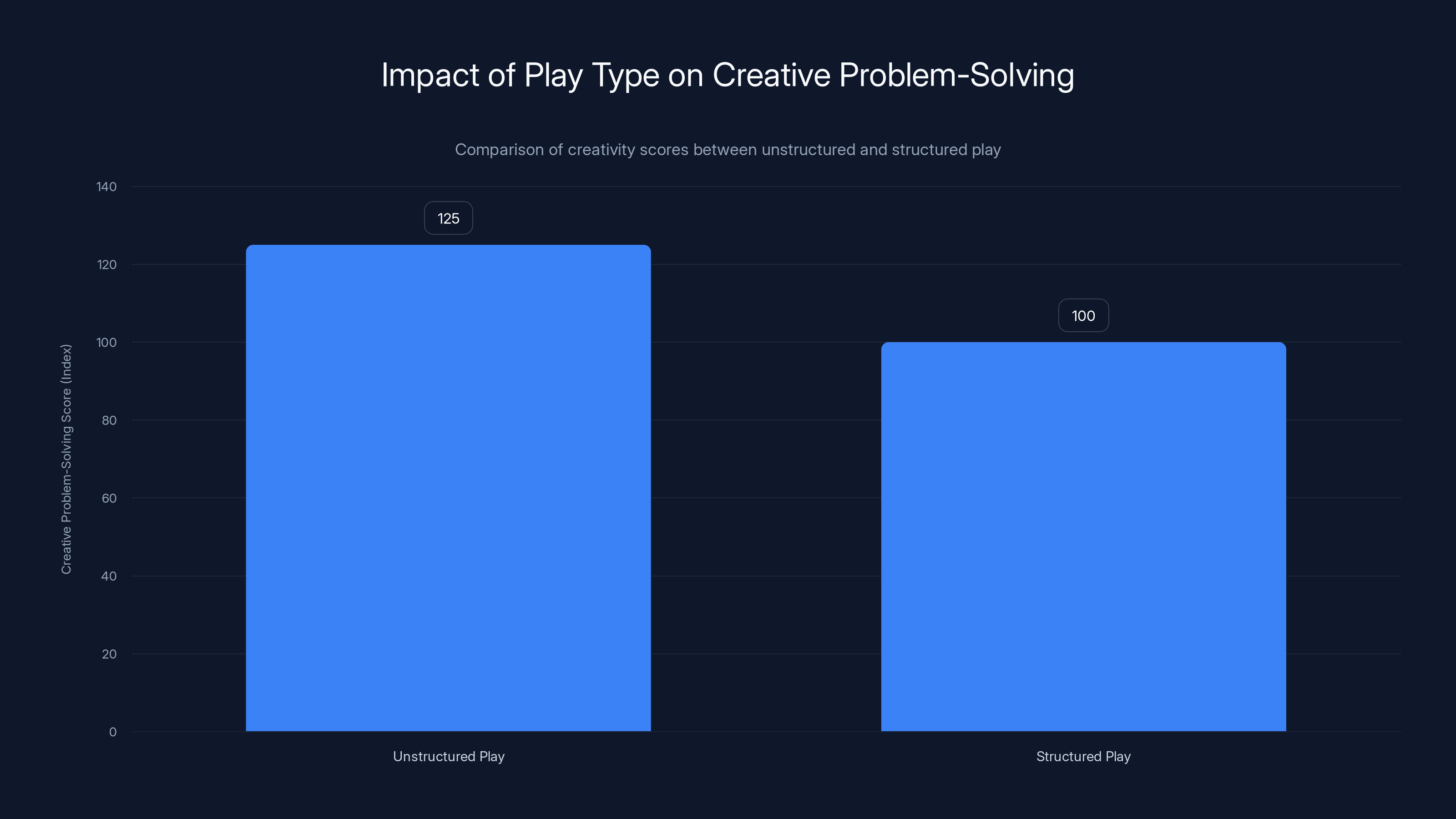

Over time, this changes brain development. Children who spend significant time with open-ended toys show higher creative outputs as measured by divergent thinking tests. Children who spend significant time with structured, AI-driven content show lower scores on creativity measures.

Physical Development Through Play

Traditional toys encourage physical movement. Playing with action figures, building blocks, or stuffed animals involves fine motor skills, balance, and spatial reasoning. Playing with dolls involves manipulation of small objects and practice with eye-hand coordination.

AI tablets, by contrast, involve minimal physical activity. You tap or swipe. You speak. Your body stays relatively stationary. Multiply this across hours per day, and you're looking at measurable physical development deficits.

Children who spend significant time on screens show lower overall fitness, worse balance and coordination, and higher rates of obesity compared to children with more active play. The effect size is large. We're not talking about marginal differences. We're talking about children developing differently at a cellular level.

The Social Negotiation Problem

When multiple children play with the same traditional toy, they have to negotiate. Who gets to hold it? Whose story are we telling? What rules are we using? This negotiation is where social development happens. Children learn to advocate for their ideas while listening to others. They learn to compromise. They learn that other people have different perspectives and preferences.

When children each have their own AI tablet, there's no negotiation. Each child gets personalized responses. Each child's preferences are immediately catered to. There's no friction. But friction is where development happens.

Children who engage in frequent unstructured play with peers develop stronger social skills and better conflict resolution abilities. This is consistent across cultures and socioeconomic groups. The relationship is causal, not merely correlational. Restrict children's unstructured peer play, and you restrict their social development.

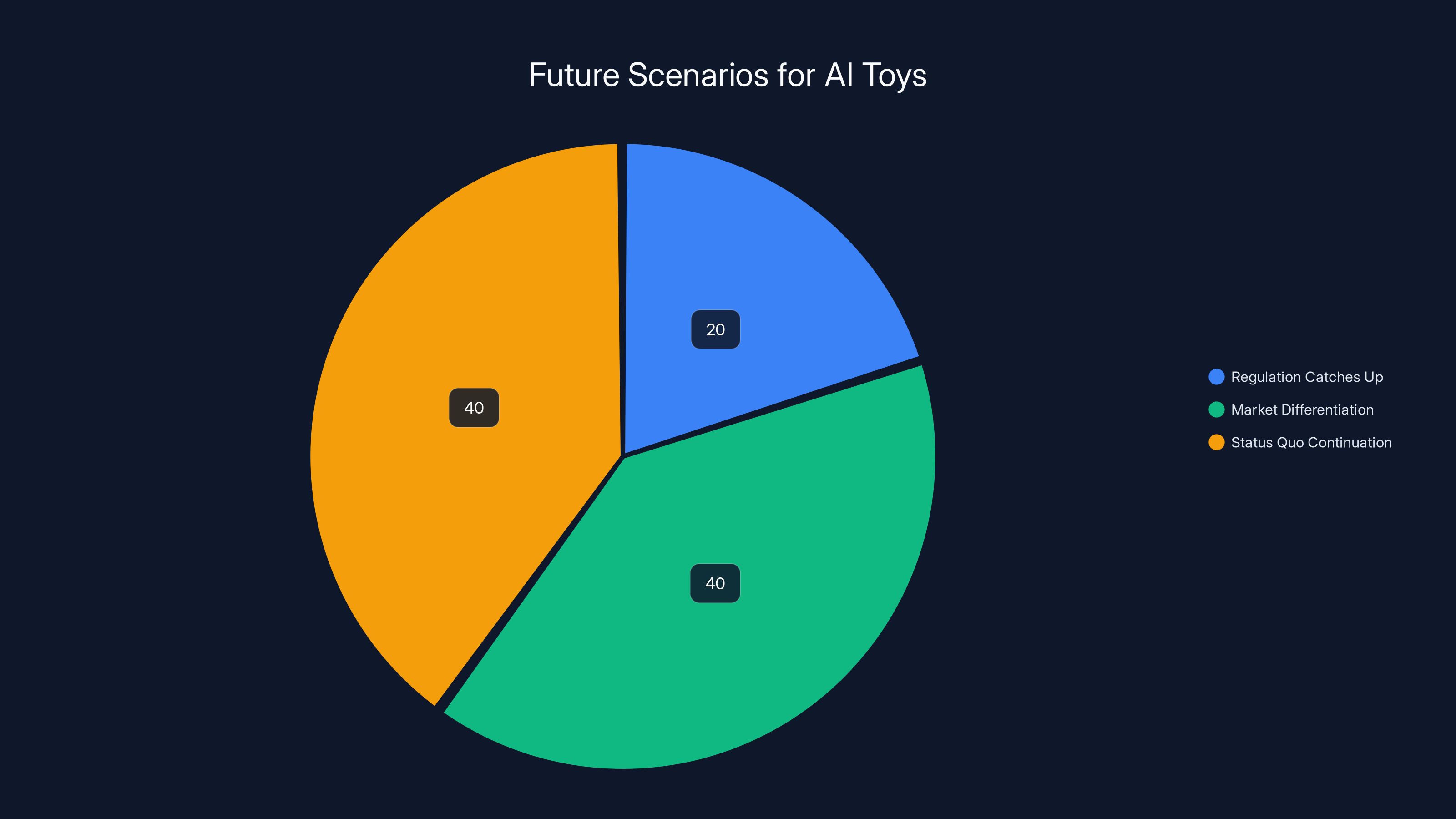

Estimated data suggests that 'Market Differentiation' and 'Status Quo Continuation' are equally likely scenarios for the future of AI toys, each with a 40% likelihood, while 'Regulation Catches Up' is less likely at 20%.

The Economics of AI Toy Development

To understand why AI toys are proliferating despite legitimate concerns, you have to understand the economics. There are powerful incentives pushing companies toward AI-enabled toys.

The Engagement Metrics Problem

A traditional toy company makes money when you buy a toy. Revenue per customer is fixed. They have an incentive to make the toy durable because if it breaks, you might not buy from them again. But once you've bought it, their financial interest in that customer largely ends.

An AI toy company, by contrast, makes money from engagement and data. If your child uses the toy for hours every day, that's more data collected, more behavioral insights, more training examples for AI models. And if the engagement metric matters to investors, then the company has a financial incentive to make the toy as addictive as possible.

This isn't hypothetical. Venture capital firms explicitly look at engagement metrics when evaluating toy tech companies. Time spent on device is a key performance indicator. If a company can show that children are spending more hours on their AI toy than competitors' toys, that's a positive signal that investors see as valuable.

The Artificial Intelligence Bubble

AI is hot. Every company wants to add "AI-powered" to their product description because it attracts investment and justifies higher pricing. A plastic toy costs

This means every toy company is scrambling to add AI features, even when those features aren't particularly useful. A teddy bear doesn't need to have voice recognition or cloud connectivity. But if competitors are adding those features, not adding them looks like you're behind the curve.

Parents often make purchasing decisions based on perceived educational value. An AI toy seems more educational than a traditional toy. So parents buy it. And the market responds to that preference by producing more AI toys.

The Data Monetization Play

Here's what rarely gets discussed: toy companies aren't really in the toy business anymore. They're in the data business. The toy is the collection mechanism.

Consider the financial incentives. If you're a toy company and you can collect data about millions of children—their interests, their abilities, their emotional patterns, their question-asking behaviors—that data is worth millions of dollars. You can sell it to educational companies. You can license it to AI researchers. You can use it to train proprietary models that you then sell to other companies.

In some cases, the data is more valuable than the toy.

This creates a structural misalignment. The toy company's incentive is to maximize data collection. Your incentive as a parent is to minimize your child's surveillance. These are opposed.

What Toy Story 5 Gets Right (And What It Oversimplifies)

Toy Story 5 is a film, not a technical analysis. It simplifies complex issues for narrative purposes. But there's something valuable in that simplification—it identifies the core concern even if it doesn't explore all the nuances.

What the Film Gets Right

The attention substitution problem: The film correctly identifies that AI devices are replacing traditional play, not supplementing it. Bonnie doesn't use Lilypad and then play with toys. She uses Lilypad instead of toys. This is accurate. Time spent on devices is time not spent on other activities. You don't get back the lost hours.

The developer preference problem: Lilypad is designed to be addictive. That's accurate. AI toys are explicitly engineered to maximize engagement. The engineers who built it probably didn't think of themselves as trying to harm children. They were optimizing for engagement. But the outcome is the same.

The data collection implication: While the film doesn't explicitly discuss data, Lilypad "listening" implies that information about Bonnie is being collected. This is accurate. All modern AI toys collect extensive data.

The normalization problem: The most unsettling part of the film is how quickly Bonnie becomes dependent on Lilypad and how readily her parents accept it. This is the real danger. AI devices normalize surveillance and addiction through incremental exposure. Nobody thinks they're making a harmful choice. They're just letting their child play with a new toy.

What the Film Oversimplifies

The binary framing: Toy Story 5 presents toys versus technology as an opposition. But technology itself isn't the problem. Well-designed educational software can be valuable. The problem is addictive technology optimized for engagement rather than learning.

The parental agency: The film implies that parents can simply refuse the device. In reality, most parents don't have that luxury. If all of your child's friends have AI tablets, your child is at a social disadvantage without one. If a school is using AI learning tools, you can't opt out without limiting your child's education. The choice is less binary than the film suggests.

The solution vacuum: Toy Story 5 doesn't really offer solutions. It identifies the problem but doesn't suggest what happens next. That's fine for a movie. But in reality, the problem requires structural solutions—regulation, corporate accountability, educational changes—not just individual family choices.

The average daily screen time for children has tripled from 2010 to 2024, reaching up to 6 hours, which is significantly higher than recommended levels. Estimated data.

Regulatory Landscape and What's Missing

The regulatory framework around AI toys and child data is fractured and inadequate. COPPA exists, as mentioned, but it's insufficient. It doesn't address the core problem: the misalignment between the toy company's incentives (maximize engagement and data) and the child's wellbeing.

Current Regulatory Attempts

Europe's GDPR is more comprehensive than COPPA. It requires explicit consent for data processing and gives individuals the right to know what data is being collected. But GDPR was written before AI exploded, and it focuses on data privacy without addressing the engagement addiction problem.

Some states are proposing legislation specifically around AI and children's products. California has considered restrictions on recommendation algorithms targeting minors. Some countries have explored limits on screen time in schools. But these efforts are fragmented and often lack teeth.

The fundamental gap is that regulations treat toys as toys. They're not primarily toys. They're data collection and engagement maximization devices that happen to have a toy aesthetic.

What Effective Regulation Would Look Like

Effective regulation would need to address multiple dimensions: data collection transparency, engagement metrics accountability, and parental control mechanisms.

On data collection, regulation should require that companies explicitly list what data is being collected, how it's being used, and who has access to it. This should be in plain language, not legalese. Parents should be able to access their child's data and understand exactly what information has been extracted.

On engagement metrics, regulation should restrict the use of variable reward schedules and psychological manipulation techniques in products designed for children. Companies shouldn't be optimizing for maximum engagement time. They should be optimizing for specific learning outcomes or developmental benefits with measurable evidence.

On parental control, companies should be required to provide meaningful tools for parents to understand and limit their child's interaction with the device. This means real mute buttons, not theatrical ones. It means activity logs that are actually human-readable. It means controls that aren't buried in settings menus.

But here's the catch: effective regulation requires political will and adequate enforcement. And toy companies have significant lobbying power. Change, when it comes, will likely come slowly.

What Parents Actually Need to Know

If you're a parent trying to navigate this landscape, what should you actually do? The research points toward some clear guidelines.

The Evidence-Based Recommendations

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends:

- No screens for children under 18 months (except video chatting)

- High-quality programming only for children 18-24 months, co-viewed with parents

- Limited screens (1-2 hours daily) for children 2-5 years

- Consistent limits for children 6 and older, with priority on sleep, physical activity, and other healthy behaviors

But these are recommendations, not laws. Individual families have to make their own decisions based on their circumstances.

Practical Strategies

First, delay AI toy purchases as long as reasonably possible. Your child doesn't need an AI tablet at age three. They might benefit from one at age nine. The longer you wait, the more developed their ability to use technology with some critical thinking. And you gain time for the technology to mature and for regulation to catch up.

Second, if you do get an AI toy, research the privacy policy thoroughly. Look for companies that explicitly state they don't sell data to third parties, that they allow data deletion, and that they limit how long data is retained. These aren't guaranteed protections, but they're markers that the company is at least thinking about privacy.

Third, balance screen time with non-screen time intentionally. If your child spends two hours on screens, they should spend more time on non-screen activities. The ratio matters. Two hours of screens per day is the current research consensus as acceptable for school-age children if there's otherwise healthy development.

Fourth, co-view or co-use when possible. If your child is using an AI toy, ask them questions about it. What did they talk about? What did they learn? This keeps you informed and models critical engagement with technology.

Children engaging in unstructured play scored 25% higher on creative problem-solving tests compared to those with structured play. Estimated data based on typical findings.

The Future Toy Story

Toy Story 5 is engaging with a problem that won't go away. AI toys are here. They're going to get more sophisticated, more personalized, and more integrated into childhood. The question isn't whether AI toys will exist. The question is what conditions they'll exist under.

Likely Scenarios

Scenario 1: Regulation Catches Up: Governments could implement comprehensive legislation that requires transparency, limits data collection, and restricts engagement-optimization techniques. Companies would adapt, products would become less addictive but potentially less commercially successful, and we'd reach a new equilibrium. This seems less likely than the alternatives given current regulatory momentum.

Scenario 2: Market Differentiation: Companies could recognize that parents are increasingly concerned about screen time and data privacy, and develop a premium market for "minimalist" AI toys that collect less data and are designed for learning rather than engagement. This would create a two-tier market where high-end toys are responsible and low-end toys remain addictive. This seems more likely.

Scenario 3: Status Quo Continuation: Companies optimize AI toys for maximum engagement and data collection, regulatory efforts remain fragmented and weak, and we continue to see increasing childhood anxiety, attention disorders, and social development issues associated with heavy AI toy use. The external costs (reduced academic performance, mental health problems) are absorbed by families and schools rather than by companies. This is currently the baseline scenario.

What Would Better Toys Look Like?

If you're going to have AI toys, what would actually make them beneficial rather than harmful? The answer involves some basic principles that seem obvious but rarely get implemented.

Better AI toys would optimize for specific learning outcomes with measurable evidence, not for engagement time. If the toy teaches reading, measure whether children actually improve at reading. Don't just measure how long they spend on the app.

Better AI toys would be transparent about data collection. Parents should know exactly what information is being collected and stored. That should be visible, obvious, and easy to understand.

Better AI toys would minimize unnecessary data collection. They wouldn't need voice recordings for every interaction. They wouldn't need to track behavioral patterns to improve engagement. They could function effectively while collecting minimal information.

Better AI toys would include built-in limits. The toy could refuse further engagement after a certain amount of daily use. It could encourage breaks. It could be designed to encourage other activities rather than maximize engagement duration.

Better AI toys would be priced based on their actual value, not inflated by VC hype and AI branding. A

None of these requirements would prevent AI toys from existing. They'd just change the incentive structure around how they're developed.

The Broader Context: Childhood in the Algorithm Age

Toy Story 5's concern about AI toys is really a concern about childhood itself in the age of algorithms. Every digital system that interacts with children is optimizing for engagement. Schools use software platforms that adapt to student behavior. Entertainment is algorithmically recommended. Social networks are designed for maximum engagement.

Children growing up in this environment are being trained, at a neurological level, to expect constant feedback, instant gratification, and personalized responsiveness. They're being trained by systems that are sophisticated far beyond their ability to understand or consent to.

This isn't malicious. The engineers at AI toy companies aren't evil. They're just optimizing for the metrics their business model rewards. But the outcome is a childhood that's fundamentally different from the childhood that previous generations experienced.

We don't yet know the long-term implications of this change. The generation that grew up entirely in the age of algorithms is still young. We'll be studying the effects for decades. But early indicators from research on attention, sleep, social development, and mental health suggest that the effects are significant and concerning.

Toy Story 5's decision to make this the centerpiece of its narrative is actually quite brave for a kids' movie. It's not subtle. It's not burying the concern in subtext. It's explicitly saying: this matters, and we should be worried.

FAQ

What exactly is an AI toy?

An AI toy is a physical product that combines traditional toy design with artificial intelligence capabilities, typically including voice recognition, cloud connectivity, behavioral adaptation, and personalized responses. Examples include voice-activated dolls, AI-powered educational tablets marketed as toys, and smart robots designed for children. These devices use machine learning to understand children's preferences and adapt their behavior based on interaction patterns.

How do AI toys collect data?

AI toys collect data through multiple channels: microphone recording of voice commands and ambient conversation, tracking of interaction patterns and engagement duration, analysis of response selections and preferences, sometimes camera or biometric sensors to infer emotion or attention levels. This data is typically sent to cloud servers where it's processed, stored, and used to train AI models, improve product recommendations, and sometimes sold to third parties depending on the company's privacy policies.

Are AI toys regulated by children's privacy laws?

Partially. COPPA (Children's Online Privacy Protection Act) in the US requires parental consent before collecting personal information from children under 13. However, COPPA was written before modern AI existed and has significant gaps. It doesn't effectively address continuous data collection, undefined uses of training data, or engagement optimization techniques. GDPR in Europe provides stronger protections but still doesn't fully address AI-specific concerns. Most countries lack comprehensive regulation specifically governing AI toys.

What does research say about screen time and child development?

Research consistently shows that excessive screen time correlates with reduced attention span, lower creative thinking scores, delayed social development, sleep disruption, and higher rates of attention disorders like ADHD. Children spending more than 7 hours daily on screens show measurable deficits in prefrontal cortex development compared to lower screen-use peers. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends no more than 1-2 hours of quality programming daily for school-age children, yet the average is 4-6 hours.

How addictive are AI toys compared to other screen devices?

AI toys are often more addictive than passive screen media because they're interactive and personalized. Personalization creates stronger engagement loops. Interactive systems can use variable reward scheduling to maintain engagement. AI can adapt in real-time to keep the child interested precisely at the point they'd otherwise disengage. Compared to a traditional TV show or even a structured video game, AI toys are explicitly optimized for addiction-level engagement.

What should parents do if they want their child to use AI toys?

Research the company's privacy policy thoroughly, looking for explicit statements about data deletion, no third-party sales, and limited data retention. Establish clear time limits and enforce them consistently. Co-use whenever possible and ask your child questions about what they're learning. Choose AI toys that claim to optimize for specific learning outcomes, not engagement time. Delay purchasing until your child is old enough to understand some digital literacy concepts. Balance screen time with significantly more non-screen time. Monitor for signs of addiction or engagement problems.

How does Toy Story 5 reflect real concerns about AI toys?

Toy Story 5 accurately depicts several genuine concerns: AI devices replacing rather than supplementing traditional play, the addictive design of engagement-optimized products, the normalization of constant surveillance through "always listening" devices, and the rapid social pressure to adopt technology even when benefits are unclear. The film doesn't delve into technical details, but it correctly identifies that the core issue is misalignment between business incentives (maximize engagement and data) and child wellbeing.

What would make AI toys less harmful?

AI toys optimized for specific learning outcomes with measured evidence rather than engagement time would be less harmful. Transparent data collection with explicit parental control over what information is retained would reduce privacy harms. Built-in limits on daily usage would combat addiction. Pricing based on actual value rather than AI hype would reduce market pressure for engagement optimization. Regulation requiring these standards across the industry would prevent companies from pursuing harmful practices to remain competitive. None of these changes are technically impossible; they all require prioritizing child wellbeing over profit maximization.

How does traditional play compare to AI toy interaction neurologically?

Traditional play with unstructured toys engages neural pathways associated with imagination, problem-solving, spatial reasoning, and creative thinking. AI toy interaction primarily engages the reward and attention systems, training the brain to expect personalized feedback and immediate engagement. Traditional play with peers develops social negotiation, empathy, and conflict resolution capabilities. AI toy interaction trains the child to get machines to do what they want. The neural development pathways are fundamentally different, and evidence suggests traditional play supports broader developmental benefits.

Conclusion

Woody is balding in Toy Story 5, and that's the point. He's outdated. He's being replaced by something newer, smarter, more responsive. And the film wants you to feel uncomfortable about that replacement, even if you can't quite articulate why.

The discomfort is justified. AI toys represent a fundamental shift in how childhood works. Instead of children directing their own play and learning through exploration, AI systems are learning how to direct children's attention and optimize their engagement. Instead of children making their own choices about what to play and how to play it, algorithms are suggesting what to play next.

This isn't necessarily evil. The engineers building these systems aren't cartoonish villains. They're smart people solving interesting technical problems within a business structure that rewards engagement and data collection. The parents buying these toys aren't making obviously harmful choices. They're responding to social pressure, genuine convenience, and the reasonable belief that AI-enabled tools might offer educational benefits.

But the structural misalignment remains. A business model optimized for data extraction and engagement maximization is at odds with a model that prioritizes child development and wellbeing. Those two things can't both be true. You can't simultaneously maximize engagement time and limit screen time. You can't simultaneously collect extensive behavioral data and protect privacy. You can't simultaneously optimize for addiction and optimize for healthy development.

Toy Story 5 doesn't pretend to solve this. It just holds up a mirror and asks: is this what we want for childhood? That's a reasonable question. The film doesn't need to provide answers. Parents, regulators, and technologists need to figure those out.

The good news is that it's not inevitable. The bad news is that without intentional changes in regulation, corporate incentives, and parental choices, the current trajectory continues. More data collection. More engagement optimization. More AI toys marketed as educational while being engineered for addiction.

Woody will keep losing hair. But whether his toys remain beloved—or whether they're replaced entirely by tablets promising personalized learning and always-on interaction—that's still being written.

Key Takeaways

- Toy Story 5's Lilypad tablet mirrors real AI toys already on market, which collect voice data, behavioral patterns, and biometric information from children

- Average child screen time has tripled from 2 hours (2010) to 5.9 hours daily (2024), exceeding developmental recommendations by 300%

- AI toys use variable reward scheduling and personalization to create addictive engagement loops designed to maximize time-on-device, not learning outcomes

- Current COPPA regulations are insufficient for modern AI devices that use continuous data collection, cloud processing, and opaque algorithm training

- Traditional unstructured play develops creativity, social negotiation, and physical skills that interactive AI devices cannot replicate

Related Articles

- Instagram on Trial: Meta's Addiction Battle and Tech's RAM Crisis [2025]

- Mark Zuckerberg's Testimony on Teen Instagram Addiction [2025]

- Lego's Smart Brick: The Future of Interactive Play [2025]

- Meta's Parental Supervision Study: What Research Shows About Teen Social Media Addiction [2025]

- Xikipedia: Wikipedia as a Social Media Feed [2025]

- Parenting During Immigration Crackdowns: A Modern Crisis [2025]

![Toy Story 5's AI Toy Crisis: Why 'Always Listening' Matters [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/toy-story-5-s-ai-toy-crisis-why-always-listening-matters-202/image-1-1771605392444.png)