Mark Zuckerberg's Testimony and Instagram's Addiction Problem

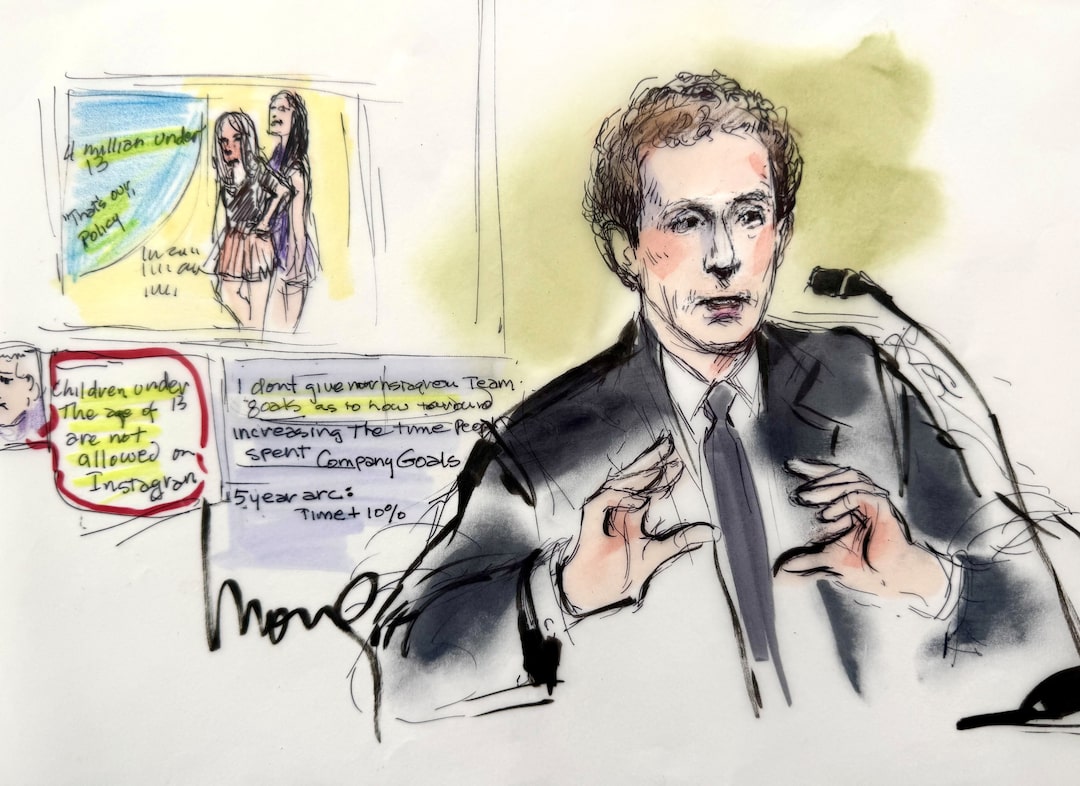

When Mark Zuckerberg stepped into the courtroom recently, the stakes couldn't have been higher. The Meta CEO was there to defend one of the most consequential decisions his company ever made: the acquisition of Instagram. But the trial wasn't really about the acquisition itself. It was about whether Instagram was intentionally designed to become addictive, and whether Instagram exploited teenagers in the process.

Zuckerberg's defense was straightforward. He claimed that when Meta bought Instagram in 2012, the company only wanted to make it "useful." Not addictive. Not engagement-obsessed. Just useful. The testimony painted a picture of a company focused on utility, on solving real problems, on connecting people meaningfully.

But here's where it gets complicated. Everyone in tech knows that useful products and addictive products aren't mutually exclusive. In fact, the most successful products are often both. They're so useful that people can't stop using them. They're so engaging that notifications become reflexive. They're so seamlessly integrated into daily life that the line between utility and addiction blurs almost entirely.

The trial represents something much bigger than a single product acquisition. It's about whether social media companies should face legal consequences for designing platforms that hijack human psychology. It's about whether there's a meaningful difference between building something useful and building something that keeps you scrolling at 2 AM when you should be sleeping.

The implications extend far beyond Meta. Every social media company, every tech startup, every product team that's ever optimized for engagement is essentially on trial here. If courts determine that Instagram was deliberately designed to be addictive, it opens a legal pathway for regulating how technology companies can design their products.

The Legal Framework: Why This Trial Matters

The trial isn't just about Instagram. It's about establishing legal precedent around social media company responsibility. Several states have filed suit against Meta, arguing that the company knowingly designed Instagram to exploit vulnerable teenagers. The argument goes like this: Meta knew about the psychological mechanisms that drive addiction. They implemented features specifically to maximize engagement. They prioritized profits over user wellbeing.

What makes this trial historic is that it forces companies to articulate, in court, the actual intent behind their design decisions. When you're under oath, you can't just say "we followed best practices." You have to explain why you chose infinite scroll over finite sessions. Why you implemented streaks in Stories. Why you made the "like" counter so prominently visible. Why you engineered FOMO so precisely.

Zuckerberg's testimony that Instagram was meant to be useful, not addictive, creates an interesting logical problem. If a product is useful, people will use it. If a company then implements features to maximize how much people use it, at what point does utility become exploitation?

The legal system hasn't really had to answer this question before. Previous tech regulation has focused on privacy (GDPR), data usage (CCPA), or monopolistic behavior (antitrust cases). But this trial is different. It's asking whether the design of a product can be a form of harm.

The precedent here could reshape how companies design products across industries. If Instagram can be sued for addictive design, what about streaming services with autoplay? What about mobile games with battle passes and daily missions? What about email clients with notification badges?

How Instagram Was Designed for Maximum Engagement

To understand the addiction question, you need to understand how Instagram actually works. The platform wasn't always algorithmic. When Instagram first launched, it was chronological. Posts appeared in the order they were posted. You saw what your friends shared, in sequence, and then you were done.

Then Instagram introduced the algorithmic feed. Instead of showing you what you follow, Instagram's algorithm shows you what Instagram thinks you want to see. This is where everything changed. Suddenly, the company had complete control over what appeared on your screen. They could optimize for engagement. They could test different content types. They could identify which posts kept people scrolling longest.

The algorithm isn't neutral. It's literally designed to maximize time spent. Every feature Instagram added after that point was engineered with engagement metrics in mind. Stories? They create urgency (the 24-hour disappearance). Streaks? They create social obligation (you don't want to break your streak with friends). Reels? They're designed to be the most addictive content format, pulling from short-form video research that goes back decades.

Likes and comments are dopamine hits. They're literally designed to feel rewarding. Instagram understood this because Meta employs thousands of behavioral scientists, psychologists, and engagement engineers. These aren't people hired to build tools. They're hired to maximize metrics. When you're explicitly optimizing for engagement, you're optimizing for addiction whether you frame it that way or not.

The company also uses notifications strategically. When someone comments on your post, you get a notification. This draws you back into the app. When the algorithm thinks you're disengaging, Instagram sends recommendations. These aren't helpful suggestions—they're engineered interventions designed to prevent you from leaving.

When you examine Instagram's design through this lens, it's hard to call it "useful" without acknowledging that utility is secondary to engagement optimization. The platform is useful for connecting with friends, sure. But the way it's designed makes it useful in ways that keep you coming back, not ways that let you leave satisfied.

The RAMaggedon Crisis: A Perfect Storm in Hardware

While Instagram was on trial, another crisis was unfolding in the semiconductor industry. The RAM shortage, affectionately called "RAMaggedon" by tech insiders, is worse than initially thought. And the implications are staggering.

DRAM (Dynamic Random Access Memory) prices have skyrocketed over the past eighteen months. A shortage that started with supply chain issues has evolved into a supply-demand imbalance that's cascading through every consumer electronics manufacturer. From gaming consoles to laptops to smartphones to smart TVs, everything that needs RAM is getting hit.

The problem started innocuously enough. During the pandemic, demand for electronics surged. Factories ramped up production. But then supply chain disruptions happened. Logistics backed up. Shipping costs soared. And by the time factories wanted to resume normal operations, demand had cooled. They were left with excess inventory and no way to move it quickly.

But that's only part of the story. The real issue is that manufacturing capacity for advanced memory chips is incredibly expensive. Only a handful of companies in the world can make cutting-edge DRAM: SK Hynix, Samsung, and Micron in the US. When demand is low, these companies don't invest in new fabrication plants (fabs). It costs billions and takes years. So when demand suddenly spikes again, there's no way to quickly increase supply.

We're seeing the effects everywhere. PC manufacturers are struggling to build laptops at competitive prices. Console makers are delaying next-generation hardware. Smartphone manufacturers are reducing features to manage cost. And smaller companies that can't absorb the price increases are simply exiting the market.

The mathematical reality is brutal. If DRAM costs double, and a laptop needs 16GB of RAM, that's an immediate hit to the manufacturing cost of every laptop in the world. Pass that cost to consumers, and demand drops. Reduce the specifications to cut costs, and your product becomes less competitive. You're stuck.

Why RAMaggedon Will Reshape Consumer Electronics

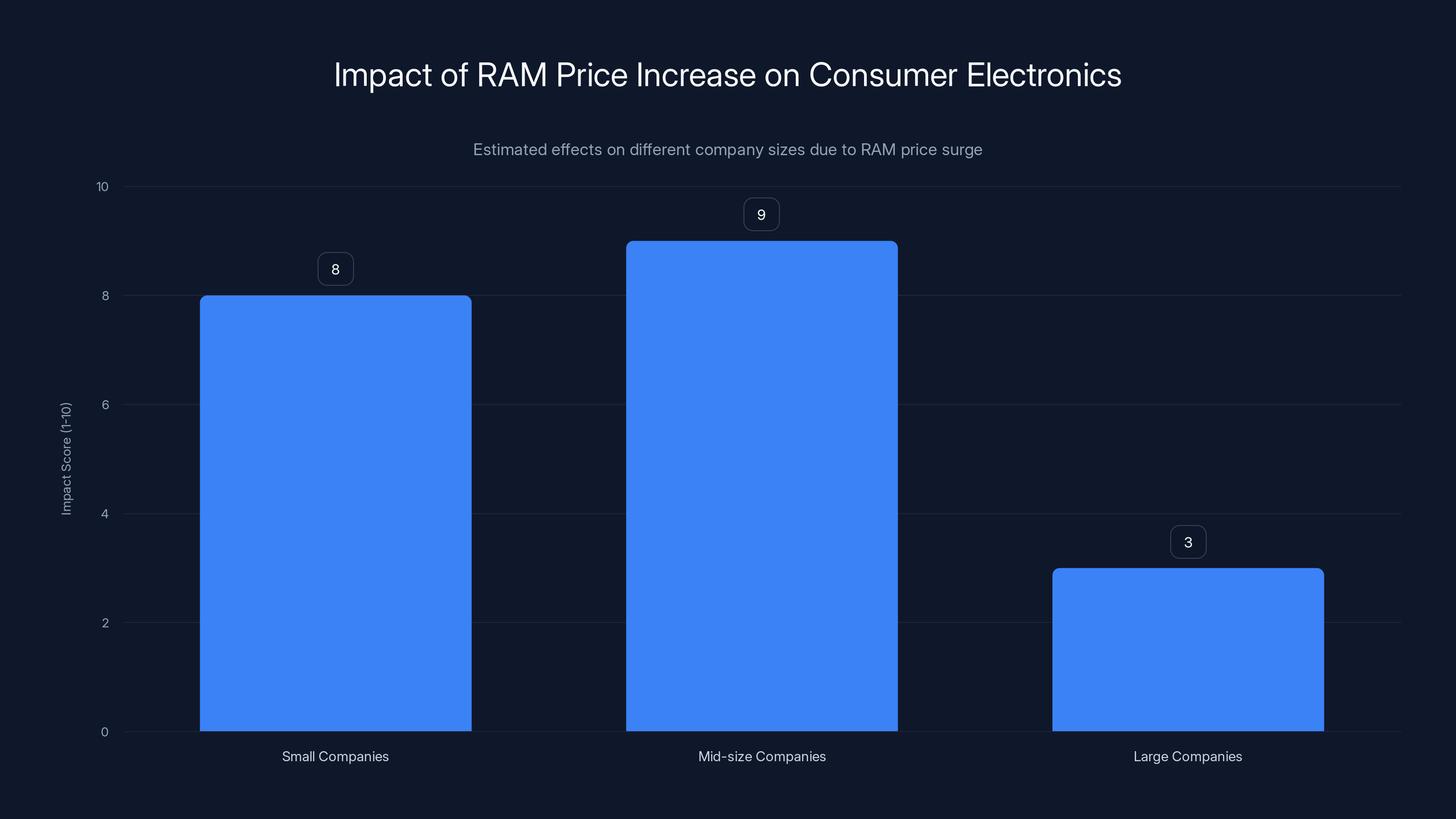

This shortage will have longer-term effects that most people don't realize. Small consumer electronics companies will go bankrupt. The industry is about to see consolidation. Companies that survive will be those with either massive cash reserves to weather the price increases or those that can shift production or innovate their way out.

Consider a mid-size company making smart home devices. They were planning to release a new product that requires more RAM than previous generations. They budgeted for DRAM at historical prices. But now those chips cost 40% more. They have three choices: absorb the loss, raise prices, or reduce the specifications.

Absorbing the loss isn't viable long-term. Raising prices prices you out of the market. Reducing specs makes you non-competitive. So they might just not release the product at all. And if they have other products in their pipeline with similar issues, the company might decide it's time to sell the brand to a larger competitor or shutter the business entirely.

Larger companies like Apple, Microsoft, and Samsung have the scale to manage this. They can temporarily accept lower margins. They can negotiate better deals with memory manufacturers because they buy in massive quantities. They can even vertically integrate, developing their own chips (which Apple, Microsoft, and Amazon are all doing).

But the mid-market gets destroyed in situations like this. And when the mid-market gets destroyed, innovation slows. The companies that take risks and try new things are the smaller, nimbler ones. When they disappear, you get a market dominated by safe, conservative incumbents.

Mid-size companies face the highest impact from RAM price increases, potentially leading to market exits or consolidation. Estimated data.

The Ripple Effect: Play Station 6 and Beyond

The rumor that Play Station 6 might be delayed is a perfect example of RAMaggedon's reach. The next-generation Play Station will need significant amounts of RAM—probably at least 24GB, possibly 32GB or more. That's going to cost significantly more than the RAM in Play Station 5.

Sony has to make a decision: launch at a higher price point, or delay the console until RAM costs come down. From a business perspective, delaying might be smarter. Console launches are huge marketing events. You only get one chance to make a first impression with a generation. If you launch at

But delaying also carries risk. Microsoft is presumably making the same calculations about Xbox. Nintendo might launch a new console. If Sony delays too long, competitors could get market share they wouldn't otherwise have. It's a game of chicken where the winner is whoever blinks last.

And it's not just consoles. PC manufacturers are dealing with the same math. A gaming PC that previously cost

How Meta's Smartwatch Fits Into the Picture

Amidst all this chaos, Meta is reportedly planning to launch a smartwatch later this year. It's a fascinating move given the regulatory environment and the hardware crisis.

Meta's smartwatch isn't just a watch. It's another sensor-rich device that collects data about users. It tracks health metrics, location, activity, interactions. It's another connection point between the user and Meta's data collection infrastructure. And it's another wearable device that depends on RAM to function.

The smartwatch also represents Meta's diversification strategy. The company has been hammered by i OS privacy changes that limited ad targeting. They've lost billions in ad revenue because they can no longer track users across the web as effectively. Developing hardware—smartwatches, Ray-Ban glasses, VR headsets—gives Meta a way to directly control the hardware-software ecosystem.

If you own a Meta smartwatch, Meta controls the operating system. They control the sensors. They control what data gets collected. They can't be cut off by Apple's privacy policies because they're not dependent on i OS integration.

But launching a smartwatch during RAMaggedon is risky. The bill of materials just got more expensive. The supply chain is more uncertain. And if the smartwatch doesn't succeed, Meta has sunk costs into manufacturing facilities and inventory that they can't quickly pivot away from.

Apple's March Event: M5 Pro and New Hardware

Apple is reportedly planning to announce new hardware on March 4th. The rumored announcements include a new Mac Book, the M5 Pro chip, and potentially the i Phone 17e. This event is significant in the context of both the Instagram trial and RAMaggedon.

Apple has traditionally been insulated from memory shortages because they develop their own chips. The M-series processors are designed and engineered by Apple, then manufactured by TSMC. Apple can negotiate with memory suppliers at scales that most companies can't match. So while other manufacturers are struggling with DRAM costs, Apple can absorb some of that increase and maintain margins.

The M5 Pro is particularly interesting because it suggests Apple's commitment to AI capabilities. The "Pro" designation typically means the chip is optimized for professional workloads—video editing, 3D rendering, machine learning. If Apple is releasing an M5 Pro, it's likely because they want to enable AI features on their devices that rival what's available on cloud platforms.

The i Phone 17e is curious. Apple typically names phones by their screen size (Max, Plus) or capabilities (Pro). The "e" designation is unusual. It could mean "economy" or "essential." If Apple is releasing an economy phone, it signals that they're responding to market pressure from higher prices. Maybe they're concerned that the i Phone 16 costs too much for average consumers.

But here's the interesting bit: an economy i Phone would be even more affected by RAMaggedon than a premium phone. To hit a lower price point, Apple would need to reduce RAM or storage. But specs are already tight on i Phones. You can't reduce much further without making the phone noticeably worse. So Apple might be caught between a rock and a hard place—they want to launch an economy phone, but hardware costs make it hard to profit at lower price points.

Google's Pixel 10a: AI and Affordability

Google's Pixel 10a arrives on March 5th, just a day after Apple's event. This is no coincidence. Google and Apple time their announcements to manage media attention and set the narrative for what consumers should expect.

The Pixel 10a is Google's affordable phone, competing directly with the rumored i Phone 17e. Both companies want to capture the budget phone market. But both are struggling with the same hardware costs.

Pixel phones are known for their computational photography. Google doesn't need the most advanced camera hardware because they process images with software and AI. A Pixel 10a with an older camera sensor but superior computational photography can compete with phones that have objectively better hardware.

Google also has advantages in AI and machine learning. The company developed TensorFlow, the most popular machine learning framework. They have TPUs (Tensor Processing Units) specifically designed for AI workloads. They can optimize their phone's AI features more effectively than competitors.

The Pixel 10a will likely focus on AI-powered features: real-time translation, voice commands, generative features. These are areas where Google has inherent advantages over Apple. Apple can copy these features, but Google developed the underlying research first.

Ring's Surveillance Plans: Privacy in the Age of AI

Emails leaked to media suggest that Ring, the Amazon-owned doorbell company, had plans to use its Search Party function for wider surveillance. This revelation is particularly troubling given the current conversation about social media addiction and tech company responsibility.

Ring's Search Party feature allows users to ask neighbors to review their doorbell footage when a crime occurs. It's presented as a community safety tool. But the leaked emails suggest Amazon was considering ways to expand this into something much broader: essentially, a network of civilian surveillance cameras that Amazon could access for reasons beyond the original community safety purpose.

This is the shadow side of the tech ecosystem. While we're arguing about social media addiction in courtrooms, companies are quietly expanding their surveillance infrastructure. Ring devices are in millions of homes. Most neighbors agree to share footage when asked. What happens if Amazon makes Search Party opt-out instead of opt-in? What if they start sharing footage with law enforcement without a warrant? What if they sell access to insurance companies or credit agencies?

The leaked emails suggest that Amazon was at least exploring these possibilities. The fact that the emails were leaked means someone inside the company was uncomfortable with the direction these discussions were heading. That's a good sign that there are still engineers and employees who care about privacy. But it's also a warning sign that without regulation, companies will push surveillance boundaries further than most people realize.

The Interconnection: Regulation, Privacy, and Corporate Power

The Instagram trial, RAMaggedon, and Ring's surveillance plans might seem disconnected. But they're all facets of the same problem: tech companies have become powerful enough to shape the world without clear oversight.

Meta's Instagram trial is about whether companies should be held responsible for addictive design. RAMaggedon shows how manufacturing concentration and supply chain fragility create vulnerabilities in our tech ecosystem. Ring's surveillance expansion shows how companies quietly expand into new capabilities that citizens never approved.

These aren't separate issues. They're interconnected. Companies with concentrated power can design addictive products because they face minimal legal consequences. Companies like Amazon and Apple can dominate hardware because manufacturing is expensive and complex. Surveillance expands because there are no clear regulatory frameworks preventing it.

The solution isn't simple. You can't just regulate design. That's too vague and too subjective. You can't just invest in manufacturing capacity. That requires coordination between countries and companies that have conflicting interests. You can't just ban surveillance. Ring doorbells are genuinely useful for home security.

But you could require transparency. You could mandate that companies disclose what data they collect and how they use it. You could require consent for surveillance expansion, not just the initial product. You could invest in alternative manufacturing capacity, like Intel's foundries or new plants in allied countries. You could regulate specific addictive practices—infinite scroll, notification badges, streaks—without banning the products entirely.

Listener Mail and Community Concerns

The podcast addressed listener mail, which revealed fascinating questions about the intersection of technology, addiction, and regulation. One listener asked whether the Instagram trial would actually change anything. It's a fair question.

Historical precedent suggests that legal victories against tech companies don't necessarily lead to meaningful change. The Microsoft antitrust trial of the early 2000s resulted in restrictions on bundling software, but didn't fundamentally alter how the company operated. The Facebook FTC settlement over Cambridge Analytica resulted in a

But there's reason for cautious optimism about the Instagram trial. Unlike previous cases, this one specifically addresses user harm rather than competition or privacy. If courts determine that Instagram was designed to exploit teenagers, that creates a precedent for other product liability cases. It opens up the possibility of class action suits against any tech company that can be shown to have deliberately designed addictive features.

That would change the incentive structure. Right now, the reward for addictive design is massive (more engagement, more ads, more revenue), while the cost is small (manageable fines, no product restrictions). If you change the risk-reward calculus so that the costs are genuinely high, companies will change their behavior.

Another listener asked about alternatives to Instagram. This is a harder question. The network effect is powerful in social media. Instagram is valuable because everyone's on it. A competitor with better design but fewer users isn't more appealing. You can't use it to reach your friends.

Decentralized platforms like Mastodon or Bluesky theoretically solve this problem. They're built on open protocols rather than closed platforms. But they're hard to use, have small communities, and lack the features that make Instagram valuable. Until there's a critical mass of users on an alternative, Instagram won't face real competition.

Pop Culture Picks: Context and Relief

At the end of the podcast, the hosts discussed pop culture picks—shows, movies, games, and other media. It might seem like a random tangent, but it serves an important purpose. After discussing addiction, surveillance, hardware shortages, and legal trials, audiences need a break. They need something fun, something human, something that reminds them that not everything in tech is dark and complicated.

This is actually a clever podcast technique. You end on a lighter note so audiences don't leave feeling anxious or hopeless. You give them something concrete they can enjoy rather than abstract problems they can't solve.

But it also highlights something important: we need balance. Tech can be overwhelming. The problems are real and significant. But life is also about entertainment, connection, and joy. The goal isn't to reject technology entirely. It's to use it more intentionally, more consciously, and with better understanding of how it's designed to influence us.

What Happens Next: The Legal Landscape

The Instagram trial is ongoing, but several potential outcomes are emerging. If the court rules in favor of the plaintiffs, Meta could face significant restrictions. The company might be required to change features that boost engagement. They might have to change how the algorithm works. They might face penalties or be forced to sell off Instagram as part of a breakup.

None of these outcomes are certain. Tech companies have massive legal resources. They can appeal decisions, challenge findings on technical grounds, and wait out trials. But the precedent matters. Once there's a finding that Instagram was deliberately designed to be addictive, other states can use that finding in their own cases. Other companies can be sued with similar logic.

The RAMaggedon will eventually stabilize, but it will take time. DRAM prices might not return to pre-shortage levels for another 12-18 months. By then, the damage will be done. Some companies will have exited the market. Manufacturing will be more consolidated. Innovation in consumer electronics will have slowed.

Ring's surveillance expansion will likely face pushback, but Amazon's resources are immense. Unless there's federal legislation, the company will keep pushing boundaries. The leaked emails are a warning, not a final stop.

The bigger picture is that tech companies have become powerful enough that regulation can't keep up with innovation. By the time lawmakers understand a problem and draft legislation, companies have already moved on to the next thing. The Instagram trial, RAMaggedon, and Ring's surveillance plans are just the symptoms of this deeper structural problem.

How Technology Shapes Society: The Bigger Picture

We don't usually think about a podcast episode as a lens on society. But the Engadget Podcast episode—discussing Instagram's addiction mechanics, hardware shortages, and surveillance expansion—tells a coherent story about how technology shapes our world.

First, there's the question of responsibility. Should Instagram be held accountable for designing an addictive product? Most people would say yes. But defining addiction in legal terms is harder. Is infinite scroll addictive? Is the algorithm's engagement optimization addictive? Or is it just using good design principles? These are genuinely hard questions that courts will have to answer.

Second, there's the question of resilience. RAMaggedon shows how fragile our supply chains really are. We depend on a handful of companies making memory chips, and when they can't keep up with demand, everything downstream breaks. This isn't just an inconvenience. It's a vulnerability. If a geopolitical conflict interrupted TSMC's operations for even a few months, the global tech economy would face a crisis.

Third, there's the question of privacy and surveillance. Ring's doorbell cameras are genuinely useful for home security. But the expansion into neighborhood-wide surveillance networks raises important questions about consent and oversight. At what point does a security tool become a surveillance network?

Fourth, there's the question of innovation and consolidation. RAMaggedon will kill smaller companies, which means there's less innovation at the edges. Apple, Google, Meta, and Amazon will survive and thrive. But the ecosystem will be less diverse, less dynamic, less creative.

These aren't just tech problems. They're society-level problems that happen to manifest through technology. Regulation, investment in alternatives, transparency requirements, and better governance are all part of the solution. But none of these happen without pushback and pressure from informed citizens who understand what's at stake.

The Role of Journalism in the Tech Era

The Engadget Podcast plays an important role in this ecosystem. It covers tech news, but it does so with skepticism and depth. The hosts don't just report what companies announce. They ask hard questions about what these announcements mean, what the incentives are, what the second-order effects will be.

Journalism like this is crucial because most tech coverage is either puff pieces (company X launches product Y!) or doom-mongering (the internet is ruined!). The Engadget Podcast tries to walk the middle ground: understanding what's actually happening, why it's happening, and what it means.

The Instagram trial coverage illustrates this. The hosts didn't just report that Zuckerberg testified. They contextualized it: What does this trial mean for other companies? How could the outcome affect product design across the industry? What are the broader implications for regulation and innovation?

This kind of journalism requires expertise. You need to understand tech deeply to explain it well. You need to understand policy to explain legal implications. You need to understand business to explain economic incentives. The hosts do all three, which makes the podcast valuable.

Future Trends in Social Media Regulation

Based on the Instagram trial and broader regulatory trends, we can anticipate several changes to social media in the coming years.

First, expect more litigation. If the Instagram trial results in a victory for plaintiffs, other states will file similar suits against Meta, Tik Tok, Snapchat, and You Tube. This will likely lead to some regulatory settlement or legislation rather than individual trials.

Second, expect the FTC to become more aggressive. The Federal Trade Commission has authority over unfair and deceptive practices. They could theoretically challenge any design pattern that's deliberately exploitative. The agency has signaled that they're interested in this space.

Third, expect more transparency requirements. Even if courts don't restrict addictive design, they might require companies to disclose how their algorithms work and what metrics they optimize for. Transparency doesn't solve the problem, but it makes it harder for companies to hide.

Fourth, expect some level of age restriction. The trial is specifically about harm to teenagers. Even if the broader case fails, we might see age verification requirements or content restrictions for minors.

Fifth, expect companies to develop "less addictive" alternatives. If regulation is coming, smart companies will get ahead of it by designing products that are optimized for user wellbeing rather than engagement. This might actually lead to better products—less maximizing metrics, more maximizing actual value to users.

Broader Implications for the Tech Industry

The convergence of the Instagram trial, RAMaggedon, and surveillance expansion has broader implications for the entire tech industry.

First, tech companies are learning that they can't operate without accountability. The days when tech was entirely unregulated are over. Companies now have to account for how their products affect society, how they source materials, how they treat workers, and what data they collect.

Second, tech companies are learning that supply chain resilience matters. The companies that survive the next decade are those that can adapt to hardware shortages, geopolitical disruption, and regulatory challenges. Vertical integration and diversity of suppliers are suddenly strategically important again.

Third, tech companies are learning that innovation has limits. You can optimize a feed, improve an algorithm, and add new features. But if the underlying design is unsustainable—addictive to users, exploitative of labor, environmentally damaging—it will eventually face pushback. The sustainable companies will be those that innovate within constraints, not those that treat constraints as problems to overcome.

Fourth, tech companies are learning that public trust matters. Meta's brand has been damaged by repeated scandals. Instagram's reputation with parents and teens is becoming toxic. Companies that prioritize trust and transparency will have advantages in competing for users.

These are big, structural changes. They're not happening overnight. But the trajectory is clear. The tech industry is moving from an era of "move fast and break things" to an era of "move carefully and build sustainable things."

Conclusion: Connecting the Dots

The Engadget Podcast episode was ostensibly about three separate stories: Instagram's addiction trial, RAMaggedon, and Ring's surveillance plans. But these stories are connected by deeper themes about responsibility, resilience, and how technology shapes society.

Mark Zuckerberg's testimony that Instagram was built to be useful, not addictive, is technically true. The platform is useful. But usefulness and addiction aren't opposites. Instagram is useful because it's addictive. The company consciously designed features to maximize engagement and minimize friction. The question isn't whether Instagram is useful. The question is whether that utility comes at a cost to users' wellbeing.

RAMaggedon is a reminder that technology isn't inevitable. We don't automatically get faster computers, better consoles, and more capable phones. Supply chains can break. Manufacturing capacity is limited. And when the supply of crucial materials becomes constrained, the entire ecosystem suffers.

Ring's surveillance expansion is a reminder that the tools we voluntarily invite into our homes can be used in ways we never intended. A doorbell camera is useful for security. But a doorbell camera network controlled by Amazon is a surveillance infrastructure. We need to think more carefully about what we're building and what unintended consequences it might have.

The common thread is that technology isn't neutral. It embodies choices. Instagram embodies choices about engagement and metrics. Hardware manufacturing embodies choices about where production happens and how many suppliers you depend on. Surveillance cameras embody choices about who controls the data and what it's used for.

When we buy products, use platforms, or invite devices into our lives, we're accepting those embedded choices. As societies, we should become more conscious of those choices and demand better ones. The Instagram trial is a step in that direction. It forces companies to articulate their design decisions under oath. It creates space for legal accountability. It signals that addiction-by-design isn't acceptable.

RAMaggedon is another kind of signal. It shows that consolidation in manufacturing creates fragility. Resilience requires redundancy, which is inefficient but necessary. As we move through an era of geopolitical tension and climate disruption, building robust and redundant systems matters more than optimizing for efficiency.

Ring's surveillance expansion is a third signal. It shows that without clear frameworks and regulation, companies will expand their capabilities into ethically gray areas. Proactive regulation that sets clear boundaries is better than reactive litigation after damage is done.

The path forward isn't to reject technology. It's to shape technology more intentionally, with better understanding of second-order consequences. It's to demand accountability from companies. It's to invest in resilience. And it's to have more conversations like the one in this Engadget Podcast episode.

FAQ

What was Mark Zuckerberg's testimony about in the Instagram trial?

Mark Zuckerberg testified that when Meta acquired Instagram, the company intended to make it useful rather than addictive. However, the trial is examining whether Instagram's design features—including infinite scroll, algorithmic feeds, and engagement-focused notifications—were deliberately engineered to maximize user engagement in ways that could be considered addictive. The testimony is part of a broader case examining whether social media platforms should be held responsible for designing addictive products, particularly those that affect teenagers.

How does Instagram's algorithm work to increase engagement?

Instead of showing a chronological feed of posts from accounts you follow, Instagram uses an algorithmic feed that displays content the company's AI predicts you'll engage with most. The algorithm prioritizes posts that generate likes, comments, and shares. Instagram also employs engagement-boosting features like Stories (which disappear after 24 hours, creating urgency), streaks (which create social obligation), and notifications (which draw you back into the app). Additionally, the platform uses infinite scroll to eliminate natural stopping points, making it harder to disengage.

What is RAMaggedon and why does it matter?

RAMaggedon refers to a critical shortage and price spike in DRAM (Dynamic Random Access Memory) chips. The shortage was triggered by pandemic-era supply chain disruptions, but has persisted because DRAM manufacturing capacity is extremely limited—just three companies (SK Hynix, Samsung, and Micron) control over 95% of global production. When demand spikes, there's no way to quickly increase supply, causing prices to surge. This affects all consumer electronics, from laptops to gaming consoles to smartphones, making them more expensive or delaying their release.

How will RAMaggedon affect smaller electronics manufacturers?

Smaller companies lack the resources and scale to absorb rising DRAM costs that larger competitors like Apple and Samsung can handle. These companies face three difficult options: absorb losses (unsustainable), raise prices (pricing themselves out of markets), or reduce product specifications (making products less competitive). Many smaller manufacturers will exit the market or be acquired by larger competitors, leading to industry consolidation, reduced innovation, and less competitive diversity in consumer electronics.

Why is the Instagram trial significant for tech regulation?

The trial represents a new form of legal accountability for tech companies. Rather than focusing on privacy violations or monopolistic behavior (as in previous cases), this trial examines whether product design itself can constitute harm. If courts determine that Instagram was deliberately designed to be addictive, it creates legal precedent for regulating how all tech companies design their products. This could lead to restrictions on specific engagement-maximizing features like infinite scroll, notification badges, or algorithm-driven feeds.

What are the implications of Ring's surveillance expansion plans?

Emails leaked to journalists revealed that Amazon's Ring subsidiary was exploring ways to expand its Search Party community safety feature into a broader surveillance network. This suggests the company was considering using doorbell camera footage beyond its original community safety purpose. The incident highlights how tools initially presented as helpful features can be expanded into surveillance infrastructure without clear user consent or oversight, raising important questions about privacy, consent, and the role of regulation in preventing technology creep.

What might the Play Station 6 delay tell us about the tech industry?

If the Play Station 6 is delayed due to RAMaggedon, it signals that even the largest technology companies can be constrained by hardware supply chains. Console manufacturers face the difficult decision of either launching at higher price points (risking sales) or delaying until supply improves. This illustrates how fragile our tech ecosystem is when crucial materials are sourced from only a few manufacturers, and suggests that geopolitical disruptions could create genuine crises in the consumer electronics industry.

How should consumers think about social media addiction?

Consumers should recognize that social media platforms are optimized for engagement through deliberate design choices. Features like notifications, streaks, algorithmic feeds, and infinite scroll aren't neutral—they're engineered to maximize time spent. Understanding this helps users make more conscious choices about their usage. Practical strategies include disabling notifications, setting screen time limits, using chronological feeds when available, and taking regular breaks from platforms.

What regulations might result from the Instagram trial?

Potential regulatory outcomes could include restrictions on specific addictive design patterns, transparency requirements mandating disclosure of how algorithms work, age verification and content restrictions for minors, and product liability penalties for deliberately exploitative features. Additionally, the trial might inspire federal legislation rather than state-by-state regulation, and could embolden the FTC to challenge other tech companies' practices under unfair and deceptive practices standards.

Key Takeaways

- Instagram trial sets precedent for holding tech companies accountable for addictive design patterns and algorithmic optimization practices

- RAMaggedon semiconductor shortage creates supply chain vulnerabilities affecting all consumer electronics, with smaller manufacturers facing elimination

- Only three companies control 95% of DRAM manufacturing, making the global tech ecosystem fragile and dependent on few suppliers

- Meta is launching smartwatch despite hardware cost crisis, suggesting focus on wearable surveillance and hardware ecosystem control

- Amazon's Ring expansion plans show how surveillance features can expand beyond original purpose without user consent or oversight

- Next-generation hardware (PlayStation 6, iPhone 17e, Pixel 10a) faces cost pressures from DRAM shortage, affecting innovation and consumer choice

Related Articles

- Mark Zuckerberg's Testimony on Teen Instagram Addiction [2025]

- Prediction Markets Battle: MAGA vs Broligarch Politics Explained

- Roblox Lawsuit: Child Safety Failures & Legal Impact [2025]

- Rubik's WOWCube Review: Can Smart Technology Improve the Classic Puzzle? [2025]

- Palantir's $1 Billion DHS Deal: What It Means for Immigration Surveillance [2025]

- Apple's iCloud CSAM Lawsuit: What West Virginia's Case Means [2025]

![Instagram on Trial: Meta's Addiction Battle and Tech's RAM Crisis [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/instagram-on-trial-meta-s-addiction-battle-and-tech-s-ram-cr/image-1-1771594579534.jpg)