Introduction: What Meta Didn't Want You to Know About Parental Controls

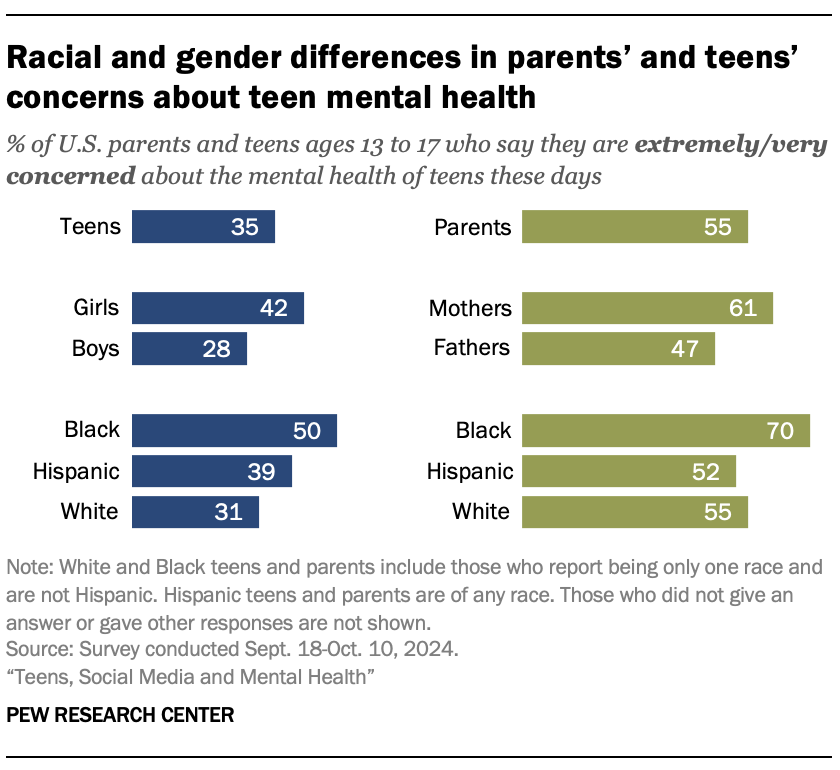

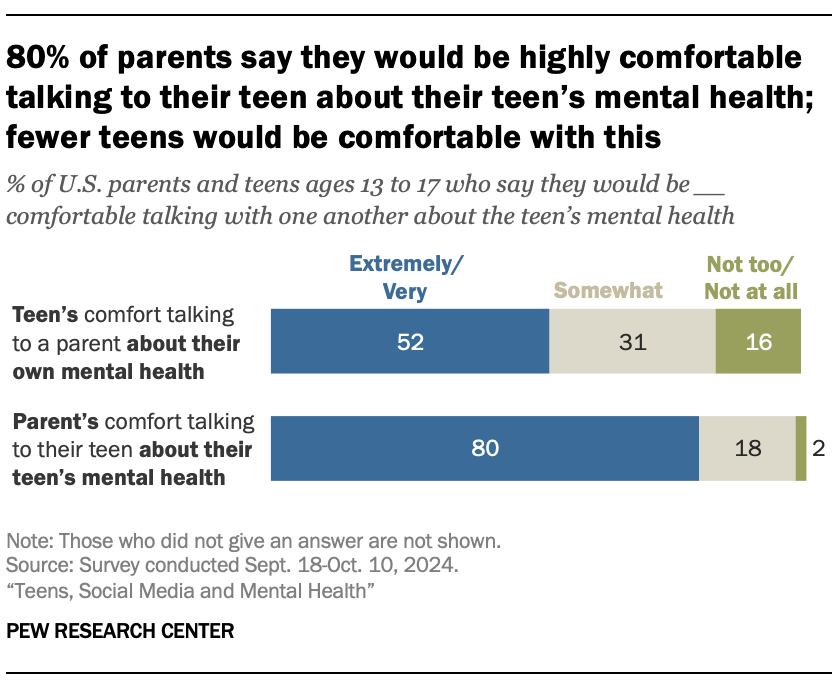

Let me set the scene. It's February 2025, and lawyers are cross-examining Instagram's head of product in a Los Angeles courtroom. The plaintiff is a teenager identified as Kaley, suing Meta alongside other social media companies for knowingly creating addictive products that destroyed her mental health. Then the lawyer drops something unexpected: an internal Meta research study suggesting that all those parental controls parents frantically install? They barely work.

Meta calls it "Project MYST." The acronym stands for Meta and Youth Social Emotional Trends. And the findings, revealed during testimony in what's become a landmark social media addiction trial, fundamentally challenge how we think about protecting young people online.

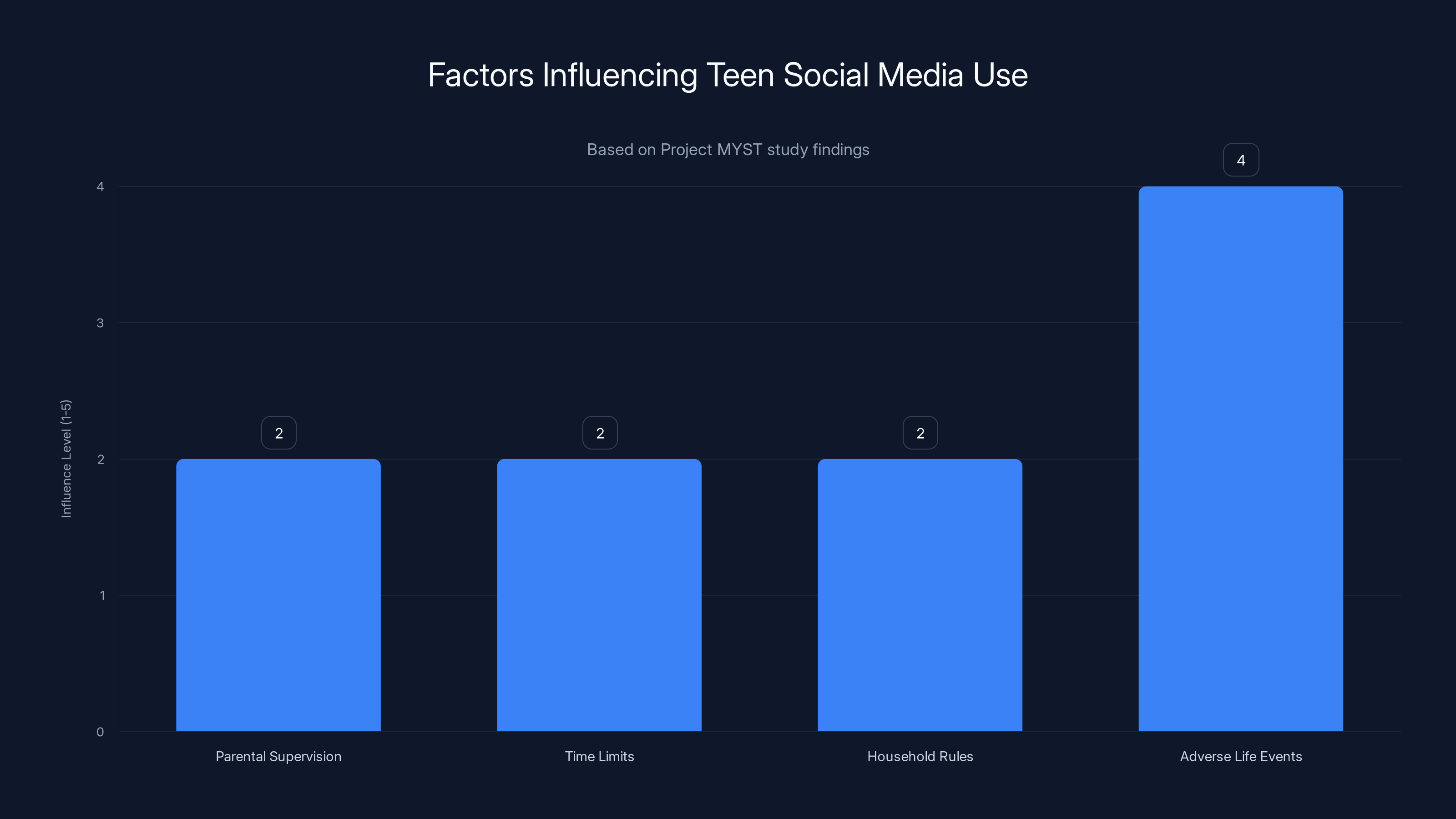

Here's the uncomfortable truth buried in the research: parental supervision—time limits, restricted access, household rules, all of it—had "little association" with whether teens would compulsively use social media. Even more alarming, the study found that teens dealing with trauma, stress, or adverse life experiences were significantly more vulnerable to problematic social media use, regardless of parental intervention.

This isn't some fringe study from an obscure research lab. This is Meta's own research. Conducted with the University of Chicago. Based on surveys of 1,000 teens and their parents. And according to trial testimony, Meta never published it. Never warned parents. Never issued guidance to teens. It just... existed in internal documents while the company continued rolling out features designed to maximize engagement.

The implications are staggering. If parental controls don't work, then responsibility shifts. It's not about better parenting. It's about the products themselves. It's about the algorithms. The variable rewards. The notifications engineered to trigger dopamine responses. The design choices made in Menlo Park that make scrolling harder to stop than checking your email.

This article dives deep into what Project MYST actually found, why it matters, what it reveals about Meta's knowledge of its products' effects on young people, and what comes next for parents, regulators, and the teenagers caught in the middle.

TL; DR

- Parental controls barely work: Meta's Project MYST study found parental supervision had "little association" with teens' compulsive social media use

- Trauma makes it worse: Teens experiencing adverse life events showed significantly less ability to self-regulate their social media consumption

- Meta knew but didn't tell: The research was never published, and no public warnings were issued despite findings suggesting known harms

- Responsibility shifted: Trial lawyers used the study to argue that blame belongs with platform design choices, not parental oversight

- Legal implications matter: This research is now evidence in landmark addiction lawsuits that could reshape social media regulations and policies

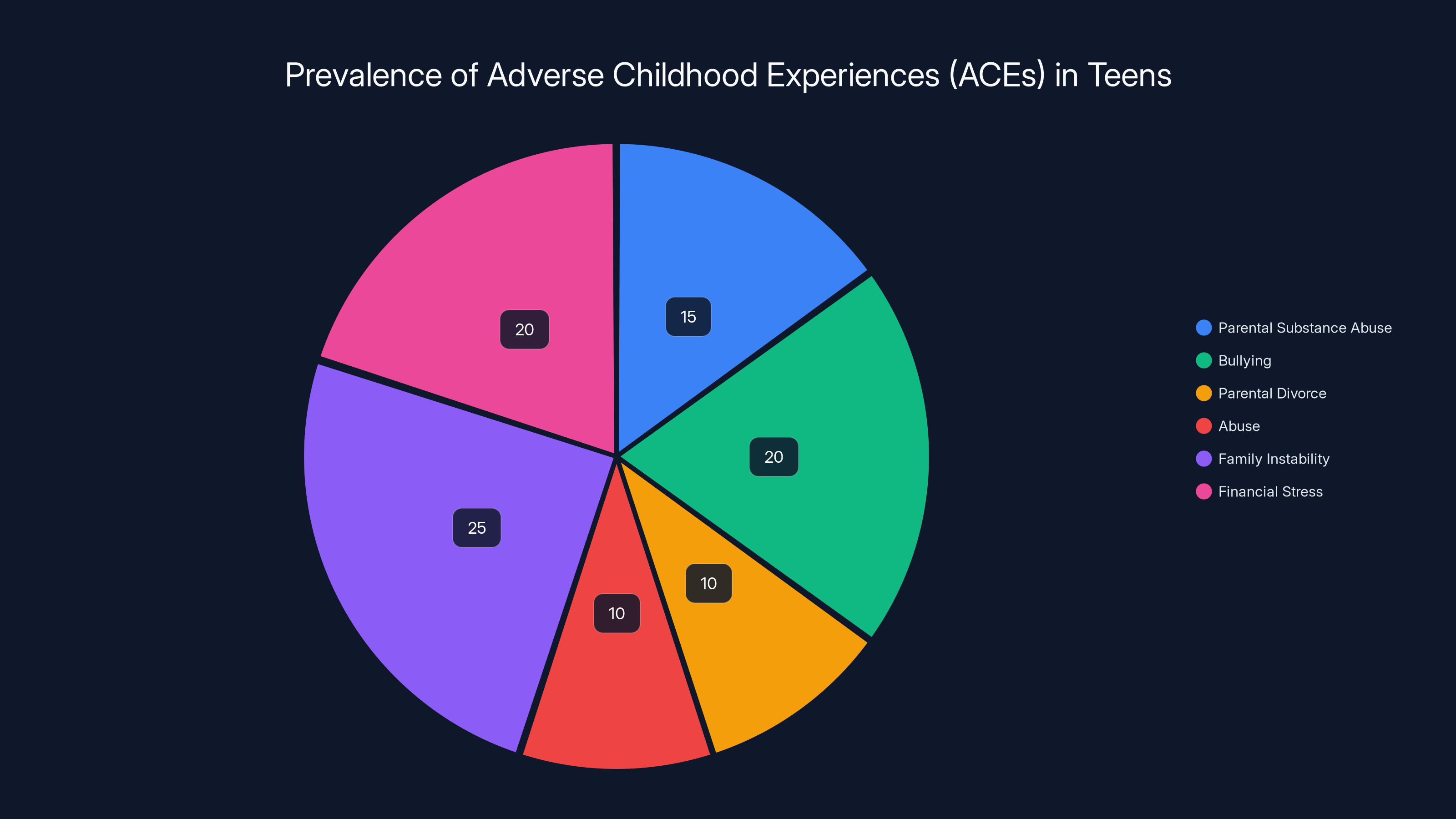

Project MYST found that adverse life events had a higher influence on compulsive social media use among teens compared to parental supervision, time limits, or household rules. Estimated data based on study insights.

The Project MYST Study: What Exactly Did Meta Research?

Project MYST wasn't some casual survey Meta ran on a Thursday afternoon. This was a formal research initiative conducted in partnership with the University of Chicago, featuring a structured methodology and peer-level analysis. The study examined the relationship between parental involvement and teen social media use patterns.

The survey included 1,000 teenagers and their parents. Researchers asked questions about household supervision, parental controls, time limits, and household rules around social media. They also measured teens' reported levels of "attentiveness" to social media use—essentially, how aware were teens of how much time they spent, and whether they felt they were using it excessively.

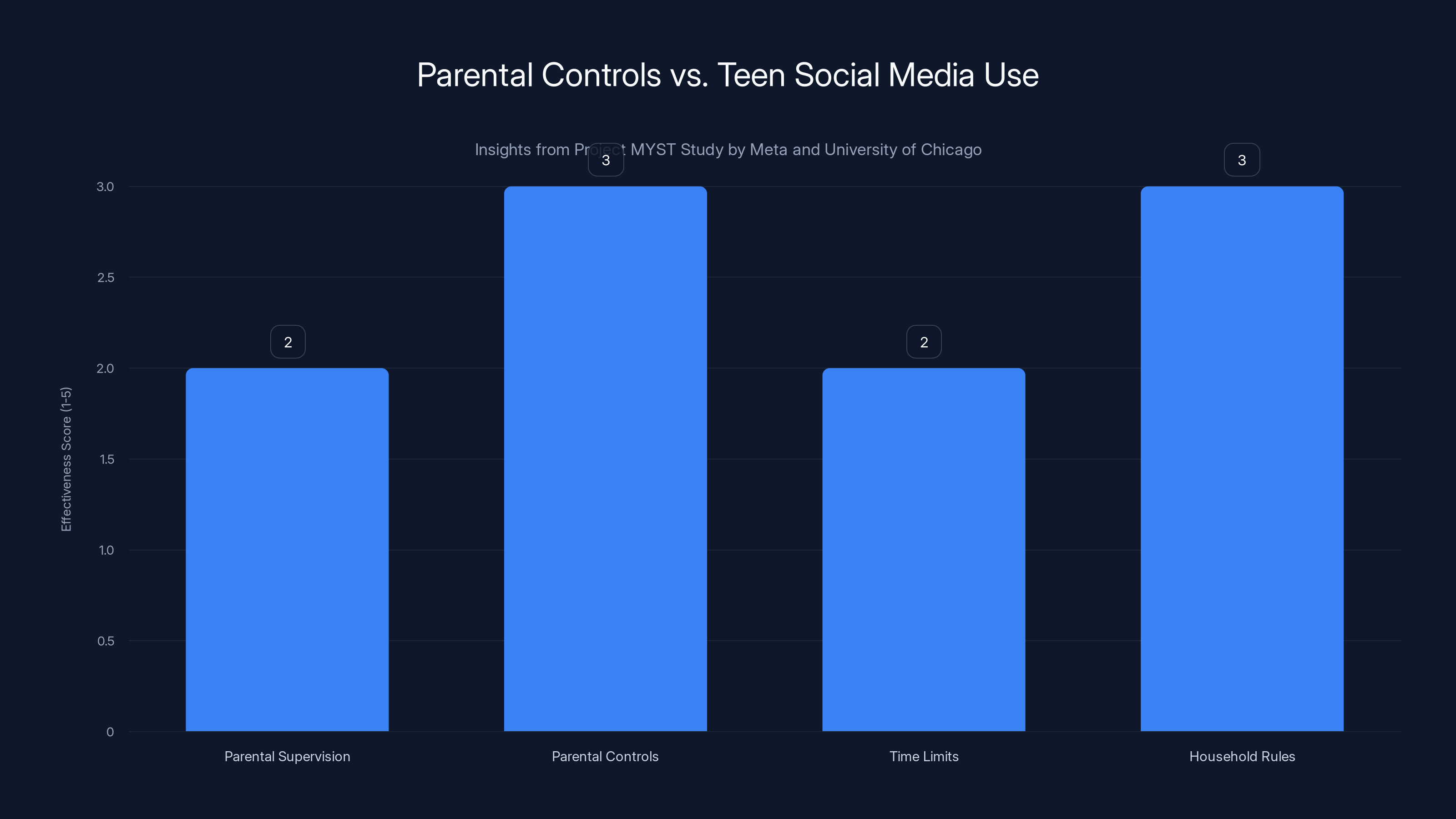

The findings were straightforward but counterintuitive. There was no meaningful correlation between what parents did (implementing controls, setting rules, supervising) and whether teens engaged in compulsive or problematic social media use. Parents reported supervising their kids. Teens reported being supervised. But neither group's reports predicted actual usage patterns or the teens' ability to self-regulate.

Why is this surprising? Because it contradicts the conventional wisdom. Parents are told to set screen time limits. Schools run digital wellness programs teaching "healthy" social media habits. Instagram itself offers built-in parental controls featuring time limit reminders and activity reports. All of this is premised on the assumption that external structure and oversight help teens moderate their use.

Meta's own research suggested otherwise.

The study also examined both parental reports and teen reports of supervision independently. The agreement between parents and teens was notable—they largely agreed on whether supervision was happening. But that agreement didn't translate into agreement on outcomes. Supervised teens still engaged in problematic use at similar rates to unsupervised teens. The disconnect was real and measurable.

According to testimony, the study's key conclusion stated: "there is no association between either parental reports or teen reports of parental supervision, and teens' survey measures of attentiveness or capability." That's research-speak for: "Parental supervision doesn't predict whether kids will overuse social media."

Now, Meta's lawyers later argued that Project MYST was narrowly focused on teens' perception of their own use, not addiction itself. They claimed the study measured subjective feelings about attentiveness, not actual behavioral addiction. That's a meaningful distinction in legal terms, but it doesn't change the fundamental finding: external parental controls didn't move the needle on how teens felt about their relationship with these platforms.

The chart shows a significant increase in teen mental health issues from 2010 to 2023, with emergency visits for psychiatric crises rising by 73% from 2016 to 2022. Estimated data highlights the growing concern over depression and anxiety diagnoses.

Why Parental Controls Fail: The Design Problem

To understand why Meta's research found parental supervision ineffective, you need to understand what parental controls actually do—and what they don't.

Parental controls typically work at three levels. First, time-based controls: setting daily limits, restricting access during certain hours, forcing notifications when limits approach. Second, content-based controls: filtering what content can be viewed, blocking certain features or accounts. Third, oversight controls: parents viewing activity reports, seeing messages and posts, monitoring who's connecting with their teen.

On the surface, this sounds comprehensive. A parent could theoretically limit their teen's Instagram use to 30 minutes daily, prevent access between 9 PM and 8 AM, monitor who's following them, and review what they're interacting with.

But here's the problem: none of this addresses the actual mechanism driving compulsive use.

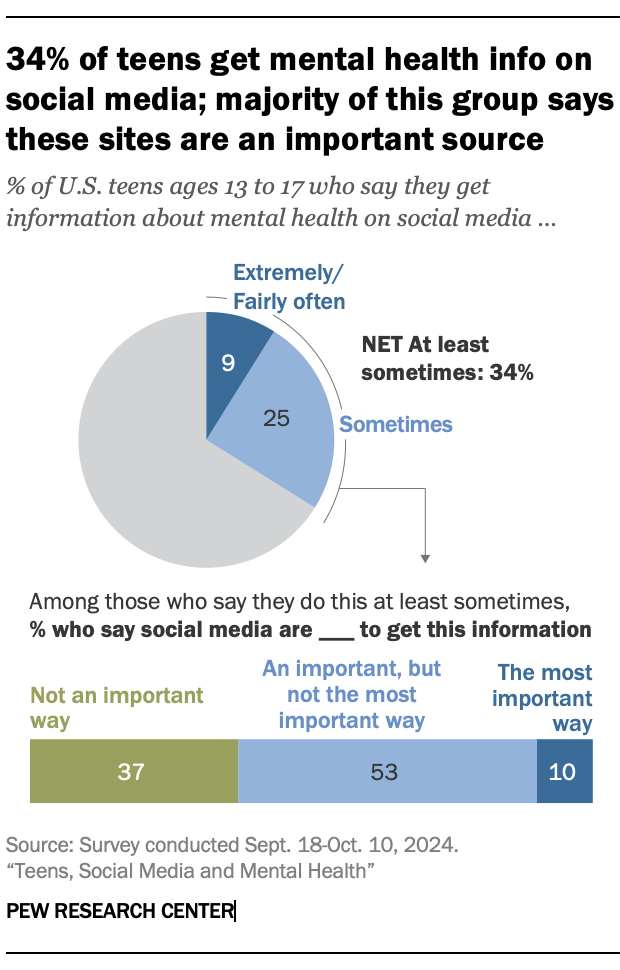

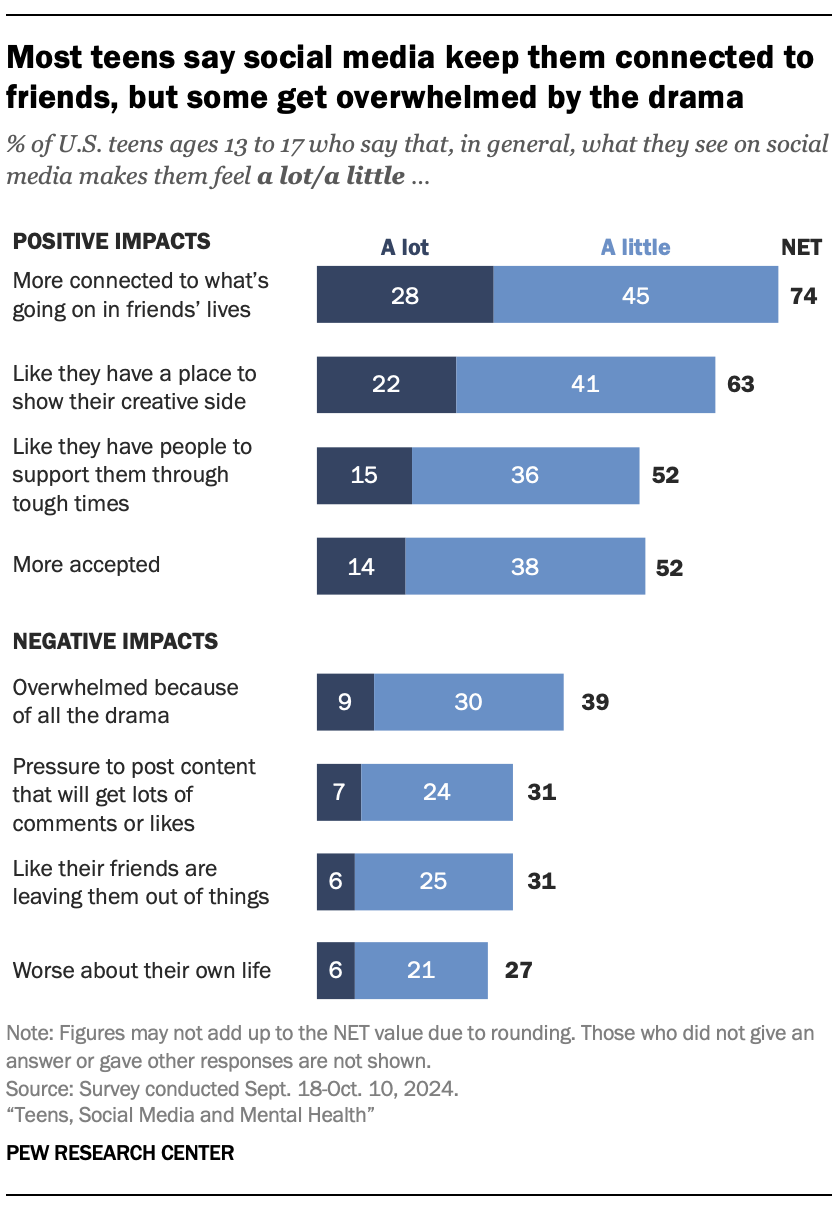

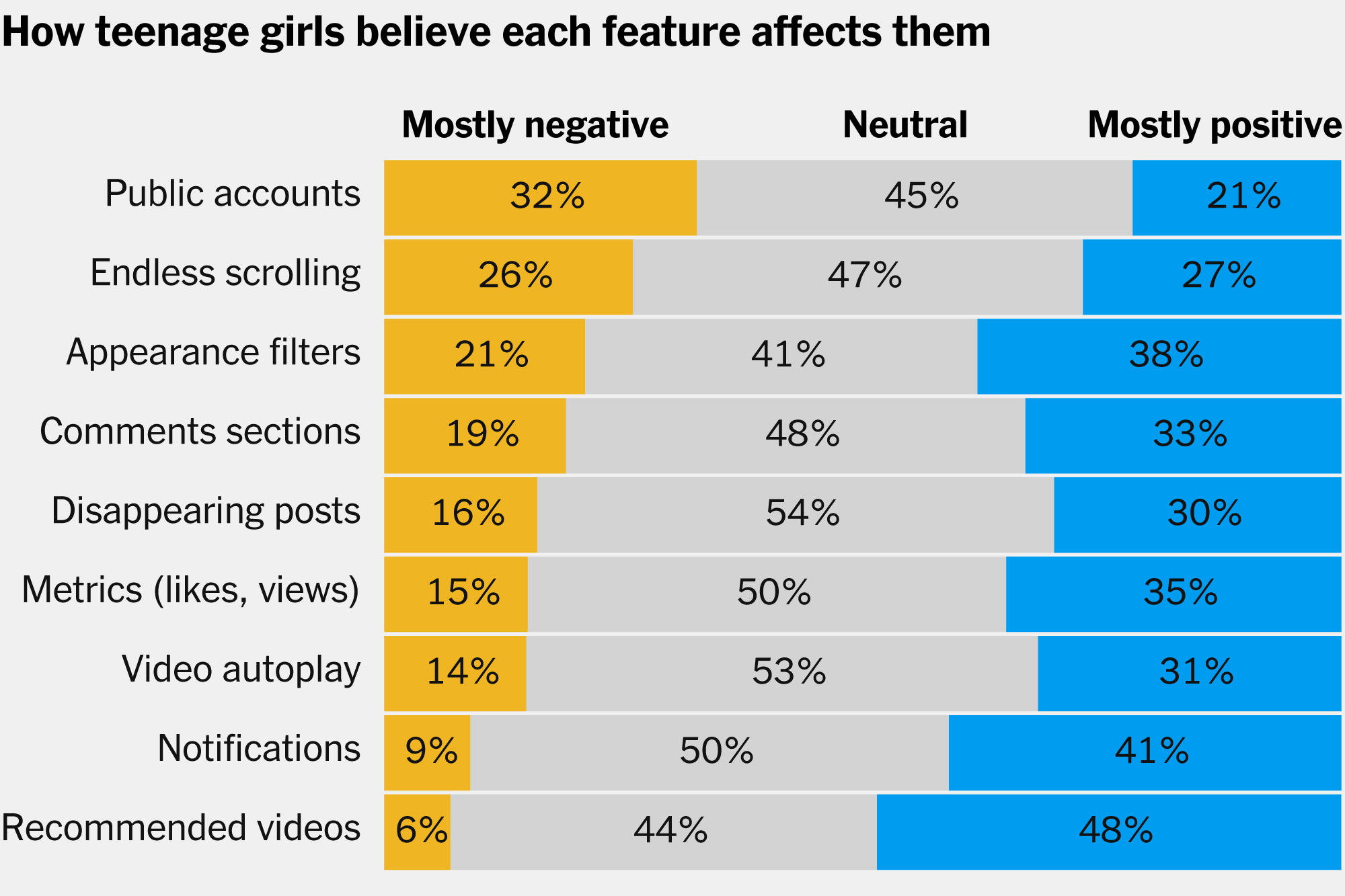

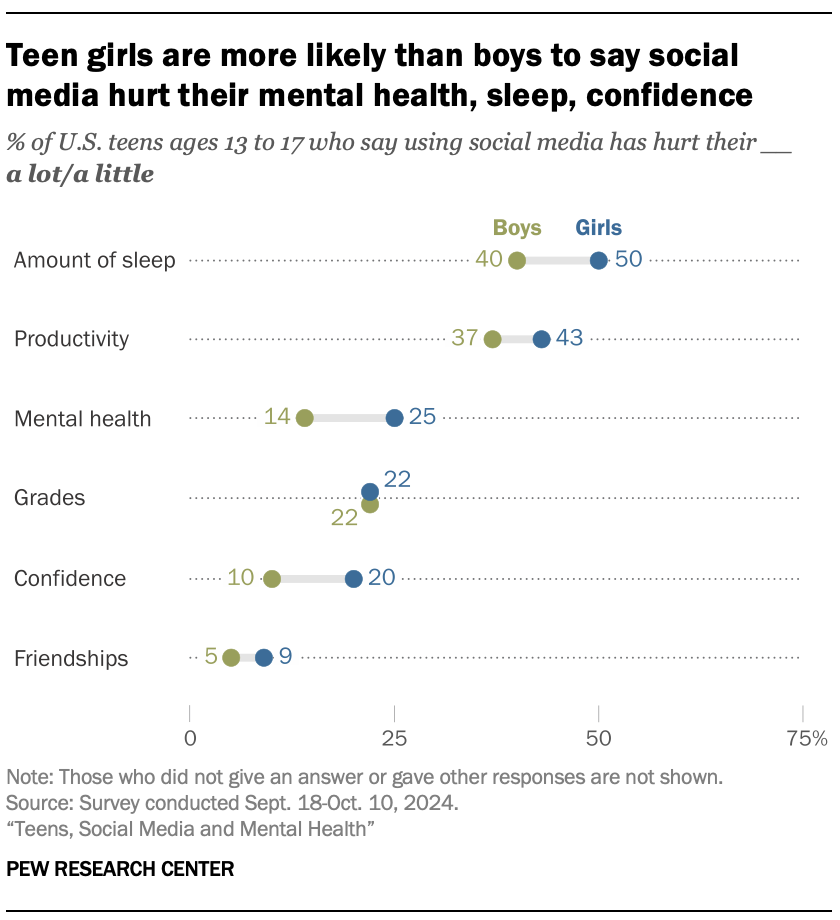

When you open Instagram or Tik Tok, you're not just scrolling through content you want to see. You're engaging with algorithmic feeds specifically engineered to maximize engagement. These feeds use reinforcement patterns called variable ratio reinforcement—you don't know what you'll find as you scroll, and that unpredictability is neurologically compelling. Sometimes you'll see something you love. Sometimes something you hate. Usually something you find just engaging enough to keep scrolling.

Notifications work similarly. They're timed, personalized, and designed to interrupt whatever you're doing with messages about activity on your account or new content from accounts you follow. A parent can disable notifications, but that requires teenagers to actively disable their own FOMO (fear of missing out) mechanisms—which is asking adolescents to overcome design built by engineers who've studied persuasion psychology for years.

The algorithmic problem is particularly vexing for parental controls. You can limit your teen's time on the app, but you can't change what Instagram's algorithm recommends during those limited sessions. If the algorithm is designed to serve the most engaging content (often content that triggers anxiety, jealousy, or comparison), then even a 15-minute session might do psychological damage. And if your teen is dealing with mental health challenges or trauma, they might be especially vulnerable to using those 15 minutes to escape from difficult emotions.

Meta's own product team understands this. Instagram head Adam Mosseri, testifying in the trial, acknowledged that people use Instagram "as a way to escape from a more difficult reality." That admission is critical. If the app's primary function for vulnerable users is escape, then controlling time spent on it doesn't address the underlying issue driving use.

Parental controls also have a practical limitation: they can be circumvented. Teens are digitally native. They know how to use different devices, guest accounts, friends' phones, or settings parents haven't discovered. They understand that Instagram on the web doesn't have the same restrictions as Instagram on i OS. They know about VPNs, private browsers, and deleted app caches. A determined teenager can work around most parental controls.

But even if parental controls couldn't be circumvented, Project MYST suggests they wouldn't meaningfully reduce problematic use anyway. The study suggests that the drivers of compulsive social media use run deeper than time limits can reach.

The Trauma Finding: Why Adverse Experiences Make Teens Vulnerable

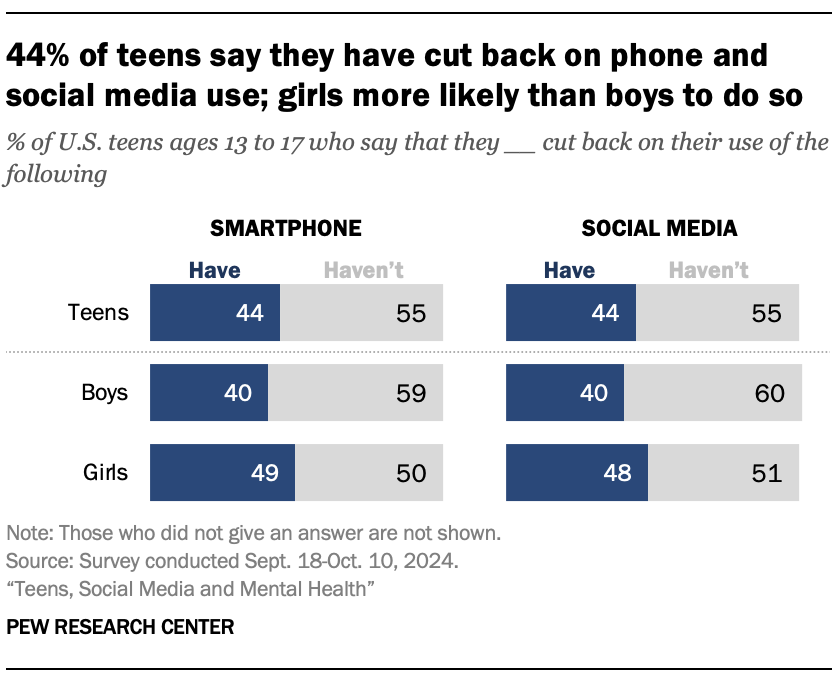

Project MYST contained another critical finding that received less attention in initial trial coverage but carries profound implications: teens who experienced adverse life events reported significantly less ability to moderate their social media use.

The study defined adverse life experiences broadly. Parental substance abuse. Bullying at school. Parental divorce. Abuse. Family instability. Financial stress. Loss or grief. These aren't rare experiences—studies suggest approximately 50-60% of teens experience at least one adverse childhood experience (ACE).

When researchers looked at the relationship between ACEs and social media use, the pattern was unmistakable. Teens dealing with trauma reported lower "attentiveness" to their social media use. They felt less in control. They spent more time than they wanted. They scrolled compulsively even when they meant to limit time.

This finding aligns with psychological research on self-regulation. The brain's prefrontal cortex, responsible for impulse control and self-regulation, is still developing in adolescence and is particularly vulnerable to chronic stress. When a teen is dealing with trauma, anxiety, or depression, the cognitive resources available for self-regulation diminish. It's neurologically harder to say no to the phone.

Social media, then, becomes a form of emotional regulation. When a teen is anxious, depressed, or dealing with bullying at school, scrolling provides immediate relief through distraction and social connection (or the simulation thereof). The algorithm senses engagement and serves more of whatever holds their attention. A feedback loop develops.

Mosseri acknowledged this dynamic during trial. He noted that there were "a variety of reasons" people use Instagram to escape difficult realities. The implication is clear: for the most vulnerable teenagers, parental controls become irrelevant. The app isn't a discretionary entertainment choice. It's a coping mechanism.

This creates a moral problem for Meta. If the company knows that traumatized teens are more vulnerable to compulsive use, and if it designs features to maximize engagement without accounting for that vulnerability, is it exploiting that vulnerability? Trial lawyers certainly think so. The lawsuit explicitly argues that Meta's products are designed as "addictive and dangerous," with algorithmic feeds, variable rewards, and notifications deliberately engineered to exploit psychological vulnerabilities.

The fact that Project MYST identified this vulnerability and Meta didn't publish the findings or adjust product design accordingly is being used as evidence of knowing harm.

The Project MYST study found no significant correlation between parental actions like supervision, controls, and rules, and the reduction of compulsive social media use among teens. Estimated data based on study insights.

Inside the Courtroom: How Project MYST Became Trial Evidence

The social media addiction trial featuring Kaley's case is one of several landmark lawsuits filed in 2025 challenging social media companies' responsibility for teen mental health harms. Similar cases have been brought against Meta, YouTube, TikTok, and Snapchat, though TikTok and Snapchat settled before trial.

The trial's central argument is straightforward: social media companies knowingly designed addictive products that harmed teenagers. The companies knew these products would cause anxiety, depression, eating disorders, body dysmorphia, and in severe cases, self-harm. They designed them anyway because addiction equals engagement, and engagement equals advertising revenue.

Kaley's lawyer, Mark Lanier, brought Project MYST into evidence to support a specific argument: parental responsibility is insufficient. Parents can't prevent harm if the platform is designed to be harmful. Blame belongs with the company and its design choices, not with parents who are already doing everything they're told to do.

Kaley's mother, Lanier noted, had tried everything. She supervised her daughter. She set rules. She took the phone away at times. It didn't work. Why? Because Instagram wasn't designed to accommodate parental oversight. It was designed to maximize engagement, particularly for vulnerable users like her daughter.

Lanier used Project MYST to establish that Meta knew parental supervision was ineffective. The study was internal knowledge. Mosseri had apparently approved moving forward with the project. But Meta never published the findings. Never updated its parental controls based on findings showing they don't work. Never warned parents that oversight alone couldn't protect their children.

Mosseri's testimony complicated this narrative somewhat. He claimed not to remember Project MYST specifically, despite documents suggesting his approval. "We do a lot of research projects," he said. This response—not remembering specific research findings—plays into a broader critique of how Meta operates: the company runs research, documents harms and vulnerabilities, and then doesn't act on the findings.

Meta's legal team approached the trial differently. They argued that Project MYST measured subjective perceptions of attentiveness, not actual addiction. The study showed teens felt they weren't monitoring their own use well, not that they were addicted. That's a valid methodological point—self-reported attentiveness is different from diagnosable addiction.

Meta's lawyers also shifted responsibility toward life circumstances. Kaley, they noted, had experienced parental divorce, had an abusive father, and faced bullying at school. Those were the real drivers of her mental health struggles, not Instagram. Social media was a symptom of her distress, not the cause.

This defense strategy highlights a genuine complexity in the causality question: does social media cause mental health problems, or do people with mental health problems use social media more heavily? The research on this question is mixed. Some studies suggest social media causes anxiety and depression. Others suggest people experiencing anxiety and depression self-select into heavy social media use for coping or connection.

But Project MYST doesn't really address that causality question. It simply shows that parental oversight doesn't prevent heavy use. The "why" of heavy use—whether it's driven by platform design, personal vulnerabilities, or both—remains open to interpretation.

Still, from the plaintiff's perspective, the distinction doesn't matter much. If a product is designed such that vulnerable people will use it compulsively regardless of parental intervention, the company has a responsibility to either design differently or warn more clearly. Project MYST, in this view, is evidence that Meta knew parental controls wouldn't prevent harm and did nothing about it.

What "Problematic Use" Really Means: Meta's Terminology Problem

Meta refuses to use the word "addiction" when describing heavy social media use. Instead, the company uses euphemisms like "problematic use" or references to spending "more time on Instagram than they feel good about."

This isn't just semantics. The distinction between "problematic use" and "addiction" carries enormous weight in trials and regulatory discussions.

Addiction, in clinical terms, requires meeting specific diagnostic criteria. It involves compulsive engagement despite negative consequences, tolerance (needing more of the substance to achieve the same effect), and withdrawal symptoms when access is removed. The DSM-5, psychology's diagnostic manual, doesn't yet include "social media addiction" as an official diagnosis (though "Internet Gaming Disorder" is being studied).

"Problematic use" is vaguer. It could mean spending more time than intended. It could mean using it in inappropriate contexts. It could mean neglecting other responsibilities. But it doesn't necessarily imply the neurological changes and behavioral patterns that characterize addiction.

Meta's choice of terminology matters in court. If Meta can argue it's discussing problematic use, not addiction, it can push back against claims that the company designed addictive products. The company can argue it's facilitating engagement, not addiction, a distinction that's legally important.

But Project MYST's findings suggest this distinction might be misleading. The study describes teens who reported low "attentiveness" to their use—essentially, teens who scrolled compulsively even when they didn't intend to, who felt out of control. That sure sounds like addiction, regardless of what clinical definition you use.

Mosseri's own admission that people use Instagram to escape difficult realities implies addictive patterns. Escape behavior, psychological reinforcement through variable rewards, and compulsive engagement despite discomfort are all hallmarks of addiction, not just problematic use.

The DSM-5 note on Internet Gaming Disorder mentions symptoms that directly parallel heavy social media use: preoccupation with the activity, withdrawal symptoms when unable to engage, tolerance requiring increased engagement, unsuccessful attempts to control use, loss of interest in other activities, continued excessive use despite problems, deception about use, and using the activity to escape negative moods.

That's a pretty good description of what Project MYST describes as "problematic use."

The terminology choice also affects how parents and teens understand the issue. If Meta calls it "problematic use," parents might think a behavior change or conversation could help—that it's a matter of discipline or habit. If it's addiction, parents might understand they need professional intervention, that this isn't a willpower problem.

Estimated data suggests that while time-based and content-based controls are somewhat effective, they struggle against algorithmic influence, which is rated significantly lower.

The Publication Problem: What Happens When Research Stays Secret

Perhaps the most damning aspect of Project MYST isn't the research findings themselves. It's that Meta never published them.

In academic and corporate research contexts, publication serves specific functions. It subjects findings to peer review, allowing other researchers to scrutinize methodology and conclusions. It makes findings public, so organizations can act on them. It creates accountability: if a company knows something and doesn't act, the knowledge becomes public record.

Meta didn't publish Project MYST. No peer review. No public release. No guidance to parents. No adjustments to parental control features based on findings showing they don't work. Just internal knowledge sitting in documents that lawyers discovered through litigation.

This raises questions about research ethics. If a company conducts research showing that a product feature (parental controls) doesn't work as intended, does the company have an obligation to tell parents? If the research shows that vulnerable populations (traumatized teens) are more at risk of problematic use, does the company need to warn those populations or adjust the product?

Meta's position appears to be that Project MYST was an exploratory study exploring perception of use, not definitive proof of harm or feature inadequacy. The company might argue that all internal research shouldn't necessarily be published—some studies inform decision-making without reaching conclusions ready for public release.

But that argument weakens when the research suggests known harms (the lawsuit alleges Meta knew about Instagram's mental health effects) and when the company continues marketing features (parental controls) without disclosing that internal research suggests those features don't work.

Trial lawyers argue this is deliberately misleading. Instagram's website and promotional materials tout parental controls as tools that help parents supervise and limit their teens' use. If Meta knows from internal research that these controls don't prevent problematic use, promoting them without that caveat is arguably deceptive.

The non-publication also affects regulatory and policy discussions. Policymakers considering social media regulations, age restrictions, or parental control mandates might make different decisions if they knew that internal research showed parental controls don't prevent problematic use. The absence of public knowledge about Project MYST's findings shaped the policy landscape in ways that might not have happened otherwise.

Meta hasn't commented on why Project MYST wasn't published or what internal decisions resulted from the research. The company did suggest to Tech Crunch that it would welcome comment, but hasn't provided a statement explaining the research, its methodology, or why findings weren't released publicly.

Algorithmic Design and Engagement: The Real Driver of Compulsive Use

If parental controls don't work, the question becomes: what actually drives compulsive social media use? The answer, according to decades of research in behavioral psychology and neuroscience, centers on platform design itself.

Modern social media platforms aren't neutral distribution channels for user-generated content. They're optimization engines designed to maximize engagement. Every feature, from the infinite scroll to the notification badges, is tuned to keep users returning and scrolling for as long as possible.

The primary mechanism is the algorithmic feed. Rather than showing users chronological content from accounts they follow (which would eventually run out of new content), algorithms curate personalized feeds designed to maximize engagement. Machine learning systems learn what content keeps a particular user scrolling longest, then prioritize serving more similar content.

For teens dealing with insecurity, this creates a problem. If a teen is prone to compare their appearance to others, the algorithm learns this and serves more appearance-focused content. If a teen is struggling with anxiety and scrolling to escape, the algorithm learns this and serves more escapist content.

The result is that the algorithm becomes a feedback loop that amplifies the user's vulnerabilities. Instead of moderation, the teen experiences increasing exposure to content that triggers their vulnerabilities more intensely.

Variable ratio reinforcement amplifies this effect. Each scroll could reveal something amazing or something mediocre, and the user doesn't know which until they scroll. Research in behavioral psychology shows that this unpredictability is more powerful than consistent rewards in driving compulsive behavior—which is why slot machines work the way they do.

Notifications add another layer. When a teen closes the app, notifications remind them of activity—someone liked their post, someone started following them, a friend messaged. These notifications are timed and personalized to maximize the likelihood the teen will re-open the app.

Measuring and quantifying this infrastructure is difficult, but leaked Meta documents have shown the company understands its mechanisms. Facebook's own research found that Instagram is particularly harmful for teenage girls' body image and mental health. The company knew this and continued promoting the platform.

Parental controls can't address any of this. You can't restrict your teen to a chronological feed through parental controls. You can't disable the algorithm's personalization. You can't prevent the app from learning and amplifying your teen's vulnerabilities. You can set a time limit, but you can't change what happens during those limited sessions.

This is why Project MYST's findings about parental supervision are unsurprising from a design perspective. Parental controls operate at the usage level (how much time, when, with what content restrictions). They don't operate at the algorithmic level (what gets recommended and why).

It's roughly analogous to addressing obesity by restricting when someone can enter a restaurant, while the restaurant's layout, menu, portion sizes, and food formulations are all optimized for maximum calorie consumption. The restriction helps, but it doesn't address the underlying design.

For Meta to claim that parental controls prevent problematic use, the company would need to either change its algorithms to be less compelling or not deploy the algorithms at all. Those are commercial decisions the company has made in the opposite direction—algorithms are at the core of Meta's engagement optimization and advertising models.

Estimated data shows that family instability and bullying are the most common adverse experiences among teens, affecting their ability to regulate social media use.

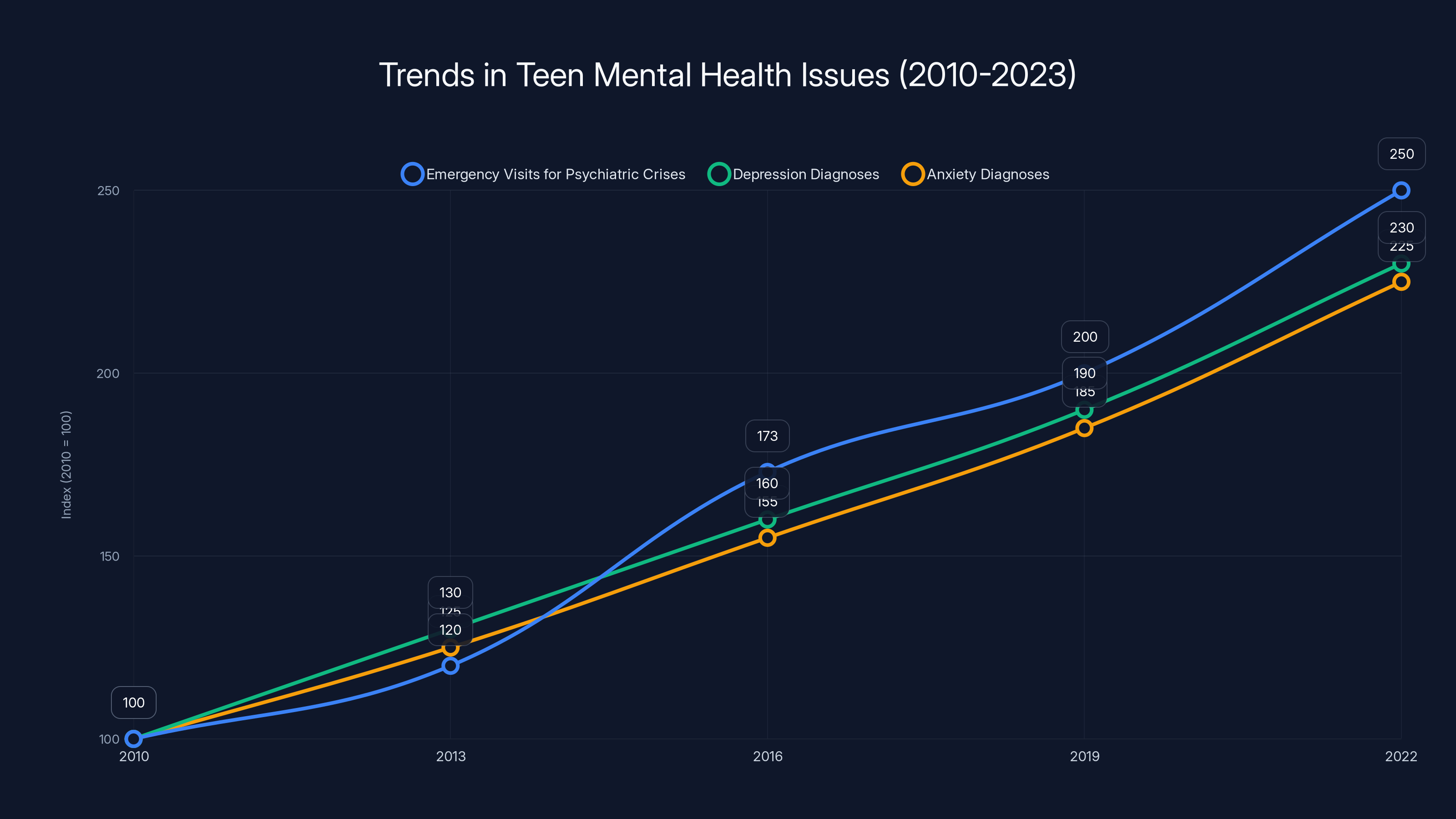

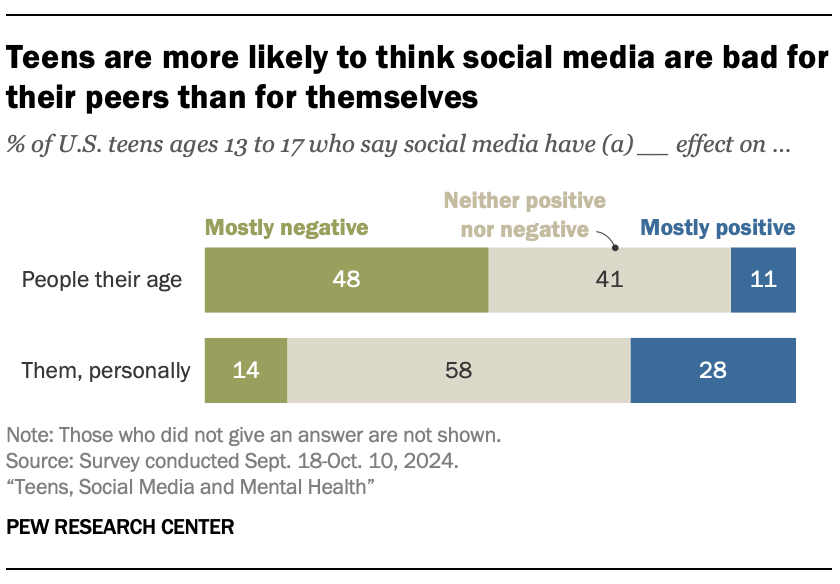

The Mental Health Crisis: What's Happening to Teenagers

Understanding Project MYST's findings requires context about the mental health landscape for teenagers in the 2020s.

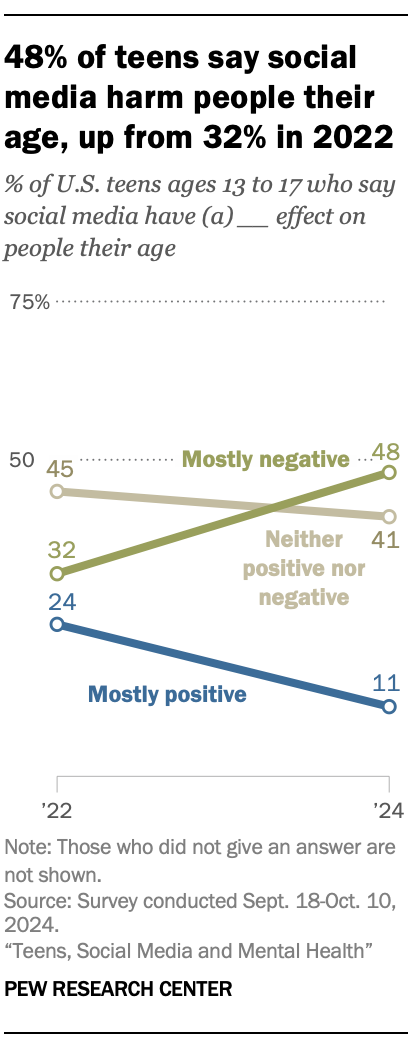

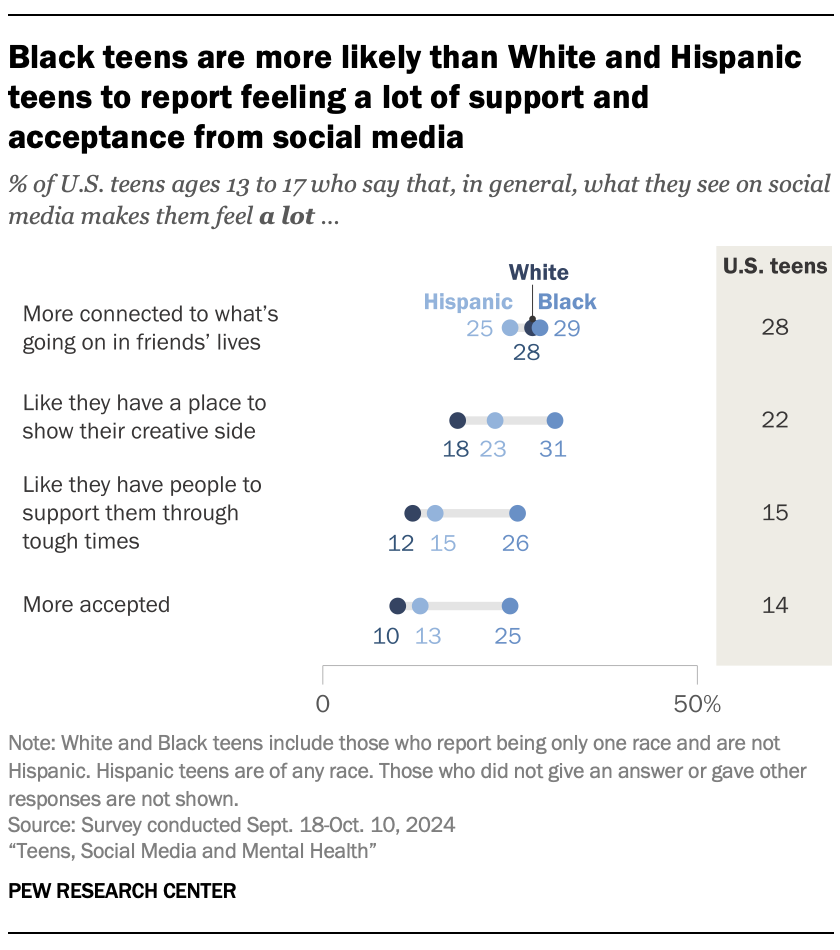

Teen mental health has deteriorated significantly in the past decade. Emergency department visits for psychiatric crises among adolescents increased 73% between 2016 and 2022, according to data presented at medical conferences. Suicide rates among teenagers have climbed. Depression and anxiety diagnoses have increased substantially, particularly among girls.

The timeline is notable. Social media adoption among teens accelerated dramatically in the early 2010s. Instagram launched in 2010 and reached 1 billion monthly active users by 2023. TikTok launched globally in 2018 and has become ubiquitous among Gen Z. The mental health crisis accelerated as social media usage intensified.

Correlation isn't causation, and the relationship between social media and teen mental health involves complex factors: pandemic isolation, economic anxiety, political polarization, academic pressure, family stress. Social media isn't the sole cause of the teen mental health crisis.

But the evidence suggesting social media significantly contributes is substantial. Longitudinal studies show that increased social media use is associated with higher rates of depression and anxiety. Users report feeling worse about their bodies, their social standing, and their life circumstances after scrolling. The comparison mechanism is powerful: seeing highlight reels from peers' lives (vacations, relationships, achievements) triggers feelings of inadequacy.

For teens already dealing with trauma or adverse life circumstances, social media compounds the problem. A teen experiencing parental abuse or bullying at school faces real-world distress. Social media offers an escape, but it also exposes that teen to comparison with peers who appear to have better lives. The algorithm, optimizing for engagement, learns the teen is vulnerable to certain types of content and serves more of it.

The research Meta conducted (and didn't publish) identified exactly this dynamic: teens with adverse life experiences were more vulnerable to problematic social media use. Rather than designing around this vulnerability, Meta's algorithms likely amplified it by optimizing for engagement with users who had identified vulnerabilities.

The public health implication is significant. If 50-60% of teens experience at least one ACE, and if ACEs reduce the ability to self-regulate social media use, then a substantial portion of the teenage population is vulnerable to problematic use regardless of parental intervention.

Public health approaches would typically address this vulnerability by either reducing exposure (limiting social media access for vulnerable populations) or reducing the intensity of the risk factor (designing social media to be less engaging or less psychologically intensive).

Meta has chosen neither approach. The company continues optimizing for engagement while arguing that parents should supervise use—an approach Project MYST's own research suggests doesn't work.

Why Meta Doesn't Want to Publish (And What That Suggests)

Meta's decision not to publish Project MYST raises questions about why the company wouldn't want the research public.

One possibility is that the research simply wasn't conclusive enough for publication. Academic journals have standards. The study would need to meet those standards to be published in peer-reviewed outlets. Perhaps Meta felt the methodology had limitations, the findings were preliminary, or additional research was needed.

Another possibility is that Meta conducts far more research than it publishes, and selection of what to publish involves editorial judgment. The company might publish findings that reflect well on the company or that advance research understanding, while keeping less favorable findings internal.

But trial lawyers suggest a third possibility: Meta didn't publish Project MYST because the findings could be used against the company in exactly this scenario. If the research shows that parental controls don't work, that findings stay internal knowledge rather than public knowledge, Meta can continue marketing parental controls as a solution without facing contradiction from its own research.

This interpretation, while speculative, aligns with how Meta has handled other research. The company conducted extensive research on Instagram's effects on teen girls' mental health and body image (documented in the "Facebook Papers") but didn't publicly release these findings initially. Investigators and journalists had to acquire the documents through leak or subpoena.

The company's general approach seems to be: conduct research on potential harms, keep findings internal, continue product development and marketing, and only disclose findings if forced to by legal process or public pressure.

This strategy works well for the company in the short term. It avoids public relations problems, regulatory scrutiny, and activist pressure. But it also means that millions of parents make decisions about their teenagers' technology use without access to the company's own research on whether those decisions actually work.

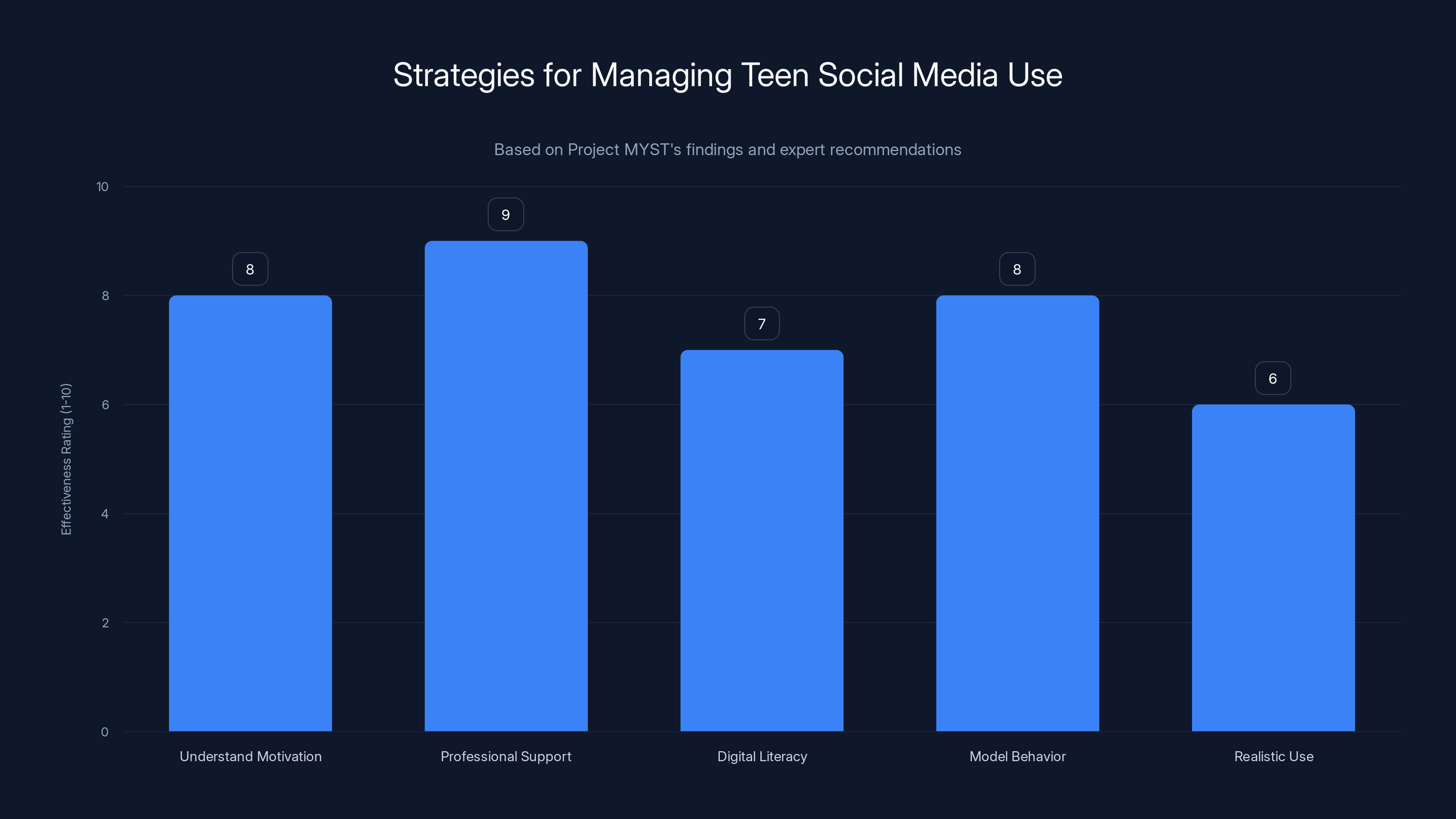

Understanding teens' motivations and providing mental health support are rated as the most effective strategies for managing social media use, according to expert recommendations. Estimated data.

The Legal Landscape: How This Trial Fits Into Broader Litigation

Kaley's case is part of a much larger legal landscape around social media and teen mental health.

Multiple lawsuits have been filed across the United States in 2024 and 2025 arguing that social media companies knowingly designed addictive products that harmed teenagers. These cases represent a potential turning point in how we regulate technology and assign responsibility for online harms.

The legal arguments in these cases follow a consistent pattern: companies knew or should have known their products would cause specific harms (anxiety, depression, body image issues, eating disorders, self-harm, suicide ideation). The companies designed products to maximize engagement despite knowing these harms would result. Parental oversight couldn't prevent the harms because the design was too sophisticated. Therefore, companies are liable for the damages to affected teenagers.

Project MYST becomes powerful evidence in these arguments because it represents Meta's own admission (via internal research) that one of the primary defenses—parental responsibility—doesn't actually work. If parents can't prevent harms through supervision, that responsibility shifts to the company and its design choices.

Other evidence in these cases includes leaked Meta documents showing knowledge of Instagram's effects on teen girls, internal Facebook discussions about the addictive properties of platform features, and testimony from product designers about deliberate engagement optimization.

The outcomes of these cases could reshape social media regulation and company liability. If courts find that companies designed addictive products knowing they would cause harm, damages could be substantial. More importantly for the long term, findings could prompt regulatory changes requiring companies to prioritize user wellbeing over engagement optimization, implement design changes reducing addictiveness, or display warning labels similar to those on cigarettes.

Even if initial cases face appeal or unfavorable rulings, the broader litigation trend is establishing legal precedent and public awareness. Future regulations, whether federal or state level, will likely reference these trials and the evidence presented in them.

Meta's Response Strategy: Deflection and Minimization

Meta's approach to the trial testimony and Project MYST has involved several strategies designed to minimize liability while maintaining plausible deniability.

Strategy One: Narrow Definitions Meta argues that Project MYST measured perceptions of attentiveness, not actual addiction. The distinction between "problematic use" and "addiction" allows Meta to acknowledge some teens use social media more than they want while denying that the product is addictive. This is a valid methodological distinction, but it feels like semantic gymnastics given the substance of the findings.

Strategy Two: Responsibility Shifting Meta argues that life circumstances, not platform design, drive problematic use. Kaley's case involved parental divorce, an abusive father, and bullying—all genuine stressors that contributed to her mental health challenges. By highlighting these external factors, Meta can argue that its product wasn't the primary harm, it was a secondary symptom of deeper problems.

This strategy contains truth. Life circumstances do matter tremendously for adolescent mental health. But it also ignores the mechanism: if social media serves as an escape mechanism that amplifies vulnerabilities and provides algorithmic reinforcement of psychological distress, then the platform isn't innocent even if it's not the sole cause.

Strategy Three: Capability Limitations Meta argues that companies can't possibly monitor or prevent all harms that users might experience from a product. The company can design features, but it can't prevent all negative outcomes in complex social contexts. This is technically true—no product is perfectly safe for all users in all contexts.

But the argument becomes weaker when the company has internal research showing specific harms and specific vulnerable populations, and the company doesn't disclose that research or adjust product design accordingly.

Strategy Four: Testimony Amnesia Mosseri's response that he couldn't remember Project MYST specifically is interesting. It suggests either that Meta runs so much research that executives don't follow all projects (possible but problematic if true), or that Mosseri was being evasive about something the company clearly knew about (more likely from a trial perspective).

This response, while probably effective in court, damages Meta's credibility. If the head of Instagram doesn't know about or remember a major internal research project on teen social media use, that raises questions about whether the company takes its research seriously or uses it to inform product decisions.

What Parents Should Actually Do: Beyond Failed Controls

Given that Project MYST's findings suggest parental controls don't prevent problematic social media use, what should parents actually do?

First, recognize that this isn't a parenting failure. If Meta's research is accurate, parents who set time limits, use parental control apps, and supervise their teens' social media use are doing what they've been told to do. If it doesn't work, that reflects the design sophistication of the platforms, not parental inadequacy.

Second, understand the underlying drivers of your teen's social media use. Is the use escapist? Is your teen using it to manage anxiety, depression, or social stress? Is your teen comparing themselves to peers and feeling inadequate? Understanding the motivation helps address it more effectively than controlling access.

Third, consider professional mental health support if your teen is dealing with trauma, anxiety, depression, or other challenges. The research suggests that teens with adverse life experiences are more vulnerable to problematic social media use. Addressing those experiences through therapy, counseling, or other mental health support might be more effective than controlling social media access.

Fourth, discuss the mechanics of social media with your teen. Explain how algorithms work, how engagement optimization operates, how notifications are timed to maximize re-engagement, and how comparison on social media differs from reality. Digital literacy might be more protective than parental controls.

Fifth, model healthy social media use yourself. Teens are more likely to follow what parents do than what parents say. If you're compulsively scrolling or using social media to escape boredom or stress, your teen will learn that behavior.

Sixth, be aware that cutting off social media entirely might not be realistic or healthy for your teen. Social media is where peers socialize, where information is shared, where communities organize. Complete abstinence isn't necessarily the goal—healthy regulation is.

Seventh, advocate for regulatory and design changes. Support legislation requiring social media companies to publish research on mental health impacts, implement design changes reducing addictiveness, restrict algorithmic optimization for younger users, or clearly label the addictive properties of features.

Regulatory Implications: What Happens Next

The outcomes of cases like Kaley's could significantly affect how social media is regulated in the United States and globally.

If courts rule that Meta and other companies knowingly designed addictive products that harmed teenagers, the regulatory landscape could shift dramatically. Here are potential outcomes.

Mandatory Disclosure Requirements Regulators might require companies to publish research on mental health impacts, usage patterns, and algorithmic effects. This would make internal research like Project MYST public automatically, preventing companies from sitting on unfavorable findings.

Design Restrictions Regulators might impose restrictions on algorithmic optimization, notification timing, or feature design for users under 18. Some proposals would require "chronological" feeds for younger users instead of algorithmic feeds, eliminating the variable reward scheduling that drives compulsive use.

Age Restrictions Similar to restrictions on alcohol or tobacco, regulators might impose minimum age requirements or require age verification for social media platforms. Some proposals would ban social media entirely for users under 16.

Liability Changes Courts might find that companies are liable for damages caused by their products, similar to tobacco litigation. This would create financial incentives for companies to reduce harmful features.

Duty to Warn Companies might be required to display warnings about addictive properties or mental health risks, similar to cigarette package warnings.

The European Union is already moving in some of these directions through the Digital Services Act, which imposes requirements on online platforms to protect minors, disclose algorithmic systems, and design responsibly.

The United States is slower to regulate technology, but litigation is often a precursor to regulation. As court cases establish liability and document company knowledge of harms, regulatory bodies gain political cover to implement restrictions.

The Broader Context: Big Tech and Accountability

Project MYST and the litigation it supports fit into a larger pattern of Big Tech companies conducting research on harms, keeping findings internal, and continuing harmful practices until forced to change through regulation or litigation.

Facebook knew from its own research that Instagram harmed teenage girls' body image and mental health. The company didn't change the platform or publicly disclose the research. Journalists and investigators had to force the issue.

Twitter and other platforms knew that their algorithmic recommendation systems amplified misinformation and extremism. The companies optimized for engagement anyway because extremist content drove engagement and advertising revenue.

TikTok knew that its algorithm was extraordinarily effective at capturing attention, particularly among younger users. The company continued optimizing despite concerns from researchers about dependency and mental health effects.

This pattern suggests a systemic issue with how technology companies approach research, particularly when findings are unfavorable. Companies have incentive structures that prioritize growth, engagement, and revenue over user wellbeing. When internal research identifies harms, the rational corporate response (in financial terms) is to suppress or minimize those findings while maintaining product development and marketing unchanged.

Project MYST is just one example of this broader pattern. The research itself is valuable evidence of what the company knew and when it knew it. The fact that it wasn't published is itself evidence of corporate priorities—engagement optimization matters more than public health protection.

Long-term change likely requires shifting those incentive structures through regulation, litigation, or consumer pressure. Until companies face consequences for harms, keeping research internal while harming users remains the rational business strategy.

Future Research: What We Still Need to Understand

While Project MYST provides valuable evidence about parental supervision's limitations, significant research questions remain.

Algorithmic Mechanisms We need detailed research on exactly how algorithmic feeds and engagement optimization drive compulsive use. This would require companies to open their algorithms to independent researchers—something they've resisted strongly.

Causality Questions Does social media cause mental health problems, or do people with mental health problems gravitate toward social media? Longitudinal research following teens before and after social media adoption could clarify causality. So far, most research is correlational.

Individual Differences Why do some teens develop problematic social media use while others don't? What individual, family, or environmental factors protect some teens while leaving others vulnerable? Understanding these differences could inform better interventions.

Effective Interventions If parental controls don't work, what does? What design changes would actually reduce problematic use? What mental health interventions help teens dealing with social media-related distress? These questions need systematic research.

Long-term Effects What are the long-term mental health and developmental consequences of growing up with addictive social media? Longitudinal studies following teenagers into adulthood could reveal effects that aren't apparent in shorter-term research.

Vulnerable Populations How do effects of social media differ across socioeconomic status, gender identity, race, disability status, and other demographic factors? Current research often focuses on predominantly white, educated populations.

Much of this research requires either access to company data (which they guard jealously) or independent researcher access to company systems (which they prevent). Until that changes, we'll continue working with incomplete information.

Nuance and Complexity: This Isn't Simple

Throughout this article, I've presented evidence suggesting that Meta knowingly designed products that harm teenagers and that parental supervision can't prevent those harms. That's the litigation narrative, and there's substantial evidence supporting it.

But it's worth acknowledging the genuine complexity here.

Social media isn't purely harmful. For many teenagers, particularly those who are marginalized or isolated, social media provides community, connection, and support they can't find locally. LGBTQ+ teens in conservative areas find community online. Teens with rare medical conditions connect with others who understand their experience. Teens with social anxiety can practice social connection in lower-stakes environments.

Mental health causality is genuinely complex. Teenagers today face unprecedented stressors: economic anxiety, climate change, political polarization, pandemic effects, academic pressure, student debt, housing crises. Social media is one factor among many affecting mental health, not the sole determinant.

Parental supervision and control have value even if they don't prevent problematic use entirely. They might reduce the severity, prevent some harms, encourage conversations about healthy use, or delay when problematic use develops.

Meta's claim that life circumstances matter more than platform design is partly correct. A teenager dealing with parental abuse, bullying, and poverty faces legitimate stressors that social media doesn't create. Addressing those circumstances would help regardless of social media presence.

What complicates this nuance is the question of corporate responsibility. Yes, social media's harms are multifactorial. But Meta has agency. The company can choose to optimize for engagement or for user wellbeing. It can choose to publish research or suppress it. It can choose to design for vulnerability or design with vulnerability in mind.

Meta has chosen engagement optimization, research suppression, and design sophistication over user protection. That choice, made knowingly based on internal research about consequences, is where liability lies.

Conclusion: What Project MYST Means for the Future

Meta's Project MYST research, revealed during testimony in a landmark social media addiction trial, fundamentally challenges how we think about teen social media use and who bears responsibility for harms.

The core findings are clear: parental supervision doesn't prevent problematic social media use, and teenagers with adverse life experiences are particularly vulnerable to compulsive use. These aren't surprising conclusions from a research perspective—they align with what psychologists and behavioral scientists would predict. But they matter enormously in a legal context because they undermine Meta's defense that responsibility lies with parents rather than the company.

If parents can't prevent problematic use through the mechanisms they've been told to use, responsibility shifts upstream to the company designing the platform and downstream to regulators who fail to restrict harmful design practices.

For parents, this research suggests that parental controls are better understood as oversight tools rather than prevention mechanisms. They might help maintain awareness of what teens are doing, but they won't prevent compulsive use driven by algorithms optimized for engagement. More effective approaches involve supporting teens' overall mental health, understanding the drivers of their social media use, and advocating for regulatory and design changes that reduce addictiveness at the platform level.

For regulators, Project MYST provides evidence that internal research on harms should be made public, that design changes are possible, and that companies know far more about their products' effects than they've disclosed publicly. This evidence could inform regulation requiring mandatory disclosure, design restrictions, and liability for known harms.

For Meta and other social media companies, the implications are significant. If courts find the company liable for designing addictive products knowing they would harm teenagers, damages could reshape company finances and incentives. Even if companies avoid major liability, the litigation creates political pressure for regulation that would fundamentally alter how social media is designed and marketed.

Beyond this specific case, Project MYST represents a larger pattern: large technology companies conduct research on harms, suppress unfavorable findings, and continue harmful practices until forced to change. Shifting this pattern requires some combination of regulation mandating disclosure, litigation establishing liability, and consumer pressure creating reputational consequences.

The teenage mental health crisis is real and multifactorial. Social media isn't the sole cause. But it's a significant contributor, particularly for vulnerable populations. Addressing it effectively requires companies to prioritize user wellbeing alongside engagement optimization, regulators to enforce restrictions on harmful design, and parents to work with broader support systems rather than relying on parental controls to solve a systemic problem.

Project MYST's findings suggest that none of those changes have happened yet. But the trial has put the evidence on record, and that creates momentum for change that was previously absent.

FAQ

What is Project MYST?

Project MYST is an internal Meta research study conducted in partnership with the University of Chicago examining the relationship between parental supervision and teen social media use. The study surveyed 1,000 teenagers and their parents about supervision, controls, and usage patterns. Findings showed that parental supervision had little association with whether teens engaged in compulsive or problematic social media use.

What were the main findings of Project MYST?

The study found two main results: first, parental supervision, time limits, and household rules had "little association" with teens' ability to self-regulate their social media use. Second, teens who experienced adverse life events (parental abuse, bullying, family instability, etc.) reported less attentiveness to their own social media use and higher likelihood of compulsive engagement. Both parents and teens agreed on these patterns in their survey responses.

Why did Meta not publish Project MYST?

Meta has not publicly explained why Project MYST wasn't published. The company hasn't commented on the research or its findings. The research emerged publicly only through legal discovery during the social media addiction trial. Some possibilities include that Meta considered the research preliminary, that internal editorial judgment determined it wasn't suitable for publication, or that the company deliberately suppressed findings that contradicted its marketing of parental controls.

Does this mean parental controls are completely useless?

Not entirely. Parental controls can still provide oversight, help parents understand what their teens are doing, facilitate conversations about healthy use, and potentially delay when problematic use develops. However, Project MYST suggests they don't prevent compulsive use driven by algorithmic optimization and platform design. They're better understood as oversight tools rather than prevention mechanisms for social media addiction.

What are adverse life experiences and why do they matter for social media use?

Adverse life experiences (also called ACEs) include traumatic events like parental substance abuse, abuse or neglect, bullying, parental divorce, domestic violence, and other significant stressors. Project MYST found that teens with more ACEs reported less ability to self-regulate their social media use, suggesting they were more vulnerable to compulsive engagement. This likely occurs because stress reduces the brain's capacity for self-regulation and because social media serves as an escape mechanism for dealing with difficult emotions.

How does this research affect social media liability and regulation?

Project MYST is being used as evidence in social media addiction lawsuits to argue that Meta knew parental controls don't prevent harm and that responsibility belongs with the company, not parents. If courts find Meta liable, it could establish precedent for regulatory changes requiring mandatory disclosure of research, design restrictions on engagement optimization, and potential liability for known harms. The research also informs potential regulation in the European Union and other jurisdictions.

What should parents do if parental controls don't prevent problematic use?

Experts suggest focusing on understanding the drivers of your teen's social media use rather than restricting access alone. Discuss why they use social media, what they enjoy, what makes them uncomfortable, and when they feel compelled to check their phones. Support their overall mental health through professional help if needed. Model healthy social media use yourself. Discuss how algorithms work and how social media differs from reality. Advocate for design and regulatory changes that reduce addictiveness at the platform level.

Is social media addiction an officially recognized diagnosis?

The DSM-5 (psychiatry's diagnostic manual) does not yet officially recognize "social media addiction," though "Internet Gaming Disorder" is being studied for inclusion. However, social media use patterns can meet clinical criteria for addiction including compulsive engagement despite negative consequences, tolerance, withdrawal symptoms, and unsuccessful attempts to control use. Meta uses the term "problematic use" rather than "addiction," a distinction that matters in legal settings but not necessarily clinically.

How does algorithmic optimization drive compulsive use in ways parental controls can't address?

Algorithmic feeds use machine learning to determine what content will keep each user scrolling longest. For vulnerable users, this can mean the algorithm learns and amplifies content that triggers anxiety, comparison, or other psychological vulnerabilities. Variable ratio reinforcement—where rewards (engaging content) are delivered unpredictably—creates strong behavioral conditioning. Notifications are timed to maximize re-engagement. Parental controls can limit time spent on the app but can't change what the algorithm recommends during those limited sessions, can't disable notifications, or can't reduce the psychological intensity of algorithmic feed engagement.

What does this trial mean for the future of social media and teen mental health?

The trial establishes legal precedent around company liability for addictive product design and creates evidence of company knowledge of harms. If Meta faces significant liability, it could reshape industry incentives toward prioritizing user wellbeing over engagement optimization. The trial also informs regulatory discussions, providing evidence for potential mandates requiring research disclosure, design changes, age restrictions, or addiction warning labels. Even without major liability findings, the litigation establishes public awareness that companies know about these harms and have internal research documenting them.

Key Takeaways

- Meta's Project MYST research found parental supervision and time limits had little association with preventing teen compulsive social media use

- Teenagers with adverse life experiences were significantly more vulnerable to problematic use regardless of parental oversight

- Meta never published the research publicly or issued warnings despite findings documenting known harms

- Algorithmic optimization and variable reward scheduling operate at a level that parental controls cannot address

- The trial evidence shifts responsibility from parents to platform design choices and company accountability

Related Articles

- Meta and YouTube Addiction Lawsuit: What's at Stake [2025]

- Meta's Fight Against Social Media Addiction Claims in Court [2025]

- Social Media Safety Ratings System: Meta, TikTok, Snap Guide [2025]

- Meta's Child Safety Trial: What the New Mexico Case Means [2025]

- EU's TikTok 'Addictive Design' Case: What It Means for Social Media [2025]

- Good Luck, Have Fun, Don't Die: AI Addiction & Tech Society [2025]

![Meta's Parental Supervision Study: What Research Shows About Teen Social Media Addiction [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/meta-s-parental-supervision-study-what-research-shows-about-/image-1-1771362698396.jpg)