Introduction: When Insiders Become the Threat

Peter Williams had everything most people dream about. A senior executive at Trenchant, a division of L3 Harris—one of America's largest defense contractors—he held a position of immense trust. His company sold surveillance and hacking tools to the U.S. government and its closest allies. The work was classified. The access was restricted. The responsibility was absolute.

Then he threw it all away for cryptocurrency.

In October 2025, Williams pleaded guilty to one of the most damaging cybersecurity breaches in recent memory. Between 2022 and 2025, the Australian national stole and sold eight zero-day exploits—software vulnerabilities unknown to manufacturers—to a Russian broker. The catch? These exploits could potentially access millions of computers and devices globally, including U.S. infrastructure. Williams made more than $1.3 million in crypto from the sales. The Justice Department is now asking for nine years in prison.

This isn't a story about a lone hacker operating from a basement in Eastern Europe. This is about systemic failure at the highest levels of American defense contracting. It's about how someone with legitimate access to weapons-grade hacking tools can walk out the door with them tucked under their arm. And it's about how that same person can continue selling those tools to foreign governments while the FBI watches, waiting for the perfect moment to strike.

The Williams case represents a watershed moment for cybersecurity and national security. It exposes vulnerabilities in how we protect sensitive technology, how we vet employees, and how we respond when insiders betray the system. The implications ripple far beyond Trenchant. Every defense contractor, intelligence agency, and government office now faces hard questions about their own security posture.

Let's break down what happened, why it matters, and what it means for the future of cybersecurity oversight.

Who Is Peter Williams and Why Did His Position Matter?

Peter Williams, 39, was Trenchant's general manager. That title might not mean much to people outside the defense industry, but inside Trenchant, it meant he oversaw operations for a company that created some of America's most sensitive hacking and surveillance tools.

Triple-letter agencies—the FBI, CIA, NSA—rely on companies like Trenchant to develop offensive cyber capabilities. These aren't tools you buy off the shelf. They're custom-built, classified, and represent millions of dollars in research and development. The people who work there undergo extensive background checks. They sign non-disclosure agreements. They attend security briefings about threats both foreign and domestic.

Williams had that clearance. He had that access. And according to prosecutors, he understood exactly what he was doing when he decided to steal.

The fact that Trenchant is owned by L3 Harris matters too. L3 Harris is a titan in the defense contracting space, with revenues exceeding $18 billion annually. The company builds everything from military communications systems to intelligence analysis platforms. When something goes wrong at an L3 Harris subsidiary, it reflects on the entire enterprise. It raises questions about how mega-contractors oversee their divisions. It forces audits and investigations that cost millions.

Williams' position also gave him something crucial: plausible deniability. He could access the exploits without anyone questioning it. He could attend meetings about security vulnerabilities. He could review code and tools. He had legitimate reasons to have these materials on his computer. When he started exfiltrating them, the internal alarms that might have caught a junior developer took longer to trip.

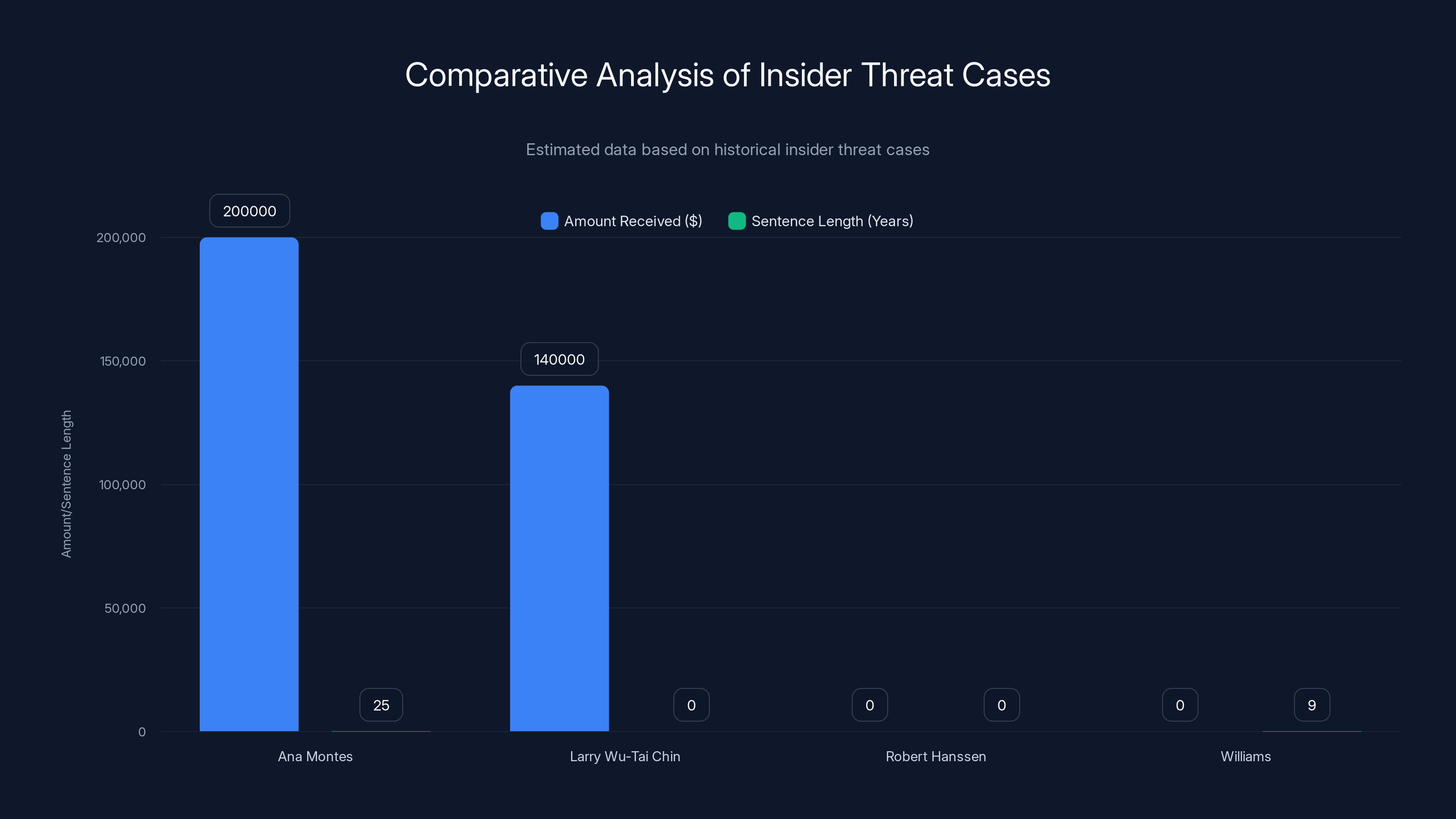

Zero-day exploits can range in value from thousands to hundreds of thousands of dollars, with critical scope exploits fetching the highest prices. (Estimated data)

The Eight Exploits: What Exactly Did Williams Sell?

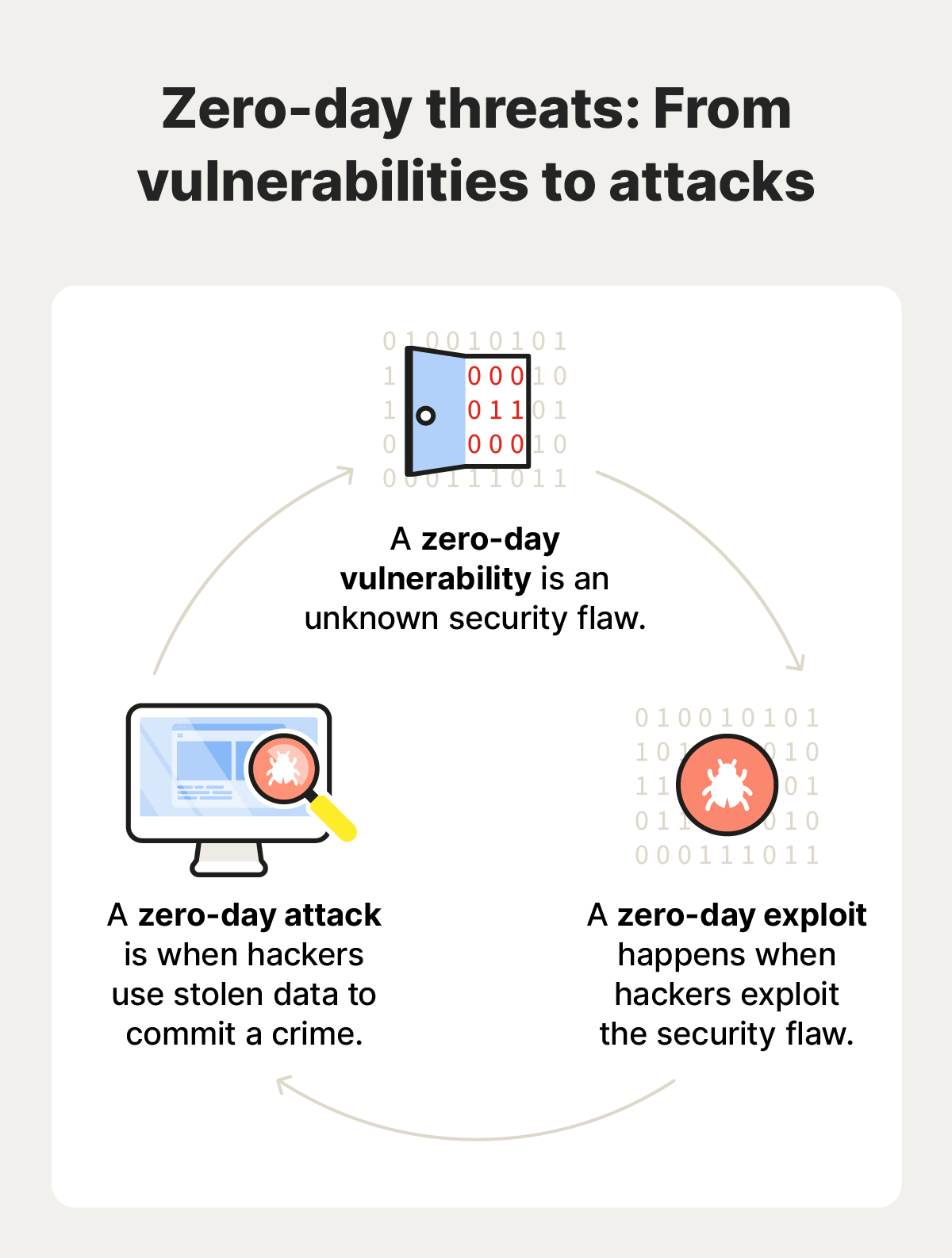

The term "zero-day" gets thrown around in tech circles, but it deserves explanation. A zero-day is a software vulnerability that the software maker doesn't know about. The "zero" refers to the number of days the vendor has had to develop a patch. These vulnerabilities are valuable—sometimes worth hundreds of thousands of dollars on the dark web.

Williams didn't sell just one. He sold eight.

Prosecutors describe these exploits as capable of enabling "indiscriminate government surveillance, cybercrime, and ransomware attacks across the globe." That's not hyperbole. These aren't tools that hack a specific person's laptop. These are broad-spectrum weapons that can compromise millions of devices simultaneously.

Think of it this way: if a zero-day affects a common piece of software—say, Windows or iOS—then anyone who controls that zero-day can potentially hack anyone running that software. If you're a criminal gang, you use it for ransomware. If you're a nation-state, you use it for espionage. If you're a weapons dealer selling to the highest bidder, you use it for all three.

The Justice Department's sentencing memorandum specifically states that the exploits Williams sold could have allowed the Russian broker and its customers to "potentially access millions of computers and devices around the world, including in the United States." That's not a theoretical threat. That's a quantifiable, catastrophic risk.

We don't know the exact technical details of each exploit—they're still classified. But the scope tells us what we need to know. Eight separate vulnerabilities across multiple software systems, all now in the hands of foreign adversaries.

What makes this worse is the timing. Williams didn't just steal and sell these exploits years ago, when he might claim he didn't understand the consequences. He did it while actively aware that the FBI was investigating him. Prosecutors documented that FBI agents were in contact with Williams from late 2024 until his arrest in mid-2025. And yet he continued selling. That suggests either arrogance, desperation, or a fundamental misunderstanding of how close law enforcement was.

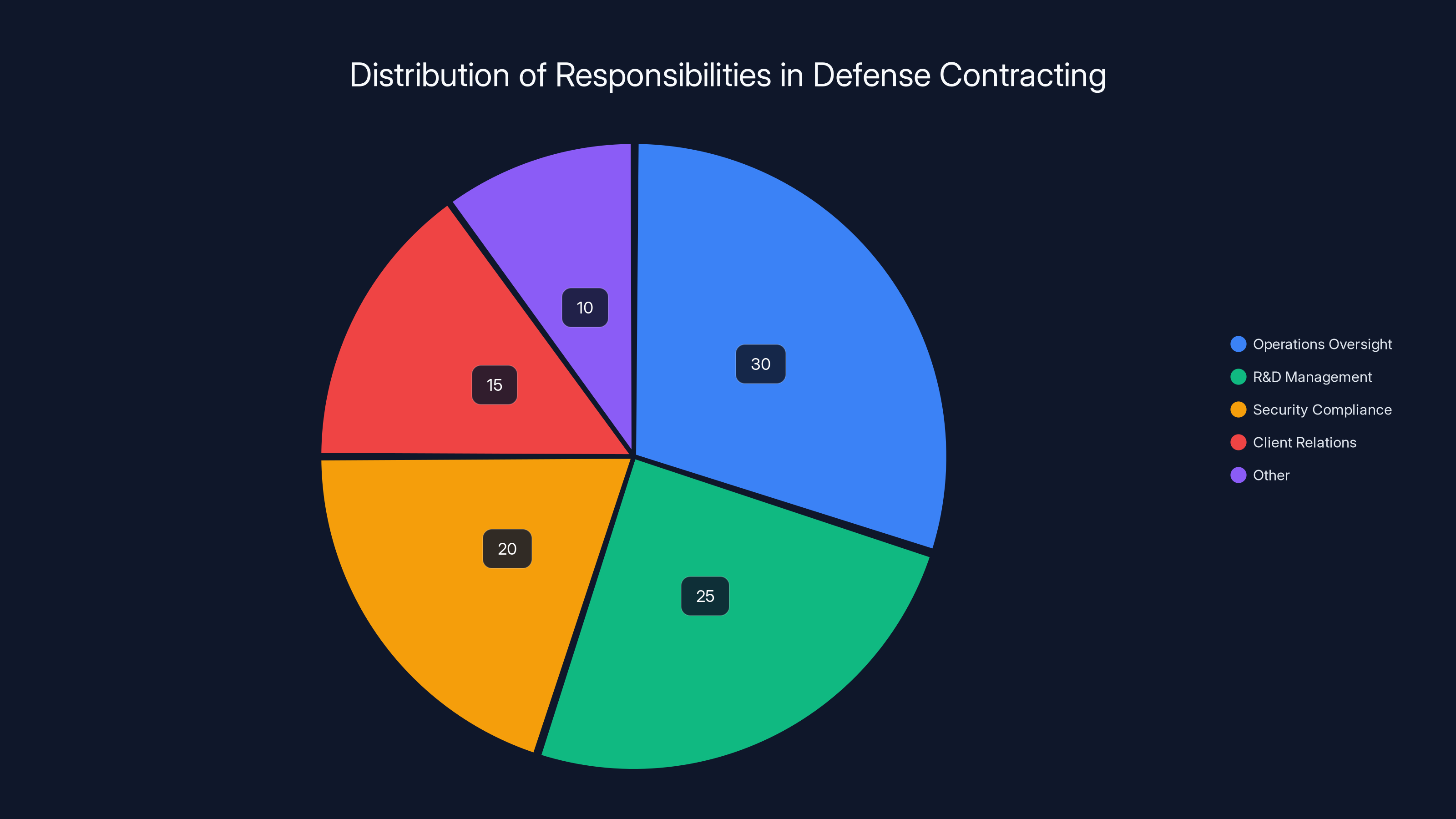

Estimated data showing the distribution of responsibilities in a defense contracting company. Operations oversight and R&D management are key roles.

The Russian Broker: Who Bought the Exploits?

Williams didn't sell directly to the Russian government. That would have been too obvious, too easily traced. Instead, he sold to a Russian broker—a middleman whose job was to acquire sensitive cyber tools and sell them to the highest bidder.

According to prosecutors, this Russian broker "counts the Russian government among its customers." That's the actual language from the sentencing memorandum. It's careful wording that acknowledges the Russian state was likely buying, but perhaps not exclusively. The broker probably also sold to Russian criminal organizations, Chinese intelligence, Iranian hacking groups, and anyone else with cryptocurrency and an interest in offensive cyber capabilities.

That's how the underground cyber marketplace works. Brokers operate like arms dealers, but instead of guns, they traffic in vulnerabilities and exploits. They maintain relationships with both sellers—people like Williams who have legitimate access to classified tools—and buyers, who range from organized crime to foreign governments.

The Russian connection isn't accidental either. Russia has a long history of cyber espionage and cyber warfare. The country hosts some of the world's most sophisticated criminal hacking groups, many of which operate with tacit government approval. Russia has the infrastructure, the expertise, and the motivation to use these exploits.

But here's the thing that should concern everyone: we don't actually know what the Russian government did with these exploits. Did they use them immediately? Are they still using them? Have they already compromised critical infrastructure? These questions remain unanswered, and they're unlikely to get answered during Williams' trial or sentencing.

What we do know is that the moment these exploits left Trenchant, they became a force multiplier for every entity that could afford to buy them. That's the real damage. It's not just about what the Russian government might do. It's about the cascading effect through the entire global cyber-criminal and cyber-espionage ecosystem.

The Money Trail: How Williams Got Caught

Williams made more than

But cryptocurrency leaves traces. Unlike cash, which can disappear into the financial system with relative anonymity, crypto transactions are permanently recorded on the blockchain. The addresses change, the intermediaries multiply, but the transactions are eternal.

FBI investigators likely started by analyzing the cryptocurrency movements. Which addresses received payments? Where did those addresses send the funds? What pattern emerges when you map out the connections? Investigators also probably worked backward from the Russian broker side. They identified who was likely selling exploits, matched payment patterns to known criminal actors, and then started narrowing the list of potential sellers.

Williams wasn't trying particularly hard to hide. He was communicating with the Russian broker, receiving cryptocurrency payments, and continuing with his job at Trenchant as if nothing was happening. In many ways, that's the scary part. It suggests he believed he wouldn't get caught, or that the upside of $1.3 million outweighed the risk of federal charges.

The FBI's patience in this case is instructive. Rather than arresting Williams immediately when they figured out what was happening, they kept him under surveillance. They maintained contact with him. They watched as he continued to sell exploits even after he knew law enforcement was investigating. This isn't an accident. This is a tactic designed to build the strongest possible case.

Every additional exploit Williams sold after the FBI made contact was additional evidence of intent. Every cryptocurrency transaction provided another data point. Every email or message provided more material for prosecution. By the time they arrested him in mid-2025, the case was airtight.

Williams consistently earned approximately

The Scapegoat: An Employee Blamed for Someone Else's Crime

Here's where the Williams case gets truly damning. While he was selling exploits to Russian brokers, another Trenchant employee was fired for allegedly leaking those same exploits.

According to sources and confirmed by prosecutors, Williams oversaw this firing. He sat in meetings as the company investigated the theft. He watched as blame fell on his subordinate. He said nothing. He did nothing. He just continued stealing and selling while his employee took the fall.

That fired employee later received notification from Apple that he had been targeted with government spyware. That notification still hasn't been explained. But the implication is clear: someone was interested enough in this employee to deploy nation-state-level surveillance tools against him.

Williams' lawyer tried to minimize this, arguing that there was no evidence Williams intended to harm the U.S. or Australia. But prosecutors didn't buy it. They noted in their sentencing memorandum that Williams "stood idly by while another employee of the company was essentially blamed for the Defendant's own conduct. He looked on while an internal corporate investigation falsely cast blame on his subordinate."

That's not a minor detail. That's evidence of character and intent. That's a defense contractor executive not just committing a crime, but actively letting someone else be punished for it.

The question now is whether Trenchant has made things right with that fired employee. Has the company apologized? Has it rehired him? Has it compensated him? These are questions Trenchant hasn't answered publicly. A spokesperson for the company declined to comment when asked about the case.

L3 Harris and Trenchant: What Went Wrong?

L3 Harris is one of America's largest defense contractors. The company has relationships with every major government agency. It handles classified work. It manages billions of dollars in contracts. And yet, a general manager at one of its subsidiaries was able to steal and sell some of the company's most sensitive tools for years.

How does that happen?

The most likely answer is that security measures at Trenchant were insufficient for the level of trust placed in employees like Williams. This doesn't mean Trenchant had no security. It means the security that existed had gaps. And Williams, as a general manager, likely had the knowledge and access to exploit those gaps.

Classic defense contractor security involves:

- Physical security (badge access, cameras, restricted areas)

- Information security (encrypted networks, access logs, data loss prevention)

- Personnel security (background checks, security clearances, continuous vetting)

- Operational security (need-to-know principles, segregation of duties)

The fact that Williams was able to exfiltrate eight separate exploits suggests that at least one of these categories failed. Maybe the data loss prevention tools weren't sophisticated enough. Maybe the access logs weren't being monitored in real-time. Maybe the principle of need-to-know was applied loosely to senior executives.

L3 Harris will likely face fallout from this case. Government auditors may review contracts. The company might lose security clearances at the subsidiary level. Defense agencies might impose new vetting requirements. The reputational damage is already considerable.

But here's the deeper issue: this problem isn't unique to Trenchant. Every defense contractor has senior executives with significant access to sensitive technology. Every company believes its security is sufficient. And every company probably has gaps that a determined insider could exploit.

Williams didn't need to be a genius hacker. He just needed to be a general manager who understood how to exfiltrate files without triggering alarms. The fact that he was able to do this, repeatedly, for years, while the company's security and investigation teams failed to catch him, suggests a systemic problem across the industry.

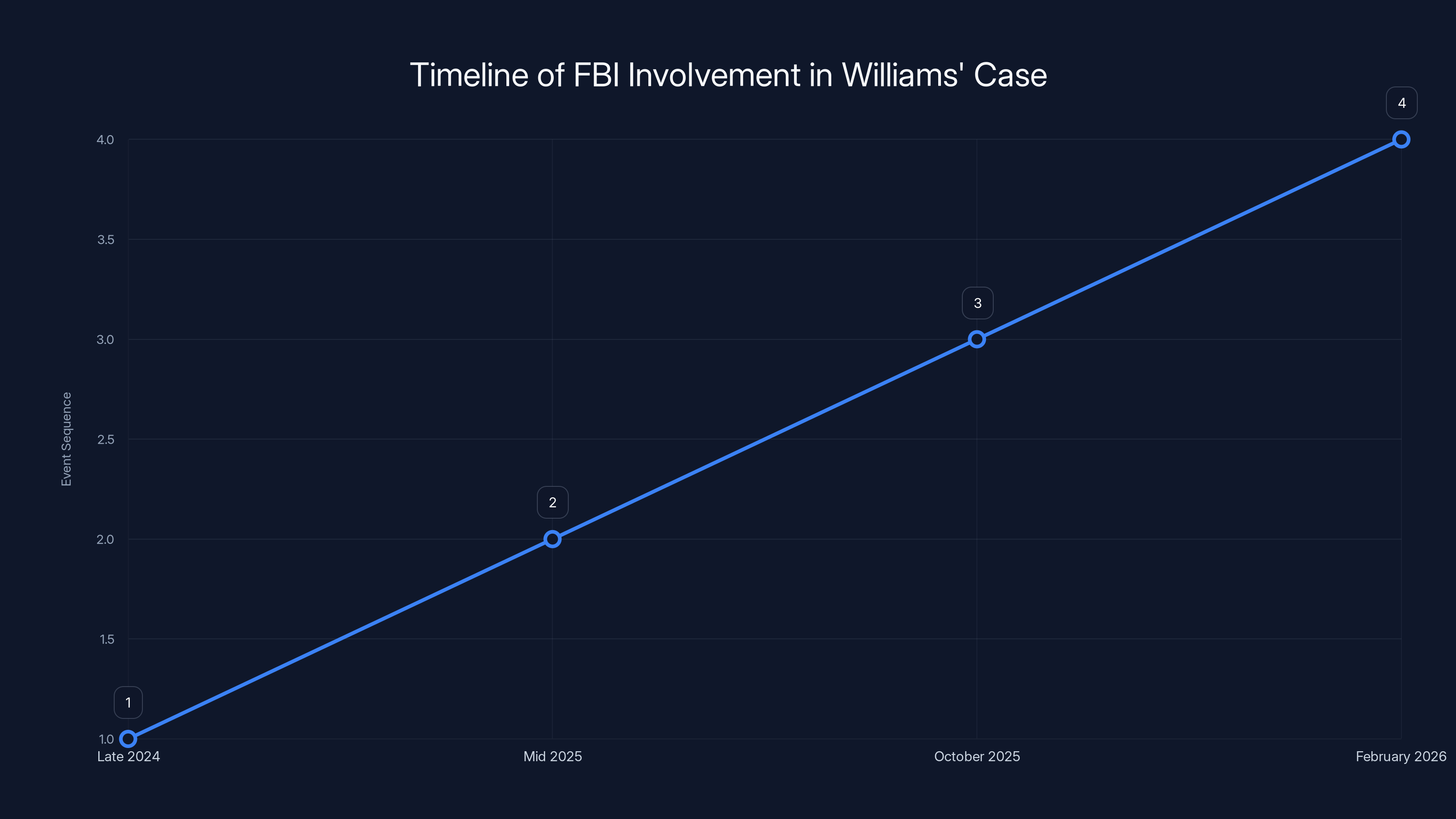

The timeline shows the progression of the FBI's involvement, from initial contact in late 2024 to the sentencing recommendation in February 2026.

The Cryptocurrency Connection: Tracing Digital Payment Trails

Cryptocurrency plays a critical role in this story, and it's worth understanding why. For decades, the standard way to catch criminals receiving illegal payments was to follow the money. Bank transfers leave records. Wire instructions are logged. Checks can be traced. But cryptocurrency bypasses many of these traditional controls.

Williams received payments in cryptocurrency. The Russian broker paid him in crypto. This made it harder to trace through traditional banking channels. However, it created a different kind of trail—the blockchain.

Every cryptocurrency transaction is permanently recorded on a public ledger. Anyone can see the transaction. The problem is that cryptocurrency addresses don't have names attached. An address is just a long string of characters. But if you can connect that address to a person, you can see every transaction that address has ever made.

Investigators likely used a combination of techniques to connect Williams' cryptocurrency addresses to him. They might have looked at:

- How he converted cryptocurrency to fiat currency (U.S. dollars, euros, etc.)

- Which exchanges he used for conversions

- The timing of transactions and when they coincided with his access to Trenchant systems

- Communication records where he discussed cryptocurrency payments

- Device analysis that showed blockchain access from devices he controlled

Once investigators established the connection, building the financial crime case became straightforward. Williams received $1.3 million in cryptocurrency for selling classified exploits. That's wire fraud, money laundering, espionage, and multiple other federal crimes.

The Justice Department is asking for restitution of $35 million. That's roughly 27 times what Williams actually received. The restitution is designed to account for the damage done to national security, the cost of investigating the breach, and the cost of counterintelligence work needed to assess what the Russian government knows.

For context,

Timing and Intent: When the FBI Got Involved

The timeline matters because it tells us how the investigation unfolded and what investigators believed.

FBI agents made contact with Williams in late 2024. At this point, they likely had enough evidence to know he was selling exploits, but not enough to arrest him. The goal was to gather more evidence while keeping him under observation.

Williams continued selling exploits even after making contact with the FBI. This is crucial. It demonstrates that he understood he was under investigation and chose to continue anyway. It shows intent, arrogance, or desperation.

Williams was arrested in mid-2025. The Justice Department built their case over several months, gathering evidence of the cryptocurrency payments, the exploits he sold, the communications with the Russian broker, and the internal investigation he mishandled.

In October 2025, Williams pleaded guilty. This suggests prosecutors had a case strong enough that going to trial would be pointless from Williams' perspective. Better to take the plea deal and minimize the sentence.

Now, in February 2026, Williams faces sentencing. The Justice Department is recommending nine years in prison, three years of supervised release,

The judge will decide which argument is more persuasive. Nine years is a serious sentence, but for selling defense contractor secrets to foreign governments, it's not excessive.

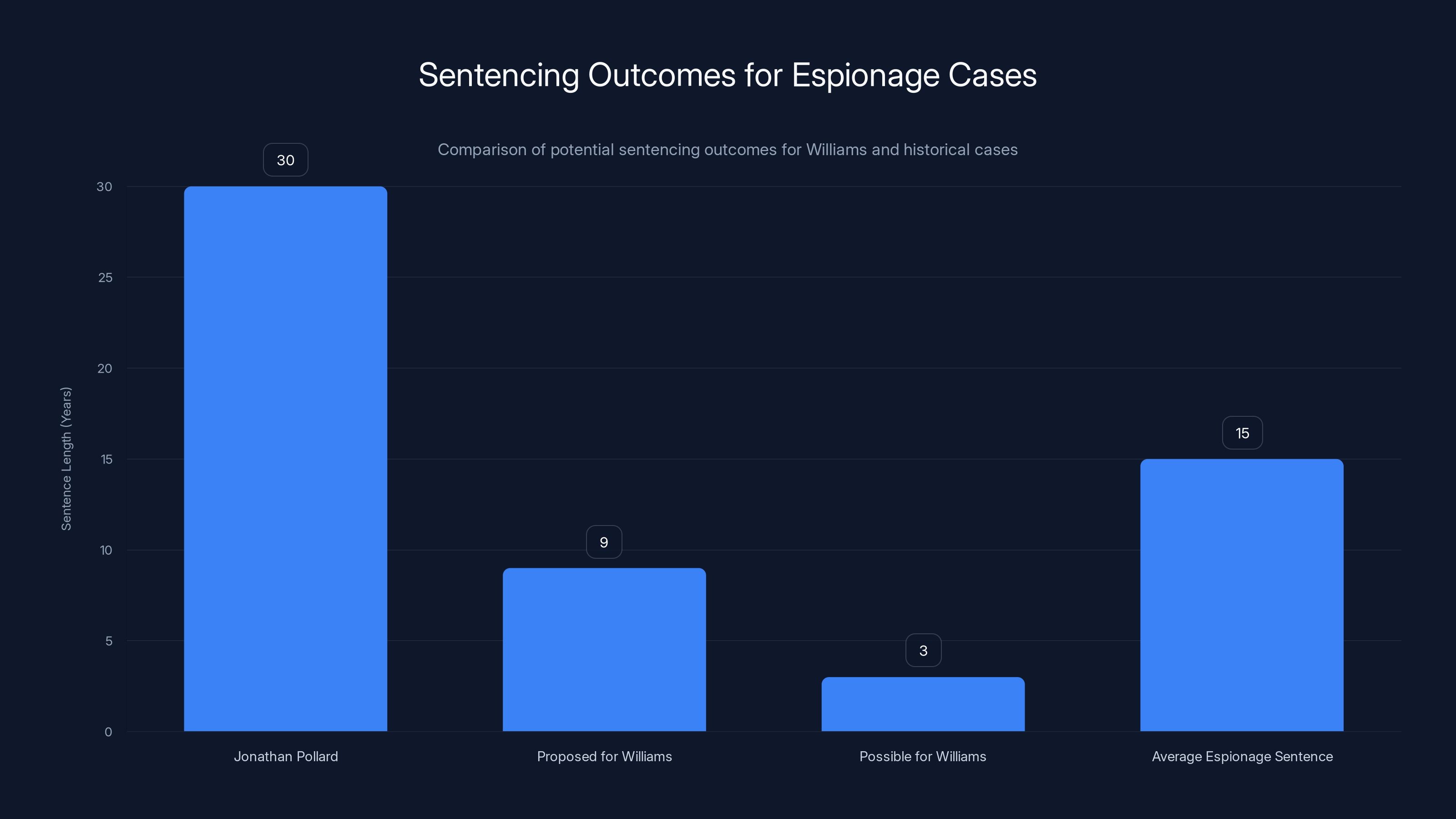

Williams' proposed nine-year sentence is significant but less than Pollard's 30 years. It could set a precedent for future espionage cases. Estimated data for average espionage sentence.

The Implications for Defense Contracting and National Security

This case forces a reckoning with how we protect sensitive defense technology. Here are the major implications:

Insider threat detection needs improvement. If Trenchant's security systems had been more sophisticated, they might have flagged Williams' exfiltration attempts earlier. Modern data loss prevention tools can detect when large numbers of files are accessed simultaneously or when classified materials are copied to external devices. The fact that Williams was able to steal eight separate exploits suggests these tools either weren't deployed or weren't monitored.

Clearance vetting is only as good as the polygraph. The standard polygraph test given to cleared employees includes questions about contact with foreign nationals, financial difficulties, and suspicious activity. Williams presumably passed these tests multiple times, yet he was actively selling secrets to Russian brokers. This raises questions about the effectiveness of polygraph testing as a security measure.

Senior executives have too much unfettered access. In traditional information security, the principle of least privilege means people only have access to what they need for their jobs. But senior executives often get broad access because the company trusts them and because restricting that access would be cumbersome. Williams' position as general manager probably gave him access to more systems and more data than a junior developer would have. That access enabled the theft.

Criminal networks are sophisticated at recruiting insiders. The Russian broker didn't just stumble upon Peter Williams. At some point, someone in the criminal ecosystem made contact with him, offered money for classified exploits, and facilitated the transactions. That recruitment process, and how it happened, remains unclear. But it suggests that foreign adversaries have sophisticated insider recruitment operations targeting U.S. defense contractors.

The investigation and prosecution model worked. This is the one positive note. The FBI and Justice Department identified Williams, investigated him carefully, built an airtight case, and are now seeking serious prison time. That's the system working as intended, even if it took longer than ideal.

These implications will ripple through the defense contracting industry. Companies will likely increase insider threat monitoring. Agencies like the Defense Counterintelligence and Security Agency will probably issue new guidelines. Contracts might include new requirements for data loss prevention and access controls.

What This Means for Cybersecurity Professionals and Organizations

For cybersecurity practitioners, the Williams case offers several lessons:

First, insiders are a persistent threat. No amount of external security can compensate for an employee who decides to commit espionage. The most sophisticated attack you'll face might come from someone with legitimate access and a need for money. This means insider threat programs, suspicious activity monitoring, and careful vetting of access privileges need to be treated as seriously as external security.

Second, detection requires multiple layers. Investigators caught Williams by analyzing cryptocurrency transactions, monitoring his communications with the Russian broker, and observing his continued access to Trenchant systems. No single layer would have caught him. A comprehensive approach to insider threat detection involves behavioral analysis, financial monitoring, and technical controls.

Third, cryptocurrency makes financial crimes easier to hide initially but harder to hide permanently. Williams thought paying in crypto would make him harder to track. To a point, it did. But cryptocurrency transactions are permanent and verifiable, which means patient investigators can follow the trail. For organizations, this means understanding that cryptocurrency payments for illegal activity might actually create a better audit trail than traditional banking.

Fourth, scapegoating creates legal and ethical liability. The fact that Williams allowed another employee to be fired for his crimes probably influenced his sentencing. The judge and prosecutors will see this as particularly egregious behavior. For organizations, this means internal investigations need to be careful and thorough, not quick and convenient.

Estimated data shows that while Williams received no direct payment, his recommended sentence aligns with historical cases where significant sentences were given for espionage.

The Defense Contractor Industry's Response and Future Outlook

L3 Harris and other defense contractors will now face pressure to strengthen their security posture. This likely means:

Increased investment in data loss prevention. Tools that detect when sensitive files are accessed or copied will become standard. This includes tools that prevent copying to external drives, USB devices, or cloud services.

More aggressive insider threat monitoring. This is a controversial area because it involves surveilling employees. But defense contractors will likely implement tools that monitor for suspicious access patterns, unusual file access, and anomalous behavior.

Revised clearance vetting procedures. The polygraph might be supplemented with more sophisticated psychological assessment or continuous monitoring of cleared employees.

Stricter separation of duties. The principle that no single person should have access to all critical systems will be reinforced. Even senior executives will face access restrictions.

Enhanced financial monitoring. Companies might implement requirements for cleared employees to disclose cryptocurrency holdings or unusual financial activity.

These measures will increase costs and complexity. They'll also make the environment more restrictive for employees. But the alternative—allowing more Peter Williams to operate undetected—is worse.

From a national security perspective, this case highlights the vulnerability of the American defense industrial base. The U.S. relies on contractors to develop and maintain offensive cyber capabilities. If those capabilities leak to foreign governments, the strategic advantage erodes. It's a problem with no easy solution, but it's a problem that now has everyone's attention.

Expert Insights and Industry Commentary

Cybersecurity experts have weighed in on what the Williams case means for the broader industry. Common themes include:

The danger of trusted insiders. Security experts emphasize that Williams wasn't a low-level employee or a junior developer. He was a general manager, someone the company had vetted extensively and placed in a position of significant responsibility. This reinforces the uncomfortable truth that vetting, no matter how thorough, isn't foolproof.

The role of motivation and opportunity. Criminologists and security professionals often discuss the fraud triangle: motivation, opportunity, and rationalization. Williams had all three. He had motivation (wanting more money). He had opportunity (legitimate access to classified tools). And he had rationalization (convincing himself that selling to a Russian broker wasn't really harming anyone, or that he could retire before getting caught).

The sophistication of intelligence recruitment. Some analysts have noted that Russian intelligence is sophisticated at identifying and approaching potential recruits. They might have identified Williams as a target months or years before first contact. They might have used intermediaries, cryptocurrency advocates, or other cover stories to build a relationship with him before the actual recruitment pitch.

The role of greed. Perhaps the most cynical but honest commentary is that $1.3 million in cryptocurrency was enough to override Williams' training, clearance requirements, and ethical obligations. He looked at the opportunity and said yes. That's not a systems failure. That's a human failure.

What Comes Next: Sentencing and Precedent

Williams' sentencing is scheduled for February 24, 2026. The Justice Department will argue for nine years. His lawyer will argue for less. The judge will consider both positions and issue a sentence.

Nine years is significant. It's long enough to remove Williams from the labor market for a decade. It's long enough to send a message to other potential sellers that the consequences are serious. But it's not the longest sentence for espionage—Jonathan Pollard, who sold classified information to Israel, served over 30 years before being released.

The precedent matters. If Williams gets nine years, future prosecutors will point to that sentence when arguing for similar offenses. If he gets two or three years, it signals that selling defense contractor secrets isn't treated as harshly as the government publicly claims.

One wrinkle: Williams' lawyer has argued that the exploits Williams sold weren't classified. If a judge agrees that the materials weren't classified—despite being sensitive and restricted—it could affect the sentence. Classified information theft carries steeper penalties than theft of restricted but unclassified information.

After sentencing, Williams will likely be deported to Australia, his home country. He'll serve his sentence in a U.S. prison, then transfer to Australian custody. From there, Australia will decide whether to prosecute him under its own laws or release him.

Case Study: Lessons from Similar Insider Threat Cases

The Williams case isn't the first time a defense contractor employee has stolen secrets for foreign payment. History offers some instructive parallels:

Ana Montes (2001). An analyst at the Defense Intelligence Agency was convicted of spying for Cuba for 16 years. She had provided classified information about U.S. intelligence operations in Cuba, Puerto Rico, and elsewhere. She received $200,000 in cash from Cuban intelligence officers. Montes received a 25-year sentence.

Larry Wu-Tai Chin (1986). A retired CIA officer was convicted of espionage after selling secrets to China for over $140,000 over several decades. He was sentenced to life imprisonment and died in prison before his conviction could be appealed.

Robert Hanssen (2001). An FBI counterintelligence officer who spied for Russia received a life sentence after selling secrets that compromised U.S. intelligence operations.

Compared to these cases, Williams' situation is somewhat different. He wasn't selling detailed operational information. He was selling exploits—tools that could be used for many purposes. But the damage is potentially greater because these tools have widespread applicability.

What these cases have in common is that all the perpetrators had legitimate access to sensitive information. All of them violated the trust placed in them. And all of them received serious prison sentences. This suggests Williams' nine-year recommendation is consistent with historical precedent.

The Broader Context: Cybersecurity and National Security in 2025

The Williams case occurs in a context of escalating cyber threats and increasing concern about supply chain vulnerabilities. The U.S. government has made cybersecurity a priority, with agencies like CISA and NSA warning about persistent threats from China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea.

In this environment, the leak of eight zero-day exploits to a Russian broker is particularly concerning. These tools could be used for:

Espionage. Foreign intelligence agencies could use the exploits to infiltrate U.S. government systems, steal classified information, or monitor communications.

Critical infrastructure attacks. Power grids, water systems, transportation networks, and financial systems could be compromised, causing widespread damage.

Cybercrime. Criminal organizations could use the exploits for ransomware campaigns, banking fraud, or identity theft.

Proliferation. The Russian broker could sell the exploits to other governments or criminal networks, spreading the damage further.

The fact that this happened at a defense contractor that's supposed to be developing defensive and offensive cyber tools for the U.S. government adds another layer of irony and concern. Trenchant was supposed to be part of the solution, not part of the problem.

Moving forward, the U.S. government will likely take several steps:

- Increase oversight of defense contractor security practices

- Implement more aggressive vetting of cleared employees

- Invest in better insider threat detection technology

- Reassess the security posture of sensitive programs

- Potentially review all systems that used the stolen exploits

These steps will cost money and create friction, but the alternative—allowing more insider threats to succeed—is worse.

Best Practices for Organizations Handling Sensitive Data

While the Williams case is specific to defense contractors, the lessons apply more broadly to any organization handling sensitive information. Here are best practices:

Implement the principle of least privilege. Employees should have access only to the information they need for their jobs. Senior executives shouldn't get blanket access to everything just because of their position.

Monitor data access and exfiltration. Use data loss prevention tools to detect when sensitive files are accessed or copied. Review access logs regularly. Alert when suspicious patterns emerge.

Conduct regular security assessments. Bring in external auditors to evaluate your security controls. They'll find gaps that internal teams might miss.

Vet employees thoroughly and continuously. Background checks at hire are important, but continuous vetting throughout employment is critical. Monitor for financial distress, foreign contact, or other warning signs.

Implement compartmentalization. Sensitive information should be stored in separate systems with restricted access. No single person should have access to everything.

Create a strong security culture. Employees should understand why security matters and feel comfortable reporting suspicious activity without fear of retaliation.

Separate duties and responsibilities. The person who accesses sensitive files shouldn't be the person who authorizes access. The person who investigates breaches shouldn't be investigating themselves.

Use multi-factor authentication. This makes it harder for stolen credentials to be used.

Encrypt sensitive data. If data is exfiltrated, encryption makes it harder to use.

Train employees on security risks. Many breaches happen because employees don't understand the risks or the procedures.

The Road Ahead: Implications for Cybersecurity Policy

The Williams case will likely influence cybersecurity policy at multiple levels:

At the federal level, agencies like the Department of Defense and the Intelligence Community will probably issue new requirements for contractor security. These might include mandatory insider threat programs, more aggressive vetting, or enhanced monitoring.

At the industry level, trade associations representing defense contractors will likely develop new standards or best practices for insider threat detection and prevention.

At the technology level, vendors will market new tools designed to detect insider threats. Some of these tools will be valuable. Others will be expensive surveillance that makes work worse without improving security.

At the legal level, there might be new legislation addressing insider threats, espionage, or contractor security requirements.

All of this will take time. The Williams case is still ongoing. His sentencing hasn't happened. The full scope of the damage from the stolen exploits may not be known for months or years.

But one thing is certain: defense contractors and organizations handling sensitive information will face increased pressure to strengthen their security posture and their insider threat programs. The cost of another Williams is too high to ignore.

Conclusion: Trust, Oversight, and the Price of Complacency

Peter Williams had everything: a senior position at a respected defense contractor, a security clearance, a salary that put him in the upper-middle class. He threw it all away for cryptocurrency.

But this isn't really a story about one person's greed. It's a story about systems that failed. It's about a company that trusted its general manager too much and monitored him too little. It's about a clearance vetting process that missed the warning signs. It's about an investigation that took months to complete even after law enforcement knew what was happening.

Most importantly, it's a story about the tension between security and operational efficiency. Defense contractors need senior employees with broad access to develop innovative tools. But that broad access creates vulnerability. The Williams case shows what happens when that vulnerability is exploited.

The solutions aren't simple. You can't eliminate insider threats without making everyone's job harder and less efficient. You can't have perfect vetting without becoming intrusive. You can't monitor every employee without creating a culture of surveillance.

But you also can't ignore the problem. Eight zero-day exploits now potentially accessible to the Russian government is catastrophic. The person responsible made $1.3 million and will spend nine years in prison.

For the rest of the defense contracting industry, the message is clear: insider threats are real, detection requires vigilance, and the cost of failure is measured in national security and public trust. Williams' case will serve as a cautionary tale for years to come—a reminder that no employee is beyond suspicion, no position is immune to temptation, and no amount of clearance or training guarantees loyalty.

The question now is whether the industry, the government, and organizations handling sensitive information will learn from this case and strengthen their defenses. Or whether there will be another Williams, another set of stolen exploits, another scandal.

History suggests there will be. But there's also hope that each incident will make the next one harder to pull off. The Williams case might be the beginning of a new era of insider threat awareness and defense contractor security. Or it might just be the latest in a long series of incidents that we fail to learn from. Only time will tell.

FAQ

What is a zero-day exploit and why are they so valuable?

A zero-day exploit is a software vulnerability that the software vendor doesn't know about yet. The "zero" refers to the number of days the vendor has had to fix it. These exploits are valuable because they work against unpatched systems, making them useful for espionage, cybercrime, and cyber warfare. Zero-days can be worth anywhere from thousands to hundreds of thousands of dollars on the dark web, depending on their scope and applicability.

How does someone like Peter Williams get caught selling classified exploits?

Investigators use multiple techniques including cryptocurrency transaction analysis, communications monitoring, access log review, and behavioral analysis. In Williams' case, the FBI made contact with him in late 2024 and continued gathering evidence while maintaining surveillance. Once they had sufficient evidence of the sales to foreign brokers, they arrested him and built their case for prosecution. The cryptocurrency payments and internal communications provided the primary evidence.

What does the Russian broker do with these exploits?

The Russian broker acts as a middleman in the cyber weapons marketplace. They acquire sensitive cyber tools like exploits and sell them to various customers, which according to prosecutors includes the Russian government as well as other criminal organizations. These exploits are then used for espionage, infrastructure attacks, ransomware campaigns, and other cyber operations. The broad applicability of Williams' eight exploits means they could be used against millions of devices globally.

Why is L3 Harris responsible for what one employee did?

L3 Harris owns Trenchant, the subsidiary where Williams worked. While individual employees are responsible for their own crimes, the parent company bears responsibility for security practices, vetting procedures, and oversight of subsidiaries. L3 Harris will face fallout including potential loss of security clearances, government audits, contract reviews, and reputational damage. This incentivizes large contractors to strengthen their insider threat programs.

What are the legal charges against Peter Williams?

Williams pleaded guilty to selling classified hacking tools to foreign brokers. The specific charges likely include espionage, theft of government property, unauthorized sale of defense information, money laundering related to the cryptocurrency payments, and potentially other federal crimes. The Justice Department is recommending nine years in prison, three years of supervised release,

How can organizations prevent insider threats like this?

Organizations should implement the principle of least privilege (limiting access to what's needed for the job), deploy data loss prevention tools to detect when sensitive files are accessed or copied, conduct continuous employee vetting throughout employment, monitor for warning signs like financial distress or foreign contact, separate duties so no single person has all access, use multi-factor authentication, encrypt sensitive data, and create a strong security culture. Regular external security assessments also help identify gaps that internal teams might miss.

What makes this case significant for national security?

This case is significant because it demonstrates how vulnerabilities in defense contractor security can leak weapons-grade hacking tools to foreign governments. Eight zero-day exploits potentially accessible to Russia represent a catastrophic loss of U.S. cyber capability and leverage. It forces a reckoning with how the U.S. protects sensitive defense technology and how it vets employees with access to classified information. The case will influence policy and security practices across the defense industrial base.

When will Peter Williams be sentenced and what's expected?

Williams is scheduled to be sentenced on February 24, 2026. The Justice Department is recommending nine years in prison. His attorney is arguing for less, claiming Williams didn't intend to harm the U.S. or Australia. The judge will consider both arguments and issue the final sentence. Nine years is substantial but consistent with historical precedent for espionage cases. After serving his sentence, Williams is expected to be deported to Australia.

How does cryptocurrency make financial crimes harder to detect?

Cryptocurrency transactions don't pass through traditional banking channels, which means traditional financial monitoring misses them initially. However, cryptocurrency transactions are permanently recorded on public blockchains, creating a verifiable audit trail. Sophisticated investigators can connect cryptocurrency addresses to individuals through exchange records, device analysis, and timing correlations. In Williams' case, the cryptocurrency payments actually made the crime traceable despite appearing anonymous initially.

What employee was wrongly blamed for Williams' actions?

A Trenchant employee was fired after the company accused him of stealing and leaking exploits, when actually it was Williams who was stealing them. Williams, as general manager, oversaw both the theft and the investigation that blamed his subordinate. The fired employee later received notification that he'd been targeted with government spyware, which has never been fully explained. Prosecutors highlighted this as particularly egregious behavior during Williams' prosecution, noting he let someone else be punished for his own crimes.

Key Takeaways

- Peter Williams, general manager at L3Harris-owned Trenchant, made $1.3 million selling 8 zero-day exploits to Russian brokers between 2022-2025

- The stolen exploits could potentially enable access to millions of computers and devices globally, including U.S. critical infrastructure

- Despite FBI contact in late 2024, Williams continued selling exploits, demonstrating calculated intent and arrogance

- Williams allowed another employee to be fired for the theft he committed, raising serious ethical and legal concerns during prosecution

- Defense contractors must implement stronger insider threat detection, data loss prevention, and continuous employee vetting to prevent similar breaches

- The case faces sentencing in February 2026 with prosecutors recommending 9 years imprisonment, setting precedent for insider threat prosecutions

Related Articles

- Volvo Conduent Data Breach: 17,000 Customers Exposed [2025]

- SmarterTools Ransomware Breach: How One Unpatched VM Compromised Everything [2025]

- NordVPN Complete Plan 70% Off: Full Deal Breakdown [2025]

- Surfshark's Free VPN for Journalists: Protecting 100+ Media Outlets [2025]

- The Hidden Threat of Typosquatting: Protecting Your VPN Experience [2025]

- Beware of Fake 7-Zip Installers Laced with Malware [2025]