UK Scraps Digital ID Requirement for Workers: What Changed and Why It Matters [2025]

In September 2024, UK Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer made a bold announcement that sent shockwaves through the country. Workers would need a digital ID to prove their right to work in the United Kingdom. No exceptions. No alternatives. The statement was unambiguous: "You will not be able to work in the United Kingdom if you do not have digital ID. It's as simple as that."

Fast forward just a few months, and the government reversed course entirely.

The mandatory digital ID requirement is gone. Scrapped. But here's what most people missed in the headlines: the UK isn't abandoning the digital transformation of employment verification. It's just taking a step back from forcing everyone into it immediately. The government still intends to fully transition to digital right-to-work checks by 2029, a timeline that gives employers and workers nearly five years to adapt.

This isn't a minor policy tweak. It's a fundamental shift in how the government approaches digital identity, public trust, and the balance between security and individual freedom. And the story behind this reversal reveals something important about modern governance, public resistance, and the real challenges of implementing national ID systems in democracies.

Let's dig into what happened, why it happened, and what it means for the future of work in the UK.

The Original Plan: Mandatory Digital ID for All Workers

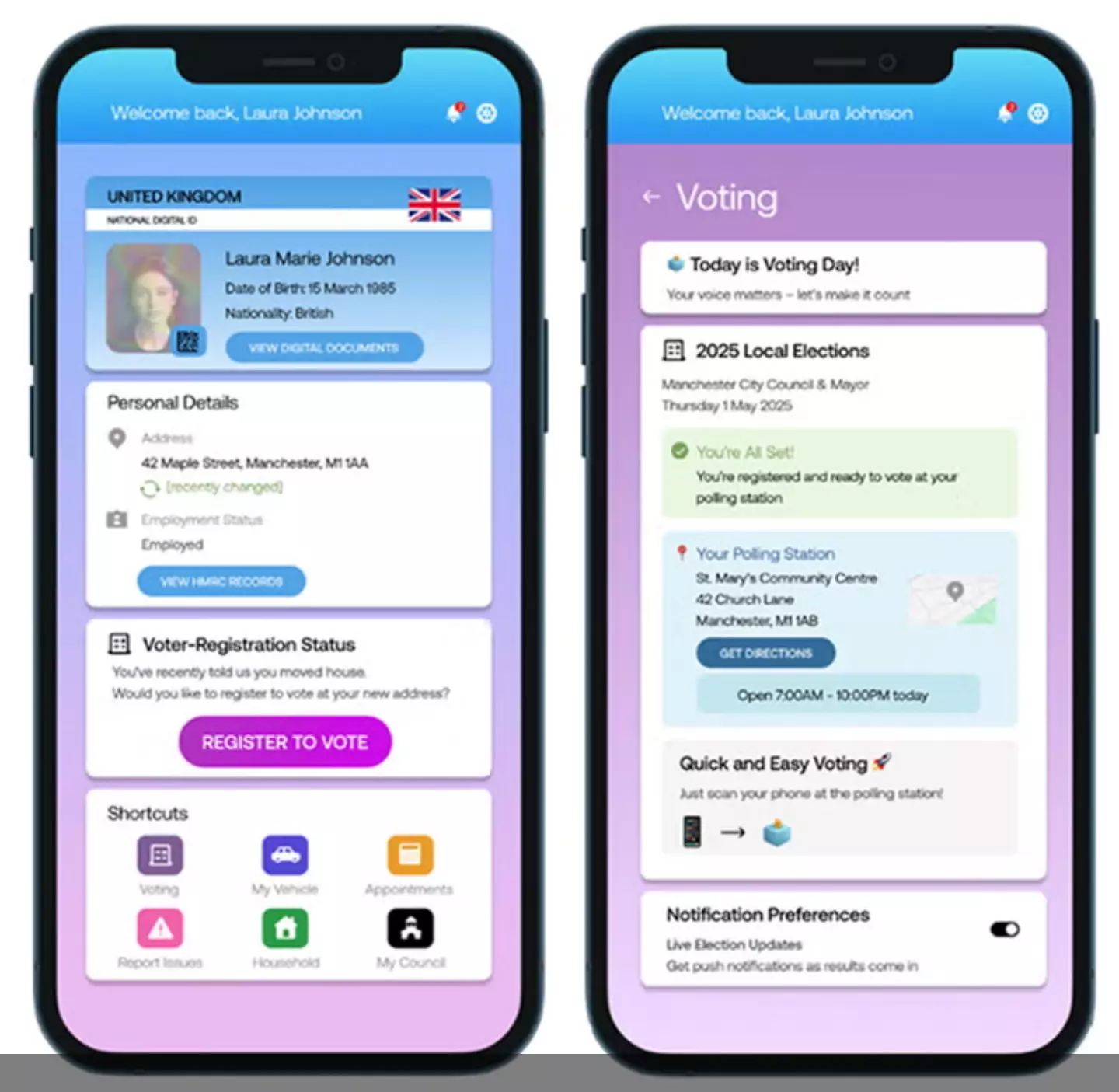

When the government unveiled its digital ID initiative in September, the framing was straightforward. Paper-based right-to-work documentation was outdated. It was vulnerable to fraud. It was inefficient. A digital system using biometric passports and modern verification technology would solve these problems, the government argued.

But there was a critical component that caused immediate concern: this wouldn't be optional. Every worker in the UK would need to register with a state-controlled digital ID system. There would be no paper alternative. No exceptions for those uncomfortable with biometric data collection. No opt-out clause.

The government's reasoning made intuitive sense from a security standpoint. Illegal immigration and employment fraud cost the country resources. A centralized, biometric-based system would make it significantly harder for someone to work illegally using false documents or borrowed credentials. From a bureaucratic efficiency perspective, eliminating paper-based checks would save time, reduce administrative burden, and create a more standardized verification process across all employers.

What the government didn't fully anticipate was the visceral public reaction to the idea of a mandatory state ID system.

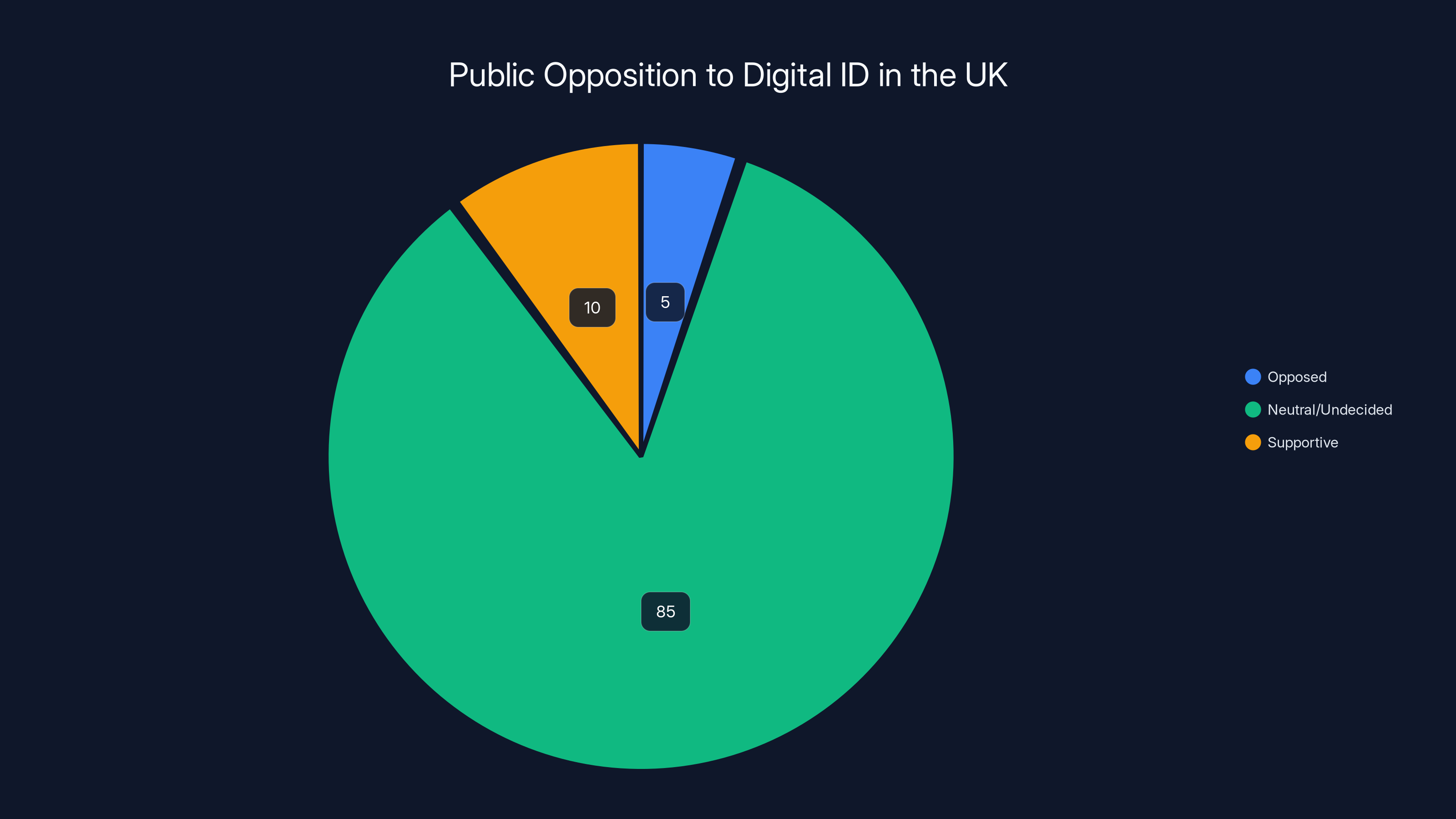

Estimated data shows that nearly 5% of the UK population actively opposed digital IDs, with a small percentage supportive and the majority remaining neutral or undecided.

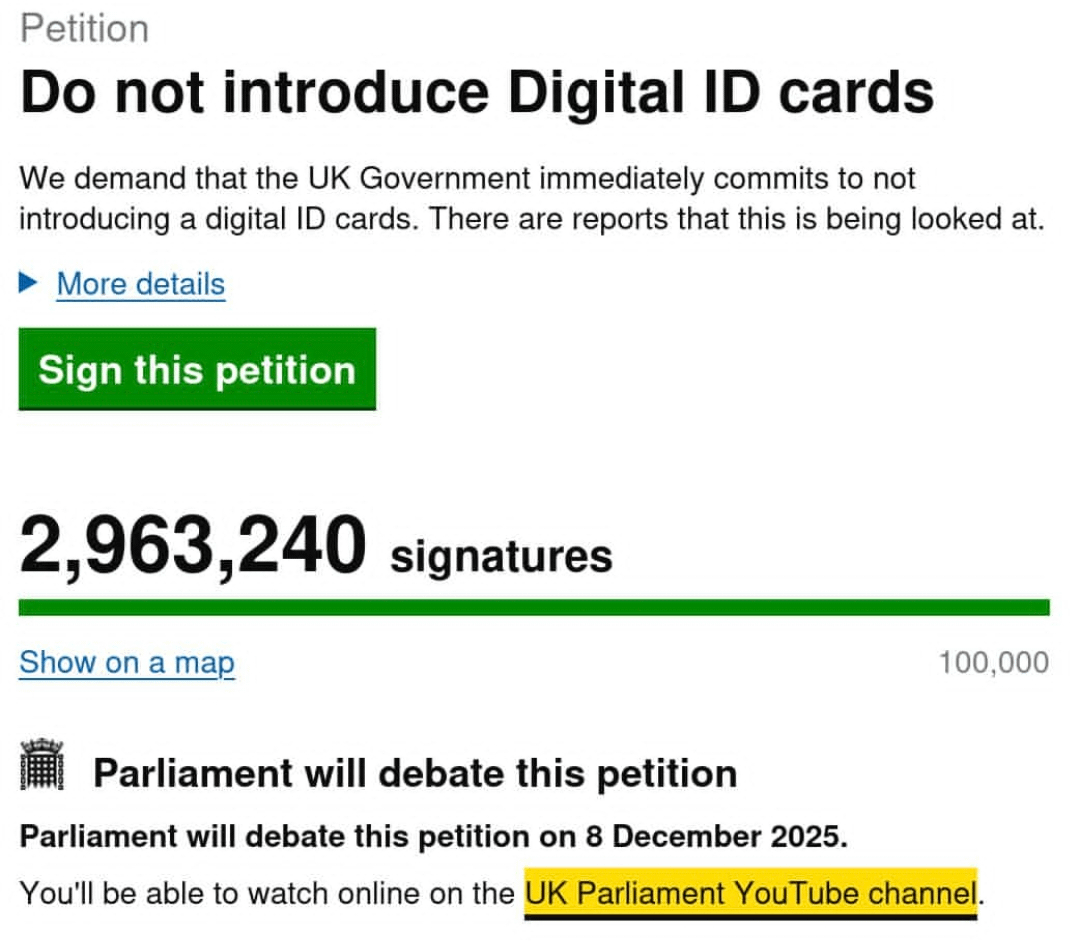

The Public Backlash: Nearly 3 Million Voices Against Digital ID

The opposition came quickly and overwhelmingly. Almost 3 million people signed an official parliamentary petition protesting the introduction of digital IDs. That's not a niche concern from a small activist group. That's nearly 5% of the UK population actively mobilizing against the policy.

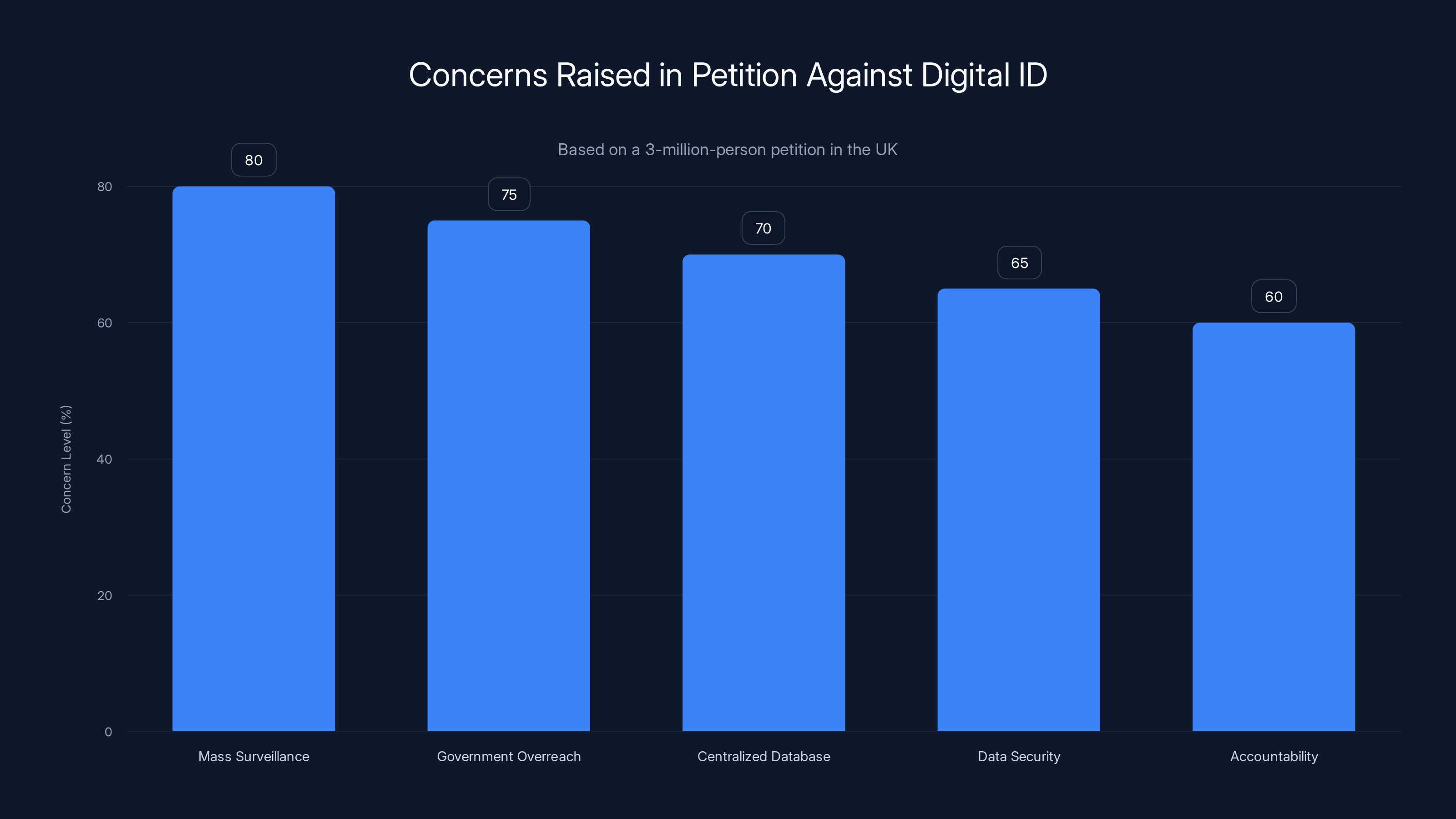

The petition text was clear and pointed: "We think this would be a step towards mass surveillance and digital control, and that no one should be forced to register with a state-controlled ID system. We oppose the creation of any national ID system."

This wasn't just about inconvenience or bureaucratic complexity. It touched on fundamental concerns about government power, data privacy, and individual liberty. In the UK, where there's no written constitution and where governmental overreach has been a historical concern, the idea of a centralized biometric ID system triggered deep-seated anxieties.

Think about what the system would require: biometric data (fingerprints, facial recognition data, iris scans). A centralized database linking this information to employment records. Government agencies having direct access to verify employment status. The potential for mission creep, where a system initially designed for right-to-work verification could eventually be used for broader surveillance or control purposes.

For a significant portion of the population, this wasn't theoretical. Privacy advocates, civil liberties organizations, and security researchers pointed out that once such a system exists, it becomes a target for cybercriminals, foreign actors, and potentially corrupt government officials. A data breach wouldn't just expose employment information. It would expose biometric data that can't be changed if compromised.

The backlash also crossed typical political divides. Conservative voters worried about government overreach. Left-leaning voters concerned about surveillance and social control. Libertarians and civil libertarians opposing any expansion of state ID systems. Religious communities worried about the implications of digital tracking. Business owners uncertain about implementation costs and compliance requirements.

What emerged was a rare moment of genuine consensus: the public didn't want this.

Estimated data shows mass surveillance and government overreach as top concerns in the petition against digital ID. Estimated data.

Why the Government Reversed Course So Quickly

Politically, the reversal made sense. The government was only months into Keir Starmer's tenure. The Labour Party had won the general election with promises of stability and modernization, not controversial new surveillance systems. When faced with a groundswell of opposition that included nearly 3 million petition signatures, pushing forward would have damaged political capital and created unnecessary friction with voters.

But there was more to it than just political pragmatism. The backlash revealed a fundamental truth about digital ID systems: they require public trust to function effectively. If significant portions of the population distrust the system, oppose it philosophically, or fear government misuse, voluntary compliance suffers. People find ways around it. They resist. Implementation becomes messy and expensive.

Governments have learned this lesson repeatedly around the world. When ID systems are perceived as oppressive or dangerous, they encounter resistance that makes them difficult and costly to implement, regardless of their theoretical benefits.

The government also faced practical implementation questions that the backlash forced into the open. The officials had still not explained exactly how the digital ID program would work. Which government agencies would have access? How would data be stored and protected? What safeguards would exist against misuse? How much would it cost? How long would registration take? Could employers access the system directly, or would there be an intermediary verification process?

These weren't minor technical details. They were fundamental design questions that needed answers before mandatory adoption could be considered. The public petition essentially demanded those answers before accepting the system.

The Revised Strategy: Digital Right-to-Work Checks Without Mandatory ID

So the government pivoted. Instead of requiring all workers to register with a digital ID system, the new approach focuses on digital right-to-work verification itself. The distinction is crucial.

Under the revised plan, employers would transition from paper-based documentation to digital verification systems. Instead of checking physical passports and work permits, they'd use biometric passports and digital verification methods. But the emphasis shifted from "everyone must have a government-issued digital ID" to "the process of verifying the right to work will become digital."

This is actually a clever policy adjustment. It achieves many of the government's original goals, removes some of the most controversial elements, and makes the system feel more voluntary. Workers wouldn't necessarily need to register with a centralized state ID system. Instead, employers would verify employment eligibility using existing biometric documents (like passports) that most workers already have.

The timeline for this transition is 2029, roughly five years away. This gives the government time to develop the actual systems, work out technical standards with employers, address privacy concerns through legislation, and gradually build public acceptance. It also gives technology vendors time to develop compliant verification solutions.

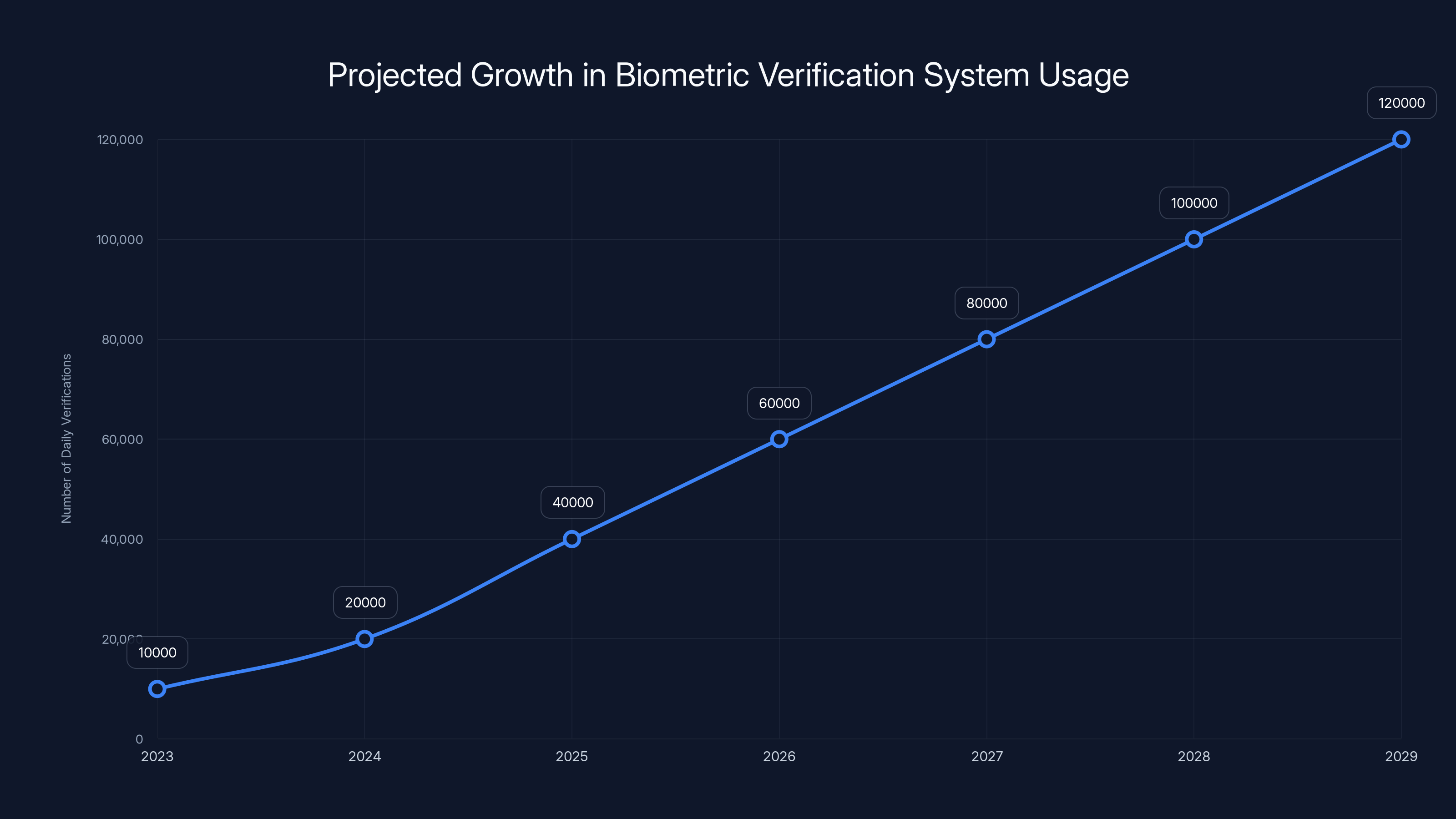

Estimated data shows a projected increase in daily biometric verifications from 10,000 in 2023 to 120,000 by 2029, highlighting the need for robust infrastructure development.

Why Paper-Based Systems Are Actually Problematic

Underneath the policy debate is a real issue that the government correctly identified: paper-based right-to-work verification is genuinely vulnerable to fraud and abuse.

Employers currently verify the right to work by physically inspecting documents. A passport. A visa. A work permit. These documents can be forged. They can be photocopied poorly in ways that look convincing to someone not trained in document authentication. Someone can borrow another person's documents temporarily to get hired, then hand them back after passing the initial check.

The system is also inefficient. Every employer must individually verify each new employee's documents. There's no central record of who's authorized to work. If someone is deported or has their work authorization revoked, there's no automatic notification system to employers. The person might continue working because their employer has no way to know their status changed.

Digital verification systems solve these problems. Biometric passports contain security features that are extremely difficult to forge. Digital verification systems can cross-reference against central databases of authorized workers, visa holders, and people whose work authorization has been revoked. The verification happens in real-time, not through manual inspection by people who may or may not be trained in authentication.

From a security standpoint, the case for digital right-to-work verification is strong. The controversy wasn't really about whether digital systems are better. It was about the mechanism for implementing them and the broader implications.

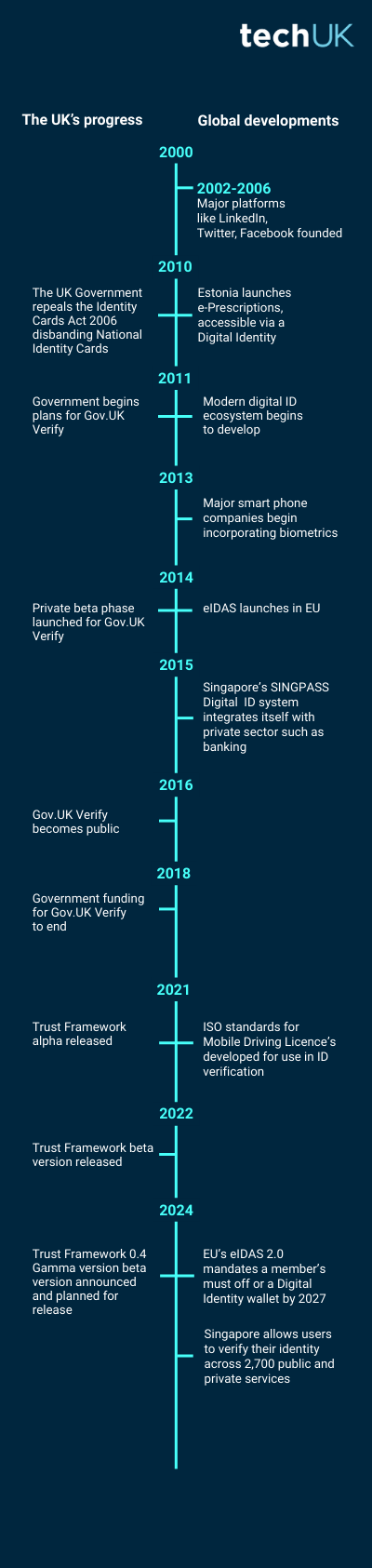

The Global Context: Why National ID Systems Generate Suspicion

To understand the UK reaction, it helps to understand global attitudes toward national ID systems. The UK has historically resisted national identity documents. Unlike most European countries, the UK doesn't have a mandatory national ID card. Citizens are identified primarily through passports, driving licenses, and other documents that serve secondary purposes.

This historical absence of a national ID system is partly philosophical. The UK has a cultural emphasis on individual privacy and skepticism toward government surveillance. It's also partly practical. With a global empire and a history of global reach, the UK developed identification systems around travel documents rather than domestic ID systems.

Contrast this with countries like Germany, France, or Spain, where national ID cards are standard. These systems work reasonably well in those contexts, but they're also viewed with more suspicion in the UK than in their home countries.

The government's proposal was essentially trying to introduce a de facto national ID system by requiring digital ID registration for employment purposes. Once such a system exists, scope creep becomes inevitable. Eventually, it gets required for accessing healthcare, claiming benefits, opening bank accounts, or other services. Before you know it, what started as an employment verification system has become a comprehensive surveillance infrastructure.

This isn't theoretical. It's happened in other countries. Once a centralized biometric ID system exists, subsequent governments find it convenient to expand its usage. The infrastructure is already there. The precedent is already set. The public has already accepted the basic concept.

Estimated data shows Estonia leading in both effectiveness and public acceptance due to high digital literacy and trust in government. Germany follows with strong infrastructure, while the US lags in public acceptance.

Data Security Concerns: The Technical Reality

From a cybersecurity perspective, the concerns about a centralized biometric ID database are legitimate.

Biometric data is fundamentally different from passwords or regular personal information. If your password is compromised, you change it. If your email is breached, you can regain access. But if your biometric data is stolen, you can't get it back. You can't change your fingerprints. You can't update your facial geometry. These identifiers are permanent, unchangeable, and unique.

A successful breach of a national biometric database would be catastrophic. Every person whose data was stolen would have their identity compromised in a way that can never be fully fixed. Attackers could use stolen biometric data to authenticate as legitimate users for decades.

Security researchers have documented vulnerabilities in biometric systems repeatedly. Facial recognition can be fooled with high-quality photos or masks. Fingerprint readers can be confused by high humidity or dirt. Iris scanners have been defeated with printed images and contact lenses. None of these are trivial attacks for a typical criminal, but state-sponsored actors or sophisticated criminal organizations could manage them.

A centralized system is also a single point of failure. If it goes down, right-to-work verification becomes impossible. If it's compromised, the entire identity system is compromised. Distributed systems are generally more resilient, but they're also more expensive and complex to coordinate.

The UK government would need to invest heavily in cybersecurity infrastructure, establish strict access controls, audit all data access, maintain immaculate security hygiene, and still accept some residual risk. All of this adds significant cost and complexity to a system that was supposed to simplify employment verification.

The Business Impact: What Employers Need to Know

For UK employers, the revised digital right-to-work policy is actually good news. They get the benefits of digital verification without the controversial mandatory ID requirement.

Currently, employers must verify employees' right to work manually. This involves checking original documents, making copies, maintaining records, and staying current with government requirements. If an employee's right to work changes (visa expires, work authorization is revoked), the employer likely won't know unless the employee tells them.

Digital verification systems will streamline this significantly. Instead of manually checking documents, employers will use digital platforms to verify employment eligibility. The systems will automatically flag if an employee's authorization has expired or been revoked. There's an audit trail of who was verified when. Compliance becomes easier to demonstrate to regulators.

For small employers, this is particularly valuable. Currently, a sole proprietor running a small business might not have dedicated HR staff trained in document verification. Digital systems will make it easier for businesses of all sizes to stay compliant.

But there are costs and challenges. Employers will need to integrate new digital verification systems into their hiring processes. They'll need to train staff on using the new systems. They may need to pay fees to access the digital verification platforms. There will be a transition period where some employers use paper-based systems and others use digital systems.

The five-year timeline to 2029 gives employers time to prepare. But businesses that don't start planning now risk being caught unprepared when the digital transition accelerates.

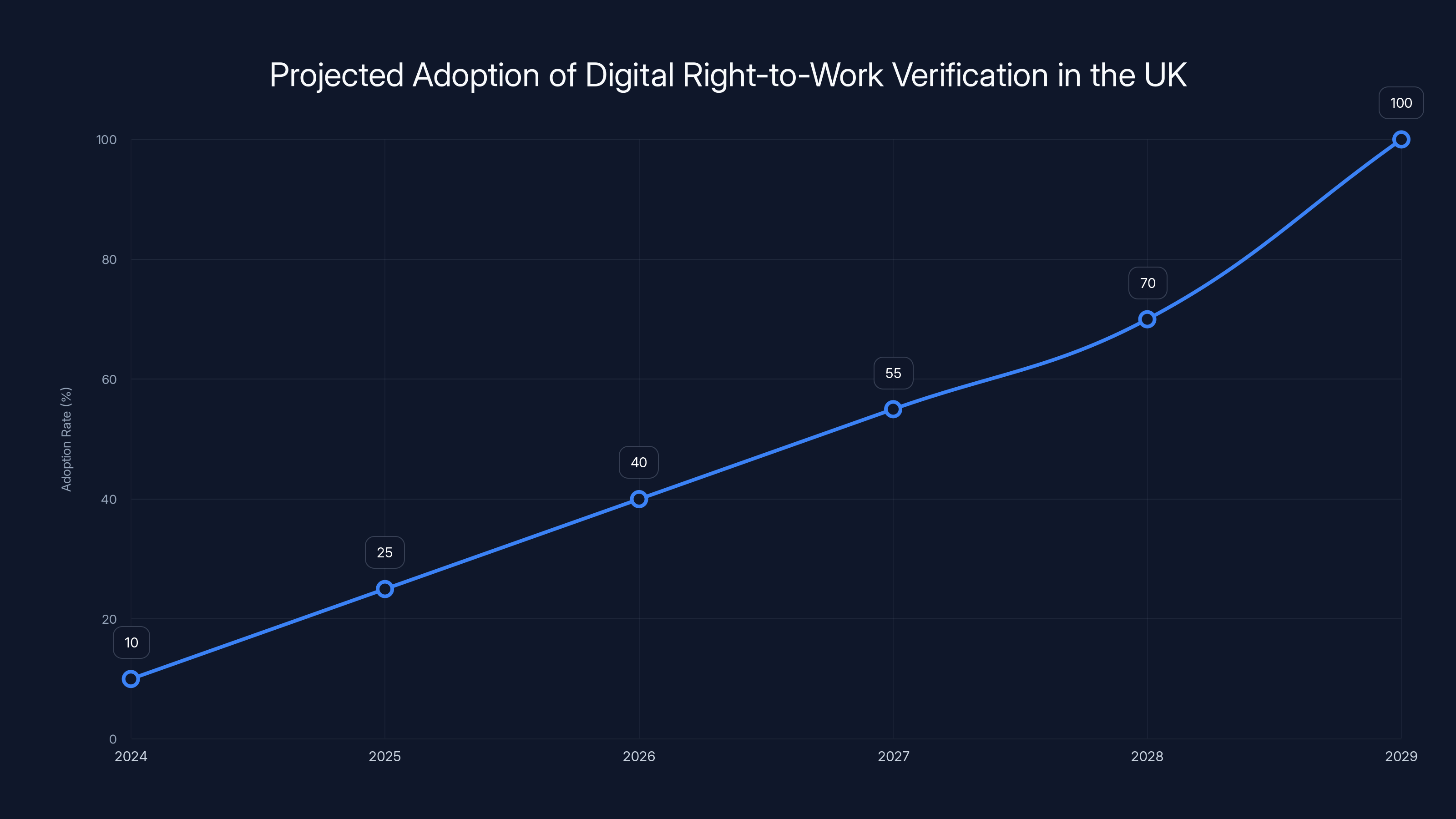

The UK's transition to digital right-to-work verification is projected to reach full adoption by 2029, with a gradual increase in adoption rates starting from 2024. Estimated data.

Immigration and Asylum: The Broader Policy Context

The digital ID initiative didn't exist in a vacuum. It was part of the UK government's broader approach to immigration enforcement and workplace compliance.

The UK has been tightening immigration requirements and increasing workplace enforcement of immigration rules. Right-to-work checks are an important tool for preventing illegal employment. But the current system is relatively easy to evade. Someone with a forged passport can pass a manual document check if they're lucky and the inspector isn't thorough.

A digital verification system would make illegal employment significantly harder. It would catch people trying to work with forged documents or other people's credentials. It would make immigration enforcement more effective.

For the government, this is valuable from a policy perspective. For immigration advocates worried about undocumented workers, this is good security. For humanitarian advocates worried about treating asylum seekers fairly, this raises concerns about creating barriers to employment for vulnerable populations.

The revised approach actually handles this better than the original proposal. Instead of requiring digital ID registration (which some asylum seekers might resist or be unable to complete), the system focuses on verifying credentials through existing biometric documents. Most people in the UK, including asylum seekers with proper work authorization, already have these documents.

Privacy Legislation and Safeguards: The Missing Piece

One of the gaps the public backlash exposed was the absence of specific privacy legislation governing how the digital right-to-work system would operate.

The UK has data protection law through the Data Protection Act 2018 and the UK GDPR. But these are general frameworks. They don't specifically address how a government-run biometric employment verification system should operate, what specific safeguards should exist, or what the consequences are for misuse.

The government indicated it would eventually publish more detailed plans, but no specific legislation was presented alongside the digital ID announcement. This meant the public was being asked to trust a system without knowing exactly what legal protections would exist.

For the revised approach to work, the government should publish clear legislation specifying:

- Which government agencies have access to the system

- What data is stored and for how long

- What audit trails exist for data access

- What happens if someone's data is breached

- What independent oversight exists

- How people can correct errors in the system

- What rights exist to refuse or challenge verification

- How the system handles false positives and errors

- What penalties exist for misuse by government officials

Without this legislation in place before implementation, the system will remain controversial.

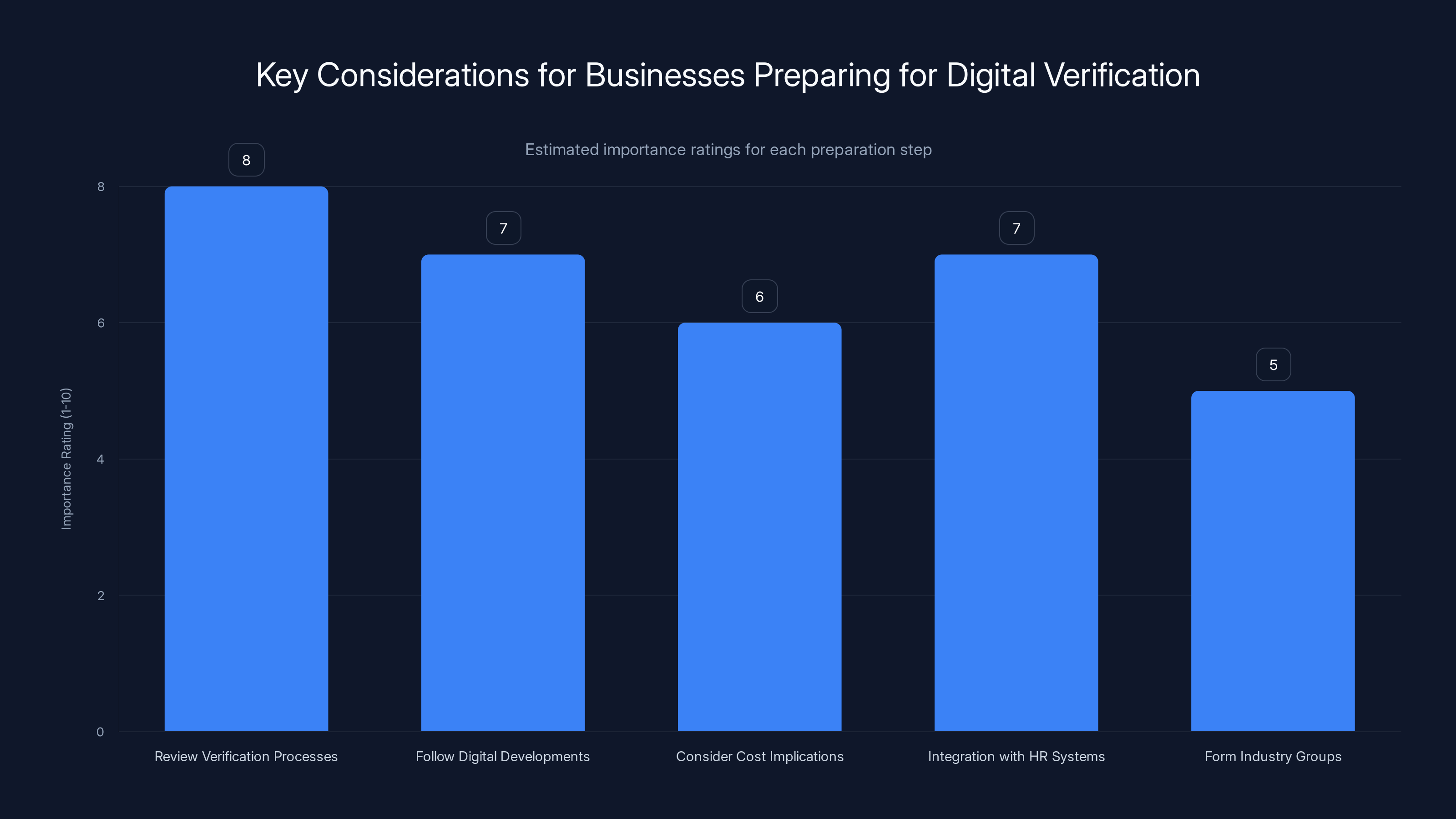

Reviewing verification processes and following digital developments are crucial steps for businesses preparing for the 2029 transition. Estimated data.

Biometric Technology: The Actual Implementation Challenge

Beyond the policy and privacy questions, there are genuine technical challenges in implementing a nationwide biometric verification system.

Biometric passports exist and contain biometric data, but the infrastructure to reliably verify this data at scale hasn't been fully tested. Employers would need access to scanning equipment that can read biometric passports securely. They'd need real-time connectivity to verification systems. The systems would need to work reliably across different devices, internet connections, and technical setups.

Consider a small business in rural Scotland with spotty internet connectivity. Current right-to-work verification involves checking a physical document that doesn't require internet. A digital system would require reliable online connectivity and real-time database access. If the verification system goes down, hiring grinds to a halt.

The 2029 timeline gives the government time to develop robust infrastructure, but it's not guaranteed. Government IT projects in the UK have a mixed track record. Major projects frequently overrun budgets and timelines. The infrastructure investment required for a nationwide biometric verification system is substantial.

Scaling biometric systems is also technically complex. A system that works fine with 10,000 daily verifications might struggle with 100,000. Real-time biometric verification at scale is harder than it sounds.

Employer Preparation: What Businesses Should Do Now

With the timeline set for 2029, UK employers should start preparing now, even though mandatory transition is years away.

First, businesses should review their current right-to-work verification processes. What documents do they check? How do they store records? What's their compliance rate with government requirements? Are there gaps or inefficiencies?

Second, employers should start following developments in the digital verification space. Technology vendors are already developing systems that meet anticipated requirements. Early adopters will have advantages in terms of learning curve and process optimization.

Third, businesses should consider the cost implications. Digital verification systems will likely require subscription fees or per-verification fees. For large employers, this might be modest per-employee cost. For small businesses, it could be more significant.

Fourth, employers should think about integration with existing HR systems. Will the digital verification system integrate with their payroll software? Their applicant tracking system? Their employee records system? Seamless integration will make the transition smoother.

Fifth, small businesses should consider forming industry groups to negotiate with technology vendors. Collective bargaining might help keep costs down and ensure that systems are designed to work for businesses of all sizes.

The Future of Digital Verification: Post-2029 Plans

Once the digital right-to-work verification system is fully implemented in 2029, what happens next?

The government has indicated that digital right-to-work checks would become the default method. But what does that mean specifically? Will paper checks still be accepted as alternatives? How will the system handle edge cases and errors? What happens when people forget their documents or don't have biometric passports?

Historically, government transitions to new systems are messier than planned. There's typically a period where both the old and new systems operate simultaneously. Employers can choose which to use. Gradually, pressure increases for everyone to transition to the new system. Eventually, the old system is deprecated.

For right-to-work verification, this might mean that by 2035 or 2040, paper-based checks are no longer officially accepted, but employers using old systems might not face immediate penalties. The transition would be gradual and somewhat chaotic, as transitions typically are.

Longer-term, there's a question about scope expansion. Will the government try to expand the digital right-to-work system into a broader identification system, touching other services? Or will it remain confined to employment verification? Public trust will likely determine this. If the system works well, handles data securely, and remains non-controversial, there will be political appetite to expand it. If it's plagued by problems or becomes controversial again, it will likely remain limited to its specific purpose.

International Comparisons: How Other Countries Handle Employment Verification

The UK isn't inventing employment verification from scratch. Other countries have implemented digital systems, and their experiences offer lessons.

Germany uses biometric passports and digital verification for employment purposes. The system works reasonably well, but it required substantial infrastructure investment and ongoing governance oversight. Germany also has different cultural attitudes toward government ID systems, making it somewhat more acceptable there than in the UK.

Estonia has one of the most advanced digital governance systems in the world, with digital ID widely accepted for government services. But Estonia is a small country with high digital literacy and relatively high trust in government. What works in Estonia might not work in a country of 67 million people with more diverse views of government surveillance.

Australia implemented a digital right-to-work system several years ago using facial recognition and biometric data. The system has worked reasonably well for employment verification but has faced criticism over data security and privacy. Australia also had a different cultural context, with less historical resistance to government ID systems.

The US has not implemented a national employment verification system at the federal level, though E-Verify is widely used. E-Verify is largely database-based rather than biometric, checking social security numbers and visa status against government databases. It's less sophisticated than the UK system but also less controversial.

From these international examples, several patterns emerge:

- Digital employment verification systems work better in countries with high digital infrastructure and digital literacy

- Public acceptance is essential, and systems implemented without sufficient public trust face ongoing resistance

- Data security becomes a critical issue, and any breaches seriously damage public confidence

- Scope creep is a real risk once the infrastructure exists

- The transition period from old to new systems is expensive and messy regardless of how well the system is designed

Civil Liberties and Surveillance: The Broader Debate

The digital ID backlash was fundamentally about concerns regarding surveillance and government power, not just technical disagreements about how to verify employment.

There's a legitimate philosophical debate about how much surveillance infrastructure a democratic government should maintain. On one side, there's the security and efficiency argument: better tracking systems catch criminals, prevent fraud, and make government more efficient. On the other side, there's the liberty argument: extensive surveillance infrastructure enables government oppression, chills free expression, and puts power in fewer hands.

Democracies throughout history have struggled with this balance. After 9/11, governments increased surveillance significantly, arguing security required it. Twenty years later, many of those same governments are reconsidering, recognizing that the surveillance infrastructure built for security purposes gets used for other purposes and hasn't actually stopped that many attacks.

The UK's historical resistance to national ID systems reflects this tension. The government wanted to improve employment verification, but citizens worried that the infrastructure built for this purpose would eventually be used for broader surveillance.

Interestingly, the revised approach doesn't actually solve this concern entirely. Digital right-to-work verification still creates a government record of who is authorized to work. It still involves biometric data collection. It still creates a system that could theoretically be expanded. But it does remove the most obvious mechanism: mandatory registration with a centralized government ID system.

The compromise reflects a reasonable middle ground: use digital technology to improve specific government functions, but avoid building unnecessary surveillance infrastructure beyond what's needed for that function.

The Psychology of Public Resistance to ID Systems

Why did public resistance to the digital ID proposal emerge so quickly and powerfully?

Psychologically, people fear what they don't understand and what they can't control. A centralized biometric database is both poorly understood (few people know exactly how biometric systems work or how government databases are secured) and outside individual control (you can't opt out or withdraw consent once the system exists).

People also fear mission creep, even when current government officials promise limited use. They know that future governments might use the same infrastructure differently. They know that what's promised as one thing often becomes another.

There's also a cultural factor. In the UK, there's a historical tradition of skepticism toward government power and a philosophical belief that individuals should have privacy rights that governments can't violate just because they're convenient. This isn't unique to the UK, but it's particularly strong there compared to some other countries.

Finally, people distrust institutions they perceive as unaccountable. The government announced a major new identification system without extensive public consultation. It didn't explain how the system would work. It didn't publish specific legislation governing its use. The lack of transparency fueled suspicion that something untoward was being hidden.

The government could have addressed some of this by:

- Consulting with privacy advocates and security researchers before announcing the policy

- Publishing detailed technical specifications and legal safeguards alongside the announcement

- Explaining specific mechanisms for oversight and accountability

- Offering concrete answers to FAQs about how the system would work

- Soliciting public feedback on privacy concerns before implementation

Instead, it announced the policy as a fait accompli, triggering immediate suspicion and backlash.

The Timeline and What It Means

The 2029 target date for full digital transition is significant for several reasons.

It's far enough away that the government has time to develop systems, address concerns, pass legislation, and build public acceptance. It's close enough that work needs to start immediately. Technology vendors need time to develop compliant systems. Employers need time to integrate new processes. The government needs time to build the infrastructure.

Five years is both a reasonable timeframe and an optimistic one. Reasonable because it gives genuine time for planning and implementation. Optimistic because government IT projects frequently miss timelines, especially when they're technically complex.

If history is any guide, the actual full transition might not happen until 2030 or 2031, with gradual adoption happening in 2029 but not universal implementation. Some employers will transition early. Others will resist until forced. The government might grant extensions for businesses claiming technical difficulty.

Looking Forward: What Comes Next

The scrapping of the mandatory digital ID requirement is essentially a political reset. The government acknowledges that the original approach was too aggressive and lacked sufficient public support. The revised approach focuses on digital right-to-work verification while removing the most controversial element: mandatory centralized ID registration.

But this doesn't mean digital employment verification won't happen. The government remains committed to transitioning away from paper-based systems by 2029. What's changed is the mechanism and the framing.

For workers, employers, and privacy advocates, several important questions remain unanswered:

- How exactly will the digital verification system work technically?

- What legal safeguards will govern data protection and privacy?

- How will the government prevent scope creep beyond employment verification?

- What appeals process exists for someone incorrectly flagged as unauthorized to work?

- How much will the system cost employers and taxpayers?

- What happens in edge cases and when systems fail?

- How will the government ensure the system doesn't discriminate against certain groups?

The next phase will likely involve the government publishing detailed technical specifications, legal frameworks, and implementation plans. This will trigger another round of public scrutiny, likely from both security researchers and civil liberties advocates.

The story of the UK digital ID requirement is ultimately a story about the balance between technological progress and democratic values. The government wanted to modernize a system that was genuinely vulnerable to fraud. Citizens wanted assurance that new systems wouldn't become tools for oppression. The compromise reflects both perspectives: digital modernization, but with built-in safeguards against surveillance overreach.

Whether the revised approach actually works—whether it achieves the security benefits without triggering renewed privacy concerns—remains to be seen. But the process of reaching this compromise demonstrates that democratic publics can push back against government surveillance initiatives, and governments will respond when faced with sufficient opposition.

FAQ

What is a digital ID, and how does it differ from a digital right-to-work check?

A digital ID is a government-issued identification system that citizens must register with and that serves multiple purposes across government services. A digital right-to-work check is specifically a system for verifying that an individual is authorized to work in a country, without requiring separate registration with a broader ID system. The UK originally proposed mandatory digital ID registration; it revised this to focus on digital right-to-work verification instead.

Why did the UK government originally propose mandatory digital ID for workers?

The government identified genuine problems with paper-based right-to-work verification: it's vulnerable to fraud, inefficient, and open to abuse. A digital system using biometric data and real-time verification would address these issues by making it harder to forge documents and allowing instant cross-reference with government databases of authorized workers. From a bureaucratic standpoint, digital systems reduce administrative burden and create audit trails.

What were the main concerns raised in the 3-million-person petition against digital ID?

Petitioners expressed concerns about mass surveillance, government overreach, and the creation of a centralized biometric database. The core worry was that once such a system existed, it would inevitably expand beyond employment verification to other government services, creating comprehensive surveillance infrastructure. Petitioners also worried about data security, government accountability, and the lack of ability to change biometric identifiers if they were compromised.

How does the revised digital right-to-work system differ from the original mandatory digital ID proposal?

The revised system focuses specifically on digitizing the process of verifying employment eligibility, rather than requiring everyone to register with a centralized government ID system. Instead of a mandatory ID registration, employers would verify workers using existing biometric documents like passports. This removes the most controversial element while still achieving digital modernization of employment verification.

What is the timeline for implementing the digital right-to-work system?

The government plans a full transition to digital right-to-work checks by 2029, approximately five years from the original announcement. This timeline allows for system development, legal framework creation, technology vendor preparation, and employer integration. However, government IT projects frequently exceed timelines, so the actual full implementation might extend into 2030 or 2031.

What are the cybersecurity risks of a centralized biometric database?

Biometric data cannot be changed if compromised, unlike passwords or personal information. A successful breach would expose permanent identifiers that criminals could use for identity fraud indefinitely. Biometric systems can also be defeated through various methods if they're not extraordinarily well-designed and maintained. A centralized system represents a single point of failure where a breach affects everyone simultaneously.

What do employers need to do to prepare for the transition to digital right-to-work checks?

Employers should review their current verification processes, stay informed about digital verification system development, evaluate the cost implications of integration, consider compatibility with existing HR systems, and potentially join industry groups negotiating with technology vendors. The five-year timeline provides time to plan, but early movers will have advantages in implementation efficiency.

How do other countries handle employment verification, and what can the UK learn from them?

Germany uses biometric passports and digital verification; Estonia has highly advanced digital governance systems; Australia implemented facial recognition employment verification. Lessons from these countries suggest that digital systems work better with high digital infrastructure and literacy, public trust is essential, data security is critical, scope creep is a real risk, and transition periods are expensive and complicated regardless of system design quality.

Could the digital right-to-work system eventually expand to other purposes?

Yes, mission creep is a legitimate concern. Once a biometric employment verification system exists, subsequent governments might expand its use to accessing healthcare, claiming benefits, or other services. Preventing this requires specific legislation limiting use to employment verification and strong independent oversight mechanisms. The concerns raised in the public petition reflect this real historical pattern.

What safeguards should exist to protect data privacy in a digital right-to-work system?

Specific legislation should govern which agencies access the system, what data is stored and retained, audit trails for all access, breach notification procedures, independent oversight mechanisms, individual rights to correct errors, penalties for misuse by officials, and clear appeals processes for people incorrectly flagged as unauthorized to work. The current government has not published detailed legislation on these points.

Conclusion

The UK government's decision to scrap the mandatory digital ID requirement while maintaining commitment to digital right-to-work verification by 2029 represents a significant political learning moment. It demonstrates that democratic publics can push back effectively against surveillance initiatives when they perceive genuine threats to privacy and freedom, and that governments will adjust course when faced with sufficient opposition.

But the broader question remains unresolved: how can democracies modernize essential government functions using digital technology while maintaining meaningful privacy protections and preventing surveillance creep? The UK's revised approach offers a partial answer, but success depends on how thoroughly the government addresses outstanding questions about data protection, system access, and long-term governance.

For employers, the transition to digital right-to-work checks by 2029 is now predictable policy. Businesses that start planning now will be better positioned than those waiting until 2028. For privacy advocates, the revised approach removes the most obvious surveillance mechanism while not entirely eliminating concerns about future expansion.

The story of the digital ID proposal—its announcement, the massive public backlash, and the resulting policy reversal—offers lessons for governments worldwide about implementing identity systems in democracies. Promise transparency. Publish specific safeguards. Consult meaningfully with stakeholders. Demonstrate accountability. When you skip these steps and announce major surveillance initiatives as faits accompli, expect resistance.

The next chapters will reveal whether the digital right-to-work system actually succeeds in modernizing employment verification, whether it remains limited to its stated purpose, and whether the government's revised approach successfully balances security with freedom. For now, the backlash has succeeded in forcing the government to reconsider its approach and commit to more limited implementation.

That's meaningful, even if the underlying transformation of employment verification will still proceed.

Key Takeaways

- UK government scrapped mandatory digital ID requirement after nearly 3 million people signed parliamentary petition opposing surveillance infrastructure

- Digital right-to-work verification will still proceed with full transition target of 2029, using biometric passports instead of centralized ID registration

- Original proposal lacked transparency and specific safeguards, triggering public backlash rooted in historical UK skepticism toward government surveillance

- Biometric data security remains critical concern, as compromised biometric identifiers cannot be changed unlike passwords or regular personal information

- Five-year timeline allows employers and government to develop infrastructure, though government IT projects frequently exceed published deadlines

Related Articles

- Internet Censorship Hit Half the World in 2025: What It Means [2026]

- ICE Enforcement Safety Guide: Know Your Rights [2025]

- Minnesota Sues to Stop ICE 'Invasion': Legal Battle Over Operation Metro Surge [2025]

- Right-Wing Influencers Minneapolis ICE: Social Media Propaganda [2025]

- Iran Internet Blackout: What Happened & Why It Matters [2025]

- Instagram Password Reset Incident: What Really Happened [2025]

![UK Scraps Digital ID Requirement for Workers [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/uk-scraps-digital-id-requirement-for-workers-2025/image-1-1768390678334.jpg)