US and China AI Collaboration: The Hidden Partnerships Reshaping AI Research [2025]

You've probably heard the narrative. America and China are locked in an existential struggle for AI supremacy. Tech executives warn Congress about the China threat. Politicians justify trillion-dollar AI investments by invoking the spectre of falling behind Beijing. The framing is simple: we're in a race, and races have winners and losers.

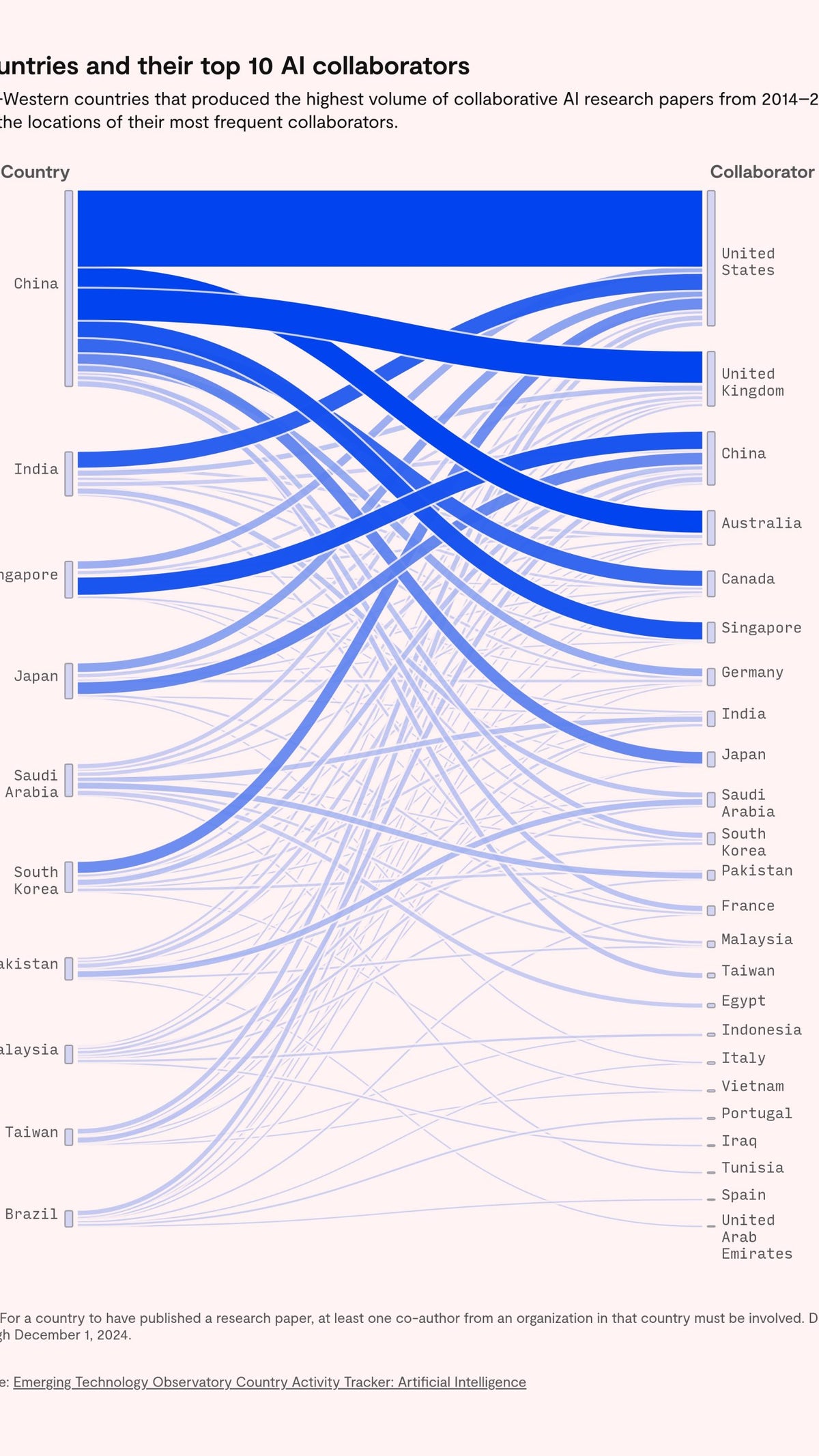

But there's something the headlines don't tell you. Right now, in the highest echelons of artificial intelligence research, American and Chinese scientists are working together. They're publishing papers jointly. They're sharing algorithms. They're building on each other's breakthroughs. And this collaboration is happening at scale.

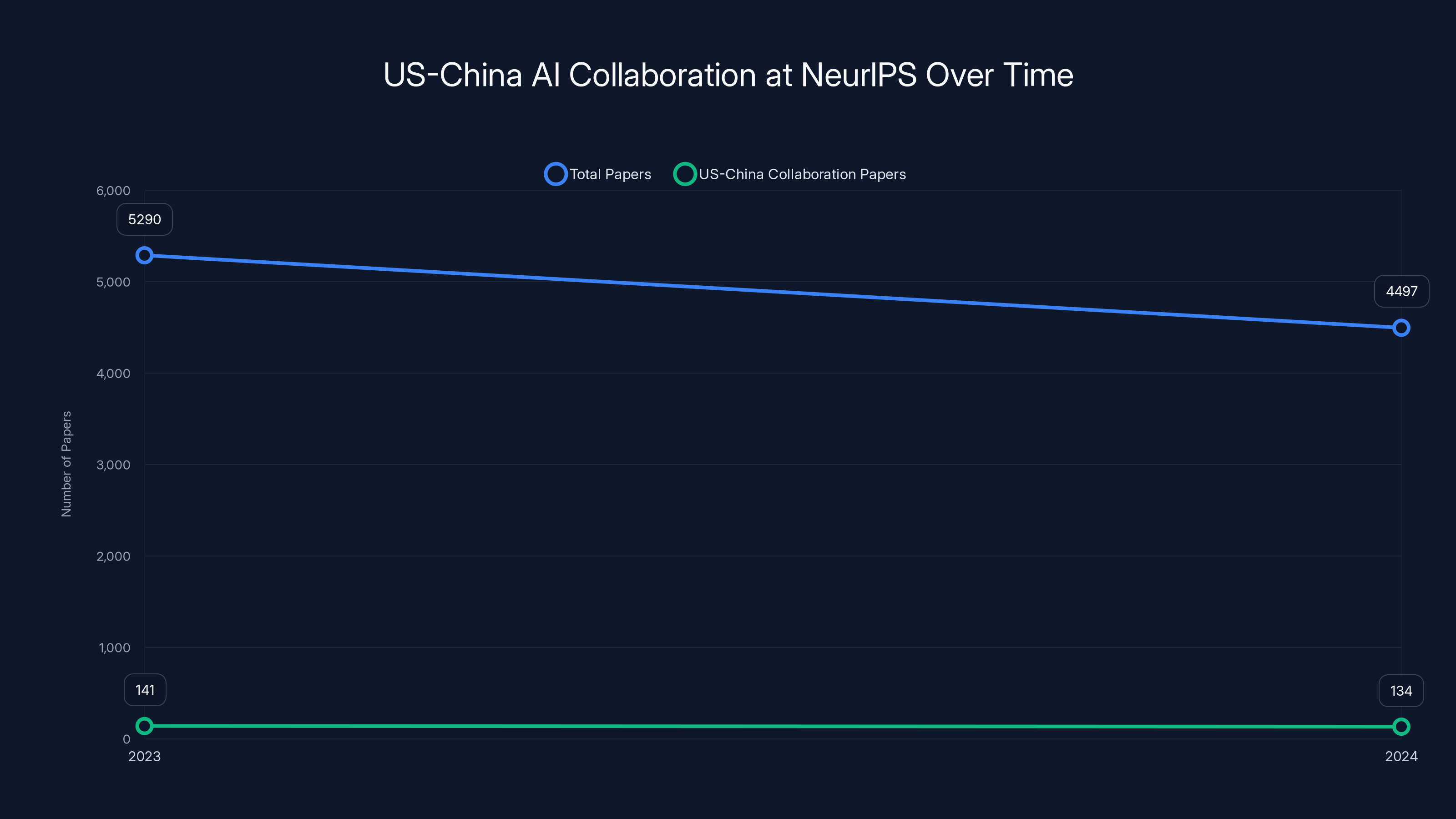

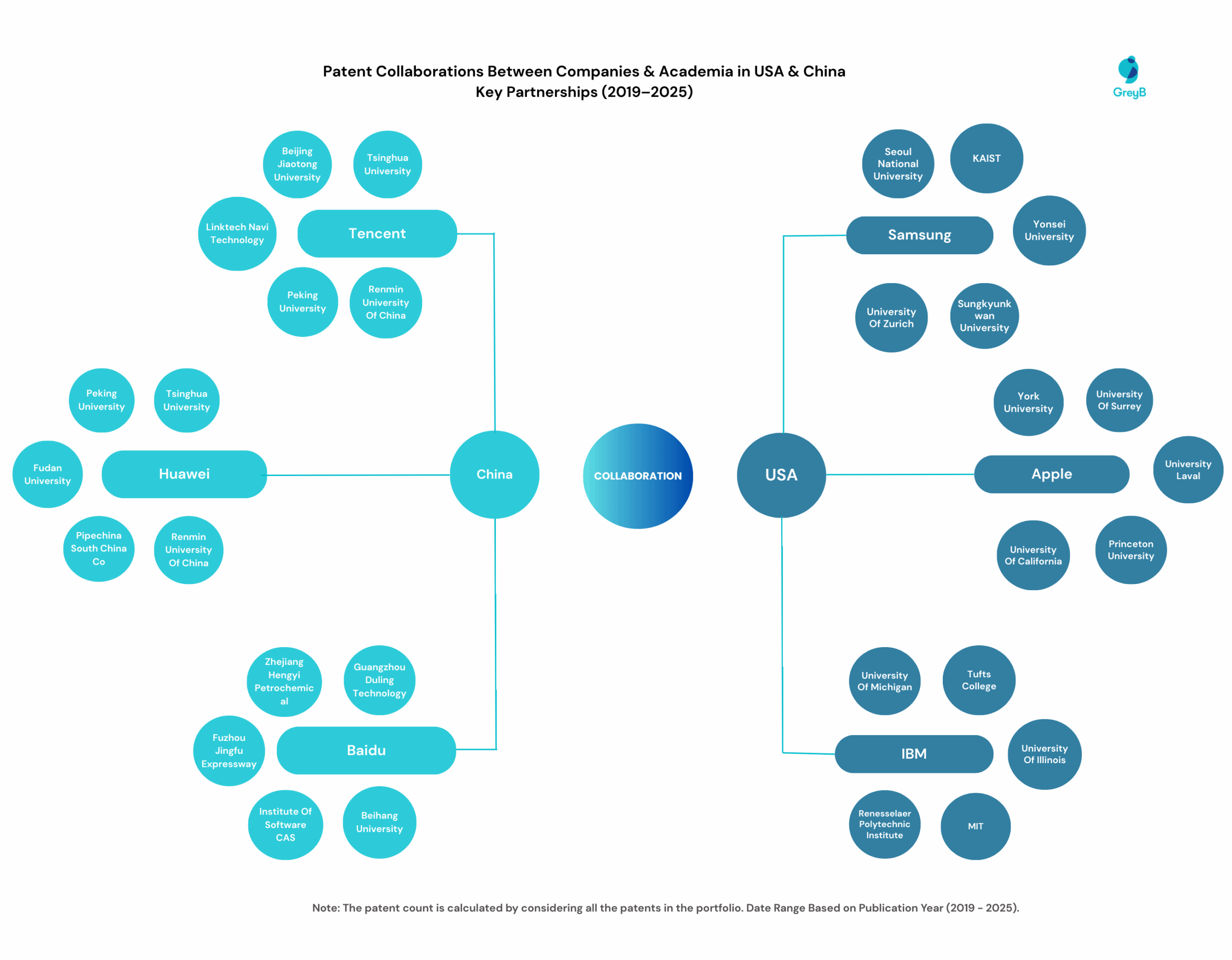

Recent analysis of over 5,000 research papers from Neural Information Processing Systems (Neur IPS), the premier AI conference, reveals something surprising about how the world's two AI superpowers actually operate. Yes, they compete fiercely on commercial applications and computing power. But when it comes to fundamental research, the picture is far more nuanced. About 3 percent of papers at Neur IPS involve authorship from both US and Chinese institutions. That might sound small until you realize it represents hundreds of papers per year written by researchers working across the Pacific.

This isn't just academic navel-gazing. These collaborations shape the foundation of everything that follows in AI. The models being built today, the techniques being discovered now, the algorithms being perfected this month—they flow from international partnerships that most people don't realize exist. Understanding these collaborations matters because they reveal something policymakers often miss: the global nature of modern AI research makes pure competition impossible.

The Scale and Significance of US-China AI Collaboration

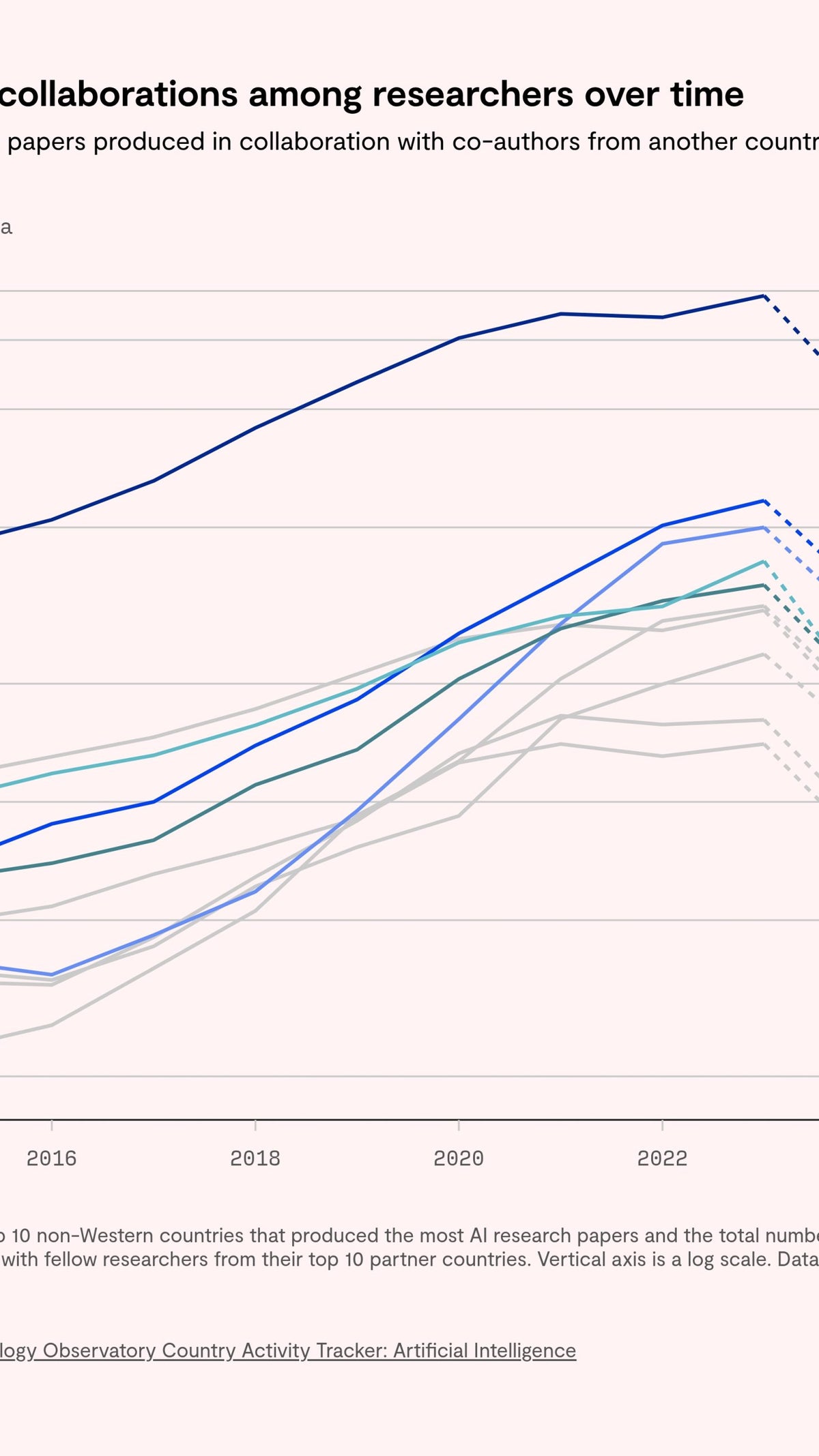

When you dig into the data, the numbers tell a striking story. Out of 5,290 papers presented at a recent Neur IPS conference, 141 involved direct collaboration between authors from US institutions and Chinese institutions. That's roughly 3 percent of all papers at the world's most prestigious AI research conference. According to WIRED's analysis, this collaboration rate has remained stable over the years, indicating structural relationships between research institutions that have weathered trade tensions, investment restrictions, and political rhetoric.

Consider what these numbers represent in practical terms. If you're attending Neur IPS and you randomly walk past 33 presentations, statistically one of them will involve a research team that spans the Pacific. That researcher from MIT might be presenting work co-authored with someone from Tsinghua University in Beijing. That scientist from Stanford might have collaborated with colleagues at Alibaba or Baidu. These aren't fringe outliers. They're mainstream participants in the cutting-edge research ecosystem.

Jeffrey Ding, an assistant professor at George Washington University who specializes in analyzing China's AI landscape, articulated what this collaboration really means: whether policymakers like it or not, the US and Chinese AI ecosystems are deeply intertwined. Both benefit from the arrangement. This isn't sentimentality or wishful thinking. It's practical reality.

The implications cut both ways. Chinese researchers gain access to advanced computing infrastructure at American universities. They participate in the global scientific conversation at the highest level. American researchers, meanwhile, benefit from fresh perspectives, competing ideas, and collaborative problem-solving that accelerates innovation. Neither side gives up much to participate in this exchange. Both gain tremendously.

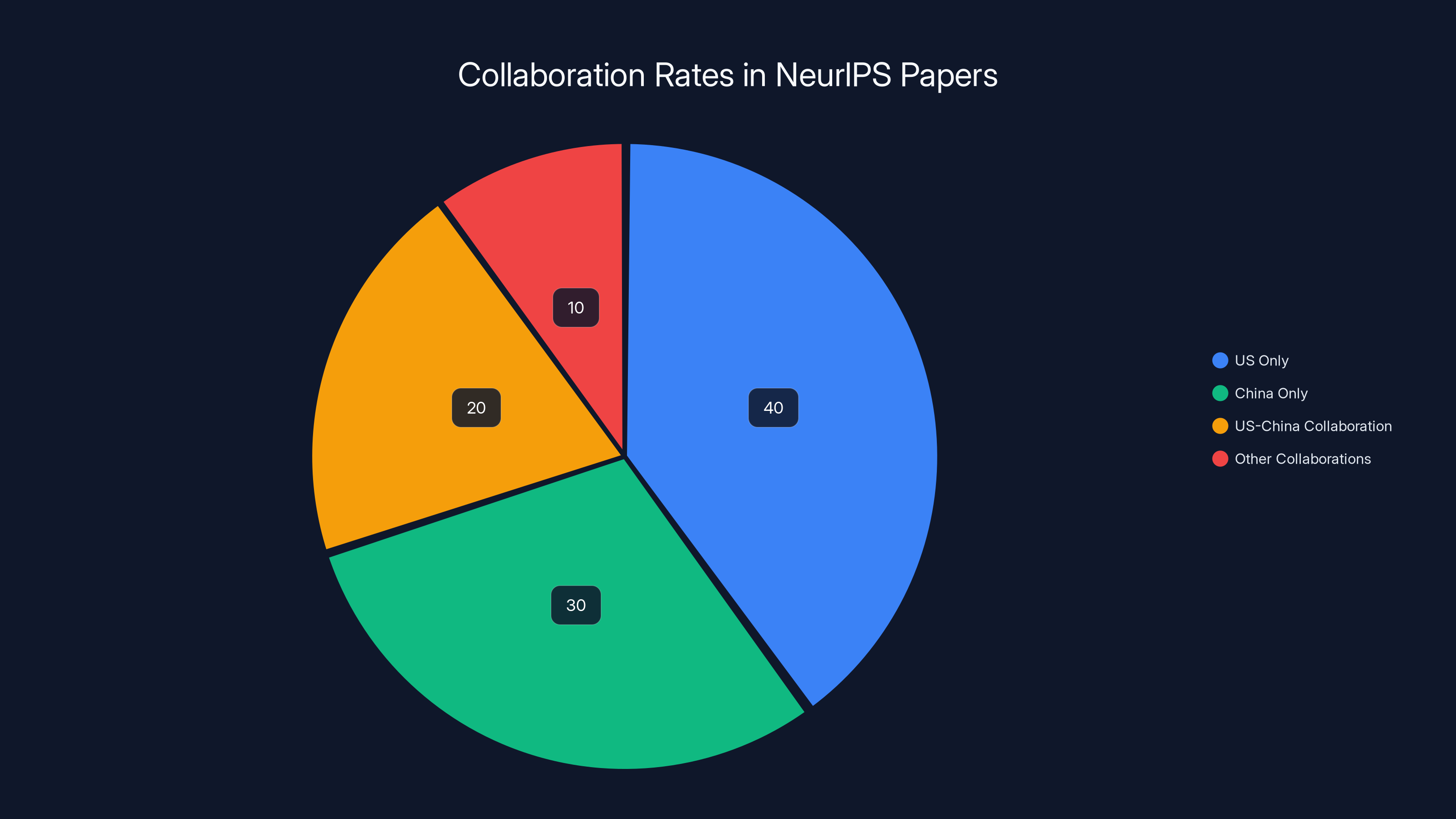

Estimated data shows that 20% of analyzed NeurIPS papers involved collaboration between US and Chinese institutions, highlighting significant international cooperation in AI research.

How Global AI Models Bridge Continents

Beyond direct collaboration between researchers, there's another layer of connection that's equally important: how algorithms and models developed in one country get adopted, adapted, and improved by researchers in another.

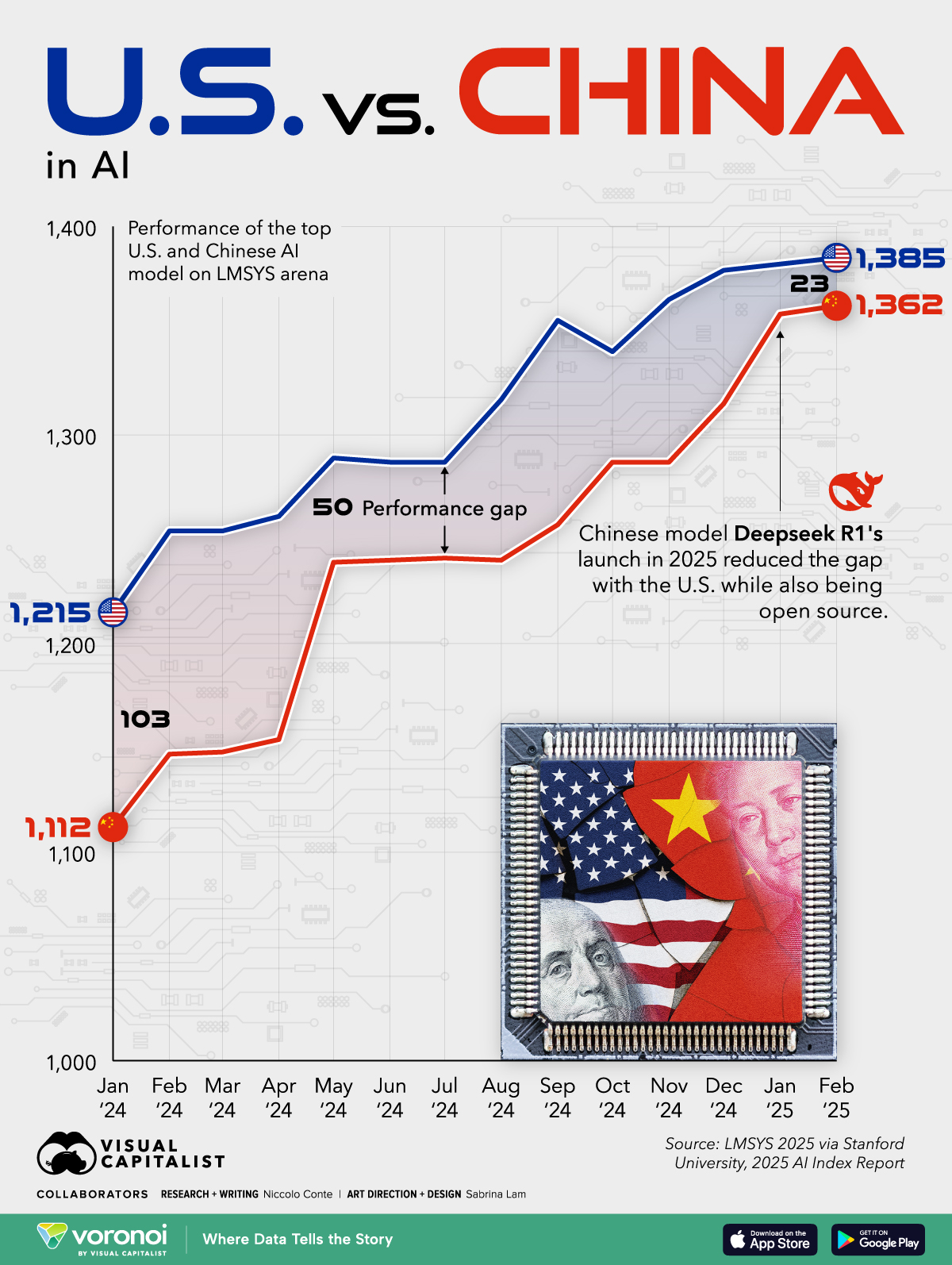

Take the transformer architecture, developed by researchers at Google. This foundational innovation—published in 2017 and now powering nearly every major AI system—appears in 292 Neur IPS papers with Chinese authors. That's hundreds of papers building on, improving, or applying a concept that originated in America. Chinese researchers didn't just read about transformers. They built on them. They experimented with variations. They pushed the boundaries of what transformers could do.

Meanwhile, Meta's Llama family of large language models shows up in 106 papers that include authors from both countries working together. Again, the model originated in the West, but the research community is global. Someone in Beijing might be figuring out how to make Llama more efficient. Someone in Stanford might be using Llama as a foundation to build something novel. The innovation doesn't stop at the company that created it. It spreads. It gets better through distributed effort.

Then there's Qwen, Alibaba's large language model, which is increasingly popular among American researchers. In 63 papers presented at Neur IPS, authors from US organizations are building on Qwen. They're exploring its capabilities. They're testing it against other models. They're publishing results. American researchers aren't locked out of Chinese innovation. They can access it, study it, improve it.

This free flow of models and algorithms represents a massive acceleration in AI capability for the entire field. Imagine if every breakthrough had to stay siloed within national borders. Development would slow dramatically. Instead, we have a system where good ideas spread almost instantly across the Pacific. A university in California sees what worked in Beijing and builds on it. A lab in Shanghai reads about a novel technique from MIT and adapts it to their own research.

This arrangement benefits everyone in the global AI ecosystem. It accelerates progress. It prevents redundant research. It allows smaller research teams to build on work done by larger institutions thousands of miles away. The internet made this possible. Academic culture made it normal. And economic incentives (the desire to publish in top venues, to gain citations, to influence the field) made it inevitable.

The US-China collaboration in AI research papers at NeurIPS has remained stable, with around 3% of total papers involving collaboration between the two countries from 2023 to 2024.

The Hidden Pipeline: Chinese-Born Researchers in America

Understanding US-China AI collaboration requires understanding one crucial fact that often gets glossed over in geopolitical analysis: many researchers working in America were born in China. Many researchers working in China were educated in America. The people are the pipeline.

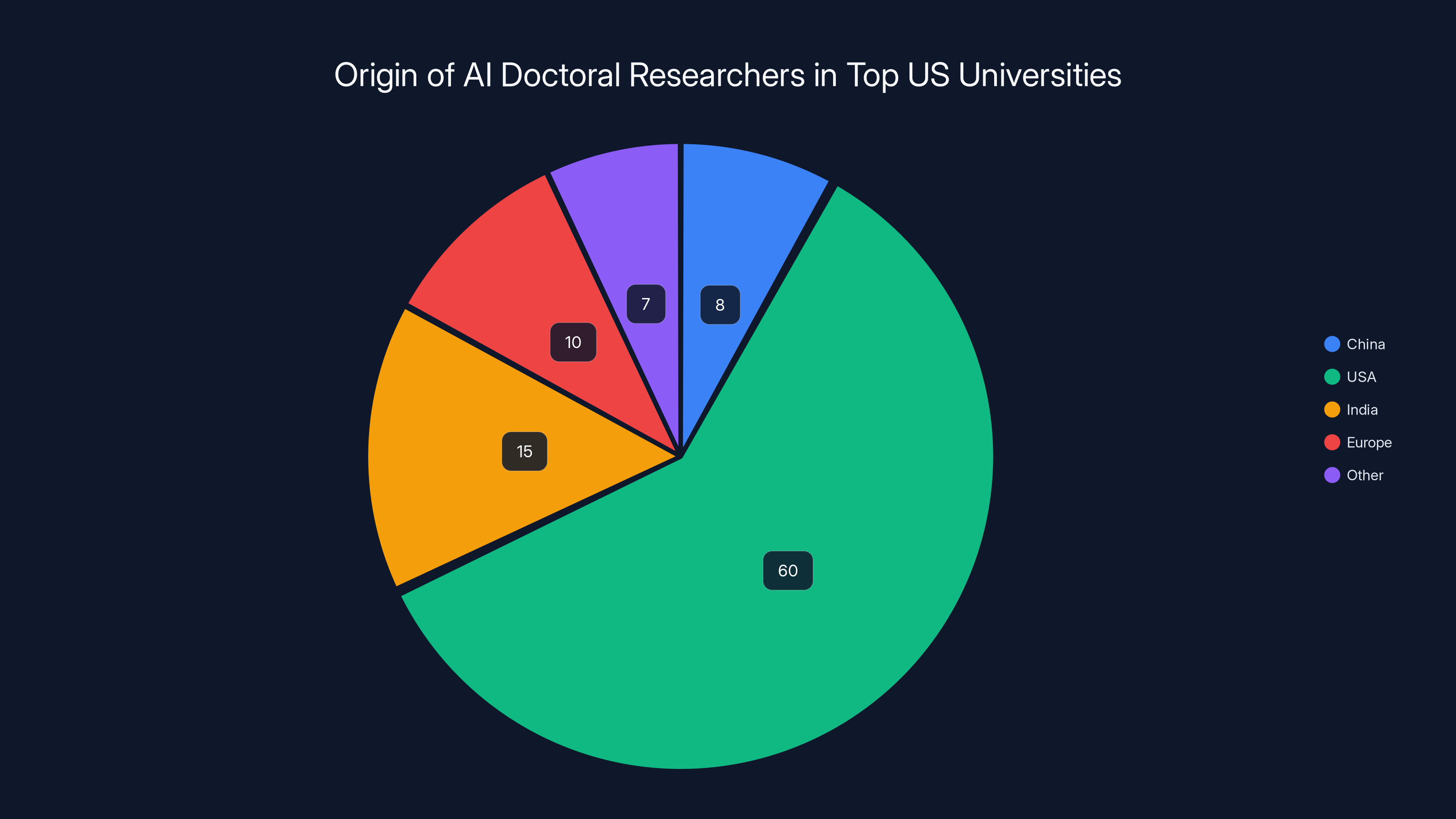

Estimates suggest that roughly 8 percent of doctoral researchers in AI at top American universities were born in China. Some came to the US for undergraduate education. Others arrived for graduate school. Many stayed. Many moved back. Many maintain relationships spanning both countries throughout their careers.

These relationships matter enormously. A researcher who completed their PhD at Carnegie Mellon, supervised by an American professor, stays in touch with that advisor for years. They collaborate on papers. They exchange ideas. They recommend students to each other. The formal collaboration structures—the co-authored papers—are the visible artifacts of relationships that began years earlier, in classrooms and laboratories across America.

Katherine Gorman, a spokesperson for Neur IPS itself, pointed out something crucial: collaborations between students and advisors often continue long after the student has left their university. These bonds persist. They transcend borders. They outlast policy changes. A Chinese researcher who studied at Stanford in 2015, returned to work at Alibaba in 2018, might still be collaborating with their Stanford advisor in 2025. Those relationships show up in co-authored papers. They influence research directions. They shape what problems get studied and how they get approached.

There's also another dimension: brain circulation rather than pure brain drain. Some researchers move back and forth. A brilliant computer scientist might spend five years in the US, then return to China to lead research at a top tech company, while maintaining relationships with American collaborators. These aren't failures of American immigration policy. They're features of a global research ecosystem where talent moves to where the opportunity is.

The question policymakers face is whether they should restrict this movement. Should they make it harder for Chinese researchers to attend American universities? Should they limit collaboration? The cost of such restrictions would be felt immediately in American research institutions, which rely on this talent pipeline to remain competitive. It would slow innovation. It would reduce the quality of research. And based on evidence from WIRED's analysis, it would break apart collaborations that are currently advancing the field.

The Architecture of International AI Collaboration

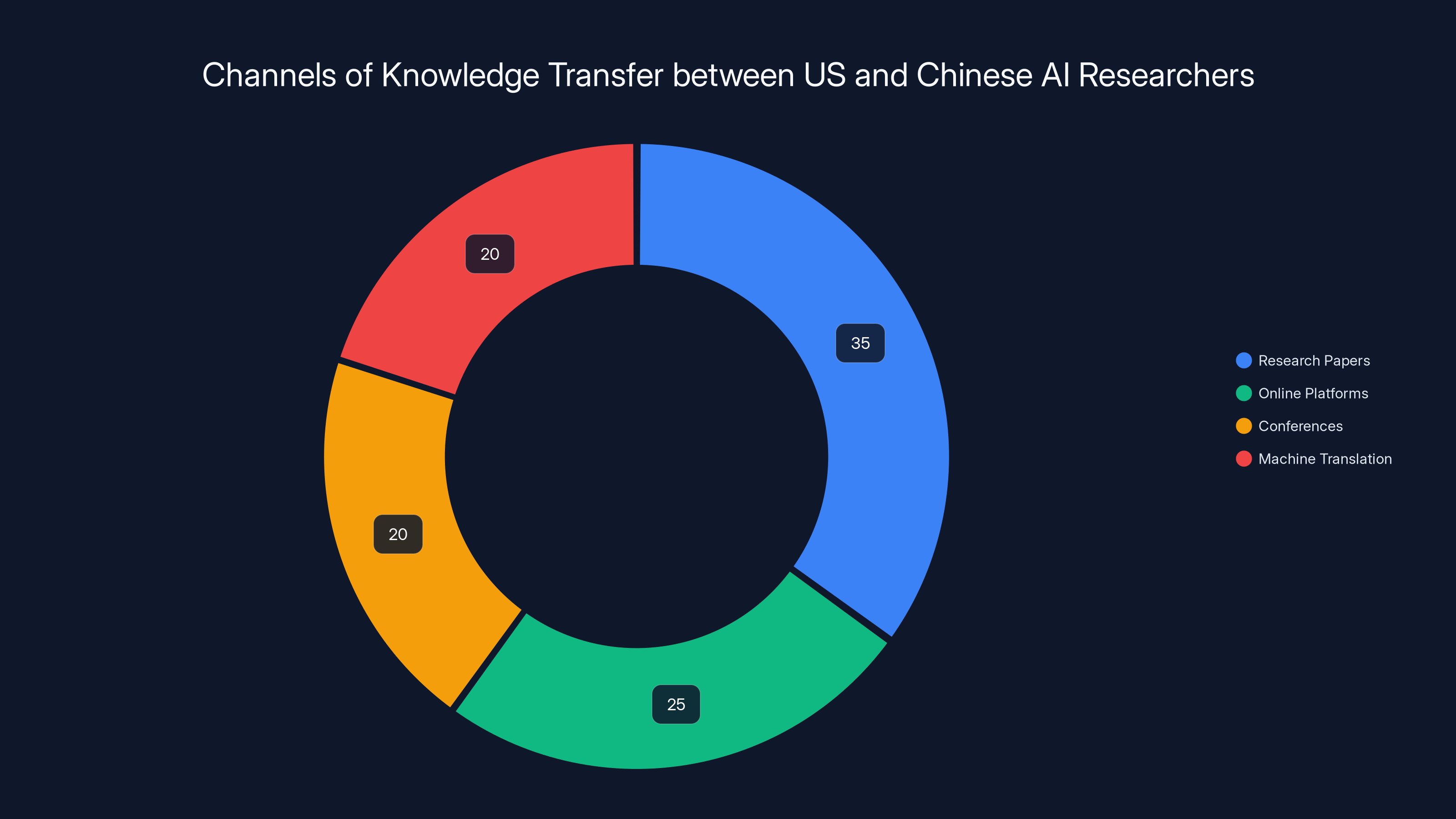

Collaboration between US and Chinese researchers happens through several distinct channels, each with different incentive structures and different implications for policy.

First, there's the conference system. Neur IPS, ICML, ICCV—these conferences bring researchers together annually. They present cutting-edge work. They network. They form collaborations. A researcher from Tsinghua University presents a paper. They meet someone from Berkeley. They discover they're working on related problems. A collaboration begins. Within a year, they're co-authoring papers. This happens thousands of times per year across the AI research community.

Second, there's the journal publication system. Researchers submit papers to venues like JMLR or arXiv. When they cite interesting work, they often reach out to authors. These communications sometimes develop into collaborations. The peer review process itself creates connections. A researcher in Beijing peer reviews a paper from Stanford. They provide feedback. They suggest improvements. If the paper is accepted, they might follow up with the authors. A relationship begins.

Third, there are institutional partnerships. Some American universities have agreements with Chinese universities for student exchange and collaborative research. Some tech companies have research offices in both countries that coordinate work. These formal structures enable systematic collaboration rather than random connections.

Fourth, there's the open-source ecosystem. A researcher in California releases code on GitHub. A researcher in Shanghai uses it, improves it, contributes changes back. No formal collaboration is necessary. The work is collaborative by design. This is probably the most resilient form of collaboration because it requires almost no institutional or political support. It's just scientists helping scientists.

Each channel has different robustness to policy changes. The open-source channel is hardest to shut down. The institutional partnership channel is most vulnerable. The conference channel has moderate vulnerability. Understanding these different channels is crucial for policymakers who want to shape collaboration without accidentally destroying it.

Estimated data shows that 8% of AI doctoral researchers at top US universities were born in China, highlighting significant international collaboration in AI research.

When Models Cross the Pacific: Case Studies in Shared Innovation

Let's look at specific examples of how models and ideas flow between countries and what that tells us about the real structure of AI collaboration.

The transformer architecture is the most foundational example. Developed by Google researchers and published in a paper titled "Attention is All You Need," it represented a conceptual breakthrough that transformed the field. The architecture didn't stay at Google. Within months, it spread globally. Researchers everywhere started implementing it, testing it, improving it. Chinese universities adopted it. Chinese tech companies built on it. Today, you can't understand modern AI without understanding transformers, and that understanding is truly global.

What's remarkable is that the original transformer paper had broad appeal because it was published open-access and the ideas were accessible to anyone with basic machine learning knowledge. The authors didn't restrict access. They didn't require permissions. The idea spread because it was good, because it was published in the right venue, and because the global research community immediately recognized its significance.

Llama tells a different story. Meta released Llama models, initially with academic-only license terms. Despite the restrictions, researchers worldwide found ways to work with the models. Chinese researchers adapted Llama. They built on it. They published results. Meta's business strategy was to restrict commercial use while allowing research use. As a practical matter, this enabled enormous global collaboration because the research community is where the innovation happens before commercialization.

Qwen, Alibaba's large language model, shows the reverse flow. A Chinese tech company developed a competitive large language model. American researchers studied it. They compared it to other models. They used it as a foundation for their own research. American papers on Qwen mean American researchers are tracking Chinese progress, learning from it, and potentially building on it. The knowledge flows in both directions.

These model flows reveal something important: the best models escape their national origins. They become global tools. They're too useful to ignore. The researchers who ignore them would handicap themselves relative to researchers who use them. So everyone uses them. That creates a leveling effect where ideas and innovations spread globally remarkably fast.

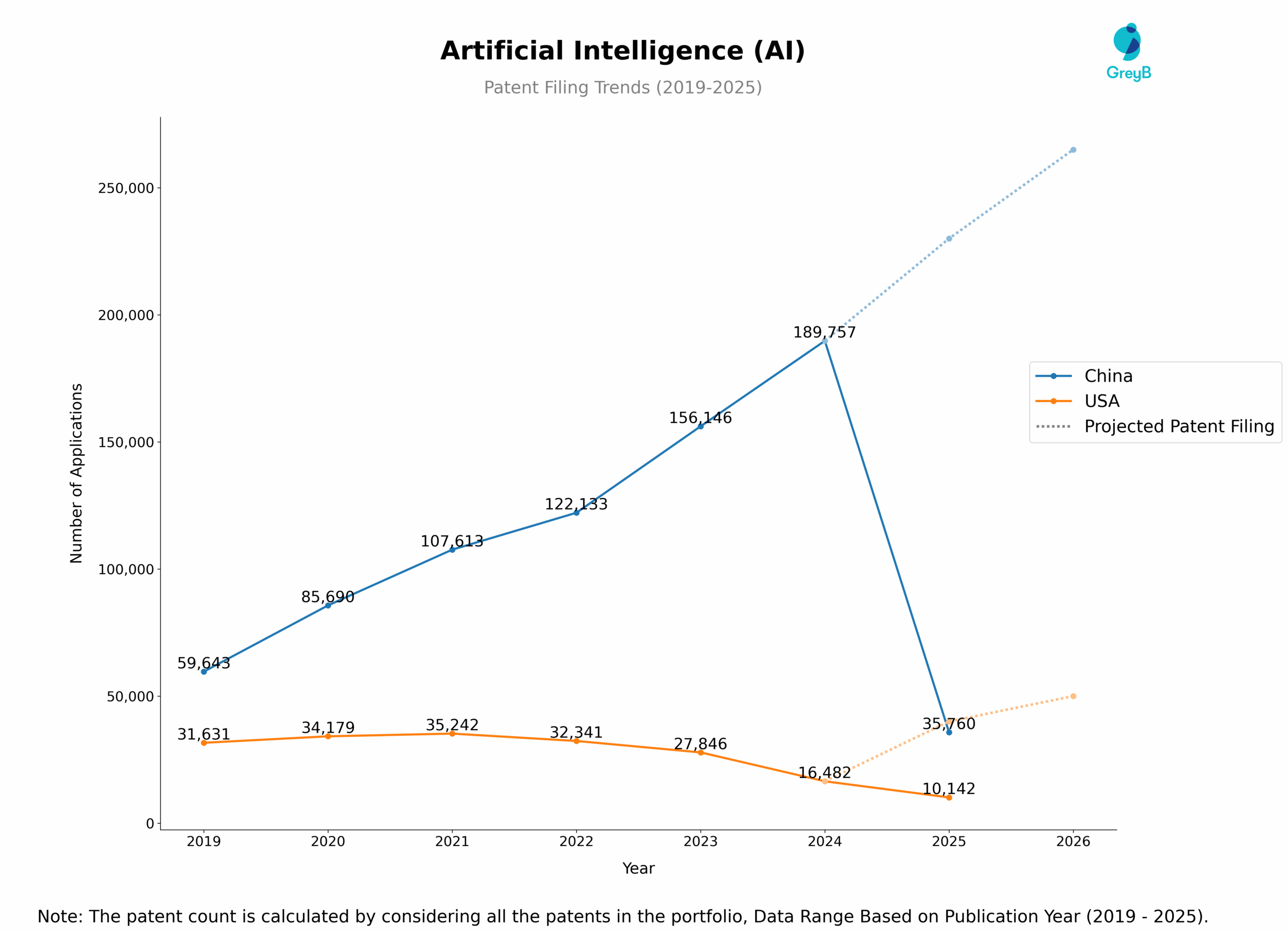

The Geopolitical Context: Why This Matters Right Now

The timing of WIRED's analysis is significant. It emerged during a period of intensifying geopolitical tension between the US and China. Policy discussions at the highest levels of government have focused on restricting technology transfer. Tech executives have testified before Congress about the need to prevent China from accessing advanced AI capabilities. There's been talk of export controls, visa restrictions, and research limitations.

Against this backdrop, the evidence of substantial ongoing collaboration is striking. It suggests that the competitive narrative, while not wrong, is incomplete. Competition and collaboration are happening simultaneously. They're not mutually exclusive. In fact, they're deeply intertwined.

Think about it from the perspective of a researcher. Your incentive to publish good work is massive. You want your research to be cited. You want to contribute to the field. You want to be known as someone who solved important problems. Collaboration with the smartest people, regardless of national origin, advances those goals. Restricting collaboration would slow your work.

This creates a fundamental tension between national security concerns and scientific progress. Policymakers worry about China obtaining advanced capabilities. Scientists want to collaborate with the smartest people globally. Those goals are in conflict.

Jeffrey Ding's observation captures this tension perfectly. The ecosystems are enmeshed. You can't easily disentangle them without breaking something. Both sides benefit from the arrangement. That doesn't mean the arrangement is permanent or that policy can't change it. It just means changing it would be costly.

There's also a question about whether the zero-sum framing is even accurate. If American researchers collaborating with Chinese researchers produces better science, who wins? In some sense, the global AI research community wins. But nations benefit differently from that global progress depending on their capacity to commercialize and deploy innovations. The US has strong commercial infrastructure for AI. China does too. Both benefit from better fundamental science, but they benefit in different ways.

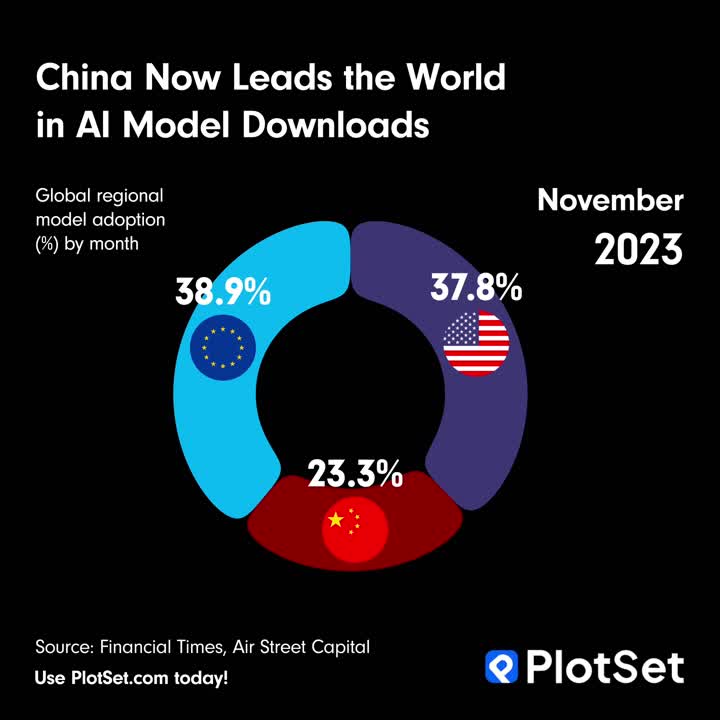

Research papers account for the largest share of knowledge transfer, followed by online platforms, conferences, and machine translation. Estimated data reflects the diverse channels facilitating global AI collaboration.

The Neur IPS Analysis Methodology: How WIRED Analyzed 5,000+ Papers

Understanding how WIRED arrived at these conclusions matters for assessing how reliable the data is. The methodology reveals both the power and the limitations of using AI tools to analyze large datasets.

WIRED used Open AI's Codex, an AI model trained on code, to help analyze papers. The researchers first downloaded all papers from a recent Neur IPS conference. Then they used Codex to write scripts that would examine each paper's author affiliations and identify which papers involved authors from both US and Chinese institutions.

This approach was novel because it automated something that would normally require human labor. Reading through 5,000 papers manually and tracking author affiliations would take weeks or months. Using AI to do this analysis compressed the timeline dramatically. But it also introduced considerations about accuracy.

The researchers were careful about this. They didn't just trust Codex to do the analysis and report the numbers. They built in verification steps. They manually checked results. They tested different approaches. When Codex made mistakes—and it did—they identified them and adjusted the analysis.

This is an important lesson about using AI for research. These tools are powerful. They can automate tedious work. But they're also fallible. They make "surprisingly stupid mistakes," as the analysis noted, even when they're being quite smart about other things. The key is not to trust them blindly but to build verification into your process.

The analysis revealed that the AI tools, when combined with human oversight, could perform useful research at scale. The specific statistics about collaboration rates came from this hybrid human-AI process. That doesn't mean the numbers are perfectly precise. There could be edge cases. There might be missed affiliations or false positives. But the numbers are likely directionally accurate. They're reliable enough to suggest real patterns.

Implications for US AI Policy and Competitiveness

If you're a policymaker focused on American AI leadership, how should you think about this evidence of collaboration? The analysis suggests several important considerations.

First, the current level of collaboration isn't a sign of weakness. It's evidence that the US is central to global AI research. Chinese researchers want to collaborate with American institutions because American universities and companies are where cutting-edge work happens. That's a competitive advantage, not a liability. If you restrict this collaboration, you reduce the attractiveness of American research institutions and diminish your soft power in the global research community.

Second, collaboration has historically accelerated American innovation. The tech industry was built partly by immigrants and international talent. Silicon Valley's success depended on people from everywhere bringing ideas and energy. The same dynamics apply to AI. American AI leadership benefits from attracting global talent and maintaining collaborative relationships with researchers worldwide.

Third, restricting collaboration might not achieve the security goals it's intended to achieve. If the concern is preventing China from obtaining advanced AI capabilities, the real lever is commercial technology, computing power, and specialized chips. Fundamental research papers are published openly. Models get released. You can't keep ideas secret in an open scientific community. What you can do is make sure your own capabilities are ahead of everyone else's. That requires accelerating your own innovation, not slowing everyone else's.

Fourth, there are legitimate security concerns that don't require destroying collaboration. Specific sensitive work on certain applications might reasonably be restricted. But blanket restrictions on international collaboration would damage the research ecosystem without effectively addressing the underlying security concerns.

The evidence from WIRED's analysis suggests a nuanced policy approach: maintain and encourage fundamental AI research collaboration while being more protective of commercial applications and sensitive dual-use technologies. That distinction is crucial and often lost in policy discussions that treat all AI as equally sensitive.

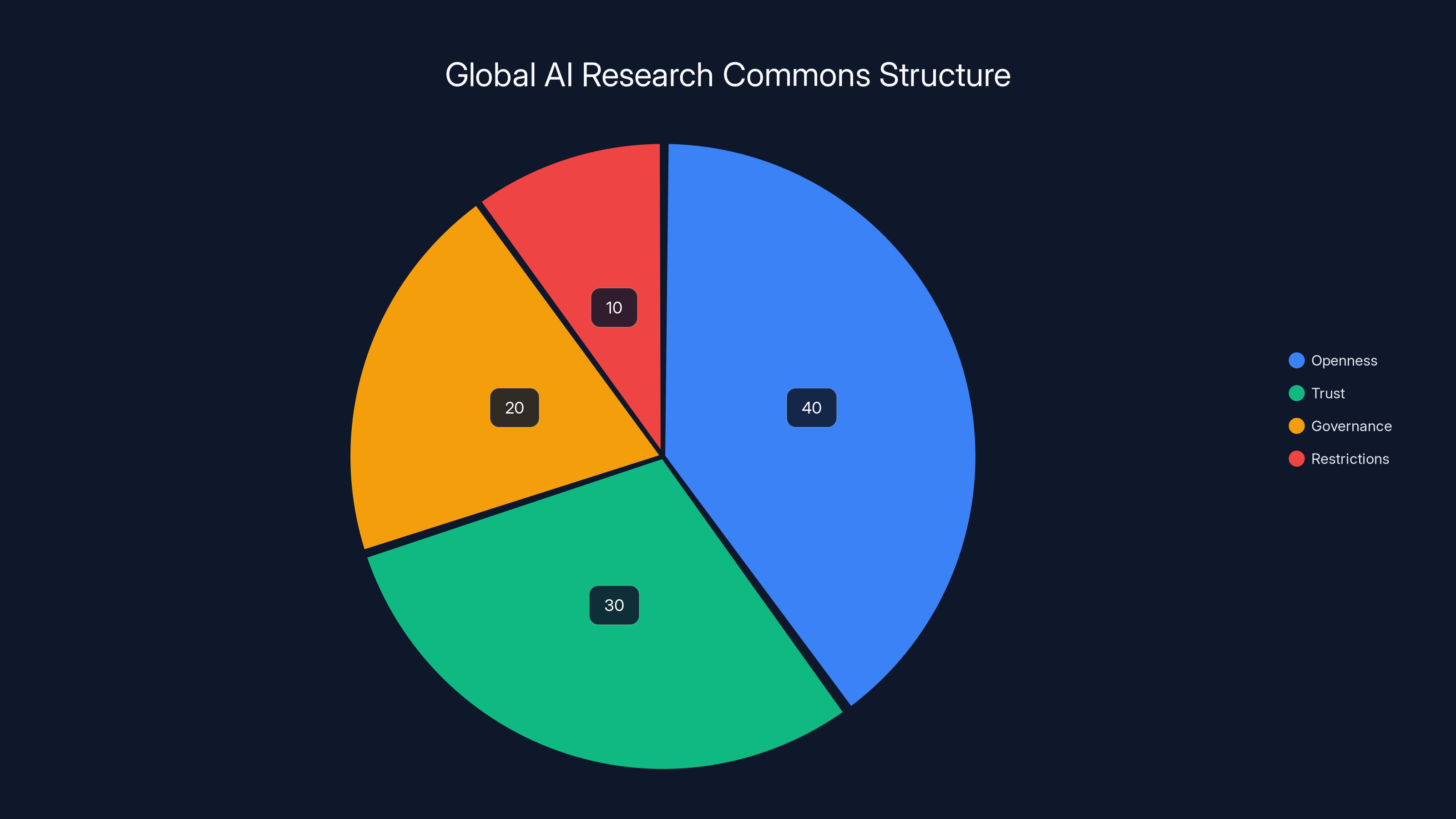

Estimated data shows that openness (40%) and trust (30%) are key factors in maintaining the global AI research commons, with governance (20%) and restrictions (10%) also playing roles.

The Role of International Conferences in Enabling Collaboration

Neur IPS is more than just a conference. It's the central meeting point for the global AI research community. Understanding its role illuminates how international collaboration actually works in practice.

Every year, roughly 15,000 researchers from around the world converge. They present papers. They discuss ideas. They network. They form collaborations. The conference is explicitly designed to be international. There's no preference for American researchers or American institutions. Good research gets accepted regardless of origin.

This openness is partly ideological—there's a genuine belief in the international scientific community that good ideas should spread and that collaboration accelerates progress. But it's also practical. If Neur IPS only accepted American researchers, it would diminish the quality of the conference. Some of the best work would be excluded. The conference's prestige depends on being truly international.

That same logic applies to other major AI conferences. ICML, ICCV, AAAI—they're all international venues. They all depend on global participation. They all enable collaboration between researchers from different countries.

Policymakers could theoretically restrict American researchers from attending these conferences or ban foreign researchers from presenting at American conferences. In fact, some countries have considered this. But the cost would be high. American researchers would be isolated from the global conversation. They'd lose opportunities to collaborate with the smartest people on the planet. They'd sacrifice influence in shaping the research agenda.

So conferences remain open. Collaboration continues. And this openness is probably the single biggest factor enabling the kind of research partnerships that WIRED's analysis documented.

Data Flows and Knowledge Transfer: The Hidden Channels

Beyond direct collaboration and model sharing, there are other ways that knowledge flows between US and Chinese AI researchers. These flows are harder to measure but potentially more significant.

When a Chinese researcher reads an American paper, they're not just passively consuming information. They're understanding the problem-solving approach. They're learning the techniques. They're absorbing the intuitions. When they apply that knowledge to their own work, they're participating in knowledge transfer. This happens billions of times across the research ecosystem.

Online platforms amplify this. GitHub hosts code. arXiv hosts papers. Medium hosts blog posts. These are global repositories. A researcher in Shanghai can access the latest code from Berkeley. A researcher in Beijing can read technical blog posts from San Francisco. They can use these resources, build on them, improve them.

Machine translation is another channel. Papers published in Chinese can be understood by non-Chinese speakers. Papers published in English can be translated for Chinese audiences. Language barriers, which once limited knowledge flow, are diminishing thanks to increasingly capable translation tools.

Conferences generate other flows. When a Chinese researcher attends Neur IPS, they see what problems American researchers are working on. They observe which approaches people are excited about. They learn about funding opportunities and research directions. They return to China with insights that influence their own work.

These flows are bidirectional. American researchers learn from Chinese work too. They see different approaches to problems. They learn about different research directions. Huawei, Alibaba, Baidu, Tencent—these companies publish research. Their innovations become visible to the global community. American researchers benefit from that visibility.

The net effect is a global brain that's more capable than any individual national brain could be. Problems get solved faster. Solutions get better. The pace of innovation accelerates. Everyone benefits, though they benefit in different ways depending on their position in the ecosystem.

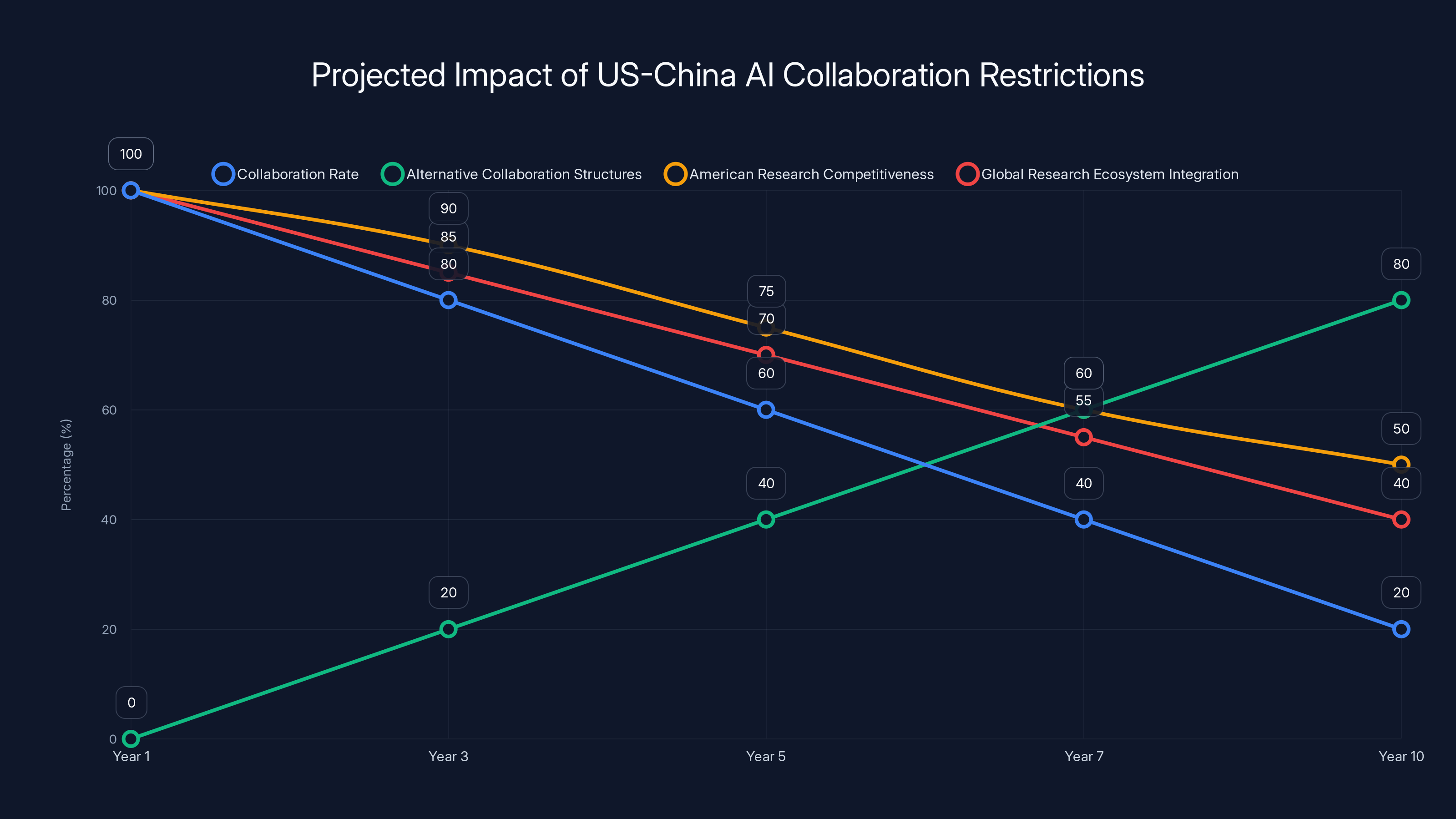

Estimated data shows a decline in direct collaboration and competitiveness over 10 years, with a rise in alternative collaboration methods.

The Economics of AI Collaboration: Why It Makes Sense

From a purely economic perspective, collaboration makes sense for both sides. That's why it persists despite political pressure against it.

For Chinese researchers, collaboration with American institutions offers several advantages. It provides access to computing resources, expensive equipment, and datasets that might not be available domestically. It provides prestige—a paper published at Neur IPS or accepted to a top journal carries weight globally. It provides access to funding and career opportunities. A researcher who publishes with American collaborators becomes more valuable in the job market.

For American researchers and institutions, the benefits are also clear. Chinese researchers bring talent and perspectives. They solve problems faster with more hands working on them. American universities benefit from the prestige of hosting international collaborators. American companies benefit from research partnerships that accelerate their own development.

Both sides also benefit from the knowledge transfer itself. Problems that seemed intractable might yield to a Chinese researcher's approach. Techniques developed in Beijing might unlock breakthroughs in California. The diversity of approaches accelerates overall progress.

This is fundamentally different from commercial competition, where one side's gain is the other side's loss. In fundamental research, both sides can win simultaneously. Better science helps everyone. That's why collaboration persists despite other frictions.

Restrictions and Their Likely Effects: What Policy Changes Would Mean

If policymakers decided to restrict US-China AI collaboration, what would actually happen? Understanding the likely effects matters for evaluating whether such restrictions make sense.

First, direct collaboration would decrease. If American universities were prohibited from having Chinese students in AI programs, collaboration rates would fall. But the effect wouldn't be instantaneous. Researchers who are already collaborating would continue doing so for a time. New collaborations would be harder to form. Over five to ten years, the collaboration network would shrink.

Second, alternative collaboration structures would emerge. Researchers have strong incentives to collaborate. If direct collaboration becomes difficult, they'd use indirect methods. They'd present work at international conferences in third countries. They'd collaborate through researchers in neutral countries. They'd use intermediaries. The collaboration would become less visible but wouldn't disappear entirely.

Third, American research institutions would lose competitiveness. If the best research talent from China can't access American universities, American universities become less attractive. Top researchers would seek positions elsewhere. Graduate programs would be less strong. The prestige and competitiveness of American research would diminish.

Fourth, the global research ecosystem would fragment. Instead of one integrated community, you'd have separate American and Chinese research communities with reduced communication. Both would innovate more slowly because they'd lose the cross-pollination benefits.

Fifth, China might retaliate with its own restrictions. If American researchers can't collaborate with Chinese researchers, the collaboration ends from both sides. American researchers lose access to Chinese insights and research. The benefit of collaboration disappears for everyone.

These effects suggest that heavy-handed restrictions would be costly. That doesn't mean all restrictions are bad. Restricting specific sensitive research or specific export controls might make sense. But broad restrictions on collaboration would have broad costs.

The Future of US-China AI Collaboration: Predictions and Uncertainties

What happens to collaboration over the next five to ten years depends partly on choices that haven't been made yet. The trajectory isn't predetermined.

One scenario is that collaboration continues at current levels. Research communities remain integrated. Students move back and forth. Researchers collaborate across borders. Innovation proceeds at current pace. This seems stable because both sides benefit and there are institutional reasons (conferences, journals, universities) that support this structure.

Another scenario is that restrictions increase. Visa policies become more restrictive. Some types of collaboration are prohibited. Technology transfer gets controlled more tightly. Collaboration rates decline. This would be costly for innovation globally but might address some security concerns. It would also likely trigger Chinese retaliation, making the situation symmetric.

A third scenario is bifurcation: some collaboration continues in basic research while other collaboration gets restricted in sensitive areas. This would preserve some benefits while addressing some security concerns. It requires fine-grained policy that distinguishes between different types of work, which is harder to implement than blanket restrictions or no restrictions.

My assessment is that significant restrictions are unlikely in the next 2-3 years because the costs would become immediately visible. American researchers would protest. Universities would lose revenue. The research community would push back. But 5-10 year trends are harder to predict. Political pressure could shift. New events could change the calculus.

The evidence from WIRED's analysis suggests that collaboration is deeply embedded in how research actually works. It's not a policy choice that can be flipped on and off easily. It's structural. Changing it would require sustained effort and would have persistent costs. That might still be worth doing if the security benefits were large enough. But the decision shouldn't be made under the assumption that costs would be small.

Competitive vs. Collaborative Dynamics: Both Are Real

There's no contradiction between collaboration at the research level and competition at the commercial level. Both are real. Both are happening right now. Understanding this is key to making good policy.

Competition is obvious and visible. Chinese tech companies are developing large language models. American companies are doing the same. They're racing to beat each other. They're protecting intellectual property. They're fighting for market share. That's competition.

Collaboration is less visible but equally real. Researchers at these same companies collaborate with academics. Academic researchers collaborate with each other. Ideas get shared. Work gets built on collectively. That's collaboration.

These aren't mutually exclusive. A researcher at Google could be competing fiercely with Alibaba on large language models while simultaneously co-authoring papers with researchers at Alibaba. The competition is at the commercial product level. The collaboration is at the research level.

This layering of competition and collaboration is actually healthy for innovation. It creates incentives to stay ahead (competition) while maintaining access to the best ideas (collaboration). Neither side wants to give up either dynamic.

Policymakers often fail to appreciate this duality. They see competition and assume collaboration is harmful. They see collaboration and assume competition is impossible. In reality, many sectors (pharmaceuticals, aerospace, semiconductors) operate with both competition and collaboration simultaneously. The trick is managing the boundary—deciding which things are competitive and which are collaborative.

What the Data Actually Tells Us: Nuance Beyond Headlines

The core finding from WIRED's analysis is that roughly 3 percent of Neur IPS papers involve US-China collaboration. That's the headline. But what does it actually mean?

It means collaboration is significant but not dominant. Most research papers don't involve cross-border collaboration. Most researchers work primarily with colleagues in their own country. But a meaningful portion—roughly 3 percent—do work across borders. That's a sizable number of papers, sizable number of collaborations, and sizable influence on the research agenda.

It also means collaboration is consistent. The rate hasn't spiked recently. It hasn't collapsed. It's remained fairly stable. That suggests it's not reactive to immediate events but rather a structural feature of how research works.

It also reveals that American models and frameworks are heavily used by Chinese researchers, and Chinese work is increasingly studied by American researchers. The flows are bidirectional but unequal. American fundamental research seems to have more global reach currently. But that could change.

Finally, it shows that talent flow and long-term relationships matter enormously. The collaborations aren't random pairings of anonymous researchers. They're often between people who have prior relationships, studied together, or trained in the same field. These relationships take years to build and have staying power.

All of this suggests collaboration is robust but not unbreakable. It would survive some policy changes. But heavy-handed restrictions would damage it. The question is whether the security benefits would justify the damage.

Implications for Researchers, Companies, and Institutions

Different stakeholders need to think about US-China collaboration through different lenses.

For researchers, the implication is that collaboration is valuable and should be pursued where possible. Restrictions make work harder but don't make it impossible. Researchers adapt. They find ways to work together even when official channels become constrained. The incentive to collaborate remains strong because better science comes from diverse teams.

For universities, the implication is that international programs and recruiting matter enormously for research quality. A university that can attract researchers from everywhere will do better science than one that can't. If restrictions limit international recruiting, universities should advocate for exceptions in their fields. Their competitiveness depends on it.

For companies, the implication is more complex. Research collaboration helps companies stay ahead of the curve on fundamental advances. But there are legitimate concerns about sharing sensitive technology or capabilities. Companies should distinguish between research collaboration (generally beneficial) and technology transfer of commercial products (appropriately more restricted).

For governments, the implication is that blanket restrictions would be costly. More targeted approaches that protect genuinely sensitive information while preserving beneficial collaboration would work better. But implementing those distinctions requires sophisticated policy that's harder to design and harder to enforce than simple rules.

The Bigger Picture: Global AI Research as a Commons

Zoom out from the specific data about collaboration rates and model sharing. What's the bigger picture?

Global AI research is functioning as a commons. It's a shared resource that researchers worldwide draw on and contribute to. Papers get published openly. Models get released. Code gets shared. Knowledge flows freely. Yes, there are restrictions at the margins (some proprietary work, some export controls, some visa limitations). But the core structure is open and shared.

This commons accelerates innovation for everyone. Problems get solved faster. Solutions get better. The pace of progress increases. That benefits researchers in all countries, companies in all countries, and ultimately societies everywhere.

Maintaining commons requires certain conditions. It requires openness—people need to be able to share work without excessive restrictions. It requires trust—people need to believe others are acting in good faith. It requires legitimate governance—norms and rules that everyone agrees on. AI research currently has these conditions, though they're under pressure.

If those conditions break down—if openness becomes restricted, if trust erodes, if governance becomes arbitrary—the commons collapses. Researchers retreat to national silos. Innovation slows. Everyone loses. That's not hypothetical. It's happened in other domains. The question is whether it will happen in AI.

The evidence from WIRED's analysis suggests that researchers still have strong incentives to maintain the commons. They're still collaborating despite political pressure. They're still sharing work. They're still building together. That's significant.

Conclusion: The Reality vs. the Narrative

The standard narrative about US-China AI competition is incomplete. It's not wrong—competition is real and significant. But it leaves out a crucial part of the story: collaboration is also real and significant. These dynamics coexist.

WIRED's analysis of over 5,000 research papers from Neur IPS reveals the depth of this collaboration. Roughly 3 percent of papers involve authors from both US and Chinese institutions. That's hundreds of papers per year written by teams spanning the Pacific. It's models developed in one country being used by researchers in another. It's knowledge flowing in both directions. It's a research ecosystem that's genuinely global.

This collaboration isn't happening despite political tensions. It's happening in parallel with them. Researchers care about doing good science. They collaborate with whoever helps them do that. They publish in top venues regardless of where they're located. They build on each other's work. That's how science works.

For policymakers, the evidence suggests a need for nuance. Some restrictions might make sense for genuine security reasons. But broad restrictions on collaboration would be costly. They'd slow American innovation, reduce competitiveness of American institutions, and trigger retaliation. A better approach would distinguish between research collaboration (generally beneficial) and commercial technology transfer (appropriately more restricted).

For researchers, the message is that collaboration remains valuable and persistent. Build relationships with colleagues worldwide. Attend international conferences. Read work from other countries. Propose collaborations. The research community will support these efforts because they advance the field.

For institutions, the message is that talent and collaborative networks are competitive advantages. Invest in them. Protect them. Advocate for policies that preserve them. The institutions that maintain global networks will outcompete those that retreat to national silos.

Ultimately, this analysis reveals something optimistic beneath the headlines: despite all the rhetoric about competition and conflict, researchers on both sides of the Pacific are still working together. They're still sharing ideas. They're still advancing the field collectively. That's worth noticing. That's worth protecting. That's the reality beneath the narrative.

FAQ

What percentage of Neur IPS papers involve US-China collaboration?

Approximately 3 percent of papers presented at Neur IPS involve direct collaboration between authors from US and Chinese institutions. While this might sound small, it represents hundreds of papers per year at the premier AI research conference and indicates substantial ongoing cooperation between researchers across borders despite geopolitical tensions.

How do American and Chinese researchers actually collaborate?

Collaboration occurs through multiple channels including international conferences (like Neur IPS), journal publications, institutional partnerships between universities, open-source code sharing, and personal relationships built between researchers who studied or trained together. Many Chinese-born researchers work at American institutions while maintaining connections to colleagues in China, creating a natural bridge for collaboration.

Which AI models are most heavily shared between US and Chinese researchers?

Google's transformer architecture appears in 292 Neur IPS papers with Chinese authors, Meta's Llama family appears in 106 collaborative papers, and Alibaba's Qwen language model appears in 63 papers involving American researchers. This demonstrates bidirectional flow of innovations, with models developed in one country being actively used and improved by researchers in the other.

Would restricting US-China AI collaboration harm American research?

Yes, restrictions would likely harm American competitiveness. American universities rely on international talent and collaborative networks to maintain research quality. If American institutions lose access to Chinese talent and cannot collaborate with Chinese researchers, they would become less attractive to top global talent, potentially diminishing their position in the global research community and slowing innovation pace.

Is there a difference between research collaboration and commercial technology transfer?

Absolutely. Research collaboration involves sharing fundamental scientific knowledge, publishing papers, and working together on algorithms and frameworks. Commercial technology transfer involves sharing proprietary products, advanced chip designs, and business-critical technologies. Collaboration advances global science. Technology transfer involves protecting competitive commercial advantages. Smart policy would encourage the former while restricting the latter.

How has US-China AI collaboration changed over time?

Collaboration rates have remained remarkably stable, with about 3 percent of papers at Neur IPS involving both US and Chinese authors consistently across recent years. This stability suggests collaboration is deeply structural to how research works rather than being driven by temporary circumstances, indicating it would likely persist despite policy changes unless restrictions became extremely severe.

What role do international conferences play in enabling collaboration?

International conferences like Neur IPS serve as central meeting points where roughly 15,000 researchers from around the world gather, present work, and form new connections. These venues provide structured opportunities for researchers to discover shared interests, establish relationships, and launch collaborations. The global character of these conferences is essential to their prestige and their role in advancing the field.

Can collaboration continue if governments impose restrictions?

Yes, though at reduced levels. Researchers have strong incentives to collaborate and would find alternative methods if direct channels became restricted. They might use intermediaries, collaborate at international venues in third countries, or use online platforms. However, the collaboration would become less efficient, less visible, and likely less productive, representing a loss for global innovation without fully preventing cross-border work.

How does the talent flow between countries affect collaboration?

The movement of researchers between countries is crucial. Many researchers move from China to the US for graduate education, then either stay or return while maintaining professional relationships. These personal networks are the foundation of formal collaborations. Restricting talent flow would eventually break these networks as relationships fade, reducing future collaboration opportunities significantly.

Should policymakers be concerned about fundamental AI research collaboration?

Fundamental research collaboration is generally beneficial for innovation pace globally, including for American competitiveness. Concerns should focus on commercial technology transfer and sensitive dual-use research rather than basic science. Distinguishing between these categories in policy would be more effective than broad restrictions, preserving innovation benefits while addressing legitimate security interests.

Key Takeaways

- But here's what makes this significant: this rate has held steady

- They're mainstream participants in the cutting-edge research ecosystem

- Png)

*Estimated data shows that 20% of analyzed NeurIPS papers involved collaboration between US and Chinese institutions, highlighting significant international cooperation in AI research

- This foundational innovation—published in 2017 and now powering nearly every major AI system—appears in 292 Neur IPS papers with Chinese authors

- The innovation doesn't stop at the company that created it

Related Articles

- Gemini vs ChatGPT: Which AI Model Is Actually Better? [2025]

- Biotics AI Wins FDA Approval for AI-Powered Fetal Ultrasound Detection [2025]

- AI Bubble Myth: Understanding 3 Distinct Layers & Timelines

- 7 Biggest Tech Stories: Apple Loses to Google, Meta Abandons VR [2025]

- ChatGPT Ads Are Coming: Everything You Need to Know [2025]

- Grok's Unsafe Image Generation Problem Persists Despite Restrictions [2025]

![US and China AI Collaboration: Hidden Partnerships [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/us-and-china-ai-collaboration-hidden-partnerships-2025/image-1-1769024349133.jpg)