The United States Just Left the World Health Organization. Here's What That Actually Means.

On January 22, 2026, the United States officially withdrew from the World Health Organization after exactly one year of notice. But here's what most people don't understand: the US didn't quietly slip out the door. Instead, it slammed the door, broke the lock, and left behind a staggering financial mess.

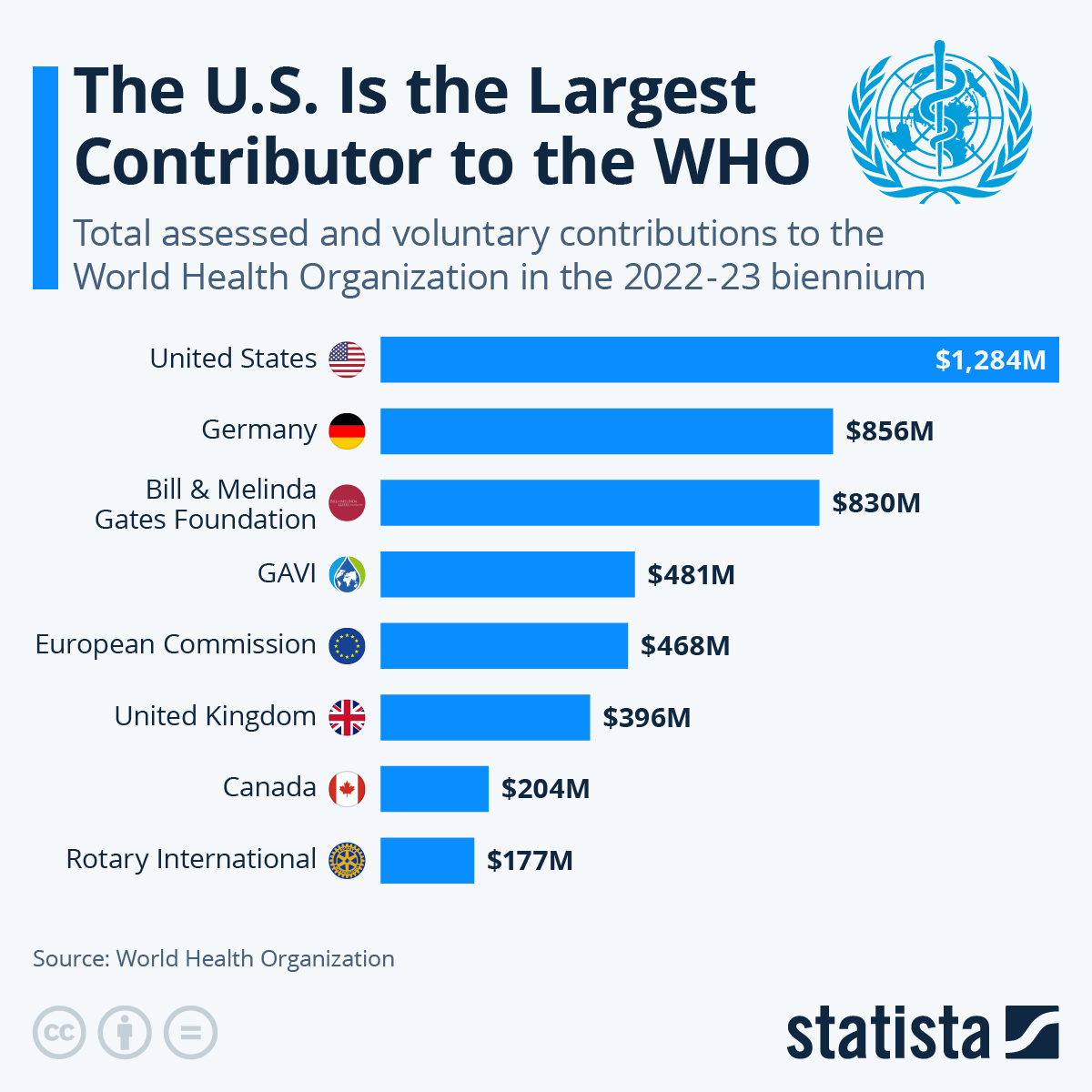

The numbers are genuinely staggering. The US owed the WHO

But this isn't just about unpaid bills. This withdrawal represents a fundamental shift in how the United States approaches global health governance. And the consequences will ripple far beyond Geneva headquarters. Disease surveillance systems will degrade. Outbreak response networks will fragment. Vaccine distribution channels will become less coordinated. The poorest countries in Africa and Southeast Asia—the places where the next pandemic will likely start—just lost their most important early warning system, according to Stat News.

Let's be clear about what just happened, why it happened, and what comes next.

The Timeline: How We Got Here

This didn't start last January. The groundwork for withdrawal was laid years ago.

In January 2020, during his first term, President Trump announced the US intention to withdraw from the WHO. His stated reasoning focused on the organization's response to COVID-19, which he believed was too lenient toward China. However, when the Biden administration took office on January 20, 2021, it immediately rescinded the withdrawal notice—literally on the first day in office, before the one-year notice period had even expired.

That bought the WHO a five-year reprieve. For that entire period, the US remained a member and continued funding the organization, though often at lower levels than before. The relationship was tense, but functional.

Then, on January 23, 2025, exactly one day after his second inauguration, Trump announced the withdrawal again. This time, he wasn't bluffing. The State Department issued formal notice of the US intention to exit, beginning a mandatory one-year notice period specified in a 1948 joint resolution of Congress.

But here's where it gets weird. While the formal one-year notice period is required by law, Trump administration officials immediately cut all practical ties with the WHO. They stopped attending meetings. They suspended funding. They treated the withdrawal as immediate, even though Congress required them to wait, as noted by Health Policy Watch.

For twelve months, the US remained technically a member while functionally absent.

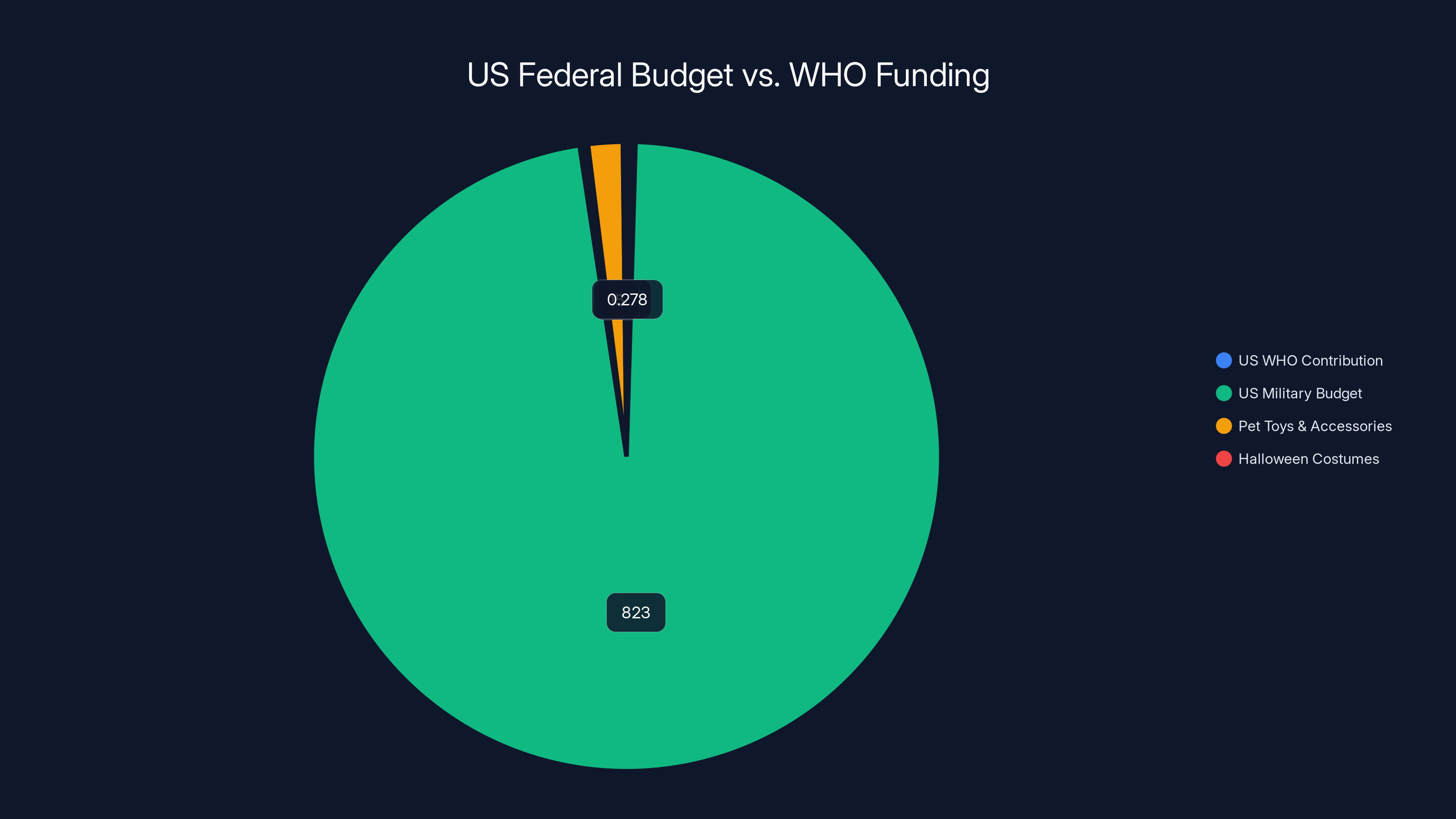

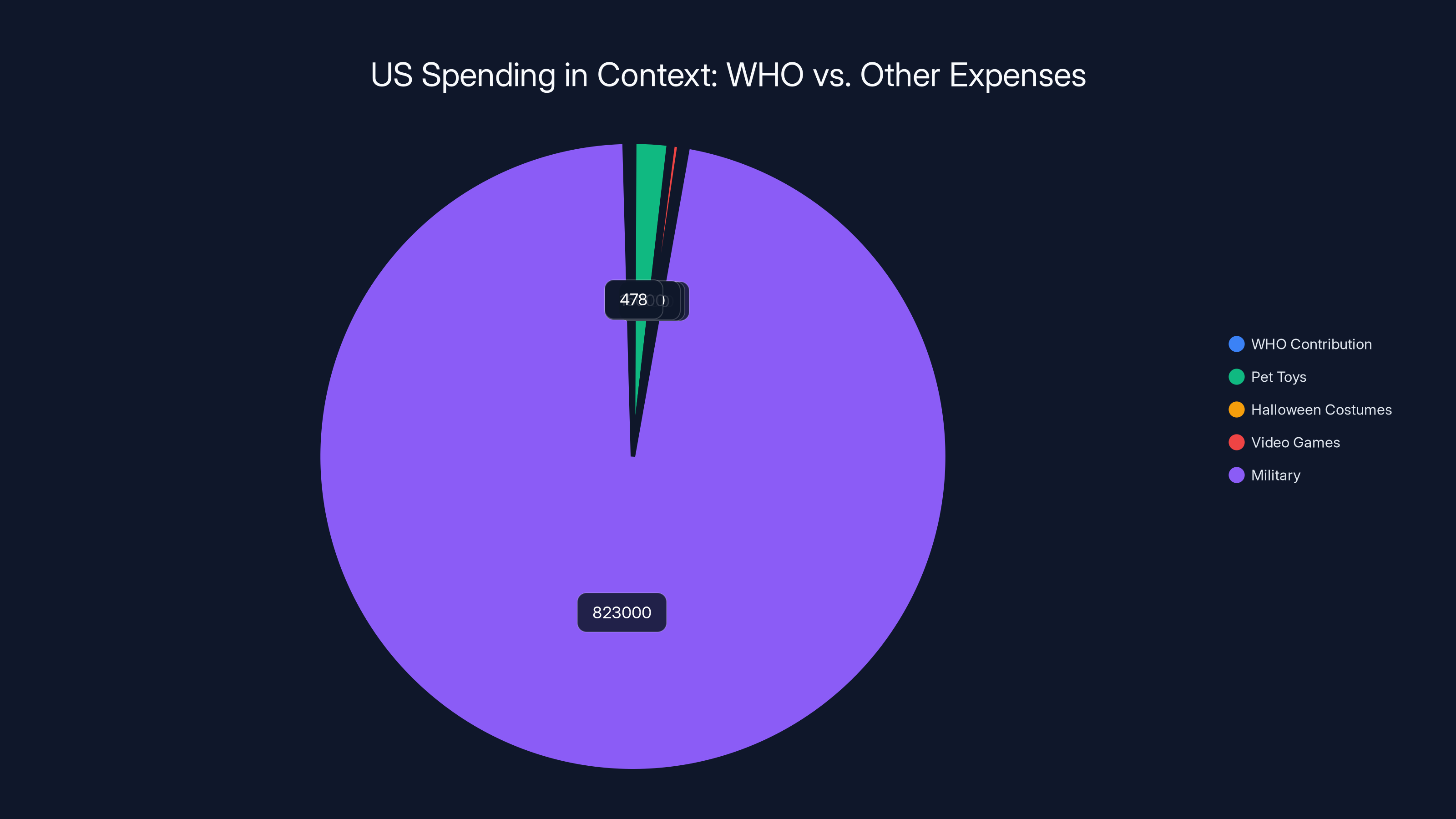

The US contribution to the WHO is a tiny fraction of its federal budget, dwarfed by military spending and even consumer expenditures like pet toys and Halloween costumes.

The Money: $768 Million Nobody's Getting

Now let's talk numbers, because they tell the real story.

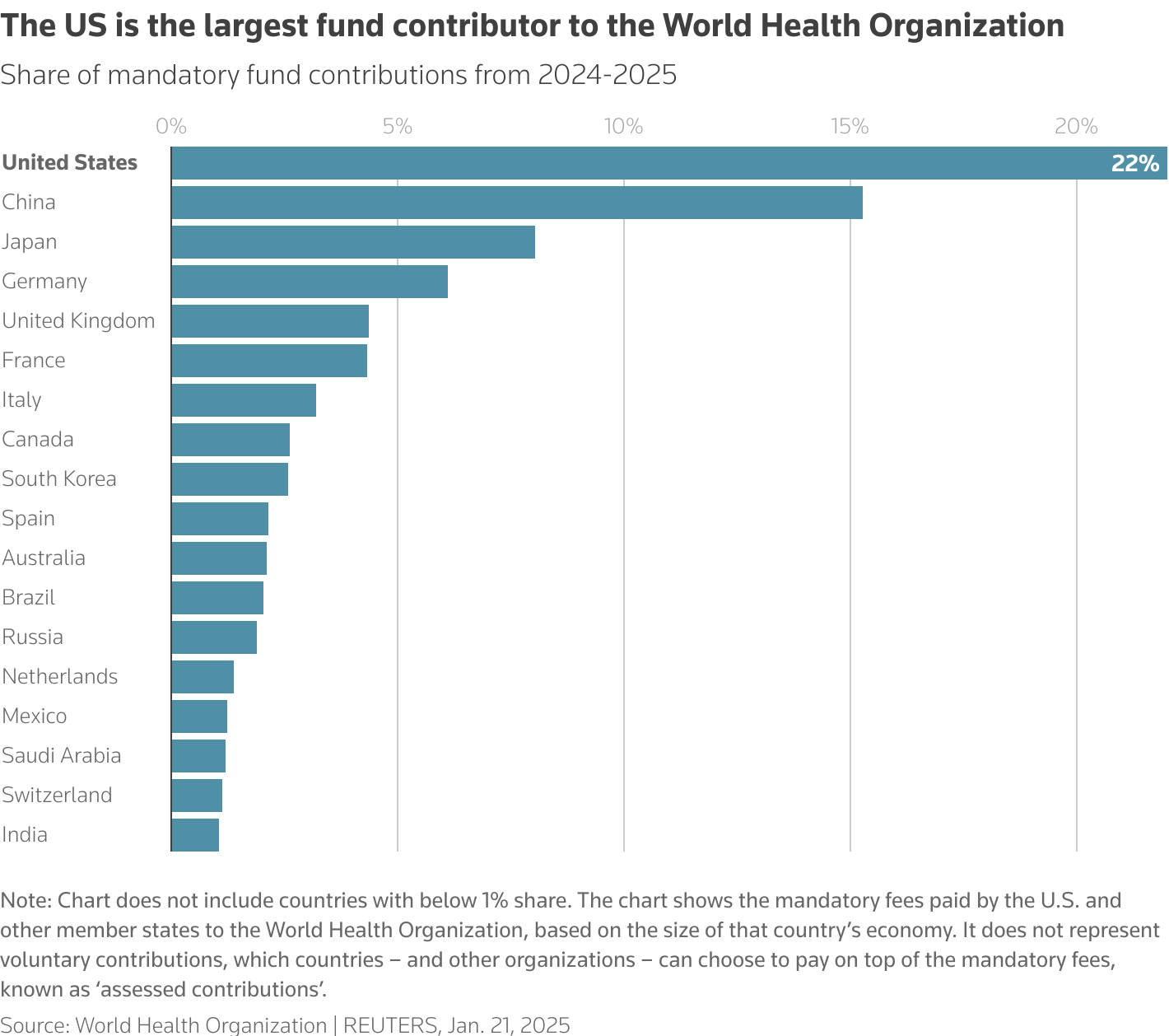

First, there's the $278 million in assessed dues. Here's how this works: the WHO operates on a two-year budget cycle. All member states contribute a percentage of their assessed dues based on a formula that factors in their gross domestic product and population. It's designed to be progressive—richer nations pay more.

The US, being the wealthiest nation in the world, pays a substantial share. For the 2024-2025 cycle, that came to $278 million. This isn't optional money. These are legal obligations under WHO membership. Congress knew about these obligations. They existed before the Trump administration took office. They were already spent.

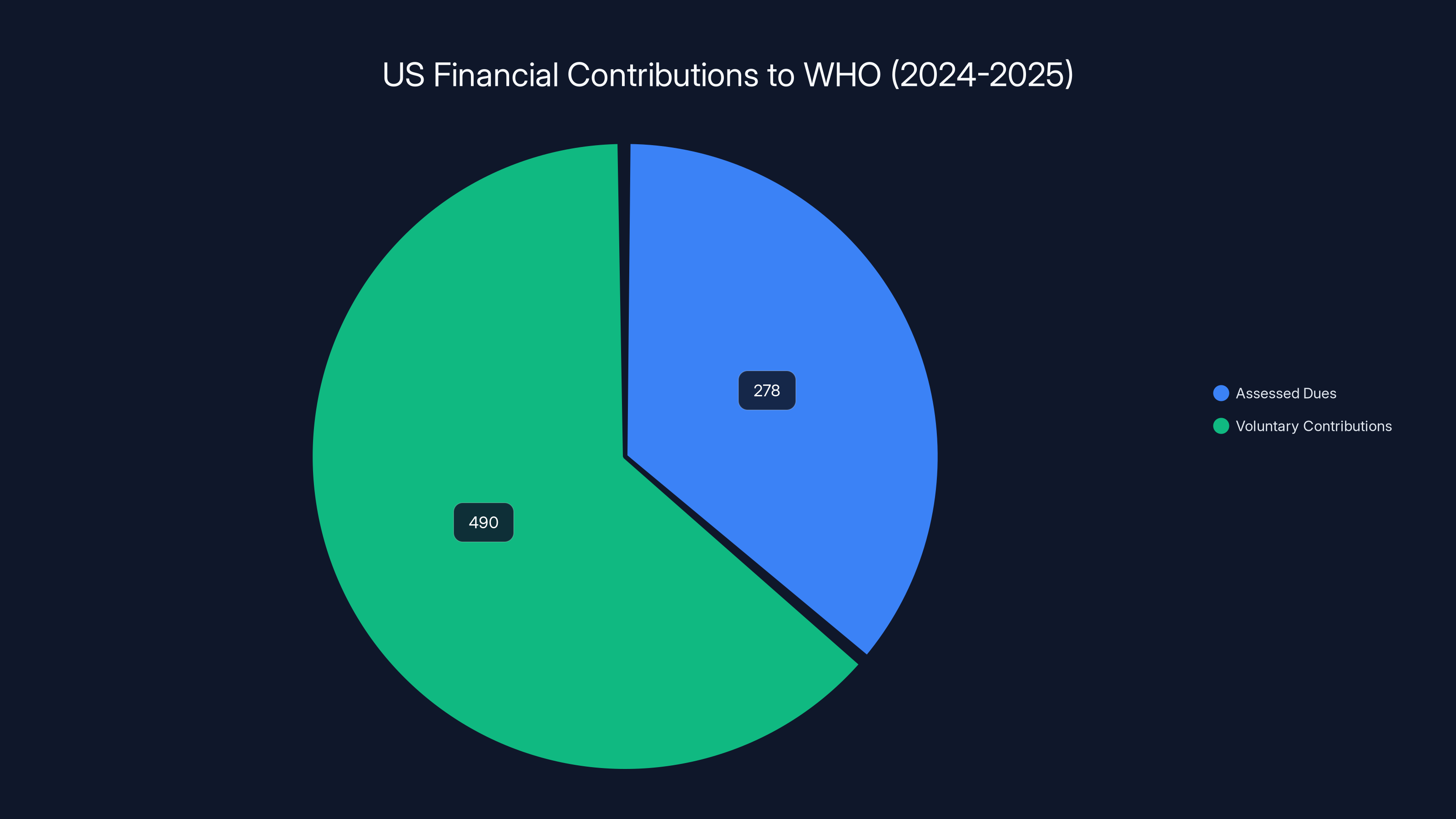

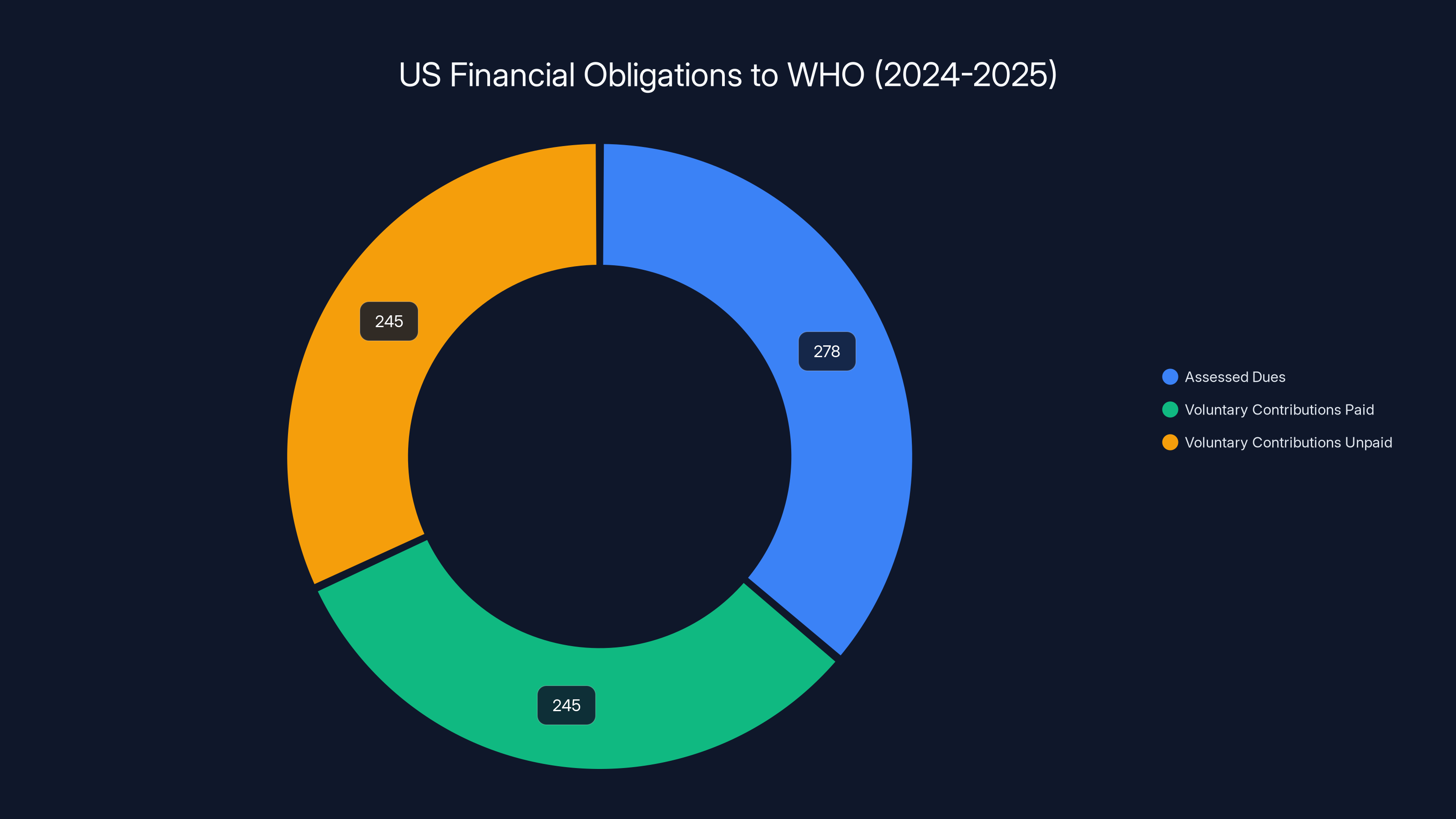

Then there are the voluntary contributions. Beyond assessed dues, member states can voluntarily pledge additional funding toward specific WHO programs. The US had pledged $490 million toward programs like the global health emergency program, tuberculosis control, and the polio eradication initiative.

According to reporting by health news outlets, some of this voluntary funding was actually paid out before the withdrawal, but the full amount was never transmitted. Anonymous sources suggested roughly half was paid, but nobody has exact numbers. The State Department spokesperson made clear that the Trump administration considers the debt unpayable, as highlighted by CGTN.

"The United States will not be making any payments to the WHO before our withdrawal on January 22, 2026," the State Department said in a statement to reporters. "The cost borne by the US taxpayer and US economy after the WHO's failure during the COVID pandemic—and since—has been too high as it is. We will ensure that no more US funds are routed to this organization."

Let that sink in. A federal law requiring payment of these obligations exists. The US committed to these funds. And the administration is openly saying it won't pay.

The Reasoning: COVID, China, and Credibility

Why? Trump has consistently blamed the WHO for mishandling the COVID-19 pandemic and for being insufficiently critical of China.

Here's the complexity: some of Trump's criticisms have merit. Early in the pandemic, the WHO did defer too much to Chinese authorities about the virus's origins and transmissibility. The organization was slower than it should have been to recommend travel restrictions. Some early guidance on masks was muddled.

But here's where context matters. The WHO operates by consensus among 194 member states. China is one of them. When the US is also a member, it has significant influence to counterbalance China's interests. By leaving the WHO, the US removed its own seat at the table. It can no longer vote on policies. It can no longer influence investigations. It can no longer direct funding toward priorities it cares about, as discussed in The Conversation.

In other words, by leaving the WHO to punish it for being influenced by China, the US essentially handed China even more relative influence over the organization.

The second component of the reasoning involves fiscal arguments. The Trump administration claims the US has already paid too much to the WHO and that continuing to fund it represents wasteful spending on an ineffective organization.

But here's the thing:

In other words, the US share of WHO funding is genuinely minuscule relative to total government spending. The decision to withdraw wasn't about fiscal efficiency. It was about ideology.

The US owed

The Immediate Impact: Hiring Freezes and Staff Cuts

The moment the WHO received the withdrawal notice on January 23, 2025, the organization began the brutal process of restructuring.

Without the US contribution, the WHO's budget for the 2024-2025 cycle was suddenly incomplete. They couldn't spend money they no longer had. The response was swift and severe.

Hiring and staffing immediately froze. No new positions could be filled. Vacant spots that had been posted weren't reopened. Retirement announcements meant positions just vanished.

Travel restrictions went into effect. Staff members could no longer attend conferences, visit field offices, or conduct in-person meetings. Everything moved to virtual formats.

Office operations were curtailed. Equipment purchases stopped. Office refurbishment projects were suspended. IT infrastructure updates were delayed. The organization basically went into survival mode.

Recruitment of new staff halted completely. This is particularly critical because disease surveillance and outbreak response require coordinated teams on the ground in vulnerable regions. Without new hiring, existing staff just gets older, more burned out, and more likely to leave.

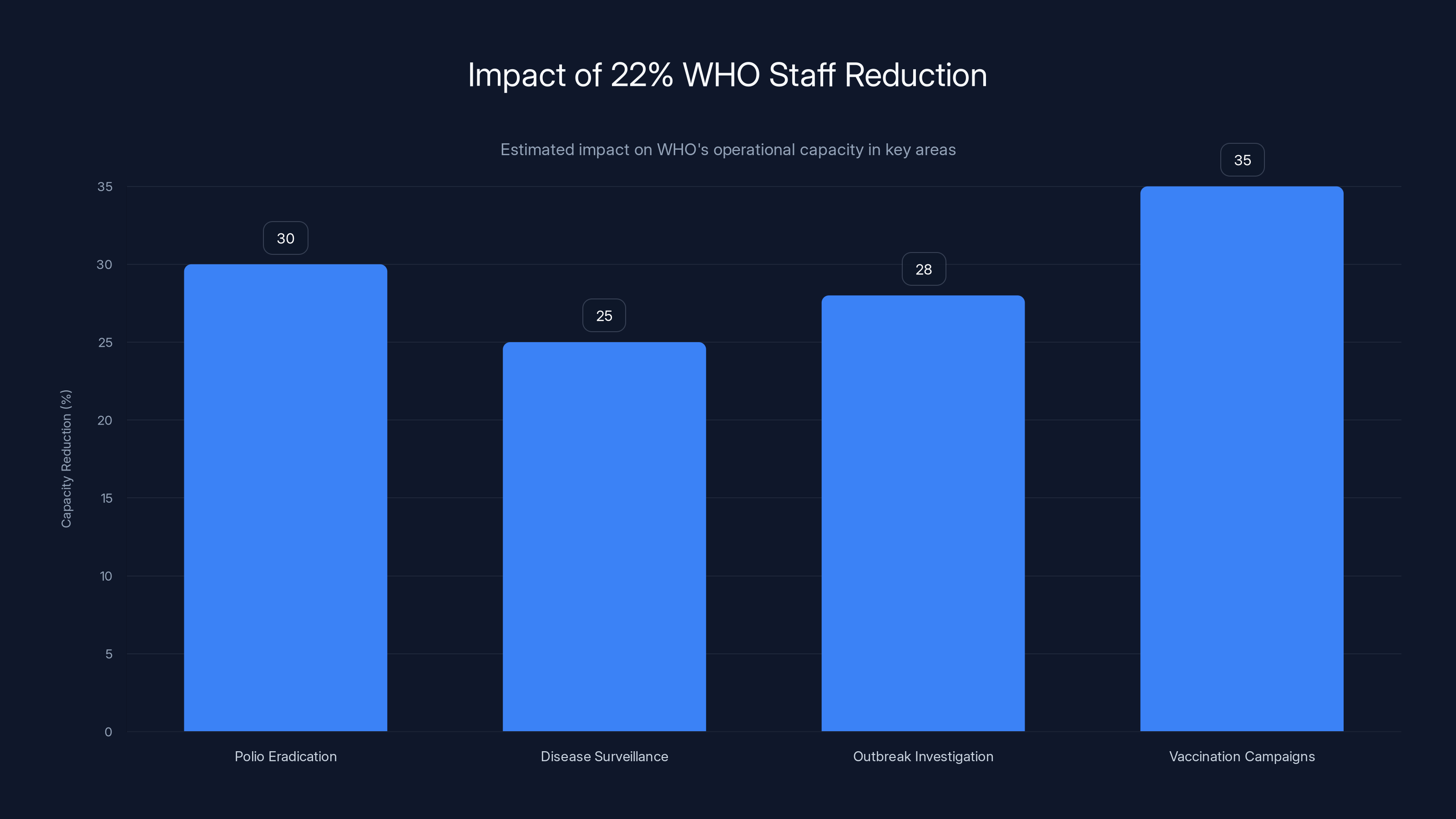

According to internal reporting, the WHO staff levels were projected to decline by 22% by mid-2026. Twenty-two percent. That's not a minor restructuring. That's dismantling institutional capacity, as noted by Health Policy Watch.

For a global health organization, staff are your surveillance network. Your epidemiologists. Your rapid response teams. Your field coordinators in fifty different countries. Cut them by 22%, and you don't just save money. You degrade your ability to detect, investigate, and respond to disease outbreaks in real time.

Disease Surveillance: The Hidden Crisis

Here's what nobody's really talking about, but what actually matters: the US withdrawal cripples global disease surveillance.

Let's think about how pandemic detection actually works in the modern world. It doesn't start with someone calling the UN. It starts with a doctor in a rural hospital noticing an unusual cluster of cases. Or a farmer noticing strange symptoms in livestock. Or a wastewater treatment plant detecting viral sequences in sewage.

These frontline observations flow up through national health systems to regional coordination centers. From there, they feed into the WHO's surveillance networks. The WHO maintains permanent staff in most countries specifically to receive and verify these reports in real time.

These aren't glamorous positions. They're not headlines. A WHO epidemiologist in rural Nigeria or Pakistan spends their day reviewing lab reports, checking rumors, verifying signals, and flagging suspicious patterns. Most of what they process is routine. But sometimes—maybe once every few years—they catch the signal that indicates the beginning of something catastrophic.

When the WHO loses 22% of its staff, many of those positions disappear. The coordination centers become understaffed. Response times slow. Some signals never get investigated at all.

Now, here's the irony: the US is still vulnerable to the diseases these surveillance systems detect. Maybe more vulnerable than before, because without the WHO as a central coordination hub, the US gets information later, from less reliable sources, often after other countries already know about the threat.

A novel respiratory virus in China? With strong WHO surveillance, the US gets comprehensive epidemiological data within hours of confirmation. Without it? The US relies on fragmented news reports, internet rumors, and informal channels. The lag time stretches from hours to days. In a pandemic, days matter.

The Polio Problem: A 30-Year Effort Collapsing

One specific example makes this concrete: polio eradication.

Polio is one of humanity's greatest public health achievements. In 1988, when the eradication campaign began, the virus was endemic in 125 countries and caused roughly 350,000 cases of paralysis annually. Today, it's endemic in only two countries and causes roughly 100-200 cases per year globally.

This happened because of sustained, coordinated effort by the WHO, national governments, NGOs, and countless healthcare workers. The US has been a major funder of this effort throughout. The money goes to vaccination campaigns, surveillance networks, and outbreak response teams in countries where polio still circulates.

Polio eradication is basically complete. We're in the final stretch. The finish line is visible. But it's not crossed yet. If the surveillance and vaccination infrastructure falls apart now, the virus rebounds, and we're back to the 1980s.

The $490 million in voluntary contributions that the US pledged included substantial funding for polio eradication. That money won't be paid. The vaccination campaigns will be reduced. The surveillance networks will be thinner. And there's a real risk that years of accumulated progress just evaporate, as reported by California Budget Center.

Similarly, the $490 million included funding for tuberculosis control, global vaccination programs, maternal health initiatives, and pandemic preparedness. All of it gets cut or severely reduced. All of it affects countries that can't absorb these funding gaps from domestic budgets.

The US has

Global Health Security: The Fragmentation Problem

The US withdrawal doesn't just reduce the WHO's funding. It fragments global health governance.

Before the withdrawal, countries could rely on the WHO as a neutral arbiter of health crises. When a disease outbreak occurred, the WHO convened experts, reviewed evidence, and made recommendations based on science rather than politics. Countries might disagree with specific recommendations, but they trusted the process.

With the US out of the WHO and potentially creating parallel health institutions, you now have competing centers of authority. The US might make different recommendations than the WHO. Other wealthy nations might split their allegiances. The global health system becomes balkanized.

This is particularly dangerous for low-income countries. They don't have the resources to maintain robust surveillance systems independently. They rely on the WHO's networks. When that network weakens because of funding cuts and staff reductions, disease detection degrades everywhere, but especially in the poorest regions.

And here's the kicker: those are the regions where zoonotic diseases jump from animals to humans most frequently. They're the regions where population density and poor sanitation create ideal conditions for virus transmission. They're the regions where the next pandemic will most likely originate.

So the US, by withdrawing from the WHO and cutting surveillance funding in poor countries, is essentially betting that the next pandemic won't start in those regions. That's not a safe bet. Every expert in infectious disease will tell you it is.

The Economic Argument That Doesn't Hold Up

Let's examine the administration's economic reasoning more carefully, because it reveals something interesting about how policy decisions get made.

The claim is that the US has "overpaid" to the WHO and that withdrawal saves taxpayer money. But here's what the numbers actually show.

In 2024, the US contributed roughly

In other words, the US contribution to the WHO was less than 0.015% of the federal budget. It was less than what Americans spend on pet supplies. For a nation with a $6.5 trillion economy, it's essentially negligible.

Now, let's think about the cost-benefit calculation. The US gets early warning of disease outbreaks. It gets a seat at the table for setting global health policy. It gets influence over how vaccines are distributed during pandemics. It gets data that informs domestic disease surveillance. It gets access to the WHO's research and technical expertise.

When you add up all that value, the real question is: how much is it worth to prevent a pandemic that costs the US economy $16 trillion (as COVID-19 did)? Or to get early warning of an outbreak that could kill millions of Americans?

The answer is obvious. The US would save money by paying 10 times what it currently pays to the WHO if it prevented even one pandemic as severe as COVID-19.

So the economic argument for withdrawal doesn't hold up to scrutiny. The US wasn't making a fiscally sound decision. It was making an ideological one dressed up in fiscal language.

The China Strategy: Misguided But Understandable

There's one element of the administration's reasoning that deserves more charitable consideration: concern about Chinese influence over the WHO.

China is an increasingly powerful voice in global health. It funds WHO projects. It sends researchers to collaboration efforts. It influences policies. And yes, the US has legitimate interests in limiting that influence.

But withdrawing from the WHO is arguably the worst possible strategy for limiting Chinese influence. Here's why.

When the US remains in the WHO, it has voting rights. It can propose investigations. It can direct funding toward priorities that counter Chinese interests. It can coordinate with other wealthy nations to form voting blocs. It can shape policy from inside the system.

When the US withdraws, it loses all of those tools. China remains a member with full voting rights. Other countries' influence relative to China actually increases because there's no US counterbalance.

If the goal was to reduce Chinese influence over the WHO, the strategic move would be to strengthen the US position within the organization, not to abandon it. Fund more research. Send more personnel. Lead more initiatives. Build stronger coalitions with like-minded nations.

Instead, the administration chose to withdraw, which hands the WHO to China and other nations that remain members. It's like abandoning a piece of strategic territory in a negotiation, then claiming you won.

The irony is thick. By withdrawing to punish the WHO for allegedly being too friendly to China, the US made the organization more friendly to China.

In 2024, US spending on the WHO was significantly lower than on pet toys, Halloween costumes, and video games, highlighting the relatively small financial commitment to global health compared to other expenditures.

Parallel Institutions: The Real Agenda

Here's what's actually interesting about the US withdrawal: it's not just about rejecting the WHO. It's about building alternative institutions.

In the months before the formal withdrawal, the Trump administration has floated the idea of creating a "US-led alliance" for global health. The specifics remain vague, but the general concept is clear: the US would create or coordinate a separate network of countries focused on health surveillance and pandemic preparedness outside the WHO structure.

This isn't inherently a bad idea. More institutions sometimes increase resilience and provide useful redundancy. But it also fragments global health governance at a critical moment.

When a novel virus appears in Southeast Asia, does the US alliance investigate it, or does the WHO, or do they work together with communication delays and duplicated effort? Who makes recommendations on travel restrictions? Who coordinates vaccine development and distribution? Who decides if something becomes a global health emergency?

If you have competing institutions with different memberships, different policies, and different priorities, you get slower response times and conflicting guidance. Exactly when you need rapid, unified action, you get bureaucratic confusion.

The US has the resources and expertise to create a capable alternative institution. But the world doesn't benefit from that alternative institution existing alone. The world benefits from coordination and unity, which the WHO, despite its flaws, provides.

What the WHO Says: More Than Just Disappointed

WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus initially characterized the US withdrawal as a "lose-lose situation."

That phrase is diplomatically careful understatement. Here's what it actually means.

The US loses access to the WHO's disease surveillance networks, epidemiological research, and rapid outbreak alerts. Without that information flow, the US becomes less prepared for emerging health threats. Future pandemics will hit the US without adequate warning.

The rest of the world loses the coordination and funding the US provides. The global health infrastructure degrades. Vaccination campaigns reduce. Surveillance networks thin. Pandemic preparedness suffers everywhere.

It's lose-lose because both sides are genuinely harmed. The US isn't just harming others. It's harming itself.

Tedros urged reconsideration, though he was careful to remain diplomatic. He knows the US government is watching. He knows further criticism could prompt additional funding cuts or even antagonize the administration into making things worse.

But behind the diplomatic language, the message is clear: this is a mistake.

The Precedent: What Other Countries Are Thinking

Here's what's less obvious but potentially more important: the US withdrawal sets a precedent.

If the US can simply refuse to pay its assessed dues and walk away from its obligations, what stops other countries from doing the same? What if China decides it doesn't like a WHO policy and announces withdrawal? What if Russia follows? What if India, Brazil, or Indonesia decide they're unhappy?

Once you've established that major powers can opt out of commitments whenever it's convenient, the entire system becomes less reliable. Countries become less willing to make financial commitments because they fear being stiffed. The organization's funding becomes less predictable. Long-term planning becomes impossible.

The US withdrawal is essentially a defection from the cooperative framework that keeps global health institutions functioning. Other countries are watching to see if there are consequences. And if there aren't meaningful consequences, other countries will start making similar calculations.

The 22% reduction in WHO staff is estimated to significantly impact operational capacities, with vaccination campaigns potentially seeing a 35% reduction in effectiveness. Estimated data.

Vaccine Distribution: The Next Crisis

One specific arena where the US withdrawal will cause immediate problems: vaccine distribution during the next major outbreak.

During COVID-19, the WHO coordinated the COVAX initiative, which distributed vaccines to low-income countries. It wasn't perfect—wealthy countries hoarded vaccines and high-income nations vaccinated their populations faster—but it provided a coordination mechanism and reduced some of the chaos.

Without the US as an active member, the next pandemic vaccine distribution will lack that coordination. Wealthy countries will again hoard. Poor countries will again struggle to access vaccines. The global death toll will be higher than it needed to be.

The irony, again, is that vaccine distribution matters to the US. During COVID-19, variants emerged in poorly vaccinated populations globally and then spread back to the US. If the US had prioritized global vaccine equity, it would have reduced its own infection rates.

By withdrawing and reducing funding for global vaccination infrastructure, the US is increasing the probability of a future variant emerging abroad and then spreading back home.

The Staffing Crisis: Real-World Consequences

The projected 22% reduction in WHO staff isn't an abstract number. It has real-world consequences.

Take the WHO's polio eradication program. It has staff in every country with endemic transmission. These aren't high-level administrators. These are epidemiologists, logistics coordinators, and vaccination campaign managers working in the field in difficult conditions.

Each of those positions represents a specific capacity. When you eliminate a position, you don't just eliminate an employee. You eliminate surveillance coverage for a geographic region. You reduce vaccination campaign capacity. You slow outbreak investigation and response.

And the people in these positions often aren't easily replaced. They have years of experience working in specific regions, relationships with local health authorities, and institutional knowledge. When they leave, their expertise walks out the door.

Similarly, in the WHO's disease surveillance division, the 22% staff cut means fewer epidemiologists monitoring disease patterns globally. Fewer people reviewing lab reports. Fewer experts available for outbreak investigations.

When a novel influenza variant emerges in China, someone at the WHO needs to investigate it. That person needs to contact local health authorities. Review sequence data. Assess transmission patterns. Provide analysis to member states. With 22% fewer staff, that investigation takes longer. The analysis is less thorough. The early warning is delayed.

Tuberculosis and Other Overlooked Threats

The US funding cuts will also degrade the WHO's work on diseases that don't make headlines but kill far more people than COVID-19.

Tuberculosis still kills roughly 1.3 million people globally every year. It's the leading cause of death from a single infectious agent. The WHO coordinates TB surveillance, drug-resistance monitoring, and treatment initiatives globally.

The US cut $490 million in proposed voluntary contributions, and a substantial portion was designated for TB control. That funding will evaporate or be severely reduced. TB surveillance networks will thin. Drug-resistance monitoring will degrade. Treatment program expansions will be delayed.

The result? TB continues to spread and evolve resistance to existing drugs. Drug-resistant strains become more prevalent. And because TB travels with global mobility, resistant strains eventually reach the US, where they're harder to treat.

Again, the US withdrawal is self-defeating. By cutting global TB funding, the US is increasing the risk of drug-resistant TB eventually reaching its own borders.

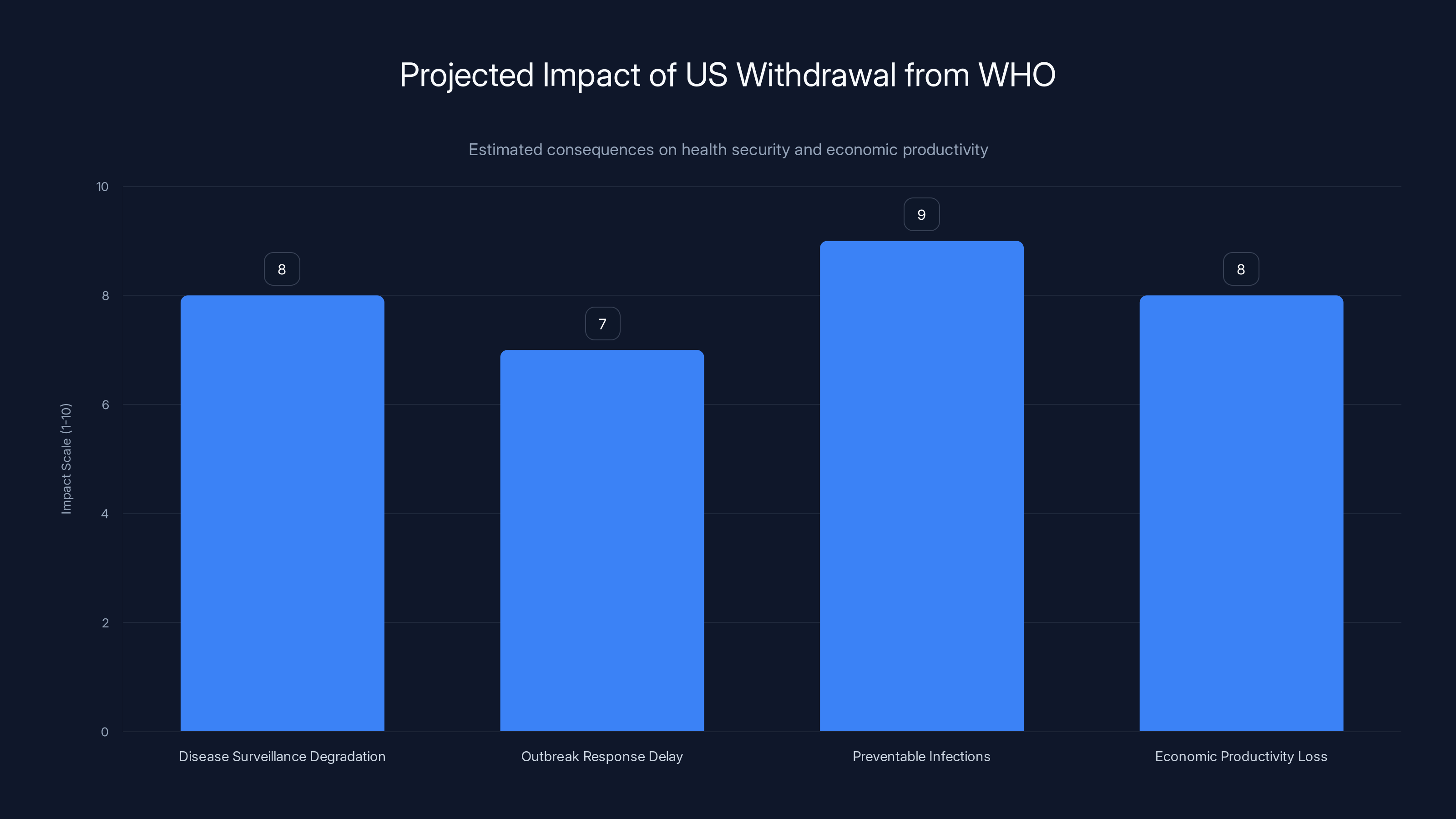

Estimated data suggests significant impacts on health security and economic productivity due to the US withdrawal from WHO, with high scores in disease surveillance degradation and preventable infections.

Pandemic Preparedness: The Infrastructure We're Losing

The WHO maintains global surveillance infrastructure specifically designed to detect novel pathogens. This includes:

Viral genome sequencing networks that monitor for mutations in circulating viruses, identifying when a virus gains transmissibility or evades immunity.

Wastewater surveillance systems that detect viral presence in sewage before symptomatic infections peak, providing early warning of community spread.

Laboratory networks that can identify unusual pathogens and characterize them quickly.

Epidemiological investigation teams that deploy to outbreak sites, investigate transmission chains, and provide real-time data to global partners.

Data integration platforms that consolidate information from hundreds of sources globally and identify patterns that might indicate emerging threats.

All of this infrastructure is maintained with WHO funding and coordination. With the US out and funding cut, these systems degrade. Genome sequencing becomes less comprehensive. Wastewater surveillance stops in some regions. Investigation teams have fewer resources. Data integration slows.

The result is slower detection of the next novel pathogen. By the time the world recognizes it as a pandemic threat, the virus has already spread more widely. The pandemic response starts later and from a worse baseline.

The Cost to Americans: Not Just Abstract

Let's bring this back to actual impact on Americans.

The next novel influenza virus emerges in a poultry farm in Southeast Asia. Instead of the WHO's regional surveillance network detecting it within weeks, it takes months because staffing is reduced. By the time the US realizes there's a new threat, the virus has spread across multiple countries.

A novel respiratory virus circulates in Peru. The WHO's investigation team can't deploy immediately because they've had staff cuts. The investigation takes longer. Mutation patterns aren't characterized quickly. The US pharmaceutical industry is slower to start vaccine development because they lack crucial epidemiological data.

A drug-resistant tuberculosis strain emerges in South Africa. The WHO's TB surveillance network is degraded. The emergence isn't documented as thoroughly. The strain spreads across Africa. By the time it reaches the US, it's entrenched in multiple countries, making eradication much harder.

These aren't hypothetical scenarios. This is how pandemics actually begin. They start with surveillance failures that delay recognition. They accelerate through gaps in global coordination. They reach wealthy countries because of degraded early warning systems in poor regions.

The US withdrawal from the WHO increases the probability of all these scenarios occurring. And when they do, Americans pay the cost in infections, deaths, economic disruption, and healthcare costs.

It's not a theoretical argument. It's a straightforward assessment of epidemiology and outbreak dynamics.

The Geopolitical Realignment: Who Fills the Gap?

Here's another consequence nobody's really discussing: what happens when the US steps back?

Other powers move forward. China is already positioning itself as a global health leader. It's investing in health research initiatives in Africa. It's proposing alternative frameworks for pandemic governance. It's building relationships with countries through health diplomacy.

With the US withdrawn from the WHO, China's relative influence grows. India and Brazil, as rising powers, gain more voice in global health discussions. The traditional Western dominance of international health governance diminishes.

Now, international health governance probably shouldn't be dominated by the US or any single country. But the shift toward a multipolar system happens faster when the US voluntarily removes itself from the table.

The result is a less predictable, less coordinated, less effective global health system. Everyone loses, including the US.

Looking Forward: What Comes Next

The US withdrawal is now final. January 22, 2026, has passed. The withdrawal is complete and irreversible for at least one year (the administration would have to give new notice to rejoin).

What's likely to happen over the next 12-24 months?

First, the WHO will continue restructuring around the new financial reality. Staff reductions will continue. Some programs will be curtailed. Operations will become leaner and less capable.

Second, other countries will likely increase their contributions to compensate. Japan, Germany, and other wealthy nations have indicated willingness to increase funding. But they can't fully replace $278 million in assessed dues. Some programs will have less funding than before.

Third, the Trump administration will likely try to establish parallel health institutions. The specific form remains unclear, but expect announcements about US-led health coalitions, bilateral health agreements, and alternative coordination mechanisms.

Fourth, the next novel pathogen will likely emerge. When it does, the global response will be slower and less coordinated than it should be. The US will still be vulnerable to that threat despite withdrawing from the WHO. The decision to withdraw won't provide extra protection. It will provide less.

Fifth, other countries will watch to see if there are consequences for violating commitments to international institutions. If there aren't meaningful consequences, expect more countries to start questioning their WHO participation.

Alternative Models: What Would Have Been Better

If the Trump administration was genuinely concerned about WHO effectiveness or Chinese influence or fiscal efficiency, there were better approaches.

Reforming from within. The US could have proposed specific reforms to WHO governance, decision-making, or operations. It could have lobbied for policy changes. It could have worked with other member states to form voting blocs. Many countries are also frustrated with aspects of WHO performance. A coalition of reformers could have pushed significant changes.

Conditional funding. The US could have made its contributions conditional on specific performance metrics or policy changes. "We'll fund polio eradication fully if the WHO implements these surveillance reforms." That creates leverage without abandoning the institution.

Increased engagement. The US could have increased its engagement with the WHO, not decreased it. Send more personnel. Propose more initiatives. Lead more research collaborations. Strengthen the US position from inside the organization.

Parallel institutions plus membership. The US could have created a "US-led health alliance" while remaining a WHO member. This provides redundancy and alternatives without fragmenting global health governance.

Instead, the Trump administration chose complete withdrawal. It's the most adversarial option, the most likely to be counterproductive, and the one that maximizes disruption to the global health system.

The Long-Term Implications: Setting a Precedent

Perhaps the most concerning element of the US withdrawal is the precedent it sets.

International institutions work because countries believe commitment is valuable and that defection carries costs. When a major power like the US simply walks away from commitments, it undermines confidence in the entire system.

If the US can refuse to pay assessed dues and withdraw from agreements, why should other countries make credible commitments to international institutions? Why fund the UN? Why participate in trade agreements? Why maintain alliances?

The US withdrawal from the WHO is part of a broader pattern of declining commitment to multilateral institutions. This has real consequences for global stability, health security, economic coordination, and conflict prevention.

The next pandemic won't know that the US withdrew from the WHO. The virus won't care about ideological disputes or fiscal arguments. It will spread globally, and the world will be less prepared because coordination was degraded.

And Americans will get infected, hospitalized, and die because their country withdrew from the institution designed to prevent exactly this scenario.

It's not a failure of the WHO's design. It's a failure of US strategy.

Conclusion: The Real Cost of Withdrawal

The US withdrawal from the WHO is now complete. The money won't be paid. The staffing will be cut. The surveillance will degrade. The programs will be curtailed.

The stated reasoning—that the WHO failed during COVID-19 and the US can't afford to fund an ineffective organization—has some surface appeal. But the logic doesn't survive scrutiny. The US paid a tiny fraction of its budget to the WHO. The organization's early warning systems are valuable. The coordination function is essential. The exit strategy is counterproductive.

What the US actually did was weaken its own health security in pursuit of an ideological point. It's like a homeowner cutting down the lightning rod because they're angry about a previous lightning strike. The rod didn't cause the strike. Removing it just increases the risk of the next one.

The consequences won't be immediately obvious. The next few years might feel normal. Disease surveillance will degrade gradually. Outbreak response will be slower but still functional. The degradation will be measured in months of delayed detection, thousands of preventable infections, and billions in lost economic productivity when the next major outbreak occurs.

By then, the decision will be irreversible. The US will have been out of the WHO for years. Re-entering would require new Congressional action and would signal a reversal of stated policy.

So the US will likely stay out, even as the consequences become undeniable. And the next pandemic will be worse because of that choice. More people will get infected. More will die. The economic cost will be higher. And the US, having withdrawn from the institution designed to prevent exactly this scenario, will struggle to coordinate an effective response.

That's the real cost of withdrawal. Not

It's a self-inflicted wound. And it's going to hurt.

FAQ

What exactly is the World Health Organization and what does it do?

The WHO is a specialized agency of the United Nations that coordinates global health efforts among 194 member states. It runs disease surveillance networks that detect outbreaks early, provides technical expertise for epidemic response, coordinates vaccine distribution during health emergencies, sets international health standards and regulations, funds health research and programs in low-income countries, and maintains rapid response teams that deploy to outbreak sites. Essentially, it's the global coordination mechanism for responding to infectious diseases and health emergencies. Without it, each country responds independently, which creates inefficiencies, duplicated effort, and slower overall response times.

Why did the Trump administration withdraw from the WHO?

The Trump administration cited three main reasons: first, they claimed the WHO mishandled the COVID-19 pandemic and was too lenient on China regarding the virus's origins; second, they argued the US was overpaying relative to benefits received; and third, they believed the organization was ineffective and that US taxpayers shouldn't fund it. However, the fiscal argument is weaker than it initially appears—the US contribution was less than 0.015% of the federal budget, roughly equivalent to what Americans spend on pet toys. The strategic argument is also questionable because withdrawing gives China more relative influence in the organization rather than less.

How much money did the US owe and what happens to it?

The US owed

What does a 22% reduction in WHO staff actually mean for disease surveillance?

It means the organization loses roughly one-fifth of its personnel globally, including epidemiologists, outbreak investigators, surveillance coordinators, and program managers. These aren't administrative positions. They're the people who review disease patterns, investigate outbreaks, verify alerts from member states, coordinate responses, and maintain field presence in vulnerable regions. With 22% fewer staff, outbreak investigation takes longer, some signals get missed entirely, and early warning is delayed. That delay directly translates to more transmission before the world recognizes a new pathogen as a pandemic threat.

How does US withdrawal affect vaccine distribution during future pandemics?

During COVID-19, the WHO coordinated COVAX, which provided vaccine distribution mechanisms for low-income countries. Without US participation and with reduced WHO funding, the next pandemic vaccine distribution will lack that coordination. Wealthy countries will hoard vaccines again, poor countries will struggle to access them, and variants will emerge in poorly vaccinated populations abroad before spreading back to the US. This is self-defeating because US vaccine distribution during future pandemics depends on global vaccine equity reducing mutation rates and transmission globally.

Could the US create its own health surveillance system instead of relying on the WHO?

Theoretically yes, but practically, it would be slower, less comprehensive, and more expensive. The WHO's strength is that it operates in 194 countries simultaneously with established relationships with health authorities, existing infrastructure, and coordinated protocols. The US could create a parallel system, but it would take years to build, would cost more than WHO membership, and would lack the global reach and credibility that multilateral institutions provide. During that build-out period, global surveillance degrades, which increases pandemic risk for everyone including the US.

What countries are most affected by the US withdrawal and why?

Low-income countries in Africa, South Asia, and Southeast Asia are most affected because they depend on WHO funding for disease surveillance, vaccination programs, and outbreak response. These are also the regions where novel pathogens originate most frequently due to factors like population density, animal-human contact, and limited healthcare infrastructure. When surveillance degrades in these regions, the world gets later warning of emerging threats. Middle-income countries can partially compensate with domestic funding, but truly low-income countries cannot absorb the funding loss without external support.

Could other countries increase their funding to compensate for the US withdrawal?

Partially. Japan, Germany, the UK, and some other wealthy nations have indicated willingness to increase contributions. However, no other single country can replace

Is the US still vulnerable to diseases even after withdrawing from the WHO?

Absolutely yes. In fact, the US is arguably more vulnerable now. By withdrawing, the US loses direct access to WHO disease surveillance data. It gets outbreak alerts later, from less reliable sources, and often after multiple countries already know about the threat. During a rapidly spreading pandemic, these delays matter enormously. Slower detection means slower vaccine development, slower public health response, slower border controls. The US withdrawal reduces global pandemic preparedness, which directly increases pandemic risk for the US population.

What happens if another country decides to withdraw from the WHO following the US precedent?

If major powers start withdrawing from the WHO, the organization becomes even less effective and less coordinated. If China withdraws, the organization loses input from the world's second-largest economy. If Russia or India withdraws, you lose surveillance coverage in critical regions. The entire system depends on major powers remaining members and participating in coordination. Once you establish that powerful countries can opt out whenever it's convenient, the system's effectiveness degrades rapidly. This is why the US withdrawal is concerning not just for immediate health consequences, but for the precedent it sets for other international institutions.

The Path Forward: What You Should Know

The US withdrawal from the WHO is now final. The short-term consequences will be organizational restructuring at the WHO, reduced funding for global health programs, and degraded disease surveillance capacity. The medium-term consequences will be slower outbreak detection and response during the next health emergency.

The long-term consequences depend on whether other countries increase their contributions enough to maintain basic functions, whether the US eventually creates effective parallel institutions that fill the coordination gap, and whether the next pandemic emerges soon enough that its consequences demonstrate the withdrawal's strategic error.

What's clear now: the US made a choice that increased global health risk. That choice will have consequences. When they arrive, they'll be measured in preventable deaths and billions in economic costs.

And by then, it will be too late to undo the decision. The institutional damage will be done. The staff will have moved on. The capability will have degraded.

The calculation was simple: $768 million in money plus ideological satisfaction about punishing the WHO versus increased pandemic risk for Americans and global health vulnerability. The administration chose the former. History will likely judge it harshly.

Key Takeaways

- US withdrawal leaves WHO with $768 million in unpaid obligations while the organization faces 22% staff reductions

- Global disease surveillance networks will degrade significantly, delaying detection of novel pathogens that could become pandemic threats

- The fiscal argument for withdrawal is weak—US contribution was 0.015% of federal budget, less than pet toy spending

- By withdrawing, the US actually hands increased relative influence to China rather than reducing it, contrary to stated strategic goals

- The withdrawal sets dangerous precedent: if major powers can abandon multilateral commitments, entire international institutions become unstable

![US Exit From WHO: $768 Million Gap & Global Health Crisis [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/us-exit-from-who-768-million-gap-global-health-crisis-2025/image-1-1769125048639.jpg)