Warner Bros. Netflix Merger vs Paramount Deal: Everything You Need to Know

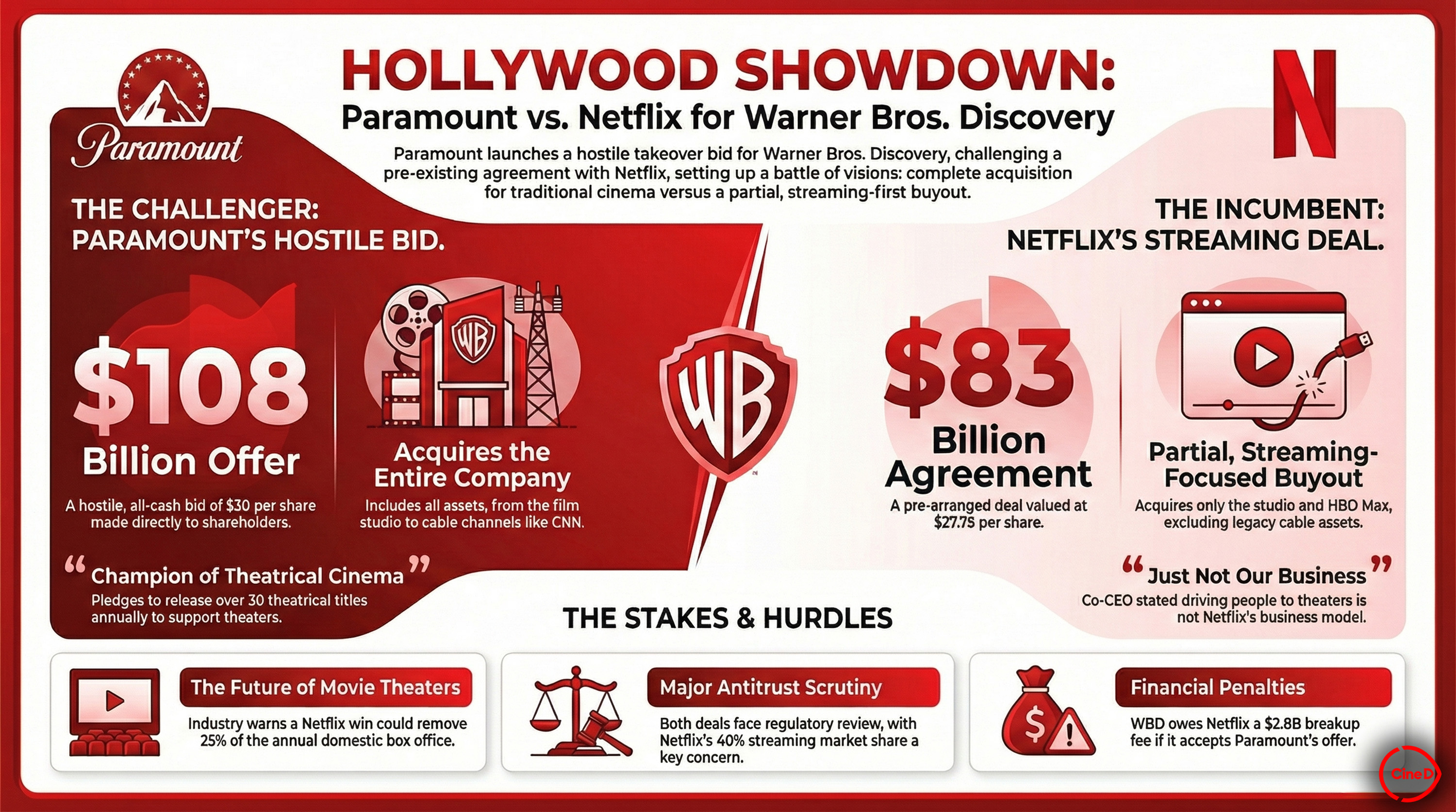

The entertainment industry just entered one of the most consequential dealmaking moments in streaming history. In February 2026, Warner Bros. Discovery faced a choice that could reshape how millions of people watch television, movies, and everything in between. Netflix offered $72 billion to acquire the company's streaming and studio divisions. Paramount countered with its own hostile bid. The board gave Paramount exactly one week to make its best offer. Seven days to potentially rewrite the entire streaming landscape.

This isn't just another corporate merger. The decision will affect what shows get made, how much you'll pay for subscriptions, which streaming service survives, and whether the consolidation trend in entertainment continues unchecked. The stakes are genuinely that high.

Here's what makes this situation so fascinating: Warner Bros. is simultaneously recommending the Netflix deal to shareholders while leaving the door open for Paramount. It's corporate poker played at the highest level, with billions of dollars and the future of entertainment hanging in the balance. The company scheduled a March 20 shareholder vote for the Netflix merger, but that date could change if Paramount comes back with something compelling.

What we're witnessing is the collision of two fundamentally different strategies. Netflix wants to buy the best streaming content and studio assets without taking on Warner Bros.' struggling linear TV business. Paramount wants the entire company, thinking that integration creates unstoppable value. One approach is surgical and focused. The other is audacious and risky.

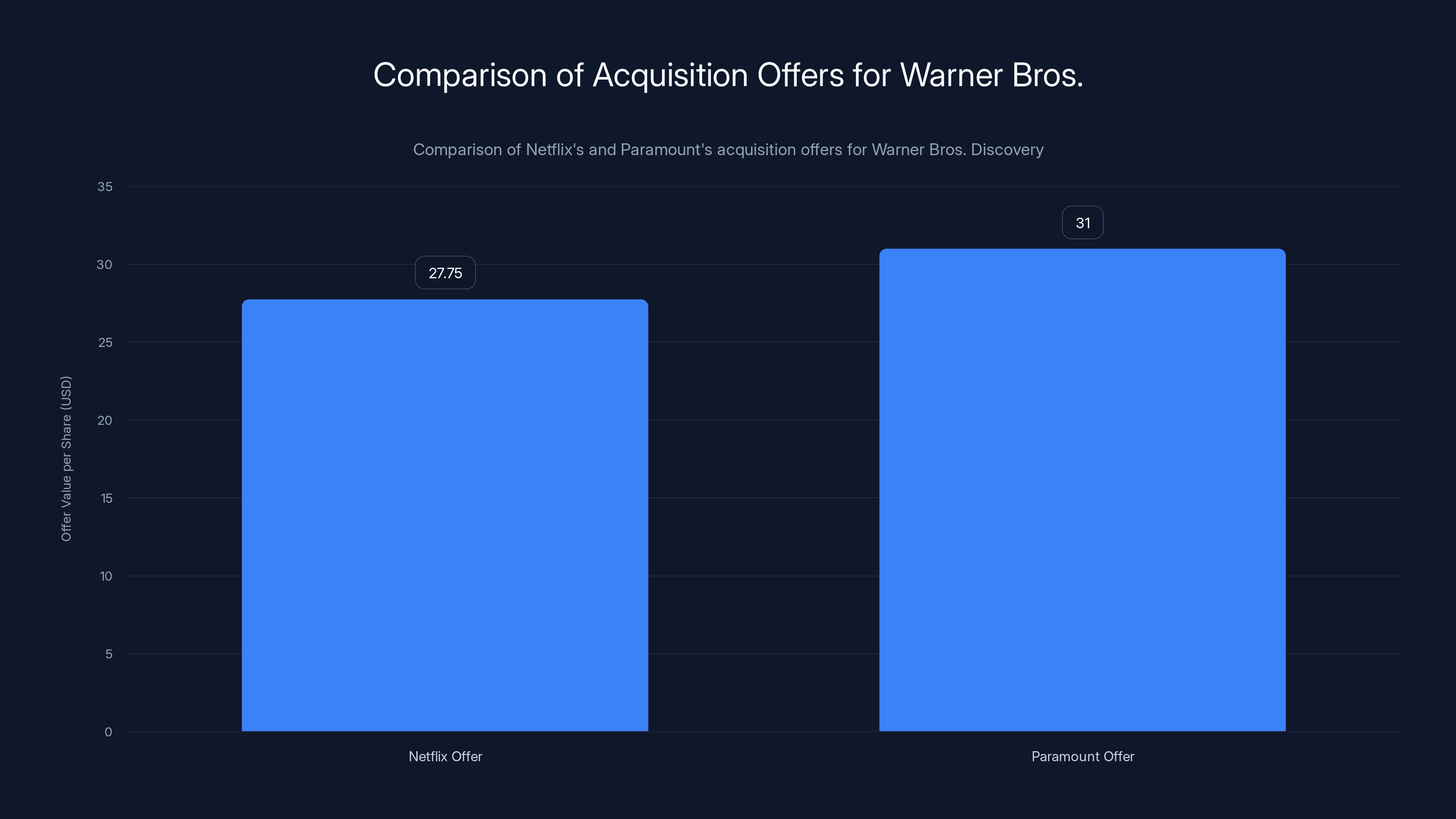

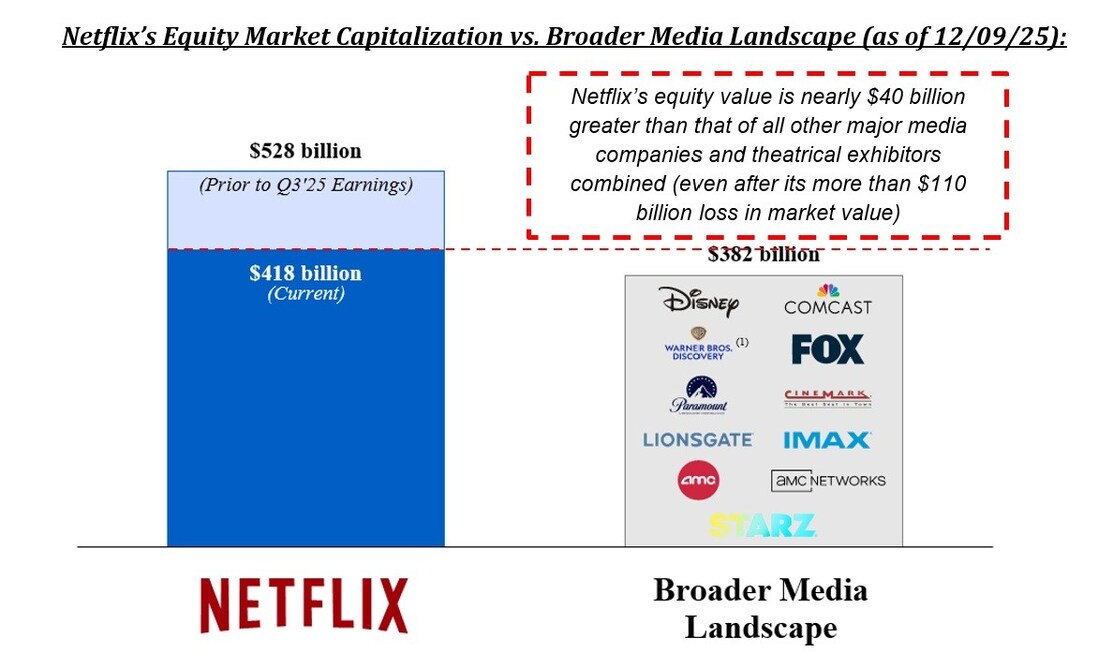

The financial gap between these offers is enormous, which is why understanding the details matters. Netflix is paying

There's also the question of what happens to Discovery, the cable TV business. Under Netflix's plan, Discovery gets spun off into a separate company. Under Paramount's plan, it stays integrated. That's not just a corporate structure question. It determines whether an entire division survives as an independent entity or gets absorbed into a larger media conglomerate.

For anyone who cares about entertainment, technology, media consolidation, or just wants to understand why their favorite streaming service might change, this merger saga is essential context. Let's break down every angle of this deal.

TL; DR

- Netflix's offer: 27.75 per share in all cash, with Discovery spinning off separately

- Paramount's counterbid: $31 per share for the entire Warner Bros. Discovery company, requiring significant debt financing and less certain legal terms

- The deadline: Paramount has one week (through February 23, 2026) to make its best and final offer, with Netflix retaining the right to match any deal

- What's at stake: The consolidation of major entertainment assets, the future of competing streaming services, and which model wins in the streaming wars

- The key difference: Netflix is proven, well-capitalized, and taking a surgical approach. Paramount is betting that buying everything creates more value through integration

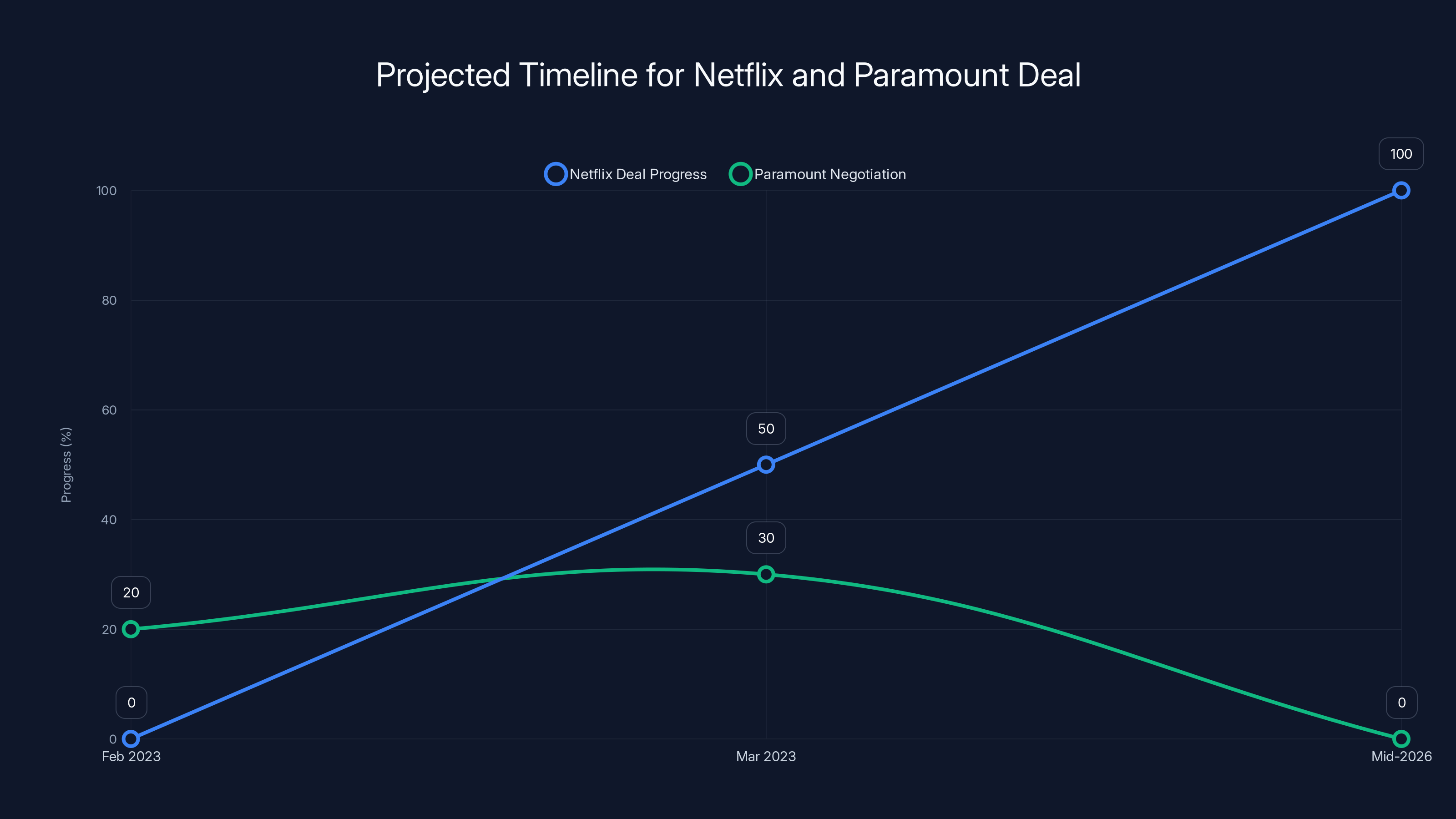

The projected timeline suggests Netflix's deal progresses steadily, with a likely closure by mid-2026, while Paramount's bid diminishes over time. Estimated data based on strategic analysis.

The Netflix Deal: $72 Billion for Streaming Assets

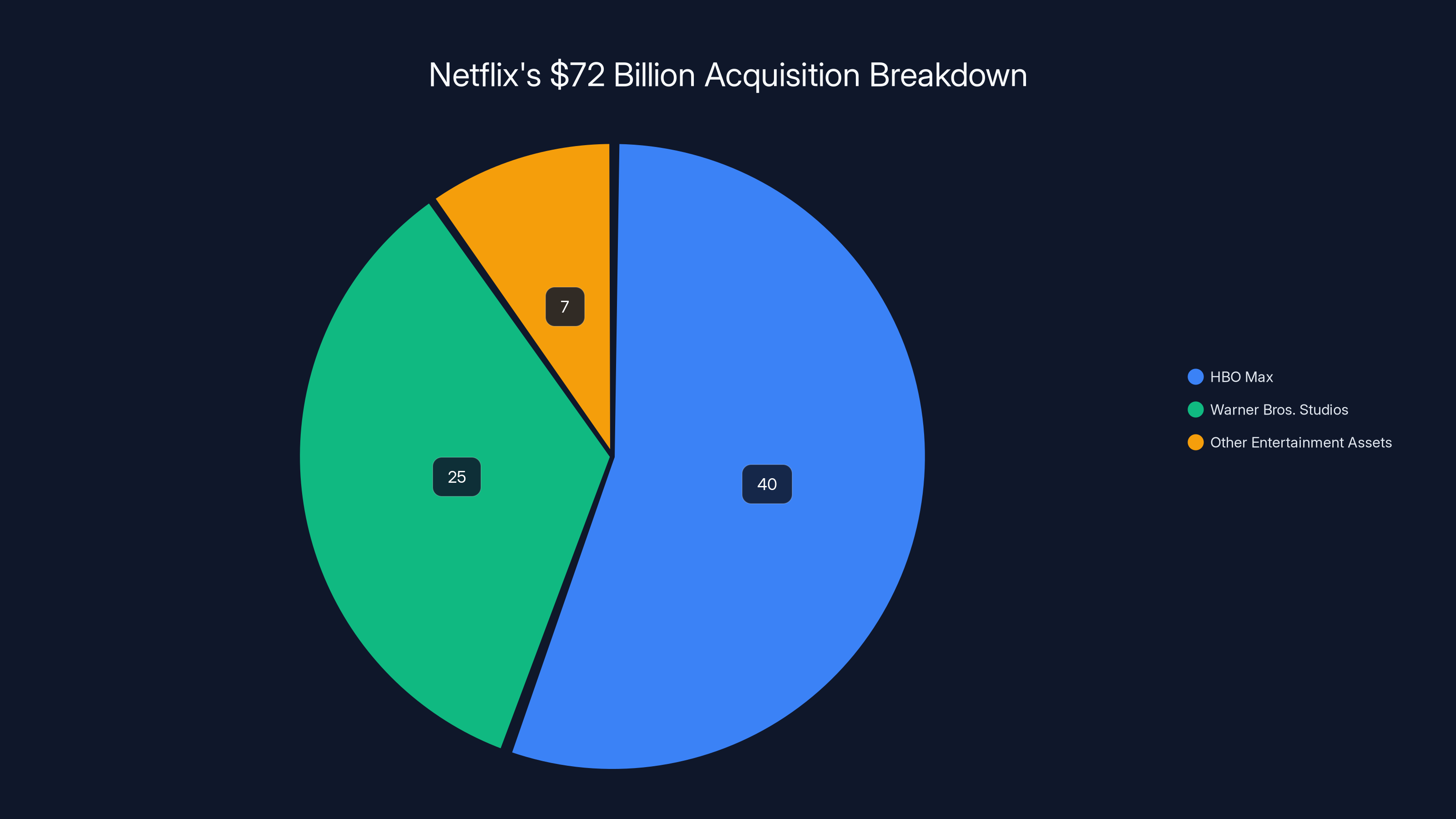

Netflix's offer is straightforward in concept but enormous in scale. The company is offering to pay $72 billion to acquire HBO Max (the streaming service), Warner Bros. Studios (the film and TV production powerhouse), and related entertainment assets. But critically, it's not acquiring the entire Warner Bros. Discovery company. It's leaving behind Discovery, the cable television division that owns channels like TLC, Animal Planet, and HGTV.

This surgical approach reveals Netflix's thinking. The company sees massive value in HBO Max's content library, the ability to cross-promote with Netflix's existing subscribers, and the production capability of Warner Bros. Studios. Studios don't just make content anymore. They're strategic assets that ensure a steady pipeline of original material, which is the actual currency of streaming success.

The

For shareholders, all-cash deals have a psychological premium. There's less execution risk. You get certainty of value rather than betting on a deal that might collapse or require renegotiation during the approval process. Netflix has proven it can execute large transactions, and its financial position is strong enough to absorb the capital outlay without breaking its business model.

The deal also comes with what the company calls a "limited waiver" from Netflix. This is key: Netflix agreed to let Warner Bros. negotiate with Paramount for seven days. It's a strategic move that makes Netflix look reasonable while simultaneously creating a deadline that pressures Paramount. Netflix essentially said, "Go ahead and try to beat us, but you have one week." That's confidence married with a poker tell. Netflix knows Paramount faces enormous challenges in financing a better offer.

Once Discovery gets spun off as a separate company, it becomes independently traded and managed. This creates complexity but also strategic clarity. The remaining Netflix-Warner Bros. combination would be purely focused on streaming and premium content production, without being dragged down by linear TV assets that are declining in value.

Here's something that doesn't get enough attention: HBO Max is valuable partly because it's a separate identity from Netflix. Combining them requires strategy. Netflix co-CEO Ted Sarandos argued to a Senate committee that HBO Max and Netflix are "complementary" rather than redundant. The idea is that different subscriber bases might prefer different interfaces, different pricing tiers, and different content curation. But in practice, most companies eventually merge such services for efficiency. That's a real integration risk that Netflix downplayed.

Netflix also positioned this deal as consumer-friendly. Sarandos told the Senate that "we are a one-click cancel, so if the consumer says, 'That's too much for what I'm getting,' they can cancel with one click." It's a libertarian argument: subscribers have power, so antitrust concerns are overblown. Whether regulators buy that argument is still uncertain, but Netflix is positioning for the regulatory fight that will definitely come.

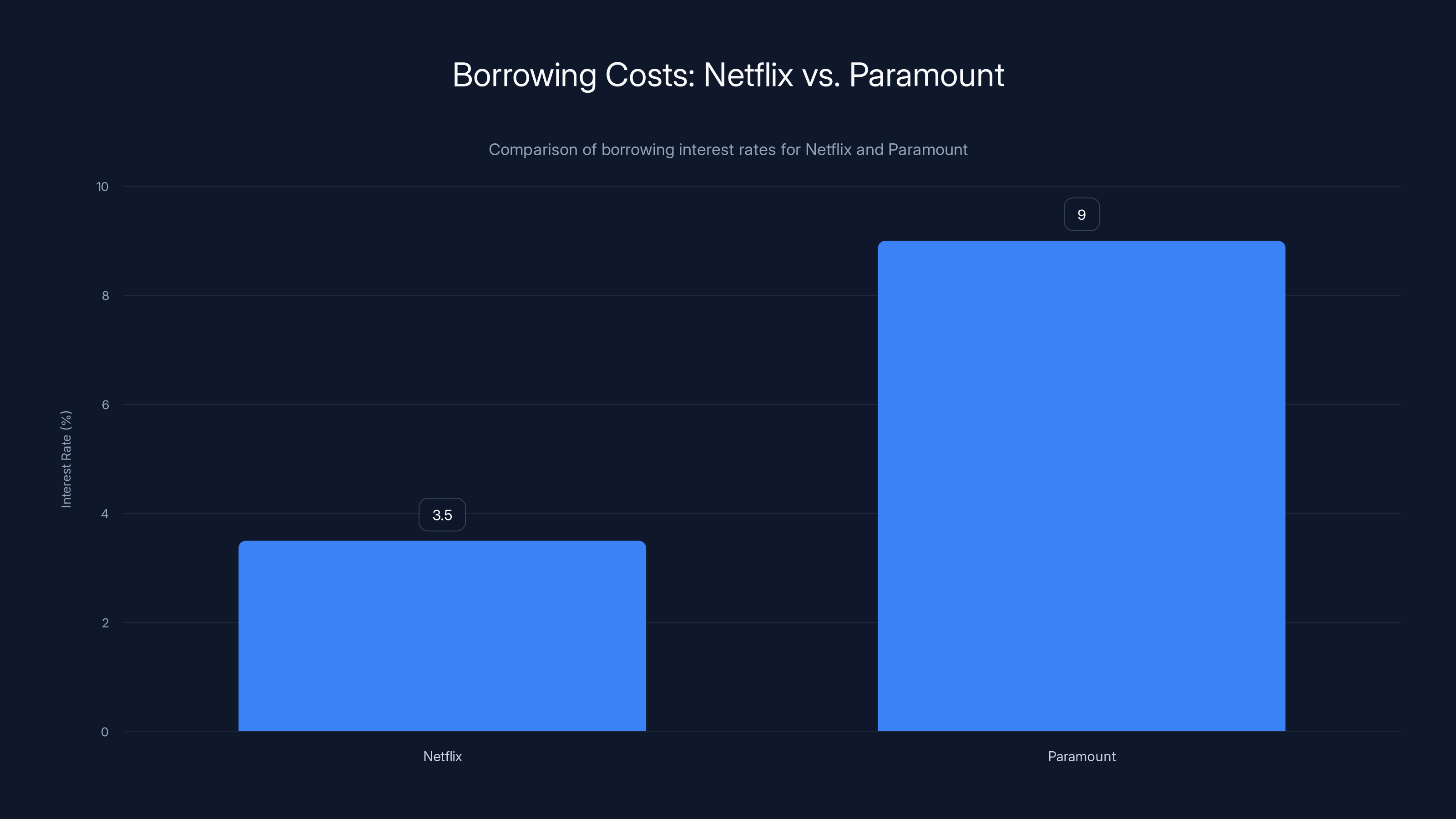

Netflix can borrow at significantly lower rates (around 3.5%) compared to Paramount's higher rates (around 9%), highlighting the financial advantage Netflix holds due to its investment-grade credit rating. Estimated data.

Paramount's Hostile Bid: The All-In Gamble

Paramount's approach is fundamentally different. The company is making a hostile takeover bid for the entire Warner Bros. Discovery company, including the cable division, the streaming service, the studios, and everything else. It's betting that buying the whole enterprise creates more value than selling pieces separately.

The initial offer was

Warner Bros.' board called Paramount's proposal "illusory" for exactly this reason. The word choice is brutal but accurate. An offer that requires extraordinary debt financing backed by a company with a junk credit rating, negative free cash flows, and significant fixed financial obligations is not the same as a cash offer from one of the world's most financially stable companies. The risk profiles are completely different.

Warner Bros. pointed to Paramount's specific financial situation: a $14 billion market cap, "junk" credit rating (meaning below investment grade), negative free cash flows (burning cash rather than generating it), significant fixed financial obligations (debt it's already committed to paying), and heavy dependency on its linear television business, which is in structural decline. Those aren't minor concerns. They're existential challenges for a company trying to finance a massive acquisition.

Paramount's strategy, though, has some internal logic. The company owns Paramount+, a streaming service that's been losing money. It also owns significant television and film production assets. The theory goes that integrating everything with Warner Bros. Discovery would create cost synergies, eliminate duplication, and allow the combined company to compete more effectively against Netflix and other streamers.

But here's the problem: synergy math doesn't always work in practice. Companies regularly overpay for acquisitions betting on cost savings that never materialize, or that take years longer to achieve than expected. Paramount is asking shareholders to bet that a highly leveraged combination of two struggling media companies will suddenly become competitive. That's not necessarily wrong, but it's definitely more speculative than Netflix's offer.

Paramount's proposal also came with less favorable legal terms. Warner Bros. said that Paramount's proposal gives Paramount the right to terminate or amend the deal, whereas Netflix's merger agreement is binding on Netflix and cannot be amended without Warner Bros.' consent. That's a massive difference. It means Paramount could potentially back out or change terms if something better came along, leaving Warner Bros. hanging. Netflix's offer has no such flexibility. The deal is locked in.

Additionally, Paramount wanted to restrict Warner Bros.' ability to manage its business while the transaction is pending. Netflix didn't impose such restrictions. From a shareholder perspective, being unable to operate your company freely during a long transaction approval process is costly. Every week of waiting is lost competitive opportunity.

One week before the deadline, Warner Bros.' board sent Paramount a letter with clear instructions. Increase your offer above $31 per share. Accept Netflix's legal terms. Provide security that you can actually complete this deal. Basically, prove that you're serious and that you can afford what you're promising.

Paramount scrambled during that final week. The question everyone in the financial markets was asking: Can Paramount actually come back with something that beats Netflix? Or was this a negotiating tactic, a way to create competitive tension and drive up the Netflix price slightly?

The Financial Reality: Cash vs. Leverage

When you strip away the corporate rhetoric and strategic positioning, this deal comes down to financial fundamentals. Netflix has the cash. Paramount doesn't.

Netflix generated massive free cash flow over the past several years. The company can finance a $72 billion acquisition using a combination of cash on hand and borrowing at favorable rates, given Netflix's investment-grade credit rating. The financial markets trust Netflix to borrow money at reasonable terms because the company has demonstrated profitability and cash generation. When Netflix borrows at 3% or 4%, the math works. The company generates more than enough cash to service that debt.

Paramount faces a completely different situation. The company would need to issue new debt at rates substantially higher than Netflix's, given Paramount's junk credit rating. If Paramount is borrowing at 8%, 9%, or even 10% (which is realistic for a junk-rated company financing a massive acquisition), the math becomes much harder. The combined company would need to generate enormous cash flows just to cover interest payments.

There's also the question of debt covenants. When banks lend large sums, they typically impose restrictions on the borrower's financial ratios, capital expenditures, and other parameters. Paramount's debt would likely include strict covenants that limit what management can do with the combined company. Netflix doesn't face those constraints because it's financing with cash and investment-grade borrowing.

The valuation math also matters. Paramount is offering

Historically, this is the playbook for most large acquisitions. The financially stronger company wins by offering certainty. Paramount's offer was bold, but Netflix's offer was safe. In the realm of multi-billion-dollar transactions, safe usually wins.

There's also a debt ceiling question. How much debt could Paramount actually raise for this deal? Banks have limits on how much they'll lend for any single transaction, especially one involving leveraged financing of an acquisition. Getting $50+ billion in acquisition financing for a struggling media company is a tall order, even with Paramount's assets as collateral. Investment banks might have refused to commit fully to financing the deal, which would have killed Paramount's bid before it even got serious.

Paramount's offer of

Legal and Contractual Complexity

Beyond the financial numbers, the legal structures of these deals matter enormously. Netflix negotiated a detailed merger agreement with specific terms that heavily favor Netflix. Paramount's proposal came with significantly different legal protections.

Netflix's merger agreement is binding, meaning Netflix cannot easily back out or change the terms. That's actually valuable to Warner Bros. shareholders because it means Netflix has committed to the deal and won't be tempted to renegotiate downward if circumstances change. Netflix also retained a "matching right," which means if Paramount comes back with a better offer, Netflix gets the chance to match it. This is standard in acquisition agreements and protects the first bidder.

Paramount's proposed terms were less shareholder-friendly. The company wanted the ability to terminate or amend the deal, which would have given Paramount an escape hatch if the transaction became inconvenient or if something better came along. Paramount also wanted to restrict Warner Bros.' ability to operate its business during the transaction period. That's a red flag because it limits management's flexibility and could cause competitive damage.

These legal differences matter because they reflect confidence levels. When a buyer is confident and strong, it can accept restrictive legal terms because it knows it will close the deal. When a buyer is less confident or more desperate, it often wants flexibility in case things change. Netflix's willingness to accept binding terms suggested confidence. Paramount's desire for flexibility suggested less certainty.

There's also the regulatory approval question. Any major media merger requires approval from the Federal Trade Commission and potentially other regulators. Netflix's merger agreement probably includes provisions about regulatory approval, breakup fees if approval is denied, and the conditions under which either party can walk away. Paramount's proposal likely had similar language, but the details matter. A deal that's contingent on FTC approval is riskier than one with contingencies already built in.

Warner Bros. management noted these legal differences explicitly in its February letter to Paramount. The company was essentially saying, "If you want us to consider your offer seriously, you need to match Netflix's legal certainty." That set the bar for Paramount's final offer. It wasn't just about price. It was about terms.

What This Means for Streaming Competition

Let's think about what each outcome actually means for the streaming market. That context matters because it explains why so many stakeholders—from regulators to consumers to competitors—care about which deal wins.

If Netflix wins, the market becomes more consolidated but also more clear. Netflix would own the premium movie and TV studios (Warner Bros.), the HBO Max library, and the combined subscriber base. The company would be even more dominant in streaming, but it wouldn't own linear television assets. Netflix becomes the pure-play streaming company, fully committed to digital distribution.

That's actually strategically smart for Netflix. The company has always been skeptical about linear television. Management believes streaming is the future and that owning cable channels would be a distraction. By acquiring Warner Bros.' content assets without the Discovery division, Netflix gets the best of what Warner Bros. owns without the ballast of legacy television business.

The Discovery spin-off becomes its own story. As an independent company, Discovery would own valuable cable networks and streaming assets. But it would be smaller, less well-capitalized, and potentially vulnerable to further consolidation. Other media companies might try to acquire it. Private equity firms might take it private. But Discovery would exist as a separate publicly traded company, at least initially.

If Paramount wins, the market consolidates differently. Paramount would own a combined entity with Paramount+, significant cable networks, the Warner Bros. studios, HBO Max, and Discovery channels. It would be a fully integrated media company with assets across streaming, linear television, and studios. The theory is that such integration creates efficiency and allows the company to compete on multiple fronts.

The problem is that Paramount would be a highly leveraged company carrying massive debt. That limits strategic flexibility. Every dollar of cash would go toward debt service rather than investment in new content, technology, or acquisitions. The company would be financially constrained, which might actually harm its competitive position compared to Netflix and other well-capitalized competitors.

From a consumer perspective, consolidation generally isn't great. More consolidated markets tend to have higher prices, fewer independent producers, and less diverse content. A Netflix-Warner Bros. combination would be extremely dominant, but at least it's transparent. A struggling Paramount trying to manage a highly leveraged combined company might just create chaos while attempting to reduce costs.

There's also the strategic question of whether anyone should want to own linear television assets right now. Cable television is in structural decline. Ad revenue is moving to digital platforms. Younger audiences don't watch cable. Networks are hemorrhaging subscribers. Buying into that legacy business is backward-looking. Netflix understood this and explicitly structured its offer to exclude those assets. Paramount, by wanting the entire company, is betting that legacy assets still have hidden value. That bet is increasingly looking like a losing proposition.

Netflix offers

The Regulatory Wildcard

Here's the thing nobody can predict with certainty: Will either deal get regulatory approval?

The Federal Trade Commission has been increasingly skeptical of media consolidation. A Netflix-Warner Bros. deal creates an even more dominant Netflix, which might trigger antitrust concerns. Netflix would control a massive library of content, own one of the largest streaming platforms, and have significant bargaining power with internet service providers, device manufacturers, and other distribution partners.

That said, Netflix has been making the argument that streaming is competitive, open-entry, and that consumers can switch with one click. The company has antitrust counsel making the case that the market isn't as concentrated as it appears because barriers to entry are low. Paramount+, Disney+, Apple TV+, Amazon Prime Video, and others can all compete. No single company locks up content in a way that prevents competition.

It's a reasonable argument, but it's also one that regulators might not buy. The FTC has challenged major tech mergers in recent years, and it might be in a skeptical mood. The outcome of a regulatory review is genuinely uncertain.

Paramount's deal faces different regulatory concerns. Combining Paramount with Warner Bros. would create the largest media conglomerate outside of the Netflix-owned entity, but it wouldn't create the same streaming dominance. However, regulators might worry about vertical integration. Paramount would control studios, distribution networks, cable channels, and streaming services all under one roof. That integrated control might raise antitrust concerns.

Historically, media mergers have gotten approved because regulators concluded that the combined entity would still face competition from other large media companies. But that playbook is changing as regulators become more concerned about media concentration generally.

The regulatory timeline also matters. Even if either deal is approved, the process could take 12-18 months. During that time, Warner Bros. is in transaction limbo. Management has limited ability to make long-term decisions. Employees and partners don't know if they're working for a Netflix subsidiary, a Paramount-owned company, or an independent Discovery entity. That uncertainty is costly.

The Shareholder Perspective: Voting, Value, and Certainty

Ultimately, this deal will come down to a shareholder vote. Warner Bros. Discovery shareholders will decide whether to approve the Netflix merger, and they might also have to vote on a Paramount alternative if the board decides it's worth putting to a vote.

Shareholders care about three things: the price, the certainty, and the terms. Netflix is offering

From a financial perspective, shareholders should evaluate these offers on a risk-adjusted basis. A dollar of certain value is worth more than a dollar of uncertain value. Financial theory tells us this, and practice confirms it. A highly confident buyer offering less money in all cash often wins a shareholder vote against a less confident buyer offering more money with debt.

Warner Bros.' board recommendation for Netflix carries enormous weight. Most shareholders vote with the board's recommendation unless there's a compelling reason not to. The board is saying that Netflix's offer is more likely to deliver superior value than Paramount's offer. That's a powerful endorsement.

But here's where timing matters. The board scheduled the Netflix shareholder vote for March 20. That's after Paramount's deadline of February 23. So the sequence is: Paramount makes its best offer on February 23, Netflix decides whether to match it, the board potentially revises its recommendation, and shareholders vote on March 20. That's a compressed timeline, but it gives the process some logical structure.

If Paramount comes back with something materially better—say

Shareholders would probably be satisfied with any deal at

Netflix's $72 billion offer is primarily focused on acquiring HBO Max and Warner Bros. Studios, with a smaller portion allocated to other entertainment assets. (Estimated data)

Content Strategy and Production

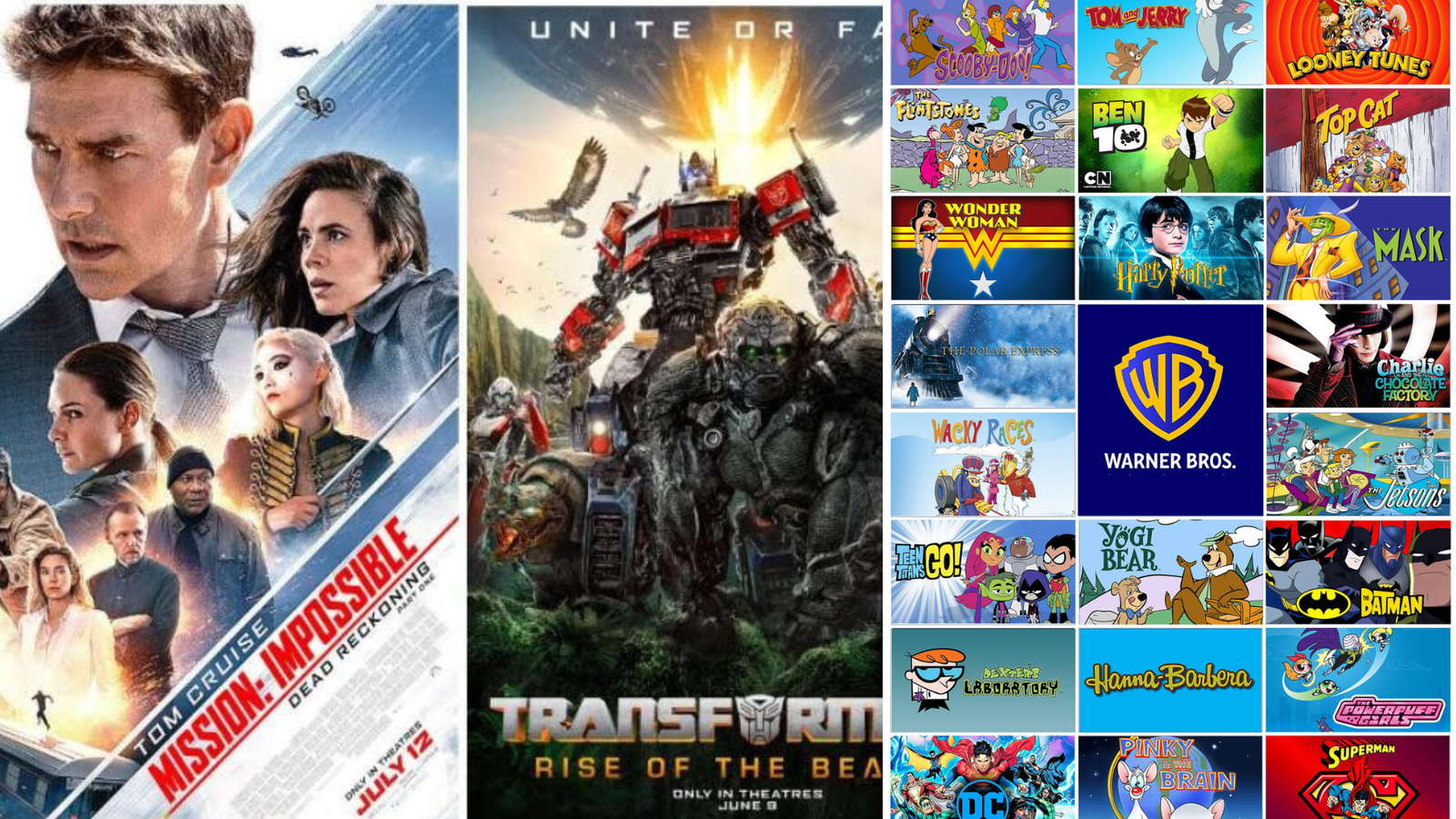

Beyond the financial mechanics, this deal matters because it determines what happens to one of the most important content production engines in entertainment. Warner Bros. Studios is the company that makes the films and television shows that drive Netflix's competitive position.

Under Netflix ownership, Warner Bros. Studios would become a Netflix subsidiary. The studio would produce content primarily for Netflix, though it might also license content to other platforms. Netflix would have total control over what gets made, how much gets spent, and what the creative direction should be. That sounds efficient, but it also reduces the studio's creative independence.

Netflix has a track record of micromanaging content to some degree. The company is data-driven and makes decisions based on subscriber metrics, viewing hours, and engagement data. That can lead to smart decisions, but it can also lead to formulaic content that plays it safe rather than taking risks. Great art sometimes comes from friction and creative disagreement. Full Netflix control might eliminate that friction.

Under Paramount ownership, Warner Bros. Studios would remain within a larger media company, but one that's financially stressed and highly leveraged. Paramount might actually have less ability to fund ambitious projects because so much capital would be going toward debt service. The studio might be forced to cut costs, reduce the number of projects, or focus on franchise material because original risks become harder to justify when you're servicing massive debt.

Neither scenario is perfect for the creative health of the studio. Netflix ownership offers stability and investment capital but also demands predictable, data-driven decision-making. Paramount ownership offers creative independence but financial uncertainty. Most creative leaders would probably prefer Netflix's stability, even with the constraints.

There's also the question of what gets made. Netflix is global-first. It makes shows designed to work for international audiences as much as domestic audiences. Paramount is more traditionally American. That different strategic focus would influence what stories get told and how they're told.

The HBO Max library is also important here. That library contains decades of television classics, movies, and premium content. Netflix would integrate that library into its global distribution system, making it available to Netflix subscribers everywhere. That's valuable for Netflix subscribers but might reduce the unique positioning of HBO Max as a premium service. Over time, HBO Max might disappear as a distinct brand, absorbed into the Netflix ecosystem.

The Discovery Question: What Happens to Cable Networks?

One element of this deal that doesn't get enough attention is what happens to Discovery, the cable television division. Under the Netflix deal, Discovery gets spun off as a separate public company. That's an enormous change.

Discovery owns networks like TLC, Animal Planet, HGTV, Discovery Channel, and others. These networks have loyal audiences, particularly older demographics that still watch television. Discovery also owns some valuable niche content that doesn't fit Netflix's model. The spinoff makes sense because Netflix doesn't want cable television assets and Discovery's content doesn't belong in Netflix's streaming-first model.

But spinning off Discovery creates a new challenge. As an independent company with a market cap probably under

Paramount's approach is different. Paramount wants to keep everything integrated. The theory is that Discovery's cable assets and Paramount's cable networks can be combined, redundancy eliminated, costs cut, and the combined entity can compete more effectively. But that's harder to achieve when you're highly leveraged and can't invest aggressively in transformation.

From a Discovery shareholder perspective, the Netflix deal might actually be worse. Discovery becomes independent but smaller and less well-capitalized. From a cable network perspective, the Paramount deal offers more resources and integration opportunities. But from a Paramount shareholder perspective, taking on that liability is expensive and risky.

So the Discovery question cuts both ways depending on whose perspective you take. Netflix shareholders win if Discovery gets taken off their hands. Discovery shareholders might lose by becoming an independent, declining asset. Paramount shareholders would bear the cost of integrating and managing that liability.

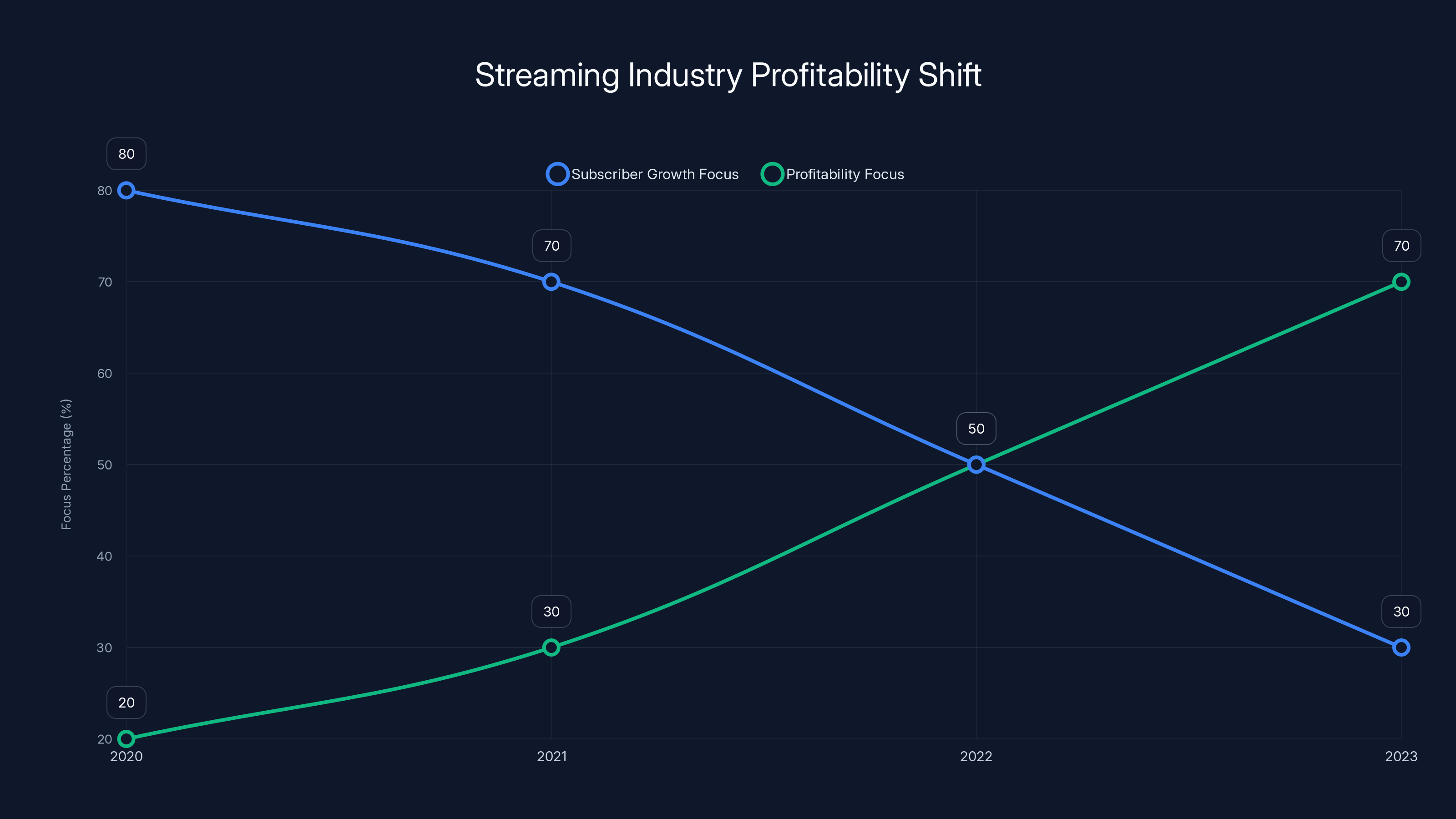

Estimated data shows a clear shift in the streaming industry from focusing on subscriber growth to prioritizing profitability from 2020 to 2023.

Strategic Timing and Market Context

The timing of this bidding war is also important context. Streaming has moved from growth phase to maturity phase. Netflix and Disney+ are now profitable. The industry is consolidating. Investors are demanding profitability over growth, and that changes the strategic calculus.

In 2020-2022, when streaming was red-hot, companies were willing to lose money to acquire subscribers. They spent lavishly on content, took losses, and justified those losses by projecting future profitability. That era is over. Now investors want profitable streaming. That means producing content more efficiently, raising prices, and focusing on unit economics.

Netflix pioneered this shift. The company stopped reporting subscriber metrics and started reporting profit and cash flow. That change signals that Netflix's priorities have shifted from growth to profitability. That influences what Netflix values in content and what kind of company Netflix wants to own.

Warner Bros. Discovery is profitable but also struggling with cord-cutting and the transition to streaming. The company's cable business is declining, and Paramount+ is losing money. That's why a buyer is interested. Netflix sees opportunity to rationalize Warner Bros.' content costs and integrate the business with Netflix's model. Paramount sees opportunity to gain scale and leverage.

The broader context is that entertainment consolidation continues because the economics favor scale. A large company with many content properties, global distribution, and significant bargaining power can compete more effectively than smaller competitors. That's why these mega-deals keep happening.

Precedent: Past Media Mergers and What They Tell Us

History provides useful context here. Past media mergers offer lessons about what happens when companies combine and what assumptions often prove wrong.

The AOL-Time Warner merger of 2000 is the cautionary tale everyone references. AOL paid $165 billion for Time Warner at the peak of the internet bubble. AOL was supposed to be the future, and traditional media was supposed to be declining. In reality, AOL's business model didn't work, the merger created culture clash, and the combined company underperformed for years. That deal is remembered as a disaster.

More recent deals have been more successful. Disney's acquisition of 21st Century Fox helped Disney secure valuable content assets and build its streaming position. Disney+ has become a competitive streaming service largely because of Fox content. That deal worked, partly because Disney had the capital to execute it properly.

Comcast's acquisition of NBCUniversal and subsequent deals helped Comcast build a vertically integrated media company. Those deals worked because Comcast had the financial resources and operational expertise to manage large, complex integrations.

The pattern suggests that deals work when the buyer is financially strong, has operational expertise, and doesn't overpay. Netflix qualifies on all three dimensions. Paramount qualifies on none of them. That's the fundamental difference.

Mergers also often involve hidden costs. Integration expenses can exceed projections. Talented employees leave. Duplicate functions are harder to consolidate than expected. Synergy projections rarely materialize exactly as modeled. These are abstract concerns, but they matter in practice. Netflix's all-cash deal can accommodate surprises. Paramount's leveraged deal cannot.

International and Regulatory Implications

Beyond the U. S. antitrust question, there are international implications. Netflix operates globally, and so does Warner Bros. A combined Netflix-Warner Bros. entity would have enormous market power in multiple countries.

British regulators, European regulators, Australian regulators, and others all have jurisdiction over parts of this business. Some of those regulators are even more skeptical of media consolidation than U. S. regulators. A deal that passes U. S. antitrust review might still face challenges elsewhere.

Paramount's deal faces similar international concerns. A large combined media company would have to navigate regulation in multiple jurisdictions. The difference is that Netflix is already used to operating globally and complying with international regulation. Paramount is less accustomed to those demands.

There's also the question of content regulation. Different countries have different requirements about local content, diversity, and other factors. A highly consolidated Netflix might face pressure to ensure diverse content and support for local creators. Those regulatory demands could constrain Netflix's decision-making.

International expansion is often where media deals create unexpected challenges. A buyer has to respect local sensibilities, work with local partners, and navigate different regulatory environments. Netflix has been doing this for years. Paramount would be learning while managing a highly leveraged acquisition. That's not ideal.

The Path Forward and Resolution

So what actually happens? Based on the financial and strategic analysis, Netflix's deal is more likely to close than Paramount's. Here's the likely sequence:

Paramount makes its best and final offer by February 23, probably somewhere in the

Paramount's bid doesn't disappear entirely, but it becomes a negotiating tactic rather than a viable path to acquisition. Paramount might make a higher offer, but Netflix's matching right essentially gives Netflix the final say, and Netflix's financial position ensures it can match any realistic bid.

The deal then faces regulatory review. The FTC might challenge it, but Netflix's arguments about competitive streaming markets and low switching costs are reasonable. Most likely, the deal gets approved with some commitments from Netflix about content diversity or other concerns.

By mid-2026, the deal closes. Netflix integrates Warner Bros. and HBO Max. Discovery goes through a complex spinoff process. The entertainment industry consolidates further. Streaming competition continues, but with Netflix in an even more dominant position.

For consumers, the most immediate effect is probably prices. Netflix might raise prices or create new pricing tiers to monetize HBO Max content. Bundling options might emerge. But overall, fewer major streaming services and higher prices seem likely.

Implications for Streaming's Future

This deal is about more than just one acquisition. It signals where streaming consolidation is headed and what the competitive landscape will look like for the next decade.

Streaming started with the premise that there would be many services, each offering unique content, and consumers would subscribe to multiple services. That vision is dead. The economic reality is that streaming is expensive to produce for, profitability requires scale, and most households don't want to pay for 10 different subscriptions. Consolidation was inevitable.

By acquiring Warner Bros., Netflix is securing its position as the market leader for another decade. The company gets the best content assets, the strongest production capabilities, and the most diversified content library. Competitors like Disney, Amazon, Apple, and Paramount still have assets, but Netflix becomes further ahead.

Paramount's failed bid signals that traditional media companies struggle to compete in the streaming era. Paramount needed to acquire Warner Bros. to have a realistic path to competing with Netflix. The fact that it couldn't finance that deal shows the financial realities of the industry. Companies that were dominant in linear television (Paramount, Paramount) lack the financial resources to dominate in streaming (Netflix).

The industry is consolidating toward a few large players: Netflix, Disney (with ESPN, ABC, Disney+), Amazon (with Prime Video and production capability), Apple (with Apple TV+ and capital resources), and possibly a weakened Paramount. That's a much less competitive landscape than we had five years ago.

For creators, the consolidation matters because it means fewer buyers for content. A handful of large companies control distribution, and they have significant bargaining power over creators and producers. That could lead to more standardized content, fewer risks, and less diversity. Or it could lead to those companies competing more aggressively for talent and novel content. It could go either way.

For consumers, fewer services, higher prices, and potentially less choice are likely outcomes. But there's also a possibility that better-resourced companies can create higher quality content and better experiences. It's a trade-off without a clear winner.

FAQ

What is the Netflix deal with Warner Bros.?

Netflix is offering to pay

How does Paramount's counter-offer compare to Netflix's deal?

Paramount is making a hostile takeover bid for the entire Warner Bros. Discovery company, including the cable division, for

Why does the financing structure matter in acquisition deals?

All-cash deals close with certainty because the buyer has the funds available. Deals requiring large debt financing depend on banks' willingness to lend and are subject to debt covenants that restrict what the buyer can do. Additionally, a buyer with junk credit ratings pays higher interest on borrowed money, which reduces the economic value of the combined company. Netflix's investment-grade credit rating means it can borrow money more cheaply than Paramount, and an all-cash offer eliminates execution risk.

What happens to Warner Bros. Discovery shareholders if Netflix wins?

Shareholders would receive $27.75 per share in cash, eliminating uncertainty about the deal's completion. They would no longer own Warner Bros. shares but would have capital to reinvest elsewhere. The company would be taken private (as a Netflix subsidiary), so there would be no publicly traded Warner Bros. anymore. Discovery would be spun off as an independent company, creating a separate investment opportunity for those who want exposure to cable networks.

Could the FTC block either of these deals?

Both deals face potential regulatory challenges. The Netflix deal might trigger antitrust concerns about streaming consolidation, although Netflix argues that streaming is a competitive market where consumers can easily switch services. Paramount's deal faces fewer streaming consolidation concerns but might trigger vertical integration concerns about owning studios, cable networks, and streaming services simultaneously. Both deals will require FTC approval, but the Netflix deal is more likely to succeed given Netflix's arguments about competitive markets and consumer choice.

What would happen to Discovery as a company if Netflix wins?

Discovery would be spun off as a separate, publicly traded company owning cable networks like TLC, Animal Planet, HGTV, and the Discovery Channel. As an independent entity, Discovery would be significantly smaller and less well-capitalized than the integrated Warner Bros. Discovery company. The spinoff creates uncertainty about Discovery's long-term viability as cable television continues its structural decline, and the company might eventually be acquired by another media company or forced to transform significantly.

Why is Netflix willing to offer less per share than Paramount if Netflix is confident in the deal?

Netflix is confident that its all-cash, all-binding offer is more valuable to shareholders than Paramount's higher-priced offer with debt financing and less certain terms. The financial markets consistently price certainty at a premium. A shareholder would rather accept

What do industry consolidation trends tell us about the future of streaming?

The consolidation indicates that streaming is transitioning from a growth phase with many competitors to a maturity phase with fewer, larger players. The economics of content production and distribution favor scale. Companies that lack financial resources (like Paramount) struggle to compete against well-capitalized competitors (like Netflix). Over the next decade, we're likely to see a landscape with 4-5 major global streaming competitors and many smaller, niche players. This consolidation will result in fewer choices for consumers, likely higher prices, and more bargaining power for large media companies.

Conclusion: What This Deal Means

The Warner Bros.-Netflix merger represents a decisive moment in entertainment industry consolidation. Netflix's superior financial position, proven execution capability, and clear strategic vision give it enormous advantages over Paramount's more speculative counterbid. While the outcome isn't predetermined, the financial and strategic realities strongly favor Netflix.

For shareholders, the Netflix deal at around $27.75-29 per share offers reasonable value with certainty of payment. For consumers, the deal signals the end of the era of abundant streaming choice and the beginning of a more concentrated market. For the entertainment industry, this merger confirms that capital-rich technology companies (Netflix) have more power than traditional media companies (Paramount) in the streaming age.

The regulatory question remains open. The FTC might challenge the deal on antitrust grounds, and international regulators might impose conditions. But absent a major regulatory surprise, Netflix's deal is likely to close by mid-2026, reshaping the entertainment landscape once again.

What makes this deal consequential isn't just the money involved. It's what the deal signals about power dynamics in entertainment, the decline of traditional media companies, and the consolidation of content and distribution into fewer hands. By mid-2026, Netflix won't just be the largest streaming service. It will be the largest content producer, the largest streaming distributor, and the company with the most bargaining power with studios, creators, and viewers. That's a shift in power that will echo through the industry for years to come.

The one-week deadline that Warner Bros. gave Paramount wasn't arbitrary. It was a recognition that Paramount's financial constraints made it unlikely to mount a credible counterbid. Netflix knew it, Paramount knew it, and Warner Bros.' board knew it. What we're watching in this final week of February 2026 isn't really a competitive bidding war. It's a negotiation about whether Netflix needs to pay more to get the deal done, and how much more Netflix is willing to pay to ensure victory.

Unless Paramount pulls off a surprise that few financial observers expect, Netflix's deal will close. The streaming landscape will consolidate further. And the era of multiple competing streaming services will be replaced by a market dominated by a few giants. That's the future this deal is creating, even if that future is hidden beneath the corporate-speak and financial jargon of the merger announcement.

Key Takeaways

- Netflix's 27.75/share) is more valuable than Paramount's higher-priced but debt-dependent counterbid ($31/share) due to certainty and financial strength

- Paramount's junk credit rating means it would pay 8.5% interest on debt vs Netflix's 3.5% borrowing rate, creating billions in additional costs over the life of the deal

- Warner Bros. gave Paramount one week (through February 23) to make a better offer, after which shareholders would vote on the Netflix deal March 20

- Netflix's deal creates a dominant streaming giant while spinning off Discovery as an independent company focused on declining cable television assets

- The merger signals the end of competitive streaming abundance and the beginning of a consolidated market dominated by 4-5 major players with higher prices and fewer choices

Related Articles

- Apple's Severance Acquisition: Vertical Integration Strategy [2025]

- Tell Me Lies Season 3 Episode 8 Release Date: Hulu & Disney+ Guide [2025]

- SAG-AFTRA vs Seedance 2.0: AI-Generated Deepfakes Spark Industry Crisis [2025]

- MST3K Kickstarter Revival Brings Back Original Cast and Crew [2025]

- Antitrust Chief Gail Slater Resigns Amid Netflix-Warner Merger Review [2025]

- How to Listen to The Archers Free From Anywhere [2025]

![Warner Bros. Netflix Merger vs Paramount Deal: Full Analysis [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/warner-bros-netflix-merger-vs-paramount-deal-full-analysis-2/image-1-1771349851997.jpg)