The Viral Moment That Shook Hollywood

Last week, something genuinely unsettling went viral. A fight scene featuring likenesses of Tom Cruise and Brad Pitt, generated entirely by AI through Seedance 2.0, hit social media with the kind of momentum that breaks the internet in about six hours. And honestly? The quality was disturbing. The movement felt natural. The faces looked right. You'd have to watch it twice to catch the tells.

But here's what really matters: within hours of the video spreading, SAG-AFTRA, the union representing film and television actors, released a statement calling it "unacceptable." Not just problematic. Not "concerning." Unacceptable.

The statement zeroed in on something that keeps union executives awake at night: deepfakes undercut the ability of human talent to earn a livelihood. And they're right to be worried. This wasn't some low-quality deepfake you'd find buried in a Reddit thread. This was polished, professional-grade synthetic media that could theoretically replace an actor's image without consent, payment, or negotiation.

The timing matters too. This happens while the entertainment industry is still smarting from the 2023 strikes, when actors and writers fought explicitly over AI protections. Those protections won them certain concessions, but they also made clear that the real battle—the one over synthetic humans and digital likenesses—was still ahead.

So what exactly happened with Seedance 2.0? Why did SAG-AFTRA respond so forcefully? And what does this mean for actors, studios, and the future of synthetic media? Let's dig in.

TL; DR

- The Incident: A viral AI-generated fight between Tom Cruise and Brad Pitt likenesses created with Seedance 2.0 prompted immediate backlash from SAG-AFTRA

- Union Response: SAG-AFTRA called the deepfake "unacceptable," arguing it undermines actors' ability to earn and control their image rights

- Core Issue: AI-generated deepfakes can replicate celebrity likenesses without consent, payment, or negotiation—a major threat to acting jobs

- Broader Problem: Current AI tools lack sufficient guardrails against unauthorized synthetic media creation

- What's Next: Expect stricter regulations, contractual language, and possible legislation protecting actor likenesses from unauthorized AI use

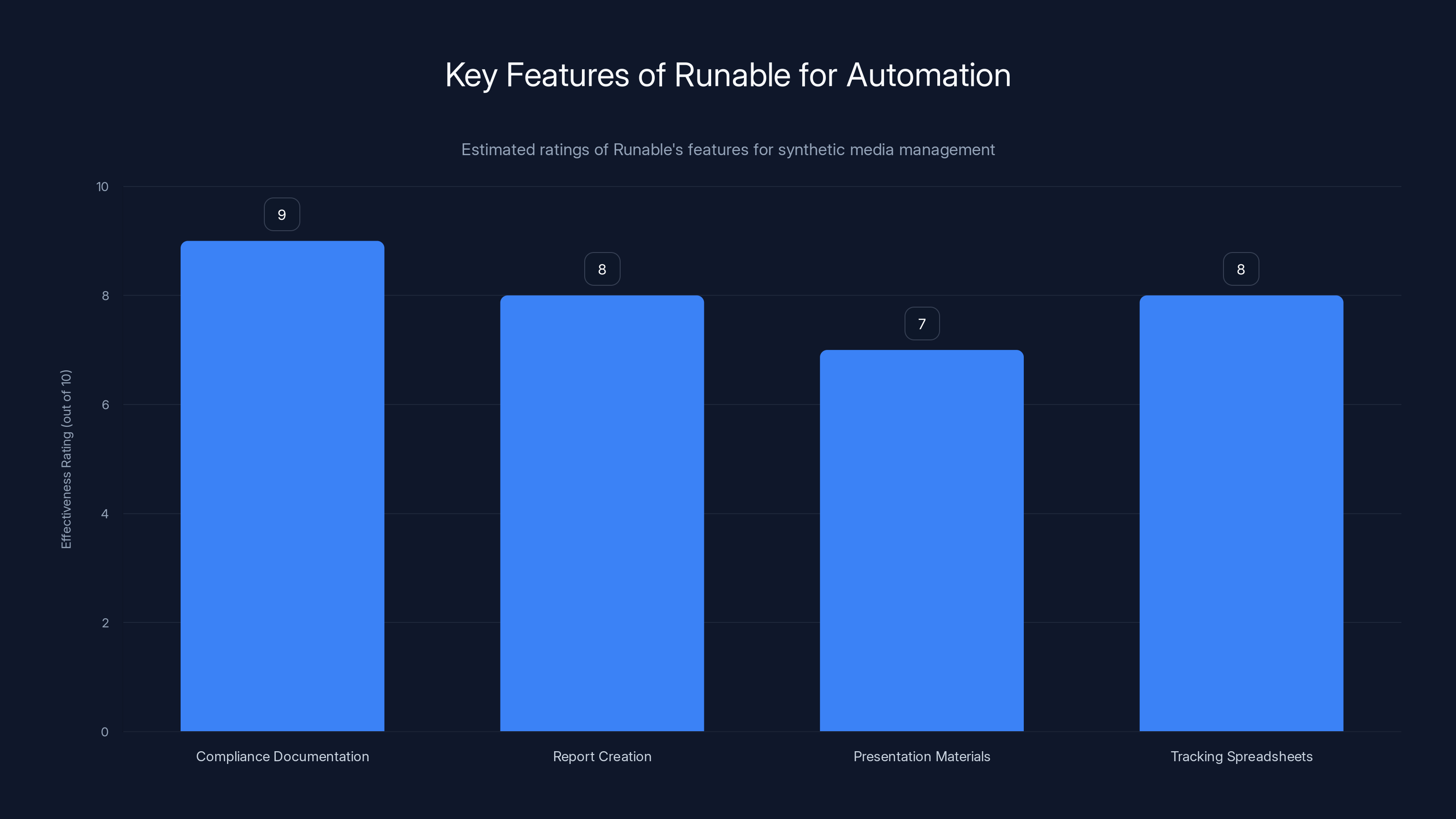

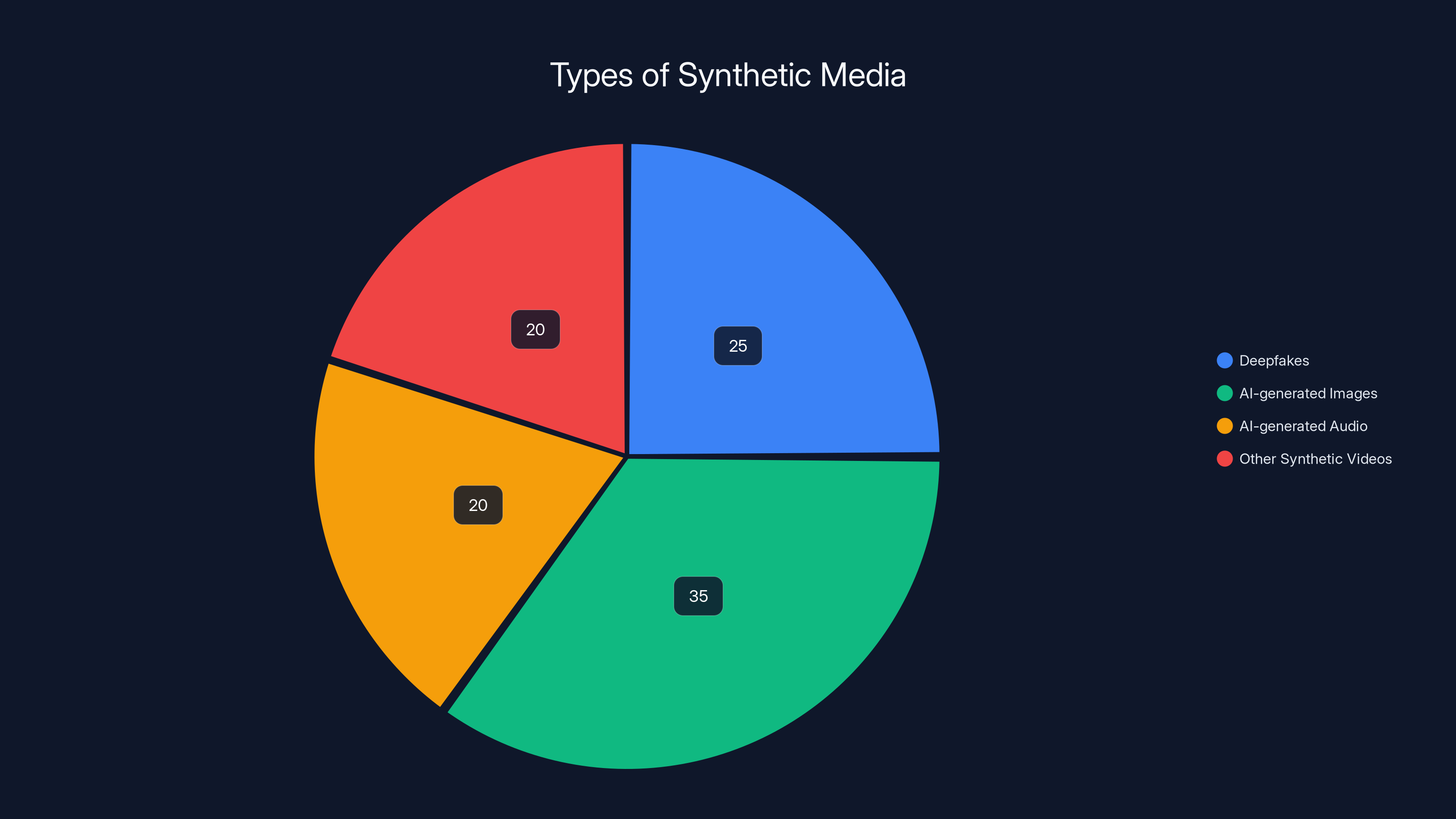

Runable's automation features are highly effective, particularly in generating compliance documentation and tracking spreadsheets. Estimated data.

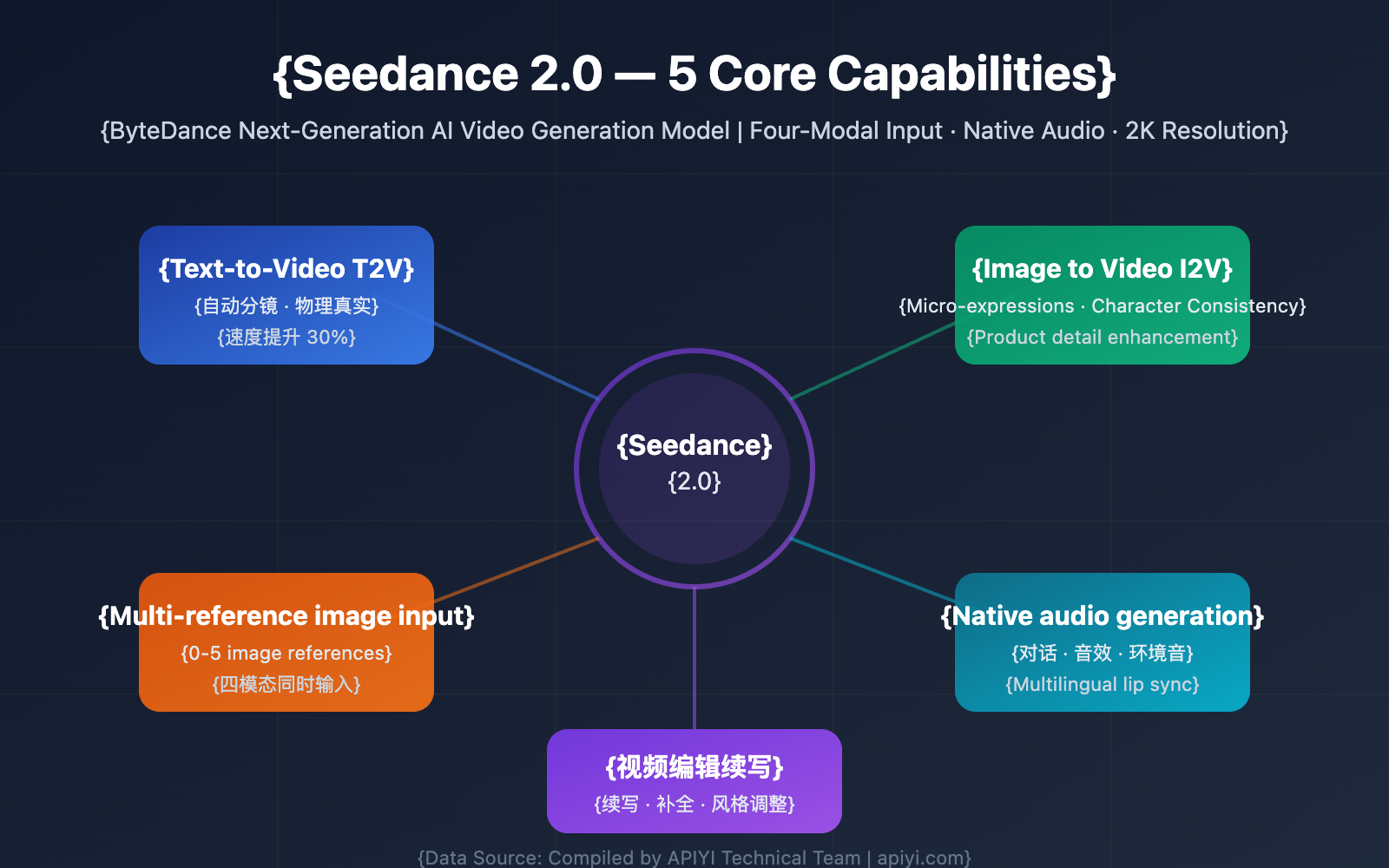

Understanding Seedance 2.0: The Technology Behind the Controversy

Seedance 2.0 isn't some obscure research project. It's a generative AI video model that's become increasingly accessible to creators with basic technical skills. The platform falls into a category of AI tools designed to generate, manipulate, and synthesize video content from text prompts, images, or other reference materials.

What makes Seedance 2.0 particularly concerning is its capability to preserve facial likeness across motion. Earlier deepfake technology required extensive training data of a specific person's face. Seedance 2.0 can work with comparatively little source material—sometimes just a few frames or images—and extrapolate convincing movement and expression that feels authentic.

The mechanics work like this: the model takes input data (a description of an action, plus reference images of a face), runs it through neural networks trained on vast video datasets, and outputs synthetic video that blends the likeness with the requested motion. It's not perfect yet, but the gap between "obviously fake" and "plausibly real" has collapsed in the last 18 months.

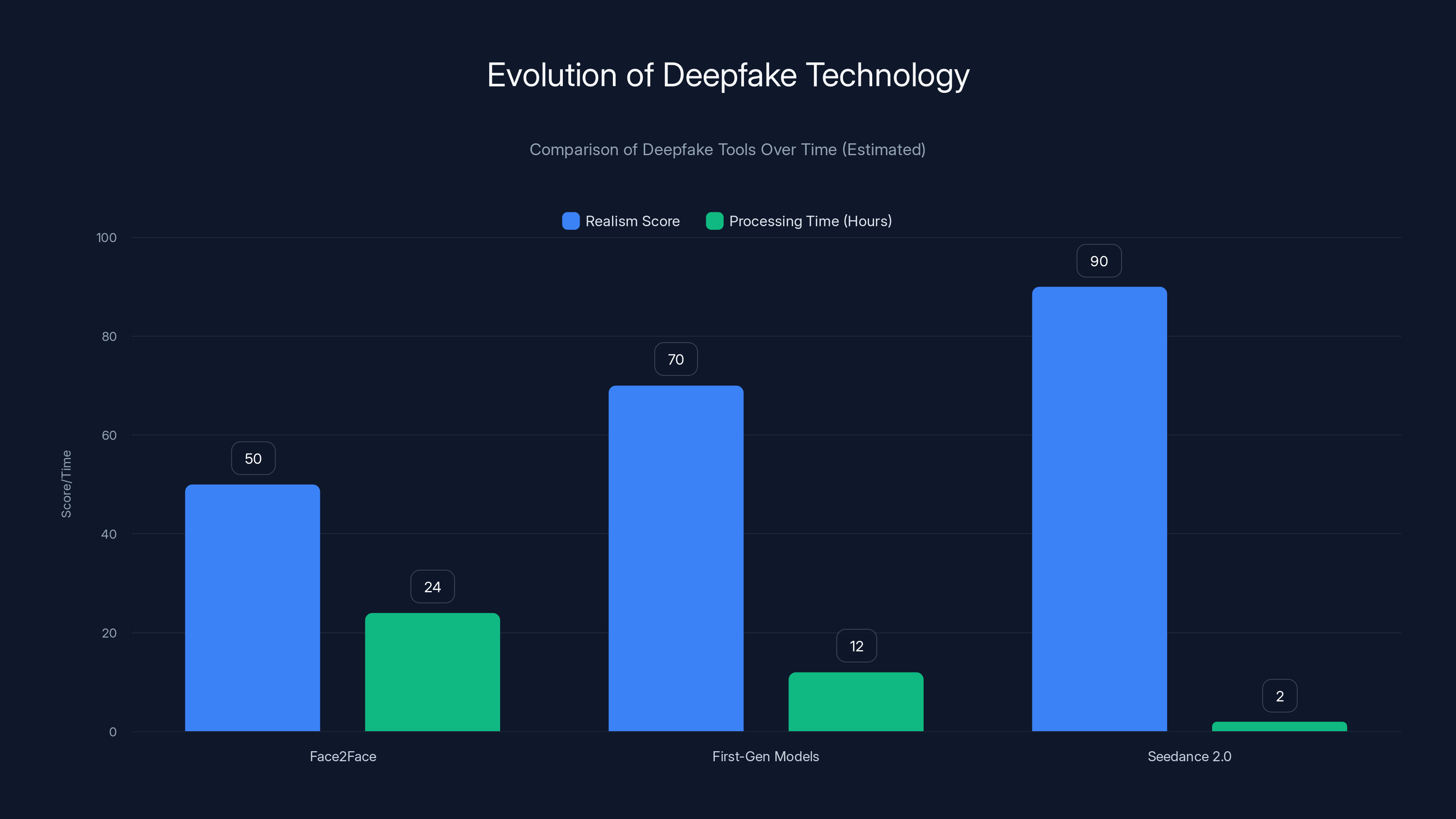

For context, this represents a significant leap from earlier deepfake tools like Face 2 Face or even first-generation generative video models. Those required obvious artifacts or processing time that gave them away. Seedance 2.0 produces output fast enough that creators can iterate, refine, and ship in hours rather than days.

The Pitt-Cruise fight video specifically demonstrates this capability. The choreography had weight. The impacts registered. The facial expressions tracked with the movement. Most critically, anyone watching without knowing it was AI-generated might not immediately catch it. And that's precisely the problem.

What's important to understand is that Seedance 2.0 isn't being sold as a tool specifically for making unauthorized deepfakes. It's being positioned as a creative tool for filmmakers, visual effects artists, and content creators. The marketing emphasizes legitimate use cases: rapid prototyping, VFX iteration, background synthesis, and on-demand video generation.

But like many powerful tools, the gap between intended use and actual use is massive. You can't control what creators do with the technology once it's in their hands. And that's where the SAG-AFTRA conflict starts.

Why SAG-AFTRA's Response Matters: The Livelihood Argument

Let's be direct about what SAG-AFTRA is actually arguing here. It's not just "this is weird and creepy." It's more fundamental: unauthorized synthetic media creation threatens the economic foundation of acting as a profession.

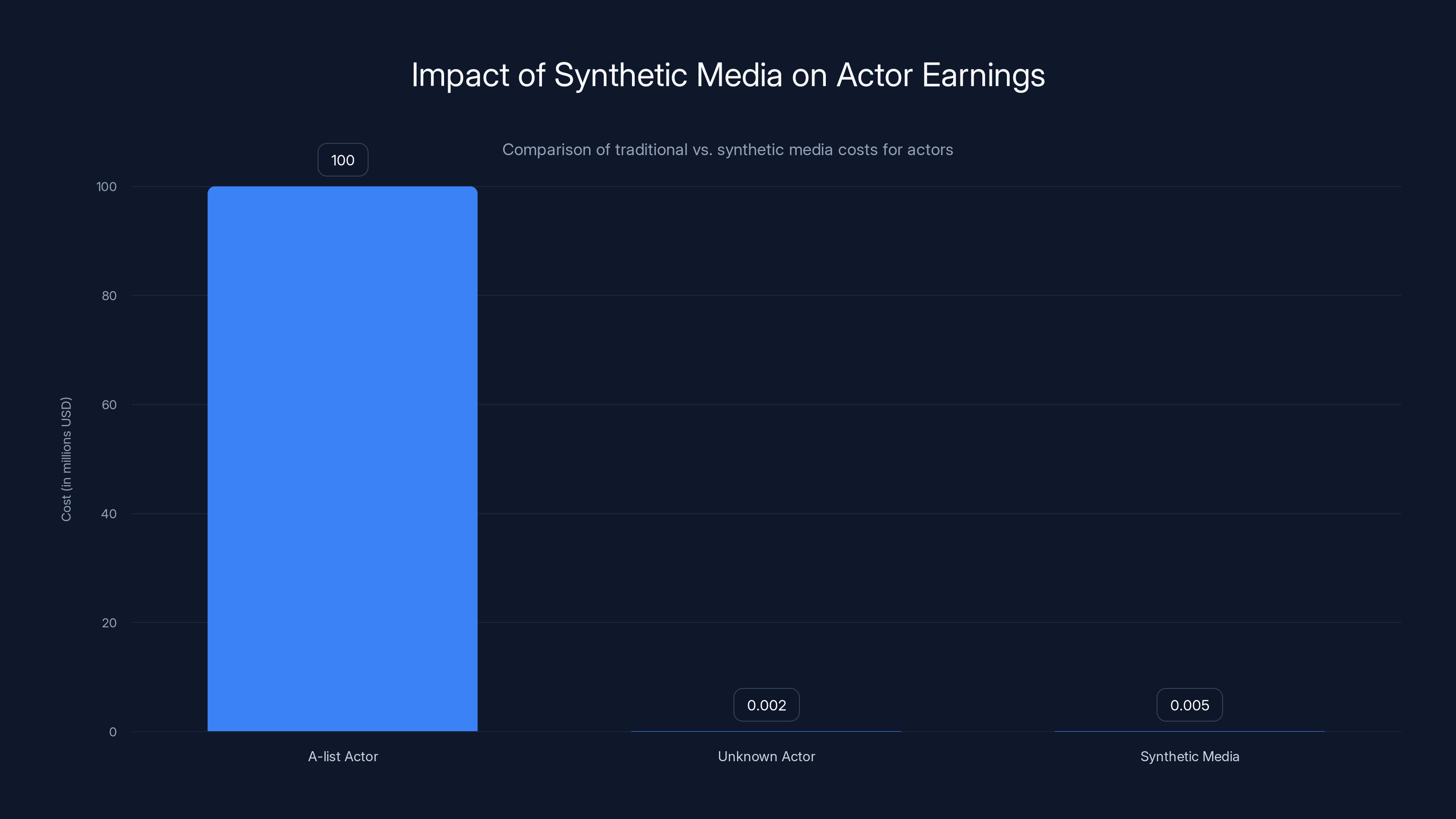

Consider the economics. An actor's primary asset is their likeness—their face, voice, movement patterns, and the audience recognition attached to those elements. Studios pay for that. Productions budget for it. It's the reason Tom Cruise can command **

Now imagine a studio could license Cruise's likeness from Seedance 2.0 for

The union's statement specifically mentioned that deepfakes "undercut the ability of human talent to earn a livelihood." This isn't hyperbole. It's a direct articulation of a genuine economic threat. And it applies not just to A-list stars, but to character actors, background actors, voice actors, and stunt performers.

Consider a few realistic scenarios:

Scenario 1: The Stunt Replacement. A stunt coordinator could potentially use Seedance 2.0 to synthesize dangerous action sequences, eliminating the need to hire (and insure) professional stunt performers. Stunt work is already precarious; this would devastate the profession almost overnight.

Scenario 2: The International Market. A studio shooting in a low-budget territory could synthesize actor faces using likenesses of American stars, avoiding the cost of hiring them or even paying them market rates. The synthetic Cruise does the scene for free; the real Cruise sees no compensation.

Scenario 3: The Recast Continuity. An actor dies or becomes unavailable mid-production. Instead of recasting or reshooting, the studio synthesizes the remaining scenes using their likeness from footage already shot. This is already happening in limited form (see the Princess Leia sequence in Rogue One), but it's becoming automated and faster.

Scenario 4: The Resurrection Market. A deceased actor's estate could license their likeness to studios indefinitely. Which means Marilyn Monroe, James Dean, and Humphrey Bogart could theoretically "act" in new films forever, with no residuals paid to their families and with no ability for them to choose roles that align with their legacy.

The union's argument is that without explicit protections—contractual language, regulatory guardrails, technological safeguards—actors lose control over one of their primary economic assets. And once that control is lost, it's nearly impossible to regain.

Seedance 2.0 shows a significant leap in realism and reduction in processing time compared to earlier deepfake tools. Estimated data.

The 2023 Strike Context: AI Was Always the Real Battle

To understand why SAG-AFTRA's response carries so much weight, you need to understand what happened in 2023. Actors and writers both struck that year, and while the headlines focused on streaming residuals and job security, AI protection was the subtext running through every negotiation.

When the strikes ended, both unions won explicit language protecting against unauthorized use of performer likenesses in AI-generated content. The agreement required that studios get explicit consent before using an actor's likeness synthetically, and it mandated additional compensation if they did.

But here's the catch: those protections only apply to work within the studio system. They don't apply to independent creators, amateur filmmakers, content creators on Tik Tok, or random people using Seedance 2.0 to make viral videos. The Pitt-Cruise fight video wasn't made by a major studio. It was made by someone with access to a generative video tool and a creative impulse.

Which means the 2023 agreement, while important, actually highlights the real problem: the technology is democratized, but the legal protections are only for unionized professionals working with major employers. That leaves a massive gap.

SAG-AFTRA's response to the Pitt-Cruise video is essentially saying: "The guardrails we negotiated don't matter if anyone with a laptop can create this." And they're right. A studio might respect contractual obligations, but a random creator in Lithuania has no such incentive.

This is what makes the Seedance 2.0 incident particularly significant. It's not a violation of the 2023 agreement (since no studio was involved). It's a demonstration that the 2023 agreement doesn't actually solve the underlying problem. The technology is moving faster than the law.

The Deepfake Detection Problem: Why We Can't Just "See" the Fake

Part of why SAG-AFTRA's response is so intense has to do with detection difficulty. There's an assumption that "good fakes" will eventually become obviously fake if you look closely enough. But that assumption is increasingly wrong.

Generative video models like Seedance 2.0 don't create artifacts the way early deepfakes did. They don't have the uncanny-valley-ness or the weird eye movements or the hair that phases through itself. Modern models output video that's genuinely convincing to the human eye under normal viewing conditions.

This matters because it means we can't rely on audience skepticism or visual literacy to protect us. The Pitt-Cruise fight video went viral because it was good. If it had been obviously fake, it wouldn't have spread. And that's a problem for everyone from actors to news organizations to platforms trying to prevent misinformation.

Detection technology exists (specialized AI trained to spot deepfakes), but it's:

- Not foolproof

- Constantly falling behind as synthesis improves

- Not deployed at scale on social media platforms

- Expensive to implement across billions of videos

So we're in a genuinely awkward position: the technology to create convincing synthetic video is widely available and easy to use, but the technology and institutional infrastructure to detect and label it is scattered, inconsistent, and always playing catch-up.

This is why some security researchers and policy experts argue that the solution isn't better detection, but rather better provenance tracking and watermarking systems that make it obvious when content is synthetic. But that requires buy-in from AI vendors, social platforms, and creators—and we're nowhere close to consensus on that front.

Legal and Rights Issues: Who Owns Your Face?

Here's where things get genuinely complicated. US law doesn't clearly establish that you have a fundamental right to your own likeness. There's something called the "right of publicity," which is stronger in some states than others, but it's not uniform nationwide.

Your face isn't automatically your intellectual property. Which means that if someone creates a synthetic version of you, the legal landscape for stopping them is murky.

In California (where the entertainment industry is centered), the right of publicity is relatively strong. You can sue if someone uses your likeness for commercial purposes without consent. But that right is limited:

- It only applies to commercial use (free speech wins for commentary, parody, news)

- It requires proving damages (which is hard with synthetic media)

- It's expensive to litigate

- It often only covers monetary compensation, not injunctions

Meanwhile, other states have weaker protections. And international law is all over the place.

What makes this worse is that AI training data has become a legal battleground. The Verge and other outlets have reported extensively on lawsuits against major AI companies for training on copyrighted images without permission. But even those cases are ambiguous. The legal system hasn't definitively ruled on whether using images to train generative models constitutes infringement.

Apply that ambiguity to actor likenesses, and you get a situation where:

- Studios might have trained Seedance 2.0 on actors' faces without explicit consent

- Independent creators can use Seedance 2.0 to synthesize those faces without any legal consequence

- Actors have legal recourse, but it's expensive, slow, and uncertain

SAG-AFTRA's response is partly a legal argument ("this violates our members' rights") and partly a political argument ("this needs to be illegal and we're going to make noise until it is").

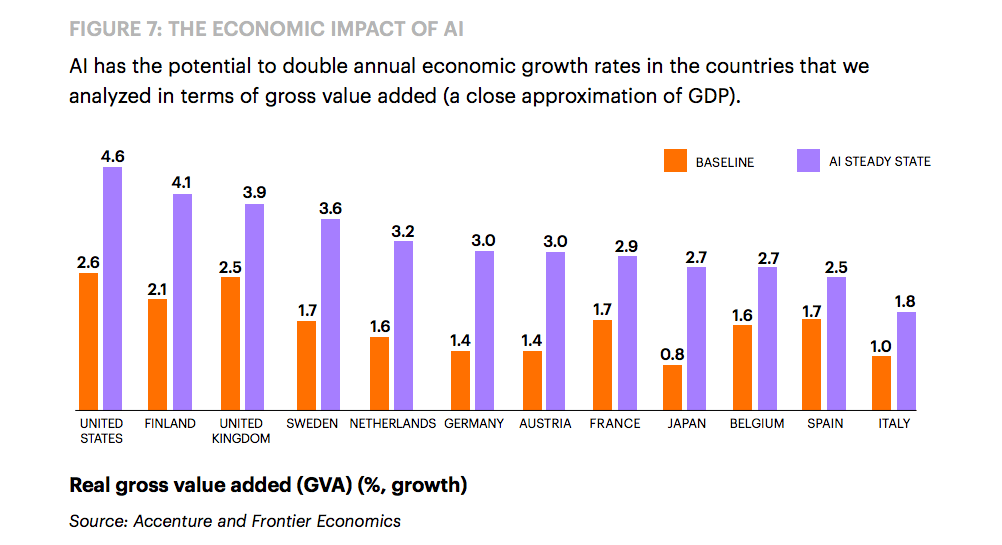

Estimated data shows that synthetic media could drastically reduce production costs, posing a significant threat to traditional actor earnings.

The Platform Problem: Why Twitter and Tik Tok Can't (or Won't) Stop Deepfakes

The Pitt-Cruise video spread because social media platforms allow it. These platforms operate under the assumption that they're "neutral conduits" for user-generated content. They're not responsible for what users upload, only for responding when someone reports it.

But with synthetic media, that framework breaks down. The platforms don't have the tools—or the incentive—to proactively identify and remove deepfakes before they spread. You Tube and Tik Tok have both announced policies against deepfakes, but enforcement is inconsistent and dependent on reports.

This creates a perverse situation: the easier it is to create synthetic media, the easier it spreads, but the harder it becomes for platforms to moderate at scale. A human moderator can't watch every video and assess whether it's synthetic. Automated systems are still unreliable. So deepfakes proliferate until someone specifically reports them.

For the Pitt-Cruise video, by the time it was reported and platforms began removing it, it had already gone viral. Millions of people had seen it. The replication had begun (other creators making similar content). The cultural moment had passed.

Platforms argue they're doing what they can within technical and legal constraints. But from SAG-AFTRA's perspective, "doing their best" isn't good enough when members' livelihoods are at stake.

There's also a secondary platform problem: creator tools. Discord servers, Reddit communities, and Git Hub repositories have become informal distribution networks for Seedance 2.0 and similar tools. Someone can download the model weights, install dependencies, and start synthesizing in under an hour.

Platforms hosting these communities could theoretically ban discussions of synthetic media creation. Some do. But most treat it as a gray area—not explicitly allowed, but not aggressively removed either.

How Seedance 2.0 Actually Works: The Technical Details

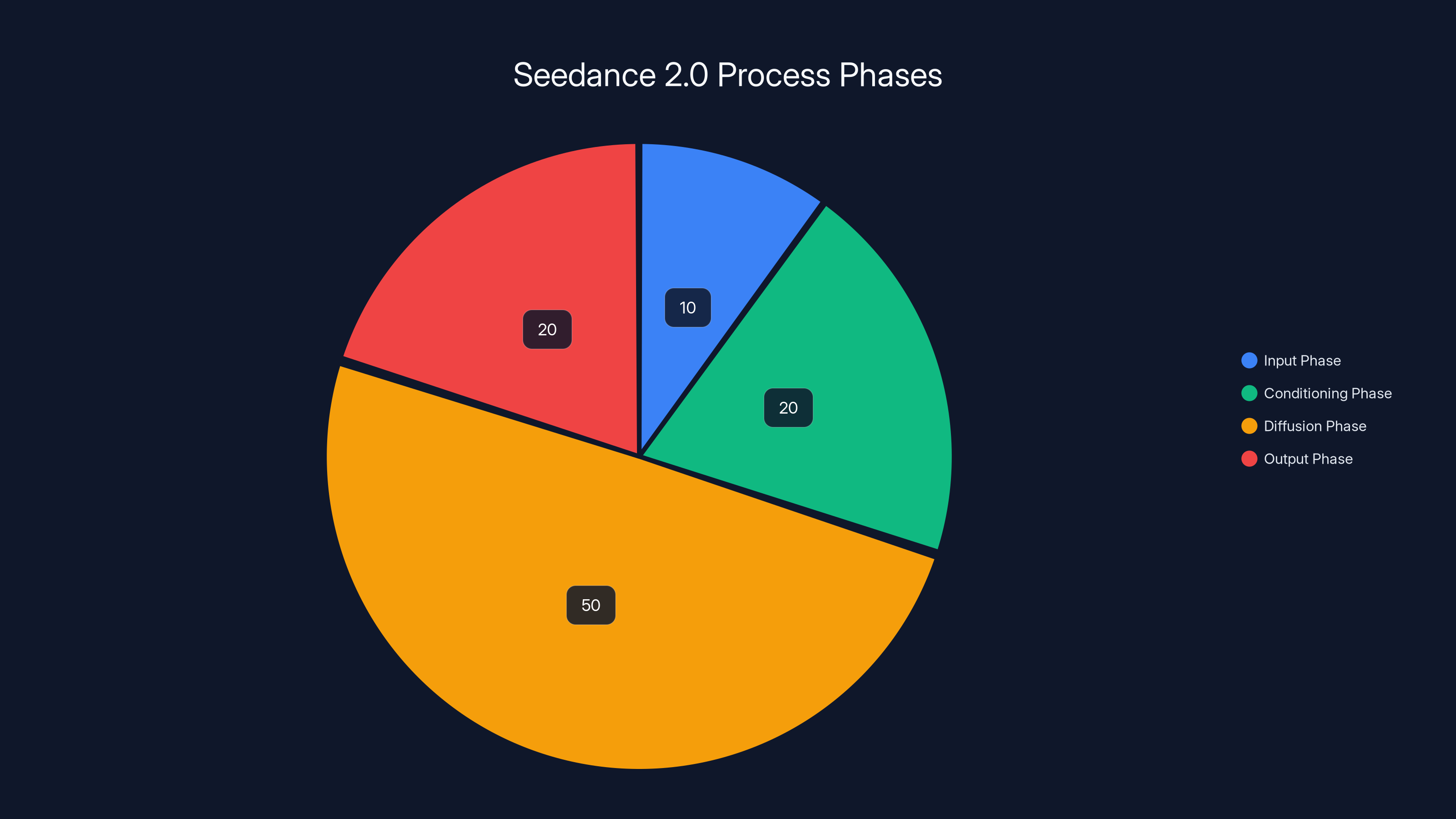

Understanding the mechanics helps clarify why this is such a hard problem to solve. Seedance 2.0 uses a technique called "diffusion models," which work by learning to progressively add detail to an image or video based on text prompts.

The process looks roughly like this:

- Input Phase: You provide a text description ("Tom Cruise and Brad Pitt fighting") plus optional image references of the people you want to include

- Conditioning Phase: The model conditions on your input, essentially saying "generate video that matches this description and resembles these faces"

- Diffusion Phase: The model iteratively refines random noise into coherent video, adding details at each step

- Output Phase: You get a fully rendered video at whatever resolution and duration you specify

The critical innovation in Seedance 2.0 is that it can condition on faces while maintaining overall consistency. So you can say "person A's face" and it will keep that face consistent throughout a 30-second video, including realistic expression and lip-sync.

This is technically impressive. It's also the exact feature that makes it dangerous for unauthorized deepfake creation.

The model was trained on massive video datasets (mostly publicly available video from the internet). That means it's learned patterns about how faces move, how bodies interact, how lighting and shadows work. It's not actually creating entirely new data; it's extrapolating based on learned patterns.

But here's what matters: the model doesn't "know" whether the face it's synthesizing belongs to Tom Cruise or your neighbor. It's just matching the visual input to the learned patterns. Which means there's no built-in safeguard preventing its use for unauthorized deepfakes. The safeguards have to be external (terms of service, law, ethics) rather than technical.

Industry Response: Studios, Tech Companies, and Regulatory Pressure

The Pitt-Cruise incident triggered responses across the industry, each highlighting different concerns and priorities.

SAG-AFTRA's Formal Position: The union called for stronger legal protections, platform responsibility, and contractual language requiring consent and compensation for synthetic media use. They're also advocating for disclosure requirements—any video using synthetic human likenesses should be clearly labeled.

Studio Responses: Major studios (the companies represented by the Academy) are split. Some recognize that stricter deepfake protections align with their labor agreements and union relations. Others see generative video as an emerging opportunity and want to preserve access to the technology.

Realistically, studios see opportunity here. Synthetic media could eventually reduce their dependency on actor availability, reduce insurance costs, and enable rapid iteration. They want to control the use of synthetic actors, not ban it entirely.

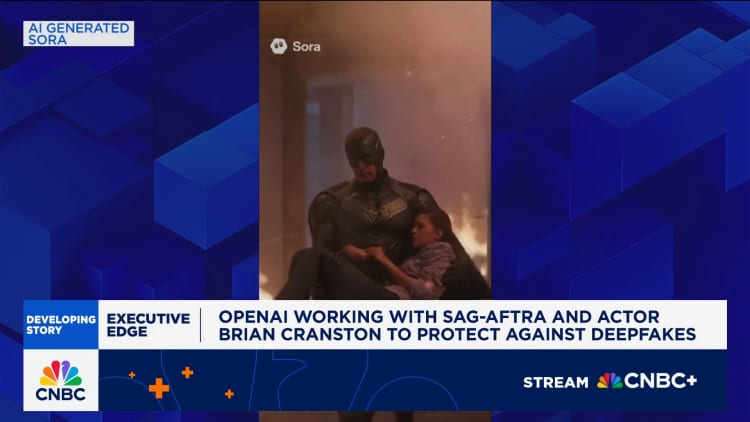

Tech Company Responses: Stability AI (which funds Seedance 2.0 development) and other AI vendors have released statements about responsible deployment. They've added terms of service restrictions against using the tool to create deepfakes of real people without consent. But enforcement is unclear.

AI companies argue that banning the technology isn't realistic—it's open-source, distributed, constantly being improved. The better approach is responsible release, clear guidelines, and supporting detection tools.

Regulatory Responses: Several jurisdictions are moving toward synthetic media legislation. The EU's proposed AI Act includes provisions for disclosing synthetic media. Various US states are considering deepfake laws. But these are still emerging and inconsistent.

The challenge is that regulation is slow, and technology is fast. By the time a law passes prohibiting unauthorized synthetic media creation, there will be five new techniques for creating synthetic media that technically aren't covered by the law.

Estimated data shows the Diffusion Phase takes the most time, highlighting its complexity in refining video details.

The Compensation Problem: How Would Actors Get Paid?

This is the question that actually keeps union negotiators awake. Let's say we agree that creators should pay actors when they use their likenesses synthetically. How does that actually work?

We have some models from the digital media industry. A musician gets royalties every time their song is streamed. A photographer gets residuals when their image is licensed. An actor gets paid when they appear in a film.

But synthetic media breaks those models. Here's why:

The Attribution Problem: How do you know whose likeness was used? If a creator synthesizes a crowd scene using 200 people's faces, do all 200 get paid? How much? Based on what metric?

The Derivative Works Problem: If I create a synthetic video of Brad Pitt, then you remix my video and create something new, who gets paid? The original actor? The original creator? Both?

The Consent Problem: If an actor's likeness is used in contexts they wouldn't have consented to (pornography, political messaging, commercial products they don't endorse), do they still get paid? Or do they get paid more?

The Scale Problem: Actor payments currently work at the project level (you're hired for a film, you get paid a flat rate). But synthetic media could involve millions of micro-uses—a second of an actor's face in thousands of videos. Tracking and paying for that is logistically nightmarish.

Some proposals involve blockchain or smart contracts that automatically track synthetic media use and distribute payments. Others suggest collective licensing models where studios license broad rights to actor likenesses upfront.

But none of these solutions are currently deployed, and they all have problems. Which means for now, the conversation is still at the "we need protections" stage, not yet at the "here's how we'll compensate actors" stage.

Ethical Considerations: Beyond Legal Rights

Some of the deepest concerns about synthetic media are genuinely ethical rather than legal. A creator might be technically within their rights to synthesize a video, but ethically, should they?

Consider a few scenarios:

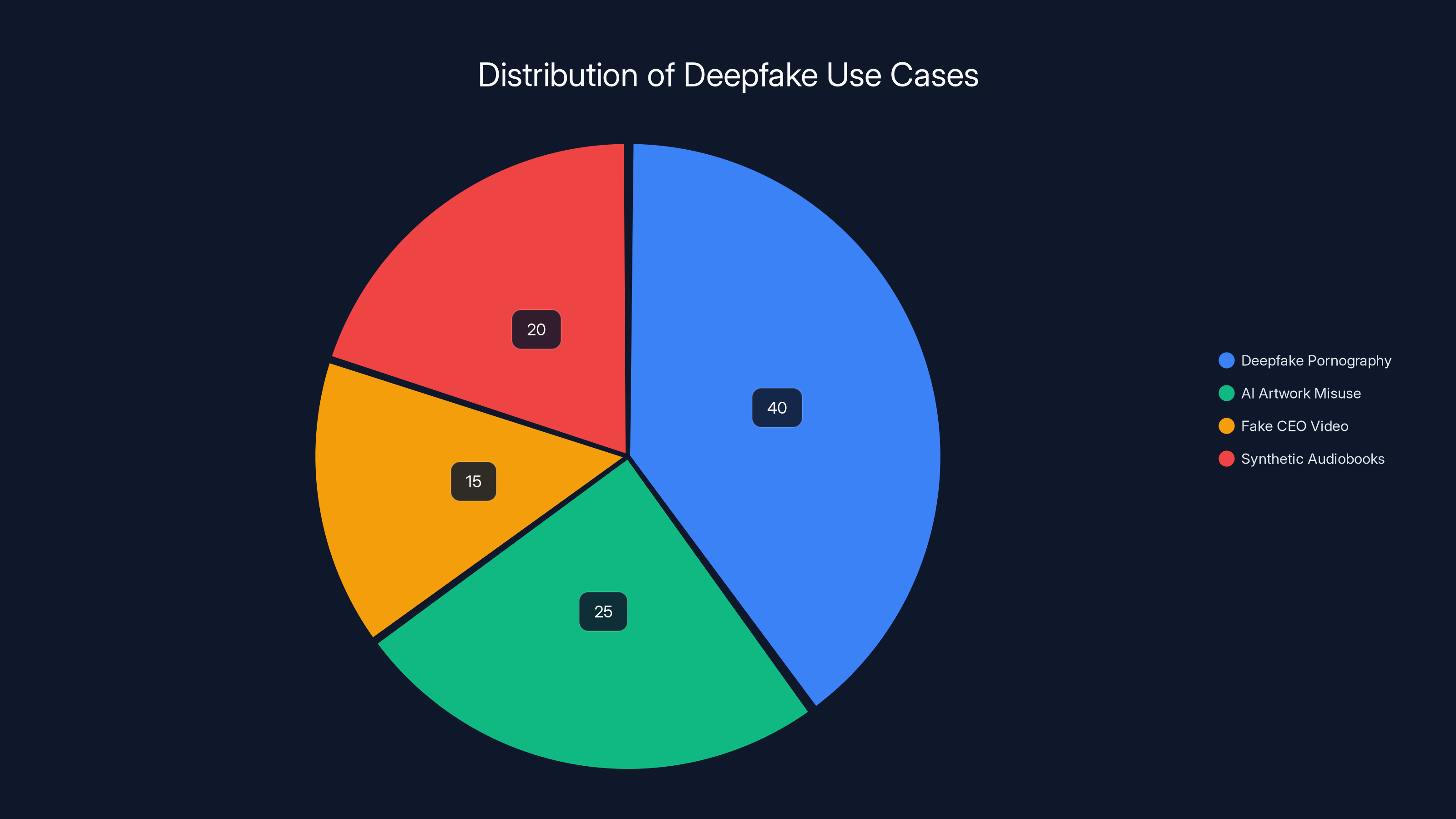

Synthetic Celebrity Pornography: This is already happening at scale. Deepfake pornography predominantly uses celebrities' faces without consent. It's demeaning, violating, and often illegal under revenge porn laws, but prosecution is rare. Synthetic media makes it easier and faster.

Political Deepfakes: Synthetic videos of political figures saying things they never said could swing elections. Even if ultimately detected as fake, the initial spread might be sufficient to influence voters. This is a genuine national security concern.

Misinformation: A synthetic video of a CEO announcing unexpected layoffs could tank a stock price before the company can issue a correction. A synthetic news conference from a government official could cause public panic.

Dignity and Consent: Setting aside legal rights, there's a basic ethical principle that people should be able to control how their image is used. Being synthesized into content you didn't consent to and wouldn't endorse is a violation of that principle, even if the law is unclear.

These concerns aren't unique to SAG-AFTRA. The Electronic Frontier Foundation has written extensively about deepfakes and consent. Researchers at various universities have published papers on the psychological harm of synthetic media. Even tech companies developing generative video are increasingly acknowledging the ethical dimensions.

But ethics is hard to regulate. You can't legally mandate ethics. The best you can do is create norms, provide education, and hope that people choose to do the right thing.

SAG-AFTRA's response is partly an ethical stand: "Creating synthetic versions of our members without consent is wrong, and we're going to make noise about it."

The Future Scenario: What Synthetic Media Adoption Looks Like

If this issue isn't resolved through strong protections and enforcement, here's what synthetic media adoption in entertainment could look like in five years:

Small Studios and Streamers: Start using synthetic media to reduce production costs. Hiring unknown actors, synthesizing their faces onto action scenes performed by stunt performers. Reduces per-film budgets by 20-30%.

International Markets: Studios create films shot in one country with synthetic actors speaking multiple languages, each performance lip-synced to local languages. Dramatically reduces localization costs.

Talent Agency Disruption: Some talent agencies start representing synthetic actors, offering studios "digital performers" that are cheaper, more controllable, and never go to rehab or demand residuals.

Legacy Content Expansion: Studios synthesize deceased or retired actors into new films, creating endless sequels and prequels without needing to negotiate with anyone.

Misinformation Epidemic: Synthetic videos become sufficiently common and convincing that authentic footage loses credibility. Media literacy becomes a critical skill. Trust in video evidence collapses.

Regulatory Whiplash: Governments and platforms start banning or heavily restricting synthetic media, but it's too late—the technology is already distributed and decentralized. Enforcement becomes a game of whack-a-mole.

This isn't inevitable. It's just what happens if we continue on the current trajectory without meaningful intervention. And that's why SAG-AFTRA's response matters. It's a signal that actors, studios, and society need to decide proactively how synthetic media gets developed and used.

Estimated data shows deepfake pornography as the most prevalent use case, followed by AI artwork misuse and synthetic audiobooks. Estimated data.

What Stronger Protections Would Look Like

Based on what unions are advocating for and what policy experts suggest, here's what a more protective framework might include:

Disclosure Requirements: Any synthetic media involving real people's likenesses must be clearly labeled as synthetic. Not just in fine print—visibly labeled. AI-generated videos should start with a clear watermark or announcement.

Consent Requirements: Creating synthetic media of a real person's likeness requires explicit consent, with clear specification of how the synthetic version will be used, distributed, and monetized.

Compensation Standards: Usage of synthetic likenesses includes compensation tied to the type of use (commercial, editorial, archived, etc.). A standard rate sheet similar to what photographers and musicians use.

Platform Responsibility: Social platforms must have mechanisms to identify, label, and remove unauthorized synthetic media. They're liable if they host synthetic media of real people without consent.

Technology Accountability: AI vendors and platforms must implement technical safeguards (watermarking, consent verification) and must maintain audit logs of who created what synthetic media and how it was used.

Right of Removal: Individuals have the right to request removal of unauthorized synthetic media of themselves from all platforms and services.

Criminal Penalties: Creating synthetic media specifically intended to deceive (synthetic political videos, deepfake pornography) becomes a crime with meaningful penalties.

Intellectual Property Protection: Actor likenesses are explicitly protected under right of publicity laws, with those protections extending to synthetic versions of their likeness.

None of these exist uniformly across jurisdictions. Some exist in limited form. Most are still being debated.

Case Studies: Deepfakes in the Wild

To understand why SAG-AFTRA's concerns are justified, consider how synthetic media is already being used:

Example 1: The Deepfake Pornography Epidemic: In 2023, researchers estimated over 14,000 deepfake pornographic videos existed online, with 96% depicting women. These videos have been used for harassment, blackmail, and revenge. Many women had no idea synthetic pornography of them existed until it spread online. The emotional and reputational damage is permanent.

Example 2: The Lensa AI Artwork: In late 2022, an app called Lensa AI went viral for turning selfies into artwork. What many users didn't realize was that Lensa had been trained partly on copyrighted artwork by professional artists, and users had agreed (in terms they probably didn't read) to commercial use of their image data. The app sold art derived from people's likenesses, with artists and users getting nothing.

Example 3: The Fake CEO Video: In 2020, a deepfake video purporting to show Elon Musk smoking weed went viral. The video was fake, but it spread before people realized it. Early detection was only possible because the fake was low quality—higher quality versions in the future might not be caught as quickly.

Example 4: The Audiobook Narration: Authors and voiceover artists have begun finding synthetic audiobooks of their work created with AI-generated voices trained on their own recordings. They receive no royalties or attribution.

These aren't theoretical concerns. They're happening now, at scale, with real people being harmed.

Technical Defenses: Watermarking, Detection, and Verification

One approach to addressing synthetic media is technical: make it easier to identify and verify authenticity. Several techniques are being developed:

Cryptographic Watermarking: Embed a digital signature into images and videos that proves authenticity and origin. If a video has been synthetically altered or generated, the watermark changes or disappears. Challenge: creators might remove watermarks, and watermarks can be imperceptible to viewers.

Content Authentication (C2PA): Developing industry standards for tracking the provenance of content. A photo would include metadata documenting who took it, when, with what device, and any edits applied. If content is synthetically generated, that's documented too. Challenge: adoption is slow and inconsistent.

Synthetic Media Detection AI: Training AI to detect deepfakes by identifying patterns typical of generative models. Works with varying success depending on the sophistication of the deepfake. Challenge: detection is always behind synthesis—as deepfakes improve, detection becomes harder.

Biometric Verification: Using facial recognition, voice authentication, and other biometric techniques to verify that video matches a known authentic recording of a person. Challenge: privacy concerns, effectiveness against sophisticated deepfakes.

None of these solutions is foolproof. And they all require buy-in from creators, platforms, device manufacturers, and AI vendors to be effective at scale.

Estimated distribution shows that AI-generated images make up the largest portion of synthetic media, followed by deepfakes and other types. Estimated data.

The Political Dimension: Why This Matters Beyond Entertainment

SAG-AFTRA's response might seem like a labor dispute specific to entertainment, but it reflects broader anxieties about AI's impact on work, identity, and trust.

Actors aren't the only profession vulnerable to synthetic media. Voice actors could be replaced by voice synthesis. Visual artists could see their style replicated without compensation. Musicians could have synthetic versions created. Writers could have their voices imitated.

In each case, the concern is the same: technology that makes it easier to create, cheaper to produce, and harder to control access to a person's primary economic asset (their unique skills, voice, appearance).

Beyond that, there's a question about trust and authenticity in a world where synthetic media is common and difficult to detect. If you can't trust video evidence, what can you trust? How does society function if seeing isn't believing?

This is why some political figures and institutions are taking synthetic media seriously. The White House has released statements about AI deepfakes and misinformation. Various governments are considering legislation. Congress has held hearings specifically on deepfakes and election security.

SAG-AFTRA's response is part of a larger reckoning about how society adapts to AI capabilities that exceed our existing legal and ethical frameworks.

International Variations: How Different Countries Are Responding

Protections against unauthorized synthetic media vary significantly internationally:

Europe: The EU's AI Act includes requirements that AI-generated content be disclosed. Some European countries (Italy, for instance) have moved to criminalize deepfake creation in certain contexts. European right of publicity laws are generally stronger than in the US.

UK: The Online Safety Bill includes provisions for platform responsibility regarding synthetic media. The UK has also strengthened defamation law in ways that could be applied to deepfakes.

China: Has banned deepfakes related to politics or current events. Also requires disclosure of AI-generated content. Enforcement is not transparent.

Japan: Passed laws criminalizing deepfake pornography. Has relatively strong right of publicity protections.

United States: No federal deepfake law, though several states have enacted limited protections. Right of publicity is state-dependent and varies significantly.

This patchwork means that a deepfake legal in one jurisdiction might be criminal in another. It also means that creators and platforms have to navigate conflicting requirements. A platform like Tik Tok must decide whether to allow synthetic media—do they follow EU law globally, or only in the EU? Do they follow the most restrictive jurisdiction?

Most major platforms are erring on the side of restriction, but inconsistently. Which leaves the Pitt-Cruise video scenario possible: something spreads, becomes famous, and platforms only act after the fact.

What Happens Next: Immediate and Long-Term Implications

In the immediate term (next 6-12 months), expect:

- Stricter Platform Policies: Tik Tok, You Tube, and Twitter will refine policies around synthetic media and increase enforcement

- Studio Contractual Language: More explicit AI-related language in actor contracts, requiring consent for synthetic likeness use

- SAG-AFTRA Advocacy: The union will use the incident as a rallying point for broader legal protections

- New Detection Tools: More sophisticated detection and watermarking technology will be deployed

- Regulatory Proposals: Several governments and state legislatures will propose deepfake and synthetic media laws

In the long term (2-5 years), the likely outcomes include:

- Fragmented Regulatory Landscape: Different jurisdictions will have different rules; global uniformity unlikely

- Technological Standoff: Better deepfakes versus better detection in an ongoing arms race

- Industry Standards Emerge: Technology vendors, platforms, and studios will develop internal standards for synthetic media use

- Compensation Models Develop: Systems for tracking and paying for synthetic likeness use become standardized

- Public Skepticism Rises: As synthetic media becomes more common, public trust in video evidence declines, requiring new forms of content authentication

The wildcard is whether meaningful legal protections emerge before synthetic media becomes so common and normalized that regulating it becomes impossible.

Runable: Automating Response and Documentation

For professionals and organizations navigating the synthetic media landscape, automation tools can help manage the complexity. Runable offers AI-powered automation for creating comprehensive documentation, reports, and presentations that track media usage, consent records, and licensing agreements.

Specifically, Runable can help:

- Generate compliance documentation for synthetic media usage with AI-assisted templates

- Automate report creation showing which synthetic media has been deployed, where, and under what agreements

- Create presentation materials summarizing deepfake threats and protective measures for stakeholder meetings

- Build tracking spreadsheets documenting all synthetic media usage, consent, and compensation

For studios, talent agencies, and unions managing these issues, automation takes the busywork out of documentation. Runable starting at $9/month can save teams hours on documentation and reporting.

Use Case: Studios documenting synthetic media compliance and tracking AI-generated content across multiple productions

Try Runable For Free

FAQ

What is a deepfake, and how is it different from synthetic media?

A deepfake is specifically a video or audio recording that's been manipulated or artificially generated to make it appear that someone said or did something they didn't. Synthetic media is the broader category including deepfakes, but also AI-generated images, videos, and audio that didn't exist before. The Seedance 2.0 tool creates synthetic media—in this case, video that never happened featuring real people's likenesses. Not all synthetic media is deepfakes, but all deepfakes are synthetic media.

Why can't SAG-AFTRA just sue to stop this content?

Legal remedies exist but are slow, expensive, and uncertain. A lawsuit requires proving damages (did this specific deepfake cost you work?), identifying the creator (they're often anonymous), and navigating jurisdictional issues (they might be in a different country). By the time a lawsuit concludes, the video has already spread globally and been replicated thousands of times. Legal solutions address past harms but don't prevent future ones, which is why the union is pushing for proactive legal protections and platform responsibility instead.

Could Seedance 2.0 or similar tools add technical restrictions to prevent deepfakes?

Possibly, but it's complex. A tool could refuse to create synthetic video of famous people's faces, but that requires a facial recognition system that might be inaccurate, and people could just use different tools or modified versions. It could require consent verification, but how do you verify consent online? Technical restrictions help but aren't foolproof, which is why policy and enforcement matter as much as technology.

How do actors and their representatives even find out about unauthorized synthetic media made of them?

Mostly through alerts from fans or other people who see the content and report it. There's no systematic way to monitor all deepfakes or synthetic media of a specific person. Some companies offer monitoring services using AI to scan the internet, but they're expensive and not comprehensive. This is one reason why platform responsibility is important—platforms see the content first and could flag it if they had systems in place to do so.

What protections do union actors already have from the 2023 strike agreement?

The 2023 agreement requires that studios get explicit written consent before using a performer's likeness synthetically, and it mandates additional compensation if they do use it. But these protections only apply to union work with major studios. They don't protect against deepfakes made by independent creators, international content creators, or small productions. The Pitt-Cruise video wasn't made under any studio agreement, so those protections don't apply.

If I use a synthetic media generator for creative projects, what should I be aware of?

Be aware of several things: first, platform terms of service—most synthetic media tools explicitly prohibit creating deepfakes of real people without consent. Second, potential legal liability if you create synthetic media of a real person, especially for commercial purposes or defamatory content. Third, ethical considerations about consent and the person whose likeness you're using. Fourth, potential reputational risk if your use of the tool becomes public. And fifth, the evolving legal landscape—what's technically legal today might become illegal tomorrow as regulations catch up.

Can synthetic media detection tools reliably identify deepfakes?

Not always. Detection AI works best against amateur deepfakes and early-generation synthetic video, but it's significantly less reliable against high-quality, sophisticated deepfakes. As synthesis technology improves, detection becomes harder. It's an ongoing arms race—every improvement in deepfake quality requires corresponding improvements in detection, and detection is always playing catch-up. This is why some experts argue that detection alone isn't a sufficient solution and that other approaches (watermarking, provenance tracking, platform responsibility) are equally important.

The Real Takeaway: Why This Matters

The Seedance 2.0 deepfake controversy isn't just about an awkward viral video. It's a stress test for how society handles technology that outpaces law and ethics.

Actors are the frontline of this issue, but they won't be the last profession affected. Anyone whose work depends on a unique voice, appearance, or creative signature is vulnerable. The question is whether society decides to protect that with law, regulation, and technology before the problem becomes unmanageable, or whether we wait until synthetic media is so common and sophisticated that we can't reliably distinguish authentic from artificial.

SAG-AFTRA's response—forceful, immediate, and unambiguous—signals that the entertainment industry isn't waiting. They're pushing for protections now, while they still have leverage and while the technology is new enough that regulations might actually constrain it.

The next 12-24 months will determine whether that advocacy translates into real legal and technical protections, or whether it becomes one more voice in an increasingly futile argument against technology that just keeps improving.

For now, the Pitt-Cruise video remains a vivid demonstration that we're living through a transition moment. AI-generated synthetic media is real, it's convincing, and it's here to stay. The question is just whether we'll figure out how to govern it before it becomes the norm.

Key Takeaways

- SAG-AFTRA condemned the viral Seedance 2.0 deepfake, calling it 'unacceptable' because unauthorized synthetic media threatens actors' ability to earn from their likenesses

- Seedance 2.0 uses diffusion models to generate photorealistic video with preserved facial likeness, making detection difficult and creation accessible to anyone

- Current protections from the 2023 strike agreement only cover union actors working with studios—independent creators face no restrictions, creating enforcement gaps

- Economic incentive for studios to use synthetic actors is substantial: replacing a 5K synthetic version represents potential cost reduction of 98%+

- Detection technology is losing the arms race—deepfake quality improves faster than detection systems can adapt, suggesting technical solutions alone won't solve the problem

- Fragmented international regulations mean synthetic media legal in one jurisdiction may be criminal in another, complicating platform enforcement and creator compliance

- Without proactive legal protections and platform responsibility, synthetic media adoption could transform entertainment, journalism, and political discourse within 5 years

Related Articles

- AI Video Generation Without Degradation: How Error Recycling Fixes Drift [2025]

- Ring Cancels Flock Deal After Super Bowl Ad Sparks Mass Privacy Outrage [2025]

- 4chan /pol/ Board Origins: Separating Fact From Conspiracy Theory [2025]

- xAI's Mass Exodus: What Musk's Spin Can't Hide [2025]

- Meta's Facial Recognition Smart Glasses: The Privacy Reckoning [2025]

- Meta's Facial Recognition Smart Glasses: Privacy, Tech, and What's Coming [2025]

![SAG-AFTRA vs Seedance 2.0: AI-Generated Deepfakes Spark Industry Crisis [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/sag-aftra-vs-seedance-2-0-ai-generated-deepfakes-spark-indus/image-1-1771023997962.jpg)