Washington Post's Tech Retreat: Why Media Giants Are Abandoning Silicon Valley Coverage

In early 2026, the Washington Post made a quiet but seismic decision. The newsroom didn't announce it with fanfare. No press release. No grand statement about strategic repositioning. Instead, the cuts came via Zoom call, delivered by executive editor Matt Murray to staff who'd spent years building what should have been the most important tech beat in American journalism.

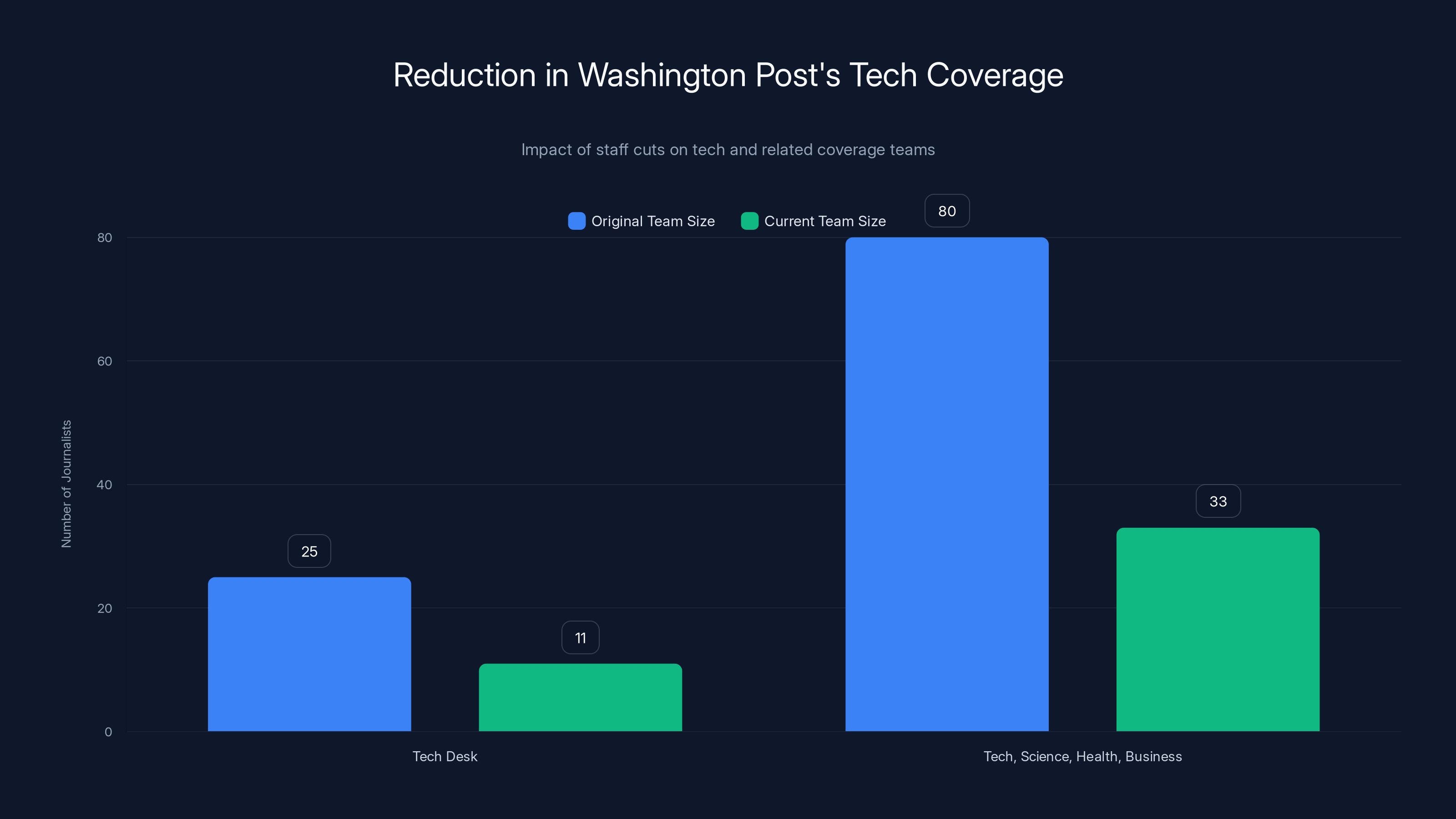

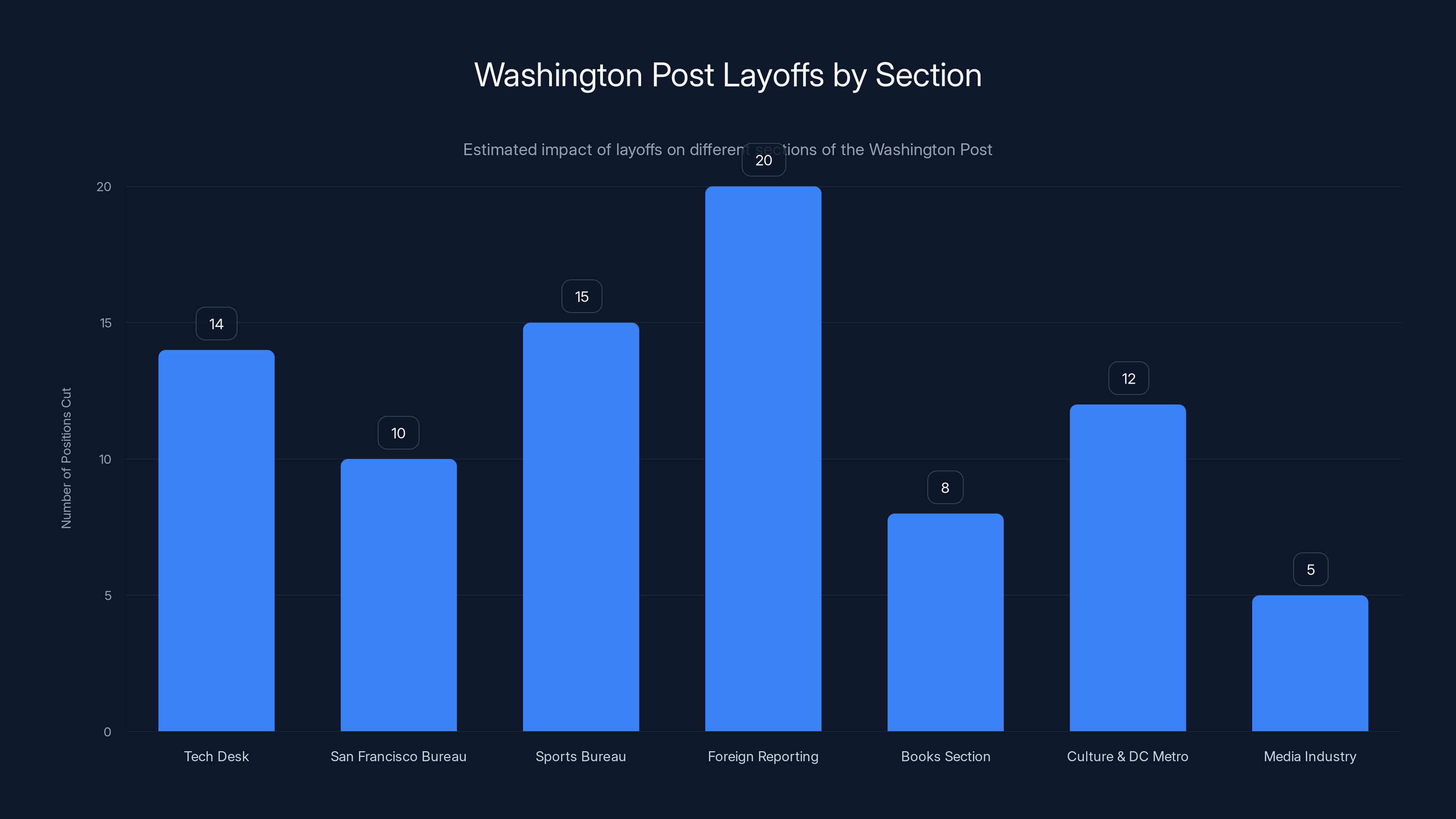

The numbers tell the story: 14 journalists gone from the tech desk. The entire San Francisco bureau gutted. Coverage of Amazon, artificial intelligence, internet culture, and major tech investigations axed. All part of a broader round that eliminated more than 300 jobs across the organization, with the tech, science, health, and business teams cut by more than half.

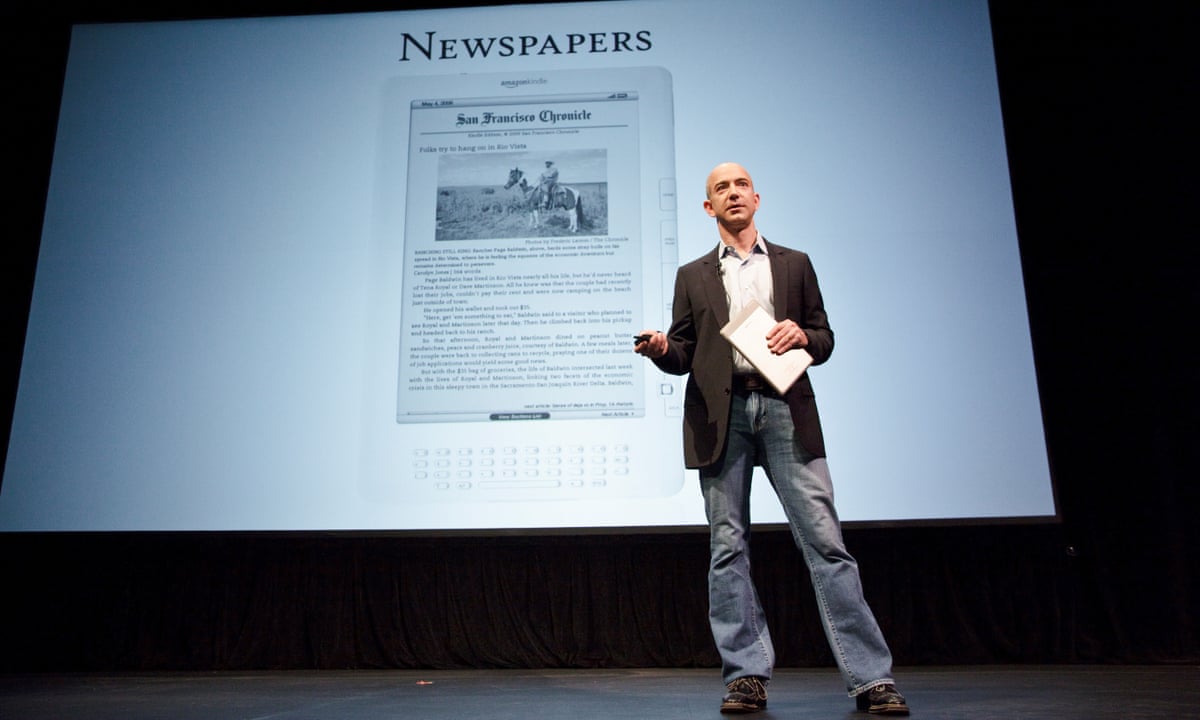

But here's what makes this cut different from the dozens of media layoffs that've happened over the past five years. The Washington Post isn't some regional newspaper struggling with print-to-digital transition. It's owned by Jeff Bezos, the third-richest person on the planet, whose wealth comes directly from the technology sector. The Post just eliminated most of its ability to cover that sector. And in doing so, it eliminated reporters covering Bezos himself, his company Amazon, his space venture Blue Origin, and the broader ecosystem that made him one of the world's most powerful figures.

This isn't a story about journalism struggling. It's a story about the concentration of power, the retreat of institutional checks on that power, and what happens when the people most directly responsible for the world's economic and geopolitical trajectory can simply choose to stop being watched.

TL; DR

- The Post eliminated 14 tech journalists from its tech desk alone, gutting coverage of AI, Amazon, and internet culture in early 2026

- San Francisco bureau is now a shell, representing a retreat from the geographic center of technological innovation and power

- Coverage vacuum creates accountability gap, with no institutional press covering tech executives who shape global economics and geopolitics

- Pattern repeats across billionaire-owned media, where ownership interests often align with reduced scrutiny of their own companies

- Google Search algorithm changes have accelerated media layoffs industry-wide, but The Post's cuts are strategically targeting areas most important to monitoring power

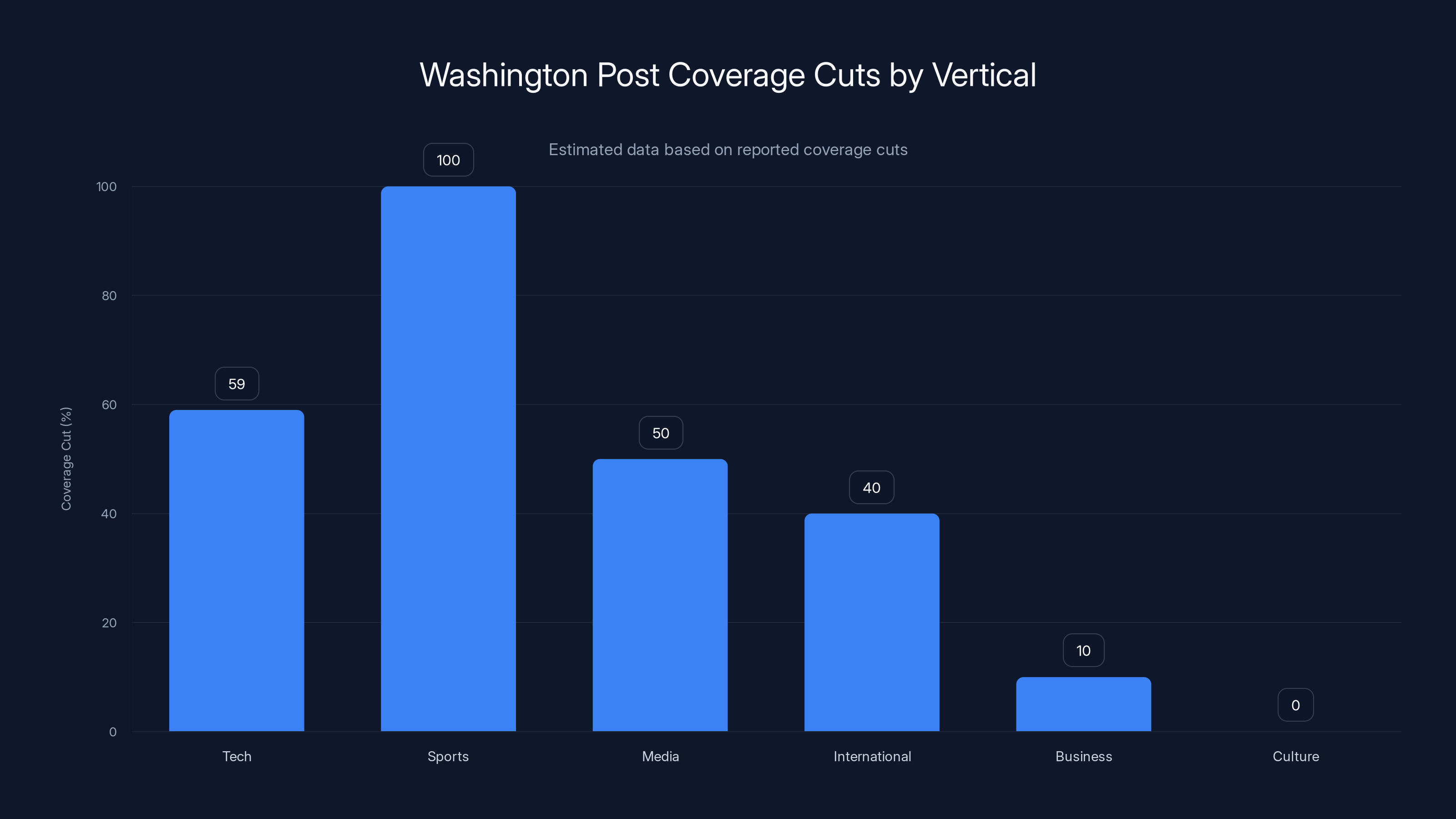

The Washington Post reduced its tech desk by 56% and its broader tech-related team by 59%, significantly impacting its tech coverage capabilities.

The Scale of the Retreat: What Actually Got Cut

When newsrooms announce layoffs, the numbers can feel abstract. The Washington Post cut from 1,000 employees to under 800 the previous spring. This time, it was another round. But the granularity matters, because the Post didn't cut evenly. It didn't trim every section by 15 percent. Instead, it surgically eliminated coverage in specific areas.

The tech desk lost 14 people. That might not sound enormous until you realize a typical tech desk at a major metropolitan newspaper has maybe 20-25 journalists. The Post's tech team was already relatively lean compared to what newsrooms might have staffed in 2010. Losing 14 meant losing roughly 56 percent of tech coverage capacity.

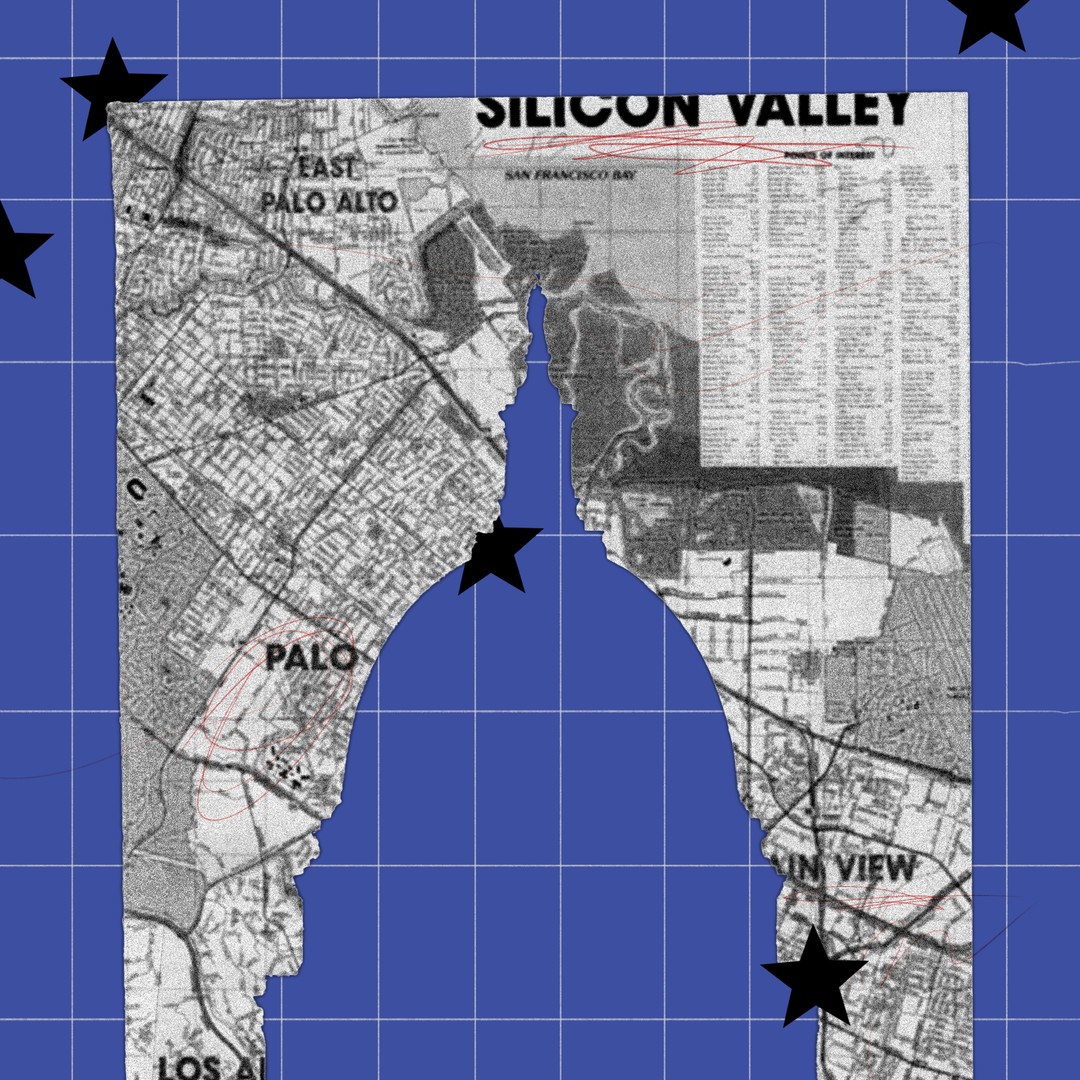

The San Francisco bureau didn't get trimmed. It got hollowed out. A full-scale news bureau, with multiple reporters covering the geographic center of Silicon Valley innovation, essentially ceased to exist as a functional reporting operation. That's not cost-cutting. That's a strategic decision to stop covering an entire region.

But the Post's cuts went beyond tech. The organization eliminated its entire sports bureau. That's surprising not because sports matters more than tech, but because it suggests the cuts weren't about efficiency or cost optimization. They were about strategic choices on what to cover. The Post also decimated its foreign reporting teams. The Middle East desk got cut. Ukraine coverage got cut. Russia coverage got cut. Iran, Turkey, and other critical geopolitical regions lost reporters and editors.

The Post closed its entire Books section. It cut coverage of culture, the DC Metro area, and race and ethnicity issues nationally. And it eliminated all reporters and editors covering media industry issues. That last one carries particular weight. The Post's own editorial board had previously raised concerns about Bezos' influence on the newsroom. By eliminating media reporters, the organization also eliminated internal capacity to scrutinize its own ownership structure.

The math is stark: the team covering tech, science, health, and business went from 80 people to 33. That's a 59 percent reduction. In an era when technology is increasingly inseparable from science, health, and business, that hollowing out affects every beat.

Why This Moment Matters: Tech's Unprecedented Power

To understand why the Washington Post's retreat from tech coverage is consequential, you need to zoom out and see the moment we're actually in. Technology isn't just important. It's foundational to every major system in society.

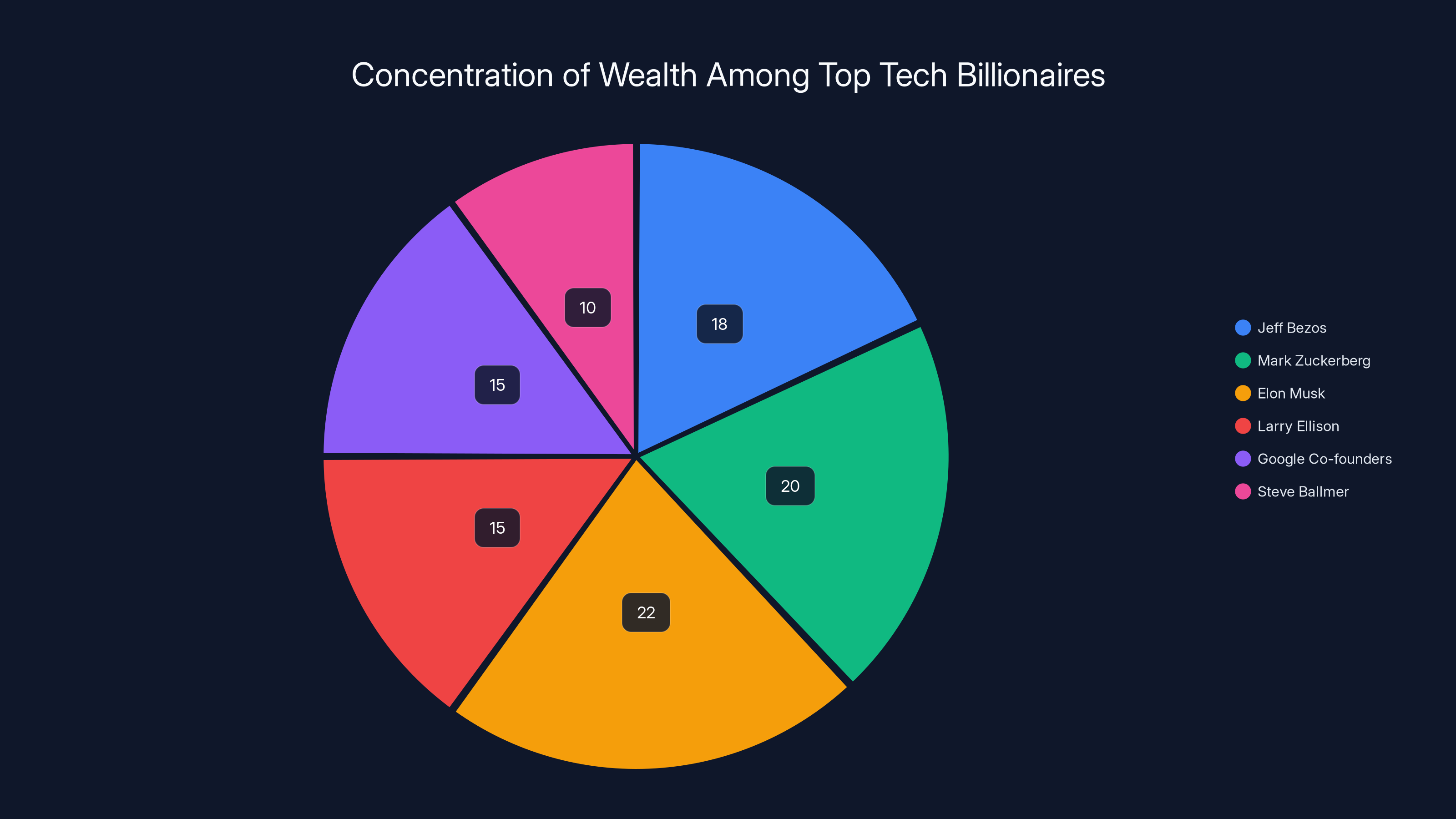

Seven of the ten richest people in the world made their fortunes directly from technology. Jeff Bezos is third, behind Mark Zuckerberg and Elon Musk. Oracle's Larry Ellison is on the list. Google's co-founders. Former Microsoft CEO Steve Ballmer. The concentration of wealth in tech is staggering, and it translates directly into political and economic influence.

But it's not just about billionaires getting richer. It's about how technology now mediates almost everything. Software runs the infrastructure that delivers energy to your home. Algorithms decide which news you see, which jobs get recommended to you, which loans you can get approved for. Machine learning is increasingly embedded in medicine, criminal justice, hiring, and hiring decisions. Artificial intelligence is shifting from a thing technologists build to a thing that affects every sector of the economy and society.

The infrastructure that makes modern commerce possible runs on technology built in Silicon Valley. That Amazon package arriving at your doorstep? The logistics are orchestrated by algorithms. The sorting facility uses robotics and machine learning. The delivery route was optimized by AI. Your ability to order it was mediated by Java Script running in your browser, sent from servers managed by cloud engineers. The whole system is technology, all the way down.

And the executives who built these systems wield influence that rivals governments. They have direct access to world leaders. Their business decisions affect employment across entire industries. Their investment choices shape which technologies get built next. When one of them decides to make a major policy shift, it can affect billions of people overnight.

Then, suddenly, one of the few institutions with the resources and mandate to scrutinize that power decides to stop paying close attention. The Washington Post, one of the few organizations with a sprawling tech team and a bureau in San Francisco, just signaled that it's stepping back from comprehensive tech coverage.

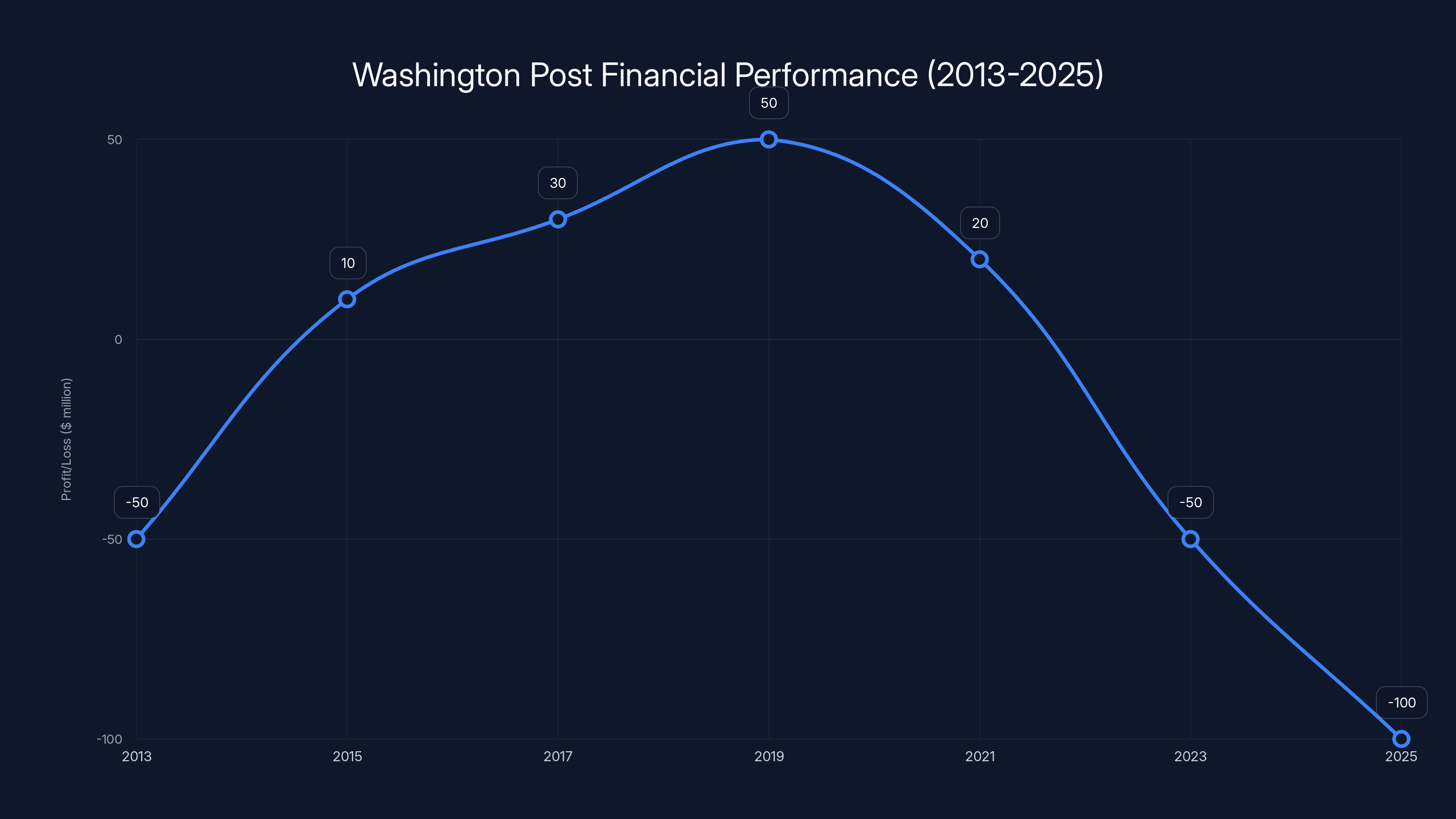

The Washington Post saw initial financial improvement post-Bezos acquisition but faced significant losses by 2025, partly due to editorial decisions. Estimated data.

The Bezos Paradox: Owner, Subject, and Backstory

Here's where the story gets complicated. The Washington Post isn't a neutral observer. It's owned by Jeff Bezos, who made his fortune from Amazon, and who controls Blue Origin, the space company. The Post is now less able to cover Amazon. Less able to investigate Blue Origin. Less able to scrutinize the broader influence of the tech industry that made Bezos wealthy.

That might be coincidence. But it's the kind of coincidence that deserves scrutiny.

Bezos bought the Washington Post in 2013 for $250 million. At the time, it was seen as a bold move by a billionaire to rescue an institution in crisis. The Post had been hollowed out by the shift from print to digital. It was losing money. Its parent company, the Graham family, was looking to sell. Bezos stepped in, and for a while, it looked like a success story. The Post hired more journalists. It expanded coverage. It won Pulitzer Prizes. It broke major stories.

But over the past few years, the narrative shifted. Bezos made editorial decisions that affected the Post's coverage. In late 2024, the Post's editorial board had drafted an endorsement of Vice President Kamala Harris for president. Bezos instructed the editorial board not to publish it. The move was widely interpreted as Bezos exerting direct control over the Post's editorial decisions based on his own business interests and political relationships.

The backlash was significant. Hundreds of thousands of subscribers canceled their subscriptions to the Post. Internal morale plummeted. By 2025, the Post was reporting $100 million in losses, in part attributed to the subscription cancellations stemming from that editorial decision.

So when the Post now announces massive cuts to its tech coverage, the narrative is murky. Is the Post cutting tech coverage because tech coverage is expensive and the organization is losing money? Or is it cutting tech coverage because covering tech means covering Amazon, covering AI, covering the executives who are increasingly intertwined with political power?

Executive Editor Matt Murray framed the cuts as a "reboot" aimed at reaching readers and achieving profitability. He told staff that "today is about positioning ourselves to become more essential to people's lives in what is becoming a more crowded, competitive, and complicated media landscape." It's a reasonable-sounding statement. News organizations do need to be sustainable. They do need to reach readers.

But the specific cuts matter. If the Post was simply trying to be more essential to readers' lives, why eliminate all sports coverage but also eliminate Ukraine and Russia coverage? Why cut the media desk but keep business coverage? The pattern suggests something more targeted than simple cost optimization.

A Pattern Emerges: Tech Billionaires and Media Ownership

The Washington Post's situation isn't isolated. It's part of a broader trend that's been building for 15 years.

In 2013, around the same time Bezos bought the Post, Laurene Powell Jobs purchased the Atlantic. Marc Benioff, founder of Salesforce, bought Time Inc. Patrick Soon-Shiong, a pharmaceutical executive with significant tech investments, acquired the Los Angeles Times. The pattern repeated: wealthy individuals, often with deep ties to technology and capitalism, began acquiring struggling media organizations.

The pitch to each was the same. These institutions need investment. They need someone with resources to rebuild them. A tech-savvy billionaire can modernize them, understand digital, and help them succeed. For some of these acquisitions, it worked out. For others, the influence of ownership became clear pretty quickly.

Patrick Soon-Shiong, who owns the Los Angeles Times, made editorial decisions that affected coverage of his own companies and interests. He also blocked his paper's endorsement of Kamala Harris, similar to Bezos. Marc Benioff has generally maintained more distance from Salesforce coverage at Time Inc., though he's also known to be involved in strategic decisions. Laurene Powell Jobs has focused the Atlantic on particular topic areas and made it clear which stories she considers important.

The through-line is this: when billionaires own media organizations, their business interests eventually influence coverage. It doesn't always happen through explicit orders. Sometimes it happens through hiring decisions. Through which beats get funded. Through which stories get promoted. Through which regions get bureaus. Through which journalists get retained when cuts come.

The Washington Post's tech retreat fits this pattern perfectly. It's the most powerful person in tech media deciding that comprehensive tech coverage is less important than other priorities. And it happens at a moment when tech executives are wielding more influence than ever.

The Timing is Terrible: Why Now Matters

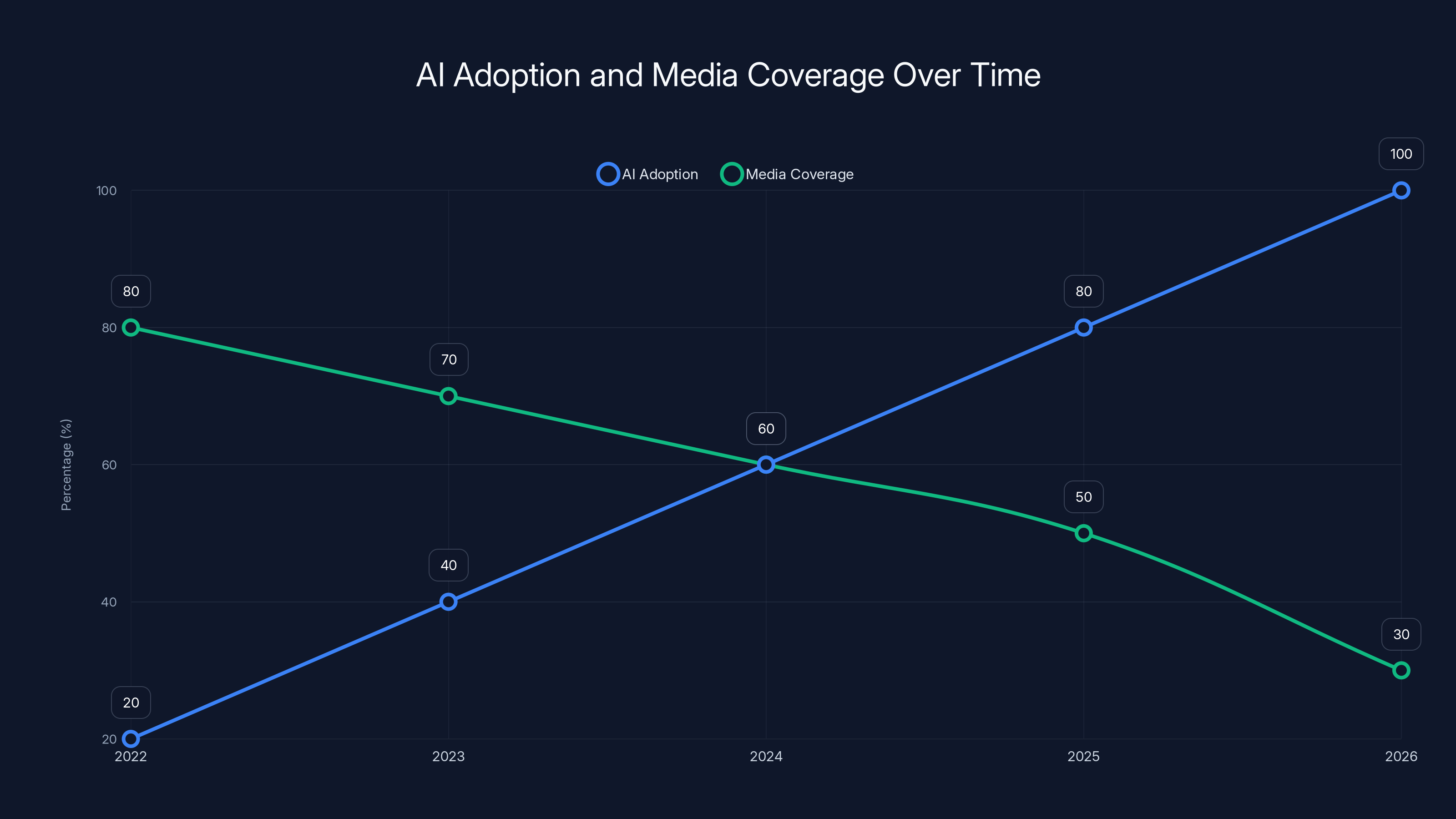

There's another layer to this story that makes the timing particularly damaging. The Washington Post is retreating from tech coverage at precisely the moment when tech coverage is most important.

Artificial intelligence went mainstream in late 2022 with Chat GPT. The technology has been accelerating ever since. In early 2026, when the Post was making these cuts, AI systems had moved from a novelty into critical infrastructure. Companies were deploying AI in hiring, healthcare, criminal justice, and financial services. Governments were scrambling to regulate AI. The technology was moving so fast that understanding it required sustained reporting, investigation, and analysis.

That's exactly the kind of coverage the Post's tech team was built for. Instead, the organization just eliminated most of its capacity to do it.

At the same time, Amazon's influence was expanding. The company had moved from e-commerce into cloud computing, groceries, healthcare, space exploration, and dozens of other sectors. Covering Amazon properly requires multiple reporters with deep expertise in different domains. The Post just eliminated that capacity.

Blue Origin, Bezos' space company, was ramping up operations. The Federal Aviation Administration was giving Blue Origin preferential treatment in licensing decisions, a story that needed investigation. The Post still has some capability to cover it, but not with the depth and resources it had before the cuts.

And more broadly, the concentration of power in tech was becoming more visible. The tech industry was increasingly shaping election outcomes, policy, and society. Investors were pouring trillions into AI infrastructure. Startups were raising record amounts of capital. The moment demanded comprehensive, skeptical, investigative coverage.

Instead, the Washington Post stepped back.

There's a term for what's happening here: "regulatory capture," though it usually applies to government agencies. When an agency that's supposed to regulate an industry becomes too close to that industry, it stops regulating effectively. Something similar can happen with media. When a news organization becomes too financially tied to a person or industry it covers, it loses the independence to cover that person or industry critically.

This chart illustrates the estimated distribution of wealth among top tech billionaires, highlighting the significant concentration of economic power within this group. Estimated data.

The Broader Media Crisis: It's Not Just the Post

Before we blame Bezos entirely, we need to acknowledge that the Washington Post's problems aren't unique. The entire media industry is in crisis. The business model is broken. Publishers are losing money. Newsrooms are shrinking everywhere.

A lot of that has to do with Google. The search giant has systematically redirected traffic away from news organizations and toward its own properties. When you search for news, Google increasingly shows you AI-generated summaries instead of linking to articles. When you search for local news, Google shows you its own local results. When you click a news link from Google Search, you're often sent to an AMP page, which cuts news organizations' ad revenue.

The result is that traffic to news websites has declined sharply. The Washington Post's daily visits dropped from 22.5 million in January 2021 to around 3 million by mid-2024. That's a 87 percent decline in a span of less than four years.

With less traffic comes less ad revenue. With less ad revenue comes pressure to cut costs. With pressure to cut costs comes layoffs. The math is relentless.

So in some ways, the Post's situation is just the inevitable result of structural problems in media economics. The industry is unsustainable at current traffic levels. Every major publication is cutting. Every newsroom is shrinking. The Post is just bigger and more visible than most.

But that context doesn't excuse the specific choices the Post made. When you have to cut, you can cut differently. You can trim every beat by 15 percent. Or you can make strategic decisions about which beats matter most. The Post chose to strategically eliminate coverage of the person who owns it and the industry that made him wealthy.

That's a choice. It's not inevitable. And it has consequences.

What Disappears When Coverage Disappears

Now let's think about what actually gets lost when a major news organization stops covering tech.

In the old days, there were dozens of newspapers with sprawling tech coverage. The New York Times has a good tech section. The Wall Street Journal covers business including tech. But the Washington Post, at its peak, had something special: a dedicated team of reporters and editors whose entire job was understanding tech, covering tech, and investigating tech.

That's resource-intensive. You need people who understand AI, blockchain, cryptocurrency, software engineering, venture capital, startup culture, and more. You need people with enough tenure to develop sources in the industry. You need editors who understand the space well enough to know which stories matter. You need the institutional commitment to do long-term investigations that might not pay off for months.

When that team disappears, a lot disappears with it. Coverage of emerging technologies that might affect society. Investigations into startup fraud or abuse. Stories about how AI is being deployed in healthcare or criminal justice. Coverage of privacy violations. Reporting on monopolistic behavior by tech giants. Stories about the influence of tech executives on politics and policy.

Some of those stories will still get covered. The Times will do some of them. The Journal will do others. But no single outlet will have the bandwidth or focus to do comprehensive tech coverage anymore. And that means some stories won't get covered at all. Some abuses won't get investigated. Some connections between tech executives and policy won't be scrutinized.

There's also a subtle effect: when coverage disappears, it sends a signal. It tells tech executives that they're less likely to be investigated. It tells sources inside tech companies that there's less institutional capacity to protect their anonymity. It tells investors that tech is less scrutinized territory. And it tells the public that tech is less important to understand.

All of those signals are dangerous.

Executive Editors and Accountability: Murray's Statement

Matt Murray, the Post's executive editor, faced significant blowback for the cuts. When journalists and media critics questioned why the Post was eliminating tech coverage, he had to explain himself.

His argument was essentially that the Post needed to become more focused. Fewer beats, deeper coverage in the areas that remain. More essential to readers' lives. A "reboot" rather than a retreat.

It's a defensible argument in theory. Every organization has to make choices about what to cover. You can't cover everything. At some point, you have to prioritize. If the Post is losing $100 million a year, something has to give.

But the specifics matter. Murray's argument would be more credible if the Post had cut, say, 15 percent from every beat. Instead, it cut 59 percent from one vertical (tech, science, health, business) while preserving other areas. It eliminated the entire sports bureau but kept business coverage. It cut the media desk but kept culture. It cut Ukraine and Russia but kept some international coverage.

Those choices reveal priorities. And the pattern suggests that the priority was to reduce scrutiny of technology, tech executives, and tech companies.

Murray has also, to his credit, acknowledged that the cuts were painful and that some good journalists lost their jobs. But acknowledgment isn't the same as explanation. The Post still hasn't really explained why tech got hit harder than other beats. It still hasn't addressed the elephant in the room: that the Post's ownership structure created a direct conflict of interest.

That conflict of interest isn't necessarily determinative. Bezos could own the Post and maintain strict editorial independence. But the pattern of decisions—blocking the Harris endorsement, eliminating tech coverage, cutting the media desk—suggests that independence is eroding.

The Washington Post's layoffs were strategic, with significant cuts in tech, sports, and foreign reporting. Estimated data based on narrative.

The San Francisco Bureau: A Symbol of Retreat

The San Francisco bureau deserves special mention because it's so symbolically important.

For decades, major news organizations had multiple reporters in San Francisco and the Bay Area. The Bureau was where you covered the companies that mattered. Apple, Google, Facebook, Tesla, all headquartered in the region. Venture capital funds pouring billions into the next wave of startups. Universities like Stanford and Berkeley producing the researchers that would power the next decade of innovation.

The San Francisco bureau was expensive. Salaries in the Bay Area are high. Rent is astronomical. But it was also essential. You couldn't cover Silicon Valley properly from New York. You needed people on the ground, with relationships, understanding the ecosystem.

The Washington Post's San Francisco bureau, at its peak, had a handful of reporters dedicated to covering the region. Now it's a shell. One or two reporters, maybe, doing some coverage. But not the deep, systematic coverage the region requires.

That's not a small retreat. That's a strategic decision to stop monitoring the geographic center of technological innovation and power.

The argument is probably that San Francisco is a wealthy, coastal, educated region, and maybe less relevant to the Post's core readers. Maybe readers in the Midwest care more about business news than about what's happening in Silicon Valley. Maybe the Post can cover tech from New York without losing much.

But that's where the argument breaks down. You can't cover tech accurately without understanding Silicon Valley. The ecosystem, the culture, the relationships between executives and investors and founders, the pace of change—all of that is rooted in place. You can report on it from elsewhere, but you understand it better when you're there.

More importantly, you're more likely to spot stories when you're embedded in a community. You develop sources. You understand which executives are problematic. You know which companies are struggling or succeeding. You pick up rumors that turn into investigations. That embedded knowledge is hard to replicate remotely.

So the Post's decision to gut its San Francisco bureau isn't just about cost. It's a decision to monitor that region less closely.

The Industry Response: How Other Outlets are Reacting

The Washington Post's tech retreat has sparked significant discussion in media circles. Other news organizations are watching carefully to see what the decision means.

Some outlets have doubled down on tech coverage. The New York Times, for instance, has continued to invest in its tech team. The Journal has expanded coverage of AI and startups. Those organizations seem to recognize that tech coverage is important and that there's actually reader demand for it.

But other outlets are taking the opposite approach. If the Post is stepping back, maybe tech coverage isn't worth the investment. Maybe resources are better allocated elsewhere. That logic is understandable but also dangerous.

What's happening is a kind of media market failure. Individual outlets make rational decisions based on cost and revenue. But those decisions add up to a collective collapse of coverage. If everyone steps back from tech reporting, nobody will cover tech. And the people who benefit most from that lack of coverage are the tech executives themselves.

There's also a generational issue. Tech reporting requires specialized knowledge. It requires journalists who understand how APIs work, who can read code, who understand venture capital, who know the difference between different types of machine learning. Those journalists exist, but they're concentrated in a few organizations. When those organizations cut their tech teams, the specialized knowledge disperses. Future journalists won't have those mentors. The field loses expertise.

The broader media industry is also grappling with the question of whether tech coverage is economically viable. Readers seem to be interested in it. The Post's tech articles were often highly trafficked. But traffic doesn't always convert to subscriptions or ad revenue. So outlets have to make bets about what will ultimately generate revenue. If tech coverage generates traffic but not money, it's a bad investment.

That's a real problem. It means that the most important stories might not get covered because they're not profitable to cover. The market fails to provide information about the most powerful people and institutions.

What Should Have Happened Instead

Let's imagine an alternate scenario. What if the Washington Post had cut differently?

The Post needed to reduce costs. That's a real constraint. But it could have made different choices. It could have cut 20 percent from every beat, rather than 59 percent from tech and other specific areas. It could have preserved the San Francisco bureau even if smaller. It could have kept the media desk so that media ownership issues could still be covered internally.

Or it could have made the hard choice to reduce the breadth of coverage while deepening coverage in priority areas. If the Post wanted to be more essential to readers, it could have focused on, say, national politics, the economy, and technology—the three areas most directly affecting people's lives. It could have cut everything else but kept those areas strong.

Instead, it made choices that reduced accountability and scrutiny of the people who own it and the industry that made those people wealthy. That's a choice, and it's a bad one.

The Post also could have been more transparent about the ownership conflict. It could have said, "We're cutting tech coverage. Here's why. And here's how we're managing the conflict of interest that arises because our owner is a tech executive." Transparency about the problem is better than denying it exists.

There's also the question of what the Post could have done differently with Bezos from the start. A more arms-length relationship. Formal editorial independence agreements. Rules about when Bezos can influence editorial decisions. Regular audits of coverage to detect bias. Those structures exist in some organizations. The Post could have implemented them.

But instead, the Post seems to have done the opposite. It's moved closer to its owner's interests, not farther. And it's cut the coverage area most relevant to monitoring that owner's power.

Estimated data shows AI adoption increasing rapidly from 2022 to 2026, while media coverage by major outlets like the Washington Post decreases, highlighting a gap in critical reporting.

The Ripple Effects: What Happens Next

Now let's think about what happens over the next few years as the ripple effects of the Post's retreat spread.

First, there will probably be less coverage of Amazon. The company is massive and increasingly important to infrastructure and society. But the Post is less equipped to cover it. Other outlets will cover it, but with less depth. Some stories won't get covered.

Second, AI coverage will suffer. There are other outlets covering AI, but the Post had particular expertise and focus. With that reduced, the overall information landscape is poorer. That matters because AI is the most important technology being developed right now.

Third, the retreat sends a signal to other billionaire-owned media organizations that they can reduce coverage of themselves and their industries. If it works for the Post, why not try it at the Times, or the Journal, or other major outlets? The behavior becomes normalized.

Fourth, sources inside tech companies will be less likely to talk to journalists because the journalistic infrastructure to protect them is smaller. If there are fewer reporters covering tech, there are fewer places to go with information. That makes it harder for whistleblowers and insiders to get stories out.

Fifth, the tech industry becomes less scrutinized overall. Not completely—there are still other outlets and independent journalists doing tech coverage. But the institutional presence is weaker. And institutional presence matters. A major newspaper's investigation is more likely to force action than an independent journalist's article.

Long-term, the lack of tech coverage could affect policy. Policymakers rely on journalism to understand issues. If they can't read in-depth articles about tech policy, they make decisions based on less complete information. Tech executives have more opportunity to shape those policies without scrutiny.

Comparing Media Ownership Models: Could the Post Have Done Better?

There are different models for how media organizations can operate, and some handle ownership conflicts better than others.

One model is public ownership, like the BBC. The BBC is publicly funded and publicly accountable. It's supposed to serve the public interest, not a private owner's interest. The downside is that governments can try to influence coverage. The upside is that there's no individual billionaire directing editorial decisions.

Another model is nonprofit ownership, like Pro Publica or NPR. These organizations are owned by nonprofits with specific missions around public-interest journalism. The owner doesn't have private financial interests to protect. Pro Publica, for instance, is owned by a nonprofit dedicated to investigative journalism. That aligns incentives properly.

A third model is employee ownership. Some news organizations are owned by the journalists who work there, like the Guardian or some smaller outlets. That aligns incentives too. The owners' success depends on good journalism, which is also good for readers.

Then there's the model the Post uses: individual owner with broad discretion. Bezos owns the Post and can make pretty much any decision he wants. He can direct coverage. He can force editorial decisions. He can cut beats. The only constraint is that egregious decisions might harm the Post's reputation and lose readers.

That model has some advantages. It can attract investment. It can move quickly. But it also creates direct conflicts of interest when the owner has business interests affected by the outlet's coverage.

The Post could have adopted a different model. Bezos could have set up the Post as an independent nonprofit. He could have created a trust with specific rules about editorial independence. He could have hired an editor who reports to a board rather than directly to him. Those structures exist. They're not common, but they're possible.

Instead, the Post operates as a kind of personal venture. Bezos has a lot of control. And when he exerts that control, the outcome affects what gets covered and what doesn't.

The Economics of Journalism: Why Outlets Cut

To really understand what's happening at the Post, you need to understand the economics of modern journalism.

Print newspapers made money through subscriptions and ads. Readers paid for a physical newspaper, and advertisers paid to reach readers. The business model worked for a century.

Digital journalism broke that model. Readers didn't want to pay for online news. And advertisers realized they could reach people more cheaply through search engines and social media. Ad rates collapsed.

So news outlets had to find new business models. Some went paywall. Some went nonprofit. Some focused on niche audiences and premium pricing. The Post tried a combination: the Post tried to build subscriptions while also relying on ad revenue.

Subscriptions have grown over the years, but they're not enough to replace the print advertising revenue that was lost. The Post probably has millions of subscribers, but that still doesn't generate enough money to support a newsroom the size of what was there in the 1990s.

At the same time, costs have risen in some areas. It's more expensive to maintain digital infrastructure. It's more expensive to pay competitive salaries to attract good journalists in expensive cities like Washington D. C. and San Francisco.

So news outlets are in a squeeze. Revenues are lower. Costs are not proportionally lower. The solution is to cut newsroom size. And when you cut, you try to cut in ways that minimize damage to revenue. You cut beats that don't generate subscriptions as much. You cut bureaus in expensive cities.

Tech coverage, interestingly, probably generates a decent amount of traffic and engagement. Readers are interested in tech. But does traffic convert to subscriptions? That's a different question. The answer isn't clear.

So a rational cost-cutting editor might look at tech coverage and think: "We get good traffic on these stories, but is it converting to subscriptions? Or is the traffic coming from search engines and social media, where we don't get credit for the traffic or convert it to subscriptions?" If the second answer is yes, then tech coverage looks like a cost center rather than a revenue driver.

That's probably what happened at the Post. Tech coverage was expensive and didn't seem to drive enough subscription revenue. So it got cut.

But that misses the larger point. News organizations shouldn't be optimizing purely for subscription revenue. They should be optimizing for important coverage. Some important stories won't drive subscriptions. Some niche coverage is important even if it doesn't reach a mass audience. The purpose of journalism isn't just to be profitable. It's to serve the public interest.

When outlets optimize purely for revenue, they cut important coverage. And society suffers.

The Washington Post made significant cuts to its tech coverage (59%) and eliminated the sports bureau entirely, while maintaining business and culture coverage. Estimated data based on narrative.

Conflict of Interest in Media Ownership

Let's be explicit about what the conflict of interest is here.

Jeff Bezos owns Amazon, Blue Origin, and the Washington Post. Amazon is subject to regulation and criticism. Blue Origin is subject to regulatory approval from the FAA. Both companies benefit from favorable coverage and lack of critical scrutiny. Bezos also has political interests. He's friends with political figures. He makes donations and contributions. His companies are affected by policy.

Now Bezos owns a major news organization that could scrutinize all of those interests. That's a conflict. It's not automatic that Bezos will use the Post to avoid scrutiny of his companies. It's theoretically possible for a billionaire owner to maintain strict editorial independence.

But the incentives are misaligned. Every journalistic norm tells you to avoid conflicts of interest. If you're covering a company that you own, you should recuse yourself. If you're the owner of the publication, you should have strong rules in place to protect editorial independence.

The Post seems to have weak protections. When Bezos wanted to block the Harris endorsement, he apparently could just do it. That suggests that editorial independence isn't strong. And when editorial independence is weak, it's likely to be used to suppress coverage of the owner's interests.

The Post's decision to cut tech coverage hasn't been explicitly justified as being related to Bezos' interests. It's been justified as a cost-cutting measure. But the outcome is the same: less scrutiny of Amazon, less scrutiny of tech executives, less scrutiny of the industry that made Bezos wealthy.

So even if Bezos didn't explicitly order the cuts for that reason, the outcome aligns with his interests. And that's the problem with having a billionaire owner a major news organization.

The Bigger Picture: What We're Losing

Take a step back and look at the broader trend.

Fifteen years ago, there were dozens of newspapers with strong tech coverage. The Post had a big tech team. The Times had one. The Journal. Papers in San Francisco, Los Angeles, Chicago, Boston. Local papers had tech reporters. Regional publications covered tech.

Now, that network has collapsed. Most local papers have cut or eliminated tech coverage entirely. Regional papers have consolidated and cut. Most of the major metros have smaller tech teams than they used to.

At the same time, technology has become more important. AI is advancing rapidly. Tech companies are more powerful than ever. Tech executives are more influential. The moment when tech coverage should be strongest is when the institutional capacity to do it is at its weakest.

This creates an information vacuum. There's still tech coverage. The Times has a good tech section. Independent tech journalists exist. Newsletters covering tech have grown. But there's no single institution with the resources and mandate to comprehensively cover the entire tech industry.

That matters because comprehensive coverage requires resources that individual journalists don't have. To really cover Amazon requires investigation of logistics, cloud computing, retail, healthcare, space, entertainment, and more. That requires multiple reporters with deep expertise. A single journalist can't do it.

To cover tech's influence on policy requires reporters embedded in DC covering policy, and reporters in the field covering tech. That requires an organization that operates across multiple cities. Very few organizations can do that now.

The result is that large parts of tech don't get covered. Small scandals at big companies might get covered. Startup failures get covered if they're dramatic enough. But systematic problems, long-term investigations, and coverage of the connections between tech and power—that's getting rarer.

And the people most interested in that lack of coverage are the tech executives themselves. A world where tech is less scrutinized is a world where they have more freedom to operate.

What Should Be Done: Potential Solutions

If you believe (as I do) that the retreat from tech coverage is bad for society, what should be done?

First, pressure on billionaire media owners to strengthen editorial independence. The Post could commit to specific structures protecting editorial independence. It could hire an ombudsman who reports to a board rather than to Bezos. It could establish rules about when Bezos can influence editorial decisions. It could publish annual reviews of coverage to detect bias.

Second, investment in nonprofit tech journalism. Pro Publica, the Marshall Project, and other nonprofits do good work. More nonprofits could be founded specifically to cover tech. Funders could support this work. It would be more expensive than commercial media, but it would produce important coverage.

Third, support for independent journalists and newsletters covering tech. As traditional outlets cut, independent voices have more room. Readers can support these journalists directly through subscriptions or support services.

Fourth, pressure on Google to stop destroying journalism's business model. Google's decision to show AI summaries instead of linking to articles is devastating news organizations. Pressure and potentially regulation could force Google to send more traffic and revenue to news organizations.

Fifth, regulatory pressure on tech companies to disclose information about themselves. If companies are transparent about their operations, journalists can write about that information even if there's less investigative reporting. This doesn't replace good journalism, but it helps.

Sixth, funding models that work better for journalism. Some news organizations have found that reader revenue works better than advertising. Others have found that live events and events can supplement journalism revenue. Experimentation with new business models could find approaches that work.

Seventh, and most important, cultural change that values journalism even when it doesn't make immediate profit. Journalism is a public good, like education or public health. It should be funded partly from public sources, not purely based on commercial viability.

None of these are silver bullets. But together, they could start to rebuild the journalistic infrastructure we've lost.

The Dark Timeline: What If Nothing Changes

Let's imagine what happens if current trends continue and nothing changes.

Over the next five years, more outlets cut tech coverage. The Times and Journal maintain some coverage because they're very large and profitable. But mid-size outlets cut. Local outlets continue to disappear. The network of tech journalism continues to weaken.

Whistleblowers inside tech companies have fewer places to go with information. Some stories don't get told. Some abuses don't get exposed. Tech executives become increasingly confident they won't be held accountable for anything.

Policy gets made without good information. Legislators make rules based on PR from tech companies rather than based on solid journalism. Regulation becomes less effective because it's less informed.

Tech companies become more concentrated. Without scrutiny, the big players can acquire smaller competitors. Market concentration increases. Innovation slows because there's less competition.

Meanwhile, AI continues to advance rapidly, deployed in healthcare, criminal justice, hiring, and other high-stakes domains. These deployments have bugs, biases, and problems. Fewer journalists are around to investigate and report on them. The problems go undetected longer.

Tech billionaires become effectively unaccountable. They're not subject to the scrutiny that comes from investigative journalism. They can make political donations and influence policy without public understanding of what they're doing.

Long-term, that's corrosive to democracy and society. Accountability requires information. Without information, there's no accountability.

The Hopeful Timeline: What Could Happen

Alternatively, imagine that things go differently.

The Washington Post recognizes that cutting tech coverage was a mistake. It rebuilds its tech team. It recommits to covering the tech industry comprehensively. Other outlets see that tech coverage is important and double down on it too.

Nonprofit tech journalism organizations are founded and funded well. They do deep, long-term investigations. They become trusted sources for information about tech.

Google changes its policies and starts driving more traffic to news organizations. The business model for journalism improves. Outlets can afford larger newsrooms.

Tech executives, knowing they're being watched closely, become more careful about misconduct and misconduct. They disclose more information voluntarily. They lobby more transparently because they know investigative journalists will report on it.

Tech companies make better decisions because they know their decisions will be scrutinized. They're less likely to cut corners on safety or privacy. They're more careful about bias in AI systems. They pay more attention to environmental impacts.

Policy becomes better informed. Legislators understand the tech industry better and make rules that are more effective. Regulation is less vulnerable to lobbying because good journalism makes lobbying more transparent.

Tech innovation continues, but with better guardrails. AI is deployed more carefully. New technologies are scrutinized before they cause major problems.

That's the hopeful timeline. It requires commitment to journalism and willingness to fund it. It requires tech outlets to resist pressure to cut in strategic ways. It requires readers to value good journalism even if it doesn't directly entertain them.

But it's possible.

FAQ

Why did the Washington Post cut so much tech coverage?

The Post cited financial losses and a need to "reposition" itself toward profitability. The organization lost $100 million in 2024, in part due to subscription cancellations after blocking an editorial endorsement. However, the specific targeting of tech coverage—rather than cutting all beats equally—suggests additional factors, including the ownership conflict of interest between Bezos' control of Amazon and Blue Origin and his ownership of the Post.

How much tech coverage did the Post eliminate?

The Post cut 14 journalists from its tech desk specifically, reducing the team by approximately 56 percent. More broadly, the team covering tech, science, health, and business was cut from 80 to 33 people, a reduction of 59 percent. The San Francisco bureau was essentially gutted, losing the organization's geographic footprint in Silicon Valley.

Does Bezos' ownership influence the Post's coverage decisions?

That's impossible to prove definitively, but the pattern raises serious concerns. Bezos blocked the Post from endorsing Kamala Harris, demonstrating willingness to override editorial decisions for political reasons. The subsequent decision to cut tech coverage—the beat most relevant to covering Amazon, Blue Origin, and tech executives—occurred after this incident. While causation isn't proven, the pattern suggests that editorial independence is weaker than it should be.

Are other news organizations also cutting tech coverage?

Cutting is happening across the media industry due to financial pressures, but the pattern varies. Some major outlets like the New York Times and Wall Street Journal have maintained or grown tech coverage because they're large and profitable enough to sustain it. Smaller and mid-size outlets have cut more severely. Regional papers and local outlets have virtually disappeared as sources of tech reporting.

What happens when tech coverage disappears?

When comprehensive tech coverage disappears, accountability decreases. Some important stories don't get investigated. Tech executives have less scrutiny for misconduct, privacy violations, and anti-competitive behavior. Sources inside companies are less likely to come forward because there are fewer journalists to protect them. Policy becomes less informed because legislators don't have good information about tech industry practices.

Could the Post have maintained tech coverage while still cutting costs?

Absolutely. The Post could have reduced all beats proportionally by 15-20 percent rather than targeting specific areas for deeper cuts. It could have preserved the San Francisco bureau even if smaller. It could have kept one or two tech reporters instead of cutting the team down to almost nothing. The specific targeting of tech suggests strategic choice rather than necessity.

What's the difference between journalism at the Post and other outlets covering tech?

The Post, at its peak, had specific advantages: resources to fund deep investigations, reporters with years of tenure and strong sources, the institutional credibility of a major newspaper, and specific expertise across different domains of tech (AI, startups, platforms, infrastructure). No single journalist or small outlet has all those advantages. When that institutional capacity disappears, the overall quality of tech coverage declines.

How does this compare to other billionaire-owned media outlets?

Bezos isn't the only billionaire who owns media. Marc Benioff owns Time Inc., Laurene Powell Jobs owns the Atlantic, and Patrick Soon-Shiong owns the Los Angeles Times. Each of these owners has influenced coverage in ways that align with their interests. The difference with Bezos is that Amazon is the single most important tech company to understand, and the Post's tech team was specifically positioned to cover it comprehensively.

What would better editorial independence look like at the Post?

Better structures would include: an editor reporting to a board rather than directly to Bezos, specific rules about which decisions Bezos can influence and which are purely editorial, annual reviews of coverage to detect bias, recusal of the owner from decisions affecting coverage of his own companies, and transparency about ownership and potential conflicts of interest.

Is there any hope for rebuilding tech journalism?

Yes, but it requires commitment. Nonprofit organizations could be funded to do tech journalism. Individual journalists could be supported directly by readers through subscriptions. Outlets like the Times and Journal could be pressured to maintain tech coverage. Google could be pressured to stop destroying news organizations' business models. And cultural attitudes toward journalism could shift to value it as a public good worth funding, even if it's not profitable.

The Bottom Line

The Washington Post's retreat from tech coverage is a symptom of larger problems in media economics and in the concentration of power in tech. But it's also a choice. The Post could have cut differently. It could have maintained more tech coverage. It could have kept its San Francisco bureau. It could have preserved the ability to cover the industry and the executives who shape society.

Instead, it chose to step back. And that choice has consequences. Fewer journalists are watching the people who wield the most influence over the world's economy and geopolitics. That's dangerous. Not because tech executives are necessarily evil, but because accountability requires scrutiny. Without scrutiny, there's no accountability.

The retreat might help the Post's bottom line in the short term. Fewer reporters means lower costs. But long-term, it's a bet that tech coverage doesn't matter. That artificial intelligence and Amazon and the broader tech industry aren't important enough to devote resources to. That readers don't care about these topics.

I'm not sure that bet will pay off. I think readers do care about tech. I think tech is important. And I think the world needs more institutional journalism covering tech, not less.

The Post had a chance to be the definitive source for tech coverage. Instead, it's retreating just as tech becomes more important. That's tragic, not just for journalism, but for society.

Key Takeaways

- The Washington Post eliminated 14 tech journalists and cut its entire San Francisco bureau, reducing tech-science-health-business coverage by 59 percent

- The Post's retreat from tech coverage happens at a moment when AI, Amazon, and tech executives wield unprecedented influence over society and economy

- Bezos' ownership of both the Post and Amazon creates an unmanaged conflict of interest that appears to influence editorial decisions

- The Post's traffic declined 87 percent from 2021 to 2024, forcing cost-cutting, but the organization chose to cut tech coverage strategically rather than proportionally

- Institutional tech journalism is collapsing industry-wide, creating accountability gaps for the most powerful executives and companies shaping society

Related Articles

- FBI Device Seizure From Washington Post Reporter: Journalist Rights and First Amendment [2025]

- FBI Seizes Reporter's Devices: Press Freedom Under Siege [2025]

- Apple's Lockdown Mode Defeats FBI: What Journalists Need to Know [2025]

- Blue Origin Pauses Space Tourism to Focus on Moon Missions [2025]

- Don Lemon and Georgia Fort Arrested for Covering Anti-ICE Protest [2025]

- Neil Young's Greenland Music Donation & Amazon Boycott [2025]

![Washington Post's Tech Retreat: Why Media Giants Are Abandoning Silicon Valley Coverage [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/washington-post-s-tech-retreat-why-media-giants-are-abandoni/image-1-1770329375277.jpg)