Understanding Winter Storms: What Makes Them Dangerous

Winter storms don't announce themselves like hurricanes do. There's no spinning mass of organized clouds you can watch for days ahead. Instead, they develop quietly, forming from atmospheric patterns that shift constantly. A winter storm can change its entire personality between Wednesday and Friday, transforming from manageable snow to crippling ice. This unpredictability is why meteorologists get frustrated—and why you should too.

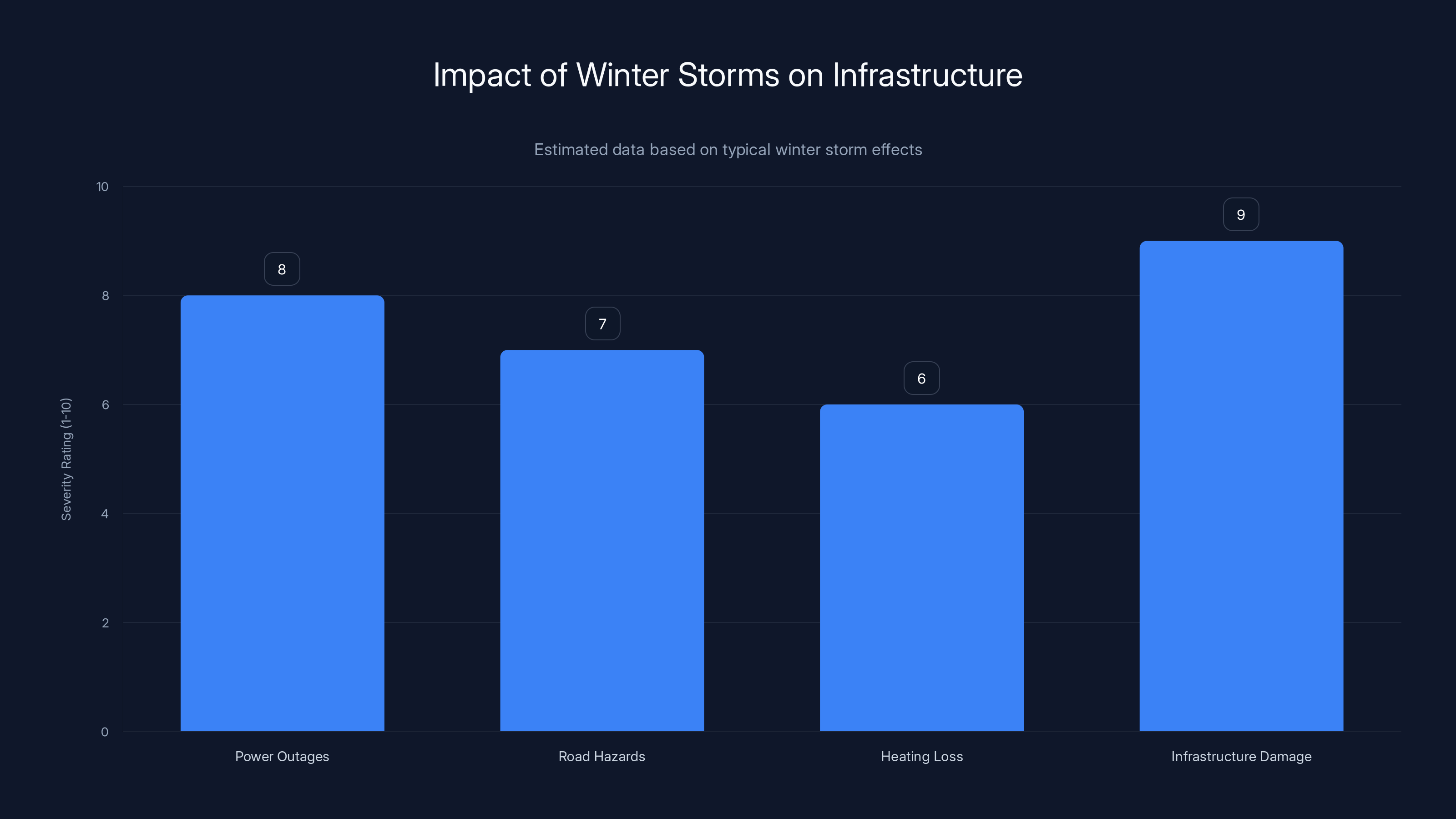

When a winter storm hits the United States, it doesn't just bring snow. It brings a cascade of problems: power outages that can last for weeks, roads that become skating rinks, and temperatures that plummet just when people lose their heating. The worst part? Many regions that get hammered by these storms have almost zero experience dealing with them. A region that sees winter weather once every five years doesn't maintain salt stockpiles. Its infrastructure isn't designed for it. Its population doesn't know how to drive in it.

In 2021, a winter storm in Texas knocked out power for millions of people. For two weeks. Nearly 250 people died. That was only four years ago. Now, meteorologists are watching patterns that could bring similar conditions back to unprepared regions. The data coming from weather models is pointing toward heavy freezing rain for areas that have never dealt with it before.

The Anatomy of a Dangerous Winter Storm

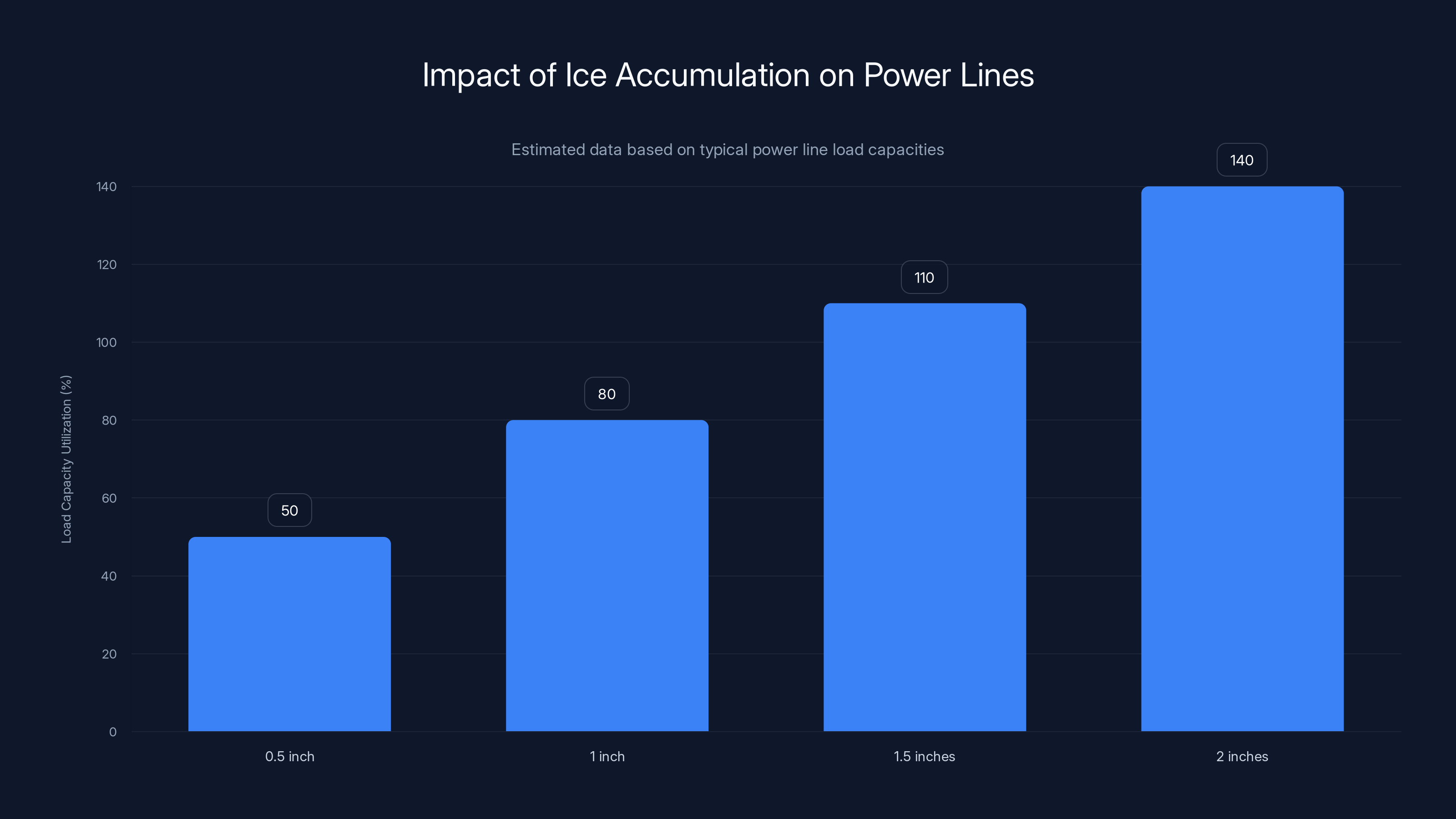

Freezing rain is the villain in winter storm stories. Unlike snow, which piles up and looks benign, freezing rain is deceptive. It starts as liquid. It falls from the sky as rain. Then it hits the ground and transforms into ice. This happens on power lines, where it accumulates layer upon layer. A power line designed to handle one inch of ice coating might fail under two inches. Three inches, and you're looking at catastrophic collapse.

The weight is insane. A single inch of ice can add thousands of pounds to a power line. Trees snap. Branches come down across roads and onto other power lines. Power lines fail. Thousands of people lose electricity. And then it gets cold. Really cold. If the temperature drops to 20 degrees and you lose power, your house becomes dangerous within hours.

Snow by itself? That's manageable in most cases. Snow piles up, you plow it, traffic slows down. Annoying, but not catastrophic. Freezing rain, though—that's the stuff that keeps meteorologists awake at night.

How Meteorologists Predict Winter Storms

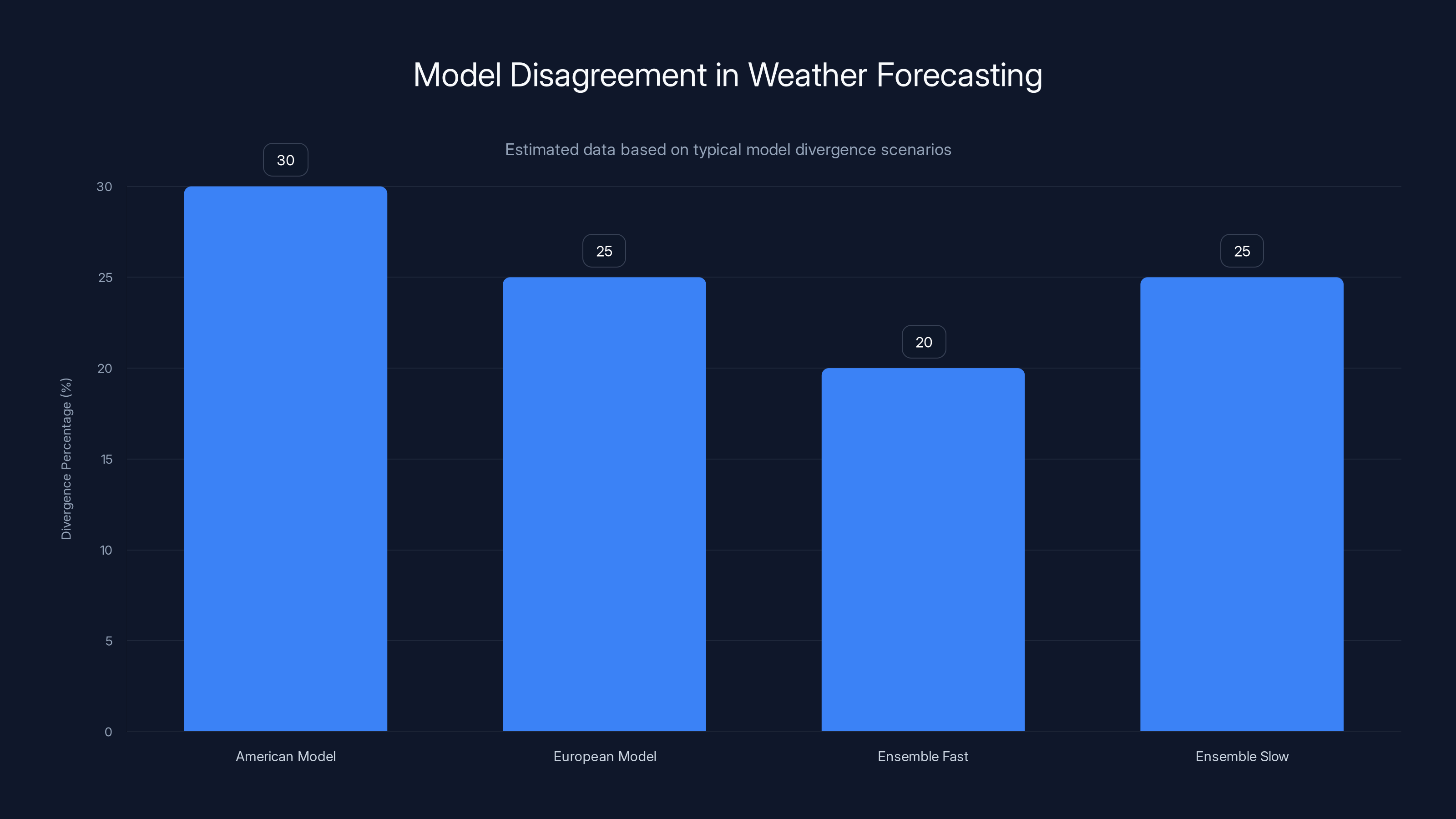

Weather forecasting relies on computer models. These models take current atmospheric conditions—temperature, pressure, moisture, wind patterns—and run simulations of how they'll evolve. The US National Weather Service runs multiple models. European meteorological agencies run their own. Private companies run theirs. Sometimes they all agree. Sometimes they're wildly different.

The models work by dividing the atmosphere into a three-dimensional grid and calculating physics at each point. Temperature affects pressure, which affects wind, which affects moisture transport, which affects precipitation. Change one variable slightly, and the whole system shifts. This is chaos theory in action. It's why forecasts beyond 10 days are nearly useless, and why even five-day forecasts have significant uncertainty.

What makes winter storm forecasting especially difficult is that small changes in atmospheric positioning can mean the difference between a foot of snow and crippling ice. If a high-pressure system parks itself 50 miles east of where the model predicted, warm air flows in from the south. Rain that was supposed to freeze becomes rain. Areas that prepared for ice get rain instead. Areas that didn't prepare get ice instead.

The Current Atmospheric Setup: What's Different This Time

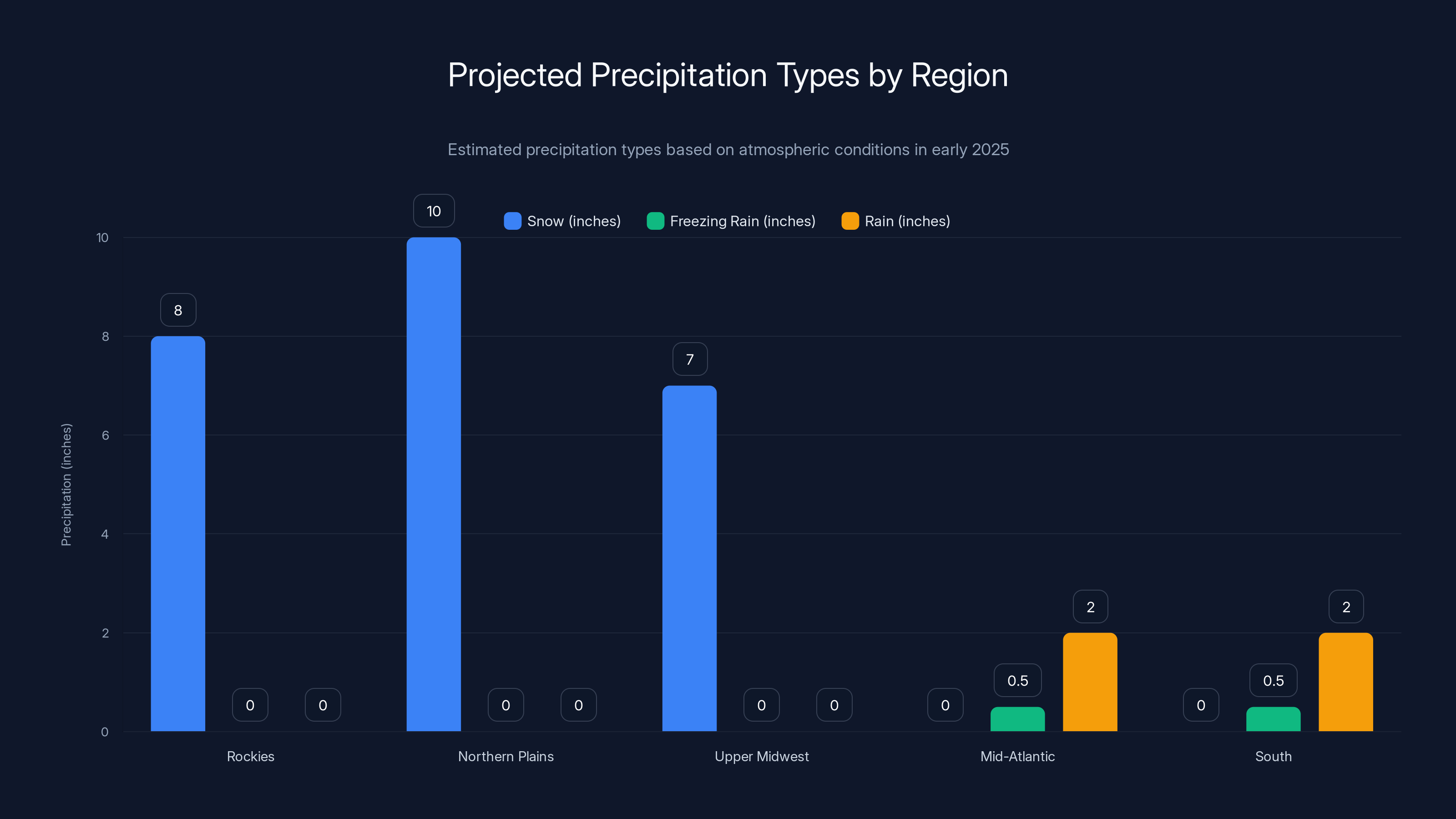

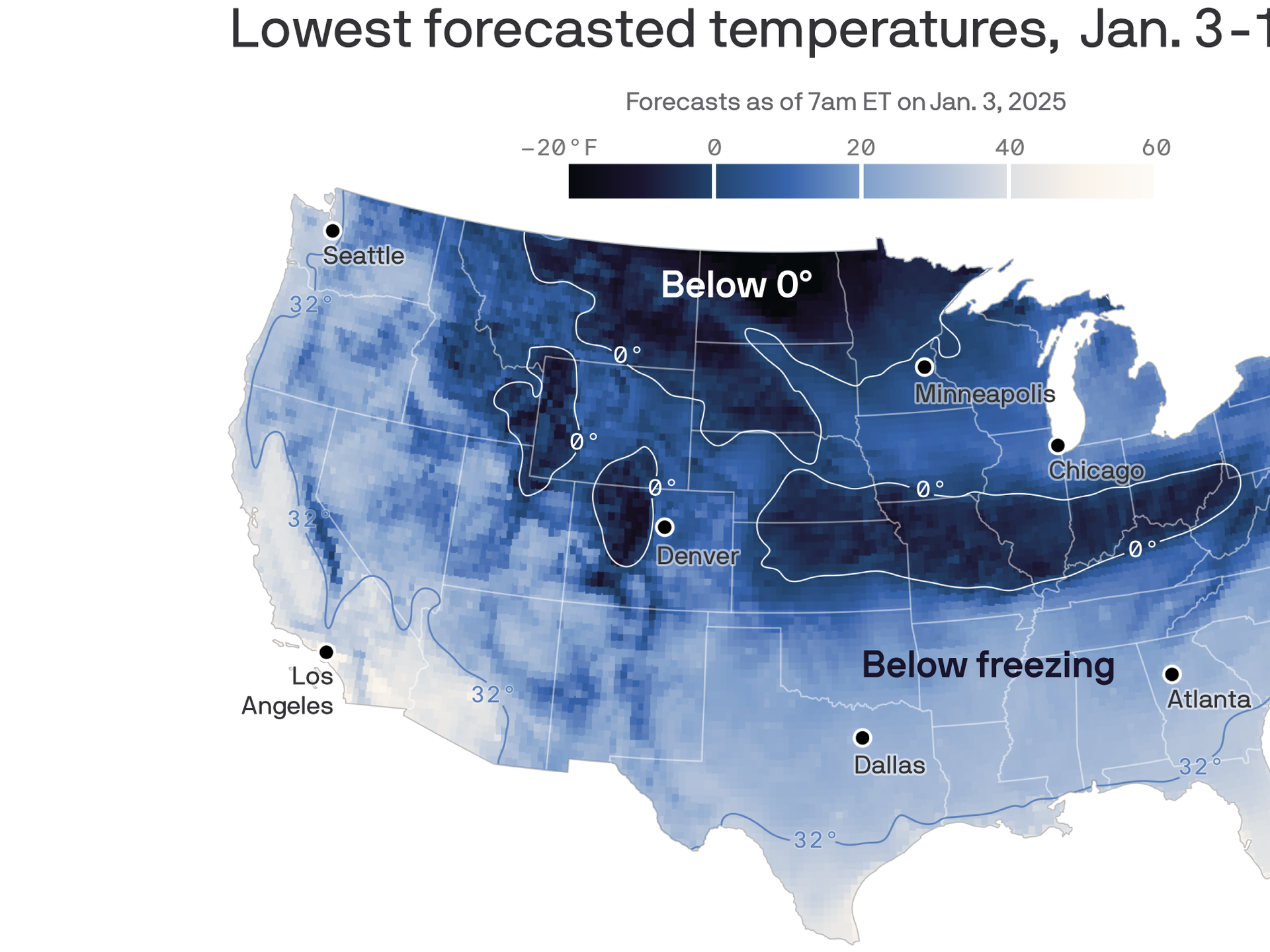

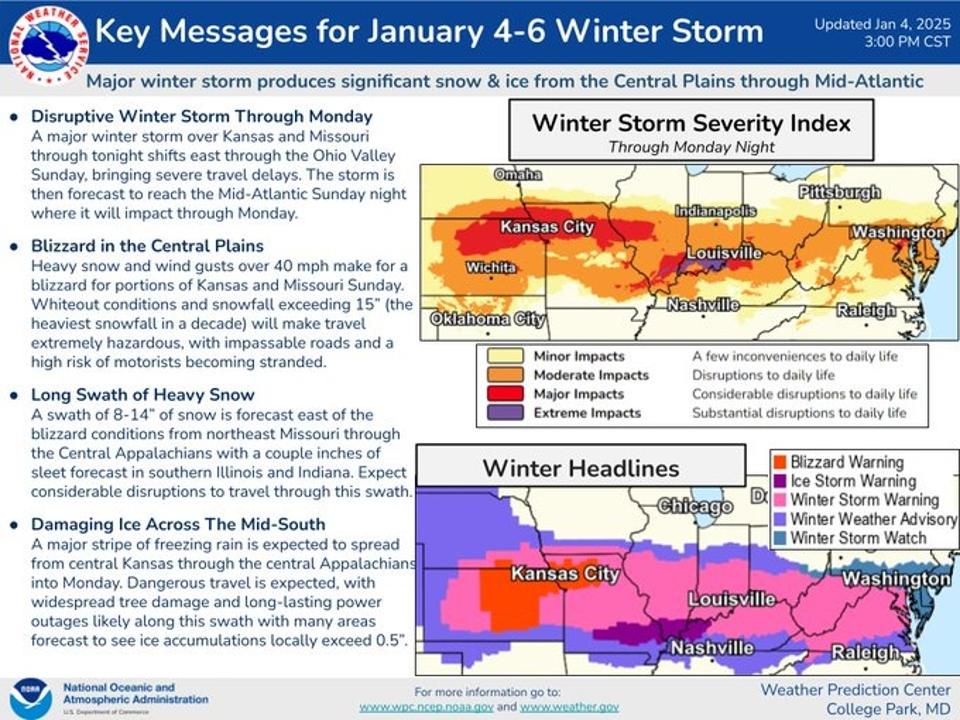

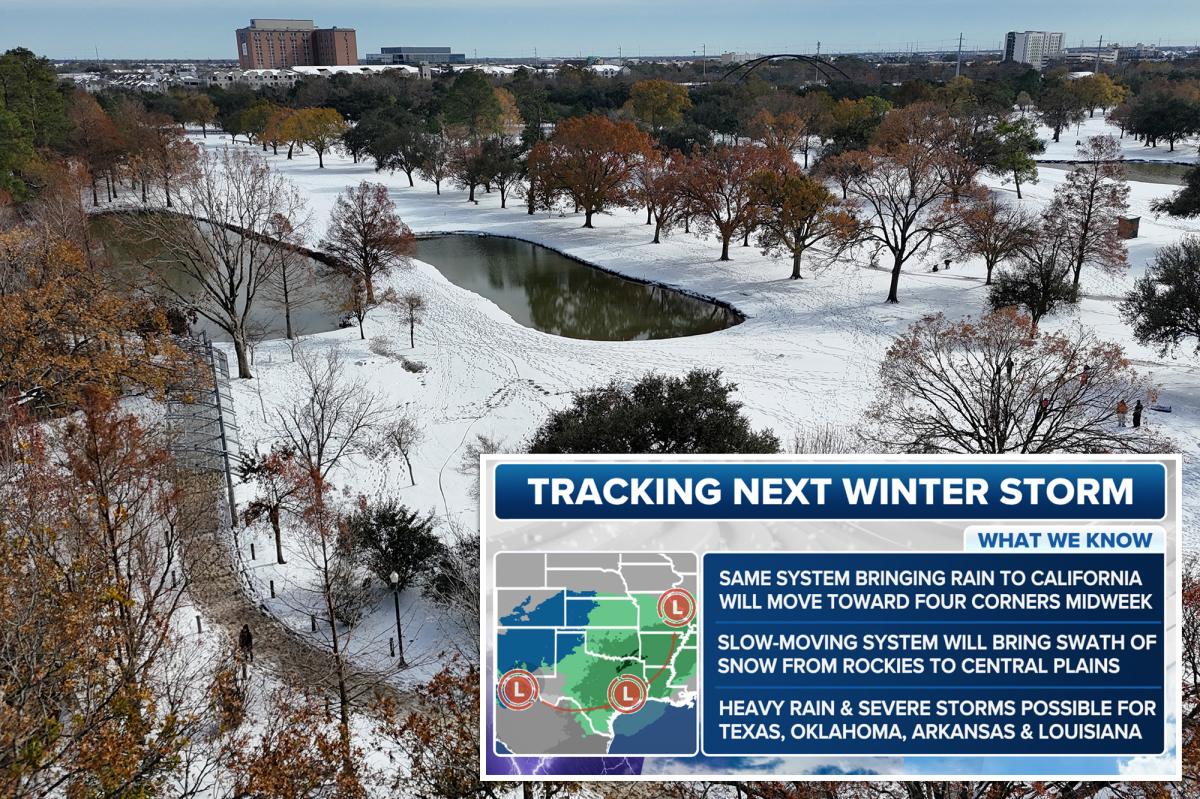

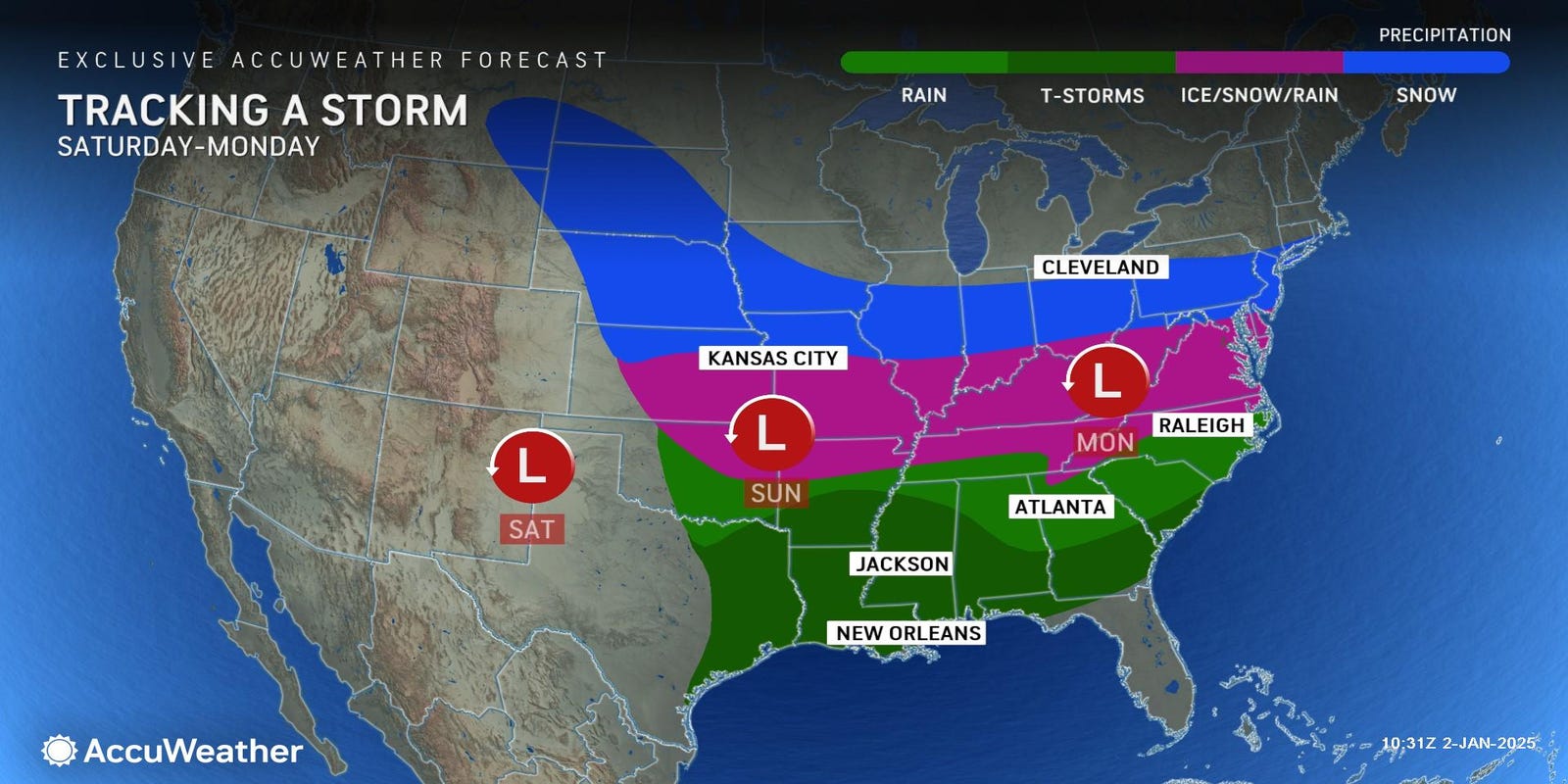

In early 2025, atmospheric conditions are aligning in a particular way. A moisture-rich system is forming over the Pacific, gathering humidity from warm ocean waters. This system is heading east. Meanwhile, cold air is settling in over the northern United States. These two systems are going to collide.

When a warm, moist system meets cold air, you get precipitation. The type of precipitation depends on the temperature profile of the atmosphere above. If the air is cold all the way down, you get snow. If there's a layer of warm air in the middle with cold air below, you get freezing rain. If the layer of warm air is really thick, you get plain rain.

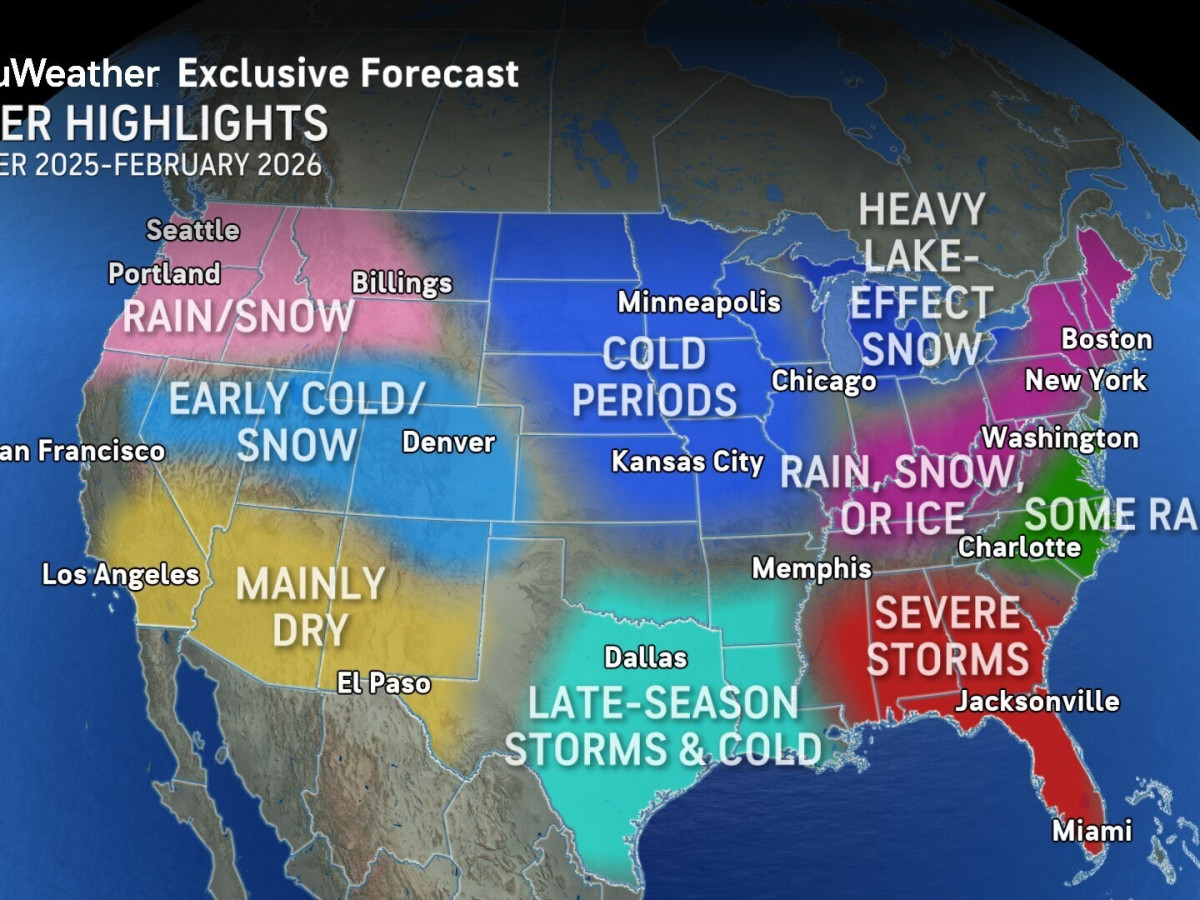

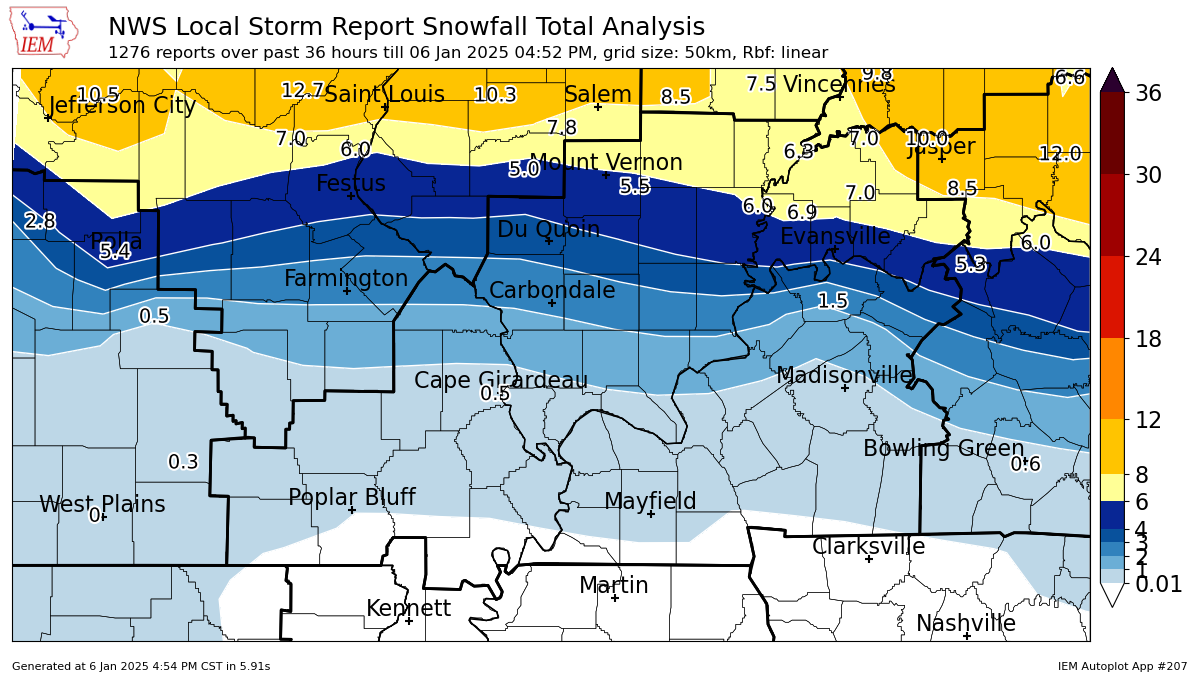

The current setup suggests that different regions will experience different precipitation types. Areas farther north and west—the Rockies, the northern Plains, maybe the upper Midwest—look like they'll get heavy snow. Areas in the mid-Atlantic and potentially the South look like they could get freezing rain or a mix.

Moisture Content and Storm Intensity

Atmospheric scientists measure moisture by tracking the water vapor content in the air. A "waterlogged" atmospheric system means there's an enormous amount of moisture available. The system developing for this winter event has pulled moisture from the Gulf of Mexico and the Atlantic. This guarantees that wherever the storm system goes, there will be substantial precipitation.

When meteorologists say "2 to 4 inches of water equivalent," they mean that if all the moisture in the atmosphere above a point fell as rain, you'd get 2 to 4 inches. But it's not going to fall as rain everywhere. That same moisture falling as snow produces much more accumulation. Two inches of water equivalent can mean eight inches of snow in cold air, or half an inch of ice in freezing conditions.

The abundance of moisture is actually one of the things meteorologists are most confident about. That's relatively easy to measure. It's the atmospheric setup that determines whether that moisture becomes snow, ice, sleet, or rain.

The Upper-Level Low: The Wildcard

Above the surface, in the upper atmosphere, weather systems form at much larger scales. One critical feature for this storm is what meteorologists call an "upper-level low"—a region where air pressure is lower than surrounding areas. This low is forming over the Pacific and will move eastward.

The position of this upper-level low matters enormously. If it tracks further north, the storm system gets pushed north, and the northern tier of the country gets the worst of it. If it tracks further south, the storm system stays south, affecting more of the mid-Atlantic and Southeast. The models disagree on exactly where this feature will track.

Right now, some models show it moving further north than others. That's the source of uncertainty. A difference of 100 miles in the position of this upper-level low could mean the difference between Virginia getting a foot of snow or half an inch of ice.

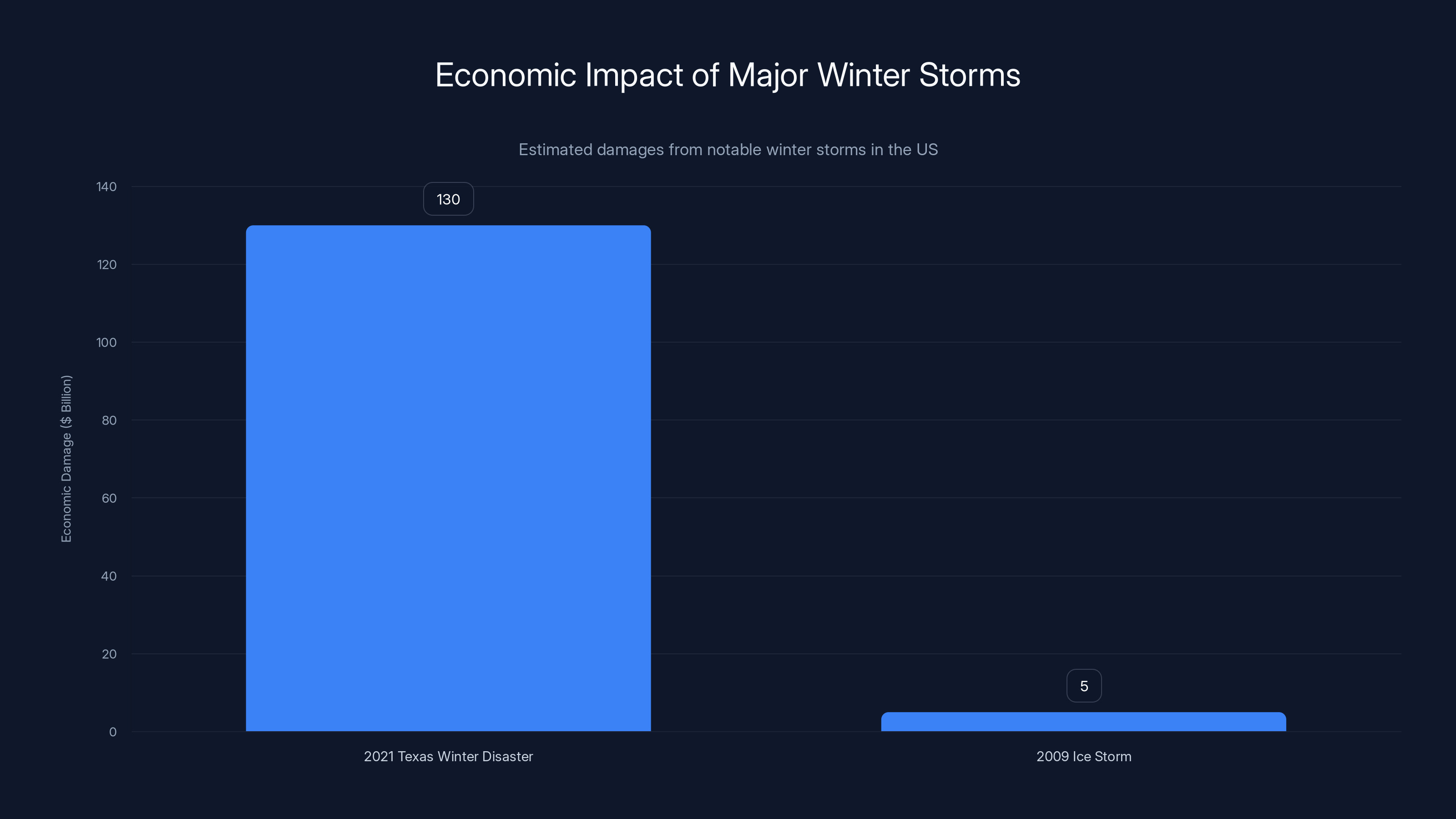

The 2021 Texas Winter Disaster caused an estimated $130 billion in damages, highlighting the severe impact of winter storms on unprepared regions. Estimated data.

Geographic Impact Zones: Where It Gets Scary

The forecast areas affected by this storm span nearly 30 states. That's a huge area. But within that area, conditions vary dramatically. Understanding the geography helps you understand why some areas are terrified and others aren't.

The Mountain West and Northern Plains

The Rockies and the northern Great Plains—places like Colorado, Wyoming, Montana, parts of New Mexico—are looking at significant snowfall. These regions have experience with winter weather. They maintain equipment to handle it. They have supply chains set up. When it snows in Denver, people are annoyed, but the city keeps functioning.

Snow forecasts for these regions are relatively certain. The models agree that cold air will move into the region and moisture will fall as snow. Accumulations might range from six inches to two feet, depending on the exact track, but it'll be snow, not ice.

These regions can handle snow. They've got the infrastructure. The concern here isn't catastrophic failure—it's just the normal inconvenience of winter weather in regions that get winter weather.

The Mid-Atlantic: The Danger Zone

Virginia, West Virginia, Kentucky, eastern Tennessee, North Carolina—these regions are in meteorologists' crosshairs. The models are showing potential for heavy freezing rain in these areas. Some models show crippling amounts of ice.

These regions do not have winter weather infrastructure. Virginia's last significant ice storm was in 2009. Since then, the state has lost institutional knowledge. Equipment operators who knew how to handle ice storms have retired. New people have never dealt with it. The power grid was upgraded in some places but not everywhere. Some rural areas still have wooden poles and minimal redundancy.

If heavy freezing rain hits Virginia, there's a real possibility of widespread power outages affecting hundreds of thousands of people. If that happens in late January when nighttime temperatures are in the teens, it becomes a public health emergency. Heating is life-or-death. Lack of heat plus below-freezing temperatures equals dead people.

The South: Experience Gap Problem

Georgia, Tennessee, the Carolinas, even parts of Texas—these regions occasionally see winter weather, but it's rare enough that preparedness is always reactive. Atlanta doesn't salt roads regularly because winter weather happens maybe once every two years. When it does happen, the city shuts down. Schools close. Governments declare emergencies.

In 2014, an ice storm swept through Georgia and left some areas without power for days. People died from hypothermia. The region's response was to learn lessons, but five years is a long time. New infrastructure has been built. Some old equipment has been replaced. But fundamental preparedness is still lower than it would be in a region that experiences winter weather regularly.

The South is also vulnerable to a specific problem: mixed precipitation. If snow falls first, then melts as a warm layer passes through, then refreezes as another cold layer arrives, you get layers of ice and sleet. This is harder to deal with than pure snow or pure ice. Roads become impassable. Plows have trouble. Parking lots become skating rinks.

Winter storms severely impact infrastructure, with power outages and infrastructure damage rated highest in severity. Estimated data.

The Uncertainty Problem: What We Can't Predict

Meteorologists will happily tell you what they don't know. Ask them. They're more honest about uncertainty than many other professions. With this storm system, there are several sources of major uncertainty.

Model Disagreement

Different computer models are showing different solutions for where this storm will track and how it will develop. The American model shows one track. The European model shows another. Some ensemble members show the storm developing faster. Others show it developing slower. Some show more ice. Some show more snow.

When models disagree, especially by large margins, the honest thing to say is: we don't know. The future depends on which model is right, and we won't know that until the storm actually happens. You can't make confident predictions when the models diverge.

The models might converge as more data comes in. Weather observations from planes, satellites, and surface stations feed into the models. As the storm system develops and gets closer, the models will have more real data to work with, and they should start to agree more closely. But days out, when the system is still over the Pacific, you're working with less observational data and more model uncertainty.

Temperature Profile Sensitivity

The exact temperature profile in the atmosphere above the surface determines what kind of precipitation falls. If the surface is 28 degrees and there's a layer of warm air (above 32 degrees) aloft, with cold air above that, you get freezing rain. If that warm layer is one degree warmer, you might get rain instead. If it's one degree colder, you might get sleet instead.

Small differences in temperature create large differences in precipitation type. And predicting the precise temperature profile of the atmosphere days in advance is genuinely difficult. Surface observations can tell you what's happening at ground level. Upper-air observations from balloon soundings and satellite data can tell you what's happening higher up. But there are gaps. There's uncertainty.

A shift in a warm air mass by just a few degrees can shift the entire precipitation type for a region. The models are trying to predict this, but it's at the edge of what they can do accurately.

Timing Uncertainty

When exactly will the storm arrive in different areas? Will snow start Friday or Saturday? Will the worst ice occur Saturday night or Sunday night? These timing questions matter because they affect how much ice can accumulate and whether power outages happen during the day or night.

Timing is difficult to predict. A storm system that arrives 12 hours earlier or 12 hours later could see dramatically different conditions because of how atmospheric temperatures evolve. A 12-hour shift can mean the difference between cold enough for snow and warm enough for freezing rain.

The models are trying to predict this timing, but uncertainty in the track of the system translates to uncertainty in the timing.

Intensity: How Much Will Fall?

Will we get six inches of snow or 18 inches? Will we get a trace of ice or a half-inch? The models are showing a range. Some show lighter precipitation. Some show heavier. The actual amount that falls will depend on how the storm system structures itself—how deep the low-pressure center gets, how strong the winds are, how efficient the precipitation is.

Storm intensity forecasting is improving with better models, but it's still not perfect. A model might show the right track but overestimate or underestimate the intensity. Or it might show the right intensity in the wrong place.

Historical Context: Why This Matters

To understand why meteorologists are taking this seriously, you need to understand what happened in the past. Winter storms in unprepared regions have killed people and caused billions in damage.

The 2021 Texas Winter Disaster

In February 2021, a winter storm brought unusually cold temperatures to Texas. Naturally, the state wasn't prepared. Texas doesn't stockpile road salt or maintain fleets of snowplows because winter weather is rare. When the storm arrived, roads became impassable. Power demand spiked as people ran heating. The state's power grid, which includes a lot of renewable energy that produces less in winter, couldn't keep up. Rolling blackouts started. Then blackouts became prolonged outages.

People died. Some froze to death. Some died from carbon monoxide poisoning from improperly vented heaters. Some died from medical emergencies that couldn't be reached by ambulances. The state lost power for two weeks in some areas. The economic damage was estimated at $130 billion. Federal aid had to be distributed to help people and businesses recover.

That storm wasn't even that extreme. It was just extreme for Texas. Most of the US experiences much worse winter weather regularly. But Texas's infrastructure wasn't designed for it, and when it happened, the failure cascaded through systems: power, transportation, water, supply chains.

The 2009 Ice Storm

In 2009, an ice storm hit the mid-Atlantic and caused weeks of power outages across Kentucky, Virginia, and West Virginia. Hundreds of thousands of people lost power. Some were without electricity for two weeks. People died from hypothermia. The damage was in the billions of dollars. Ice had accumulated on power lines faster than utilities could clear it, and the weight brought down entire transmission infrastructure.

Utilities learned lessons from that storm. Some reinforced poles. Some trimmed more trees. Some improved response protocols. But not everywhere improved equally. And new development often happens with minimal attention to weather resilience.

Pattern Recognition: Are These Getting Worse?

Some people ask if winter storms are getting worse. The answer is complicated. Winter storms overall haven't become more frequent in most places. But the variability has increased. You get longer warm periods followed by sudden cold snaps. You get more mixed precipitation events. And as regions develop more and more infrastructure dependent on power, the consequences of power outages become more severe.

A winter storm in 1980 killed people, but it didn't shut down the internet or disrupt supply chains or cause healthcare systems to fail. Today, those systems have single points of failure. A widespread power outage from ice damage now cascades through multiple systems. That's not because storms are worse, but because our dependence on infrastructure that requires power has increased.

Estimated data suggests heavy snow in the Rockies and Northern Plains, while the Mid-Atlantic and South may experience freezing rain or rain due to atmospheric conditions in early 2025.

What Meteorologists Know With Confidence

Meteorologists don't know everything about this storm. But they do know some things. Understanding what they're confident about helps you understand what they're uncertain about.

A Major Storm System Is Coming

There's broad agreement among models that a significant weather system is moving from the Pacific toward the continental United States. This isn't a minor system. This is a system with a lot of moisture and a lot of energy. It will produce precipitation over a wide area.

The Moisture Content Is Substantial

The system is drawing moisture from the Gulf of Mexico and the Atlantic. This is measurable and verifiable. There's enough moisture in the atmosphere above a wide region to produce significant precipitation. Where and in what form is uncertain, but that something substantial will fall is not.

Cold Air Is in Place to the North and West

Temperature patterns are favorable for cold air to remain in place. In the northern tier of the country, the Rockies, and the high plains, you'll have below-freezing air. This favors snow. In the mid-Atlantic and Southeast, the setup is more complicated, but there's definitely cold enough air for freezing rain if the atmospheric conditions line up right.

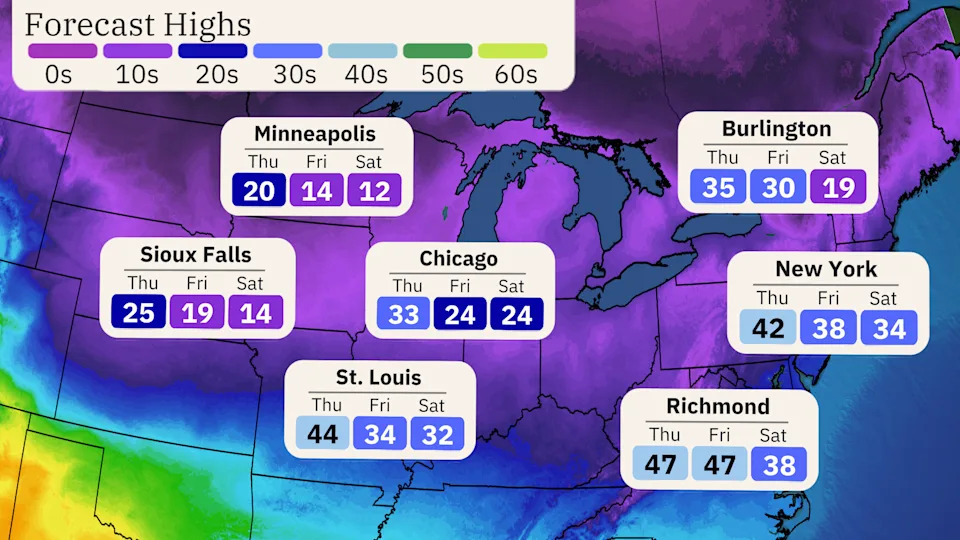

Timing Is Roughly Friday Through Sunday

The system will move into the region this Friday or Saturday and progress eastward through the weekend. By early next week, it'll be offshore. There might be some lingering precipitation into Monday, but the primary event is this weekend.

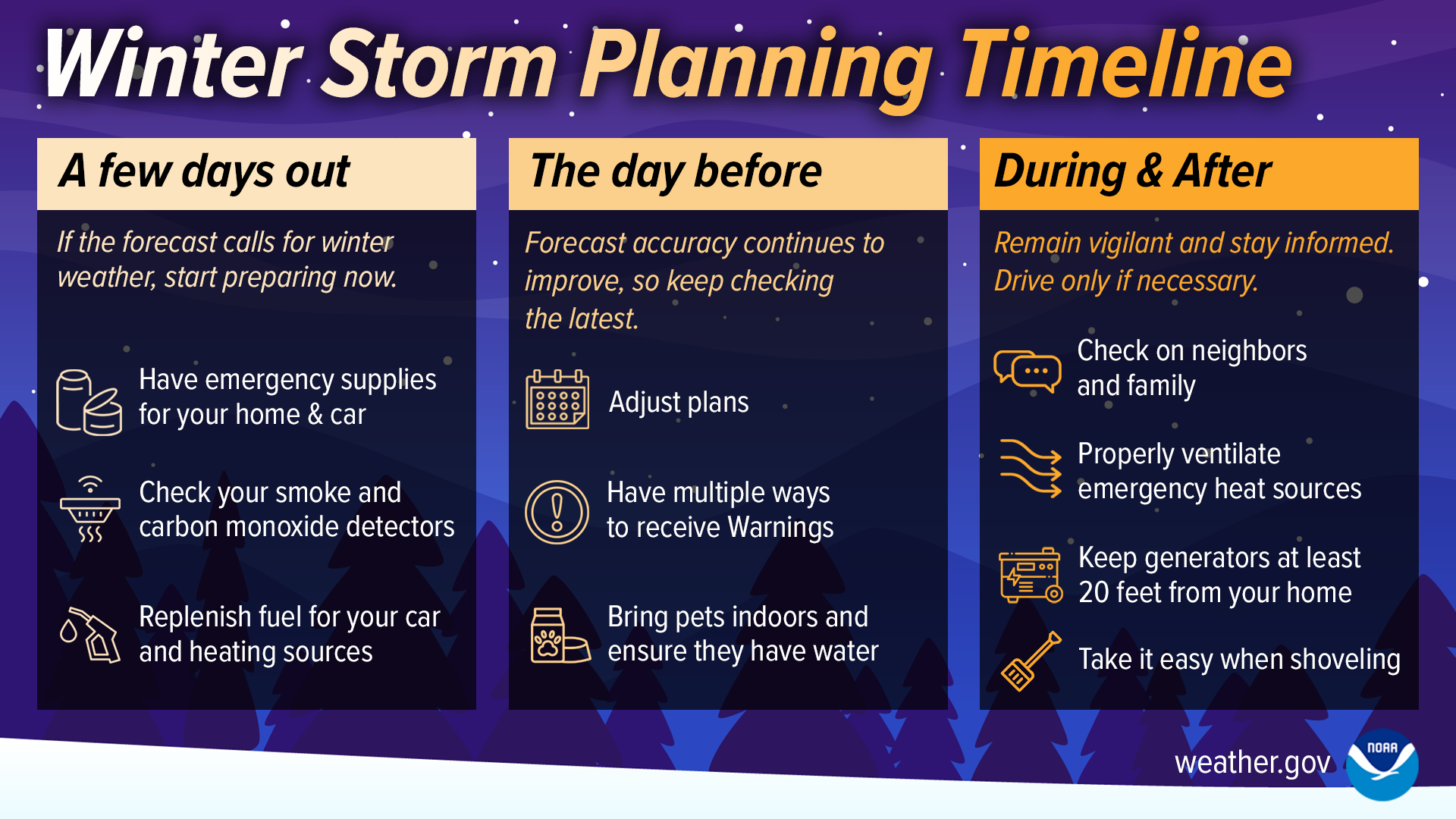

Preparation Recommendations: What You Should Do Now

Regardless of exactly what your area gets, preparing now makes sense. Preparation isn't about panic. It's about being ready for the most likely scenarios.

Stock Supplies Before the Storm Arrives

Don't wait until Friday to prepare. By Thursday, stores will be crowded and shelves will be picked over. Go now and get: food that doesn't require cooking (canned goods, bread, peanut butter), water (one gallon per person per day for three days minimum), flashlights and batteries, medications if you need them, and fuel if you use heating oil.

If you have an electric heater, get that ready now. Test it to make sure it works. If you have a fireplace, make sure you have firewood. If you don't have any way to heat a room without electricity, figure something out now.

Check Your Vehicle

If you're in an affected area, make sure your car has sufficient gas (at least half a tank). Keep jumper cables, a small shovel, blanket, and flashlight in the car. If it's snowing, assume you might get stuck. Make sure you can survive in your car for a few hours with the heat running.

Charge Devices and Prepare Battery Backups

Charge your phone, laptop, and any other devices. A power bank can keep your phone charged if the power goes out. Your phone is your connection to emergency services and information. Keep it charged.

Prepare Your Home

If you have a backup heating source like a wood stove or fireplace, make sure it's ready. If you don't have one, a space heater in one small room is better than heating the whole house. Seal windows with plastic or blankets to reduce heat loss. Make sure you can close off areas of your home and concentrate heat in one area.

If you have a generator, make sure it works and you have fuel. Never run a generator indoors—carbon monoxide poisoning kills people. Always use it outside.

If you have medical equipment that requires electricity—CPAP machines, nebulizers, refrigerated medications—figure out how you'll power it if the grid goes down. Some utilities will put you on a priority restoration list if you report this.

Check on Vulnerable People

Before the storm arrives, identify people in your area who might be vulnerable: elderly neighbors, people living alone, people with medical conditions. Check in with them. Make sure they have supplies. Offer to help if needed.

Estimated data shows typical divergence percentages among different weather models, highlighting the uncertainty in storm tracking predictions.

Misinformation and Hype: What to Ignore

Winter storms attract hype. People extrapolate, models get misrepresented, clickbait gets generated. Meteorologists are frustrated by this. The public sees ten different forecasts from ten different sources and doesn't know which to trust.

The Problem With Doomscrolling

Social media amplifies extreme forecasts. A meteorologist runs a model and posts the most dramatic scenario it shows, not the most likely scenario. This gets shared, retweeted, screenshot. People see apocalyptic predictions. Then they see contradictory predictions from other sources. The result is confusion and either panic or dismissiveness.

Here's the thing: sometimes the dramatic scenario happens. Sometimes it doesn't. But what's important is to focus on official forecasts from meteorological agencies, not social media posts from people trying to build followers.

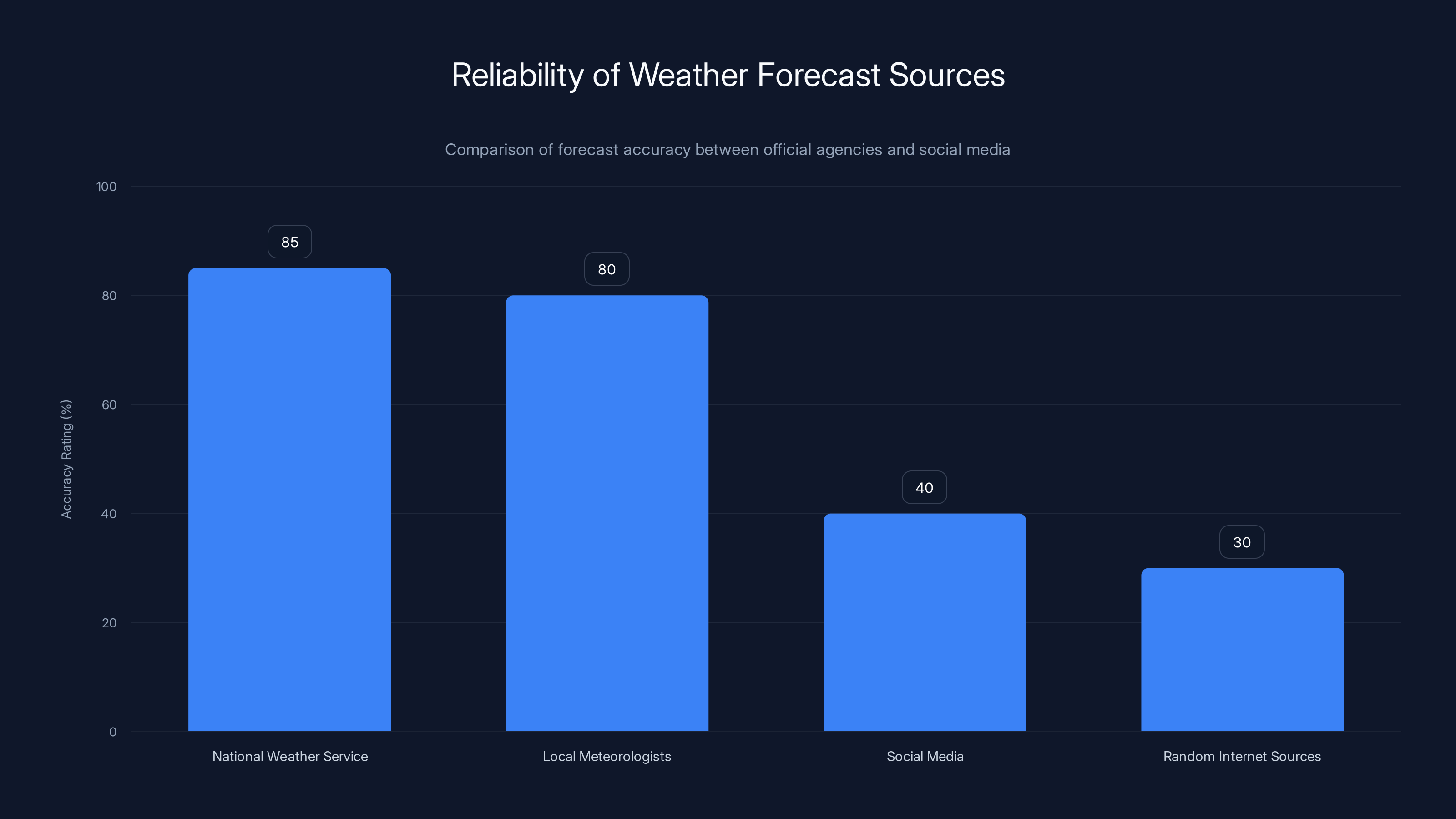

Official Forecasts vs. Clickbait

The National Weather Service issues forecasts based on multiple models and meteorological expertise. These forecasts are updated constantly as new data comes in. They represent the best judgment of meteorologists using the best available data. They're not always perfectly accurate, but they're better than predictions from random people on the internet.

Local National Weather Service offices have meteorologists who understand your local geography. They know which valleys get cold air trapped in them. They know which areas are prone to freezing rain. They know the history of storms in your region. Their forecasts, specifically for your area, are more accurate than national forecasts.

Handling Conflicting Information

When different forecasts disagree, that's actually useful information. The disagreement tells you something is uncertain. If the models all agreed on crippling ice, you'd know ice is probably coming. If they disagree, you should prepare for the worst case while hoping for the best case.

The worst approach is to dismiss the worst-case scenario because you hope it won't happen. A better approach is to take actions that help you regardless of which scenario happens: stock supplies, prepare your heat source, identify how you'll get information if power goes out.

Infrastructure Vulnerability: Why Power Outages Matter

If this storm delivers heavy freezing rain to unprepared areas, power outages are the most likely serious consequence. Understanding power infrastructure helps you understand why.

How Freezing Rain Damages Power Lines

Power lines hang from wooden or metal poles. The lines themselves are designed to handle certain loads. Weight of ice, wind pressure, tension from sagging lines—all of this is calculated. A power line rated for one type of load fails when loads exceed its design.

Freezing rain accumulates on power lines. Each layer of ice adds weight. If a power line has a half-inch of ice, it might be fine. One inch, and it's approaching the rated load. Two inches, and it's overloaded. As the ice accumulates, the line sags. As it sags, tension increases. Eventually, something breaks. The line snaps. Or the connection to the pole fails. Or the pole itself breaks under the increased load.

One thing people don't understand: trees break too. Branches coated in ice become incredibly heavy. An old oak tree might have branches extending over power lines. The branch gets coated in ice, becomes too heavy, breaks, and falls on the line. This happens across thousands of trees in a region. Pretty soon, you've got a massive problem.

Utility Response Capabilities

When power outages occur, utilities send out line crews to repair damage. But if the damage is widespread, utilities can run out of crews. During the 2009 ice storm, some areas waited two weeks for repairs because the damage was so extensive that utilities needed help from other regions. Crews from unaffected states had to drive in to help repair lines.

Utilities have improved response capability since 2009. They've got mutual aid agreements. They can stage extra crews in advance of predicted storms. But if the storm is worse than predicted or affects a larger area than predicted, response gets overwhelmed.

Cascade Failures

When a large area loses power, other systems fail. Pumping stations that move water lose power and can't pump. Water treatment plants lose power. Hospitals that are on the grid (most are) lose power but have backup generators. But backup generators run on fuel that needs to be delivered, and roads are impassable. Gas stations lose power and can't pump fuel. Supply chains get disrupted.

A widespread power outage in winter isn't just inconvenient. It becomes a public health emergency pretty quickly.

Official forecasts from the National Weather Service and local meteorologists are significantly more reliable than those found on social media and random internet sources. Estimated data.

Timing Details: When This Storm Happens

The storm doesn't arrive all at once. It develops over time. Understanding the timeline helps you understand when to worry most.

Friday: Initial System Movement

The system is expected to start affecting the western United States on Friday. This is snow territory. Rain, snow, windy conditions in the Rockies and High Plains. This is manageable weather. It'll be cold and snow will accumulate, but it's not dangerous in the way that ice is dangerous.

Friday is when people in the Midwest and Great Plains should start preparing. By Friday evening, you should have what you need. If the system arrives faster than expected and you're in the path, you don't want to be caught needing supplies on Friday night.

Saturday: The System Reaches the Midwest and Mid-Atlantic

By Saturday, the system is over the Midwest. Areas in the Great Lakes region, Ohio Valley, and upper South are getting precipitation. This is where you start seeing mixed precipitation—rain, sleet, freezing rain. Roads might get icy. Visibility might decrease. Driving conditions get hazardous.

Saturday is still not the worst-case scenario in most areas. Ice accumulation hasn't reached dangerous levels yet. But power outages could start happening Saturday night if ice accumulates faster than expected.

Saturday Night Through Sunday: The Dangerous Period

Saturday night into Sunday is when the storm reaches the mid-Atlantic and potentially the upper South. This is where the worst-case scenario of heavy freezing rain could materialize. If the models that predict significant ice for Virginia and the Carolinas are right, this is when it happens.

This is when you want to be done with preparations. You want heat secured. You want supplies in your home. You want information sources figured out. If power goes out Saturday night, Sunday is a full day without power with temperatures potentially in the 20s. That's uncomfortable. Monday is another full day. That becomes dangerous.

Sunday Night Through Monday: Clearing Begins

By Monday, the system is moving offshore into the Atlantic. Precipitation ends. Cloud cover decreases. The immediate danger from the storm passes. But lingering effects might persist—power might still be out, roads might still be impassable.

Meteorologists will know by Monday morning whether the worst-case scenario happened or whether the system developed differently. By then, you'll know whether your area got snow, ice, or rain.

Local Impacts: Different Regions, Different Concerns

This storm affects many regions, but the impacts are different depending on the region.

The Pacific Northwest

The system starts here. Rain and snow in the mountains. Some areas will see heavy snow. Some areas will see rain. Supply chains might get disrupted if passes close. But this region is used to winter weather and has infrastructure to handle it.

The Mountain West and High Plains

Snow, wind, blowing snow. Visibility might be reduced. Roads might be slick. Temperature will drop significantly. This is winter weather, but it's weather these regions experience regularly. Preparedness is reasonably high.

The Midwest

Mixed precipitation, potentially significant accumulation in some areas. This region has experience with winter storms and maintains good infrastructure. Roads will be slick, but they'll get plowed. Power outages are possible but less likely than in the South.

The Mid-Atlantic

This is where uncertainty is highest and consequences could be worst. Freezing rain is possible. Ice accumulation could be significant. This region doesn't have good experience with winter weather and infrastructure might not be able to handle it. If ice is heavy and widespread, power outages affect millions and last for extended periods.

The Southeast

Different models show different impacts. Some show snow. Some show freezing rain. Some show sleet and mixed precipitation. This region is least prepared for winter weather and most vulnerable to disruption if the worst case happens.

The Northeast

Models are more confident here. Snow is more likely than ice. Accumulation could be significant. This region is well-prepared for winter weather and has good infrastructure. Roads might close, but they'll get reopened. Utilities will respond quickly to any outages.

As ice accumulation on power lines increases from 0.5 to 2 inches, the load capacity utilization can exceed 100%, leading to potential failures. Estimated data.

The Role of Climate Change

Some people ask whether climate change is causing more winter storms or making them worse. The actual scientific answer is complicated, and it's worth understanding.

Winter Is Warming Faster Than Summer

The Arctic is warming much faster than other parts of the planet. As Arctic ice decreases and the temperature gradient between the Arctic and mid-latitudes decreases, atmospheric patterns change. Some research suggests that this can lead to more variable winter weather, with alternating periods of extreme cold and extreme warmth.

But more variable doesn't necessarily mean more winter storms. Some models suggest that winter storms might become less frequent but potentially more intense. Other models suggest different patterns. The science is still evolving.

Moisture and Intensity

Warmer air holds more moisture. So atmospheric systems have more moisture to work with. A storm system with more moisture can produce more precipitation. So if a storm does occur, it might produce more total accumulation than historical storms.

This particular system is pulling moisture from warm Gulf and Atlantic waters. The waters are warmer than they would have been 50 years ago. So the system has more moisture available. Whether the storm will be more intense than historical storms is hard to say, but the conditions are favorable for a moisture-rich system.

How to Stay Informed Without Freaking Out

Once you're prepared, the best thing you can do is stay informed without obsessing. Here's how.

Best Information Sources

The National Weather Service has local offices for every region. Their website has hourly forecasts, hazard alerts, and detailed discussions of the forecast reasoning. This is the official source. Everything else is interpretation of this data.

National news organizations will cover the storm. They'll interview meteorologists. Some will sensationalize. Some will be accurate. Be skeptical of dramatic language and look for actual data.

Local meteorologists at local news stations know your area. They're familiar with local geography and local infrastructure vulnerabilities. They're a good secondary source, especially for how the storm will specifically affect your area.

Avoid doomscrolling weather-related posts on social media. People post their worst-case interpretations and their dramatic predictions. It doesn't help.

Frequency of Checking Forecasts

Check the official forecast once a day. Twice a day if major changes are happening. More frequently than that doesn't help—the forecast isn't changing that much. The updates are incremental. You're not getting fundamentally new information from hourly updates.

Prepare Once, Don't Panic

After you've stocked supplies, charged devices, and secured your heat source, there's nothing else to do. You're prepared. Spending the next few days in anxiety doesn't improve your situation. It just makes you miserable.

What Happens After the Storm

Once the storm passes, things don't automatically go back to normal.

Power Restoration

If widespread power outages occur, utilities will work 24/7 to restore power. But if damage is extensive, restoration takes time. In the 2009 ice storm, some areas waited two weeks for full restoration. More recent storms have been restored faster due to improved response, but widespread damage can still cause extended outages.

Utilities will restore power to critical infrastructure first: hospitals, water treatment plants, police and fire stations. Then they'll restore to major transmission lines and distribution hubs. Finally, they'll work on neighborhood-level service.

Road Clearing

After snow stops falling, road treatment begins immediately. Major highways are cleared first because they carry the most traffic. Secondary roads are cleared next. Residential streets are cleared last. In some areas, residential streets might not be fully cleared for a week after a major storm.

If the roads are icy, plowing won't immediately make them safe. Salt or sand needs to be applied to reduce slickness. In very cold temperatures, salt doesn't work well (it's less effective below 15 degrees). Then you're relying on sand or other traction aids, and roads remain slick.

Water System Effects

If water treatment plants lose power, water service can be affected. Some areas might lose water pressure. Boil water notices might be issued. This is uncommon but possible in extended outage scenarios.

Supply Chain Recovery

If major trucking corridors are closed, supply chains get disrupted. Grocery stores might run out of items if deliveries are delayed. Gas stations might run out of fuel if delivery trucks can't access them. Recovery happens quickly once roads reopen, but there can be a few days of disruption.

The Bigger Picture: Winter Weather Preparedness

This particular storm is significant, but it's not unique. Winter weather happens every year in the northern United States. Some years it's severe. Some years it's mild. But the risk is always there.

The best approach isn't to panic about individual storms. It's to have systems in place year-round. Know where your emergency supplies are. Know how you'll heat your home without electricity. Know which neighbors you can help and who can help you. Know your local weather service's website.

Communities are increasingly implementing resilience measures. Some utilities are upgrading equipment to be more ice-resistant. Some regions are implementing backup power systems. Some neighborhoods are creating community response plans for emergencies.

But the most important resilience is individual and community-level preparedness. When a winter storm hits an unprepared area, people die. When it hits a prepared area, people are inconvenienced. That difference is the difference between preparation and panic.

FAQ

What exactly is freezing rain and why is it so dangerous?

Freezing rain is precipitation that falls as liquid water, then freezes when it contacts surfaces. Unlike snow, it doesn't accumulate in a loose way you can shovel. Instead, it creates a solid sheet of ice on roads, power lines, and trees. The weight is deceptive: a quarter-inch of ice can weigh hundreds of pounds per square foot on power lines, causing them to fail and snap. It's the most dangerous form of winter precipitation because it's both heavy and makes surfaces extremely slippery, and infrastructure designed for snow isn't designed for ice loads.

How do meteorologists make winter storm forecasts?

Meteorologists use computer models that simulate atmospheric physics based on current conditions. These models divide the atmosphere into a three-dimensional grid and calculate temperature, pressure, wind, and moisture at each point. Different government agencies (US National Weather Service, European agencies) and private companies run their own models. When models agree, forecasts are more confident. When they disagree, uncertainty increases. Forecasts become more accurate as the storm system gets closer and more observational data becomes available.

What should I do if my area is under a winter weather advisory?

A winter weather advisory means conditions are possible that could be hazardous, but the forecast isn't certain enough for a warning. You should monitor forecasts, stock supplies if you haven't, and prepare backup heating. Check on vulnerable people. Have a communication plan. Don't panic, but take it seriously. The advisory is a heads-up to prepare.

Why do different forecasters predict different storms?

Different computer models sometimes produce different solutions because they use slightly different equations, different grid resolutions, and different ways of handling physical processes in the atmosphere. A model might show a storm system tracking north of its actual path, producing different impacts. As real observational data comes in, models converge and agree better. Days out, before much observational data exists, model disagreement is normal and expected.

How long do power outages typically last after an ice storm?

It depends on how widespread the damage is. Minor damage might be repaired in hours or a day. Widespread damage can take weeks. In the 2009 ice storm, some areas had power restored in days while others waited two weeks. Utilities now have better mutual aid agreements and faster response capabilities. Most outages are resolved within days, but extensive damage can cause extended outages. Having a backup heat source is critical if you're in an extended outage in winter.

Should I stock up on supplies before the storm or wait to see if it actually arrives?

Stock supplies now, before the storm arrives. By Friday or Saturday, as the storm approaches, stores will be crowded and items will be picked over. Additionally, supplies might be hard to get on the eve of the storm if roads are already becoming hazardous. Having supplies at home means you're prepared regardless of what the storm does, and you've got time to get them without rushing.

What's the difference between a winter weather advisory and a winter storm warning?

An advisory is issued when conditions are possible that could be hazardous, but meteorologists aren't confident enough in the forecast for a warning. An advisory means be prepared. A warning is issued when meteorologists are confident that significant winter weather will occur. A warning means be ready to shelter in place. Warnings are only issued when confidence is high because false warnings damage meteorological credibility.

How accurate are five-day winter storm forecasts?

They're moderately accurate for whether a significant system will affect an area, but timing and precise impacts can be uncertain. The track of a system, the intensity, and the type of precipitation can change as new data comes in. By three days out, forecasts are fairly reliable. By five days out, they're less so. Expect forecasts to change as new information becomes available, and prioritize information from closer to the event.

Conclusion: Prepared and Informed

A significant winter storm is approaching much of the United States. Some regions will experience heavy snow. Some regions might experience crippling freezing rain. Some regions will experience rain. Where exactly gets what remains somewhat uncertain, and that uncertainty is frustrating but normal.

What's not uncertain is that preparation now, before the storm arrives, is time well spent. Stock supplies. Secure your heat source. Know your information sources. Check on vulnerable people. These are simple, straightforward actions that make sense regardless of whether the worst case happens.

What's also clear is that meteorologists are aware of the risks and are issuing forecasts and guidance. The National Weather Service is monitoring the situation. Local meteorologists are tracking model data. Real expertise is being applied to understand this storm.

What's important for you is to stay informed without obsessing, to prepare but not panic, and to help vulnerable people around you if they need help. Winter weather happens. Prepared communities handle it. Unprepared ones suffer. You get to choose which type of community you're in by preparing now.

Don't wait for a worst-case scenario to seem inevitable before you prepare. Preparation is the smart move in any scenario. Do it now, then monitor forecasts as the storm approaches. You'll be in a good position regardless of what happens.

Key Takeaways

- Freezing rain is more dangerous than snow because it adds enormous weight to power lines, causing infrastructure failures and extended outages

- Computer weather models often disagree on storm tracks and precipitation types 5+ days out, making early forecasts uncertain but preparedness still smart

- Regions like the mid-Atlantic and Southeast are historically unprepared for winter weather, making the same storms more catastrophic than in northern states

- The 2021 Texas winter storm killed nearly 250 people and caused $130 billion in damage, demonstrating cascading failures when unprepared regions lose power in freezing conditions

- Preparation before the storm (supplies, heat sources, emergency plans) is the most effective protection; preparation after warnings is too late

Related Articles

- Best Winter Tech for 2026: Must-Have Gear to Beat the Cold [2026]

- Ocean Robots in Category 5 Hurricanes: Oshen's Breakthrough [2025]

- Critical Cybersecurity Threats Exposing Government Operations [2025]

- Why Your Backups Aren't Actually Backups: OT Recovery Reality [2025]

- DDoS Attacks in 2025: How Threats Scale Faster Than Defenses [2025]

- France's La Poste DDoS Attack: What Happened & How to Protect Your Business [2025]

![What We Know About Major Winter Storms Hitting the US [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/what-we-know-about-major-winter-storms-hitting-the-us-2025/image-1-1769024291110.jpg)