Why Your Backups Aren't Actually Backups: Operational Technology Recovery Reality

Last Tuesday, a hospital couldn't access patient records for four hours.

Not because they didn't have backups. They had plenty. Backups on three separate systems, all reporting green. All "successful." But when the incident happened and they tried to restore, the backup from two weeks prior wouldn't boot. Configuration drift had silently corrupted the image. The team discovered this while doctors waited for critical data, not during a scheduled test.

This is the backup illusion that defines modern operational technology environments.

There's a comfortable lie most organizations tell themselves: a completed backup equals a recoverable system. A dashboard turns green, a notification fires off, and everyone assumes the heavy lifting is done. The system is protected. If something breaks, you restore and move on. Simple.

Except it's almost never that simple. Especially not in environments where production never stops, where downtime carries immediate financial or safety consequences, and where the underlying architecture is held together with legacy systems, custom drivers, and institutional knowledge that left with an engineer in 2015.

This article digs into why backup validation matters more than the backup itself, how operational technology environments create unique recovery challenges that traditional IT rarely faces, and what a genuine backup and recovery process actually looks like. Not the dashboard version. The real one.

TL; DR

- A green backup status doesn't guarantee recoverability: Silent corruption, missing drivers, and configuration drift go undetected until you actually try to restore.

- OT environments create extreme recovery complexity: Legacy systems, lack of virtualization, air-gapped networks, and safety certifications make standard recovery procedures impossible.

- Ransomware targets OT specifically because recovery fails: Attackers know operational environments can't afford extended downtime, so they target systems where backup validation hasn't happened.

- Validation requires systematic testing, not just checksums: Hash verification, virtual test restores, dependency mapping, and full recovery drills catch problems that status lights miss.

- The real cost is operational: A failed restore doesn't just delay systems. It cascades through supply chains, production schedules, patient care, and revenue streams for weeks after the initial incident.

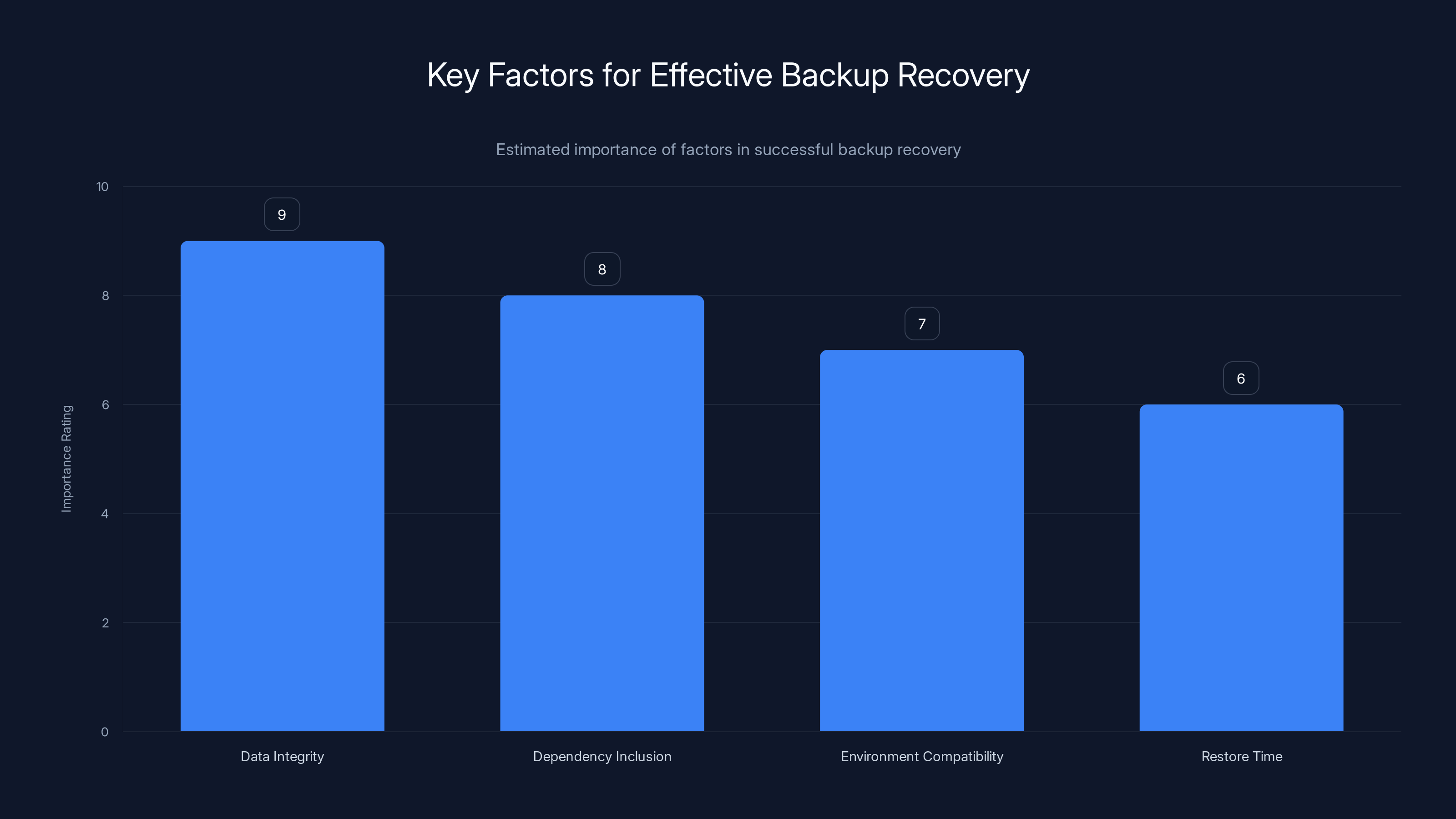

Data integrity is the most critical factor for successful backup recovery, followed by inclusion of dependencies. Estimated data based on common challenges.

The Backup Assumption That's Killing Resilience

There's a foundational misunderstanding embedded in how most organizations approach backup strategy. It goes like this: "We back up our systems regularly. If something goes wrong, we restore from the backup. Problem solved."

That mental model works fine in a lab environment. But in actual operations, especially in operational technology (OT) contexts, it falls apart almost immediately.

The problem isn't the backup process itself. Backups are usually fine. Data gets captured. Files get written. The backup software completes its job and reports success. The real problem is that backup completion and recovery capability are two completely different things, and most organizations treat them as synonymous.

A backup that "succeeds" is one that didn't encounter an obvious error during the capture phase. It copied data. It didn't crash. But success in that context means almost nothing about whether the backup can actually be restored to working condition.

Consider what has to be true for a backup to be truly recoverable:

The data has to be intact. No bit rot. No silent corruption from storage media, network transmission, or the backup software itself. The backup has to contain all the dependencies the system needs to boot and function. Every driver. Every configuration file. Every custom library and firmware image. The backup has to be compatible with the current environment or at least compatible with environments that currently exist. The hardware landscape may have shifted. The OS might have minor version updates that affect driver loading. The backup has to restore within the time window your business can tolerate. A two-hour restore might be theoretically possible but operationally unacceptable if you need systems back online in 30 minutes. All of these conditions have to remain true continuously. A backup that was valid three months ago might not be valid today if the environment drifted.

Most organizations validate maybe one of those conditions. And they validate it once, at backup time.

Then they assume the backup is good forever.

The danger amplifies in OT environments because the underlying systems are already fragile.

Why OT Environments Are Different

Operational technology is the stuff that makes the physical world work. Manufacturing lines. Hospital equipment. Power grids. Transportation systems. Chemical plants. These aren't typical IT infrastructure.

A manufacturing facility's production line might run on a Programmable Logic Controller (PLC) from 2001 that talks to custom software written in a language nobody teaches anymore. The hospital's diagnostic equipment runs Windows XP because the manufacturer never released certified drivers for any newer OS. The distribution center depends on a logistics system that was built in-house in 1997 and nobody has the source code.

These systems exist because they work. They produce value. Removing them or replacing them costs millions and takes months of validation. But they also exist because moving off them is harder than staying on them, which means they accumulate technical debt at a pace that would horrify a traditional IT person.

When you build a backup and recovery strategy for these environments, you're not backing up a clean, standardized architecture. You're backing up inconsistency.

OT systems often can't use standard recovery approaches:

Virtualization is often impossible. Many industrial controllers and embedded systems can't run in a virtual environment. They need bare metal. They need specific hardware. Some need real-time responsiveness that virtualization undermines. You can't spin up a recovery instance of a chemical plant's control system in AWS.

Air-gapped networks prevent cloud backup. For safety or security reasons, many OT systems are isolated from the broader IT network. Data has to be transported physically or through heavily restricted channels. Continuous cloud replication isn't an option.

Patch management is constrained by safety certification. A hospital device might require FDA certification. If you patch the OS, you lose certification and liability protection. So the device stays unpatched indefinitely. A backup that includes that device has to restore it in exactly the same state, down to the patch level, or the restored system isn't valid.

Documentation is often missing. The engineer who configured the system retired. The configuration notes were in someone's email. The wiring diagrams are on a thumb drive that nobody can find. When you restore, you're trying to reconstruct a system from partial information.

Configuration drift is invisible. A system has been in production for five years. During that time, someone installed a driver to work around a hardware issue. Someone else added a custom script to automate a manual process. Someone patched the OS in one specific way. The current state of the system is different from what the documentation says, and backup operators don't even know that.

When you back up this environment, you're capturing a snapshot of fragility. And unless you validate that snapshot regularly against current conditions, you're not actually protected.

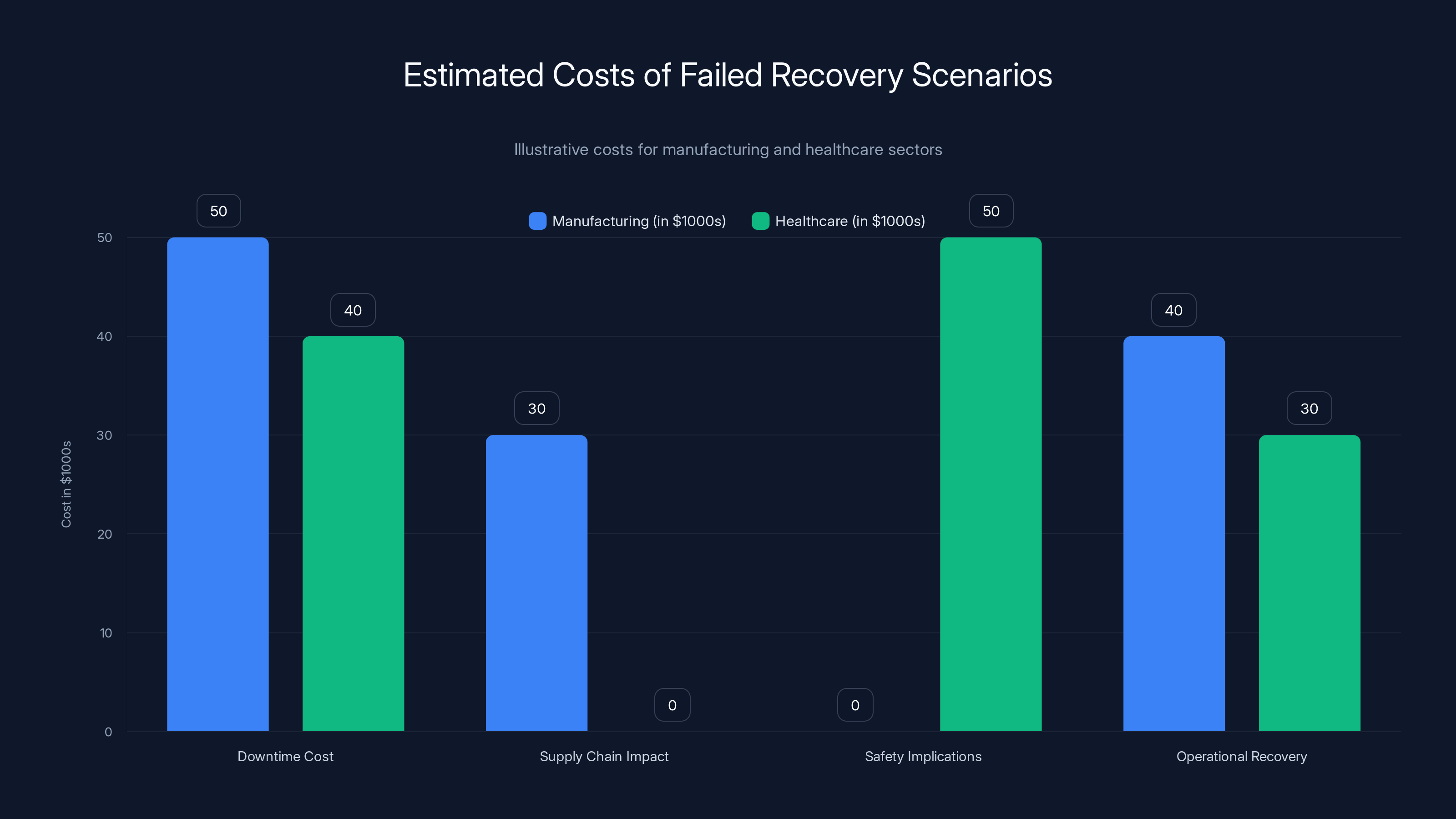

Estimated data shows that both manufacturing and healthcare sectors incur significant costs in different areas due to failed recovery, highlighting the importance of robust recovery plans.

The Real Cost of Failed Recovery

Here's the scenario that most organizations never prepare for: the backup works, the restore fails, and suddenly you're in a race to get systems back online while customers, production lines, or patients are waiting.

A manufacturing company experiences a ransomware attack. The attacker encrypts the production line's control system. Management decides to restore from a backup taken two weeks prior. The IT team initiates the restore. And four hours later, the system boots but doesn't connect to the material handling system. A driver is missing. Nobody remembers what version of the hardware interface was originally installed. The production line stays down. Every hour of downtime costs the company money. Supply chain partners wait for shipments. Customers reschedule. Eventually the system comes back up, but the operational damage compounds for weeks.

That's a failed recovery scenario. And the cost goes far beyond the initial downtime.

Operational Impact

When production stops, problems multiply:

Supply chain cascades. Your facility makes Component X that goes into Product Y that ships to Retailer Z. When your production line goes down, Component X doesn't ship. Retailer Z has to substitute with a different component or delay the product. Your customers experience delays. Your reputation takes a hit. You lose orders that might not come back.

Safety implications. In healthcare, a failed recovery doesn't just delay care. It interrupts it. Patient records aren't available. Diagnostic equipment doesn't work. Clinical staff improvises with paper processes. Risk of error increases. Safety margins erode. The liability exposure is significant.

Operational recovery costs. Once the system is finally back online, you're not just dealing with the incident. You're dealing with backlog. A manufacturing line that was down for 12 hours has a 12-hour production deficit. Staff often goes into overtime to make it up. Shift schedules have to shift. You're paying labor premiums while trying to recover from the incident itself.

Reputation damage. If the incident was caused by ransomware and it becomes public, you're explaining to customers, regulators, and partners that your backups didn't work. That your security posture was weaker than expected. That you weren't ready.

The actual financial impact of a failed recovery in an OT environment often reaches millions of dollars. And most of that cost is borne after the systems come back online, not during the incident itself.

Why Ransomware Targets OT

Cybercriminals aren't stupid. They understand that OT environments can't sustain extended downtime. They know that hospitals need patient data. They know that manufacturing facilities have narrow delivery windows. They know that utilities have regulatory obligations.

So they target OT systems specifically because they know the organization will be under pressure to pay quickly. They know the recovery process will be difficult, which means downtime will be longer, which means the pressure to pay increases.

And if the backup validation process is weak or non-existent, they also know there's a chance the organization won't be able to recover from backups at all, which makes payment the only viable option.

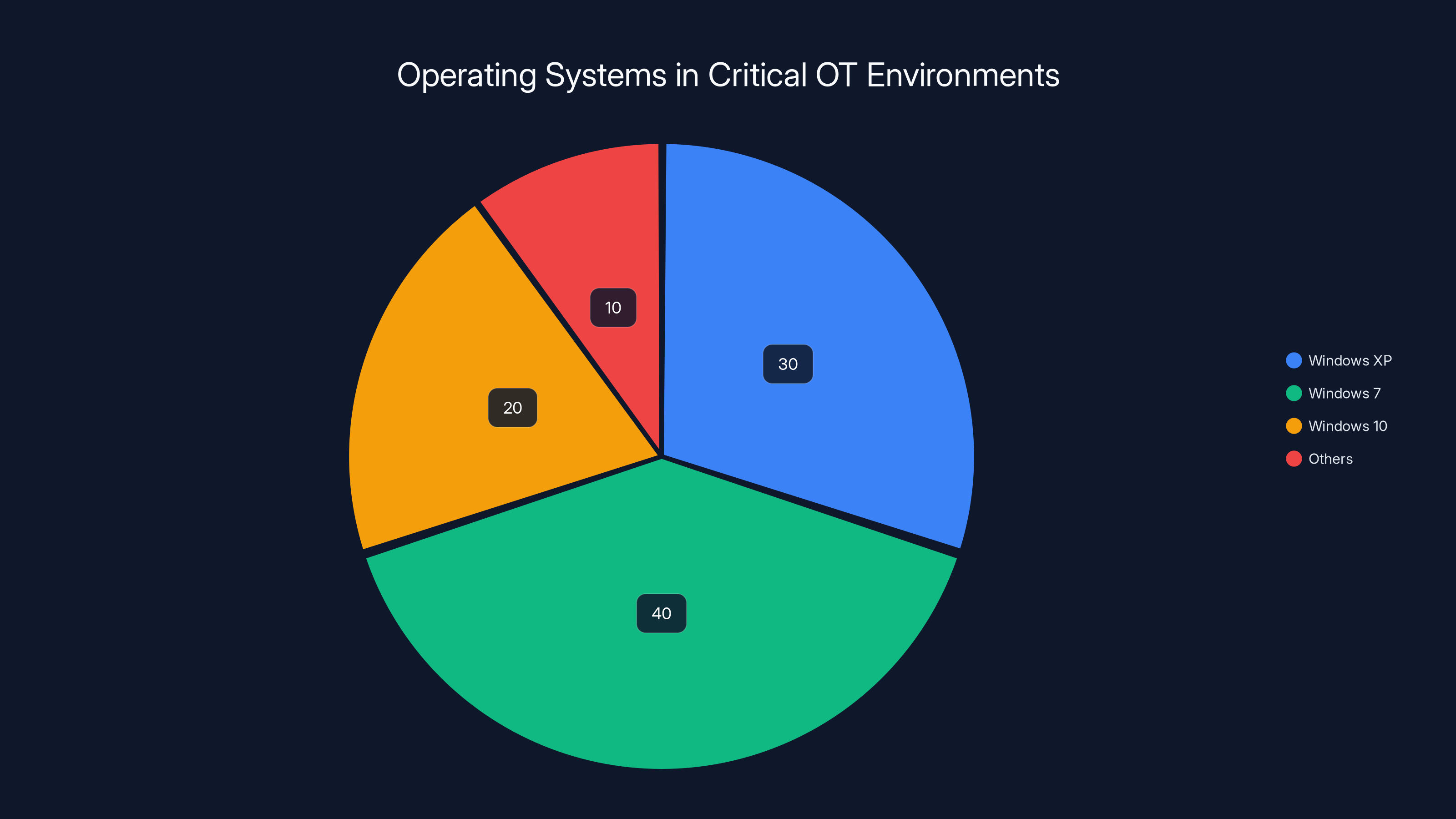

Last year, ransomware attacks exploited unpatched vulnerabilities in approximately one-third of cases. And cybercriminals are four times more likely to target legacy systems (the kind that dominate OT environments) than newer infrastructure. Windows 10 reached end-of-life in October 2025. Many OT environments are still running unsupported operating systems that haven't received security patches in years.

The convergence of IT and OT networking has also widened the attack surface. Increasingly, OT systems are connected to corporate networks for monitoring and management. That connection makes them visible to threat actors who compromise the IT side and then move laterally into operational systems.

Without validated backups, organizations in these scenarios are essentially undefended. Backups become leverage, not protection.

Why OT Recovery Is Never As Simple As It Seems

Theoretically, backup and recovery is straightforward. Capture data. Store it safely. Restore from storage when needed. Resume operations.

In practice, especially in operational technology, recovery is fragile and contingent on dozens of conditions that often aren't understood until something breaks.

The Legacy System Problem

Critical processes still run on operating systems that haven't been supported for over a decade. Windows XP reached end-of-support in 2014, yet many industrial facilities still depend on XP-based controllers. Windows 7 support ended in January 2020, but plenty of manufacturing environments, hospitals, and utilities still run Windows 7 on critical systems.

Why? Because removing these systems costs money. Replacing them requires new hardware, new software, validation, testing, retraining. For a hospital, it also requires regulatory approval. For a manufacturing facility, it requires production downtime to install and validate. For a facility that's been running the same system for 15 years, the institutional knowledge about how it works is held by specific people, and if those people leave, the knowledge leaves with them.

So the systems stay. They get increasingly obsolete. They accumulate custom patches and workarounds. They become fragile.

When you back up Windows XP, you're backing up a snapshot of that fragility. If you restore it to hardware that's just slightly different (a slightly faster CPU, a different network card), the restoration might fail. The drivers might not load correctly. The system might boot but run so slowly that it's operationally unusable.

And there's no fix, because you can't just install a Windows XP driver from 2024. The drivers don't exist. The hardware manufacturers stopped supporting the OS decades ago.

The Missing Documentation Problem

Most OT systems have incomplete or outdated documentation.

A chemical plant's control system was installed in 1998. The original vendor provided documentation. Then the system was modified in 2005 by a contractor. Then it was updated again in 2012 by an internal team. The original documentation is in a filing cabinet somewhere. The 2005 modifications were documented in email. The 2012 update was documented in a Word file that was last edited in 2013 and is now on a network share that nobody uses anymore.

When you try to recover this system, you're restoring a configuration that nobody fully understands in its current form.

If the restore doesn't work, who do you call? The original vendor went out of business. The contractor disappeared. The internal team that made the modifications has turned over completely. You're left trying to debug a system based on partial documentation and institutional memory that nobody has anymore.

The Configuration Drift Problem

Configuration drift is the silent killer of backup strategy.

A system has been in production for five years. During that time:

Someone installed a third-party driver to work around a hardware compatibility issue. Someone else discovered a bug in the OS and installed a specific patch to fix it, but didn't document the patch. Someone added a custom startup script to automate a manual process that used to take an operator 30 minutes every morning. Someone configured a specific network route because of a temporary connectivity issue and never changed it back. Someone modified permissions on a critical folder to work around an access problem.

Each of these changes is small. Each one solved a real problem at the time. But cumulatively, they've transformed the system from what the documentation describes into something different.

Your backup captures the current state. But if that backup is restored to a clean system, or to hardware that's different from the original, all those custom configurations are gone. The driver isn't installed. The patch isn't applied. The startup script doesn't run. The permissions aren't set correctly.

The restored system looks right. It boots. It shows the right version numbers. But it doesn't work the way the current system works because all the undocumented customizations are missing.

Unless you've explicitly tested the restore process and caught these differences, you won't know this until you're in a production incident.

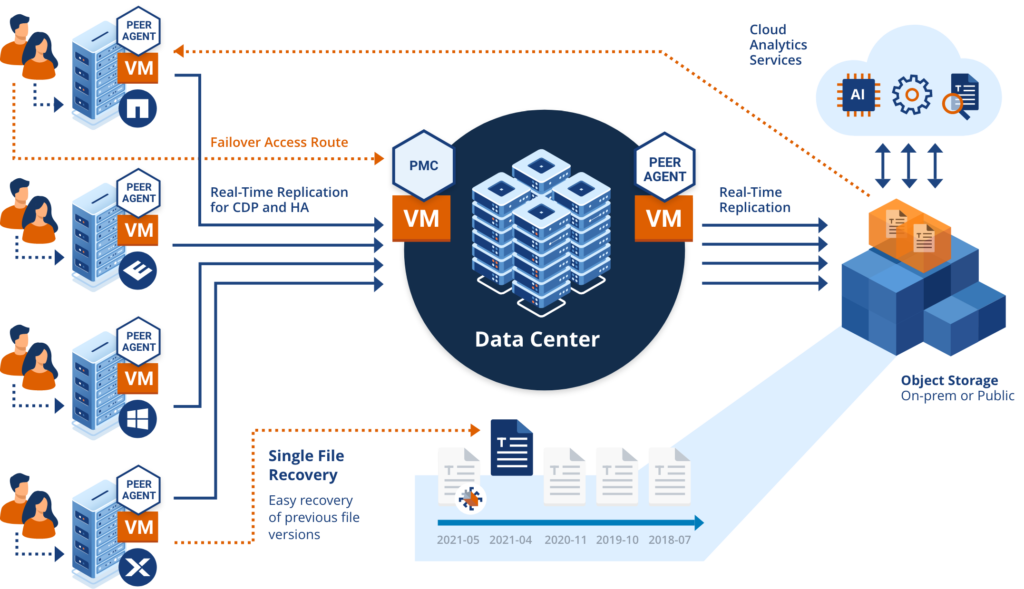

The Dependency Chain Problem

OT systems rarely work in isolation. They depend on other systems, often in ways that aren't obvious until something breaks.

A manufacturing facility's production line might have:

The PLC that controls the machinery itself. The SCADA (Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition) system that monitors the line. The Manufacturing Execution System (MES) that schedules jobs and tracks inventory. The quality control system that checks parts. The packaging system that wraps finished products. The shipping system that tracks outbound orders.

All of these systems talk to each other. If you restore the PLC but not the SCADA system, the PLC might work but operators have no visibility into what's happening. If you restore the MES but not the quality control system, jobs get scheduled but parts don't get validated.

Your backup process might capture all of these systems. But unless you've tested the restore process with all of them together, in the right order, with all the network connections properly configured, you don't actually know if they'll work correctly when restored.

A full recovery requires restoring not just individual systems but the entire dependency chain in the right order, with all the network routes and service connections properly configured.

This is where recovery starts to become complex. A backup is a point-in-time snapshot. A recovery has to recreate not just the snapshot, but the entire ecosystem that makes that snapshot meaningful.

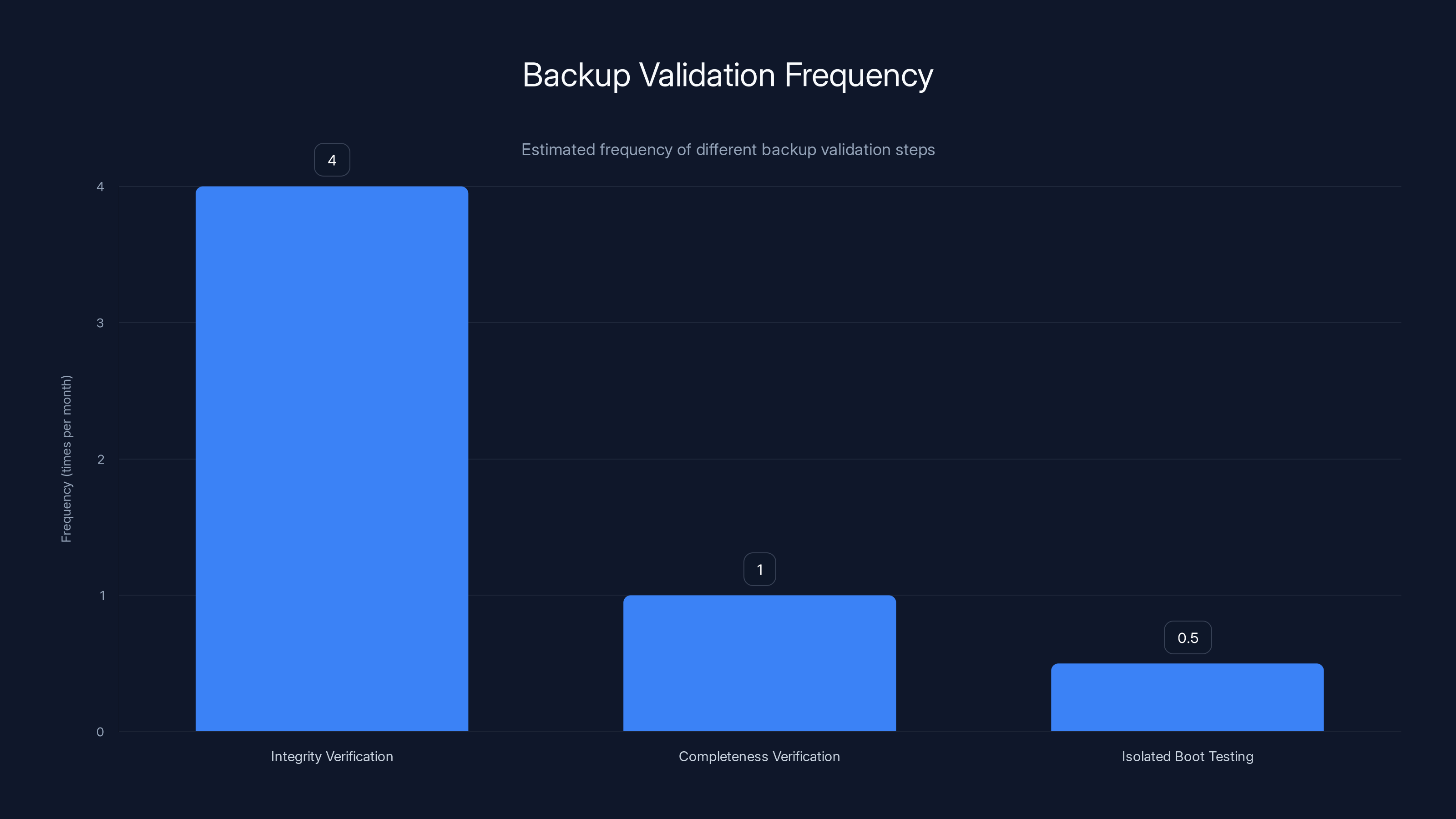

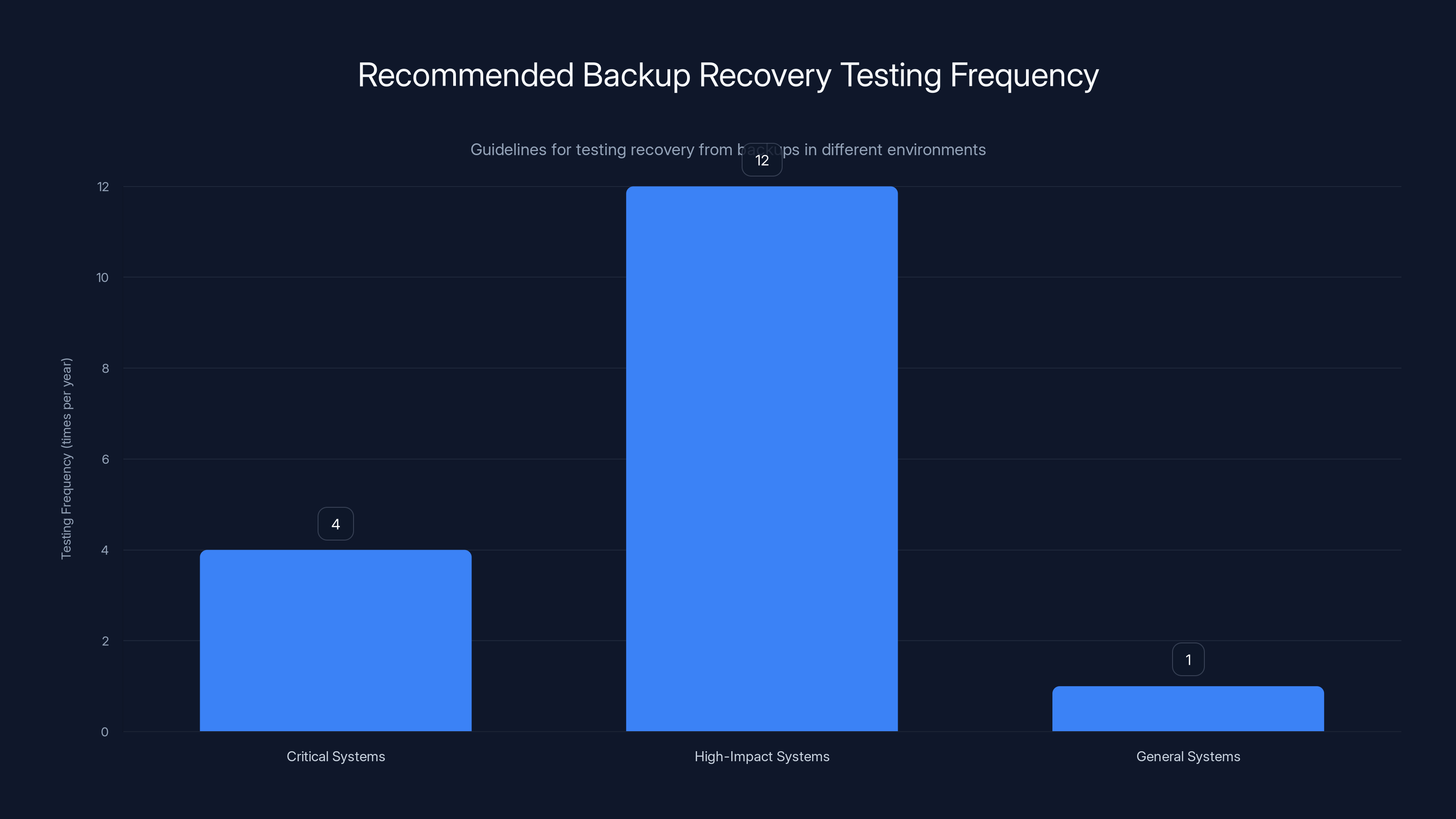

Integrity verification should be conducted weekly, completeness verification monthly, and isolated boot testing bi-monthly. Estimated data based on typical practices.

How Backup Corruption Happens (And Why You Never See It)

There are multiple ways a backup can be silently corrupted without anyone noticing until you try to restore it.

Bit Rot and Silent Data Degradation

Data stored on magnetic media, SSDs, or network storage can slowly degrade without any error signals. A few bits flip here and there. The storage system detects the error, corrects it, and moves on. From the backup software's perspective, everything is fine. But over weeks or months, enough bits have degraded that the backup data is subtly corrupt.

A file gets a few bytes changed. An image file has corruption in a non-critical section that doesn't immediately cause an error. An OS file has a byte modified that causes the file to load but function incorrectly.

When you run the backup software's integrity check (if you even do that), it might show success because the backup software itself works. But the underlying data is corrupt.

You don't discover this until you try to restore, the system boots, and something doesn't work right.

Incomplete Backups

A backup process starts. Files get copied. Then something interrupts it. A network timeout. A power glitch. A storage error. The backup software detects the interruption and reports failure.

But sometimes it doesn't. Sometimes the backup software completes, reports success, and skips over entire sections of data without flagging a problem.

You have a backup that looks complete. It's the right size. It contains what looks like all the right data. But critical files are missing. Device drivers. Configuration files. System libraries.

The backup "succeeded" because the backup software didn't encounter an unrecoverable error. But it's not complete.

Driver and Dependency Incompatibility

You backup a Windows 7 system. The backup includes the current drivers that are loaded. At backup time, everything is working fine.

Six months later, you restore to newer hardware. The hardware is a newer generation, but it's compatible enough that you think the system will work. But when the system boots, Windows tries to load the old drivers. Some of them fail to load. Some load but don't work correctly with the new hardware. The system boots, but it's unstable.

You didn't have a bad backup. You had a backup that wasn't compatible with the recovery environment.

This is especially common when restoring to hardware that's even slightly different from the original. A newer generation of the same component. A different vendor's equivalent hardware. Even a different revision of the same hardware.

Firmware and BIOS Mismatches

A system has a specific version of BIOS and firmware that matches the backup's OS and drivers. When you restore the system to different hardware (or to the same hardware after it's been updated), the firmware versions might not match the OS and drivers.

The system boots. The OS loads. But certain hardware features don't work. Or work incorrectly. Or work in a way that causes subtle data corruption.

You have a restored system that looks functional but has underlying issues that only manifest over time or under specific conditions.

Partial Data Overwrites

A backup is stored on network storage. Another process writes to the same storage location. A partial overwrite happens. Some backup files are corrupted. Some are replaced with wrong data.

Your backup software thinks the backup is still there. It's never verified that the actual backup files are intact. It just checks that backup metadata is present.

You don't discover the corruption until you try to restore and find that critical files are missing or malformed.

Why Backup Corruption Goes Undetected

Most backup software validates that the backup completed without errors. It doesn't validate that the backed-up data is actually intact or recoverable.

Think about what backup validation actually means:

Does the backup metadata exist? Yes. Was data written to the backup location? Yes. Did the process complete without timing out or throwing critical errors? Yes.

Those checks pass. The backup software reports success. A green light appears on the dashboard.

But the software never actually answered the critical question: "If I restore this backup right now, will the restored system work?"

To answer that question, you have to actually try to restore it. In an isolated environment. With enough time to observe whether it boots, whether services start, whether dependencies load, whether the system is stable under load.

That takes time. It takes resources. Most organizations don't do it regularly because it feels unnecessary when the backup software is reporting success.

Until, suddenly, it's very necessary.

The Validation Framework: Moving From Assumption to Confidence

Validating backups isn't a single test. It's a systematic process that starts with quick checks and escalates to full-scale recovery drills.

Here's how to actually validate:

Step 1: Integrity Verification

Start with the basics. Verify that the backup data hasn't been corrupted at the storage level.

Hash verification compares cryptographic hashes of the original data with hashes of the backed-up data. If they match, the data hasn't been modified or corrupted during backup and storage.

Checksum comparisons do similar verification with lighter computational overhead.

Block-level verification reads the actual backup storage and verifies that expected blocks are readable and uncorrupted.

These checks catch silent data degradation and storage-level corruption. They're relatively fast and can be automated.

Run these at least weekly. If any fail, investigate immediately.

Step 2: Backup Completeness Verification

Verify that the backup actually contains all the data it's supposed to contain.

File count verification checks that the number of files in the backup matches the number of files that were supposed to be backed up. This catches incomplete backups where data was skipped.

Directory structure verification ensures that the directory hierarchy is intact. Sometimes backups capture files but lose the directory structure that organizes them.

Critical file verification specifically checks for known critical files. If the OS file is missing, or the database system file is missing, or the configuration files are missing, the backup is incomplete.

These checks catch backups that appeared to complete but actually skipped important data.

Run these at least monthly. Do them more frequently for critical systems.

Step 3: Isolated Boot Testing

Now do something most organizations skip: actually boot from the backup.

Create an isolated virtual environment (or isolated physical hardware if virtualization isn't possible). Restore the backup to that environment. Attempt to boot the system. Observe whether it boots successfully.

Does the OS load? Do core services start? Can you log in? Can you access the file system?

This catches corruption, driver incompatibility, and missing dependencies that don't show up in integrity checks.

Run this quarterly at minimum. For critical systems, run it monthly.

Document what works and what doesn't. If the boot fails or partially fails, investigate why before you consider the backup valid.

Step 4: Application-Level Testing

The system boots. Great. But can it actually do its job?

For a database system, run sample queries. Can you retrieve data? Is the data intact? Can you perform write operations?

For a manufacturing control system, can it establish connections to the devices it's supposed to control? Can it read sensor data? Can it send control commands?

For a healthcare system, can you access patient records? Can you query the system for specific patients or data ranges?

Application-level testing validates that the restored system is functionally equivalent to the original, not just that it boots.

This is where you catch configuration drift, missing drivers, and dependency chain problems.

Run this at least quarterly for systems where recovery time is critical.

Step 5: Dependency Chain Validation

If the system depends on other systems, test the full chain.

Identify all systems that this backup depends on. Create a restore plan that brings them back in dependency order. Restore all of them. Test that they can communicate with each other.

Does the PLC restore and connect to the SCADA system? Does the manufacturing execution system restore and start queuing jobs correctly? Do all the systems form a functional whole?

This is where you validate that recovery isn't just about individual systems, but about the entire operational ecosystem.

Step 6: Load and Stress Testing

The restored system is working. But can it handle production-level load?

Introduce realistic data volumes and request patterns. Run the system at production load for hours. Monitor for stability issues, memory leaks, performance degradation.

Some corruption or compatibility issues only manifest under load. A system might work fine with minimal data but fail when processing the full volume of transactions that it handles in production.

Run load testing quarterly at minimum for critical systems.

Step 7: Recovery Time Measurement

Measure how long it actually takes to restore from backup. Start to finish.

Restore the backup. Bring systems online. Run validation tests. How long did it take? Is it within your Recovery Time Objective (RTO)?

If you have a 4-hour RTO (systems must be operational within 4 hours) but recovery actually takes 6 hours, your backup strategy doesn't meet your operational requirements. The backup looks good, but the recovery process isn't fast enough.

Identify bottlenecks. Can you parallelize recovery of multiple systems? Can you pre-stage hardware? Can you reduce testing time?

RTOs are often theoretical. Measure them in practice.

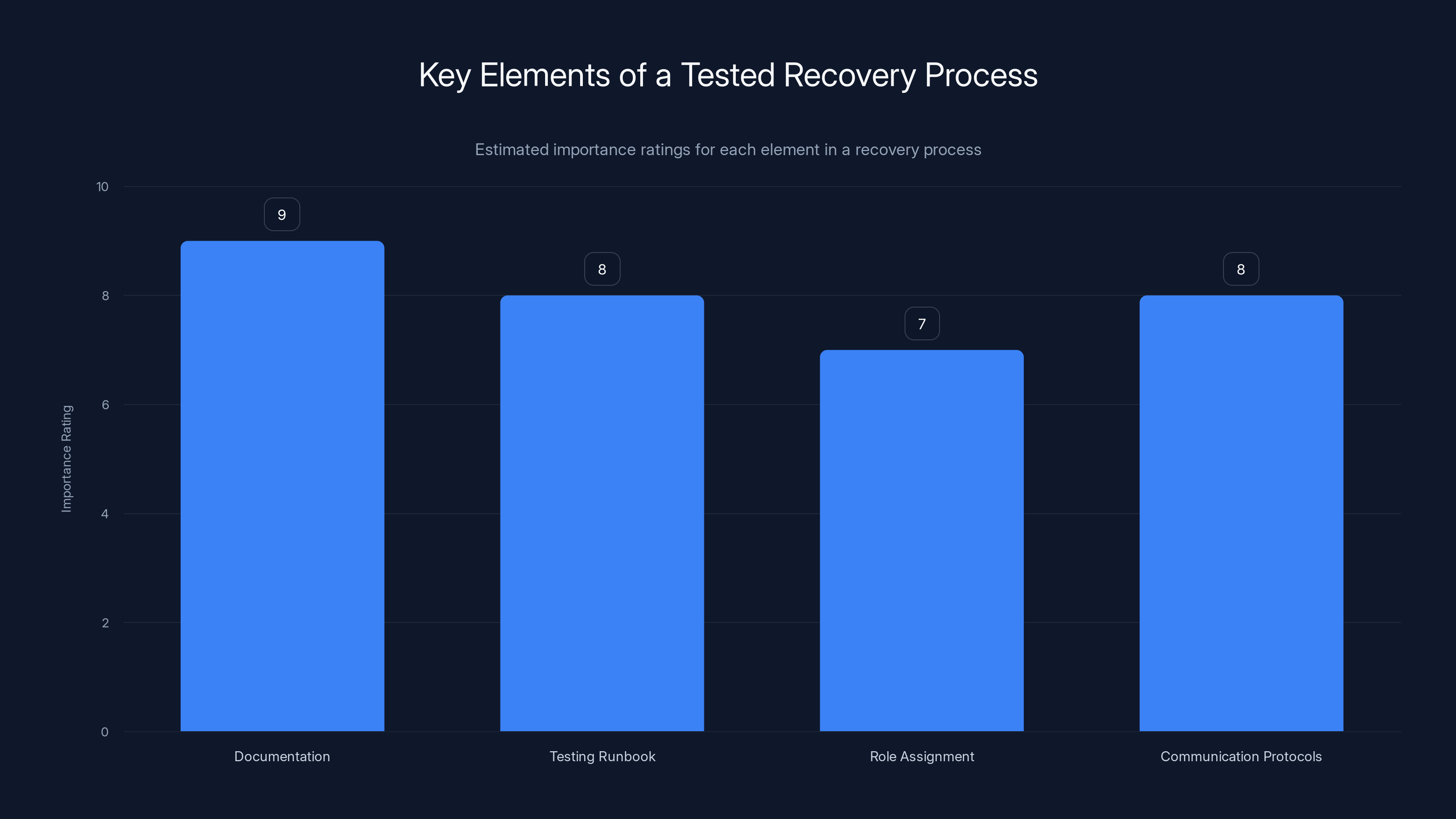

Documentation is rated as the most critical element in a recovery process, followed closely by testing the runbook and establishing communication protocols. Estimated data.

Building a Tested Recovery Process

Validation catches problems. A tested recovery process actually fixes them.

Here's how to build a process that works when you need it:

Document Everything

Create a recovery runbook that includes:

Step-by-step procedures for restoring each system component. Required hardware specifications and configuration. Network topology and connectivity requirements. Service startup order and dependencies. Known issues and workarounds. Contact information for subject matter experts.

The runbook should be detailed enough that a skilled technician unfamiliar with the system can follow it and recover the system successfully.

Update it every time your infrastructure changes. When you patch a system. When you upgrade hardware. When you modify network configuration. When you discover a new issue during recovery testing.

A runbook that's out of date is worse than no runbook at all, because people follow it and hit unexpected issues.

Test the Runbook

Don't just test recovery. Test whether your runbook actually guides recovery correctly.

Give the runbook to someone who isn't familiar with the system. Ask them to follow it and recover from backup. Document every place where the instructions were unclear, incomplete, or wrong. Update the runbook.

Repeat this process. Each iteration makes the runbook clearer and more reliable.

Assign Clear Roles

Define who does what during recovery:

Who authorizes starting recovery? Who performs the actual restore? Who runs validation tests? Who communicates with business stakeholders? Who documents issues as they occur? Who makes decisions about priorities if recovery hits problems?

During an incident, people are stressed, communication breaks down, and critical decisions get made without proper authority. Clear role definitions prevent chaos.

Establish Communication Protocols

Define how information flows during recovery:

How often do recovery leads report status? Where does status information get tracked? Who communicates with business stakeholders? What information is shared, and how frequently?

Clear communication prevents the situation where executives think systems are coming back online while technical teams are still debugging critical issues.

Schedule Regular Drills

Run full recovery drills at least annually. More frequently for critical systems.

A drill means selecting an arbitrary restore point (not the most recent backup), initiating recovery exactly as you would during an actual incident, and running the process to completion. Document how long it takes. Document what breaks. Fix the issues.

Drills are how you discover that the backup is actually unrecoverable. They're how you discover that your runbook has gaps. They're how you discover that your recovery equipment is missing or misconfigured.

They're also how you train your team. Staff turnover means the people who did the last recovery might not be there for the next one. Drills ensure that current staff understand the process.

Plan for Common Failure Modes

Anticipate what will go wrong:

Hardware failures during recovery (backup storage becomes inaccessible, recovery hardware fails). Network connectivity problems preventing systems from communicating. Backup corruption that makes restore impossible. Configuration issues that prevent restored systems from functioning correctly. Resource contention (recovery is consuming so much bandwidth that it's preventing other operations).

For each failure mode, define a response:

If backup storage fails, what's the backup plan? Can you restore from a secondary backup? Can you do a partial recovery? How do you prioritize which systems restore first if full recovery isn't possible?

If the backup is corrupted beyond the point where you can restore it, how do you operate? Can you run in degraded mode? Can you recover from an older backup? What's the data loss impact?

Anticipatory planning prevents the situation where an unexpected problem during recovery causes you to improvise without a strategy.

OT-Specific Recovery Challenges

Operational technology recovery has unique constraints that don't apply to traditional IT.

The Virtualization Problem

Many legacy OT systems can't run in virtual environments. They require specific hardware. Real-time responsiveness that virtualization degrades. Direct hardware access that virtual machines can't provide.

When you back up these systems, you're backing up bare metal systems. Recovery means restoring to equivalent hardware.

But hardware gets discontinued. Vendors stop making specific models. You can't just restore to whatever server hardware you have available. You need the right hardware.

Solution: Maintain a hardware inventory that matches critical systems. Document the specific hardware requirements. Establish relationships with vendors or resellers to ensure you can obtain equivalent hardware if the original hardware fails.

The Certification Problem

Medical devices need FDA certification. Industrial equipment might need ISO compliance. Some systems need safety certification to operate legally.

When you restore a system, it has to be restored to a state that maintains certification. If the OS is patched, you might lose certification. If drivers are updated, certification becomes invalid. If the system is restored to different hardware, the new hardware might not be certified.

A backup of a certified system is only valid if the restored system is also certified. That might mean restoring to identical hardware. It might mean using only approved driver versions. It might mean not applying any OS patches after restore.

Solution: Document all certification requirements explicitly. Get written confirmation from the certification authority about what changes are permissible during restore. Include those constraints in your recovery runbook.

The Custom Software Problem

Many OT systems run custom software written specifically for that facility. Source code might be lost. The original developer might be unavailable. The software might not have been formally tested or documented.

When you restore the system, you're restoring the custom software along with the OS. If the software has a bug that was worked around with a configuration change, that workaround has to be replicated during restore.

If the software has dependencies on specific OS versions or specific driver versions, those dependencies have to be maintained during restore.

Solution: Audit all custom software running on critical OT systems. Document dependencies. Capture source code if possible (with appropriate security controls). Identify the subject matter experts who understand the software. Create comprehensive documentation.

The Air-Gapped Network Problem

Many OT systems are isolated from broader IT networks for security or operational reasons. Backups can't be stored in cloud services. Data can't be continuously replicated.

Backups have to be transported physically. Hard drives carried between locations. USB drives shipped to off-site storage. This creates opportunities for loss, damage, or corruption.

Restore has to work with physically transported backup media. Recovery hardware has to be available at the location where it's needed (can't rely on centralized recovery infrastructure in the cloud).

Solution: Establish a secure process for physical backup transport. Create redundant backup copies stored at multiple physical locations. Maintain recovery hardware at remote sites where critical systems operate. Test recovery procedures with physically transported media regularly.

The Remote Location Problem

Some OT systems operate at remote locations. A remote oil rig. A distributed power station. A facility in a location where technical expertise is limited.

If the remote system fails and needs to be recovered from backup, how do you execute recovery?

You can't have experts physically present at every remote location. Remote hands (engineers who execute instructions over video call) can work for simple procedures but struggle with complex recovery.

Transporting backup media to remote locations is logistically complex. Backup storage that's close to the remote system is vulnerable to the same incidents that damage the primary system.

Solution: Develop procedures that remote hands can execute with minimal technical expertise. Create local backup copies at remote sites with automatic transport of backups to centralized storage. Maintain relationships with local IT support providers at remote sites who can assist with recovery if needed.

Critical systems should be tested quarterly, high-impact systems monthly, and general systems at least annually to ensure reliable recovery.

Building Organizational Resilience Beyond Backups

Backup and recovery is just one piece of resilience. It's necessary but not sufficient.

Understand Your Operational Dependencies

Map every critical process. What systems does it depend on? What data does it need? What services have to be operational?

A manufacturing facility's shipping process depends on the inventory system, the logistics system, the label printing system, the shipping provider's API, the payment processing system, and the email notification system. If any one fails, shipping stops.

Understanding these dependencies helps you prioritize recovery. You restore the inventory system first because shipping doesn't work without it. You restore the logistics system next because it calculates shipping costs. You defer less critical systems.

Establish Realistic Recovery Objectives

RTO (Recovery Time Objective) is the maximum acceptable downtime. RPO (Recovery Point Objective) is the maximum acceptable data loss.

Don't set RTOs based on what you think should be achievable. Set them based on what you've actually measured in recovery drills.

If your RTO is 4 hours but you've never tested recovery and it takes 8 hours when you finally do, your RTO is aspirational, not actual.

Set realistic RTOs based on tested recovery procedures. Then invest in improving recovery procedures if the current RTOs don't meet your operational needs.

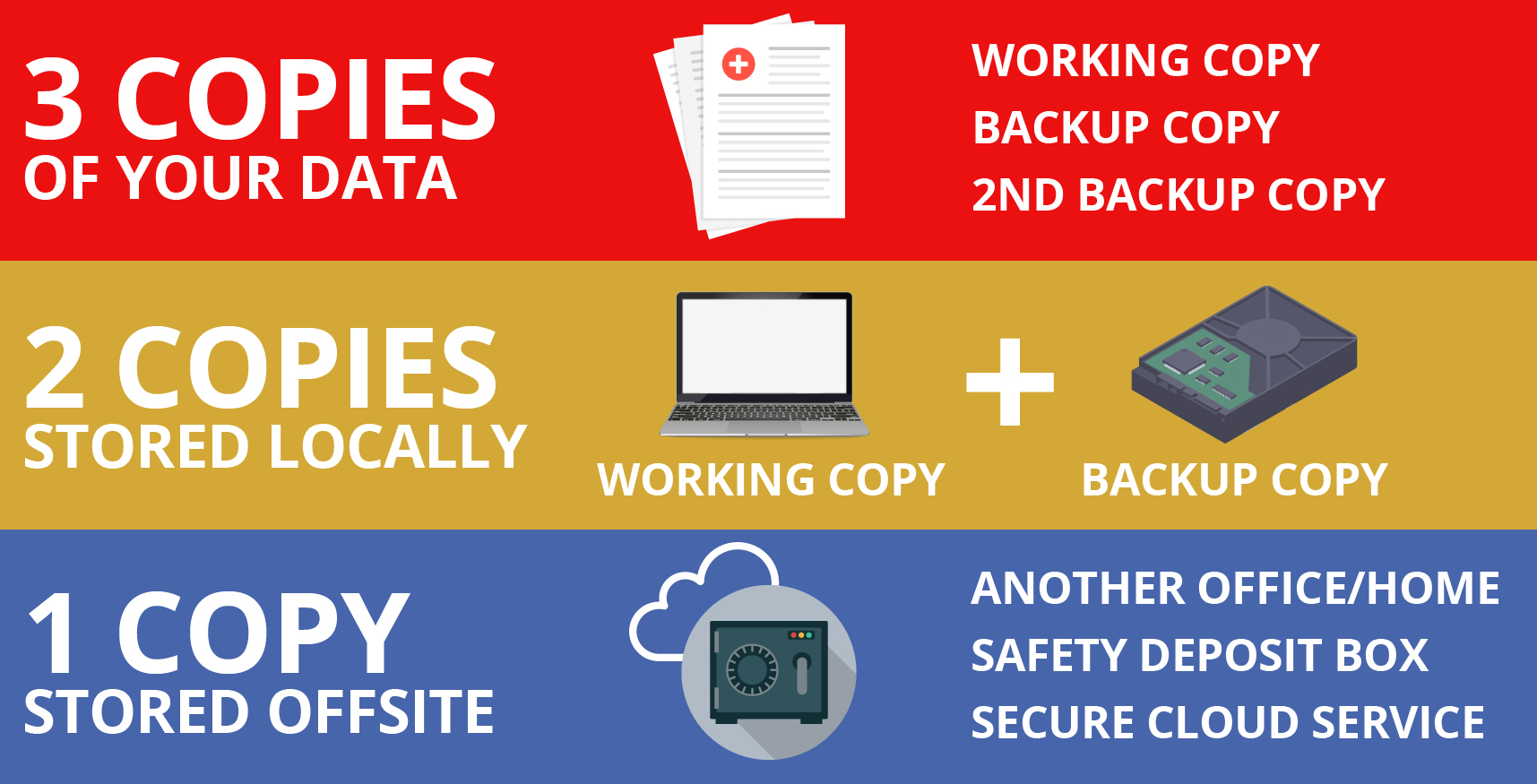

Maintain Multiple Backup Copies

A single backup copy is a single point of failure. Store backup copies at multiple locations. Use multiple backup methods. Copy backups offline regularly.

A common scenario: ransomware encrypts your primary systems and your primary backup storage. You're left with backups that are a month old because that's the most recent offline copy.

Multiple copies reduce this risk. One copy at the primary location (for quick recovery from minor incidents). One copy at a secondary location (for protection against site failures). One copy stored offline (for protection against malware spreading to backup systems).

Build Redundancy Into Critical Systems

Backup and recovery assumes a system will fail. Redundancy prevents a failure from stopping operations.

For critical manufacturing systems, run active-active or active-passive pairs. When the primary fails, the secondary takes over. Recovery happens in the background.

For critical data, replicate continuously to a secondary location. If the primary location becomes inaccessible, applications switch to the secondary.

Redundancy costs money. But for truly critical systems, the cost of downtime far exceeds the cost of redundancy.

Update Backup Processes as Infrastructure Changes

Backup procedures written in 2020 don't work if your infrastructure has changed significantly. New systems. Different storage. Different network topology.

Every infrastructure change requires evaluating whether backup procedures still work.

When you implement new systems, update your backup strategy before the systems go into production. Don't assume your existing backups will capture the new systems correctly.

The Real Test: What Recovery Actually Looks Like

Theory is clean. Reality is messier.

Here's what actual recovery looks like:

Incident Declared

A system goes down. Operations team escalates. Management declares an incident. Recovery team is activated. This should happen within minutes, but often there's delay while people realize something is wrong and contact the right person.

Initial Assessment

What failed? A hardware failure? Malware? Software crash? If it's something fixable without recovery (restart the service, clear a stuck queue), you might not need recovery.

If recovery is necessary, assess the scope. Is one system affected? Multiple systems? The entire facility?

Assessment might take 30 minutes to an hour. During this time, operations are still down.

Authorization

Recover from backup means accepting data loss back to the most recent backup. That's a business decision, not a technical decision. Depending on how long backups are, that might mean losing an hour of data or losing a day of data.

Management has to understand that loss and authorize recovery. This might mean contacting executives or legal teams. Authorization might take time.

Recovery Preparation

Gather recovery hardware. Check that backup storage is accessible. Review the recovery runbook. Identify the person who'll execute each step.

If recovery hardware is co-located with the failed system, you might be able to start in minutes. If recovery hardware is remote or has to be set up, you might spend hours preparing.

Backup Restore

Start the restore from backup. Depending on backup size and storage speed, this might take minutes or hours.

Monitor for errors. If corruption was present but undetected until now, you might discover it during restore. Then you're either restoring from a different backup or accepting that the system won't fully recover.

System Validation

The restore is done. The system boots. Now you need to validate that it actually works.

Run the validation tests that you hopefully did during backup validation.

If you skipped validation before, you're doing it now, under pressure, in an incident situation. Problems that would have been easy to fix during routine testing are now critical blockers.

Issue Resolution

The restore encounters a problem. A driver doesn't load. A service won't start. A dependency chain is broken.

You're now debugging under pressure. The clock is running. Operations are waiting. If you can't fix the problem quickly, you might have to restore from an older backup (incurring more data loss) or accept a longer downtime.

This is where your backup and recovery strategy meets reality.

Operational Recovery

Systems are restored. But operations are still catching up.

If the system was down for 12 hours, there's a 12-hour backlog of work that didn't get processed. Users have to be notified. Customers have to be notified. Supply chain partners have to be notified.

The incident itself is over, but the operational and business impacts continue for days or weeks after systems come back online.

Post-Incident Review

What went wrong? What could have been prevented? What could have been recovered faster?

Without a structured review process, lessons learned in incidents are often forgotten and the same mistakes happen again.

Conduct a formal review. Update procedures. Update runbooks. Schedule follow-up recovery tests based on what you learned.

Estimated data shows that a significant portion of critical OT environments still rely on unsupported operating systems like Windows XP (30%) and Windows 7 (40%), highlighting the challenges in modernizing these systems.

Building Trust in Your Backup Strategy

At the end, backup and recovery is fundamentally about trust.

Do you trust that your backups will work when you need them? Not trust in the sense of faith or assumption. Trust in the sense of having validated that the backup and recovery process actually works, repeatedly, under conditions that approximate a real incident.

Trust Requires Validation

You can't trust a backup that you've never tested. A green status light on a dashboard is not validation. A backup that you restored once, two years ago, is not current validation.

Trust requires:

Regular automated integrity checks that you review and act on. Quarterly restore tests that you document and analyze. Annual full recovery drills that exercise the entire process. Updates to recovery procedures whenever infrastructure changes. Post-incident reviews that identify what you learned.

This takes time and resources. But it's the cost of actually being protected.

Trust Is Fragile

One successful recovery drill doesn't mean you can relax. Threats and infrastructure change continuously. A recovery procedure that works today might not work in six months if systems have changed or if staff has turned over.

Trust requires continuous maintenance. Regular drills. Updated documentation. Ongoing technical investment.

The alternative is the situation that most organizations are in: assuming they're protected while not actually knowing whether they are.

The Industry Is Starting to Wake Up

There's a growing recognition that backup validation matters. Regulatory frameworks are starting to require proof of recovery capability, not just backup completion. Insurance companies are starting to ask questions about how backups are validated. Industry standards are starting to formalize validation requirements.

The organizations that build proper backup and recovery processes now will have a competitive advantage. They'll be protected when incidents happen. They'll recover faster. They'll have lower insurance costs.

The organizations that assume backups are sufficient, without validation, are one incident away from discovering that assumption was wrong.

FAQ

What is the difference between a successful backup and a recoverable backup?

A successful backup is one that completed without errors during the backup process. The backup software started, copied data, and finished without crashing or throwing critical errors. A recoverable backup is one that you can actually restore to a working system. It's a much higher bar. A recoverable backup requires that the data is intact, that all dependencies are captured, that the backup is compatible with recovery environments, and that you've actually tested the restore process and confirmed it works.

How often should I test recovery from backup?

For critical systems in operational technology environments, you should perform at least quarterly restore testing. This means selecting a backup, initiating a full restore to an isolated environment, and validating that the restored system works correctly. For systems where downtime has severe consequences, monthly testing is appropriate. At minimum, you should conduct an annual full recovery drill that exercises the entire recovery process from start to finish. If you're not testing quarterly at minimum, you're essentially guessing that recovery will work when you need it.

Why is configuration drift dangerous for backup and recovery?

Configuration drift occurs when a system accumulates undocumented changes over time. A driver is installed. A patch is applied. A startup script is added. A network route is configured. Each change solves a real problem, but collectively they transform the system from what the documentation describes into something different. When you restore a backup that includes configuration drift, you're restoring all those undocumented changes. If you restore to different hardware or a clean environment, the changes might not apply correctly, and the restored system won't function like the original. Unless you've explicitly tested recovery and caught these differences, you'll only discover them during an actual incident.

What should a recovery runbook include?

A recovery runbook should include step-by-step procedures for restoring each critical system, the specific hardware requirements and configuration needed, network topology and connectivity information, the order in which systems need to be restored and why, service startup sequences and their dependencies, known issues and workarounds discovered during recovery testing, contact information for subject matter experts who understand critical systems, and estimated time for each recovery step. The runbook should be detailed enough that someone unfamiliar with the system can follow it and execute a recovery successfully. It should be updated every time your infrastructure changes or every time you discover a new issue during recovery testing.

How do I know if my Recovery Time Objective is realistic?

Your Recovery Time Objective is realistic only if you've actually tested recovery and confirmed that you can consistently achieve it. If your RTO is 4 hours, you should have measured actual recovery time in multiple drills and confirmed it stays within 4 hours. If actual recovery consistently takes 6 hours, then your real RTO is 6 hours, regardless of what your policy states. Many organizations have aspirational RTOs that don't match reality. Don't set RTOs based on what you wish were achievable. Set them based on what you've measured, then invest in improving the process if your actual RTOs don't meet your operational needs.

What's the difference between backup and disaster recovery?

Backup is the process of capturing data regularly so you can restore from it if needed. Disaster recovery is the broader process of getting systems and data back to operational status after a major incident. Backup and recovery might work smoothly for small, isolated problems. But disaster recovery has to address larger challenges like recovering multiple interdependent systems, dealing with compromised infrastructure, managing stakeholder communication, and handling the operational backlog that accumulates while systems are down. A good backup is a foundation for disaster recovery, but it's not the same thing. Disaster recovery requires planning, process, training, and organization-wide coordination.

Can I rely on cloud backups for operational technology systems?

Cloud backups work well for IT systems but are often not suitable for critical OT systems. Many OT environments are air-gapped from external networks for security or operational reasons, which makes cloud backup logistically complex. Many OT systems can't virtualize or run in cloud environments, so restoring to cloud infrastructure isn't an option. Some OT systems have real-time requirements that cloud latency undermines. That said, cloud can be valuable as an off-site backup copy for protection against site-level disasters. The best approach is often local backup storage for quick recovery and cloud backup for long-term off-site protection. Evaluate cloud backup based on your specific OT environment and constraints, not based on what works for typical IT infrastructure.

How do I validate backup integrity without restoring the entire system?

Start with hash verification or checksum comparisons, which confirm the backed-up data matches the original data and hasn't been corrupted. These are fast and can be automated. Then run file count and directory structure verification to ensure the backup is complete. Then do periodic isolated boot tests, restoring to a virtual environment to confirm the system boots and core services start. These steps catch many common problems (corruption, incomplete backups, driver issues) without requiring a full production recovery. But they're not sufficient on their own. You still need periodic full recovery tests to validate that the entire system works correctly, including all dependencies and under production-level load.

Conclusion: From Assumption to Assurance

The comfortable lie is that a completed backup means you're protected. A green light on a dashboard. A notification that the process succeeded. And then moving on with the assumption that if something breaks, recovery will work.

The reality is harder. Backup success and recovery capability are different things. A backup that looks fine might be corrupted. A backup might restore to a clean system but not to the complex, fragile infrastructure where it originally came from. A recovery procedure might work in theory but hit unexpected obstacles when executed under pressure in an actual incident.

Operational technology environments amplify all of these risks. Legacy systems. Limited virtualization. Complex dependencies. Safety and certification constraints. Air-gapped networks. Remote locations. These environments make recovery harder and the consequences of failed recovery more severe.

But the path to genuine resilience is clear. Stop assuming backups work. Start validating that they actually do. Test recovery regularly. Update procedures when infrastructure changes. Train staff. Document lessons learned. Build confidence not through faith but through repeated evidence that recovery actually works.

This requires investment. Time. Resources. Discipline. It's tempting to skip it, especially when the backup software keeps reporting success and incidents don't happen.

Until one does.

The organizations that invest in proper backup validation now will be the ones that actually recover when incidents happen. The ones that maintain operations. The ones that avoid the cascading financial and operational damage that failed recovery creates.

The ones that can trust their backups because they've validated them.

Stop assuming. Start validating. Your resilience depends on it.

Key Takeaways

- Backup completion and recovery capability are fundamentally different—a green status light doesn't prove a system can actually be recovered

- OT environments face unique recovery challenges: legacy systems, virtualization constraints, certification requirements, air-gapped networks, and complex dependencies

- Silent corruption, missing drivers, configuration drift, and incomplete backups often go undetected until an actual recovery attempt fails

- Systematic validation requires seven steps: integrity verification, completeness checks, isolated boot testing, application testing, dependency chain validation, load testing, and time measurement

- Recovery procedures must be documented, tested regularly, and updated whenever infrastructure changes; assumptions about recovery don't survive contact with reality

- Ransomware groups specifically target OT systems because they know recovery is difficult and downtime is intolerable, making payment more likely

- Multiple backup copies at different locations, redundant systems for critical infrastructure, and continuous operational monitoring provide defense-in-depth

Related Articles

- France's La Poste DDoS Attack: What Happened & How to Protect Your Business [2025]

- DDoS Attacks in 2025: How Threats Scale Faster Than Defenses [2025]

- GPS Jamming: The Vulnerability Threatening Modern Infrastructure [2025]

- LTO Tape Storage: Why 40TB Cartridges Matter for Enterprise Data [2025]

- NIST Atomic Time Server Outage: How America's Internet Lost Precision [2025]

![Why Your Backups Aren't Actually Backups: OT Recovery Reality [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/why-your-backups-aren-t-actually-backups-ot-recovery-reality/image-1-1768405177912.jpg)