Understanding the Massive Price Jump for Jumbo TVs

You're standing in an electronics store, looking at TVs. A 115-inch screen catches your eye. Then you see the 130-inch model right next door. It's only 27% larger. But the price tag? It's 50% higher. That's not a typo. That's not a markup strategy. That's the actual cost of manufacturing bigger screens.

This isn't just television pricing. It's a window into how manufacturing complexity scales exponentially rather than linearly. When you add just a few more inches to a display, you're not just making a slightly bigger panel. You're entering an entirely different engineering problem set.

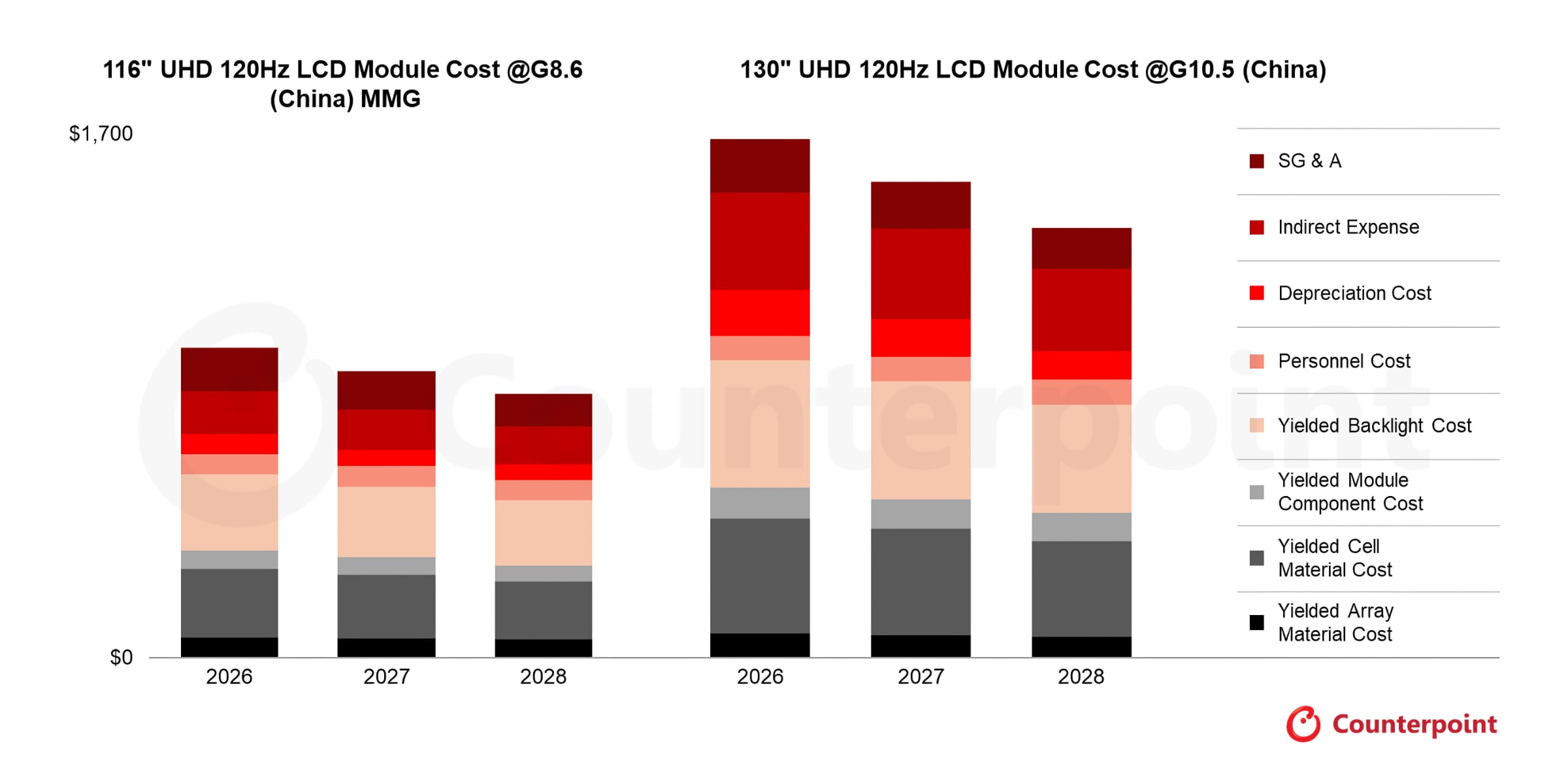

Recent manufacturing analysis shows the stark reality: producing ultra-large TV panels requires completely different production infrastructure, material sourcing, and quality control processes. The leap from 115 inches to 130 inches pushes manufacturers into territory where yield rates drop, defect rates climb, and the technological requirements spike dramatically.

For consumers, this means understanding why you're really paying that premium. It's not arbitrary. It's rooted in hard physics and manufacturing constraints that hit suddenly once you cross certain size thresholds. The closer you look at this gap, the more sense the pricing makes. And the less sense it makes to buy a 130-inch TV right now.

Let's break down what's actually happening behind those price tags.

The Core Physics Problem: Screen Size Doesn't Scale Linearly

Here's the fundamental issue: screen real estate scales with area, not height or width. When you go from 115 inches to 130 inches, you're talking about screen area increasing by roughly 27%. But manufacturing challenges? They increase much faster.

Think about it mathematically. A 115-inch TV (measured diagonally) has an aspect ratio of typically 16:9. That gives you an actual viewable area. When you jump to 130 inches, you're not just adding a border. You're adding surface area on all sides. The pixel count increases. The backlighting zones multiply. The structural support needed for the panel gets more complex.

Panel rigidity becomes critical at these sizes. A 115-inch screen can flex slightly without viewers noticing. At 130 inches, any flex becomes visible. Manufacturers need thicker glass substrates, better internal bracing, more support columns behind the panel. All of that adds weight, complexity, and cost.

The glass itself becomes harder to source. Ultra-large sheets of high-quality glass suitable for display manufacturing are produced by only a handful of suppliers worldwide. Demand spikes, supply tightens, and costs rise. Glass defects that would be irrelevant on smaller screens become critical issues on 130-inch displays. A single dust particle in the wrong spot ruins the entire panel.

Quality control becomes exponentially more difficult. Inspecting a 115-inch panel for dead pixels, color uniformity, and panel defects is manageable. Inspecting a 130-inch panel? The surface area is so large that statistically, you're much more likely to find defects. Manufacturers might reject 30-40% of 130-inch panels at final inspection, while 115-inch rejection rates hover around 12-15%.

That's not hyperbole. That's what yield rates actually look like at these sizes.

Transportation and logistics multiply the cost burden. A 115-inch TV can ship in standard packaging with manageable logistics. A 130-inch panel requires specialized, reinforced packaging. It needs dedicated logistics channels. Damage rates increase. Replacement costs skyrocket. Manufacturers build all that risk into the final price.

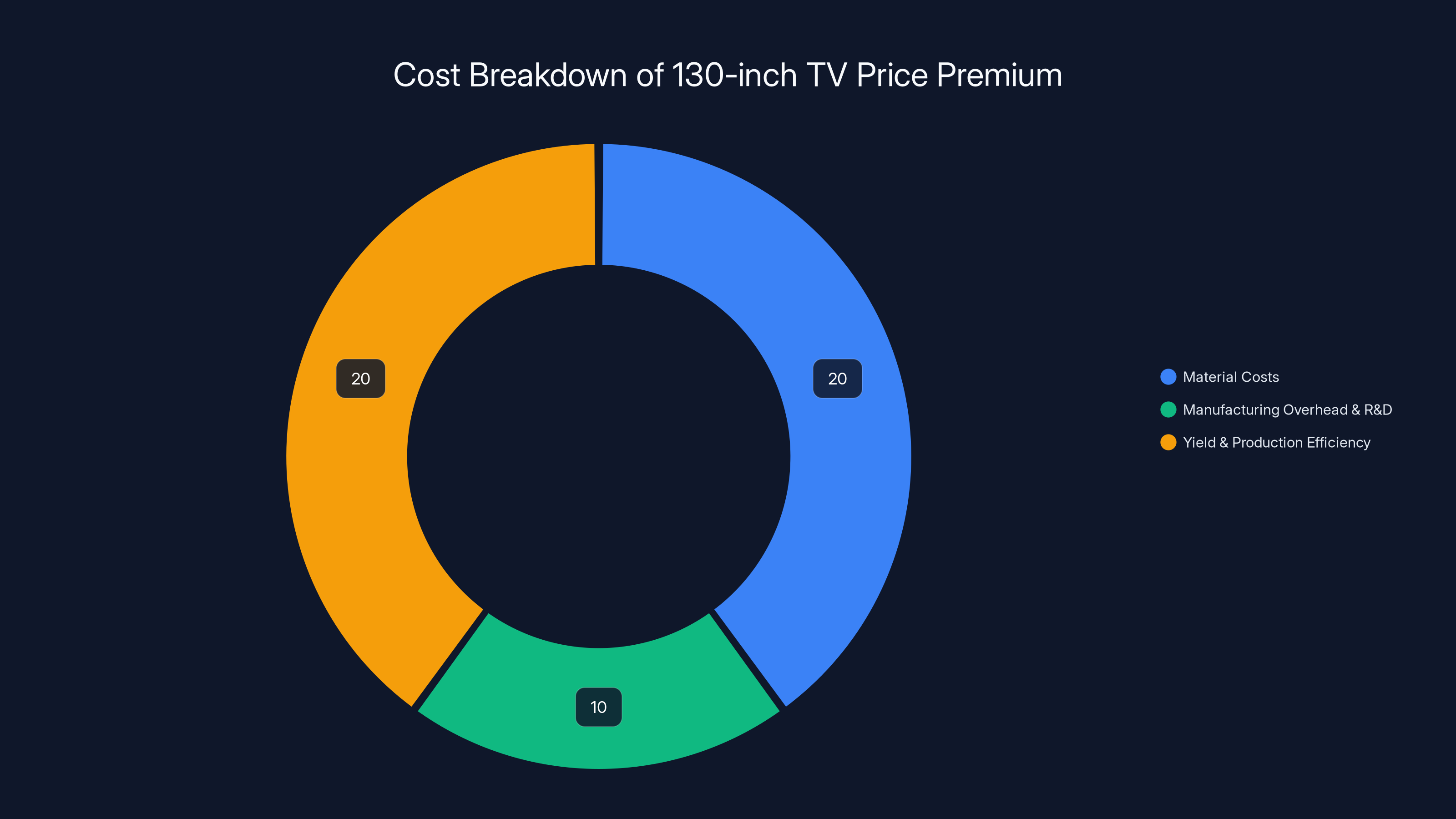

The 50% price premium for 130-inch TVs is primarily driven by material costs (20%) and yield/production efficiency challenges (20%), with a smaller portion (10%) due to manufacturing overhead and R&D.

Manufacturing Infrastructure: The Hidden Cost Multiplier

You don't just scale up production lines. You rebuild them entirely.

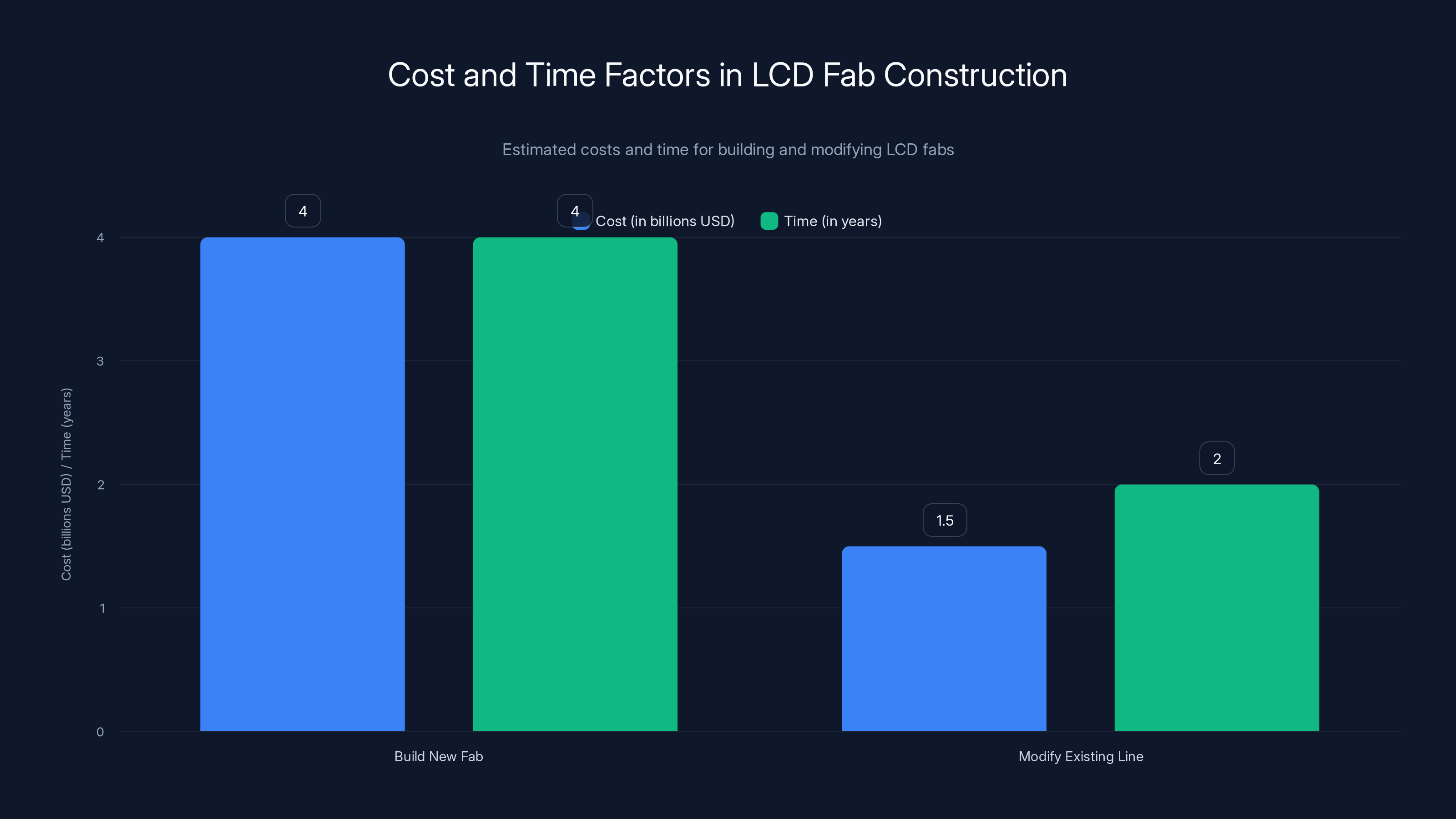

TV panel manufacturing happens in massive facilities called fabs. These aren't small operations. A typical LCD fab costs $3-5 billion to build and can take 3-5 years to construct. Once built, the production line is optimized for specific panel sizes. The conveyor systems, the liquid crystal deposition equipment, the photolithography systems, everything is calibrated for panels up to a certain size.

Want to add 130-inch production? You either modify existing lines (expensive, risky, production downtime) or build dedicated production capacity (billions in capital). Most manufacturers choose to modify existing lines, which creates bottlenecks and reduces overall throughput.

The handling equipment changes too. Robotic arms that move 115-inch panels aren't strong enough for 130-inch panels. The vacuum grip systems that hold glass during processing need redesign. The conveyor speeds must slow down to prevent shock damage to larger, heavier panels. When you slow down conveyor speeds, you reduce daily output per production line by 20-30%.

Thermal processing becomes more difficult. Large glass panels heat and cool unevenly. Temperature gradients across a 130-inch panel are more pronounced than on 115-inch panels. This can cause stress fractures, warping, and optical distortions. Manufacturers need to invest in more sophisticated thermal control systems, heating elements, and cooling channels within the panel itself.

Quality assurance equipment scales non-linearly. Testing systems for 115-inch panels won't fit or function with 130-inch panels. Manufacturers need entirely new optical inspection systems, completely new software to analyze panel data, and new reference standards. These systems often cost $50-100 million each.

Staffing changes too. Training production line workers to handle ultra-large panels takes longer. The safety protocols are different. Injury rates on large panel lines are higher, creating additional insurance and liability costs.

Supply chain complexity increases dramatically. A 115-inch panel requires sourcing components from multiple suppliers in different regions. A 130-inch panel needs those components sourced from fewer suppliers (because fewer can actually produce at that scale), creating dependency risks and pricing power for suppliers.

Building a new LCD fab can cost $3-5 billion and take 3-5 years, while modifying existing lines is cheaper but still costly and time-consuming. Estimated data.

Material Costs: More Than Just More Glass

It's not just about buying bigger sheets of glass. The materials themselves change at this scale.

Glass composition matters enormously for large panels. Standard soda-lime glass used in smaller displays can have micro-stresses that are invisible at 100 inches but become critical at 130 inches. Manufacturers switch to higher-purity glass formulations with tighter tolerances. That glass costs 2-3 times more per unit.

The liquid crystal material inside the panel requires different specifications for large displays. Temperature stability becomes crucial. Light transmission needs to be more uniform. The nematic liquid crystals used must have higher purity and better temperature coefficients. Bulk material costs increase, and manufacturers must buy from premium suppliers with proven track records on large-scale production.

Backlight systems get exponentially more expensive. A 115-inch LED backlight might use 100-120 individual LED zones. A 130-inch display typically uses 150-180 zones for comparable picture quality. But zones aren't the only change. The LEDs themselves need to be higher quality and more precisely calibrated. You can't use standard binned LEDs from cheaper suppliers. Manufacturers specify ultra-narrow color temperature ranges and brightness variations.

Diffusion films, optical films, and light-guiding films all scale in cost but not linearly. The materials are the same, but manufacturing yield drops for larger film sizes. A film manufacturing line produces sheets of material. Larger displays require larger sheet sizes. The waste per sheet increases. The defect rate per sheet increases. That waste is absorbed into material costs.

Fluorescent backlight materials (still used in some premium models) require rare earth elements. Sourcing rare earths at scale is already difficult. Sourcing them for 130-inch production runs, which are much smaller than 115-inch runs, creates a supply disadvantage.

The polarizing films and alignment layers applied to the glass substrate are literally different products for different sized panels. The chemical composition can be identical, but the application process changes. Larger panels require modified application techniques and more quality control checkpoints, adding cost.

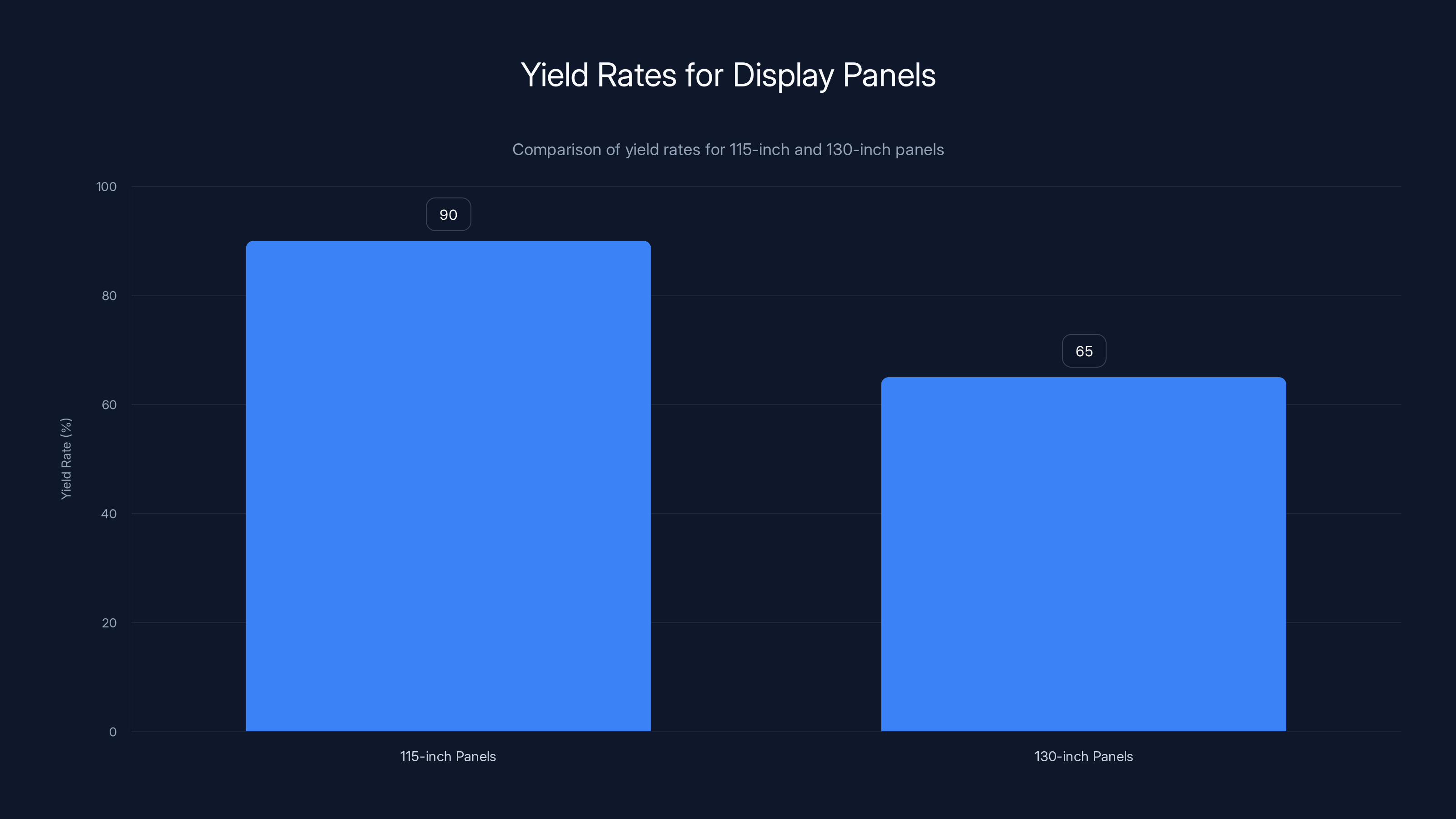

Yield Rates: The Silent Cost Driver

This is where the math gets brutal for manufacturers, and costs get brutal for consumers.

Yield rate means the percentage of panels that successfully pass final quality inspection. If a manufacturer produces 100 panels and 90 pass inspection, that's a 90% yield rate. The other 10 become recycled material or go into refurbished channels at steep discounts.

For 115-inch panels, manufacturers have typically achieved yield rates of 85-92%, depending on how aggressive they're being with quality standards. That's actually not bad for advanced display manufacturing. There's some slack in the system.

For 130-inch panels? Industry reports suggest yield rates are currently 60-72%. That's a difference of 15-25 percentage points.

Let's do the math. To deliver 100 units of a 115-inch panel with 90% yield, you need to manufacture about 111 panels. At 65% yield for 130-inch panels, you need to manufacture about 154 panels to deliver 100 units.

So the per-unit manufacturing cost for a rejected 130-inch panel still gets built into the pricing of every successful panel. Manufacturers absorb this through slightly higher component costs and per-unit allocation of manufacturing overhead.

What kills yield rates for larger displays? Multiple factors compound:

Dust and particle contamination. Larger panel surface area means more exposure risk during manufacturing. A single dust particle is unforgivable at 130 inches.

Thermal stress fractures. Glass cracks during heating and cooling cycles due to uneven temperature distribution.

Optical imperfections. Dead pixel areas, color banding, and brightness non-uniformity become statistically more likely with more pixels and more backlighting zones.

Structural defects. Warping, bowing, or flexing in the panel substrate that exceeds specification.

Electrical failures. Thin-film transistor defects that short out regions of the display.

Color uniformity issues. The color temperature and brightness vary across the panel more than the specification allows.

As manufacturers gain experience with 130-inch production, yield rates will improve. Samsung, LG, and TCL are all investing heavily here. Expect yield rates to climb toward 80-85% within 18-24 months. When that happens, costs will drop substantially.

The logistical complexity and costs for 130-inch TVs are significantly higher than for 115-inch TVs, particularly in packaging, shipping, and return processes. Estimated data.

The Production Line Economics Problem

Manufacturers don't just add a 130-inch option. They have to make business decisions about production allocation.

A typical TV panel fab operates at fixed capacity. It can produce, let's say, 50,000 panels monthly across all sizes. Historically, this capacity was allocated roughly: 30,000 units of 55-65 inch, 12,000 units of 75-85 inch, and 8,000 units of 95-115 inch.

Now add 130-inch demand. There's not new capacity. Manufacturers have to reallocate. Maybe they drop 55-inch production (lower margins anyway) and shift capacity to 130-inch. But here's the thing: 130-inch lines run slower. The conveyor moves slower. The drying time is longer. The testing time per unit is longer.

That 8,000-unit 115-inch production run at high speeds might become a 4,000-unit 130-inch production run at optimized speeds. You've cut your output per line in half.

Manufacturing overhead doesn't drop by half. Your facility cost, your labor force, your utilities, your quality control infrastructure—all of that's mostly fixed. So you're spreading that fixed overhead across half the unit output. Suddenly, per-unit overhead allocation doubles.

This is the hidden math of introducing premium, larger sizes. Early adopters pay for the infrastructure investment.

Manufacturers also have to consider component availability. If your production lines run slower, they need components at lower volumes. But suppliers optimize for volume discounts. A supplier giving you 1,000 LED backlight units per week might charge significantly more per unit than they would for 5,000 units per week. Component suppliers benefit from volume commitments, and 130-inch production doesn't provide that.

Research and Development: Investing in Failure

Before a single production unit ships, manufacturers spend millions developing 130-inch capability.

R&D budgets for new panel sizes are substantial. Companies employ teams of engineers specifically to solve the problems inherent to larger sizes. They build prototype production lines. They run test batches. They fail. A lot.

Testing protocols become more complex. Quality assurance engineers need to develop new testing standards specifically for 130-inch panels. This includes optical testing systems, thermal testing, electrical testing, and longevity testing. Some of this equipment needs to be custom-built because no supplier makes standard testing equipment for panels this large.

Failure analysis becomes elaborate. When a 130-inch panel fails, engineers need to determine why. Was it a thermal stress crack? A materials defect? A processing issue? This analysis takes time and specialized expertise. Each failure teaches something, but you're paying for those lessons.

Software development for production control systems needs to be retooled. The algorithms that control heating, drying, and chemical deposition processes on 115-inch lines don't directly translate to 130-inch lines. Engineers customize them, test them, debug them, and validate them.

Personnel training requires investment. Your experienced production line managers know 115-inch panels intimately. They've optimized every step. 130-inch panels are new territory. They need retraining, and they'll still make learning-curve mistakes early on.

Safety system upgrades are required. Moving 130-inch panels requires different safety protocols. New interlocks. New warning systems. OSHA compliance certification. All of this costs money upfront.

This R&D spending is real money. It's not recovered until reasonable production volumes are achieved. Early customers pay for this through higher unit costs.

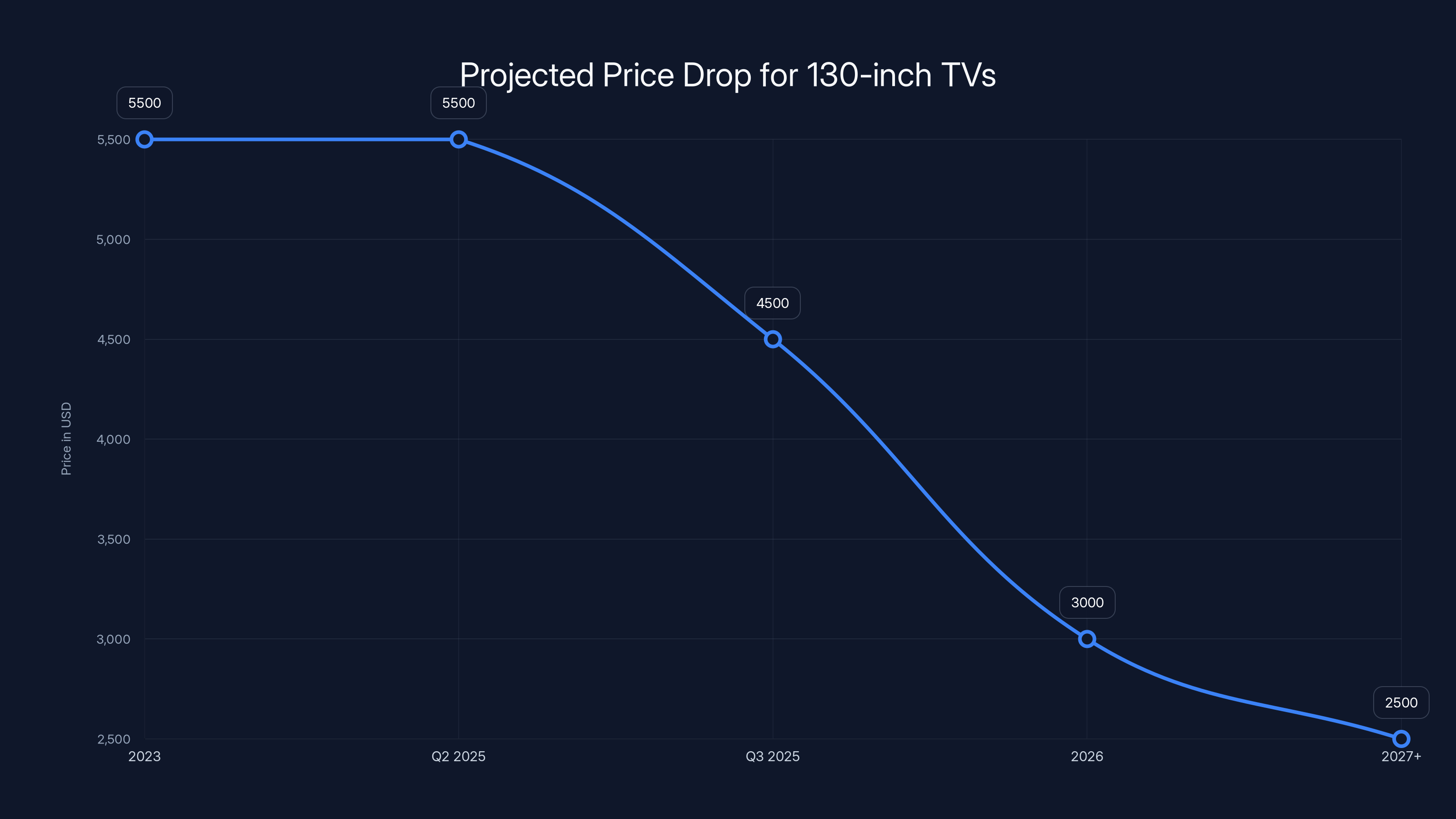

Estimated data shows a significant price drop for 130-inch TVs from

Logistical Complexity: Getting Giants to Consumers

Shipping a 130-inch TV is not the same as shipping five 26-inch TVs.

First, the packaging. A 130-inch panel box can't be a standard cardboard box. It needs reinforced internal bracing, foam padding designed specifically for ultra-large panels, and specialized corner protection. The packaging itself costs

The box is massive. It's approximately 10 feet by 5 feet by 1 foot. A standard shipping container holds far fewer of these than smaller units. Where you might fit 40 units of 115-inch TVs in a single 40-foot container, you might fit only 12 units of 130-inch TVs. That's a dramatic increase in per-unit shipping cost.

Specialized freight carriers are required. You can't throw a 130-inch TV on a standard UPS truck. It requires dedicated freight companies with appropriate equipment. These companies charge premium rates for large items, and they're already stretched thin handling the TV industry's existing large-screen inventory.

Last-mile delivery becomes complicated. Getting a 130-inch TV into someone's home requires planning. Does the door opening allow passage? Does the staircase accommodate the box size? Many customers will need furniture rearrangement before the TV even arrives. Delivery services now require pre-delivery consultations with customers, adding labor cost.

Damage rates increase. Statistics from logistics companies show damage rates for 130-inch TVs in shipping are 2-3 times higher than for 115-inch TVs. A damaged panel in transit costs the entire unit. Replacement panels need emergency shipment. Insurance costs rise. Manufacturers build this risk into their pricing.

Return logistics get nightmarish. If a 130-inch TV arrives damaged or defective, the return process is expensive. A 115-inch TV can be returned via standard freight. A 130-inch TV requires white-glove reverse logistics at premium cost. Some manufacturers now require $400-600 restocking fees on 130-inch returns specifically to cover logistics costs.

International shipping adds another layer. If a 130-inch TV is damaged in international transit, the cost to replace it is doubled. Companies are more conservative with their international 130-inch inventory because the risk-to-reward ratio is unfavorable at current demand levels.

The Display Technology Innovation Factor

Larger panels also drive innovation adoption, and new technology costs money.

When manufacturers introduce a new screen size, they often couple it with display technology upgrades. 130-inch panels are frequently equipped with full-array local dimming backlighting rather than edge-lit systems. This technology costs 40-60% more than edge-lit systems but provides dramatically better contrast and color accuracy.

Mini-LED technology, which divides the backlight into thousands of tiny zones for precise control, is more expensive than traditional LED backlighting. A 130-inch mini-LED TV might have 2,000+ individual LED zones compared to maybe 200 zones in a 115-inch LED TV. The per-zone cost isn't linear. Managing and controlling 2,000 zones requires more sophisticated hardware and more complex firmware.

OLED technology, which doesn't require a backlight at all, is theoretically simpler but practically much harder to manufacture at ultra-large sizes. OLED yields drop even more dramatically than LCD yields at large sizes. That's why 130-inch OLED TVs barely exist right now.

Quantum Dot (QD) technology adds cost. The quantum dot layer, which enhances color and brightness, is more complex to apply uniformly across a larger panel. Application accuracy needs to be tighter. More layers add manufacturing steps and increase defect opportunities.

HDR (High Dynamic Range) processing requires more sophisticated chipsets. The upscaling algorithms, the color gamut mapping, the tone curve adjustments—all of this is more computationally intensive on 130-inch panels with higher resolution and more backlighting zones. Better processors cost more.

Smart TV features might be more comprehensive on premium 130-inch models. More RAM, faster processors, better Wi-Fi 6 or Wi-Fi 6E modules, Bluetooth 5.3 chips. The BOM (Bill of Materials) for electronics in a 130-inch TV is typically $200-300 higher than in a 115-inch TV, even when both are in premium tiers.

115-inch panels achieve a higher yield rate of 90% compared to 65% for 130-inch panels. This lower yield rate for larger panels increases manufacturing costs due to more rejected units.

Market Demand and Volume Constraints

Right now, only a tiny fraction of consumers can actually afford a 130-inch TV or have the space for one.

Market research suggests perhaps 50,000-100,000 units of 130-inch TVs will sell globally in 2025. Compare that to 115-inch TVs, which might sell 200,000-300,000 units in the same period. The volume difference creates a cost disadvantage for 130-inch models.

Lower volume means less leverage with suppliers. When you're buying LED backlights in million-unit quantities (across all your products), you get serious volume discounts. When you need 10,000 units of specialized 130-inch LED backlights, suppliers have less incentive to discount aggressively.

Lower volume also means less automation efficiency. High-volume production lines are worth automating heavily. Lower-volume production might still rely on manual processes for certain steps, particularly in quality assurance. Robotics and automation require upfront investment that only makes financial sense above certain production volumes.

Lower volume affects economies of scale for new components. A new type of connector, a new cable design, a new cooling system—if it's needed only for 130-inch TVs, the per-unit cost stays high until volume ramps up dramatically.

Lower volume also creates inventory risk. Retailers are hesitant to stock too many 130-inch units because they might languish on the showroom floor. Manufacturers have to work harder to move inventory, sometimes accepting lower margins. But those pressures don't apply as heavily to the production cost structure itself.

Structural Engineering and Durability Costs

A 130-inch panel weighs differently than a 115-inch panel. It distributes weight non-uniformly and creates stress concentrations that smaller panels don't.

The stand or mounting solution needs to be engineered differently. A 115-inch TV might use a fairly standard pedestal stand. A 130-inch TV requires a specifically designed, heavily engineered support structure. The stand for a 130-inch TV can weigh 80-120 pounds alone compared to 40-60 pounds for a 115-inch TV.

Wall mounting becomes more critical because floor stands take up too much room. In-wall mounting of a 130-inch TV requires professional installation, usually at an additional cost of $500-1,500. Manufacturers have to engineer the panel to work with professional installation, adding mounting points, calibration systems, and support hardware.

The internal frame structure—the metal chassis that holds the panel in place—is significantly more robust for 130-inch models. The gauge of steel used is thicker. More support ribs are welded. More cross-bracing is added. The frame engineering goes through more rigorous finite element analysis to ensure it won't warp or flex over years of use. This engineering work is expensive, and the resulting frame is more expensive to manufacture.

Cooling systems are more sophisticated. Larger panels generate more heat, particularly with full-array local dimming backlights. Thermal management becomes critical. Manufacturers add active cooling fans (which add cost, complexity, and potential failure points), thermal paste for better heat conductivity, and additional heat sinks. This cooling system might add $50-100 to the BOM.

Power supply design becomes more critical. A 130-inch TV draws more power, particularly if it's using extensive backlighting with full-array local dimming. The power supply unit needs to be rated for higher power and needs more robust design. A power supply rated for 150W costs more than one rated for 100W, and it requires more engineering to handle the thermal loads.

Longevity testing takes longer for 130-inch panels. Manufacturers stress-test displays for 8,000+ hours under adverse conditions to identify failure modes early. For new sizes like 130-inch, they typically run even more aggressive testing protocols, which means higher testing costs and sometimes delays in bringing products to market.

Estimated data shows that 115-inch TVs are projected to sell significantly more units than 130-inch TVs in 2025, highlighting the volume constraints and cost disadvantages for larger models.

Thermal Management and Operational Complexity

Heat dissipation is a serious engineering problem for ultra-large displays.

LED backlights in LCD panels generate heat. The larger the backlight array, the more total heat. A 130-inch full-array local dimming system might have 2,000+ LED zones. Each LED generates a small amount of heat, but 2,000 LEDs generate a significant amount of heat in a confined space.

Uneven heat distribution can cause optical problems. If one region of the backlight system runs hotter than another, the light output can vary slightly, creating visible banding or color shift. Manufacturers need sophisticated thermal modeling software to simulate heat distribution and design cooling systems to maintain uniformity. This software and the resulting hardware add cost.

Thermal interface materials become more critical. The materials used to transfer heat from the LED backlight to the heat sinks need to be high-performance. Typical thermal paste used in consumer electronics might not be adequate. Manufacturers specify premium thermal interface materials that cost several times more than standard materials.

Active cooling becomes necessary on some premium 130-inch TVs. Instead of relying on passive heat dissipation, fans pull air through the backlight chamber. These fans add $30-60 to the BOM, plus they introduce a component that can fail, affecting warranty and support costs.

Fan noise becomes a design challenge. If a TV needs active cooling, the fan can't be so loud that it's distracting during viewing. Sound dampening materials add cost. Vibration isolation adds cost. Engineers need to select fans that balance airflow efficiency with acoustic performance, which limits supplier options and increases per-unit cost.

The increased thermal load also affects the lifespan of components. LED backlights degrade faster at higher temperatures. Electrolytic capacitors in the power supply degrade faster at higher temperatures. To maintain long-term reliability (7-10 years of typical use), manufacturers need to use higher-grade components with better thermal performance, which cost more.

Competitive Positioning and First-Mover Premium

Right now, Samsung, LG, and TCL are the primary manufacturers offering 130-inch TVs. The competition is limited, and that affects pricing.

When there are only three competitors in a niche segment, price competition is less intense. Each company can maintain higher margins without fear of being massively undercut. Once four or five more manufacturers enter the 130-inch space (likely in 2026), margin compression will occur rapidly.

Brand positioning plays a role too. Samsung's 130-inch TVs carry a brand premium. Consumers perceive Samsung as a technology leader, which allows them to charge more for new sizes. By the time smaller brands and value brands enter the 130-inch space, the price will drop significantly because consumers view those brands as lower-cost alternatives.

Innovation cycles affect pricing strategy. Manufacturers want early adopters to pay premium prices for 130-inch TVs now because they'll recoup R&D investments faster. Within 18 months, multiple manufacturers will have 130-inch offerings in multiple tiers (budget, mid-range, premium), and competition will naturally drive down the premium pricing.

Profit margin expectations also influence pricing. 130-inch TVs, being new and specialized, carry higher gross margins (50-65%) compared to mainstream 115-inch TVs (35-45%). Manufacturers intentionally price high to maximize profits while demand is strong and competition is weak.

Historical Precedent: When Sizes Become Standard

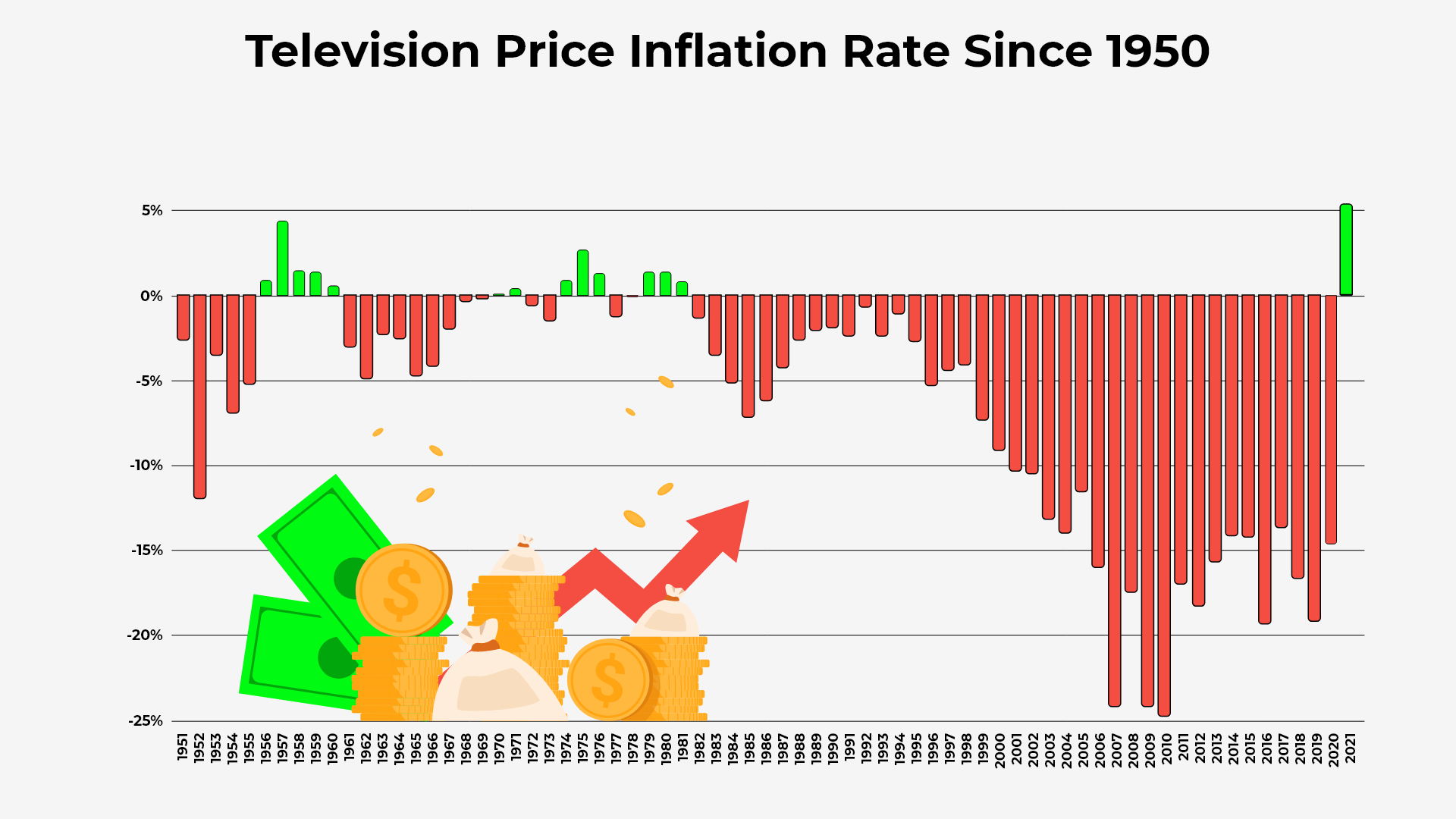

Look back at any size introduction: 75-inch, 85-inch, 100-inch, 115-inch. The pattern is identical.

When 85-inch TVs debuted around 2010-2011, they cost

When 100-inch TVs were introduced around 2018, they cost

The price curves tell you everything. Initial pricing reflects manufacturing difficulty, limited competition, and manufacturer margin optimization. Within 18-24 months, as second and third manufacturers scale production and compete for share, prices drop 30-40%. Within 3-4 years, the size becomes commoditized and price declines slow, stabilizing at a level that reflects truly efficient production.

Expect 130-inch TVs to follow the same arc. Your wait-and-see approach to 130-inch buying is financially sound.

The Real Cost Breakdown: Where Your Money Goes

For a $5,000 130-inch TV, here's a realistic cost allocation:

Panel and display components: $1,800-2,000 (36-40%). This includes the glass substrate, liquid crystals, polarizing films, backlighting, LEDs, optical films, and all the subassemblies.

Electronics and processing: $400-500 (8-10%). The main processors, memory modules, power management ICs, and the logic boards that control everything.

Mechanical engineering and assembly: $600-800 (12-16%). The chassis, the frame, the stand or mounting hardware, plus labor to assemble everything.

Logistics and packaging: $250-400 (5-8%). Specialized packaging, freight shipping, and last-mile delivery logistics.

R&D and manufacturing overhead allocation: $400-600 (8-12%). Your share of the company's investment in developing 130-inch production capacity.

Warranty and support reserve: $150-250 (3-5%). Set aside for warranty claims, returns, and customer support.

Marketing and distribution: $300-500 (6-10%). Advertising the product, retailer incentives, and sales channel costs.

Retailer margin and company profit: $500-700 (10-14%). This is the gross margin available for the manufacturer's profit and overhead after cost of goods sold.

That allocation shows where the 50% premium over 115-inch TVs comes from. It's not arbitrary. It's rooted in the increased manufacturing complexity, the lower yields, the higher material costs, and the infrastructure investment required.

Future Trajectory: When Prices Will Drop

Based on historical patterns and current capacity investments by manufacturers, expect a predictable timeline:

Now through Q2 2025: Early adopter premium pricing. Limited competition. Few options. Prices stay high ($4,500-6,000 for 130-inch TVs).

Q3 2025 through 2026: Capacity ramps. Second and third manufacturers introduce competing 130-inch models. Price competition begins. Expect 15-25% price drops as competition intensifies.

2026-2027: Yield rates improve significantly as manufacturers gain experience. Prices drop another 20-30%. 130-inch TVs hit the $2,500-3,500 range.

2027+: 130-inch becomes a standard size tier. Multiple manufacturers in multiple price points. Pricing stabilizes in the $2,000-3,000 range for quality 130-inch TVs.

This isn't speculation. It's the pattern observed with every previous size introduction.

Manufacturing curves bend the same way every time. Physics doesn't change. Economics follows predictable patterns. Market competition follows predictable patterns. If you're considering a 130-inch TV, the financially rational move is to wait until 2026 when the price is 30-40% lower and your options have quadrupled.

Should You Buy a 130-Inch TV Now?

The answer is almost always no, unless you're in one of these specific categories:

Scenario 1: You're a technology enthusiast who values being first and has unlimited budget. Fair play. You're aware of the premium and you're paying it consciously.

Scenario 2: You have a genuine commercial application (high-end hospitality, corporate installations, specialty retail). The premium might be justified by use case ROI.

Scenario 3: You found a 130-inch TV at a significant discount (this occasionally happens when retailers overstock). In that case, you've sidestepped the premium entirely.

Scenario 4: You're in a geographic region where 130-inch TVs are becoming mainstream faster (certain parts of Asia, particularly China). Market dynamics might push prices down faster in some regions.

For most consumers? Wait. The financially rational choice is waiting 12-18 months. You'll pay less, have more options, and won't be subsidizing the manufacturer's R&D investment.

The 27% size increase and 50% cost increase isn't a permanent state. It's a temporary market inefficiency created by manufacturing constraints and limited competition. These conditions will resolve. When they do, 130-inch TVs will be a much easier purchase to justify.

The Broader Picture: Why Size Premiums Matter

Understanding the real costs behind the 50% premium teaches us something important about technology pricing in general.

When you see a product that costs dramatically more than its smaller sibling, it's rarely arbitrary markup. There are usually real engineering challenges, real manufacturing constraints, and real supply chain complications that explain the premium.

This applies to large-format displays in any category: TVs, monitors, digital signage, industrial displays. It applies to large-format manufacturing of other goods too. Scaling up isn't linear. At certain size thresholds, you hit discontinuities where everything becomes harder, more expensive, and riskier.

Recognizing these patterns helps you make smarter purchasing decisions. Don't assume a high price is pure profit. Research it. Understand the actual constraints. Sometimes the premium is justified. Sometimes it's exploitative. Usually, it's somewhere in between.

For 130-inch TVs specifically, the premium is currently justified by manufacturing reality. But that reality will change. Betting against that change is betting against the entire history of display manufacturing. That's not a bet I'd take.

FAQ

What is the actual size difference between a 115-inch and 130-inch TV?

The measurement refers to the diagonal screen size. A 115-inch TV has a diagonal of 115 inches, while a 130-inch TV has a diagonal of 130 inches. This represents a 13% increase in diagonal measurement, but because screen area increases proportionally to the square of the diagonal, you're actually getting about 27% more screen area. That's a significant jump in viewing real estate, but the production complexity increases far more dramatically.

Why do yield rates drop so dramatically for larger TV panels?

Yield rates drop because the surface area of larger panels increases the statistical probability of defects appearing. A dust particle is invisible on a small screen but impossible to miss on a 130-inch panel. Thermal stress fractures that might not occur on a 115-inch panel become increasingly likely on 130-inch panels due to uneven temperature distribution during manufacturing. The more pixels and backlighting zones involved, the more opportunities for electrical failures or color uniformity issues. Manufacturing yield is determined by the percentage of panels that pass final quality inspection, and larger panels have exponentially more opportunities to fail inspection.

How much of the 50% price premium comes from actual material costs versus manufacturing complexity?

Approximately 35-40% of the final retail price is materials and components, while 8-12% is allocated to manufacturing overhead and R&D investment. This means roughly 20% of the 50% premium is directly attributable to higher material costs and component sourcing challenges specific to 130-inch production. The remaining portion comes from lower yield rates, reduced production efficiency on modified manufacturing lines, and the fixed costs of developing 130-inch production capability spread across lower volumes than mainstream sizes.

When will 130-inch TV prices drop to more affordable levels?

Based on historical patterns from previous TV size introductions, expect the first significant price drops (15-25%) during 2025-2026 as competing manufacturers enter the market. More substantial drops (another 20-30%) should occur by 2026-2027 as yield rates improve and manufacturing processes mature. By 2027-2028, 130-inch TVs should stabilize at prices 30-40% lower than current levels, assuming a 130-inch now costs

Are there any advantages to buying a 130-inch TV now instead of waiting?

The only real advantages to buying now are: you get the newest technology available (which might be marginally better than what's available in 18 months), you potentially get better selection of models and features (as inventory expands before mass market adoption), and if you're an early adopter enthusiast, you get the status of owning the latest and largest size. For most practical purposes, especially if budget is a consideration, waiting provides better value. You'll pay less, have more models to choose from, and won't be bearing the burden of manufacturer R&D cost allocation.

How does the manufacturing complexity of 130-inch panels compare to other ultra-large displays?

130-inch TVs are particularly challenging because they're trying to maintain consumer-level pricing while dealing with scale challenges typically reserved for commercial displays. Commercial large-format displays (used in stadiums, corporate installations, and digital signage) have always accepted lower yields and higher costs because end users expect to pay for scale and reliability. Consumer TVs need high yields and reasonable costs to remain competitive, which is why 130-inch panels push manufacturers to their limits and why the engineering challenges compound so dramatically.

What role do LCD panel suppliers play in 130-inch TV pricing?

Panel suppliers like Samsung Display, LG Display, and BOE have significant control over 130-inch TV pricing because there are only a few companies capable of manufacturing displays at this scale. Manufacturers like Sony, Hisense, and others depend on these suppliers. Limited panel supplier capacity means higher panel costs and longer lead times. The panel itself typically represents 30-35% of the final TV cost, so any premium in panel pricing gets magnified in the retail price. This supplier concentration is one reason why 130-inch TV prices should drop significantly once more manufacturers build capacity.

How does active cooling and thermal management affect the price of 130-inch TVs?

Larger TVs with full-array local dimming backlights (which use 1,500-2,500+ LED zones) generate significant heat that requires sophisticated thermal management. Some 130-inch TVs incorporate active cooling fans, premium thermal interface materials, and additional heat sinks. These components add $50-150 to the bill of materials and increase manufacturing complexity by requiring thermal testing and validation. The need for better thermal performance also mandates higher-grade components throughout the system, all of which contributes to the 50% price premium versus 115-inch models.

Are there any upcoming manufacturing technologies that could reduce 130-inch TV costs?

Yes. Mini-LED technology is maturing and should become more cost-effective for ultra-large displays within 12-18 months. Improved glass sourcing and new optical materials are in development. AI-assisted manufacturing quality control could improve yield rates faster than historical patterns suggest. Rollable or foldable display technologies, while not yet viable for 130-inch displays, might eventually offer cost advantages by allowing different manufacturing approaches. However, the most likely cost reduction comes simply from increased competition and production volume, not from technological breakthroughs.

TL; DR

- The 50% premium is real: A 130-inch TV costs 50% more than a 115-inch TV despite being only 27% larger, reflecting manufacturing challenges that scale non-linearly with size.

- Yield rates plummet: Production defect rates for 130-inch panels are 2-3 times higher than for 115-inch panels, meaning manufacturers must produce many more panels to get sellable units.

- Infrastructure investment is massive: 130-inch production requires dedicated manufacturing lines, new equipment, specialized tooling, and significant R&D spending that's allocated to early units.

- Wait for competition: Historical patterns show 130-inch TV prices will drop 30-40% within 18-24 months as competing manufacturers enter the market and production matures.

- Financial timing matters: Unless you're an early adopter with unlimited budget, waiting until 2026 provides better value, more options, and dramatically lower prices.

Key Takeaways

- Production yield rates for 130-inch TV panels are 60-72% compared to 85-92% for 115-inch panels, meaning manufacturers must produce 40-50% more units to achieve the same sellable output

- The 50% price premium reflects real engineering constraints: larger panels require modified production lines that run slower, specialized components with limited suppliers, and infrastructure investments that don't exist yet

- Material costs account for only 35-40% of the final TV price; the remainder comes from manufacturing inefficiency, R&D allocation, logistics complexity, and margin optimization while competition is limited

- Historical pricing trends show every new TV size (75-inch, 85-inch, 100-inch) commanded similar premiums that compressed 30-40% within 18-24 months as competition and manufacturing matured

- Financially rational consumers should wait 12-18 months for 130-inch TV prices to drop 30-40% rather than paying the current premium that subsidizes manufacturer R&D and production startup costs

Related Articles

- Steam Deck Stock Crisis: Memory & Storage Shortage Impact [2025]

- iPhone Fold 2025: Complete Rumor Guide, Design & Timeline

- Samsung Galaxy S26: What Customers Really Want [2025]

- Why Peloton's $6,695 Treadmill Gamble Failed to Win Over Subscribers [2026]

- LG 27-Inch OLED UltraGear Monitor: $400 Off Deep Dive [2025]

- Why 8K TVs Failed: The Industry's Quiet Retreat [2025]

![Why 130-Inch TVs Cost 50% More Than 115-Inch Models [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/why-130-inch-tvs-cost-50-more-than-115-inch-models-2025/image-1-1771457916940.jpg)