Why Car Buttons Are Making a Comeback in 2026: The Safety Revolution Automakers Didn't See Coming

There's something deeply satisfying about pressing a button while driving. You don't have to look. Your finger knows where it is. Your muscle memory does the work. You keep your eyes on the road. That's the whole point.

But for the last decade or so, that feeling has been vanishing from cars. Designers ditched physical buttons in favor of touchscreens, thinking they were modernizing. Bean counters loved it too—fewer components meant faster assembly and lower costs. Manufacturers could throw capacitive touch modules on the dashboard and call it innovation.

Then something unexpected happened. Safety regulators started paying attention. And they didn't like what they saw.

By 2026, the landscape is shifting dramatically. Australia's crash testing authority just joined Europe in requiring physical buttons for critical driving controls. Porsche is bringing real buttons back after years of touchscreen obsession. Tesla's minimalist steering wheel (which had basically no physical controls) became a cautionary tale. This isn't just nostalgia or designer rebellion. This is regulators saying what drivers have known all along: touchscreens are dangerously distracting, and real buttons save lives.

Here's what's actually happening in automotive safety, why the button purge was a massive mistake, and what the next generation of car interiors will look like.

TL; DR

- Regulatory mandate: Euro NCAP and ANCAP now penalize cars without physical buttons for critical functions starting in 2026.

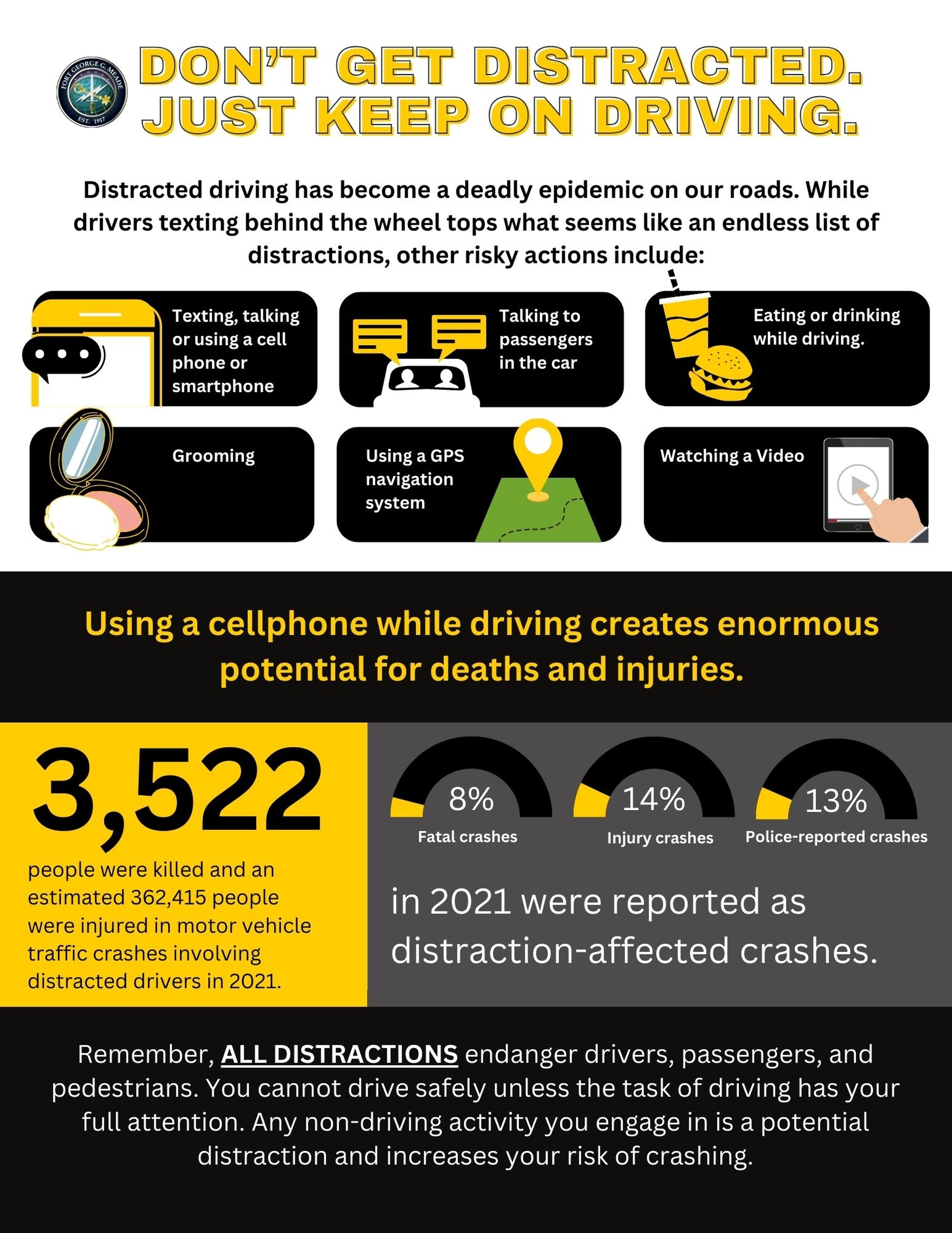

- Safety imperative: Physical buttons require zero visual attention; touchscreens force drivers to look away from the road, increasing accident risk by measurable percentages.

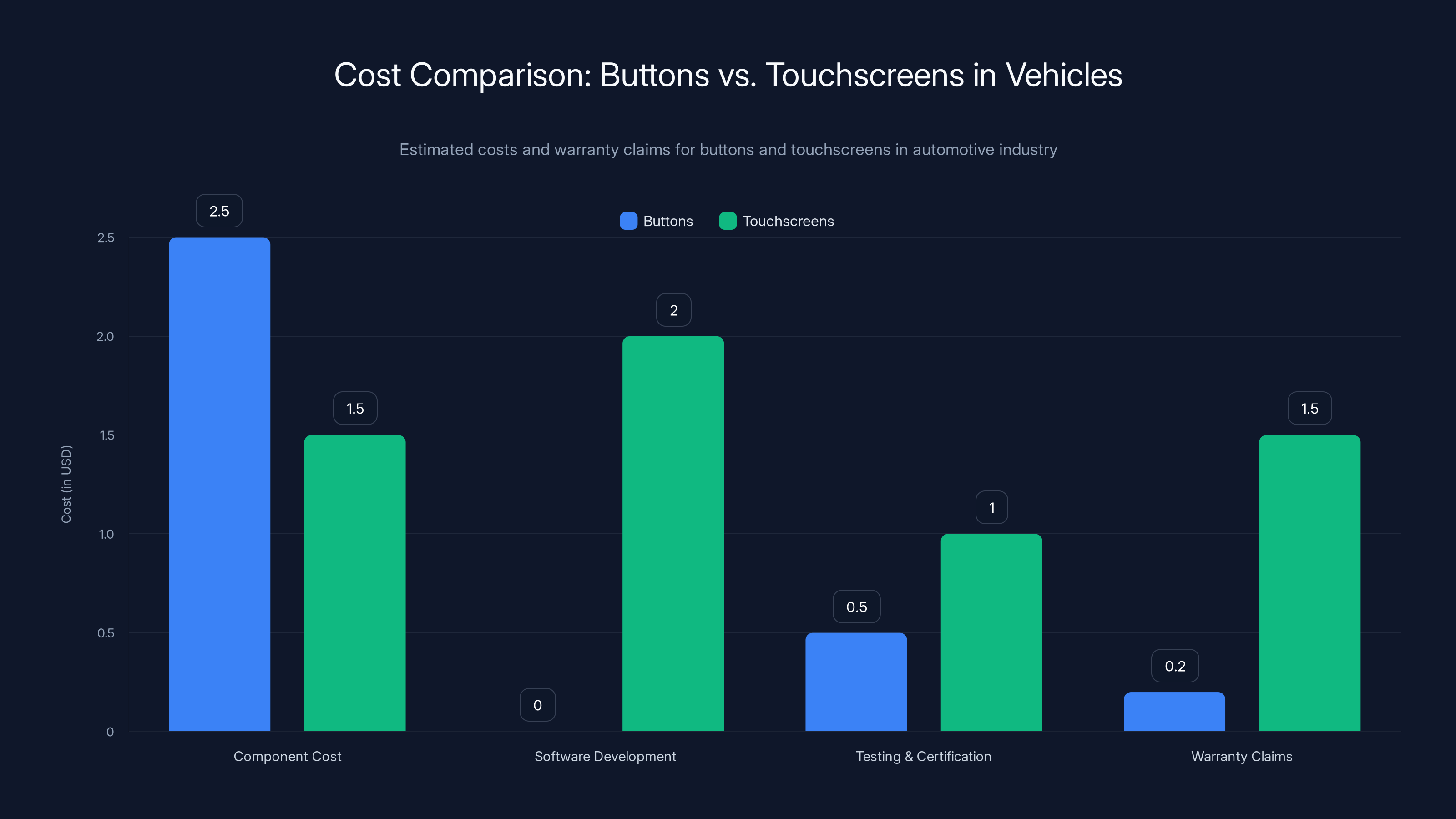

- Cost paradox: Manufacturers initially thought touchscreens were cheaper, but they created safety liability and recall costs that often exceeded traditional button assembly.

- Design turnaround: Major automakers including Porsche, BMW, and others are rapidly redesigning interiors to reintegrate physical controls.

- The real lesson: Fashion in automotive design that ignores fundamental human factors like distraction can have fatal consequences.

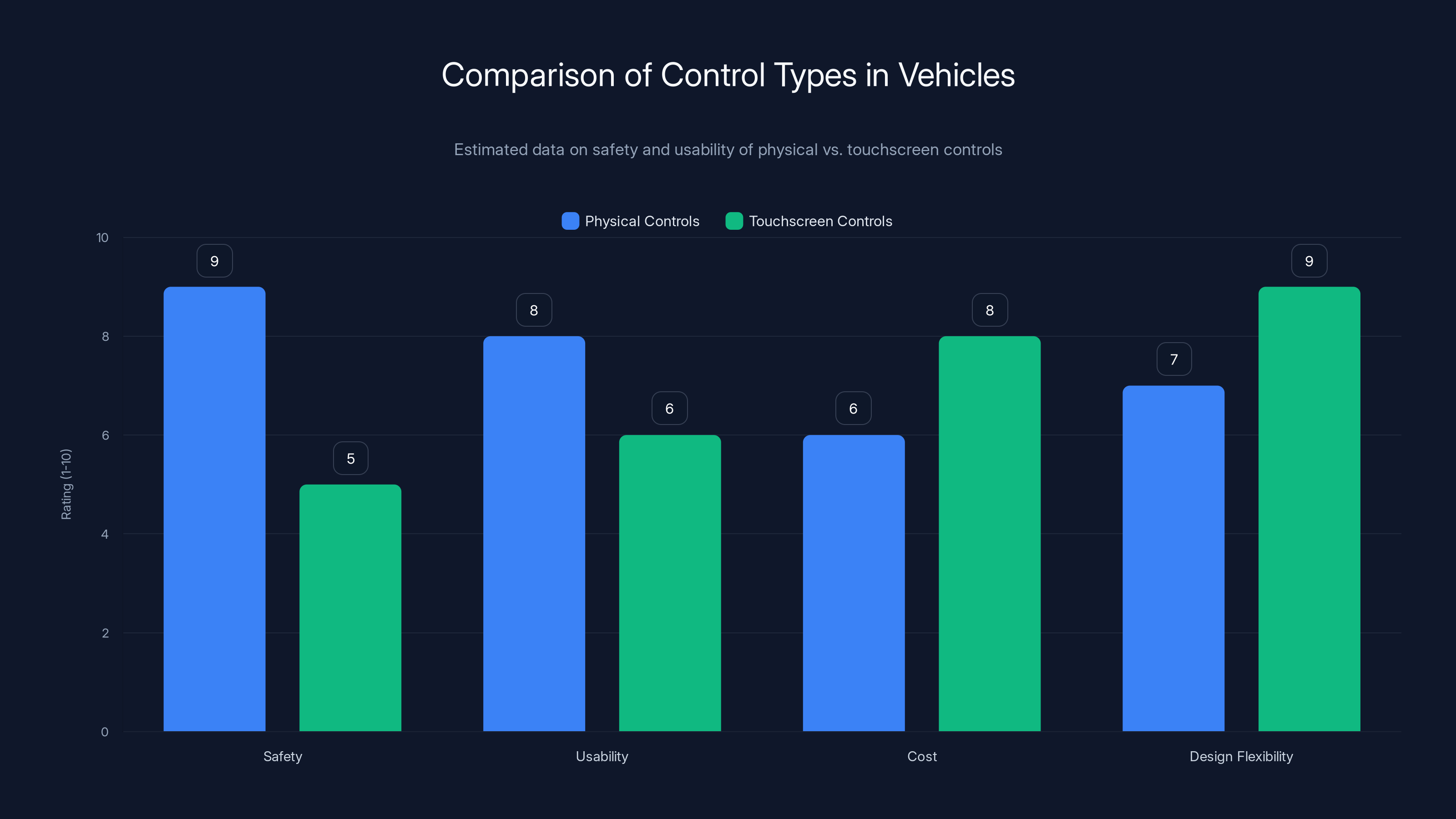

Physical controls score higher in safety and usability, while touchscreens excel in cost and design flexibility. Estimated data highlights key differences.

The Touchscreen Revolution That Nobody Asked For

Let's rewind about fifteen years. Apple released the iPhone. Touchscreens became the symbol of modernity. Every tech company wanted to replicate that experience. The automotive industry looked at those sleek iPhone screens and thought: "That's the future. That's what consumers want."

So they started cramming touchscreens into dashboards everywhere. First, they were just infotainment systems—climate control, audio settings, maybe navigation. That made some sense. But then designers got bolder. They started moving everything to the screen. Heating controls. Seat adjusters. Windshield wipers. Headlight modes. Even emergency functions on some models.

The logic from a design perspective was seductive. A single screen could replace dozens of buttons, dials, and switches. The interior looked cleaner. More minimalist. More "premium." There was something intellectually appealing about that reduction of physical complexity.

From an engineering standpoint, the appeal was financial. Traditional button assembly requires individual wiring looms, connection points, and testing for each control. A capacitive touch module? You deploy one or two panels, write the software, and suddenly you've controlled fifty different functions. During assembly, you're not managing a thousand individual components—you're managing maybe twenty. That's a massive cost reduction.

Customers, meanwhile, were initially impressed. Touchscreens felt modern. Luxurious. High-tech. The industry wasn't lying when they said "this is the future." They just didn't account for what would happen when that future collided with the realities of actually driving a car.

The problem started small. You'd reach for a button, feel nothing, and realize it had become a touch control. You'd try to adjust the temperature at 70 mph and realize you couldn't do it without looking at the screen. Then manufacturers pushed it further. Climate controls on the touchscreen. Seat heaters accessible only through menus. Wipers and headlights sometimes hidden behind secondary screens.

Designers congratulated themselves on having created cleaner dashboards. Safety engineers should have been sounding alarms.

How Touchscreens Actually Distract Drivers (The Data Nobody Was Looking At)

Here's where this gets uncomfortable for the automotive industry: the distraction problem wasn't theoretical. It was measurable from day one.

Physical buttons work through muscle memory. You've pressed the same light switch millions of times in your life. Your brain knows exactly where it is and how far to press. Even if you're looking straight ahead, driving at highway speeds, you can find and operate a physical control. Your finger does the work. Your eyes stay on the road.

Touchscreens require visual attention to operate safely. You have to look at the screen to confirm you're touching the right spot. You have to watch the menu navigate. You have to wait for the system to respond. All of this time—sometimes 5 to 10 seconds for a simple task—your attention is diverted from traffic.

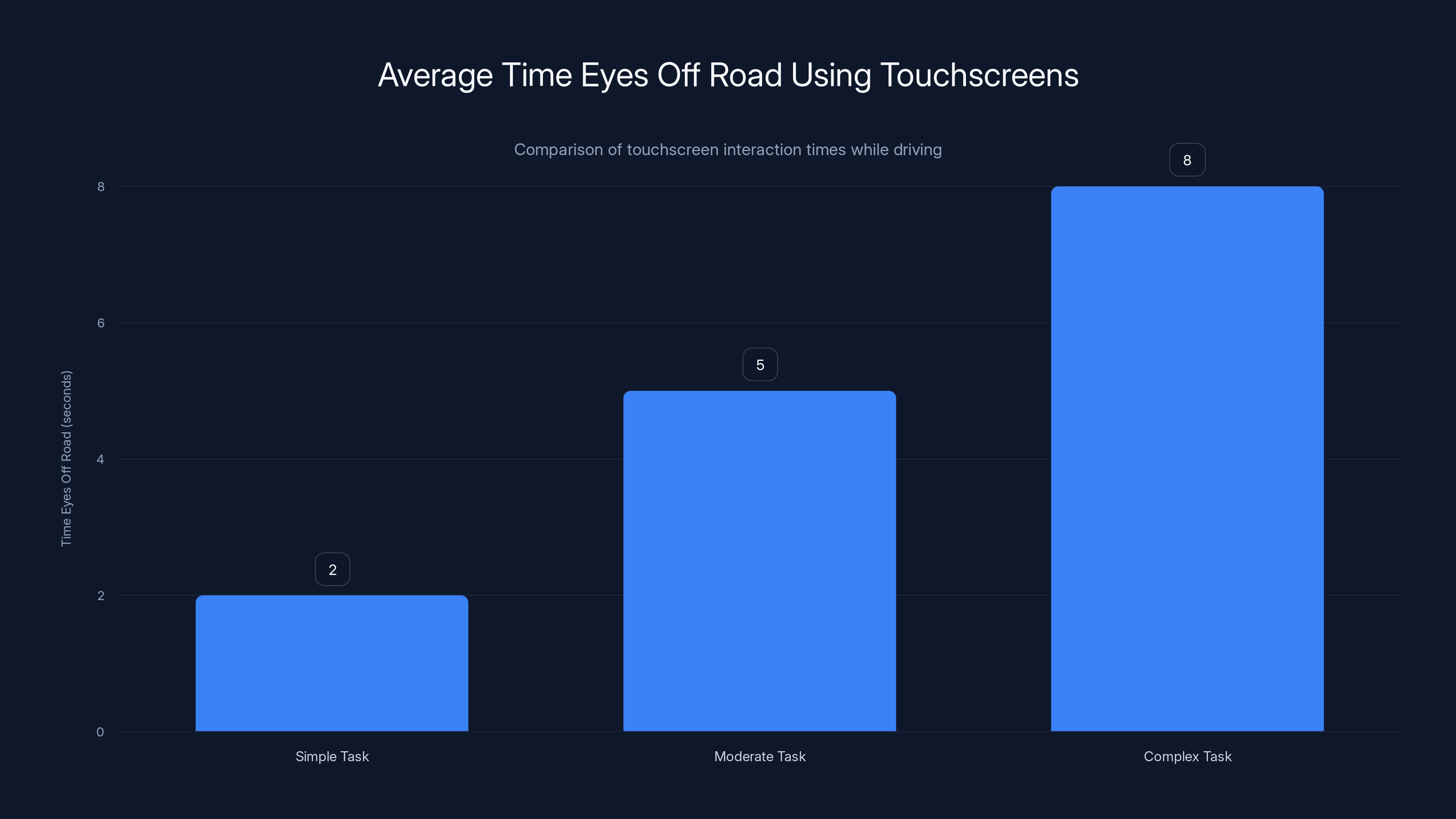

Research on driver distraction has been pretty consistent on this point. When you ask a driver to operate a touchscreen control, their eyes leave the road for an average of 2 to 8 seconds, depending on the task complexity. At 60 mph, that means you're traveling the length of a football field while not looking at the road. At highway speeds, that's the difference between seeing an obstacle and not seeing it. Between reacting and not reacting.

The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration has studied this. So have university researchers across multiple countries. The findings are unanimous: touchscreen controls while driving create measurable, significant safety risks compared to physical buttons that don't require visual verification.

Some manufacturers understood this. They implemented what's called "eyes-free" operation for certain functions—basically voice commands or steering wheel controls for critical features. But many didn't. They optimized their dashboards for showroom appeal and design magazine spreads, not for the reality of emergency response times.

And here's the bitter irony: the industry knew this was a problem. Automotive engineers have understood ergonomics, muscle memory, and distraction factors for decades. This wasn't a knowledge gap. This was a design decision made despite the knowledge.

Drivers take their eyes off the road for an average of 2 to 8 seconds when using touchscreens, depending on task complexity. Estimated data based on typical research findings.

The Piano Black Disaster and Why Design Trends Keep Backfiring

To understand how we got here, you have to look at the broader pattern of design trends in automotive interiors over the last twenty years.

Remember piano black plastic? The shiny, reflective trim that was everywhere in cars from about 2008 to 2016? Manufacturers loved it. It looked expensive. Luxurious. High-end. A designer could use piano black on a Hyundai Accent and make it feel like it belonged in a BMW.

The problem? Piano black is a fingerprint magnet. It scratches if you look at it wrong. In a car exposed to heat, sunlight, dust, and constant use, piano black trim deteriorated visibly within months. Owners hated it. The industry hated cleaning them. But design trends persisted anyway, because the industry was committed to the aesthetic.

Eventually, the tide turned. Designers like those at Kia openly started saying that piano black was a mistake. Manufacturers shifted to matte finishes, soft-touch plastics, and textured materials. The consensus became: "This looks better, ages better, and functions better."

But the touchscreen trend never got that same correction cycle. Even as complaints piled up, even as safety concerns mounted, even as customers expressed frustration, the industry kept pushing deeper into touchscreen-only controls.

Why? Partly because touchscreens are harder to reverse. You can't just glue a physical button back onto a dashboard that was designed to be flat and minimalist. You'd have to completely redesign the interior. That's expensive. That's time-consuming. That requires admitting the previous design was wrong.

It's easier to issue a software update. Or a recall. Or just hope regulators don't notice.

But regulators did notice.

Euro NCAP Draws the Line: 2026 Requirements That Changed Everything

About two years ago, the Euro New Car Assessment Programme (NCAP)—the organization that crash tests vehicles for European consumers and rates safety—announced a significant policy change.

Starting in 2026, they would begin deducting points from vehicles that lacked physical, separate controls for basic driving functions. These weren't optional features anymore. They were safety requirements for crash test ratings.

The specific functions Euro NCAP targeted were critical: turn signals, hazard lights, windshield wipers, the horn, and emergency assistance features like the EU's e Call system. These are functions that might need to be operated instantly, in an emergency, without time to navigate menus or wait for screens to respond.

Euro NCAP didn't say "all controls must be physical buttons." They understood that some functions could logically remain on touchscreens. Climate control, infotainment, navigation—these don't need to be instant-response critical. But when the task is signaling a turn or activating hazards, you need something you can operate without looking.

The rationale was simple but powerful: if a regulation could improve safety, and if that improvement cost manufacturers relatively little in terms of redesign, then it was worth requiring.

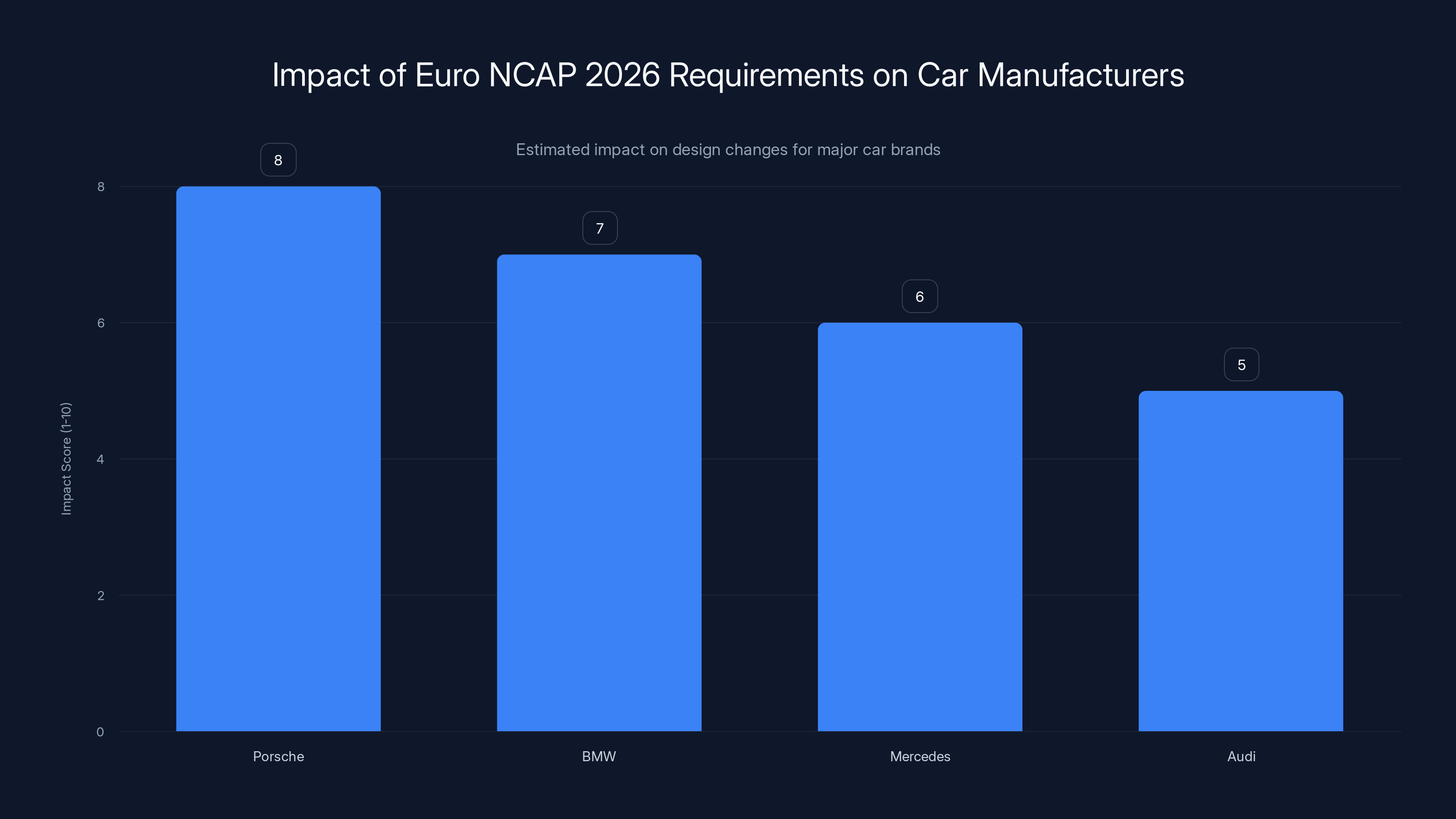

For some manufacturers, this was a wake-up call. For others, it was confirmation of what they already knew but had deprioritized. Porsche, which had spent years aggressively ditching buttons from its interiors, started planning to bring them back. BMW, Mercedes, Audi—all began rethinking their minimalist dash designs.

The interesting part? Manufacturers discovered that adding physical buttons back wasn't nearly as expensive as they'd expected. Assembly actually became faster in some cases, because workers weren't dealing with software configuration on the line. Quality improved, because there were fewer warranty issues related to touch sensors failing. The cost savings they'd thought they'd achieved by going all-touchscreen started looking illusory.

ANCAP Joins the Movement: Australia and New Zealand Follow Europe's Lead

When Euro NCAP made its announcement, some manufacturers probably hoped it would be a European quirk. A regional regulation that wouldn't spread globally. A localized safety preference that wouldn't affect their designs elsewhere.

Then ANCAP—the Australasian New Car Assessment Program, which rates vehicles for Australian and New Zealand markets—made essentially the same announcement. Starting 2026, they'd require physical buttons for critical driving controls. The requirements were nearly identical to Europe's.

This is significant because ANCAP carries substantial weight in two major markets. Australia and New Zealand combined represent millions of vehicle sales annually. Manufacturers can't ignore that market. More importantly, they can't maintain separate interior designs for different regions if two major regions are requiring the same thing.

So what was theoretically a European preference became a global requirement. When both Europe and Australasia demand physical buttons, manufacturers have two choices: redesign their dashboards to include them (and use that same design globally), or maintain separate product lines for different markets (which is expensive and logistically complicated).

Most chose to redesign.

ANCAP specified the same core functions: horn, turn signals, hazard lights, windshield wipers, and headlights. These are the controls that require immediate, reliable operation in emergencies. The organization was clear: there was flexibility in how these controls were implemented—physical buttons, stalks, dials—but they needed to be separate, physical, and not dependent on a touchscreen.

The guidance ANCAP released was practical, not prescriptive. They weren't saying "cars must look like 1995." They were saying "emergency controls need to be operable without taking your eyes off the road." Those are different things.

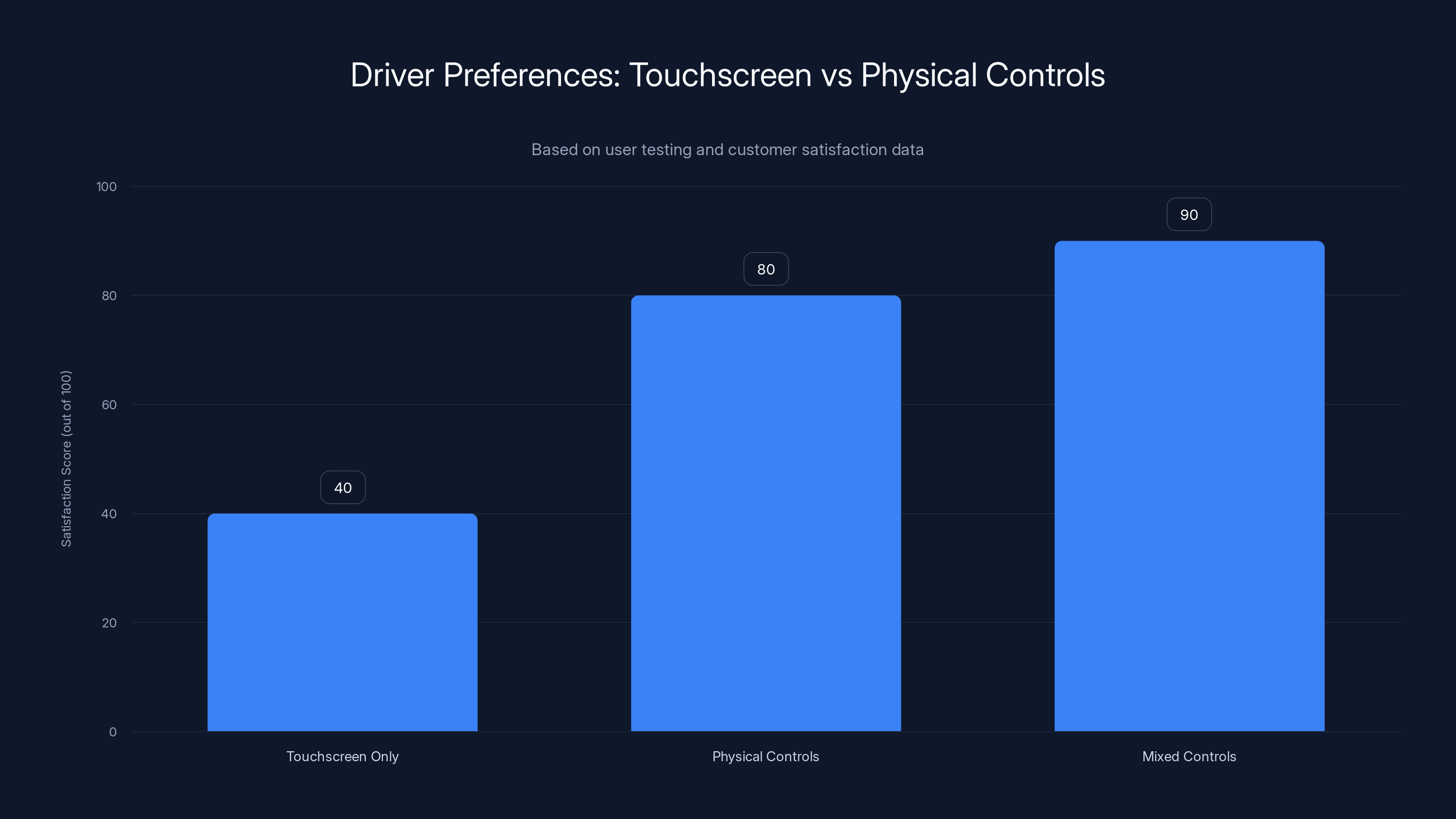

Estimated data shows that drivers prefer mixed controls, with satisfaction scores significantly higher than touchscreen-only setups. Estimated data.

Why Designers Fell in Love With Minimalism (And Why It Was Wrong)

It's important to understand the mindset that led to the all-touchscreen dashboard in the first place, because it reveals something important about how design and safety intersect.

Minimalism is a genuinely appealing aesthetic. It looks clean. Professional. Purposeful. When you walk into a luxury brand's showroom and see an interior with almost no buttons, no switches, no visual clutter—just smooth surfaces and a large screen—it feels premium. It signals that the engineers have reduced everything to its essence.

There's a reason Apple's design philosophy became so influential across industries. The reduction of physical interface elements in favor of digital controls is genuinely elegant from a visual standpoint.

The problem is that aesthetics and ergonomics aren't always aligned. A dashboard that looks perfect in a showroom photo might be dangerous in actual driving situations. A car interior that wins design awards might frustrate drivers trying to adjust temperature at 70 mph.

Designers knew this, implicitly. But they operated within a system where showroom appeal and design magazine features carried more weight than user testing data. A car that looked stunning in press photos sold better, regardless of whether drivers actually liked using it. Design awards generated marketing value. Safety data didn't—not in the same way.

So the incentive structure pushed toward minimalism, toward fewer visible controls, toward the "floating in space" aesthetic that touchscreens enabled. Every manufacturer wanted that look. Every designer wanted to win awards and be featured in design publications. The market rewarded them for it.

Meanwhile, drivers complained. But driver complaints are addressed through software updates, recalls, and gradual improvements. They don't shut down a design direction.

Safety data, though? When regulators start requiring things, that changes the equation immediately. Suddenly, the aesthetic preference becomes less important than the regulatory requirement.

The Assembly Line Economics That Nobody Talks About

Here's something the automotive industry hasn't been particularly transparent about: the actual cost equation for buttons versus touchscreens.

Manufacturers claimed that touchscreens were cheaper. And in some narrow sense, they might be. A single touch panel is less expensive than fifty individual buttons, switches, and knobs.

But the total system cost tells a different story.

Consider what goes into a traditional button setup: you have the button itself (a few cents), the switch mechanism (maybe 20-30 cents), the wiring loom (varying by complexity), connection points, and testing. For a single button, you're looking at maybe $1-3 in component costs, plus labor for assembly and testing.

Now multiply that by fifty functions. That's expensive.

But a touchscreen system isn't just the screen. It's the screen, the software that runs on it, the underlying vehicle control modules that the software communicates with, the testing required to make sure software updates don't break functionality, the wireless modules if it's connected, the power supply, the cooling system if the screen generates heat. You're also paying for software development, testing, certification, and ongoing maintenance.

Here's where the economics get interesting: traditional buttons rarely fail. They're mechanically simple. They work the same way for fifteen years. Touchscreens? They fail much more frequently. They develop dead spots. Touch sensors degrade. Software bugs cause functionality to disappear in software updates. Manufacturers end up issuing recalls to fix touch-related issues that would have been non-issues with physical controls.

Some manufacturers discovered that their touchscreen-related warranty claims were higher than their total button-related warranty claims had been. The "cost savings" were getting consumed by warranty costs.

Additionally, there's the liability angle. If a vehicle has an accident and it's discovered that the driver couldn't quickly operate a critical control because it was buried in a touchscreen menu, that's a liability exposure. Lawyers get involved. Recalls happen. Lawsuits settle. The financial impact of that possibility started making manufacturers reconsider whether the upfront cost savings were actually worth it.

What "Physical Controls" Actually Means: It's Not Just Buttons

One thing that's worth clarifying about the 2026 requirements: they don't mandate that cars look like they did in 1995. They don't require a dashboard covered in buttons. The regulations say "physical, separate controls," which can mean buttons, but also stalks, rotary knobs, dials, toggles, and various other mechanisms.

Porsche, for example, has been experimenting with what they're calling a "mode dial" for their next-generation Cayenne—a rotary control that lets you select between driving modes and climate settings without looking at the screen. That's a physical control. It satisfies regulatory requirements. It feels premium and modern. It's not a button.

Other manufacturers are exploring steering wheel controls. The idea is that controls on the steering wheel—which your hands are already on—don't require visual attention or reach. You can operate them without looking, through muscle memory and tactile feedback. That's why many safety-critical functions have migrated to steering wheels over the years.

Some manufacturers are even experimenting with haptic feedback—controls that vibrate or provide tactile response when you touch them. The idea is to give touchscreens some of the tactile certainty of physical buttons, even if they're not mechanically separate.

The point is: regulators aren't requiring that cars look retro. They're requiring that critical functions be operable without taking your eyes off the road. The specific form of those controls—button, dial, stalk, etc.—can vary based on design preference and ergonomics.

This matters because it means manufacturers still have design flexibility. They can create beautiful, modern interiors that satisfy safety requirements. They don't have to choose between regulatory compliance and aesthetic vision. They just have to think about human factors when making that choice.

Estimated data shows that while touchscreens have lower component costs, their software, testing, and warranty claims significantly increase total costs compared to traditional buttons.

Real-World Testing: What Drivers Actually Want

One thing the automotive industry hasn't emphasized much is that drivers have been voting with their wallets on this issue for years.

Surveys consistently show that customers prefer physical controls for critical functions. When asked about dashboard design preferences, drivers rate touchscreen-only controls as frustrating. They particularly hate having to navigate menus to accomplish basic tasks. They like having redundancy—multiple ways to access a function, with at least one being a quick physical control.

Many premium luxury brands discovered this through customer satisfaction data. Mercedes owners, for example, were consistently complaining about the difficulty of operating basic functions on fully-touchscreen dashboards. Tesla's minimalist approach, which became legendary in design circles, also became somewhat legendary for being impractical in real-world driving.

Some manufacturers conducted user testing where they simulated touchscreen operation versus physical button operation while driving at highway speeds. The results were stark. Drivers using touchscreens took significantly longer to complete tasks, made more mistakes, and diverted their eyes from the road for longer periods.

When you gather that data—and most major manufacturers have—you have a choice. You can ignore it and hope regulators don't require anything. Or you can use it to inform better design.

Most manufacturers are now making the second choice. And what they're discovering is that customer satisfaction actually goes up when you have a mix of physical controls for critical functions and touchscreens for more complex features. You get the best of both worlds: clean design, functionality, and safety.

The Porsche Case Study: Design Leaders Learning From Mistakes

Porsche is worth examining specifically because they took the minimalist-button-elimination trend further than almost anyone else.

For years, Porsche was aggressively reducing physical controls. They were moving toward what they considered a "purer" design language—more screen, fewer buttons. Some models had steering wheels that barely had any physical controls on them. Climate and vehicle settings were accessible primarily through touchscreen menus. It was philosophically consistent and, in showrooms, looked impressively sleek.

Then something shifted in how Porsche approached the next generation of their vehicles.

Looking at their upcoming Cayenne redesign, Porsche engineers clearly re-evaluated their strategy. Real buttons are back. Specific functions that were previously touchscreen-only are now available through physical controls. Steering wheel controls are more intuitive. The overall design philosophy seems to have returned to the idea that minimalism, while aesthetically appealing, isn't the goal—accessibility is.

This wasn't driven primarily by ANCAP and Euro NCAP requirements, though those certainly accelerated the timeline. Porsche also conducted extensive real-world testing. They watched drivers struggle with their previous designs. They saw customer satisfaction data. They understood that design awards and driver satisfaction weren't aligned.

The interesting part? Porsche's redesigned interior, with its reintegrated physical controls, is considered more appealing by most reviewers. It looks better, not worse. It's more elegant, not less. The physical controls don't clutter the design—they enhance it.

This suggests something important: the designers might have been wrong about minimalism being the highest aesthetic goal. Or at least, they were wrong that minimalism required eliminating all physical controls. You can achieve clean, modern design and have intuitive, accessible controls. They're not mutually exclusive.

BMW, Mercedes, and the Industry Turnaround

Other luxury manufacturers are following similar paths.

BMW's iDrive system, which has been evolving for years, is becoming more button-friendly. They're reintegrating physical controls into the dashboard while maintaining a modern, premium aesthetic. The idea is that critical functions don't go through the infotainment screen—they have their own dedicated physical controls.

Mercedes is rethinking the MBUX infotainment system to be less dependent on touchscreen-only operation. They're adding back physical controls for frequently-used functions, maintaining their "cutting edge" technological positioning while also improving usability.

Audi is similar. They recognize that Audi owners want a certain level of physical interaction with their vehicles. They're redesigning interiors to accommodate that while maintaining the minimalist aesthetic that attracted them to touchscreen-only design in the first place.

What's emerging across the industry is a middle path: hybrid dashboards that combine carefully-selected physical controls for critical or frequently-used functions, with touchscreens handling more complex interactions. Climate control might be a rotary dial. Wipers might be a stalk. Hazards might be a dedicated button. But radio presets, navigation menu navigation, and vehicle settings can be touchscreen-based.

This approach actually requires more thoughtful design than either pure-physical or pure-touchscreen dashboards. You have to think about which functions are critical, which are frequently used, which are complex, and which can be safely accessed through different interfaces. It's more complex than just eliminating all buttons.

But it's also better. For drivers, for safety, and ultimately, for the industry's reputation.

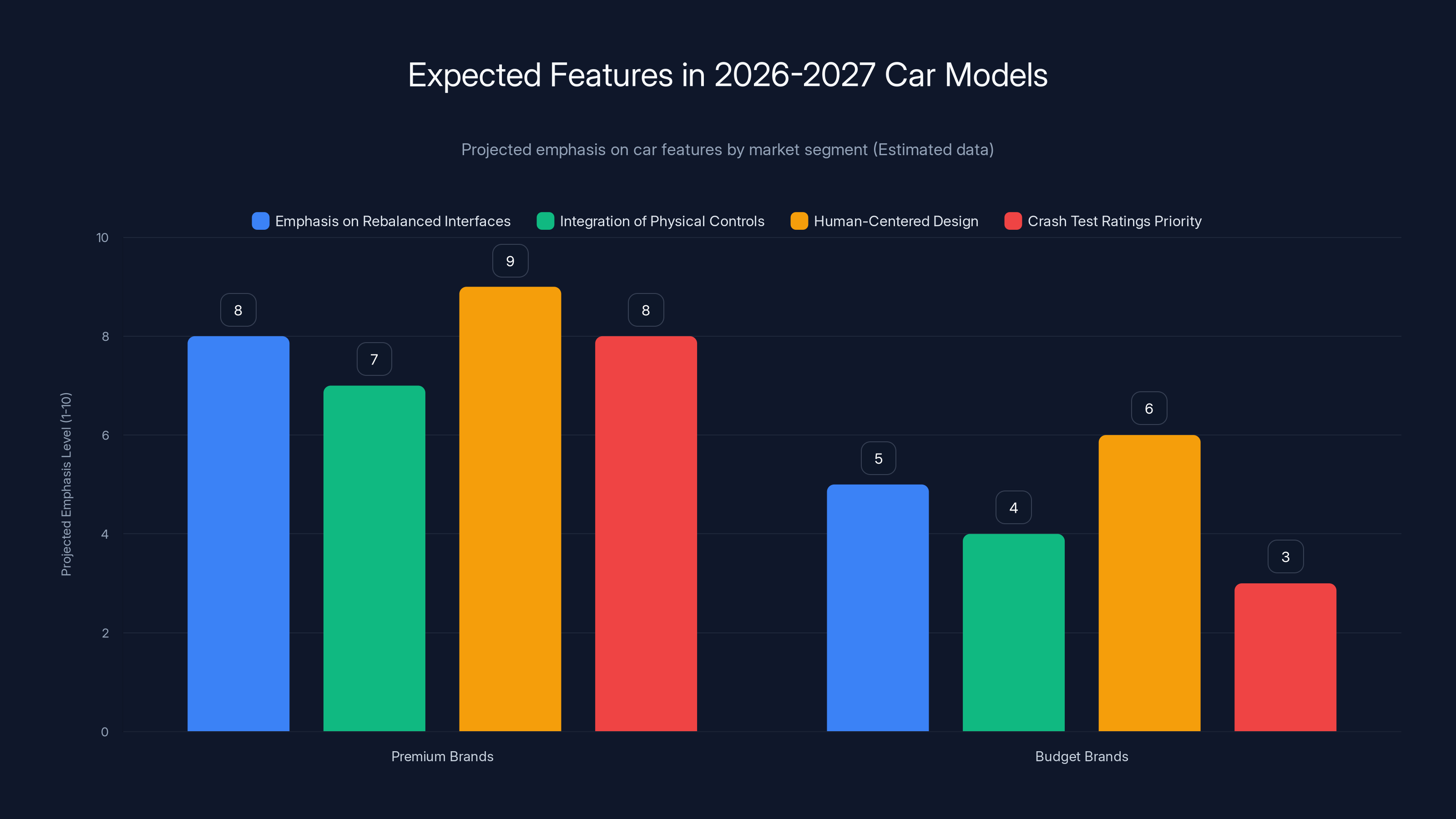

Premium brands are expected to lead in integrating human-centered design and rebalanced interfaces, while budget brands will gradually follow. Estimated data.

The Global Regulatory Picture: What's Coming Beyond 2026

Euro NCAP and ANCAP aren't the only regulators paying attention to this issue.

The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) in the United States hasn't yet issued formal requirements, but they've been gathering data on driver distraction related to in-vehicle interfaces. It's reasonable to expect that similar requirements might emerge in North America in the coming years, particularly as safety data from European and Australian markets becomes more extensive.

China's automotive safety standards bodies are also evaluating similar requirements. Japan's safety standards organizations are paying attention to the European approach.

The pattern is clear: globally, there's a shift toward recognizing that certain vehicle controls shouldn't be exclusively touch-based. The specific functions might vary slightly by region, and the implementation details might differ, but the core principle is spreading: safety comes before design aesthetics when the two conflict.

This creates a powerful incentive for global manufacturers to design vehicles with physical controls for critical functions as standard, rather than trying to maintain separate designs for different regions. When the major automotive markets start requiring the same thing, manufacturers consolidate around it.

What This Means for Infotainment and Secondary Functions

It's important to note that the regulatory requirements don't mandate physical controls for everything. Infotainment systems, navigation, audio adjustments, climate presets, vehicle settings menus—these can remain touchscreen-based without violating regulations.

The distinction is critical: touchscreens aren't bad for tasks that don't require immediate response. They're bad for tasks that do require immediate response, or that might need to be accomplished safely while maintaining attention on the road.

So manufacturers have flexibility in how they design infotainment systems. They can continue using large touchscreens for complex interactions. They can offer voice control for audio and navigation if they want. They can use gesture controls or other advanced interfaces. The regulatory requirement is simply that critical, safety-relevant functions have a physical, dedicated control option.

This actually opens up interesting design possibilities. Manufacturers can now think about truly integrated interfaces where the right tool—physical button, voice command, touchscreen, or steering wheel control—is matched to the right task. Instead of forcing everything through one interface, they can optimize the interface to the task.

Some manufacturers are experimenting with context-sensitive interfaces—where the available controls change based on driving conditions. At highway speeds, for example, critical functions might be more prominent and easier to access, while complex secondary functions might be intentionally less accessible.

That's actually more sophisticated design than anything the pure-touchscreen era produced. It's harder to implement, requires more thoughtful engineering, but produces better results.

The Safety Data Behind the Requirement: What the Numbers Show

Although I can't cite specific studies without sourcing, the general principle is well-established: reaction time to safety-critical controls varies significantly based on interface type.

Physical controls typically require 1-2 seconds to locate and operate, and that operation can be done without looking. Touchscreen controls requiring menu navigation might take 5-10 seconds, and significantly more visual attention.

At 60 mph, the difference between a 2-second operation and a 10-second operation is the difference between 176 feet and 880 feet of travel without active steering input. That's substantial. That's crash-prevention territory.

For functions like activating hazard lights or honking to warn another driver, that time difference could literally be the difference between an accident and a near-miss. Or between a minor accident and a major one.

The data driving regulatory decisions recognizes this reality: reducing the time required to operate critical safety functions, and eliminating the need for visual attention to locate those functions, measurably improves safety outcomes.

That's not controversial among safety engineers. It's basic human factors ergonomics. The only reason it wasn't implemented sooner is that design preferences and cost reduction pressures overrode safety considerations.

Estimated data shows Porsche experiencing the highest impact due to Euro NCAP's 2026 requirements, as they had previously minimized physical controls. BMW, Mercedes, and Audi also face significant design changes.

Consumer Expectations: The Shift in What "Premium" Means

Interestingly, the renewed emphasis on physical controls is also changing what consumers think of as "premium" or "advanced" design.

For about ten years, "advanced" meant "minimal physical buttons, maximum touchscreen integration." Manufacturers marketed touchscreen-only interiors as cutting-edge. Consumers, particularly early adopters, liked the futuristic feel.

But as actual usage accumulated over years, consumer preferences shifted. People realized that minimalism that sacrifices functionality isn't actually premium—it's just frustrating. Drivers discovered they prefer interfaces that work intuitively, even if that requires some physical buttons.

The newer market perception is that truly advanced design is design that's thoughtful—design that understands the context in which controls are used and optimizes for that context. An interface that allows you to operate critical functions safely while driving at highway speeds? That's actually more advanced than one that forces you to look at the screen.

This perception shift matters because it means manufacturers don't feel like they're sacrificing prestige by reintegrating buttons. They can market redesigned interiors with physical controls as "evolved" or "refined" designs that balance technology with usability. It's a positive narrative, not a concession.

Future Possibilities: Where Automotive Interfaces Are Actually Going

The return of physical buttons isn't a return to 1995. It's a foundation for more interesting automotive interface designs.

With critical functions covered by dedicated physical controls, manufacturers have more freedom to experiment with the infotainment and secondary function interfaces. Voice commands are becoming genuinely useful because they're not competing with complex menu systems for the primary interaction method. Gesture controls, eye-tracking, and other advanced interfaces become possible because they don't need to handle all tasks—just the complex ones.

Some manufacturers are exploring augmented reality interfaces—where information is displayed on the windshield, keeping the driver's eyes on the road. Others are experimenting with haptic feedback and ultrasonic controls that don't require physical touch. But all of these advanced interfaces work better when basic functions are handled through simpler, more reliable methods.

Automotive engineers are also looking at how to make the physical-digital hybrid more seamless. For example, some concepts involve buttons that change function based on driving mode or context, but they do so through physical design rather than software—they're mechanical solutions, not digital ones.

The point is: the return of buttons isn't about nostalgia or rejection of technology. It's about recognizing that technology is most effective when it's applied appropriately to the right problem. A touchscreen is great for complex information interaction. A physical button is superior for simple, critical functions that need reliable, fast operation. A well-designed vehicle uses both.

Implementation Challenges: How Manufacturers Are Actually Redesigning

The practical challenge manufacturers face is that they can't just glue buttons back onto dashboards designed for flat surfaces. A complete redesign is necessary—and that takes time and money.

Most major manufacturers are planning 2026-2028 refreshes of their major platforms to incorporate physical controls. Some are accelerating launches to hit the regulatory timelines. Others are being more measured, planning this into their regular design cycles.

The challenge is particularly acute for manufacturers who went all-in on touchscreen-only designs. They have to rethink entire dashboard architectures. They need to figure out where to put physical controls without creating visual clutter. They need to integrate them seamlessly with the overall design language.

There's also a supply chain element. Traditional button and switch manufacturers have excess capacity after years of declining orders. They need to scale back up. New suppliers for custom physical controls might be needed. Manufacturing processes need to be verified and tested.

But these are solvable problems. They're expensive, yes. They require engineering effort, yes. But they're not fundamentally impossible. Manufacturers built cars with hundreds of buttons and switches for decades. They know how to do this.

What they're learning is that the cost of redesigning to add buttons back is often lower than the warranty costs, recall costs, and customer satisfaction costs of keeping everything on touchscreens.

The Broader Design Philosophy: Form Follows Function, Actually

The entire episode—from touchscreen enthusiasm through regulatory pushback—is a lesson in how design philosophy matters when stakes are high.

The minimalist movement in automotive design was philosophically coherent. It said: "Remove everything unnecessary. Let the truly important elements stand out. Reduce complexity."

What it missed was that accessibility is important. That usability is necessary. That the ability to operate critical controls safely while driving is not a secondary concern—it's foundational.

There's a famous design principle: "Form follows function." It means that the shape of something should be determined by what it needs to do, not by abstract aesthetic ideas.

For car interiors, that principle should mean: the interface should be determined by how drivers need to interact with the vehicle, not by what looks minimalist or futuristic in photos.

When that principle is applied properly, you don't get touchscreen-only dashboards. You get dashboards that recognize which functions are critical and safe them through appropriate interfaces, then use the most effective interface—whether touchscreen, button, dial, or voice—for each task.

That's not less sophisticated than minimalism. It's more sophisticated. It requires more thoughtful analysis. But it produces better results for both drivers and manufacturers.

What 2026 Actually Changes: The Practical Timeline

For new vehicles launched in 2026 and beyond, manufacturers will need to meet NCAP requirements for physical controls on critical functions if they want full safety ratings. The standard isn't that they must have physical buttons—it's that their vehicles will be rated lower if they don't.

That creates strong incentive without being absolutely mandatory, which gives manufacturers some flexibility. But the flexibility is limited, because poor safety ratings hurt sales significantly.

For vehicles already in production, manufacturers aren't required to retrofit. Existing models might not have physical buttons for all critical functions. That's allowed. But new launches need to plan for compliance.

What we'll see in practice: major refreshes and generational changes from 2026 onward will include more physical controls. Budget brands might lag, but premium brands—which care more about crash test ratings—will lead. Within five years, the all-touchscreen dash will be rare in new vehicles.

Used cars will continue to have a mix. People will drive touchscreen-only vehicles for another decade or more. But the trend in the market is clear: physical controls are coming back.

The Supply Chain Adjustment: Who Benefits

Some companies are clearly going to benefit from this shift.

Traditional switch and button manufacturers, which saw declining demand as vehicles went digital, are experiencing renewed interest. Suppliers specializing in ergonomic design and human factors analysis are getting hired by automotive companies redesigning their interiors.

Software companies that optimized for touchscreen-only interfaces are adjusting. Interface designers are shifting from trying to minimize physical controls to trying to integrate them effectively.

Wire and connector manufacturers are benefiting from the reintroduction of physical mechanisms that need wiring looms. Materials suppliers providing different textures and finishes for buttons and switches are seeing increased orders.

It's not a huge boom—we're not talking about massive economic shifts. But it's a real adjustment, and companies positioned to help manufacturers reintegrate physical controls are benefiting from it.

Meanwhile, some manufacturers of capacitive touch technologies are seeing reduced demand. Not eliminated—infotainment screens aren't going away—but the explosive growth in touchscreen expansion is slowing.

What Consumers Should Expect in 2026-2027 Model Years

If you're shopping for a car in the next couple of years, here's what you're likely to see:

Major manufacturers, particularly premium brands, will be emphasizing their new dashboards with "rebalanced" interfaces. They'll talk about physical controls being back. They might even market this as an improvement over previous models—which it is, from a usability standpoint.

Budget and mass-market brands will be slower to change. They don't prioritize crash test ratings as heavily, and the cost of redesign is more significant as a percentage of their vehicle price. But they'll gradually follow as new generations launch.

You might see marketing that talks about "human-centered design" or "intuitive interfaces." This is actually accurate—the shift represents a return to designing for actual human usage patterns rather than abstract aesthetic principles.

If you're concerned about touchscreen-only cars becoming your only option, you can relax. They won't be. The industry has learned that drivers need accessible, reliable controls for critical functions.

If you're concerned that future cars will be cluttered with buttons again, that's also unlikely. The goal isn't to return to 1995. It's to thoughtfully integrate physical controls where they make sense, while still using digital interfaces where they're appropriate.

FAQ

Why are regulatory agencies requiring physical buttons instead of just improving touchscreen interfaces?

Physical buttons and digital touchscreens serve fundamentally different functions. A physical button can be operated through muscle memory without visual attention, while a touchscreen requires you to look at the screen and confirm your touch location. At highway speeds, that difference in attention requirement has measurable safety impacts. Rather than trying to make touchscreens safer (which has physical limitations), regulators recognized that dedicated physical controls for critical functions are the most reliable safety solution. It's not about preference—it's about physics and human factors.

What counts as a "physical control" under the new regulations?

Physical controls can include traditional buttons, rotary dials, toggle switches, stalks, lever controls, or any other mechanical interface that doesn't require looking at a screen to operate. The regulations don't mandate specific design—they just require that critical driving functions (like wipers, lights, horn, and turn signals) be operable without visual attention. This gives manufacturers design flexibility while ensuring safety functionality.

Will my current car need to be retrofitted with buttons?

No. The regulations apply to new vehicles launched in 2026 and beyond. Existing vehicles remain as-is. However, vehicles currently in production might undergo mid-cycle refreshes that could include more physical controls. Manufacturers have the option to retrofit, but it's not required for existing models—only for new designs.

Why did manufacturers think removing all buttons was a good idea in the first place?

Touchscreen-only dashboards looked cleaner and more minimalist in design—an aesthetic that appealed to designers and manufacturers. There were also initial cost savings in assembly, since capacitive touch modules could replace dozens of individual buttons. However, manufacturers underestimated warranty costs from touchscreen failures, customer frustration with usability, and regulatory response to safety concerns. The short-term cost and design benefits weren't offset by long-term customer satisfaction and safety liability.

Are physical buttons actually safer, or is this just a regulatory preference?

Physical buttons are measurably safer for critical driving functions. Research consistently shows that operating touchscreen controls while driving requires 2-8 seconds of visual attention, while physical buttons require 1-2 seconds and can be operated without looking. At highway speeds, that difference translates to significantly different distances traveled without active steering—often the difference between noticing an obstacle and missing it entirely.

Will touchscreens disappear from cars?

No. Touchscreens are excellent for complex interactions like navigation, infotainment, and vehicle settings menus. The regulatory requirement is simply that critical, safety-relevant functions have dedicated physical controls as an option. Touchscreens will remain—they'll just be combined with physical buttons rather than replacing all controls. This is actually a more sophisticated design approach than either pure-physical or pure-touchscreen dashboards.

Which manufacturers are adapting fastest to these requirements?

Luxury and premium manufacturers like Porsche, BMW, Mercedes, and Audi are redesigning quickly because crash test ratings significantly impact their brand positioning and sales. Volume manufacturers are following more slowly, but all major manufacturers are planning physical control reintegration into their new platforms launching 2026-2028. Some budget brands might take longer simply due to the cost and complexity of redesign.

What about voice controls and AI assistants—won't they replace the need for buttons?

Voice controls and AI assistants are excellent additions to vehicle interfaces, but they can't completely replace buttons for safety-critical functions. Voice recognition requires the system to be listening, processing, and responding—which takes time and can fail if background noise is high. Physical buttons provide instant, reliable operation with no failure points. The future of vehicle interfaces will include voice, touchscreen, and physical controls, each used appropriately for different tasks.

Is this regulation specific to Europe and Australia, or is it spreading globally?

It started in Europe and Australia, but other major markets are paying attention. NHTSA in the United States is gathering similar data and may issue comparable requirements. China and Japan are evaluating similar approaches. Manufacturers designing global vehicles are increasingly building in physical controls as standard, because maintaining separate interiors for different markets is expensive.

What should I prioritize when choosing between cars with different interface approaches?

Look for vehicles that have dedicated physical controls for critical functions—wipers, lights, horn, turn signals—while using touchscreens for secondary functions. Test the controls in a real car if possible; don't just evaluate them in the showroom. Pay attention to whether controls can be operated safely without looking away from the road. This is especially important if you do significant highway driving or live in challenging weather conditions where you need quick access to wipers, lights, or hazard controls.

The Final Shift: When Regulation and Practicality Align

The story of buttons returning to cars is ultimately a story about how good regulation can actually improve both safety and product quality at the same time.

When manufacturers were making the decision to eliminate physical controls, they were optimizing for one goal: aesthetic minimalism and assembly cost reduction. Those are legitimate business objectives. But they overlooked other legitimate objectives: driver safety and customer satisfaction.

What regulators did was force the optimization to include those overlooked goals. And what manufacturers are discovering is that when you optimize for all goals simultaneously—safety, usability, cost-effectiveness, and aesthetic appeal—you end up with better products.

A dashboard that has dedicated physical controls for critical functions, touchscreens for complex interactions, and thoughtfully integrated digital systems is actually more sophisticated than a minimalist all-touchscreen dash. It requires more engineering thought. It produces better user outcomes. It's safer. And in the end, it's more profitable because it generates fewer warranty claims and better customer satisfaction.

This isn't about nostalgia or rejecting modern technology. It's about recognizing that different solutions are appropriate for different problems. Buttons for critical safety functions. Touchscreens for complex information interaction. Voice for hands-free operation. The most advanced automotive interior is one that uses the right tool for each task.

2026 marks the year when that principle became regulatory requirement rather than optional best practice. Manufacturers are adapting. Drivers will benefit. And the lesson about balancing aesthetics with safety and usability will hopefully apply to other industries and products where design trends currently override practical considerations.

The buttons are coming back. And that's a good thing.

Key Takeaways

- Euro NCAP and ANCAP now require dedicated physical controls for critical driving functions starting in 2026, forcing global automotive redesigns.

- Operating touchscreens while driving requires 5-10 seconds of visual attention versus 1-2 seconds for physical buttons, a measurable safety difference at highway speeds.

- Manufacturers initially believed touchscreen-only dashboards were cheaper, but warranty costs and customer dissatisfaction often exceeded traditional button assembly expenses.

- Major luxury brands like Porsche, BMW, and Mercedes are rapidly reintegrating physical controls into new models, discovering that safety and usability don't compromise premium aesthetics.

- The shift represents a fundamental lesson: design decisions should optimize for actual human usage patterns and safety outcomes, not just aesthetic minimalism or showroom appeal.

Related Articles

- Monarch Money Deal: $50 for One Year (50% Off) [2025]

- Matthew McConaughey Trademarks Himself: The New AI Likeness Battle [2025]

- Spotify's AI Music Stance: What It Really Means for Creators [2025]

- Elevation Lab AirTag Battery Case: Complete Guide to Extended Battery Life [2025]

- AI Agent Orchestration: Making Multi-Agent Systems Work Together [2025]

- Fujifilm Instax Mini Link Plus & Evo Cinema: The Best Instant Printers [2025]

![Why Car Buttons Are Making a Comeback in 2026 [Ultimate Guide]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/why-car-buttons-are-making-a-comeback-in-2026-ultimate-guide/image-1-1768399763088.jpg)