Why VR's Golden Age is Over (And What Comes Next)

There was a moment when everyone believed. Not just believed—they knew. Virtual reality was coming. Augmented reality was the future. Mixed reality would revolutionize how we work, heal, and connect. The hype was intoxicating. Billion-dollar acquisitions. Lavish developer conferences. Promises of hands-free computing, remote telepresence, and completely reimagined workplaces.

Then reality—the actual kind—set in.

Look, I'm not here to say "I told you so," but the writing's been on the wall for years now. The enterprise VR dream didn't just fail quietly. It crashed spectacularly. Microsoft killed Holo Lens. Google Glass evaporated. Meta abandoned the Quest Pro. Even worse, Meta's own internal assessment admitted the company spent enormous capital on a vision that never materialized into actual business value.

This isn't about one bad product or a single company's misstep. This is about an entire technology sector that oversold capabilities, underestimated friction, and built a business model on aspirations rather than actual use cases. And here's the brutal truth: there's still no clear home for immersive VR headsets in business computing. Not today. Probably not tomorrow either.

But the story doesn't end there. While immersive VR collapsed under its own weight, something more practical—something less flashy but infinitely more useful—is quietly emerging. Smart glasses powered by AI. Android XR running on multiple hardware platforms. Tools designed for real work, not spectacle.

Let me walk you through exactly what happened, why it happened, and where the actual future of spatial computing is heading.

TL; DR

- Immersive VR failed in enterprise: Microsoft Holo Lens, Meta Quest Pro, and other full-immersion headsets never solved critical business problems and faced prohibitive costs, comfort issues, and software limitations.

- The promises never materialized: Features like x-ray vision, reliable hand tracking, and seamless software integration remained science fiction while headset prices stayed prohibitively high.

- Meta's $15+ billion gamble didn't pay off: Meta spent more on spatial computing than any company in history, yet abandoned gaming studios and pivoted away from immersive VR toward smart glasses.

- Smart glasses are the actual future: Lightweight AR glasses with AI integration offer practical value without the comfort penalties and cost of immersive headsets.

- Android XR could change the game: Google's platform approach allows multiple manufacturers (Dell, HP, Lenovo, Asus) to build pro-grade business tools instead of relying on a single company's ecosystem.

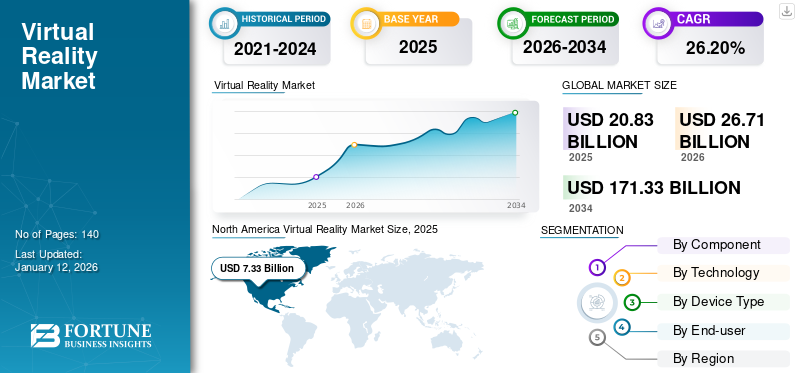

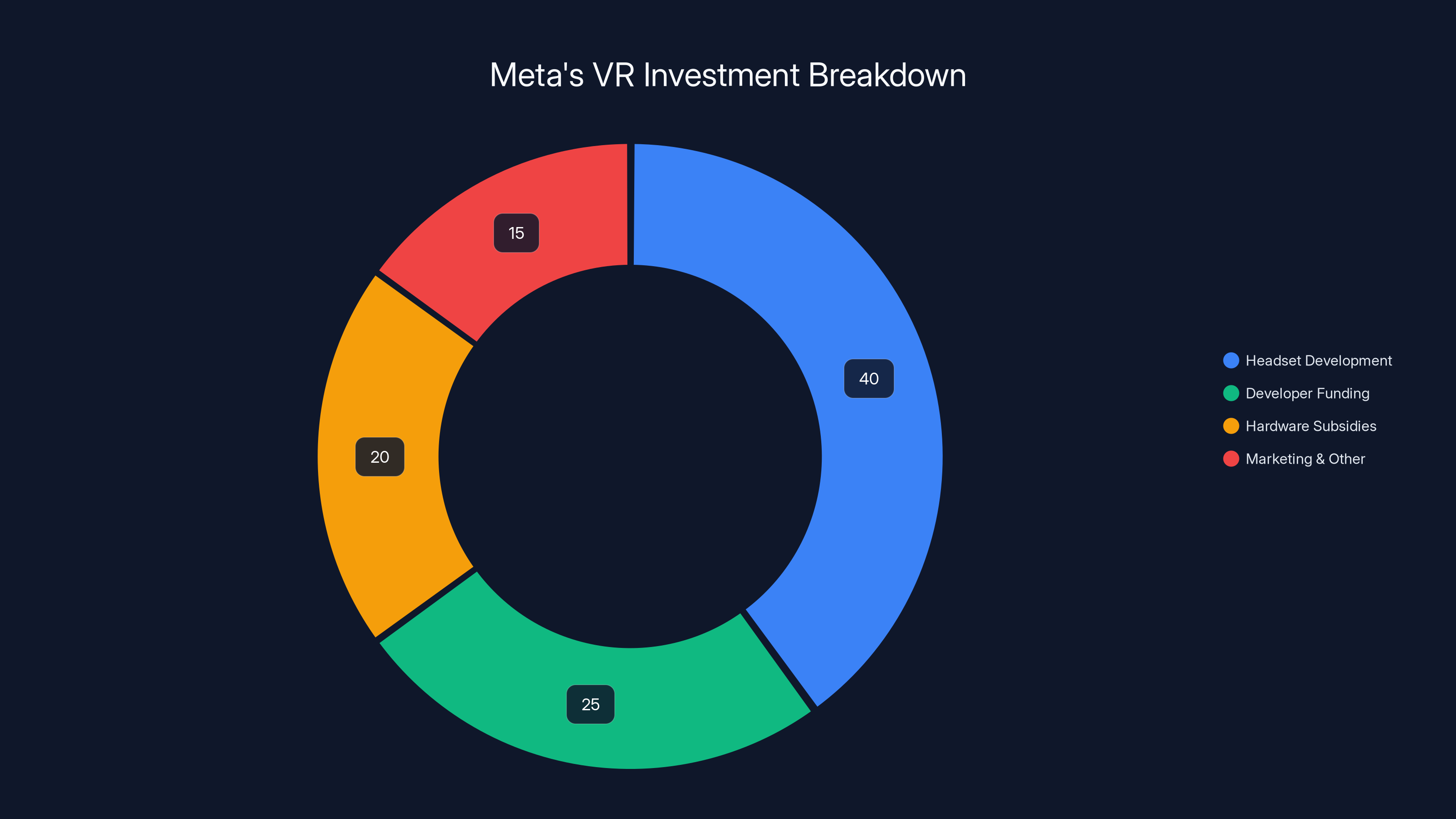

Estimated data shows that a significant portion of Meta's VR investment was directed towards headset development, followed by developer funding and hardware subsidies.

The Promise That Never Was

When Meta acquired Oculus in 2014 for $2 billion, it was a watershed moment. Facebook's leadership didn't buy Oculus because they wanted to make video games. They bought it because they saw an escape hatch. A way to own a platform. A path to independence from Apple's App Store and Google's Play Store.

Google had done something similar years earlier with Android. When the smartphone revolution began, Google realized that Apple controlled the experience, the profits, and the relationship with users. Android was Google's defensive move—a way to ensure they wouldn't be locked out of the mobile future. Meta looked at that playbook and thought: We need our own platform before spatial computing consolidates around Apple or someone else.

The logic made sense. The execution... well, that's where things got messy.

During the 2010s, Meta poured resources into making VR mainstream. And I mean poured. Quest headsets. Developer conferences. Partnerships. Marketing budgets that dwarfed competitors. The company was essentially subsidizing VR hardware—selling devices at a loss to build installed base and developer momentum.

Externally, Meta marketed Quest as a gaming device. Internally, though, the real narrative was always bigger. This wasn't just about games. This was about replacing smartphones. This was about building the next computing platform. This was about Meta's survival in a world where Apple and Google controlled how people accessed the internet.

The enterprise pitch was simple: Why are you still staring at screens? Why use outdated mouse-and-keyboard interfaces when you could have hands-free computing? Why have conference calls on flat displays when you could meet avatars in a shared virtual space? Doctors could perform remote diagnosis. Architects could walk through buildings that don't yet exist. Remote collaboration would be indistinguishable from in-person presence.

It was seductive. It was compelling. It was also almost entirely fictional.

The Technology Actually Delivered vs. The Hype

Here's where we separate the actual facts from the marketing. Let me be specific about what these devices could—and more importantly, couldn't—actually do.

What the hype promised:

- X-ray vision and thermal imaging

- Perfect hand tracking in any lighting condition

- All-day comfort for 8-hour work shifts

- Field of view matching human eyesight

- Seamless software integration with existing enterprise systems

- Instant remote telepresence indistinguishable from being there

What actually existed:

- Limited AR overlays in constrained environments

- Finicky hand tracking that required specific lighting and frequently failed

- Headsets that induced nausea and discomfort after 30-90 minutes

- A field of view so narrow that peripheral awareness was essentially absent

- Software that required months of custom integration and often remained unreliable

- Acceptable video calls. That's it.

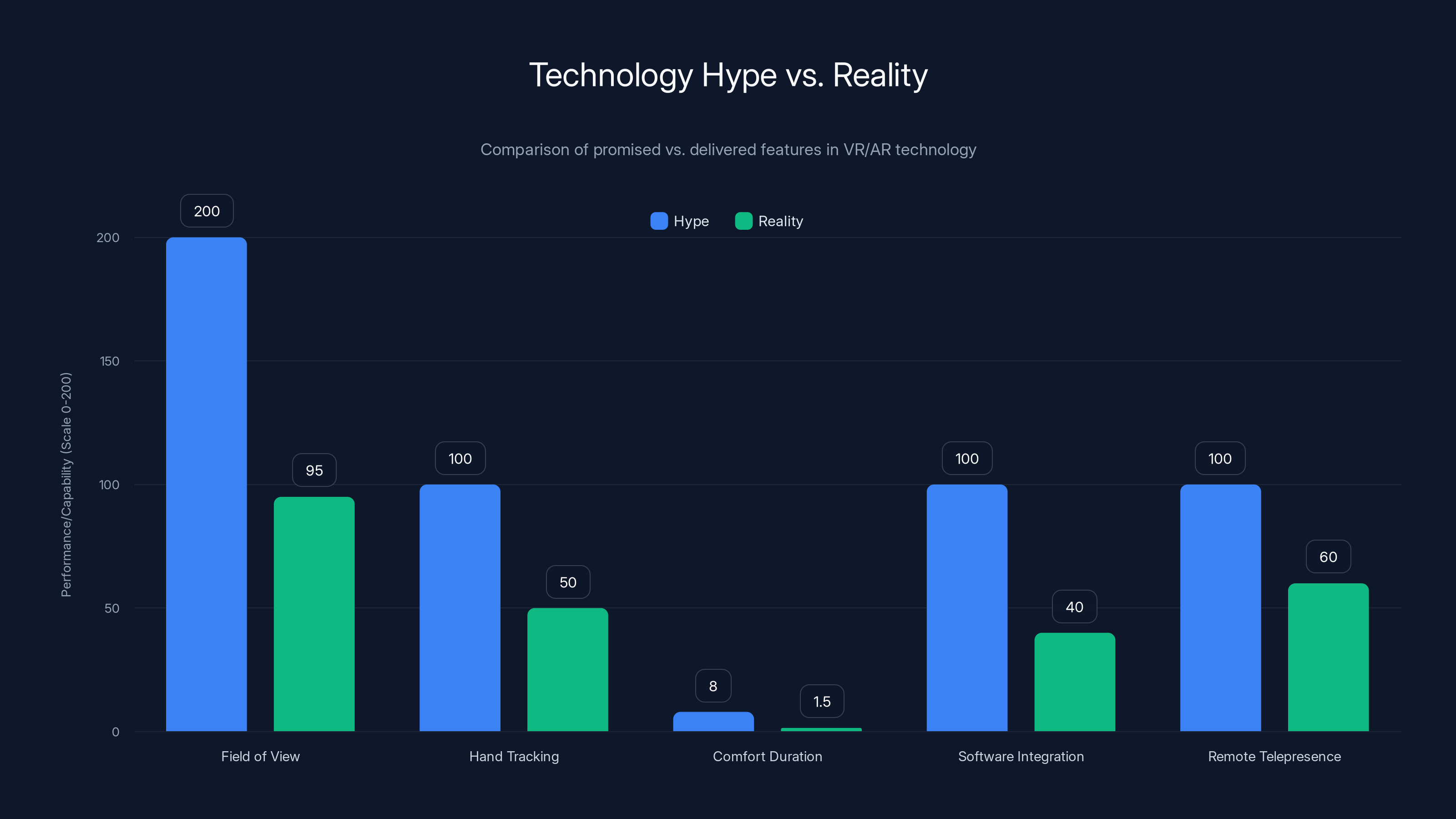

The gap between promise and reality wasn't small. It was cavernous.

Take the field of view issue as a concrete example. Human eyes have a field of view of roughly 200 degrees horizontally. Most VR headsets operated at 90-100 degrees. That's not a minor technical limitation. That's a fundamental mismatch. Workers would be staring through a porthole at their work environment. Spatial awareness became difficult. Accident risk increased. Extended use felt claustrophobic.

Then there's the motion sickness problem—something Meta and other manufacturers have been quietly dealing with for over a decade. Not everyone gets sick wearing VR headsets, but enough people do that it became a persistent friction point for enterprise adoption. A surgeon can't perform surgery while feeling nauseous. A factory worker can't safely operate machinery while disoriented. An architect can't spend eight hours in a headset if they're nauseated after two.

Comfort was another stubborn problem. VR headsets and AR headsets both put significant weight on the head and face. After 90 minutes to 2 hours, fatigue sets in. After 4 hours, most users are in actual pain. An eight-hour working day wearing one of these devices? Functionally impossible for most people.

The software integration problem was perhaps the most underrated issue. Enterprise systems don't exist in a vacuum. They're integrated with legacy databases, Windows domains, security protocols, ERP systems, and countless other tools. Getting a new platform to work with all of that infrastructure was time-consuming, expensive, and often resulted in solutions that were fragile and unreliable.

And the cost. God, the cost.

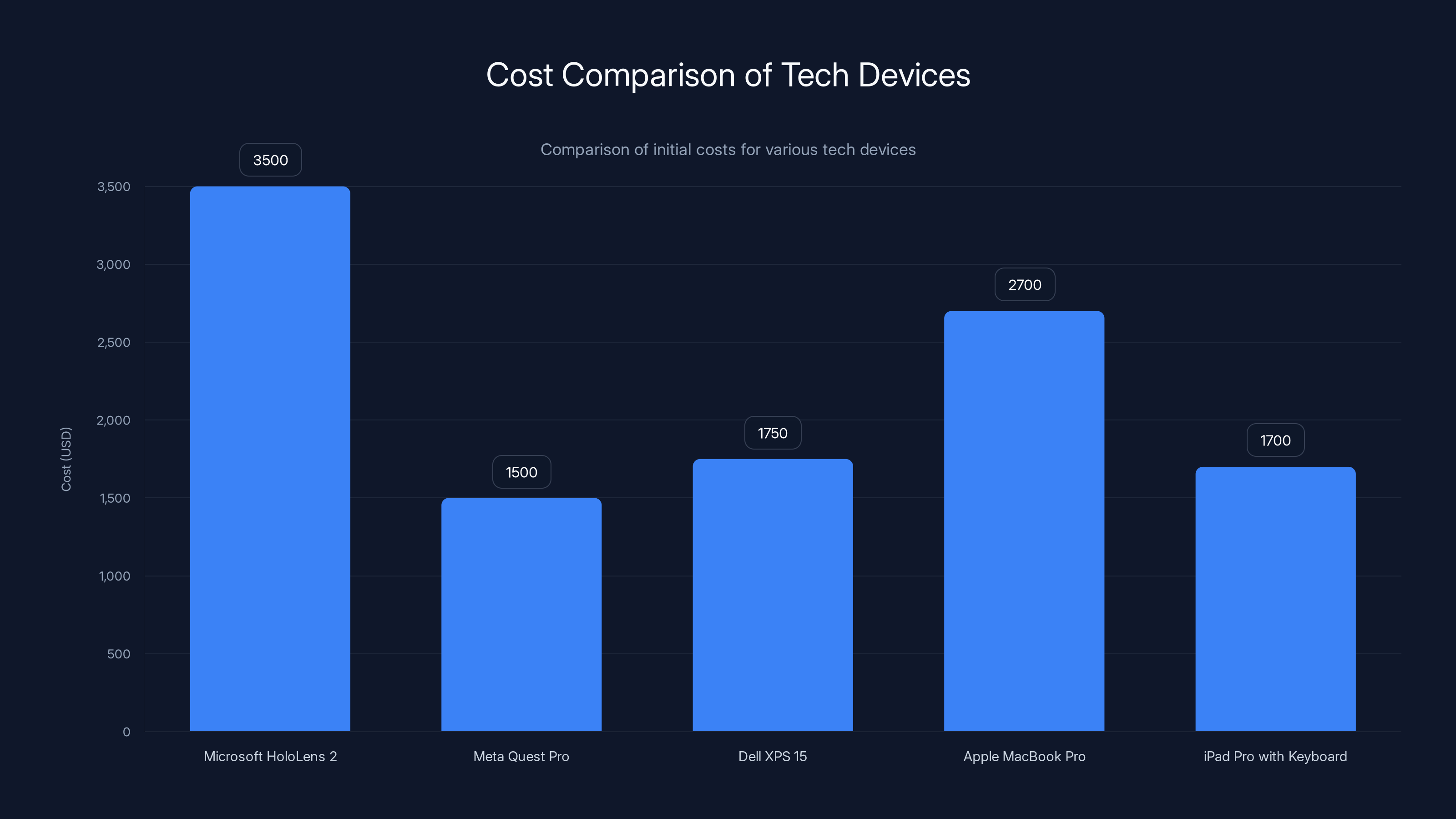

The Microsoft HoloLens 2 is the most expensive at

The Economics That Made No Sense

Let's talk numbers because that's where the failure becomes undeniable.

Microsoft Holo Lens 2 launched at **

Meta Quest Pro cost $1,500, which sounds better until you realize that's still 3-4 times the cost of a high-end laptop that could actually do real work.

For comparison: Dell XPS 15 (high-performance laptop):

You could buy professional computing equipment that has decades of software maturity, proven enterprise integration, familiar user interfaces, and actual productivity value. Or you could buy a headset that might make you nauseous and required custom development to do anything beyond watching videos.

What's remarkable is how long companies kept betting on the expensive approach. The premise was that high cost now would be justified by massive value later. That software breakthroughs would make these devices indispensable. That developers would flock to build killer enterprise applications.

None of that happened.

Developer adoption was anemic. When your installed base is measured in thousands of devices compared to smartphones' billions, monetization through free-to-play games becomes nearly impossible. The math doesn't work. You need either massive scale or high-value enterprise licenses to justify development costs. Quest never achieved the scale, and enterprise customers never came in volume.

Meanwhile, Quest unit sales remained a tiny fraction of smartphone sales. Even Xbox Series X/S—consoles that are themselves considered niche products—outsold the entire Quest ecosystem. Think about that for a moment. Microsoft's gaming console, which nobody's arguing is a mass-market phenomenon, still sold more units than Meta's years-long, heavily subsidized push into spatial computing.

The installed base was too small. The software ecosystem was too weak. The use cases didn't justify the cost. And every quarter that went by with disappointing adoption numbers made it harder to justify continued investment.

Why Immersive VR Never Worked for Business

Let me be direct here. The failure of immersive VR in enterprise wasn't really about the technology being underdeveloped. It was about the entire premise being fundamentally misaligned with how work actually happens.

Take remote collaboration. The fantasy was that VR would make remote meetings indistinguishable from in-person meetings. You'd put on a headset, appear as an avatar in a virtual boardroom, and have a completely natural interaction. You'd even be able to manipulate shared digital objects in 3D space.

Here's what actually happened: Zoom calls worked fine. Better than fine, actually. They worked everywhere. On laptops, tablets, phones. With minimal setup. No special hardware. No motion sickness. No field-of-view limitations. No training required.

Were they perfect? No. But they were good enough. They were everywhere. They had critical mass. And that last point—critical mass—mattered more than anything else.

For remote presence to work in VR, you need everyone in the meeting to be in VR. The moment one person joins via a regular video call, the whole immersive experience breaks down. You've got this uncanny valley where some people are represented as avatars and some are just video feeds in a corner. It's actually worse than just using video calls for everyone.

Risk-averse enterprises—which is to say, most enterprises—will choose the solution that requires zero buy-in from their partners, clients, and vendors. You can't force your entire supply chain to wear a headset. But you can send them a Zoom link.

There was also something almost arrogant about the entire enterprise pitch. It assumed that the primary problem with modern work was the interface. That if we just removed the screen and mouse, everything would magically improve. In reality, most knowledge work problems aren't interface problems. They're organizational problems. Unclear priorities. Poor communication. Misaligned incentives. Bad management.

Slack didn't fix those problems. But it was so useful for day-to-day communication that people adopted it anyway. Microsoft Teams succeeded not because it was better than Skype but because enterprises already had Microsoft licenses and calendars integrated with Exchange. The value came from ecosystem integration and critical mass, not from revolutionary new interfaces.

VR headsets never achieved either. They remained niche. The software never got reliable enough. And by the time hardware matured, the opportunity had shifted elsewhere.

Meta's Pivot Away From Immersive VR

Something significant happened in 2024. Meta quietly deemphasized immersive VR. The company culled VR game studios. Development slowed. Investment shifted. And the company's leadership began talking less about "the metaverse" and more about "AI-powered smart glasses."

This wasn't a minor shift. This was Meta admitting that its entire strategy—the one that justified the $2 billion Oculus acquisition, the billions more in R&D, the subsidized headsets, the developer ecosystem investments—hadn't delivered.

Look at the timeline:

- 2021-2022: Meta was all-in on immersive VR and "the metaverse." CEO Mark Zuckerberg talked about spending $5-10 billion annually on Reality Labs (the spatial computing division).

- 2023: Reality Labs losses were mounting. The Quest Pro (Meta's premium device) failed to gain traction.

- 2024: Meta abandoned the Quest Pro brand, culled studios, and pivoted toward smart glasses.

By 2025, Meta is running hard toward smart glasses with display technology from partners like Mojo Vision (after it acquired key talent) and Brillian (their internal AR display lab). The company's new narrative is about lightweight AR glasses with AI integration—something that looks more like Google Glass 2.0 than like Oculus.

The irony is sharp: Meta spent more than any company on immersive VR, and it's now abandoning it in favor of something that looks superficially similar to what Google was doing 15 years ago.

But here's the thing—Meta's learning is actually correct. The future is smart glasses, not immersive headsets. They're just arriving at that conclusion years later and billions poorer.

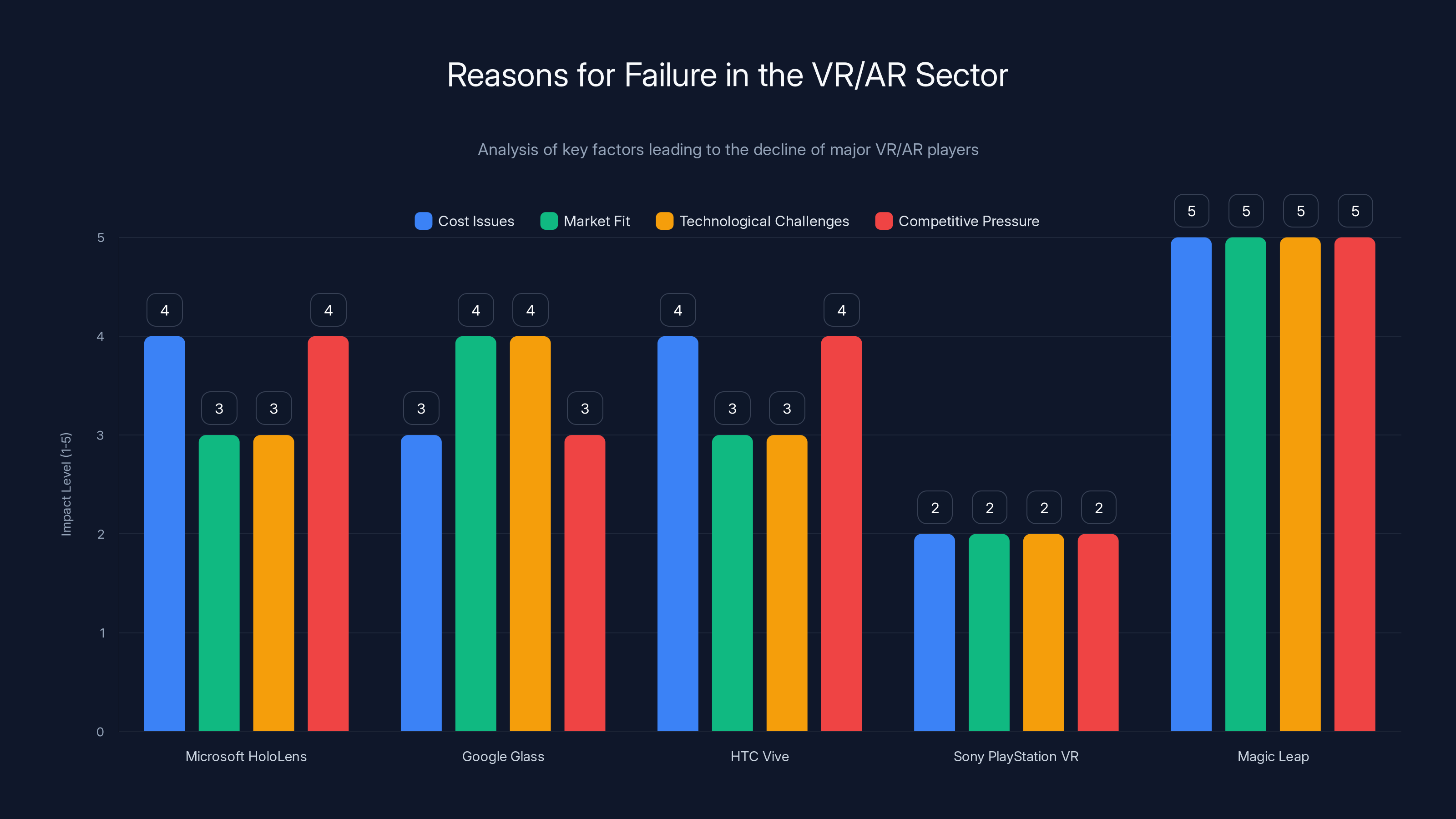

The chart highlights key factors that contributed to the failure of major VR/AR players. High costs and lack of market fit were common issues, with Magic Leap facing the highest challenges across all factors. (Estimated data)

Why Other Players Failed Too

Meta wasn't the only one who bet on immersive VR and lost. The entire sector is a graveyard.

Microsoft Holo Lens was positioned as the enterprise leader. It had government contracts. Military applications. Serious institutional backing. Holo Lens 2 was genuinely impressive hardware. But it was also expensive, required custom software development, and solved problems that most enterprises didn't actually have. In 2024, Microsoft essentially abandoned the Holo Lens roadmap, refocusing on AI integration instead.

Google Glass was ahead of its time conceptually but terrible in execution. The first version was $1,500, had terrible battery life, and raised legitimate privacy concerns (people didn't want to be recorded without knowing it). Google did a smart thing: they killed the consumer version and quietly transitioned Glass into a tool for warehouse workers and field technicians—specific use cases with high enough ROI to justify the cost. Glass is still sold today, but it's niche. Very niche.

HTC Vive tried to compete in immersive VR but couldn't match Meta's spending. The company shifted toward enterprise and professional applications but with limited success. The latest Vive headsets start at around $1,000 and have found modest adoption in specific industries (architecture visualization, engineering prototyping, medical training), but it never became mainstream.

Sony Play Station VR remains primarily a gaming device and never seriously pursued enterprise adoption. The installed base (around 5 million units total) is meaningful for gaming but irrelevant for enterprise.

Magic Leap burned through over $3 billion in venture funding and effectively disappeared. The company's vision of lightweight AR glasses was technically ahead of execution. By the time they shipped hardware, the competitive landscape had shifted, and the company couldn't find a viable market niche.

The pattern is clear: companies that bet big on immersive VR experienced diminishing returns. Companies that found specific professional niches (specialized medical imaging, industrial training, warehouse picking) achieved modest success. But nobody achieved the transformation they promised.

The Comfort and Health Issues Nobody Wanted to Talk About

One thing that rarely made it into investor presentations was the elephant in the headset: not everyone can tolerate immersive VR for extended periods.

Motion sickness affects somewhere between 25-40% of users. Not all of them, and not equally, but it's a significant portion of any population. For professional applications, this becomes a real problem. You can't ask a surgeon to operate while mildly nauseous. You can't ask a factory worker to use safety equipment that disorients them.

Even for people who don't get motion sick, extended VR use causes:

- Eye strain: The depth cues in VR don't perfectly match natural vision, causing fatigue

- Neck and shoulder pain: The weight of headsets creates sustained tension

- Facial pressure marks: After an hour, you start seeing red marks on your face

- Reduced spatial awareness: Your actual environment becomes irrelevant

- Cognitive overload: Processing a completely synthetic environment requires active attention

There's also something called VR hangover or cybersickness—lingering disorientation that can persist after you take the headset off. For some users, this lasts hours.

These aren't minor usability issues. These are hard constraints on deployment. You can't force employees to use equipment that makes them physically uncomfortable. Doing so creates liability, impacts productivity, and tanks employee satisfaction.

Companies learned this through painful pilot programs. You'd deploy 10 headsets to a department. Three people would struggle with motion sickness immediately. Two more would find them too uncomfortable for all-day use. Three would struggle with the software. And one would actually find value in them.

That 10% success rate doesn't justify the deployment. It especially doesn't justify it when you're competing against solutions (laptops, tablets, even smartphones with decent AR) that work for basically everyone.

The Software Ecosystem That Never Materialized

The dirty secret of VR is that the software ecosystem never reached critical mass. Ever.

When you're trying to build a new computing platform, you need developers. Lots of them. They need tools, APIs, documentation, and most importantly, a viable business model. You need the kinds of killer apps that make people want to buy the hardware rather than just tolerate it.

Smartphones had that. Touch interfaces, GPS, cameras, and accelerometers enabled completely new applications (Uber, Instagram, Snapchat, Pokémon Go) that simply couldn't exist on previous platforms. That drove adoption, which drove developer interest, which created more apps, which drove more adoption.

VR had... what exactly?

Games, mostly. And that's fine for consumer VR, but it's not compelling for enterprise. A factory manager doesn't buy a $3,500 headset because of better graphics on immersive games. They buy it because it solves a real business problem.

What business problems did immersive VR actually solve?

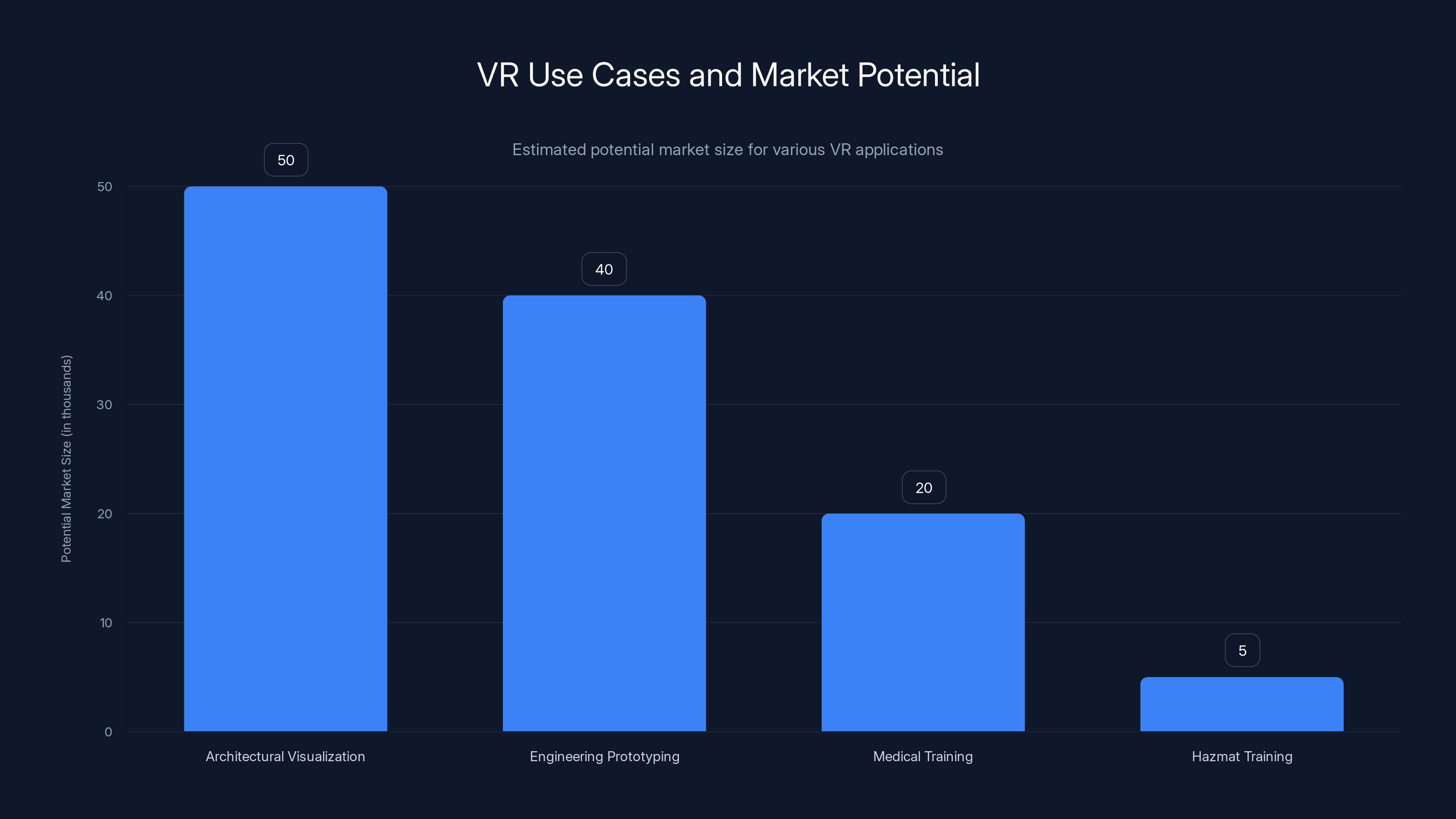

- Architectural visualization: You could walk through a 3D model of a building design before construction. Useful, but you can do similar things with non-immersive 3D viewers on screens for a fraction of the cost.

- Engineering prototyping: You could interact with large-scale 3D models. Again, useful, but not sufficiently better than a high-resolution display and mouse interface to justify the cost and complexity.

- Medical training: You could practice surgical procedures in simulation. This genuinely has value, but the market is small.

- Hazmat team training: Realistic simulation of dangerous scenarios without actual risk. Actually makes sense, but the addressable market is maybe a few thousand people globally.

None of these use cases achieved significant scale. None of them drove broad ecosystem development. The result was a vicious cycle: without a robust software ecosystem, headsets remained niche, which made development less attractive, which kept the ecosystem weak.

Compare that to Windows (which had Lotus 1-2-3 and later Office), or i OS (which had the App Store), or even Android (which had Google's ecosystem of services). Each of these had applications that made the platform valuable. VR had... okay graphics and head tracking.

That wasn't enough.

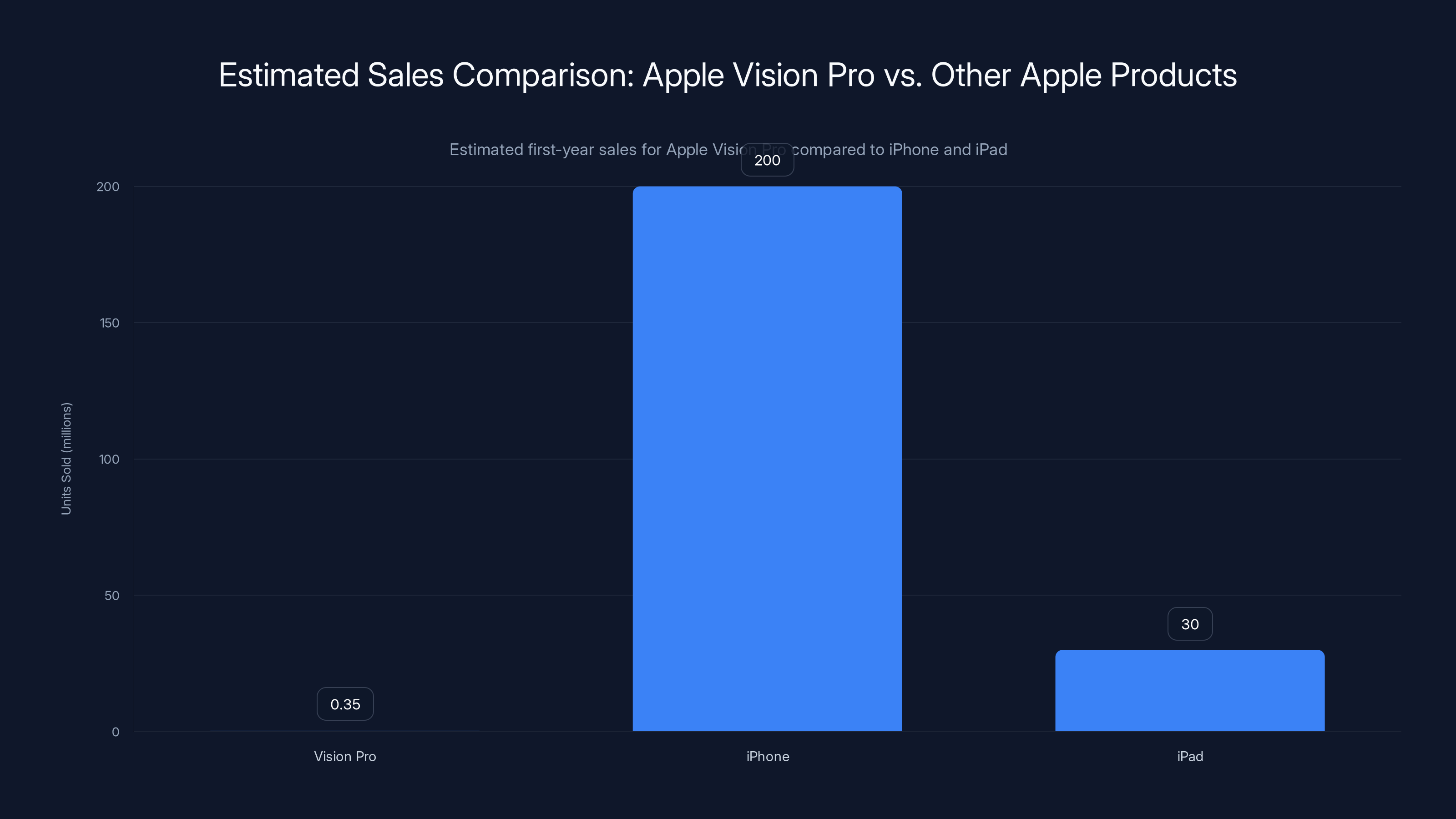

Apple Vision Pro's estimated sales are significantly lower than iPhone and iPad, highlighting its niche market status. Estimated data.

The Real Enterprise Needs VR Didn't Address

Here's something crucial: companies actually identified real problems they wanted to solve. The issue wasn't lack of motivation. It was that immersive VR wasn't actually the best solution to those problems.

Problem: Remote expertise Enterprise need: A remote expert needs to guide a technician through a complex repair without being on-site.

VR pitch: Put on a headset, see a shared 3D space, and the expert can point directly at components.

Actual solution: Augmented reality on a smartphone or tablet. The technician can hold up their phone, see the equipment through the camera, and have a remote expert annotate what they're seeing in real time. No headset required. No motion sickness. Hands free (you hold your phone). Deployed immediately. Zoom with screen sharing or similar actually works fine.

Problem: Training at scale Enterprise need: Train 10,000 employees across 50 locations on a new process, safely, without disruption to operations.

VR pitch: Give everyone a headset, show them a realistic simulation.

Actual solution: Online video training with interactive components. Way cheaper. Deployable everywhere. Doesn't require buying hardware. Employees can pause, rewatch, take notes. Just... actually do the job once with supervision.

Problem: Collaborative design Enterprise need: Architects and engineers in different cities need to collaborate on a design project in real time.

VR pitch: Put on headsets, meet in a shared virtual space, manipulate 3D objects together.

Actual solution: Zoom with screen sharing, collaborative design software (Adobe XD, Figma, Blender with network multiplayer plugins), or even just in-person meetings when it actually matters. Video + software tools > spatial immersion, especially when not everyone is in VR.

The pattern is consistent: The best solutions to enterprise problems typically involved:

- Minimal hardware requirements (so no one's excluded)

- Asynchronous capability (because distributed teams aren't always online simultaneously)

- Integration with existing tools (because enterprises don't replace their entire stack)

- Low cost of deployment (because large-scale rollouts require budget justification)

- Solutions that didn't make people physically uncomfortable (because that's a hard constraint)

Immersive VR failed on basically all of these dimensions.

The Rise of Smart Glasses (And Why They're Different)

Now here's where the narrative shifts. Smart glasses—lightweight AR glasses without the immersive headset experience—are actually a different category. And they might actually work.

Consider Google Glass again. The original Glass failed as a consumer product, but the underlying concept was sound: a lightweight device on your head that could display information and handle basic AR without requiring you to hold anything or stare at a screen.

The problems with original Glass were:

- Massive privacy concerns: People didn't like being recorded

- Limited battery life: About 4 hours

- Awkward form factor: It looked ridiculous

- Weak software ecosystem: Glass Explore didn't offer compelling apps

- High cost: $1,500 was prohibitive

But Glass for business—specifically Glass Enterprise Edition for warehouse workers, field technicians, and logistics teams—actually worked. Why? Because:

- Clear value proposition: Show a worker their next task, highlight items to pick, display instructions

- Hands-free operation: Workers kept both hands available for actual work

- Practical information display: Not immersion, just relevant data when needed

- Low training burden: It's a display device, not a new interface paradigm

- Targeted market: Deploy to the people who actually benefit, not everyone

That's the key insight. Smart glasses aren't trying to replace your computer. They're trying to augment your view of the real world with relevant information. That's a fundamentally different pitch than immersive VR, which wanted to replace the real world.

In 2024-2025, we're seeing a wave of new smart glasses companies and initiatives:

- Meta's internal AR glasses project (codename unknown, but the company is definitely building them)

- Google Android XR: An OS specifically designed for AR glasses

- Xreal Air: Lightweight AR glasses with app ecosystem integration

- Snap Spectacles: Snapchat's glasses offering (limited but functional)

- Various startups working on lighter, more practical AR glasses

The key differentiator with many of these is weight and comfort. A pair of smart glasses that weighs 80-100 grams and looks like regular glasses can be worn all day without issues. You're not strapping a heavy helmet to your head. You're just wearing glasses.

Battery life is still challenging (typically 2-4 hours per charge), but that's workable for specific use cases. All-day wearability is the goal of the next generation.

Android XR and the Multi-Manufacturer Approach

Here's the move that could actually change things: Google licensing Android XR to multiple manufacturers.

Remember what I said earlier about Google buying Android? The key was that Google couldn't lock manufacturers into using only Google apps. Instead, Google opened it up. Anyone could build an Android phone. That fragmentation was a feature, not a bug, because it meant the platform reached critical mass.

Google's apparently applying the same logic to AR glasses. Android XR is an operating system designed from the ground up for lightweight AR glasses. Instead of one company (say, Meta or Apple) controlling the device ecosystem, multiple manufacturers can build their own glasses running Android XR.

Who's interested? Dell, HP, Lenovo, Asus, Acer. All the PC manufacturers who got burned on Windows Mixed Reality but still see opportunity in AR glasses for professional users.

Here's why this matters: These are companies that have existing relationships with enterprise customers. They understand the channel. They have sales teams and support infrastructure already in place. They're not starting from scratch trying to convince businesses to buy into a new ecosystem.

If Dell releases Android XR glasses that integrate with Windows PCs, that's automatically relevant to millions of enterprise customers already in the Dell ecosystem. If HP does the same, suddenly you've got professional AR glasses from manufacturers businesses already trust.

This approach also sidesteps one of Meta's core problems: Meta isn't an enterprise-focused company. The company's culture, sales organization, and support infrastructure are built around consumers and SMBs. Getting Meta to develop products for serious enterprise customers is like asking a sports car company to build bulldozers. They can technically do it, but their incentives are misaligned.

PC manufacturers, on the other hand, exist to sell to enterprises. It's their entire business model. They might actually figure out how to build AR glasses that enterprises actually want.

The chart illustrates the significant gap between the hyped capabilities and the actual performance of VR/AR technologies. Estimated data highlights the stark contrast, especially in field of view and comfort duration.

Why Apple Vision Pro Doesn't Change This Story

I should address the elephant in the room: Apple Vision Pro.

Apple released Vision Pro in early 2024 as a spatial computing device that blurs the line between VR and AR. It's expensive ($3,500+), powerful, and technically impressive. It's also... not selling.

Apple's not publicly releasing sales figures, but analysts estimate somewhere between 200,000 and 500,000 units sold in the first year. For Apple, in a premium category, that's... not great. For comparison, i Phone sells 200+ million units annually. Even i Pad sells 20-40 million. Vision Pro is running at maybe 0.2% of i Phone volumes.

The reason is straightforward: Vision Pro is a luxury product with limited practical value outside of specific professional niches (architectural visualization, medical training) and personal use cases (watching movies in a virtual theater, which sounds cool until you realize you're paying

Vision Pro didn't fail because it's poorly designed. It failed because the entire category is still struggling to find compelling use cases. Vision Pro is just more expensive and better engineered than competitors.

Apple's bet is that as time passes, developers will build actual applications that make the hardware valuable. That might happen. But it's happening slowly, and in the meantime, Vision Pro remains a niche curiosity for wealthy early adopters and professionals with specific needs.

Meanwhile, smart glasses are quietly becoming practical. Not glamorous. Not immersive. Just useful.

The Future: Smart Glasses + AI > Immersive VR

If you want to understand where spatial computing is actually heading, look at what's happening with AI integration in AR glasses.

Companies are working on smart glasses that can:

- Recognize objects: Point your glasses at something, and the AI identifies it

- Translate text: See a sign in another language, get instant translation overlaid

- Provide contextual information: Look at a person, get relevant information (name, context, relevant notes)

- Guide technical work: Tell you exactly what components to replace and in what order

- Safety alerting: Warn you about hazards in your environment

None of this requires you to be "in" an immersive virtual environment. It just requires a pair of glasses that can display information overlaid on your real-world view.

The combination of lightweight AR hardware + AI processing is actually powerful. It's not flashy. You're not stepping into the metaverse. But it actually solves problems. It actually improves workflows. It actually has ROI.

And that's the key difference. Immersive VR was sold on the promise of transformation. "This will change how work happens." Smart glasses + AI is sold on the promise of incremental improvement. "This will make your job slightly easier." That's a lower bar. It's easier to meet. And it's actually more valuable because it doesn't require massive behavioral change.

Why Immersive VR Will Remain Niche

Let me be clear about something: immersive VR isn't going away. It will continue to exist. It will find use cases. But it will always be niche.

Specialized training, high-end visualization, entertainment, gaming—these applications will continue. Some companies will continue to invest. Some devices will continue to ship. But the vision of immersive VR replacing desktop computing or becoming a general-purpose platform? That's dead. Completely dead.

The reasons are structural:

- Health constraints: Motion sickness and discomfort are hard limits, not just inconveniences

- Isolation: Full immersion requires disconnection from your actual environment, which is problematic in most work contexts

- Social friction: You can't make eye contact, read facial expressions, or feel like part of a shared physical space

- Cost: High enough to require serious ROI justification, but not high enough to become ubiquitous

- Installed base: Without critical mass, software ecosystem growth stalls

- Competing solutions: Lighter, cheaper, less demanding technologies (smart glasses, regular displays) solve most of the same problems

Bit by bit, the reasons to choose immersive VR just... shrink.

Estimated data shows that none of the VR use cases reached a significant market size, limiting the development of a broader software ecosystem.

The Enterprise VR Graveyards: What Happened to All That Deployment?

One interesting question: What happened to all the immersive VR headsets that were deployed in enterprise settings?

Some are still in use, but in significantly reduced numbers. Many are sitting in closets. Some were returned to manufacturers. Some found secondary markets with hobbyists and enthusiasts.

The companies that deployed them learned expensive lessons:

- Don't invest heavily without proven use cases: Pilots might work, but that doesn't mean scaled deployment will work

- Training costs are higher than expected: People need significant onboarding to be comfortable with VR

- Maintenance is a pain: Headsets break, need firmware updates, require technical support

- Adoption rates are lower than projected: You always get fewer people actually using the devices than you planned

- ROI is elusive: Even when there's a theoretical benefit, proving it financially is tough

These lessons are now embedded in enterprise purchasing behavior. VR vendors struggle to get budget because budget holders remember failed pilots.

What Gets Funded Going Forward

Investor interest in spatial computing hasn't disappeared. It's just redirected.

Capital is flowing toward:

- AI-powered AR glasses: Lightweight, practical, clear use cases

- Software for AR applications: Building the ecosystem without betting on hardware

- Specialized industrial AR: Focused solutions for specific verticals (manufacturing, healthcare, field service)

- Consumer AR on existing devices: Using smartphone cameras to augment reality

- VR for entertainment and games: Where ROI is clearer and addressable market is larger

What's not getting funded: Expensive immersive headsets promising to replace computing platforms. Those days are over.

The Meta Lesson: What Happens When You Bet Wrong

Reality Labs, Meta's spatial computing division, is estimated to have lost over $20 billion cumulatively from 2020 through 2024. That's not hyperbole. That's actually what the math suggests based on Meta's disclosed Reality Labs losses.

What did that $20 billion buy Meta?

- Some impressive engineering talent: These people will eventually make useful AR glasses

- A first-mover disadvantage: Meta got to all the dead ends before competitors

- Institutional knowledge about what doesn't work: Actually valuable

- A pivot opportunity: Because they failed spectacularly, Meta can now try something different

But it didn't buy Meta a platform. It didn't buy them dominance in spatial computing. It didn't buy them the escape hatch from Apple and Google's smartphone duopoly.

For all that investment, Meta is now in a position where it has to watch PC manufacturers and Google potentially define the AR glasses market. That's not a great outcome for Meta.

The lesson for other companies? Be more skeptical. Demand proof of concept. Require actual use cases. Don't bet the company on transformative technology that hasn't proven itself yet.

Specific Vertical Where VR Actually Works (Briefly)

Let me acknowledge: there are genuine use cases where immersive VR has stuck around. I should be fair about this.

Medical training: Surgical simulation is a legitimate application. Practicing complex procedures in a risk-free environment has real value. Some medical schools have integrated VR into their curriculum. This is a small market (maybe thousands of institutions globally), but it's real.

Hazmat and dangerous environment training: Practicing responses to hazardous scenarios without actual risk is genuinely valuable. Chemical spill response, radiation handling, confined space rescue—these are situations where simulation provides real safety benefits.

Industrial equipment design and visualization: Companies like Boeing and Airbus use VR for visualizing complex assemblies and identifying problems before manufacturing. This has worked because the cost is justified by the massive cost of manufacturing errors.

Luxury real estate visualization: Showing prospects what a property will look like before it's built can be useful. Not essential, but nice to have.

Gaming and entertainment: This is where VR is actually most healthy. Gaming VR remains niche but stable. People enjoy immersive games enough to justify standalone headsets or PSVR setups.

These aren't trivial markets. But they're not general-purpose platforms. They're vertical applications where immersive VR provides specific value. And that's fine. Not everything needs to be a general platform.

The Competitive Dynamics Going Forward

Assuming smart glasses do become viable, here's how the competitive landscape looks:

Google's position: Strong. Android XR gives Google a way to participate in the AR glasses market without building all the hardware themselves. Multiple manufacturers means multiple product lines at different price points. Google's leverage is their OS and their AI services.

Meta's position: Confused. Meta wants to participate but doesn't have a clear path. Building glasses but also licensing technology? The narrative is unclear.

Apple's position: Expensive and exclusive. Vision Pro is a luxury product that will likely remain niche. Apple might eventually release lighter AR glasses, but that's years away.

Microsoft's position: Focused on enterprise with Azure and Copilot integration. Windows + enterprise AR is a real angle that other companies will struggle to compete with.

Chinese manufacturers: Likely to dominate on cost. Xreal is already shipping lightweight AR glasses at reasonable prices. Other Chinese manufacturers will follow. Quality and ecosystem are weaker, but price matters for adoption.

The most likely scenario: Multiple product lines from different manufacturers, varying price points and capabilities, creating actual competition instead of single-player dominance.

That's actually better for everyone—better for customers who get choice, better for enterprises who get competitive pricing, better for developers who have multiple platforms to target.

Honest Assessment: The Next 5 Years

Here's what I actually think is going to happen between now and 2030:

Smart glasses will ship from multiple manufacturers. They'll get lighter, brighter, and more capable. Battery life will improve. Some will find real value in specific verticals: field service, healthcare, military, manufacturing. Early adoption will happen. ROI will be demonstrated in those areas.

But mass adoption won't happen. AR glasses will remain specialized tools, like robotic exoskeletons or drone platforms. Useful for specific work, but not essential for general computing.

Gaming will continue in VR but remain niche. The idea of a VR metaverse where everyone hangs out as avatars? That's not happening. Ever, probably. It's a fundamentally unfun vision that nobody actually wants.

Companies will stop promising transformative change with VR/AR. They'll be more honest about limitations. Pitch will shift from "this will replace traditional computing" to "this makes this specific task 15% more efficient."

Capital will continue flowing into the space, but at lower levels and with higher ROI requirements.

Apple will likely release a lighter version of Vision Pro or a separate AR glasses product. This will get significant press coverage. Adoption will be modest.

Google's Android XR approach will likely be more successful than Apple's closed ecosystem, but success is a relative term. "More successful" might mean 10 million units globally by 2030 instead of 5 million.

And Meta? Meta will continue building AR glasses but will never regain the market leadership position it imagined when it spent $2 billion on Oculus.

FAQ

What exactly happened to Meta's immersive VR strategy?

Meta invested heavily in immersive VR technology and the ecosystem around it, spending an estimated $15-20+ billion to develop headsets, fund developers, and subsidize hardware pricing to achieve scale. Despite these efforts, adoption remained limited due to comfort issues, high cost, limited software, and lack of compelling business use cases. By 2024, Meta shifted its focus to lightweight AR smart glasses instead, acknowledging that immersive VR never achieved the transformative potential it promised.

Why didn't Microsoft Holo Lens succeed in enterprise?

Holo Lens 2 was technically impressive but came with significant challenges: it cost $3,500 per unit, required months of custom software development to integrate with existing systems, had a narrow field of view, and could only be worn comfortably for 1-2 hours. Most enterprises found that traditional computing solutions (laptops, tablets, software) solved their problems more cost-effectively. Additionally, remote collaboration—one of Holo Lens's proposed strengths—was better served by video conferencing solutions like Zoom that required no special hardware.

What's the difference between immersive VR headsets and smart glasses for AR?

Immersive VR headsets fully replace your visual input with a synthetic environment, typically optimized for entertainment and specialized training. Smart glasses display information overlaid on your real-world view while keeping you aware of your actual surroundings, hands, and other people. Immersive VR requires full commitment (put it on, disconnect from reality), while AR glasses augment without demanding isolation. Smart glasses are lighter, less uncomfortable, and more practical for continuous workplace use.

Is immersive VR completely dead for business?

No, but it's permanently niche. Immersive VR remains valuable for specific use cases: surgical training, hazmat simulation, dangerous environment preparation, complex equipment visualization, and gaming. However, it will never become a general-purpose business computing platform. The barriers (cost, comfort, motion sickness, isolation from real-world context) are structural, not technical. What's dead is the dream of immersive VR replacing traditional computing or becoming ubiquitous.

What is Android XR and why does it matter?

Android XR is Google's operating system designed specifically for lightweight AR smart glasses. Instead of one manufacturer controlling the entire ecosystem (like Meta with Quest), Google is licensing Android XR to multiple manufacturers (Dell, HP, Lenovo, Asus) who can build their own AR glasses. This approach mirrors Google's successful Android smartphone strategy—fragmentation across manufacturers drives adoption and creates competitive pricing. Multiple manufacturers means professional AR glasses tailored to different use cases and price points.

Will smart glasses actually replace smartphones?

Unlikely. Smart glasses will augment smartphones for specific tasks (quick information lookup, navigation, remote collaboration), but smartphones offer better screen real estate, battery life, and form factor for most computing tasks. The most realistic scenario is that AR glasses become specialized tools for field workers, healthcare professionals, and other verticals where heads-up, hands-free information display provides clear value, while smartphones remain the primary personal computing device.

How much money did Meta waste on immersive VR?

Meta's Reality Labs division disclosed losses of approximately

Why did Google Glass fail when AR glasses are now supposedly the future?

Original Google Glass (2013-2015) failed due to: extremely high cost ($1,500), terrible battery life (4 hours), awkward form factor, legitimate privacy concerns (people didn't want to be recorded), and a weak software ecosystem with no killer apps. Modern AR glasses are addressing these through better design, longer battery, clearer value propositions, and stronger software. Google Glass Enterprise Edition for warehouse workers actually succeeded, proving the concept works when targeted correctly. The failure of consumer Glass doesn't contradict the future potential of AR glasses—it just showed that general consumers didn't want it, but professionals with specific use cases do.

What about the Apple Vision Pro? Isn't that proving VR demand?

Apple Vision Pro is a spatial computing device (somewhere between immersive VR and AR) that's struggled to find mainstream adoption. Estimates suggest 200,000-500,000 units sold in the first year—which for Apple is extremely disappointing (i Phone sells 200+ million annually). Vision Pro is expensive ($3,500+) and lacks compelling apps beyond novelty applications and media consumption. Vision Pro hasn't proven VR demand; it's actually demonstrated that even Apple's design and marketing can't overcome the fundamental issues with immersive headsets being uncomfortable, isolating, and solving problems people don't have.

Conclusion: The Real Future of Spatial Computing

Here's the brutal truth nobody wanted to hear: the golden age of immersive VR never actually arrived. There was an imagined golden age—a future that everyone hoped for but never materialized. The technology matured. The investment flowed. But the compelling use cases never came. The economics never worked. The adoption never happened.

What we got instead was expensive hardware with motion sickness, comfort issues, and software that required months to integrate with existing systems. What we expected was transformative platforms that would replace traditional computing. The gap between those two things killed the dream.

But spatial computing itself isn't dead. It's just migrating. Not toward full-immersion headsets that isolate you from the world. Toward lightweight smart glasses that augment your view of the world with relevant information. Toward AI-assisted interfaces that understand context. Toward practical tools that solve specific problems without demanding behavioral revolution.

Google's Android XR approach—licensing the platform to multiple manufacturers rather than controlling the ecosystem—might actually be the path that works. Dell, HP, Lenovo, and other PC makers know how to sell to enterprises. They have existing relationships. They understand the channel. They might actually figure out how to build AR glasses that businesses want.

Meta learned an expensive lesson: platform dominance through scale and subsidy works for smartphones but not for products that make people nauseous and uncomfortable. The $20 billion investment bought Meta knowledge but not market control. Now the company is pivoting—building smart glasses instead, likely following the same path that everyone else is walking.

Apple released Vision Pro as a luxury spatial computing device. It's technically impressive and financially irrelevant. Niche products can be profitable, but they don't define markets.

The most interesting thing happening right now is happening quietly. Smart glasses are getting lighter. AI capabilities are improving. Integration with existing computing infrastructure is becoming easier. Price points are falling. Multiple manufacturers are entering the market instead of waiting for one company to define the category.

That's the story of spatial computing's actual future. Not immersive. Not transformative. Just practical, useful, and incrementally better.

Immersive VR's golden age is indeed over. It's just that there wasn't actually much gold there. The real value is elsewhere, in technologies that don't require you to strap on a heavy headset and disconnect from the world.

Watch what Google does with Android XR. Watch what Dell and HP build on that platform. Watch what actually gets deployed in field service, healthcare, and manufacturing. That's where spatial computing's real future lives.

Key Takeaways

- Meta invested $20+ billion in immersive VR and achieved minimal market traction, forcing a pivot toward smart glasses by 2024

- Structural barriers (motion sickness, 25-40% of users affected; comfort limitations under 2 hours; narrow 90-100 degree field of view) prevented all-day workplace adoption

- Immersive VR never solved compelling business problems that weren't better served by existing solutions like Zoom, laptops, or tablets at lower cost

- Google's Android XR multi-manufacturer licensing approach may succeed where single-vendor ecosystem (Meta, Apple, Microsoft) failed, by enabling PC makers already trusted by enterprises

- Smart glasses augmenting reality with AI are the practical future, not full-immersion headsets—lightweight, hands-free information display solves real workplace problems

Related Articles

- YouTube's Vision Pro App Changes Everything for Spatial Video [2025]

- Best VR Accessories for 2026: Complete Guide [2026]

- RayNeo Air 3s Pro Smart Glasses Review [2025]

- The Smart Glasses Revolution: Why Tech Giants Are All In [2025]

- Snap's AR Glasses Spinoff: What Specs Inc Means for the Future [2025]

- Snap's Specs Subsidiary: The Bold AR Glasses Bet [2025]

![Why VR's Golden Age is Over (And What Comes Next) [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/why-vr-s-golden-age-is-over-and-what-comes-next-2025/image-1-1771061826145.jpg)