Why We're Nostalgic for 2016: The Internet Before AI Slop

There's a strange phenomenon happening across social media right now. Instagram's "add yours" stickers are flooded with throwback photos from 2016. Spotify user-generated playlists tagged "2016" have surged 790% since January 2025. TikTok, Reddit, and X are drowning in calls for a cultural reset back to that specific year. Millions of people are collectively agreeing on something rare: we miss 2016.

The irony is sharp. In 2016, people hated that year. They called it cursed. A Slate columnist genuinely asked whether 2016 was worse than 1348 (the Black Death) or 1943 (the Holocaust). Twitter was an anxiety machine. News cycles moved at a pace that felt catastrophic. The Pulse nightclub shooting, the Syrian Civil War, the Zika virus, Brexit, and a U.S. presidential election that felt like watching democracy fail in real-time. People made memes about the devil having an assignment due January 1, 2017, and cramming all his chaos into those twelve months.

But here's what's wild: we weren't actually nostalgic for 2016. We're nostalgic for the internet as it existed in 2016.

There's a crucial difference. And understanding that difference reveals something uncomfortable about how the internet has decayed in less than a decade.

The Internet Actually Worked Back Then

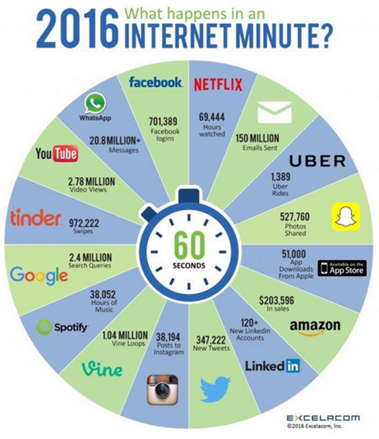

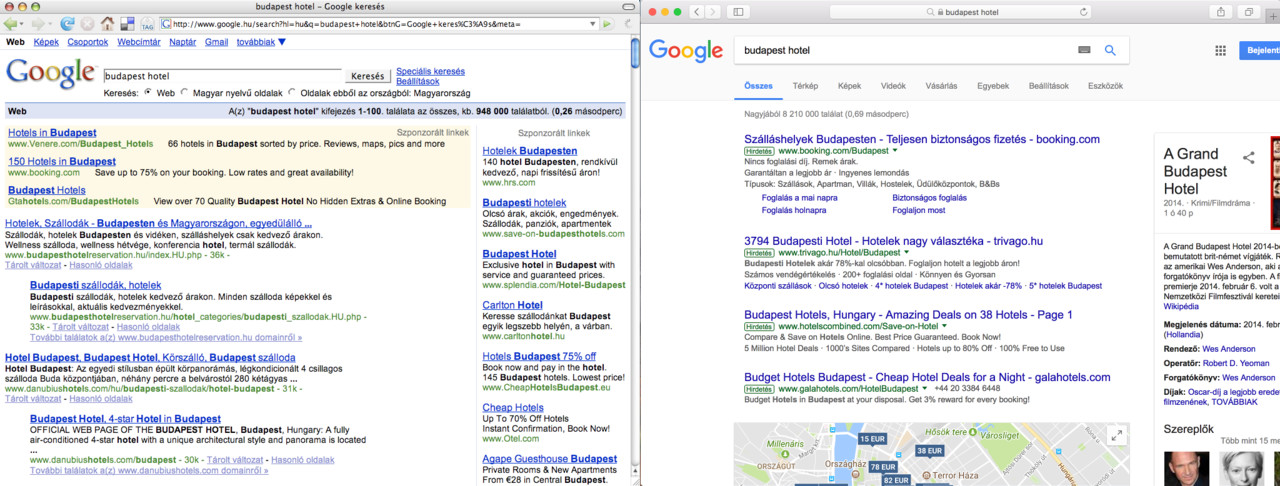

In 2016, Google search results were actually useful. You could type a question and get answers that appeared in roughly this order: directly relevant results, semi-relevant results, and then slowly degrading relevance. It wasn't perfect, but it functioned.

Today, searching Google means navigating past multiple AI-generated summaries that half-answer your question, sponsored results disguised as organic answers, and content farms optimized entirely for search algorithms rather than human comprehension. The first meaningful result might appear on page three. This isn't hyperbole. Search result quality has demonstrably declined as SEO optimization and AI content generation have become the dominant strategy for online visibility.

Twitter in 2016 was chaotic, but it was human chaos. You saw tweets from people you followed. The chronological feed meant you could keep up with conversations. Discourse was ugly, but it was legible. You knew what people were actually saying.

Now, every platform employs algorithmic feeds designed to maximize engagement time through rage amplification and content fragmentation. Your feed shows you what the algorithm predicts will keep you scrolling, not what the people you follow are actually posting. The algorithm learned that conflict, outrage, and divisive content keep users engaged longer than genuine connection. So that's what it serves you. All day. Every day. This isn't a conspiracy. It's literally the business model, as highlighted in a detailed analysis by Pune Mirror.

Instagram in 2016 was still primarily a photo-sharing app. You scrolled through images from people you chose to follow. There were no AI recommendations, no suggested content from strangers, no algorithmic ranking of feeds. You saw what you subscribed to. Revolutionary.

There's also a practical element people forget: the internet was slower in 2016, but that actually improved quality. Bandwidth limitations meant that only content people genuinely wanted to share got uploaded. Photos had to be edited thoughtfully. Videos required real effort. Noise was naturally filtered by friction. Now, anyone can generate infinitely reproducible content with zero effort, and platforms distribute it at algorithmic scale.

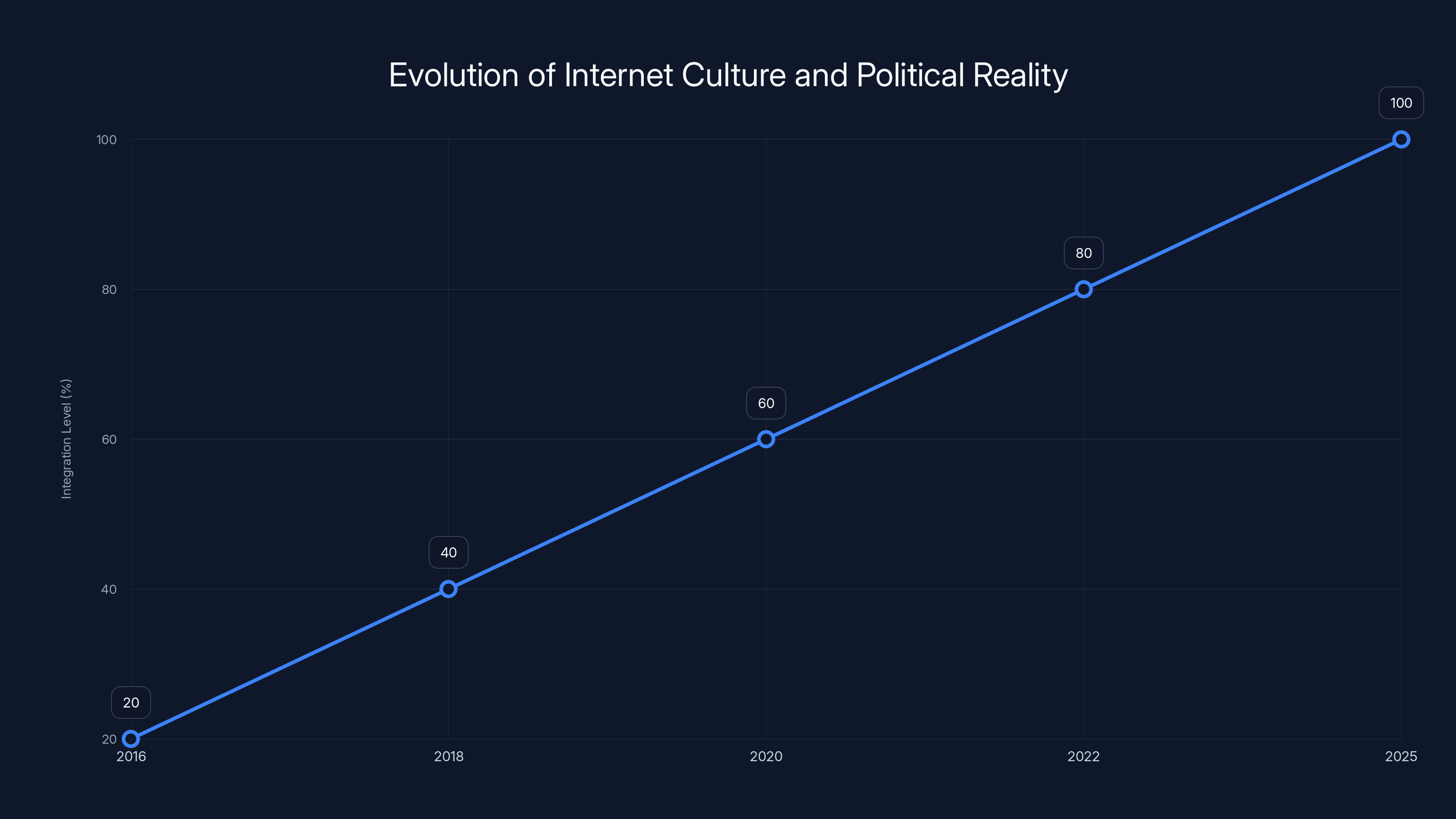

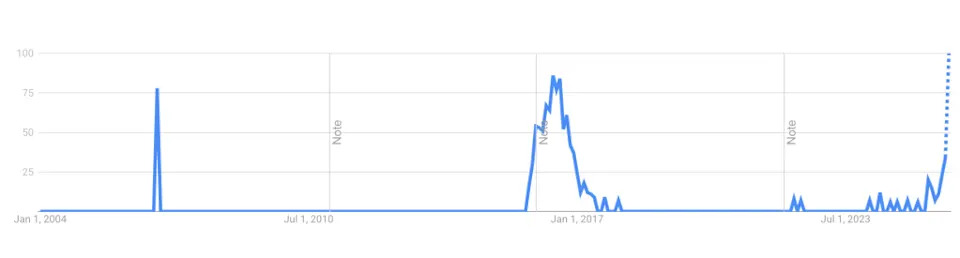

Estimated data shows a progressive integration of internet culture with political reality, reaching full integration by 2025.

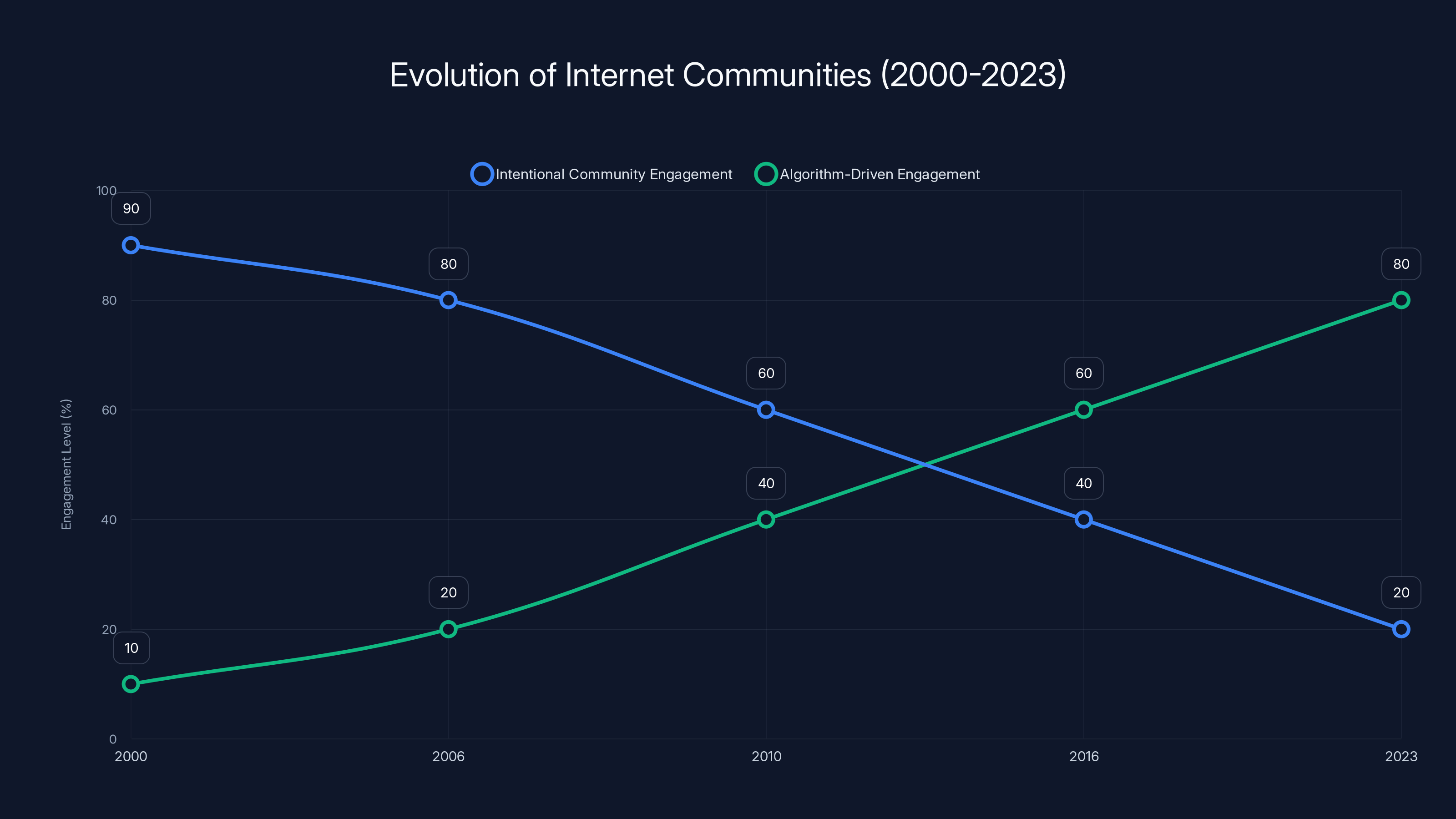

The Pre-Algorithm Internet Had Real Communities

Amanda Brennan is a meme librarian and internet historian. When asked about 2016, she frames it as a ten-year anniversary of 2006, the moment when social platforms first cemented themselves into culture. In 2006, Twitter launched, Google acquired YouTube, and Facebook opened to anyone over 13.

Before that? The internet was something different. It was a place where people went intentionally to find community. You didn't stumble into forums by algorithmic recommendation. You searched for them. You joined communities based on shared interests, and those communities had real structure. There were moderators, norms, written rules, and a sense of belonging. Being online required effort and intention.

Brennan describes the pre-social-internet as inhabited by people who were, as she puts it, "for lack of a better term, nerdy." They were there by choice, seeking connection with other people who shared their obsessions. The barrier between internet culture and mainstream culture was high. You couldn't accidentally become part of online culture. You had to actively search for it.

By 2016, that barrier had eroded substantially. Your parents were on Facebook. Your coworkers were on Instagram. Your grandmother had a Twitter account. The internet had leaked into everything. But the transition hadn't yet reached its conclusion. Communities still existed. Niche internet spaces still felt somewhat protected. You could still find weird, ungoverned spaces where people who genuinely wanted to be there gathered.

Now? Every community is algorithmically ranked, moderated by AI, and optimized for engagement metrics. Real community requires friction—the friction of having to care enough to be there, of shared norms enforced by the community itself, of consequence for violating community standards. Algorithmic platforms eliminated friction. They optimized for growth. And in doing so, they destroyed the actual community structure that made the internet feel like somewhere, not just something.

Estimated data shows a decline in intentional community engagement as algorithm-driven platforms rise, highlighting the shift in how online communities are formed and maintained.

When Everyone Became an Internet Person

Here's the trap: we didn't want the internet to be exclusive. We wanted everyone to have access to online communities, to information, to connection. That was always the dream. But in achieving mass adoption, we didn't upgrade the technology to handle it. We downgraded the experience to make it profitable.

The moment phones became ubiquitous, around 2012-2016, the internet changed fundamentally. Everyone could access it constantly. But platforms couldn't have everyone in a real community. Real communities cap out around 150 people (Dunbar's number). They require active participation and enforcement. They don't scale infinitely.

So platforms invented the algorithm. The algorithm could theoretically serve infinite people simultaneously. But algorithms optimize for a single metric: engagement time. And engagement time is maximized not by serving communities, but by serving conflict, outrage, viral content, and infinite novelty.

By 2016, this transition was already in motion, but it wasn't yet total. Facebook's algorithm existed, but it hadn't fully replaced human-curated feeds. Instagram still prioritized followed accounts. Twitter still had a mostly chronological feed. You could still see what people you knew were actually doing, alongside algorithmic recommendations.

Now, the algorithm is the product. You're not a customer of social media platforms. You're the raw material being sold to advertisers. Your attention and your emotional reactions are the commodity. The algorithm is optimized to extract maximum attention and engagement, regardless of impact on your mental health, your information diet, or the quality of your relationships.

The Great Content Decay: From Curation to Generation

In 2016, there was a real distinction between professional content creators and regular users. A YouTuber spent hours editing videos. A blogger spent days researching posts. An Instagrammer thoughtfully curated their feed. There was friction. There was intentionality.

There was also gatekeeping. You needed equipment, skills, or platform access to create at scale. This wasn't entirely good—it excluded people. But it also meant that online content had a signal-to-noise ratio that, while imperfect, remained navigable.

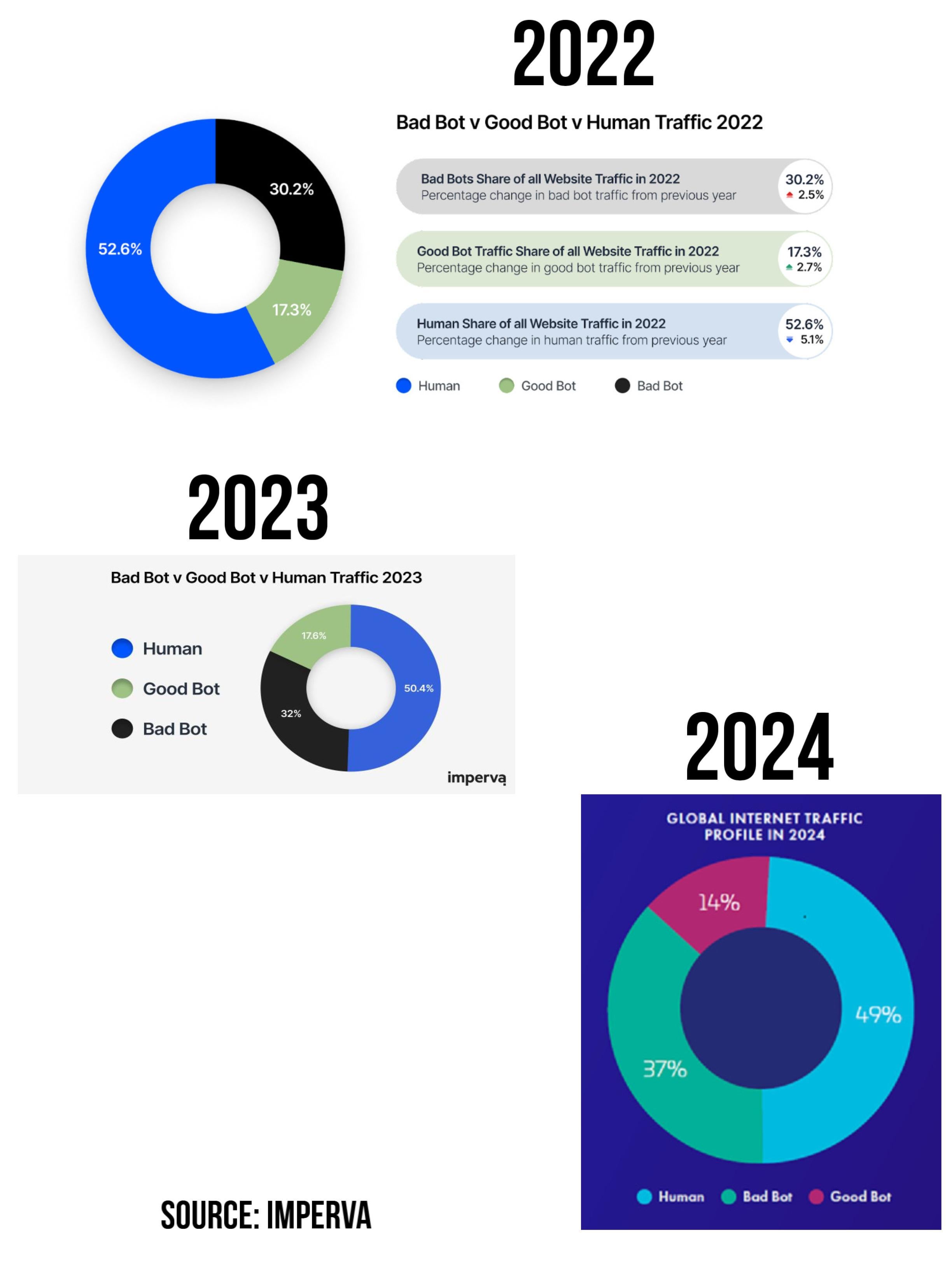

Now, artificial intelligence can generate passable content infinitely and essentially for free. A startup can create thousands of AI-written blog posts in minutes. A creator can generate unlimited Instagram captions, video scripts, and social media content without thinking. The barrier to entry has dissolved.

The result? Every platform is flooded with content that's technically functional but emotionally inert. It's optimized for algorithmic distribution, not human comprehension. It answers the question your search algorithm thinks you asked, not the question you actually wanted answered. It's "correct" in the way that a mid-tier AI model is correct: technically accurate but soulless, generic, and optimized entirely for metrics.

This is what people mean by "slop." Not plagiarism. Not technically wrong. Just the overwhelming flood of AI-generated, algorithm-optimized, emotionally inert content that has replaced human-created work across the internet.

In 2016, if you wanted to watch someone explain how to fix your car, you could find a fifteen-minute YouTube video where an actual mechanic walked through the process. Now, you get a five-minute AI-generated video that technically explains the steps but misses the nuance, the common mistakes, and the real-world context that made the old video actually useful.

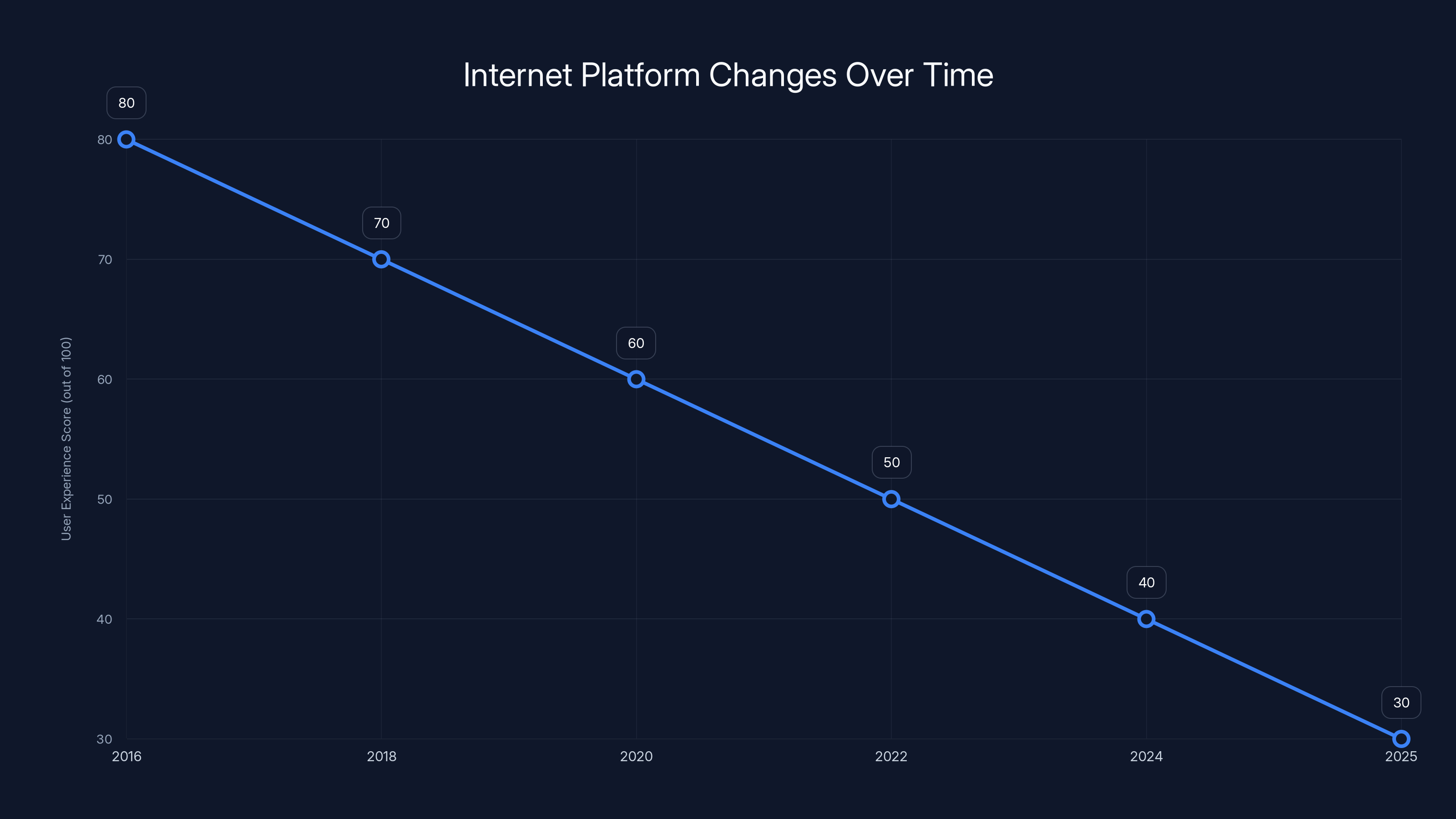

Estimated data shows a decline in user experience on internet platforms from 2016 to 2025, driven by algorithmic optimization and enshitification.

When Did the Internet Become Demoralizing?

Here's a specific marker: the word "doomscrolling" didn't exist in 2016. The phenomenon did—people were stressed, anxious, and spending too much time online—but there wasn't a word for the specific experience of scrolling through an endless feed of catastrophic news, designed by an algorithm to keep you engaged through despair.

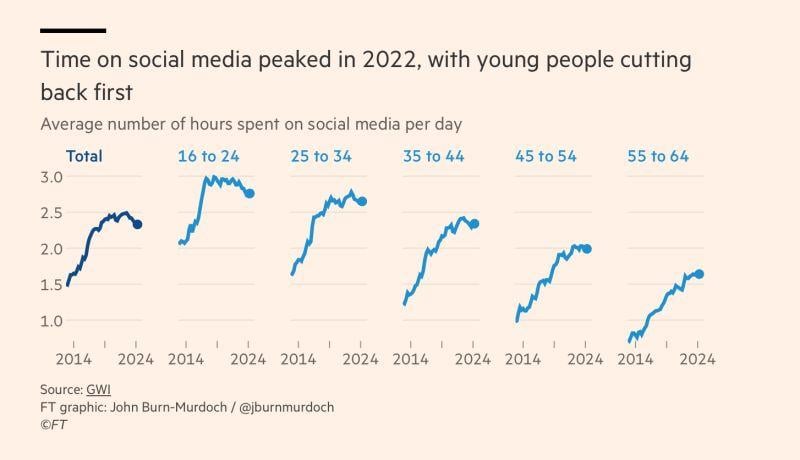

Doomscrolling requires two specific conditions: infinite scrolling (which existed in 2016 but wasn't as aggressive) and algorithmic optimization for engagement through negative content. By 2016, social media had started implementing aggressive infinite scroll. By 2018-2020, platforms had fully optimized for rage engagement. By 2025, the entire online ecosystem has calcified around this model.

The algorithm has learned that people spend the most time when they're emotionally activated. Rage, outrage, fear, and despair are powerful emotions that trigger engagement. Contentment, connection, and joy are not. So the algorithm serves rage.

Your feed is a custom-engineered emotional manipulation device. It's not personal. It's not because Facebook or TikTok or Instagram hate you. It's because they're optimizing for a metric that correlates with rage engagement. And they've gotten incredibly good at it.

In 2016, the internet was still annoying, still anxiety-inducing, still full of bad people saying bad things. But the structure of the platform wasn't explicitly designed to maximize despair. You could still encounter your feed chronologically. You could still control your experience somewhat. You couldn't quite be certain that every single piece of content you saw was selected by an algorithm specifically to trigger an emotional reaction.

The Era of Deepfakes and the Loss of Epistemic Trust

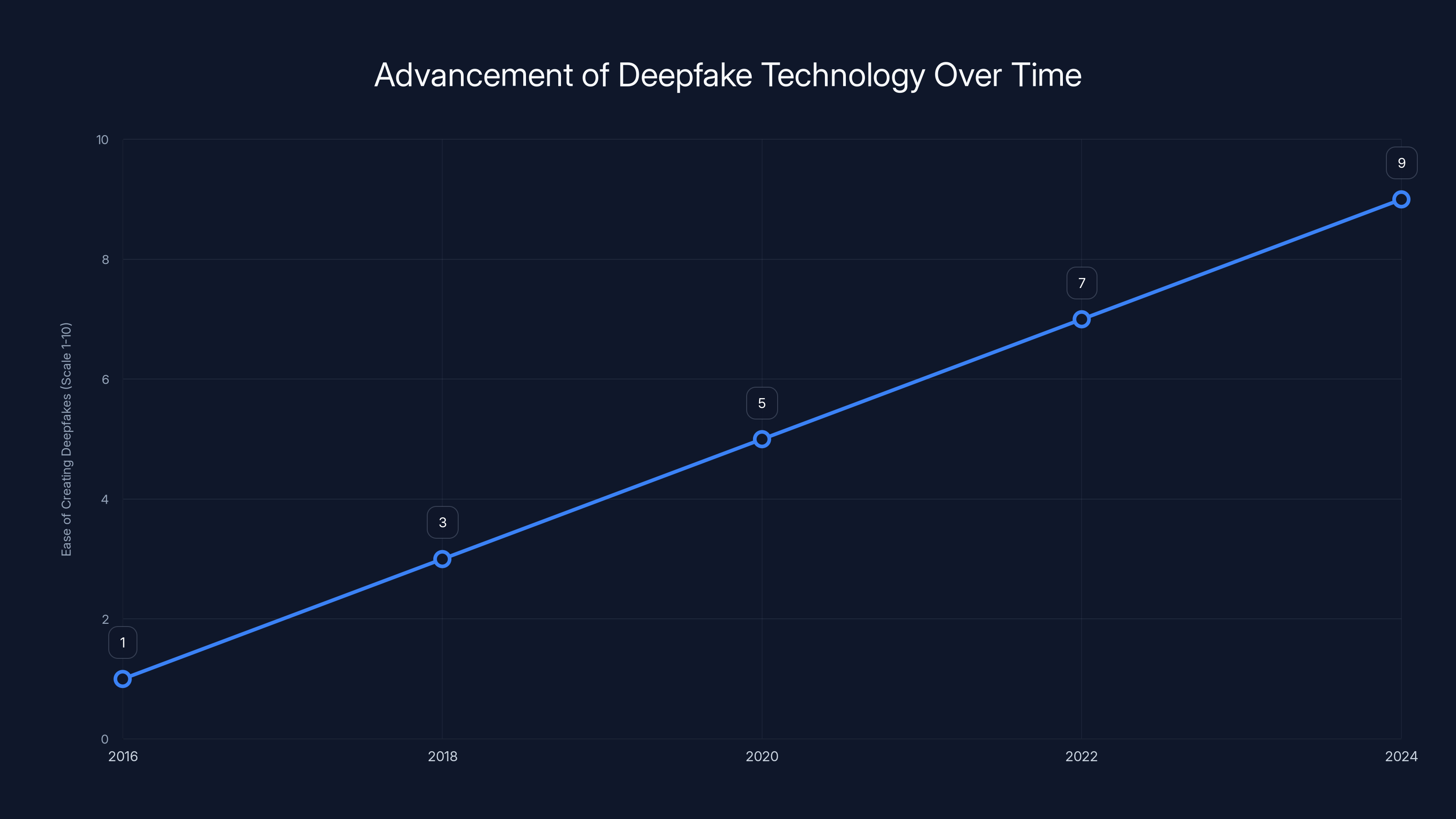

In 2016, deepfakes were almost impossible to create. You needed serious technical skills and substantial computing power. A video of a politician saying something false was still a video. You could verify its authenticity relatively easily.

Now, deepfakes are trivial to create. An AI can convincingly fake anyone's voice or video in minutes. The technology has advanced so rapidly that verification has become nearly impossible. Worse, platforms haven't figured out how to flag or manage deepfakes at scale. So we're living in a moment where any video or audio could be fake, and we have almost no reliable way to verify.

This has completely destroyed epistemic trust. You can't trust what you see. You can't fully trust what you hear. You have to cross-reference multiple sources, check publication dates, verify original sources, and even then, you might be wrong. Cognitive load has skyrocketed.

In 2016, you still felt like you could reasonably verify information. News sources still had standards. Fact-checking was possible. Misinformation existed, but it was easier to identify because it was human-made, and humans leave traces. An AI-generated piece of misinformation is indistinguishable from truth, shareable at algorithmic scale, and impossible to verify.

Teachers now have to dedicate substantial resources to teaching students how to identify AI-written homework. This wasn't a problem in 2016. You could assign essay homework and have relative confidence that the work was genuine. Now, every piece of text could be AI-generated, and detection is unreliable.

The ease of creating deepfakes has dramatically increased from 2016 to 2024, dropping the barrier from requiring expert skills to being accessible to anyone with minimal resources. Estimated data.

Social Media Went From Optional to Mandatory

In 2016, social media was still optional. You could skip Instagram and still have a social life. You could avoid TikTok and still stay culturally current. Social media was a thing you did, not the infrastructure of human connection itself.

By 2025, social media is effectively mandatory. Your job requires a LinkedIn presence. Your dating life requires Tinder or Bumble. Your business requires Instagram or TikTok. Your social circle communicates on WhatsApp or Discord. You can't opt out anymore. Not without significant social penalty.

This shift fundamentally changed the experience. When something is optional, you engage with it intentionally. You're there because you want to be there. You can leave whenever it stops being fun.

When something becomes mandatory, engagement changes. You're there because you have to be there. The experience doesn't need to be enjoyable. It just needs to be sticky. And platforms optimized for stickiness, not enjoyment.

Stickiness comes from habit, from notification anxiety, from FOMO, from the optimized algorithmic recommendation of content designed to trigger engagement. It does not come from genuine connection or authentic self-expression.

People miss 2016 because they had a choice about being online. They could log off without missing critical social infrastructure. Now, staying off social media means missing your job updates, your friends' announcements, and the basic social currency required to participate in society.

The Creator Economy Turned Everyone Into Content Machines

In 2016, if you wanted to make money on the internet, you had a few paths. YouTuber, blogger, online shop owner. These were actually difficult to achieve. They required real skill, real audience-building, and real content quality.

Now, the creator economy promises that anyone can monetize their attention. Sponsored posts, affiliate links, Patreon subscriptions, TikTok bonuses. The barriers dropped. But the trap is that once you're monetized, your content is no longer something you do. It's your business. And businesses optimize for survival, which means algorithmic optimization, audience growth, engagement metrics.

Your authentic self becomes a product. Your real thoughts become content. Your genuine experiences become engagement bait.

This flipped the incentive structure. In 2016, people shared things online because they wanted to share them. They posted photos because they were excited about something, not because they were optimizing for engagement. They wrote about their lives because they wanted to document them, not because they were building a personal brand.

Now, every action is evaluated through a monetization lens. Did this post perform well? Can I expand on this niche? How do I build an audience around this interest? The moment monetization enters, authenticity degrades. You're no longer sharing for connection. You're sharing for optimization.

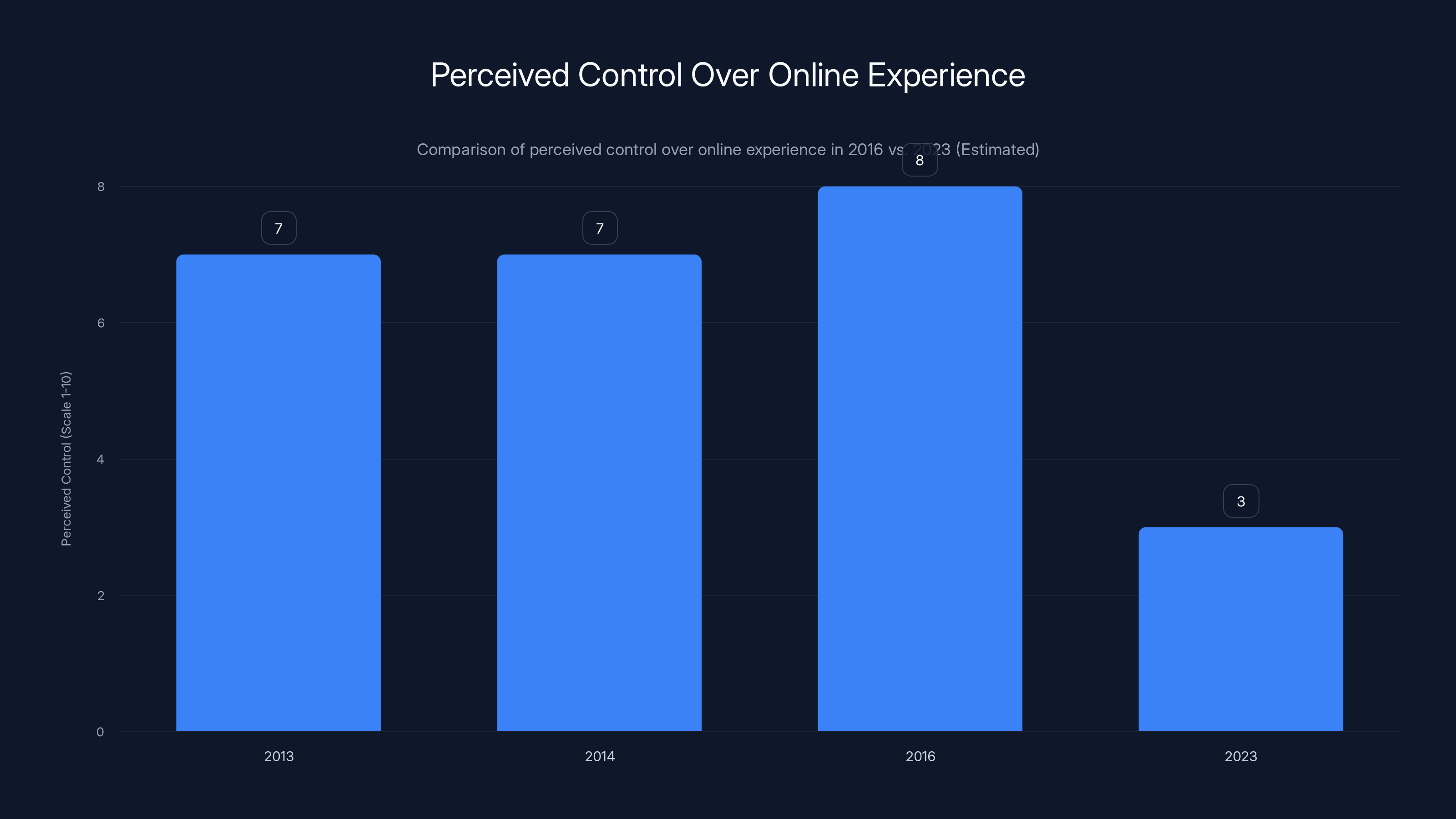

Estimated data shows a significant decline in perceived control over online experiences from 2016 to 2023, reflecting increased algorithmic influence.

Why Analog Nostalgia Isn't Random

The resurgence of interest in film photography, point-and-shoot cameras, vinyl records, in-person dating, and handwritten notes isn't random. It's a reaction to the same underlying problem: the internet got optimized, and something about authentic human experience was lost in the process.

A film camera forces you to be intentional. You have a limited number of exposures. You have to wait to develop them. You can't infinitely iterate. This friction, which would have been seen as a limitation in 2016, is now a feature. It forces quality. It forces intentionality.

Vinyl records require you to put the whole album on. You can't skip to the next song without physically getting up. This friction makes listening an intentional act, not a background distraction. You actually hear the album instead of using it as functional background noise.

In-person dating requires coordination, vulnerability, and risk. You can't optimize your way into a perfect match. You have to show up, be genuine, and see what happens. No algorithm will tell you if you're compatible. You have to find out together.

These analog technologies are being adopted not because they're better in any objective sense, but because they reintroduce human friction into experiences that have become too optimized. The friction, counterintuitively, makes them more valuable.

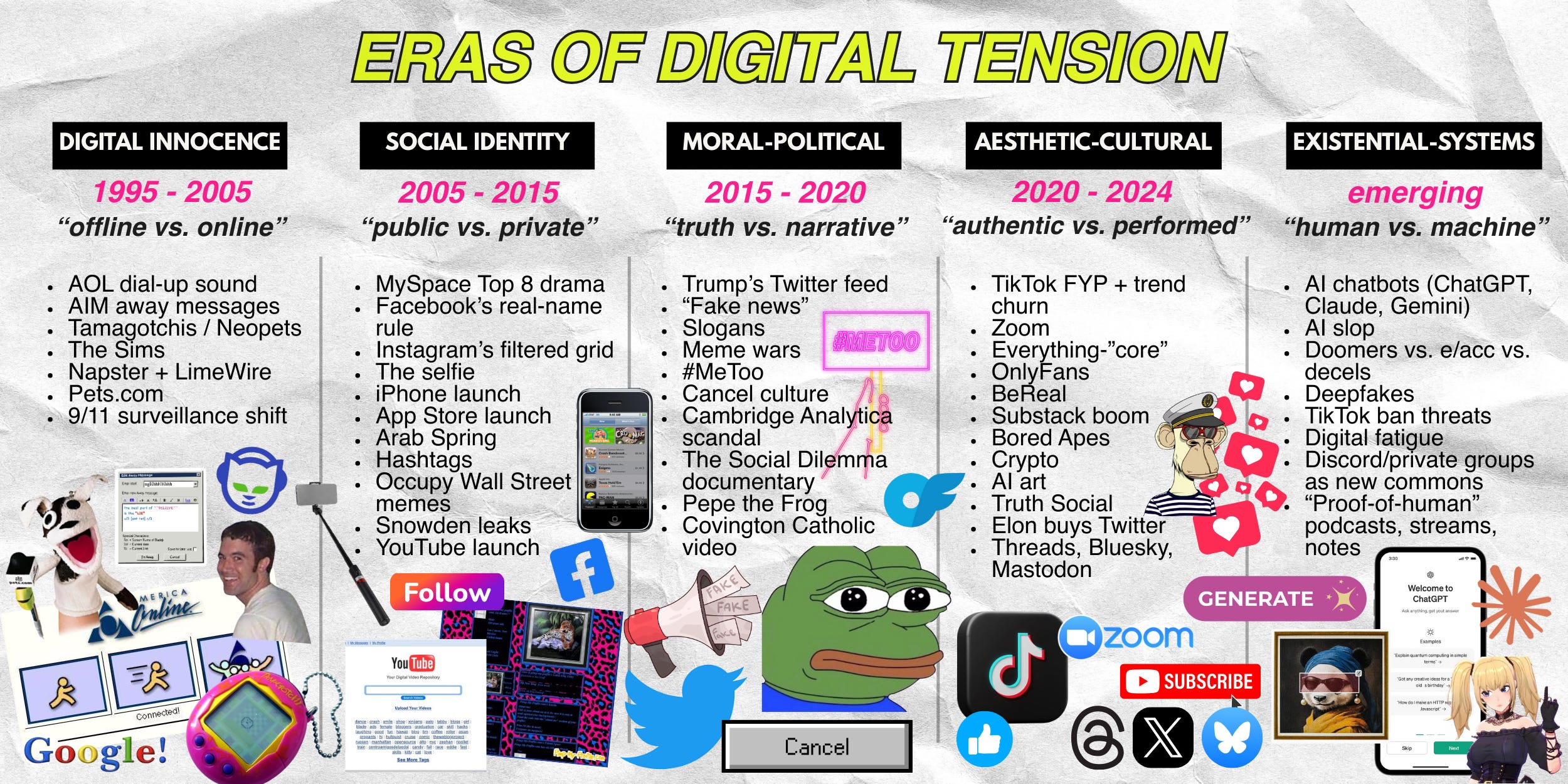

The Corruption of Internet Culture

Amanda Brennan brings up Pepe the Frog as a historical marker. In 2016, Pepe was an amiable stoner cartoon character from an indie webcomic. By 2016, it was being weaponized as a hate symbol. By 2020, we had political movements organized partially around memes. By 2025, the line between internet culture and political reality had completely dissolved.

This didn't happen because the internet is inherently political. It happened because platforms optimized for engagement, and political content generates engagement. Divisive content generates engagement. Outrage generates engagement. So the algorithm, in pursuing engagement metrics, essentially created a bridge between internet culture and political reality.

Memes that started as genuine humor got hijacked. Online spaces that were once playgrounds became ideological battlefields. The algorithm learned what content gained engagement and fed more of it.

Gamergate in 2016 was an early warning sign that internet culture had become a vector for real-world radicalization. Certain online spaces had become explicitly hostile to women. But at the time, it felt novel to point out that internet culture was influencing political reality.

By 2025, we know that radicalization pipelines start online. We know that algorithmic recommendation systems can push people from mainstream content into extremist content. We know that this is a real, measurable phenomenon with real-world consequences.

The internet in 2016 was still somewhere you could be weird and anonymous and safe from real-world consequences. By 2025, the internet is fully integrated with your real identity. Your online presence is indexed, analyzed, tracked, and packaged. It feeds your credit score, your job prospects, your dating potential, your healthcare, your legal standing.

There is no separation anymore. There is no space to be weird and wrong without consequence.

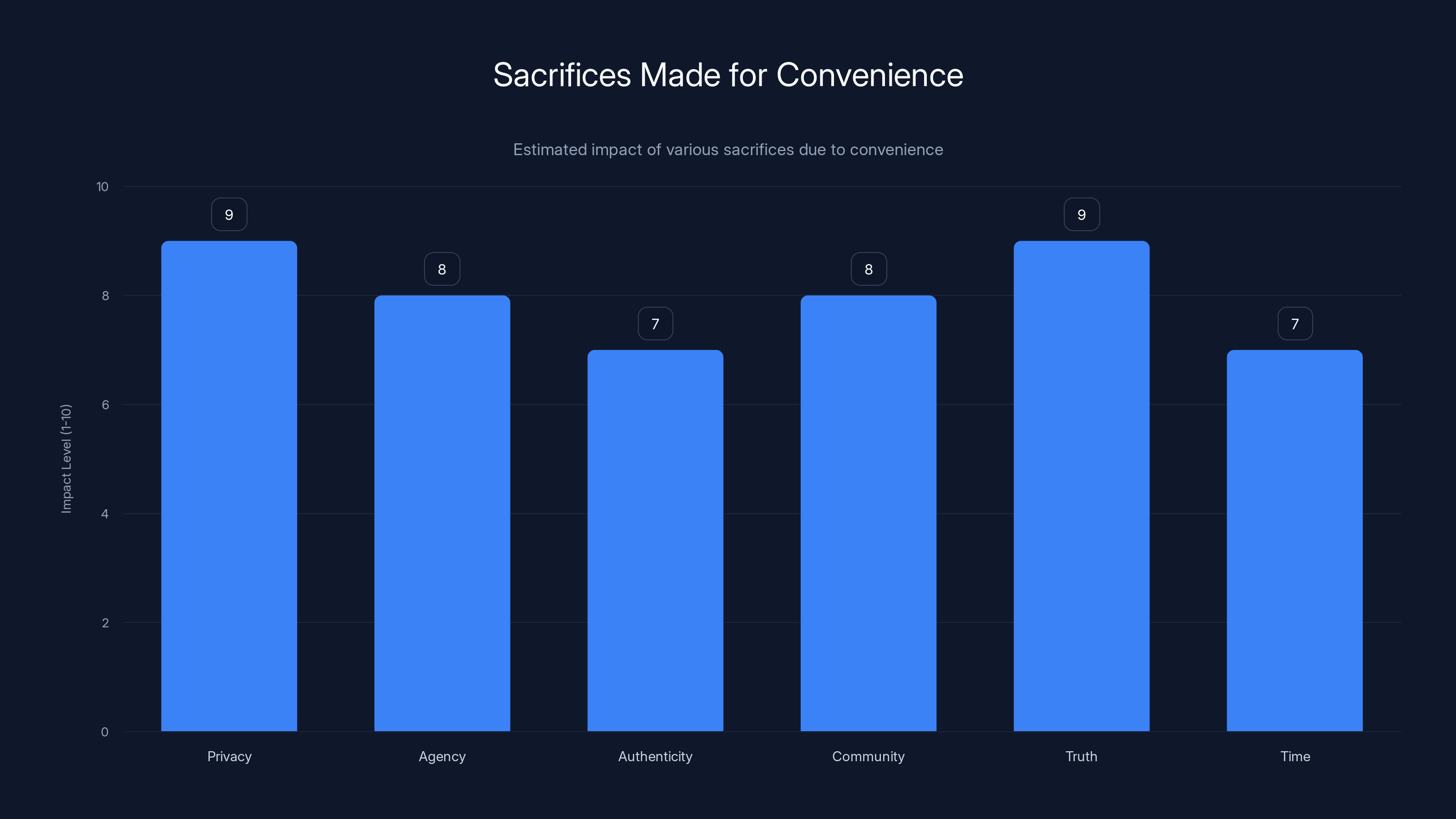

Estimated data shows high impact levels for sacrifices made in privacy, truth, and community for convenience.

The Specific Nostalgia of Pre-Algorithmic Randomness

Here's something specific people miss: serendipity. In 2016, you could browse the internet and stumble onto something genuinely unexpected. You'd click a link, fall down a rabbit hole, and discover something you never would have searched for intentionally. This wasn't algorithmic. It was just human chaos.

You could find weird forums, strange communities, unexpected information. The friction of discovery made these moments valuable. You had to search for weird things. But when you found them, they felt real.

Now, the algorithm has optimized serendipity. Your recommendations are designed to feel surprising while actually being perfectly optimized for your predicted engagement. They feel random, but they're not. They're personalized randomness, which is paradoxically more constraining than actual randomness.

You're trapped in a filter bubble that's designed to feel like exploration.

In 2016, if you were interested in niche topics, you had to actually search for them. You had to join obscure forums. You had to follow strange people on Twitter. This meant that your interest ecosystem was genuinely diverse. You might stumble onto perspectives that challenge you. You might encounter people fundamentally unlike you.

Now, the algorithm learns your preferences and optimizes toward them. If you like left-wing political content, you get more left-wing content. If you like conspiracy theories, you get more conspiracy theories. The algorithm learns to predict your preferences and then reinforces them infinitely.

This creates genuine filter bubbles. Not as a conspiracy, but as a direct result of optimization. You're served content the algorithm predicts you'll engage with. You engage with it. The algorithm learns and optimizes further. You become more polarized.

In 2016, you had to actively seek out extreme viewpoints. Now, they're delivered to you. And the algorithm optimizes for engagement regardless of whether that engagement is healthy.

What 2016 Represents Psychologically

The nostalgia for 2016 isn't really about 2016. For anyone under 30, 2016 is barely distinguishable from 2013 or 2014. They all blur together as "the last time the internet felt different."

What 2016 actually represents is a threshold. It's the last moment before algorithmic optimization became total. Before AI-generated content became omnipresent. Before deepfakes became indistinguishable from reality. Before social media became a mandatory infrastructure. Before the internet became a tool for behavioral manipulation at scale.

2016 is psychologically positioned as "the last good year" because it was the last moment when the internet felt like something you did, not something that was done to you.

For people nostalgic about 2016, it's not really about what was happening in 2016. It's about their sense of agency. In 2016, you still felt like you had control over your online experience. You could browse Twitter chronologically. You could see what you followed on Instagram. You could search Google and get relevant results. You had some illusion of control.

Now, everything is algorithmic. Everything is optimized. Every interaction is tracked and analyzed. You're not navigating the internet anymore. The internet is navigating you. Your feed is personalized to maximize engagement. Your recommendations are optimized to predict what you'll click. Your experience is entirely designed around extracting your attention.

The psychological weight of living in a fully algorithmic environment is substantial. You're constantly being manipulated, even if it's for a neutral goal like engagement metrics. Your autonomy is eroded. Your reality is personalized. You can't know what other people are seeing. You can't trust what you see. You can't verify information easily.

This is exhausting. So people dream about 2016, when these problems didn't exist.

The Enshitification Thesis and How We Got Here

Cory Doctorow described enshitification as a three-stage process. First, platforms serve their users well to gain adoption. Second, they optimize for business success by degrading user experience and extracting value. Third, they extract value from their remaining users until they become unusable.

Facebook followed this path almost exactly. Facebook in 2008-2012 was genuinely useful. It connected you with people you knew. It was chronologically organized. It was valuable.

Facebook in 2012-2018 started optimizing for advertising and engagement. The chronological feed was replaced with an algorithm. Content from friends became less visible. Ads became more prevalent. But the core experience was still recognizable.

Facebook in 2018-2025 became increasingly unusable. The feed is so heavily algorithmic that you can't actually see what your friends are posting. Ads and content recommendations overwhelm genuine connection. The app is bloated. It pushes you toward engagement, not toward genuine connection.

Google followed a similar path. Google in the early 2000s provided relevant search results. Google in the 2010s started ranking paid results higher and pushing Google products (YouTube, Maps, Shopping) higher. Google in 2020-2025 has become so optimized toward revenue that search results are often useless. AI summaries replace links. Paid results dominate. Your actual question is subordinated to what Google wants to show you.

Every platform followed this pattern because the incentive structure rewards it. If you're optimizing for shareholder value and engagement metrics, enshitification is the inevitable result. It's not a conspiracy. It's math.

In 2016, the enshitification process was in stage one or early stage two. The platforms were still somewhat optimized for users. The experience was degrading, but slowly. The decline accelerated from 2016-2025.

What We've Sacrificed for Convenience

Part of the reason people miss 2016 is that we've collectively sacrificed a tremendous amount for the convenience of platforms. We've sacrificed privacy. Our data is harvested, analyzed, sold. We have almost no control over what information is collected about us.

We've sacrificed agency. We don't choose what we see. An algorithm does. We don't choose our feed order. An algorithm does. We don't even choose what ads we're targeted with. An algorithm does.

We've sacrificed authenticity. Every interaction is optimized. Every photo is curated. Every post is analyzed for engagement. We're constantly performing for an algorithm's prediction of what will resonate.

We've sacrificed community. Real communities require shared norms, enforcement, and boundaries. Algorithmic platforms are designed to scale infinitely, which means there are no real boundaries. No real enforcement. No real community, just networked individuals being served the same recommended content.

We've sacrificed truth. Information quality has degraded. AI-generated slop has contaminated every search. Deepfakes have made verification nearly impossible. Misinformation spreads faster than correction. We can't trust what we see.

We've sacrificed time. Infinite scroll, push notifications, algorithm-optimized content designed to hook you. We're spending more time online and feeling worse about it.

We made these sacrifices willingly, for the promise of convenience, connection, and free services. And for a while, the trade felt worth it. Connect with everyone instantly. Get information immediately. Discover new content. Stay updated on everything.

But by 2016, people were starting to realize the cost. And by 2025, the cost has become visible. The convenience came at the expense of everything that made the internet valuable to begin with.

The Irony of Nostalgia for the Year Everyone Hated

The deepest irony is that we're nostalgic for a year we hated. In 2016, people were constantly saying how bad things were. Memes about how evil 2016 was were everywhere. The year felt catastrophic.

But the catastrophe was external. It was the news, the political situation, the world events. The internet was still a relatively safe space. You could log off. You could find community. You could explore. The internet itself wasn't the source of despair.

Now, the despair is embedded in the structure of the internet itself. The algorithm serves despair. The infinite scroll traps you. The notifications harass you. The engagement metrics reward conflict. The algorithm learns your anxieties and feeds them back to you.

External catastrophes are survivable because you can at least choose to disengage. But when the medium itself is designed to maximize despair? That's inescapable. You can't log off. You need these platforms. And when you use them, you're fed a personalized diet of content designed to keep you engaged through negative emotion.

So we miss 2016, even though 2016 sucked. Because 2016 sucked in a way we could understand and cope with. It sucked because of external events, not because the infrastructure of communication was fundamentally hostile to human wellbeing.

Where We Go From Here

The nostalgia for 2016 won't solve anything. We can't go backward. The technology exists. The business incentives exist. The platforms exist.

But understanding what we're nostalgic for is important. We're not nostalgic for a specific year. We're nostalgic for an internet that felt like a tool, not a trap. We're nostalgic for agency. We're nostalgic for community. We're nostalgic for the possibility of surprise. We're nostalgic for the idea that the internet was something we used, not something that used us.

Recovering any of that will require either technological change (new platforms designed differently) or regulation (platforms forced to design differently) or both. It will require abandoning the engagement metric as the primary optimization target. It will require making platforms less convenient and more intentional.

It will require friction.

Most platforms will resist this because friction reduces engagement time and advertising revenue. But smaller platforms, new entrants, or heavily regulated platforms might experiment with different models. They might optimize for user wellbeing instead of engagement time. They might restore chronological feeds. They might limit algorithmic recommendation. They might prioritize privacy.

Some of these experiments will fail. Some will succeed but remain niche. But the fact that we're collectively nostalgic for a time when the internet worked differently is significant. It means we recognize the problem. We just need to figure out how to fix it.

The 2016 nostalgia trend isn't a solution. It's a symptom. It's our collective recognition that something fundamental about the internet has broken. We miss 2016 not because 2016 was good, but because the internet was still navigable then. It hadn't yet optimized away everything that made it valuable.

FAQ

What do people mean when they say they're nostalgic for 2016?

People aren't nostalgic for 2016 as a year (it was politically chaotic and stressful). They're nostalgic for how the internet functioned in 2016, before algorithmic optimization became total, before AI-generated content became omnipresent, and before social media became mandatory infrastructure. The year represents a threshold before the internet became systematically designed to maximize engagement through despair.

Why has the internet become worse since 2016?

Since 2016, platforms have increasingly optimized for engagement time and advertising revenue, which mathematically leads to algorithmic amplification of conflict, outrage, and divisive content. Artificial intelligence has enabled the generation of infinite low-quality content. Deepfakes have made verification nearly impossible. Social media has shifted from optional to mandatory. Every interaction is now tracked, analyzed, and used to further optimize engagement. These changes happened not because of conspiracy, but because of incentive structures that reward engagement metrics above user wellbeing.

What is enshitification and how does it relate to internet platforms?

Enshitification is the process by which online platforms initially serve users well to gain adoption, then gradually degrade the user experience to extract value from users and advertisers, until the platform becomes unusable. Facebook, Google, Twitter, and Instagram have all followed this pattern, with stage three acceleration occurring between 2020-2025. The process isn't intentional conspiracy but rather the inevitable result of optimizing for shareholder value and engagement metrics over user experience.

Why is algorithmic content recommendation worse than chronological feeds?

Chronological feeds show you what people you follow actually post, giving you agency in what you see. Algorithmic feeds show you what an algorithm predicts will maximize your engagement time, which mathematically correlates with rage, outrage, conflict, and divisive content. Algorithms learn your preferences and reinforce them infinitely, creating filter bubbles. Chronological feeds expose you to diverse perspectives, including people unlike you. Algorithms optimize toward what you already like, polarizing you further.

How has AI-generated content degraded the internet?

AI can generate infinite low-quality but technically functional content at near-zero cost. Every search result now includes AI summaries that half-answer your question. Content farms generate thousands of AI-written articles optimized for search algorithms rather than human comprehension. YouTube, blogs, social media, and product reviews are flooded with AI-generated slop. This has created a signal-to-noise problem where genuine human-created content is buried under the sheer volume of algorithmic slop. The internet has become harder to navigate because finding actual useful information requires filtering through vast quantities of technically correct but emotionally inert AI-generated content.

What is doomscrolling and when did it become a problem?

Doomscrolling is the compulsive consumption of negative news through infinite-scroll platforms, designed by algorithms to keep you engaged through despair. The word didn't exist in 2016, but the phenomenon emerged around 2018-2020 as platforms fully optimized algorithmic feeds for engagement through negative content. By 2025, doomscrolling has become a widespread mental health problem. The structure of platforms—infinite scroll, algorithmic amplification of negative content, notification harassment—is designed to trigger doomscrolling. It's not a character flaw. It's a design feature.

Why has in-person connection and analog technology become appealing again?

Analog technologies like film photography, vinyl records, and in-person dating reintroduce friction into experiences. This friction, counterintuitively, makes these experiences more valuable because it forces intentionality and limits quantification. A film camera forces you to be thoughtful about each shot. Vinyl forces you to listen to full albums. In-person dating requires vulnerability and risk. These constraints make experiences feel more real and less optimizable. This appeals to people exhausted by a digital environment designed entirely around optimization and quantification.

Is it possible to recover what was good about 2016 internet?

Recovering agency, community, and authenticity online will require technological change, regulation, or both. It will require abandoning engagement metrics as the primary optimization target. It will require platforms willing to accept lower engagement time to improve user wellbeing. Some new platforms are experimenting with different models: chronological feeds, limited algorithms, privacy protection, design for genuine community. But recovering the experience of 2016 internet requires either widespread platform migration or regulation forcing existing platforms to change how they operate. This is possible but politically difficult because it requires platforms to sacrifice revenue for user wellbeing.

The Path Forward: Building Better Alternatives

The nostalgia for 2016 might seem like mere sentiment, but it's actually pointing toward real problems that demand real solutions. The current internet isn't inevitable. It's the result of specific design choices, specific business models, and specific incentive structures. Other choices are possible.

Some alternative platforms are emerging. Threads, Bluesky, and Mastodon are exploring different approaches to social networking. Some are experimenting with chronological feeds. Some are prioritizing smaller communities. Some are rejecting advertising models. None of them have reached critical mass yet, which is partly a network effect problem (you need your friends on the platform to make it valuable) and partly a problem of friction (they're less convenient than Facebook or Instagram).

But friction might be the point. The platforms we're nostalgic for had friction built in. They required effort. They didn't infinitely optimize your experience. They left room for serendipity, for surprise, for genuine human interaction.

Building better alternatives will require accepting that convenience is a feature we've optimized too hard on. It will require designing platforms that optimize for genuine connection instead of engagement time. It will require limiting algorithmic recommendation. It will require respecting privacy. It will require transparency about how data is used.

These are all possible. They're just not profitable in the same way. They require different business models. Subscription instead of advertising. User agency instead of algorithmic control. Community moderation instead of AI moderation.

The fact that we're nostalgic for 2016 is actually hopeful. It means we recognize what we've lost. We know what better looks like. We're not trapped in the false belief that the current internet is the only possible internet. We're just waiting for someone to build the alternative.

Until then, the best we can do is resist the pull of engagement metrics in our own lives. Build friction back in. Use platforms chronologically instead of algorithmically. Seek out smaller communities. Create because you want to create, not because you're optimizing engagement. Find people offline. Read books. Have conversations. Rediscover the joy of being bored and finding something unexpected because you actually searched for it, not because an algorithm served it to you.

The internet of 2016 wasn't perfect. But it was more human. And maybe that's worth building toward again.

Key Takeaways

- We're nostalgic for 2016 not because that year was good, but because the internet was still navigable—algorithmic optimization hadn't yet become total.

- Enshitification is the inevitable result of platforms optimizing for engagement metrics over user experience, following a three-stage degradation pattern.

- AI-generated content has flooded the internet with technically correct but emotionally inert slop, making information discovery exponentially harder.

- Algorithmic feeds have replaced human agency with personalized manipulation designed to maximize engagement through conflict and despair.

- Reclaiming the internet will require new platforms with different incentive structures, acceptance of useful friction, and regulation forcing transparency.

Related Articles

- Instagram's AI Problem Isn't AI at All—It's the Algorithm [2025]

- People-First Communities in the Age of AI [2025]

- YouTube's SRV3 Captions Disabled: What Creators Need to Know [2025]

- Complete Guide to Content Repurposing: 25 Proven Strategies [2025]

- UK Social Media Ban for Under-16s: What You Need to Know [2025]

- Proton VPN Kills Legacy OpenVPN: What You Need to Know [2025]

![Why We're Nostalgic for 2016: The Internet Before AI Slop [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/why-we-re-nostalgic-for-2016-the-internet-before-ai-slop-202/image-1-1769013618242.jpg)