The Moment Everything Changed: Will Smith, Spaghetti, and AI Gone Wild

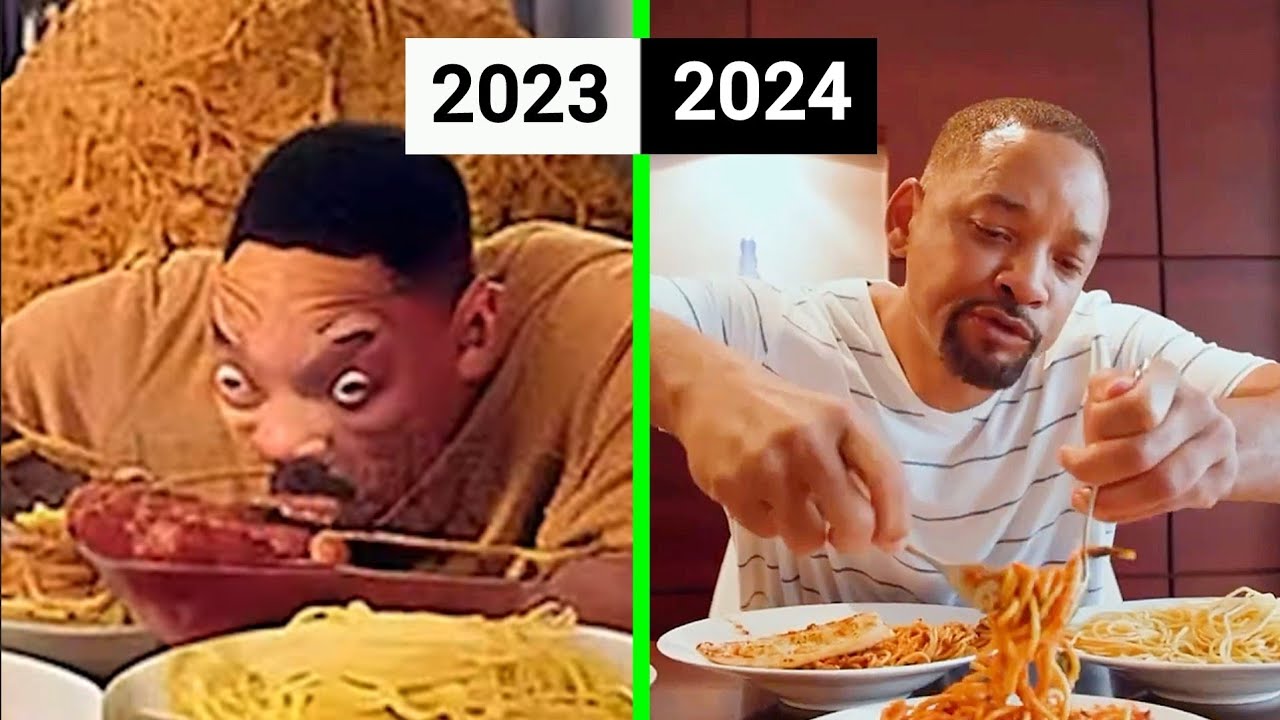

Last May, something ridiculous happened on the internet. Someone fed an AI a simple prompt: "Will Smith eating spaghetti." What came back was pure, unfiltered chaos. The video showed the Oscar-winning actor jamming oversized pasta into his mouth with the focus of a competitive eater, his lips glossy with oil, his expression blissfully unfocused. It wasn't technically wrong—it was just completely absurd.

The thing is, it looked fake. Deliberately, hilariously fake. The proportions were slightly off. The movements had that uncanny smoothness that screamed "generated." The internet ate it up. Memes exploded. Think pieces multiplied. Everybody had an opinion about what this meant for Hollywood, deepfakes, and the future of visual media.

But here's what's wild: if you asked the same AI to generate that same video right now, you'd get something that looks disturbingly real. Not the cartoony, obviously-artificial version from early 2023. We're talking photorealistic facial movements, proper physics, lighting that matches human behavior. The progression hasn't been gradual. It's been exponential.

That spaghetti video became an accidental benchmark for AI video technology. It wasn't designed as one. Nobody sat down and said, "Let's make Will Smith eating pasta the metric by which we measure synthetic video progress." But that's exactly what happened. In the span of roughly 18 months, we went from a meme to something that could genuinely fool people if they weren't paying attention.

This matters because it reveals something most people don't understand: AI progress isn't linear. It's not like Moore's Law, where things get incrementally better each year. It's exponential. It's faster than predictions. And it's getting harder to detect.

The Will Smith spaghetti video is the perfect symbol for this transition. It marks the exact moment when AI-generated content stopped being a novelty and started becoming something else entirely. Something we need to take seriously.

Why That Video Was So Hilariously Bad (And Why That Matters)

Let's talk about what made the original video so memorable. It wasn't just bad—it was entertainingly bad. The kind of bad that makes you laugh out loud because your brain immediately recognizes something's off, but you can't quite articulate what.

The spaghetti itself was physics-defiant. Real pasta has weight, texture, the way it clings and breaks. The AI's version looked like it was made of rubber. The proportions were wrong. Will Smith's mouth seemed to unhinge in ways that suggested his jaw was somehow detachable. His eyes didn't track his fork in a natural way. The whole thing had a dreamlike quality—not realistic enough to fool anyone, but detailed enough that you could understand what the AI was trying to do.

This is actually important. Early AI video models had a critical limitation: they couldn't understand physical constraints. They learned patterns from video data, but they didn't have built-in knowledge of how gravity works, how skin stretches, how light reflects off surfaces. They were generating frame-by-frame based on statistical probability, not physics simulation.

So when you asked it to show someone eating spaghetti, it could generate something that looked vaguely like eating. It could make the mouth move. It could approximate facial expressions. But it couldn't handle complex interactions between objects and physics. The result was something that looked like someone was eating, but with a subtle wrongness that made your brain immediately reject it as real.

Here's the fascinating part: that wrongness was actually useful. It was a tell. A visual signature that said, "This is AI-generated." You could show that video to anyone—your grandmother, a film director, a skeptic—and they'd immediately know it wasn't real. Not because they could point to specific problems, but because their pattern-recognition systems would flag it as uncanny.

That tell has largely disappeared now.

The original video's problems were distributed across multiple domains. Facial geometry. Hand-to-object interaction. Lighting consistency. Background coherence. Object physics. Each one of these is a separate problem in machine learning terms. The 2023 models were still developing solutions for all of them simultaneously. They were decent at some, terrible at others.

Now? The frontier has shifted. Modern models are getting scary good at the individual components. The weak link has become something different: consistency across time and logical coherence. Your video might look photorealistic frame-by-frame, but does the person's expression make sense for what they're supposedly experiencing? Are shadows consistent with the light source? Does the scene follow the rules it established three seconds ago?

These are the new tells. The new places where AI video gives itself away. And they're significantly harder to spot for most viewers.

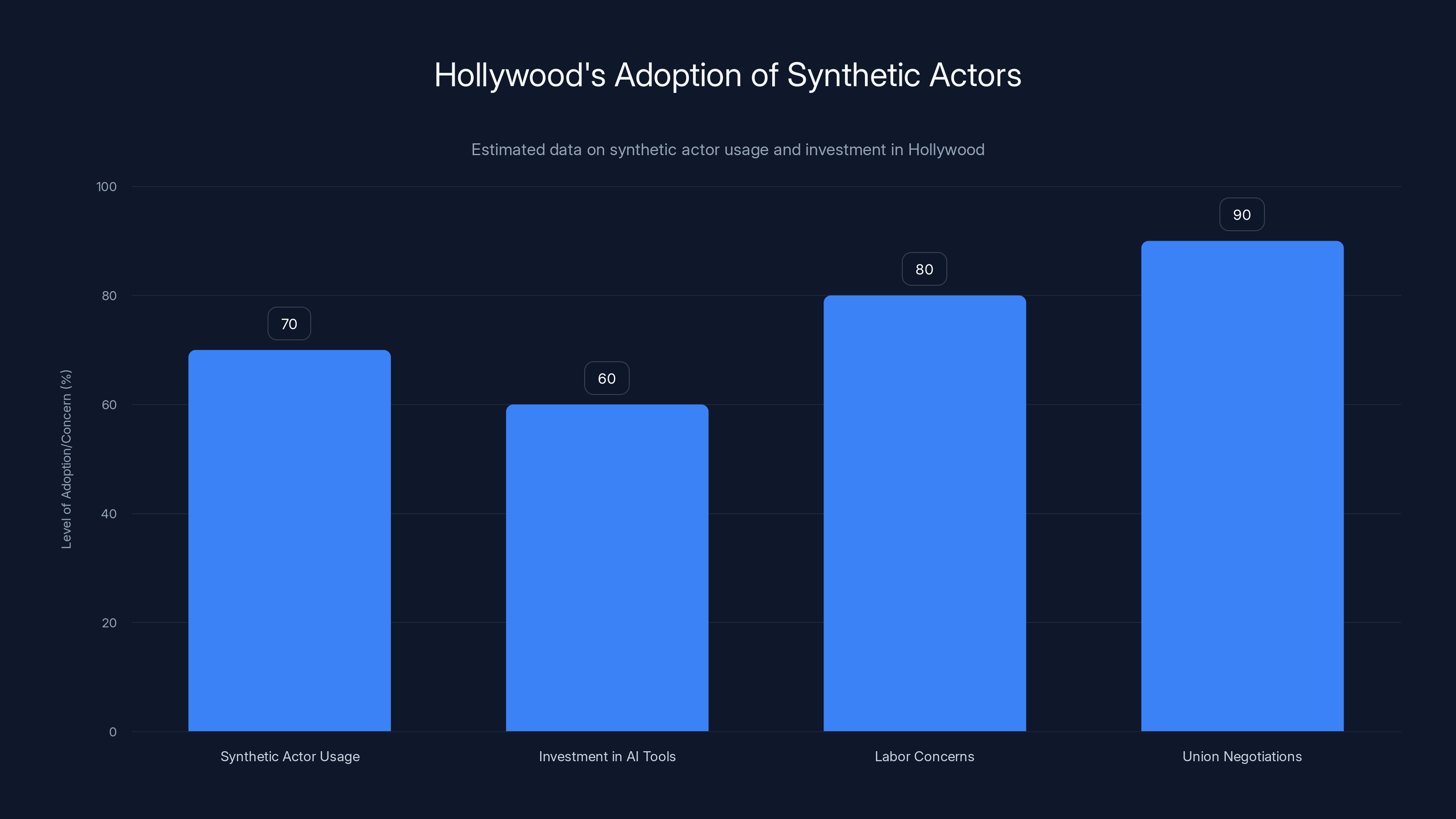

Hollywood is increasingly adopting synthetic actors, with significant investment in AI tools and high levels of labor concerns and union negotiations. (Estimated data)

The Technology That Made the Spaghetti Possible

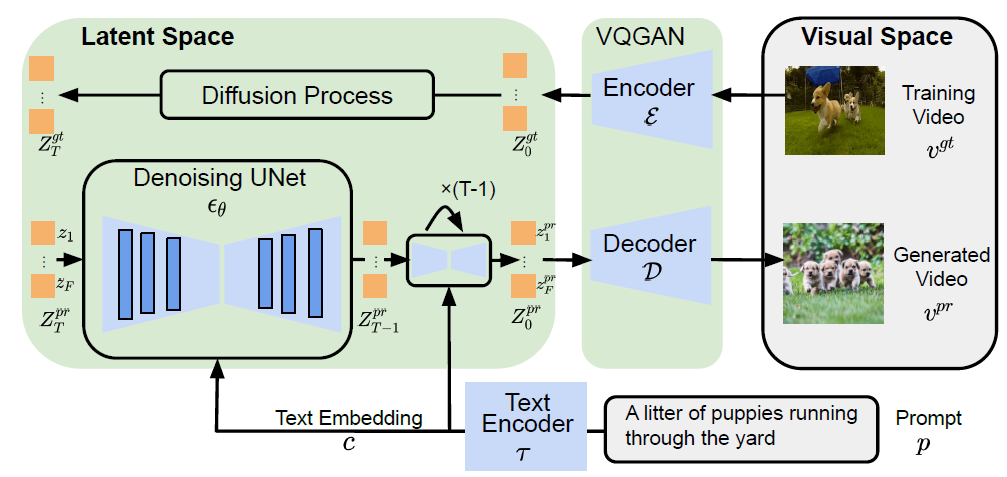

You can't understand how fast we've moved without understanding what actually changed under the hood. The 2023 version of AI video generation wasn't magic. It was math, but math applied in a specific way that nobody had quite cracked before.

The core breakthrough came from something called diffusion models. Instead of training an AI to generate an entire image from scratch (which is computationally nightmarish), diffusion models work backward. They start with pure noise—random pixels—and then iteratively refine it based on a text prompt. Over dozens or hundreds of steps, noise becomes signal. Chaos becomes a coherent image.

For video, this created an obvious problem: if you generate each frame independently, they don't connect to each other. Frame 1 might show someone with their mouth open. Frame 2, for reasons the model didn't track, might show them with their mouth closed. The result is a flickering, inconsistent mess.

So the innovation was to add temporal coherence constraints. The model doesn't just generate frame N in isolation. It generates frame N while being "aware" of frames N-1 and N+1. It understands that this should be a continuous motion, not a series of unrelated images.

But here's where 2023 hit a wall: this was still computationally expensive as hell. It required massive amounts of GPU power. It was slow. And even with constraints, the model would sometimes just give up and violate continuity anyway.

The breakthrough of late 2023 and 2024 came from efficiency improvements. Better architectures. Smarter sampling techniques. Attention mechanisms that could track objects across frames without needing to process the entire video at once. Suddenly, video generation went from taking minutes to taking seconds. From requiring specialized hardware to running on consumer GPUs.

The models also got smarter about training data. Early versions trained on whatever video was available, which meant they learned a lot of bad habits. They'd seen plenty of low-quality user footage, shaky camera movements, compression artifacts. When you asked them to generate video, they'd replicate these patterns.

Newer models trained on higher-quality data sources. More professional footage. More carefully curated datasets. This meant they had better priors—better statistical assumptions about how the world should look. When they generated Will Smith eating spaghetti in 2024, they started from a better baseline assumption about what eating should look like.

There's also the matter of scale. Models that are bigger—more parameters, more layers, more capacity—tend to be better. They can learn more subtle patterns. A 1 billion-parameter video model is going to produce better results than a 100 million-parameter model, generally speaking. The industry has been scaling up. More compute means better results.

One more piece: the integration of other AI capabilities. Modern video generation models don't exist in isolation. They're connected to separate AI systems for face rendering, hand tracking, object detection, and physics simulation. When these components work together, the results are much more convincing. Instead of one monolithic model trying to handle everything, you have specialized systems that are each really good at their specific job.

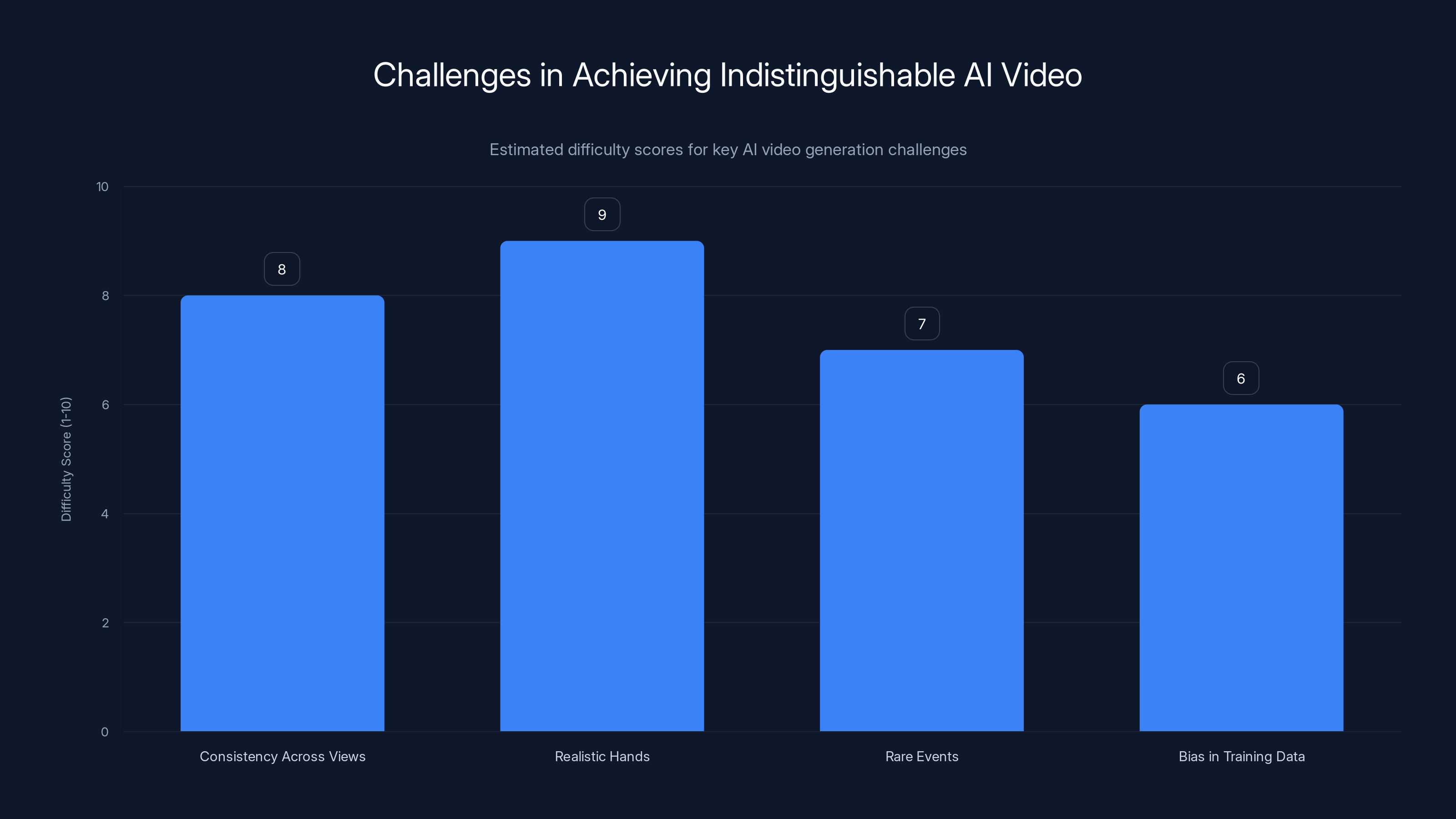

Realistic hands and consistency across views are the most challenging aspects in AI video generation, with difficulty scores of 9 and 8 respectively. Estimated data.

The Deepfake Evolution: From Obvious Fakes to Undetectable

Let's be direct: the implications are getting serious. We're past the point where you can rely on AI-generated video being obviously fake. The technology has crossed a threshold.

In 2023, the tell-tales were obvious. You could spot an AI-generated video because of the weird proportions, the uncanny valley effects, the physics violations. Those tells are increasingly unreliable. If someone generates a video of you saying something you never said, using a modern model, your own family might believe it's real if they're not paying attention.

This creates a genuinely new problem for society. We're not just talking about celebrity meme videos anymore. We're talking about fraud, misinformation, political manipulation, and weaponized deepfakes. The technology that made Will Smith's spaghetti-eating amusing is the same technology that could fabricate evidence of a crime, create non-consensual intimate imagery, or convincingly show a political figure making inflammatory statements.

The detection arms race has already started. Researchers are building deepfake detectors. The logic is straightforward: if AI-generated video has specific artifacts or patterns, maybe you can train another AI to recognize those patterns. But this is a game that favors the offense. Every time someone publishes a detector, generators improve to avoid it. It's like an immune system facing an evolving virus.

What's particularly tricky is that the improvements in video generation are making detection harder, not easier. More realistic video doesn't have obvious visual tells. That means detectors have to look for subtler things. Statistical anomalies. Biometric inconsistencies. Things that a human viewer would never notice.

The good news: we're still in a window where humans can usually tell the difference if they're paying attention. The bad news: that window is closing. In another year or two, even careful observation might not be enough. You might need forensic-level analysis. Frame-by-frame pixel inspection. In some cases, impossible standards of proof.

Some researchers are experimenting with proactive solutions. Digital watermarking—embedding a signature into generated video that identifies it as synthetic. The problem: it's an arms race. Adversarial actors develop watermark-removal techniques. Watermark-removal defenders develop more robust watermarks. Round and round it goes.

The really uncomfortable truth is that detection might be a losing battle. The better approach might be societal: cryptographic verification of authentic video. Blockchain-based proof-of-origin. Legal frameworks around video evidence. But these require coordination. They require buy-in from platforms, from legal systems, from society. We're nowhere close to having those conversations, let alone implementing solutions.

The Will Smith spaghetti video was funny because it was obviously fake. Future deepfakes might not have that luxury. They might look real enough to fool forensic analysis. And that's when things get genuinely dangerous.

How Hollywood Is Already Responding

You'd think the film industry would be panicking right now. In some ways, they are. In other ways, they're quietly integrating the technology into their workflow.

There's been serious investment in synthetic actors. Film studios are experimenting with generating digital versions of celebrities—sometimes with their permission, sometimes without. The use case is straightforward: if you need to show a young version of a character, instead of hiring a younger actor or aging up a younger actor's face, you can generate a synthetic version. It's faster. It's cheaper. It's more consistent.

There's also the question of replacement actors. What if an actor gets injured mid-production? What if they pass away during filming? Instead of shutting down production, you could generate synthetic footage of them finishing the film. It sounds morbid, but it's economically sensible. A major film production might cost $200 million. The cost to synthetically generate an actor's remaining scenes? Probably a few million. The math is obvious.

Hollywood's strategy seems to be: normalize the technology, build proprietary versions, control the narrative. Various studios have announced their own in-house AI video generation tools. It's a classic tech industry pattern: if something's going to change your industry, you want to be the one controlling it.

But there's also legitimate concern about labor. If you can generate synthetic versions of actors, what happens to acting as a profession? If you can synthesize dialogue, what happens to voice acting? These aren't hypothetical questions. Actors' unions have been negotiating with studios specifically about synthetic replacement. The negotiations are contentious because the stakes are genuine.

The Screen Actors Guild has been pushing back. They want strict limitations on when synthetic actors can be used. They want compensation when a digital version of their likeness is created. They want protections for stunt performers, whose jobs are already being displaced by CGI. These are legitimate concerns from people whose careers depend on physical presence and unique talent.

The outcome of these negotiations will shape how the technology develops. If studios are forced to pay for synthetic actors, the economic advantage shrinks. If they can use digital versions freely, the incentive to do so becomes overwhelming. We're in the middle of establishing the rules that'll govern this space.

What's interesting is that the studios that are being most aggressive about adopting this technology are also the ones most vulnerable to it. If everyone can generate synthetic movie stars, then movie stars become a commodity. The scarcity value disappears. That changes the entire economics of the entertainment industry.

Certainly, some actors are leaning into the technology. They're seeing it as a tool, not a threat. They understand that if they have their own high-quality digital likenesses, they can monetize them indefinitely. They can create content without being physically present. It's a different kind of work, but potentially lucrative.

But the asymmetry is real: big-name actors can protect themselves with legal agreements and compensation. Unknown actors, background performers, voice actors—they're more vulnerable. They have less leverage to negotiate.

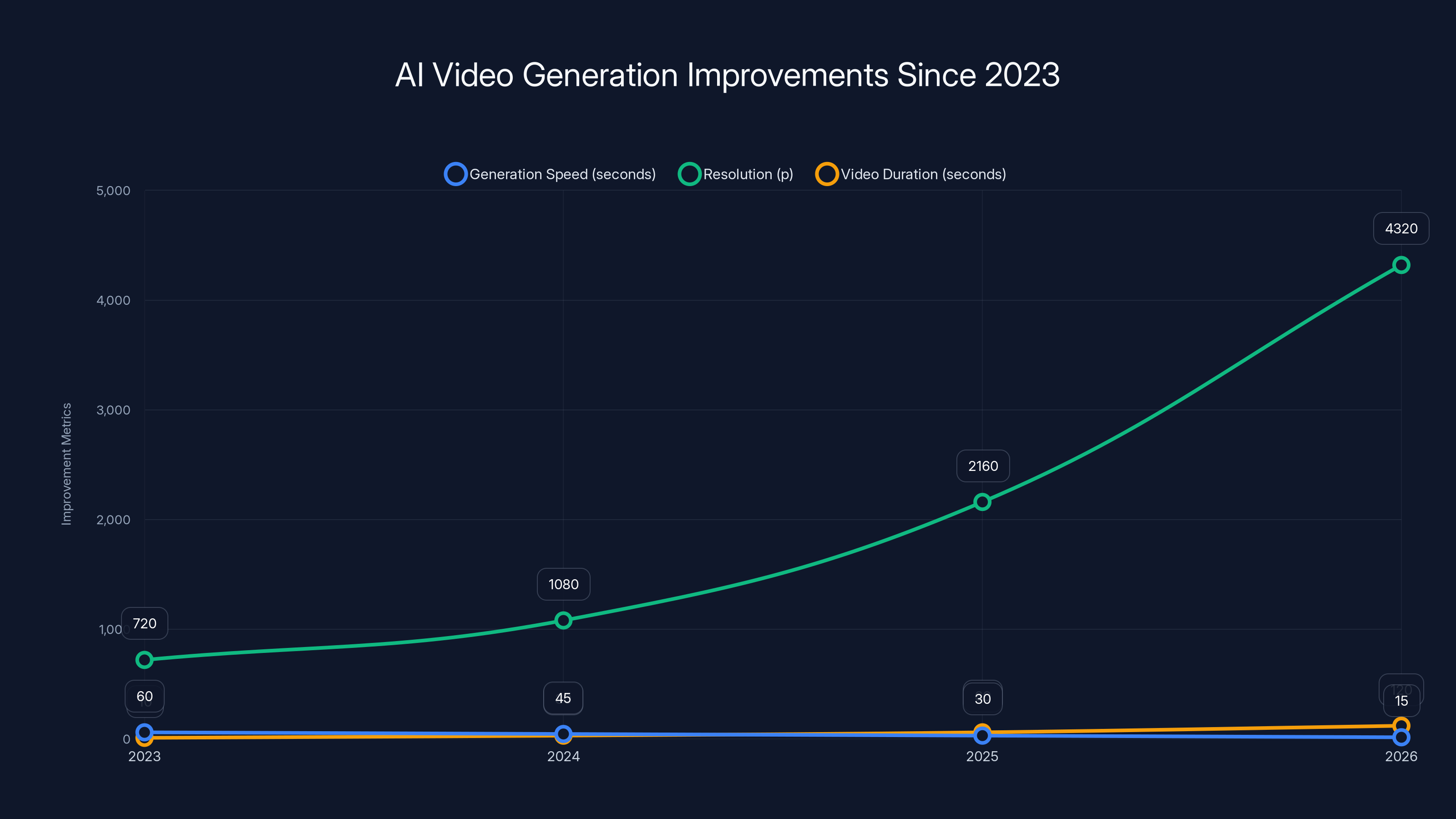

Estimated data shows exponential improvements in AI video generation from 2023 to 2026, with faster generation times, higher resolutions, and longer video durations.

The Emergence of AI-Native Media Formats

While Hollywood is still figuring out how to respond to AI video, a completely different ecosystem is emerging. We're seeing the birth of genuinely new media formats that only make sense because of AI generation. These aren't films trying to look like traditional cinema. They're something different.

Personalized video content is becoming viable. Imagine a streaming service that generates a custom action sequence just for you, tailored to your viewing preferences. Or educational content that adapts itself based on how the AI detects you're learning. These aren't science fiction. Companies are working on these now.

The economics change dramatically when you can generate content on demand. Traditional media requires massive upfront investment to produce content that you then try to sell to as many people as possible. AI-generated media requires minimal upfront cost and can be customized per user. It's a fundamentally different business model.

We're also seeing the rise of AI-assisted content creation. Professional video editors using AI tools to handle the boring parts—automatic color correction, scene detection, transition suggestions, even basic editing. The AI isn't replacing the human editor. It's giving them superpowers. A competent editor working with AI tools can produce more content, faster, with fewer errors.

Then there's the truly wild frontier: interactive synthetic video. Video that doesn't follow a predetermined script but instead responds to user input in real-time. Imagine a conversation with a synthetic version of a historical figure, or a personalized tutorial where the instructor responds to your questions. These are early days, but the pieces are in place.

Musicology and sound design are following similar trajectories. AI can generate music that matches specific moods, tempos, instrumentation. It can create unlimited variations of a soundtrack. It can adapt music in real-time based on what's happening on screen. Again, not replacing human musicians, but changing the economics of production.

The interesting thing about these new formats is that they're building entirely new expectations. A generation of viewers who grow up with AI-generated or AI-assisted content will have different standards. They won't expect the same kind of visual language as traditional cinema. They'll expect something more adaptive, more personalized, more interactive.

This is where the industry splits. Traditional media companies trying to preserve the old model. Tech companies exploring entirely new possibilities. And somewhere in between, independent creators who are using these tools to tell stories that would've been impossible to produce before.

The Quality Threshold: When Does AI Become Indistinguishable?

This is the question everyone's asking: how close are we to perfect synthetic video?

The technical answer is: we're closer than most people think, but still a ways away from true indistinguishability. There's a qualitative difference between "90% as good as real video" and "literally impossible to distinguish from real video." That final 10% requires solving a bunch of really hard problems.

The hardest problem is consistency across multiple views. If you generate a scene from one camera angle, can you generate the same scene from a different angle? Not just generate something that looks plausible from the new angle, but something that's actually consistent with the physics of the first scene? This is really hard. Current models struggle with it.

Another hard problem: hands. Human hands are insanely complex. Lots of joints. Lots of flexibility. Hands in video are doing complex things—pointing, gesturing, holding objects, interacting with other hands. Generating convincing hands is still one of the failure points of AI video. You'll often see AI-generated videos where the hands look off.

Then there's the problem of rare events. Models train on common patterns in video. People usually look at the camera. People usually have the expected number of fingers. Lighting usually follows basic physical rules. But there are edge cases. Extreme angles. Unusual lighting conditions. Rare events. The model hasn't seen enough examples to generate those convincingly.

There's also a subtler problem: bias in training data. If your training data is 80% people of one ethnicity, your model will generate that ethnicity more convincingly than others. If your training data is mostly people with certain body types, you'll struggle with others. These aren't just fairness issues. They're technical issues that limit the quality of generation.

But here's the thing: none of these are fundamental blockers. They're engineering problems. Solvable with more compute, better algorithms, better data. Given the rate of progress, I'd estimate we'll hit genuinely indistinguishable synthetic video within 3-5 years. Maybe sooner. Not "good enough that some people won't notice." Actually indistinguishable.

When we cross that threshold, things change. It's not a gradual change. It's a phase transition. The moment your synthetic video is literally indistinguishable from real, the entire concept of "video as evidence" becomes problematic. You can't just show someone a video and expect them to accept it as proof of something.

This is where we need to be thinking about solutions now, not after the problem hits us. We need better approaches to authenticating content. Better verification methods. Better legal frameworks for how video evidence works. Better media literacy so people understand the risks.

The Will Smith spaghetti video was a wake-up call. But we're still snoozing. The actual alarm—the moment when synthetic video becomes indistinguishable—is going to be much louder.

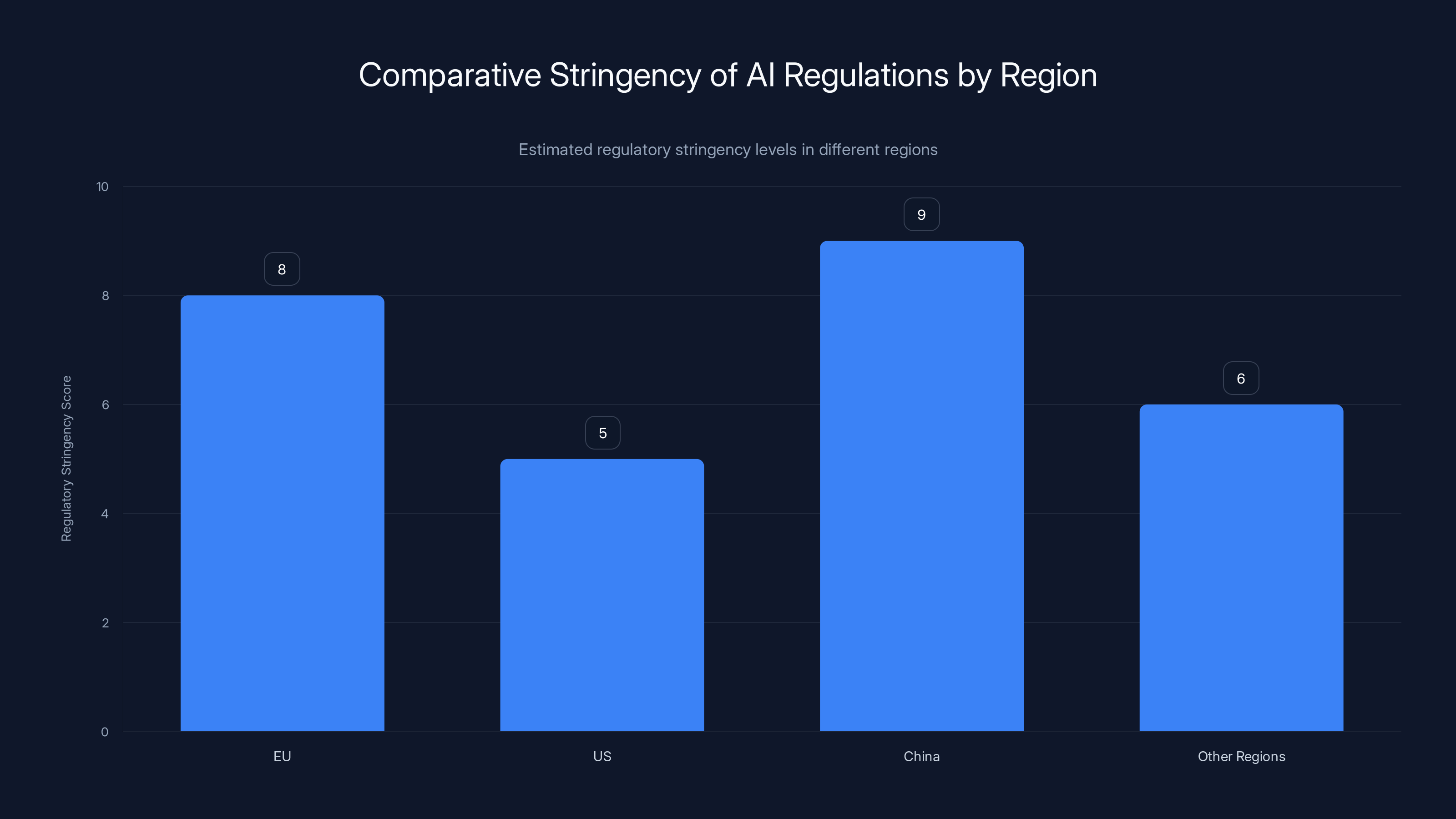

Estimated data suggests China and the EU have stricter AI regulations compared to the US, which takes a more hands-off approach. This impacts global platforms' compliance strategies.

Runable and the Future of Content Creation

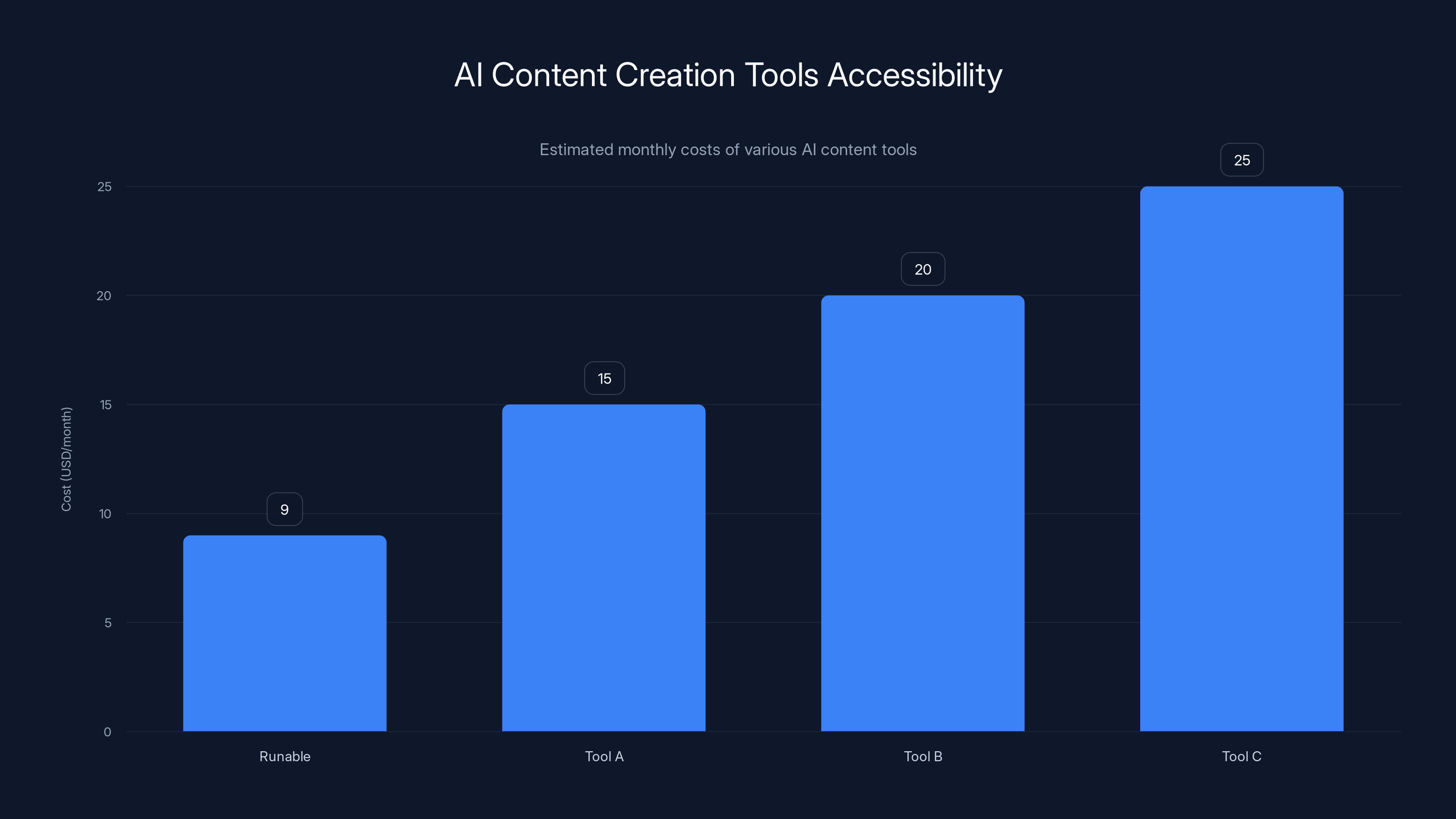

One interesting player in this space is Runable, which offers AI-powered automation for creating presentations, documents, reports, and other content formats. While not specifically focused on video generation, Runable represents the broader trend of AI tools democratizing content creation. At $9/month, it shows how AI-powered automation is becoming accessible to teams of all sizes.

The logic extends to video: as generation tools improve and become more accessible, the barrier to entry for content creation drops dramatically. This is good for creators. It's potentially problematic for authentication and trust.

The Detection Problem We Can't Solve

Let's address the elephant in the room: we probably can't detect AI-generated video long-term.

The reason is fundamental to machine learning. Detection relies on finding statistical patterns that distinguish real from generated. But generative models are specifically designed to match the statistical patterns of real data. As generators improve, they become harder to distinguish.

It's like an infinite arms race. You publish a detection method. Generators improve to fool your detector. You publish a better detector. Generators improve again. Theoretically, this continues until generated and real data are indistinguishable (at which point detection becomes impossible by definition).

Some researchers are exploring alternative approaches. Cryptographic signatures on video. Blockchain-based verification. Hardware-level authentication where the camera itself signs the footage. But these require infrastructure. They require adoption. They require coordination across platforms.

The more realistic approach: accept that you can't detect all deepfakes, and instead build resilience into institutions. Legal standards for video evidence that account for the possibility of deepfakes. Redundant authentication methods. Social context and corroboration. Multiple sources. Institutional skepticism.

This is a messy solution. It's not as satisfying as "we'll just detect fakes." But it's more realistic. Society has dealt with forged documents, manipulated photographs, false testimony for centuries. We've developed approaches. The same approaches—skepticism, corroboration, institutional verification, legal standards of proof—apply to video.

The Will Smith spaghetti video was useful because it was detectably fake. It taught us something without causing harm. By the time we reach indistinguishable synthetic video, we need to have moved beyond relying on detection. We need better institutions.

Runable offers one of the most affordable AI-powered content creation tools at $9/month, highlighting the trend of accessible AI tools. Estimated data for comparison.

The Consent Problem

One aspect that doesn't get enough attention: the question of consent. Creating a synthetic video of someone without their permission is becoming increasingly easy. And it's increasingly hard for that someone to prove it's synthetic.

There are obvious cases: non-consensual synthetic intimate imagery. This is already a problem. Deepfake pornography using celebrities' faces has been produced and distributed. The legal status is still murky in many jurisdictions, but the technology is clearly being weaponized.

But the problem is broader. Creating a synthetic video of someone saying anything requires only their face and voice. You can train a model on publicly available footage. You can generate them saying things they never said. The person has no control over this. They don't know it's happening until someone shows them the fake video.

This is particularly problematic for public figures. A politician could find synthetic footage of themselves making inflammatory statements, and by the time they deny it, the damage is done. The denial itself becomes suspicious (obviously they'd deny it). The synthetic version of events becomes the accepted narrative.

Legal protections are starting to emerge. Various jurisdictions are passing laws against deepfake pornography. Some are considering broader protections against non-consensual deepfakes. But the legal system moves slowly. The technology moves fast.

What's needed is a norm-shift. We need to build a cultural understanding that synthesizing someone's likeness without permission is wrong. Not just legally wrong, but ethically wrong. The same way we've built norms against defamation, privacy violation, and harassment.

But norms take time to establish. By the time we've established strong norms against non-consensual deepfakes, the technology will have moved on to new problems we haven't thought of yet.

The Economic Disruption

Let's talk about jobs. AI video generation is going to affect employment in significant ways.

The most obvious impact: background actors and extras. If you can generate crowd scenes synthetically, why hire 100 extras? You save money on hiring, insurance, catering, scheduling. The economics are simple. Background acting jobs will become scarcer.

Stunt coordinators and stunt performers face similar pressures. If you can synthetically show someone doing a dangerous action, why hire and insure a real stunt person? The risks disappear. The costs drop dramatically.

Voice actors might see reduced demand for some types of work. Audiobook narration, commercial voiceovers, video game dialogue—these could be generated. A professional voice actor provides nuance and artistry that current AI can't fully replicate, but the difference is shrinking.

Animators and VFX artists are already dealing with this. Some studios are using AI tools to accelerate parts of the animation pipeline. A hand-drawn sequence that used to take weeks might now take days, with AI assistance handling the routine frames.

But here's the interesting part: as with most technological disruptions, new jobs are being created alongside the old ones disappearing. Someone needs to operate the AI video generation tools. Someone needs to supervise and refine the output. Someone needs to handle edge cases where the AI fails. New roles are emerging.

The workers most vulnerable are those with the least leverage: extras, junior animators, freelance voice actors. The workers with the most leverage—established actors, senior animators, creative directors—are more likely to find their work augmented rather than replaced.

This is classic technological disruption. Not everyone is harmed equally. Adjustment is painful for some while others benefit. The challenge is managing the transition so it doesn't devastate communities that depend on these jobs.

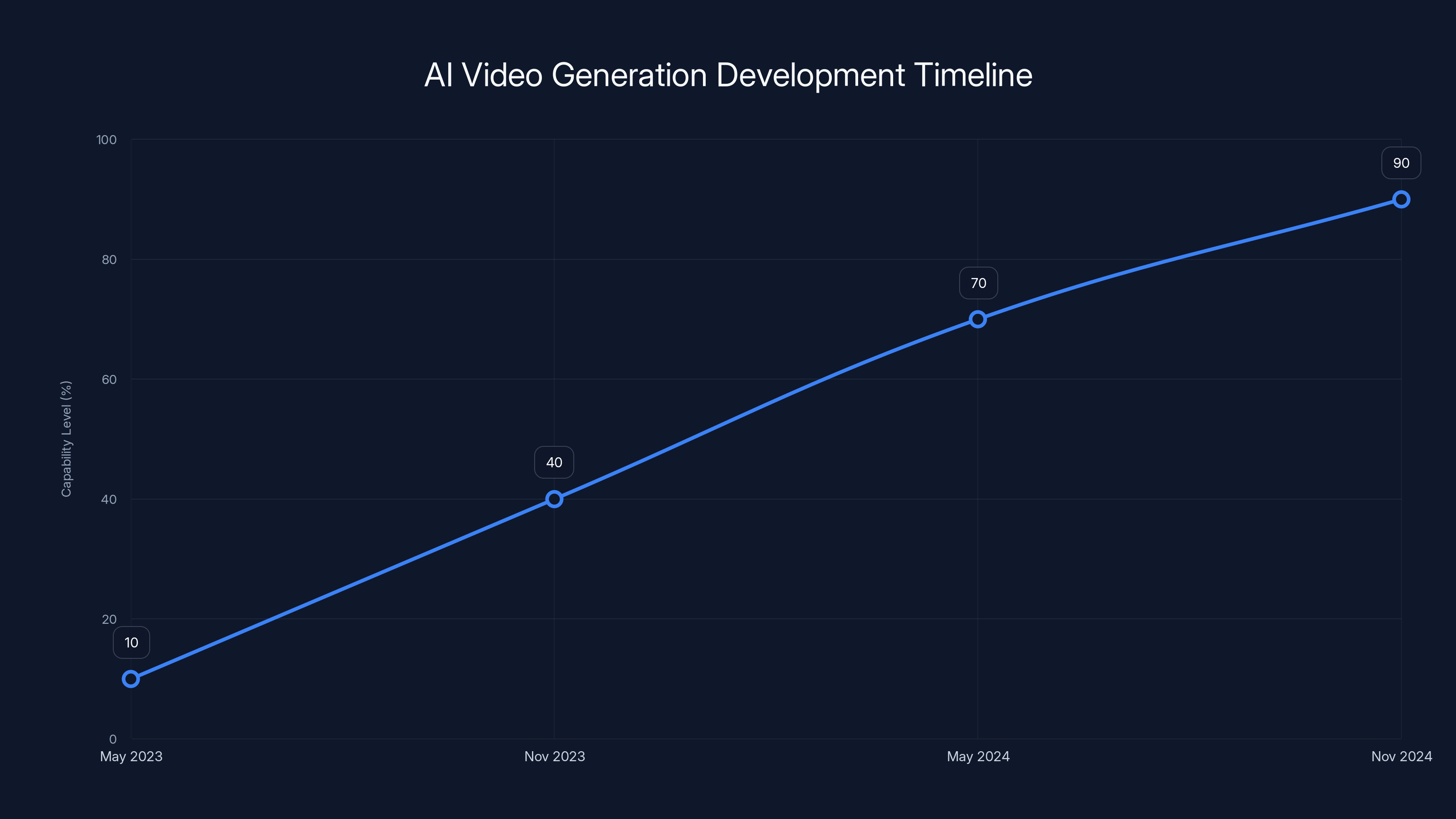

Estimated data shows rapid development of AI video generation, with capability increasing from 10% to 90% in 18 months.

The Regulatory Landscape

Governments are starting to pay attention. The EU's proposed AI regulations explicitly address generative AI. The US is contemplating various regulatory approaches. Countries around the world are grappling with how to govern this technology.

The challenge is balancing innovation with safety. Too much regulation and you stifle the development of beneficial applications. Too little and you enable harmful ones.

Some of the proposed regulations are obvious: requiring disclosure of AI-generated content. If something is synthetic, you have to say so. This seems reasonable, but it's harder to enforce than it sounds. How do you verify compliance? What's the penalty for non-compliance? Who investigates?

Other proposals: licensing for advanced video generation tools. Only authorized users can create synthetic video. This immediately collides with free speech concerns. Criminalizing non-consensual deepfakes. This is more obviously justified, but defining the boundaries is tricky. Does parody count? Political commentary? News reporting of a deepfake?

The regulatory approaches vary by jurisdiction. The EU is taking a stricter approach. The US is more hands-off, relying on existing laws and market forces. China is implementing strict controls. The result is a patchwork of different standards.

This patchwork creates problems for international platforms. If you're building a video generation service and operating globally, you need to comply with the strictest regulatory environment you operate in. This tends to raise standards across the board, which is good for safety but bad for innovation velocity.

The regulations that will actually matter are the ones that address liability. If you create a synthetic video that causes harm, who's responsible? The person who created it? The platform that hosted it? The tool provider? The answer will shape how the entire ecosystem develops.

From Chaos to Capability: The Path Forward

So where does this leave us? The Will Smith spaghetti video marked the moment when AI-generated video became a thing people noticed. It was novelty. It was funny. It was obviously fake.

That moment has passed. We're no longer in the novelty phase. We're in the transition phase. The technology is becoming good enough that it requires serious thought about implications. It's becoming integrated into workflows. It's becoming normal.

The next phase—indistinguishable synthetic video—is where things get genuinely serious. That's when the technology stops being a curiosity and starts being a threat. That's when jokes about Will Smith eating spaghetti become something darker.

But between now and then, we have a window. A moment when the technology is good enough to be useful but still obviously artificial enough that we can maintain healthy skepticism. This is the moment to build safeguards. To establish norms. To create legal frameworks. To prepare institutions.

The technology itself isn't going anywhere. Moore's Law and the economics of AI ensure continued improvement. But the way we respond to that technology is still being determined. The choices made now—about regulation, about cultural norms, about institutional practices—will shape how this evolves.

Hollywood is already adapting. Tech companies are already deploying the tools. Workers are already facing disruption. The time to think carefully about implications was probably a year ago, but the next-best time is now.

The Will Smith spaghetti video was chaos. But it was useful chaos. It caught our attention. It made abstract concepts concrete. It gave us a meme to rally around while discussing something that matters.

The videos we'll be dealing with in three years won't have that luxury. They won't announce themselves as fake. They'll look real. Sound real. Feel real. And we'll need to have figured out how to handle that by then.

FAQ

What was the Will Smith eating spaghetti video?

The "Will Smith eating spaghetti" video was an AI-generated video released in May 2023 that showed the actor consuming oversized pasta in obviously artificial ways. The video went viral because it was hilariously fake—proportions were wrong, movements were unnatural, and physics didn't apply—making it the perfect symbol for early-stage AI video generation. It became an accidental benchmark for measuring how quickly the technology was improving.

Why did the spaghetti video become so important?

The video mattered because it crystallized something abstract into something concrete. AI video generation was a theoretical concern. The spaghetti video made it a real thing you could point to, share, and react to. It became a cultural reference point for tracking AI progress. Because it was obviously fake, it also demonstrated that we could still easily identify synthetic video—a reassurance that turned out to be temporary as the technology rapidly improved.

How has AI video generation improved since 2023?

Improvements have been exponential across multiple dimensions. Models now generate video much faster (seconds instead of minutes). Resolution is higher (4K instead of 720p). Duration is longer (full minutes instead of a few seconds). Physics simulation is better, so objects interact realistically with people and environments. Facial animations are more natural. The overall coherence and consistency across frames has dramatically improved. The technology has essentially moved from novelty to professional capability.

Can you currently detect AI-generated video?

Not reliably. While detection tools exist, they're in an arms race with generation tools. As generators improve, detection becomes harder. Current detectors might catch obviously synthetic video, but increasingly realistic generations fool them. The long-term outlook is pessimistic for detection—as generated video becomes indistinguishable from real, detection becomes theoretically impossible. Better approaches involve cryptographic verification and institutional skepticism rather than automated detection.

What are the main concerns with advanced AI video generation?

The primary concerns include non-consensual deepfakes (sexual imagery, fabricated statements), misinformation and political manipulation (fake statements by public figures), fraud and financial crimes (faked videos used in scams), job displacement (especially for background actors and VFX artists), and challenges to video as evidence in legal contexts. There's also the consent problem—people don't control whether their likeness is used to generate synthetic video.

What legal protections currently exist?

Legal protections vary significantly by jurisdiction. Some countries and regions have banned non-consensual deepfake pornography. General defamation and fraud laws may apply to synthetic video used maliciously. Copyright laws might protect against using someone's likeness without permission. However, the legal landscape is still developing, and many potential harms fall into gray areas. Laws lag significantly behind technology.

How is Hollywood responding to AI video generation?

Hollywood is taking a dual approach: investing in proprietary AI tools while simultaneously negotiating labor protections. Major studios are developing in-house synthetic video capabilities. Actors' unions are negotiating for restrictions on synthetic replacement and compensation for digital likenesses. The outcome is still being determined, but studios are clearly treating AI as a strategic advantage while workers seek protections against job displacement.

What's the timeline for indistinguishable synthetic video?

Based on current progress rates, genuinely indistinguishable synthetic video is probably 3-5 years away. This would represent video that experts couldn't distinguish from real through visual analysis alone. Some specialized domains might get there sooner (talking-head videos, for example). The timeline could accelerate with major algorithmic breakthroughs or slow if fundamental limitations prove harder than expected.

What should society do to prepare for this technology?

Society needs parallel approaches: institutional preparation (updating legal standards for video evidence, developing verification methods), cultural preparation (building norms against non-consensual synthetic content), technical preparation (exploring cryptographic verification and authentication methods), and labor transition (helping displaced workers retrain). Most importantly, we need ongoing dialogue between technologists, policymakers, workers, and the public about how to govern this responsibly.

How does AI video generation connect to other AI tools?

AI video generation is part of a broader ecosystem of AI content generation tools. Similar to how Runable democratizes the creation of presentations, documents, and reports through AI automation, video generation tools are democratizing video creation. The underlying principles are similar: reducing barriers to entry, enabling creation at scale, and shifting human effort from routine generation to creative direction and refinement.

Conclusion: Living With a Technology That Changed Faster Than Expected

The Will Smith spaghetti video was supposed to be a funny story. A meme. A glimpse at the absurdity that AI video generation could produce. It turned out to be something more important: a timestamp on the accelerating development of synthetic video technology.

In the span of roughly 18 months—from May 2023 to late 2024—AI video generation went from novelty to capability. Not the fully-realized, perfect capability of truly indistinguishable synthetic video, but capability that's rapidly approaching that threshold. The pace has been genuinely surprising to most observers.

What's remarkable is that the spaghetti video, as obviously fake as it was, captured something true: the moment when AI-generated content stopped being a theoretical concern and became a practical reality. Not a threat yet—it wasn't convincing enough for that—but a signal that the threat was coming.

We're now in that intermediate space. The technology is good enough that it could cause real harm. It's not yet good enough that we're helpless to verify authenticity. This is the window where preparation matters most. This is when we build safeguards, establish norms, create legal frameworks.

The challenge is that we're preparing for a future we can't quite see clearly. We don't know exactly how the technology will develop. We don't know which use cases will become prevalent. We don't know how society will adapt. We're building institutions and rules for a technology that's still moving.

But that's been true of every transformative technology. The printing press. Photography. Radio. Television. The internet. We never fully understand the implications when the tech is new. We learn as we go. We adapt. We adjust rules. We discover problems and solve them.

The difference with AI video generation is the pace. Everything is compressed into a shorter timeline. The window to prepare is narrower. The consequences of being unprepared are more severe. We don't have the luxury of slow, deliberate institutional change.

So what can individuals do? Pay attention. Maintain healthy skepticism about video. Think about the implications—not just for yourself but for society. Support stronger verification methods. Understand the technology well enough to make informed decisions about when and how to trust video. Contribute to conversations about how this should be governed.

And remember: the absurd spaghetti-eating Will Smith video wasn't really about Will Smith. It was never about spaghetti. It was a warning encoded in a joke. A message from the future, delivered in the only way early AI could manage: as obvious chaos that made us laugh before we understood why we should be concerned.

We understood. The question now is whether we're preparing adequately for what comes next.

TL; DR

-

The Benchmark Moment: The viral "Will Smith eating spaghetti" video from May 2023 became an accidental metric for tracking how quickly AI video generation was improving, marking the shift from novelty to genuine capability.

-

Exponential Progress: In just 18 months, AI video generation evolved from obviously fake (with weird proportions and physics violations) to photorealistic, handling improved temporal coherence, facial expressions, and environmental interactions.

-

The Detection Problem: Current deepfake detectors are losing the arms race as generators improve. Perfect detection may be impossible once video becomes truly indistinguishable from real footage, requiring instead better verification methods and institutional safeguards.

-

Hollywood in Transition: Studios are investing in proprietary AI video tools while simultaneously negotiating labor protections with unions about synthetic actor replacement and compensation for digital likenesses.

-

3-5 Year Threshold: Genuinely indistinguishable synthetic video is probably 3-5 years away, representing a phase transition where society will need new legal, institutional, and cultural approaches to verify authenticity and prevent misuse.

-

Bottom Line: The Will Smith spaghetti video was useful because it was obviously fake. By the time synthetic video becomes realistic, we need to have established norms, legal frameworks, verification methods, and institutional practices to handle the implications responsibly.

Key Takeaways

- AI video generation progressed from obviously fake (May 2023) to photorealistic in 18 months, an exponential acceleration beyond most predictions

- Diffusion models with temporal coherence constraints and integrated physics simulation represent the core technology breakthrough enabling improved synthetic video

- Detection of deepfakes is losing the arms race as generators improve, suggesting detection may be theoretically impossible once video becomes truly indistinguishable from real

- Hollywood is simultaneously investing in proprietary AI video tools while negotiating labor protections, creating tension between economic incentive and worker protection

- Society has a 3-5 year window before genuinely indistinguishable synthetic video becomes standard, requiring preparation of legal frameworks, verification methods, and institutional safeguards

- Consensus-building around norms against non-consensual deepfakes and adoption of cryptographic verification are more realistic long-term solutions than detection technology

Related Articles

- Why AI-Generated Super Bowl Ads Failed Spectacularly [2026]

- How Darren Aronofsky's AI Docudrama Actually Gets Made [2025]

- Google's AI Plus Plan Now Available Globally at $7.99/Month [2025]

- X's Grok Deepfakes Crisis: EU Investigation & Digital Services Act [2025]

- Can't Tell Real Videos From AI Fakes? Here's Why Most People Can't [2025]

- Higgsfield's $1.3B Valuation: Inside the AI Video Revolution [2025]

![Will Smith Eating Spaghetti: How AI Video Went From Chaos to Craft [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/will-smith-eating-spaghetti-how-ai-video-went-from-chaos-to-/image-1-1770727218214.jpg)