How AI Filmmaking Really Works: The Truth Behind Darren Aronofsky's 1776 Project

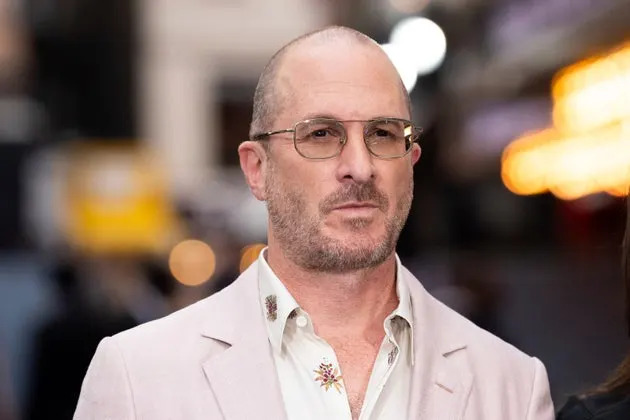

When filmmaker Darren Aronofsky released the first episodes of On This Day... 1776 in early 2026, the internet had a meltdown. Critics called it "AI slop," "hellish," and "ugly as sin." Social media roasted the photorealistic avatars of Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Paine. Nobody wanted to watch AI-generated historical figures recite dialogue.

But here's what almost nobody talked about: the insane amount of human work happening behind those AI-generated scenes.

Aronofsky's studio, Primordial Soup, partnered with Time magazine and a team of writers, voice actors, editors, and visual effects specialists to create something that looks simple on screen but takes weeks to produce. That's the real story nobody's telling.

I spoke with production sources close to the project who revealed exactly how this works. It's not what you'd think. It's messier, slower, and way more human than the marketing suggested. It's also a fascinating glimpse into what AI filmmaking actually looks like in 2025, not the fantasy version tech companies sell you.

So let's talk about why Aronofsky thought this was a good idea, how it actually works, what critics got wrong, and where this technology is actually headed.

TL; DR

- Each minute of finished video takes weeks to produce, not hours like some assume, because AI video generators require constant iteration and refinement.

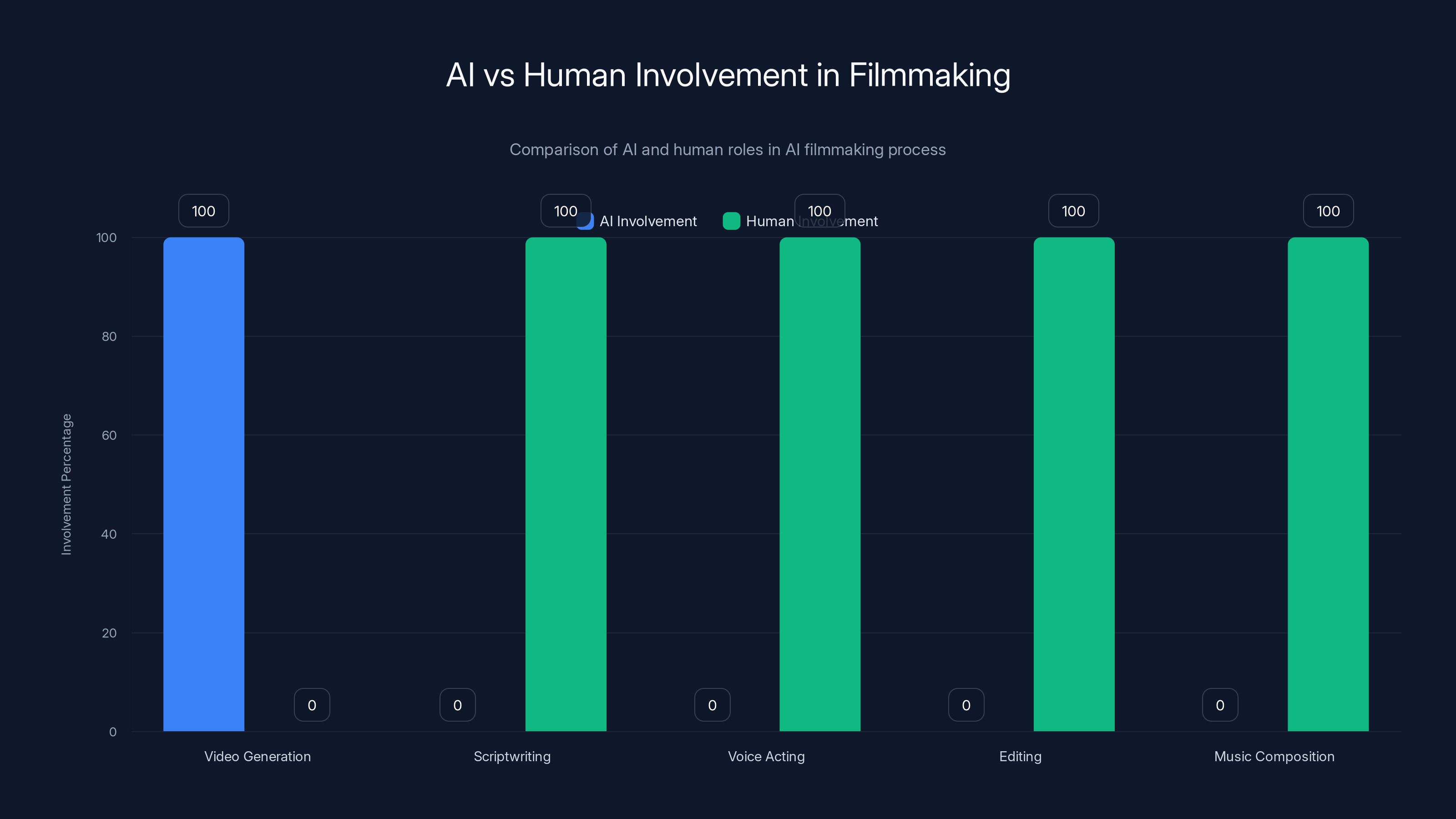

- Human writers, voice actors, editors, and VFX artists do most of the work—AI handles visual generation only, everything else is traditional filmmaking.

- AI rarely produces screen-ready shots on the first try, forcing teams to re-prompt the model dozens of times to achieve desired results.

- Critics misunderstood the project by assuming dialogue was AI-written, when scripts came from professional writers and union voice actors recorded all dialogue.

- The technology is evolving faster than the tooling, meaning production processes will improve dramatically as AI models get better at following creative direction.

AI is primarily used for video generation, while humans handle all other creative and technical tasks in AI filmmaking.

Why A-List Director Chose AI Filmmaking (And Not Why You Think)

Darren Aronofsky doesn't need shortcuts. The guy directed Black Swan, The Wrestler, and Mother. He's not some tech bro trying to cut corners. So why would he spend months on an AI filmmaking experiment?

Turns out, it's not about replacing craft. It's about accessing something impossible before.

Traditional historical documentaries have constraints. You need locations. You need historical accuracy in every background detail. You need to find or recreate costumes, sets, and architecture from the 1700s. That's expensive, slow, and sometimes impossible because the locations don't exist anymore or are protected sites.

With AI video generation, Aronofsky's team could paint historical scenes with photorealistic detail without scouting actual locations or building physical sets. They could iterate on a single shot hundreds of times until the lighting, composition, and character positioning felt exactly right.

That's actually a legitimate creative tool. Not revolutionary, but legitimate.

Time Studios President Ben Bitonti positioned it as exactly that in the announcement: "a glimpse at what thoughtful, creative, artist-led use of AI can look like—not replacing craft but expanding what's possible."

Sounds good in theory. The execution part is where things got messy.

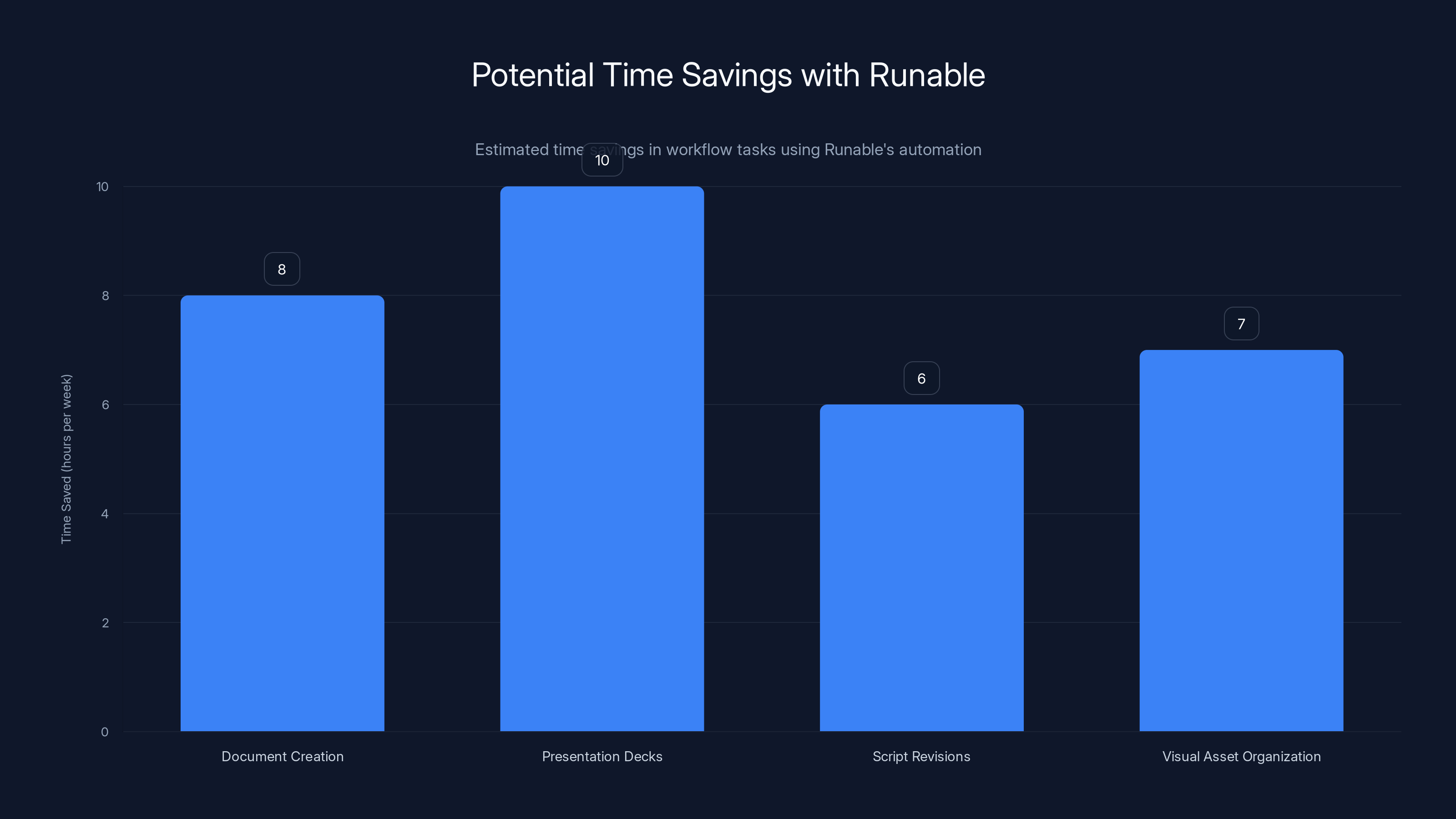

Estimated data suggests that using Runable could save significant time across various production tasks, allowing teams to focus more on creative processes.

The Script Came From Humans (And Yes, That Matters)

Let's clear something up because critics got this spectacularly wrong.

Every piece of dialogue in On This Day... 1776 was written by humans. Not Chat GPT. Not some generative AI trained on screenplays. Actual writers working under Aronofsky's longtime collaborators Ari Handel and Lucas Sussman.

That detail matters because it changes what you're actually critiquing. When The Guardian complained about "Chat GPT-sounding sloganeering," they were roasting professional screenwriters, not AI. Whether that's fair criticism of the writing itself is debatable. But calling it AI-generated dialogue is just factually wrong.

Production sources confirmed the project was always conceived as a human-written effort. The team spent months planning and researching how to tell a year-long story about the American Revolution. They studied primary sources, historical accounts, and archival documents. They made specific creative choices about which moments mattered, how to frame them, what dialogue would feel authentic.

When the scripts were finalized, professional voice actors from the Screen Actors Guild recorded every single line of dialogue. Not AI voices. Not deepfakes. Union actors reading scripts.

Now, were those scripts good? That's a separate question entirely. Critics seemed to think they were clunky and generic. Maybe they were. But that's a screenwriting critique, not an AI critique.

Where The AI Actually Shows Up

Here's the part that gets confusing because of how tech companies market this stuff.

The AI doesn't write. The AI doesn't voice act. The AI doesn't edit or color-correct or mix sound.

The AI generates video shots. That's it. That's the only place artificial intelligence touches the workflow.

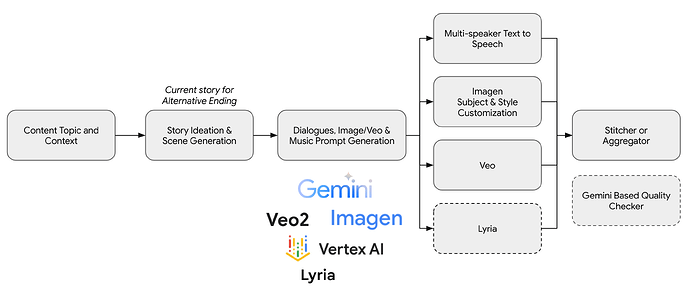

In practice, this is how it works:

Step one: Human storyboarding. The production team creates detailed storyboards for each scene, deciding camera angles, character positioning, and action beats. This is traditional filmmaking work. Storyboard artists draw or digitally create these visuals.

Step two: Reference collection. Production designers find visual references for locations, lighting, character appearances, and props. They gather images of how light falls on walls, how fabrics drape, how architectural details look in different times of day.

Step three: AI prompt development. The team takes all that information—storyboards, references, script—and translates it into prompts for an AI video generator. This is like writing detailed directions for a concept artist.

Step four: AI generation. The model produces a video shot. Sometimes it nails it. Most times it doesn't.

Step five: Iteration loop. The team watches the output and decides what to change. Then they re-prompt the model with adjusted instructions. And again. And again.

Step six: Post-production. Humans take the AI-generated footage into traditional editing, visual effects, color correction, and sound mixing. They fix artifacts, patch problem areas, adjust timing, and blend everything together.

Only step four is AI. Everything else is traditional filmmaking work.

Production sources said the early episodes used "a combination of traditional filmmaking tools and emerging AI capabilities." That phrasing is doing a lot of work. The reality is mostly traditional filmmaking, with AI handling one specific task.

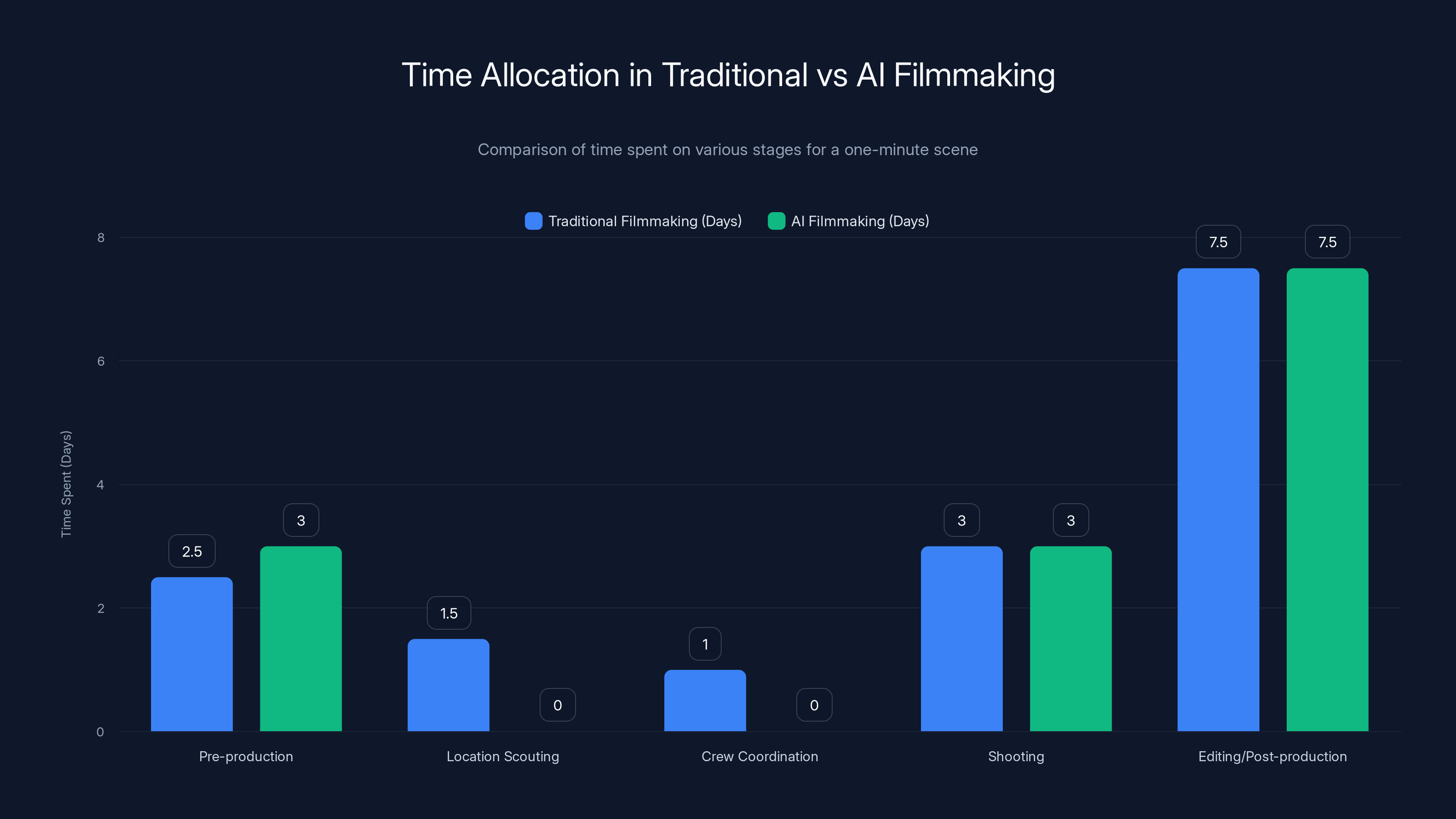

Both traditional and AI filmmaking take approximately the same time for a one-minute scene, but the tasks differ significantly. Estimated data.

Why Weeks? The Iteration Problem Nobody Talks About

Here's where the fantasy of AI filmmaking crashes into reality.

If you read the marketing, you'd think AI video generation would be faster than traditional filmmaking. Generate a scene in minutes instead of scouting locations, renting equipment, hiring crews, and shooting for days.

That's true in theory. In practice? Weeks per minute of finished video.

The bottleneck is iteration. AI video models don't have fine-grained control. You can't tell them "move the character's hand two inches to the left." You can't say "make that shadow softer." You describe what you want in text, the model takes your input, and it generates something.

Sometimes that something matches what you wanted. Usually it doesn't. Not because the AI is broken, but because the gap between human creative intent and what a text-to-video model can do is still enormous.

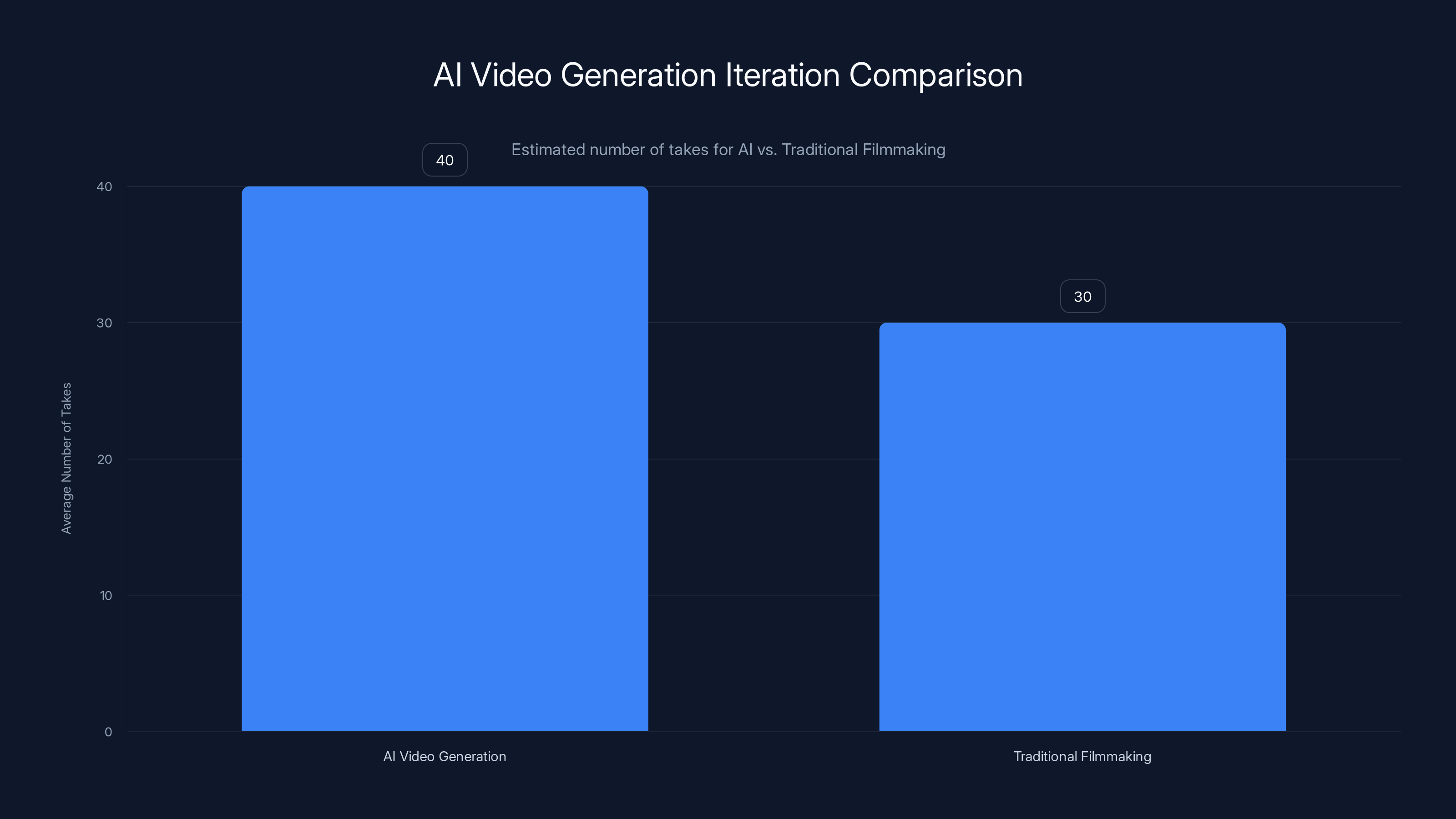

Production sources said: "You don't know if you're gonna get what you want on the first take or the 12th take or the 40th take."

Forty takes. That's not unusual.

And each take takes time. You re-prompt the model, wait for generation, review the output, assess what's wrong, modify your prompt, generate again. Repeat dozens of times.

Some shots came together quickly. Most didn't. The team started pushing deadlines regularly.

This is actually more like traditional live-action filmmaking than computer animation. When you shoot live action, you might do thirty takes of one scene to get what the director wants. You're iterating, refining, trying different approaches. Same thing here, except the "actor" is an AI model and the "location" is a generated environment.

When small issues appeared in a generated shot, the team sometimes fixed them in post with visual effects. But most of the time, they just went back and asked the AI to generate a completely new version with small adjustments.

The Music, Editing, Effects—All Human

When critics complained about the "ugly" look and "waxen" characters, they were mostly reacting to the AI-generated footage itself. But they should have been aware of how much work surrounded it.

Every note of music was composed and scored by humans. Every edit decision—timing, pacing, transitions—came from human editors. Every visual effect, color grade, and sound mix came from professional VFX artists and sound engineers.

This is traditional post-production in its entirety. The only difference is the raw footage coming in came from an AI instead of a film camera.

Think of it like this: if you handed a cinematographer's footage to an editor who then destroyed the footage in post-production, you wouldn't blame cinematography. You'd blame the editor. Same concept applies here. The AI generated the visuals, but humans shaped everything else that makes video feel cinematic.

Production sources confirmed all of this: "Humans are directly responsible for the music, editing, sound mixing, visual effects, and color correction."

The only place the AI-powered tools come into play is in the video generation itself. Everything before and after is humans doing their jobs.

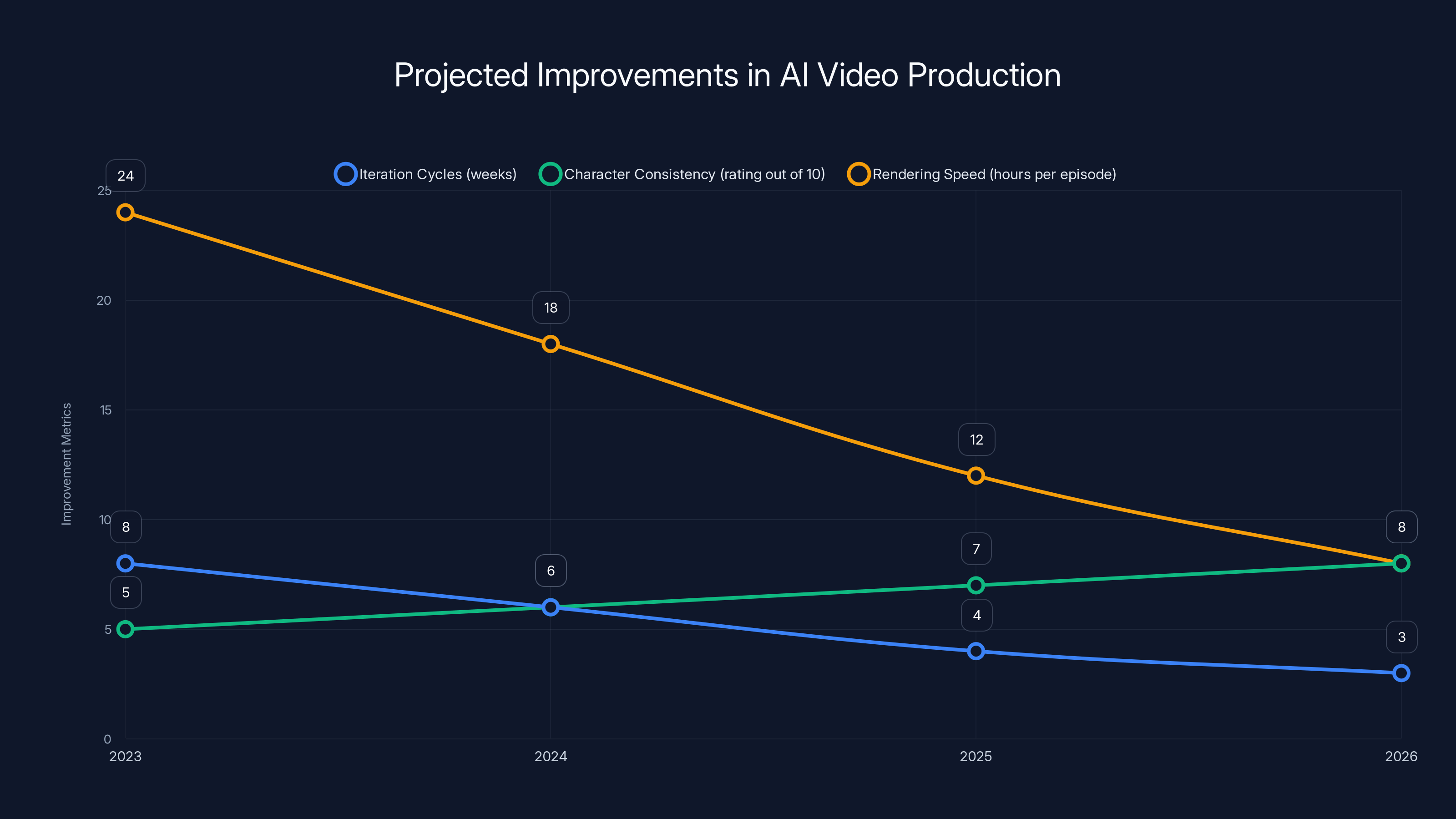

As AI models improve, iteration cycles are expected to shorten, character consistency to enhance, and rendering speeds to increase. Estimated data based on typical technological advancements.

What Critics Got Right And Wrong

Let's be fair to the critics because some of their complaints were valid.

They were right about: The videos had visible problems. Repetitive camera movements. Characters that looked uncanny. Composition that felt flat. Lighting that seemed artificial in ways that pulled you out of immersion. These are legitimate creative critiques.

They were wrong about: Assuming AI wrote the scripts, assuming AI voiced the characters, assuming this was a shortcut that replaced traditional craft, and assuming the project wasn't improving throughout the year.

The AV Club called out "repetitive camera movements." That's probably a creative choice, not a technical limitation. Directors using AI can only iterate on what the model generates. If the model keeps generating similar camera angles, the director can adjust the prompt or try different references. But if the director decided to use repetitive movements for thematic reasons? That's not an AI failure. That's a creative choice that didn't land.

The Guardian said the series was "embarrassing." Fair opinion. But then called it "AI slop" and criticized "Chat GPT-sounding sloganeering." The first part is debatable taste. The second part is factually incorrect criticism applied to professional screenwriters.

CNET's headline about "AI slop ruining American history" is actually interesting because it implies AI videos can ruin history. They can't. Bad storytelling can. Poor research can. Insensitive creative choices can. But the medium—whether shots come from a camera or an AI model—doesn't determine historical accuracy.

Production sources acknowledged the early episodes had problems and predicted they'd improve as the team learned to better use the tools and as the models themselves evolved. That's actually a reasonable expectation. You don't master a new creative tool in your first attempt.

The Technology Actually Improved

Here's the thing critics didn't give the project time to prove: iteration and improvement.

Production sources said from the beginning: "We're going into this fully assuming that we have a lot to learn, that this process is gonna evolve, the tools we're using are gonna evolve."

They were explicit about expecting mistakes and expecting to get better. They planned to watch how audiences reacted, figure out what worked and what didn't, and adjust accordingly.

That's how you use emerging technology responsibly. Not pretending it's perfect on day one, but committing to improvement and transparency.

The team also planned to evolve the production process as AI models improved. If the next generation of video models offered finer control, they could reduce iteration cycles. If the models got better at character consistency, they might need fewer takes to nail performances. If rendering speeds improved, they could produce episodes faster.

These aren't magic bullets. But they're realistic improvements that would happen naturally as the technology matured.

AI video generation often requires more iterations (around 40 takes) compared to traditional filmmaking (around 30 takes), highlighting the iteration problem in AI-driven processes. Estimated data.

A Year-Long Experiment With Real Constraints

Let's be honest about what this project actually was: an experiment with built-in expectations for learning and evolution.

Time magazine and Aronofsky committed to releasing episodes for an entire year, which meant they'd have real feedback from audiences, evolving tools, and growing experience with the production process. The early episodes being rough isn't a failure. It's a baseline.

Compare this to how most AI tools get released: slick marketing, overhyped capabilities, massive backlash when reality doesn't match promises. This project did something different. It said, "Here's what we're trying. It's imperfect. We'll get better."

That's actually admirable, even if the early output was mediocre.

The year-long format also created an interesting timeline for audience reception. Initial reviews were brutal. But if later episodes showed visible improvement—and production sources believed they would—the narrative shifts. Suddenly it's not a failed experiment. It's a learning process.

Critics had strong emotional reactions to the first episodes and didn't give the project room to evolve. That's fair criticism as cultural commentary. But it's not criticism of whether the experiment itself was sound.

Why The "Weeks Per Minute" Problem Actually Matters

Here's the real issue with AI filmmaking right now: it's not faster than traditional methods for anything except maybe very specific applications.

Traditional film production for a one-minute scene might take:

- 2-3 days of pre-production planning

- 1-2 days of location scouting

- 1 day of crew coordination

- 2-4 days of shooting

- 5-10 days of editing and post-production

That's roughly two weeks of calendar time, but a lot of that is parallel work (crew can prep while location scouts are running, etc.).

AI filmmaking for a one-minute scene takes:

- Several days of storyboarding and reference gathering

- Hours or days of prompt engineering and testing

- Days of iterating with the AI model (sometimes dozens of versions)

- Days of editing and post-production

Total: also roughly weeks of calendar time, but most of it is waiting for AI generation and reviewing output.

So you're not saving time. You're replacing one set of constraints with a different set of constraints. No location scouting, but lots of iteration. No crew coordination, but lots of prompt refinement.

The real advantage isn't speed. It's access. You can film scenes that would be logistically impossible or prohibitively expensive with traditional methods. You can iterate on composition and lighting without re-shooting. You can explore creative possibilities without committing massive resources.

That's the honest case for AI filmmaking. Not "faster." Not "cheaper." But "different constraints that enable different creative choices."

The Voice Actor Issue And What It Reveals

Production sources mentioned that early AI voice generators produced noticeably artificial voices that weren't ready for professional production. That's why the team went with union voice actors instead.

This is interesting because it shows the limits of current AI and the gaps in marketing claims. Text-to-speech models have improved dramatically, but they're still not indistinguishable from human actors for professional film and television work.

The union also played a role. SAG-AFTRA negotiated new language about synthetic voice actors, and studios had to comply. Primordial Soup chose to work within those boundaries rather than fight them, which is fine.

But it also reveals something important: most AI filmmaking projects right now still need humans for the parts that audiences actually hear and see. The technology isn't replacing people. It's replacing specific tasks like location scouting and set design. Everything that involves performance—voice, movement, expression—still benefits from human input.

Could Runable Help Speed Up This Workflow?

Projects like On This Day... 1776 involve creating dozens of documents, presentations, reports, and visual assets throughout the production process. Storyboards need iteration. Scripts need revision tracking. Production notes need to be compiled into reports. Location reference galleries need to be organized into presentations.

A platform like Runable could automate a lot of that peripheral work. Instead of manually creating presentation decks from production notes, Runable's AI agents could generate slides automatically from script updates. Instead of manually compiling visual reference reports, AI-powered reports could be generated from asset libraries.

At $9/month, the cost is minimal compared to the time savings. For a team juggling AI video generation iterations, having AI-automated documentation and presentation creation would free up human attention for the actual creative direction and iteration cycles.

Production sources said weeks go into getting individual shots right. Some of that time involves communication, documentation, and reporting on progress. Automation there could compress timelines.

Use Case: Automate production reports and presentation decks from AI video generation workflows

Try Runable For Free

Historical Precedent: When New Tools Get Complicated Adoption

Hollywood has a history of dramatically overestimating how fast new technology will transform production and underestimating how long adoption actually takes.

Digital color grading didn't instantly replace traditional color timing, even though it was faster. Cinematographers spent years learning to use digital tools the same way they'd used optical tools, often producing worse results until the learning curve flattened.

Computer animation didn't instantly replace traditional animation. Studios spent the 90s and 2000s learning how to make CG look good. Early CG films look painfully dated now because animators didn't understand how to translate human movement into digital motion until they had experience.

VFX integration into live action took decades to feel seamless. The first attempts were obviously fake. Now they're invisible because people learned the craft.

AI filmmaking is following the same pattern. Early attempts look rough because nobody knows how to use these tools effectively yet. The tools themselves will improve. The people using them will get better. In five years, AI-generated footage will probably be indistinguishable from traditionally shot footage.

But right now? We're in the rough early phase. On This Day... 1776 isn't a failure. It's a process. And it's revealing exactly how much learning and iteration are required before new tools feel natural to use.

What This Means For The Future Of Filmmaking

Aronofsky's experiment matters because it's one of the first times an A-list director committed to using AI filmmaking for a substantial project. And instead of pretending it was easy or revolutionary, the team was honest about how difficult and iterative the process actually is.

That honesty is more valuable than if the early episodes had looked perfect. It sets realistic expectations for what AI filmmaking can do right now and what it will eventually enable as technology improves.

Future projects will probably skip the year-long timeline format (too much public feedback on rough iterations) and will develop better production pipelines for iteration. Studios will hire new types of specialists: people who understand AI models deeply enough to engineer prompts effectively, who can predict what the model will generate, who can troubleshoot when iterations fail.

The craft of filmmaking won't disappear. It'll evolve. The camera will change. The way you compose shots might change. But storytelling, character work, and creative vision are skills that won't be automated. If anything, they'll become more valuable as technical execution gets easier.

What's interesting is watching an A-list director take that leap and showing the real constraints. That's the lesson here. Not "AI replaces filmmakers." But "AI changes what filmmakers have to learn next."

FAQ

What is AI filmmaking?

AI filmmaking uses artificial intelligence video generation models to create visual footage based on text descriptions, storyboards, and visual references. The AI generates video shots that are then edited, color-corrected, and sound-mixed using traditional post-production techniques. It's not a completely automated process—humans still handle writing, voicing, editing, and all creative direction.

Why does AI filmmaking take so long if it's supposed to be faster?

AI video models lack fine-grained control, so creating a single shot often requires dozens of iterations. The team describes what they want, the model generates footage, they review it, modify the prompt, and generate again. This iteration cycle is similar to doing multiple takes in traditional filmmaking, but it requires waiting for AI generation between each attempt. A single minute of finished video can require weeks of iteration work.

How is dialogue handled in AI filmmaking projects?

For On This Day... 1776, human screenwriters wrote all dialogue, professional voice actors recorded it under union contracts, and human editors integrated it with AI-generated footage. The project didn't use AI voice synthesis or text-to-speech systems for the final product, partly due to union requirements and partly because AI voices weren't considered professional-quality.

What parts of AI filmmaking actually use artificial intelligence?

Only the video generation itself uses AI. Everything else—scriptwriting, voice acting, music composition, editing, visual effects, color correction, and sound mixing—is handled by humans using traditional filmmaking techniques. The AI replaces the camera, not the crew.

Will AI filmmaking replace human filmmakers?

No. AI filmmaking is replacing specific technical tasks like location scouting and set design, but it requires human creativity for direction, storytelling, and performance. The technology changes what filmmakers need to learn, but filmmaking as a creative discipline isn't disappearing. It's evolving.

How much does it cost to produce AI-generated footage compared to traditional filmmaking?

Production sources didn't provide specific budget figures, but the time investment suggests costs remain significant. You're not paying for location scouts, equipment rentals, or large crews, but you're paying for specialized AI expertise, iteration cycles, and traditional post-production. The cost advantage isn't clear yet because the technology is so new.

What happened to the critical reception of On This Day... 1776?

The first episodes received harsh criticism for visual quality, repetitive camera movements, and uncanny character rendering. Reviewers complained about the "AI slop" aesthetic. However, production sources indicated the project was designed as a year-long learning experiment where quality would improve as the team and the AI tools both evolved. Later episodes weren't evaluated by early critics, so the ultimate reception remained unclear.

Is AI filmmaking actually new, or did it exist before 2025?

AI video generation became commercially viable and accessible to filmmakers around 2024-2025 with models like Runway Gen-2, Open AI Sora, and Google's Veo. Ancestra, a short film using AI augmentation, released in summer 2025. On This Day... 1776 went further by using AI for primary footage generation rather than just supplemental sequences. It's genuinely new territory.

What did unions do in response to AI filmmaking?

SAG-AFTRA negotiated new contract language protecting voice actors and setting limits on how AI voice synthesis could be used. This influenced projects like On This Day... 1776 to hire union voice actors instead of using AI synthesis. The union played a significant role in shaping how AI filmmaking could actually be produced.

Could Runable's AI automation help streamline AI filmmaking workflows?

Yes, Runable could automate the peripheral documentation, reporting, and presentation work that surrounds the core video generation and iteration process. For a team spending weeks on AI shot iteration, having AI-powered tools to automatically generate production reports, presentations from notes, and visual asset documentation could reduce overhead and free up human attention for creative direction. At $9/month, the ROI would likely be significant for professional production teams.

The Reality Of Creative Evolution With New Tools

What On This Day... 1776 actually proved isn't that AI filmmaking is revolutionary. It proved that using new tools is a gradual process involving lots of failure, iteration, and learning.

The early episodes looked rough. That's not because the concept is bad. It's because Aronofsky's team was in the steep part of the learning curve. They were figuring out how to think about AI video generation the way cinematographers think about camera placement, the way directors think about blocking, the way editors think about pacing.

That learning happens through doing. You make mistakes. You see how audiences react. You adjust. You try again. You get better.

The critics who called it a "disaster" missed the actual story. The story isn't "AI ruins filmmaking." The story is "what does it take to make AI filmmaking work, and how long does the learning curve actually take."

Production sources were honest about this. They said they'd make mistakes. They expected deadlines to slip. They knew the tools would evolve. They understood improvement would be gradual.

That's not the narrative tech companies usually sell you. Usually it's "new technology changes everything overnight." This project said "new technology requires real work, real time, and real learning." That's less exciting. But it's more true.

And honestly? That's when innovations actually matter. When people commit to the messy work of figuring out how new tools actually function in practice, not in marketing demos. When they expect difficulty and plan for iteration. When they're transparent about limitations while remaining optimistic about improvement.

That's Aronofsky's actual contribution here. Not a perfect AI-generated historical series. But proof that a major filmmaker was willing to learn in public, embrace imperfection, and commit to improvement. That matters more than the footage itself.

Key Takeaways

- Each minute of finished AI-generated video takes weeks of production work, not hours, due to extensive iteration and refinement cycles required by current AI models.

- Human creatives—writers, voice actors, editors, composers, and VFX artists—perform the vast majority of work; AI handles only video shot generation.

- Critics misunderstood the project by attributing AI-written dialogue and AI voices to the production, when professional screenwriters and union actors actually created all content.

- Iteration with AI models requires dozens of attempts to achieve desired results, making AI filmmaking comparable in timeline to traditional production methods despite different constraints.

- The technology and creative implementation will improve significantly as teams gain experience and AI models evolve, making early episodes rough but not indicative of final quality.

Related Articles

- Jonathan Nolan on AI in Filmmaking: The Complete Analysis [2025]

- Adobe Animate Lives On: Maintenance Mode Reversal Explained [2025]

- Google's AI Plus Plan Now Available Globally at $7.99/Month [2025]

- Can't Tell Real Videos From AI Fakes? Here's Why Most People Can't [2025]

- Higgsfield's $1.3B Valuation: Inside the AI Video Revolution [2025]

- Google Veo 3.1 Vertical Videos: Reference Images Game-Changer [2025]

![How Darren Aronofsky's AI Docudrama Actually Gets Made [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/how-darren-aronofsky-s-ai-docudrama-actually-gets-made-2025/image-1-1770379574151.jpg)