Windows 11 Hits 1 Billion Users: What This Milestone Means [2025]

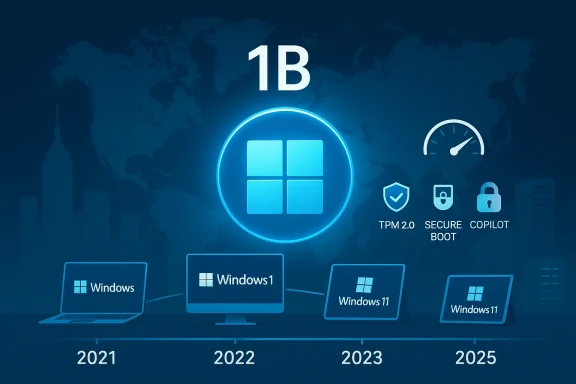

Microsoft's Windows 11 just crossed a threshold that felt inevitable yet somehow still surprising. The operating system now powers over 1 billion devices worldwide—a milestone that arrived roughly 116 days faster than Windows 10 managed to reach the same number. On the surface, this looks like a clean win for Microsoft. Dig deeper though, and you find something messier and way more interesting: a user base that's perpetually frustrated with their OS while simultaneously having nowhere else to go.

That's the real story here. Not the milestone itself, but what it reveals about how operating systems actually work in the real world. Users complain constantly about Windows 11. They hate the mandatory Microsoft account requirements. They despise the notification spam pushing One Drive, Game Pass, and Edge. They're annoyed by features that feel forced rather than helpful. And yet, 1 billion people use it anyway. Why? Because inertia is powerful. Switching costs are real. And honestly, the alternatives still don't make much sense for most people.

This article digs into what the 1 billion user milestone actually means for the Windows ecosystem, why Windows 10 refuses to die despite being officially unsupported, and what Microsoft needs to do next to stop Windows 11 from becoming the "last Windows" users want to use. We'll look at adoption patterns, hardware challenges, security implications, and the fundamental question underlying all of this: what does success look like for a desktop operating system in 2025?

TL; DR

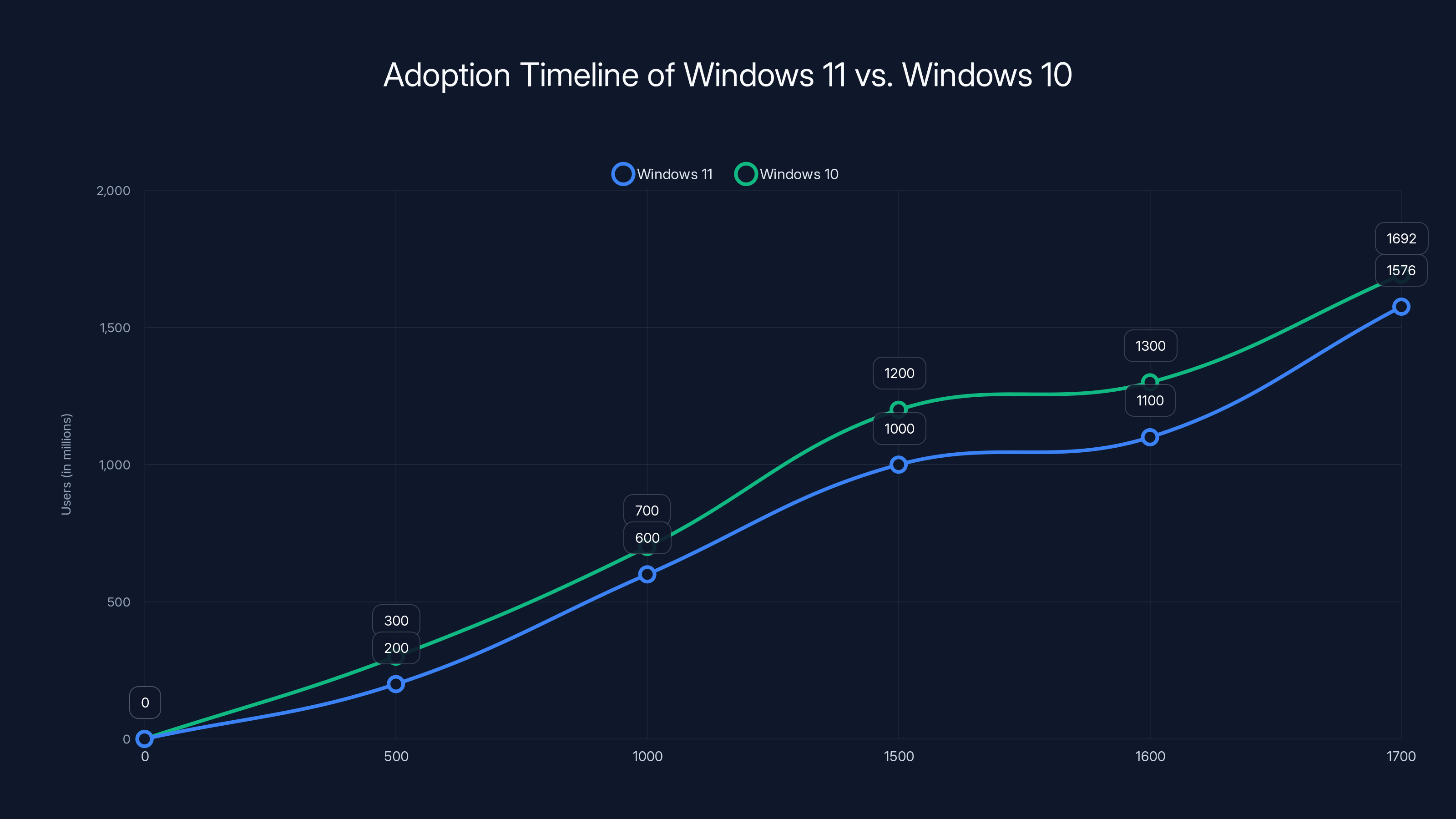

- Windows 11 reached 1 billion users in 1,576 days, roughly 116 days faster than Windows 10 achieved the same milestone

- Windows 10 still powers roughly 400-500 million PCs despite hitting its end-of-support date, creating a massive legacy OS support burden

- Hardware requirements blocked roughly 500 million Windows 10 PCs from upgrading, fragmenting the market in ways that slow both OS adoption and security progress

- User dissatisfaction is real but irrelevant—most people stick with Windows because switching costs exceed frustration costs

- Microsoft's three-year security off-ramp for Windows 10 is a pragmatic necessity but also a security vulnerability that extends legacy OS exposure

Windows 11 reached 1 billion users 116 days faster than Windows 10, despite stricter hardware requirements, indicating a more aggressive adoption curve.

The 1 Billion User Milestone: Context and Speed

When Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella announced that Windows 11 had crossed 1 billion users on the company's latest earnings call, it landed with relatively little fanfare. No press conference. No viral moment. Just a datapoint slipped into quarterly earnings commentary. But the timing matters because it tells us something about how adoption actually works in the real world.

Windows 11 reached 1 billion users in 1,576 days following its October 5, 2021 general availability launch. Windows 10, by comparison, hit the same milestone 1,692 days after its July 29, 2015 release. That's a difference of 116 days—roughly four months faster. On the surface, this seems like a clear win. Faster adoption means broader market penetration, stronger developer interest, and more momentum going into the next cycle.

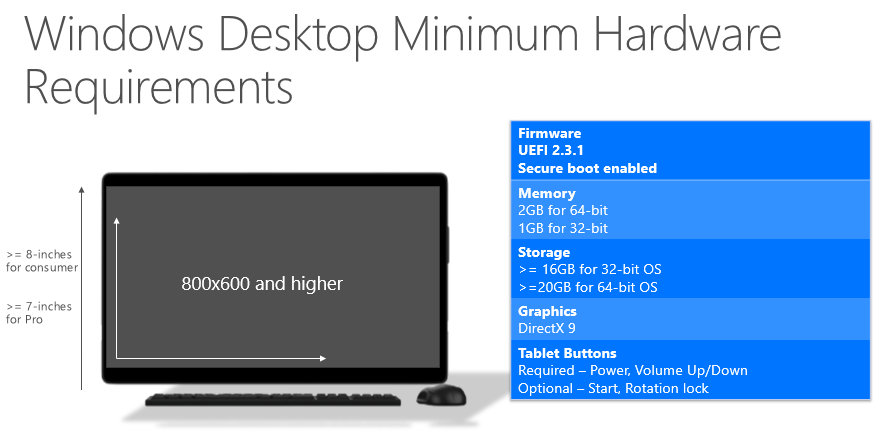

Except the context completely changes that interpretation. Windows 10 was offered as a completely free upgrade to users of Windows 7 and Windows 8. There were no hardware requirements changes. If your PC ran Windows 8 (which almost nobody wanted to run), it could run Windows 10. Adoption was almost frictionless. Windows 11, meanwhile, has genuinely restrictive hardware requirements. You need TPM 2.0. You need UEFI firmware. You need processors from relatively recent generations. These requirements meant that hundreds of millions of Windows 10 PCs couldn't upgrade even if users wanted to.

So Windows 11 achieving 1 billion users faster, despite these barriers, actually represents a more aggressive adoption curve. More people actively chose to upgrade or buy new hardware specifically for Windows 11. That's the real metric hidden in the announcement.

But there's another layer of context that complicates even that reading. This 1 billion number includes devices purchased with Windows 11 pre-installed. It includes people who upgraded deliberately. It also includes people who got a new laptop and had no choice about the OS. The term "users" obscures whether these are active users who use Windows multiple times per week or dormant devices gathering dust. The number tells us market presence. It doesn't tell us user satisfaction or actual engagement.

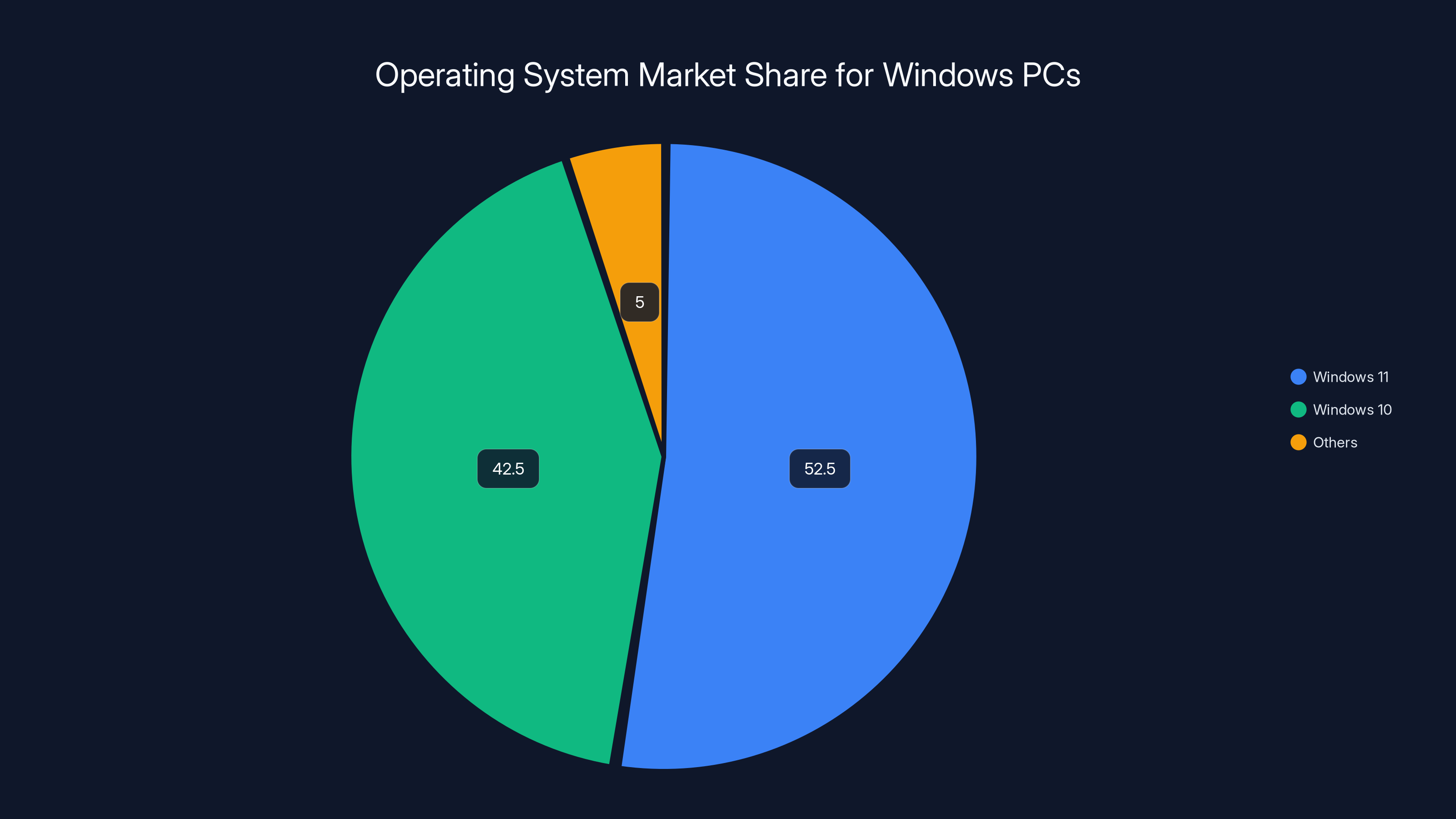

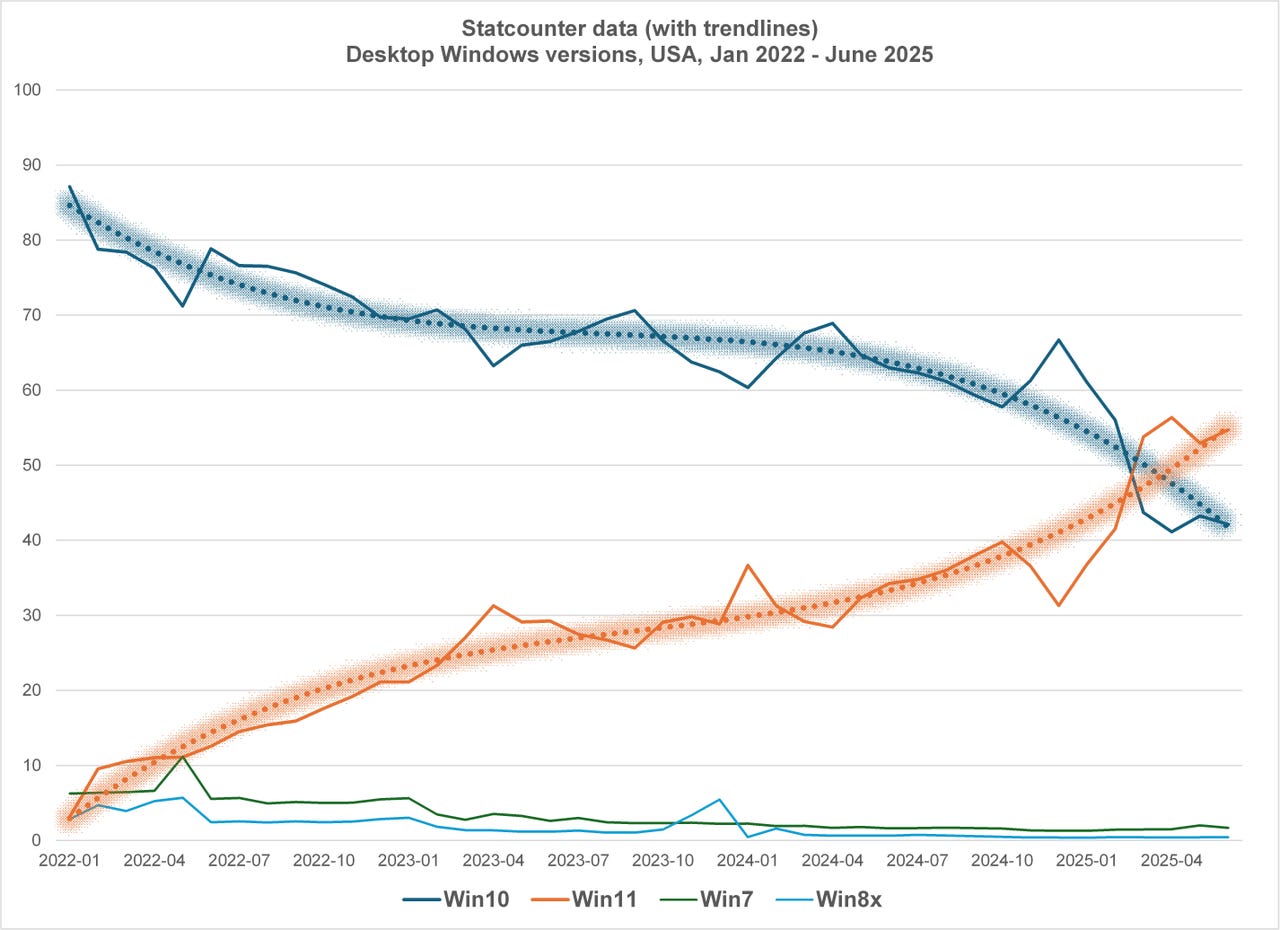

As of late 2025, Windows 11 holds a slight majority with 52.5% of the Windows PC market, while Windows 10 still powers 42.5% of devices. Estimated data reflects trends and market analysis.

Why Windows 10 Still Powers Roughly 500 Million PCs

The 1 billion Windows 11 users milestone makes sense in part because of just how many PCs are stuck on Windows 10. And stuck is the right word—these aren't people choosing Windows 10 after careful consideration. These are people whose hardware won't run Windows 11, combined with a few people who deliberately stayed put.

Dell Chief Operating Officer Jeffrey Clarke stated in late 2025 that approximately 1 billion Windows 10 PCs remain in active use. Of those, roughly 500 million cannot technically upgrade to Windows 11 due to hardware limitations. That's not a small number. That's half a billion devices locked into an unsupported operating system because the upgrade path got blocked.

Why would half a billion PCs not meet Windows 11 requirements? Because Windows 11 requires TPM 2.0, UEFI firmware with Secure Boot, and relatively modern processors. A PC that's five years old—perfectly functional, running modern applications just fine—suddenly becomes a legacy device. A business laptop from 2016 that's been serviced, updated, and kept in excellent working order gets marked as ineligible. This creates a hard cutoff where users don't have a realistic upgrade path that doesn't involve hardware replacement.

For individuals, this means buying a new laptop or desktop just to get an OS they don't particularly want. For businesses, it means coordinating large-scale hardware refreshes. For governments and large institutions, it means budget cycles and procurement processes. So millions of organizations and individuals rationally decided to delay hardware upgrades as long as possible, which means staying on Windows 10.

Statcounter data (one of the most commonly cited sources for OS market share) reports that roughly 50-55% of Windows PCs run Windows 11 and 40-45% run Windows 10. Other sources vary, but the consensus is basically split. Windows 11 is now the plurality, but Windows 10 remains absolutely massive. And Windows 10's support status makes this a security problem that Microsoft can't simply wish away.

The Hardware Requirement Problem and Market Fragmentation

Windows 11's hardware requirements created the most significant market fragmentation the Windows ecosystem has experienced in over a decade. It's not that the requirements are unreasonable—TPM 2.0 and UEFI Secure Boot are legitimate security improvements. The problem is that those improvements created a hard binary: your PC either meets them or it doesn't, with no middle ground and no remediation path.

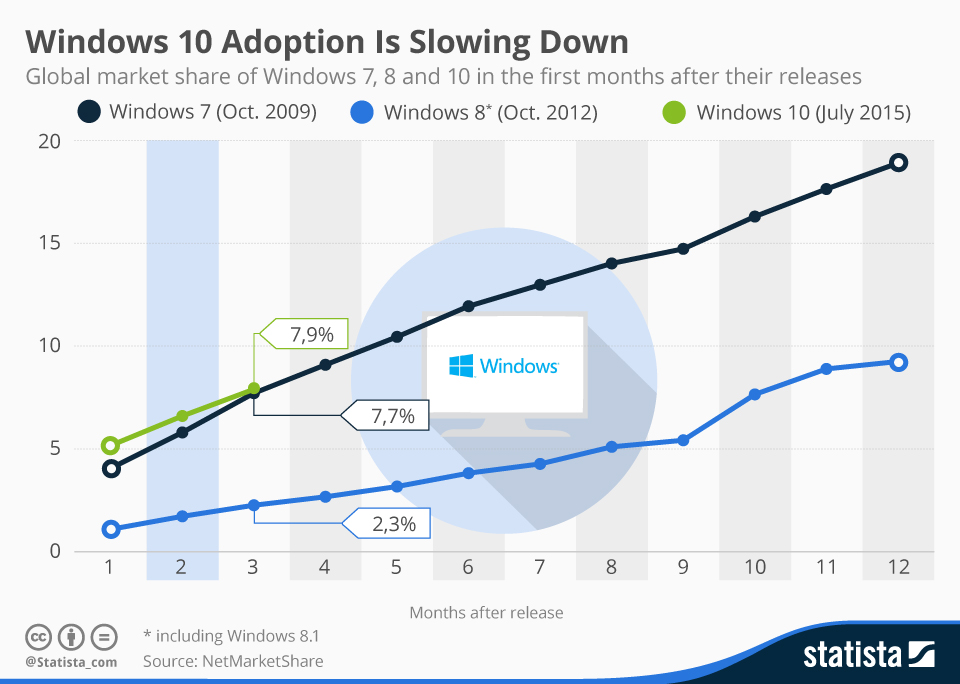

Compare this to the transition from Windows 7 to Windows 8, or Windows 8 to Windows 10. Those transitions were relatively smooth because the hardware requirements barely changed. Your Windows 7 PC could run Windows 10 without modification. You could upgrade the OS without upgrading the hardware. Businesses didn't need to coordinate massive replacement cycles. This meant adoption curves were driven by user choice and OS merit rather than hardware availability.

Windows 11 inverted that dynamic. Now the hardware became the constraint. You could want Windows 11. You could understand why it's better. You could be frustrated with Windows 10. And your three-year-old laptop would tell you "sorry, not compatible." That's not a user problem. That's a system architecture problem.

Why did Microsoft do this? Because TPM 2.0 and Secure Boot actually matter for security. The Windows ecosystem had gotten bloated with legacy cruft and compatibility hacks accumulated over two decades. Windows 10 machines were vulnerable to firmware-level attacks and boot-level compromises that newer security architectures could prevent. Microsoft wanted to fix this not through software patches but through hardware requirements.

That's a reasonable security decision. But it came with a market cost. It fragmented the user base. It created two supported Windows versions instead of one, extending the tail of legacy OS support. And it meant that security improvements became locked behind hardware purchases rather than OS updates.

The result: businesses with large Windows 10 device fleets suddenly faced difficult ROI calculations. Replacing working hardware cost money. Security improvements didn't seem urgent when Windows 10 still got critical patches. Migration delays happened. And here we are in 2025 with half a billion Windows 10 machines still in use.

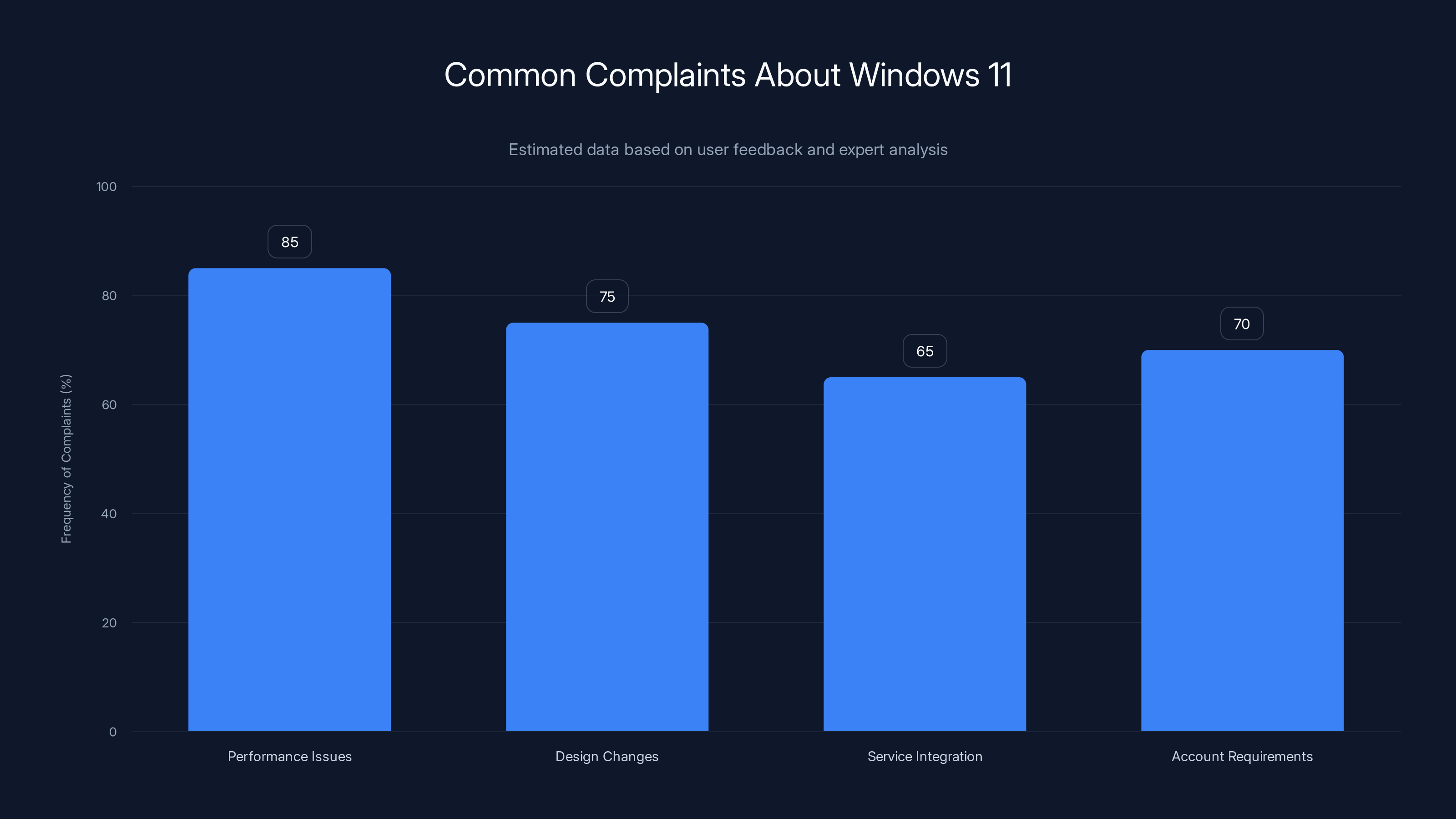

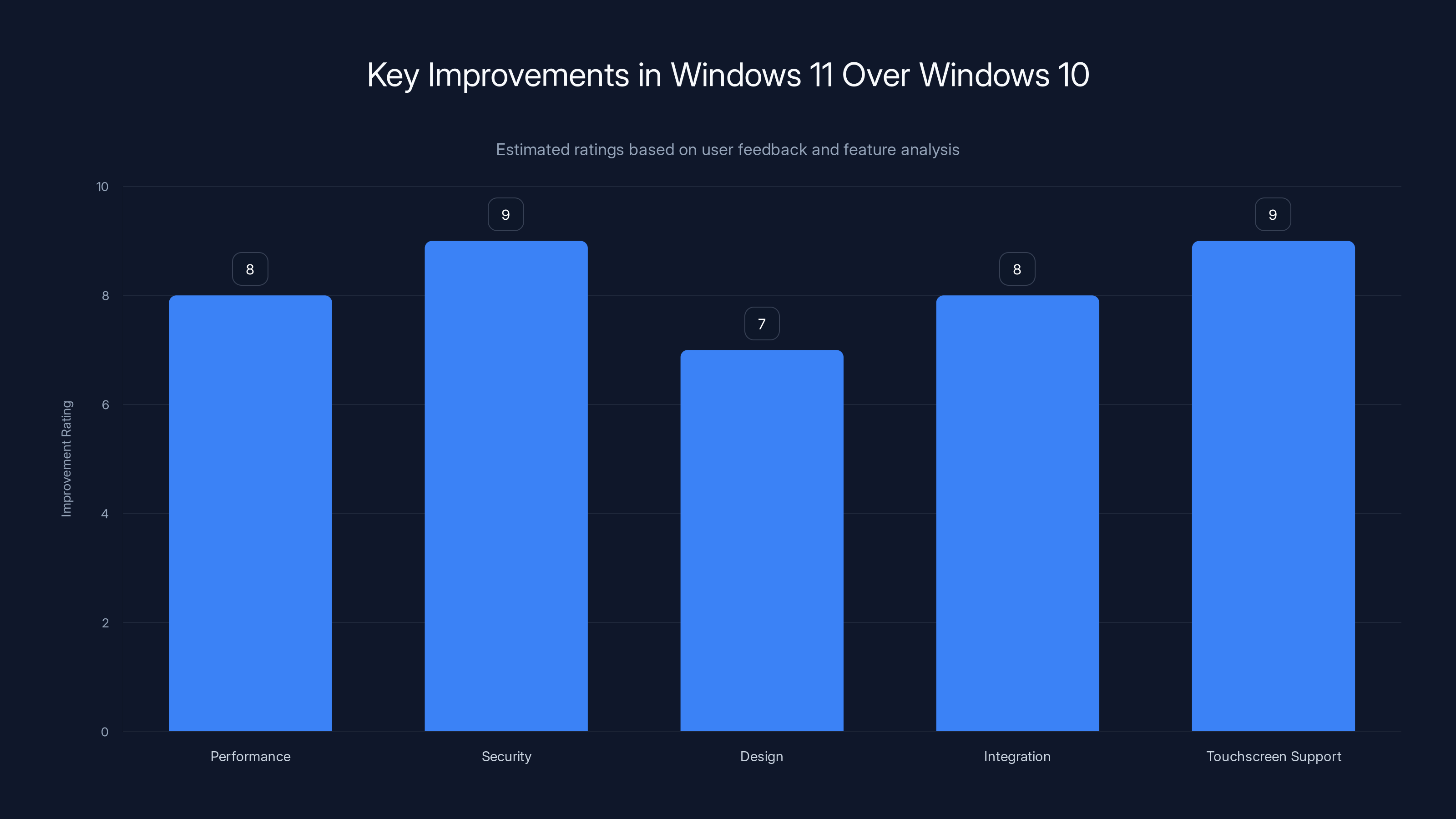

Performance issues are the most frequently reported complaints about Windows 11, followed by design changes and service integration. (Estimated data)

Windows 10's Three-Year Security Off-Ramp

Microsoft can't simply force a migration at knife-point. The company learned that lesson decades ago. So instead, Microsoft created a structured deprecation path for Windows 10 that's pragmatic but also revealing of just how complicated OS support becomes when you have hundreds of millions of legacy devices.

For consumer users, Windows 10 gets one year of free security updates after its official October 2025 end-of-support date. That brings us to October 2026. After that, you're on your own. Microsoft will still push updates to Windows Defender and Microsoft Edge (consumer support extends through 2028), but the operating system itself no longer gets security patches.

For businesses and large institutions, the timeline is longer. Microsoft offers paid security updates for Windows 10 through at least 2028—three full years past consumer end-of-support. This costs money, but it gives organizations time to plan migrations, coordinate hardware refreshes, and test compatibility without abandoning support entirely.

This dual timeline is fascinating because it reveals Microsoft's actual priority structure. Consumers get a year. Businesses that can afford to pay get three years. Everyone else faces the choice: spend money on new hardware, spend money on paid support, or run an unsupported OS. And unsupported doesn't mean unsafe immediately—Windows 10 is relatively mature at this point, with most major security issues already patched. But it does mean no new security patches for zero-day vulnerabilities, which gradually increases risk over time.

The real security implication here is that Microsoft has essentially committed to supporting two Windows versions simultaneously until 2028. That's not just a support burden. It's a development burden. Security researchers need to test exploits against both Windows 10 and Windows 11. Patch Tuesday applies to both. Firmware updates and microcode patches need to account for both. The ecosystem bifurcation creates complexity that extends well beyond just OS development.

The Windows 11 Reputation Problem That Actually Matters

When you ask people about Windows 11, you often hear complaints. Lots of them. The OS gets criticized for feeling bloated, for pushing Microsoft services too aggressively, for forced cloud account requirements that feel invasive, and for including design changes that simply annoyed people rather than improving functionality.

These aren't hypothetical complaints. They're real frustrations that actual users experience. And Microsoft knows about them. The company's leadership has explicitly acknowledged them in recent statements. Pavan Davuluri, Microsoft's president of Windows and devices, said the company would be "swarming" engineers over the next few months to "urgently fix Windows 11's performance and reliability issues."

That statement matters because it's an implicit acknowledgment that Windows 11 has a reputation problem serious enough to warrant explicit executive-level attention. When a company's president has to promise to fix an OS that's already been out for years, that's signal that something went wrong with either the OS design, the feature rollout, or the communication around changes.

The actual problems fall into a few categories. First, there are legitimate technical issues. Windows 11 has had performance problems on some hardware configurations. The background activity can feel excessive. Memory usage sometimes seems bloated. These are engineering problems that can be fixed with better optimization, more careful resource management, and more selective background processes.

Second, there are design problems. The new taskbar felt like a step backward to many users. The Settings interface is still transitioning away from the legacy Control Panel, creating a split where some settings exist in new locations and others exist in old locations. Right-clicking on elements sometimes requires clicking through extra menus. These are UI/UX issues that frustrate people because they work against user expectations shaped by decades of Windows experience.

Third, and most frustrating to users, are the aggressive Microsoft service promotions. Every time you click on something, Windows 11 seems to offer you an upgrade to Game Pass or a reminder about One Drive benefits. The notifications get dismissed but return. The prompts feel persistent. The combination creates a sense that Microsoft is trying to manipulate user behavior rather than simply provide an operating system. Even when these features are genuinely useful, the aggressive marketing undoes that utility.

But here's the critical thing: none of these problems have prevented adoption. Windows 11 is still the majority Windows version. It crossed 1 billion users. People are still upgrading, still buying new machines with it, still using it every day. The reputation problem hasn't created a mass exodus because there's nowhere to exit to. Mac OS requires buying Apple hardware at premium prices. Linux still requires technical knowledge that most users don't have. Chrome OS works if you've fully bought into the Google ecosystem. And for most people in most situations, Windows 11 is frustrating but functional—and switching costs are higher than staying costs.

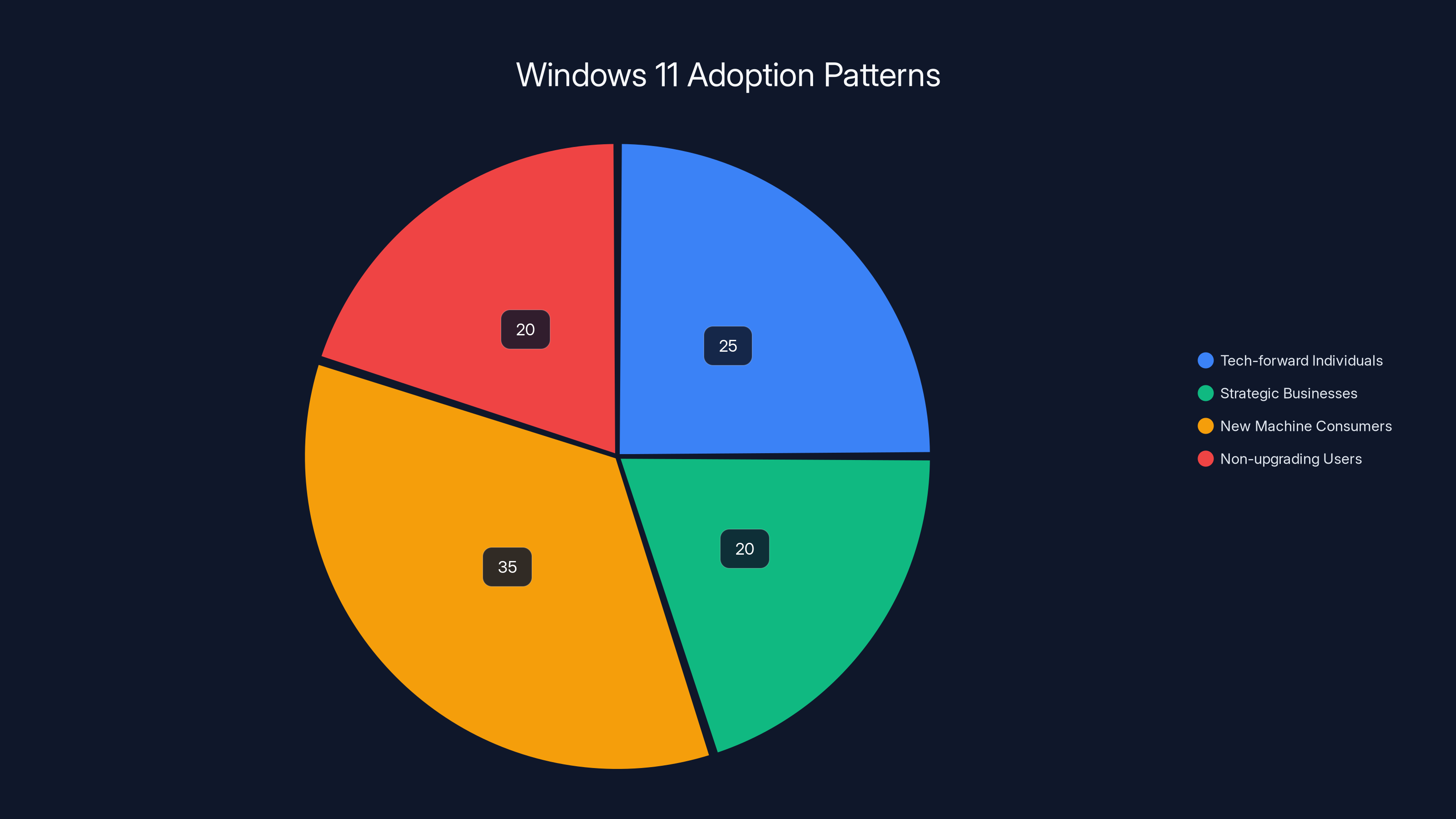

Estimated data shows that new machine consumers account for the largest portion of Windows 11 adoption, driven by new purchases rather than active choice.

Adoption Patterns: Who's Actually Upgrading to Windows 11

The 1 billion user number obscures something important: adoption isn't uniform. Different populations have upgraded at different rates, for different reasons, with different levels of enthusiasm. Understanding these patterns reveals a lot about how operating systems spread through the real world.

Tech-forward individuals and early adopters upgraded relatively quickly. These are people who read tech blogs, who understand that TPM 2.0 is security-relevant, who wanted the new features and were willing to deal with whatever quirks showed up. For this population, upgrading felt like progress. Windows 11 had enough genuine improvements to justify the change, even if the execution wasn't perfect.

Businesses with adequate IT budgets upgraded strategically. They tested Windows 11 in staging environments, developed compatibility matrices, coordinated hardware refreshes, and moved gradually. These organizations treat OS upgrades as IT projects with dependencies and risks, not casual consumer choices. They moved to Windows 11 when they had capacity and when the security benefits justified the migration work.

Consumers who bought new machines got Windows 11 whether they wanted it or not. PC manufacturers stopped selling Windows 10 machines once Windows 11 was available. If you needed a new laptop, you were getting Windows 11. This passive adoption—buying a new machine and accepting the OS that comes with it—probably accounts for a significant portion of the 1 billion number. These aren't necessarily enthusiastic Windows 11 users. They're people who got Windows 11 as a side effect of other purchasing decisions.

Businesses and individuals with systems that couldn't upgrade stayed on Windows 10. This group felt the frustration most acutely. They had functional machines. They didn't want to replace hardware. But staying on Windows 10 meant accepting that their device would eventually become unsupported. Some stayed anyway out of stubbornness. Others used the extended support period to plan gradual refreshes. And some eventually upgraded specifically because support deadlines forced action.

Geographic adoption varies significantly too. In developed markets with robust PC replacement cycles, Windows 11 adoption was faster. In developing markets where PC lifespans are longer and replacement cycles slower, Windows 10 adoption remains much higher. This reflects economic reality—newer hardware costs money, and different markets have different economic capacities.

Industry vertical matters as well. Creative industries that rely on specific software sometimes stayed on Windows 10 if compatibility problems with Windows 11 seemed risky. Financial services, where stability trumps newness, upgraded more slowly. Tech companies themselves upgraded quickly, recognizing the security improvements as essential. The diversity of adoption patterns reveals that "1 billion users" is really millions of different choices influenced by budget, risk tolerance, technical requirements, and economic capacity.

What Windows 11 Got Right (And Why People Still Use It)

For all the criticism, Windows 11 does represent genuine improvements over Windows 10. Understanding these improvements is essential context for why adoption continues despite frustration.

Second-by-second performance can be noticeably faster on newer hardware. The OS initialization is quicker. Application launching feels snappier. File operations are more responsive. Some of this is down to better OS optimization. Some of it is down to the fact that Windows 11 requires newer hardware, which is inherently faster. But the net result is that Windows 11 feels responsive in ways Windows 10 sometimes doesn't, especially after the OS has been running for months.

The security architecture is genuinely stronger. Secure Boot requirements mean firmware-level integrity checking. TPM 2.0 provides hardware-based security that Windows 10 couldn't guarantee. Windows Sandbox, Hyper-V integration, and containerization features provide isolation that makes malware execution harder. These aren't flashy features that users notice directly, but they fundamentally reduce attack surface in ways that matter.

The new design language feels more modern. The rounded corners, the softer edges, the lighter aesthetic—these aren't revolutionary changes. But they create a sense of progression. The OS feels updated in ways that go beyond mere functionality. For users who spend eight hours daily in their OS, that aesthetic refresh matters more than outsiders often acknowledge.

Integration with Microsoft services is tighter, which is great if you use Microsoft products. Teams integration works better. One Drive sync is more seamless. Microsoft 365 applications feel more native to the OS. If you're already invested in the Microsoft ecosystem (and most enterprise users are), Windows 11 provides better integration than Windows 10 managed.

Touchscreen and hybrid device support is genuinely improved. Windows 11 was designed with tablets and 2-in-1 devices in mind from the start, whereas Windows 10 tacked tablet support on as an afterthought. If you're using a touch-enabled device, Windows 11 feels significantly more refined.

These improvements exist. They're real. They're valuable. They're why people who upgrade often appreciate Windows 11, even if they also complain about the notification spam and the mandatory Microsoft accounts. The OS fundamentally works better than its predecessor in most objective measures. The frustration people express isn't about broken core functionality. It's about surface-level stuff that feels unnecessary and frustrating even when the underlying system performs well.

Windows 11 shows significant improvements in security and touchscreen support, with high ratings in performance and integration. Estimated data based on feature analysis.

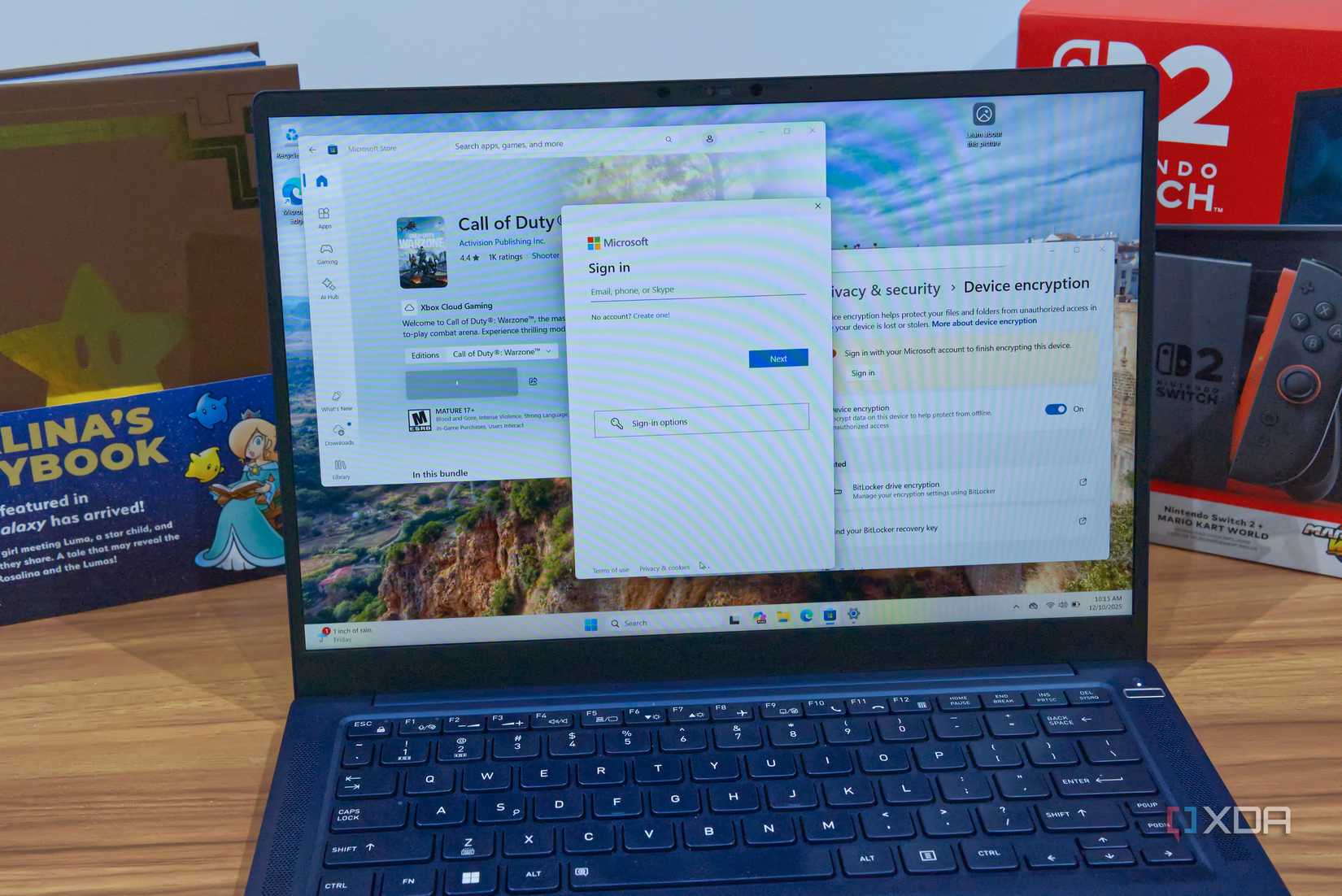

The Notification and Service-Pushing Problem

One of the most frequent complaints about Windows 11 can be summarized simply: the OS constantly tries to sell you stuff. One Drive offers show up. Game Pass advertisements appear. Microsoft Edge suggestions pop up. Microsoft account sign-in requirements feel mandatory rather than optional. For a product you already paid for (either through PC purchase or as part of enterprise licensing), this constant promotional activity feels inappropriate.

This isn't new to Windows 11. Windows 10 did similar things. But Windows 11 feels more aggressive, more persistent, and more difficult to disable. The notifications return even after dismissal. The prompts reappear in new contexts. And because Microsoft owns both the OS and these services, the company has leverage to promote them in ways independent software makers can't.

The problem with this approach is that it undermines trust. Users understand that Microsoft wants to make money. Users accept that integrated services are part of the value proposition. But the combination of being unable to opt out cleanly and seeing persistent re-prompts after dismissal creates a sense of manipulation. It feels like Microsoft doesn't respect the user's stated preference to not use these services.

For enterprise users, this is a different but related problem. Organizations maintain standardized desktop images with specific service configurations. When Windows 11 pushes updates that reset or re-enable these notifications, it creates management overhead. IT teams have to spend time re-applying configurations that users have already dismissed. It turns OS updates from maintenance events into management tasks.

Microsoft likely views this differently. From the company's perspective, One Drive is genuinely useful—cloud storage prevents data loss and enables device synchronization. Game Pass is a legitimate value-add for gaming-inclined users. Microsoft Edge has legitimate advantages over older browsers. The company probably sees recommendations as helpful rather than manipulative.

But user experience is subjective. A service you want to be reminded about is helpful. A service you don't want gets repeatedly forced back in front of you feels aggressive. And when dismissing a notification requires multiple steps or returns in different contexts, that transforms helpful recommendation into annoying nag.

This is one area where Microsoft's statement about "swarming" engineers to fix Windows 11's problems might actually help. Toning down the notification aggression, making dismissals more permanent, and respecting explicit user preference to not use certain services could significantly improve user sentiment without changing any actual functionality.

Security Implications of Massive Legacy OS Support

The fact that 500 million Windows 10 machines will remain in use through 2028 (for paid users) creates security challenges that ripple through the entire ecosystem. This isn't just a Windows problem—it's an industry problem that affects endpoint security, enterprise network architecture, and risk management.

When you need to support multiple OS versions simultaneously, security complexity increases nonlinearly. Each vulnerability requires patches for each supported version. Testing becomes more elaborate. Workarounds may be needed if a fix in one version breaks compatibility in another. Security teams have to maintain expertise across multiple OS architectures and security models.

More concerningly, the longer tail of legacy OS support extends the window of vulnerability. Windows 11 can implement security features (like Secure Boot enforcement or TPM integration) that Windows 10 can't rely on. This means security patches sometimes need to account for lower security guarantees on Windows 10 systems. Advanced exploit techniques that would be blocked on Windows 11 might work on Windows 10, extending vulnerability windows and increasing attack surface.

For businesses, this creates difficult risk management scenarios. A Windows 10 system that you intended to migrate away from but haven't yet upgraded becomes a potential security weakness in your network. It's not terrible—Windows 10 is stable and mature, with most obvious vulnerabilities already patched. But zero-days and newly discovered exploits could exist for that system for years while Windows 11 gets protected with new mitigations.

Microsoft's solution of paying for extended support addresses this partially. Organizations can allocate budget for longer support periods. But it's a budget item that might not survive cost-cutting measures. And payment doesn't change the underlying fact that Windows 10 lacks Windows 11's security architecture—it just extends patch availability.

The real security lesson here is that legacy OS support creates costs that persist long after the new version launches. And when you have 500 million devices stuck on legacy OS because of hardware requirements, those costs become substantial. Microsoft took a security-first approach with Windows 11's hardware requirements. The tradeoff was that supporting both versions simultaneously became necessary, which actually increases complexity and extends overall security risk.

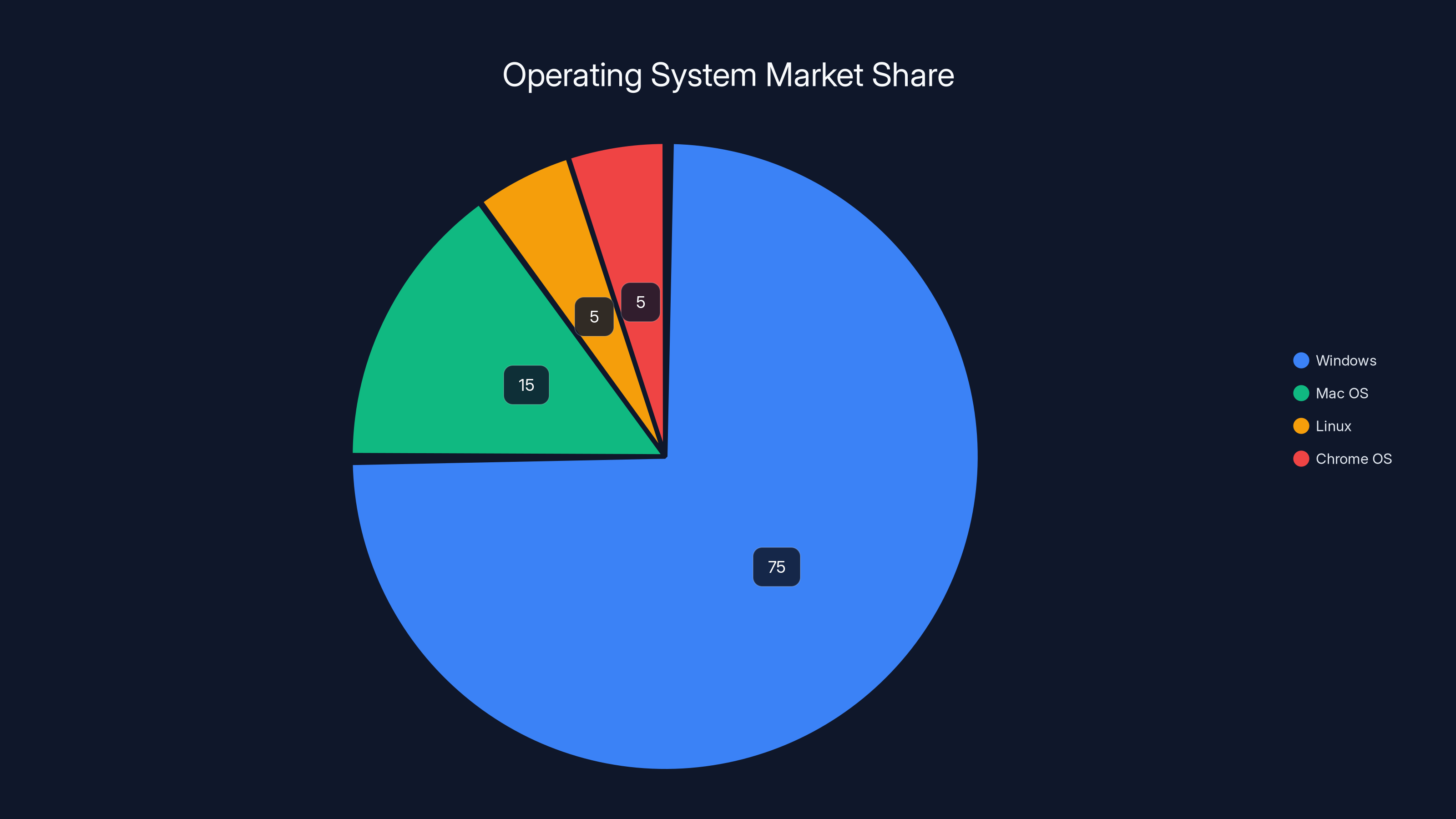

Windows holds a dominant market share at 75% due to its affordability and capability, while Mac OS, Linux, and Chrome OS remain niche due to cost, complexity, and limitations respectively. Estimated data.

Windows Activation and Licensing Complexity

One often-overlooked aspect of the Windows 10 to Windows 11 transition is the licensing and activation complexity that emerged. The terms under which users could upgrade, whether their license transferred, and what new requirements existed created genuine confusion.

For consumer users, the distinction was relatively simple: Windows 11 was a free upgrade for Windows 10 users. But activation requirements changed. Microsoft shifted toward requiring a Microsoft account for many Windows 11 installations, particularly for home users. This felt like a regression to people who had successfully used Windows 10 with local accounts and minimal Microsoft integration.

For enterprise users, licensing becomes more complex. Windows 10 machines that couldn't upgrade to Windows 11 because of hardware constraints still need to be licensed. Organizations can't simply let unsupported machines run without licensing. Extended support requires paid agreements. Hardware refresh requirements create capital expense. These aren't trivial costs for large organizations with tens of thousands of machines.

Small businesses face a particular challenge. They don't have the scale or IT sophistication of large enterprises, so negotiating extended support isn't practical. But they also don't have the flexibility of consumer users who can simply buy a new machine when Windows 10 goes fully unsupported. They're stuck in an awkward middle ground where Windows 10 support ends but migration costs are still substantial.

This licensing complexity is partly why Windows 10 adoption remains so high. The financial and administrative burden of upgrading is substantial enough that organizations find ways to delay or defer migration. And as long as some vendor support remains available, the incentive to migrate decreases.

The Market Competitive Context

Windows 11's 1 billion user achievement looks impressive in isolation. But understanding it requires context about what alternatives users actually have and why those alternatives remain niche.

Mac OS runs on Apple hardware at premium price points. A comparable Mac Book costs significantly more than a comparable Windows laptop. For price-conscious consumers and budget-constrained organizations, Mac OS isn't a realistic alternative. Even if you preferred Mac OS, the hardware economics make it unaffordable for most of the market. Apple has chosen to optimize for premium positioning rather than market share, which means the vast majority of computer users will never seriously consider switching.

Linux is free and powerful but requires significantly more technical knowledge than Mac OS or Windows. You need to understand command lines, package management, driver configuration, and system administration. The barrier to entry is much lower than it was twenty years ago, but it's still substantially higher than point-and-click consumer operating systems. For professionals who value technical control, Linux makes sense. For casual users and non-technical workers, the learning curve is prohibitive.

Chrome OS works well if you spend your time in web browsers and Google services. But it provides limited local application support and depends on cloud connectivity. If you need to run specialized software—whether that's industry-specific applications, professional tools, or demanding games—Chrome OS won't meet your needs. It's suitable for specific use cases, not general-purpose computing.

This competitive context explains why Windows dominates despite user frustration. The alternatives are either too expensive (Mac OS), too difficult to use (Linux), or too limited in capability (Chrome OS). Windows sits in the sweet spot of being affordable, capable, and relatively accessible. You don't have to love Windows 11 to understand why 1 billion people use it. You just have to recognize that the alternatives are worse in ways that matter to most people.

The market share is self-reinforcing too. Because Windows dominates, software developers optimize for Windows first. Specialized industry applications often exist only on Windows. Office productivity software is designed with Windows in mind. Gaming is optimized for Windows. This software inertia means that even if you disliked Windows, switching would require finding or rewriting software for your chosen alternative. For most people, that tradeoff isn't worth making.

Enterprise Deployment Strategies and Windows 11 Adoption

Enterprise adoption of Windows 11 follows patterns quite different from consumer adoption. Large organizations approach OS upgrades as capital projects with dependencies, risk assessment, and phased rollout strategies.

Most enterprises start Windows 11 evaluation during Windows 10's stable phase. They deploy test systems, verify application compatibility, assess hardware requirements, and develop upgrade strategies. This process typically takes six to twelve months. Only after comprehensive testing do organizations begin staged rollouts to production environments.

Hardware requirements complicate enterprise deployment significantly. Many organizations have three to five year old machines that work perfectly fine but don't meet Windows 11 specifications. This creates an equipment refresh timeline that's driven by OS requirements rather than hardware failure. Organizations need to budget for replacement hardware while still supporting existing Windows 10 systems. This cost structure makes migration timelines longer than consumer adoption.

Application compatibility is the other major complication. Enterprises often run legacy applications that have limited Windows 11 support. Some applications were written fifteen years ago for Windows XP and have been updated minimally since. Ensuring these applications run on Windows 11 sometimes requires compatibility modes, virtual machines, or significant rework. The cost of ensuring application compatibility can be substantial enough to delay enterprise migration by multiple years.

User training represents another deployment challenge. Windows 11's interface differences from Windows 10 require help desk preparation and user support. Even minor UI changes create support tickets from users who can't find features they expect. Large organizations often develop internal documentation and training materials before deploying new OS versions to minimize support overhead.

By the end of 2025, most large enterprises had completed Windows 11 deployment or had clear timelines for completion. But many mid-market and smaller businesses were still running mixed environments with Windows 10 and Windows 11. The economic realities of capital equipment refresh meant that consolidation was happening gradually rather than all at once.

Looking Ahead: What Microsoft Needs to Fix

Microsoft's acknowledgment that Windows 11 needs urgent fixes reveals executive awareness that the OS hasn't fully won over users despite market dominance. The 1 billion user milestone is real, but so is the persistent complaints. What does fixing Windows 11 actually require?

First, address the performance and reliability issues explicitly. Windows 11 can feel sluggish on systems with limited resources. Background processes sometimes spike CPU usage unexpectedly. Memory usage creeps up over time. These aren't catastrophic problems, but they create persistent friction. Serious optimization work could make Windows 11 feel noticeably faster and more responsive, particularly on lower-end hardware.

Second, genuinely fix the notification and service-promotion problem. Make dismissals stick. Stop re-prompting users about services they've explicitly declined. Respect user preference as default rather than treating user preferences as obstacles to overcome. This seems simple, but it requires changes throughout the OS and service integration architecture.

Third, modernize the remaining legacy OS components. Windows 11 still includes decades-old code for networking, display drivers, and system configuration. Some of this legacy code can be rewritten or replaced. Some of it requires careful compatibility work to ensure nothing breaks. But the accumulated cruft creates both security risk and operational complexity that impacts performance.

Fourth, address the mandatory Microsoft account requirements for consumer users. Provide a genuine choice between Microsoft account authentication and local account authentication. This might require different feature sets or support levels, but forcing cloud account authentication on users who don't want it creates friction.

Fifth, improve the upgrade experience for Windows 10 users. Make clear what will and won't work on their systems. Provide straightforward hardware requirement assessment. If a PC can't upgrade, explain why clearly and provide upgrade paths that make sense economically. Right now, the experience is frustratingly opaque, and many users don't understand why their machines can't upgrade until they try.

These aren't revolutionary changes. They're incremental improvements that address the most persistent user frustrations. And they're feasible within normal development cycles. The question is whether Microsoft will actually prioritize these improvements or whether the company will treat the 1 billion user milestone as validation that everything is fine.

The business math matters here. If Windows 11 reaches 1.5 billion users and adoption is still considered successful, Microsoft has limited incentive to make substantial changes. But if user satisfaction matters—if Microsoft cares about maintaining trust and preventing the OS from becoming something users actively avoid—then these fixes become essential.

The Windows Ecosystem in 2026 and Beyond

The 1 billion user milestone marks a checkpoint in Windows 11's adoption trajectory. The OS is now the clear dominant version, and market momentum will likely continue pushing adoption forward. But the presence of hundreds of millions of Windows 10 machines creates a long tail of support obligations that will extend well past 2028.

What does this mean for the future? Windows 11 will almost certainly continue as the standard for at least another five to seven years. Microsoft has committed to supporting it through the early 2030s based on standard Windows lifecycle. The next major version—Windows 12, or whatever it's called—is still years away. When it does arrive, it will probably face similar hardware requirement challenges as Windows 11 did, creating a new round of incompatibility and migration delays.

The fundamental architecture decisions Microsoft made with Windows 11—the TPM requirements, the Secure Boot enforcement, the security-first approach—will probably persist. These were good decisions from a security standpoint. But they came with market costs that took years to fully materialize. Microsoft likely learned that lesson and will need to balance security improvements with migration accessibility when designing the next version.

The bigger question is whether the Windows desktop ecosystem will remain relevant five years from now in the same way. Cloud computing, web applications, and remote computing are shifting user behavior. The traditional desktop OS matters less as workloads move to cloud infrastructure. Chromebooks and web-based tools are becoming more capable. This long-term trend doesn't mean Windows will disappear, but it does suggest that Windows's dominance may gradually decline as platforms fragment and as more computing happens in cloud infrastructure rather than on local machines.

But that's a prediction for the 2030s. Right now, in 2025, Windows 11's 1 billion user achievement is real and represents genuine market presence. Addressing the OS's shortcomings while maintaining momentum seems like the practical priority for Microsoft in the next couple of years.

FAQ

How did Windows 11 reach 1 billion users faster than Windows 10?

Windows 11 reached 1 billion users in 1,576 days compared to Windows 10's 1,692 days—roughly 116 days faster. This happened despite Windows 11 having more restrictive hardware requirements (TPM 2.0, UEFI, newer processors), which created an upgrade barrier that Windows 10 didn't have. The faster adoption reflects more aggressive adoption curves once you account for hardware constraints, partially driven by PC manufacturers discontinuing Windows 10 systems once Windows 11 became available, forcing passive adoption through new hardware sales.

Why can't 500 million Windows 10 machines upgrade to Windows 11?

Windows 11 requires TPM 2.0 (trusted platform module), UEFI firmware with Secure Boot, and relatively recent processor generations. Machines older than roughly four to five years often lack these components, particularly TPM 2.0, which wasn't standard until around 2015-2016. An otherwise perfectly functional three or four-year-old laptop simply cannot upgrade without hardware replacement. This created a hard cutoff where hundreds of millions of devices became ineligible for upgrade despite being capable of running modern software applications.

Is Windows 10 dangerous to use after its end-of-support date?

Windows 10 isn't immediately dangerous after going unsupported, but risk increases over time. The OS is mature with most obvious vulnerabilities already patched. However, new exploits and zero-day vulnerabilities will no longer receive security patches from Microsoft after consumer support ends in October 2026 (extended support for business users continues through 2028 with paid plans). Security researchers will likely continue discovering issues that Windows 10 machines can't patch. Additionally, Microsoft will continue updating Windows Defender and Microsoft Edge through 2028, which helps but doesn't fully mitigate legacy OS risk.

What are the main complaints about Windows 11, and will Microsoft fix them?

Common complaints include aggressive notification spam about One Drive and Game Pass, mandatory Microsoft account requirements, performance issues on some hardware, forced promotions that reappear after dismissal, and UI changes that feel less intuitive than Windows 10. Microsoft has acknowledged these issues and committed to "swarming" engineers to address performance and reliability problems. However, many complaints (like service promotion aggression) are architectural choices reflecting Microsoft's business model—monetizing user attention and service subscriptions. Fixing these might require changes to how Microsoft makes money from Windows, not just engineering improvements.

How does Apple's Mac OS compare to Windows 11?

Mac OS is technically strong and offers excellent integration with Apple's ecosystem. However, Mac hardware costs 30-50% more than equivalent Windows machines, making it unaffordable for budget-conscious consumers and organizations. Mac OS also has a smaller software library and less specialized industry application support than Windows. Additionally, the tight Apple hardware ecosystem limits configuration choices. For many use cases, Windows 11 offers better value despite user frustration, simply because the hardware economics are more favorable for most people.

Should businesses still be using Windows 10 in 2025?

For most organizations, no. Windows 10 support ends in 2026 (consumer) and 2028 (business with paid support). Machines that can't upgrade to Windows 11 should have clear hardware replacement timelines scheduled. Organizations should prioritize upgrading compatible Windows 10 machines to Windows 11 unless specific application compatibility issues prevent migration. For machines stuck on Windows 10 due to hardware constraints, beginning hardware refresh cycles now makes sense. Waiting until 2027 or 2028 to start planning increases rushed migration risk.

What's the difference between Windows 11 Pro and Windows 11 Home?

Windows 11 Home is designed for consumer use and includes core functionality like Windows Hello biometric authentication, Cortana, and basic security features. Windows 11 Pro adds domain join capability (essential for enterprise networking), Group Policy editor access, Hyper-V virtualization support, and remote desktop connection functionality. Professional users and organizations almost always use Pro or Enterprise versions. The Home version is adequate for consumer computing but lacks tools that enterprise and technical users need. Pricing difference between Home and Pro varies by region but is typically 60-80 USD in the US market.

Can you install Windows 11 on unsupported hardware?

Technically yes, though Microsoft doesn't recommend it and makes the installation process deliberately more difficult. You can bypass TPM and processor requirements using registry edits or workarounds. However, doing so voids official support and Microsoft warns that such installations may not receive updates or may have stability issues. Some users have successfully run Windows 11 on older hardware using workarounds, but this approach isn't recommended for production systems. If your hardware doesn't meet requirements, upgrading to compatible hardware is the supported solution, despite the cost burden it creates.

How often does Microsoft release Windows updates?

Windows 11 receives security updates on a monthly basis (Patch Tuesday), typically the second Tuesday of each month. Major feature updates happen roughly twice per year, typically in spring and fall (versions are named by year and number, like 23H2 for the second release of 2023). Between major updates, quality updates and security patches come regularly. This update cadence is consistent across consumer and business versions, though businesses can defer feature updates longer than consumers if needed through Group Policy configuration.

Is Windows 11 more secure than Windows 10?

Yes, Windows 11 has a stronger security architecture by design. The OS enforces Secure Boot requirements, integrates TPM 2.0 for hardware-based security, and includes enhanced virtualization features that create stronger isolation between applications and system components. These architectural improvements reduce attack surface for firmware-level exploits and rootkit-style attacks that Windows 10 can't defend against as effectively. That said, Windows 10 with security patches and Windows Defender is still reasonably secure for typical users. The advantage goes to Windows 11 for advanced threats and zero-day exploits, but day-to-day security for normal users is adequate on both versions.

Final Thoughts on the 1 Billion User Milestone

Windows 11 reaching 1 billion users is real. The market dominance is genuine. The OS works. Most people who use it get their work done, play their games, and live their digital lives without catastrophic problems. But the persistence of Windows 10, the aggressive service promotion, the notification spam, and the hardware requirement barriers reveal something important about how operating systems actually work in the real world: success isn't about making everyone happy. It's about being marginally better than alternatives and difficult enough to replace that people stick with you even when frustrated.

That's not a ringing endorsement. It's an acknowledgment of how inertia, switching costs, and ecosystem effects shape real-world technology adoption. Microsoft has built something that dominates by default and persists through frustration. That's valuable business, but it's a fragile advantage. If Microsoft lets frustration accumulate too much—if the OS becomes genuinely annoying rather than pleasantly functional—users might finally decide switching costs are worth paying.

The company's recent acknowledgments of Windows 11's shortcomings suggest Microsoft recognizes this risk. Whether the company actually follows through with meaningful fixes remains to be seen. But the 1 billion user milestone matters less than what happens next with that installed base. Will Windows 11 keep users engaged and satisfied? Or will it become the OS people use because they have to, right up until the moment a viable alternative finally emerges?

For now, Windows 11 has won. The market has spoken. A billion people run it every day. But winning the market is different from winning user hearts. Microsoft will eventually need to address that distinction, or risk squandering the dominance it currently enjoys.

Key Takeaways

- Windows 11 reached 1 billion users in 1,576 days, roughly 116 days faster than Windows 10 despite stricter hardware requirements creating genuine upgrade barriers

- Approximately 500 million Windows 10 machines cannot upgrade to Windows 11 due to lacking TPM 2.0 and UEFI requirements, fragmenting the OS market and extending legacy support obligations

- User dissatisfaction with Windows 11 is real—aggressive service promotions, mandatory Microsoft accounts, and notification spam drive complaints—but switching costs remain prohibitive compared to frustration costs

- Windows dominates with 70-75% global market share not because it's loved but because alternatives (Mac OS at 20%, Linux under 5%) are too expensive, technically complex, or capability-limited for most users

- Microsoft's three-year security off-ramp for Windows 10 extends support through 2028, creating simultaneous multi-version support complexity that impacts enterprise deployment and security management

Related Articles

- Windows 11 Hits 1 Billion Users: The Surprising Truth Behind the Milestone [2025]

- Windows 11 Hits 1 Billion Users: Why It's Winning Faster Than Windows 10 [2025]

- The Future of Digital Documents: Moving Beyond PDFs With AI [2025]

- Digital Friction Is Crippling UK Productivity: How AI Fixes It [2025]

- AI Glasses & the Metaverse: What Zuckerberg Gets Wrong [2025]

- WinRAR Security Flaw CVE-2025-8088: Complete Defense Guide [2025]

![Windows 11 Hits 1 Billion Users: What This Milestone Means [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/windows-11-hits-1-billion-users-what-this-milestone-means-20/image-1-1769728050385.jpg)