Meta's Fight Against Social Media Addiction Claims in Court [2025]

When Meta walked into courtrooms across America this year, the company brought one central argument: social media addiction isn't real. Not scientifically. Not medically. Not in any way that matters legally.

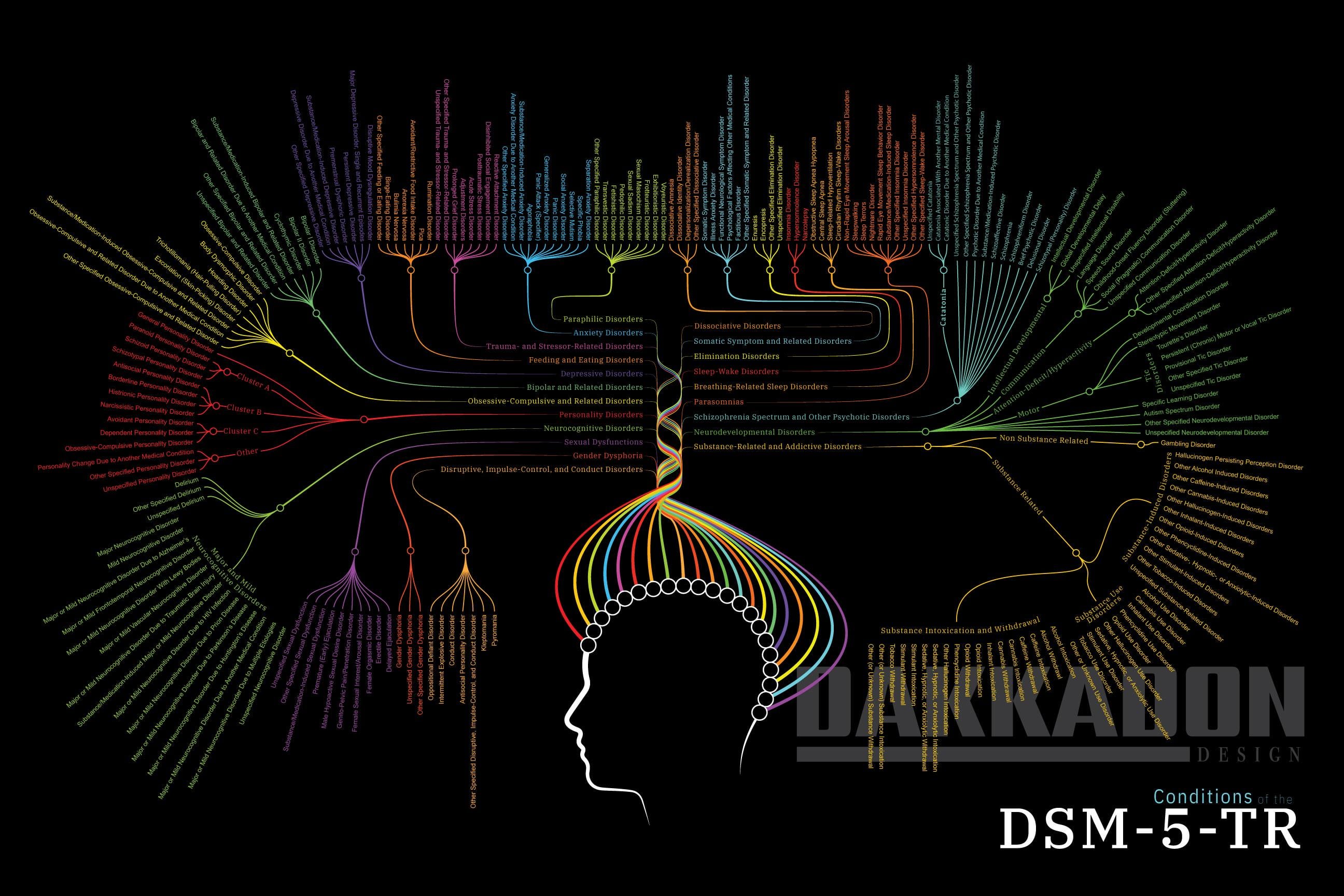

The company's reasoning sounds straightforward enough. Instagram chief Adam Mosseri compared social media dependency to binge-watching Netflix. Meta's lawyers argued that without a formal diagnosis in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, addiction to these platforms simply doesn't exist as a clinical condition.

But here's where the story gets complicated.

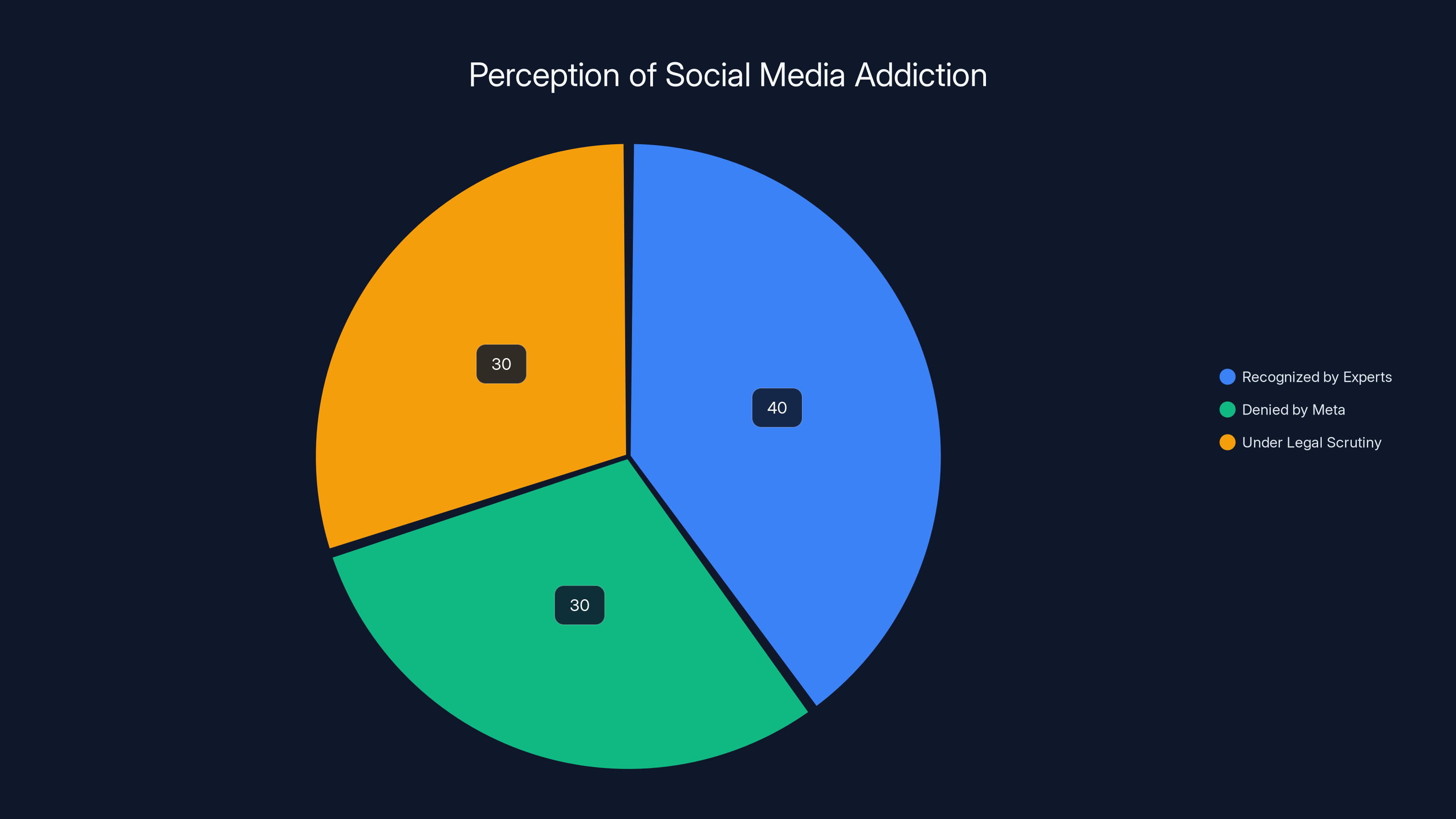

The American Psychiatric Association has explicitly stated that social media addiction doesn't exist as a DSM diagnosis, but that absolutely doesn't mean it's not real. That's a crucial distinction Meta's legal team conflated in courtroom arguments, and it's a distinction with profound implications for how we understand digital dependency, mental health, and corporate responsibility.

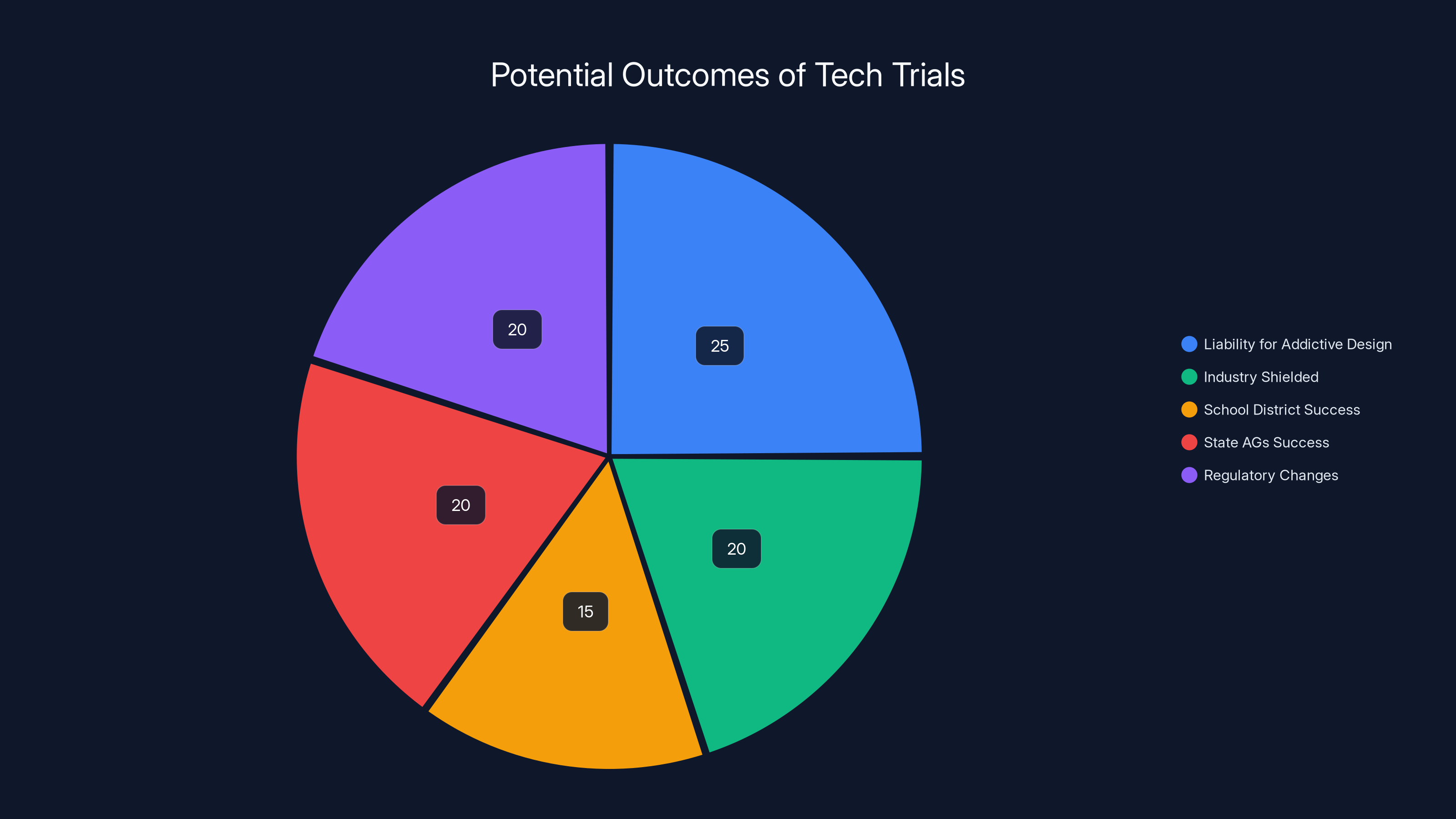

This isn't just a legal technicality playing out in New Mexico and California courtrooms. It touches something fundamental about how technology companies defend their business models, how society defines addiction, and whether platforms have obligations to protect users from their own compulsive use. The trials that kicked off this year represent the first major legal test of whether behavioral addictions—patterns of use that damage people's lives even without a formal DSM listing—can be the basis for corporate liability.

What's at stake isn't just Meta's reputation or these particular lawsuits. It's how we'll define and address behavioral addiction going forward, what evidence will count as proof of harm, and whether platform design choices meant to maximize engagement constitute negligence or manipulation.

TL; DR

- Meta claims social media addiction isn't real because it lacks formal DSM-5 classification, but the American Psychiatric Association disagrees with this interpretation

- Multiple trials are testing whether behavioral addiction patterns can form the basis for corporate liability, with cases in New Mexico, Los Angeles, and from school districts

- Scientific evidence shows social media can trigger dopamine responses, reward system changes, and documented mental health impacts similar to behavioral addictions

- The DSM absence doesn't mean social media addiction doesn't exist—many conditions are studied and treated before receiving official diagnostic status

- This legal battle will reshape how tech companies can be held accountable for addictive design features and their impact on young users

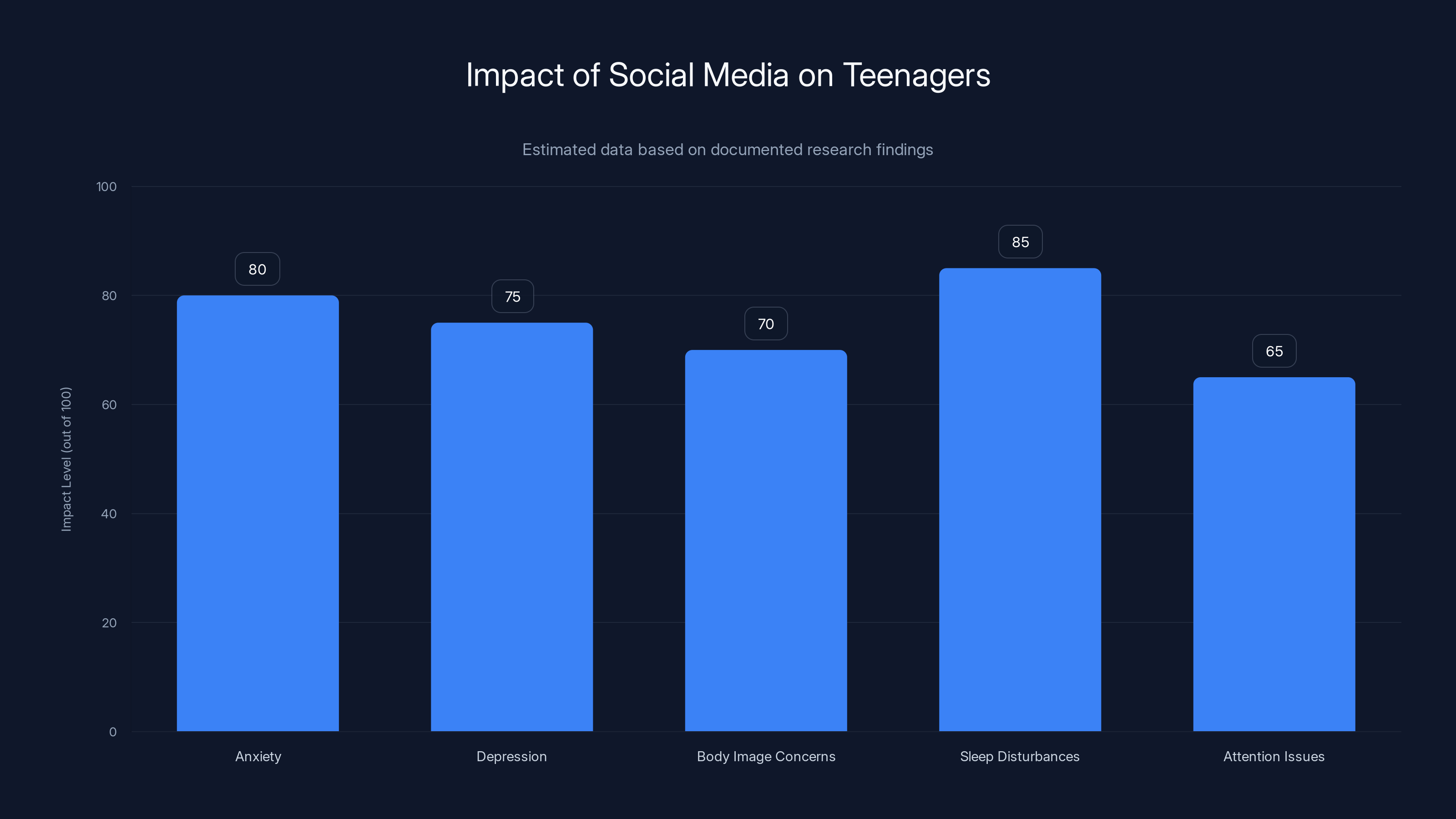

Estimated data suggests that sleep disturbances and anxiety are the most reported impacts of social media on teenagers, followed by depression and body image concerns.

The Courtroom Argument: Meta's Legal Strategy Explained

When Meta's attorney Kevin Huff stood before a jury in New Mexico, he made a precise claim. He held up documentation about the DSM, the diagnostic manual that mental health professionals use in the United States. He told the jury that the American Psychiatric Association studied social media addiction and decided it wasn't a legitimate clinical condition. Therefore, he argued, social media addiction is simply not a thing.

This argument has a surface appeal. The DSM-5-TR is, after all, the gold standard for mental health diagnoses in the United States. When the American Psychiatric Association decides that a condition doesn't warrant inclusion in the manual, that carries weight. Insurance companies use DSM diagnoses to determine coverage. Therapists use them to categorize patient presentations. Researchers use them to define their field of study.

So Meta's logic tracked: no DSM diagnosis equals no legitimate addiction.

Except that's not what the American Psychiatric Association actually said. When asked directly about Meta's claims, the APA responded with careful precision. Social media addiction isn't currently listed as a diagnosis in the DSM-5-TR. But that does not mean it doesn't exist. The organization maintains resources about social media addiction on its website. It acknowledges the phenomenon. It just hasn't formalized it into a diagnostic category yet.

The distinction matters because it reveals how the DSM actually works. The manual documents diseases and conditions that have reached scientific consensus through decades of research. Getting something into the DSM isn't a rubber stamp of existence—it's a formalization of already-established consensus. Conditions get listed after they've been studied extensively and psychiatrists across the field agree on diagnostic criteria.

Social media addiction hasn't reached that stage yet, but that's different from not existing.

Meta's argument essentially weaponizes the absence of a formal diagnosis. It conflates "not yet officially classified" with "doesn't exist." It's a clever legal move that shows the company understood exactly what it was doing. By narrowing the definition of addiction to only conditions in the DSM, Meta hoped to preclude the testimony and evidence that might otherwise convince juries that social media can be addictive.

What Meta didn't account for was how thoroughly this argument would be challenged by actual researchers who study social media effects.

Estimated data shows that 40% of perspectives recognize social media addiction, 30% deny it, and 30% are under legal scrutiny. (Estimated data)

The Scientific Reality: What Researchers Actually Know About Social Media Addiction

Dr. Tania Moretta, a clinical psychophysiology researcher who studies social media addiction, provided clarity that Meta's arguments tried to obscure. The absence of a DSM classification doesn't prevent a behavior from being addictive, maladaptive, or clinically significant. It reflects a misunderstanding of how psychiatry actually progresses.

Diagnostic manuals formalize scientific consensus. They don't define the boundaries of legitimate scientific inquiry. Many behaviors get studied and treated extensively before receiving official classification. Consider the history of depression, PTSD, or autism spectrum disorders. Each was recognized and treated for years before receiving full DSM inclusion or before the classification expanded to encompass what researchers actually observed in clinical practice.

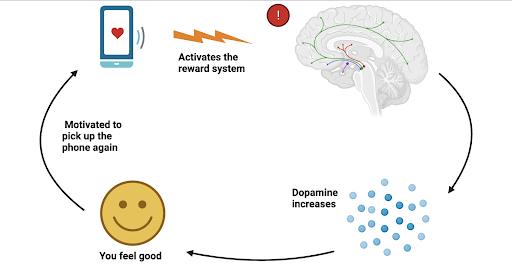

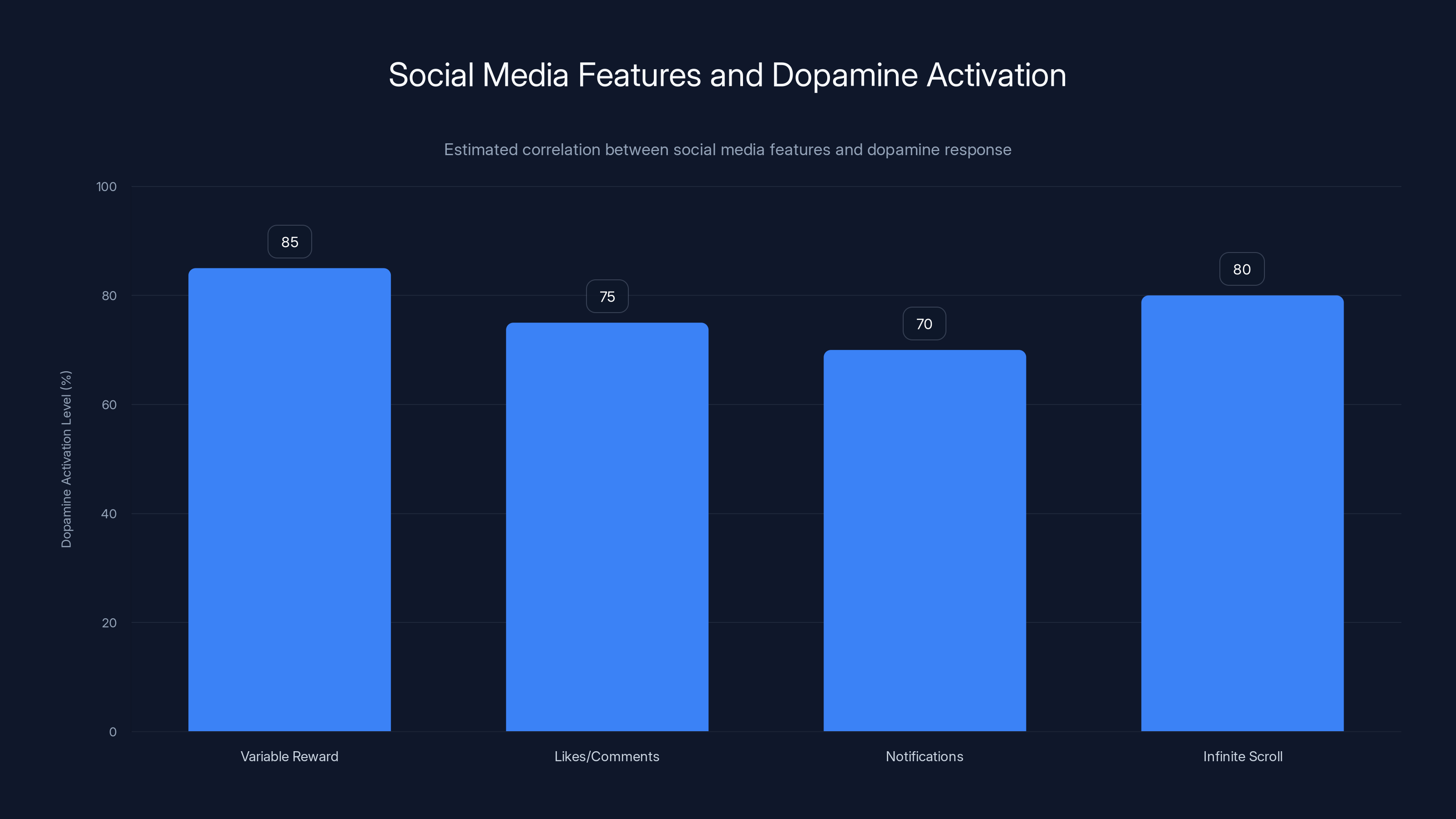

The scientific evidence on social media's addictive potential is actually quite substantial, even without DSM formalization. Researchers have documented that social media use can trigger dopamine responses similar to other reward-based behaviors. The platform algorithms that determine what content users see are deliberately designed to maximize engagement through principles borrowed from behavioral psychology and neuroscience. These aren't controversial claims—they're foundational to how platforms are built.

Studies have shown that specific social media features correlate with increased dopamine and reward system activation in the brain. The variable reward schedule—the unpredictability of when you'll see content you like—mirrors the same mechanisms that make slot machines psychologically compelling. Platforms use this deliberately. The design is intentional. The effects are measurable.

Moretta documented that social media use disorder is associated with psychophysiological alterations. Users show changes in reward and motivational systems, as well as inhibitory and regulatory systems. More importantly, they experience clinically significant negative impacts on functioning. Sleep disturbances. Psychological distress. Impairment in social, academic, and occupational domains. These aren't hypothetical concerns. They're documented outcomes measured in research.

The research base continues to grow. As of 2024 and 2025, more than a thousand peer-reviewed studies have examined social media's psychological and neurological effects. Major institutions like Stanford, MIT, and universities worldwide have research centers dedicated to understanding technology's impact on mental health.

One critical distinction Moretta emphasized: the key question isn't whether all social media use is addictive. Obviously it isn't. Billions of people use social media without developing compulsive use patterns. The question is whether a subset of users exhibits patterns consistent with behavioral addiction models. The answer to that question is clearly yes.

Moreover, evidence suggests that specific platform design features may exacerbate vulnerability in predisposed individuals. This matters legally because it implies something stronger than just "some people happen to develop addictive behaviors." It suggests that certain designs make addiction more likely—that there's a causal pathway from feature design to harmful outcomes.

Understanding Behavioral Addiction: The Science Behind the Compulsion

Before getting deeper into the trials and their implications, it helps to understand what behavioral addiction actually is from a scientific standpoint. It's not just about doing something frequently. It's about losing control despite negative consequences.

Behavioral addictions share core characteristics with substance addictions. Users experience cravings and withdrawal symptoms when unable to engage in the behavior. They exhibit tolerance, needing escalating amounts of the behavior to achieve the same psychological effect. They experience loss of control—continuing the behavior despite genuinely wanting to stop. They experience negative consequences in important life areas but persist with the behavior anyway.

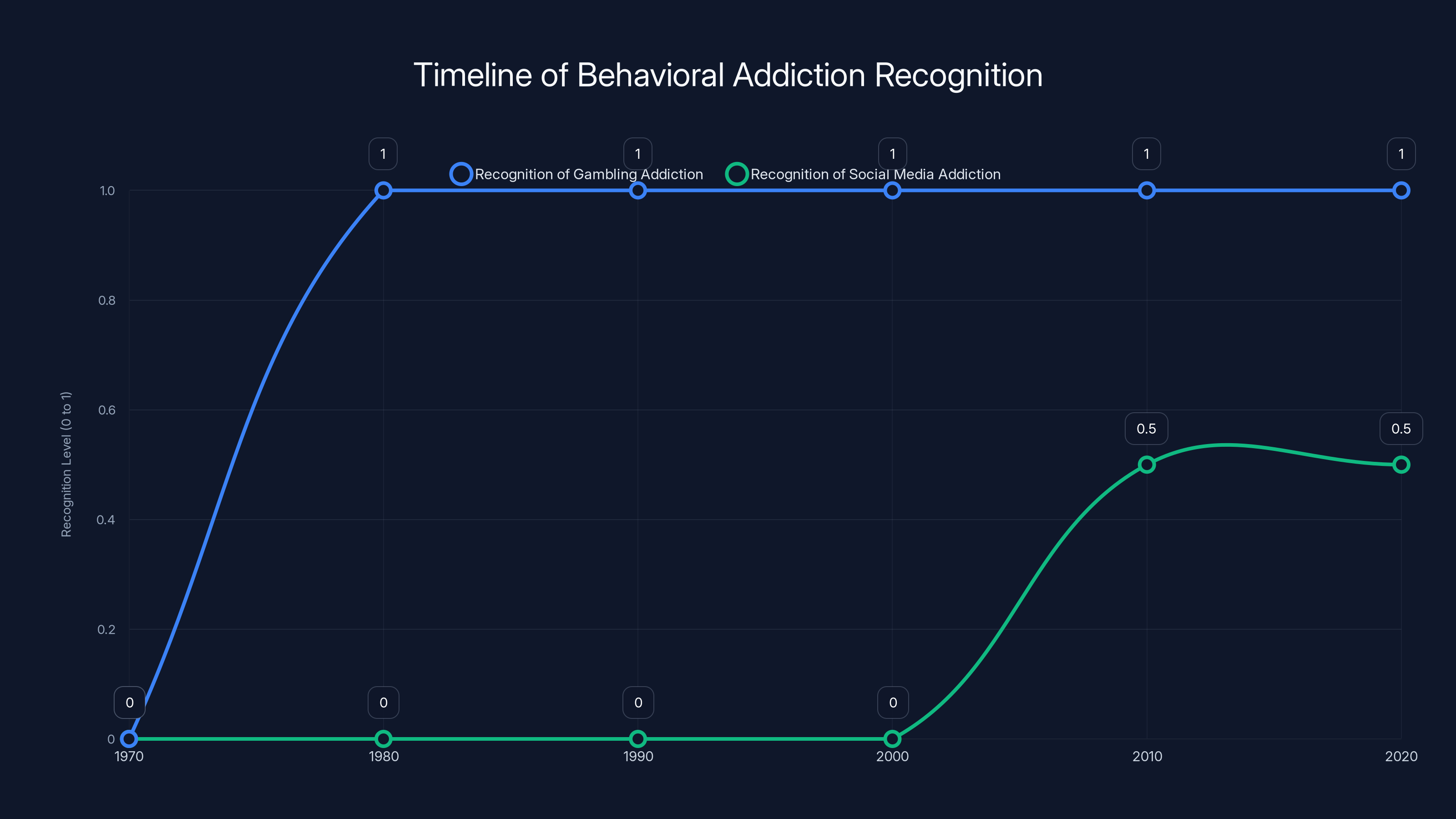

Gambling addiction provides the clearest comparison. Gambling addiction was historically not recognized as a clinical disorder either, yet therapists treated it, researchers studied it, and its devastation was undeniable. Only in 1980 did the DSM-III finally include "pathological gambling" as a diagnosis. That's decades after the condition was clearly documented and causing real harm.

The DSM inclusion of gambling disorder didn't create the condition. It acknowledged what was already happening and already being studied. Social media addiction exists in a similar interim space. It's actively being researched. People are experiencing documented harm. Treatments are being developed. But the formal DSM classification hasn't yet happened, and the process could take years.

When Mosseri testified that social media isn't "clinically addictive," he was using clinical in a narrow technical sense—meaning formally diagnosed in a clinical manual. That's a very different claim from saying it can't be psychologically addictive or behaviorally compulsive.

The comparison to Netflix was particularly revealing. Mosseri suggested you could be "addicted" to a Netflix show in the same colloquial way people use the word "addiction" for many things. But streaming television isn't algorithmic in the same way social media is. A Netflix show ends. Social media doesn't. Netflix's algorithm suggests content but doesn't employ the variable reward schedules that social platforms use. The comparison underestimated the technological sophistication of what makes social media engagement different from passive television consumption.

The neuroscience underlying behavioral addiction is increasingly well understood. Dopamine, the neurotransmitter associated with reward and motivation, plays a central role. When you receive a like on social media, your brain experiences a dopamine hit. When you're uncertain whether the next scroll will bring positive content, the unpredictability amplifies dopamine response. This is neurobiologically real and measurable via brain imaging studies.

Over time, with repeated engagement, brain regions involved in reward processing and impulse control show measurable changes. The prefrontal cortex—responsible for executive function and impulse inhibition—shows reduced activation in people with behavioral addictions. This isn't people being weak-willed. This is neurological adaptation to repeated dopamine stimulation.

Platforms understand this neuroscience intimately. They employ teams of engineers and psychologists specifically to optimize engagement. The red notification badges, the infinite scroll, the algorithmic feed that serves increasingly engaging content, the streaks that track consecutive days of use—these are all features designed with knowledge of how dopamine and habit formation work. They're not accidental. They're engineered.

Gambling addiction was officially recognized in 1980, while social media addiction is still in the process of gaining formal recognition. Estimated data.

The Trials: What's Actually at Stake in These Courtrooms

The New Mexico case and the Los Angeles case represent different legal theories but converge on a similar core question: can Meta be held liable for harms resulting from design choices meant to maximize user engagement?

In New Mexico, state attorney general Raúl Torrez has accused Meta of facilitating child exploitation and harming children through addictive features. The theory here is that Meta knowingly designed features to be compulsive, making children more vulnerable to exploitation. New Mexico's attorney general has argued that Meta's engagement optimization directly contributed to the platforms becoming tools for predators.

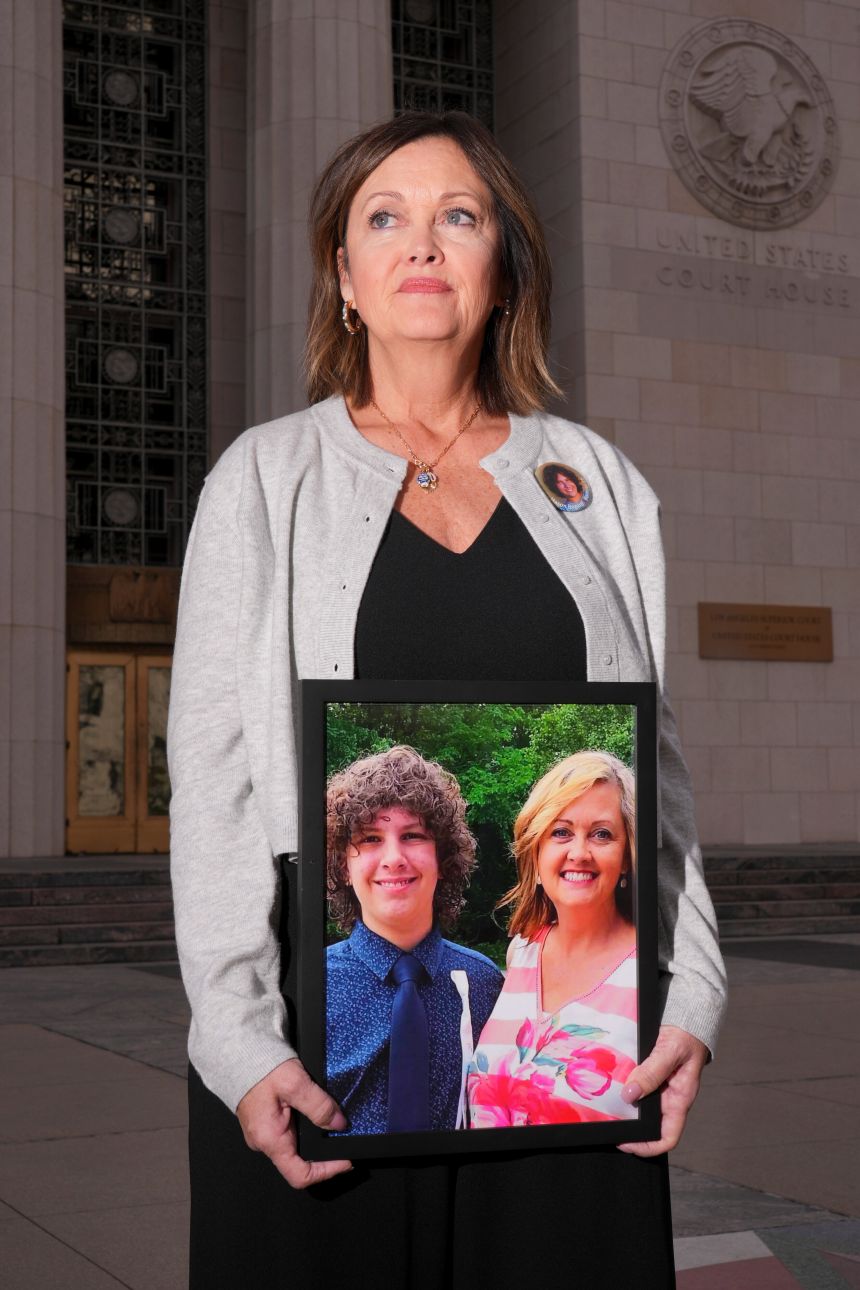

The Los Angeles case involves a California woman suing Meta for mental health harms. The complaint alleges that Meta and other platforms made deliberate design choices—features they knew or should have known were addictive—that caused her psychological harm. This case tests whether individuals can sue corporations for damages resulting from addictive platform design.

But these are just the beginning. Meta faces a high-profile trial with school districts scheduled for June. That case will involve school systems suing Meta for the educational and behavioral harms they're witnessing in students. Additionally, 41 state attorneys general have filed lawsuits against the company.

The courts hearing these cases will need to grapple with foundational questions: What counts as evidence of addiction? If the DSM doesn't have a diagnosis, can someone still claim addictive harm? Can you hold a company liable for a user's choices to engage with their platform, even if the platform was designed to encourage engagement?

The fact that Meta's defense relies on a technical argument about DSM classifications rather than contesting the evidence of engagement optimization or the documented harms tells you something important. Meta isn't really arguing that its platforms don't maximize engagement. It's not claiming the engagement optimization doesn't work. It's arguing that even if all of that is true, it doesn't constitute addiction because addiction doesn't exist without a DSM diagnosis.

This is a legal strategy that might work in some courtrooms and fail in others. It depends on how judges interpret the relationship between clinical classification and evidence of harm.

The Internal Documents: What Meta Knew and When It Knew It

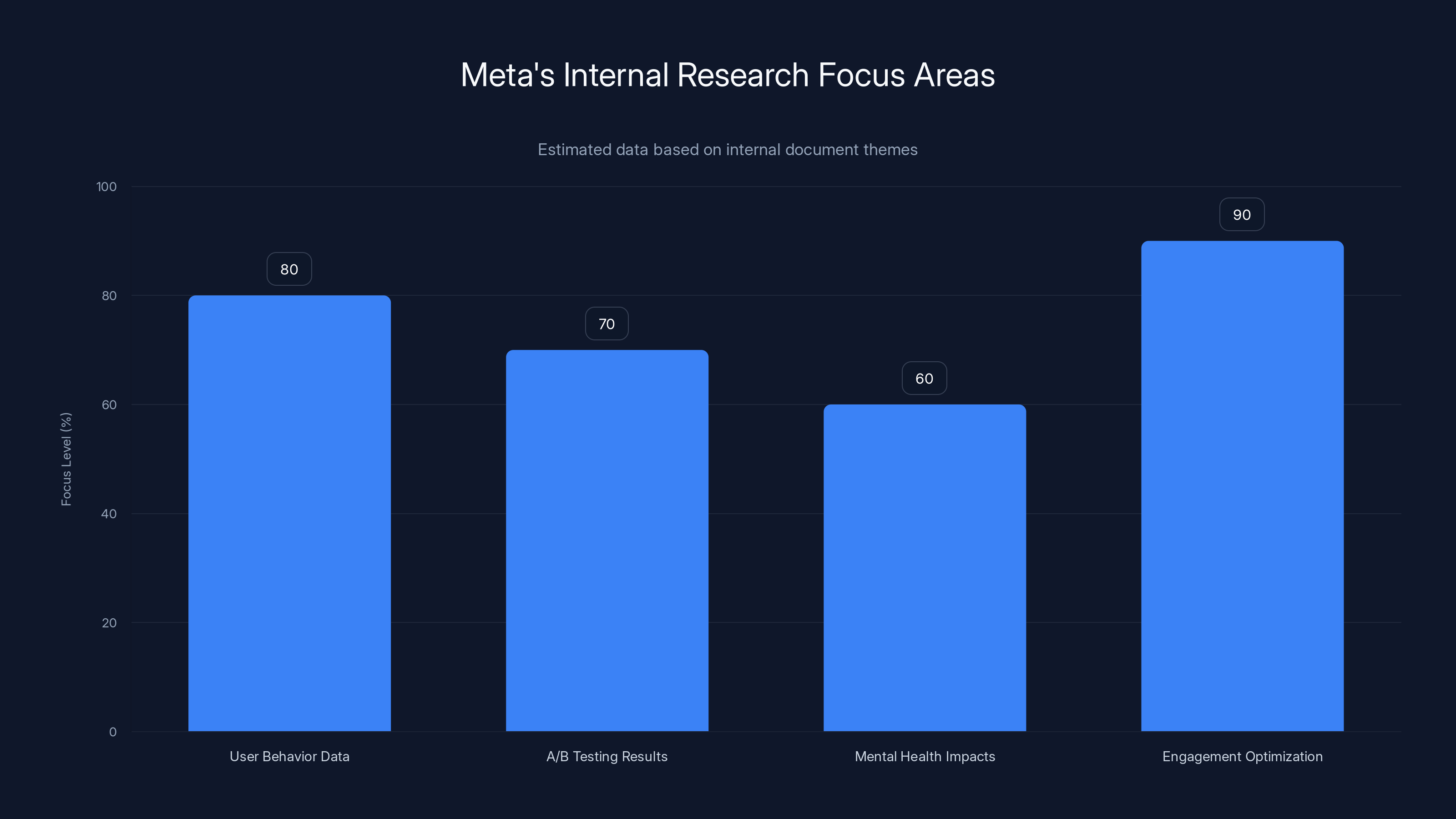

One of the most significant aspects of these trials will be the disclosure of Meta's internal research and communications. The company has conducted extensive research into how its platforms affect young users' mental health. This research wasn't done for academic purposes. It was internal, proprietary work investigating the company's own products.

Former executives and whistleblowers like Arturo Bejar and Brian Boland have already testified about their concerns regarding Meta's safety priorities. Bejar, who worked in product management at Meta, has publicly stated that the company prioritized growth and engagement metrics over safety. Boland, a former director of product management, has similarly raised concerns about Meta's approach to platform harms.

The internal documents these individuals will reference are crucial because they show what Meta knew internally versus what it claimed publicly. If Meta's own research showed that certain features increased addictive use patterns, but the company nevertheless maintained those features or even amplified them, that knowledge becomes relevant to claims of negligence or liability.

Moreover, if internal documents show that Meta specifically understood and discussed the addictive properties of certain features—variable rewards, engagement optimization, algorithmic feeds designed to maximize time spent—then Meta can't argue it didn't know its platforms worked that way. That knowledge is necessary context for any judicial assessment of liability.

These documents likely include user behavior data, A/B testing results showing which features drive increased engagement, and potentially internal discussions about mental health impacts. This is the evidence that will likely matter more than abstract arguments about whether addiction exists as a DSM diagnosis.

Estimated data suggests Meta's internal research heavily focused on engagement optimization and user behavior data, reflecting priorities over safety. Estimated data.

The Expert Witness Battle: Whose Science Counts in Court

Both sides will bring expert witnesses. Meta will likely produce psychiatrists and neuroscientists who argue that without formal DSM classification, we shouldn't treat social media compulsive use as an addiction in the legal sense. They might argue that correlation between platform use and mental health issues doesn't prove causation. They might distinguish between problematic use and addiction.

The plaintiff side will bring experts like Moretta and others who can explain the neuroscience of dopamine and reward systems, the similarity between social media's engagement mechanisms and known addictive patterns, and the clinical significance of the documented harms. They'll argue that the absence of DSM classification doesn't negate the scientific reality of the phenomenon.

This expert witness battle is crucial because it will shape what the jury understands about addiction, about how research actually works, and about what we can reasonably infer from neuroscience about behavior change and harm.

One particularly effective type of evidence will likely be expert testimony about the intentionality of Meta's design choices. If experts can credibly explain that infinite scroll, algorithmic feeds, notification badges, and streaks are all deliberately engineered to maximize engagement based on known principles of behavioral psychology, that shifts the conversation. It moves from "some people happen to develop problematic use" to "Meta designed features specifically because they knew they would be engaging to the point of compulsivity."

That intentionality distinction matters enormously for liability. A company isn't usually held liable just because some users have problems with their product. They can be held liable if they knowingly designed products in ways they understood would cause specific harms, particularly to vulnerable populations like children.

The Diagnostic Dilemma: Why the DSM Matters and Why It Doesn't

To fully understand the legal battle, you need to appreciate why the DSM is both important and somewhat beside the point in these cases.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders is genuinely important. It provides a shared language for mental health professionals. It ensures that when therapists across different parts of the country use the term "major depressive disorder," they mean essentially the same thing. It guides insurance coverage decisions. It shapes research priorities. It's not a trivial document.

But the DSM is also, in some ways, a lagging indicator. It documents what the psychiatric profession has already established. It doesn't lead innovation in mental health understanding. It follows it.

The question of whether social media addiction should be in the DSM is genuinely interesting and will likely be resolved in the next several years as more research accumulates. The American Psychiatric Association isn't suppressing social media addiction from the manual out of deference to Meta. It's being methodical because diagnostic inclusion requires establishing clear criteria that clinicians worldwide can use consistently.

Social media addiction is complicated to define precisely because "social media" isn't one monolithic thing. Someone might have problematic use of one platform but not others. The addictive potential might differ between platforms with different algorithms. The age of the user matters enormously. What looks like addiction in a 14-year-old might look like normal teenage behavior. These complications are real and explain some of the hesitation about formal classification.

But from a legal perspective, the presence or absence of a DSM diagnosis shouldn't determine whether people can sue for harms. Law regularly recognizes harms based on evidence that precedes formal medical classification. People successfully sued tobacco companies for lung cancer damage years before it was universally acknowledged that smoking caused cancer. People have recovered damages for workplace injuries before OSHA standards were officially established.

The legal standard isn't whether something has a DSM diagnosis. It's whether a company's knowable actions caused foreseeable harm. If Meta designed features it knew would increase engagement, and if that increased engagement correlated with documented psychological harm, and if children were particularly vulnerable, then there's a plausible case for liability regardless of whether the DSM has classified social media addiction.

Estimated data shows potential outcomes of tech trials, with liability for addictive design and regulatory changes being significant possibilities.

The Impact on Young Users: Where the Harm Is Most Documented

One critical aspect of these trials is their focus on harm to children and teenagers. The research on social media's impact on young people is more developed than for adults, and the harms are more clearly documented.

Adolescent brains are still developing, particularly the prefrontal cortex responsible for impulse control and long-term planning. That developmental reality makes teenagers particularly vulnerable to compulsive use patterns. Moreover, social comparison—a central feature of platforms like Instagram—hits differently in adolescence. Teen self-esteem is more dependent on peer perception. The quantified social validation (likes, comments, shares) that social media provides is neurologically potent for this age group.

Research has documented correlations between heavy social media use and increased anxiety, depression, and body image concerns among teenagers. Sleep disturbances are particularly common—the constant engagement and the blue light from screens both interfere with normal sleep cycles, and sleep deprivation amplifies anxiety and depression.

School systems across the country have reported increasing behavioral and mental health challenges correlated with social media use. Attention spans are fragmenting. Self-harm and suicidal ideation have increased, particularly among teenage girls. These changes have coincided with smartphone and social media adoption in ways that suggest causal relationships, even if causality isn't definitively proven.

For young people, the addictive potential of social media isn't speculative. It's observable in real time. Teachers report students unable to focus because they're mentally elsewhere, thinking about their social media presence. Parents report constant phone usage despite explicit requests to put devices down. Young people themselves report feeling unable to stop scrolling despite wanting to.

This real-world evidence of compulsive use that young people struggle to control—that persists despite negative consequences—fits the definition of addiction whether or not the DSM has formally classified it.

The Business Model Conundrum: How Engagement Drives Everything

Underlying all these legal arguments is a fundamental reality about how Meta makes money. The company's business model depends entirely on user engagement. Advertisers pay to reach engaged users. More engagement means higher prices for advertising. Maximizing engagement is the company's core business objective, not a side effect.

This creates an inherent tension. For Meta to be maximally profitable, users need to spend as much time as possible on the platforms. The design features that maximize engagement—infinite scroll, algorithmic feeds, variable rewards—are core to the business model. They're not bugs or unfortunate side effects. They're the entire point from Meta's perspective.

So when Meta argues that social media addiction isn't real, it's defending not just its legal liability but its fundamental business model. If courts recognize that certain platform design choices make compulsive use more likely, and if Meta is held liable for those harms, the company would face pressure to change those design choices. That would presumably reduce engagement and therefore reduce profitability.

This explains why Meta is fighting so hard on the definitional question of whether addiction exists. It's not really about whether the science is sound. It's about whether the courts will require the company to redesign its platforms in ways that reduce addictive potential, even if that means reduced engagement and revenue.

This also explains why Meta's defense seems to rely on a technicality. The company knows that directly contesting the evidence of engagement optimization and documented harms would be difficult. The evidence is substantial. So instead, the strategy is to argue that harms aren't "addiction" in the strict sense, and therefore the company isn't liable.

Estimated data shows that features like variable rewards and infinite scroll are designed to maximize dopamine activation, similar to mechanisms in gambling.

Precedent and Outcomes: What These Trials Could Mean

The outcomes of these trials will likely shape technology regulation for years. If courts find that Meta can be held liable for addictive platform design, that precedent will extend to other tech companies. Tik Tok, You Tube, Snapchat, and emerging platforms will all face similar scrutiny.

Conversely, if courts accept Meta's argument that without a DSM diagnosis, addiction claims don't hold up, that precedent could shield the entire industry from liability for addictive design.

The school district trial scheduled for June will be particularly important. School systems have clear standing to argue that platform addiction is harming their students' educational outcomes. They have quantified data about attention problems, behavioral issues, and mental health crises. If schools succeed in establishing that addictive platform design harms students in measurable ways affecting their education, that's a powerful validation of the harm theory.

The 41 state attorneys general cases provide another avenue of pressure. Individual states don't need to prove addiction caused specific harm to specific people. They can argue based on aggregate impact that Meta's platform design practices violate consumer protection laws or constitute deceptive practices. These cases might be easier to win than individual lawsuits because the legal standard is different.

What seems likely is that the addiction question will eventually be resolved through a combination of factors. As more research accumulates and the scientific consensus solidifies, the DSM-5-TR will eventually be updated to include social media addiction or something similar. Regulatory bodies in Europe and eventually the US will likely impose requirements for platforms to limit addictive features. Litigation will establish liability precedents. And the cultural conversation will shift away from "is this addiction?" to "of course this is addictive—what are companies going to do about it?"

Meta's current strategy—arguing addiction doesn't exist—is likely buying time rather than winning a permanent victory. But time matters enormously. Every year of delay means more revenue from addiction-optimized platforms. Every year of litigation means resources spent on lawyers rather than redesigning features. For Meta, even delaying regulatory change is a win.

The Addiction Evolution: How Other Industries Have Faced This

Meta isn't the first industry to resist acknowledging that its products are addictive. The tobacco industry spent decades arguing that nicotine addiction wasn't proven, wasn't understood, or wasn't really addiction in the clinical sense. The gambling industry fought against addiction recognition. The pharmaceutical industry resisted acknowledging that painkillers could be addictive.

In each case, the industry's core defense relied on definitional arguments. Addiction wasn't officially recognized or understood. The evidence was debated. Individual responsibility mattered more than product design.

And in each case, the industry eventually lost. Scientific evidence accumulated. Regulatory bodies acted. Litigation established liability. The conversation moved past the definitional question to focus on solutions.

Meta's situation follows a similar arc, but with an important difference. Tobacco took decades to settle because the health harms were long-term and statistical. Gambling addiction harms were concentrated in a vulnerable subset of users. Social media addiction harms are acute, measurable, and concentrated in the young people platforms most aggressively target.

Moreover, the solutions for social media addiction are more straightforward than for tobacco or gambling. You can't make cigarettes less addictive without making them worthless. You can't make gambling machines less addictive without removing the gambling. But you absolutely can make social media less engagement-optimized without making the platforms worthless. You could remove infinite scroll. You could reduce algorithmic amplification. You could limit notifications. You could implement time limits. The platforms would still function. They'd still be valuable. They'd just be less addictive.

The fact that Meta doesn't want to make these changes, doesn't argue that addiction doesn't exist—it argues that the company values maximum engagement over user wellbeing, even when addiction-related harms are affecting children.

Global Implications: How Other Countries Are Responding

While Meta fights these battles in US courtrooms, other countries are already moving past the addiction definitional question to regulatory action. The European Union has been particularly aggressive, with regulations like the Digital Services Act specifically addressing addictive design features in online platforms.

European regulators aren't waiting for the DSM to classify social media addiction. They're legislating based on the evidence that certain design choices make compulsive use more likely, particularly for young people. This approach sidesteps the addiction debate entirely. The regulations don't require proving addiction exists. They just require limiting features known to maximize engagement.

Australia has taken similar approaches, with regulatory proposals that would restrict algorithmic feeds for users under 18 and limit notifications designed to drive engagement. These regulations treat engagement optimization as a problematic practice in itself, regardless of whether you call the result "addiction."

This global regulatory movement will ultimately matter more than any single US trial outcome. Once the major markets of the EU and eventually Australia regulate platform design features, Meta will have to change those features in those regions. Maintaining different versions of platforms for different regions is possible but expensive and complicated. More likely, Meta will eventually implement changes globally, making the addiction question moot.

The US regulatory environment lags behind Europe and Australia, which gives US courts and state legislatures an opportunity to lead or follow. If US trials establish liability, that creates momentum for US regulation. If US courts don't establish liability, regulation might still happen but will likely be less specific about platform design and more about data privacy or other issues.

The Role of Whistleblowers: Inside Information Turns Tide

One factor that will likely prove decisive in these trials is testimony from people who worked inside Meta and saw the decision-making that led to current platform design.

Arturo Bejar was a product manager who worked on safety and wellbeing at Meta. His testimony will be crucial because he can speak to internal knowledge about how platforms affected users and what the company knew about these effects. Brian Boland similarly worked in product roles and can testify about how engagement metrics drove decision-making.

Whistleblower testimony is powerful in litigation because it provides direct evidence of what the company knew, when it knew it, and how that knowledge influenced product decisions. If Bejar or Boland can testify that Meta's internal research showed certain features increased addictive use but the company maintained or amplified those features anyway, that undermines Meta's defense that it didn't know about addiction risks.

Moreover, whistleblower testimony often influences settlement discussions. Companies facing the prospect of executives testifying about internal knowledge often conclude that settlement is preferable to having that testimony in the public record. Settlement doesn't mean an admission of guilt, but it means accepting that litigation risk justified paying damages.

These whistleblower testimonies represent a shift in how tech accountability happens. Rather than external researchers and advocates being the only critics, insiders are stepping forward. That carries weight in courtrooms and in public perception.

Financial Implications: What Liability Could Cost

If Meta loses these trials or settles major cases, the financial implications could be substantial. School district cases could involve damages for thousands or tens of thousands of students. Individual class actions could scale to millions of users. State attorney general settlements could include massive penalties.

For a company as profitable as Meta, legal liability isn't the primary concern. The company has cash reserves to handle large settlements. The real concern is regulatory change that would force redesign of core platform features.

If courts establish that Meta can be sued for addictive design, that precedent extends to all tech platforms. Every major tech company would face similar liability exposure. The industry would collectively face pressure to reduce engagement optimization. That would reduce profitability across the board.

Meta's fight against addiction recognition is partly a financial fight, but it's also an industry-wide fight. If Meta loses, the entire ad-supported platform model becomes riskier. That's what really motivates the company's aggressive legal defense.

Conversely, if Meta successfully argues that addiction doesn't exist without DSM classification, that victory only lasts until the DSM updates or until different courts accept different standards. The legal environment for tech platforms will eventually shift because the evidence and the political pressure are just too strong.

The Regulation Question: What Happens If Meta Wins

Even if Meta successfully defeats these trials—if courts accept that addiction requires DSM classification and therefore addictive design isn't actionable—regulatory change would still likely follow.

State legislatures don't wait for litigation outcomes to regulate industries. If public concern about platform harms is high enough, elected officials will pass laws restricting platform design regardless of whether addiction has been proven in court. We've already seen preliminary bills in various states restricting platform features for minors, limiting algorithmic recommendation, and requiring transparency about engagement optimization.

Federal regulation could also happen, though Congress moves slowly. But the political pressure is building, particularly as more parents and educators report observable harms to young people from social media use.

So Meta's best-case scenario—winning the litigation—might still result in redesigned platforms due to regulation. The company's strategy seems to be about delaying change, not preventing it. Every year that addictive features remain in place means additional revenue. Once regulation or liability forces changes, that revenue disappears.

From Meta's perspective, legal victory is valuable even if regulatory loss eventually follows. The gap between them means years of continued profitability from the current model.

What Comes Next: The Trials Unfolding

As these trials continue through 2025 and into 2026, watch for several key developments. The testimony of Mark Zuckerberg, expected in the Los Angeles trial, will be significant. His testimony could reveal knowledge about addiction or engagement optimization that becomes central to liability questions.

The disclosure of internal Meta documents will shape how juries understand the company's decision-making. If those documents show discussions of addictive features or acknowledgment of mental health impacts, that's powerful evidence. If they show the company deliberately ignored safety concerns in favor of engagement growth, that's even more powerful.

The expert witness testimony will establish for the jury what addiction is, what the science shows about social media's effects, and how relevant platform design features work. That testimony will largely determine whether jurors understand themselves to be deciding whether addiction exists, or whether addiction exists and the question is only whether Meta is responsible.

The results in New Mexico will likely influence the Los Angeles case and the school district case. If Meta wins in New Mexico, they'll use that precedent aggressively. If they lose, they'll face settlement pressure in the other cases.

Regulatory developments will parallel the litigation. As more states propose laws restricting platform design, that creates additional pressure on Meta. The company can fight individual lawsuits. Fighting multiple state regulatory efforts simultaneously is harder.

The Bigger Picture: Society's Reckoning With Technology

These trials represent something broader than just Meta's legal problems. They represent a society-wide reckoning with how technology is designed and what obligations companies have for how their designs affect users.

For years, tech companies have positioned themselves as neutral platforms. They provide tools. What users do with those tools is users' responsibility. That framing is increasingly being rejected. Regulators, courts, and the public are recognizing that how tools are designed shapes how people use them. There's no such thing as a neutral algorithm. Every design choice influences behavior.

The addiction question is really about whether companies should be permitted to optimize designs for maximum engagement even when that causes documented harms, particularly to young people. Meta's position is that they should be. Their legal argument is just the technical mechanism through which they defend that position.

If these trials and future regulations establish that companies can't optimize designs for addictive engagement—that there are limits on engagement maximization when harms are documented—that represents a fundamental shift in how tech will be built going forward.

That shift is probably inevitable. The evidence is too strong. The harms are too documented. The public concern is too high. Meta's legal strategy might delay it, but won't prevent it.

The question isn't whether social media addiction exists. It exists. The question is when companies will be held accountable for designing products to be maximally addictive, and when that accountability will reshape the tech industry toward designs that prioritize user wellbeing over maximum engagement.

FAQ

What is social media addiction?

Social media addiction refers to compulsive social media use that causes documented harm despite the user's desire to reduce or stop using the platforms. It involves loss of control over usage, tolerance requiring increased time spent to achieve satisfaction, and withdrawal symptoms when unable to access the platforms. While not yet formally classified in the DSM-5-TR, social media addiction shows characteristics consistent with behavioral addictions and is actively studied by neuroscientists and psychologists worldwide.

Why does Meta claim social media addiction doesn't exist?

Meta argues that social media addiction isn't a clinical condition because it hasn't been formally included in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. However, this argument conflates lack of formal classification with non-existence. Many conditions are studied and treated extensively before receiving DSM inclusion. The company uses this definitional argument to defend against liability in court, though it doesn't address the scientific evidence showing that social media can trigger addiction-like patterns.

What does the American Psychiatric Association actually say about social media addiction?

The American Psychiatric Association has explicitly stated that while social media addiction isn't currently listed as a diagnosis in the DSM-5-TR, this doesn't mean it doesn't exist. The organization acknowledges social media addiction on its website and provides resources about it. The absence of a DSM classification reflects the need for further research and consensus before formal inclusion, not a denial of the phenomenon's reality.

How are courts handling these trials?

Multiple trials are occurring simultaneously—cases in New Mexico and Los Angeles are actively proceeding with expert testimony about platform design and user harms, a school district case is scheduled for June, and 41 state attorneys general have filed separate suits. Courts will determine whether Meta can be held liable for addictive design even without a formal addiction diagnosis, and what evidence of harm is sufficient to establish negligence or deceptive practices.

What is the neuroscience behind social media addiction?

Research shows that social media engagement triggers dopamine release in the brain's reward centers, similar to other addictive behaviors. Platform features like notifications, likes, and algorithmic feeds are deliberately designed using principles of behavioral psychology to maximize this dopamine response. Studies document measurable changes in the prefrontal cortex and reward systems of heavy users, along with clinically significant impacts on sleep, mental health, and functioning.

What would change if Meta loses these trials?

If Meta is found liable for addictive platform design, the precedent would likely extend to other tech companies, creating widespread pressure to reduce engagement-optimizing features. This could result in removal of infinite scroll, reduced algorithmic amplification, limited notifications, and other design changes. While settlement doesn't require design changes, regulatory requirements that would likely follow liability findings would compel them.

Are other countries already regulating platform addiction?

Yes, the European Union's Digital Services Act specifically addresses addictive design features, and Australia has proposed regulations restricting algorithmic feeds and notifications for young users. These regulations don't wait for addiction to be formally diagnosed—they address engagement-optimization features themselves.

How do whistleblowers fit into these cases?

Former Meta employees like Arturo Bejar and Brian Boland are testifying about internal knowledge of how platform features affected users and what the company knew about these effects. This insider testimony is powerful because it provides direct evidence of company knowledge and decision-making, potentially undermining claims that Meta didn't understand addiction risks.

Why does the DSM classification matter?

The DSM provides a shared clinical language for mental health professionals and determines insurance coverage. However, the DSM documents what research has already established—it doesn't define the boundaries of legitimate research or prevent conditions from being real and harmful before formal classification. Many conditions were studied and treated for years before receiving DSM inclusion.

When will social media addiction be officially recognized?

There's no definitive timeline, but the American Psychiatric Association is likely to eventually include social media addiction in future DSM updates as research accumulates and scientific consensus solidifies. Internet Gaming Disorder was included in the appendix of DSM-5-TR as needing further research, suggesting social media addiction may follow a similar pathway.

What can individuals do about social media addiction?

Research-backed approaches include setting usage time limits, removing notification badges, using grayscale modes on devices, taking regular digital detoxes, and seeking therapy if compulsive use is causing documented harm. Some users find success with app blockers or device restrictions, while others benefit from joining communities focused on reducing platform dependency.

Meta's courtroom insistence that social media addiction doesn't exist represents a strategic legal move rather than an accurate representation of the science. The evidence is clear: platforms are designed to maximize engagement, that design succeeds in creating compulsive use patterns, and young people experience documented harms from that compulsive use. Whether you call it addiction or not, the harm is real.

What these trials will determine is whether Meta can be held financially and legally responsible for designing platforms to be maximally addictive, knowing that addictive use would cause harm. That's the actual question underneath all the arguments about DSM classifications.

The outcome will likely shape technology regulation for decades. If courts establish liability for addictive design, every tech company will face pressure to reduce engagement optimization. If Meta prevails on the definitional argument, the company buys time but doesn't prevent eventual regulatory change. The evidence is too strong. The harm is too documented. The public concern is too high.

What seems certain is that the current era of unregulated engagement optimization is ending. The only question is whether courts or regulators will drive that change. Meta's strategy is to slow it down. The science says it's inevitable.

Key Takeaways

- Meta's core legal argument conflates lack of DSM classification with non-existence of social media addiction, a distinction with major implications for liability

- The American Psychiatric Association explicitly disputes Meta's claims, stating that absence from the DSM doesn't mean social media addiction doesn't exist

- Neuroscientific evidence shows social media triggers dopamine responses and measurable brain changes consistent with behavioral addiction, regardless of formal diagnosis

- Multiple simultaneous trials in 2025-2026 will likely establish precedent for holding tech companies liable for addictive platform design features

- Global regulatory movements in EU and Australia are already addressing addictive design features without waiting for addiction definitions, likely forcing eventual US compliance

Related Articles

- Meta and YouTube Addiction Lawsuit: What's at Stake [2025]

- Meta's Child Safety Crisis: What the New Mexico Trial Reveals [2025]

- EU's TikTok 'Addictive Design' Case: What It Means for Social Media [2025]

- Good Luck, Have Fun, Don't Die: AI Addiction & Tech Society [2025]

- Social Media Safety Ratings System: Meta, TikTok, Snap Guide [2025]

- Meta's Child Safety Trial: What the New Mexico Case Means [2025]

![Meta's Fight Against Social Media Addiction Claims in Court [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/meta-s-fight-against-social-media-addiction-claims-in-court-/image-1-1770990063276.jpg)