45 Million French Records Leaked: What Happened & How to Protect Yourself [2025]

TL; DR

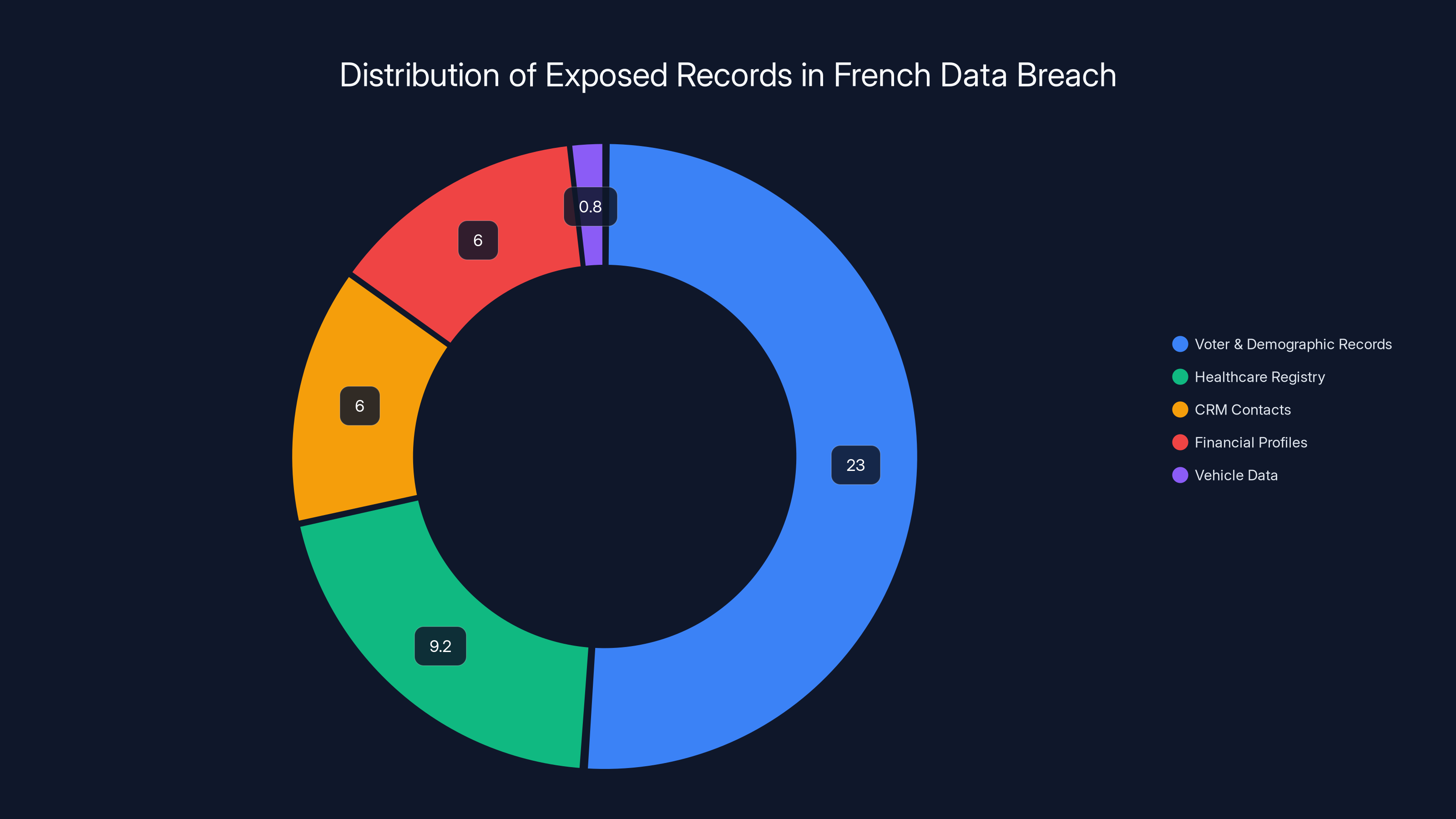

- The Scope: A cybercriminal aggregated 45 million records from at least five separate breaches, combining voter data, healthcare registries, financial information, CRM contacts, and vehicle registration data into one exposed database.

- The Method: This wasn't a typical data breach from one company—it was deliberately assembled by a data broker or criminal collector who merged stolen datasets to increase their value on the dark web.

- The Risk: The consolidated database enables phishing attacks, identity theft, wire fraud, and targeted social engineering at scale because attackers now have multiple data points about the same individuals.

- The Timeline: Security researchers at Cybernews discovered the exposed server in France and helped take it offline, but the database was publicly accessible for an unknown length of time.

- Your Action Items: Check if you're affected, enable fraud monitoring, use multi-factor authentication on financial accounts, and consider a credit freeze if you have French banking information exposed.

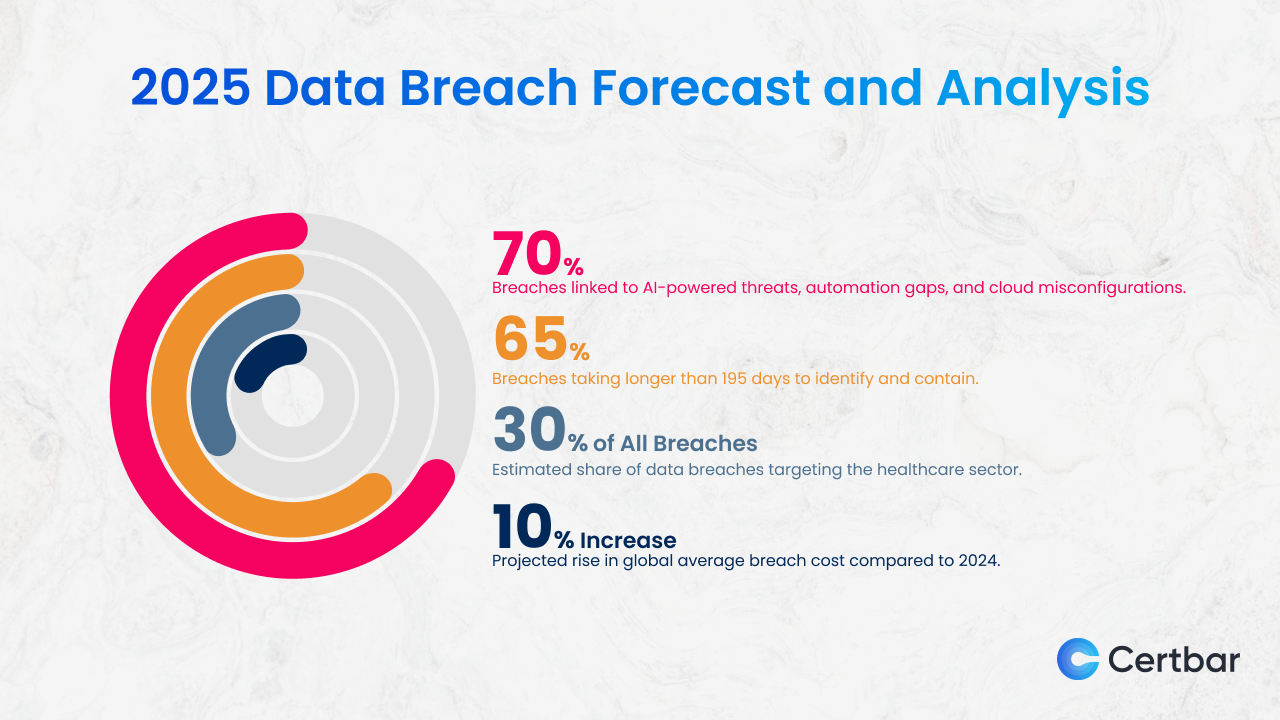

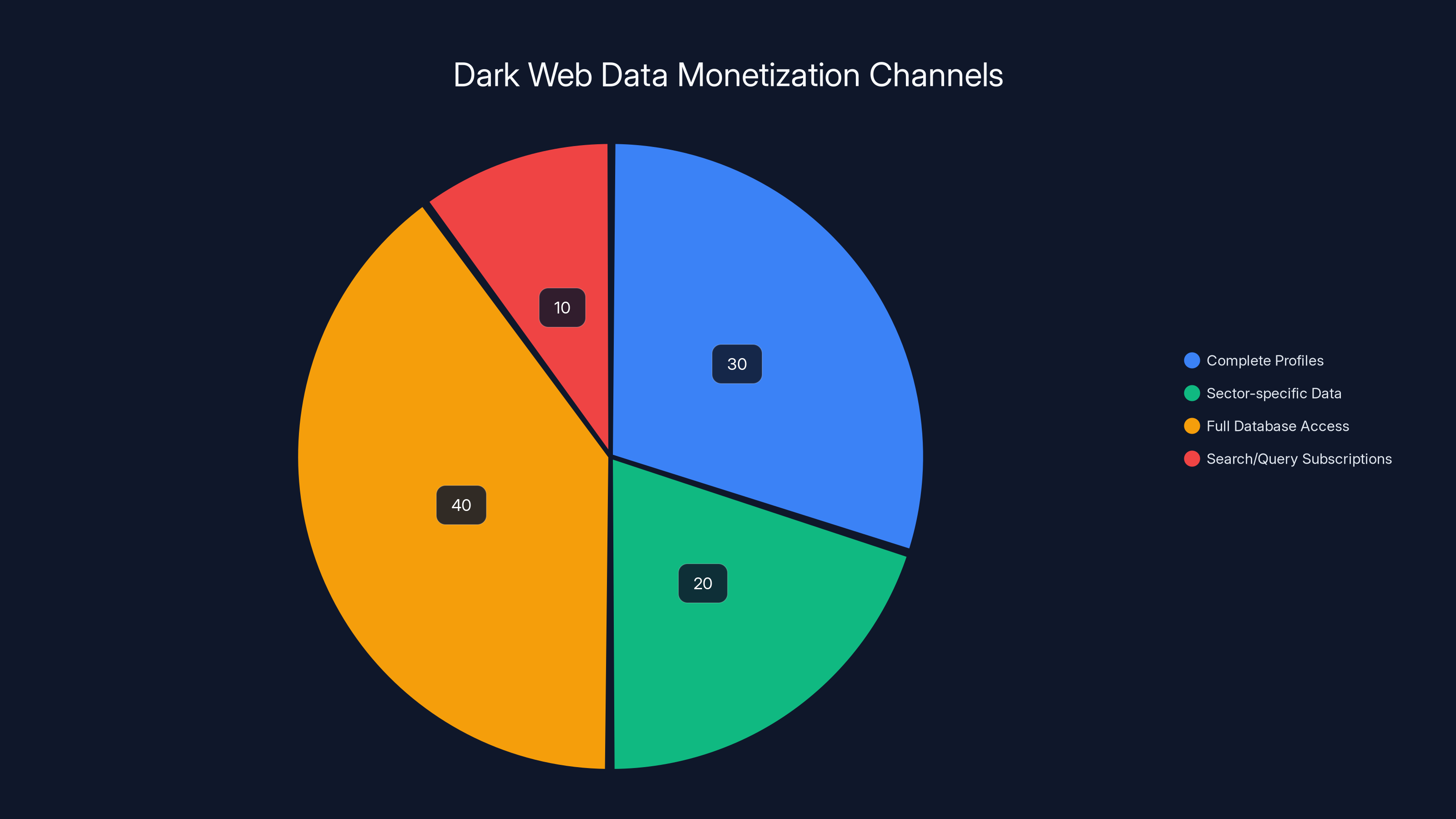

Estimated data shows that full database access and complete profiles are the most lucrative channels for monetizing data on the dark web, representing 70% of the market.

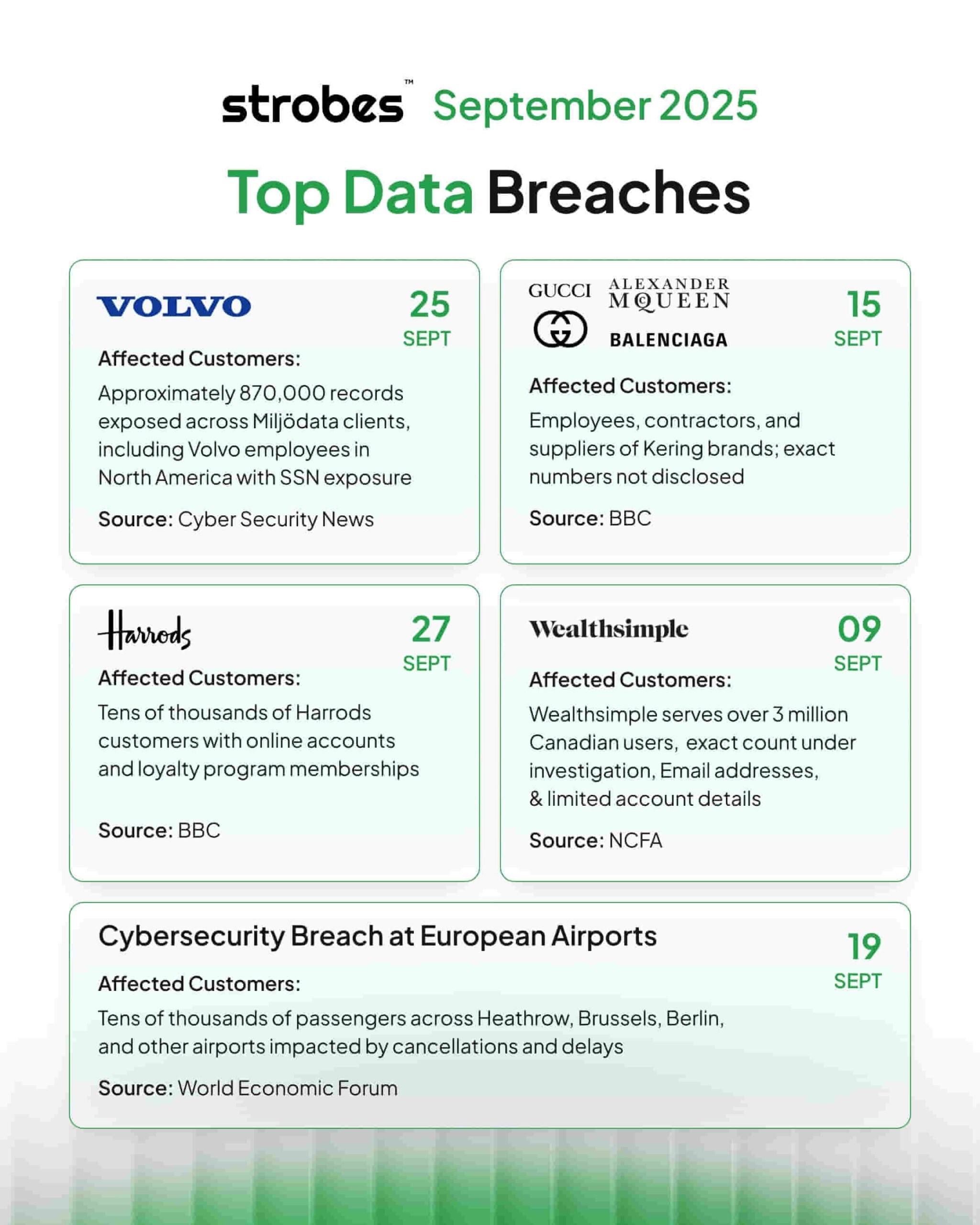

The Breach That Changed How We Think About Data Security

Here's the thing about the French data breach that broke in 2025: it's not really one breach. It's actually five breaches merged into one catastrophic database, then dumped on the internet like someone left a filing cabinet unlocked in a parking lot.

When security researchers at Cybernews discovered this massive collection, they weren't looking at scattered records. They found a meticulously organized database containing tens of millions of French citizen profiles, each one cross-referenced with multiple data points from different sources. Full names matched with addresses. Healthcare IDs connected to financial information. Vehicle registrations tied to voter demographic data.

This is the difference between a typical data breach and something far more dangerous: a purpose-built targeting tool.

Most breaches happen because a company got hacked. Someone found a SQL injection vulnerability. Or an employee left credentials in a GitHub repository. Or a cloud database got misconfigured. In those scenarios, you get the data that company possessed—usually one category of information.

But this French breach represents something darker. Someone deliberately collected data from multiple breaches and assembled it into a single, weaponized database. The goal wasn't to expose one company's negligence. It was to create the most valuable targeting resource possible for any criminal willing to buy access.

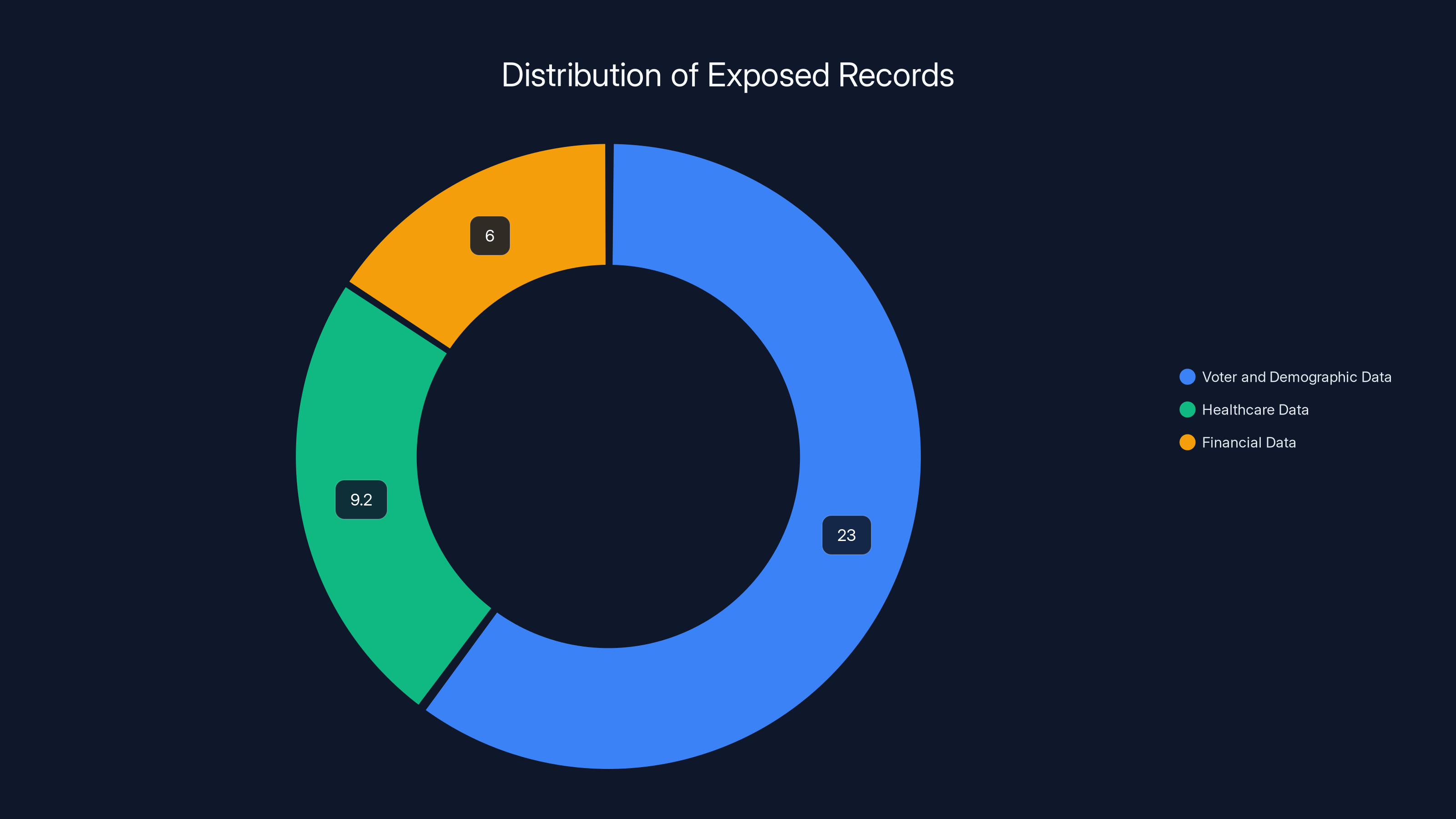

The scale alone is staggering. We're talking about 23 million voter/demographic records, 9.2 million healthcare registry entries, 6 million CRM contact profiles, 6 million financial accounts with banking details, and vehicle registration information for millions more. That's not a breach—that's a comprehensive inventory of French society.

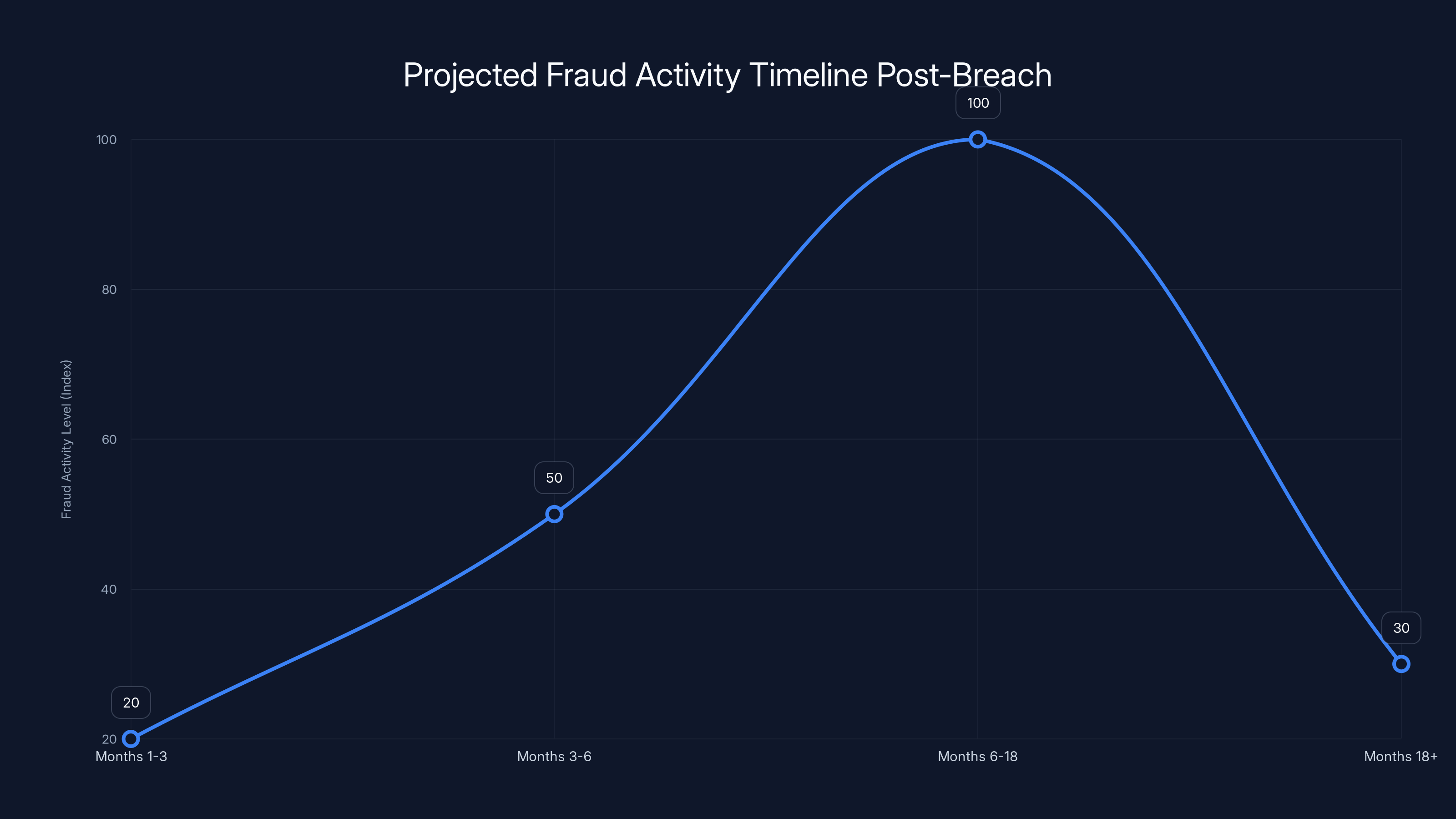

Fraud activity typically peaks between 6-18 months post-breach as data is fully exploited, then declines as security measures improve and data value decreases. Estimated data.

Understanding the Scope: 45 Million Records Explained

When security teams talk about "45 million records," that number needs context because each category of data poses different risks.

The Voter and Demographic Data (23+ Million Records)

The largest chunk of the exposed database consisted of voter registry information. This included full names, residential addresses, and birthdates for over 23 million French citizens. On the surface, this might seem like information already somewhat public—after all, voter registries exist. But there's a critical difference between data being officially recorded and data being compiled into a searchable database by criminals.

This demographic information becomes a targeting foundation for everything else. A criminal knows exactly where someone lives. They know how old someone is. They know someone's full legal name and can cross-reference it with social media profiles. That's the starting point for sophisticated phishing campaigns, social engineering attacks, and physical mail fraud.

The Healthcare Data (9.2 Million Records)

The second-largest dataset came from France's official healthcare registries—specifically the RPPS (Répertoire Partagé des Professionnels de Santé) and ADELI (Automatisation des Listes) databases. These contain detailed professional healthcare information including doctor credentials, specializations, facility affiliations, and contact information.

This isn't personal healthcare records (that would be even worse). But it does reveal which healthcare professionals work where, enabling criminals to impersonate providers or create targeted phishing attacks against specific medical facilities. If you know a specific cardiologist works at a specific hospital, you can craft highly convincing fraud emails appearing to come from that institution.

The Financial Data (6 Million IBANs and BICs)

Perhaps the most immediately dangerous dataset consisted of roughly 6 million financial profiles containing IBAN (International Bank Account Number) and BIC (Bank Identifier Code) information tied to French banks. An IBAN and BIC are essentially the information you'd share to receive a wire transfer—but in the wrong hands, they're also the starting point for fraudulent transfers, unauthorized payments, and account takeovers.

Criminals don't even need to access your account directly. With your IBAN and BIC, they can set up automated payment schemes, claim you authorized transfers, or sell your banking details on criminal marketplaces. The fact that this was combined with demographic data means attackers can social engineer bank employees: "Yes, I'm [Name] and my account number is [IBAN]. I need to dispute this transaction..."

The CRM Contact Data (6 Million Records)

Six million contact records from a CRM database might sound less dramatic than financial information, but these records are pure targeting gold. CRM databases typically contain business contact information, communication history, purchase preferences, and relationship data. Combined with demographic information, this allows criminals to craft hyper-personalized phishing emails.

They won't just send generic "verify your account" emails. They'll send messages that reference your industry, your company size, your previous interactions, making them exponentially more likely to succeed.

Vehicle and Insurance Information

The database also included vehicle registration and insurance information. This enables registration-based identity theft, insurance fraud, and physical targeting (criminals knowing what car someone drives).

How a Criminal Built This Database: The Data Broker Model Explained

Understanding how this breach happened requires understanding how modern data brokers operate. This wasn't random. It wasn't an accident. It was a deliberate, systematic operation.

The Collection Process

Cybercriminals don't typically break into databases one at a time. Instead, they accumulate stolen data over months or years, purchasing records from various sources. Some come from actual company breaches (compromised through ransomware, SQL injection, or insider access). Some come from sold databases on criminal forums. Some come from publicly documented breaches years earlier that were never fully secured.

The individual who built this French database likely spent months collecting records from at least five separate sources. They probably purchased some datasets, received others through criminal networks, and harvested still more from publicly documented breaches. Each individual dataset might have been sitting in a dark web marketplace or shared through encrypted channels.

The Aggregation Strategy

Once you have multiple datasets, the real value comes from linking them. This requires matching records across databases using common identifiers: full name, birthdate, address, phone number, etc.

The criminal took voter records (which have names and addresses), healthcare records (which have names and professional information), financial records (which have account numbers), CRM data (which has contact information), and vehicle registrations (which have address and vehicle details) and merged them into a single searchable database.

This is where sophisticated data analysis comes in. The attacker likely used fuzzy matching algorithms to link records where names might be spelled slightly differently or formatting varied between databases. They might have purchased commercial data-linking services or used custom scripts to automate the process.

The result: a complete profile of millions of French citizens with cross-linked data from five different sectors.

The Storage and Exposure Method

The database was stored on a cloud server in France—likely a legitimate cloud provider where the criminal rented infrastructure under false credentials or through a compromised account. The server was configured with public read access, meaning anyone who found the server could download the entire database.

This is where the exposure becomes particularly reckless (or intentional). The criminal either misconfigured the access settings or deliberately left it exposed to boost the "market value" of the data. When security researchers at Cybernews discovered it, they worked quickly to notify the server owner and help take it offline. But for an unknown period—potentially weeks or months—the database was freely accessible to anyone who knew where to look.

The breach exposed 45 million records, with voter and demographic records being the largest category at 23 million.

The Attack Scenarios This Enables: Real-World Risk Analysis

Why does having this aggregated data matter so much? Because it transforms isolated information into a weapon.

Scenario 1: Hyper-Targeted Phishing at Scale

With names, addresses, birthdates, and financial information, an attacker can send emails like this:

"Hello [Name], we've detected unusual activity on your [Bank Name] account. This afternoon we noticed a transfer attempt from [City Name] at [Time]. If this wasn't you, verify your identity immediately using your IBAN [Real IBAN] to prevent fraud. Click here..."

Every single detail comes from the database. The email looks legitimate because it references real information about the recipient. Banks won't immediately flag it as phishing because the IBAN is real. Most people will click.

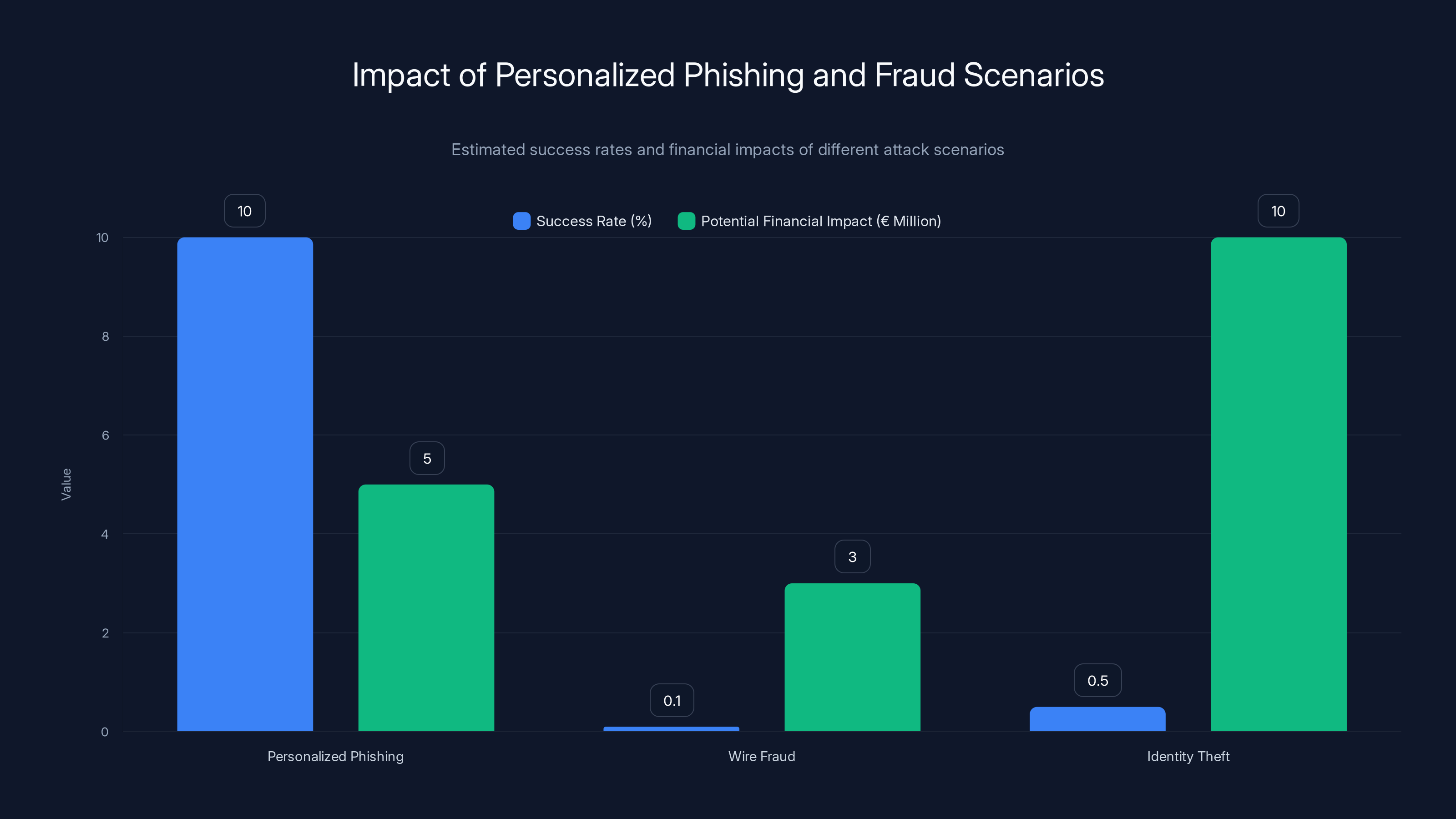

Traditional phishing emails are generic and get caught by filters. This type of targeted phishing bypasses security because it's personalized with real data. Studies show that personalized phishing emails have click rates 5-10 times higher than generic campaigns.

Scenario 2: Wire Fraud and Unauthorized Transfers

With IBAN and BIC information, criminals can:

- Impersonate legitimate payment collection services

- Set up false invoices that appear to come from government agencies

- Commit business email compromise fraud using stolen CRM data

- Create automated payment schemes that appear authorized

A single successful wire fraud might be €500. Scaled across 6 million financial records with even a 0.1% success rate? That's €3 million in fraud.

Scenario 3: Identity Theft with Complete Personal Profiles

With demographic data, healthcare information, financial details, and vehicle registration, criminals have everything needed to:

- Open accounts in someone's name

- Apply for loans

- Commit tax fraud

- Impersonate someone in legal documents

- Create synthetic identities using real information

Identity theft typically takes months to discover. By the time a victim realizes their identity was stolen, thousands of euros in fraudulent charges may have accumulated.

Scenario 4: Insurance Fraud and Claims Manipulation

Knowing someone's vehicle registration and insurance information, criminals can:

- File false insurance claims

- Steal vehicle information for fraud

- Commit staged accident insurance schemes

- Target high-value vehicle owners for robbery or extortion

Scenario 5: Targeted Social Engineering and Extortion

With professional healthcare information and CRM data, criminals know exactly who works where and can:

- Social engineer employees into revealing credentials

- Create convincing pretexting scenarios

- Conduct business account takeovers

- Impersonate executives or IT support

Timeline: When This Happened and Why Detection Was So Difficult

The timeline of this breach illustrates a critical problem in modern data security: attribution and detection delays.

The Collection Phase (Months/Years Before Discovery)

The original breaches that fed this database likely occurred at different times. Some might date back 2-3 years. Some might be recent. The criminal gradually accumulated them, possibly through:

- Purchasing from other criminals who had data to sell

- Accessing criminal forums where datasets are shared

- Harvesting from publicly documented breaches

- Maintaining access to compromised systems

During this phase, no single organization realized their data was being aggregated with others. Each company saw their own breach as isolated.

The Aggregation and Upload Phase (Unknown Timeline)

At some point, the criminal completed the merging process and uploaded the combined database to a cloud server. This likely happened within weeks of the discovery, but we don't know for certain. The database might have been accessible for months before anyone found it.

This is the most dangerous phase because the data is exposed but no one knows it exists. No automated security monitoring catches it because the attacker isn't targeting any specific system—they're just hosting a file.

The Discovery Phase (Late 2024/Early 2025)

Security researchers at Cybernews discovered the exposed database through their monitoring infrastructure. They immediately worked to notify the server owner and helped secure it. They also began analyzing the data to understand its scope and source.

The speed of Cybernews's response prevented wider distribution, but the database had already been exposed for an unknown period.

The Challenge: Why This Took So Long to Find

Unlike typical data breaches that generate network alerts or are discovered through security audits, this exposure had no automatic detection mechanism. The database was:

- Hosted on a legitimate cloud provider (not obviously suspicious)

- Configured with open permissions (but not obviously monitored)

- Not connected to any specific company's security infrastructure

- Discovered through ongoing security research, not through incident response

This is the difference between reactive security (detecting breaches against your systems) and proactive security research (actively searching for exposed databases). Most organizations only do the former.

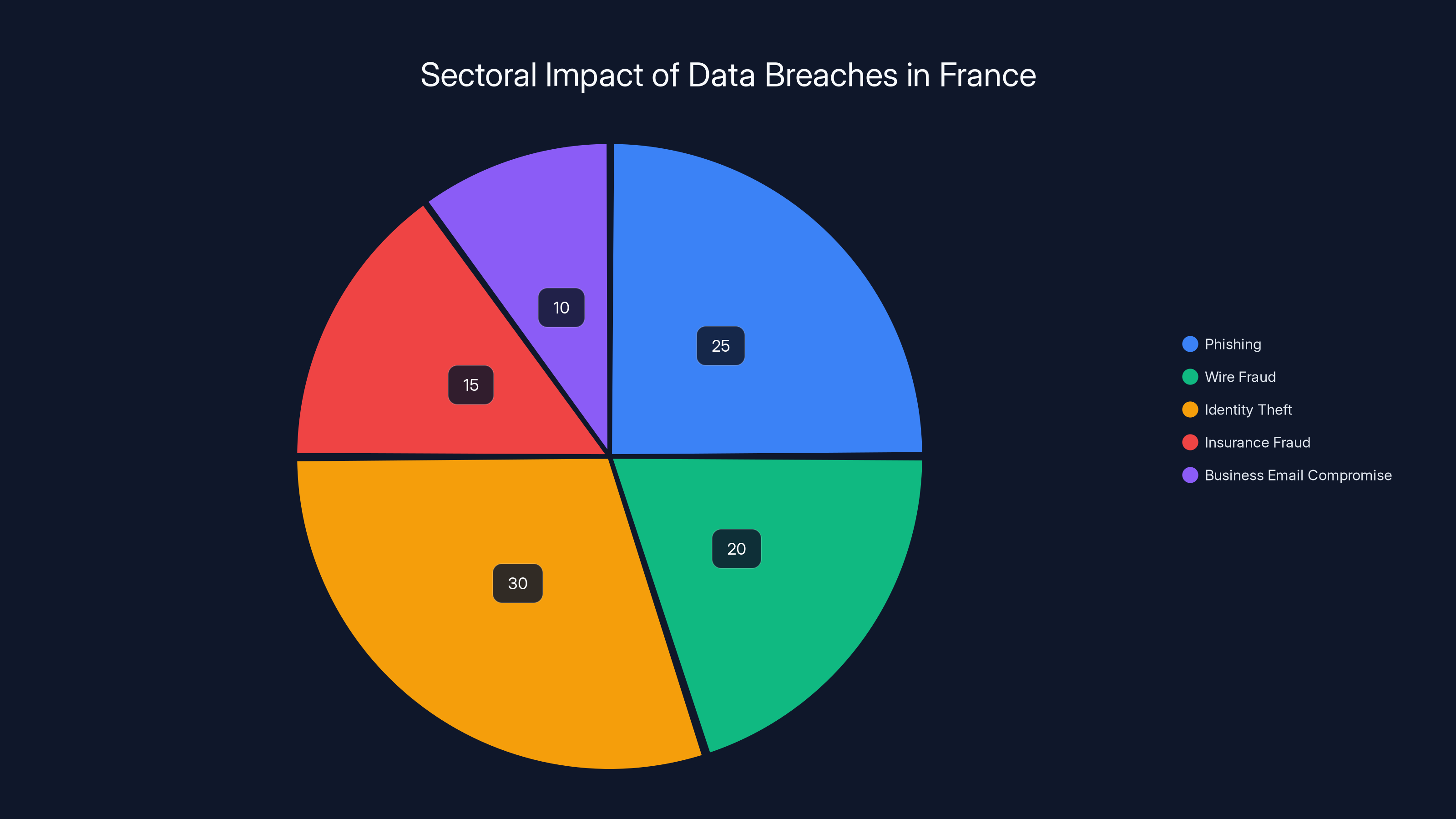

Estimated data shows identity theft as the most prevalent use of compromised data in France, followed by phishing and wire fraud. Estimated data.

Geographic and Sectoral Impact: Why France and Why Now?

Why France Was Targeted

France represents a high-value target for data aggregators for several reasons:

- Strong regulatory environment: France's strict data protection laws mean companies are more likely to have documented breaches publicly, providing a roadmap for criminals.

- Wealthy population: French citizens have higher average incomes and banking activity, making fraud more profitable.

- Digital infrastructure: France has well-developed healthcare, financial, and government digital systems that have been breached multiple times.

- GDPR visibility: European GDPR breaches are publicly reported and analyzed, allowing criminals to identify compromised databases.

The Multi-Sector Approach

A sophisticated criminal targeting only one sector (just healthcare, or just financial) would have limited value. But by combining voter data, healthcare registries, financial information, CRM data, and vehicle registration, the attacker created a database valuable to multiple criminal specialties:

- Phishing specialists: Use the demographic and contact data.

- Wire fraud operators: Use the financial and IBAN data.

- Identity thieves: Use the complete profiles.

- Insurance fraudsters: Use the vehicle and demographic data.

- Business email compromise teams: Use the CRM and professional data.

One database, sold to multiple criminal buyer groups, each using different aspects.

Technical Analysis: How the Database Was Structured and What That Means

Database Schema and Organization

The way the criminal organized this database reveals their sophistication level.

Instead of just dumping raw records, they created a structured database with clear tables for each data category. Each person had a unique identifier that linked across tables. This isn't how haphazardly stolen data typically looks—this is how a professional database administrator would organize information.

The structure probably looked something like:

- PERSONS TABLE: Demographic data (name, address, birthdate, phone, email)

- HEALTHCARE TABLE: RPPS/ADELI registry information linked by name and professional ID

- FINANCIAL TABLE: IBAN, BIC, and bank account information linked by name and address

- CRM TABLE: Contact records and interaction history linked by contact information

- VEHICLE TABLE: Vehicle registration and insurance information linked by address

Each person's record could be queried to pull complete profiles across all categories.

Data Quality and Verification

Cybernews researchers verified the database's authenticity by:

- Cross-referencing with known breaches: Confirming that records matched publicly known healthcare and voter data breaches.

- Validating IBAN structure: Confirming that financial IBANs followed proper French banking format (IBAN starts with FR for France).

- Checking for plausible patterns: Confirming that geographic, age, and name distributions matched actual French demographics.

- Verifying against official registries: Spot-checking records against official French government and healthcare databases.

The data was consistent, well-formatted, and clearly authentic.

Storage Method and Security Misconfiguration

The database was stored on a cloud server (likely AWS, Azure, or Google Cloud based on the infrastructure patterns) with a public S3 bucket or similar configuration. The misconfiguration was simple but catastrophic: the storage was readable by anyone with the URL.

This is such a common configuration mistake that cloud providers now include extensive warnings. But enforcement varies, and criminals specifically look for misconfigured buckets because the data inside is usually intact and complete.

The largest portion of the 45 million exposed records is voter and demographic data, comprising over 23 million records. Healthcare data and financial data account for 9.2 million and 6 million records, respectively.

The Dark Web Connection: How This Data Gets Monetized

Criminal Marketplace Ecosystems

Once a database like this is compiled, it doesn't stay hidden. It enters criminal marketplaces where it's valued, traded, and sold.

The dark web has specialized markets for personal data:

- Genesis Market and similar sites: Specialized in personal profile data for targeted fraud.

- Underground forums: Where bulk personal data is auctioned to the highest bidder.

- Direct sales channels: Where the original aggregator sells subscriptions to access the database.

- Data broker brokers: Middlemen who purchase bulk data and resell to specialists.

Pricing Models

A database of this size and quality typically commands high prices:

- Complete profiles (all data categories for one person): 50 each.

- Sector-specific data (just healthcare, or just financial): 0.50 per record.

- Full database access (subscription or one-time purchase): 50,000+.

- Search/query subscriptions: 2,000 per month for unlimited lookups.

Even at conservative 1% utilization rates, this database represents hundreds of thousands of dollars in criminal value.

The Buyer Network

Who purchases this data?

- Phishing specialists: Buying full profiles for targeted campaigns.

- Romance scammers: Buying demographic data for victim targeting.

- Wire fraud teams: Buying financial data and IBAN information.

- Identity theft rings: Buying complete profiles for account creation.

- Insurance fraudsters: Buying vehicle registration data.

- Corporate espionage actors: Buying CRM data for competitive intelligence.

Each buyer represents a different criminal specialization, but they all target the same victims—French citizens whose information was aggregated and sold.

Individual Risk Assessment: Are You Actually Affected?

High-Risk Groups

Certain groups face elevated risk from this breach:

- French citizens with French bank accounts: The financial data poses direct wire fraud risk.

- French healthcare professionals: The healthcare registry data enables impersonation.

- Business owners and executives: CRM data enables targeted business fraud.

- Vehicle owners: Vehicle registration data enables auto fraud and targeting.

- Anyone with voter registration: Demographic data enables broad targeting.

Medium-Risk Groups

- French expatriates: May have French healthcare records or bank accounts.

- Frequent visitors to France: Might have French vehicle registration or healthcare records.

- People with French family connections: Family members in France might be referenced.

Lower-Risk Groups

- Non-French citizens with no French records: If your information isn't in the source breaches, it's not in the aggregated database.

- People who never used French financial or healthcare services: Limited exposure to the most damaging data categories.

What Actually Being "Affected" Means

Importantly, "being in the database" doesn't automatically mean fraud will occur. It means your information is available to criminals who might attempt fraud. The actual risk depends on:

- Whether criminals target you specifically.

- Whether your bank, insurance, or other institutions catch fraud attempts.

- Whether you have fraud monitoring enabled.

- Your alertness to suspicious communications.

Personalized phishing can have a success rate up to 10%, leading to significant financial impacts. Wire fraud, even with a low success rate, can yield millions due to the volume of records. Identity theft, though less frequent, can have severe financial consequences. Estimated data based on typical scenarios.

Immediate Actions: What You Should Do Right Now

Within 24 Hours

-

Check French government breach notification resources: While this breach is documented in security research, official French government notification processes vary. Check with French data protection authorities.

-

Change all French financial and government account passwords: Don't do this from public Wi-Fi. Use only secure, private networks.

-

Enable fraud alerts with your French banks: Call your bank directly (using numbers you find independently, not from any email/letter) and request fraud alerts.

-

Document everything: Take screenshots of any suspicious communications and save them.

Within One Week

-

Set up multi-factor authentication everywhere: French banks, government portals, email accounts—every service that allows it.

-

Enable transaction notifications: Set alerts for any account activity, even small amounts.

-

Request a free credit report: If your country has a credit reporting system (France has Equifax, CNIL), check for suspicious inquiries or new accounts.

-

Monitor for unsolicited mail: Watch for unexpected bills, tax notices, or account statements you didn't request.

Within One Month

-

Consider a credit freeze: Prevents new accounts from being opened in your name without unfreezing. More powerful than fraud alerts.

-

Review insurance policies: Contact your insurers (health, vehicle, home) and flag your account for fraud monitoring.

-

Register for identity theft protection services: Many offer monitoring and recovery assistance if fraud occurs.

-

File a police report: If you're a French citizen, file a report (plainte) documenting the breach. This creates an official record if fraud occurs.

Ongoing (Next 2-3 Years)

-

Check credit/financial reports quarterly: More frequent than typical, specifically looking for unfamiliar accounts or inquiries.

-

Monitor for wire fraud: Check your banking apps regularly for unauthorized transfers or payment setups.

-

Verify all financial statements: Review bank statements, investment accounts, and credit card statements in detail.

-

Be extremely cautious of unsolicited communications: Any email, text, or call referencing your bank or government services should be treated as suspect.

Regulatory Response and Government Actions

French Data Protection Authorities

France's CNIL (Commission Nationale de l'Informatique et des Libertés) is responsible for investigating data breaches and enforcing GDPR penalties. Their response to this breach includes:

- Investigation into source breaches: Determining which organizations were originally compromised.

- Notification requirements: Determining if organizations must notify individuals under GDPR.

- Potential penalties: GDPR violations can result in fines up to €20 million or 4% of global revenue.

- Remediation requirements: Organizations may be required to implement security improvements.

Government Sector Response

Because this breach includes voter registry data and government database information, French government cybersecurity agencies (like ANSSI - Agence Nationale de la Sécurité des Systèmes d'Information) are also involved:

- Critical infrastructure assessment: Evaluating if government systems were compromised.

- Election security review: Assessing if voter data exposure poses risks to election integrity.

- Incident coordination: Working with international partners to trace the attacker.

International Coordination

Because the server was hosted internationally and the attacker may be outside France, international law enforcement is involved:

- Europol and Interpol: Investigating cross-border aspects.

- International cybercrime task forces: Coordinating with other countries.

- Extradition considerations: If the attacker is identified and located in another country.

Limitations of Regulatory Response

Importantly, regulatory action is slow. Even if the attacker is identified and prosecuted, it might take years. GDPR penalties are imposed on organizations, not criminals. And most victims never receive direct compensation—they're left to handle fraud individually.

Prevention Framework: How Organizations Should Have Stopped This

Data Breach Prevention at Source

The fundamental problem is that none of the five original breaches should have happened. If each organization had better security:

- Voter databases: Should be air-gapped and encrypted, with zero internet access.

- Healthcare registries: Should require VPN access and multi-factor authentication.

- Financial systems: Should have transaction monitoring and anomaly detection.

- CRM systems: Should log all access and flag bulk exports.

- Vehicle registration: Should require authorization for large exports.

Each individual breach represents a failure in data security.

Preventing Data Aggregation After Breach

Even if breaches occur, preventing their aggregation requires:

- Breach notification: Public disclosure of breaches (GDPR requires this) alerts victims but also helps identify stolen data.

- Data linking prevention: Making records harder to match across datasets through anonymization or encryption.

- Monitoring for aggregation: Searching dark web and criminal markets for suspicious data sales.

- Legal consequences for buyers: Criminalizing the purchase and resale of stolen data.

Cloud Infrastructure Security

The fact that this database was exposed on public cloud infrastructure points to:

- Cloud configuration failures: S3 buckets and similar storage should never be publicly readable.

- Access control improvements: Cloud providers should require more explicit authorization for public sharing.

- Continuous monitoring: Cloud providers should scan for obviously misconfigured storage.

- Notification systems: Users should be immediately alerted when public access is detected.

Most major cloud providers have implemented improvements, but enforcement remains inconsistent.

Long-Term Consequences: What Happens Next?

The Immediate Fraud Wave

Historically, large data breaches see fraud waves in the 6-18 months following discovery. This breach will likely follow that pattern:

- Months 1-3: Criminals verify the data quality by testing small transactions and phishing attempts.

- Months 3-6: Organized fraud rings begin large-scale deployment once data is confirmed reliable.

- Months 6-18: Peak fraud activity as multiple criminal groups utilize the data.

- Months 18+: Gradual decline as victims secure accounts and data becomes less valuable.

Market Impact

The availability of this aggregated data affects:

- Fraud services market: Increases supply of viable leads for phishing and wire fraud.

- Data broker pricing: Makes similar aggregated datasets more valuable.

- Criminal job markets: Creates demand for specialized fraud operators and money launderers.

- Financial institution costs: Banks will spend millions on fraud prevention and customer remediation.

Copycat Attacks

When one criminal successfully creates an aggregated database, others inevitably copy the technique. We can expect:

- German data aggregation: Similar breach aggregation targeting German citizen records.

- Spanish data aggregation: Aggregated breaches targeting Spanish residents.

- Multi-country databases: Aggregated databases spanning multiple European nations.

- Sector-specific aggregation: Healthcare data from multiple countries merged into one database.

Regulatory Evolution

This breach will likely catalyze new regulations:

- Data aggregation criminalization: Explicit laws making it illegal to knowingly combine stolen datasets.

- Cloud security mandates: Regulations requiring cloud providers to prevent public storage exposure.

- Breach notification acceleration: Faster notification requirements to prevent aggregation.

- International coordination: Treaties enabling faster investigation and prosecution of data brokers.

How to Protect Against Future Data Aggregation Attacks

Personal-Level Protections

While you can't prevent your data from being breached, you can reduce its value to criminals:

- Data minimization: Provide less information to organizations. Use privacy-focused settings everywhere.

- Unique passwords: Never reuse passwords. If one service is breached, limit exposure to other accounts.

- Alternative identities: Consider using different email addresses for different services. One email compromised doesn't compromise all accounts.

- Regular monitoring: Check credit, financial accounts, and personal records at least quarterly.

- Privacy by default: Opt out of data sharing, marketing lists, and data broker access everywhere possible.

Organizational-Level Protections

If you work for an organization handling personal data:

- Encrypt sensitive data: Data at rest and in transit should be encrypted. If encryption fails, data remains protected.

- Principle of least privilege: Employees only access data they need. Limit bulk export capability.

- Audit logging: Record all data access and exports. Unusual patterns trigger alerts.

- Segmentation: Keep sensitive data separated from general systems. Air-gap critical databases.

- Access controls: Require multi-factor authentication and VPN for sensitive data access.

- Retention limits: Delete data that's no longer needed. Less data = less to breach.

- Vendor assessment: If using third-party services, audit their security practices. Breaches by vendors affect you.

- Incident response planning: Have detailed procedures for breach response, notification, and victim assistance.

Technical Protections

- Password managers: Enable unique passwords for every service without memorization burden.

- FIDO2 hardware keys: Provide protection against phishing that can't be replicated in emails.

- VPN services: Mask your location and encrypt traffic when accessing services from untrusted networks.

- Email filtering: Advanced filters catch phishing emails before they reach your inbox.

- Phone number verification: Don't share your phone number widely; criminals can use it for SIM swapping and account recovery.

- Privacy browsers and tools: Use privacy-focused browsers, tracker blockers, and fingerprint protection.

Behavioral Protections

- Extreme skepticism: Assume every unsolicited communication is phishing until proven otherwise.

- Verification protocols: Never click links in suspicious emails. Always navigate to websites independently.

- Social engineering awareness: Understand common pretexting techniques so you recognize them.

- Information compartmentalization: Don't reveal personal details even in seemingly innocent conversations.

- Privacy hygiene: Assume nothing you share online is private—share accordingly.

FAQ

What exactly was exposed in the French data breach?

The breach exposed approximately 45 million records aggregated from at least five separate data sources. This includes over 23 million voter and demographic records with full names and addresses, 9.2 million healthcare professional registry entries, 6 million CRM contact records, 6 million financial profiles with IBANs and banking information, and vehicle registration and insurance data. Each person's records were cross-linked across these datasets, creating complete profiles that criminals can use for targeted fraud.

How did a criminal manage to combine data from five different breaches?

The criminal used data matching and linkage techniques to connect records across datasets using common identifiers like full names, birthdates, addresses, and phone numbers. They likely purchased some datasets from criminal marketplaces, received others through criminal networks, and collected still more from public documentation of historical breaches. Once collected, they structured everything into a single organized database with cross-referenced records, creating one unified targeting tool instead of five disconnected datasets.

Should I be concerned even if I'm not French?

If you have accounts with French banks, French healthcare services, French vehicle registration, or any records in French government systems, you should be concerned. If you're a French citizen living abroad, even more so. If you have no French connections whatsoever, your immediate risk from this specific breach is minimal. However, the techniques used to aggregate this database are being replicated against other countries, so consider whether similar aggregation has happened in your country.

How do I know if my information is in the breached database?

There's no convenient way to check without attempting to access the exposed database (which you shouldn't do). Your best approach is to assume it's been compromised if you have any French records. Monitor your financial accounts, credit reports, and government records for fraudulent activity. If you notice suspicious accounts, unauthorized transactions, or unexpected communications, assume your information was in the breach and take action immediately.

What's the difference between fraud alerts and credit freezes?

Fraud alerts notify creditors to verify your identity before opening new accounts, making fraud harder but not impossible. A credit freeze completely prevents new accounts from being opened in your name without your explicit authorization. Fraud alerts are free and temporary (usually last 1 year). Credit freezes are free or low-cost but require you to unfreeze your credit when you actually want to apply for new accounts. For this breach, a credit freeze is more effective.

How long will this breach continue to cause damage?

Historically, large-scale personal data breaches generate significant fraud for 12-18 months after public discovery, with lower levels of fraud continuing for 3-5 years. This breach will likely follow that pattern, with a fraud wave peaking 6-12 months after discovery as criminal groups systematically utilize the aggregated data. Long-term risks (identity theft, fraudulent loans) can persist for years. Continued vigilance is necessary for at least 3 years.

What should I do if I discover fraudulent accounts in my name?

Immediately contact the financial institution or service where the fraud occurred. File a police report (plainte) documenting the fraud. Contact the three major credit reporting agencies in France (Equifax, Experian, CNIL) to place a dispute notice on your credit file. Document everything. If wire fraud is involved, report it to your bank's fraud department. Consider hiring identity theft recovery services if the fraud is extensive.

Can criminals use my IBAN and BIC to steal money from my account?

With your IBAN and BIC, criminals can set up transfers to accounts they control, claim you authorized payments, or attempt fraudulent schemes. However, they can't directly access your account without your login credentials. IBAN and BIC are information you normally share to receive payments, so they alone don't enable account takeover. But combined with other data from the breach, they enable sophisticated fraud. Enable transaction notifications with your bank to catch suspicious activity immediately.

How can organizations prevent similar aggregation breaches in the future?

Organizations can reduce risk by: encrypting sensitive data at rest and in transit, implementing multi-factor authentication for all data access, segmenting critical databases from general systems, limiting bulk data exports, maintaining detailed audit logs of all data access, deleting data no longer needed, and implementing strict access controls. At a systemic level, criminalizing data aggregation, improving breach notification speed, and cloud provider improvements to prevent misconfiguration would help prevent this type of attack.

Is the criminal who created this database likely to be caught?

Identifying and prosecuting the criminal is extremely difficult. They likely used VPNs and possibly compromised accounts to host the database. They may be located outside France in a country with weak extradition treaties. They used sophisticated techniques to aggregate and organize data. Law enforcement is investigating, but prosecution could take years or may never happen. Meanwhile, the data has already been distributed to other criminals. Focus on personal protection rather than expecting criminal justice.

What makes this breach different from typical data breaches?

Most breaches involve one organization being compromised and losing the data they possessed. This breach is fundamentally different because it was deliberately assembled by a criminal specifically to maximize its criminal value. Instead of accidental exposure, this represents intentional aggregation and distribution. The attacker wasn't targeting any specific organization—they were building a tool for themselves and other criminals. This requires more sophisticated technical skills and represents a more dangerous model of data crime.

Conclusion: The Future of Data Security in a Post-Aggregation World

The French data breach of 45 million records marks a troubling shift in how cybercriminals operate. It's no longer enough to secure your data against breaches from external attackers. Now we must also consider the risk that your data, combined with data breached from other organizations, will be weaponized against you by criminals who operate on an entirely different level.

The criminal or criminals behind this aggregation displayed genuine sophistication. They didn't just steal data and sell it. They recognized that five disconnected datasets had limited value, but the same five datasets merged and cross-linked would be worth exponentially more. They invested time in matching records across systems, organizing everything into a searchable database, and hosting it in a way that made it accessible to their customers.

This is data crime as a business model. Organized, systematic, and devastatingly effective.

What's particularly concerning is that this technique is easily replicable. Other criminals, having seen this succeed, will apply the same approach to other countries. We'll likely see German citizen databases aggregated. Spanish records compiled. Polish information merged. Each one leveraging the same proven technique.

The regulatory response will be slow. Laws will eventually catch up—making aggregation explicitly illegal, imposing harsher penalties, creating international cooperation mechanisms. But regulation won't prevent this breach or the next dozen like it. The data's already out there.

Your protection has to be personal. Assume your data has been breached. Assume it's been combined with data from other breaches. Assume criminals have complete profiles of you and are actively deciding whether targeting you would be profitable.

Change every password. Enable every authentication method. Monitor every account. Question every unexpected communication. Treat every link as dangerous. Because in the post-aggregation era of data crime, they probably are.

The massive French breach isn't the end of this story. It's barely the beginning. And the only defense you have is personal vigilance. Start now. Don't wait for official notification—it might never come. Don't assume you'll be fine if no fraud has occurred yet—give the criminals time. They're just getting started.

Your data is out there. What you do now determines whether criminals can actually use it against you. That's the real lesson of the 45 million exposed French records. Personal responsibility isn't optional anymore. It's your only reliable defense.

Key Takeaways

- 45 million French records were deliberately aggregated from five separate breaches into one weaponized database by a criminal data broker, not exposed through a single organization failure.

- The aggregation includes voter data, healthcare registries, financial IBANs, CRM contacts, and vehicle registration—creating complete cross-linked profiles enabling targeted phishing, wire fraud, and identity theft.

- Criminals will likely monetize this data through dark web marketplaces, with complete profiles worth $20-50 each and subscription access potentially valued at tens of thousands of dollars.

- Fraud waves following data breaches typically peak 6-12 months after discovery as criminal groups systematically deploy aggregated data, requiring 2-3 years of heightened vigilance.

- Immediate protective actions include password changes, multi-factor authentication setup, credit freezes, fraud monitoring, and quarterly financial account reviews to catch fraud before substantial damage occurs.

Related Articles

- Illinois Data Breach Exposes 700,000: How Government Failed [2025]

- Tea App's Comeback: Privacy, AI, and Dating Safety [2025]

- RedDVS Phishing Platform Takedown: How Microsoft Stopped a $40M Cybercrime Operation [2025]

- ExpressVPN 78% Discount Deal: Complete Savings & Comparison Guide [2025]

- Fitness Apps Privacy Guide: How to Stop Data-Hungry Apps [2025]

- UK Scraps Digital ID Requirement for Workers [2025]

![45 Million French Records Leaked: What Happened & How to Protect Yourself [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/45-million-french-records-leaked-what-happened-how-to-protec/image-1-1768484218110.jpg)