Tea App's Comeback: Privacy, AI, and Dating Safety [2025]

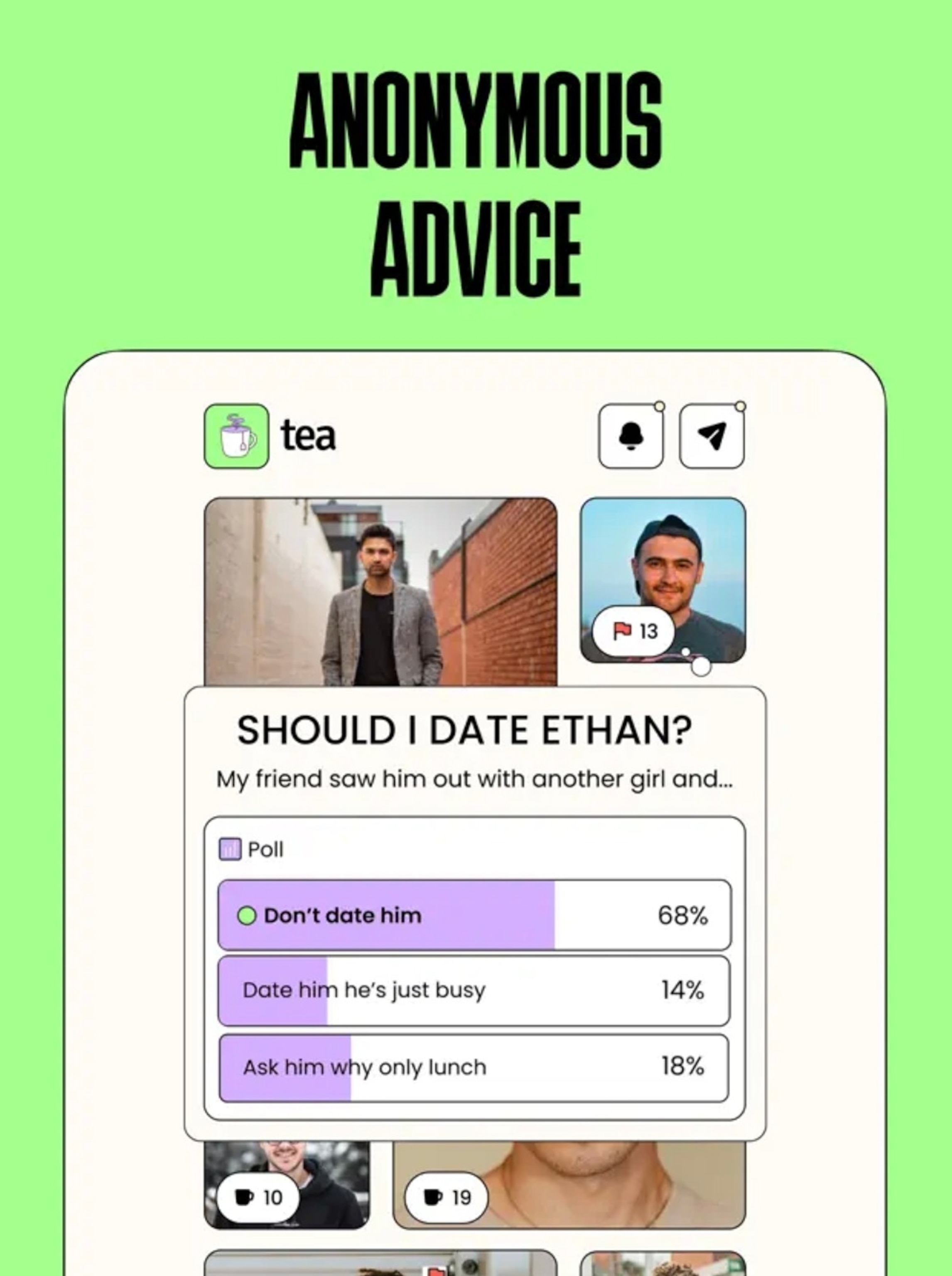

Last summer, an app called Tea went from zero to number one on the iOS App Store in weeks. The concept was simple but potent: women could anonymously post Yelp-style reviews of men, flagging red flags like infidelity, financial instability, or criminal records. It solved a real problem that dating apps ignored—the lack of transparent community-driven safety warnings.

Then it all fell apart.

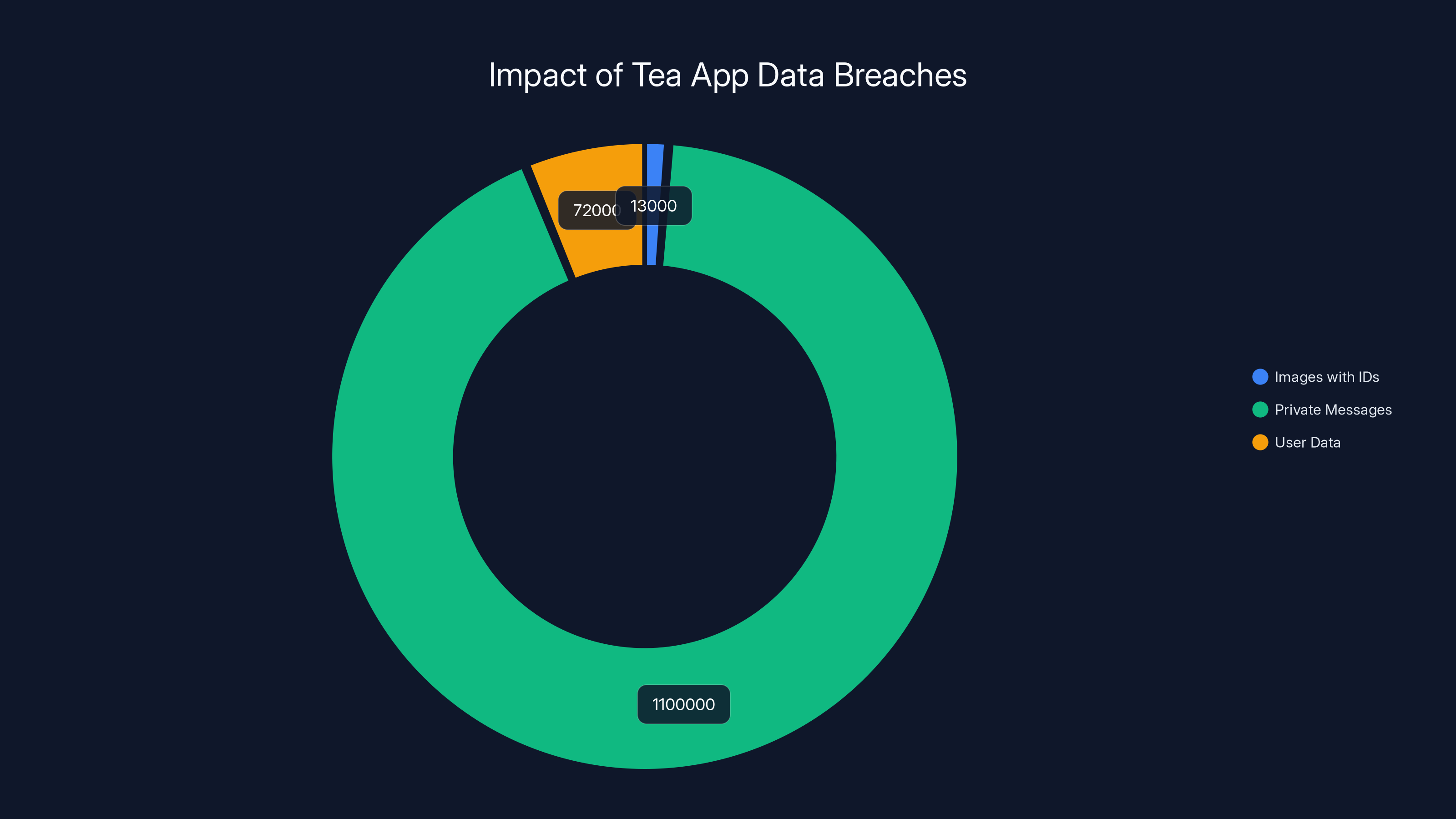

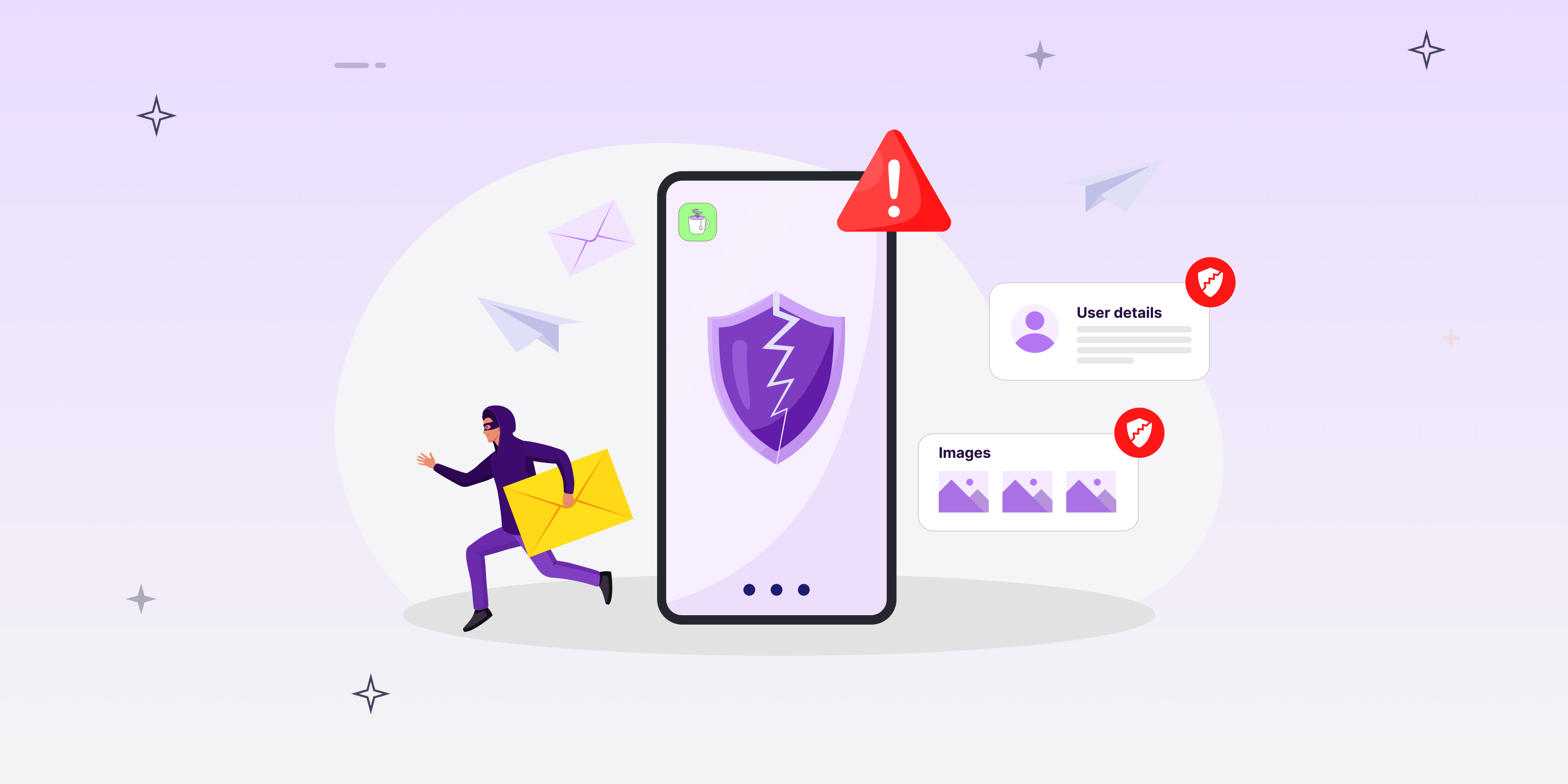

In July, hackers breached Tea's servers twice in rapid succession. The first breach exposed 72,000 images including driver's licenses, selfies, home addresses, and intimate messages. Days later, a second breach hit 1.1 million users, leaking conversations about abortion, infidelity, and phone numbers. Some photos ended up on Reddit and 4Chan. Apple yanked the app from the App Store. Lawsuits piled up.

Now Tea is back. With a new website. New AI features. Government ID verification. And claims of better security.

But here's the uncomfortable truth: security theater and actual security are two very different things. A new website doesn't erase the fact that Tea stores the most sensitive data imaginable—women's safety concerns about specific men, photos, addresses, and intimate details. Even with improvements, that's a target painted in neon.

Let's dig into what Tea actually changed, what risks remain, and whether the company's comeback strategy makes sense for the millions of women who need dating safety tools that don't put them at further risk.

TL; DR

- Two massive breaches in July: 72,000 images in breach one, then 1.1M users hit days later, exposing photos, IDs, addresses, and intimate messages

- New security features: Government ID verification via third-party vendor, penetration testing, enterprise-grade backend controls, and tighter access controls

- AI safety tools on Android: Red Flag Radar AI coming soon, in-app dating coach active now, designed to supplement community warnings

- Website launch, not iOS return: Apple hasn't reinstated the app, so iOS users are out; Android app added new features

- Lawsuit exposure: 10+ class action lawsuits pending for negligence, breach of implied contract, and failure to secure personal data

- Bottom line: Tea addressed some real vulnerabilities but storing this much sensitive data about women remains inherently risky, no matter how good the encryption is

The Tea app data breaches exposed 13,000 images with IDs, 1.1 million private messages, and 72,000 user data records, highlighting significant privacy concerns.

What Happened to Tea: A Timeline of Disaster

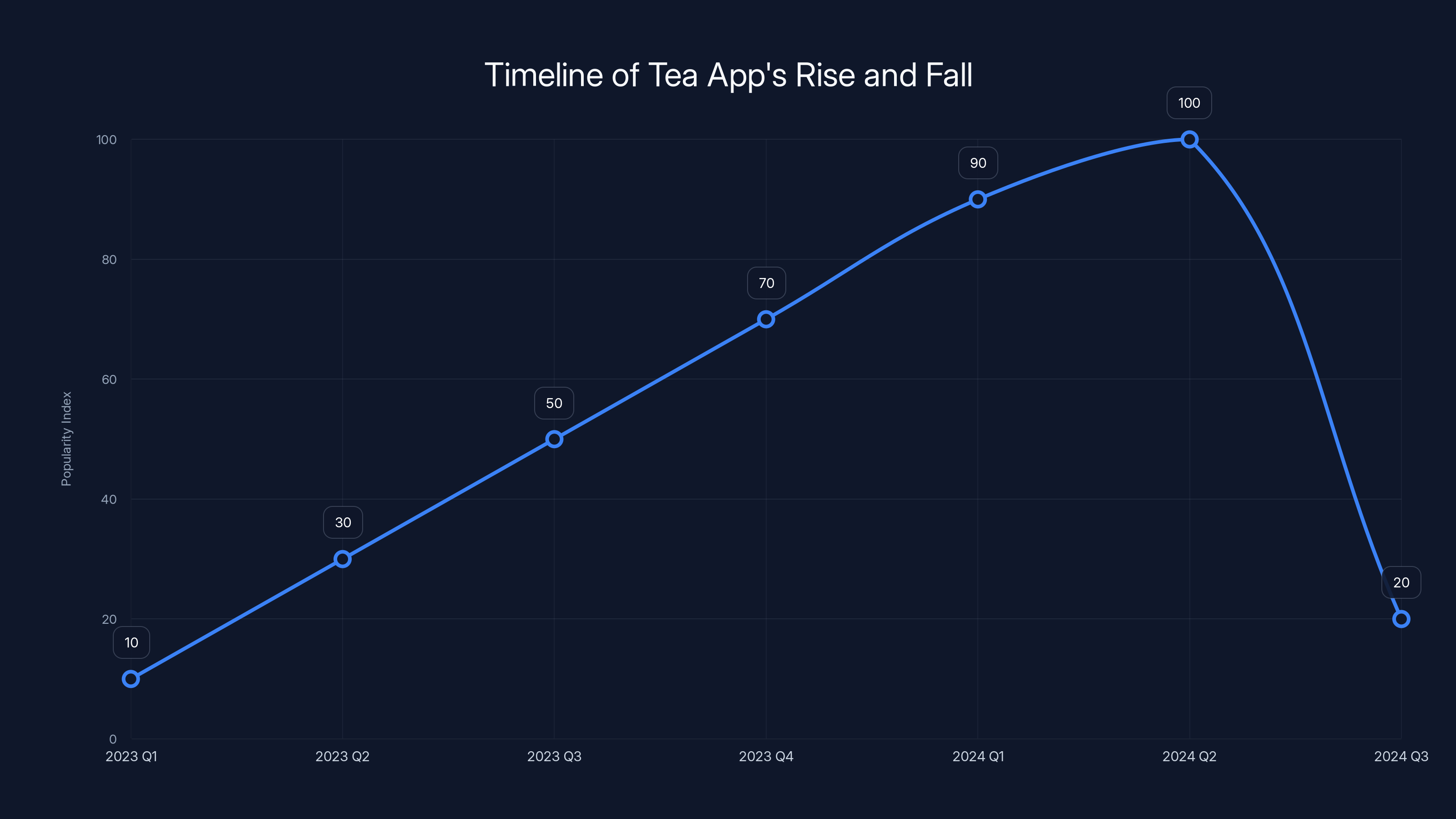

Tea's rise was meteoric. Launched in 2023 by Sean Cook after his mother was catfished during online dating, the app filled a gap in the dating app ecosystem. Dating apps like Tinder, Bumble, and Hinge focused on matching and connecting. Tea focused on warning—collectively identifying men who were liars, cheaters, or criminals.

The community aspect was essential. Women could post photos of men, add context about red flags, and comment on other women's posts. If multiple women flagged the same person, a pattern emerged. This crowdsourced approach to safety made sense in a world where men could create fake profiles, hide relationship status, or present false information with zero accountability.

By summer 2024, Tea hit number one on the iOS App Store. Millions downloaded it. The app was generating real conversations about online dating safety, privacy, and the risk women face.

Then on July 25, 404 Media broke the news: Tea had been hacked.

The details were horrifying. Attackers accessed 72,000 images from photos, comments, and direct messages. But this wasn't a credit card database or anonymous user profiles. This was personal identification documents, home addresses, and intimate conversations about infidelity, sexual trauma, and abortion discussions. Some images were already circulating on Reddit and 4Chan.

Then, days later, 404 Media reported breach number two: 1.1 million users affected. More messages leaked. More phone numbers exposed. More of women's safety concerns weaponized.

Apple removed Tea from the App Store, citing policy violations and privacy concerns. A rival app called Tea On Her (a male version where men post about women) was also removed. Within weeks, Tea faced 10+ class action lawsuits across federal and state courts, with women alleging breach of implied contract and negligence in data security.

For anyone paying attention, the message was clear: storing this much sensitive data about women's dating experiences was a liability time bomb.

Understanding the Data Breach Impact

Most app security breaches are annoying. Your Netflix password gets leaked. Your email address ends up on spam lists. But Tea's breach was different in kind, not just degree.

Consider what the leaked data actually contained. Not abstract information, but the lived experiences of women using a dating app. Their warnings about specific men—"He told me he was single but he's married." "He's on the sex offender registry." "He pressured me for nudes."

Now imagine that woman's home address, her government ID, her phone number, and her full conversation history are linked to her warning. An aggrieved man who read his own negative reviews could easily cross-reference that data to identify the women who posted about him.

The second breach made this worse by exposing the content of private messages between women discussing abuse, assault, abortion access, and other deeply personal topics. This wasn't just a privacy violation—it was a safety violation that could enable harassment, doxxing, or worse.

What made it worse was the company's initial response. The breaches weren't the result of a sophisticated zero-day attack exploiting an obscure vulnerability. They were described as preventable failures in access control, data isolation, and basic security hygiene. In other words, Tea knew how to prevent this. They just didn't.

Security researcher Jonathan Leitschuh told WIRED that "websites are equally as vulnerable to harm as apps," meaning shifting to a web-based model doesn't automatically solve the security problem. The vulnerability lived in the business logic and data architecture, not the platform.

Tea app saw a rapid rise in popularity, reaching its peak in mid-2024 before a significant drop following major data breaches. (Estimated data)

The New Security Model: What Tea Actually Changed

So what did Tea do differently? According to Jessica Dees, the company's head of trust and safety, they implemented several categories of improvements: tighter internal safeguards, reinforced access controls, expanded review and monitoring processes, and ongoing penetration testing.

Let's break down what each of these means and whether they actually address the root causes of the breach.

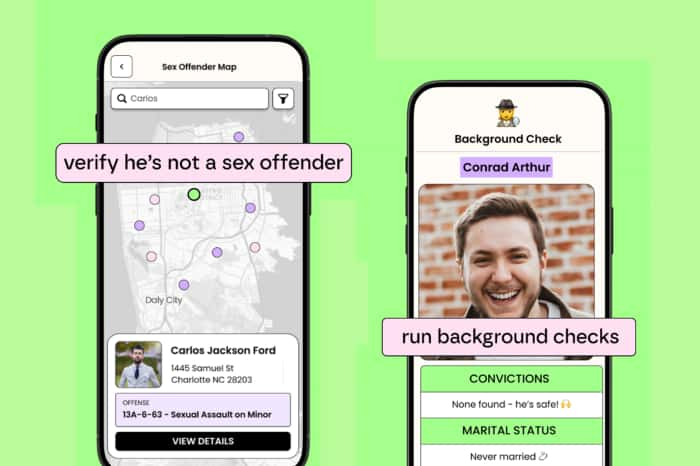

Third-Party Identity Verification

Tea's most visible security change is requiring government ID verification during signup. Users can either upload a selfie with their ID or submit a selfie video that gets processed by a third-party verification vendor. The goal is to ensure that only women can access the platform—not men creating fake profiles or bots automating harassment.

This is theoretically sound. Identity verification makes it harder to spam, easier to trace harassment back to a real person, and prevents the most obvious impersonation attacks. Companies like Airbnb use similar approaches.

But here's the catch: you've now created a second database of government IDs and selfies tied to user accounts. That's arguably more sensitive than the Tea data itself. If that vendor's database is compromised, attackers get both your Tea profile and your government-issued identification.

Tea isn't storing that ID data—the third-party vendor is. But now there's another company in the supply chain with access to women's identification documents. That increases the attack surface, not decreases it.

Penetration Testing and Enterprise-Grade Security

Tea claims they've completed penetration tests and continue to conduct them "at the infrastructure level." They also claim the web app is protected by "enterprise-grade platform security and backend controls."

Penetration testing is good. It's a simulated cyberattack where security professionals try to break into your system, find vulnerabilities, and document them for fixing. It's more comprehensive than a standard vulnerability assessment.

But there's a gap between "we've done penetration testing" and "we've actually fixed every vulnerability we found." Security researcher Jonathan Leitschuh emphasized that the existence of pen tests is important, but the real question is whether Tea actually fixed the weaknesses that testing revealed.

Also, "enterprise-grade" is marketing language. It doesn't have a specific technical definition. Enterprise security typically means things like multi-factor authentication, encryption at rest and in transit, rate limiting on API endpoints, and audit logging. These are good practices, but they're table stakes for any serious company handling sensitive data.

The real test will be whether Tea avoids a third breach. Until then, any claims about security remain theoretical.

Content Moderation and Legal Liability

One of the biggest risks Tea faced after the breaches was legal liability from men who were posted about and identified. If a woman falsely accused a man of cheating or criminal behavior, or if her post enabled harassment or doxxing, Tea could be liable.

Tea's approach to this problem is proactive moderation. The company says it will monitor allegations, remove unchecked or false claims, and intervene on harassment patterns. For non-Tea users who want disputes resolved, there's a moderation review process.

This is smart from a liability perspective, but it creates a massive moderation burden. Every post, comment, and direct message potentially needs human or AI review to ensure it's accurate, good-faith, and doesn't enable harassment. That's expensive and imperfect.

Tea is also requiring users to "attest that they are participating in good faith," essentially asking women to sign a legal agreement that their posts are truthful. This is important for avoiding false accusation liability, but it also creates psychological friction. Women might self-censor out of fear of legal risk, even when their concerns are legitimate.

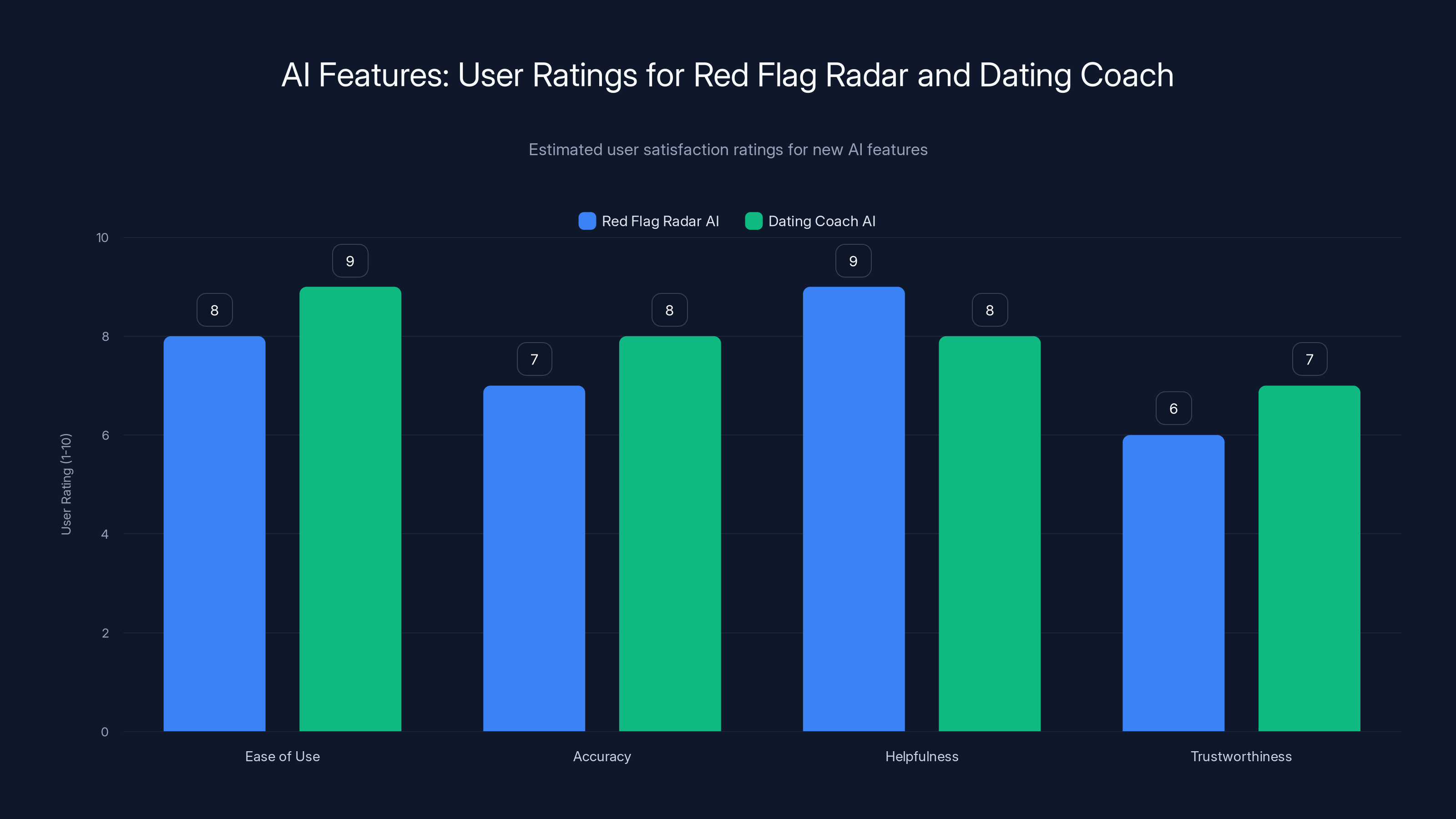

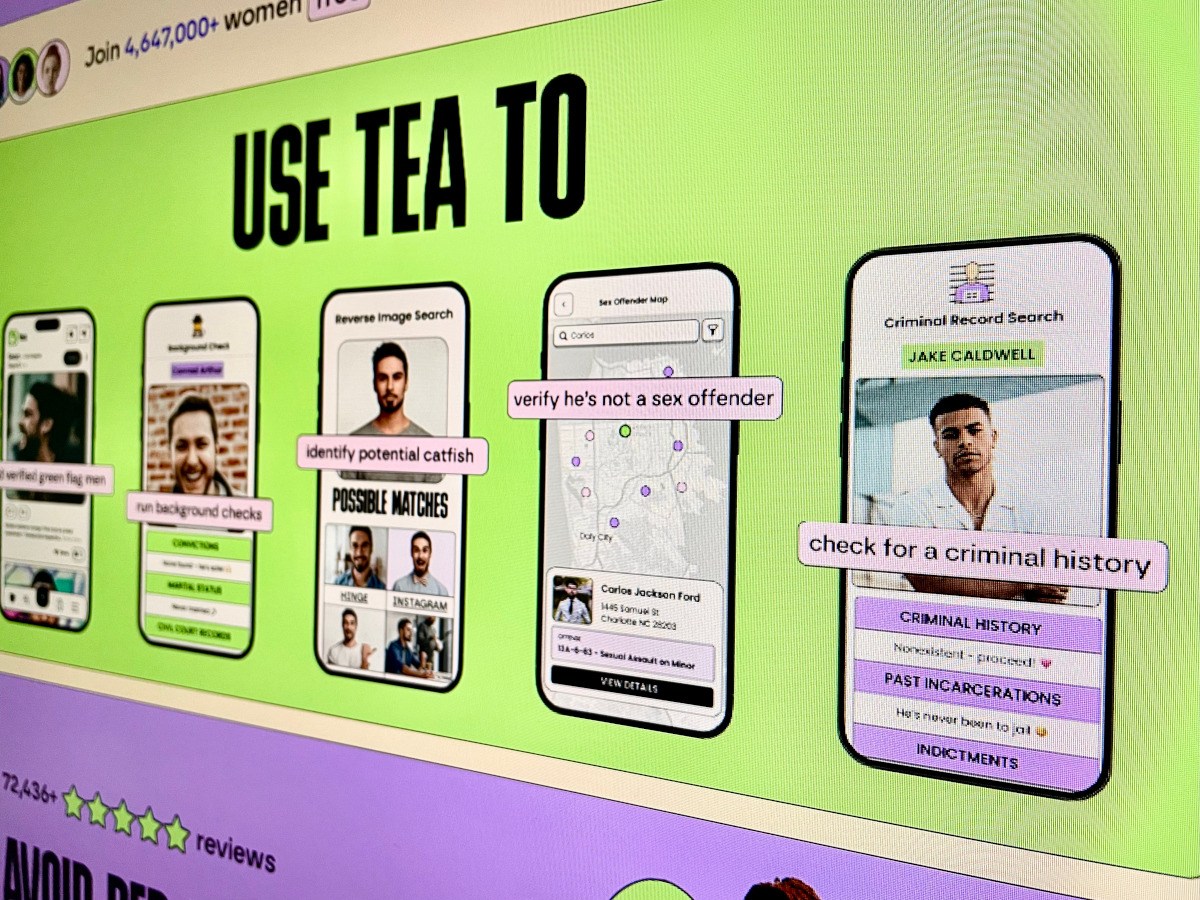

The New AI Features: Red Flag Radar and Dating Coach

Tea's comeback strategy includes new AI features on Android. The most significant is "Red Flag Radar AI," which is designed to analyze messages with potential matches and surface warning signs in real time.

Here's how it works: You paste a conversation you're having with someone (or the AI analyzes your existing chats). The AI looks for patterns that indicate dishonesty, emotional manipulation, love bombing, or other red flags. It flags things like inconsistent stories, pressure for money, isolation tactics, or unsolicited sexual content.

The second feature is an in-app AI dating coach that provides advice for different dating scenarios. If you're unsure about a conversation or a potential match, you can ask the coach for perspective.

Both features are designed to "supplement community insight," not replace it. In other words, the AI isn't trying to make the determination for you—it's offering a second opinion.

This is actually smart from a product perspective. AI is good at pattern matching and finding subtle inconsistencies in text. Humans are good at context, judgment, and understanding nuance. Combining them makes sense.

But there's an obvious limitation: the AI can only analyze what you show it. If you're not sharing the suspicious conversations, the AI can't help. And if the AI's training data is biased toward certain communication styles or cultural patterns, it might flag legitimate behavior as suspicious.

Estimated data shows that both AI features are perceived as helpful, with the Dating Coach AI slightly more trusted and easier to use. Estimated data.

Apple's App Store Rejection and iOS Users

Tea is not back on the iOS App Store. This is significant because iOS users made up a large portion of Tea's user base before the breach. The app is available on Android and through a new website, but iPhone users are left out.

Why? Apple cited policy violations, privacy concerns, and content moderation issues. The company was particularly concerned about the app's ability to enable harassment and about whether Tea was doing enough to protect user privacy.

Apple's rejection is both a setback and a reality check for Tea. It means the company has to convince Apple's review team that it's actually fixed the problems that led to the original removal. That's harder than just launching a website.

It also means Tea's user base is split. Android users can access the full app with new AI features. iOS users have only the website. This creates a fragmented experience and limits Tea's reach.

For iOS users, the website is actually the right choice. Web applications are easier for Apple to audit, don't have automatic update mechanisms that might hide security improvements, and give Apple more visibility into how the company is handling data.

The Rival Apps: Tea On Her and the Gender Dynamics

Tea's success spawned imitators and a backlash. Within weeks, a rival app called Tea On Her launched, allowing men to post anonymously about women. The premise was identical to Tea, just flipped: women's dating profiles and experiences were now subject to anonymous male commentary.

This created an obvious problem. If Tea was designed to help women identify dangerous men, Tea On Her was designed to help men shame or harass women. The gender dynamics are not the same. Women face higher rates of intimate partner violence, sexual assault, and harassment in dating contexts. The risks aren't symmetrical.

Both apps were removed from the App Store following complaints. But the existence of Tea On Her highlighted something uncomfortable: Tea's model, if extended equally, can be weaponized. It showed that the platform's creators hadn't fully thought through the gendered nature of dating safety.

The Lawsuit Problem: 10+ Class Actions and Counting

Tea faces significant legal liability from the breaches. The company is facing 10+ class action lawsuits in federal and state courts, alleging breach of implied contract, negligence, and failure to secure personal data.

In one lawsuit, a plaintiff alleged that Tea failed "to properly secure and safeguard personally identifiable information." This is the core allegation: Tea knew or should have known that storing government IDs, home addresses, and intimate messages was high-risk, and they didn't take adequate precautions.

Class action lawsuits in tech rarely result in huge payouts to individual users. The money usually goes to lawyers and settlement funds. But they're expensive to defend and they create legal uncertainty around the business model.

For Tea, the lawsuits are a sign that the company needs to fix not just the technical security but the structural liability of storing this much sensitive data.

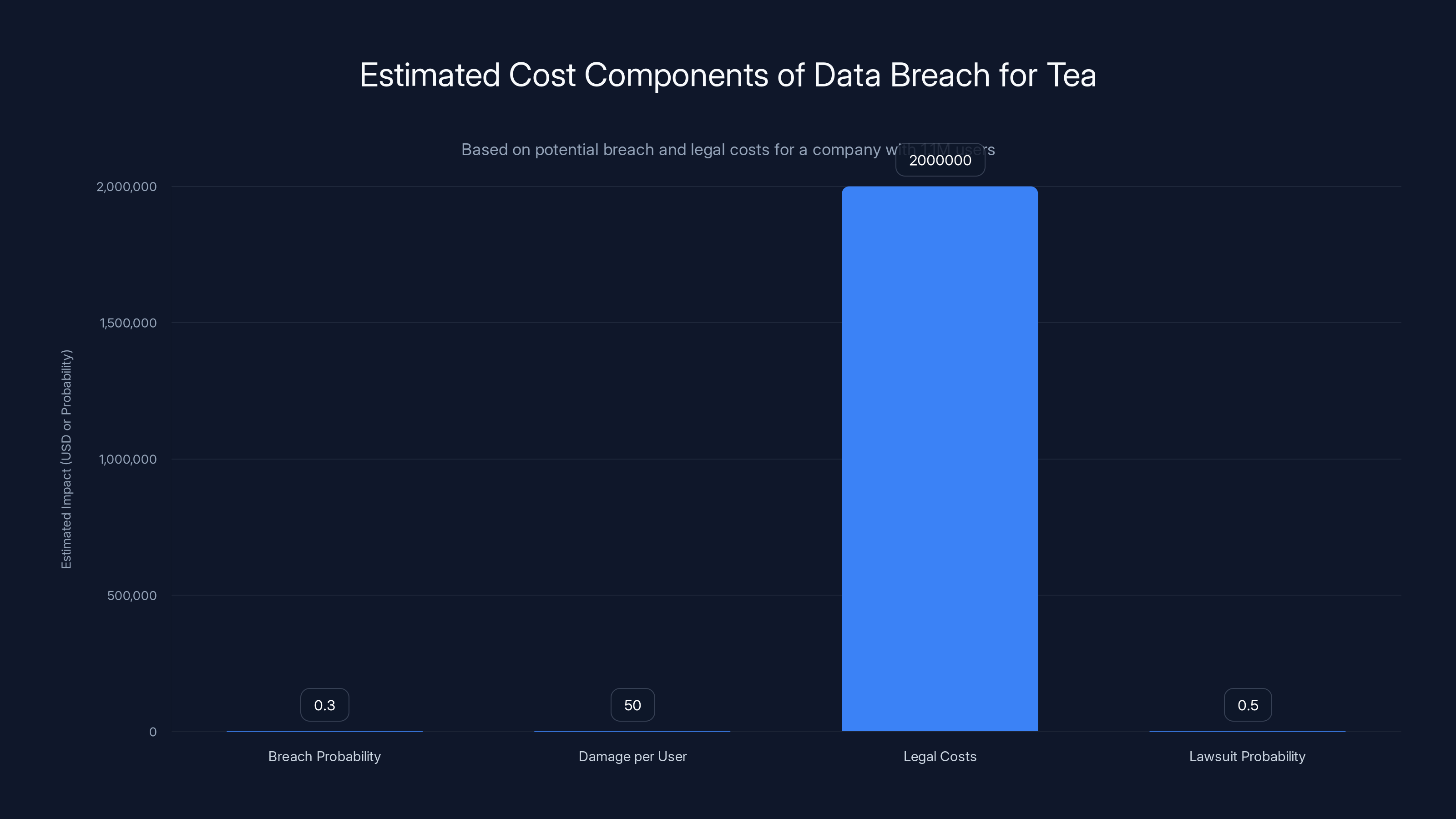

Mathematically, the expected cost of a data breach for a company of Tea's size handling this much sensitive data can be calculated using the following framework:

Where:

- = probability of a breach in a given year

- = average damage per user (credit monitoring, lawsuits, etc.)

- = total user base

- = legal defense costs

- = probability of facing lawsuits

For Tea, with 1.1M users affected and the sensitive nature of the data, this number is substantial.

The chart estimates the impact of different cost components on Tea's expected breach cost. With a breach probability of 30%, average damage per user of

Privacy by Design vs. Privacy Theater

Tea's comeback strategy includes rhetoric about "privacy by design" and making the app safer. But there's a difference between privacy-focused architecture and security theater.

Privacy by design means building the system so that you collect less sensitive data from the start. For example, instead of storing photos and government IDs, Tea could use a cryptographic hash of identification documents to verify uniqueness without storing the actual documents.

Security theater means adding visible security measures (like ID verification) that look good in press releases but don't fundamentally change the risk profile.

Tea is doing a mix of both. The third-party ID verification is somewhat theatrical—it doesn't prevent breaches, it just moves the risk to another company. But the internal access controls and penetration testing are more substantive.

The real test will be whether Tea can demonstrate that they've reduced the amount of sensitive data they store. If they're still holding government IDs, home addresses, and full message history, they haven't solved the fundamental problem.

The User Psychology: Why People Keep Using Apps After Breaches

Here's a hard truth: Tea will probably keep growing despite the breaches. Why? Because women need dating safety tools, and the alternatives are worse.

Using Tinder or Bumble without community safety information means relying on your own judgment about whether someone is being honest. You don't know if that "single, 32-year-old banker" is actually married with two kids. You don't know if he's been reported for assault by five other women.

Tea, flaws and all, gives you that information. Even with the breach risk, the benefit of having crowd-sourced safety warnings might outweigh the cost of exposing your own data.

This is a tragic choice that shouldn't exist. Women shouldn't have to choose between participating in a safety network and risking their personal information. But they do.

Psychologically, users also exhibit "breach amnesia." They download an app, use it, maybe hear about a breach, express outrage, then keep using it because the habit is established and the alternative is unacceptable.

Tea's team is betting on this. They're counting on the fact that dating safety is urgent enough that women will accept the risk.

Competitor Landscape: Other Safety-Focused Dating Apps

Tea isn't alone in trying to solve dating safety. Several other apps and tools have emerged with different approaches:

Noonlight (now called Life 360): A safety app that lets you send your location to emergency contacts if you feel unsafe. It integrates with some dating apps but isn't exclusively a dating app.

Bumble's safety features: Built-in verification, photo verification, and ability to report and block. The advantage is that Bumble controls the entire ecosystem—less risk of data exposure because fewer third parties are involved.

Hinge's safety resources: Links to resources about healthy relationships, red flag education, and reporting mechanisms.

Tinder's verification and community guidelines: Similar to Bumble, Tinder has built in verification and community standards.

Safety Wing community reports: Some dating app users share experiences on Reddit, Twitter, and other platforms, creating informal community knowledge.

None of these are perfect. Hinge and Bumble's approach is safer because they don't create a separate database of accusations—they focus on individual-level reporting and education. But they also don't give you the crowd-sourced "this man is dishonest" warning that Tea provides.

Tea's model is more aggressive and more useful, but also more risky.

Users should prioritize minimizing their data footprint and verifying information independently when using apps like Tea. Estimated data based on recommended safety practices.

What Should Happen Next: A Responsible Path Forward

If Tea wants to actually rebuild trust, here's what they should do:

1. Minimize data collection: Store only what's necessary. Don't keep home addresses or government IDs longer than verification requires. Implement automatic deletion policies.

2. End-to-end encryption: Make message content unreadable to Tea's servers. The company can still facilitate delivery but can't access conversations.

3. Anonymous flagging: Allow women to report red flags without attaching their identity to the report. Aggregate warnings so that patterns emerge without individual women's data being at risk.

4. Third-party audits: Hire independent security firms for regular audits and publish the results (with redactions for security).

5. Transparent data policy: Tell users exactly what data is stored, where it's stored, how long it's kept, and who has access.

6. Bug bounty program: Pay security researchers to find vulnerabilities before attackers do.

7. Crisis plan: If there's another breach, commit to notifying users within 24 hours with transparent details about what was accessed.

Some of these are expensive. But they're the cost of responsibly handling sensitive data about women's safety.

The Bigger Picture: Dating Apps and Privacy

Tea's situation is a specific case of a broader problem: dating apps collect and store massive amounts of sensitive personal information—photos, location history, conversation content, preferences—and they're often not prepared to protect it.

Major dating apps like Tinder, Bumble, and Hinge have also faced security issues and privacy concerns. In 2023, Tinder faced criticism for storing users' precise location data longer than necessary. In 2021, a researcher found that Grindr was sharing user HIV status with third-party advertisers.

The incentives are misaligned. Dating apps make money through subscriptions and advertising. More data = more valuable advertising targeting. More data also means more security risk, but that cost is externalized onto users.

Regulations like GDPR in Europe and emerging state-level privacy laws in the US are starting to change these incentives. But the US doesn't have comprehensive federal privacy legislation yet, so companies often prioritize growth over security.

Tea's situation should serve as a cautionary tale. Even a company founded specifically to address safety (Sean Cook created it after his mother was catfished) can fail at protecting user data. The business model of storing sensitive information about dating experiences is inherently risky.

What Users Should Actually Do

If you're considering using Tea or any similar app, here's a realistic framework for decision-making:

Assess your own risk tolerance: How much risk are you willing to accept to get access to community safety information?

Minimize your data footprint: Don't provide information Tea doesn't need. Use a photo that doesn't reveal your full face. Don't share your home address if you can avoid it. Be vague about your schedule and routines.

Use a dedicated email: Create an email address specifically for Tea and unlink it from your other accounts. This limits the damage if the Tea database is compromised.

Monitor your credit: If you've been on Tea, sign up for a credit monitoring service. The breach might impact you in ways that don't surface for months.

Trust but verify: Community warnings on Tea are useful, but they're not proof. Do your own research. Google the person's name. Ask friends. Verify information independently.

Report problematic behavior: If you encounter dishonesty, harassment, or danger, report it to Tea and to law enforcement if appropriate. Don't rely only on community reporting.

Consider the alternatives: Before signing up for Tea, consider whether you can get the same safety information from friends, from formal background checks, or from the primary dating app's built-in safety features.

Tea's Path to Redemption

Can Tea actually rebuild trust? Maybe, but it's going to take more than a new website and AI features.

The company needs to demonstrate that they've fundamentally changed how they think about data security. That means being transparent about breaches, being proactive about privacy, and showing that security isn't just a post-breach add-on but a core part of the business.

It also means accepting that some jurisdictions might not allow the app to operate. Apple has already made a judgment call. Other regulators might do the same. Privacy is increasingly a regulatory concern, not just a user concern.

Mostly, Tea needs to answer a hard question: Is the current business model even viable?

If the company's value comes from storing and aggregating sensitive data about women's safety concerns, then that value comes with massive risk. Either Tea needs to fundamentally change its data architecture, or it needs to accept that it will always be a target for breaches and lawsuits.

The easy path is to keep collecting data, add more security theater, and hope for the best. But women using the app deserve better.

Looking Forward: Privacy Regulations and the Future of Safety Apps

Regulation is coming. The US has proposed multiple privacy bills at the federal level, and several states (California, Virginia, Colorado, Connecticut, Utah, Montana, Delaware) have already passed comprehensive privacy laws.

These laws typically require companies to:

- Collect only necessary data

- Allow users to delete their data

- Notify users of breaches quickly

- Provide transparency about how data is used

- Offer opt-out mechanisms for data sharing

For Tea, these regulations could force the company to rethink its data model. Can the app work effectively if users can delete their data at any time? Can it work if women can request that their warnings be removed?

Maybe. But it might require a fundamentally different approach to safety—one that's less about persistent, retrievable records and more about ephemeral, anonymous signals.

FAQ

What exactly was stolen in the Tea app data breach?

Two separate breaches occurred in July 2024. The first exposed 72,000 images including 13,000 selfies with government IDs, home addresses, and private messages. The second breach affected 1.1 million users and exposed additional messages, phone numbers, and intimate conversations about topics like abortion, infidelity, and abuse.

How does Tea's new ID verification work?

Tea requires new users to verify they're women by uploading either a selfie photo with a government ID or submitting a selfie video. A third-party verification vendor processes these images to confirm identity without Tea storing the actual government ID documents. This is supposed to prevent men from creating fake profiles.

Is Tea still available on Apple's App Store?

No. Apple removed Tea from the App Store after the data breaches and has not reinstated it. The app is available on Android and through a new website, but iPhone users cannot download it from the official App Store.

What are the new AI features on Tea?

Tea's Android app now includes an AI dating coach that provides advice for dating scenarios and a feature called Red Flag Radar AI (launching soon) that analyzes messages with potential matches to surface warning signs like dishonesty, manipulation, or predatory behavior.

How likely is another data breach at Tea?

Tea claims they've implemented penetration testing and enterprise-grade security, but there's no way to guarantee another breach won't happen. Any company storing sensitive data is a target. The real question is whether Tea has addressed the specific access control and data isolation issues that led to the first breaches.

Should I use Tea after the breaches?

That depends on your risk tolerance and what alternatives you have. Tea provides valuable crowd-sourced safety information that dating apps don't. But using it means accepting that your photos, messages, and home address could be compromised. Consider minimizing the data you share, using a dedicated email, and monitoring your credit.

What legal protection do Tea users have after the breach?

Users affected by the breach can join one of 10+ class action lawsuits alleging negligence and failure to secure personal data. These cases will likely take years to resolve. Individually affected users may receive partial reimbursement for credit monitoring and other damages, but don't expect large payouts.

Can I request deletion of my data from Tea?

Yes. Under privacy regulations like GDPR and most US state privacy laws, you can request that Tea delete your data. The company should comply, though full deletion from backups and third-party systems may take time.

Why did Tea On Her get removed from the App Store too?

Tea On Her was a male version of Tea allowing men to post about women. It was removed for similar reasons as Tea: policy violations, privacy concerns, and content moderation issues. The gender dynamics of male-anonymous-posting-about-women creates different safety and harassment risks than women posting about men.

What should I do if I think I was affected by the breach?

Sign up for credit monitoring (usually offered free as part of breach settlements), change your passwords for other accounts using the same email, monitor your financial accounts for suspicious activity, and consider a credit freeze to prevent identity theft. You can also join a class action lawsuit if one is still accepting claims in your jurisdiction.

Conclusion: Privacy, Safety, and the Impossible Choice

Tea's comeback attempt reveals something uncomfortable about dating safety in the digital age: we've created a scenario where women need to choose between safety and privacy.

On one side, dating apps like Tinder, Bumble, and Hinge provide useful tools for meeting people, but they don't adequately protect against liars, cheaters, and dangerous men. Individual users are left to their own judgment.

On the other side, Tea provides community-sourced warnings about specific men, which genuinely helps women make safer choices. But the only way Tea can function is by collecting and storing massive amounts of sensitive data—government IDs, home addresses, intimate messages—creating a target for hackers.

There's no perfect solution here. Any system that provides crowd-sourced safety information has to store enough data to make that information useful. And any system storing that much sensitive data is vulnerable to breaches.

What Tea can do is make better choices about minimizing data collection, implementing encryption, being transparent about risks, and responding quickly and honestly when things go wrong.

The new website, the AI features, and the ID verification are steps in the right direction. But they're not a complete solution. The company will probably face more criticism, more lawsuits, and more pressure from regulators before they find a sustainable balance between safety and privacy.

For users, the decision is personal. Tea offers real value—women have genuinely found it useful for identifying dishonest or dangerous men. But that value comes with real risk.

Make an informed choice. Understand what data you're sharing, minimize it where you can, protect yourself with credit monitoring, and demand that Tea and other platforms do better.

The future of dating safety depends on it.

Key Takeaways

- Tea's two data breaches in July 2024 exposed 72,000 images in the first breach and 1.1M users in the second, including government IDs, home addresses, and intimate messages

- New security measures include third-party government ID verification, penetration testing, and stricter access controls, but don't eliminate the fundamental risk of storing sensitive data

- Red Flag Radar AI analyzes conversations for warning signs, and a dating coach AI provides relationship advice, both available on Android

- Apple has not reinstated Tea on the iOS App Store, limiting the app's reach to Android users and web-based access

- Tea faces 10+ class action lawsuits alleging negligence and failure to protect personal data, creating long-term legal and financial uncertainty

- Using Tea requires accepting significant privacy risk to access community-sourced dating safety information—a tradeoff without perfect solutions

- Future regulations like state privacy laws and proposed federal legislation will force companies like Tea to rethink how they collect and store user data

Related Articles

- RedDVS Phishing Platform Takedown: How Microsoft Stopped a $40M Cybercrime Operation [2025]

- ExpressVPN 78% Discount Deal: Complete Savings & Comparison Guide [2025]

- UK Digital ID No Longer Mandatory: What Changed [2025]

- UK Scraps Digital ID Requirement for Workers [2025]

- Iran Internet Blackout: What Happened & Why It Matters [2025]

- Instagram Password Reset Email Bug: What Happened and What You Need to Know [2025]

![Tea App's Comeback: Privacy, AI, and Dating Safety [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/tea-app-s-comeback-privacy-ai-and-dating-safety-2025/image-1-1768480786394.jpg)