AI Climate Claims: Big Tech's Promises vs. Reality [2025]

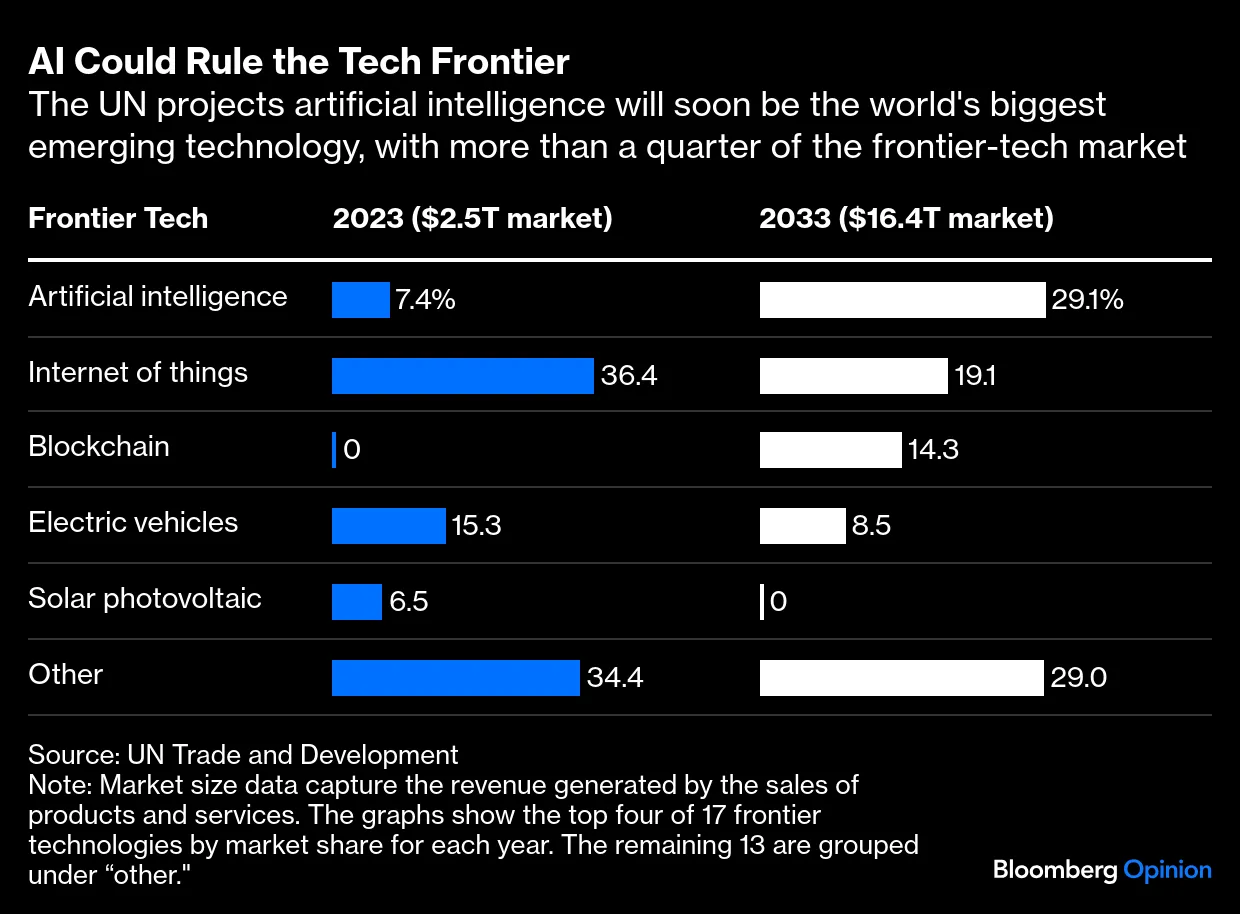

Let me start with a number that should make you uncomfortable. A few years ago, Google began claiming that artificial intelligence could cut global greenhouse gas emissions by between 5 and 10 percent by 2030. That's roughly equivalent to eliminating what the entire European Union emits annually. The company's chief sustainability officer published op-eds about it. The media picked it up. Academic papers cited it.

Then an energy researcher named Ketan Joshi decided to actually track down where this number came from.

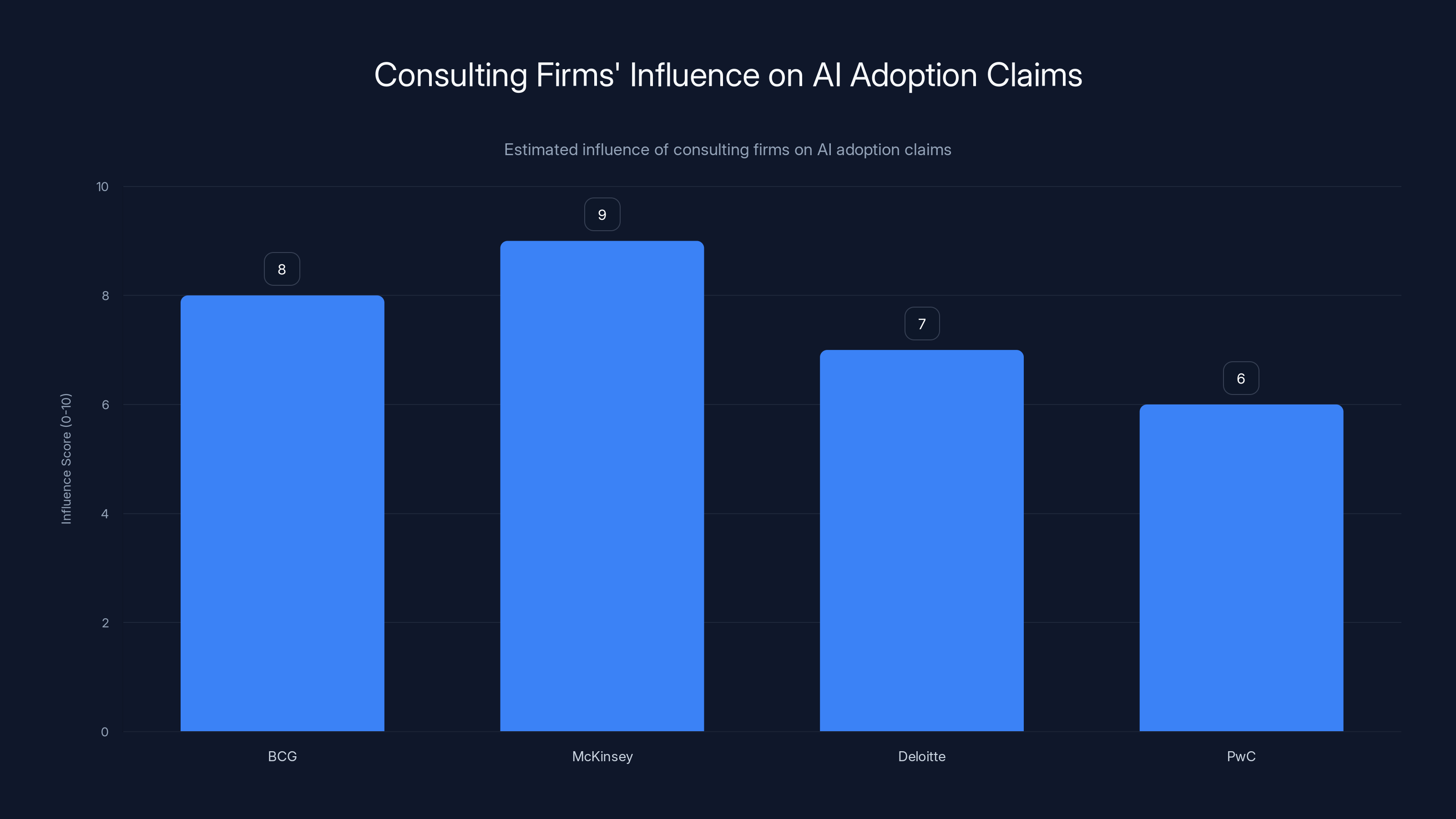

What he found was shocking, not because the math was complicated, but because it wasn't grounded in much of anything. The 5 to 10 percent claim traced back to a Google and BCG consulting report, which itself cited a 2021 BCG analysis that simply pointed to the company's "experience with clients" as the basis for massive emissions reductions. No peer review. No independent verification. Just consulting firm confidence.

This is the core problem with how tech companies talk about AI and climate change. They make enormous promises, spread them through business press, policy channels, and academic citations. But when you pull the thread, you often find very little solid evidence underneath.

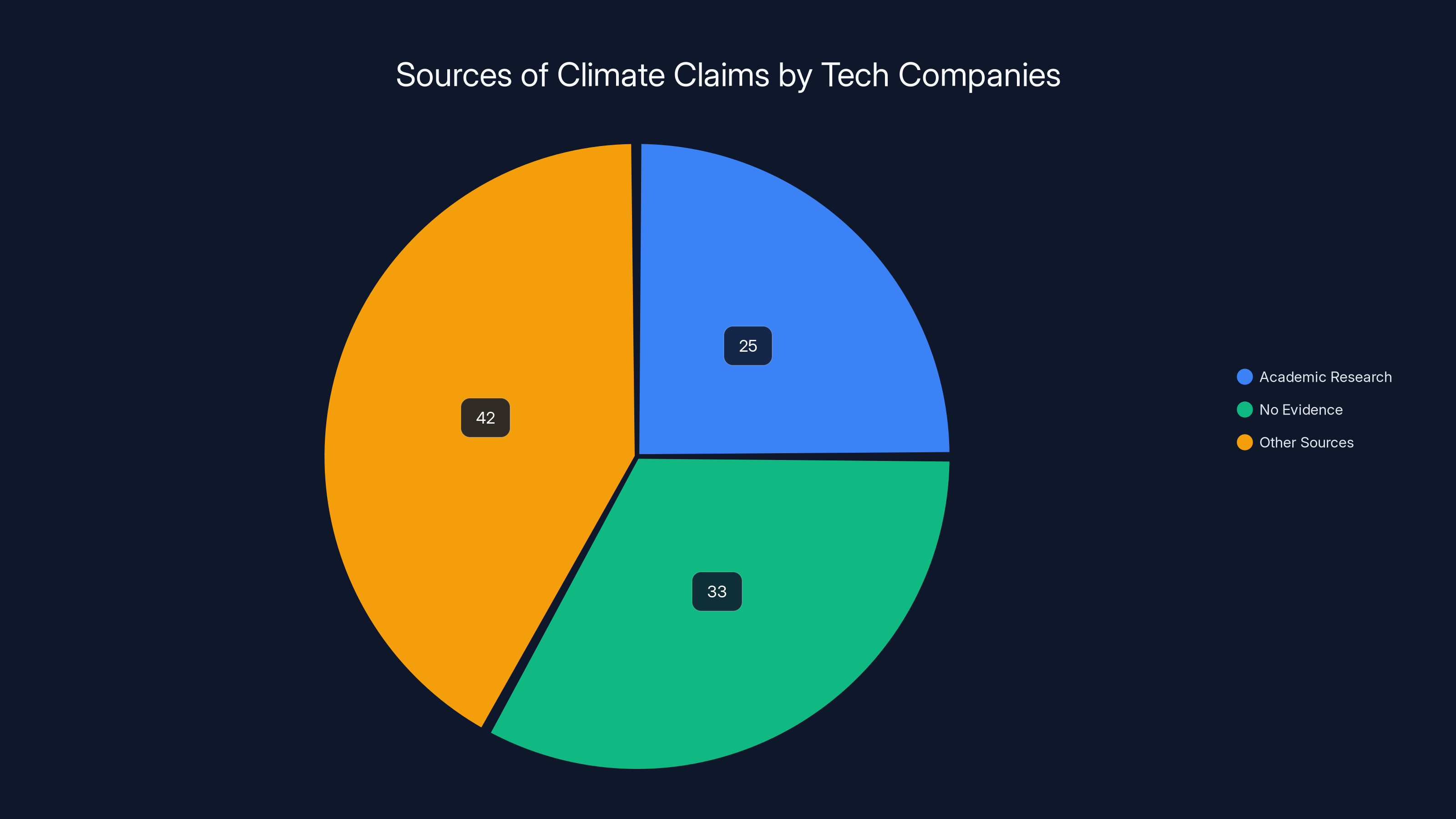

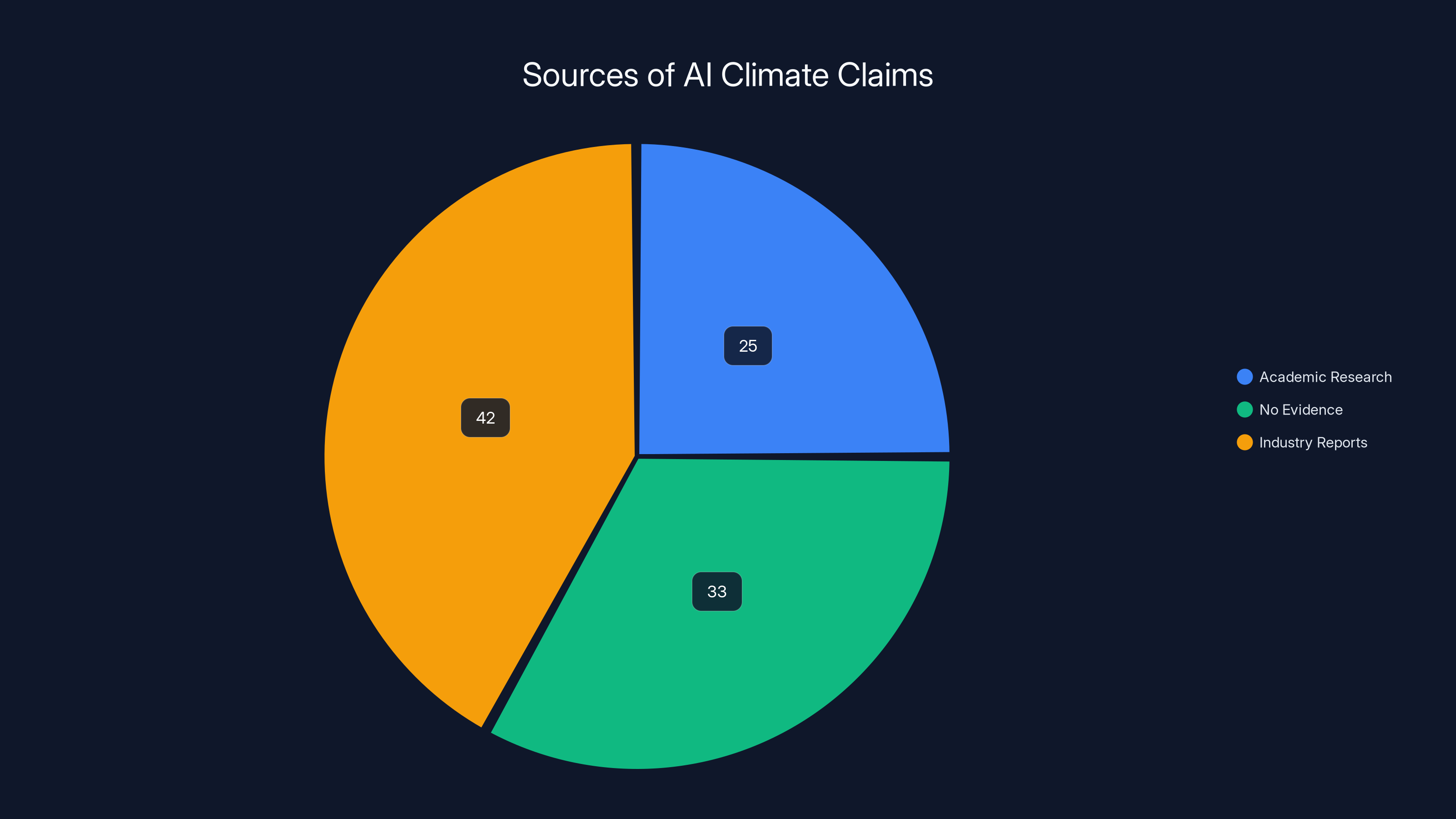

Joshi's new report, released in 2025, examined over 154 specific claims about how AI will benefit the climate. The findings are damning: just 25 percent were backed by academic research. A third cited no evidence whatsoever. The rest fell somewhere in between, relying on industry reports, white papers, or unrepeated company claims.

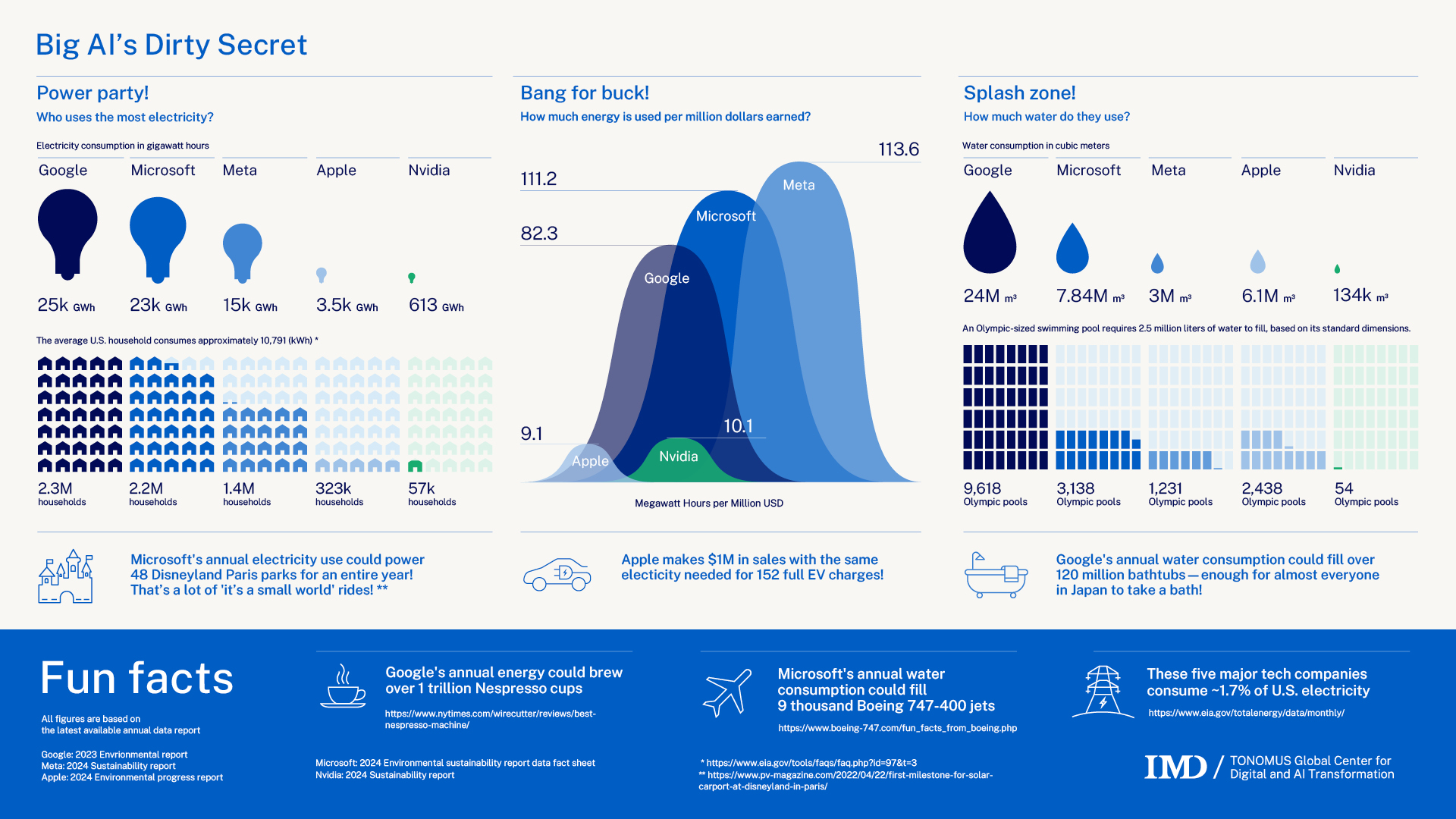

This matters more than you might think. Right now, tech companies are investing hundreds of billions in AI infrastructure. Data centers are consuming enormous amounts of electricity. Coal plants that were supposed to retire are staying open. Hundreds of gigawatts of natural gas power plants are being built specifically to power AI compute. Tech executives justify all of this by pointing to climate benefits that, it turns out, they haven't actually proven.

So what's really happening? Let's dig into the gap between what tech says about AI and climate, and what the evidence actually shows.

The Problem With Unproven Climate Claims

There's a pattern in how tech companies make climate promises. An executive gives a speech. A consultant writes a report. The media covers it. Academic researchers cite it. Within months, the claim has traveled from an unverified assertion to something that sounds like established fact.

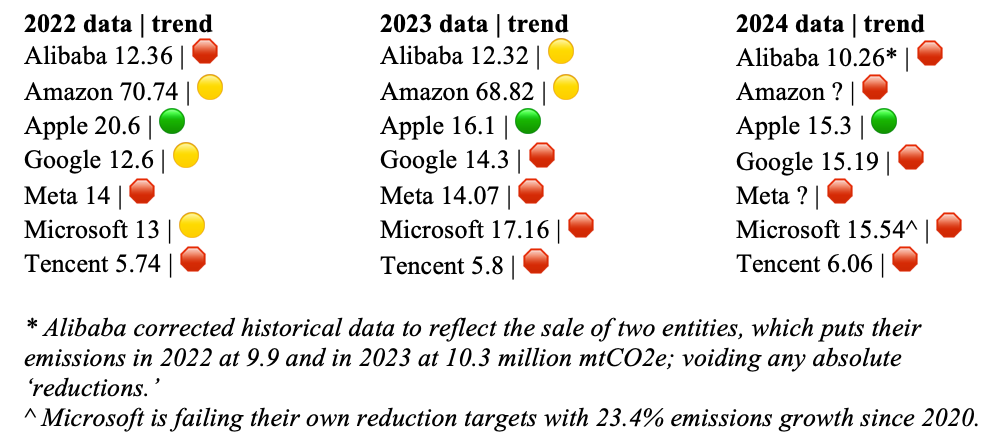

But here's what's different now: companies are making these claims while simultaneously building the energy-intensive infrastructure that contradicts them. Google's emissions have increased significantly since the AI buildout began. Microsoft signed a massive renewable energy deal specifically to power AI data centers. Yet both companies continue to tout climate benefits from AI that they haven't demonstrated.

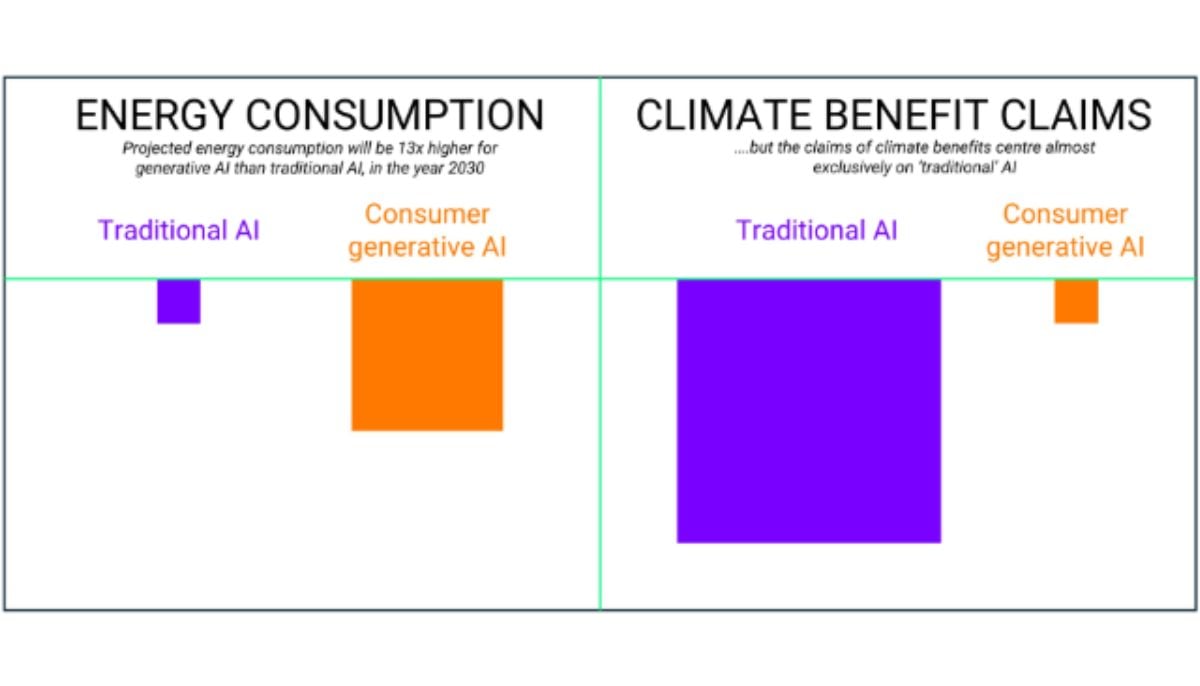

The problem isn't that AI couldn't theoretically help with climate. Machine learning has legitimate applications for climate modeling, grid optimization, materials science, and other areas. The problem is that companies are conflating different types of AI, making claims about one type of AI while building infrastructure for another, and then using unproven benefits to justify energy-intensive buildout.

David Rolnick, an assistant professor at McGill University who chairs Climate Change AI, acknowledges that quantifying AI's climate impact is difficult. But that's precisely the problem. When something is hard to measure, you should be more cautious about making big claims, not less. Instead, tech companies have done the opposite.

They've made bigger and bigger promises while the underlying evidence has remained thin. OpenAI's CEO Sam Altman has said AI will "fix" the climate. Eric Schmidt, former Google CEO, argued that rather than constraining AI development, we should bet on AI solving climate problems. The Bezos Earth Fund hosted an entire Climate Week event about how "AI will be an environmental force for good."

But what does that actually mean? What specific mechanisms are they describing? How would you measure success? When you ask for details, the claims get much softer.

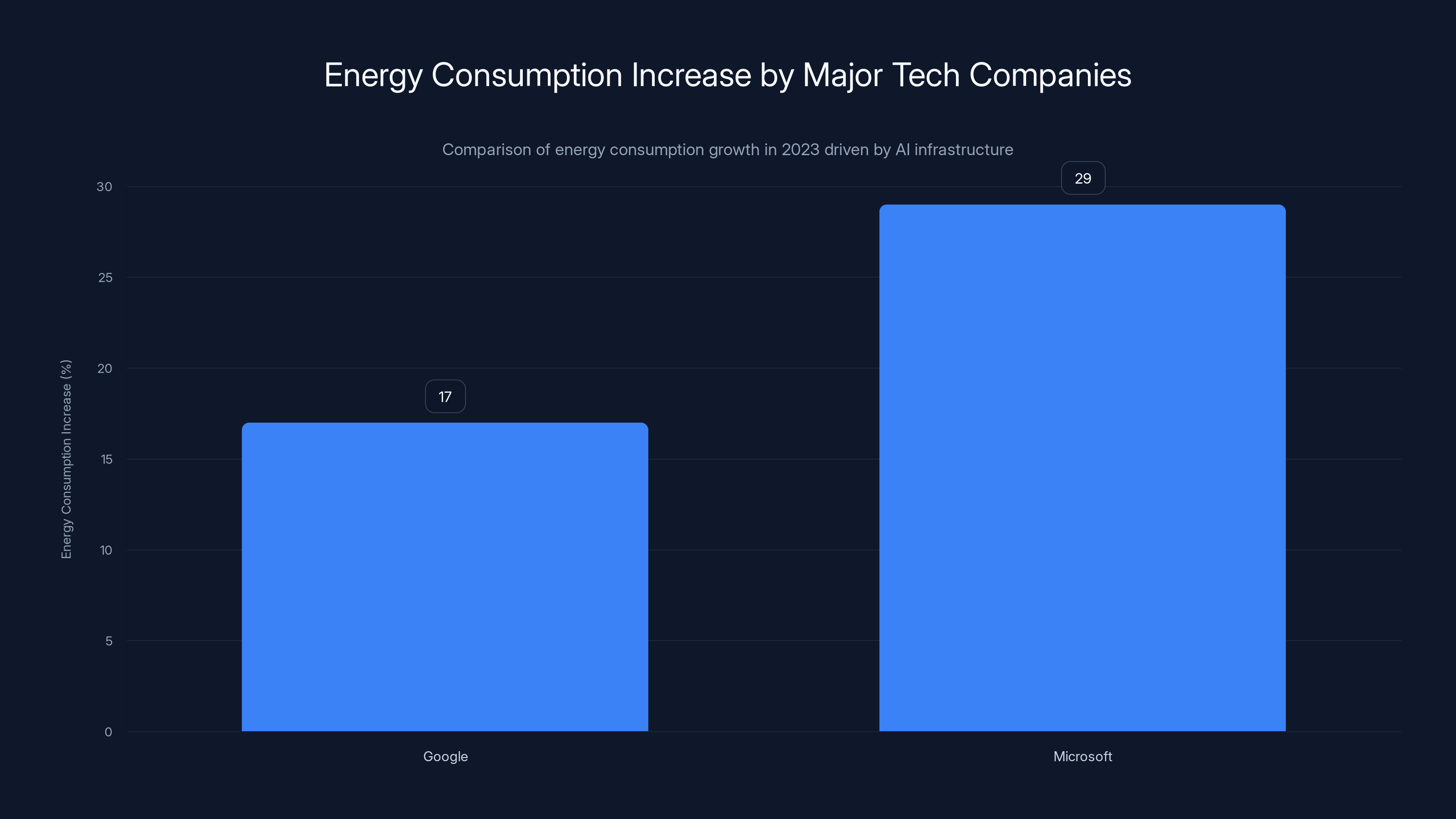

In 2023, Google's energy consumption increased by 17% and Microsoft's by 29%, primarily due to AI infrastructure demands. Estimated data.

Why Tech Companies Conflate Different Types of AI

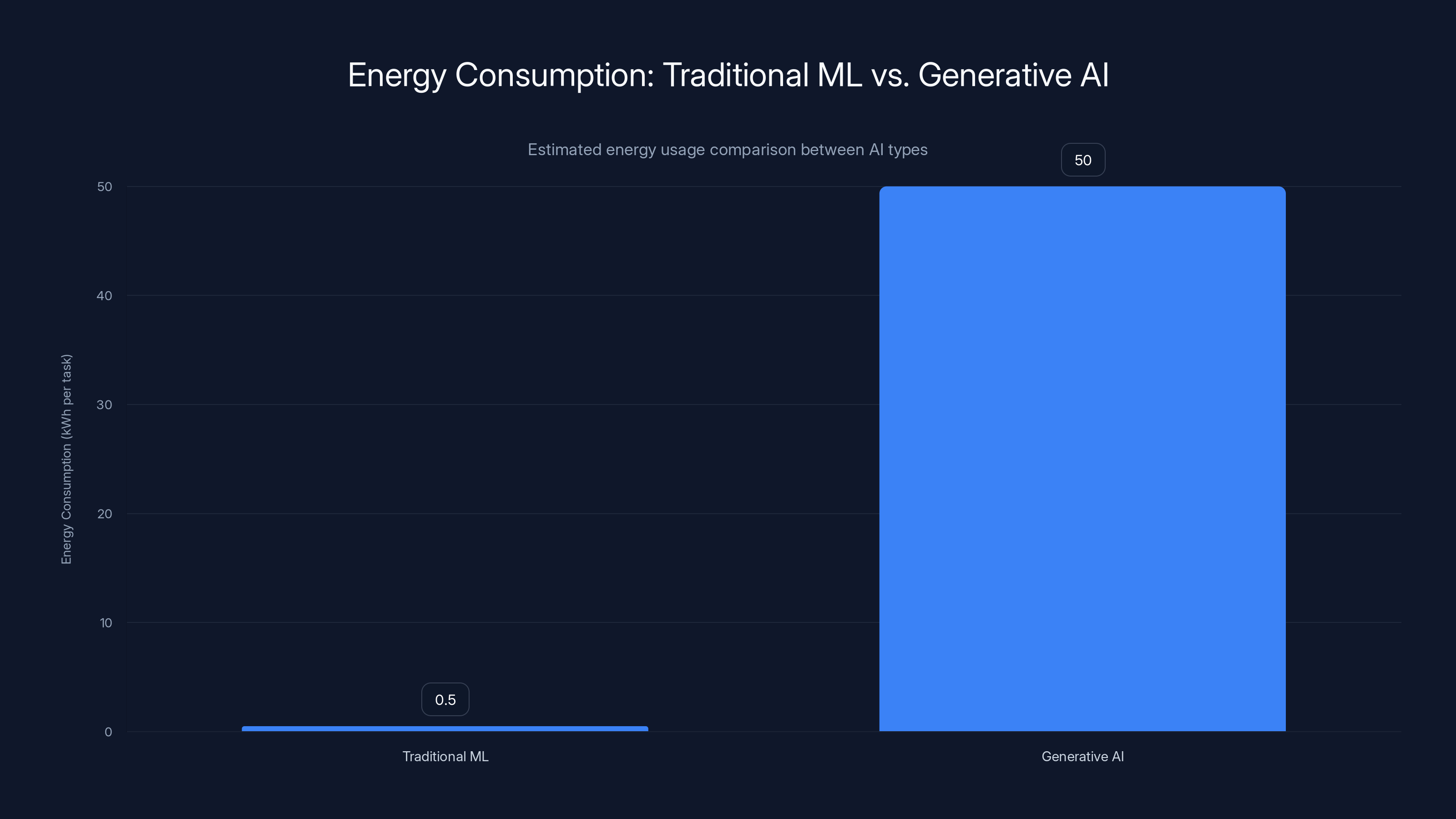

This is where the analysis gets interesting and frustrating. There are many types of AI, and they have dramatically different energy profiles.

Traditional machine learning has been used for decades in climate science. It powers weather models, helps optimize electricity grids, assists in materials discovery. These applications exist across universities, research institutions, and energy companies. They're not particularly energy-intensive. A researcher can train a machine learning model on a laptop if they need to.

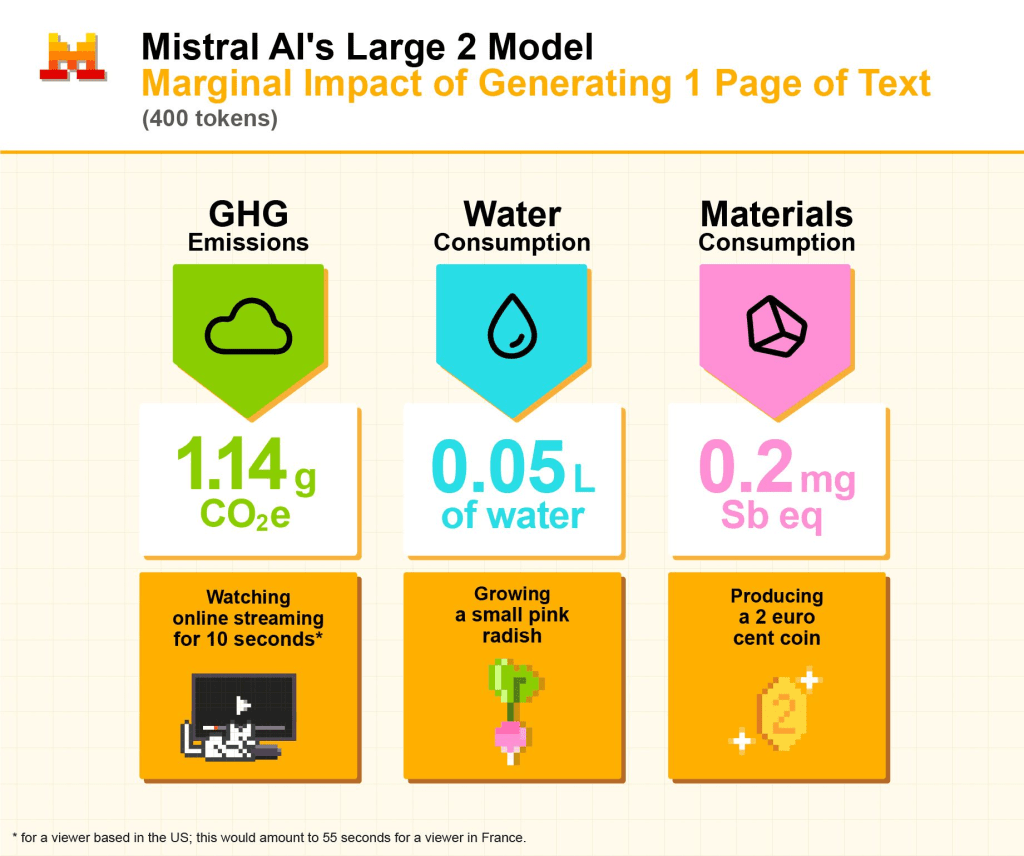

Generative AI is different. ChatGPT, Claude, Gemini, and similar models require massive amounts of compute. Training involves processing terabytes of text, running billions of parameters through neural networks, and performing complex optimization. Then inference, the process of running the model on user queries, requires significant compute at scale. A single ChatGPT conversation uses more electricity than some households consume in a day.

When tech companies talk about AI and climate, they often blur these distinctions. They'll talk about "AI" generally, mentioning machine learning applications in climate science. Then they'll justify building massive generative AI infrastructure by pointing to those climate benefits. It's technically true that some AI helps the climate. It's misleading to use those examples to justify building the specific type of AI that doesn't obviously help the climate and consumes enormous energy.

Joshi's report found that nearly all of the major claims examined conflated traditional AI with consumer-focused generative AI. The distinction matters enormously. It's the difference between using a hammer (actually helpful) and justifying buying a bulldozer because you sometimes use it to drive nails.

The energy requirements are staggering. Training a single large language model can consume as much electricity as a few thousand homes use in a year. Then, once deployed, these models consume power continuously as millions of users run queries. A single Google search might use 0.3 watt-hours of energy. A ChatGPT conversation uses roughly 50 times that. Scale that up across billions of daily interactions, and the energy footprint becomes massive.

Yet companies continue to justify this buildout by pointing to climate benefits that primarily apply to other, less energy-intensive forms of AI.

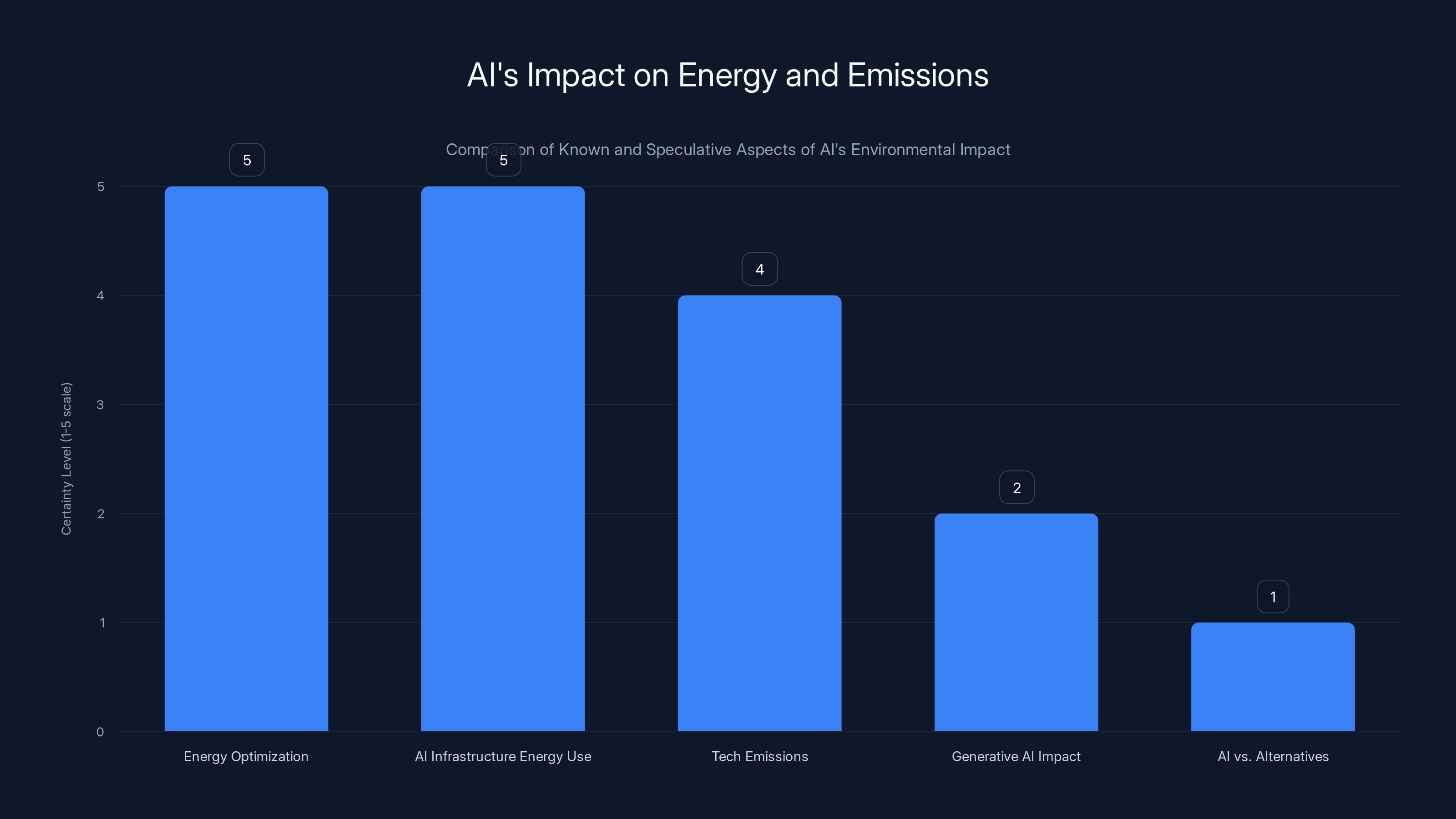

This chart contrasts the certainty levels of various aspects of AI's environmental impact. Known impacts like energy optimization and infrastructure energy use are well-documented, while the net climate impact of generative AI and its comparison to alternative solutions remain speculative.

The Google Precedent: How One Claim Became Doctrine

Let's go deeper into the Google 5 to 10 percent claim because it's instructive. It shows exactly how unproven claims become accepted facts.

In late 2023, Google published the claim that AI could reduce global emissions by 5 to 10 percent by 2030. This was a massive assertion. To put it in perspective, this would be equivalent to eliminating all of India's annual emissions. The number was so large that it was immediately attractive to policymakers, journalists, and other companies looking for positive narratives about AI.

Google's chief sustainability officer published it in an op-ed. It was quoted in major publications. Academic researchers cited it. By 2024, it had become a common reference point in policy discussions about AI.

But where did it actually come from? Joshi traced it back. Google cited a paper published by Google and BCG. That paper, in turn, cited a 2021 BCG analysis. And that analysis didn't cite peer-reviewed research or independent modeling. It cited BCG's "experience with clients."

Consulting firms have many admirable qualities, but objective climate science isn't typically their strength. They have financial incentives to tell clients that the services they're selling will help them reach climate goals. They're not peer-reviewed. Their methodologies aren't transparent. And yet, this became the basis for one of the most-cited claims about AI and climate.

More remarkably, Google has continued to use these numbers. Even after its own 2023 sustainability report admitted that AI buildout was significantly driving up corporate emissions, the company continued citing the 5 to 10 percent figure. In 2024, it included these numbers in a memo to European policymakers.

When WIRED asked Google about the methodology, the response was vague. The company said it "stood by the methodology, grounded in the best available science" but didn't explain specifically how BCG's client experience translated into a global emissions reduction figure. It pointed to a methodology page but didn't elaborate.

BCG didn't respond to questions about their analysis at all.

This is the pattern. Tech companies make claims. They cite internal or consulting reports. When pressed, they provide general statements about methodology without detailed explanation. And meanwhile, these claims spread to policy documents, academic papers, and become part of the broader conversation about AI.

The Scale of Unsubstantiated Claims

Joshi's report analyzed 154 specific climate claims made by tech companies, energy associations, and others about how AI will serve as a net climate benefit. The breakdown is revealing:

- 25 percent cited academic research

- 33 percent cited no evidence at all

- 42 percent cited other sources (industry reports, company white papers, consulting analyses)

That means roughly three-quarters of major climate claims about AI lack academic backing. For a claim this consequential, affecting billions of dollars in infrastructure investment and policy decisions, this is deeply troubling.

Why does this matter? Because academic research, despite its flaws, is subject to peer review. Researchers have incentives to get the science right, not to justify a business model. Peer review catches errors, unreasonable assumptions, and misapplied methodologies. It's not perfect, but it's better than a consulting firm's "client experience."

Moreover, the claims themselves often lack specificity. They'll say AI will "optimize supply chains" or "improve energy efficiency" without explaining what optimization mechanism they're describing, how it would work at scale, or how much energy those optimizations would actually save.

Consider a claim like "AI will reduce energy consumption in data centers by optimizing cooling systems." This is plausible. Machine learning could help optimize cooling efficiency. But how much reduction? In how many data centers? Over what timeframe? What's the capital cost of implementing these optimizations? Would that cost make them economically viable? None of these questions get answered in most claims.

The evidence gap becomes even more striking when you compare it to other major claims companies make. When a pharmaceutical company claims a drug reduces disease, it needs FDA approval backed by clinical trials. When a car manufacturer claims fuel efficiency, it needs to meet EPA standards with testing. But when a tech company claims AI will reduce global emissions by 5 to 10 percent, there's no requirement for evidence, no peer review, no independent verification. The company can just say it.

An estimated 75% of climate claims about AI lack academic backing, relying instead on non-peer-reviewed sources or no evidence at all.

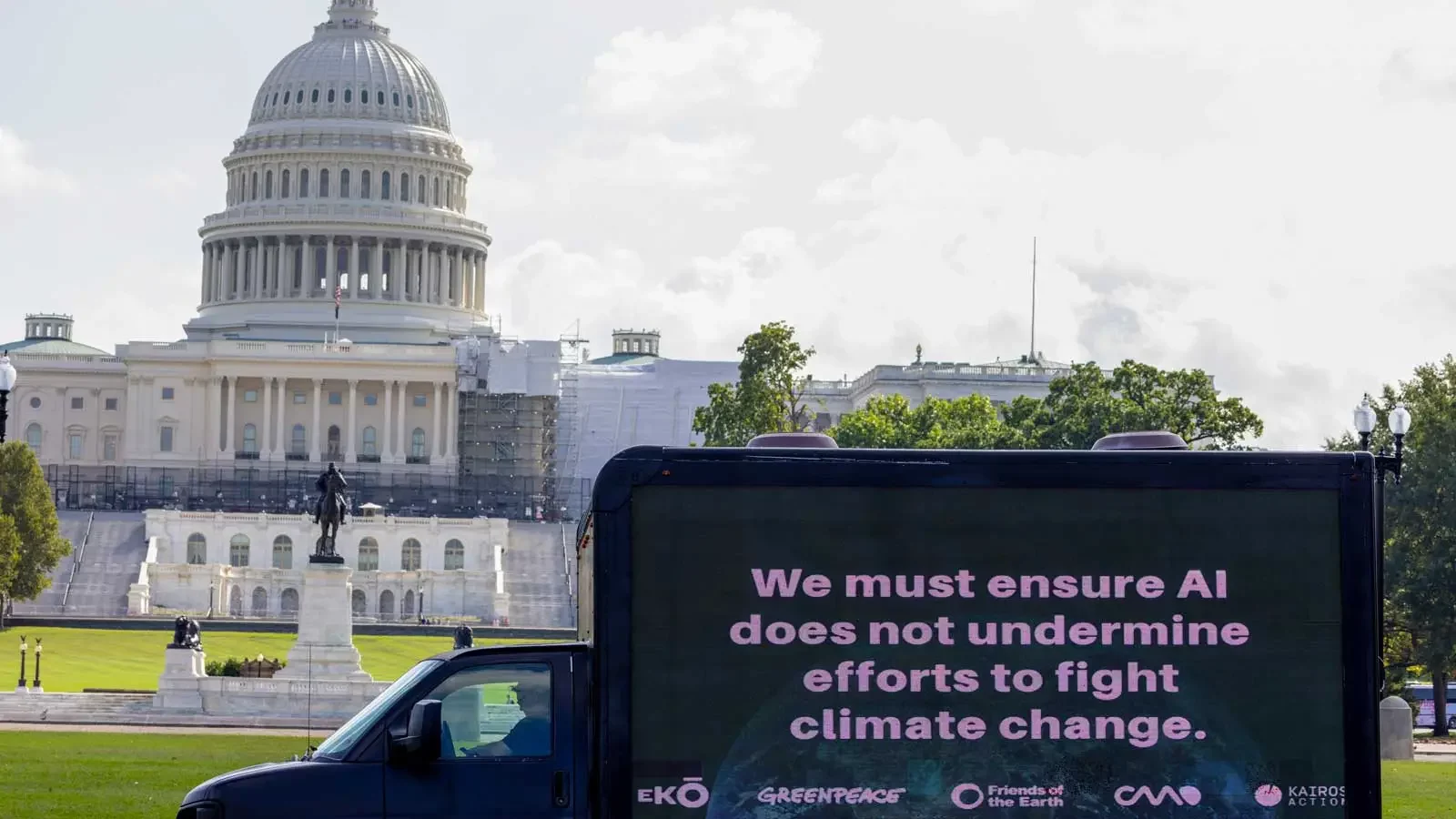

Why This Matters for Climate Policy

Here's where this moves beyond intellectual dishonesty into something more consequential.

Policymakers are making decisions about AI regulation, data center permitting, and infrastructure investment based partly on these unproven climate benefits. If a company can claim that AI will reduce emissions by 5 to 10 percent, it becomes easier to justify:

- Building new data centers in areas with limited renewable energy

- Keeping coal plants open to power AI infrastructure

- Reducing regulations on AI development

- Providing subsidies or tax breaks for AI buildout

- Opposing carbon taxes or energy pricing mechanisms

Eric Schmidt's statement that "I'd rather bet on AI solving the problem than constraining it" reflects this logic. The unstated assumption is that AI development will solve climate problems so effectively that we don't need to constrain emissions today. But what if the climate benefits don't materialize? What if they're much smaller than claimed?

Then we've invested trillions in infrastructure with massive energy requirements, justified by benefits that never arrived. Meanwhile, the actual time we need to reduce emissions is finite. The IPCC's best estimates suggest we need roughly 50 percent emissions reductions by 2030 and near-zero by 2050. That's a tight timeline. We can't afford to bet on unproven technologies while delaying actual emissions reductions.

There's a particular risk in how policymakers are approaching AI and climate. They're being presented with a false choice: either regulate AI development (and lose potential climate benefits) or allow unrestricted AI buildout (betting on climate benefits that may not come). But there's a third option: require actual evidence. Don't ban AI development. Just require that climate claims be backed by peer-reviewed research. That emissions reductions be independently verified. That methodologies be transparent.

This is normal for other environmental claims. Companies can't just say a product is "carbon neutral" without backing it up. They need third-party certification, independent verification, transparent methodologies. The same standard should apply to tech companies making climate claims.

The Energy Reality: What's Actually Happening Right Now

Let's step back and look at what's actually happening with AI infrastructure and energy, setting aside the marketing claims.

Data center energy demand is growing rapidly. Historically, data centers consumed about 1 percent of global electricity. That's been fairly stable for a decade. But AI is changing that trajectory. Google's energy consumption increased 17 percent in 2023, driven primarily by AI infrastructure. Microsoft's energy consumption increased 29 percent. Both companies have committed to purchasing massive amounts of renewable energy, which sounds good until you realize they're also pushing for data center construction in regions with limited renewable capacity.

In the United States, data center demand has driven electricity prices up in competitive markets. Some regions are facing electricity shortages because data centers are consuming available power faster than it can be generated. This has had a perverse effect: coal plants that were scheduled to retire are staying open longer because the region needs their generation capacity. Natural gas plants are being fast-tracked. Renewable projects are being prioritized for data center use rather than replacing fossil fuel generation elsewhere on the grid.

The numbers are staggering. Nearly 100 gigawatts of new natural gas power generation are in the pipeline specifically for data centers. By comparison, the United States' entire coal fleet is roughly 200 gigawatts. So in a few years, data centers could be consuming as much power as half the coal fleet.

This isn't hypothetical future harm. It's happening right now. Companies are making infrastructure decisions, governments are permitting power plants, and investment is flowing, justified partly by climate claims that lack evidence.

Now, is it possible that AI could, in theory, produce climate benefits that exceed these energy costs? Theoretically, yes. If AI helped develop breakthrough carbon capture technology, or discovered new battery chemistries, or solved materials science problems critical to renewable energy, those benefits could be enormous and could exceed the current energy costs.

But here's the thing: the companies aren't betting on that. They're not saying "we're investing in AI infrastructure betting that it will help discover fusion energy or carbon capture breakthroughs." Instead, they're making much softer claims about grid optimization, supply chain efficiency, and emissions reductions from other companies using their products. Claims that are both smaller in scale and much harder to verify.

Joshi's report found that only 25% of AI climate claims were backed by academic research, while 33% had no evidence and 42% relied on industry reports.

What Types of AI Actually Have Climate Benefits (And Which Don't)

Let's be precise about where AI can genuinely help with climate, and where it's hype.

AI that actually has climate benefits:

-

Climate modeling and prediction: Machine learning can process vast datasets to improve weather prediction and climate projections. This helps with disaster preparedness and planning. The compute requirements are modest compared to generative AI.

-

Materials discovery: Machine learning can help identify materials with useful properties (better batteries, more efficient solar panels, lighter structural materials). This is computationally intensive but the potential benefits are enormous.

-

Grid optimization: Machine learning can help balance electricity grids in real-time, manage renewable energy variability, and optimize transmission. Again, modest compute requirements compared to their potential value.

-

Energy efficiency in industrial processes: Manufacturing and chemical production use enormous amounts of energy. ML can optimize these processes. Many of these optimizations are already being deployed.

-

Drug discovery: Some climate-related solutions require new medicines (for heat stress adaptation, disease prevention as climate changes). ML accelerates drug discovery, though its energy cost is modest.

AI that doesn't obviously have climate benefits:

-

Large language models like ChatGPT: These consume enormous amounts of energy for training and inference. What climate benefit do they provide? The answers are vague. "Helping people write more efficiently?" The energy cost to deliver that marginal benefit is unclear. Mostly, they're useful for making companies money.

-

Image generation models: Similar story. They're impressive technically, and useful for various tasks, but how they contribute to climate goals is unclear.

-

Recommendation algorithms: These are useful for companies optimizing user engagement and advertising, but their climate benefit is speculative.

The problem is that the types of AI being deployed at massive scale right now (large language models and similar generative models) are not the types most likely to produce climate benefits. Meanwhile, the types most likely to help with climate (materials discovery, grid optimization, climate modeling) don't require nearly as much compute and aren't driving the massive infrastructure buildout.

It's backwards. The infrastructure boom is driven by generative AI because that's what produces revenue and captures user attention. The climate benefits, if they come, would more likely come from other applications of machine learning that are less central to the current buildout.

The Role of Consulting Firms and Industry Groups

One overlooked aspect of this story is how much of the unproven claims originate from consulting firms rather than tech companies directly.

Consulting firms like BCG, McKinsey, and others have powerful incentives to make optimistic claims about new technologies. They profit by helping companies adopt new technologies. They publish research that justifies those adoptions. Academic researchers who cite these reports often don't realize they're citing marketing material more than independent analysis.

BCG's 2021 analysis about AI reducing emissions by 5 to 10 percent was published in a business journal and presented as independent research. It wasn't. It was commissioned by a company (implicitly Google, based on subsequent reporting) and reflected that company's business interests.

This is perfectly legal and common in management consulting. But it's misleading when these reports are cited as evidence in policy discussions or academic papers. Policymakers should be aware that they're reading material produced by organizations with financial incentives to promote AI adoption.

McKinsey has published similar reports about AI's potential to reduce emissions in energy systems, manufacturing, and other sectors. Again, these reports identify real possibilities. Machine learning could help optimize many processes. But the reports don't clearly distinguish between what's theoretically possible, what's been demonstrated in pilots, and what's been deployed at scale. Everything gets lumped together as "AI's potential for climate impact."

Some industry associations have joined in. Energy industry groups have published reports suggesting that AI will optimize fossil fuel extraction and power generation, reducing emissions. This is technically possible (ML can optimize many industrial processes), but again, it's unclear how much benefit we're talking about, and the reports often minimize the energy requirements of the AI systems themselves.

There's also a temporal issue. Many of these analyses were published before the scale of AI infrastructure buildout became clear. They were written assuming ML would gradually optimize existing systems. Few anticipated that companies would invest hundreds of billions in new data centers specifically to power language models.

Consulting firms like McKinsey and BCG have high influence scores, indicating their significant role in promoting AI adoption claims. Estimated data.

The Honest Assessment: What We Actually Know

Let me be clear about what's actually demonstrable versus speculative:

Things we know:

- Machine learning can help optimize many industrial processes, reducing energy consumption in those processes. This is demonstrated through pilots and deployment in some companies.

- AI infrastructure (data centers, cooling systems, power distribution) requires enormous amounts of electricity. This is measured.

- The electricity demanded by AI infrastructure is growing exponentially and approaching constraints in some regions. This is observable.

- Some types of AI have lower energy requirements than others. This is physics.

- Tech companies' overall emissions have increased despite renewable energy investments, driven partly by AI infrastructure. This is in their sustainability reports.

Things that are speculative:

- The net climate impact of current generative AI infrastructure buildout. We don't have long-term data yet.

- Whether climate benefits from AI applications will exceed the energy costs of training and operating large language models. This hasn't been rigorously calculated.

- Whether AI will solve major climate problems faster than alternative solutions (like policy changes, renewable energy deployment, efficiency improvements). This is comparing hypotheticals.

- The specific magnitude of emissions reductions from AI applications in various sectors. Company claims range from 5 to 10 percent reductions but lack detailed supporting analysis.

When I look at the evidence, here's what seems most likely: AI will help optimize many processes, producing real but modest emissions reductions in those specific areas. Simultaneously, the infrastructure required to deploy AI at current scale requires energy that, in many regions, is coming from fossil fuels. The net impact could easily be negative, at least in the near term.

Over longer timescales (20 to 50 years), if AI genuinely helps solve major scientific problems (better solar cells, new battery chemistries, superior grid management), the benefits could become large. But that's a speculation. It's not something we can base infrastructure policy on right now.

Why Transparency and Evidence Matter

Here's the thing about asking for evidence: it's not about being anti-technology or anti-AI. It's about making decisions based on reality rather than wishful thinking.

Climate change is real. The timeline is real. We have maybe 5 to 10 years to slow emissions growth and 20 to 30 years to achieve large reductions. That's not much time. We need to invest in solutions that we're confident will work.

AI might be one of those solutions. Genuinely. Machine learning could accelerate the development of better batteries, solar panels, grid management systems, and carbon capture technologies. That would be fantastic.

But if we're going to bet trillions of dollars on that, we should have evidence. Not consulting firm white papers. Not company op-eds. Actual peer-reviewed research showing specific mechanisms and quantified impacts.

We should ask tech companies: exactly how will your AI help reduce emissions? What's the mechanism? How much reduction? What's your confidence level? What studies back this up? If they can't answer these questions, we shouldn't believe the claims.

This isn't a radical standard. It's what we ask of every other environmental claim. It's what regulators require of pharmaceutical companies, automotive manufacturers, and environmental consultants. Tech companies should be held to the same standard.

Moreover, transparency doesn't harm innovation. It enables it. If companies clearly articulated their climate benefits and had those benefits verified independently, that would strengthen their position, not weaken it. Right now, the vagueness and lack of evidence just creates suspicion.

Generative AI models like ChatGPT consume significantly more energy per task compared to traditional machine learning models. Estimated data.

The Researcher Perspective: What's Actually Being Studied

David Rolnick and other climate scientists who work with machine learning have a more nuanced view than either pure tech optimism or pure skepticism.

Rolnick acknowledges that quantifying AI's climate impact is genuinely difficult. Many climate benefits are indirect and emerge over long periods. A better grid management algorithm might allow more renewable energy to be integrated, which prevents coal plant construction, which reduces emissions. But that causal chain involves many other variables. It's hard to isolate the AI's specific contribution.

Moreover, the relevant timeframe matters. In the short term (1 to 5 years), large language models are clearly carbon-intensive and their climate benefits are speculative. In the medium term (5 to 20 years), if they help develop better materials or unlock energy solutions, the benefits could become significant. In the long term (50+ years), they could be transformative.

But policy decisions get made based on medium-term expectations. We're permitting data centers and infrastructure today based on speculation about 20-year impacts. That's a lot of uncertainty to base infrastructure decisions on.

Rolnick is concerned about the lack of evidence, but he's more focused on encouraging the kinds of research that would produce better evidence. Climate Change AI, the nonprofit he chairs, advocates for using machine learning to tackle climate problems. They want to see better research on AI's actual climate impact, better collaboration between climate scientists and AI researchers, and more investment in the types of AI that most directly help with climate.

That's the right approach. Not "ban AI." Not "believe all tech company claims." But "let's actually study this rigorously and fund the research that would tell us."

What Better Claims Would Look Like

Let me paint a picture of what responsible climate claims from tech companies would look like.

Instead of "AI will reduce global emissions by 5 to 10 percent," a responsible claim would be:

"Machine learning can optimize electricity grid operation, potentially reducing peak demand by 3 to 5 percent in regions with high renewable penetration. This optimization is based on published research (cite it), has been piloted in these specific regions (name them), and produces these specific emissions reductions (quantify them). The infrastructure cost is X dollars and the break-even period is Y years. We've verified these impacts through independent third parties (name them). Current deployment covers Z percentage of the global grid."

That's specific. Quantified. Verifiable. And still probably positive for AI.

Or: "We're investing in AI research specifically focused on discovering new battery materials. This research (cite published papers) has identified three candidate materials with promising properties. We estimate a 5-year timeline to commercialization, at which point the climate impact could be significant if adoption reaches X percent. Current funding for this research is Y dollars annually."

Again, specific. Time-bounded. Clear about what's been proven versus what's speculative.

Instead, what we get from tech companies is vague. "AI will help companies reduce energy consumption," without explaining how much, in which companies, through what mechanism, or by when.

The difference between these two approaches is the difference between honest climate communication and greenwashing. One is based on evidence and makes falsifiable claims. The other is marketing.

The Policy Question: What Should We Actually Do?

If tech companies' climate claims are mostly unproven, what should policymakers do?

I think there are a few reasonable approaches:

Require evidence for major climate claims. If a company claims that a technology will provide X percent emissions reductions, require peer-reviewed research or independent verification. Don't allow policy decisions to be based on unproven assertions. This isn't banning innovation, it's requiring honesty.

Separate the AI energy question from the AI benefit question. Acknowledge that AI infrastructure will consume significant energy. Don't pretend it's carbon-neutral. Then, separately, ask whether the benefits are worth that energy cost. Maybe they are. But don't conflate the two questions.

Fund independent research. We need rigorous, peer-reviewed research on AI's actual climate impact. Not consulting firm reports, but actual science. This research is underfunded relative to its importance. Government funding for this research would be well spent.

Prioritize AI applications with clear climate benefits. If we're going to invest in AI infrastructure, prioritize the applications most likely to help with climate. That means more investment in materials discovery, grid optimization, climate modeling. Less investment in language models for text generation, unless their benefits can be clearly demonstrated.

Apply consistent standards. Require tech companies to meet the same transparency and evidence standards we apply to other industries making environmental claims.

Think about alternatives. For many of the problems AI claims to solve, there are existing solutions. Better electricity pricing, renewable energy deployment, industrial efficiency standards, building insulation, etc. Some of these are more established and have better evidence bases than speculative AI applications. We should be comparing the actual evidence for AI to the actual evidence for other climate solutions, not comparing speculative AI benefits to the status quo.

These aren't radical positions. They're just asking for honesty and evidence-based decision-making.

The Broader Context: Why This Matters Beyond Climate

The AI and climate question is part of a larger pattern in how tech companies communicate about their products and their impact.

There's been a consistent pattern of tech companies making large claims about positive impact, getting those claims amplified through various channels, having the claims become conventional wisdom, and then later revealing that the evidence was much weaker than assumed.

Facebook claimed social media would strengthen democracy and social bonds. It turned out that engagement optimization favors divisive content. YouTube claimed its recommendation algorithm would surface authoritative information. It surfaced misinformation. Crypto companies claimed blockchain would democratize finance and eliminate intermediaries. It mostly redistributed wealth upward while consuming enormous amounts of energy.

Each time, the companies made claims that sounded good, media amplified them, and by the time the evidence caught up to the claims, trillions of dollars had been invested and policy had been shaped around assumptions that didn't pan out.

With AI and climate, we have a chance to learn that lesson before doubling down on another speculative bet. The evidence gap is clear. The infrastructure investment is happening fast. We still have time to require that the claims match the evidence.

What Individual People Can Do

If you're reading this and thinking "this is interesting but what can I actually do about it?" Here are some concrete steps:

Support research on AI and climate impacts. If you work at a research institution, fund rigorous studies on AI's climate effects. If you work in policy, allocate resources to independent verification of climate claims. If you're an individual donor, consider supporting Climate Change AI and similar organizations.

Ask hard questions. When you see a company claiming that AI will solve climate problems, ask for specifics. What's the mechanism? What's the quantified impact? What peer-reviewed research backs this up? Companies respond to scrutiny. If enough customers, investors, and policymakers demand evidence, companies will provide it.

Be skeptical of consulting firm reports. When reading about AI's potential climate benefits, check who funded the research. If the funder is also selling the solution, adjust your skepticism accordingly.

Follow energy policy. Watch what data centers are being built, where they're being built, and what power sources they're using. Compare that to companies' climate commitments. Often the two stories don't match, and that's telling.

Support transparency in AI. Advocate for regulations that require tech companies to be transparent about AI's energy costs and impacts. This shouldn't be controversial. It's basic accountability.

Looking Forward: What the Next 5 Years Will Show

Here's the thing about speculative technology claims: they're eventually resolved by reality.

In 5 to 10 years, we'll have much better data on whether generative AI has produced climate benefits. We'll know whether companies that claimed climate benefits actually delivered them. We'll see whether the energy cost of AI infrastructure was worth the benefits produced.

My prediction? The real story will be more complicated than the hype. Some AI applications will genuinely help with climate. Others won't. The net impact will depend heavily on where the electricity comes from and how efficiently the infrastructure is operated. Some early claims will have been right, others will have been wrong.

But instead of waiting 10 years to find out, we can require evidence now. We can ask companies to substantiate their claims. We can fund independent research. We can make policy decisions based on what we know rather than what we hope.

That's not anti-innovation. That's pro-honesty. And honestly, that's what climate change requires. We don't have time for wishful thinking. We need solutions we're confident will work.

AI might be part of the solution. But it's part of the solution only if we're serious about understanding its actual impact, not just its theoretical potential.

FAQ

What exactly did the Joshi report find about AI climate claims?

Joshi's 2025 report analyzed 154 specific claims about how AI will benefit the climate. The key findings: just 25 percent cited academic research, 33 percent cited no evidence at all, and 42 percent relied on industry reports or consulting analyses. The report also found that nearly all major claims conflated less energy-intensive forms of AI with consumer-focused generative AI, which requires massive computational resources.

Where did Google's "5 to 10 percent emissions reduction" claim come from?

The claim traced back to a Google and BCG paper, which cited a 2021 BCG analysis that based its estimates on BCG's "experience with clients" rather than peer-reviewed research or independent modeling. Despite later acknowledging that AI infrastructure was increasing its emissions, Google continued using this unproven figure in policy discussions as recently as 2024.

Why do tech companies conflate different types of AI when discussing climate benefits?

There's a strategic incentive to do so. Traditional machine learning applications (materials discovery, grid optimization) are less energy-intensive and have legitimate climate benefits. Generative AI (ChatGPT, Claude, Gemini) requires massive compute but its climate benefits are speculative. By mentioning both without distinguishing them, companies can justify building energy-intensive generative AI infrastructure using climate benefits that primarily apply to other applications.

What percentage of AI's emissions claims have peer-reviewed research backing them?

According to Joshi's research, only about 25 percent of the major claims about AI's climate benefits were backed by academic research. The remaining 75 percent either cited no evidence (33 percent) or relied on industry sources like consulting reports and company white papers (42 percent).

How much energy does large language model training actually consume?

Training a single large language model can consume as much electricity as a few thousand homes use in a year. The computational requirements scale exponentially with each generation of improvement. Meanwhile, inference (answering user queries) requires continuous power consumption at scale, with each ChatGPT conversation using roughly 50 times more energy than a Google search.

What types of AI actually have demonstrated climate benefits?

Machine learning has legitimate applications in climate modeling, materials discovery, grid optimization, and energy efficiency in industrial processes. These applications have been studied more rigorously and don't require the massive computational infrastructure of generative AI. The problem is that the infrastructure boom is driven by generative AI, which lacks clear climate benefits, not the more beneficial applications.

What should policymakers do if they can't verify AI climate claims?

Require evidence. Don't allow policy decisions to be based on unproven assertions. Apply the same transparency standards to tech companies that regulators apply to other industries making environmental claims. Fund independent research on AI's actual climate impact. Separate the question of AI's energy requirements from the question of its benefits, and don't let companies conflate the two.

How can I evaluate whether a company's climate claim about AI is credible?

Ask three questions: First, what is the specific mechanism by which this AI reduces emissions? Second, what is the quantified impact with a confidence level? Third, what peer-reviewed research or independent verification backs this up? If a company can't answer these questions clearly, the claim is likely more marketing than science.

Why does it matter if climate claims lack academic backing?

Because peer review catches errors, unreasonable assumptions, and misapplied methodologies. Academic research has incentives aligned with accuracy. Consulting firms have financial incentives to make optimistic claims. When policy decisions affecting trillions of dollars in infrastructure are based on unproven assertions from consulting firms rather than peer-reviewed research, we risk making expensive mistakes.

What's the realistic timeline for knowing whether AI's climate benefits will exceed its energy costs?

We won't have definitive answers for 5 to 10 years, once we have more data on deployed AI systems and their measured impacts. But we don't need to wait that long to require evidence for current claims. We can ask companies to substantiate what they're asserting now, based on what we know and what's been studied, rather than betting trillions on speculation about future benefits.

Key Takeaways

Big Tech's climate claims about AI are largely unproven. A comprehensive analysis of 154 major assertions found that just 25 percent cited academic research, while a third cited no evidence whatsoever. Companies like Google continue using unsubstantiated figures in policy discussions despite their own data showing increased emissions from AI infrastructure buildout.

The fundamental problem is that companies conflate different types of AI. Machine learning has legitimate climate applications (materials discovery, grid optimization) with modest energy requirements. But the current infrastructure boom is driven by energy-intensive generative AI (like ChatGPT) whose climate benefits remain speculative. The technology being deployed at massive scale is not the same technology with proven climate benefits.

Policymakers are making critical decisions about data center permitting, energy infrastructure, and AI regulation based on claims lacking rigorous evidence. This has real consequences: coal plants staying open longer, natural gas buildout accelerating, and trillions in infrastructure investment justified by unproven benefits. The same standards of transparency and evidence-based claims applied to pharmaceutical companies and environmental consultants should apply to tech companies making climate assertions.

What's needed is straightforward: require specific mechanisms, quantified impacts with confidence levels, peer-reviewed research, and transparent methodologies. This isn't anti-innovation; it's pro-honesty. AI might genuinely contribute to solving climate problems, but only if we're serious about understanding its actual impact rather than accepting its theoretical potential as fact.

Related Articles

- EPA Revokes Greenhouse Gas Endangerment Finding: What It Means for Climate Policy [2025]

- Trump's EPA Kills Greenhouse Gas Regulations: What It Means [2025]

- How Tem Is Remaking Electricity Markets With AI [2025]

- New York's AI Regulation Bills: What They Mean for Tech [2025]

- DOE Climate Working Group Ruled Illegal: What the Judge's Decision Means [2025]

- Thermodynamic Computing: The Future of AI Image Generation [2025]

![AI Climate Claims: Big Tech's Promises vs. Reality [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/ai-climate-claims-big-tech-s-promises-vs-reality-2025/image-1-1771428977497.jpg)