Why the UK Government's Electric Car Campaign Misses the Mark

Last month, the UK government launched a splashy campaign telling people to buy electric cars right now. The messaging was simple: go electric, save money, help the planet. Everyone wins.

Except, not really.

I've been tracking the EV adoption conversation across the UK for years, and here's what frustrates me most: the government's campaign focuses entirely on the benefits while completely sidestepping five massive problems that directly affect whether millions of people can actually make the switch. This isn't a criticism of the EV transition itself—I'm convinced it's necessary. But the government's approach? It's incomplete, and it's leaving real people stuck.

The disconnect is significant. You've got ministers talking about falling battery prices and improved range, while actual drivers are wrestling with three-hour charging waits, installation nightmares, and whether they can afford an EV when the cheapest options still cost £20,000+. Those aren't minor complaints. They're the difference between someone buying an EV this year versus waiting five years until the problems actually get solved.

Let me walk you through exactly what the government isn't addressing, and why these obstacles matter more than the promotional messaging suggests.

TL; DR

- Charging infrastructure remains underfunded and unevenly distributed, with rural areas significantly underserved despite government pledges

- Upfront costs remain prohibitive for middle-income earners, with average EV prices 40-50% higher than equivalent petrol vehicles

- Grid capacity concerns are being minimized despite projections showing the UK grid could struggle with rapid EV adoption

- Home charging installation barriers create a two-tier system favoring homeowners while disadvantaging renters and apartment dwellers

- Battery supply chain vulnerabilities and material dependencies create geopolitical risks the government downplays

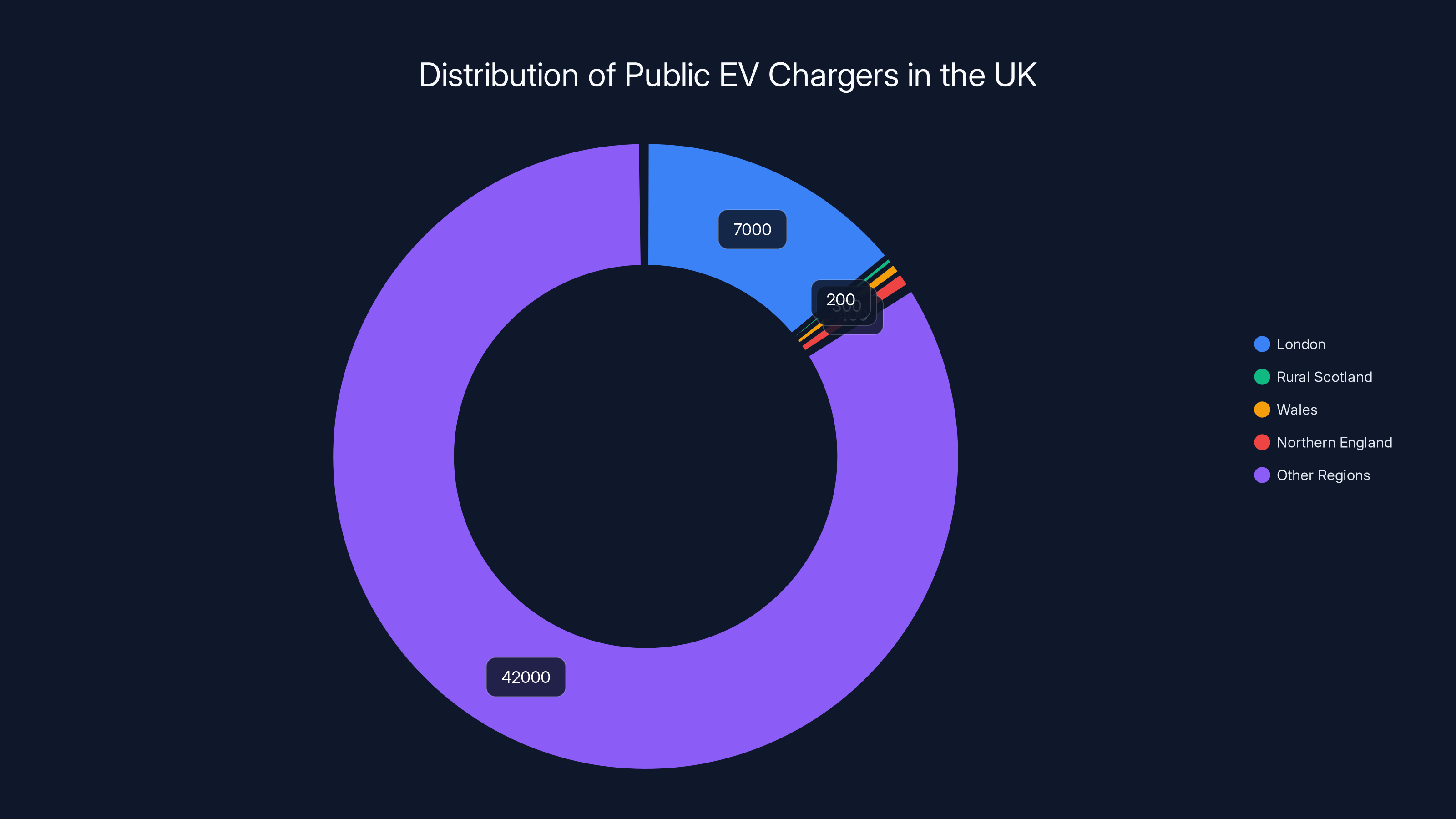

The majority of the UK's 50,000 public EV chargers are concentrated in urban areas like London, leaving rural regions underserved. Estimated data.

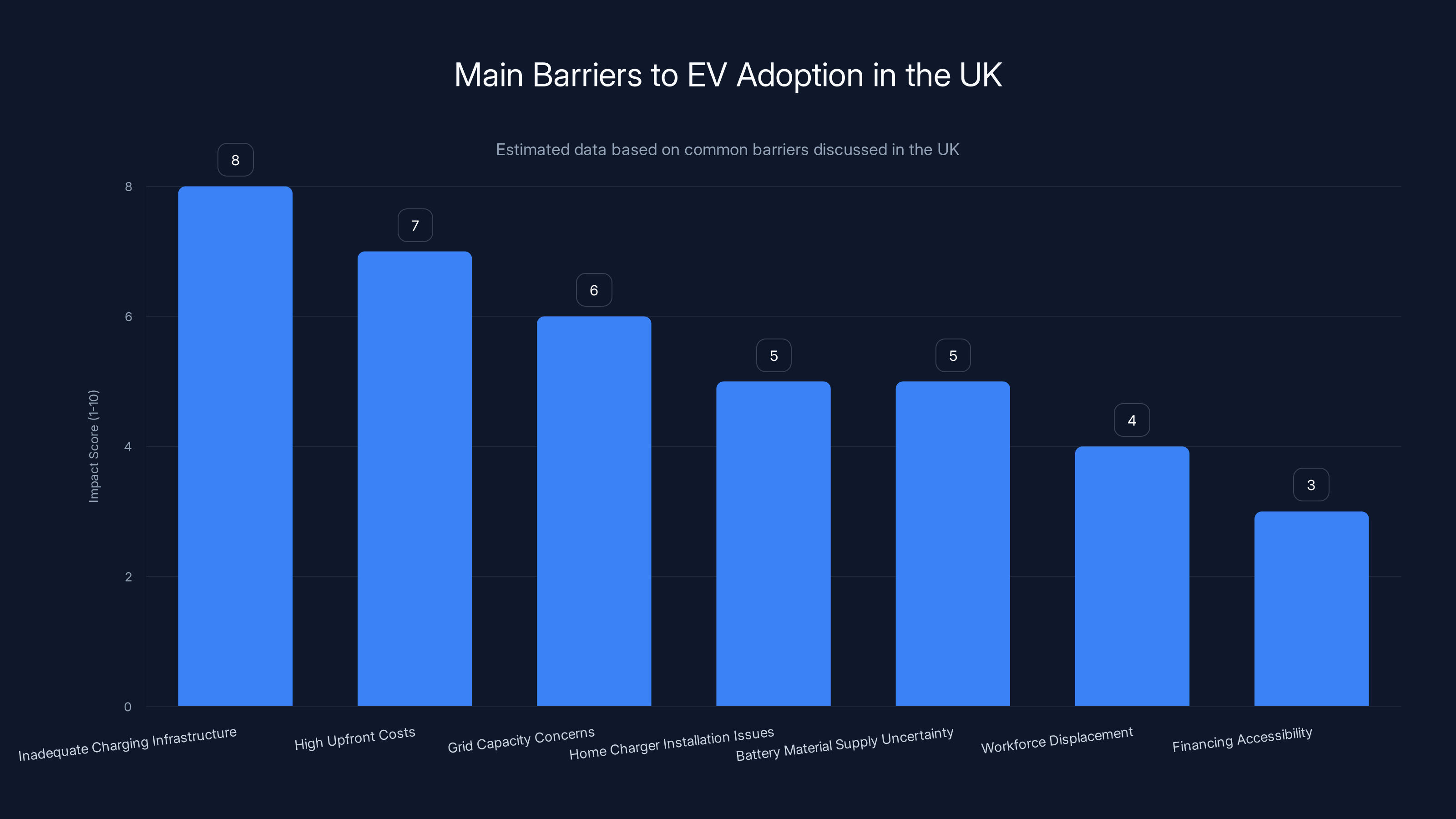

The Charging Infrastructure Myth: Abundance in Theory, Scarcity in Reality

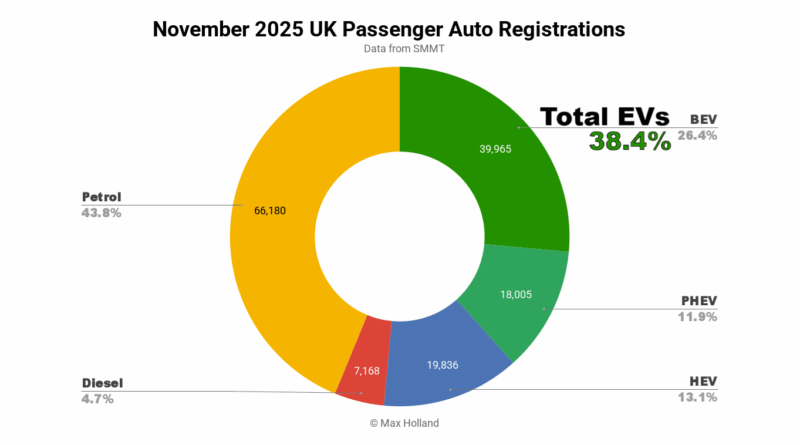

The government's official position on charging infrastructure is technically accurate but misleading. They'll tell you the UK has over 50,000 public charging points spread across the country. That sounds impressive until you start examining what that actually means for someone trying to own an EV.

Here's the reality: the distribution is wildly uneven. London has approximately 7,000 public chargers. Meanwhile, rural areas in Scotland, Wales, and Northern England are desperately underserved. I spoke with someone from rural Aberdeenshire last year who counted exactly four rapid chargers within 45 minutes of their home. Four. For a region with hundreds of thousands of people.

The charging network also suffers from what I call the "Schrödinger's charger" problem: the charger exists, but it's broken, occupied, or running proprietary software you don't have access to. According to industry estimates, approximately 20-30% of public chargers are out of service at any given time due to maintenance issues, vandalism, or software glitches. That's not an edge case—that's a structural problem that directly reduces the effective charging network by nearly a third.

Different charger networks, different standards. Shell Recharge, BP Pulse, Insta Volt, Tesla Supercharger Network—they're not all compatible with all cars. You might pull up to a rapid charger only to discover your vehicle doesn't support that network's payment system. Yes, various apps can consolidate access, but the complexity discourages adoption.

Rapid chargers (350k W and above) are concentrated on motorways and major urban routes. If you're taking a cross-country trip from Edinburgh to Cornwall, finding a network of chargers that all work with your vehicle becomes a logistics puzzle. For someone used to pulling into any petrol station anywhere in the UK, this is a massive step backward in convenience.

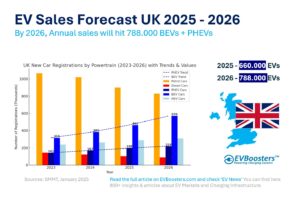

The government pledged £2.5 billion for charging infrastructure. Sounds substantial until you realize the plug-in car market is growing at roughly 13% annually. That funding might be adequate for the current EV fleet, but it's not enough to support the network that would be required if the government's own targets are hit (50% of new car sales electric by 2030). Analysts estimate you'd actually need £4-5 billion minimum to create a truly sufficient network by 2035.

Inadequate charging infrastructure and high upfront costs are the most significant barriers to EV adoption in the UK, with impact scores of 8 and 7 respectively. (Estimated data)

The Cost Barrier: "Affordable" Doesn't Mean What the Government Says

The government's line on EV pricing is that costs are dropping and EVs are becoming competitive with petrol cars. This is true—eventually. But "eventually" doesn't help you today.

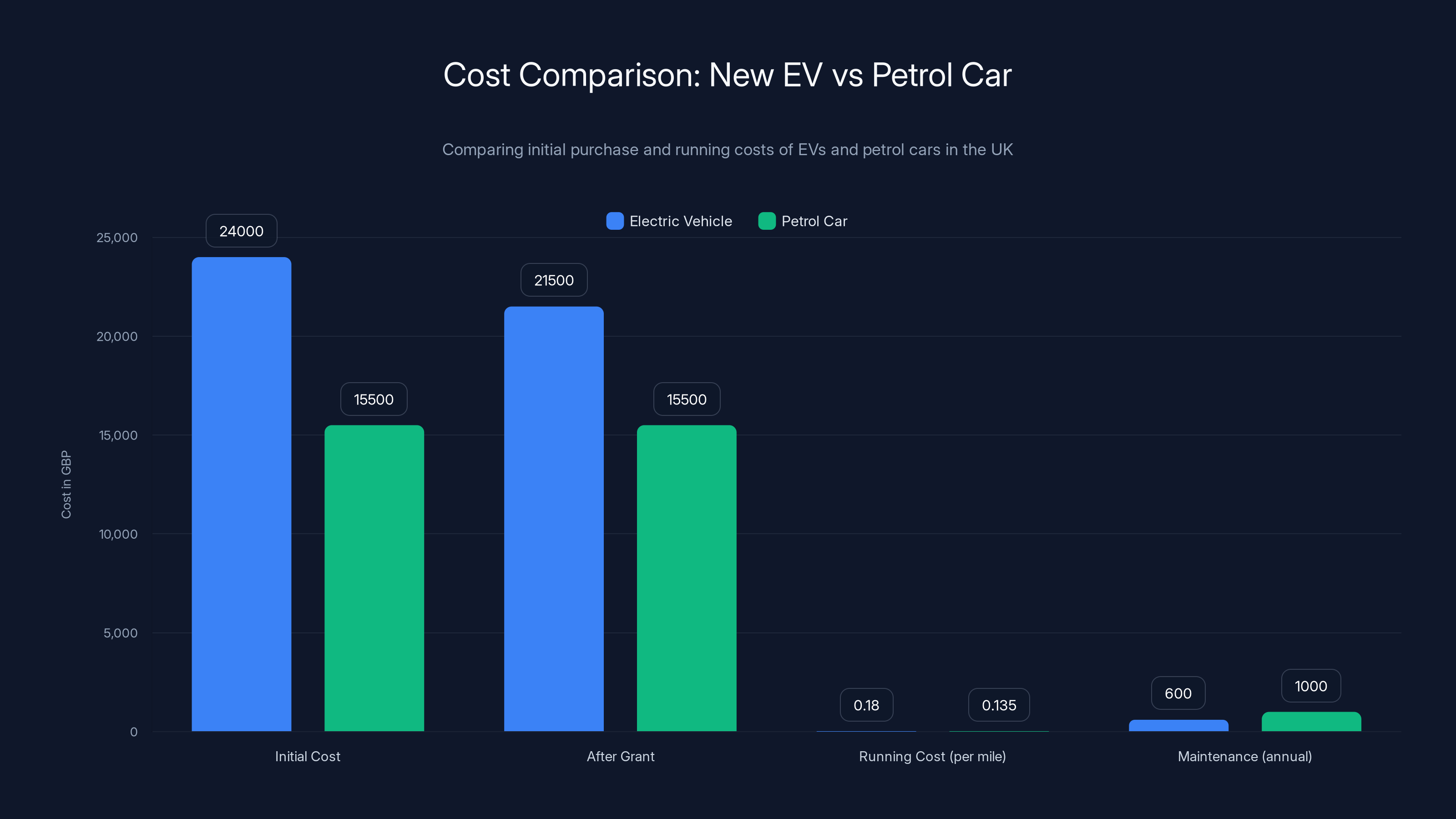

Let's talk actual numbers. The cheapest brand-new EV available in the UK right now is the Renault 5 E-Tech at around £24,000. The cheapest new petrol hatchback (something like a Vauxhall Corsa) is around £15,000-16,000. That's a £8,000-9,000 premium for the EV. For most households, an additional £8,000-9,000 is not a trivial amount.

Yes, the government offers the Plug-in Car Grant, which provides up to £2,500 off eligible vehicles. That helps, reducing the gap to £5,500-6,500. But government grants aren't available for all EVs (they phase out as prices drop), and £5,500 is still a significant barrier for budget-conscious buyers.

The second-hand EV market helps, but it's underdeveloped compared to petrol. A 3-year-old EV typically costs 45-55% of its original purchase price, whereas a used petrol car in the same condition sits at 55-65% of original value. EVs depreciate faster, which is good for buyers but signals they're still not perceived as equally reliable long-term investments.

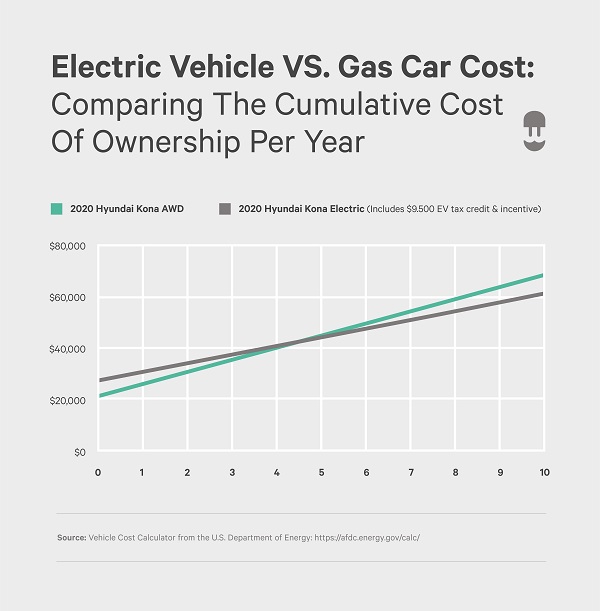

Running costs do favor EVs, and this is where the government's messaging has some teeth. Electricity costs approximately £0.15-0.20 per mile (depending on your tariff and charging efficiency), while petrol runs £0.12-0.15 per mile. The advantage narrows as fuel prices fluctuate, and it depends heavily on when you charge (off-peak rates save money). For high-mileage drivers (15,000+ miles annually), EVs make financial sense over five-plus years. For someone driving 8,000 miles annually, the math becomes much tighter.

Maintenance costs genuinely are lower for EVs. No oil changes, fewer moving parts, brake pads last longer due to regenerative braking. Real savings: £400-800 annually depending on the vehicle. Good news for owners, but this advantage only emerges over time and doesn't help someone struggling with the upfront purchase price.

The government could address this by expanding subsidies, but that requires political will and budget allocation. They've instead chosen to highlight falling battery costs and improve manufacturing volumes—both true, both happening, but both too slow to help someone right now who needs a car and can't justify the premium.

Grid Capacity: A Crisis Hiding in Plain Sight

The government's narrative on grid capacity is dangerously optimistic. They'll tell you the grid can handle the transition. National Grid's own reports suggest there's no systemic issue. And technically, they're not wrong—if everything goes perfectly.

The problem is "if everything goes perfectly" is a pretty thin plan for infrastructure transformation.

Here's the challenge: the UK's electricity grid was designed for relatively flat demand patterns. Cars were a transportation problem, not an electricity problem. Now suddenly, you're asking millions of households and businesses to plug multi-ton batteries in simultaneously, mostly between 5 PM and midnight when people return home from work and start charging.

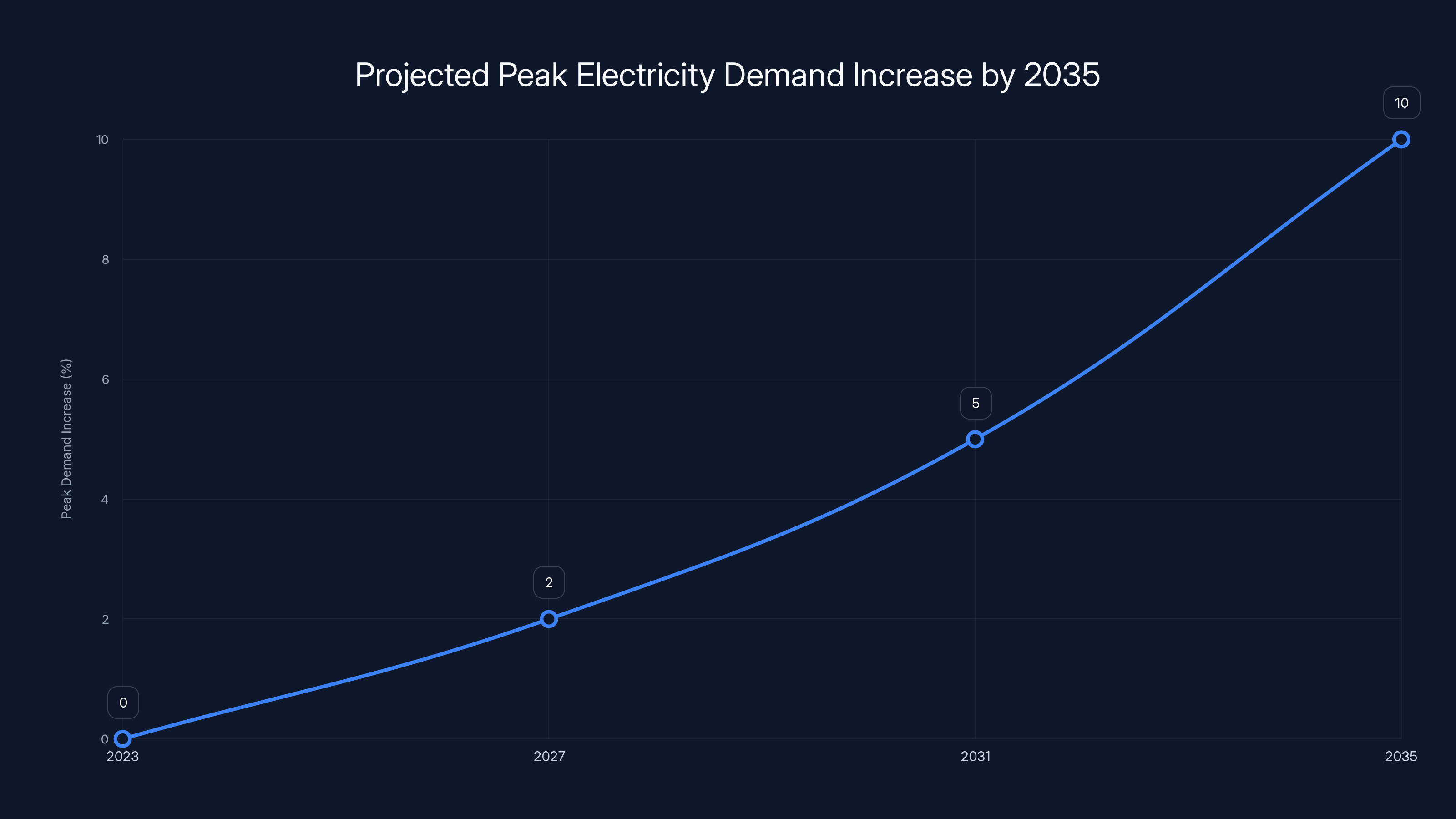

The peak demand spike is real. National Grid models suggest that if EV adoption reaches 50% of vehicles by 2035, peak electricity demand could increase by 5-10% during evening hours. That doesn't sound catastrophic until you realize that this peak would coincide with normal evening demand from heating, cooking, lighting, and entertainment. Cold winter nights would be particularly stressed.

The grid can theoretically manage this through "smart charging"—software that spreads charging demand across off-peak hours by automatically starting charges at midnight when demand is low. Beautiful concept. Real-world adoption? Nowhere near the penetration required. You need vehicle participation rates of 70%+ for smart charging to work at scale, and we're currently at single-digit percentages.

Alternatively, the grid upgrades. Installing new generation capacity, upgrading distribution infrastructure, replacing aging transformers, installing smart metering systems. This is expensive. Estimates run £20-30 billion for adequate grid upgrades by 2035. This cost isn't included in government price tags for EV transition because it's technically a National Grid responsibility, not a government Department for Transport responsibility. It's a classic example of institutional boundary-passing.

Renewables add another layer of complexity. The government's plan assumes increasing renewable generation (wind and solar). But wind and solar are intermittent. You can't charge a million cars at 6 PM if the sun's already down and the wind isn't blowing. Battery storage helps, but the UK's grid-scale battery storage capacity is currently inadequate to buffer intermittency at the scale required for rapid EV adoption. It's another multi-billion-pound investment that's underestimated in the official narrative.

Electric vehicles have a higher initial cost even after grants, but offer savings in running and maintenance costs. Estimated data.

Home Charging Installation: A Bureaucratic Nightmare That Disadvantages Millions

EV advocates will tell you that home charging is the ultimate solution—charge overnight, wake up with a "full tank," avoid public chargers entirely. This works beautifully if you own a detached house with a driveway.

If you're renting, live in a flat, or have on-street parking? The dream collapses immediately.

Approximately 32% of UK households are renting properties, not owner-occupied. For renters, installing a dedicated EV charger requires landlord permission, and landlords have limited incentives to approve. Installation costs run £400-2,000 depending on existing electrical infrastructure. The landlord bears the cost or the tenant does, but it's a significant expense for something you might lose if you move.

Apartment buildings and flats present even thornier problems. A typical building might have parking spaces but no feasible way to run electrical conduits to each space without significant structural work. The costs compound exponentially—you need new electrical panels, cabling, installation permits, building work, and coordination across multiple unit owners. It's technically possible but practically nightmarish.

On-street parking adds another layer of complication. The UK has an estimated 12-15 million on-street parking spaces, many in residential areas where cars are parked outside properties, not on dedicated driveways. Retrofitting these streets with charging infrastructure requires planning permission, coordination with local councils, structural work under roads, and electrical upgrades. It's expensive, time-consuming, and most local councils don't have budgets allocated for this scale of work.

The government's workaround is to encourage public rapid chargers. But as we've established, these don't provide the convenience of home charging, and they're expensive to use compared to off-peak electricity rates. A rapid charger session costs £8-12 for a 30-minute charge, whereas home charging costs £1.50-3.00 for the same energy. You're paying 5x more for the privilege of not being at home.

The government could mandate that new buildings include EV charging infrastructure, but only recently introduced guidance (not requirements) that new buildings should have charge points or conduits. They could fast-track planning permission for residential charging installations, but haven't. They could subsidize apartment building upgrades, but haven't allocated that budget.

What they have done is acknowledge the problem exists while shifting responsibility to local councils, landlords, and individuals. That's not a solution—it's an abdication.

Battery Supply Chain Vulnerability: Geopolitical Dependency Nobody Talks About

The government will highlight that battery prices have dropped 89% over the last decade and battery production is ramping up. Both true. What they won't discuss in depth is that battery production depends on resource supply chains that are geopolitically vulnerable and environmentally problematic.

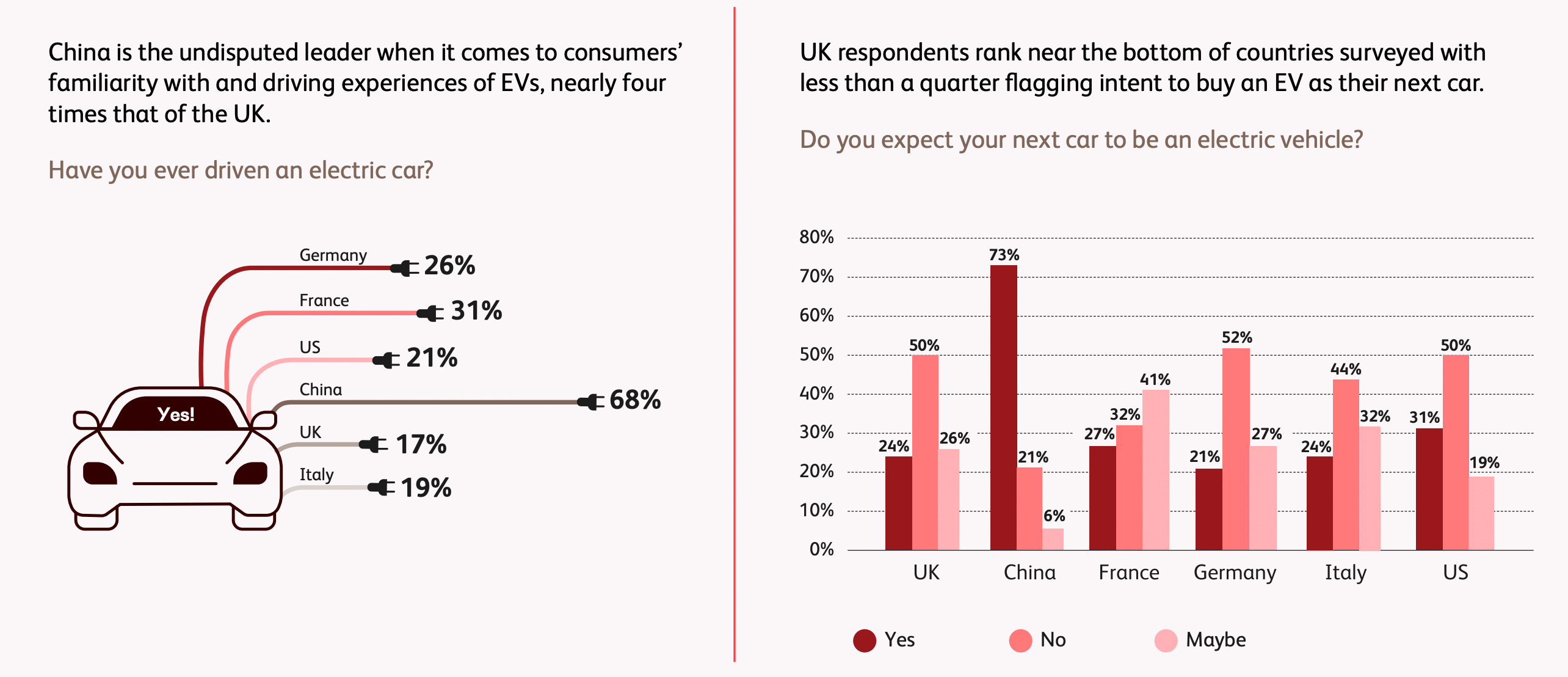

EV batteries require lithium, cobalt, nickel, and manganese. The geographic concentration is severe: China controls approximately 60% of global lithium refining capacity, 70% of cobalt processing, and 85% of rare earth minerals. That's not a supply chain; that's a geopolitical hostage situation.

Lithium sources are geographically concentrated in Chile (28% of global production), China (13%), and Australia (50%). If any major producer has a supply disruption, battery prices spike. We saw this in 2021-2022 when battery prices increased 40-50% due to supply chain disruptions and demand surges. The government's cost-reduction projections assume stable supply. That's a risky assumption.

Cobalt is even more concentrated. About 70% of global cobalt production occurs in the Democratic Republic of Congo, a country with serious governance and labor concerns. Battery companies are working to reduce cobalt dependency, but current-generation batteries still require it. The ethical implications complicate the environmental narrative—is an EV truly "green" if it depends on cobalt mined in exploitative conditions?

The government's strategy is to hope alternatives emerge (lithium-iron-phosphate batteries, solid-state batteries) before dependency becomes critical. Maybe that works, maybe it doesn't. Hoping isn't a strategy; it's wishful thinking.

Alternatively, they could invest heavily in recycling infrastructure to reclaim battery materials from retired EVs, reducing raw material dependency. Currently, UK battery recycling capacity is minimal. Of the estimated 10,000-15,000 EV batteries that need recycling annually (number growing rapidly), most are either exported or stuck in temporary storage because recycling infrastructure is underfunded. The government has pledged to address this, but investment timelines lag adoption rates.

The domestic EV manufacturing story also depends on these supply chains. The government touts UK EV manufacturing (Nissan in Sunderland, Vauxhall in Ellesmere Port, Jaguar Land Rover in the Midlands) as a success story. It is, but it's entirely dependent on imported battery cells or raw materials. Building complete battery manufacturing capacity in the UK would require years and billions of pounds of investment. The government hasn't committed to that scale of investment.

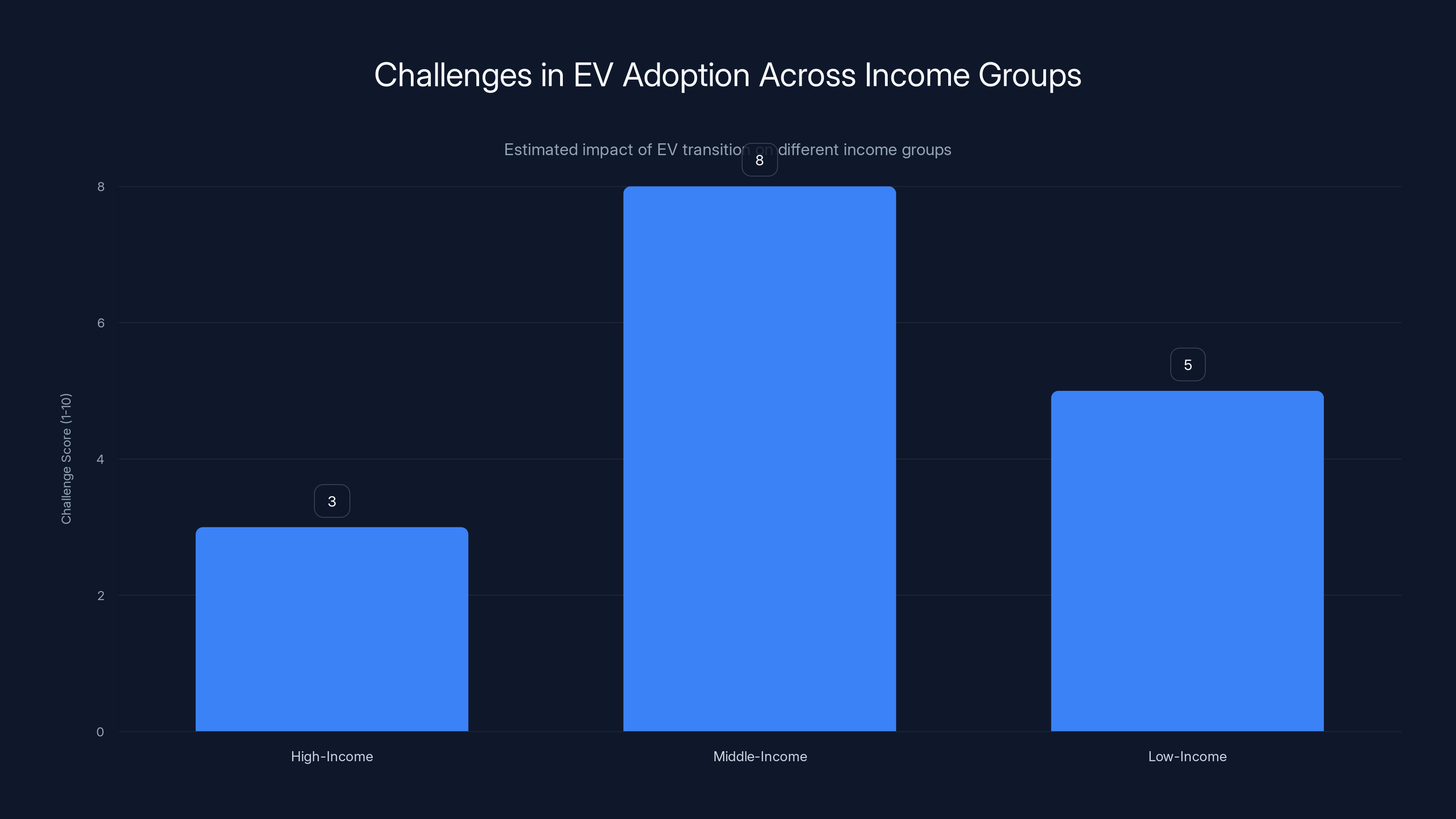

Middle-income households face the greatest challenges in transitioning to EVs, with a high challenge score of 8 out of 10, due to financial constraints and limited access to charging facilities. Estimated data.

The Middle-Income Squeeze: Why the Transition Leaves Working People Behind

There's an uncomfortable class dimension to EV adoption that the government's campaign glosses over entirely.

High-income households (£80,000+ annually) can absorb the upfront EV cost premium, have homes with dedicated driveways, and can access workplace charging. For them, transitioning to an EV is relatively straightforward. They benefit from lower running costs and avoid petrol price volatility.

Low-income households qualify for government support programs, car-sharing schemes in urban areas, and in some cases, subsidized public transport. It's not easy, but there are pathways and support mechanisms.

Middle-income households (£35,000-70,000 annually) are squeezed hardest. They can't easily absorb an £8,000-9,000 premium on a new car. They often live in terraced houses with on-street parking, making home charging installation a nightmare. They're above the threshold for maximum government subsidies but not wealthy enough to absorb the financial risk. They have commutes that require reliable cars but are priced out of the EV market.

For these households, the government's message ("buy an EV now") translates to either: make a financially risky purchase, delay car replacement (risking mechanical failure), or buy a used EV (and accept unknown battery health). None of those are ideal.

The transition timeline exacerbates this. The government's stated goal is to phase out new petrol car sales by 2030 (later revised to 2035). That's 10 years away, but the pressure is building now. If you're a middle-income earner needing a new car in 2025-2026, you're facing a choice between overpaying for an immature technology or buying a petrol car that will be increasingly unpopular and potentially harder to resell in 5-7 years.

The government could address this by expanding subsidies, but that's politically expensive. They could accelerate job retraining programs for the petrol and diesel automotive service sector (garages, mechanics, parts suppliers), but that's a multi-billion-pound commitment over years. They could focus on public transport and car-sharing to reduce the need for private vehicle ownership, but that requires long-term urban planning and investment that contradicts short-term construction interests.

Instead, the campaign tells middle-income people to buy EVs now, without acknowledging the financial squeeze or providing realistic solutions.

Rural Isolation: Why EV Adoption Stalls Outside Major Cities

EV adoption rates correlate strongly with population density. Urban areas have higher EV penetration; rural areas lag significantly. This isn't coincidental—it's structural.

Rural driving patterns are fundamentally different from urban driving. Someone in London might make 5-10 short trips daily with commutes of 2-3 miles. Someone in the Scottish Highlands makes longer, less frequent trips with wider geographic spread. A 20-mile trip to the nearest supermarket is routine. That drives different vehicle requirements.

EVs are optimized for short-to-medium range (150-300 miles typical), frequent charging, and urban lifestyles. Rural drivers need range, reliability, and confidence that they won't get stranded. The charging anxiety that EV advocates dismiss as psychological is actually logical for someone living 30 miles from the nearest rapid charger.

The economics also disadvantage rural areas. Installing charging infrastructure in densely populated urban areas makes financial sense: high utilization rates, sufficient traffic to justify the investment. Installing chargers on rural roads serves fewer vehicles, operates at lower utilization, and generates insufficient revenue to justify the capital cost. Private companies won't invest there; government subsidies don't yet.

Rural residents also tend to own property (higher homeownership rates than urban areas), suggesting home charging installation should be easier. But rural electrical infrastructure is often older, with smaller distribution networks and higher costs for upgrades. Installing a 7k W home charger in a semi-rural location might cost £1,500-3,000 instead of £700-1,200 in urban areas due to electrical panel upgrades and longer cable runs.

The government's campaign makes no distinction between urban and rural contexts. Same message everywhere: buy an EV. But the feasibility is wildly different.

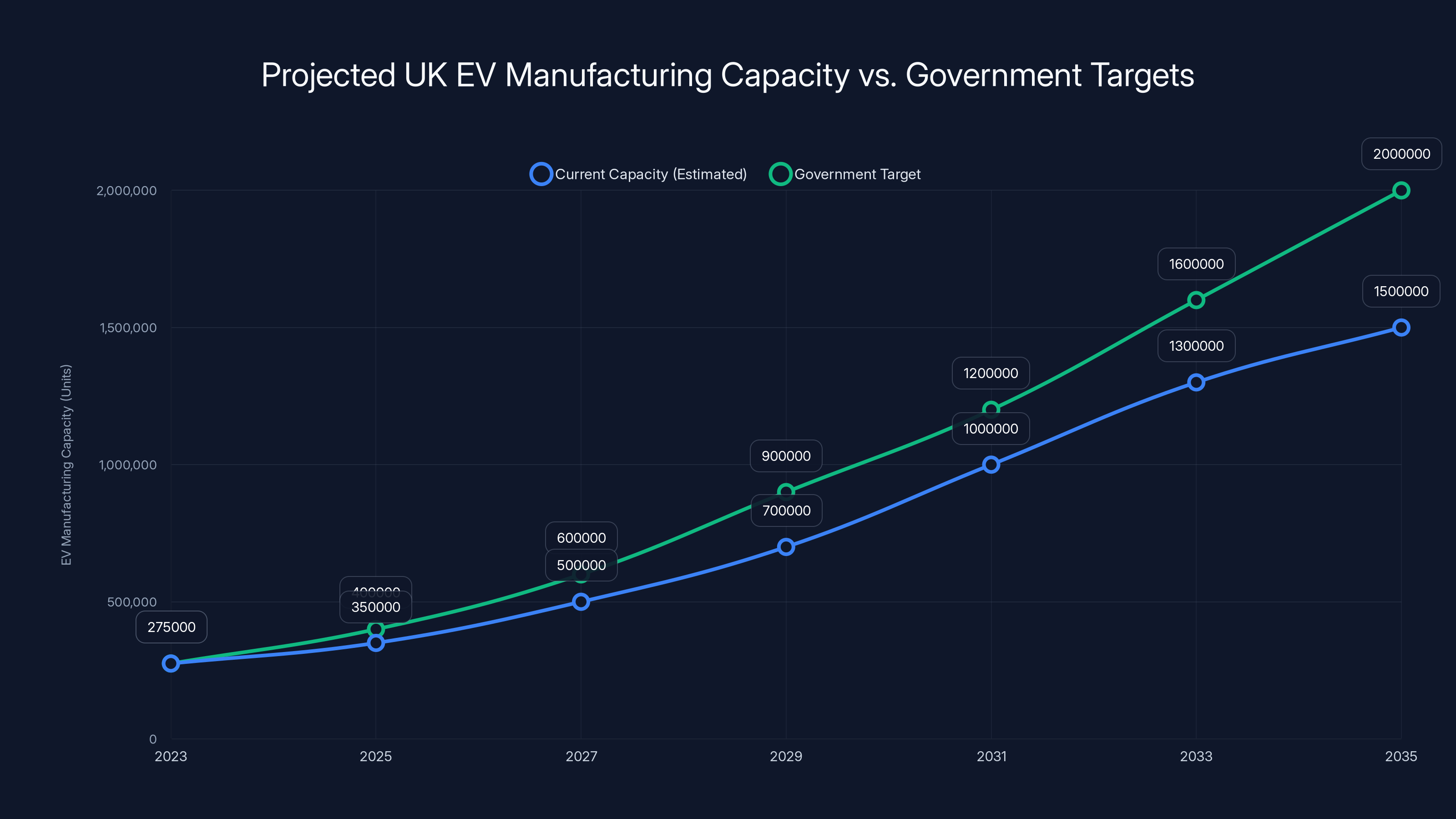

To meet the 2035 target of 100% new EV sales, UK manufacturing capacity must increase 5-7x. Current growth projections fall short, indicating a significant gap unless investment accelerates. Estimated data.

The Workforce Transition That Nobody's Preparing For

Here's something the government definitely isn't discussing: the employment impact of shifting from petrol/diesel manufacturing to EV manufacturing.

The UK automotive industry directly employs about 159,000 people, with another 800,000+ in supply chains (parts manufacturers, logistics, distribution). A massive portion of these jobs depend on technologies that are being eliminated: internal combustion engines, transmission systems, fuel injection, exhaust systems.

EV manufacturing requires fewer people and different skills. An EV motor is simpler than a petrol engine. A single-speed gearbox (common in EVs) requires fewer components than a multi-speed transmission. Battery packs are manufactured by specialized companies, often overseas. Wiring and software are different skills.

The result? Job losses in traditional automotive manufacturing. The government assumes new jobs in EV manufacturing, battery production, and recycling will replace them. Maybe they will, eventually. But there's a transition period of 5-10 years where workers face retraining, potential relocation, and earning uncertainty.

The government's response has been tepid. Some retraining programs exist, but they're limited in scope and poorly funded compared to the scale of potential job losses. Car manufacturing in the Midlands, North West, and Wales faces particular vulnerability. These regions don't have strong alternative employment clusters to absorb displaced workers.

Geographic inequality will likely increase. London and South East (where automotive manufacturing is minimal) won't feel the employment impact. Sunderland, Liverpool, and the Midlands will feel it acutely. The government's EV campaign doesn't acknowledge this, let alone propose solutions.

Manufacturing Timeline Mismatches: When Policy Outruns Reality

The government's transition timeline assumes rapid scaling of EV manufacturing and battery production in the UK. The reality is messier.

Current UK EV manufacturing capacity is approximately 250,000-300,000 units annually across all manufacturers. To hit the government's targets (100% of new sales electric by 2035), you'd need capacity to reach 1.5-2 million units annually by that date. That's a 5-7x increase in manufacturing capacity in a decade.

Investment is happening, but it's slower than required. Nissan invested £1 billion in the Sunderland plant to begin Qashqai EV manufacturing. Good news, but that covers one facility, one model. The scale-up is real but incremental.

Battery manufacturing is even more constrained. Current UK battery cell production capacity is negligible (a single production facility planning to start operations in 2025). To support domestic EV manufacturing without massive imports, you'd need 3-5 major battery cell factories, each requiring £3-5 billion in capital investment and years to build and ramp production.

The government has announced some battery manufacturing support (through mechanisms like grants and accelerated planning permission), but it's insufficient to build the required production capacity by 2035. You're relying either on imports (particularly from China, bringing back the geopolitical vulnerability issue) or a massive gap between government targets and actual EV availability.

Projected data shows a potential 10% increase in peak electricity demand by 2035 due to EV adoption, stressing the need for grid upgrades or smart charging solutions. Estimated data.

The Government's Financing Blind Spot

The campaign emphasizes the financial benefits of EV ownership (lower running costs, tax advantages) but ignores the financing accessibility problem.

For someone with perfect credit and stable employment, getting an auto loan for an EV is straightforward. For someone with imperfect credit history, irregular income, or a recent negative event (job loss, medical issue), financing an expensive vehicle is far more difficult.

That's not unique to EVs, but it becomes more pronounced when EVs are more expensive. A £25,000 EV loan requires stronger creditworthiness than a £16,000 petrol car loan. The people most likely to benefit from lower operating costs (high-mileage drivers in lower-income brackets) are also most likely to struggle with the upfront financing.

The government could address this through dedicated EV financing programs with lower interest rates or more flexible lending criteria, similar to programs in some other countries. They haven't. Instead, they've left financing to the private market, where competition is limited and rates reflect elevated risk for lower-credit-score borrowers.

What Actually Needs to Happen (But Won't Fit in a Campaign Poster)

I'm not anti-EV. I think electric vehicles are necessary and inevitable. But the government's campaign presents a false choice: adopt EVs now or ignore environmental responsibility. The reality is more nuanced.

A realistic EV transition would require:

-

Tripling charging infrastructure investment to £6-8 billion and focusing on rural deployment, apartment buildings, and destination charging. This means shifting from flashy motorway rapid chargers to unglamorous street-level infrastructure.

-

Expanding subsidies for 5-7 more years to help middle-income buyers absorb the upfront cost premium. This is politically expensive and requires budget reallocation from other areas.

-

Mandating home charging installation support for renters and apartment dwellers through either landlord subsidies or fast-track planning permission. This creates friction with property owners.

-

Investing in grid infrastructure upgrades (£20-30 billion) explicitly and transparently, rather than assuming the private sector will figure it out. This requires treating electricity infrastructure as critical national infrastructure.

-

Building domestic battery manufacturing capacity at scale, requiring £10-15 billion in capital investment and years of preparation. This competes with other infrastructure priorities.

-

Establishing comprehensive battery recycling infrastructure, funded by government and operating at scale. Currently, it's an afterthought.

-

Creating robust workforce retraining programs for automotive sector workers, funded at hundreds of millions of pounds and coordinated across regions.

-

Implementing demand management (limiting peak charging through smart charging requirements) as a condition of EV ownership, rather than assuming the grid will adjust.

None of these require killing the EV transition. They require acknowledging the transition is genuinely difficult and expensive, and building coherent policy around that reality.

Instead, the government's campaign amounts to: "Buy an EV. Trust us, everything will work out." That's not strategy. It's hope dressed up as policy.

The Elephant in the Room: Alternative Fuels Get Short Shrift

Here's what gets minimally discussed: EVs aren't the only low-carbon mobility option. Hydrogen fuel cell vehicles, advanced biofuels, synthetic fuels—these exist and are being developed. They come with their own challenges and timelines, but so do EVs.

The government's bet is heavily on battery electric vehicles. That might be right, but it's essentially a single-technology bet. If battery supply chains face critical disruptions (which is possible given current material sourcing), or if manufacturing capacity doesn't scale as projected (also possible), you're left without backup options.

A more balanced approach would develop multiple pathways in parallel. Invest in EV infrastructure while simultaneously supporting hydrogen fuel cell manufacturing, next-generation synthetic fuel production, and battery recycling. This hedges risk and provides options if one pathway encounters unexpected obstacles.

Instead, policy has converged on EVs as the de facto solution, with minimal investment in alternatives. It's not necessarily wrong, but it's a fragile bet to make unilaterally.

The Insurance and Infrastructure Repair Gap

Another issue the government hasn't adequately planned for: as EV penetration increases, insurance companies, repair shops, and roadside assistance providers need to adapt.

EV insurance is currently more expensive than petrol car insurance (higher repair costs for specialized electric components, less competitive market), and fewer repair shops are equipped to handle EV maintenance and repairs. If you're unfortunate enough to need a battery replacement (costs £5,000-15,000 depending on damage severity), availability becomes a problem.

Roadside assistance coverage for EVs is less standardized. Recovery of a broken-down EV is more complex than towing a petrol car—specialized equipment is needed. Coverage varies significantly by provider.

As EV ownership increases, these issues should resolve through market adaptation. But during the transition period, they create friction and hidden costs that the government's campaign doesn't acknowledge.

Where the Government Got It Partly Right

To be fair, the government's EV campaign isn't entirely wrong. A few points are legitimately strong:

Battery costs are genuinely falling. The cost per k Wh of battery capacity has dropped from ~£1,000 in 2010 to ~£110 in 2024. This trajectory is real and will continue. Eventually, EVs will be cost-competitive without subsidies.

Environmental benefits are real (assuming electricity grids continue decarbonizing, which they're on track to do). Even accounting for manufacturing emissions, EVs have lower lifetime carbon footprints than petrol cars.

Technology is improving. Range anxiety will diminish as battery capacity increases and charging speeds improve. The next generation of EVs will genuinely be more practical than current models.

Early adopter benefits are real. If you own a home with a driveway, drive primarily urban routes, and can absorb the upfront cost, transitioning to an EV makes genuine sense today. These people exist, and they're making the transition.

The problem isn't that any of these points are false. The problem is that the government presents them as universally true without acknowledging the context and conditions required for them to apply.

Why the Messaging Matters (More Than You Might Think)

You might think: "Okay, the campaign's simplistic, but doesn't matter if people ignore it and make decisions based on their actual circumstances?"

Unfortunately, messaging affects policy more than most people realize. If the government publicly claims EV adoption is simple and unproblematic, they face political pressure to cut funding for charging infrastructure ("the private sector will handle it"), housing reform ("home charging isn't a blocker"), or workforce retraining ("new jobs will emerge naturally").

The oversimplified campaign becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy of inadequate support, which then makes EV adoption harder, which creates public frustration, which feeds political opposition to the entire EV transition.

A more honest campaign would say: "Electric vehicles are necessary for climate targets. The transition is complex and will require substantial investment in infrastructure, training, and support. We're committed to making it work." It's less catchy. It wouldn't fit on a billboard. But it would set realistic expectations and build support for the investments actually required.

The Comparison Problem: Everyone's Watching Norway

Government officials love pointing to Norway as proof that rapid EV adoption is possible. Norway has roughly 90% of new car sales being electric. They did it in 15 years. Surely the UK can do the same?

The problem is that Norway's context is wildly different:

- Electricity supply: Norway gets 60% of electricity from hydroelectric power, giving it abundant, cheap, renewable electricity. The UK gets ~30% from renewables and still relies on gas.

- Charging infrastructure: Norway's population density is lower, but EV adoption was so early that charging infrastructure developed alongside demand. The UK is playing catch-up with existing car population patterns.

- Geography: Norway's long distances and limited fuel competition (few petrol stations in rural areas) made EVs necessary. The UK's dense road network and ubiquitous petrol stations gave petrol cars a built-in advantage.

- Wealth: Norway's sovereign wealth fund (from oil revenues, ironically) funded EV subsidies and infrastructure. The UK's government faces tighter budgets.

- Home charging: Norway's high homeownership rates and abundance of housing with driveways made home charging adoption easier.

The UK might reach 50% EV adoption by 2035, but reaching Norway's 90% by 2040 is substantially harder without acknowledging these contextual differences.

FAQ

What are the main barriers to EV adoption in the UK?

The primary barriers include inadequate charging infrastructure (particularly in rural areas), high upfront costs despite falling battery prices, concerns about grid capacity during peak demand, difficulty installing home chargers for renters and apartment dwellers, and uncertainties around battery material supply chains. Additionally, workforce displacement in the automotive sector and financing accessibility for lower-credit-score buyers create structural obstacles that the government's campaign doesn't address.

How long does it take to charge an electric vehicle?

Charging time varies dramatically based on charger type and battery size. Home chargers (7-11k W) take 8-16 hours for a full charge. Fast chargers (22-50k W) require 2-4 hours. Rapid chargers (150-350k W) can add 80% charge in 20-30 minutes. The government often highlights rapid charging times to justify public charging investment, but rapid chargers are expensive to use (£8-12 per session) compared to home charging (£1.50-3.00).

What is the true cost of owning an electric vehicle?

Total cost of ownership includes purchase price, electricity costs, maintenance, insurance, and residual value. An average EV costs £20,000-35,000 to purchase (after accounting for government grants). Electricity costs run approximately £0.15-0.20 per mile. Maintenance costs are 30-40% lower than petrol cars. Insurance is currently 10-15% higher due to specialized repair requirements. Break-even compared to petrol cars typically occurs around 4-5 years of ownership, depending on electricity rates and driving patterns. The government's campaign emphasizes the long-term savings without adequately highlighting the upfront financial burden.

Are public charging networks reliable enough for daily use?

Public charging networks have significant reliability issues. Approximately 20-30% of public chargers are out of service at any given time due to maintenance, vandalism, or software problems. Different charging networks use different payment systems and connectors, requiring drivers to manage multiple apps and memberships. Coverage is heavily concentrated in urban areas and motorway routes, with poor coverage in rural regions. For daily reliance, home charging is vastly preferable—but that option is unavailable to roughly one-third of UK households.

How does the UK grid handle millions of electric vehicles?

The grid's capacity to handle mass EV adoption depends on smart charging systems that shift demand to off-peak hours (typically 11 PM to 6 AM). However, current smart charging adoption is minimal—fewer than 5% of EV owners use smart charging systems. Without widespread adoption, peak evening demand could increase 5-10% during winter months, creating bottlenecks. The grid requires £20-30 billion in infrastructure upgrades to comfortably accommodate targets, but the government hasn't transparently addressed these costs or timelines.

Where do EV battery materials come from, and is supply stable?

EV batteries require lithium, cobalt, nickel, and manganese. China controls 60-85% of processing capacity for these materials. Production is concentrated in Chile (lithium), the Democratic Republic of Congo (cobalt), and Indonesia (nickel). This geographic concentration creates geopolitical vulnerability—supply disruptions would spike battery prices. Additionally, cobalt mining raises ethical concerns regarding labor practices and governance. Battery recycling could reduce material dependency but requires substantial infrastructure investment the UK hasn't yet provided.

Can renters and apartment dwellers realistically own electric vehicles?

EV ownership is significantly more difficult for renters and apartment dwellers because home charging installation requires landlord approval and expensive electrical work. Apartment buildings face compounded challenges retrofitting charging infrastructure. Currently, these households must rely on public rapid chargers, which are expensive (£8-12 per charge) compared to home charging and concentrated in urban areas. The government hasn't mandated landlord support or subsidized apartment upgrades, effectively pricing out approximately one-third of UK households from practical EV ownership.

Why doesn't the government's campaign address rural EV adoption challenges?

Rural areas have different driving patterns (longer distances, less frequent trips) and infrastructure challenges (sparse charging networks, older electrical systems, higher installation costs). The government's one-size-fits-all messaging doesn't acknowledge these differences. Investment in rural charging infrastructure is economically unattractive to private companies due to lower utilization rates. Without dedicated rural funding, EV adoption will remain concentrated in urban areas, contributing to geographic inequality.

What employment impact will the EV transition create?

The automotive industry employs 159,000 directly and 800,000+ across supply chains. EV manufacturing requires fewer workers and different skills than internal combustion engine manufacturing. Job losses are expected during transition years, particularly in regions dependent on automotive manufacturing (Sunderland, Liverpool, Midlands). The government has not fully funded workforce retraining programs, risking employment disruption and regional inequality. New jobs in EV manufacturing and battery production will eventually emerge, but the timeline and geographic distribution are uncertain.

How much will charging infrastructure investment actually cost?

The government committed £2.5 billion to charging infrastructure, but industry analysts estimate £4-5 billion is required to support government EV targets by 2035. Additionally, grid upgrades (£20-30 billion), battery recycling facilities (£2-3 billion), and supporting charging at apartment buildings (£3-5 billion) add substantial costs not fully reflected in government planning. The total infrastructure investment required is likely £30-40 billion across electricity generation, distribution, charging networks, and recycling—a figure not explicitly discussed in public campaigns.

Will EV technology improve faster than government timelines assume?

Some improvements will outpace timelines (battery energy density, charging speed, manufacturing efficiency). Others will lag (affordable long-range vehicles, dense charging networks, grid integration). The government's campaign assumes a linear improvement trajectory, but technology development is unpredictable. Battery solid-state technology might revolutionize range and cost, or it might encounter manufacturing hurdles. Planning policy around optimistic technology assumptions is risky—a more cautious approach would extend timelines and build contingency funding for infrastructure gaps.

Conclusion: The Gap Between Campaign and Reality

The UK government's EV campaign is well-intentioned but fundamentally incomplete. It highlights genuine benefits (falling battery costs, improved range, lower running costs) while minimizing or ignoring substantial obstacles affecting millions of people.

I'm not arguing that the EV transition is a mistake. Climate change is real, transportation creates ~27% of UK emissions, and vehicles need to decarbonize. That's not debatable. What's debatable is whether the current campaign adequately prepares people for a complex transition or sets false expectations that ultimately undermine support for the required investments.

The uncomfortable truth is that EV adoption at the scale the government targets requires:

- Substantial public investment in unglamorous infrastructure (rural chargers, apartment building upgrades, grid capacity)

- Political willingness to expand subsidies, expanding government budgets

- Difficult conversations about housing, renting, and property ownership

- Transparent acknowledgment that the transition will displace workers and require retraining

- Long-term commitment to battery recycling infrastructure, supply chain development, and manufacturing

None of that fits on a campaign poster. None of it generates positive headlines. But all of it is required to make EV adoption actually work for most people, rather than just the affluent early adopters who can afford the premium and have suitable homes.

The government could have launched a campaign that said: "Electric vehicles are essential for our climate targets. We're investing £X billion in charging infrastructure, helping lower-income households afford EVs, retraining displaced workers, and building battery manufacturing capacity. This transition will take time and require shared effort. Here's what we're doing."

Instead, they said: "Buy an EV now." It's simpler, catchier, and less honest. And that's the real issue.

Key Takeaways

- Public charging infrastructure covers only 50,000 points across the UK with 20-30% non-functional and 32% of population unable to access home charging

- EV purchase prices remain £8,000-9,000 premium over equivalent petrol cars, beyond reach for middle-income households despite government subsidies

- Grid capacity requires £20-30 billion in upgrades beyond government's £2.5 billion charging infrastructure commitment to handle mass EV adoption

- Approximately 1.5 million renters and apartment dwellers face practical EV ownership barriers due to charging installation costs and landlord accessibility

- Battery material supply chains are geopolitically concentrated in China, DRC, Chile with recycling infrastructure virtually non-existent in the UK

Related Articles

- How BYD Beat Tesla: The EV Revolution [2025]

- How Chinese EV Batteries Conquered the World [2025]

- Offshore Wind Legal Victories: Why Trump's Setbacks Matter [2025]

- Best Gear & Tech Releases This Week [2025]

- Trump and Governors Push Tech Giants to Fund Power Plants for AI [2025]

- Electric Vehicles in the Mille Miglia: Racing's Toughest EV Challenge [2025]

![UK Electric Car Campaign: 5 Critical Roadblocks the Government Ignores [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/uk-electric-car-campaign-5-critical-roadblocks-the-governmen/image-1-1768930771020.jpg)