AI in Film Production: How 'Killing Satoshi' Changes Hollywood [2025]

Hollywood just crossed a threshold it's been tiptoeing toward for years. Not quietly. Not without controversy. A major film production is about to premiere with performances that weren't entirely captured on set, locations that don't exist in the physical world, and artistic decisions made partly by algorithms.

Killing Satoshi, an upcoming biopic about Bitcoin's mysterious creator Satoshi Nakamoto, will use generative AI to generate filming locations and adjust actor performances in ways that go far beyond the typical digital effects work we've grown accustomed to. The film, directed by Doug Liman (best known for The Bourne Identity and Edge of Tomorrow), stars Casey Affleck and Pete Davidson in undisclosed roles. But the real co-star? Machine learning.

This isn't a gimmick. It's not even really a choice in the traditional sense. It's an experiment that reveals something uncomfortable about where the film industry is heading, whether the industry is ready or not. And it's happening right now, with union actors, established directors, and major production resources.

What makes this moment so significant isn't just that AI is being used on a film set. AI has been used in film for years. Visual effects studios have been experimenting with machine learning for rendering, color correction, and even dialogue synthesis. What makes Killing Satoshi different is the scale, the transparency, and the raw ambition of what's being attempted.

The production will shoot on what's called a markerless performative capture stage. Actors will perform in a space where their movements, expressions, and emotional beats are captured digitally. Then, generative AI systems will handle the rest. Need a different background? The AI generates it. Need to adjust the emotional intensity of a line? The AI tweaks it. Need to composite an actor's performance into a location that was generated by another algorithm? Welcome to 2025 filmmaking.

But here's what nobody's really talking about: this approach raises fundamental questions about the nature of film performance itself. Is an actor's performance their intellectual property? Can it be modified without their knowledge after the scene is filmed? What happens when a studio can iterate on a performance the same way they'd iterate on CGI? And most pressingly, what does this mean for thousands of actors whose livelihoods depend on their performances being irreplaceable?

Let's break down what's actually happening, why it matters, and where this technology is taking us.

The Technology Behind AI-Generated Film Locations

How Generative AI Creates Physical Spaces

Film production budgets have always been dominated by one thing: locations. Whether you're shooting in New York, Prague, or a remote island, the cost of securing locations, traveling crews, managing logistics, and dealing with local permits can easily consume 15-25% of a film's entire budget. Sometimes more.

Generative AI changes this equation fundamentally. Instead of scouting locations for weeks, securing permits that take months, and building sets that cost hundreds of thousands of dollars, you can now describe a location to an AI system and have dozens of photorealistic variations generated in hours.

The technology works like this: A generative model (typically a diffusion model or transformer-based architecture) has been trained on millions of images of real locations, lighting conditions, architectural styles, and environmental details. When you provide it with a prompt like "abandoned warehouse in 1970s Brooklyn with natural light coming through broken windows," the model generates images that look photographically real, but don't exist anywhere on Earth.

The sophistication here is crucial to understand. These aren't cartoon backgrounds or obviously fake environments. Modern generative models trained on vast datasets can produce locations with physically plausible lighting, realistic material properties, consistent shadows, and architectural details that hold up to scrutiny. They can generate the same location in multiple weather conditions, times of day, and seasons.

For Killing Satoshi, this means the production team can stay on a single capture stage and generate hundreds of different environments. The director Doug Liman can say "I want this scene to happen in a Tokyo apartment with rain streaking the windows and neon signs reflecting off wet pavement." The AI generates that. Wants to try the same scene in a Bitcoin mining facility in Iceland? Regenerate. Like the first version better? Keep the footage with the Tokyo apartment background.

The Capture Stage Advantage

The markerless performative capture stage is where this gets really interesting technically. Traditional motion capture requires actors to wear suits covered in reflective markers. Cameras track those markers, and motion capture software converts the marker positions into digital bone structures and skeletal animation.

Markerless capture is different. Computer vision systems track the actor's movements, facial expressions, and body position without any special equipment. The actor just performs naturally in normal clothing. Software infers the 3D body position, facial deformations, and hand positions from raw video footage.

This is significantly harder technically. It requires robust pose estimation algorithms, facial action unit detection, and hand tracking systems that work from multiple camera angles. But the advantage for actors is obvious: no uncomfortable suits, no markers getting knocked off, no technical interruptions. You just perform. The technology captures everything.

Once the performance is captured in 3D space without any environmental context, the AI systems take over. The performer is now a wireframe skeleton with facial expressions and hand positions. That data can be placed into any generated environment. The camera can move through space that doesn't exist. Lighting can be adjusted. Shadows can be recalculated to match the generated background.

Performance Modification and Ethical Gray Areas

Here's where things get legally and ethically murky. The casting notice for Killing Satoshi, as reported by Variety, explicitly gives the producers the right to "change, add to, take from, translate, reformat or reprocess" actors' performances using "generative artificial intelligence and/or machine learning technologies."

This language is deliberately broad. It doesn't say they'll fix technical problems. It doesn't say they'll enhance performances. It says they reserve the right to fundamentally alter what an actor did on set.

What does that mean in practice? Nobody outside the production knows yet because this is new territory. It could mean adjusting the intensity of a performance. It could mean changing the timing of a line delivery. It could mean making an actor appear to express an emotion they didn't actually convey. It could mean taking a line that wasn't delivered quite right and having the AI system synthesize what the line would sound like with different emotional beats applied.

Actors have always had their work edited in post-production. Directors cut scenes, adjust pacing, add music, change context. But there's a difference between editing a performance and modifying it at the level of microexpressions and tone of voice. One is artistic direction. The other is something closer to performance replacement.

The production has explicitly stated that no digital replicas of performers will be created. So they're not planning to generate wholly synthetic performances of Casey Affleck or Pete Davidson. But the ability to modify existing performances after the fact, through an AI system, sits in a strange legal space that current contracts and union agreements don't really address.

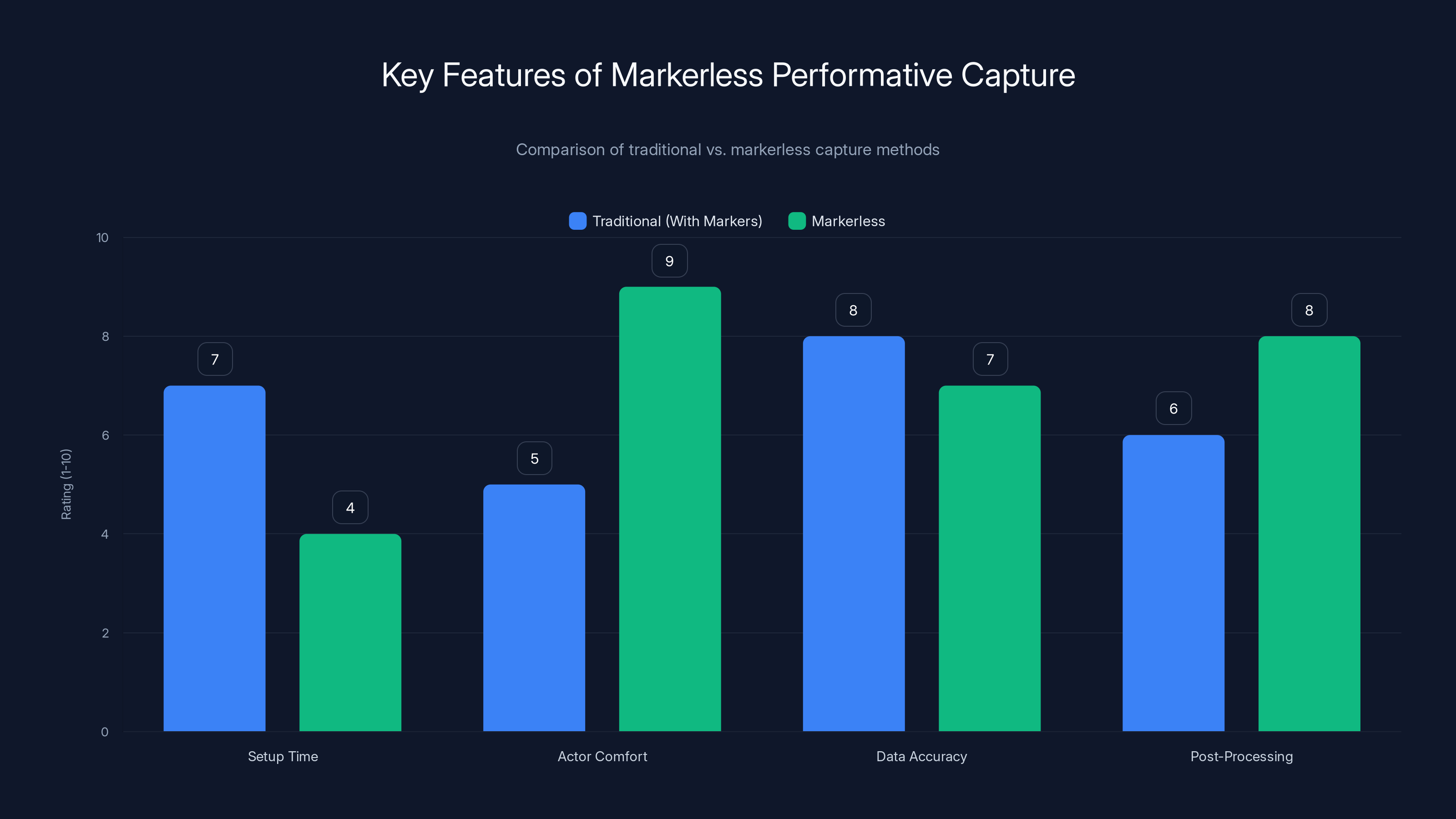

Markerless capture stages offer higher actor comfort and reduced setup time compared to traditional methods, with comparable data accuracy. Estimated data based on typical industry insights.

The Union Response and What's Really at Stake

SAG-AFTRA's 2023 Contract and AI Protections

Actors' concerns about AI aren't new. The strike that SAG-AFTRA conducted in 2023 had AI protections as one of its central demands. The resulting contract included some specific language about digital replicas and the use of an actor's likeness without consent.

But the contract was negotiated before generative AI became this powerful. The language addresses digital replicas and synthetic voices, but it doesn't really contemplate the kind of performance modification being attempted in Killing Satoshi. The casting notice specifically says no digital replicas will be created, which technically complies with the contract. But the spirit of the contract was probably to protect actors from having their performances altered without their consent.

The reality is that the union was playing defense. They were trying to protect actors from technologies they understood. They couldn't fully anticipate how those protections would be tested within 18 months of the contract being finalized.

The UK Equity Union and International Implications

Equity, the union representing actors in the United Kingdom, is currently negotiating its own AI protections with producers. The fact that Killing Satoshi appears to be using a UK casting notice suggests the production may be partially or wholly UK-based, which means Equity jurisdiction likely applies.

Equity's concerns are similar to SAG-AFTRA's but possibly more prescient. They're specifically worried about AI being used to reproduce likenesses and voices without consent, and to use those synthetic performances commercially without paying the original actor.

Both unions are essentially saying: actors should own their likenesses and performances. If a studio wants to use AI to modify, recreate, or synthesize your performance, they should pay you. You should have approval rights. You should be able to say no.

The problem is that Killing Satoshi is probably a test case for how much you can do within the letter of current agreements, even if it violates their spirit. The production is being transparent about using AI, which is genuinely more honest than hiding it. But transparency isn't the same as getting informed consent from the actors involved.

Why This Matters Beyond Acting

People tend to frame the AI + film conversation entirely around protecting actors. That's important, but it's incomplete. The larger question is about creative control and ownership. If a director's vision can be modified by AI systems after shooting wraps, who's actually directing the film? If producers can regenerate performances until they get the emotional tone they want, what's the value of casting the right actor in the first place?

These aren't hypothetical questions. If Killing Satoshi works and generates positive press, other productions will do the same thing. Studios will realize they can save money on location scouts, on shooting multiple takes, on expensive reshoots. They'll invest in AI systems that let them iterate on performances like they iterate on visual effects.

Within five years, this could become standard practice. Not because anyone thinks it's ideal, but because it's more efficient and cheaper. And once it's standard, the leverage that actors have to negotiate against it basically disappears.

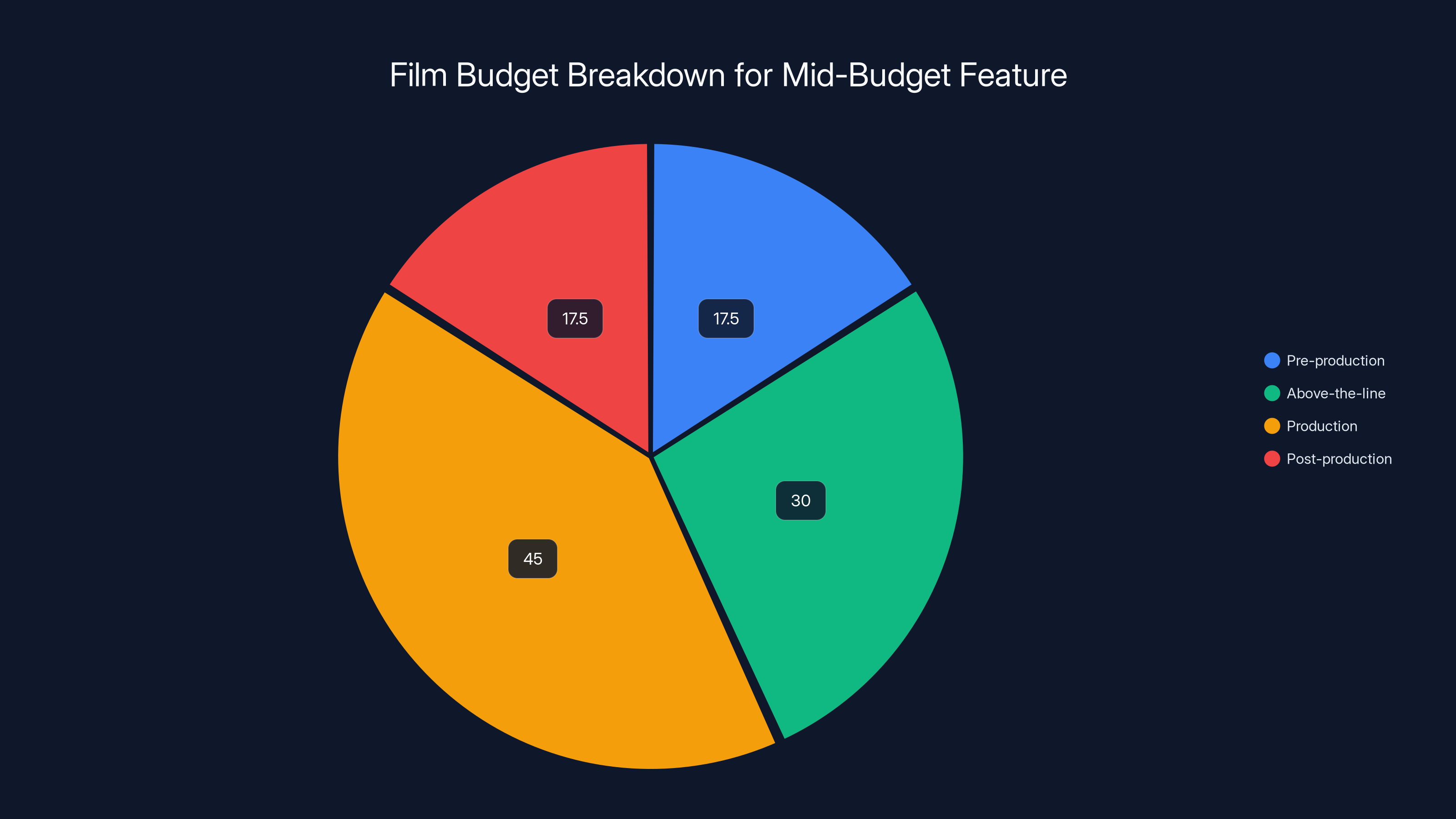

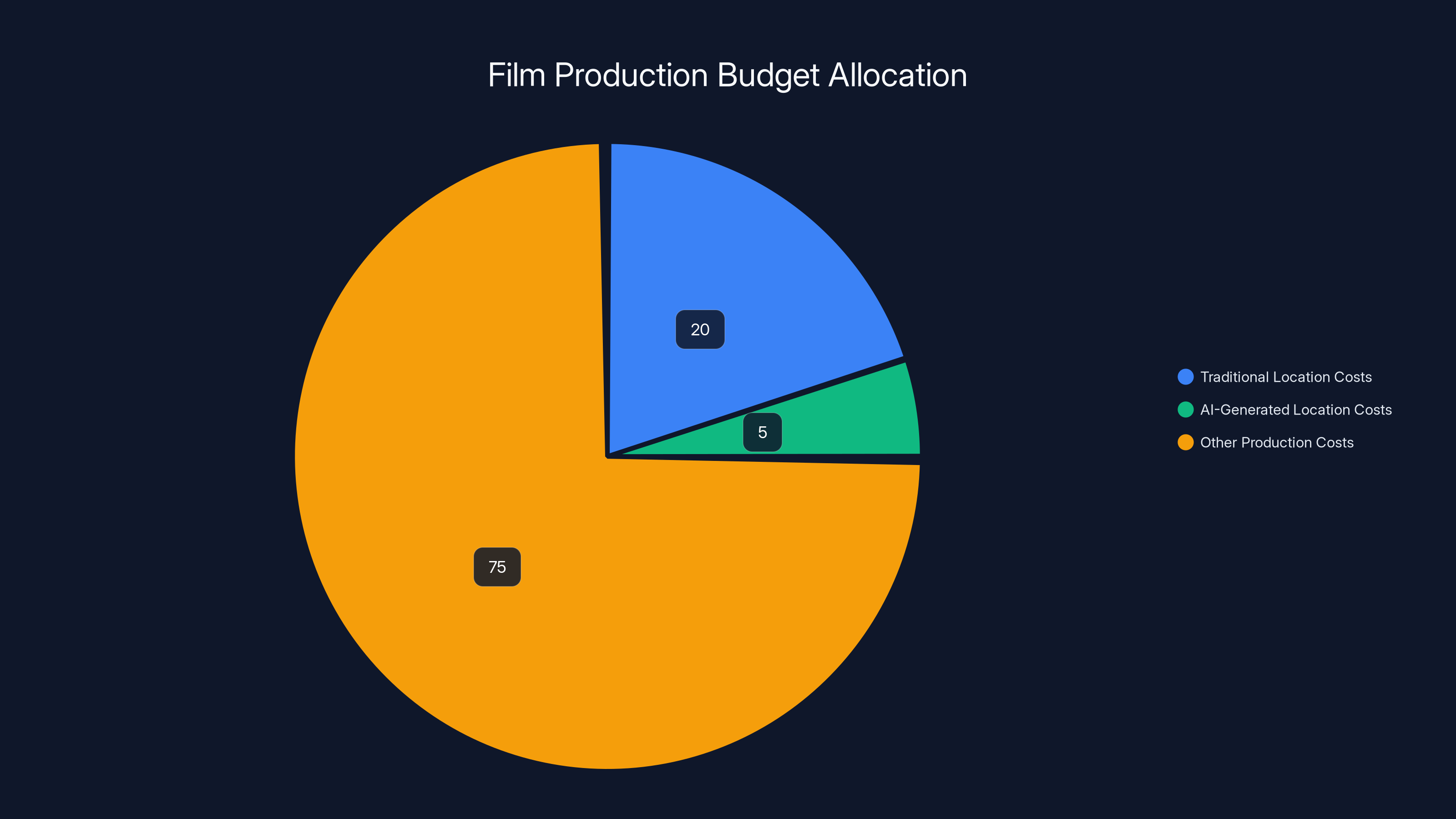

In a typical mid-budget film, production costs dominate, but AI could reduce location costs by 40-60%, saving

How AI Location Generation Actually Works in Practice

The Technical Pipeline

Understanding how this actually works technically makes the implications clearer. Here's the approximate pipeline that Killing Satoshi is probably using:

-

Markerless capture records the actors' performances with multiple camera angles. Computer vision systems extract 3D skeletal data, facial expressions, and hand positions. No environmental data is captured because the actors are performing against a blank stage.

-

Scene description is provided by the director, production designer, or cinematographer. This might be a detailed written description, reference images, concept art, or a combination. The goal is to communicate what the environment should look and feel like.

-

Generative model processing takes that description and generates photorealistic environment images. Modern models like those based on diffusion architectures can take textual descriptions and produce highly detailed, spatially consistent environments. Multiple variations can be generated, allowing the team to choose between options or blend them.

-

3D environment reconstruction converts the 2D generated images into 3D geometry that cameras can move through. This is computationally intensive but necessary because the camera position changes throughout a scene. If a camera pans across a room, the background needs to be geometrically coherent, not just a flat 2D image.

-

Performance composition takes the captured actor movement and expression data and places it into the generated environment with proper lighting, shadows, and interaction. The actor's data is essentially digital clay that can be positioned in space and rendered with any background.

-

Iteration and adjustment allows directors to modify performances, adjust lighting, change camera movements, or regenerate environments without reshooting. This is where the efficiency gains and ethical concerns intersect.

Why This Approach Makes Sense for a Bitcoin Biopic

It's fair to ask why a film about Bitcoin specifically would need this approach. Bitcoin is fundamentally about decentralization and removing intermediaries. Using cutting-edge AI to make a film about it has a certain meta quality, though it's unclear if that's intentional.

More practically, the Satoshi Nakamoto biography is challenging to film traditionally. Satoshi is pseudonymous and has never appeared publicly. The timeline spans from 2008 to the present day across multiple countries. Bitcoin's technical nature means the story involves a lot of abstract concepts that are hard to visualize cinematically.

By using generated locations and performance capture, the production gains flexibility. They can show Satoshi in environments that evoke the emotional tone of moments without needing exact historical accuracy. They can show multiple interpretations of events where Satoshi's identity is uncertain. They can create visual metaphors for abstract technical concepts.

But they could do all of this with traditional filmmaking too. It would just cost more and take longer. That the production chose this approach reveals something about where Hollywood's cost-benefit analysis has shifted. When AI-generated backgrounds become an option, the economic pressure to use them becomes immense.

The Broader Implications for Film Production

Budget and Timeline Changes

If Killing Satoshi succeeds technically and commercially, the economics of film production shift dramatically. Current film budgets break down approximately like this for a mid-budget feature:

- Pre-production and development: 15-20% (script, planning, hiring)

- Above-the-line: 25-35% (director, stars, writers, producers)

- Production (principal photography): 40-50% (crew, equipment, locations, shooting logistics)

- Post-production: 15-20% (editing, visual effects, sound, color, music)

Within the production budget, locations, set construction, and the logistical costs of moving crews between locations can easily represent 15-25% of the total budget. For a

If AI-generated environments eliminate the need for location scouts, permits, travel, and set construction, that cost could drop by 40-60%. For a

Timeline improvements are equally significant. Location scouting typically takes 2-4 months. Securing permits can take another 1-3 months depending on the locations. By eliminating this step, a production could theoretically compress its pre-production timeline substantially.

The Standardization Pathway

Historically, new technologies in film follow a predictable pattern:

-

Innovation phase: Early adopters (often filmmakers with strong creative vision or experimental approaches) use new technology in interesting ways. Everyone marvels at the artistry and technical achievement.

-

Cost adoption phase: Studios realize they can save money with the technology and begin using it routinely, sometimes effectively and sometimes as a cost-cutting measure that reduces quality.

-

Standardization phase: The technology becomes expected. Films that don't use it seem dated. It's no longer optional.

-

Fatigue and backlash phase: Audiences grow tired of the aesthetic. Creators find it limiting. Niche films that reject the technology gain prestige by their restraint.

Digital color grading went through this cycle. CGI went through this cycle. Motion capture went through this cycle. Generative AI will too.

The question is how fast that cycle happens. Digital color grading took about 10 years to go from novelty to standard. CGI took 15-20 years. With generative AI developing faster and the economic incentives being stronger, it could happen in 5-10 years.

Quality and Aesthetic Questions

There's a legitimate artistic question about what's lost when locations are generated rather than discovered. Traditional location cinematography developed an aesthetic because real locations have characteristics that generated environments don't. Weathering, patina, asymmetries, unexpected details, actual geography.

Photorealistic generative models are trained to average across massive datasets. That means they're good at generating typical versions of things. A typical apartment, a typical warehouse, a typical cityscape. What they're less good at is generating weird, specific, historically accurate, or artistically distinctive environments.

Great cinematography often works because it finds the weird details that make a location singular. The specific angle of light through a particular building's windows. The way rust patterns tell a story. The particular texture of a street in a specific neighborhood at a specific time.

AI-generated environments will probably be technically impressive but aesthetically homogenized. They'll look like what a machine learning model thinks a location should look like, which is the statistical average of thousands of training examples.

That doesn't mean AI-generated locations can't be artistically effective. It just means they'll have a different aesthetic, and that aesthetic might become tiresome if overused.

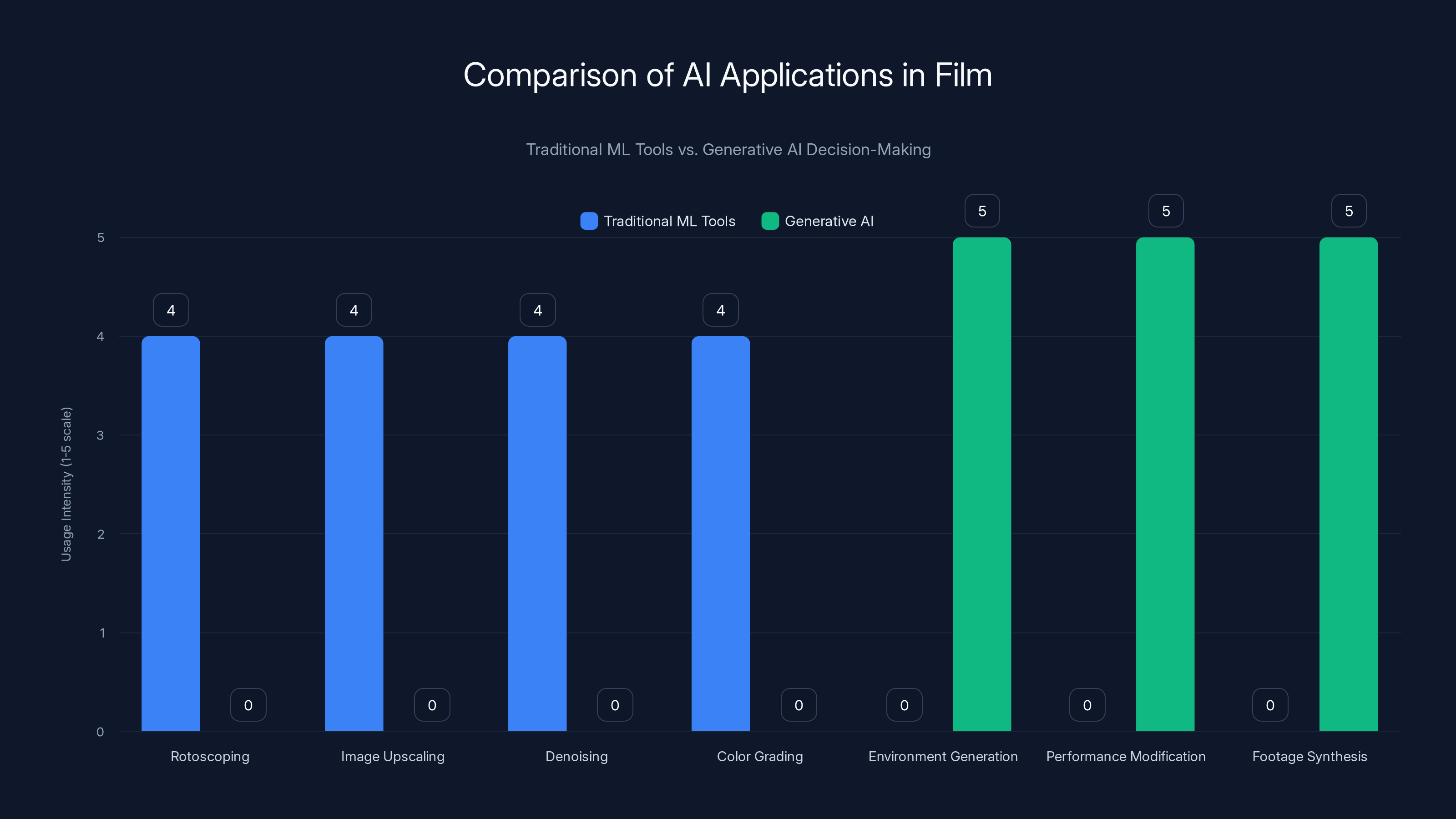

Traditional ML tools in film focus on enhancing technical tasks, while generative AI is used for creative decision-making, marking a shift in how AI influences film production. Estimated data.

Actor Performance Modification: The Technical Details

What Generative AI Can and Can't Do to Performances

The casting notice for Killing Satoshi gives producers broad rights to "change, add to, take from, translate, reformat or reprocess" performances. But what does that actually mean technically?

Here's what's currently possible:

Emotional intensity adjustment: Machine learning models trained on human expression can infer emotional intensity from facial microexpressions and modify those expressions to be more or less intense. A subtle smile can be made into a bigger smile. A concerned expression can be made more pronounced. The model learns the relationship between emotional intensity and specific facial muscle configurations.

Timing modification: The rhythm and pacing of a performance can be adjusted by stretching or compressing motion capture data. If an actor delivers a line slightly too fast or too slow, the timing can be mathematically adjusted without reshooting.

Gaze direction: Where an actor is looking can be modified in post-production. If they're looking stage left but the scene needed them to look stage right, the eye gaze can be computationally adjusted.

Expression blending: If an actor performed a scene with different emotional interpretations (happy version, sad version, angry version), machine learning can blend between those expressions. A system could generate a version that's 60% happy and 40% sad, mathematically interpolated between the two performances.

Dialogue synthesis: This is the most controversial capability. If an actor's voice is well-captured and a text-to-speech model is trained on their voice, the system can synthesize new dialogue. However, the Killing Satoshi production hasn't indicated they're doing this, and it would likely face additional union pushback.

What's currently not possible (or would be extremely obvious if attempted):

Completely new expressions: You can't synthesize an expression the actor never performed. You can only modify or blend expressions from the recorded performance.

Fundamental personality changes: You can't make someone seem like a different person. The underlying likeness and physical characteristics remain.

Physically impossible movements: The human body's kinetic constraints are generally maintained.

The Problem of Consent and Control

The ethical issue with performance modification is consent. An actor consents to perform a certain way on a certain day. They might give their all for a scene, and the director chooses a take they're proud of. Then, in post-production, that performance is modified in ways they didn't consent to.

Currently, contracts do include language about post-production modifications. Directors can color-correct footage, adjust timing through editing, add effects, and change context through music and surrounding dialogue. But there's a difference between editing and modification.

Editing is the art of selecting and arranging footage. Color correction is technical adjustment. Performance modification is changing what the actor actually did.

The distinction matters legally and artistically. An actor should be able to say: "You can edit my performance, but you can't modify my expressions or the emotional content I delivered. If you don't like the take, shoot it again."

Unions will likely demand that clause in future contracts. But for Killing Satoshi, if those actors signed consent forms, the production has legal cover.

Comparison to Previous AI in Film

How This Differs from Traditional Visual Effects

Visual effects studios have used machine learning for years. It's not new. But there's a crucial difference between using ML for technical tasks and using it for creative decisions.

Traditional ML in film:

- Rotoscoping automation (tracing actor movements automatically rather than frame-by-frame)

- Image upscaling (making lower resolution footage look higher resolution)

- Denoising (removing grain or artifacts from footage)

- Color grading assistance (ML suggests color corrections based on the overall image)

These are tool applications. The human artist (visual effects supervisor, colorist, compositor) uses ML to work faster. But the creative decisions remain human.

Generative AI in film:

- Generating entire environments from descriptions

- Modifying actor performances without explicit creative direction

- Synthesizing footage that has no captured equivalent

- Making creative decisions based on training data statistics

These are decision-making applications. An algorithm is choosing what something should look like based on patterns in training data. A human reviews the results, but they're choosing from AI-generated options rather than creating from scratch.

Historical Precedent: Digital Stunt Doubles

The closest historical parallel is digital stunt doubles, pioneered in films like The Curious Case of Benjamin Button and The Jungle Book. Studios created entirely synthetic human figures to perform dangerous stunts or impossible movements.

At first, this was controversial. Actors and stunt performers worried about job security. But the technology had clear limitations. Digital doubles looked slightly off. They were expensive to create. They only worked in specific contexts (wet environments, extreme lighting, fast action).

Eventually, the industry developed a compromise: digital stunt doubles are allowed, but stunt performers are paid for them. The actor or stunt performer whose likeness is used gets compensation. Unions developed explicit language about when and how digital doubles can be used.

Generative AI will likely follow a similar path, but faster and with less creative distinction. A digital stunt double for a specific stunt is a precise, limited use case. Generative AI that can modify any performance in any scene is much broader.

The union response will probably be:

- Compensation: If your performance is modified by AI, you get paid for it as a separate service

- Approval rights: You have to approve how your performance is modified before it's used

- Credit clarity: The final film credits clearly distinguish between performed and AI-modified content

- Data protection: The studio can't use your performance data to train models on future projects without explicit consent and payment

But all of this is yet to be negotiated. Killing Satoshi is happening in a legal gray area that unions are still trying to define.

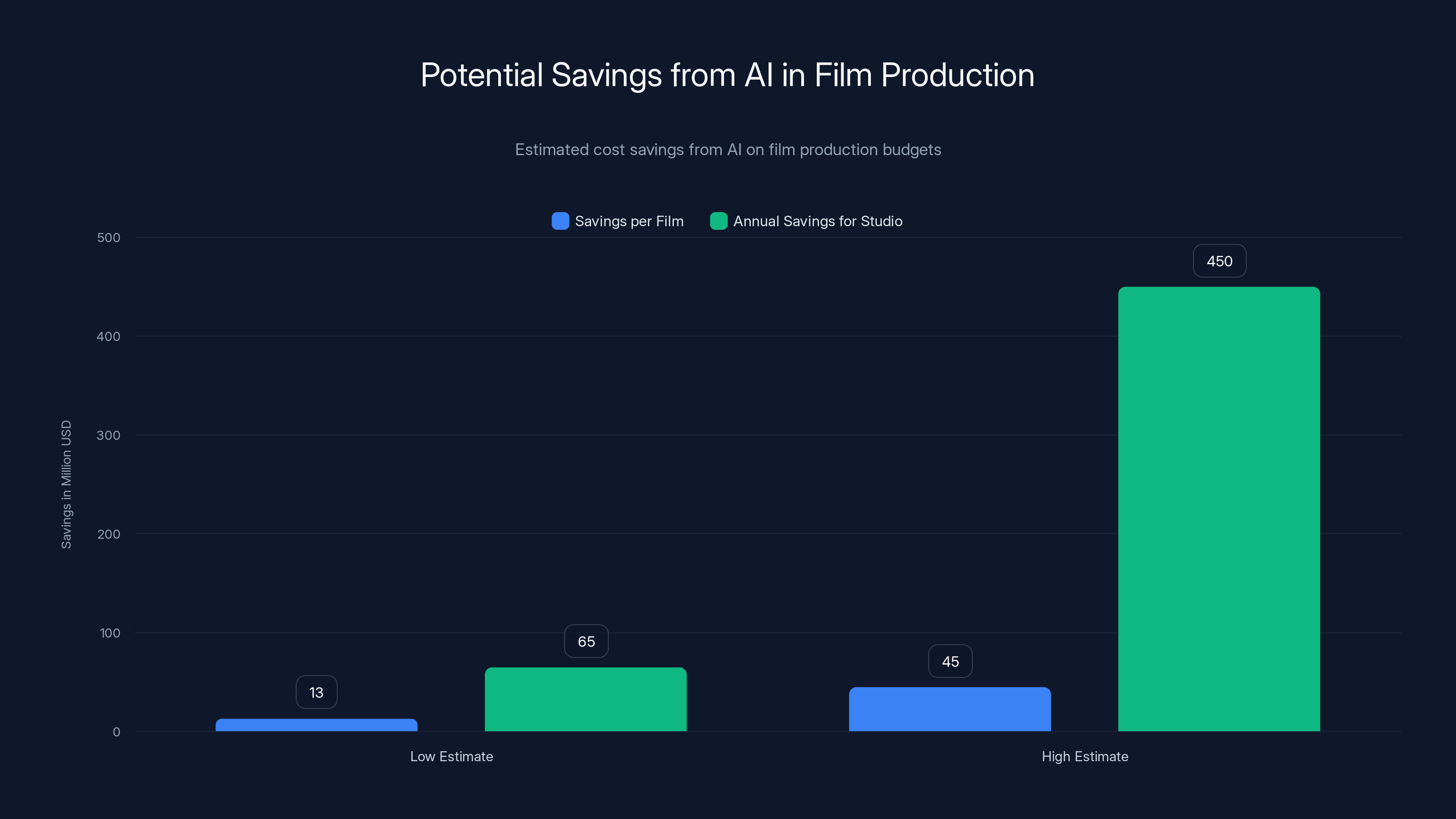

AI technology could save studios

The Director's Perspective: Doug Liman's Vision

Why a Prestige Director Would Choose This Approach

Doug Liman has directed The Bourne Identity, Mr. & Mrs. Smith, Edge of Tomorrow, and Go earlier in his career. He's a filmmaker known for dynamism, complexity, and visual storytelling. He's also known for unusual projects: he's been attached to a Tom Cruise film shot partially on the International Space Station.

Why would such a director choose to film entirely on a capture stage with generated environments? Several possible reasons:

Creative freedom: Instead of being constrained by existing locations, Liman can design environments that perfectly match his visual ideas. He's not compromising because the ideal location doesn't exist. He creates the ideal location.

Iteration capability: He can adjust performances and environments without reshooting. If he decides a scene needs a different emotional tone, he can modify the captured performance and regenerate the background to match that tone.

Technical experimentation: Liman has a history of embracing new technology. Motion capture was novel when he worked on video game adaptation projects. He's the type of filmmaker who sees new tools as creative opportunities.

Metaphorical coherence: Making a film about Bitcoin (a technology created in abstraction, that exists only as code and mathematical consensus) using cutting-edge AI to create abstract environments has thematic resonance. The form echoes the content.

Budget pragmatism: Even visionary directors have to work within budgets. If this approach allows him to make the film more efficiently, that might matter.

What's interesting is that none of these reasons require using AI to modify performances. The location generation is defensible. The performance modification is harder to justify creatively. It suggests either that producers are pushing for it as a cost-cutting measure, or that Liman sees some creative value in iterating on performances that most other directors haven't explored.

The Risk for Liman's Reputation

There's genuine professional risk here. If Killing Satoshi is perceived as emotionally hollow or aesthetically dated, the blame will partially fall on Liman. Using innovative technology is bold, but it's also a gamble.

Directors who embrace new technology early are either remembered as visionaries or as the people who made the first bad movie with that technology. James Cameron and motion capture goes one way. The first fully motion-capture film that was widely panned could have set the technology back years.

Liman is betting that the artistic potential of this approach outweighs the risk. It's an expensive bet if wrong.

Union Concerns and Worker Protection

Beyond Acting: Crew and Technical Considerations

When people discuss AI in film, they focus on actors. But the technology affects many more workers.

Location scouts might become unnecessary if environments are generated. Production designers and set decorators who spend months building sets could see their roles diminish. Cinematographers accustomed to working with real light in real spaces will need to adapt to lighting generated environments. Location managers whose job is finding, securing, and managing physical locations become redundant.

SAG-AFTRA negotiated actor protections, but there's no guild for location scouts or production designers. They're affected by AI but have less organized representation to negotiate with.

This is where the labor impact becomes broader and more systemic. AI in film doesn't just threaten acting jobs. It threatens the entire ecosystem of film production work that depends on physical location scouting, building, and management.

What Successful Negotiation Would Look Like

For Killing Satoshi and future productions, successful union negotiation would probably include:

Performance modification clause: AI can't modify performances beyond what was explicitly discussed during contract negotiation. If it's done, the actor gets additional compensation equal to the cost of a reshooting day.

Data ownership: Performance capture data belongs to the actor, not the studio. The studio can use it for this film, but can't sell it, license it, or use it to train models without the actor's explicit consent and additional payment.

Credit standards: The film clearly indicates which performances were modified by AI. This could be in the credits or in a supplementary document.

Right of refusal: Actors can require that substantially modified performances of them not be used in the final film. If the modification goes too far, they can request that an unmodified take be used instead.

Royalties: If a performance is modified by AI and commercially successful (streaming, theatrical, merchandise), the actor gets a small royalty, similar to how actors get payment when their image is used in ways beyond the original contract.

Unions haven't negotiated all of this yet, but they will. Killing Satoshi is a test case that will inform those negotiations.

Estimated data: AI-generated locations can significantly reduce location costs from 20% to 5% of a film's budget, allowing more funds for other production areas.

The Technical Limitations Nobody Talks About

Uncanny Valley and Performance Authenticity

One of the understated problems with AI-modified performances is something called the uncanny valley. When something looks almost human but not quite, it creates a sense of wrongness in viewers. They can't articulate what's wrong, but they feel something is off.

Modifying facial expressions through AI runs into this problem. The human face is extraordinarily sensitive to authenticity. We notice micro-expressions that last 40 milliseconds. We're calibrated to detect genuine emotion from subtle cues.

When an AI system modifies an expression, it's mathematically correct but might lack the physiological authenticity of a genuine expression. The result might look perfect in screenshots but feel wrong during a 90-minute performance.

This is solvable with better training data and more sophisticated models, but it's an obstacle that won't fully disappear. Some performances will be modified successfully. Others will have a subtle wrongness that audiences feel without understanding why.

Environmental Coherence and Camera Movement

Another technical challenge is maintaining environmental coherence during camera movement. A generated location needs to be spatially consistent. If a camera pans across a room, the room needs to be geometrically real in 3D space, not just a 2D image.

Current generative models are getting better at this, but it remains a challenge. They sometimes generate inconsistent geometry, surfaces that don't align, or lighting that shifts incorrectly during camera movement.

This means that Killing Satoshi probably has constraints on camera movement that traditional filmmaking doesn't have. Complex camera moves might require regenerating environments or falling back to more traditional techniques for specific shots.

And if viewers notice jerky transitions or slightly off geometry, it breaks the immersion. A generated environment can look incredible in a static shot but wrong when the camera moves through it.

Rendering Time and Production Schedule

Generating photorealistic environments and rendering them with moving actors and cameras is computationally intensive. Even with GPU acceleration, a single second of film-quality footage can take significant rendering time.

Unless Killing Satoshi is using real-time rendering (which is possible but adds technical complexity), the production timeline includes substantial rendering time. This is a hidden cost that doesn't show up in obvious ways but can extend the post-production timeline significantly.

If the production needs to iterate on environments and performances, and each iteration requires new renders, the post-production schedule balloons. This can offset some of the savings from not scouting locations.

Market Implications and Studio Economics

Why Studios Are Pushing This Technology

From a pure business perspective, studios see AI-generated environments and performance modification as cost-reduction tools. If Killing Satoshi works and gets positive reception, studios will greenlight more productions using this approach.

The economic incentive is immense. Film budgets have inflated dramatically over the past 20 years. The average cost of producing a major Hollywood film is now

If generative AI can reduce production costs by 20-30%, that's

Those are numbers that can't be ignored from a business perspective. Executives will prioritize this technology regardless of creative concerns because the financial impact is so significant.

The Indie and International Implications

Interestingly, lower-budget films might actually benefit more from this technology than high-budget Hollywood productions. An indie film with a $2 million budget has much less flexibility with locations. Generative AI could make sophisticated-looking indie films possible without needing to spend 30-40% of budget on location logistics.

Internationally, production in countries with less developed infrastructure could become easier. You don't need to scout locations in Lagos or Mumbai if you can generate them. This could democratize filmmaking in developing markets, or it could further concentrate production in countries with the computing resources and technical expertise to use these tools effectively.

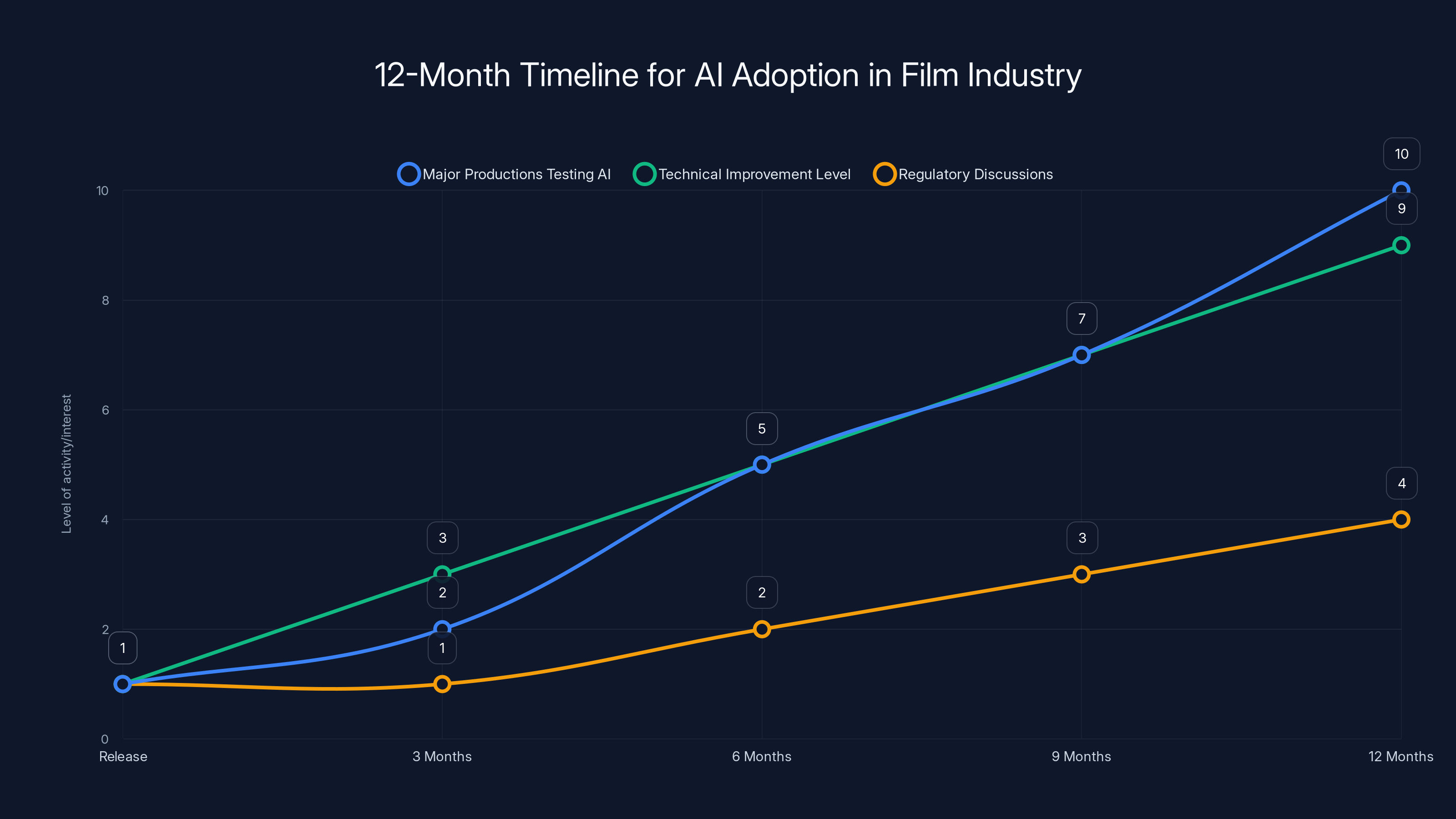

Following the release of 'Killing Satoshi', AI adoption in film is expected to grow, with 5-10 major productions testing AI within a year, technical improvements advancing significantly, and regulatory discussions increasing. Estimated data.

Historical Precedent: Other Industries and AI Integration

Lessons from Photography and CGI

When digital photography replaced film photography, professional photographers worried about obsolescence. The technology required fewer technical skills. Anyone with a digital camera could get decent results. Wedding photographers, portrait photographers, and commercial photographers all faced disruption.

What actually happened: Photography became more competitive. The barrier to entry dropped, which meant more people entered the profession. But clients still valued great photographers, who commanded higher prices because they could do things less experienced photographers couldn't. The market stratified more dramatically, with elite photographers getting more money and everyone else earning less.

A similar pattern is likely for filmmaking. AI tools will make it easier for amateurs and low-budget productions to create film-like content. But visionary directors will still command premium prices because they can do things AI systems can't do. The middle will be squeezed.

Music Production and AI

Music production offers another precedent. When digital audio workstations (DAWs) became accessible, professional music producers worried about job security. Suddenly anyone with a laptop could make music that sounded professional.

What happened: The music industry fragmented. There's more music being made than ever, but less money for individual musicians because the market is flooded. Professional producers and engineers still exist, but they're fewer in number and typically more specialized.

Film will probably follow a similar trajectory. More films will be made. More people will have access to filmmaking tools. But the economic returns for filmmakers will likely decrease because of market oversupply.

What's Next: The 12-Month Timeline

Expected Developments from Killing Satoshi

Immediate reaction: When Killing Satoshi premieres (likely late 2025 or 2026), the immediate reaction will focus on whether the AI elements are noticeable. If the film looks entirely normal and the audience doesn't know it was made with generated environments and modified performances, the reaction will be "this is amazing, other films should do this."

If viewers notice AI artifacts or if the performances feel off, the reaction will be more cautious. "Interesting experiment, but not ready for prime time."

Union response: SAG-AFTRA and Equity will use Killing Satoshi as a reference point in contract renegotiations. Demands will likely become more specific about performance modification, data ownership, and consent.

Industry adoption: Within 6-12 months, other productions will begin testing similar approaches. Not every film, but probably 5-10 major productions will pilot these technologies to varying degrees.

Technical iteration: Generative models will improve. By mid-2026, performance modification will be more subtle and effective. Location generation will be more photorealistic and geometrically consistent.

Regulatory questions: Governments may begin considering regulations around AI in film. The EU might add AI consent requirements to their media regulations. The US might consider tax implications of AI-generated sets and performances.

New roles emerge: Instead of location scouts and set designers, films will need AI environment designers and performance modification specialists. New jobs replace old ones, but not 1-to-1.

The 5-Year Projection

By 2030:

- 30-50% of major films will use AI-generated environments to some degree

- Performance modification will be standard in post-production

- Generative environments will look indistinguishable from real locations

- New union agreements will specifically regulate AI use

- Indie filmmaking will boom because tools become cheaper and more accessible

- Some prestige films will reject AI entirely as a creative statement

- The term "entirely practically shot" will become a marketing point

The Creative Perspective: What's Lost and Gained

What Practical Location Shooting Offers That AI Can't Match

When you film in a real location, unexpected things happen. Light shifts. Atmosphere emerges. The environment tells stories that the script didn't explicitly plan. Great cinematographers talk about "discovering" locations as much as using them.

AI-generated environments are designed. They're optimized for a specific creative intent. They're aesthetically coherent and thematically aligned. But they lack the surprise element that real locations provide.

There's also a fundamental difference in the relationship between actor and environment. When an actor performs in a real location, they're responding to actual spatial relationships, real light, genuine acoustic properties. They're physically present in the world they're acting in.

Performing on a capture stage against a blank wall is different. The actor performs for the camera knowing the environment will be added later. The spatial sense is abstract. The light on their face won't necessarily match the final environment's light.

Great performances sometimes emerge from the actor's genuine response to a real environment. That's hard to replicate when the environment is added in post-production.

What AI Enables That Practical Shooting Can't

On the flip side, AI enables impossible things. You can show the exact same scene in completely different visual styles. You can have camera movement that would be impossible to capture practically. You can iterate on performances without reshooting.

For certain stories, these capabilities are genuinely valuable. A story that explores multiple timelines or realities could show those visually through environment variation. A film about memory or perception could use environment modification to show how perception changes. A surreal or fantastical story has obvious benefits from generated environments.

The question is whether AI-generated environments become genuinely artistically distinct, or whether they become a generic visual language that all films using the technology share.

Regulatory Landscape and Future Legislation

Current Legal Gaps

Film and television are regulated at multiple levels: union contracts, intellectual property law, labor law, and increasingly, AI-specific regulations.

Union contracts (SAG-AFTRA, Equity, DGA) have been updated to address some AI concerns, but they're playing catch-up. Legislation is slower. Most jurisdictions don't have specific laws about performance modification by AI.

Intellectual property law addresses whether a performance is the actor's property (it generally is), but it's unclear whether an AI-modified version of that performance still belongs to the actor or is a derivative work owned by the studio.

Copyright questions:

- If an AI modifies an actor's performance, is the result a derivative work or a new work?

- Does the actor retain copyright over the modified performance?

- Can the studio use the modified performance in sequels, spinoffs, or remakes without the actor's consent?

Right of publicity questions:

- Does an actor's right of publicity extend to AI-modified versions of themselves?

- Can a studio use an AI-modified performance of an actor after that actor is deceased?

- Can a studio synthesize new performances of an actor without consent?

These questions don't have clear legal answers yet. Courts will eventually have to decide them, probably through multiple lawsuits over the next 5-10 years.

Emerging Regulations

The EU is ahead on AI regulation. The AI Act includes provisions about transparency when AI is used in high-risk applications. Film production might eventually be classified as high-risk, which would require disclosure of AI use, impact assessments, and compliance with specific standards.

The US has no comprehensive federal AI regulation, but individual states might develop their own. California has passed laws about synthetic media and deepfakes, which could apply to AI-modified performances.

International film bodies like AMPAS (the organization that gives the Oscars) will eventually need to define rules about AI use in films eligible for awards. They might require disclosure, or they might create separate categories for AI-heavy productions.

The Bottom Line: Where This Is Heading

Generative AI is becoming a standard tool in film production. Killing Satoshi is not an anomaly. It's a signal of where the industry is headed.

Within five years:

- AI-generated environments will be routine for most productions

- Performance modification will be standard in post-production

- Entire new roles will emerge around AI use in production

- Old roles (location scouts, set construction) will diminish

- Union negotiations will center on AI rights and compensation

- Some films will reject AI as a creative statement

- Audiences will develop opinions about the aesthetic of AI-assisted film

The big question isn't whether this technology will be used. It will be. The question is whether the industry develops ethical guidelines and fair compensation structures before AI use becomes completely normalized. Once it's standard, changing those practices becomes much harder.

That's where we are right now. Killing Satoshi is being made in a window where decisions are still being made about how this technology gets integrated. Once the precedent is set and the economics prove the model works, inertia takes over.

For actors, crew members, and filmmakers concerned about these changes, the time to demand protections is now, not after 100 productions have already used these techniques without restriction. The negotiation window is open, but it's closing fast.

FAQ

What exactly is a markerless performative capture stage?

A markerless performative capture stage is a film set equipped with multiple cameras that use computer vision to track actors' movements, facial expressions, and body positions without requiring them to wear special suits with reflective markers. The actors perform normally in regular clothing, and software reconstructs their 3D body position, facial deformations, and hand positions from the video footage. This captured performance data becomes a digital version of the actor that can be placed into any generated environment and rendered with any lighting conditions.

How does generative AI create filming locations?

Generative AI creates filming locations by using trained models (typically diffusion models or transformer architectures) that have been trained on millions of real location images. When given a textual description of a desired location, these models generate photorealistic images of environments that don't exist in the physical world. The generated 2D images can then be converted into 3D environments that cameras can move through. This allows filmmakers to create any location without scouting, securing permits, or traveling to real places.

Can actors stop the production from modifying their performances?

Currently, it depends on their contract. If an actor signs a contract that explicitly gives producers the right to modify their performance using AI, they've legally consented. However, unions like SAG-AFTRA and Equity are working to limit these rights through new contract language. Future contracts will likely require additional compensation for performance modification and give actors approval rights over how their performances are changed. For Killing Satoshi, the actors apparently signed forms allowing performance modification, though the extent of that right remains unclear.

Will AI-generated locations look obviously fake?

Modern generative AI can create photorealistic locations that are nearly indistinguishable from real places in static shots. However, they sometimes have issues with geometric consistency when cameras move through them, and they may lack the subtle details and unexpected qualities that real locations have. The locations will probably look impressive on screen, but they may develop a characteristic aesthetic that becomes recognizable once many films use them. Over time, as models improve, the realism will increase.

What happens to cinematographers and location scouts if AI replaces their roles?

Traditional location scouting and set construction jobs will likely decrease as AI-generated environments become standard. However, new roles will emerge: AI environment designers who craft prompts and guide generative models, technical specialists who handle 3D environment rendering, and cinematographers who specialize in lighting and compositing AI-generated elements. The transition will be painful for workers trained in traditional approaches, which is why unions are advocating for transition assistance and retraining provisions in contracts.

Could AI-generated performances replace actors entirely?

Killing Satoshi explicitly states it won't create digital replicas of performers, and current SAG-AFTRA contracts prohibit fully synthetic performances. However, if technology develops to the point where AI can generate entirely convincing synthetic performances, and if regulations don't prevent it, studios would theoretically have strong economic incentive to do so. This is the long-term concern driving union negotiations. Contracts are being written now to prevent that possibility.

How much money could studios save using this technology?

Location-related costs (scouting, permits, travel, set construction, management) typically represent 15-25% of a film's production budget. For a

Will future Oscar-nominated films use this technology?

Likely yes, eventually. AMPAS (the organization that oversees the Oscars) hasn't yet defined rules about AI use in films eligible for awards. Once the technology matures and becomes standard, major productions will use it. AMPAS may eventually create separate categories or require disclosure of AI use, similar to how they handle other technical innovations. Killing Satoshi itself may or may not be nominated, but within 5 years, AI-assisted films competing for major awards will be common.

What are the legal risks for productions using this technology?

Legal risks include lawsuits from actors claiming unauthorized use of their performances or likenesses, challenges to ownership of modified performances, potential violations of future AI-specific regulations, and contract disputes with unions. Additionally, if a performance is modified in ways the actor objects to, they might pursue defamation claims if the modification substantially misrepresents their artistic intent. The legal landscape is developing in real-time, so productions like Killing Satoshi are essentially legal experiments.

How will audiences react to knowing a film used AI to modify performances?

That's genuinely unknown. Some audiences won't care if the final film looks and feels authentic. Others will feel manipulated or see it as cheating. There's likely to be a period of backlash and then acceptance, similar to how audiences reacted to digital cinematography, CGI, and other innovations. Filmmakers may eventually market "entirely practically performed" films as a premium offering, the way some directors market "entirely practically filmed" or "no digital effects" films today.

What's the difference between AI-modified performances and traditional film editing?

Traditional film editing selects and arranges footage. A director chooses which take to use, where to cut, how to pace scenes. An editor might trim a pause or adjust timing through cutting. Performance modification using AI goes further: it changes the actual expression, emotional intensity, or delivery of a line that was already recorded. It's not selecting an existing performance; it's altering the performance itself. This distinction matters legally and artistically because it crosses from editorial control into creative manipulation of the actor's actual work.

The future of filmmaking is being written right now, and much of that writing is happening on the set of Killing Satoshi. The question isn't whether AI will be used in film. It will be. The question is whether the industry, regulators, and unions can establish ethical frameworks and fair compensation before AI use becomes so normalized that changing course becomes nearly impossible. That negotiation window is open today. In five years, it might be closed.

Key Takeaways

- Killing Satoshi is a major film production using generative AI to create filming locations and modify actor performances, signaling an industry shift toward AI-assisted filmmaking

- Markerless performative capture technology allows actors to perform naturally while computer vision extracts 3D movement and facial expression data for later AI processing

- AI-generated environments could reduce production location costs by 40-60%, representing massive economic incentive for studios to adopt the technology

- Current union contracts address some AI concerns but leave gaps around performance modification rights, data ownership, and consent for synthetic performances

- Within 5 years, 30-50% of major films are projected to use AI-generated environments; the next decade will determine whether ethical protections and fair compensation keep pace with technology adoption

Related Articles

- Cohere's $240M ARR Milestone: The IPO Race Heating Up [2025]

- The Mortuary Assistant Movie: Game Developer Support & Cameo Reveals [2025]

- AI Recreation of Lost Cinema: The Magnificent Ambersons Debate [2025]

- Waymo's Genie 3 World Model Transforms Autonomous Driving [2025]

- Chris Hemsworth Crime 101 Stunts: Director Reveals Truth [2025]

- ElevenLabs 11B Valuation [2025]

![AI in Film Production: How 'Killing Satoshi' Changes Hollywood [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/ai-in-film-production-how-killing-satoshi-changes-hollywood-/image-1-1771018622062.jpg)