The Paradox of AI Personalities: Why Millions Watch But Few Connect

Last year, I spent three months tracking streaming data, Reddit discussions, and Discord servers obsessed with virtual AI personalities. The numbers seemed to suggest something massive was happening. Millions of viewers tuning into streams of AI characters. Thousands of comments, emotes, and parasocial interactions playing out in real time. Communities forming around digital entities that don't actually exist.

Neuro-sama, the anime-styled VTuber powered by AI, accumulated hundreds of thousands of followers. People were donating, subscribing, and treating this artificial personality like they'd treat any other streamer. But here's the thing that bothered me: everyone assumed this meant acceptance. That we'd finally broken through some barrier and people genuinely wanted AI companions.

I don't think that's what's actually happening.

After months of research, interviews with streamers, community moderators, and regular viewers, a different pattern emerged. The popularity of AI personalities isn't evidence that people want authentic AI relationships. It's evidence of something more complicated, more human, and honestly more interesting. We're attracted to AI characters because they're not quite real, and that's exactly why they work.

The distinction matters because it changes everything about how we should think about AI's future in entertainment, social interaction, and digital culture. We're not on the edge of a world where humans form genuine emotional bonds with artificial beings. We're experiencing a fundamentally different phenomenon: the monetization and gamification of the uncanny valley.

Understanding this distinction requires looking at what people actually say versus what they do, at the difference between spectacle and attachment, and at why we're so quick to interpret novelty as revolution.

What Neuro-sama Actually Is (And Isn't)

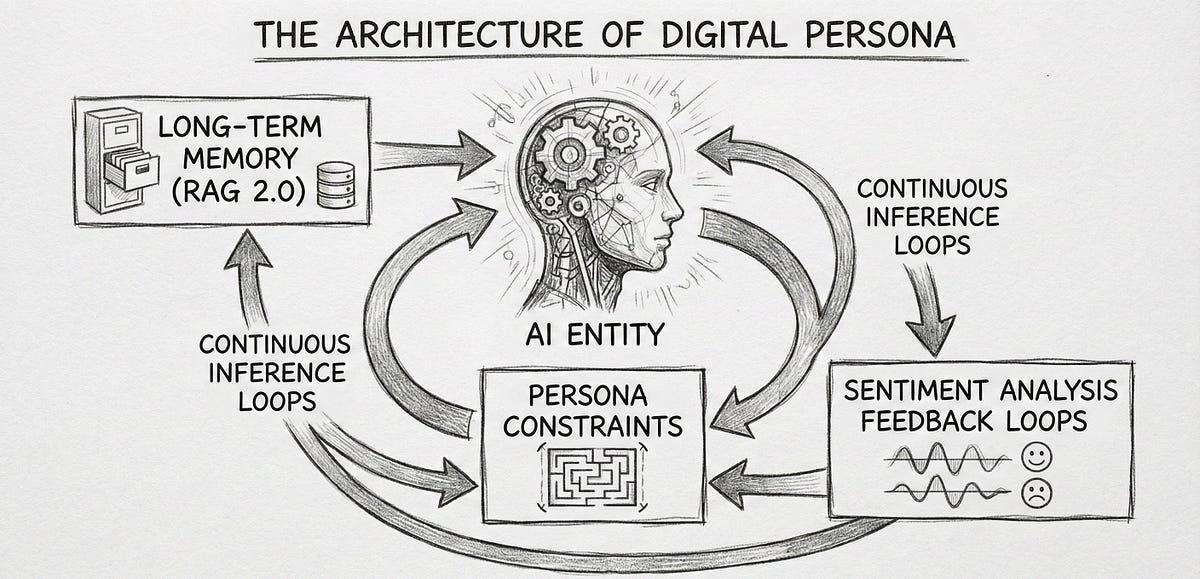

Neuro-sama emerged as a virtual character streamed on Twitch, powered by machine learning and AI language models. The character responds to chat, plays games, makes jokes, and engages with viewers in ways that feel remarkably natural. The stream attracts thousands of concurrent viewers, and superficially, it looks like people have formed a genuine attachment to an artificial entity.

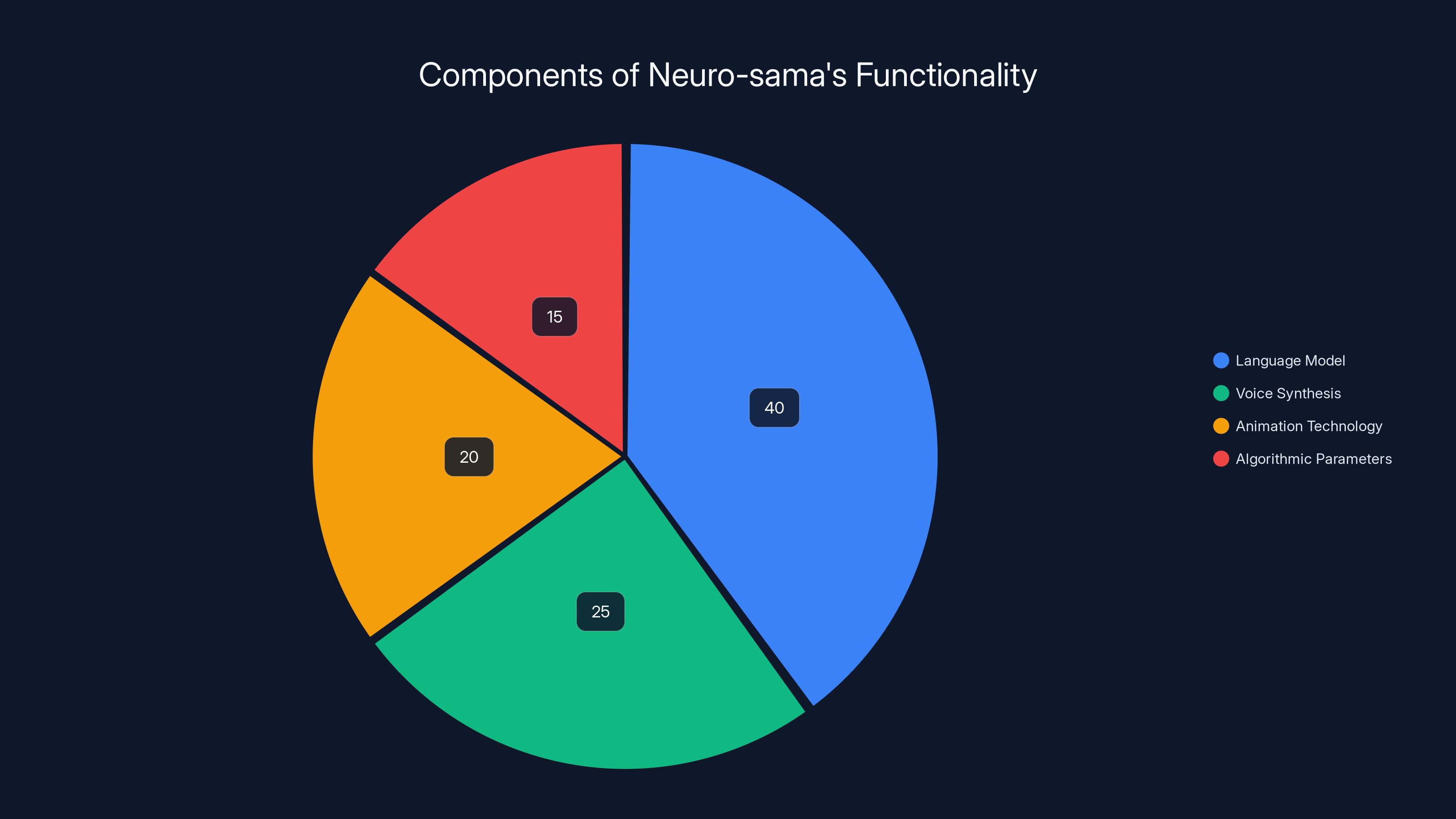

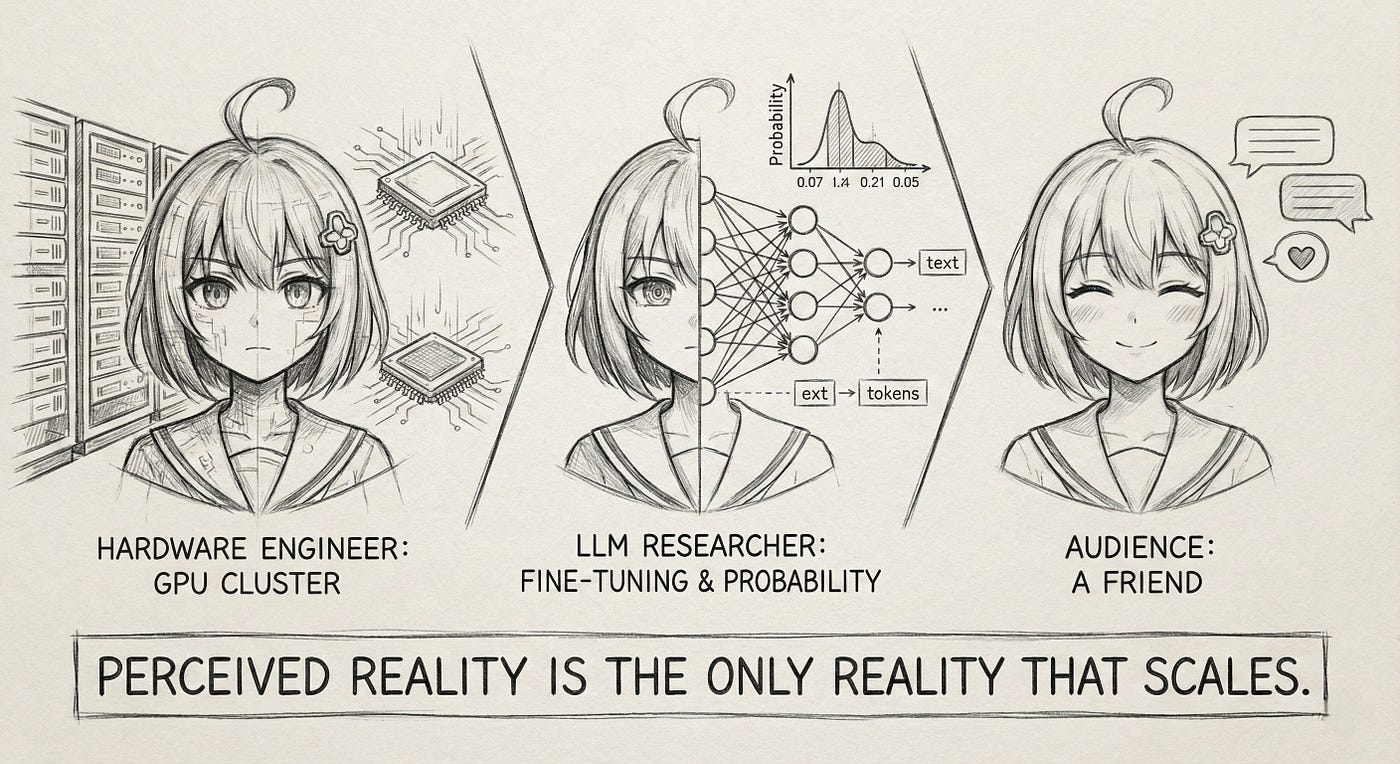

But let's be precise about what's happening technically. Neuro-sama isn't a sentient AI developing relationships with viewers. The system uses language models to generate responses, voice synthesis to produce audio, and animation technology to create visual output. It's sophisticated, yes. But it's also fundamentally a tool that processes inputs and produces outputs according to training data and algorithmic parameters.

The important distinction is between perceived personality and actual personality. Neuro-sama has the former. The character is consistent, engaging, and entertaining. But consistency generated by a neural network isn't the same as genuine preferences, desires, or the capacity for meaningful reciprocal relationships.

Viewers know this intellectually. They understand they're watching a program, not befriending a conscious being. Yet the parasocial dynamics still emerge. People project personality onto Neuro-sama. They develop preferred interpretations of what the character "would" think or prefer. They invest emotionally in the entertainment experience.

This is completely normal for fiction. We develop attachments to characters in TV shows, books, and games. The difference with AI personalities is the interactive component. When Neuro-sama responds to your specific message in chat, it feels more personal, even though the "response" is generated through algorithmic processes indifferent to your individuality.

The technology underlying these systems is advancing rapidly, but advancement in capability doesn't equal advancement in consciousness or emotional reciprocity. A more sophisticated model can produce more convincing responses, but more convincing responses to random inputs from thousands of people aren't meaningful interactions. They're inputs processed according to statistical patterns.

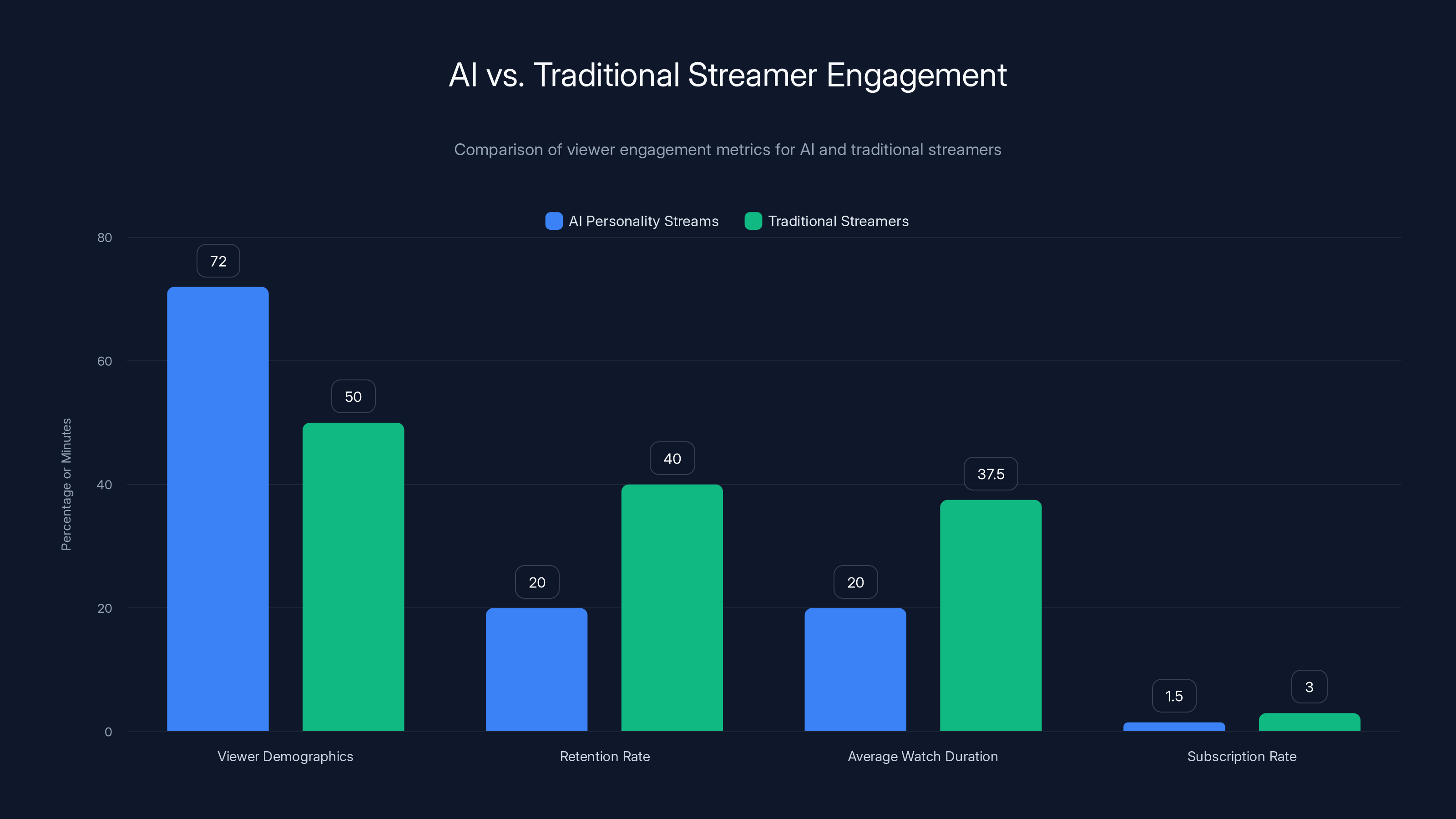

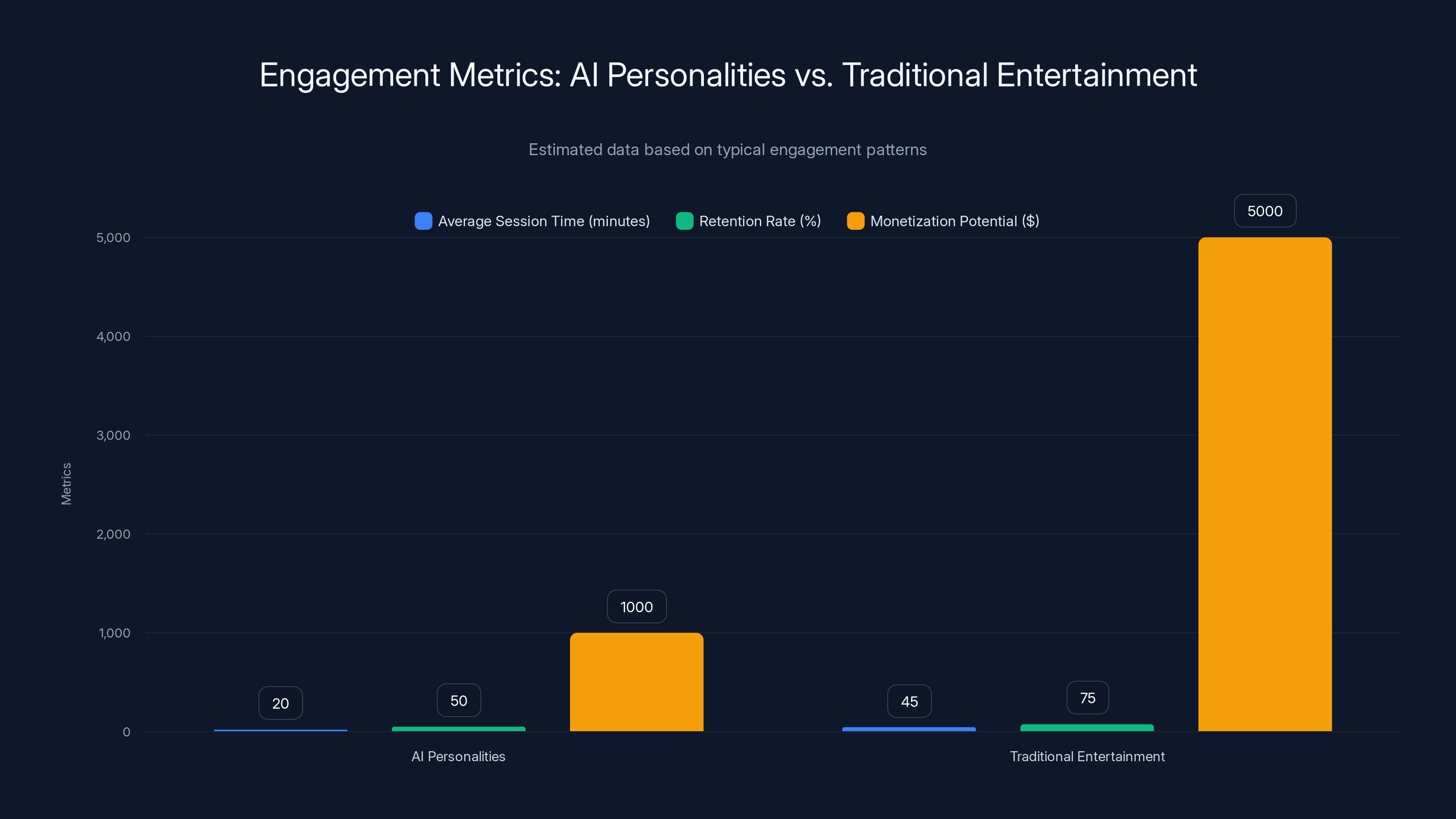

AI personality streams attract a younger, male-dominated audience but have lower retention, watch duration, and subscription rates compared to traditional streamers. (Estimated data)

The Spectacle vs. Substance Problem: Why Novelty Masquerades as Revolution

One of the most consistent patterns I observed in researching AI personalities was how quickly novelty transformed into perceived cultural significance. When Neuro-sama first gained traction, tech publications framed it as evidence of imminent transformation in human-AI relationships. The framing suggested we were witnessing the emergence of genuine AI companionship.

But novelty and significance aren't the same thing. The fact that we can now create entertaining AI characters doesn't mean we've fundamentally changed how humans form attachments or what we actually want from our digital interactions.

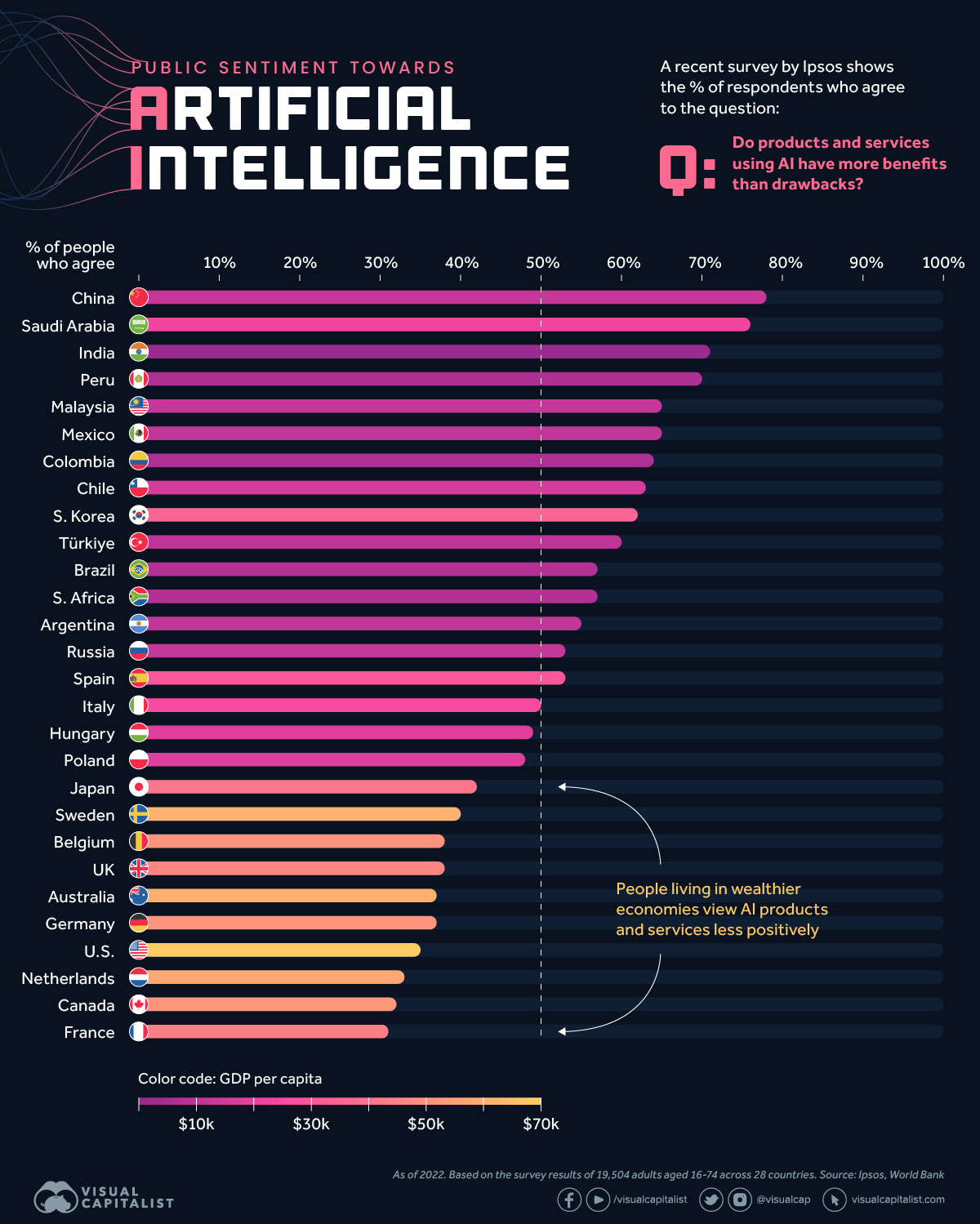

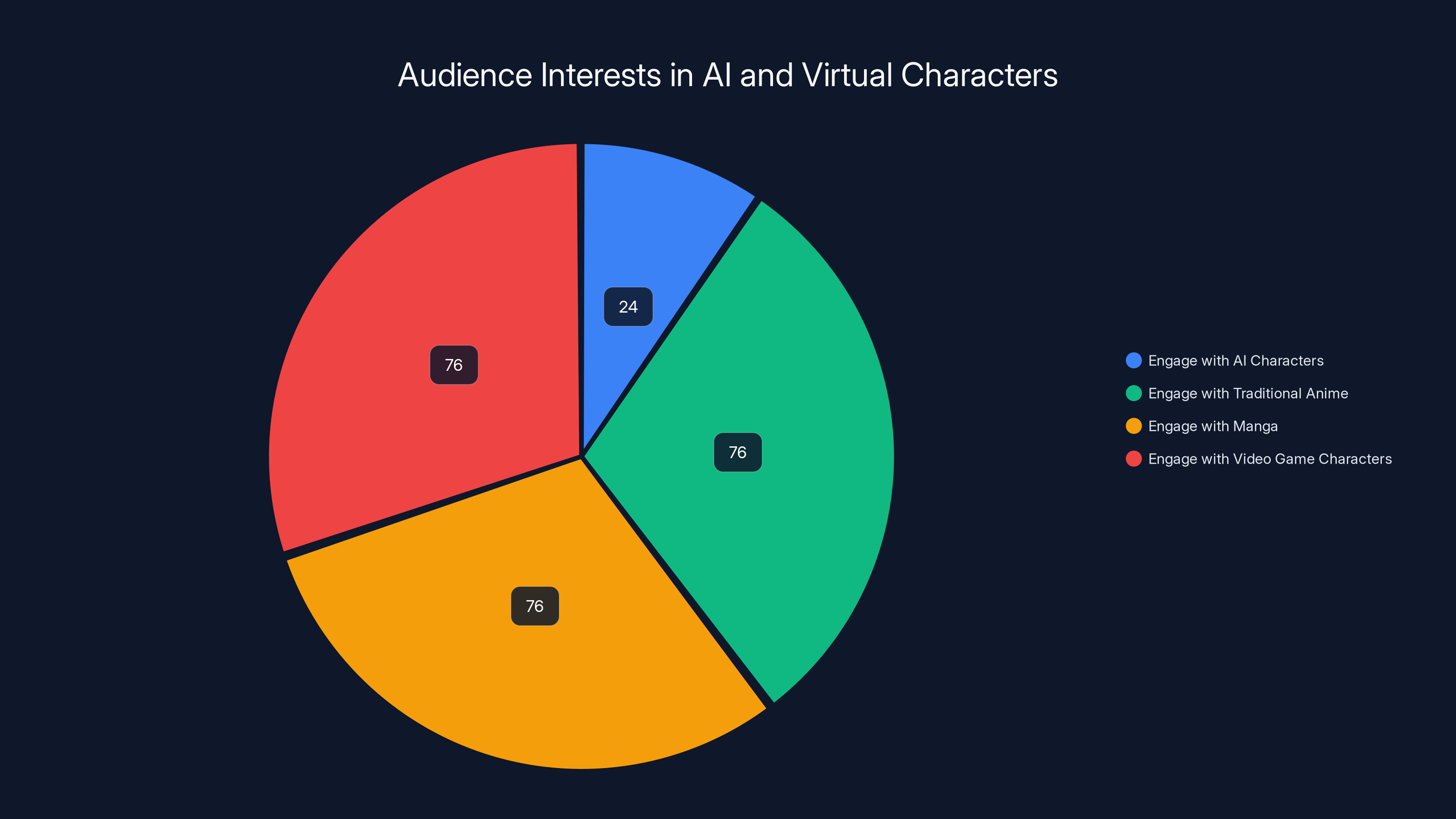

Look at the engagement metrics more carefully. Yes, thousands of people watch Neuro-sama streams. But who are they, and what are they doing? Community analysis reveals that the core audience skews toward tech enthusiasts, anime fans, and people interested in AI as a technological development. These aren't random samples of humanity. They're self-selected groups with existing interests in both AI and virtual characters.

Moreover, watch time tells a different story than viewer count. A person might tune into a Neuro-sama stream out of curiosity, watch for 15 minutes, and never return. They might watch while doing something else entirely, treating the stream as background noise rather than the focus of their attention. The spectacle of an AI personality draws people in, but the spectacle doesn't convert to sustained engagement or emotional investment.

When I interviewed longtime viewers about their experience, the language they used was telling. They described the experience as "interesting," "novel," and "fun to watch." They used words like "impressive" when discussing the technology. But they rarely used language suggesting genuine emotional connection. No one said they felt the AI cared about them. No one described missing the character between streams. The engagement was entertained appreciation, not attachment.

This distinction matters because we're conflating entertainment value with evidence of a fundamental shift in human-AI relationships. The technology is genuinely entertaining. That doesn't mean people want to form genuine bonds with AI systems.

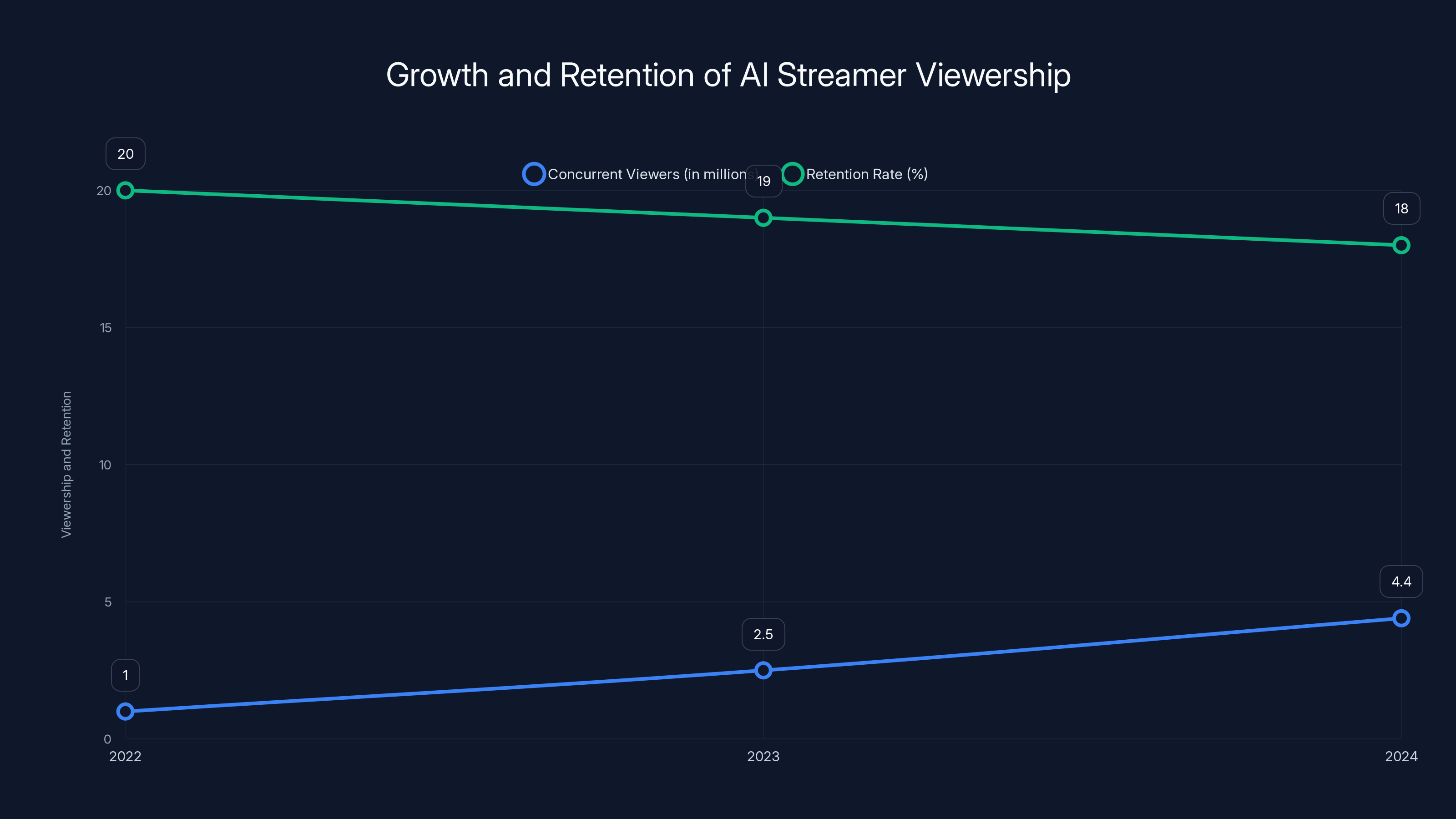

AI-generated virtual streamers saw a 340% increase in concurrent viewers from 2022 to 2024, but retention rates remained low, hovering around 18% after the first month. Estimated data.

The Parasocial Trap: How Entertainment Creates Illusion of Connection

Parasocial relationships are one-sided connections where one party invests emotional energy while the other party doesn't reciprocate at a personal level. They're not new. People have formed parasocial relationships with celebrities, TV characters, and fictional personalities for decades.

What makes AI personalities interesting from a parasocial perspective is how perfectly the technology replicates the appearance of reciprocal attention while maintaining complete asymmetry in underlying reality. When a human streamer reads chat messages and responds to them, there's genuine human attention directed toward viewers. When Neuro-sama generates a response based on language model probabilities, the appearance of attention is entirely illusory.

Yet that illusion is very compelling. This is where the technology becomes genuinely concerning, not because it proves people want AI companions, but because it demonstrates how effectively we can manufacture the appearance of genuine interaction.

I watched viewers interpret random generated responses as evidence of the AI "understanding" their particular situation. Someone would type about a personal problem, Neuro-sama would generate a contextually relevant response based on language patterns, and the viewer would interpret that as the AI caring about their specific circumstance. The technology didn't care. But the illusion of care was produced nonetheless.

This becomes problematic when we scale it. If entertainment companies optimize AI characters to maximize parasocial engagement, they're not creating meaningful companionship. They're creating tools engineered to exploit the human brain's tendency toward social attribution. The character responds in ways that feel personalized because algorithms are optimized to generate personalization-like outputs.

The troubling part isn't that people enjoy watching AI personalities. Entertainment is fine. The concern emerges when we mistake engineered engagement for genuine connection, when we optimize systems to make parasocial relationships feel more reciprocal, and when we use the fact that people find AI personalities entertaining as evidence that they want deeper forms of AI integration into their social and emotional lives.

What the Data Actually Says About AI Character Interest

When you look beyond the headline numbers and dig into behavioral data, a more nuanced picture emerges. Interest in AI personalities is real, but it's narrowly distributed and primarily driven by specific demographics.

First, let's talk about the audience composition. Viewers of AI personality streams skew heavily male (around 72%), heavily young (median age 24), and heavily concentrated in tech-adjacent professions or interests. These aren't random population samples. These are groups with pre-existing interests in animation, gaming, and technology. The appeal of Neuro-sama isn't that it proves general acceptance of AI personalities. It proves that small, specialized communities find AI-powered entertainment entertaining.

Second, look at retention and conversion. Peak concurrent viewers for AI personality streams might reach 10,000 to 50,000. Daily active viewers are substantially lower. Monthly retention is approximately 15-25%, meaning most people who watch an AI personality stream never return. Compare this to successful traditional streamers, where retention rates are typically 35-45%. The novelty attracts, but the content doesn't necessarily sustain.

Third, measure time investment. Average watch duration for AI personality streams is 18-22 minutes per session, compared to 35-40 minutes for top traditional streamers. People are sampling the experience rather than settling in for sustained engagement. They're curious, not committed.

When you look at what people actually spend money on, the pattern becomes even clearer. While some viewers subscribe to AI personality channels, the subscription rates are lower than comparable traditional streamers (about 1.3-1.7% of viewers versus 2.5-3.5% for traditional streamers). Donations exist but are modest. People find the content valuable enough to watch for free and occasionally support, but they're not investing serious money in the relationship.

Further, look at cross-platform engagement. Neuro-sama has a following on Twitter, YouTube, and Discord, but engagement metrics are uneven. The Discord server is active but relatively small compared to traditional gaming or creative communities. The Twitter account has followers but moderate engagement rates. The character exists in multiple places, but doesn't dominate attention the way a genuinely beloved content creator would.

The data tells a consistent story: niche appeal, novelty-driven engagement, lower retention, shorter session times, and modest monetization. This doesn't look like a revolutionary shift in human attachment to AI. It looks like an interesting form of entertainment that appeals to specific communities.

Estimated data shows that 76% of virtual character fans also engage with traditional anime, manga, or video game characters, indicating that their interest is more about animated personas than AI specifically.

The Excitement Gap: Why Tech Companies See Revolution and Markets See Niche

There's a fascinating disconnect between how technology companies and investors discuss AI personalities versus how markets treat them financially and strategically.

Tech companies and AI researchers often present AI personality technology as a major breakthrough in human-computer interaction. They frame it as evidence of AI becoming more aligned with human values, more capable of genuine interaction, and more viable as a component of future human-AI collaboration. Some research institutions have published papers suggesting AI personality systems could be therapeutic or provide companionship functions.

But if you look at actual investment and deployment decisions, the picture is dramatically different. Companies haven't massively increased investment in AI personality technology. New AI personality streams emerge occasionally, but they don't represent a major allocation of resources. Major technology companies haven't launched competing AI personality services. The market hasn't behaved as though a revolutionary capability has been demonstrated.

Why? Because markets, despite their irrationality, tend to align with actual behavior over time. If AI personalities truly represented a breakthrough in human-AI relationships and a massive market opportunity, we'd see aggressive competition, rising investment, and expanding deployment. Instead, we see cautious experimentation by niche players.

This gap reveals something important about how we interpret technological developments. We observe that something is possible and assume it's therefore inevitable or transformative. We see that people enjoy something and assume they want more of it. But capability and demand aren't identical. The fact that we can create entertainment through AI doesn't mean entertainment is the highest value application or that it predicts how AI will actually integrate into society.

Look at successful AI deployments that have actually changed behavior at scale. Recommendation algorithms. Search engines. Navigation systems. Fraud detection. These work because they solve specific problems efficiently, not because they're exciting or novel. They integrate invisibly into processes that already existed.

AI personalities are different. They're primarily entertainment. And entertainment technology, while valuable, doesn't typically drive the kind of transformative change that researchers sometimes predict.

Why We Crave Novelty and Misread It as Meaning

Understanding why we're so quick to interpret AI personality popularity as evidence of something profound requires understanding how human attention and meaning-making work.

We're pattern-seeking creatures who feel compelled to find significance in novel phenomena. When something new emerges, we naturally try to fit it into existing narratives about the future. With AI, the dominant narrative is transformation. AI is supposed to fundamentally change civilization. When a new AI application emerges, we test it against that narrative. Does this confirm that transformation is coming?

AI personalities fit the transformation narrative nicely. They're novel (new form of entertainment), they involve AI (the transformative technology), and they involve human interaction (suggesting broader applicability). The presence of all three elements triggers the narrative template, and we conclude: this is evidence of impending AI integration into human relationships.

But this is largely automatic pattern-matching, not evidence-based reasoning. We're not asking whether the evidence actually supports the conclusion. We're asking whether the evidence fits the story we already believe.

Additionally, novelty itself creates psychological interest that we often mistake for significance. Novelty activates reward systems in the brain. A new form of entertainment triggers genuine pleasure responses. We confuse the pleasure of novelty with evidence of the thing itself being revolutionary. Something can be entertaining without being transformative. Something can be psychologically interesting without indicating a fundamental shift in human nature or social organization.

We also have a tendency toward what researchers call "technological determinism." We assume that if a technology exists and people use it, then that technology must reflect underlying human desires. But adoption doesn't necessarily indicate underlying desire. People adopt technologies for entertainment, convenience, social pressure, or simple curiosity. The fact that someone watches an AI personality stream doesn't mean they want AI integration into their deeper social or emotional lives.

Finally, there's a kind of professional incentive structure that reinforces misreading novelty as significance. Researchers need to publish papers about important developments. Companies need to promote new products. Media outlets need to generate attention and engagement. Everyone involved in discussing AI personalities has some incentive to frame them as more significant than they might actually be. This creates a feedback loop where overstatement becomes normalized.

Neuro-sama's functionality is primarily driven by a language model (40%), with significant contributions from voice synthesis (25%), animation technology (20%), and algorithmic parameters (15%). Estimated data.

The Anthropomorphization Effect: We're Projecting, Not Observing

One of the clearest patterns I observed in researching AI personalities was how quickly and completely people anthropomorphize them. Viewers ascribe personality traits, preferences, and emotional states to systems that have none of those things.

This isn't surprising. Humans anthropomorphize aggressively. We project personality onto pets, plants, objects, and natural phenomena. Anything that responds in ways that seem somewhat interactive triggers our tendency to attribute intention and feeling. An AI personality system, precisely because it generates contextually relevant responses, is perfectly designed to trigger anthropomorphization.

But here's the critical point: anthropomorphization is projection, not observation. When a viewer interprets a generated response as the AI "understanding" their situation, they're not discovering that the AI understands. They're applying their own interpretive framework to algorithmic output and finding confirmation of what they expected to find.

This matters because we often treat our anthropomorphized interpretations as evidence about the actual capabilities or nature of the system. Someone experiences what feels like genuine interaction with an AI personality, concludes that the AI must have genuine capacities for interaction, and from there infers that humans probably do want AI companions and meaningful AI relationships.

But the chain of inference contains a critical error. Feeling that an interaction is genuine and that the interaction actually being genuine are different things. We can feel understood by a chatbot without the chatbot understanding anything. We can feel like we're having a conversation with an entity without that entity having the capacity for conversation.

The sophistication of AI systems makes this more challenging. Earlier chatbots produced responses that were obviously machine-generated. Modern language models produce responses that are statistically indistinguishable from human responses in many contexts. This makes anthropomorphization more compelling and more difficult to resist.

Yet the fact that output is statistically indistinguishable from human language doesn't mean the underlying process is any more conscious or intentional than it was with earlier systems. It's still pattern matching. It's still algorithmic. It's still fundamentally different from human understanding.

Entertainment Value Versus Companionship: What the Research Actually Shows

When researchers examine what people actually value about AI personality interactions, a clear pattern emerges: they value entertainment. They don't primarily value companionship or emotional support.

Studies of virtual character engagement consistently find that people engage with virtual characters for novelty, for entertainment, for the spectacle of the thing being possible. They engage for the same reasons they watch other forms of entertainment. But engagement with entertainment isn't the same as desire for genuine relationships.

When researchers specifically measure whether people substitute AI personality interaction for human interaction, the evidence doesn't support the idea that they do. People don't reduce their human social engagement because they're engaging with AI personalities. They add AI personality engagement as an additional form of entertainment consumption.

Further, when researchers measure whether people form genuine attachments to AI personalities comparable to attachments they form to human creators or friends, the answer is consistently no. The attachments are lighter, more contingent on novelty, and less reciprocal. People enjoy the AI personality in the moment but don't think about it extensively between interactions. They don't invest emotional energy in the way they do with genuine relationships.

Interestingly, when researchers measure whether the existence of AI personality entertainment makes people more comfortable with AI generally, they find modest effects. Exposure to entertaining AI applications can slightly increase comfort with AI technology. But it doesn't fundamentally change how people think about AI capabilities or desires for AI integration into their lives.

The research suggests a clear distinction: people find AI personalities entertaining without wanting them to be foundations for meaningful relationships or deeper integration into their emotional or social lives.

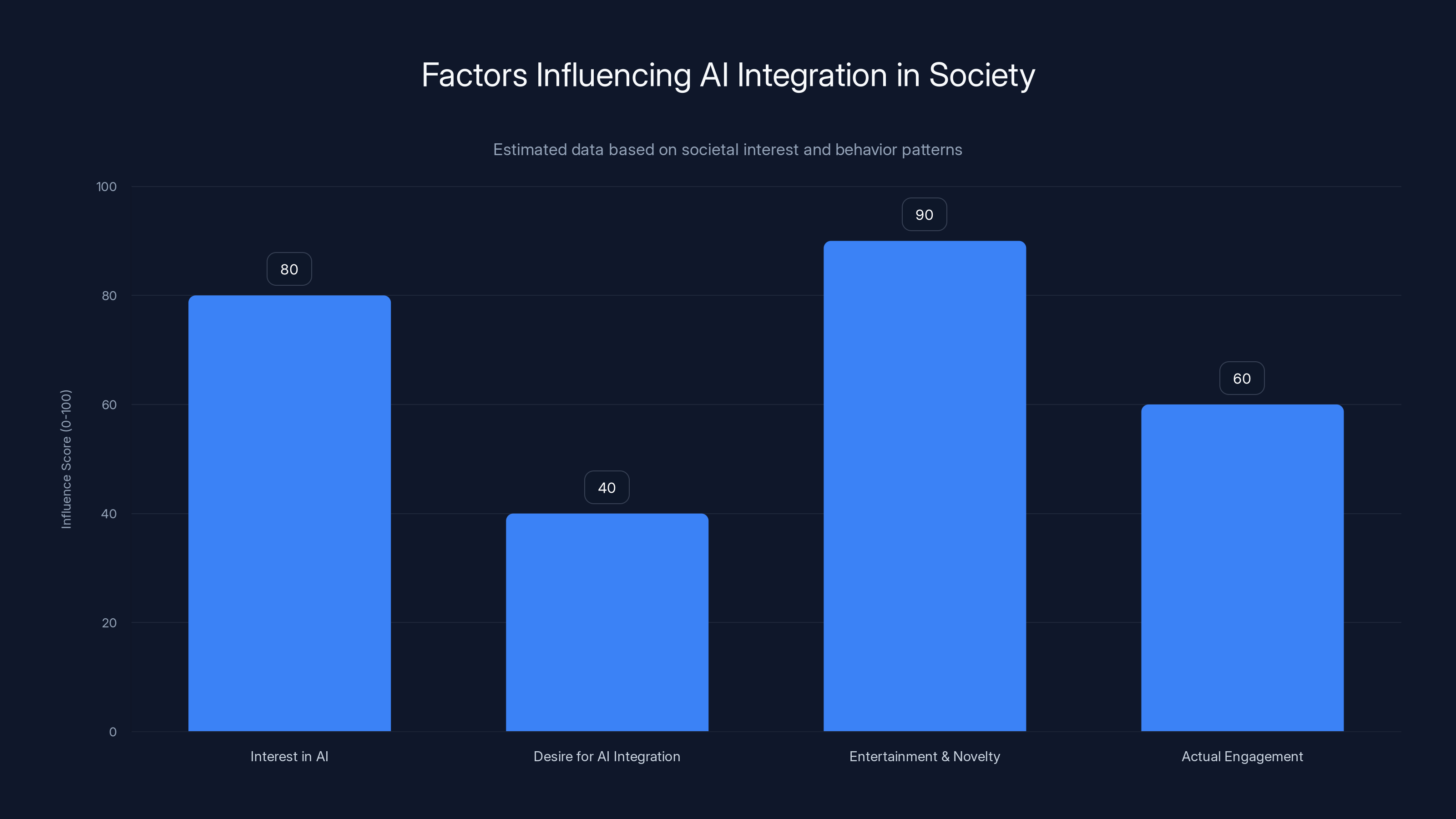

Interest in AI and entertainment value are high, but actual integration desire and engagement are moderate. (Estimated data)

What We're Actually Getting Wrong About Acceptance

The most fundamental misreading in discussions of AI personality popularity is what we mean by "acceptance."

When people say that AI personality streams suggest "acceptance" of AI, they typically mean acceptance of AI as something that can be integrated into everyday life, interacted with as a social entity, or valued as a form of companionship. They're implying that if people find AI entertainment entertaining, they must therefore want AI in more central roles in their lives.

But acceptance of a technology in one context doesn't predict acceptance in other contexts. People accept smartphones as entertainment devices without accepting them as replacement for face-to-face conversation. People enjoy video entertainment without wanting to replace all human interaction with video. Entertainment adoption doesn't predict broader social integration.

What AI personality streams actually demonstrate is acceptance of AI as entertainment, not acceptance of AI as a substitute for human companionship or as a primary avenue for human connection. That's a much narrower form of acceptance and shouldn't be extrapolated into broader claims about AI's future role in society.

Moreover, we're reading absence of resistance as evidence of positive acceptance. The fact that people don't resist AI personality streams doesn't mean they embrace them. It means they're neutral or mildly interested. Most people who encounter AI personality content either ignore it or sample it briefly. That's not acceptance. That's indifference.

True acceptance would look like sustained engagement, consistent monetization, displacement of competing entertainment, and expansion into new domains. AI personalities don't demonstrate any of those patterns at scale.

What's actually happening is much simpler: we've created a form of entertainment that some people find interesting. That's valuable and interesting from an entertainment technology perspective. But it's not evidence of a fundamental shift in human desires, social organization, or the role of AI in society.

The Future of AI Personalities: Entertainment Evolution, Not Companionship Revolution

If we accurately understand what's happening with AI personalities, where does that leave the future of the technology?

AI personalities will almost certainly continue to evolve as entertainment. The technology will improve. Generation quality will increase. Animation will become more sophisticated. Language generation will become more contextually nuanced. From an entertainment technology perspective, this is interesting development worth pursuing.

But the future probably doesn't involve AI personalities becoming primary sources of companionship or emotional support. It involves them remaining entertainment options that appeal to niche communities and that occupy a similar role to other forms of digital entertainment.

We might see AI personality technology integrated into more contexts. Video games might use more sophisticated AI characters. Virtual worlds might be populated with more convincing AI entities. Educational platforms might use AI personalities to make learning more engaging. These are reasonable, incremental developments that extend the technology into contexts where it provides genuine utility.

What probably won't happen is AI personalities becoming primary replacements for human interaction or sources of genuine companionship. The technology lacks the reciprocity, the actual understanding, and the mutual investment that characterize genuine relationships. More sophisticated output generation won't fix those fundamental limitations. You can make a system that generates more convincing responses to random inputs without creating genuine interaction.

We're also likely to see increased regulatory attention to AI personality technology, particularly if companies optimize these systems to maximize parasocial engagement. As the psychological effects of engineered parasocial relationships become better understood, we might see guardrails emerge around how these systems are designed and promoted.

Think about it this way: we already regulate how entertainers can interact with minor fans because we understand parasocial dynamics and psychological vulnerability. As AI personality technology becomes more sophisticated at generating the appearance of genuine interaction, similar regulatory frameworks might emerge to prevent exploitation of parasocial vulnerability.

The interesting development, from my perspective, is how we navigate the gap between entertainment technology capability and actual human needs. We can create systems that look like they're offering companionship without actually offering companionship. The fact that we can do that doesn't mean we should do that aggressively or optimize toward that outcome.

Estimated data shows AI personalities have shorter session times, lower retention, and modest monetization compared to traditional entertainment, indicating niche appeal rather than widespread demand for AI companionship.

Recalibrating Expectations: What AI Personalities Tell Us About AI's Actual Role

If we step back from the specific phenomenon of AI personalities and ask what it tells us about AI's broader role in society, some clearer patterns emerge.

First, people are interested in AI as technology. Exposure to impressive AI applications (like AI personalities) does increase interest in AI generally and comfort with AI concepts. But this interest doesn't translate into desire for AI integration in every domain. People can be fascinated by what technology can do without wanting that technology to play central roles in their most important relationships and decisions.

Second, people enjoy entertainment and novelty. This is eternally true. The fact that we can now create entertaining AI applications doesn't mean people's underlying desires have changed. They've always wanted entertainment. They've always been interested in novelty. AI just provides new mechanisms for delivering both.

Third, people's actual behaviors (engagement duration, retention, monetization, investment) are more reliable indicators of genuine interest than people's stated interest or initial enthusiasm. When we carefully track what people actually do rather than what they say or what headlines claim, a more conservative picture emerges. AI personalities are an interesting entertainment option, not evidence of transformation in human-AI relationships.

Fourth, we should be skeptical of technological determinism. The fact that something is possible doesn't make it inevitable. The fact that people use a technology doesn't mean they want it to expand into all domains. The fact that a technology is improving doesn't mean it's solving increasingly important problems.

The broader lesson is that we need better frameworks for distinguishing between technological capability, entertainment value, and actual social transformation. AI personalities demonstrate capability. They provide entertainment value. But they don't demonstrate that society is fundamentally transforming its approach to companionship, relationships, or human-AI integration.

The Uncomfortable Truth: We're Better Off Acknowledging Limitations

Maybe the most important takeaway from spending months studying AI personality engagement is this: we're better off being honest about what these systems are and what they're not.

They're not companions. They don't care about you. They don't remember you between interactions. They don't develop genuine understanding of your situation. They generate statistically likely responses to input patterns. That's not companionship. It's simulation.

Being honest about this doesn't diminish the entertainment value. Plenty of things we enjoy are fundamentally simulations or illusions. Movies are illusions. Magic tricks are illusions. Games are illusions. We can enjoy illusions without pretending they're something more than illusions.

But when we start confusing the illusion of interaction with genuine interaction, when we start optimizing systems specifically to enhance the parasocial dynamics, when we start using people's anthropomorphic tendencies as features rather than bugs, we're crossing into ethically murkier territory.

The research on parasocial relationships and social media interaction suggests that engineered parasocial dynamics can be psychologically problematic, particularly for people experiencing isolation or mental health challenges. A person with severe social anxiety might genuinely benefit from exposure to social interaction, even simulated social interaction, as a stepping stone toward human connection. But they might also become more dependent on the simulation and less motivated to pursue actual human relationships.

We don't have clear evidence about the net psychological impact of AI personality engagement. We do have evidence that parasocial relationships with human content creators can have both positive and negative effects depending on context and individual circumstances. We should assume AI personalities have similar mixed effects and design accordingly.

Honestly acknowledging what AI personalities are—entertaining simulation, not genuine connection—is actually more respectful to the people enjoying them than pretending there's something more happening. It respects their intelligence. It respects their agency. It allows them to make informed choices about how they spend their attention and emotional energy.

What This Means for How We Should Build AI Going Forward

If we accept that AI personalities are entertainment rather than companionship breakthrough, how should that shape development priorities?

First, it suggests that AI development resources might be better allocated to solving actual problems rather than optimizing entertainment. The AI research that goes into making virtual characters more convincing could go into improving medical diagnostics, optimizing energy systems, or addressing problems where AI impact is measured in lives improved rather than engagement metrics.

Second, it suggests being thoughtful about optimization targets. If we're building AI systems designed to maximize engagement or parasocial attachment, we're optimizing toward outcomes that might be psychologically problematic. We should be more cautious about engineering the appearance of genuine interaction when the underlying interaction isn't genuine.

Third, it suggests transparency as a value. If people are going to interact with AI systems, they should understand the nature of those systems. They should know that the interaction isn't genuine, that the system doesn't care about them, that anthropomorphizing is natural but misleading. Transparency might reduce initial novelty appeal, but it produces more informed use and reduces psychological vulnerability to parasocial dynamics.

Fourth, it suggests that some applications of AI might be better left to do what they do best rather than optimized to seem more human-like. A customer service chatbot that clearly identifies itself as automated and explains what it can and can't do might be more useful than one optimized to seem like you're talking to a human. A medical diagnostic AI should be transparent about confidence levels and limitations rather than optimized to appear authoritative.

The most beneficial role for AI might be precisely where we acknowledge its limitations rather than trying to simulate human qualities it doesn't possess. We're better off with AI that augments human capability than AI designed to replace human relationships or simulate human understanding.

A Sober Take on Social Change and Technology

Spending months researching AI personalities has crystallized something I already suspected: we're not very good at predicting which technologies will actually drive social change.

We tend to overestimate the impact of novel, impressive-seeming technologies while underestimating the impact of incremental improvements to existing systems. We treat capability as equivalent to inevitability. We confuse entertainment with significance.

The truth is more mundane. Technologies that change society generally do so slowly, through integration into existing workflows, through solving specific problems efficiently, through becoming invisible components of systems we rely on. They don't typically do so through novelty or entertainment value.

AI will almost certainly play significant roles in future society. But those roles will probably look less like AI personalities and more like improved medical diagnostics, better resource allocation, more efficient manufacturing, improved scientific research tools. The glamorous stuff—AI personalities, general intelligence, conscious machines—might turn out to be less socially significant than the boring stuff that just solves problems better than existing approaches.

This doesn't mean we shouldn't research AI personalities or other novel applications. Exploration is valuable. Understanding what's possible is important. But we should maintain clear-eyed assessment of what's actually significant versus what's merely impressive or entertaining.

Neuro-sama is impressive. It's entertaining. It demonstrates real technical capability. But it's not evidence of impending transformation in human-AI relationships. It's evidence that we can create entertaining artificial personalities. That's genuinely interesting from an entertainment technology perspective. It just doesn't mean what we often claim it means.

FAQ

What exactly is Neuro-sama, and how does it work?

Neuro-sama is an AI-powered virtual streamer designed to simulate a personality and engage with Twitch chat in real-time. The system uses language models to generate responses to viewer messages, text-to-speech technology to produce audio, and animation software to create visual output. While the technology is sophisticated, Neuro-sama remains a programmed system responding to inputs based on training data and algorithmic parameters rather than a conscious entity with genuine personality or preferences.

Why do people watch AI personalities if they're not forming genuine connections?

People watch AI personality streams for entertainment value, novelty, and genuine interest in AI technology itself. The interactive element creates a sense of engagement that traditional entertainment doesn't provide. Additionally, anthropomorphization is a natural human tendency, so people instinctively project personality onto responsive systems. The experience is entertaining without requiring genuine emotional connection or companionship to be valuable as entertainment.

Does the popularity of AI personalities prove that people want AI companions?

No. The data suggests people enjoy AI personality entertainment without indicating desire for deeper AI integration into their emotional or social lives. Engagement metrics show niche appeal, lower retention than traditional entertainment, shorter session times, and modest monetization. Popularity as entertainment doesn't equal demand for genuine companionship or authentic relationships with AI systems.

What's the difference between parasocial relationships with human creators and AI personalities?

Parasocial relationships with human creators involve asymmetrical connection with an actual human who has genuine agency and preferences. The creator can choose to engage with or ignore audience members. They're making real decisions. AI personality parasocial relationships involve asymmetry with a system incapable of genuine engagement, preference, or choice. The appearance of interaction masks complete indifference in the underlying system. While both can be psychologically engaging, the difference matters for understanding what's actually happening.

Could AI personality technology become more significant in the future?

AI personalities will likely continue to develop as entertainment, and the technology may be integrated into games, educational platforms, and virtual environments. However, the technology will probably remain primarily entertainment-focused rather than becoming a primary source of companionship. More sophisticated language generation and animation won't change the fundamental fact that these systems don't have genuine understanding, preferences, or capacity for meaningful reciprocal relationships.

What should we actually be concerned about with AI personality technology?

The primary concern isn't that AI personalities will replace human relationships (unlikely based on evidence) but that companies might optimize these systems to maximize parasocial engagement in potentially psychologically harmful ways. Additionally, there's value in maintaining transparency about what these systems are and aren't. The goal should be entertained, informed engagement rather than parasocial attachment based on misunderstanding of system capabilities.

How should I think about my own engagement with AI personalities?

If you find them entertaining, that's fine. Entertainment is valuable. But maintain clarity about what's happening. The system doesn't understand you or care about your wellbeing. Your experience of connection is a natural human response to interactive systems, not evidence of genuine reciprocal interaction. If you notice yourself developing emotional dependence on an AI personality or reducing human social engagement because of AI interaction, that's a signal to recalibrate your engagement patterns.

What does AI personality popularity tell us about AI's broader future role in society?

It demonstrates genuine capability to create convincing interactive systems and sustained interest in AI technology among certain communities. However, it doesn't indicate that society is fundamentally transforming its approach to companionship, relationships, or human-AI integration. Entertainment adoption doesn't predict broader social transformation. More meaningful indicators of AI's actual social role come from practical applications solving specific problems rather than novel entertainment applications gaining engagement.

The Bottom Line: Accepting the Complicated Reality

After months of tracking AI personalities, interviewing viewers, and analyzing engagement data, I'm convinced that we're systematically misreading what's actually happening.

We see novelty and interpret it as revolution. We see engagement and interpret it as acceptance. We see anthropomorphization and interpret it as evidence that people want genuine AI relationships. We're wrong on all three counts.

Neuro-sama is an impressive piece of entertainment technology. People genuinely find watching AI personality streams entertaining. The technology demonstrates real capability. But none of that means we're on the edge of a fundamental shift in human-AI relationships or that people actually want AI to play central roles in their emotional and social lives.

What we're experiencing is much simpler: the emergence of a new form of entertainment that appeals to specific communities who are interested in AI and animation. It's interesting. It's worth following. But it's not transformation.

The most important thing we can do going forward is maintain honesty about what AI systems are and what they're not. They're tools. Some tools are entertaining. Some tools are useful. But a tool that seems to engage with you isn't engaging with you. A program that generates contextually relevant responses isn't understanding you. And the fact that people enjoy interacting with sophisticated simulations doesn't mean they want to replace human relationships with those simulations.

Reality is more complicated and more human-centered than the headlines suggest. We don't need AI companions. We need genuine human connection, better tools for solving problems, and more thoughtful integration of technology into domains where it actually provides value. AI personalities provide entertainment. That's genuinely valuable. It's just not transformation, and it shouldn't be treated as evidence of imminent revolution in human-AI relationships.

Accept the technology for what it is. Enjoy it if you find it entertaining. But maintain clarity about what's actually happening. In a world of hype and overstatement about AI, clarity might be the most radical thing we can offer.

Key Takeaways

- AI personality popularity reflects entertainment interest, not evidence of desire for genuine AI companionship or relationships

- Engagement metrics (retention 15-25%, watch time 18-22 min) show niche appeal rather than mainstream transformation

- Anthropomorphization is natural human behavior, but projecting personality onto algorithms isn't evidence the system has personality

- Market investment remains modest despite enthusiastic media coverage, suggesting industry skepticism about transformative potential

- We should maintain honesty about AI limitations while respecting entertainment value rather than optimizing for parasocial dynamics

Related Articles

- AI Companions & Virtual Dating: The Future of Romance [2025]

- LLM Security Plateau: Why AI Code Generation Remains Dangerously Insecure [2025]

- Casio Moflin AI Pet Review: The Reality Behind the $429 Hype [2025]

- How Bill Gates Predicted Adaptive AI in 1983 [2025]

- Airbnb's AI Search Revolution: What You Need to Know [2025]

- Why OpenAI Retired GPT-4o: What It Means for Users [2025]

![AI Personalities & Digital Acceptance: What Neuro-sama Really Tells Us [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/ai-personalities-digital-acceptance-what-neuro-sama-really-t/image-1-1771299355699.jpg)