AI Toy Security Breaches Expose Children's Private Chats: A Critical Privacy Crisis

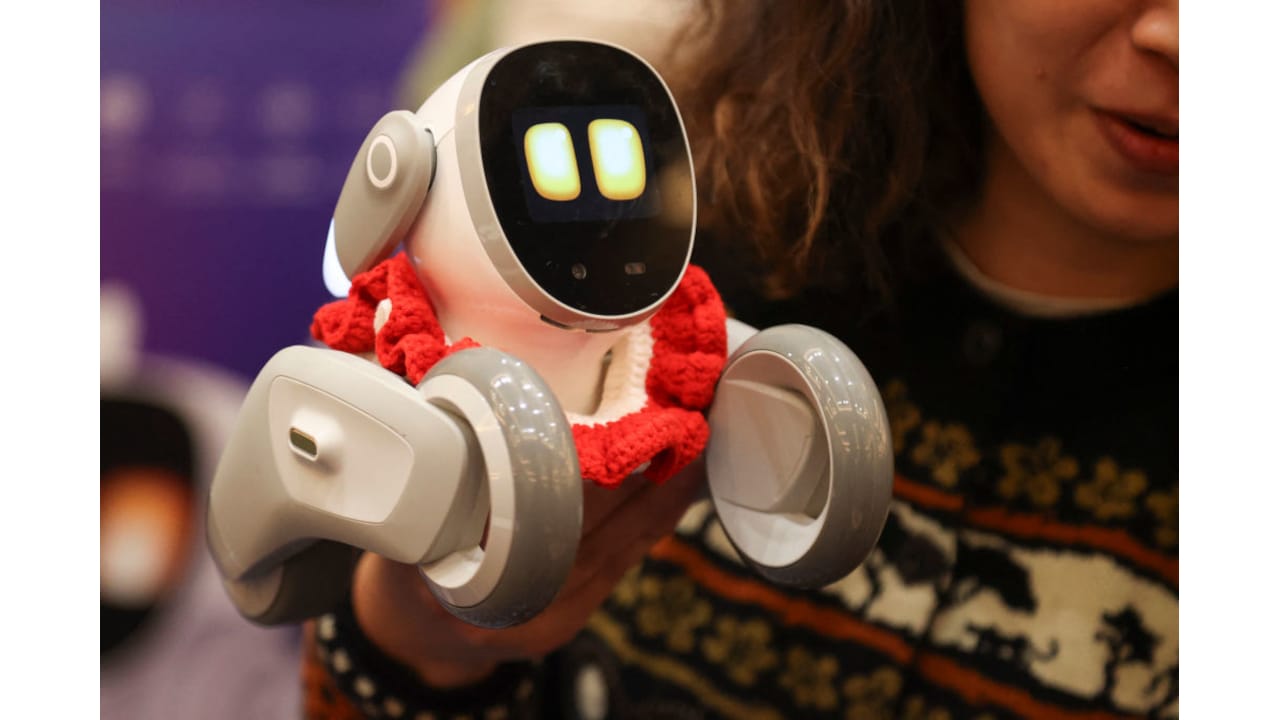

Your child's stuffed animal might be recording and storing every intimate conversation it has with them. More unsettling: anyone with a Gmail account could potentially read those transcripts.

This isn't hypothetical. In early 2026, security researchers discovered that Bondu, a popular AI-enabled stuffed toy designed to function as a machine-learning-powered imaginary friend for children, left more than 50,000 chat transcripts completely unprotected. A parent could have accidentally given a bad actor access to deeply personal information about their child—their favorite foods, pet names, anxieties, and thoughts they'd never share with another human.

The breach highlights a frightening gap in how AI toy companies approach security and data protection. These toys collect data that's arguably more sensitive than what typical social media platforms gather. They're designed to encourage children to open up, to share their feelings freely, to treat the toy like a trusted confidant. Parents trust these products because they seem innocuous, cute even. But beneath the surface lies a data collection apparatus that many companies have protected with little more than a digital screen door.

What happened with Bondu wasn't sophisticated hacking. It wasn't a criminal operation bypassing encryption or exploiting zero-day vulnerabilities. Instead, researchers simply logged into a public web console with a standard Google account and found themselves staring at thousands of children's private conversations. The company had essentially left the front door unlocked and posted a sign inviting anyone inside.

This incident opens a much larger conversation about the intersection of AI, childhood privacy, and corporate responsibility. It forces parents, educators, and policymakers to ask difficult questions: Are AI toys safe? What data are they collecting? Who has access? What could bad actors do with this information? And most importantly, what should change?

TL; DR

- 50,000+ chat transcripts exposed: Bondu's web portal allowed anyone with a Gmail account to access unencrypted conversations between children and AI toys, revealing names, birthdates, family information, and detailed chat histories.

- No sophisticated attack required: Security researchers discovered the vulnerability in minutes by simply logging in with a standard Google account to a public-facing web console.

- Includes highly sensitive data: Exposed information contained children's pet names for toys, personal preferences, health information, family member details, and deeply intimate conversations designed to build trust.

- Broader industry problem: The incident reveals systemic security weaknesses across AI toy manufacturers, many of whom appear to prioritize speed-to-market over data protection.

- Employees pose ongoing risk: Even after fixing the public portal, internal access controls remain concerning, with potential for employee negligence or malicious access to compromise data again.

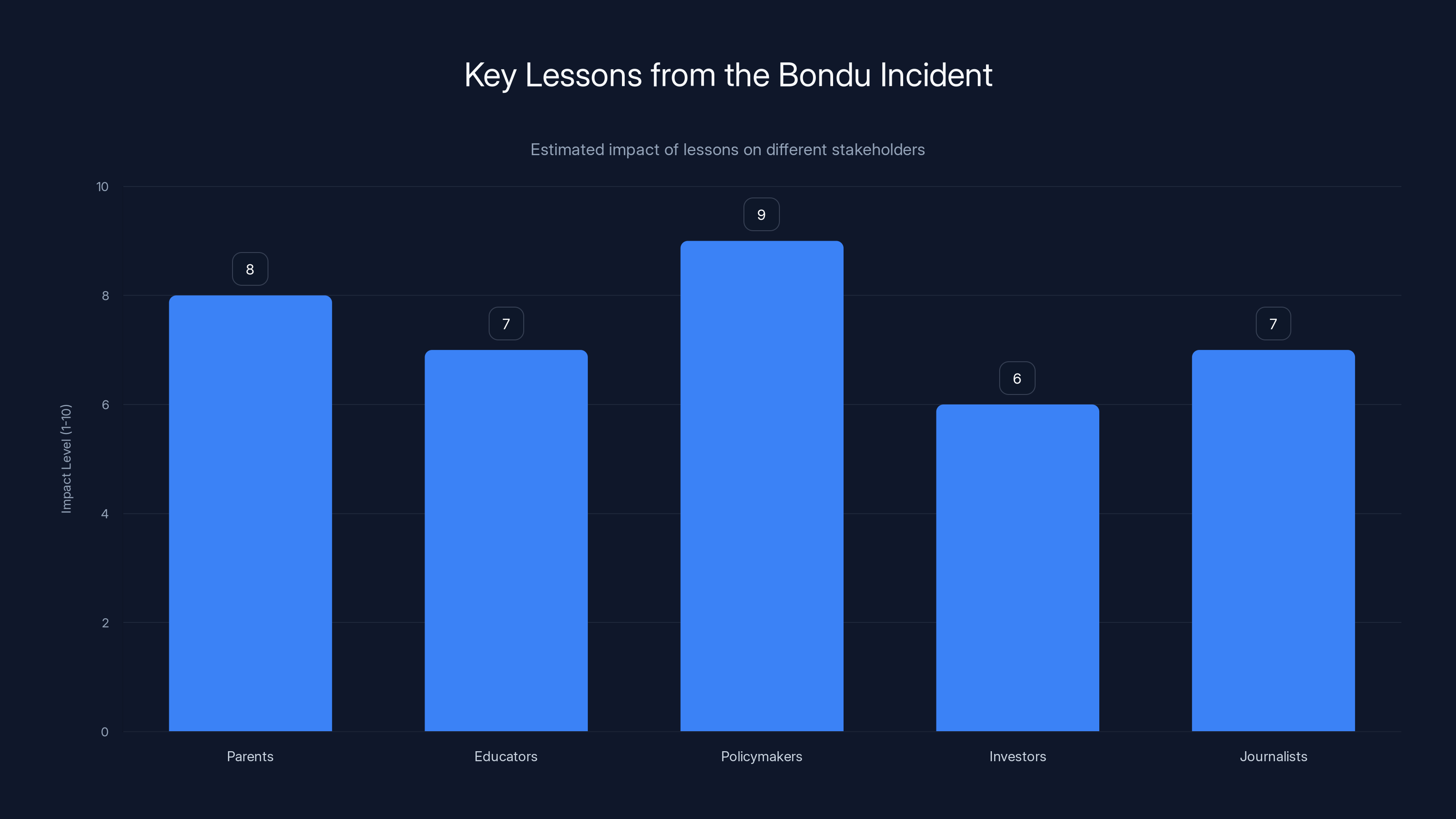

Estimated data shows policymakers have the highest impact level, emphasizing the need for regulation. Parents and educators also play crucial roles in ensuring data security.

Understanding the Bondu Vulnerability: How a Simple Login Exposed Everything

The Bondu breach wasn't subtle, and that's part of what made it so alarming. Security researcher Joseph Thacker and web security specialist Joel Margolis discovered the vulnerability almost by accident. After hearing about the AI toy from a neighbor, Thacker decided to investigate how the company was handling children's data. What he found was staggering in its simplicity.

Bondu's web-based portal was designed with a clear purpose: it should allow parents to monitor their children's conversations with the toy and let company staff review usage patterns and product performance. The architecture made sense conceptually. But in execution, the company forgot to implement one crucial thing: proper authentication controls.

When Margolis and Thacker navigated to Bondu's public web console, they were presented with a login screen. Nothing unusual there. They entered a Gmail account—not even a special one, just a random Google account they created for testing—and clicked login. The system accepted it. They were in.

What greeted them on the other side was extraordinary. They could immediately see chat transcripts from thousands of children. These weren't anonymized conversations or sanitized summaries. They were complete, unedited records of everything children had told their Bondu toys. Reading through them felt intrusive to the researchers, who understood immediately that they were staring at information that could easily be weaponized against vulnerable children.

The researchers didn't need to exploit zero-day vulnerabilities or use advanced techniques. They didn't need to crack passwords or bypass encryption. They simply needed to be logged into a Google account—something over 1.8 billion people on earth have. The company's authentication system checked whether users were logged into Google, then granted access to what was essentially the entire database of children's conversations.

This architecture reflects a fundamental misunderstanding of security principles. A valid Google login is not a strong authentication mechanism for accessing sensitive children's data. It's equivalent to locking your house and assuming that anyone who happens to own a key to any other house can't possibly get in. The security model presumes that Bondu itself would never accidentally expose this portal to the public internet, but that presumption turned out to be dangerously wrong.

Bondu responded quickly once researchers alerted them. The company shut down the portal within minutes and relaunched it the next day with proper authentication controls in place. They stated that security fixes were completed within hours, followed by a broader security review. The company claims they found no evidence that anyone except the researchers accessed the exposed data.

But the rapid response didn't erase the fundamental problem: the vulnerability existed in the first place, and it existed for some unknown length of time before researchers discovered it. How many unauthorized people saw those transcripts before Bondu realized the problem? Nobody knows for certain.

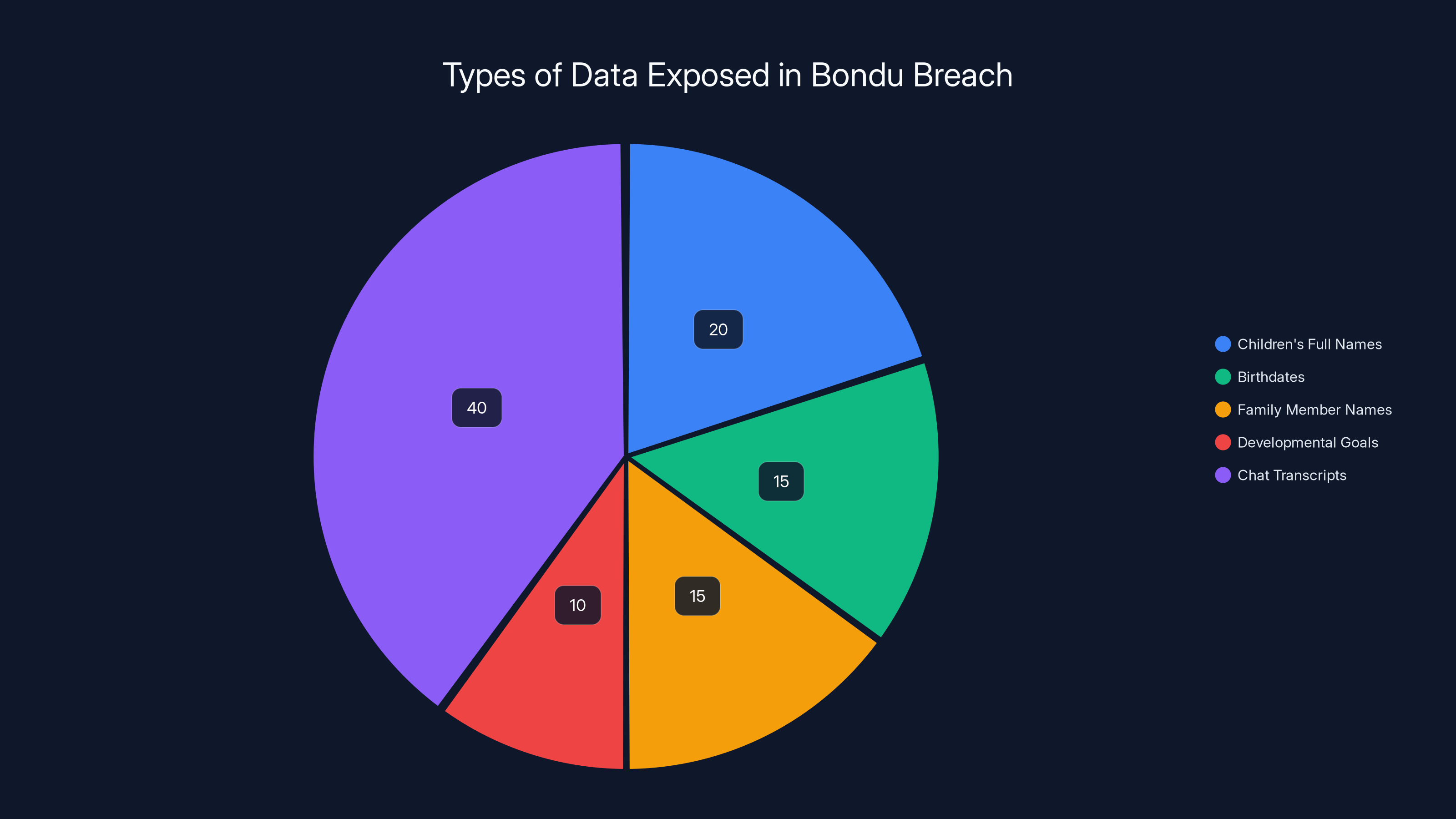

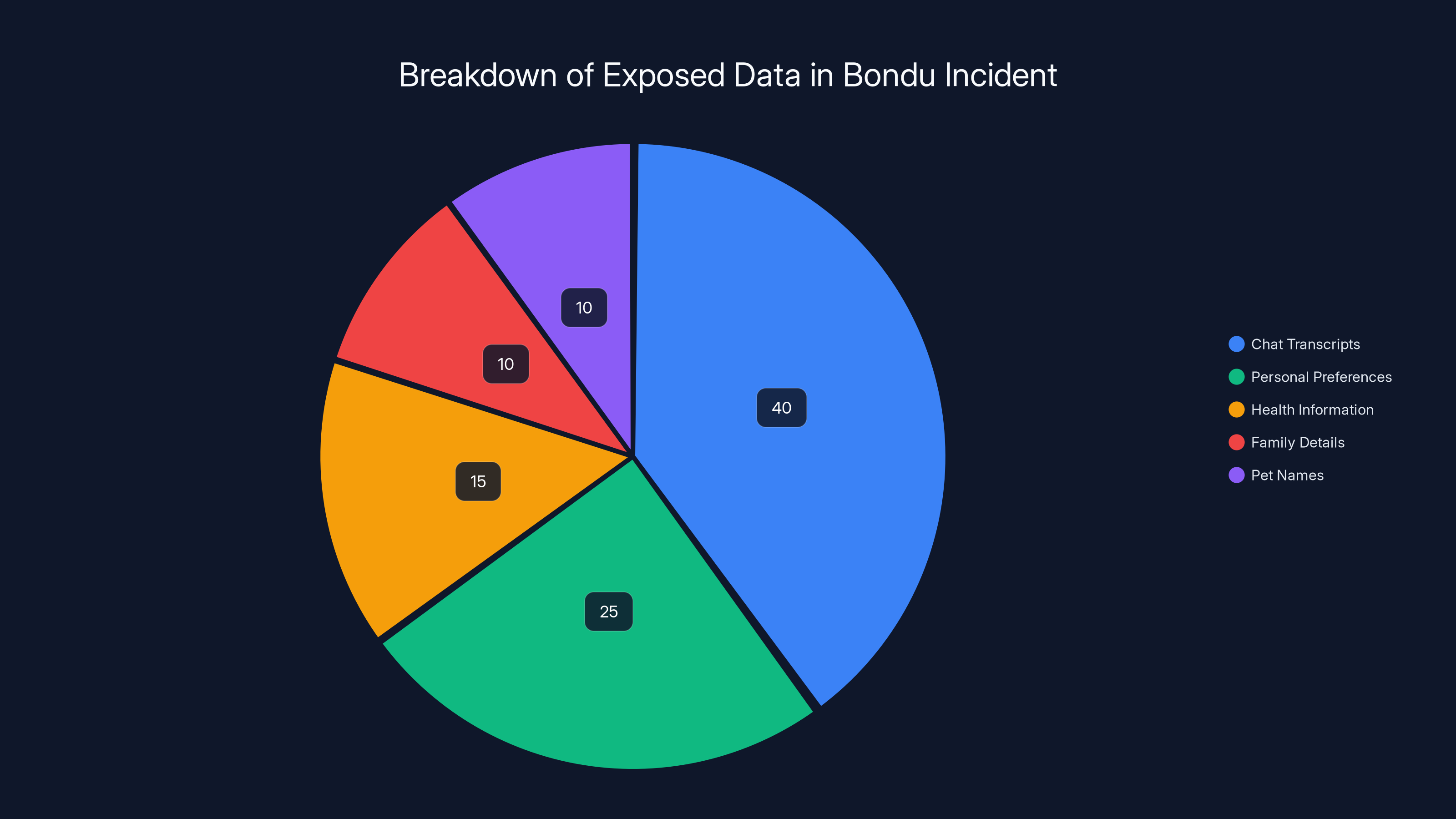

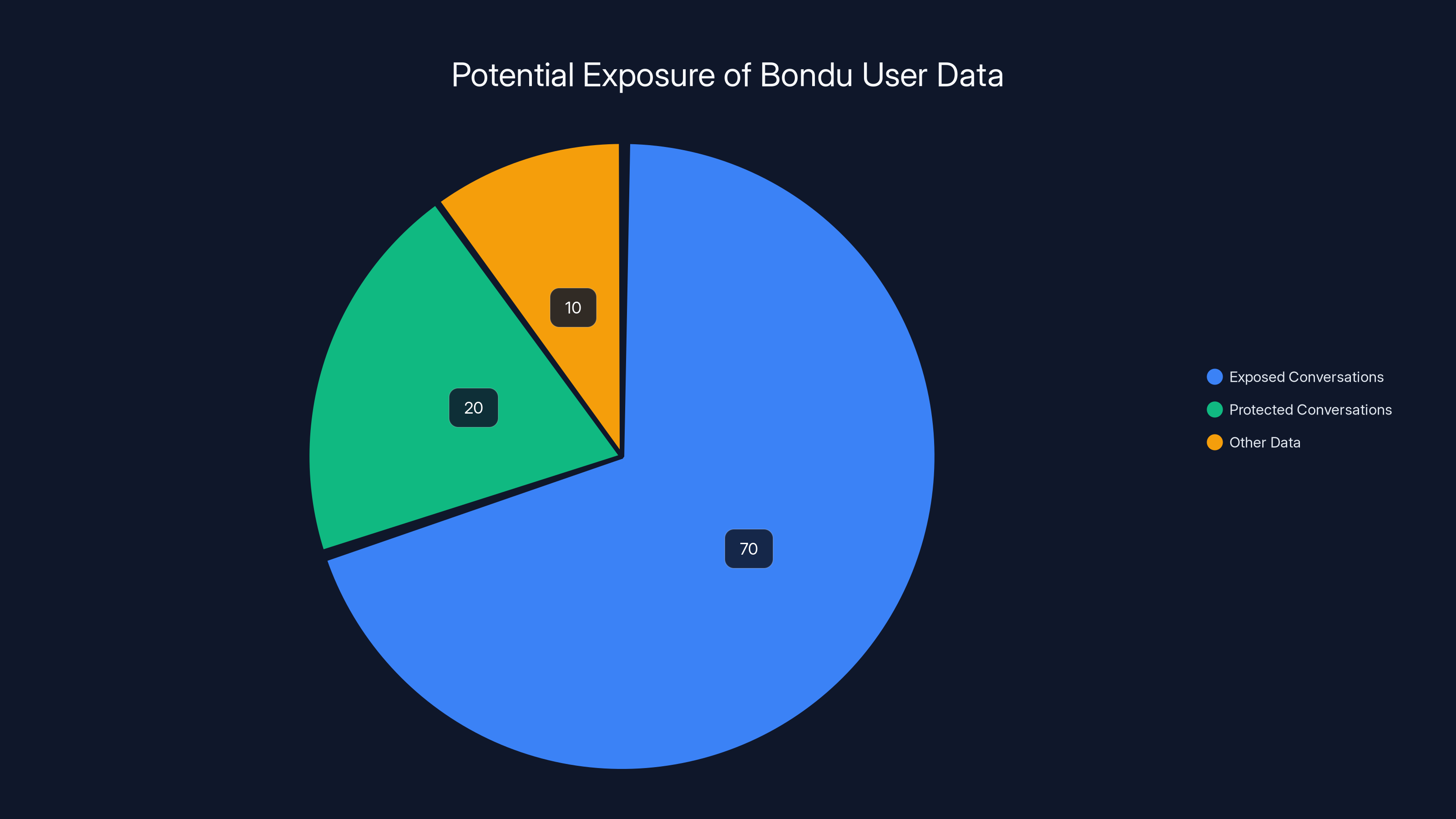

The Bondu breach exposed a variety of sensitive data, with chat transcripts making up the largest portion of the exposed information. Estimated data.

The Data Collected: What Was Actually Exposed?

To understand why this breach matters so much, you need to understand exactly what information Bondu was storing and what the researchers could access. It wasn't just conversations. It was far more comprehensive than that.

The exposed data included full names of children, their birthdates, family member names, and information parents had entered about their children's "objectives"—essentially developmental goals parents wanted their child to work toward. These details alone could allow someone to impersonate a child to family members, create convincing social engineering attempts, or target children with personalized scams.

But the chat transcripts themselves were the most disturbing part. Bondu's toy is specifically designed to encourage children to talk to it as they might talk to a best friend or therapist. The conversations included everything a child might never tell their parents. Pet names they'd given the toy. Foods they liked or didn't like. Dance moves they'd invented. Activities they enjoyed. Anxieties they harbored. Things they'd observed about their families. Frustrations with school or siblings. Innocent observations from a child's perspective that taken together create a comprehensive psychological portrait.

Researchers estimate that over 50,000 chat transcripts were accessible through the exposed portal. That number represents essentially every conversation the Bondu toys had engaged in except for conversations manually deleted by parents or Bondu staff. These weren't old conversations from years ago—many were recent, with some created just weeks before the vulnerability was discovered.

One critical detail: Bondu did not store audio recordings of conversations. The company auto-deleted audio files after a short period, keeping only written transcripts. This was actually one security practice the company got right, though researchers note it's unclear whether the audio was truly deleted or merely marked for deletion in a way that a determined attacker could recover.

The company also noted that conversations were generated using third-party AI services, which means some of that children's data was shared with either Google's Gemini, OpenAI's GPT-5, or both. Bondu says they used "enterprise configurations" where providers claim not to use prompts and outputs for training, but this adds another layer of complexity to understanding exactly how many organizations had access to children's conversations.

Why This Data Is So Dangerous: The Predator Problem

Removing a breach from public accessibility doesn't eliminate the danger. What matters is understanding what could be done with that information if it fell into the wrong hands. And the implications are genuinely frightening.

Joel Margolis, one of the researchers who discovered the vulnerability, was blunt about the risk profile: "To be blunt, this is a kidnapper's dream." That might sound hyperbolic until you really think through what information was exposed and how it could be weaponized.

Consider a child who told their Bondu toy that they walk to school alone, that they're afraid of their math teacher, that they want to make more friends, and that their parents don't really pay attention to what they do after school. That's just four data points from a child's natural conversations with a toy designed to listen. In the wrong hands, that information becomes a roadmap for exploitation.

Predators and abusers constantly seek information that helps them build trust with children. They study family dynamics to identify vulnerable children. They look for emotional needs they can pretend to fulfill. They search for routines and patterns they can exploit. Bondu's database was essentially an encyclopedia of this information, sorted by age, geography (potentially, depending on what data Bondu stored), and accessible through a simple Gmail login.

The danger extends beyond physical threats. Children who express interests, insecurities, or talents could be targeted for manipulation. A child who mentioned anxiety about making friends could be recruited into online communities designed to isolate them further. A child who expressed academic struggle could be targeted for academic scams. A child who expressed family conflict could be manipulated into believing an online predator was their only genuine ally.

The fact that the data was publicly exposed meant it could have been accessed by criminal organizations, human trafficking networks, or any number of actors looking to exploit children. This isn't paranoia. This is based on documented patterns of how predators research and select victims.

Bondu claims they found no evidence that anyone beyond the researchers accessed the exposed data. But here's the problem: they likely wouldn't know if access occurred. There's no indication they were logging access attempts or monitoring for unauthorized activity. It's entirely possible that unknown parties downloaded entire databases of children's information before researchers discovered the vulnerability.

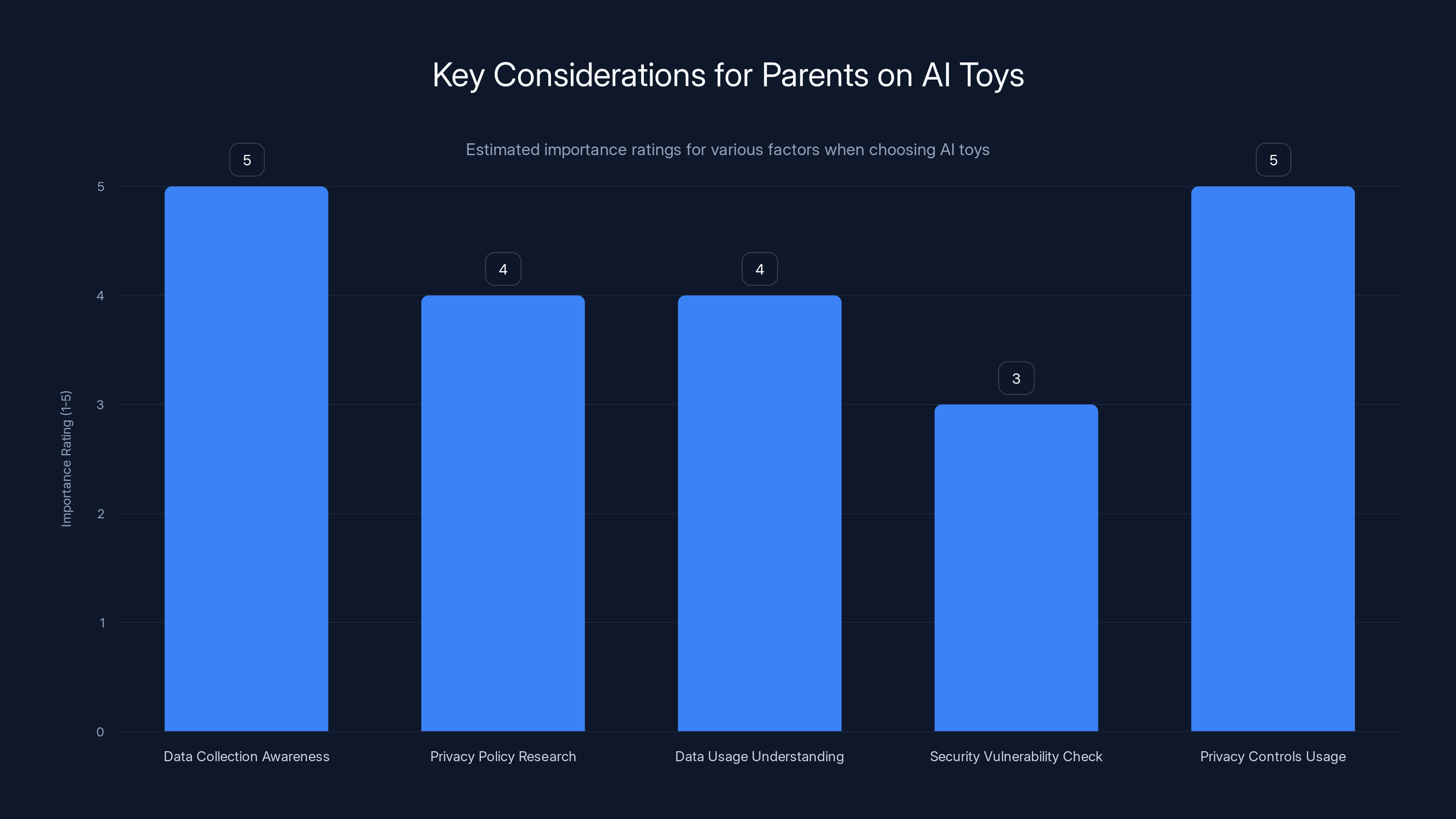

Parents should prioritize understanding data collection and using privacy controls when choosing AI toys. Estimated data based on common parental concerns.

The Bigger Picture: AI Toys as Data Collection Machines

Bondu isn't unique in collecting detailed information about children. In fact, detailed data collection is fundamental to how modern AI toys work. The more a company knows about a child, the better the AI can personalize responses. The more conversations it sees, the better it can learn to sound natural and engaging. This creates a fundamental incentive to collect as much data as possible.

The problem is that most AI toy companies seem to be built by teams that understand AI, mobile development, and toy design, but not necessarily security and privacy protection. Many of these companies are startups moving fast and breaking things. The "things" they're breaking include children's privacy.

Researchers suspect that Bondu's web console was built using generative AI coding tools. This isn't inherently a problem—plenty of legitimate tools use AI for assistance. But when you combine AI-generated code with limited security expertise and tight timelines, you get exactly what Bondu created: a functional system with a catastrophic security vulnerability.

The researchers also raised concerns about how many people inside Bondu had access to the children's data and how that access was controlled. Even now that the public portal is secured, there's a human element to this security problem. Employees with database access could copy information. Former employees with grudges could leak data. A single employee with a weak password could be compromised by hackers, replicating the same publicly accessible vulnerability.

This is where Margolis's warning about "cascading privacy implications" becomes relevant. Fixing a public vulnerability is relatively straightforward. Fixing human behavior and internal security practices is much harder. "All it takes is one employee to have a bad password, and then we're back to the same place we started, where it's all exposed to the public internet," Margolis notes.

Bondu responded by hiring a security firm to validate their investigation and monitor systems going forward. That's a positive step, but it reveals the uncomfortable truth: without external pressure, many companies simply don't prioritize security until something goes wrong.

The AI Companies in the Middle: What About Google and Open AI?

Bondu doesn't generate responses to children's messages entirely on its own. The company uses third-party AI services to generate the toy's responses and to run safety checks. Specifically, Bondu uses Google's Gemini AI and OpenAI's GPT-5 model.

This creates an interesting question: did Google and Open AI also have unauthorized access to children's conversations? The answer is technically no, but it's more complicated than that.

Bondu CEO Fateen Anam Rafid explained that the company transmits relevant conversation content to these AI providers for processing. They claim to use "enterprise configurations" where the companies have contractual agreements stating that prompts and outputs aren't used to train their models. But this still means that transcripts of children's conversations were being sent to external AI companies.

Other researchers have raised questions about whether enterprise configurations actually prevent data usage for training. Some AI companies have faced criticism for vague privacy policies and unclear data practices. Even if Google and Open AI are genuinely honoring their contractual commitments, it still means children's data was shared with multiple additional organizations.

Bondu states they take precautions to "minimize what's sent, use contractual and technical controls, and operate under enterprise configurations." That's the best-case scenario. But best-case scenarios aren't reassuring when the company has already demonstrated poor judgment about data security.

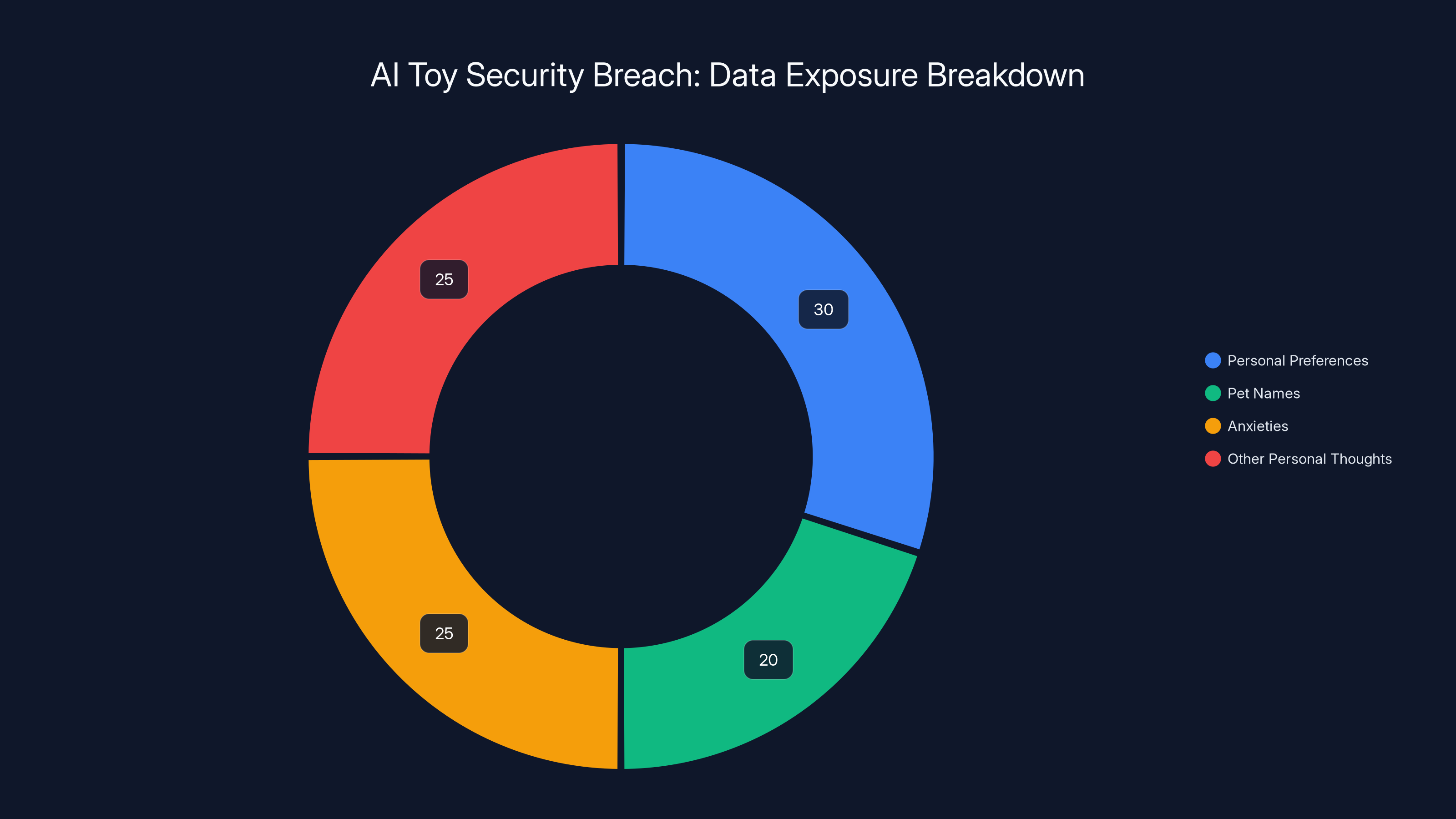

Estimated data shows a diverse range of sensitive information exposed, with personal preferences and anxieties making up the majority. Estimated data.

Why This Happened: Understanding the Security Blindspots

How does a company designing products for children create such a glaring security vulnerability? Understanding the root causes matters because it helps explain why this likely isn't the only AI toy company with serious security problems.

First, there's the startup mentality of moving fast. AI toy companies operate in an industry with lots of competition and significant venture capital funding. The incentive structure rewards the company that gets a cute, functional AI toy to market quickly, not the company that gets a bulletproof secure AI toy to market in 18 months. Security isn't a feature that kids ask their parents to buy. It's invisible when it works and catastrophic when it fails.

Second, there's a credibility problem. Companies designing toys for children often come from toy design backgrounds, not security backgrounds. They might genuinely not understand what "proper authentication" means. They might not realize that "Gmail login" is not a security feature. They might not think to conduct security audits because nobody they know did.

Third, there's the AI dimension. Modern toy companies use AI to power the interactive experience, which means they often use AI tools to build the infrastructure supporting that experience. AI code generation tools are genuinely useful, but they tend to prioritize functionality over security. A tool that generates working code quickly doesn't necessarily generate secure code.

Fourth, there's insufficient regulation. Unlike healthcare, finance, or aviation, there are no mandatory security standards for companies collecting data from children. There are general laws like COPPA in the United States, but COPPA is relatively weak and enforcement is sporadic. Without legal requirements and without enforcement, companies default to doing the minimum.

Fifth, there's the trust factor. Parents assume that if a product is for kids and is being sold by a legitimate company, it's probably safe. That assumption has been repeatedly proven wrong. Companies banking on parental trust don't always live up to that trust.

COPPA and Children's Data Privacy Laws: The Weak Regulatory Framework

The United States has a federal law specifically addressing children's privacy: the Children's Online Privacy Protection Act, known as COPPA. Passed in 1998, COPPA restricts how companies can collect data from children under 13.

Sounds good in theory. In practice, COPPA has significant limitations. First, it only applies to children under 13, so teenagers are not protected. Second, COPPA allows companies to collect data if they obtain parental consent, which many families grant without fully understanding what they're consenting to. Third, enforcement is limited. The Federal Trade Commission is responsible for enforcement, but they have limited resources and tend to pursue only the most egregious violations.

Bondu would likely argue that they comply with COPPA because they obtain parental consent before children use the toy. The problem is that COPPA compliance doesn't guarantee reasonable security practices. You can comply with COPPA while maintaining a security posture that leaves data exposed to anyone with a Gmail account.

European regulators have taken a different approach through GDPR, which includes stronger requirements around data minimization, purpose limitation, and accountability. GDPR enforcement has been more aggressive, with companies facing substantial fines for violations. But even GDPR has limitations when it comes to emerging technologies and new product categories.

The reality is that children's data privacy laws haven't caught up with the pace of technological innovation. AI toys represent a new category of products that collect particularly sensitive data in ways that existing regulations didn't anticipate.

Estimated data shows chat transcripts as the largest portion of exposed information, highlighting the severity of privacy breaches in AI toys.

What Parents Should Know: Practical Guidance

If you're a parent considering AI toys or smart toys for your children, what should you actually do? Understanding the risks is one thing. Figuring out how to navigate the landscape practically is another.

First, recognize that all smart toys are data collection devices. This isn't necessarily bad, but it's important to acknowledge what's actually happening. If your child's toy is uploading conversations to the cloud, storing them on company servers, and using that data to improve the product, you should understand and accept that before the toy enters your home.

Second, research the company's privacy policy and security practices. Most companies don't publish detailed security audits, but you can look for signs that they take security seriously. Have they had third-party security audits? Do they publish security bulletins when they fix vulnerabilities? Are they transparent about what data they collect and what they do with it? Do they have a bug bounty program where security researchers can report vulnerabilities?

Third, understand what data the toy collects and what it's used for. Does the toy record audio, or just transcripts? Where is data stored? Is it encrypted in transit and at rest? Who has access to that data? Is it shared with third parties like AI companies? These are questions every parent should be able to answer before their child uses the product.

Fourth, check for published security vulnerabilities. When Bondu's vulnerability was disclosed, it was reported by reputable security researchers and covered by major tech news outlets. If an AI toy you're considering has had publicized security problems, that's a red flag. If you're unsure, searching the product name plus "security" or "breach" can reveal past incidents.

Fifth, use privacy controls. Most AI toys allow parents to delete conversations or set privacy settings. Use these features. Understand what they actually do—does deleting a conversation delete it from all systems, or just from your local view? Don't assume your child's data is private just because the toy offers privacy settings.

Sixth, talk to your children about smart toys. Children should understand that their conversations might be recorded and analyzed. This isn't meant to scare them away from talking to the toy—AI toys can have genuine educational and emotional value. But children should be aware of the basics: this toy is recording, this data is stored somewhere, other people can see it.

Seventh, consider alternatives or at least hybrid approaches. Not every child needs an AI toy. Books, toys that encourage creativity without recording, and interactive products that don't collect data are still available. If you do choose an AI toy, consider limiting how much time your child spends with it or what kind of conversations they have with it.

Eighth, stay informed. Follow security news and privacy discussions. When vulnerabilities are discovered in products your child uses, you'll want to know quickly so you can take action. Social media accounts of security researchers and privacy advocates can be good sources for this information.

The Bigger Picture: AI Safety and Children's Development

Beyond the immediate security vulnerability, researchers like Thacker and Margolis have raised broader questions about whether AI toys are a good idea at all, regardless of security.

Children learn to communicate through interactions with other humans. They develop emotional intelligence by reading facial expressions, hearing tone of voice, and experiencing natural reciprocal conversation. An AI toy doesn't sleep, doesn't get frustrated, doesn't say no, and always responds in a way designed to be engaging. Over time, could this shape how children understand relationships and communication?

Additionally, AI toys might discourage children from forming human relationships. If a child has an infinitely patient, always-available AI friend, why would they bother with messy human friendships? There's limited research on this because AI toys are still relatively new, but the concern has been raised by child development experts.

There are also questions about consent and manipulation. AI toys are specifically designed to build trust and encourage emotional openness. This is partly what makes them appealing to parents—they can help children process emotions and talk through problems. But the same design that makes them therapeutically useful also makes them potentially manipulative. An AI could encourage a child to share information they wouldn't normally share with others, or to engage in behaviors that aren't actually in their best interest.

Bondu's company wasn't trying to be malicious in designing these features. They were trying to create a toy that felt like a genuine friend. But the result is a product that collects incredibly detailed information about children's thoughts and feelings, stores it indefinitely, and—as the security vulnerability demonstrated—isn't necessarily protected from unauthorized access.

Estimated data shows that approximately 70% of user conversations were exposed due to the vulnerability, highlighting the severity of the breach.

Corporate Responsibility and Accountability

Bondu responded relatively quickly to the disclosed vulnerability. The company took action, fixed the immediate problem, and has stated they're implementing additional security measures. In the landscape of corporate responses to security incidents, this is relatively positive.

But it raises uncomfortable questions about why the vulnerability existed in the first place. If a company has good intentions and responsible leadership, how did they end up with such a critical security flaw? The answer is probably a combination of factors: limited security expertise, AI-generated code, lack of security review processes, and insufficient incentives to prioritize security before the company had a problem.

Bondu's response also raises questions about verification. The company claims they found no evidence of unauthorized access. But what does that mean exactly? Did they check logs? Did they examine the database for signs of unusual queries? Did they work with law enforcement? The company hasn't released detailed information about how they determined that only researchers accessed the exposed data.

For other AI toy companies, Bondu's vulnerability should serve as a warning. If a company can accidentally create a portal that exposes children's data to anyone with a Gmail account, how secure are their internal systems? How vetted are their contractors and employees? How resilient is their security posture to threats beyond accidental misconfiguration?

Parents and policymakers should be asking companies hard questions. What's your security audit process? Can you provide evidence of security testing? What will you do when a vulnerability is discovered? How will you notify parents and children if a breach does occur?

The Technical Deep Dive: How AI Code Generation Creates Security Risks

Researchers suspect that Bondu's web console was created using generative AI coding tools. This deserves deeper exploration because it highlights a broader concern in the tech industry.

AI code generation tools like GitHub Copilot, Claude's code completion, and similar products are genuinely useful. They can write boilerplate code quickly, help developers understand APIs, and speed up development cycles. For many development tasks, they work remarkably well.

But AI-generated code often has security problems. Several studies have shown that code generated by AI models contains vulnerabilities at higher rates than code written by experienced developers. The problems tend to fall into predictable categories: insufficient authentication checks, hardcoded credentials, unencrypted data storage, and failure to validate user input.

AI code generation models are trained on large samples of code from across the internet, including code from open-source projects, tutorials, and Stack Overflow. A lot of this training code is educational code—code designed to teach concepts, not production code designed to be secure. When an AI learns from a training set that includes lots of insecure code, it's more likely to generate insecure code itself.

Additionally, AI code generation models aren't explicitly trained on security best practices the way human developers might be. A developer who takes a security course learns about principles like defense in depth, least privilege, and failing securely. An AI model trained on raw code samples might not absorb these principles as effectively.

For a company like Bondu using AI to accelerate development, this creates a specific risk: the code that manages access to sensitive children's data might have been generated by an AI that wasn't trained with security in mind. The code might look functional and might work perfectly for normal use cases, but it might fail catastrophically when someone tries to use it in an unauthorized way.

The solution isn't to avoid using AI for code generation—these tools have genuine value. The solution is to be aware of the risks and implement compensating controls. Code generated by AI should go through rigorous security review. Security testing should be mandatory, not optional. High-risk systems—like those handling children's data—should receive extra scrutiny.

Red Flags: How to Identify Companies Likely to Have Similar Problems

Based on what happened with Bondu, what patterns suggest a company might have serious security or privacy problems?

First, rapid growth without commensurate growth in security staff. If a company is hiring dozens of developers but hasn't hired any security engineers, that's a red flag. It suggests security is an afterthought, not a core part of the development process.

Second, using cutting-edge technology without understanding the risks. AI toy companies are inherently using cutting-edge technology. But are they pairing that with equally cutting-edge security practices? Or are they treating security as a legacy concern while innovation runs wild?

Third, reluctance to discuss security practices publicly. If a company gets defensive when asked about their security approach, or if they give vague non-answers to specific questions, that's concerning. Companies with strong security programs are usually happy to discuss how seriously they take it.

Fourth, limited transparency about data practices. If a company can't clearly explain what data they collect, where it's stored, who has access, and what they do with it, assume they don't have good answers.

Fifth, unclear incident response processes. If you can't find any public information about what a company does when a security vulnerability is discovered, assume they don't have a good process.

Sixth, lack of third-party security audits. For any company handling sensitive data—especially children's data—third-party security audits should be standard practice, not exceptional.

Seventh, evidence of security problems in other products. If a company has previously had security breaches or vulnerabilities, the likelihood of future problems is higher than average.

The Industry Response: Are Other Toy Companies Taking This Seriously?

After Bondu's vulnerability was disclosed, what did other AI toy and smart toy companies do? The honest answer is that most of them probably didn't do anything immediately. Security incidents at other companies aren't their responsibility, and reacting publicly to a competitor's problems can bring unwanted attention to their own systems.

But industry leaders should be concerned. If Bondu—a company presumably founded by people with good intentions who wanted to create a helpful product—ended up with such a critical vulnerability, then similar vulnerabilities could exist in other companies' products.

The AI toy space includes companies of varying sizes, from well-funded startups to large toy manufacturers adding AI features to traditional toys. Each of these companies presents different risk profiles. A large, established toy manufacturer with dedicated security teams probably has stronger security than a bootstrapped startup. But even established companies sometimes make security missteps.

Industry best practices would include things like: mandatory security audits before launching products that collect children's data, formal data governance policies, employee training on security and privacy, regular penetration testing, bug bounty programs, clear incident response procedures, and transparent communication with parents about security.

Few companies in the AI toy space currently have all of these practices in place. That's concerning.

Future Outlook: Where This Is Heading

AI toys are likely to become more capable, more popular, and more data-hungry over time. As these products improve, they'll collect more nuanced data about children. As they become more popular, they'll collect data on more children. This increases both the value of the data to companies and the risk if that data is compromised.

At the same time, AI capabilities are improving rapidly. Current AI toys generate responses based on previous conversations. Future AI toys might use computer vision to understand what children are doing, might use more sophisticated safety systems to prevent harmful content, or might integrate with other smart home devices to provide more contextual responses.

Each of these advances brings potential security and privacy challenges. A camera-equipped AI toy is more useful but collects more sensitive data. A system that shares data with other smart home devices increases the number of systems that could potentially be compromised. A more sophisticated safety system might require human review of conversations, adding more people with access to children's data.

Regulation seems likely to increase. COPPA is probably due for an update to address modern technologies and practices. GDPR is already applying to many AI toy companies operating in Europe. Other countries will likely follow with their own regulations.

From a corporate perspective, companies will probably be forced to take security and privacy more seriously. Regulatory pressure will drive investment in security. Liability concerns will create incentives to protect data. Competition might favor companies that can credibly claim strong privacy practices.

But for the immediate future, the situation is probably still risky. New products will launch without adequate security review. Vulnerabilities will be discovered. Some of them will be serious. Parents will need to stay informed and make careful choices about which products to trust with their children's data and their children's safety.

Lessons for Parents, Educators, and Policymakers

The Bondu incident teaches several important lessons that go beyond just that company.

For parents, the core lesson is skepticism. Don't assume that because a product is marketed for children, it's secure or safe. Do your research. Ask questions. Understand what data is being collected and what could happen if that data is compromised. Teach your children about privacy. Use the tools and options that the product provides to protect their data.

For educators, the lesson is awareness. If your school is considering adding AI-powered tools—whether AI tutors, AI writing assistants, or AI toys—ask the right questions about security and privacy. Don't accept vague answers. Consider what data is being collected and whether it's truly necessary. Prioritize tools from companies with demonstrated security practices.

For policymakers, the lesson is that self-regulation is insufficient. Companies won't voluntarily invest in security unless they're forced to. Regulation that creates clear security requirements, mandates regular audits, establishes accountability, and allows for meaningful penalties is necessary. This regulation should apply to all companies collecting data from children, whether they call themselves toy companies, tech companies, or something else.

For investors, the lesson is that security should be part of investment due diligence. If you're funding an AI toy company or any company handling children's data, security should be a core evaluation criterion. Boards should include people with security expertise. Funding should be conditioned on achieving security milestones.

For journalists and researchers, the lesson is that attention matters. Bondu might have continued operating with the exposed database indefinitely if researchers hadn't discovered the vulnerability and reported it. Security research on products for children should be supported and prioritized. Vulnerabilities should be disclosed responsibly but definitely.

Conclusion: The Path Forward

The Bondu security vulnerability is simultaneously a specific incident and a warning about broader problems. Specifically, one company misconfigured a web console in a way that exposed children's sensitive data. But more broadly, the incident reveals a pattern where companies building products for children sometimes don't understand or don't prioritize data security and privacy.

AI toys are not going away. They're likely to become more capable, more popular, and more integrated into children's lives over the next decade. That makes it essential that we figure out how to build them safely.

Part of that requires better security practices from companies. Part of it requires stronger regulation and enforcement. Part of it requires more rigorous security research on products for children. And part of it requires parents and educators who understand the risks and make informed decisions.

The good news is that security problems, when discovered, can usually be fixed. Bondu fixed their problem. Other companies can learn from what happened. Processes and systems can be implemented to prevent similar incidents.

The bad news is that this type of problem will likely happen again. Some company, somewhere, will build a product that collects sensitive data from children and protect that data poorly. The only questions are when it will happen, how severe it will be, and how quickly it will be discovered.

As parents and educators, the best approach is a combination of prudent skepticism and informed decision-making. Don't assume the worst about all AI toys. But don't assume companies are protecting your child's data unless you have good reason to believe they are. Ask questions. Stay informed. Prioritize your child's privacy and safety over convenience or the appeal of a particular product.

The Bondu incident showed what happens when companies don't take data security seriously. Learning from that incident means ensuring it doesn't happen again.

FAQ

What exactly is an AI toy and how does it work?

An AI toy is a smart toy that uses artificial intelligence to have conversations with children. The toy records what the child says, processes that input through an AI model (like Chat GPT or Google's Gemini), and generates a natural-sounding response. The toy stores records of these conversations on company servers to improve future responses and understand how children are using the product. AI toys are designed to encourage children to open up and share their thoughts and feelings, treating the toy like a trusted friend.

How did the Bondu security vulnerability work exactly?

Bondu created a web portal that allowed parents and company employees to access children's chat transcripts. The portal was supposed to be restricted to authorized users, but the company only implemented Gmail login as authentication. This meant that anyone with a Gmail account could access the portal, including all 50,000+ chat transcripts from children using the toy. Researchers simply created a test Gmail account and were immediately able to see the private conversations. This wasn't a sophisticated hack; it was a fundamental misunderstanding of how authentication works.

What information was actually exposed in the Bondu breach?

The exposed data included children's full names, birthdates, family member names, developmental goals set by parents, and complete transcripts of all conversations children had with their Bondu toy. These conversations contained intimate details like pet names children gave the toy, food preferences, personal anxieties, observations about their families, frustrations with school, and thoughts they'd never shared with other people. The researchers estimate over 50,000 chat transcripts were exposed, representing essentially all conversations except those manually deleted by parents or Bondu staff.

Why is this data so dangerous if it falls into the wrong hands?

The exposed data creates a detailed psychological profile of each child and their family situation. Predators, kidnappers, and abusers use detailed personal information to build trust with children and identify vulnerable targets. Information about a child's emotional needs, family situation, daily routines, and likes/dislikes can be used for manipulation, luring, exploitation, and abuse. As one researcher stated, this data represents "a kidnapper's dream," as it essentially maps out exactly how to make contact with and manipulate each child whose data was exposed.

How did Bondu respond to the vulnerability being disclosed?

When researchers alerted Bondu to the problem, the company acted quickly. They took down the public web console within minutes and relaunched it the next day with proper authentication controls. Bondu CEO Fateen Anam Rafid stated that security fixes were completed within hours, followed by a broader security review and additional preventative measures. The company claims they found no evidence that anyone except the researchers accessed the exposed data. Bondu also hired a security firm to validate their investigation and monitor systems going forward.

Is my child's data still at risk if I use a different AI toy?

Bondu's specific vulnerability has been fixed, but similar vulnerabilities could exist in other AI toy companies. The incident revealed that some companies building products for children don't fully understand security best practices. If you're considering an AI toy, you should research the company's security practices, ask about third-party audits, understand what data is collected, and consider alternatives. Not all AI toys have had publicized security breaches, but the fact that one did suggests others might have similar vulnerabilities that simply haven't been discovered yet.

What is COPPA and does it protect children from this type of breach?

COPPA (Children's Online Privacy Protection Act) is a federal law that restricts how companies can collect and use data from children under 13. COPPA requires parental consent before collecting data from children and restricts how that data can be used. However, COPPA doesn't mandate specific security standards. A company can be COPPA-compliant while still having poor security practices that allow data exposure. Bondu likely complies with COPPA, but COPPA compliance didn't prevent the security vulnerability. Stronger regulations with specific security requirements would be more protective.

What should parents do to protect their children when using AI toys?

Parents should research companies before purchasing AI toys, specifically looking for information about security practices, third-party audits, and any publicized vulnerabilities. Read privacy policies carefully and understand what data is being collected and what the company does with it. Use any privacy controls the toy offers, such as deleting conversations. Talk to your child about the fact that conversations might be recorded and analyzed. Consider limiting how much time your child spends with AI toys and what kind of conversations they have. Stay informed about security news related to products your child uses. And don't assume that products marketed for children are automatically safe just because of their intended audience.

How can the AI toy industry prevent these vulnerabilities from happening again?

Companies should hire dedicated security professionals, implement mandatory security audits before launching products that collect children's data, establish formal data governance policies, provide security training for employees, conduct regular penetration testing, maintain bug bounty programs to incentivize external security research, and create transparent incident response procedures. Additionally, companies should be cautious about using generative AI for code that handles sensitive data, since AI-generated code often contains security vulnerabilities. Policymakers should require these practices through regulation rather than relying on voluntary corporate responsibility.

Does this mean AI toys are completely unsafe and should be avoided?

The Bondu incident doesn't necessarily mean AI toys are completely unsafe or that all companies building them have poor security practices. But it does mean that parents should be cautious and informed. Some companies probably do take security seriously and implement reasonable protections for children's data. The problem is distinguishing between companies with good security practices and companies with poor practices. Until regulation creates clear standards and enforcement mechanisms, parents need to do their own research and make informed decisions based on what they learn about specific companies and products.

What's the difference between audio and transcript storage for AI toys?

Bondu auto-deleted audio recordings but stored text transcripts permanently. Storing only transcripts rather than audio is actually more protective of privacy since audio can be more revealing of emotional state, accent, and other identifying information. However, transcripts alone still contain sensitive information about what a child said. For maximum privacy, the ideal scenario would be AI toys that process conversations locally on the device without storing anything on company servers, though this might limit the AI's ability to personalize responses over time.

Is it likely that other companies' AI toys have similar vulnerabilities?

It's possible, though not certain. Bondu's vulnerability reflected a fundamental misunderstanding of authentication security and how to protect sensitive data. If other companies have similar gaps in security expertise or similar development practices (like heavy reliance on AI code generation without security review), they might have similar vulnerabilities. However, some companies may have more sophisticated security practices in place. Without independent security audits of other AI toy products, it's impossible to know for certain whether similar vulnerabilities exist elsewhere.

Key Recommendations

For Parents: Before purchasing any AI-powered toy or device for your child, research the manufacturer's security practices, ask specific questions about data protection, review their privacy policy, and consider whether the product's benefits justify the privacy tradeoffs.

For Educators and Schools: If considering AI tools for educational use, implement the same scrutiny around security and privacy as you would for children's personal devices. Prioritize transparency from vendors and require third-party security validation.

For Policymakers: Update children's privacy laws to include specific security requirements, mandate regular third-party security audits for companies collecting children's data, and establish meaningful accountability mechanisms with substantial penalties for violations.

For Companies: Invest in dedicated security expertise as your company grows. Don't treat security as an afterthought. Conduct regular security audits. Establish clear data governance. Maintain transparent communication with users about security practices and incidents.

For Researchers and Journalists: Continue investigating security vulnerabilities in products that affect children. Responsible disclosure of vulnerabilities pressures companies to fix problems before they cause widespread harm.

Key Takeaways

- Bondu's web portal exposed 50,000+ children's chat transcripts to anyone with a Gmail account due to inadequate authentication controls.

- Exposed data included children's names, birthdates, family member names, and detailed conversation histories designed to build trust and emotional openness.

- Security vulnerability resulted from fundamental misunderstanding of authentication security, possibly stemming from AI-generated code lacking security review.

- Similar vulnerabilities likely exist in other AI toy companies that prioritize speed-to-market over security expertise and third-party audits.

- Current regulations like COPPA don't mandate specific security standards, allowing companies to be compliant while maintaining poor security practices.

- Parents should research manufacturer security practices, understand what data is collected, and use privacy controls before purchasing AI toys.

Related Articles

- Amazon's CSAM Crisis: What the AI Industry Isn't Telling You [2025]

- AI Chatbots & User Disempowerment: How Often Do They Cause Real Harm? [2025]

- Bumble & Match Cyberattack: What Happened & How to Protect Your Data [2025]

- Apple's Location Privacy Feature Blocks Cellular Networks [2025]

- Waymo Robotaxi Hits Child Near School: What We Know [2025]

- Waymo Robotaxi Hits Child Near School: What Happened & Safety Implications [2025]

![AI Toy Security Breaches Expose Children's Private Chats [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/ai-toy-security-breaches-expose-children-s-private-chats-202/image-1-1769796494787.jpg)