Blue Origin Pauses Space Tourism for NASA Lunar Lander Development: What This Means for Commercial Space

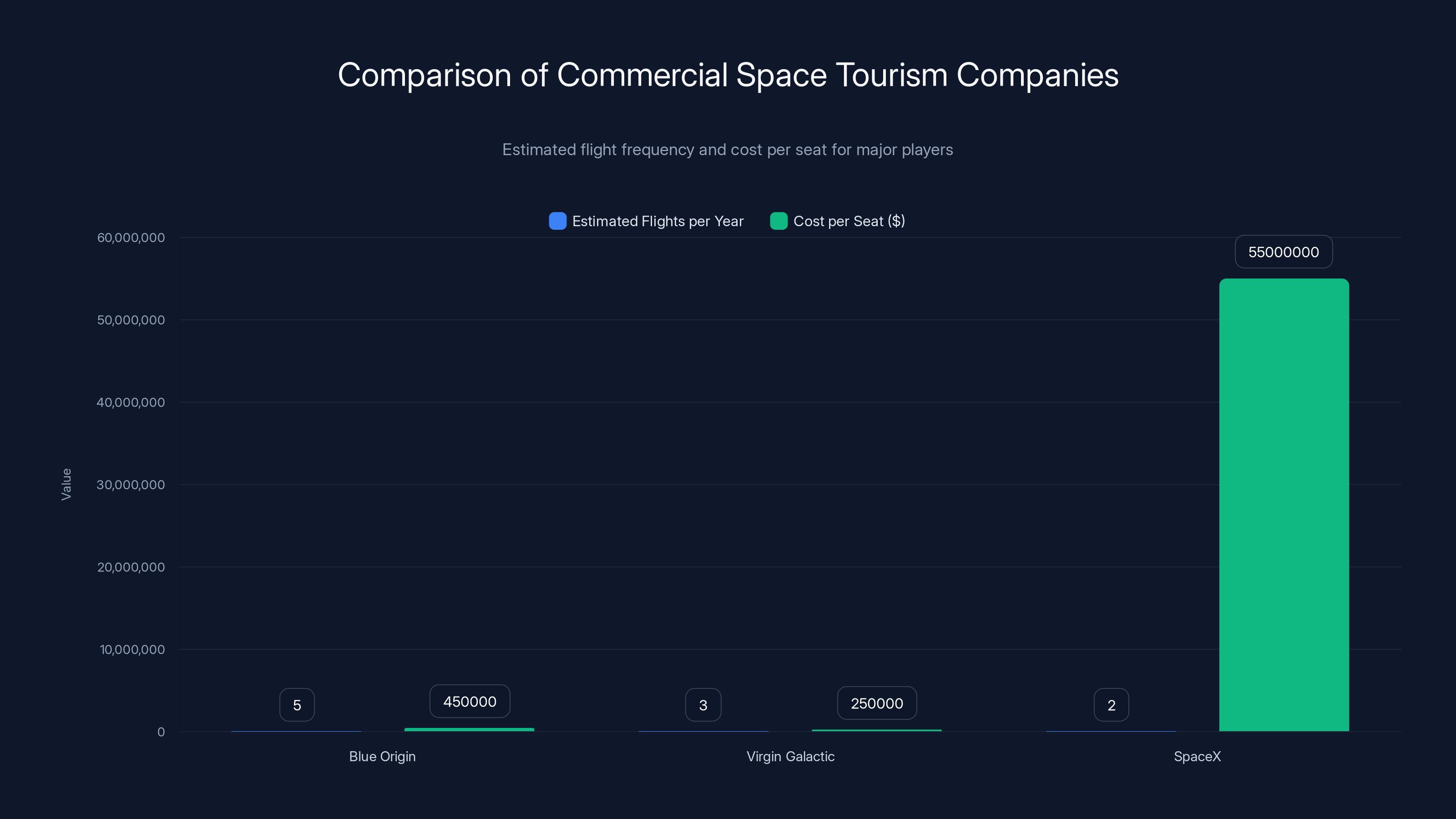

Last week, Blue Origin made a decision that surprised exactly nobody in the space industry but disappointed plenty of space enthusiasts. The company announced it's putting its profitable New Shepard suborbital tourism program on ice for at least two years. No more celebrity joy rides to the edge of space. No more Instagram-worthy zero-gravity moments. No more of that adrenaline rush that made William Shatner cry and convinced thousands of wealthy people to drop $450,000 per seat.

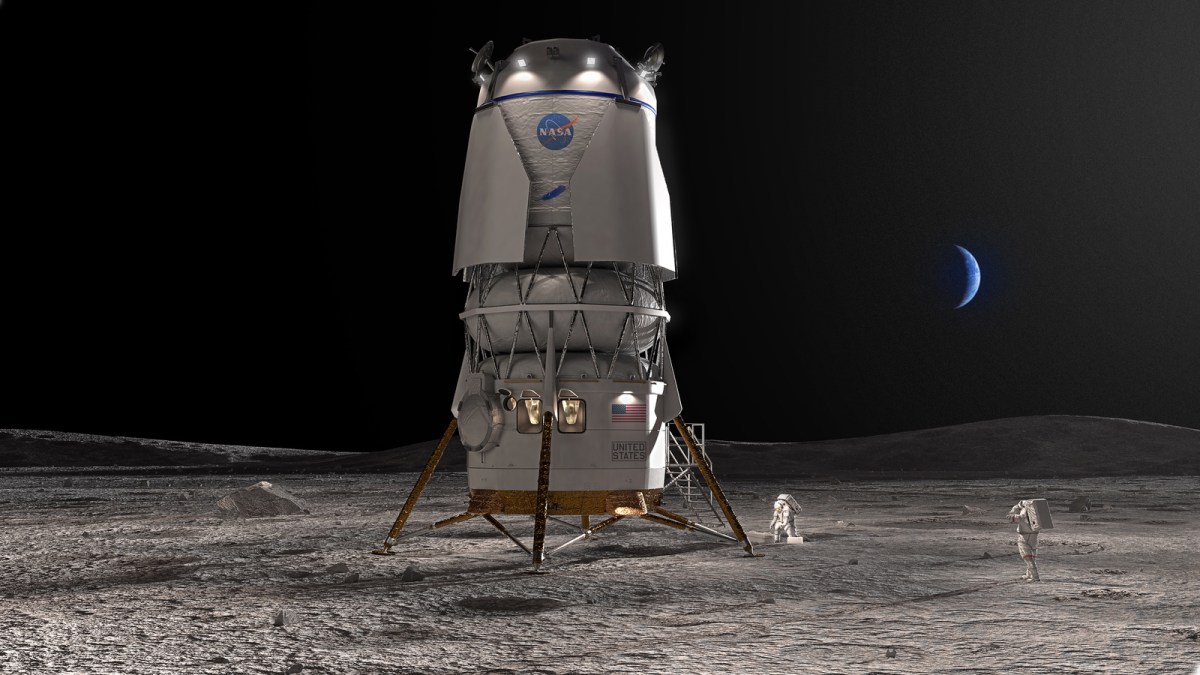

Instead, Blue Origin is redirecting its resources, engineering talent, and manufacturing capacity toward something far more ambitious: building lunar landers for NASA's Artemis program. Specifically, the company will develop human landing systems for Artemis III and Artemis V missions, a contract that represents billions of dollars in government funding and positions Blue Origin as a critical player in humanity's return to the moon.

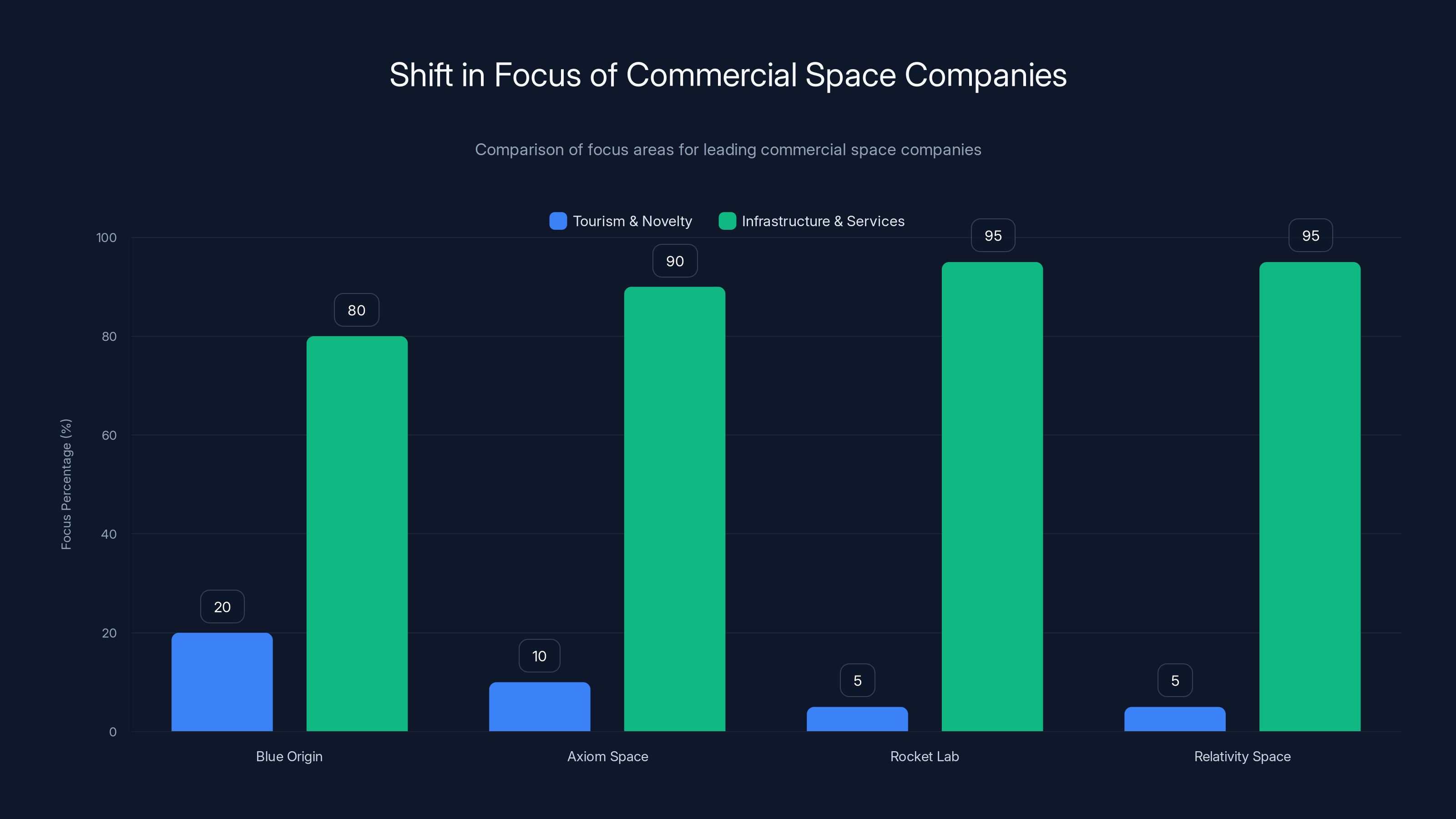

This pivot tells us something important about where commercial space is heading. Tourism was always the training wheels. The real money, the real mission, and the real significance lie in becoming an infrastructure provider for government space agencies. Blue Origin is making the calculated bet that a pause in tourist revenue now will pay dividends later when it establishes itself as one of only two companies capable of landing humans on the lunar surface.

But there's more to this story than just corporate strategy. The decision reflects genuine technical challenges, shifting political priorities, and the messy reality of how government contracts work. Let's dig into what's actually happening, why it matters, and what comes next.

TL; DR

- Blue Origin is pausing New Shepard flights for at least two years to focus entirely on developing human lunar landing systems for NASA's Artemis III and Artemis V missions

- Only two companies are building lunar landers for Artemis: Blue Origin and SpaceX, giving Blue Origin enormous leverage in the commercial space economy

- The Artemis program is accelerating due to political pressure from the Trump administration, which wants the first crewed moon landing before the end of the presidential term

- New Shepard is profitable but secondary compared to the multi-billion dollar lunar lander contracts that represent the company's true strategic priority

- This pause signals a maturation of commercial space: tourism was the headline, but infrastructure contracts are the foundation of a sustainable space industry

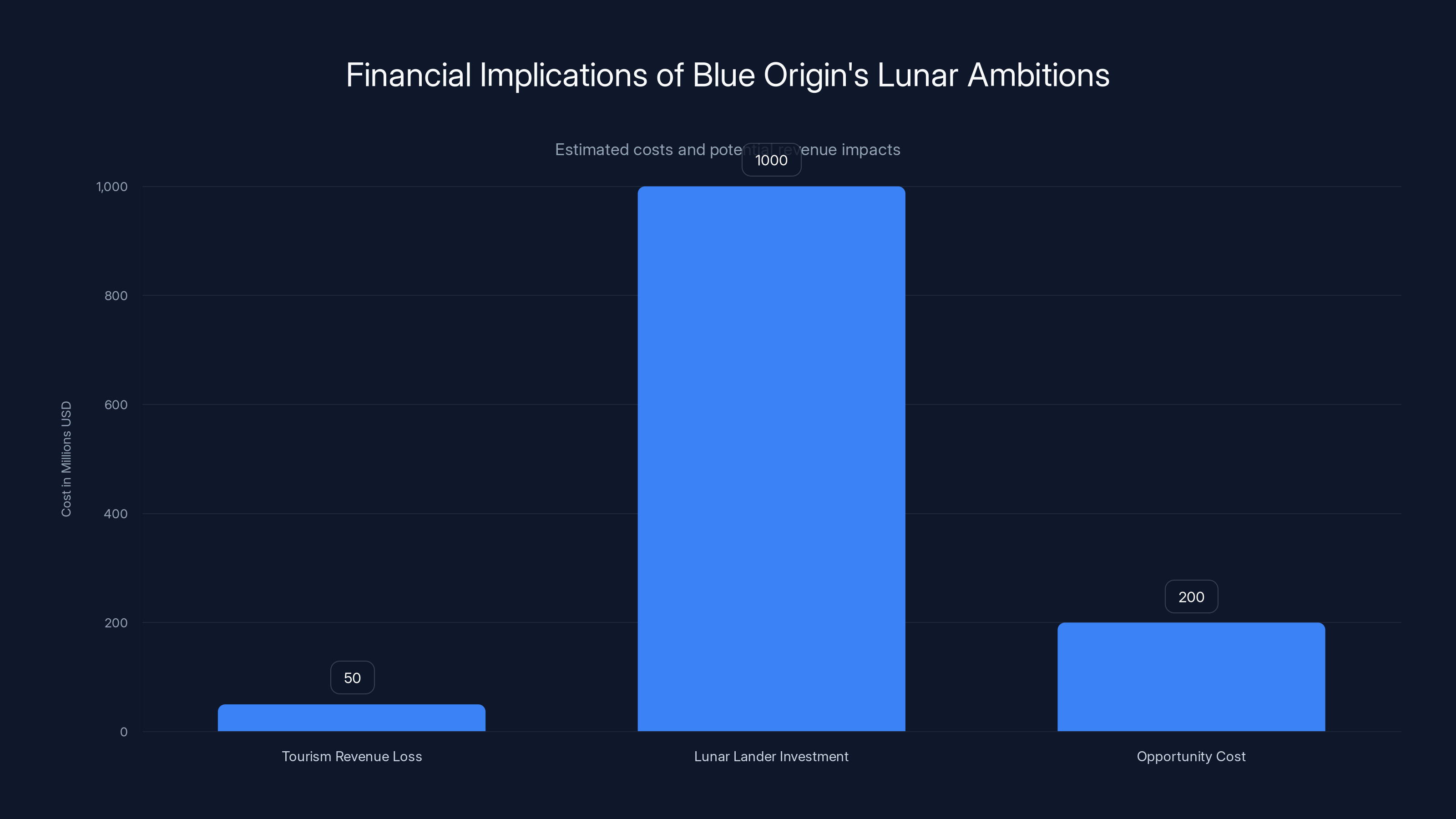

Blue Origin faces significant financial implications with a

The New Shepard Story: From Tourism Darling to Shelved Program

When Jeff Bezos climbed aboard Blue Origin's New Shepard rocket on July 20, 2021, it felt like the beginning of something transformative. The billionaire entrepreneur was launching himself into suborbital space aboard his own company's vehicle, experiencing weightlessness for a few minutes, and then coming back home. The image was almost poetic: a self-made billionaire literally reaching for the stars.

That flight was more than symbolic. It validated the entire concept of commercial space tourism. If Blue Origin could safely fly paying customers to space, then the infrastructure existed. The technology worked. The market was real.

New Shepard became the vehicle that proved suborbital space tourism was viable. The rocket-powered capsule launches straight up, crosses the Kármán line at 100 kilometers altitude (the accepted boundary of space), gives passengers a few minutes of weightlessness to float around and press their faces against the windows, and then both vehicles descend under parachute back to Earth. The entire experience lasts about 11 minutes from launch to landing.

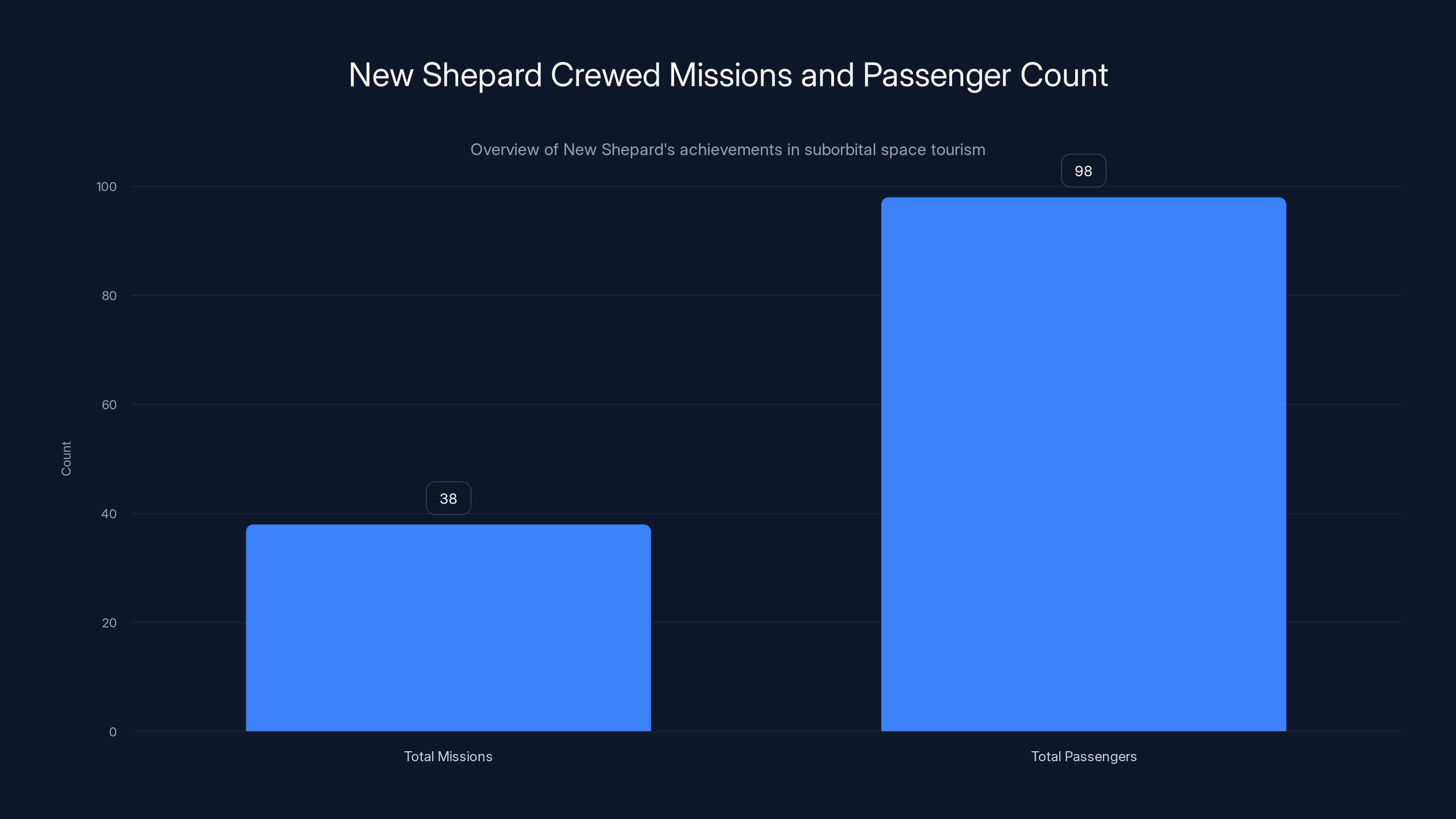

The numbers seemed impressive on paper. New Shepard flew 38 successful crewed missions and carried 98 passengers to space. That's a remarkable safety record for a new human spaceflight system. Notable passengers included Katy Perry, William Shatner, and numerous entrepreneurs and celebrities willing to spend nearly half a million dollars for a few minutes in space.

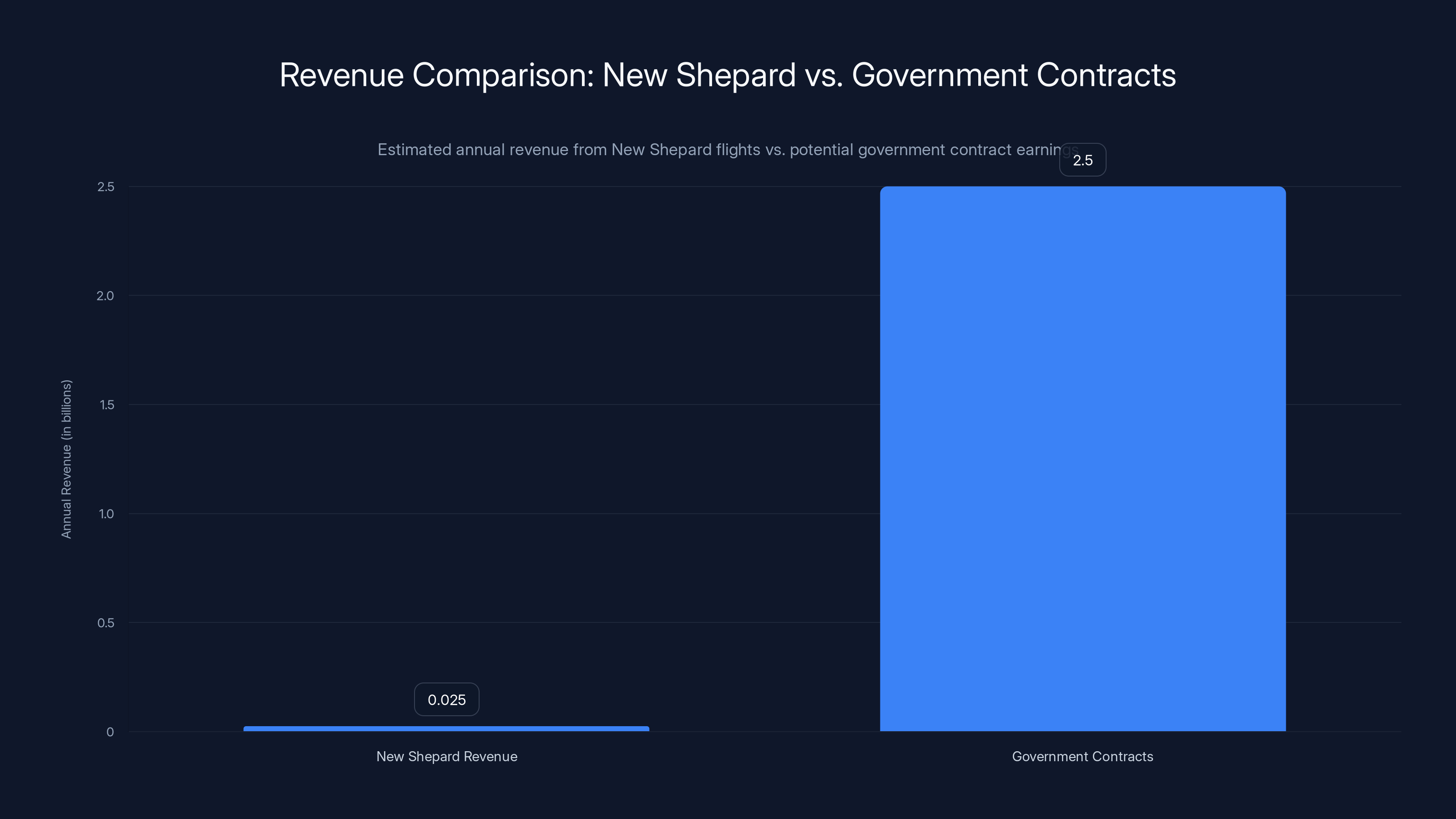

But here's the thing: New Shepard was always a prestige project more than a money-maker. Yes, at $450,000 per ticket, the revenue looked substantial. But the company's long-term strategy was never about filling seats on suborbital joy rides. Blue Origin's real ambition was to become the provider of heavy-lift launch services and deep-space infrastructure. Tourism was the proof of concept. Lunar landers are the business.

When Blue Origin announced the New Shepard pause, many observers saw it coming. The company had been gradually reducing flight frequency anyway. The gap between missions had been growing. Resources were being reallocated. Engineering teams were being reassigned. This announcement just made the strategy explicit.

Why Blue Origin Made This Choice: The Artemis Imperative

The decision to pause New Shepard didn't happen in a vacuum. It happened because of NASA's Artemis program, which is now operating under unprecedented political pressure to deliver a crewed lunar landing on an accelerated timeline.

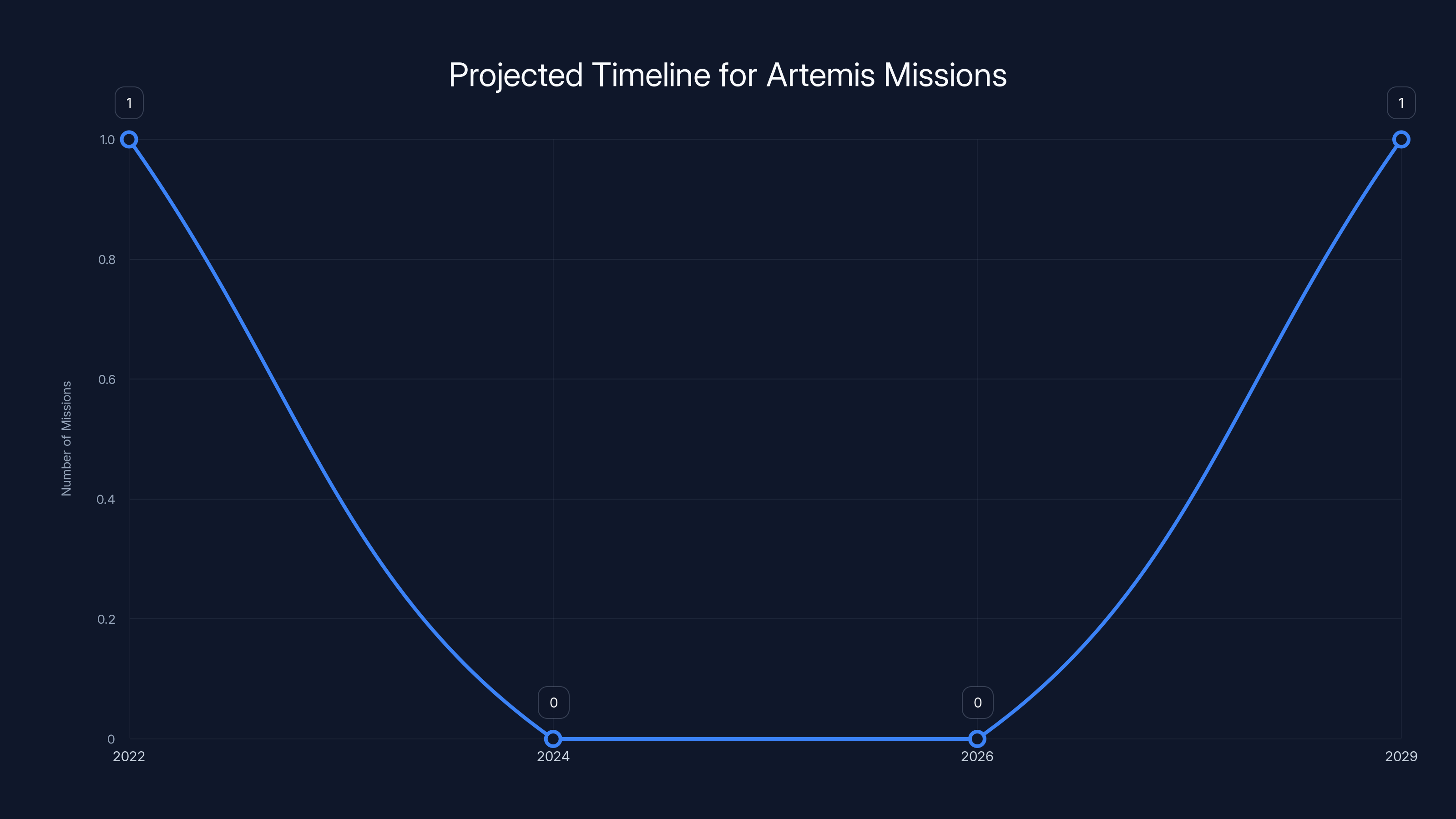

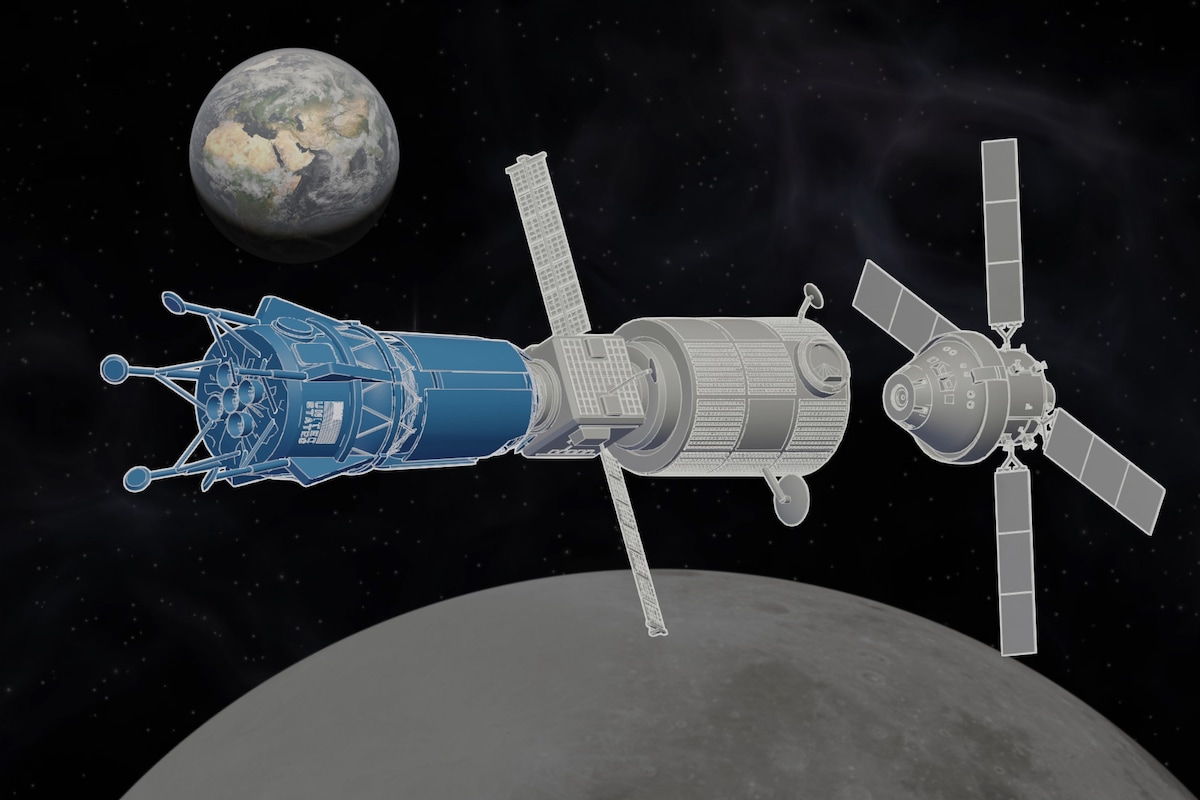

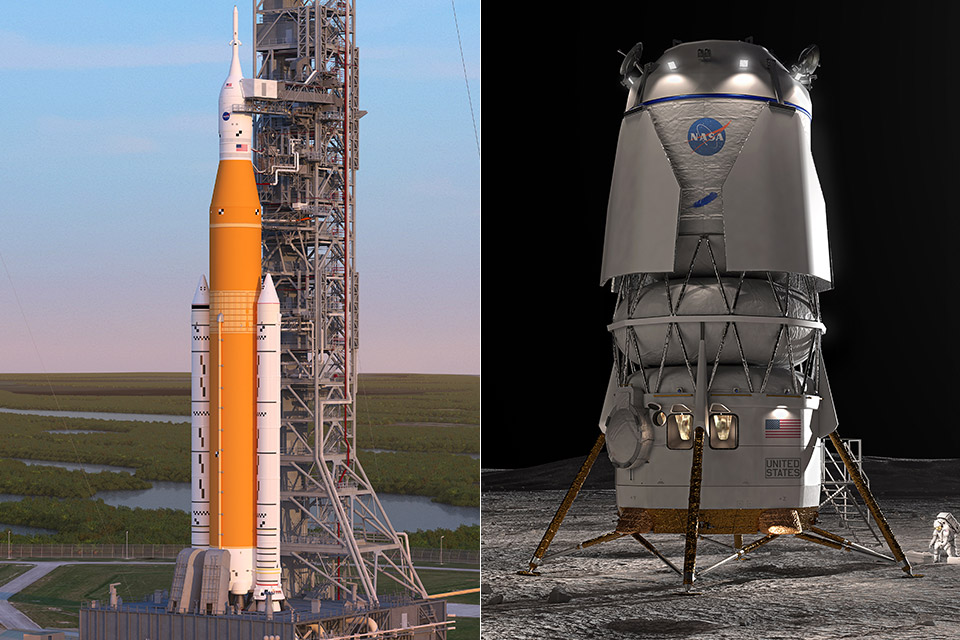

Artemis is NASA's plan to return humans to the moon for the first time since 1972. The program involves multiple components: the Space Launch System (SLS) heavy-lift rocket, the Orion spacecraft for crew transportation, and lunar landers to get astronauts from orbit down to the surface. Artemis I flew in late 2022 as an uncrewed test mission. Artemis II, also uncrewed, had been scheduled for 2024 but faced delays. Artemis III, the first crewed lunar landing mission, was originally targeted for 2026 but kept slipping.

Then the Trump administration took office, and suddenly the timeline became a political issue. The administration wants the first crewed moon landing to happen before the end of the presidential term in January 2029. That's less than four years away. It's an absurdly aggressive timeline given how complex lunar missions are, but it's the timeline that matters politically.

NASA responded by redesigning its Artemis strategy. Instead of relying primarily on SpaceX's Starship HLS (Human Landing System), the agency asked Blue Origin to develop an alternative lunar lander for Artemis III. This was a strategic move to de-risk the program. If SpaceX encountered delays, NASA would have a backup option. If Blue Origin's system was ready first, NASA could use it immediately.

For Blue Origin, this represented a massive contract opportunity. The company was handed a blank check (well, a several-billion-dollar contract) to design a lunar lander that could work within the existing Artemis architecture. But there was a catch: the timeline was tight, and Blue Origin couldn't afford to spread its engineering resources thin.

Enter the New Shepard pause. By suspending the tourism program, Blue Origin freed up critical resources. Engineers who would have been maintaining New Shepard, preparing capsules for flight, and managing ground operations could instead focus on lunar lander development. Manufacturing facilities could be retooled for HLS hardware instead of tourist vehicles. Management attention could focus entirely on the most important contract in the company's history.

It was a straightforward calculation: the revenue from New Shepard over two years might total $200-400 million, assuming they flew frequently. The contract for developing and potentially flying lunar landers could be worth billions. The choice was mathematically obvious.

While New Shepard generates

The Lunar Lander Competition: Blue Origin vs. SpaceX

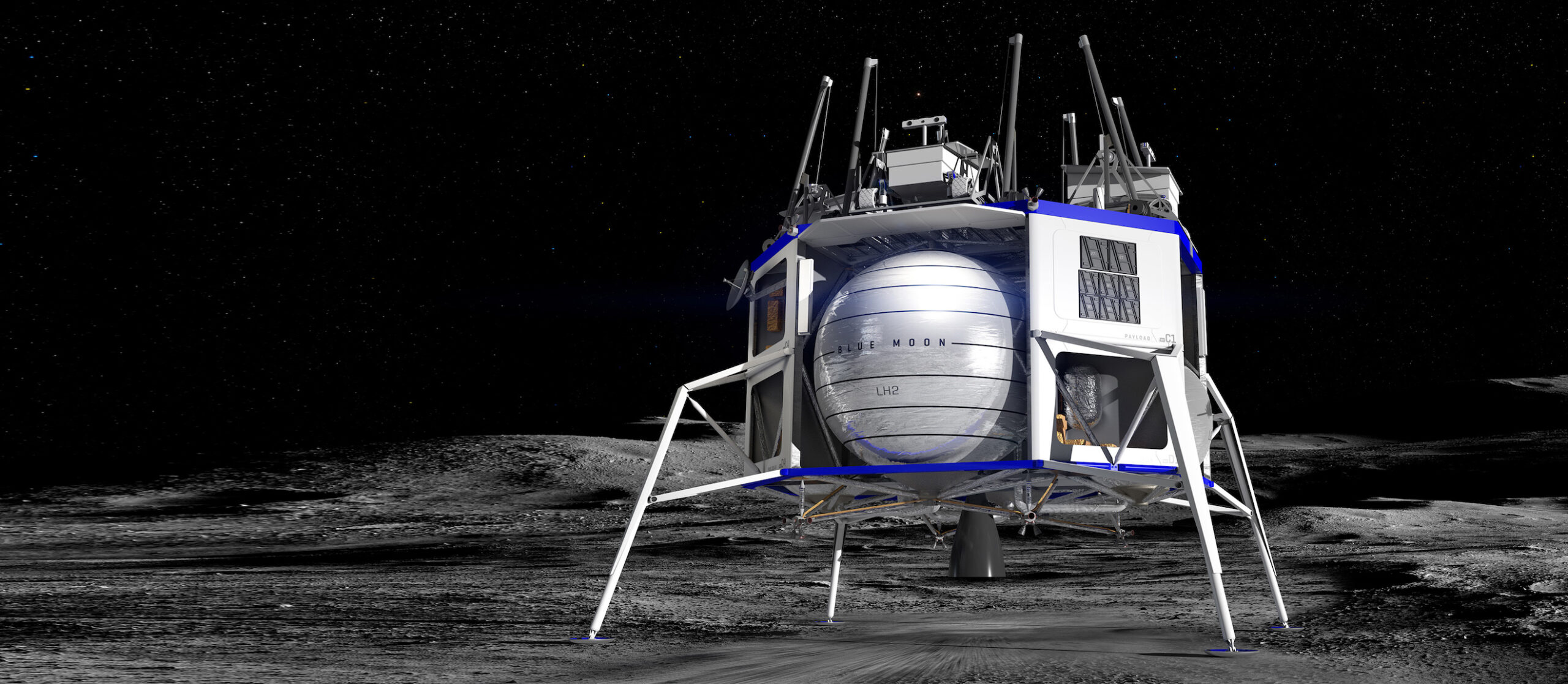

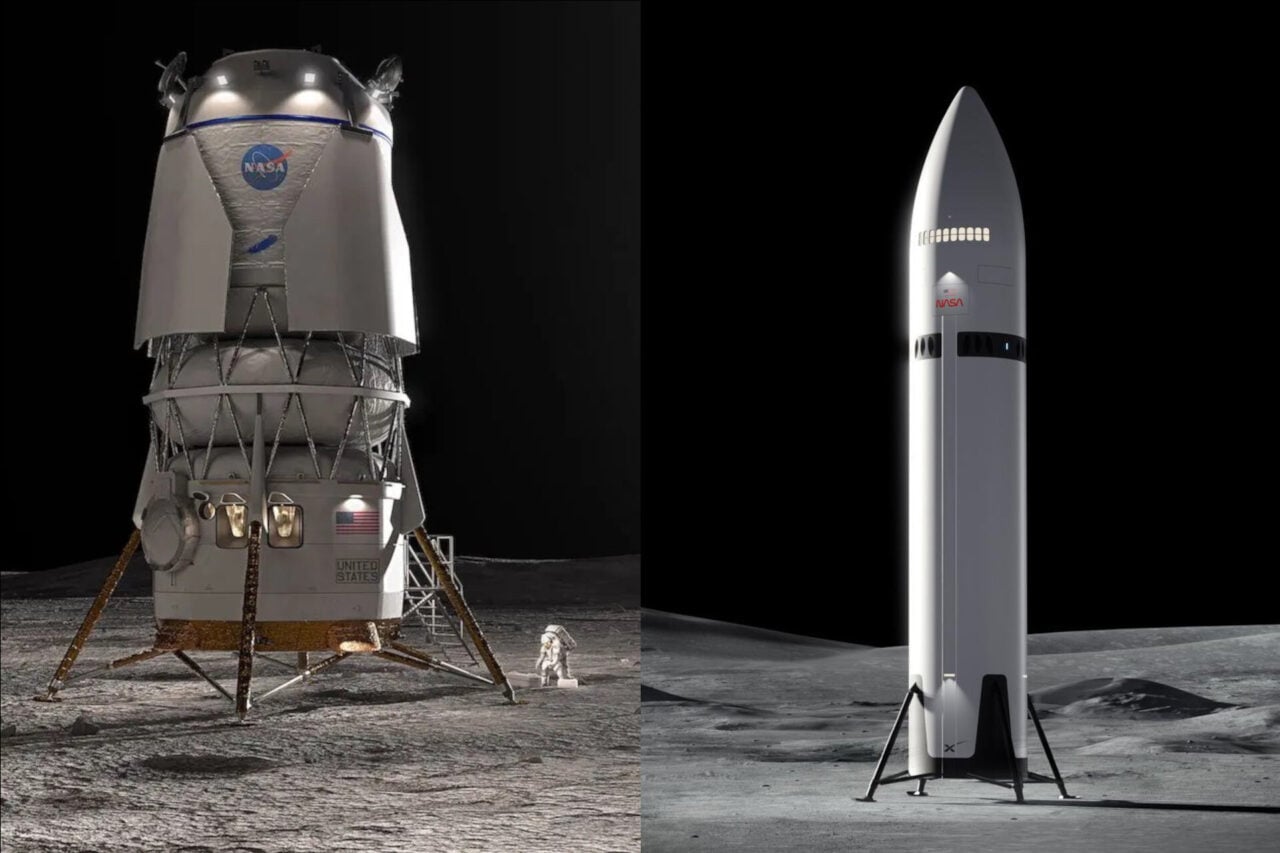

Understanding why Blue Origin paused tourism requires understanding the competitive dynamic in lunar lander development. Essentially, there are two horses in this race: Blue Origin and SpaceX.

SpaceX started with a significant advantage. The company had already been working on Starship HLS as part of NASA's early Artemis planning. Starship is SpaceX's fully reusable super-heavy-lift rocket, designed to land vertically on the moon with a crew cabin adapted for lunar operations. In theory, the same vehicle that launches from Earth can land on the moon and return. It's an elegant, if extraordinarily complex, engineering solution.

But Starship kept failing. The integrated flight tests suffered explosive failures as SpaceX pushed to develop the vehicle at a breakneck pace. Each failure set back the HLS development timeline. NASA watched these failures with concern. If SpaceX couldn't land Starship reliably on Earth, how confident could NASA be that it would land safely on the moon?

That's why NASA turned to Blue Origin. The agency essentially said: "We like SpaceX's vision, but we can't bet the entire Artemis program on one company's experimental rocket. We need a backup." Blue Origin got the contract for an alternative HLS for Artemis III.

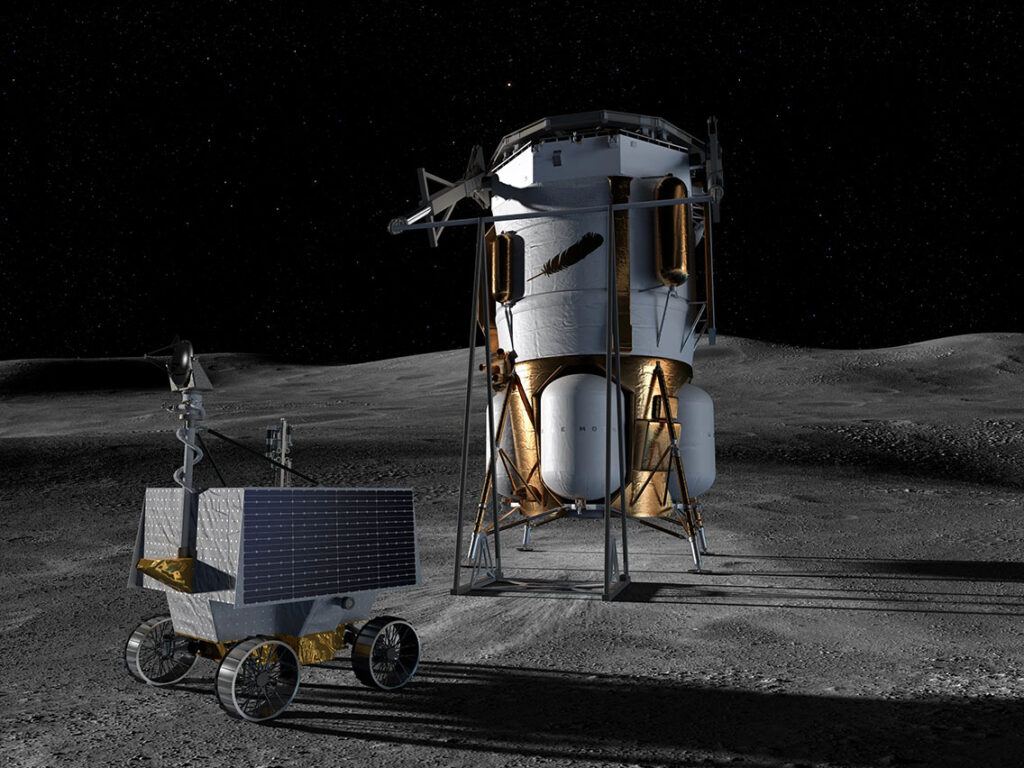

Blue Origin's approach is different from SpaceX's. The company is building a purpose-built lunar lander rather than adapting an existing rocket. It's a more conservative, incremental approach. Less ambitious than Starship, but potentially more reliable and on schedule.

The competition between these two companies will define commercial space for the next decade. SpaceX's advantage is that Starship, if it works, is radically more capable. It could land 100+ tons on the moon compared to Blue Origin's smaller capacity. But Blue Origin's advantage is reliability and schedule. The company is more likely to deliver on time.

From Blue Origin's perspective, pausing New Shepard is a statement of confidence. The company is betting that it can beat SpaceX to a successful lunar landing, or at least deliver a reliable backup system that NASA will want to use. That's worth far more than two years of tourism revenue.

Artemis III and Artemis V: The Lunar Missions That Matter

To understand the scope of Blue Origin's commitment, you need to understand what Artemis III and Artemis V actually involve.

Artemis III is the first crewed lunar landing mission of the program. It will fly two astronauts to the moon's South Pole region, where there's ice in permanently shadowed craters. The presence of water ice is scientifically important (it could support future lunar bases) and strategically important (it's a resource that could be extracted and used for rocket fuel or drinking water). The mission will land, conduct scientific operations for several days, and return to Earth.

Artemis V is a follow-up mission that will land additional astronauts. It will likely involve more extensive surface operations and may include deployment of equipment for a longer-term lunar presence.

For both missions, the lunar lander is critical. The lander has to:

- Depart lunar orbit with crew members and cargo, starting from the Gateway station (a planned orbital outpost around the moon)

- Descend safely to the lunar surface despite the lack of an atmosphere for parachute braking

- Support crew on the surface for days, providing power, life support, and radiation protection

- Ascend back to orbit to rendezvous with the Orion spacecraft

- Do all this reliably because failure is not an option when human lives are at stake

Blue Origin's lunar lander will need to meet all these requirements while integrating with NASA's broader Artemis architecture. That's not trivial. It requires engineering across multiple domains: propulsion, life support, thermal management, power systems, communications, guidance and control, and human factors.

The Artemis III mission is currently targeted for 2026, though that timeline has slipped before and could slip again. But politically, that's the goal. Artemis V would follow, probably 2027 or 2028. Blue Origin's engineers are working backward from these dates, designing systems that can be tested, validated, and flying within the required windows.

The pressure is immense. It's not like commercial space companies where you can delay a launch by a few months if something isn't ready. This is a government program with congressional oversight, presidential directives, and international prestige at stake. When NASA says "Artemis III in 2026," Blue Origin's engineers take that deadline seriously because missing it has political consequences that ripple through the entire space industry.

Pausing New Shepard is one of the most direct ways Blue Origin can signal to NASA: "We're serious about this. We're not distracted. We're putting our resources where our mouth is." It's a credibility move as much as an operational one.

The Economics of Tourism vs. Government Contracts

One question worth examining is whether pausing New Shepard actually makes economic sense. Doesn't Blue Origin need the revenue? Shouldn't they run both programs in parallel?

The answer hinges on understanding the actual economics of commercial space tourism at this stage of development.

New Shepard, on paper, looks profitable. At

But profitability is more nuanced. The costs of operating New Shepard are substantial:

- Engineering and maintenance: Keeping a space vehicle flight-ready requires continuous inspection, component replacement, and system checks. The costs are measured in millions per year.

- Ground infrastructure: Launch facilities, mission control, payload integration facilities, and safety systems require capital investment and ongoing expenses.

- Safety and reliability programs: Space is unforgiving. Any incident damages the entire program. Blue Origin invests heavily in redundancy and testing.

- Personnel: Flight directors, safety officers, engineers, technicians, and managers are all on payroll.

Conservative estimates suggest Blue Origin's annual operating costs for New Shepard exceeded

Meanwhile, the lunar lander contract is worth billions. We don't know the exact number because government contracts aren't always public, but industry estimates suggest NASA committed several billion dollars across multiple contractors. Even if Blue Origin captures just $2-3 billion of that, it's 100 times the annual New Shepard revenue.

Beyond the immediate revenue, there's a strategic consideration. Blue Origin's long-term vision is to become the default infrastructure provider for deep space operations. If the company can establish itself as the reliable builder of lunar landers, that credibility opens doors to Mars landers, orbital infrastructure, and deep space logistics. Tourism is a distraction from that vision.

Bezos himself didn't start Blue Origin to make money from ticket sales. He created the company to develop technologies for massive-scale rocket reusability and space infrastructure. New Shepard was a validation project, not the end goal. The lunar lander contract aligns with the company's actual mission.

There's also a psychological element. For a company that competes for government contracts, every resource counts. NASA wants to fund contractors who are completely committed to their projects. If Blue Origin were still running New Shepard flights, NASA's review teams might ask: "Are these engineers spending their time on my lunar lander, or are they managing tourist operations?" By pausing tourism, Blue Origin eliminates any doubt.

New Shepard successfully completed 38 crewed missions, carrying a total of 98 passengers to suborbital space, showcasing a strong safety record for commercial space tourism.

Technical Challenges: Why the Timeline Matters

The accelerated Artemis III timeline creates genuine technical challenges that explain why Blue Origin needed to pause other programs.

Developing a new lunar lander is not something you rush. The engineering process typically involves:

- Concept development (6-12 months): Design options are evaluated, trade studies are conducted, and a baseline design is selected.

- Preliminary design (12-18 months): Detailed engineering begins, subsystems are defined, and specifications are baselined.

- Detailed design (18-24 months): Every component is designed, analyzed, and integrated with every other component.

- Test and integration (12-24 months): Prototype hardware is built and tested. Systems are integrated and verified.

- Validation and certification (12-18 months): Final testing confirms the system meets all requirements and is safe for crewed operations.

- Production and launch preparation (6-12 months): Flight hardware is manufactured and prepared for launch.

That's a minimum of 6-7 years from concept to first crewed flight, assuming minimal delays and no major redesigns. Blue Origin is being asked to compress this timeline significantly for Artemis III in 2026.

How can they do it? By starting from existing technology and leveraging previous development work. Blue Origin has been studying lunar landers for years. The company has subsystems that are closer to flight-ready than if starting from scratch. It has engineers with deep experience in this domain.

But even starting from an advantageous position, the timeline is aggressive. There's less margin for error, less time for retesting, and less time to fix problems that emerge during development.

That's where the New Shepard pause becomes essential. If Blue Origin were splitting its engineering talent, some people would be on lunar lander development while others managed the tourist program. In an aggressive schedule, that split is untenable. Every engineer, every technician, and every manager needs to focus on getting the lander ready.

Moreover, the manufacturing and testing infrastructure is shared. The facilities that prepare New Shepard for flight are the same facilities that would prepare lunar lander hardware. By pausing tourism, Blue Origin consolidates all manufacturing and test capacity onto the lunar program.

It's a resource management decision driven by the realities of systems engineering and schedule constraints. You can't reasonably develop a new crewed spacecraft system, meet government certification requirements, and achieve first flight in four years while simultaneously operating a tourism program. The company chose to focus on what matters most.

The Commercial Space Tourism Industry: What This Pause Means

Blue Origin's decision has implications that extend beyond the company itself. The commercial space tourism industry has been waiting for this sector to mature into a regular, reliable business. The pause is a setback for that vision.

Commercial space tourism has always been hampered by the extremely high cost per flight. At $450,000 per seat, New Shepard was never going to achieve high volume. The addressable market of ultra-wealthy individuals willing to spend that much for 11 minutes in space is finite. Industry estimates suggested maybe 500-1000 such customers globally.

Blue Origin probably assumed that as it flew more frequently, costs would decline. Lower costs would expand the market. Eventually, tourism would be a sustainable, profitable business.

But achieving that cost reduction requires volume, which requires building a reliable operational system. A two-year pause is a step backward in that progression. Customers who were planning to book flights get delayed. The industry loses momentum.

Virgin Galactic, another commercial space tourism company, is in a similar situation. The company is focused on its own engineering challenges and doesn't have the same government contract opportunities that Blue Origin does. Virgin Galactic is pursuing a different technical approach (suborbital spaceplane rather than ballistic rocket), but it's also struggling to achieve the flight frequency needed to build a sustainable business.

Meanwhile, SpaceX is taking a different approach with its Crew Dragon spacecraft. Instead of brief suborbital hops, SpaceX offers multi-day orbital missions where crew can conduct experiments, observe Earth, and experience extended weightlessness. SpaceX hasn't been as aggressive about tourism as Blue Origin, but the company has plans to offer such flights in the future as a complement to its government and commercial crew transport business.

The broader lesson is that commercial space tourism will likely remain a niche business for the foreseeable future. It's too expensive, too risky, and too limited in what it offers for most people. It will exist, but probably as an occasional luxury experience for ultra-wealthy customers rather than a mass market.

More importantly, companies like Blue Origin are realizing that the real business of space is not entertainment—it's infrastructure. Building the systems that enable government agencies, research organizations, and other space companies to accomplish their missions. That's where the sustainable, long-term business model is.

The Artemis Program Context: Why NASA Needed a Backup Lander

NASA's decision to fund Blue Origin's lunar lander alongside SpaceX's Starship HLS is worth understanding in detail, because it reveals how government agencies manage risk in complex space programs.

The Artemis program is the most expensive human spaceflight program since Apollo. NASA's budget for Artemis exceeds $100 billion over two decades. Congress scrutinizes every dollar. When something goes wrong, it becomes a political issue.

When SpaceX's Starship development encountered delays and failures, NASA's leadership faced a critical decision: do we stick with SpaceX as our only lunar lander option, or do we diversify?

Sticking with SpaceX had advantages. Starship's design is more capable than alternatives. If successful, it could eventually enable large-scale lunar operations. SpaceX has a track record of eventually solving hard problems, even if the path is messy.

But there were risks. Starship was unproven. The vehicle had suffered multiple failures. The timeline for achieving a flight-ready HLS was uncertain. If SpaceX couldn't deliver by 2026-2027, Artemis III would slip, and NASA would face enormous congressional criticism.

Funding Blue Origin's alternative lander was a form of insurance. It was saying: "SpaceX is our primary option, but if things don't work out, we need a backup." This is actually how government programs should work. Competition and redundancy reduce risk.

For Blue Origin, this was a once-in-a-generation opportunity. The company had been developing lunar lander concepts for years but didn't have a clear path to implementation. NASA's request essentially said: "Here's the path. Here's the funding. Make it happen."

The company seized that opportunity and made the resource allocation decision necessary to succeed: pause the less critical program (tourism) and focus entirely on the more critical one (lunar lander).

NASA also benefits from Blue Origin's approach because a focused, dedicated engineering team is more likely to deliver a reliable lunar lander than a split team working on multiple projects. When you have people's complete attention and focus, the quality of engineering usually improves.

The Artemis program aims for a crewed lunar landing by 2029, with political pressures accelerating the timeline. Estimated data.

Political Dimensions: The Trump Administration's Moon Landing Goal

One factor that's important but often overlooked is the political dimension of Artemis III's aggressive timeline.

The Trump administration, which took office in January 2025, has made a point of accelerating America's lunar program. The stated goal is to land humans on the moon before the end of the presidential term in January 2029. That's a significant acceleration from previous timelines.

This political goal has real consequences. It creates urgency at NASA. It influences budgeting decisions. It affects contractor selection. Companies like Blue Origin must respond to these political realities.

From Blue Origin's perspective, the accelerated timeline is both a challenge and an opportunity. It's a challenge because the schedule is aggressive. It's an opportunity because the company that delivers a working lunar lander on this timeline will have accomplished something remarkable and will be positioned as NASA's trusted lunar partner for future missions.

Political timelines have affected space programs before. President Kennedy's commitment to landing on the moon by 1970 (later revised to 1969) drove the entire Apollo program. Companies and agencies organized themselves around that political goal. Similarly, Blue Origin is organizing itself around Artemis III before the end of 2029.

When a political goal is this explicit, it filters down through every level of an organization. Engineers work longer hours. Priorities shift. Ancillary projects get deprioritized. New Shepard tourism fits perfectly in that category: important to the company's long-term vision, but not essential to meeting the political goal.

The Technology: What Blue Origin Is Actually Building

While Blue Origin hasn't released extensive technical details about its Artemis III lunar lander, industry observers and aerospace engineers have some informed assumptions about what the system probably looks like.

Blue Origin's lunar lander will likely consist of several components:

The Descent Module: This is the engine and fuel tanks that slow the spacecraft as it approaches the lunar surface. Blue Origin has extensive experience with rocket engines (the company manufactures the BE-4 engine used on United Launch Alliance rockets), so the descent module leverages existing expertise.

The Crew Cabin: This is where astronauts will ride during descent and ascent, and where they'll shelter during crew transfers from the Gateway station to the lander. The cabin must provide life support, radiation protection, and structural safety for two astronauts.

The Ascent Module: This is the vehicle that launches from the lunar surface back to orbit. It carries the crew and must be small and light enough to be lifted by the descent module's engines.

Power Systems: The lander needs electricity for life support, computers, communications, and scientific instruments. This is probably a combination of fuel cells and batteries, similar to how the Lunar Module worked during Apollo.

Communications and Navigation: The lander must navigate precisely from orbit to the landing site and maintain contact with Earth and the Orion spacecraft.

Blue Origin's approach is probably more conventional than SpaceX's Starship concept. Rather than a massive, fully reusable vehicle, Blue Origin is probably building a specialized lander that uses proven technology and engineering approaches. This is a lower-risk, higher-confidence path, though it's less revolutionary than Starship.

The actual engineering is vastly more complex than this summary suggests. Qualifying all the systems for human spaceflight, meeting NASA's safety requirements, integrating with the Artemis architecture, and ensuring everything works in the lunar environment involves thousands of engineers working on thousands of components for years.

That's why pausing New Shepard was necessary. Those engineering resources, testing facilities, and management attention are all needed for the lunar lander. There's no spare capacity to maintain a parallel program.

The Gateway Station: The Missing Piece

One element of the Artemis architecture that doesn't get as much attention as it should is the Gateway station. This is a planned orbital outpost around the moon that will serve as a staging point for lunar landings.

The Gateway won't be on the lunar surface like the Apollo Lunar Module was. Instead, it will orbit the moon in a high altitude, distant retrograde orbit. Astronauts will live on the Gateway for several days, then transfer to Blue Origin's (or SpaceX's) lunar lander for the descent to the surface. After conducting scientific work on the moon, they'll return to the Gateway and then fly back to Earth in the Orion spacecraft.

This architecture is different from Apollo, where the Command Module orbited the moon while the Lunar Module descended. The Gateway is on the surface of things, adding complexity because the lander must be capable of autonomous rendezvous with a moving orbital target.

The Gateway is being developed by NASA and international partners. It will carry power systems, communications equipment, and life support capabilities. The lander crew will dock with it, transfer, and establish the sequence of operations.

Blue Origin's lander must be designed to work within this architecture. It needs docking mechanisms that are compatible with the Gateway. Its life support must be compatible. Its navigation must account for the orbital mechanics of rendezvous with a moving target.

This is actually one reason why SpaceX's Starship presents challenges. Starship is so large and designed for such different mission architecture (massive cargo delivery to the lunar surface) that integrating it with the Gateway presents unusual challenges. Blue Origin's more conventional approach aligns more naturally with the Gateway-based architecture.

Blue Origin and Virgin Galactic focus on suborbital flights with lower costs, while SpaceX offers more expensive, multi-day orbital missions. Estimated data highlights different business models.

The Manufacturing and Testing Challenge

Building a crewed spacecraft is not just an engineering challenge. It's a manufacturing and testing challenge of extraordinary complexity.

Once Blue Origin completes the detailed design of its lunar lander, engineers need to build prototypes and test hardware. This involves:

Structural Testing: Verify that the lander's structure can withstand the stresses of launch, trans-lunar flight, lunar descent, surface operations, ascent, and return to Earth. This typically involves building test articles and subjecting them to loads that simulate the actual mission environment.

Propulsion Testing: Test all engines under conditions that simulate the lunar environment. Engines must restart reliably after being idle for days. Fuel and oxidizer systems must perform reliably in the lunar vacuum.

Life Support Testing: Verify that oxygen generation, carbon dioxide removal, temperature control, and humidity management all work reliably in a closed-loop system for multiple crew for multiple days.

Avionics Testing: Test all computers, sensors, and control systems under simulated failure conditions. Space systems are designed to survive failures and degrade gracefully.

Thermal Vacuum Testing: Test the entire system in a chamber that simulates the thermal and vacuum environment of space. This is one of the most important tests because the vacuum environment produces unexpected effects on materials and systems.

Integrated Systems Testing: Test all systems working together. This is where you discover that the communications system generates electromagnetic interference with the guidance system, or that the thermal system isn't compatible with the power system.

Each of these testing phases can take months or years. Failures discovered during testing often require redesign, which delays the schedule further.

Blue Origin's manufacturing and testing infrastructure needs to support all of this work. The company has substantial facilities at its West Texas headquarters and other locations, but accommodating the lunar lander development requires scaling up capacity.

By pausing New Shepard, Blue Origin frees up manufacturing capacity, testing facilities, and engineering support personnel. Those resources can now flow entirely into the lunar program.

Financial Implications: The Cost of Pursuing Lunar Ambitions

Pausing New Shepard has financial implications for Blue Origin that extend beyond the immediate loss of tourism revenue.

First, there's the revenue impact. If Blue Origin was generating

But Blue Origin has an advantage that most companies don't: a billionaire founder with deep pockets. Bezos has committed to spending billions on Blue Origin over the coming years specifically to develop advanced space capabilities. The company isn't dependent on tourism revenue to survive. It can absorb the pause because it has other revenue sources and investor backing.

Second, there's the investment requirement for lunar lander development. Building a crewed spacecraft requires spending hundreds of millions, possibly billions. Even with NASA's contract covering significant costs, Blue Origin is investing company capital into development, testing, and manufacturing.

Third, there's an opportunity cost. Capital and resources devoted to the lunar lander could theoretically be deployed to other ventures. Blue Origin has other projects in development, including the New Glenn heavy-lift rocket and various satellite and logistics programs. The lunar lander focus means slower progress on those initiatives.

But from a strategic perspective, these costs are justified. A successful lunar lander positions Blue Origin as a critical player in deep space. The company becomes NASA's preferred partner for lunar logistics, surface operations, and eventually Mars missions. That market opportunity is worth far more than the near-term costs.

Moreover, the technology developed for lunar operations has applications in other domains. Life support systems, autonomous navigation, thermal management, and propulsion technologies all have spinoff applications in commercial spacecraft, orbital tourism, and satellite servicing.

Competitor Response: What SpaceX Is Doing

While Blue Origin is reorganizing around the lunar lander challenge, SpaceX is pursuing a different strategy.

SpaceX is continuing to develop Starship HLS while simultaneously pursuing other space commerce opportunities. The company is launching satellites, supporting government national security missions, resupplying the International Space Station, and even developing plans for space tourism (brief flights aboard Dragon capsule).

SpaceX's advantage is that the company has built multiple revenue streams. It's not dependent on any single program. If lunar lander development slows, the company can redirect resources to other projects and still remain profitable.

SpaceX is also benefiting from the Starship development process itself. Each test flight, even the failures, generates data that improves the vehicle. The company's iterative approach, while unconventional, is producing rapid technological advancement.

For Artemis, SpaceX is the lead contractor for HLS. NASA is committed to Starship as the primary lunar lander. Blue Origin's backup lander is important, but if SpaceX delivers, it's the vehicle that will be used.

From SpaceX's perspective, the current arrangement is acceptable. The company gets primary responsibility for the most ambitious lunar architecture, and Blue Origin absorbs the risk of a backup solution. If SpaceX succeeds, SpaceX gets the credit and the dominance of lunar operations. If SpaceX fails, Blue Origin is there as a backup, but SpaceX still built the more advanced technology.

This dynamic between SpaceX and Blue Origin will shape the entire Artemis program. It's a competition, but also a partnership, with both companies working toward the same ultimate goal: humans back on the moon.

The focus of commercial space companies has shifted significantly from tourism and novelty to infrastructure and services, with most companies now prioritizing the latter. (Estimated data)

Lessons for the Commercial Space Industry

Blue Origin's decision to pause New Shepard teaches several lessons for the broader commercial space industry.

First, government contracts are more important than consumer services. In the near term, consumer services like space tourism generate revenue and public attention. But government contracts provide stable, long-term funding that supports sustained operations and technological advancement. Companies that want to survive and thrive in space need government relationships.

Second, focus is critical. Companies that try to do everything end up doing nothing very well. Blue Origin made the strategic choice to focus entirely on lunar lander development. That focused intensity is more likely to produce success than a divided effort across multiple programs.

Third, timing matters. The window to win the Artemis contract and establish yourself as NASA's trusted deep-space partner is limited. Miss it, and you're relegated to secondary roles. Blue Origin is making a time-limited bet that the lunar lander program is where the future is being written.

Fourth, infrastructure investments have long payoff periods. Space companies can't expect near-term profitability. They need patient capital and long-term thinking. Bezos backing Blue Origin with unlimited capital is what allows the company to make decisions like pausing profitable programs.

Fifth, national space policy matters. The Trump administration's commitment to lunar landing by 2029 directly influenced Blue Origin's strategy. Companies that understand and anticipate government policy can position themselves to benefit when priorities shift.

The Two-Year Timeline: What Happens Next

Blue Origin says the New Shepard pause will last for at least two years. What actually happens after two years?

Several scenarios are possible:

Scenario 1: The pause becomes permanent. If the lunar lander program is successful and Blue Origin secures additional government contracts for lunar operations, the company might decide there's no point in resuming tourism. The infrastructure, personnel, and attention are better deployed elsewhere.

Scenario 2: Tourism resumes at a reduced scale. Blue Origin might restart New Shepard flights after two years, but at a much lower frequency than before. Maybe 4-6 flights per year instead of 10-12. This allows the company to maintain some tourism business while keeping most resources focused on government programs.

Scenario 3: Tourism pivots to new capabilities. Instead of suborbital point-and-suborbital flights, Blue Origin might modify New Shepard or develop a new vehicle for orbital space tourism. Orbital flights are longer, more complex, but also more appealing to customers.

Scenario 4: New Shepard is sold or transferred. Blue Origin might decide that tourism isn't core to its mission and might sell the New Shepard system to another operator. Virgin Galactic or a new startup might acquire it and operate it as a standalone business.

From the current vantage point, Scenario 1 (permanent pause) or Scenario 2 (limited resumption) seem most likely. Blue Origin's fundamental mission is to develop space infrastructure, not run a tourism business.

But the important point is that the company made this decision consciously and deliberately. New Shepard isn't dead; it's just deprioritized. The difference matters.

Industry Trends: What This Signals About Commercial Space

Blue Origin's decision is part of a broader trend in commercial space: the maturation of the industry from novelty services to critical infrastructure.

A decade ago, the exciting stories in space were about commercial space stations and space hotels. Companies talked about orbital tourism, space-based manufacturing, and space elevators. These sounded revolutionary.

Today, the exciting stories are about lunar logistics, Mars missions, and orbital depots. The narrative has shifted from entertainment and novelty to exploration and infrastructure.

This shift reflects a market reality: there are only so many billionaires willing to pay $450,000 for 11 minutes in space. But there are unlimited opportunities for companies that provide services to government agencies, research organizations, and other space operators.

Blue Origin's pause symbolizes this maturation. The company is saying: "Tourism was a stepping stone. Our real mission is deeper. We're building the infrastructure for humanity's permanent presence in space."

Other companies will likely follow similar paths. Axiom Space, which is building commercial space stations, is focused on government and research customers. Rocket Lab is concentrating on dedicated launch services for satellite operators. Relativity Space is developing 3D-printed rockets.

The common pattern is clear: successful commercial space companies are those that identify critical infrastructure needs and solve them better, faster, or cheaper than the alternatives. Tourism and novelty services are secondary.

The Moonshot: Why This Matters for Human Exploration

Step back from the corporate strategy and resource allocation discussions. Why does any of this matter?

It matters because Blue Origin's decision to pause tourism and focus entirely on lunar lander development is, fundamentally, a bet on human exploration. It's a statement that the company believes humanity's future in space depends on developing reliable vehicles for exploring the moon, establishing a lunar presence, and eventually traveling to Mars.

This belief is probably correct. Sustainability in space requires infrastructure. It requires multiple companies building complementary systems. It requires government support and private capital working in concert. It requires sustained commitment over decades.

Blue Origin pausing tourism is a signal that the company is ready to commit. It's reorganizing its entire enterprise around a goal that extends decades into the future. That's not a decision companies make lightly.

If Blue Origin's lunar lander works, if it lands humans safely on the moon, if it becomes part of a sustainable architecture for lunar exploration, then the company will have contributed something historically significant. That matters more than tourism revenue.

Moreover, Blue Origin's success creates pressure on other companies to commit similarly. If Blue Origin's lander is reliable and NASA wants to use it repeatedly, SpaceX needs to ensure Starship HLS is equally reliable. Competition drives innovation and commitment.

This is how human space exploration works: companies make bold bets on future technology, government agencies support that development, and over time, the infrastructure emerges that enables the next stage of exploration.

Blue Origin's decision to pause tourism and focus on lunar landers is a contribution to that process. It's not as headline-grabbing as a celebrity floating in zero gravity, but it's far more important for humanity's future in space.

FAQ

What is New Shepard and why was it important?

New Shepard is Blue Origin's suborbital spacecraft designed to take tourists to the edge of space for a few minutes of weightlessness. It carried 98 passengers on 38 successful flights, including celebrities like William Shatner and Katy Perry. It was important as proof that commercial space tourism was viable, but it was never Blue Origin's long-term focus.

Why is Blue Origin developing lunar landers for NASA?

NASA's Artemis program aims to return humans to the moon. The agency contracted both SpaceX and Blue Origin to develop human landing systems, creating redundancy and reducing risk. Blue Origin's lunar lander will transport astronauts from lunar orbit to the surface for Artemis III and Artemis V missions, establishing humanity's sustained presence on the moon.

How long will Blue Origin pause New Shepard operations?

Blue Origin stated the pause will last at least two years, meaning no New Shepard tourist flights until approximately 2027. The company is redirecting all engineering, manufacturing, and operational resources toward lunar lander development. Whether flights resume after two years depends on the lunar program's progress and the company's strategic priorities at that time.

What are the Artemis III and Artemis V missions?

Artemis III is the first crewed lunar landing mission, currently targeted for 2026, where two astronauts will land near the moon's South Pole to conduct scientific research and explore water ice deposits. Artemis V is a follow-up mission that will expand lunar operations and lay groundwork for long-term lunar presence. Both missions rely on the lunar landers being developed by Blue Origin and SpaceX.

Is Blue Origin's approach different from SpaceX's for lunar landers?

Yes, significantly. SpaceX is developing Starship HLS, a massive, fully reusable rocket adapted for lunar operations that's revolutionary in scope. Blue Origin is building a purpose-built lunar lander using more proven, conventional technology. Blue Origin's approach is more conservative, while SpaceX's is more ambitious but riskier.

What makes the lunar lander development timeline so aggressive?

The Trump administration has made landing humans on the moon a stated goal for the end of the presidential term in January 2029, creating political pressure on NASA to accelerate Artemis timelines. This aggressive timeline drives every contractor, including Blue Origin, to reorganize resources and prioritize the lunar program. Normally, developing a crewed spacecraft takes 6-7 years; Blue Origin is being asked to deliver in less time.

How does NASA's Artemis program differ from Apollo?

Artemis uses a different architecture where astronauts live on the Gateway station orbiting the moon rather than the Command Module, and the lunar surface activities are designed for longer stays and eventual permanent presence. It also involves international partners and emphasizes sustainability and resource utilization rather than simple exploration and return.

Why is water ice at the moon's South Pole important?

Water ice in permanently shadowed craters is a strategic resource because it can be extracted and used for drinking water, oxygen production, and rocket fuel. This changes the economics of lunar exploration by providing resources on the moon rather than requiring everything to be launched from Earth, supporting the long-term sustainability of lunar operations.

What happens to Blue Origin's other space programs during the New Shepard pause?

Blue Origin continues developing New Glenn, its heavy-lift rocket, and various satellite and logistics programs, though at potentially slower pace than if full resources were available. The company is prioritizing the lunar lander program, but other strategic initiatives continue because the company has the financial backing and engineering talent to pursue multiple programs simultaneously.

Could Blue Origin's lunar lander compete with SpaceX's Starship on the moon?

Not directly. NASA selected both companies to develop complementary landers, and Blue Origin's system is designed for the Gateway-based architecture. If successful, Blue Origin's lander will enable Artemis III, while Starship HLS is designed for more ambitious, large-scale lunar operations. They're different solutions to different aspects of NASA's lunar program rather than direct competitors.

Conclusion: When Tourism Takes a Back Seat to History

Blue Origin's decision to pause New Shepard is ultimately about priorities. The company looked at its future and made a choice: we can run a moderately profitable space tourism business, or we can become one of the companies that enables humanity's return to the moon and long-term presence in space.

The company chose the latter. That choice involves sacrifice. Customers who wanted to fly to space get disappointed. Tourism revenue disappears. Engineering teams get reorganized. Focus tightens.

But the payoff, if Blue Origin executes successfully, is enormous. The company becomes NASA's trusted partner for deep space operations. The technology developed for lunar landers becomes applicable to orbital infrastructure, Mars missions, and beyond. The company that successfully lands humans on the moon multiple times becomes part of human history.

This is the transition that commercial space is undergoing right now. The novelty is fading. The infrastructure is being built. Companies that understood this transition early and positioned themselves accordingly are going to dominate the space industry for the next few decades.

Blue Origin understood it. That's why New Shepard is paused, and why the lunar lander program is the company's entire focus.

In 2027 or 2028, when Blue Origin's lunar lander successfully transports astronauts from the Gateway station to the lunar surface for the first time, people will remember this moment as the pivot point. This is when a space tourism company became something more important: a contributor to human space exploration. That transformation is worth the pause.

Key Takeaways

- Blue Origin is pausing New Shepard tourist flights for at least two years to focus entirely on developing lunar landers for NASA's Artemis program

- The company was selected alongside SpaceX to build human landing systems, positioning it as one of only two contractors capable of landing humans on the moon

- NASA's accelerated Artemis III timeline (targeting 2026 for first crewed landing) creates political and technical pressure that justified Blue Origin's reallocation of resources

- New Shepard tourism generated 2-3 billion, making the strategic pivot economically rational

- This shift reflects commercial space industry maturation: companies are transitioning from novelty services like tourism to critical infrastructure development like deep-space operations

Related Articles

- Blue Origin Pauses Space Tourism to Focus on Moon Missions [2025]

- Blue Origin's New Glenn Third Launch: What's Really Happening [2026]

- Lunar Spacesuits: The Massive Challenges Behind Artemis Missions [2025]

- NASA's Crew-11 Early Return: What the Medical Concern Means [2025]

- Artemis II Launch Delayed by Cold Weather: What You Need to Know [2025]

- Northwood Space Lands 50M Space Force Contract [2026]

![Blue Origin Pauses Space Tourism for NASA Lunar Lander Development [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/blue-origin-pauses-space-tourism-for-nasa-lunar-lander-devel/image-1-1769872070891.jpg)