NASA Used Claude to Plot Perseverance's Mars Route: The Future of Autonomous Exploration

Let me set the scene for you. It's December 2024, and somewhere inside NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, a team of engineers is doing something they've never done before. They're not manually plotting waypoints on a map of the Jezero Crater on Mars. Instead, they're asking an AI chatbot to do it.

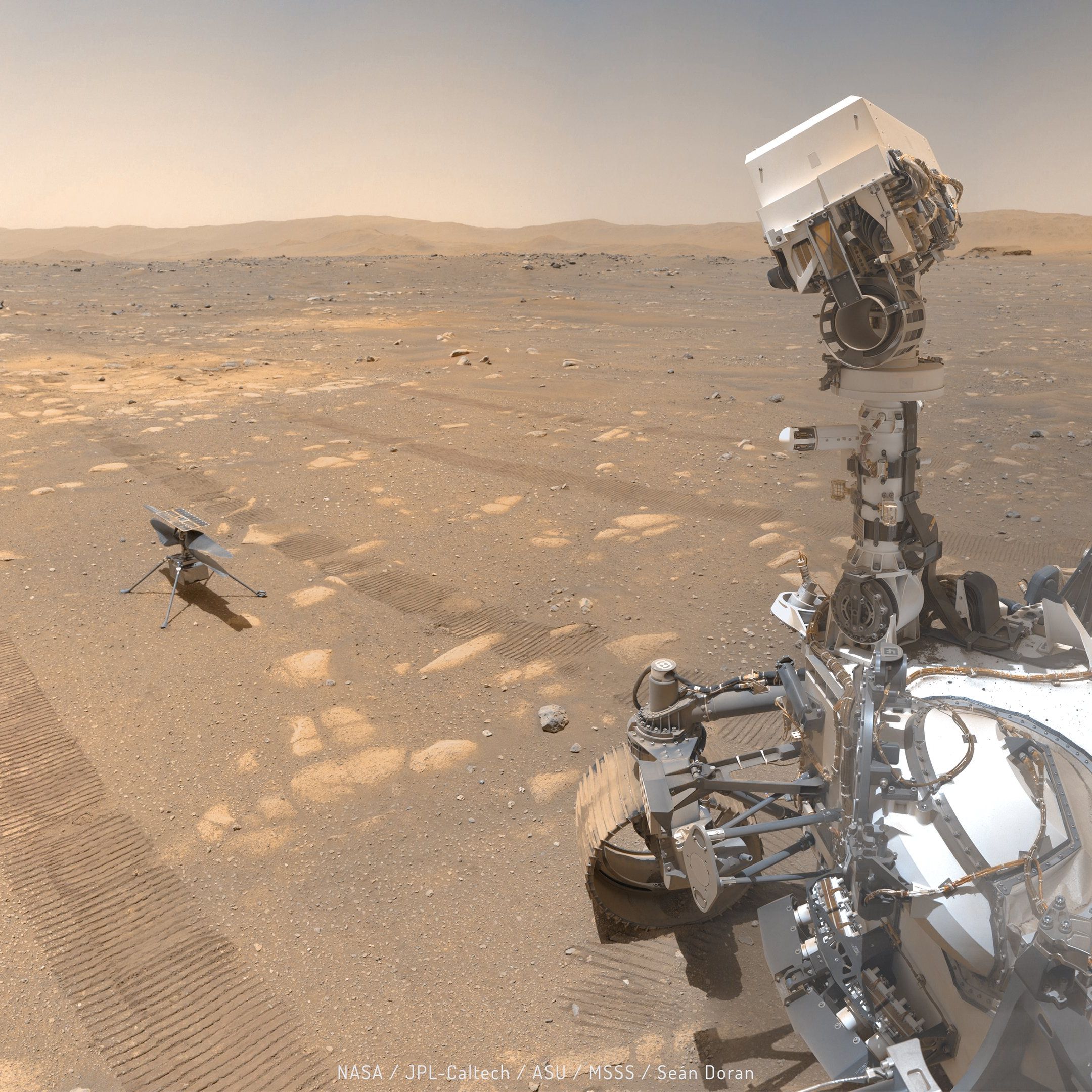

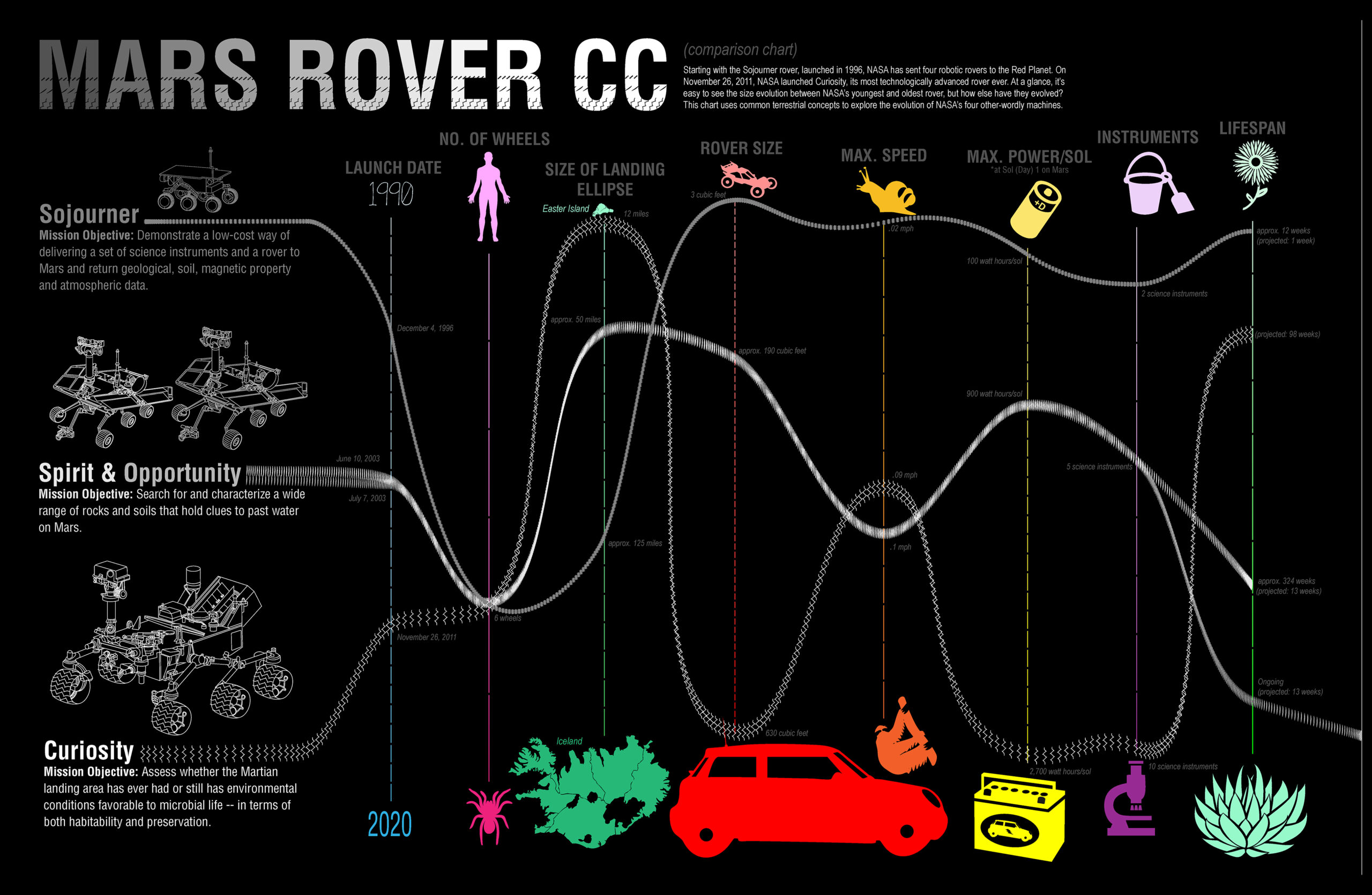

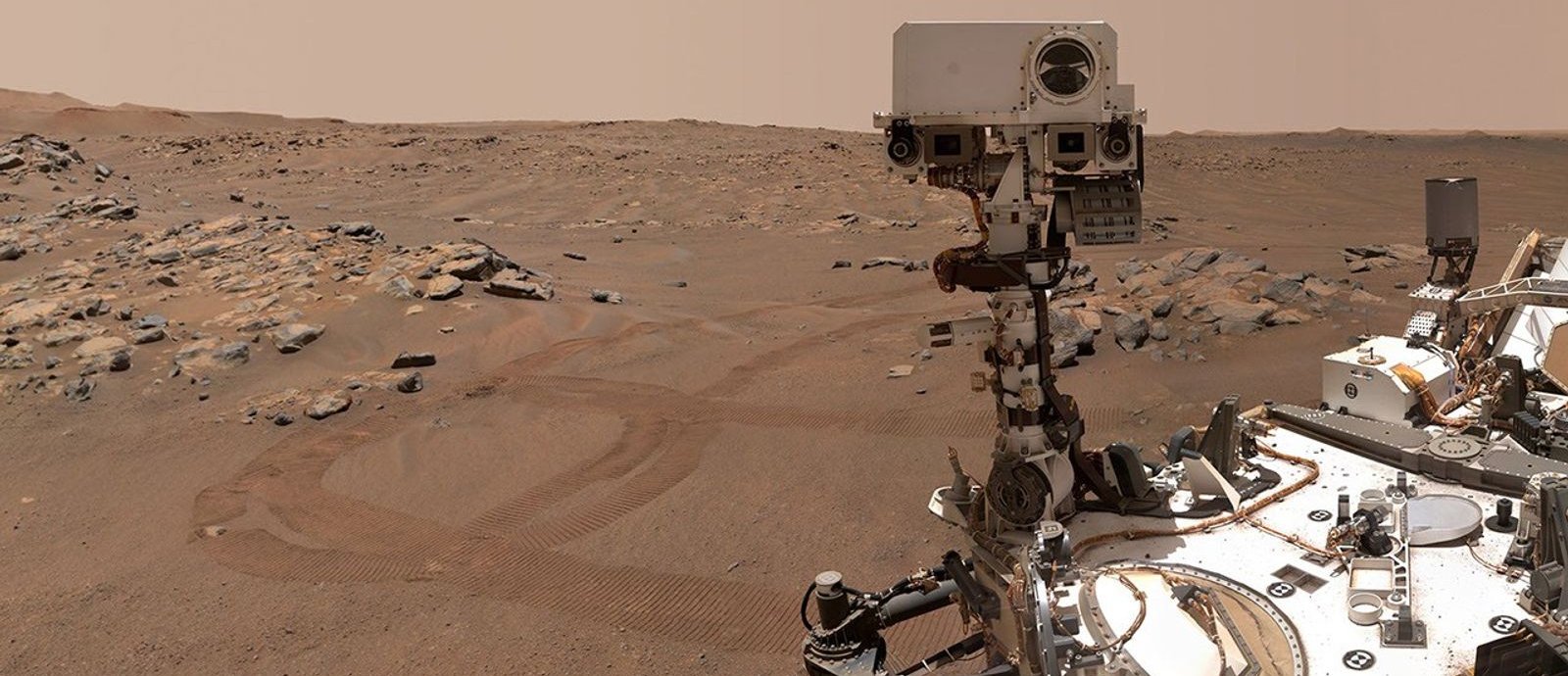

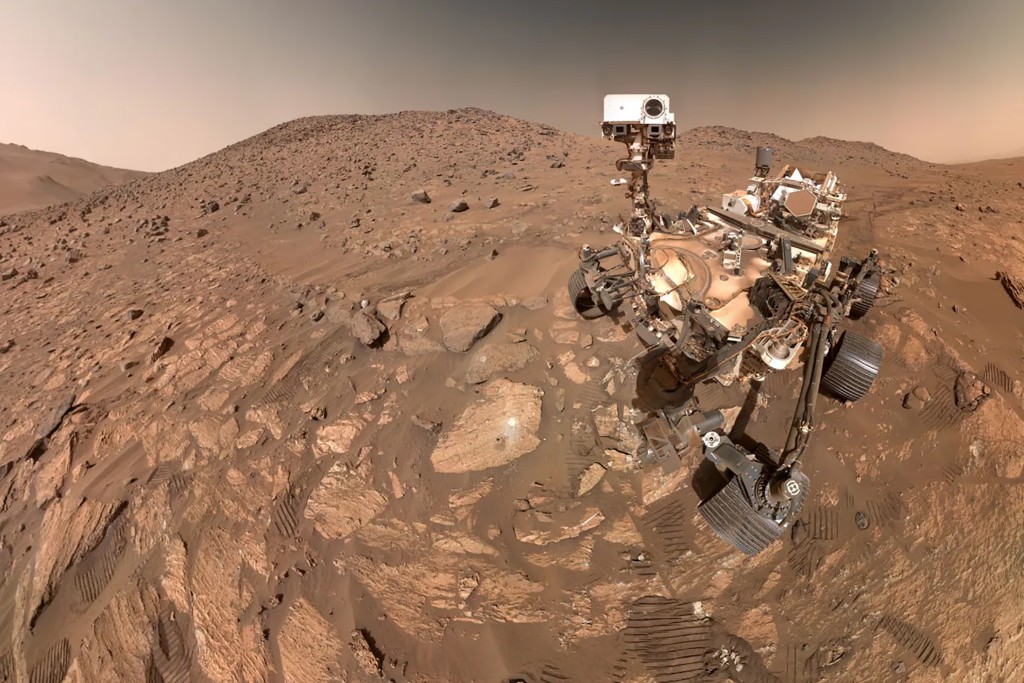

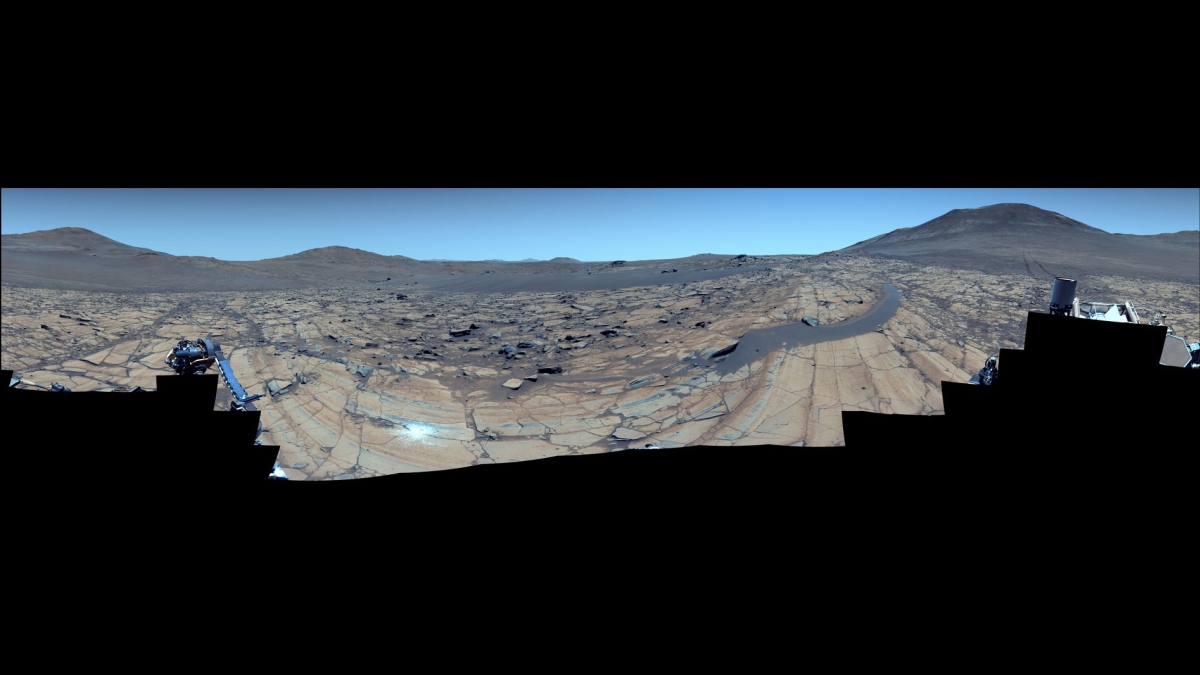

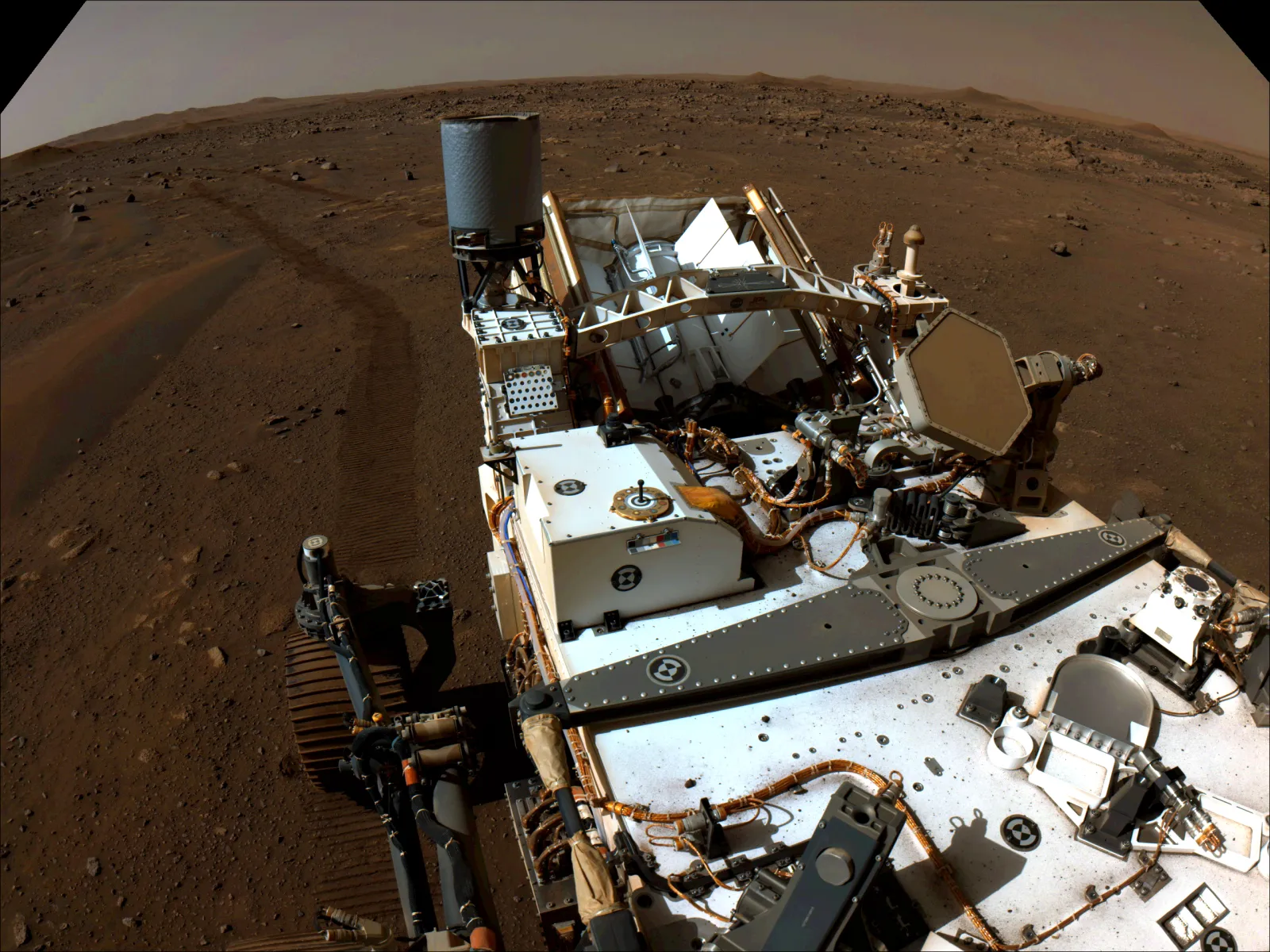

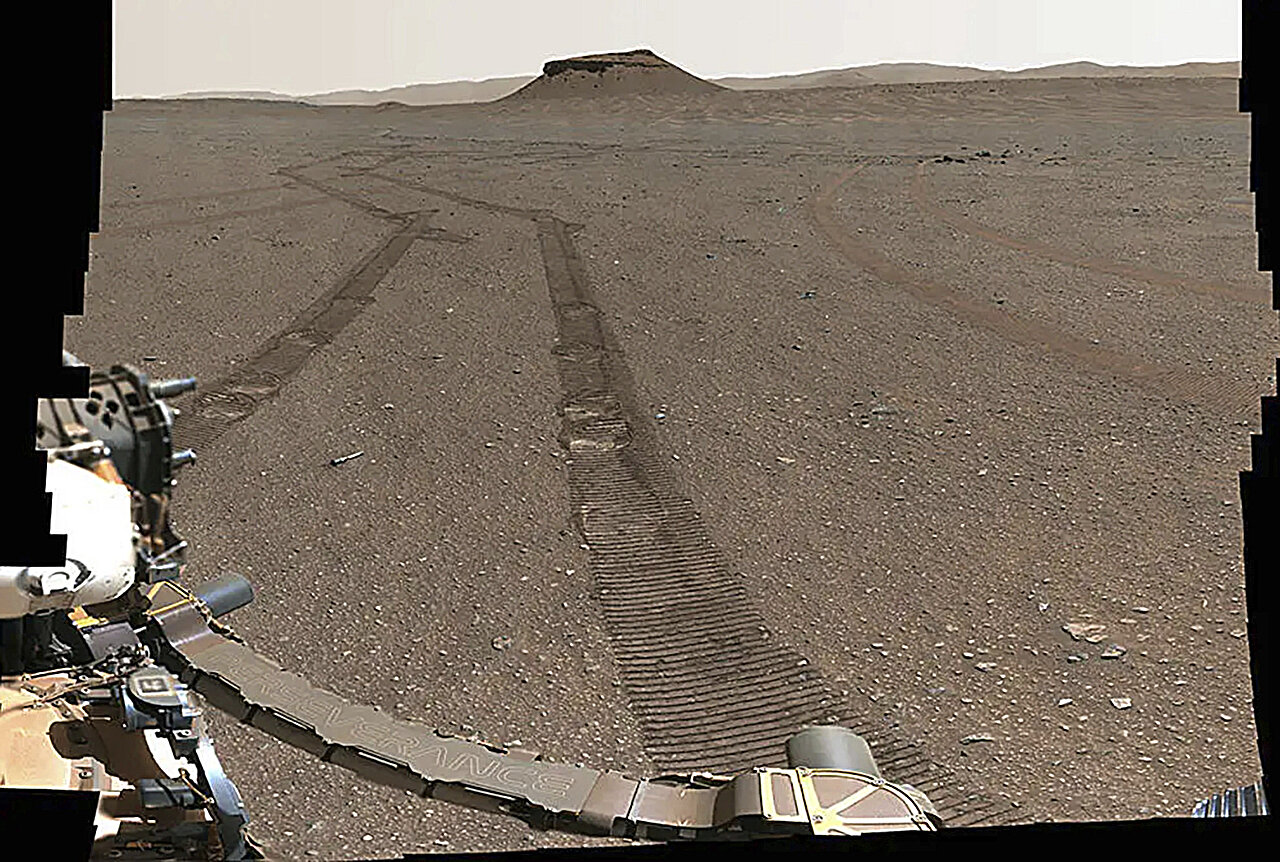

NASA's Perseverance rover, a car-sized robot that's been exploring Mars since February 2021, just completed a 400-meter drive (about 437 yards) through a rocky section of the Jezero Crater. The route wasn't designed by a human engineer painstakingly stitching together satellite imagery and onboard camera feeds. It was plotted by Claude, Anthropic's large language model, with only minor adjustments needed before the rover took its wheels forward, as detailed in Engadget's report.

This might sound routine to someone who's used Chat GPT to draft an email, but it's genuinely historic. This is the first time NASA has used a large language model to autonomously plan a route for one of its rovers on another planet. Let that sink in for a moment. We've moved from asking AI to write poetry to asking it to navigate Mars.

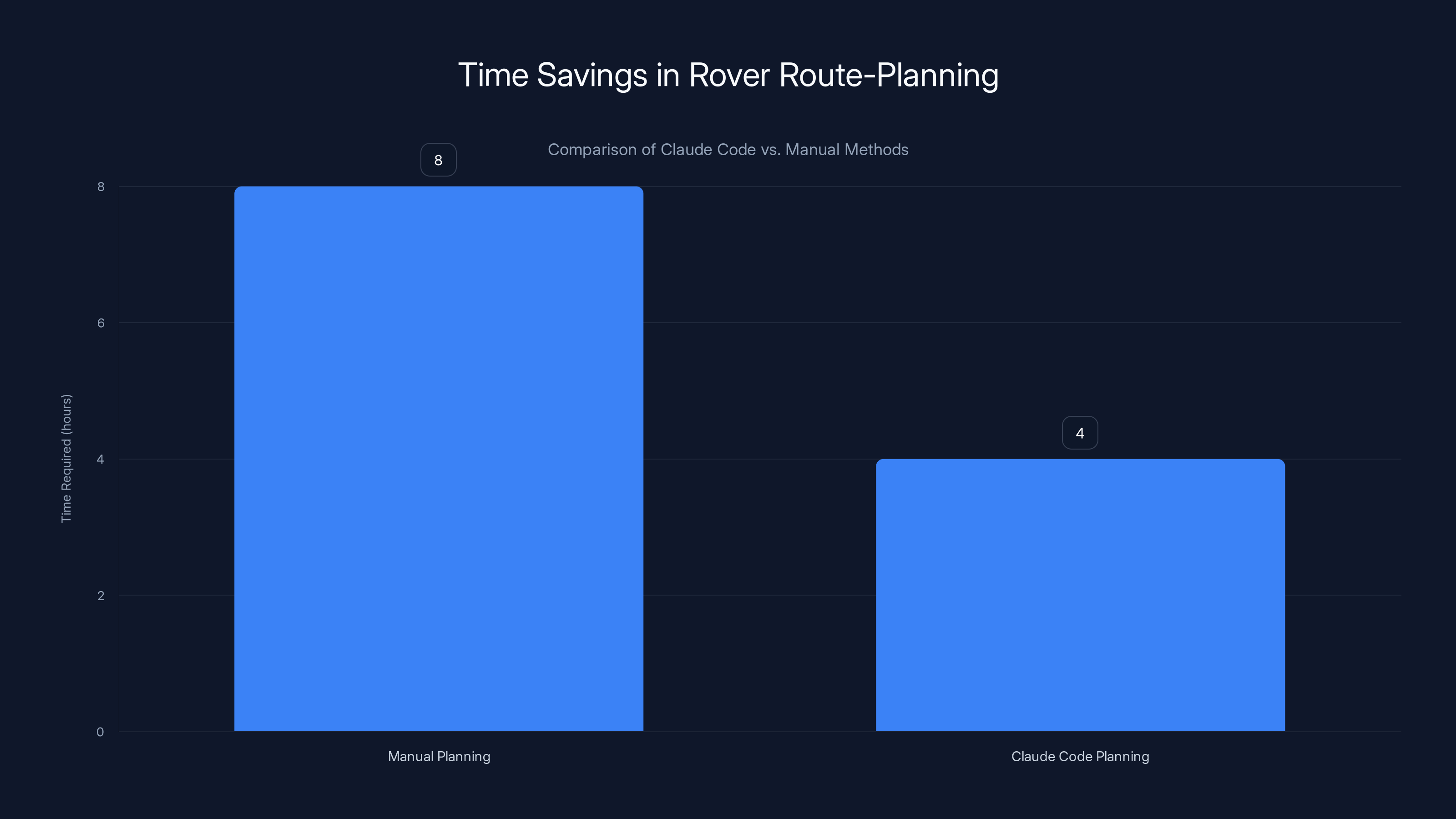

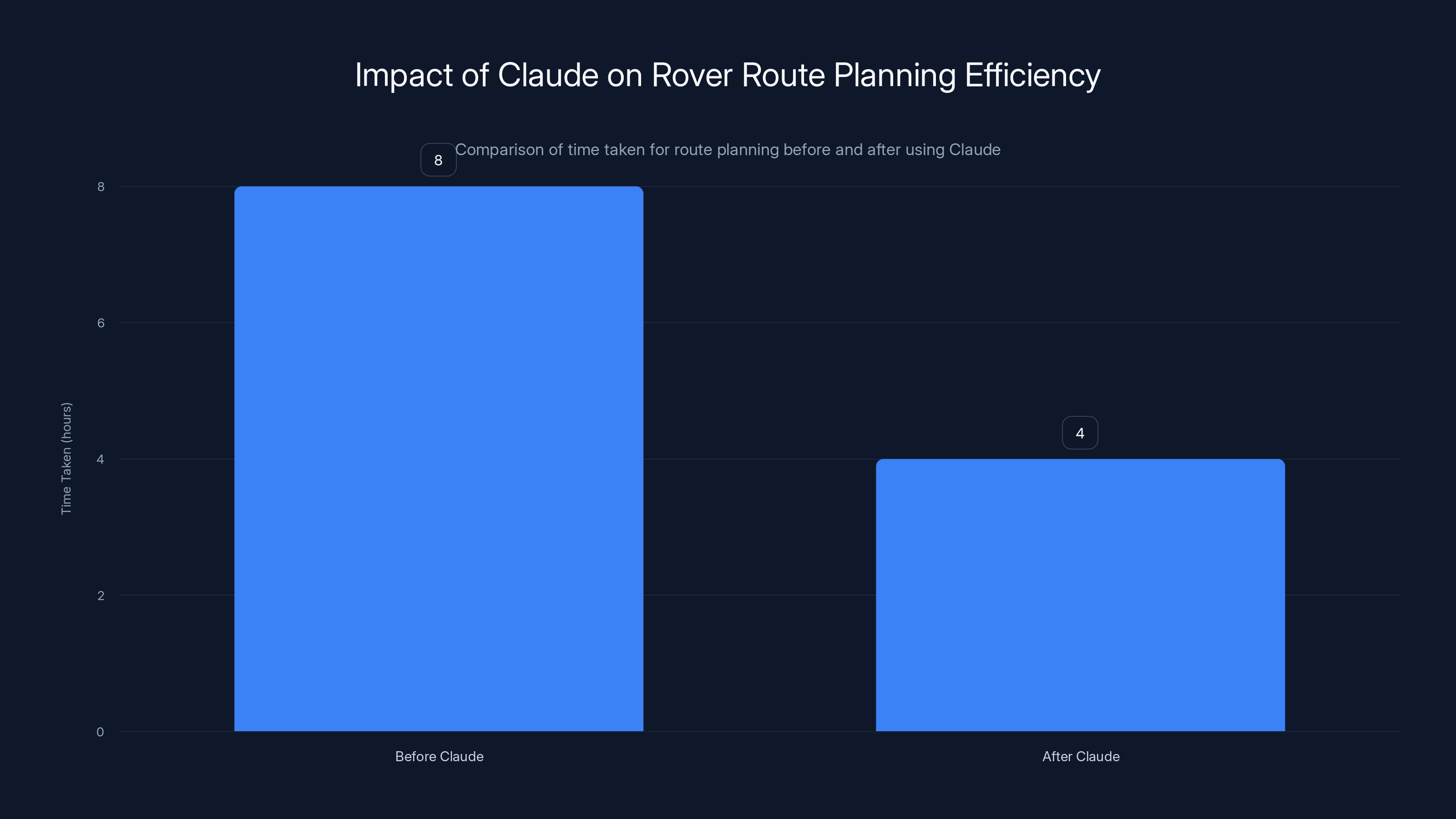

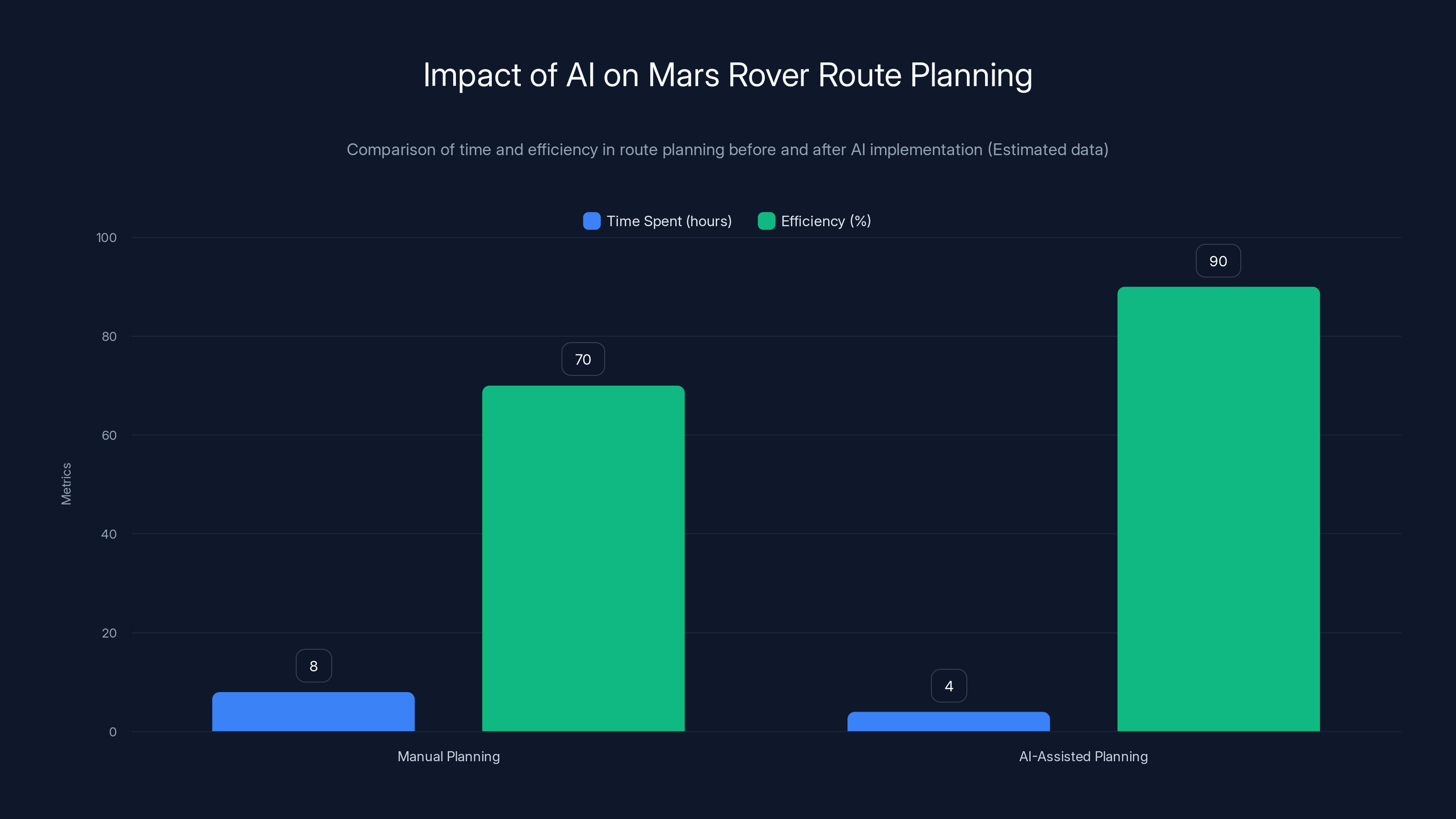

What's fascinating isn't just that it worked. It's how it worked, why it matters, and what it tells us about the future of space exploration. NASA says the approach cut route-planning time in half and made the rover's journeys more consistent. Engineers got to spend less time on tedious manual planning and more time on science. For an agency that's been asked to do more with less—literally half the workforce it had during Apollo—that efficiency matters, as noted in NASA's official news release.

But before we get ahead of ourselves talking about sending Claude to the Moon or teaching it to drive a rover on Europa, let's understand what actually happened here. Let's break down how NASA convinced a chatbot to plan a route on Mars, why it's harder than it sounds, and what this means for the future of space exploration.

The Perseverance Rover: Five Years of Groundbreaking Discovery

Before we talk about AI route-planning, you need to understand what Perseverance actually is and why this rover is so important to NASA's long-term goals for Mars exploration.

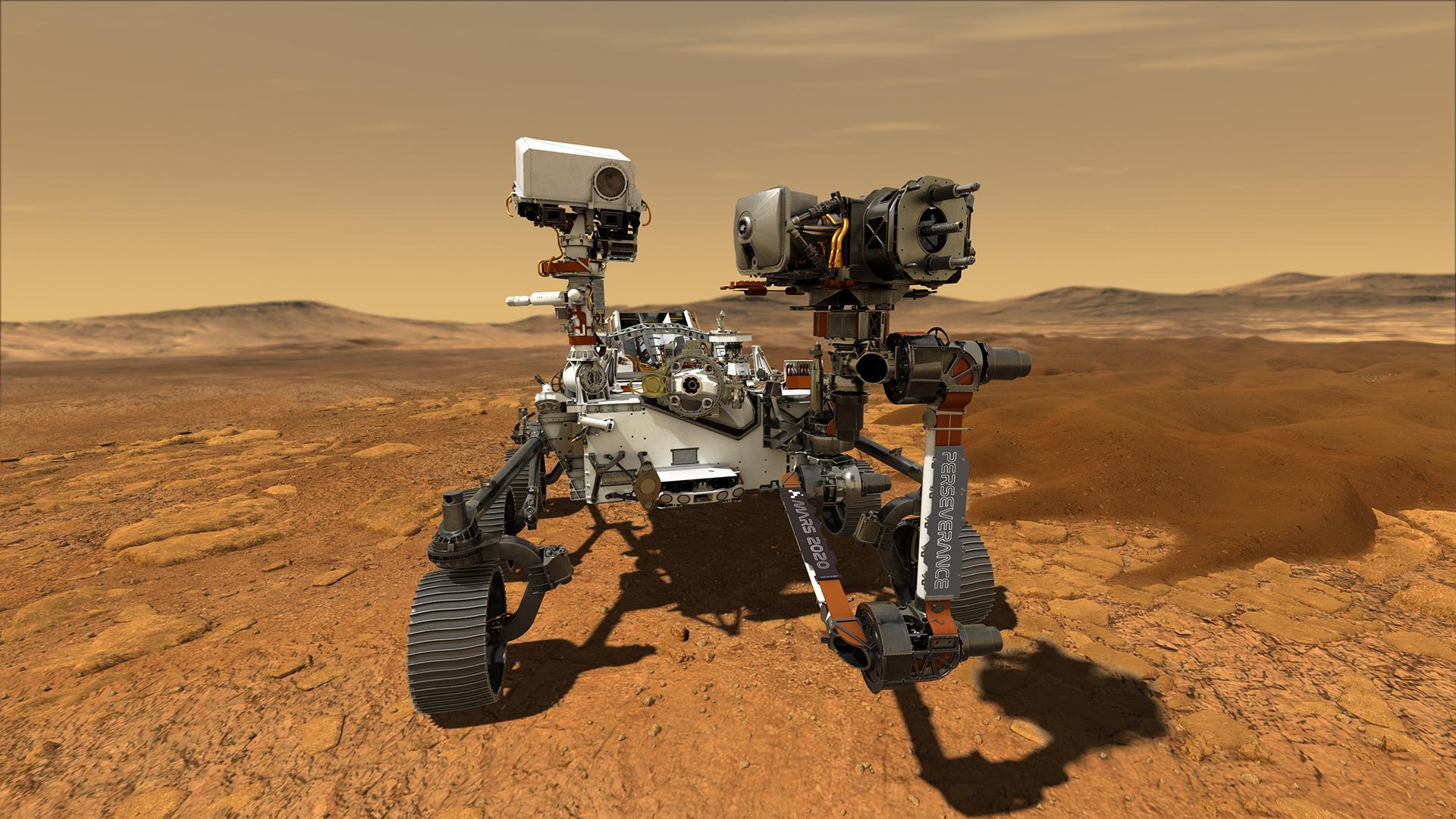

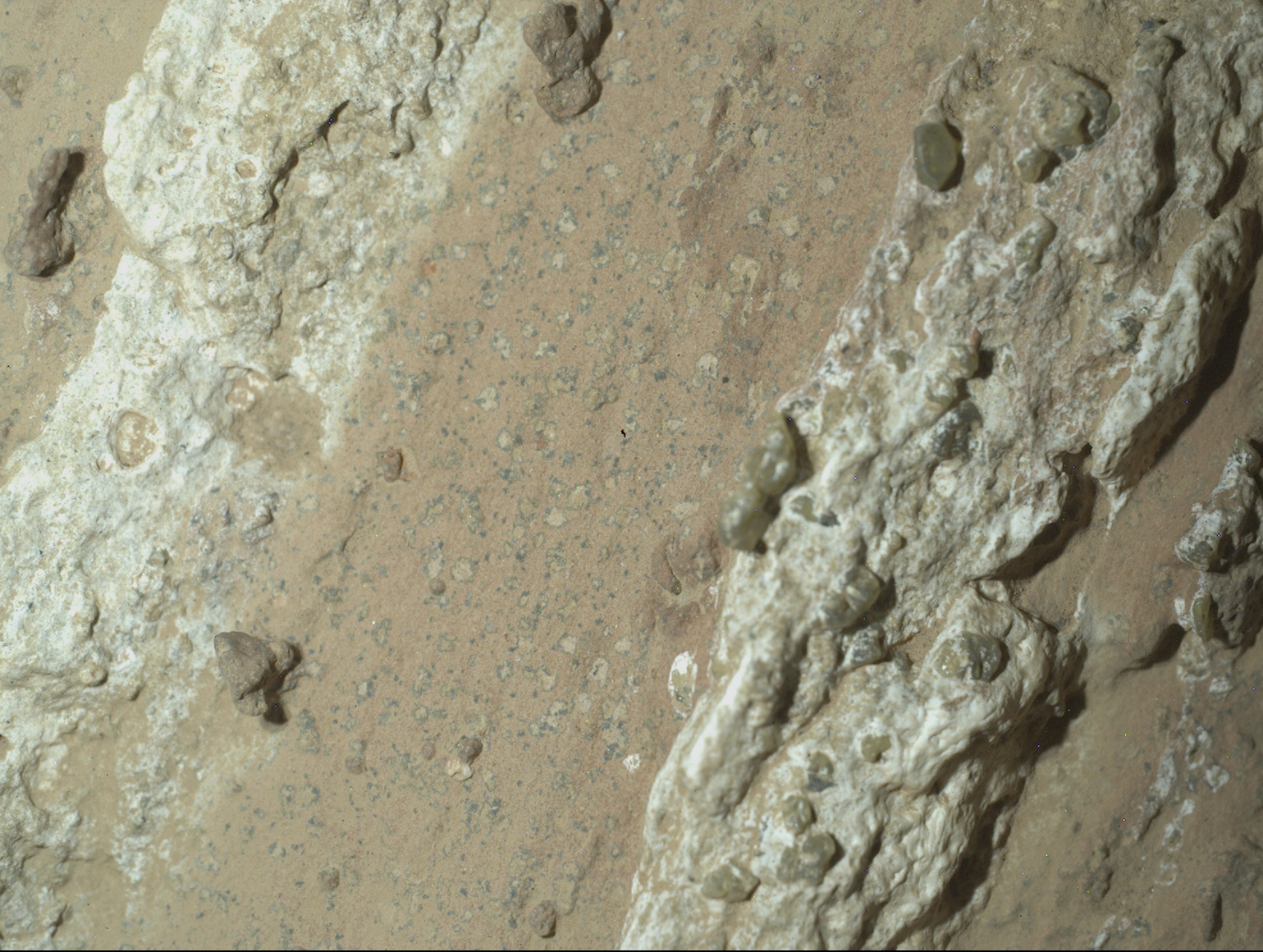

Perseverance isn't a small, nimble rover. It's six wheels of rover packed into a 900-kilogram chassis about the size of an SUV. It landed in the Jezero Crater in February 2021 as part of NASA's ambitious Mars 2020 mission. The rover's primary goal wasn't just to explore Mars—it was to search for signs of ancient microbial life and collect rock samples that would eventually be returned to Earth for detailed analysis, as outlined by NASA's mission overview.

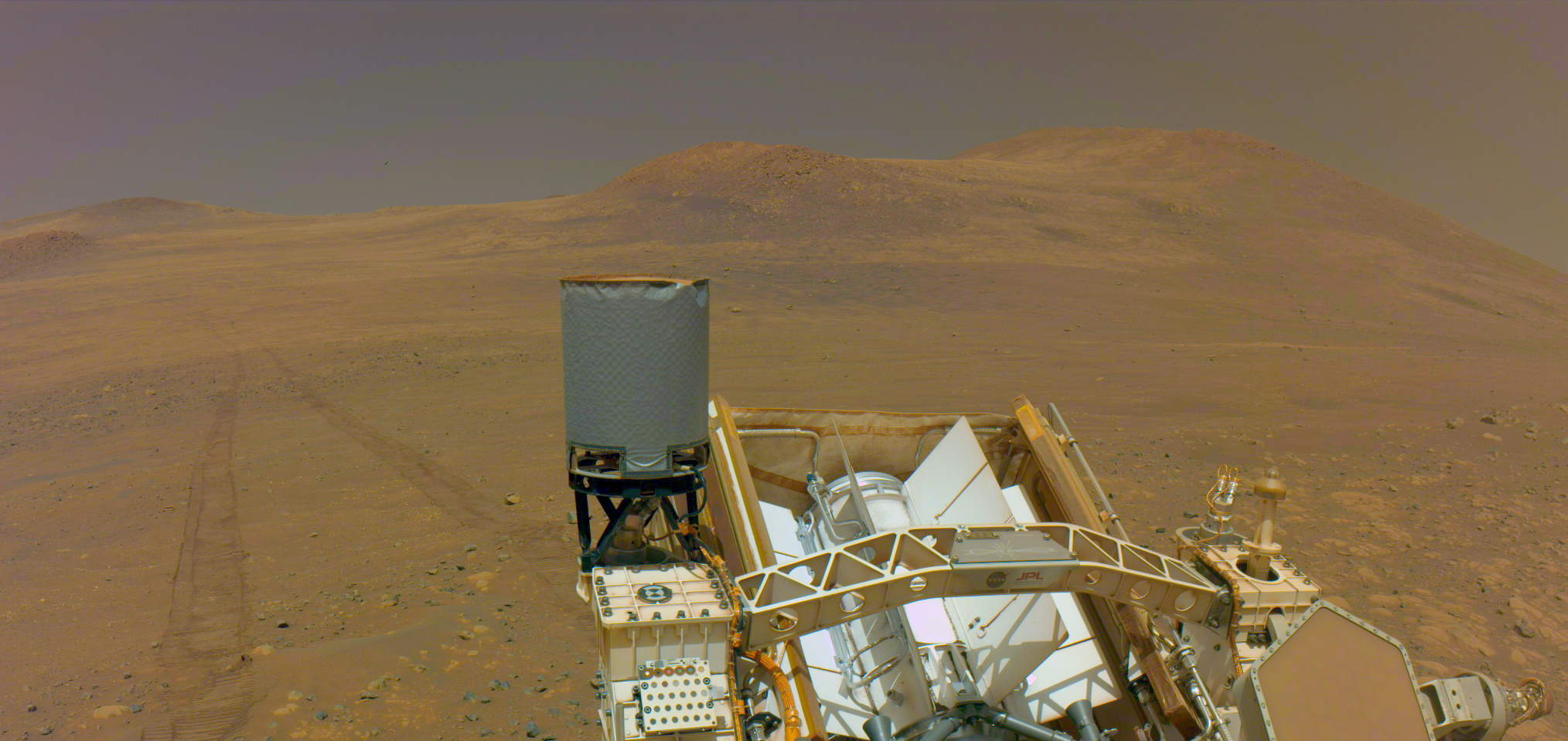

In nearly five years of operation, Perseverance has accomplished some genuinely remarkable feats. The rover transmitted the first audio recordings ever captured on Mars, letting people on Earth hear wind moving across the Martian surface and the sounds of the rover's own wheels grinding over rocks. It's been the first to use a laser called PIXL (Planetary Instrument for X-ray Lithochemistry) to identify the chemical makeup of Martian rocks from a distance. It's also served as a test platform for new technologies that might help future human missions to Mars, as reported by Earth.com.

But the rover's most important work might be the simplest: driving from point A to point B safely. That's where route-planning comes in.

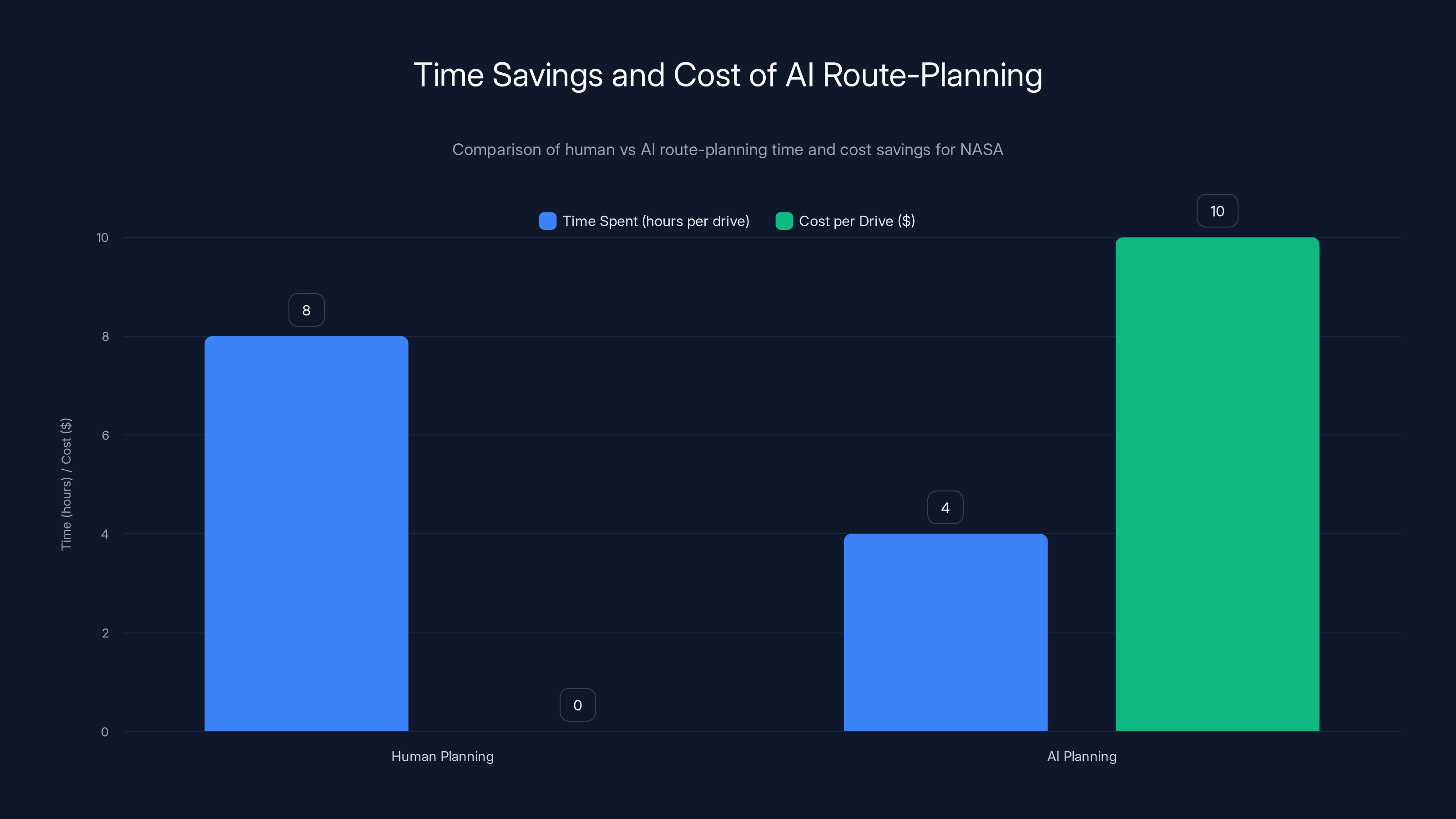

AI route-planning with Claude reduces planning time by 50%, saving NASA 1,000-2,000 engineering hours annually. Cost per drive is minimal compared to savings.

Why Route-Planning on Mars Is Incredibly Complex

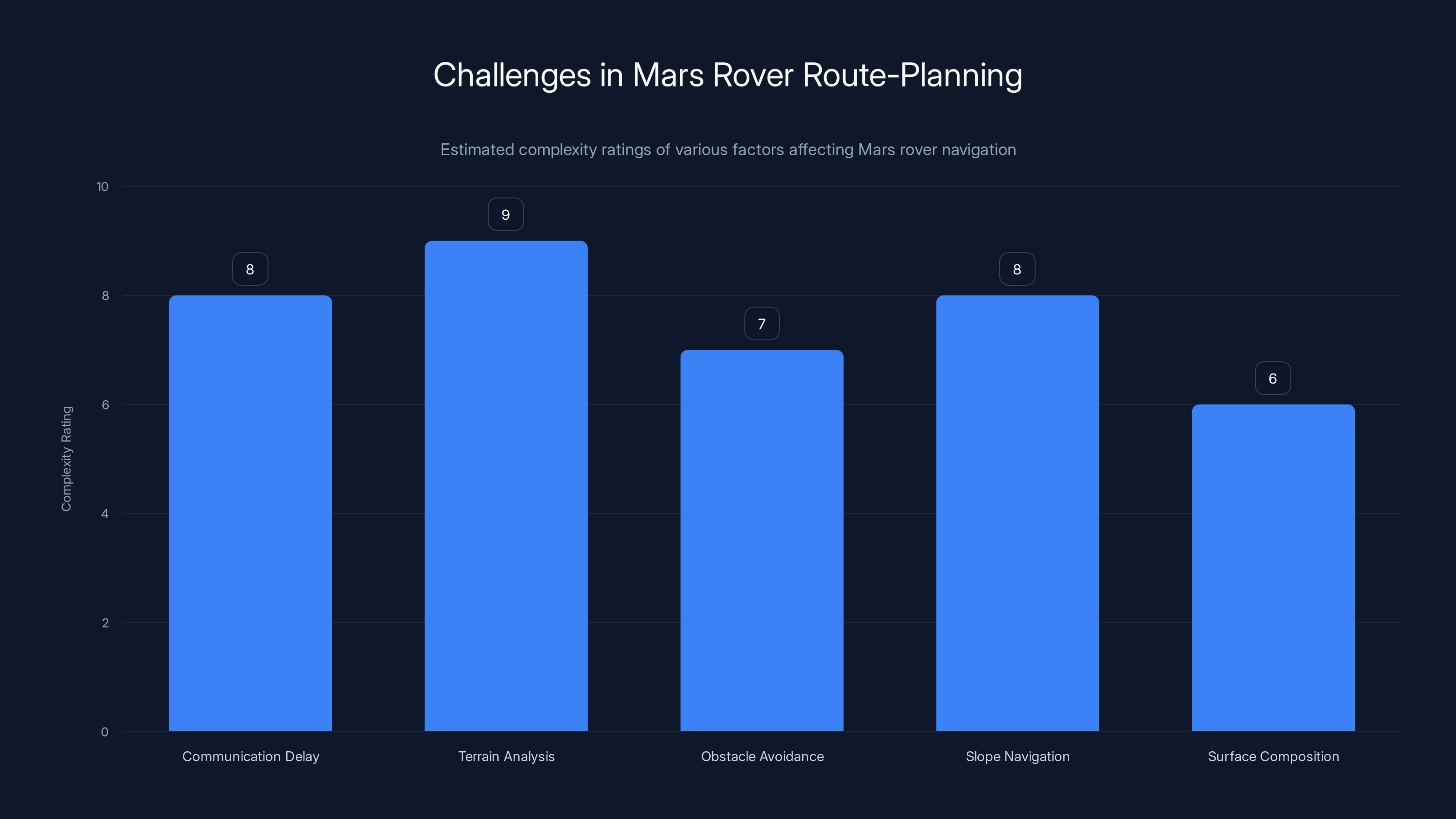

Here's what sounds straightforward but actually isn't: telling a rover to drive from one location to another 238 million miles away.

On Earth, if you want to send a robot somewhere, you program it with a destination, maybe some obstacle avoidance algorithms, and let it figure out the details. The communication delay is measured in milliseconds. If something goes wrong, you can correct it in near real-time.

On Mars, everything is different. The communication delay between Earth and Mars ranges from 3 to 22 minutes depending on where the planets are in their orbits. You can't send a command and expect an immediate response. You can't tell the rover "turn left" and see it happen a second later. By the time the command reaches Mars, conditions on the ground might have changed.

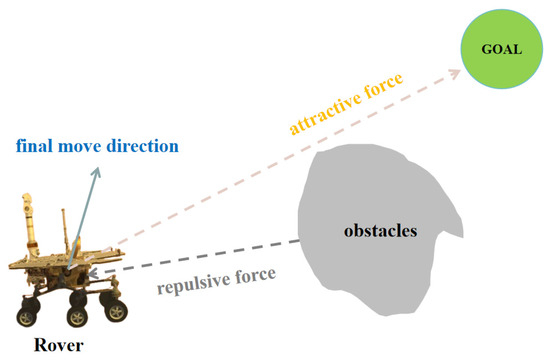

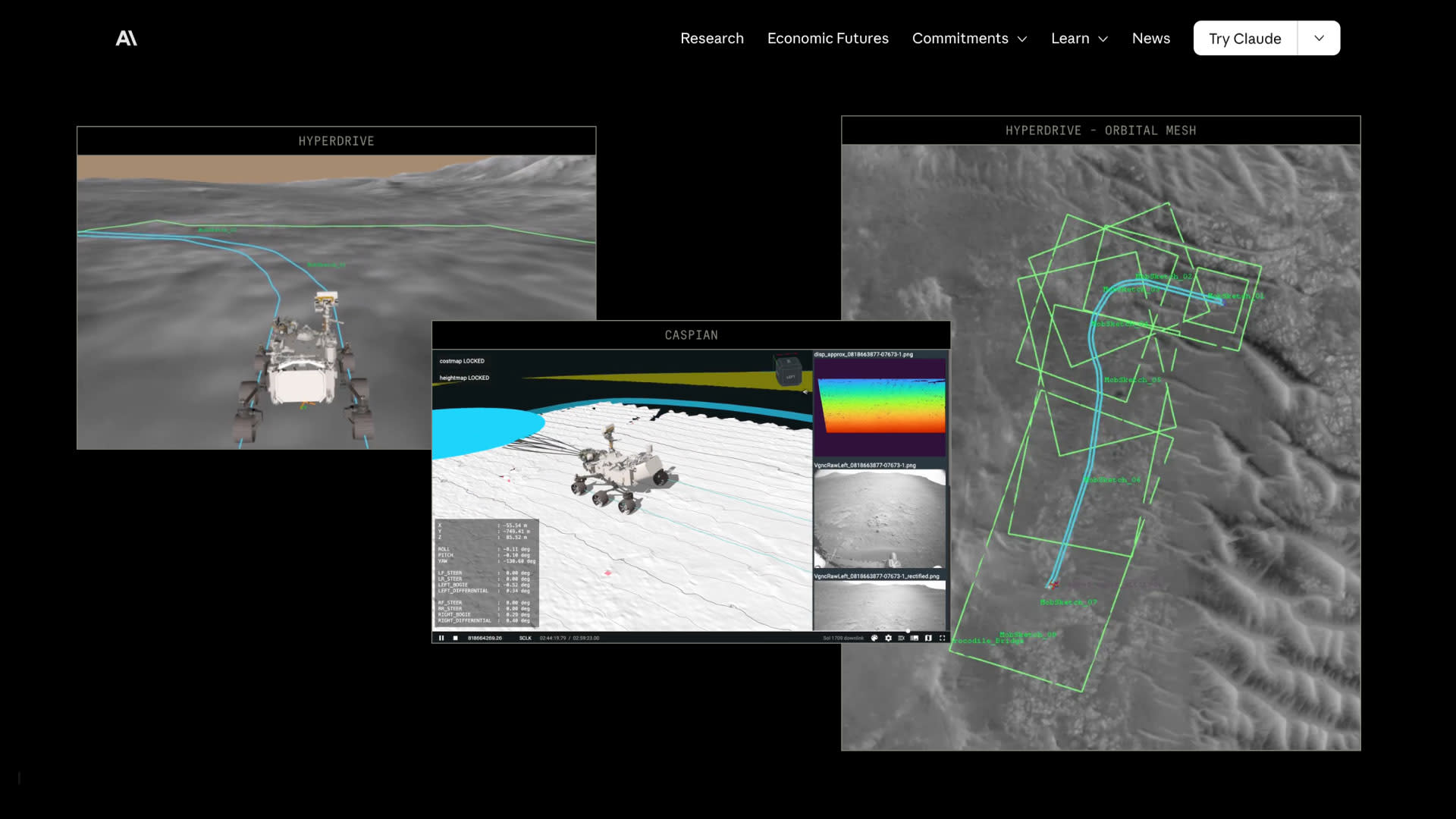

That's why NASA doesn't send simple directional commands. Instead, the rover's operators create a detailed "breadcrumb trail" of waypoints that the rover should hit. Engineers manually plot these waypoints using satellite imagery from the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, which has been mapping Mars since 2006, combined with high-resolution images from Perseverance's own cameras, as explained in MDPI's detailed analysis.

But creating this breadcrumb trail is painstaking work. Engineers have to consider dozens of factors. Will the rover slide on loose dust? Could it tip over on a slope steeper than 30 degrees? Are there rocks that would catch on the rover's undercarriage? Could the wheels spin uselessly on fine sand? Is there a cliff hidden just beyond the next dune that the satellite imagery didn't reveal clearly?

"Every rover drive needs to be carefully planned, lest the machine slide, tip, spin its wheels, or get beached," NASA explained. "So ever since the rover landed, its human operators have painstakingly laid out waypoints—they call it a 'breadcrumb trail'—for it to follow, using a combination of images taken from space and the rover's onboard cameras."

Prior to December 2024, this entire process was manual. A team of engineers would spend hours studying maps, cross-referencing satellite data with ground-level imagery, and carefully marking waypoints that represent not just a direction the rover should go, but a series of safe-ish spots where the rover can pause, recalibrate its position, and wait for the next set of commands from Earth.

Why AI Was the Logical Next Step

So why did NASA decide to experiment with Claude? The answer comes down to efficiency, consistency, and the fact that route-planning is, at its core, a task that an AI should theoretically excel at.

Route-planning combines several types of reasoning that large language models are good at. It requires understanding spatial relationships, analyzing available data (the satellite imagery and rover camera feeds), identifying potential hazards, generating a sequence of safe actions, and then critiquing and iterating on those actions. These are all things that Claude and other LLMs can do reasonably well, at least in principle.

But there's a catch. Claude didn't just magically understand Mars rover navigation. NASA had to teach it.

To give Claude enough context to understand the task, NASA's team provided the model with "years" of contextual data from the rover's operations. This included historical rover drives, examples of successful and unsuccessful route plans, data about terrain conditions, specifications for the rover's capabilities and limitations, and guidelines for safe navigation on Mars, as detailed in NASA's mission documentation.

Think of it like teaching a human rover driver. You wouldn't just show them a map and say "go." You'd give them weeks of training about the rover's strengths and weaknesses, show them examples of routes that worked well and routes that went badly, and teach them the principles of safe navigation on Mars.

In Claude's case, NASA uploaded all this historical data and contextual information into Claude Code, Anthropic's programming agent. Claude Code isn't just Claude the chatbot. It's Claude with the ability to write and execute code, analyze complex data structures, and work through problems methodically.

Using Claude Code reduces rover route-planning time by 50%, from 8 hours to 4 hours, allowing for more efficient data collection and analysis. Estimated data based on NASA's reports.

How Claude Approached the Route-Planning Task

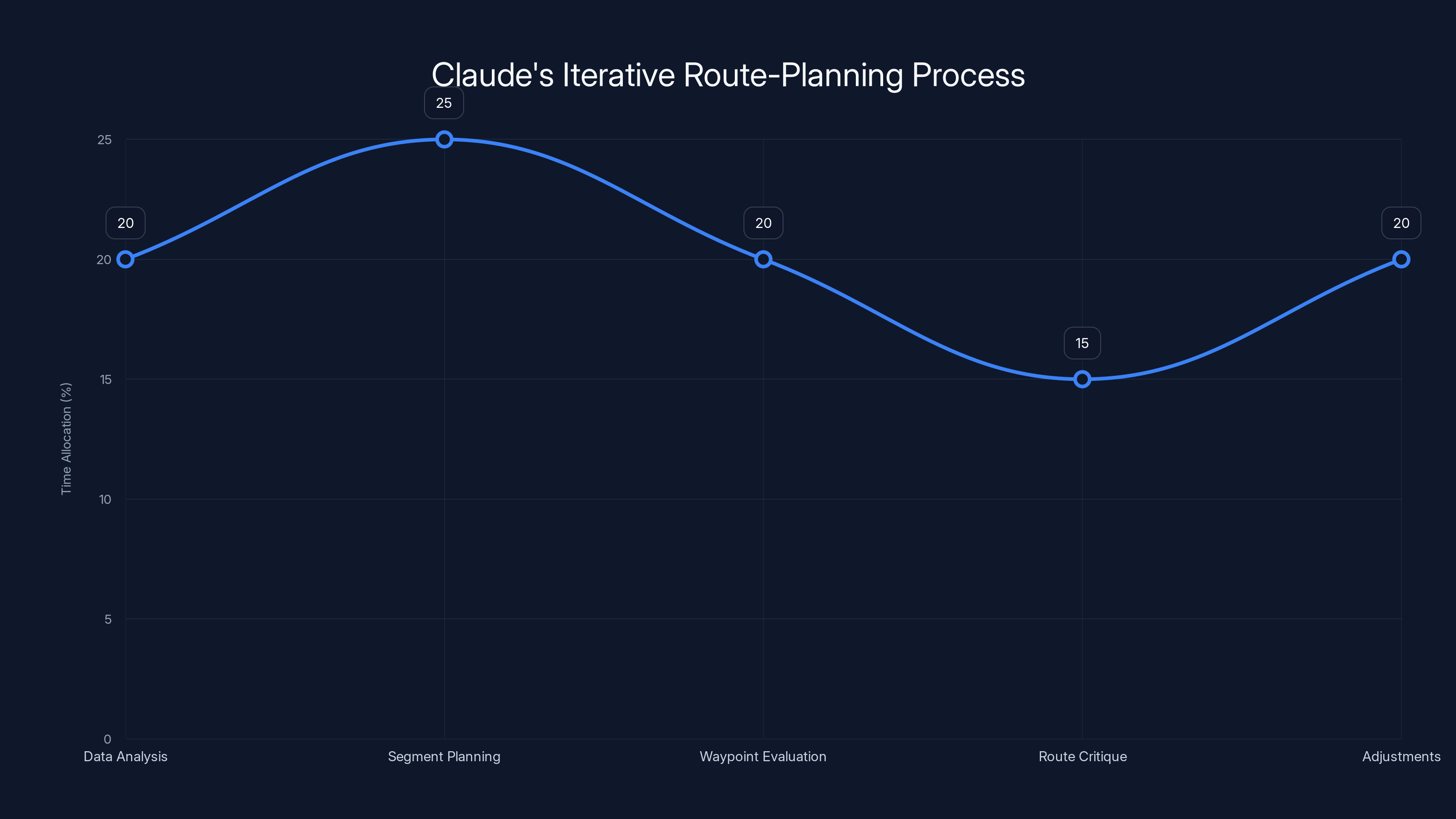

NASA described Claude's methodology in a way that's surprisingly methodical and cautious. The model didn't just generate a route and call it done. Instead, it worked through the problem step-by-step.

Claude started by analyzing the available data. It looked at satellite imagery of the Jezero Crater section that Perseverance needed to traverse. It reviewed the rover's onboard camera feeds to understand ground-level conditions. It studied the terrain hazards that engineers had previously identified. It reviewed its historical training data about what constituted a safe waypoint versus a hazardous path.

Then Claude did something smart: it broke the route into manageable segments. Rather than trying to plan a single continuous 400-meter path, Claude worked with ten-meter segments. For each segment, Claude would plot a waypoint, consider whether that waypoint was safe given the terrain and rover capabilities, and then move on to the next segment.

But Claude didn't just move forward blindly. The model built in a critique mechanism. After generating a proposed route, Claude would review it, check for potential issues, consider whether the waypoints made sense given the available imagery, and then iterate. If Claude spotted a potential problem, it would adjust the route.

This iterative approach is important because it mirrors how human engineers work. A human wouldn't plot a complex route once and assume it's perfect. They'd generate a draft, review it, critique it, make adjustments, and then review it again. Claude approached the problem the same way.

The Verification Process: When AI Meets Human Skepticism

Here's where NASA showed some smart caution. They didn't just upload Claude's route directly to Perseverance and say "go forth and explore." Instead, they ran Claude's waypoints through a rigorous verification process.

Engineers from NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory took Claude's proposed route and fed it into a detailed simulation of Perseverance's navigation systems. This simulation is the same one that engineers use every single day to verify routes before they're uploaded to the rover. The simulation accounts for the rover's weight distribution, suspension characteristics, wheel traction profiles, and dozens of other physical parameters.

In the simulation, they ran through the entire route. Does the rover successfully navigate all the waypoints without getting stuck? Does it maintain traction on the slopes Claude suggested? Are the turns too sharp for the rover's turning radius? Would the rover's belly scrape on rocks along the proposed path?

When the simulation was complete, the engineers examined Claude's work closely. They found that the route was solid. In fact, they only had to make minor adjustments. One change came because the engineering team had access to ground-level images that Claude hadn't seen during the route-planning process. Another small adjustment came from applying some additional conservative safety margins, as highlighted in NASA's detailed report.

But by and large, Claude's route was good. Good enough that a rover on Mars followed it successfully. Good enough that a car-sized robot 238 million miles away trusted the navigation plan generated by a large language model.

The Efficiency Breakthrough: Half the Time, Better Consistency

So here's the key finding from this experiment: NASA estimates that using Claude cut the route-planning time in half.

Think about what that means. Previously, experienced engineers would spend hours planning a single rover drive. With Claude's help, NASA can now generate a viable route plan in roughly half the time. That's not a marginal improvement. That's a fundamental shift in how productive the rover operations team can be.

NASA also noted that the routes generated with Claude's help were more consistent. When human planners are working under time pressure or fatigue, consistency can slip. Routes might take slightly different approaches. Safety margins might vary. Claude, being an AI, doesn't get tired, doesn't get distracted, and doesn't let small variations creep into its decision-making framework.

NASA's statement about the impact is worth reading carefully: "The engineers estimate that using Claude in this way will cut the route-planning time in half, and make the journeys more consistent. Less time spent doing tedious manual planning—and less time spent training—allows the rover's operators to fit in even more drives, collect even more scientific data, and do even more analysis. It means, in short, that we'll learn much more about Mars," as noted in NASA's official statement.

This is huge. Because every hour of human engineering time saved is an hour that can be spent on actual science. It's an hour that can be spent analyzing the data that Perseverance collects, planning new scientific objectives, or training the next generation of engineers.

For a rover that's been operating for nearly five years past its original two-year mission design, every bit of operational efficiency counts. The rover is aging. Its wheels are worn. Its radioisotope thermoelectric generator, which provides power and heat, is declining. Every extra drive, every extra sample collected, is a precious win.

Mars rover route-planning is complex due to factors like communication delays and terrain analysis, with terrain analysis being the most challenging. Estimated data.

The Broader Context: AI and NASA's Efficiency Crisis

Now, you might be thinking: okay, this is cool, but why does it matter so much? It's just a rover. It's just route-planning.

The reason it matters becomes clear when you understand NASA's current situation. The agency is facing unprecedented pressure. Over the summer of 2024, NASA lost about 4,000 employees, accounting for approximately 20 percent of its total workforce, due to federal budget cuts. That's not a small reduction. That's removing one out of every five people from the organization, as reported by AirGuide.

Even after Congress rejected the Trump administration's proposed cuts to NASA's science budget in early January 2025, the agency is facing severe constraints. It's being asked to return to the Moon with less than half the workforce that existed during the height of the Apollo program. Think about that for a moment. The Apollo program, at its peak, employed over 400,000 people. NASA is now being asked to accomplish the same feat with roughly 18,000 people.

In this context, any tool that can make the remaining workforce more efficient is valuable. If Claude can cut route-planning time in half, that's a meaningful contribution to the agency's ability to maintain its space exploration programs. It's one less bottleneck in a process that's already under strain.

That's why this experiment is significant beyond just being "cool AI news." It's a demonstration that AI can contribute to solving real problems in space exploration, particularly problems related to efficiency and resource optimization.

Claude's Journey: From Game-Playing Struggles to Mars Navigation

There's something almost poetic about Claude's trajectory. Just a year earlier, in spring 2023, Claude was struggling to beat Pokémon Red on the Game Boy. Pokémon Red is an 8-bit game from 1996. It's not exactly a showcase of modern artificial intelligence.

Yet within less than a year, Claude had evolved from struggling with a simple video game to successfully plotting a route for a rover on Mars. That's not just progress. That's a fundamental demonstration of how rapidly large language models are improving.

The Pokémon Red failure was instructive, actually. It showed that Claude, despite being a powerful language model, struggled with certain types of tasks that required real-time navigation, spatial reasoning, and immediate consequences for mistakes. The game required Claude to navigate terrain, manage resources, and make decisions in a dynamic environment.

Mars rover route-planning requires similar spatial reasoning, but without the time pressure and without the immediate failure states. Claude has time to think through the problem. Claude can iterate and refine. Claude can critique its own work before submitting the final answer.

In this context, Claude's success on Mars makes sense. It's not that Claude became much smarter in a year. It's that NASA structured the problem in a way that plays to Claude's strengths: careful analysis, iterative refinement, and methodical reasoning.

The Technical Requirements: More Than Just Prompting

Now let's talk about what it actually took to make this work, because this is where many people get confused about AI capabilities.

Some people might think NASA just wrote a prompt like "Hey Claude, here's a picture of Mars, plan a route." That's not what happened at all.

Instead, NASA had to provide Claude Code with years of training data. They had to create structured data representations of terrain features. They had to encode the rover's specifications and capabilities. They had to provide examples of successful and failed routes. They had to establish safety criteria and constraints.

Basically, NASA did something similar to what you'd do if you were training a human rover driver. You wouldn't just give them a picture and say "drive." You'd spend months teaching them about the terrain, the rover, the risks, and the protocols, as detailed in NASA's mission documentation.

This is an important point because it shows that using AI for specialized tasks like Mars rover navigation isn't as simple as it might seem. It requires domain expertise, careful data preparation, and iterative refinement. You can't just throw any large language model at a complex problem and expect great results.

Claude Code specifically was important here because it allowed Claude to write and execute code to analyze the data. A regular language model might struggle with the quantitative aspects of route-planning. But with the ability to write code, Claude can perform calculations, analyze data structures, and verify its own logic.

Using Claude has reduced the rover route-planning time by 50%, significantly enhancing operational efficiency. Estimated data.

The Safety Implications: Learning to Trust AI in Critical Systems

There's a deeper question lurking here: How do you decide when to trust an AI system with critical decisions?

Perseverance is a billion-dollar asset. It's the flagship rover of Mars 2020, one of NASA's most important active missions. A route-planning failure could result in the rover getting stuck, damaging critical systems, or being rendered inoperable. This isn't a low-stakes domain where you can learn by failing.

Yet NASA decided to let Claude plan a route. How did they justify that risk?

The answer lies in the verification process. NASA didn't just trust Claude blindly. They built in multiple layers of verification. They ran Claude's route through simulations. They reviewed it manually. They only deployed it after confirming it would work. And they started with a relatively short, simple drive—400 meters through terrain that had been thoroughly studied—rather than asking Claude to plan a risky cross-country journey, as highlighted in Sky at Night Magazine.

This is a model that's probably applicable to many critical systems. You don't immediately deploy AI in high-stakes environments. You build verification processes. You start with low-risk applications. You gradually expand the scope as you build confidence. You maintain human oversight at critical decision points.

In NASA's case, humans reviewed and modified Claude's route before it was sent to the rover. That human-in-the-loop approach is crucial. The AI did the tedious work of generating a detailed route. The humans applied domain expertise and made final decisions.

The Implications for Future Space Exploration

So what does this mean for the future of space exploration? NASA wasn't shy about suggesting the implications.

The agency stated that "autonomous AI systems could help probes explore ever more distant parts of the solar system." That's a pretty straightforward prediction. As we send probes to more distant, harder-to-explore locations, the time delay increases. A probe to the outer solar system might have a one-hour or even longer communication delay. In that context, having autonomous AI systems that can make navigation decisions without waiting for human input becomes essential.

Imagine a probe to Enceladus, Saturn's icy moon. The communication delay is 80 minutes one way. You can't have the probe constantly asking Earth permission to drive 10 meters forward. Instead, you'd need the probe to be somewhat autonomous. It would need to make decisions about where it's safe to go, what hazards exist, and how to navigate around them.

Claude's success at Mars route-planning suggests that large language models could potentially be part of the solution. They could serve as the decision-making engine for autonomous exploration systems. In combination with other AI techniques (like computer vision for hazard detection and classical robotics algorithms for motion planning), LLMs could help future probes explore the solar system more autonomously.

There's also the question of how this scales to human exploration. Eventually, NASA wants to return humans to the Moon and send humans to Mars. Human explorers will need vehicles to traverse terrain. Those vehicles will need routes planned. In a human mission context, route-planning might be done by the astronauts themselves, but AI assistance could speed up the process and provide additional safety validation.

Anthropic's Achievement and What It Says About AI Progress

For Anthropic, this is a major achievement in the company's portfolio. Claude's capabilities have improved dramatically over the past year, and this Mars rover route-planning task is a visible demonstration of that improvement.

Last year, Claude was known primarily as a capable general-purpose language model. It was good at writing, coding, analysis, and reasoning. But it was operating in the realm of text and code, domains where large language models were already known to be powerful.

This Mars task demonstrates Claude's ability to operate in a specialized domain that requires deep domain knowledge, spatial reasoning, and practical problem-solving. It's a proof point that Claude can be useful not just as a general assistant, but as a tool for solving real-world problems in specialized fields.

For Anthropic, that's valuable. It suggests that Claude could potentially be useful in other specialized domains: drug discovery, materials science, chip design, architecture, engineering, and countless other fields where deep reasoning combined with access to domain-specific data could be valuable.

It also demonstrates that Anthropic is thinking seriously about how to make Claude useful for real-world problems beyond text generation and coding. The fact that they built Claude Code, which gives Claude the ability to write and execute code, shows they understand that pure language understanding isn't enough. The ability to execute, iterate, and refine is equally important.

AI-assisted planning reduced route planning time by 50% and increased efficiency by 20%, highlighting the transformative impact of AI on space exploration (Estimated data).

The Challenges That Remain

Now let's be honest about the limitations. This Mars rover route-planning task was designed in a way that plays to Claude's strengths. It's not a universal demonstration of AI capability.

Claude didn't have to make decisions with incomplete information. NASA provided all the terrain data. Claude didn't have to handle unexpected situations. The rover followed the pre-planned route in controlled conditions. Claude didn't have to learn in real-time. It had historical training data to draw from.

These are all things that human rover drivers would need to do. If a human were driving Perseverance, they'd be making real-time decisions based on what they could see, adapting to unexpected hazards, responding to new information. Claude didn't do any of that.

That's not a criticism. It's just an acknowledgment that this task was carefully constrained to be solvable by current AI technology. The real work of space exploration involves handling situations outside the training set, making decisions with incomplete information, and adapting to unexpected challenges.

Furthermore, this was a single demonstration. Claude did one drive successfully. That's valuable, but it's not yet a track record of sustained reliable performance. What happens if Claude is asked to plan 100 routes in a row? Do errors accumulate? Do edge cases emerge that weren't visible in the first trial?

Those are questions that will take time and continued experimentation to answer.

What This Means for Your Industry

If you're not in space exploration, you might be wondering: why should I care?

The reason is that this kind of thinking—using large language models for specialized domain tasks, combining AI with careful verification processes, and using AI to improve human efficiency—is applicable across almost every industry.

If you're in logistics, Claude could help plan delivery routes, optimize vehicle utilization, and identify potential efficiency improvements. If you're in manufacturing, Claude could help plan production workflows, identify quality control issues, and optimize resource allocation. If you're in healthcare, Claude could help analyze patient data, suggest treatment approaches, and identify potential complications.

The Mars rover case is just the first highly visible example of AI being used for specialized technical reasoning. It won't be the last.

The Economic Question: Is AI Route-Planning Worth It?

Let's talk practical economics for a moment. Is it actually worth it for NASA to use Claude for route-planning?

The obvious benefit is time savings. If Claude cuts route-planning time in half, that's a significant efficiency gain. Let's do some rough math.

If a human engineer currently spends 8 hours planning a rover drive, and Claude can do it in 4 hours with verification, NASA saves 4 hours per drive. Perseverance does maybe 5-10 drives per week (depending on various factors). That's 20-40 hours per week of engineer time that could be allocated to other work.

Over a year, that could free up 1,000-2,000 hours of engineering capacity. At a typical NASA engineer salary (let's say $150,000 annually), that's equivalent to saving the salary of one junior engineer.

Now, you have to account for the cost of using Claude. Anthropic charges for API access. As of early 2025, Claude's pricing is in the range of

In other words, the cost of using Claude is negligible compared to the human engineer time saved. NASA saves potentially thousands of dollars per month by using Claude, and gets more scientist time and rover drives as a result.

That's not a groundbreaking economic story. It's just straightforward productivity improvement. But in an era when NASA is cutting 20 percent of its workforce, straightforward productivity improvements matter.

Claude's route-planning process involves iterative steps with significant time spent on segment planning and adjustments. Estimated data.

Looking Forward: The Next Frontiers for AI in Space Exploration

NASA has made it clear that this Mars rover experiment is just the beginning. The agency is thinking about how autonomous AI systems could help with many aspects of space exploration.

One area is autonomous hazard detection. Right now, rovers have cameras and sensors that feed data back to Earth. Engineers on Earth analyze that data to identify hazards. But what if the rover could analyze its own sensor data in real-time? What if Claude or a similar system could look at terrain imagery and identify rocks, cliffs, and patches of loose sand that would be hazardous? That could enable rovers to make more autonomous decisions about where to drive, without waiting for input from Earth.

Another area is scientific discovery. Right now, rovers collect data and scientists on Earth analyze it. But what if the rover could do preliminary analysis itself? What if Claude could look at spectroscopy data and identify which rocks are most scientifically interesting? That could help prioritize the rover's activities and maximize the scientific return of the mission.

Yet another area is long-duration mission planning. Future missions to Mars might involve rovers that need to operate for years with minimal human oversight. Those rovers would need to be more autonomous. They'd need to plan their own scientific campaigns, manage their own power, and make decisions about survival and mission priorities. Large language models could potentially help with the reasoning and planning aspects of those challenges.

None of this will be easy. But the path forward is becoming clearer. NASA is using AI where it's good at specific, well-defined tasks. The agency is building verification processes. It's combining AI with human expertise. And it's gradually pushing the boundaries of what's possible.

The Broader Implications for Human-AI Collaboration

There's a deeper lesson here about how humans and AI can work together effectively.

The Mars rover case isn't an example of AI replacing humans. It's an example of AI augmenting human capability. NASA still has the same number of route-planning engineers. Those engineers are just spending less time on tedious waypoint generation and more time on the higher-value work of analyzing science data and planning future missions.

That's the model that seems to be emerging across industries. AI isn't primarily replacing specialists. It's taking over the tedious parts of specialist work, freeing the specialist to do more interesting, higher-value work.

A radiologist doesn't stop being a radiologist if you give them an AI that can analyze scans. Instead, the radiologist becomes more productive. They can analyze more scans, spend more time on complex edge cases, and focus on patient outcomes rather than image interpretation. Similarly, a NASA engineer doesn't stop being a rover operator if you give them an AI route planner. They become more productive and get to focus on science rather than manual planning.

This has implications for education and career planning. If routine expert work is being automated, then training the next generation of experts needs to focus even more on the thinking skills, the judgment, the creativity, and the ability to work with AI systems. A future NASA engineer will need to be good at route-planning, but they'll also need to be good at evaluating AI route plans, catching errors, and improving on AI suggestions.

Remaining Questions and Open Problems

As impressive as this achievement is, there are still many open questions about using AI in space exploration.

How do you handle distribution shift? Claude was trained on data from past rover operations. What happens when the rover explores terrain that's significantly different from what was in the training data? How gracefully does Claude degrade? Does it become overconfident, or does it flag when it's outside its domain of expertise?

How do you handle novel situations? Part of good route-planning is recognizing when something unexpected has happened and adapting. Can Claude do that? Or does it require human intervention?

How do you build redundancy and resilience? In critical systems, you don't want to depend on a single AI model. What happens if Claude makes an error that slips past verification? How do you architect systems so that a single AI failure doesn't cascade into mission failure?

What about interpretability? When Claude generates a route, why does it choose one path over another? Can the system explain its reasoning in a way that engineers can understand and verify? Or is it a black box that produces answers that humans can validate but not understand?

These are deep questions that the AI and space exploration communities will need to answer as we move forward.

The Bigger Picture: AI's Role in Human Exploration

Ultimately, this Mars rover story is just one chapter in a much larger story about how AI is going to shape human exploration of the solar system.

We're going to need AI for so many things in space exploration. We'll need it for autonomous navigation when communication delays make real-time control impossible. We'll need it for scientific analysis, to help rovers identify the most interesting samples to collect. We'll need it for mission planning, to help humans and robots make good decisions about where to go and what to do. We'll need it for equipment maintenance, to help diagnose problems in complex systems.

But we're not going to replace human expertise. If anything, space exploration is going to require more expertise, more judgment, and more creativity. We'll need humans to supervise AI systems, to catch errors, to handle unexpected situations, and to make the ultimate decisions about mission priorities.

The NASA rover case is a small example of that collaboration. Claude did the tedious work. Humans did the verification and decision-making. The result was better than either could achieve alone.

As we push further into the solar system, as we attempt more ambitious missions, that kind of collaboration is going to become even more important. The future of space exploration isn't about AI replacing humans. It's about AI and humans working together, each doing what they do best.

NASA has shown us that this is possible. The question now is how quickly and how extensively we can make it real.

FAQ

What is Claude Code and why did NASA use it for route-planning?

Claude Code is Anthropic's programming agent that allows Claude, their large language model, to write and execute code while working on complex problems. NASA used Claude Code specifically because route-planning requires not just language understanding but also the ability to analyze terrain data, perform calculations, and iterate through solutions systematically. The code execution capability allowed Claude to process the years of rover operational data and terrain imagery that NASA provided, then generate and refine waypoints based on that analysis.

How much faster is route-planning with Claude compared to manual methods?

NASA estimates that using Claude to plan rover routes cuts the planning time approximately in half compared to the previous manual approach. This means that what previously took human engineers around 8 hours now takes roughly 4 hours including the verification and adjustment process. This time savings translates directly into more rover drives per week, which means more scientific data collection and more time for engineers to focus on analysis rather than tedious manual planning tasks.

Did Claude completely replace human rover planners, or do humans still review the routes?

Humans absolutely still review and validate Claude's work. When Claude generates a proposed route, NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory engineers run it through detailed simulations before it's ever uploaded to the rover. Engineers can verify every waypoint, check turning radiuses, ensure traction calculations, and confirm safety margins. In the December 2024 route, engineers only needed to make minor adjustments—some based on ground-level imagery Claude hadn't seen during planning. This human-in-the-loop approach ensures that AI-generated routes meet NASA's extremely high safety standards before being deployed on an expensive rover millions of miles away.

What specific data did NASA provide to Claude to make this task possible?

NASA provided Claude with years of historical context about Perseverance's operations, including past successful and unsuccessful route plans, detailed technical specifications about the rover's capabilities and limitations, terrain feature classifications, hazard identification guidelines, satellite imagery from the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, high-resolution ground-level images from Perseverance's cameras, and comprehensive documentation about safe navigational practices on Mars terrain. This training data essentially taught Claude the principles of Mars rover navigation before asking it to plan an actual route—similar to how you'd train a human driver with weeks of instruction before giving them the keys.

Could Claude's route-planning approach work for rovers on other planets or moons?

Yes, the methodology should theoretically work for rovers on any terrain where you have sufficient imaging data and historical navigation examples. The approach would likely work well on the Moon, where similar imaging assets exist and we have decades of rover operation data. It could potentially work on Venus or Titan, though the extreme environmental conditions would require different training data and safety parameters. The key requirement is having sufficient terrain imagery, enough historical examples of safe navigation, and clear specifications for the vehicle being navigated. As we send more rovers to different locations in the solar system, AI route-planning could become increasingly valuable because the communication delays make real-time human control impossible.

How does Claude know what counts as a safe waypoint versus a hazardous path on Mars?

Claude learned this through the training data NASA provided—examples of routes that succeeded and routes that failed, along with analysis of why each succeeded or failed. The model was given specifications about the rover's weight distribution, suspension characteristics, wheel traction profiles, maximum traversable slope (around 30 degrees), and clearance beneath the rover's belly. Claude also received information about terrain features—rock types, dust composition, cliff characteristics—and how those features affect drivability. When planning waypoints, Claude applies this learned knowledge to evaluate terrain in new locations, checking whether the proposed path matches the safety criteria it learned from historical examples.

What happens if Claude encounters terrain conditions in a future drive that are completely different from its training data?

That's an important open question that will likely require continued experimentation to answer fully. In theory, Claude should be able to recognize when it's outside its domain of expertise and either flag uncertainty or fall back to more conservative decision-making. However, one of the known challenges with large language models is ensuring they don't become overconfident when facing novel situations. This is why NASA maintains human oversight and verification. If Claude encounters genuinely novel terrain, engineers would likely need to review the route more carefully and might revert to more manual planning for that specific drive until they understand the new conditions better. Over time, as Claude gains experience with more diverse terrain, it would theoretically become better at handling edge cases.

What are the cost implications of using Claude compared to the time it saves?

The cost-benefit analysis strongly favors using Claude. While Anthropic charges for API access (typically in the range of a few dollars per route plan when optimized for efficient token usage), the human engineer time saved far exceeds this cost. If one route plan saves 4 hours of engineer time and NASA does 5-10 drives per week, the cost is trivial compared to the engineer time freed up. That freed-up time translates not just to salary savings but to more rover drives and more scientific discovery, which is the actual mission objective. From a pure economics standpoint, this is straightforward productivity improvement where the AI tool is so much cheaper than the human labor it replaces that the ROI is obvious.

Could AI route-planning eventually make human rover operators obsolete?

Unlikely, at least not in the foreseeable future. What's more probable is that the role evolves. Instead of spending most of their time on manual waypoint generation, rover operators will spend more time on mission planning, scientific decision-making, and supervising AI systems. They'll handle exceptions and unexpected situations. They'll review AI-generated plans for quality and feasibility. As rovers become more autonomous due to longer communication delays with more distant destinations, operators might shift from real-time drivers to strategic planners and supervisors. The pattern we're seeing across industries is that AI tends to enhance specialist roles rather than eliminate them—the specialists just do more interesting, higher-value work.

Conclusion: The Convergence of AI and Space Exploration

We've reached a moment where two historically separate fields are starting to converge in interesting ways. Space exploration, with its requirements for autonomous decision-making and handling of incomplete information, is becoming an increasingly important testing ground for large language models. Simultaneously, AI systems are becoming more capable of handling the kind of specialized domain reasoning that space exploration requires.

NASA's December 2024 experiment with Claude represents more than just a clever use of a chatbot. It represents a demonstration that the collaboration between humans and AI can improve outcomes in high-stakes environments where failure is expensive and expertise is scarce.

For Anthropic, this is a validation that Claude can be useful far beyond the domains where language models first proved their value. The company has evolved from a model that was good at text generation to a system that can engage in specialized technical reasoning, apply domain knowledge, and produce actionable real-world results.

For NASA, this is a potential solution to real operational challenges. With the agency facing 20 percent workforce cuts and being asked to accomplish more ambitious missions with fewer people, tools that multiply the effectiveness of those remaining people are valuable. Claude helped NASA get more rover drives per week without increasing the engineering team. That's the kind of efficiency gain that could be the difference between mission success and mission failure as budgets tighten.

For the broader space exploration community, this experiment suggests a path forward for future missions to more distant locations. As we send probes to the outer solar system, the communication delays become prohibitive for real-time control. Those probes will need to be more autonomous. Large language models, combined with other AI techniques, could provide the reasoning engine for that autonomy.

But perhaps most importantly, this Mars rover case study offers a lesson about how human expertise and AI capability can work together. This isn't a story about AI replacing humans. It's a story about AI augmenting humans, multiplying their effectiveness, and freeing them to do more interesting work.

As we move forward, that collaboration is going to become increasingly important. The future of space exploration, like the future of most fields, won't be humans alone or AI alone. It will be humans and AI working together, each doing what they do best, pushing the boundaries of what's possible in the exploration of our solar system.

Key Takeaways

- NASA successfully used Claude Code to plan a 400-meter rover route through Mars' Jezero Crater in December 2024, marking the first time an LLM navigated a rover on another planet.

- Claude reduced route-planning time by approximately 50 percent, from 8 hours to 4 hours per drive, freeing engineer time for more critical scientific work.

- The approach required providing Claude with years of historical rover operations data, terrain specifications, and safety guidelines before autonomous planning was possible.

- JPL engineers verified Claude's route through rigorous simulation before deployment, demonstrating the critical importance of human oversight in high-stakes AI applications.

- As communication delays increase with more distant missions (80+ minutes to outer solar system), autonomous AI systems like Claude become increasingly essential for future space exploration.

Related Articles

- Arcee's Trinity Large: Open-Source AI Model Revolution [2025]

- NASA's Mars Orbiter Decision: What's at Stake [2025]

- Declassified JUMPSEAT Spy Satellites: Cold War Signals Intelligence Revealed [2025]

- AI Chatbots & User Disempowerment: How Often Do They Cause Real Harm? [2025]

- SpaceX and xAI Merger: What It Means for AI and Space [2025]

- Flapping Airplanes and Research-Driven AI: Why Data-Hungry Models Are Becoming Obsolete [2025]

![NASA Used Claude to Plot Perseverance's Mars Route [2025]](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/rN1tj2lvHYCB3QtqUZbJhg--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTEyMDA7aD02NzU-/https://d29szjachogqwa.cloudfront.net/images/user-uploaded/claude-nasa.jpg)