Introduction: A Seismic Shift in Space Exploration Strategy

For decades, getting to deep space has been an exclusively governmental affair. Launch your rockets, build your spacecraft, and do the work yourself. That's been the NASA playbook since President Kennedy's moonshot promise in 1961. But something fundamental shifted on Wednesday when a House committee unanimously passed what might seem like bureaucratic fine print: Amendment No. 01 to the NASA reauthorization act.

On the surface, it's just language. "The Administrator may, subject to appropriations, procure from United States commercial providers operational services to carry cargo and crew safely, reliably, and affordably to and from deep space destinations, including the Moon and Mars." Read that again. It doesn't sound revolutionary. It sounds like paperwork.

But this amendment represents something that space advocates have been pushing for years: formal congressional permission for NASA to let private companies compete for deep space missions. Not just low Earth orbit. Not just cargo runs to the International Space Station. Moon missions. Mars missions. The really ambitious stuff.

Why does this matter? Because the commercial space industry has spent the last decade proving it can do things faster, cheaper, and more reliably than traditional government contractors. SpaceX lands reusable rockets. Blue Origin is building New Glenn. Emerging companies like Impulse Space are innovating propulsion. Congress is essentially telling NASA: we see what you're doing, we're impressed, and we want you to let these companies bid on the hardest problems we've got.

This isn't the end of the Artemis program as we know it. The Space Launch System, Orion spacecraft, and the government-mandated lunar lander architecture remain locked in for the first five missions. But after that? Everything changes. NASA gets flexibility. The private sector gets opportunity. And America might get a more sustainable, affordable deep space exploration program.

Here's what you need to know about why this amendment matters, what it actually allows, who's positioned to benefit, and what happens next.

TL; DR

- Congressional Approval: A House committee unanimously passed Amendment No. 01, allowing NASA to procure deep space transportation from commercial providers for Moon and Mars missions after Artemis V

- Breaking the SLS Lock: While Artemis I-V remain bound to the Space Launch System and Orion, future missions can use alternative architectures from SpaceX, Blue Origin, and other companies

- Industry Position: The Commercial Spaceflight Federation hailed the amendment as a "step in the right direction," aligning with the current administration's focus on commercial competition

- Implementation Path: If passed by the full House and Senate, NASA could establish a new program office with requirements and contracting mechanisms similar to Commercial Crew Program partnerships

- Bottom Line: Congress is formally authorizing NASA to embrace competition in deep space, potentially reducing costs and accelerating lunar and Mars exploration timelines

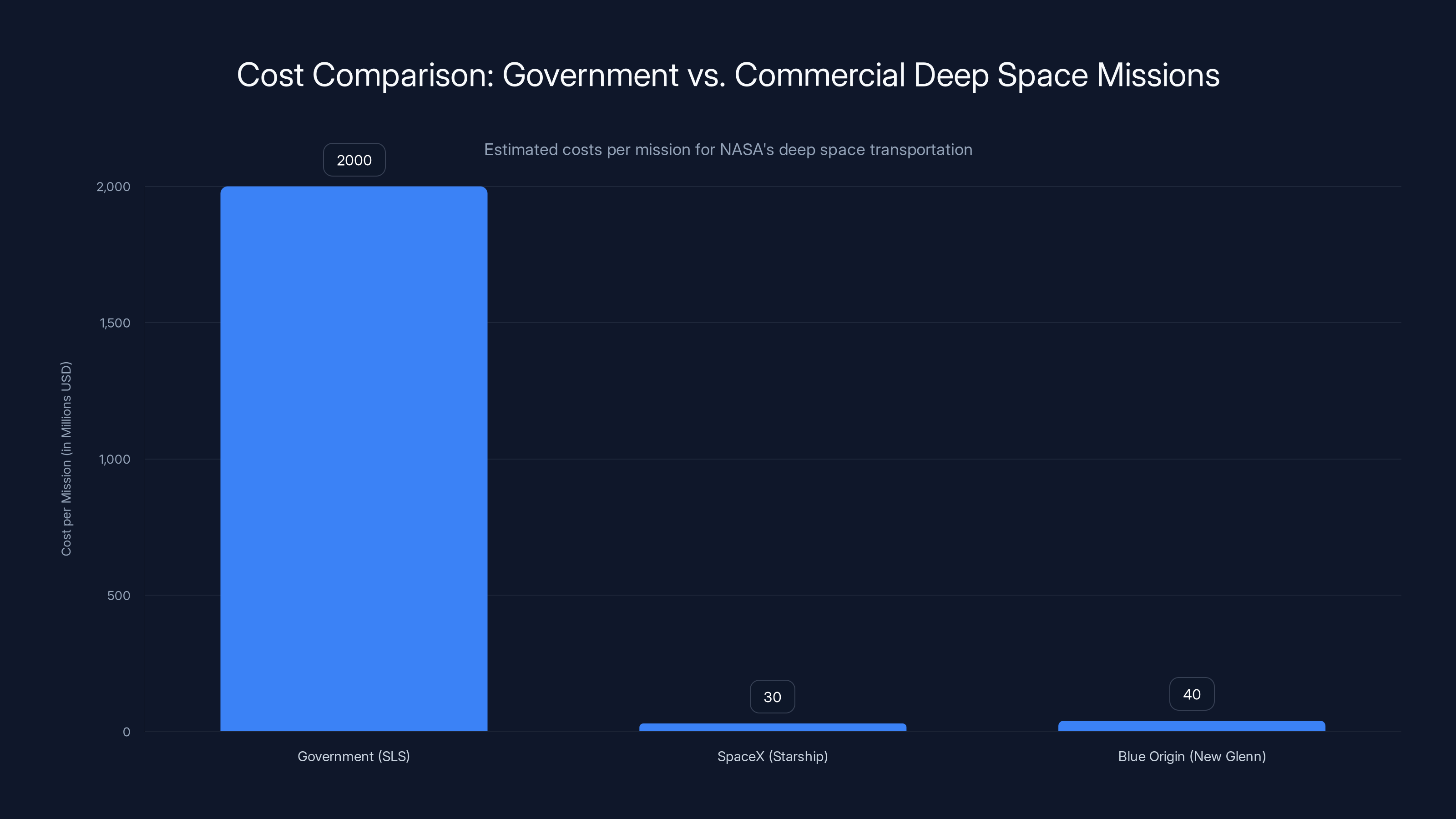

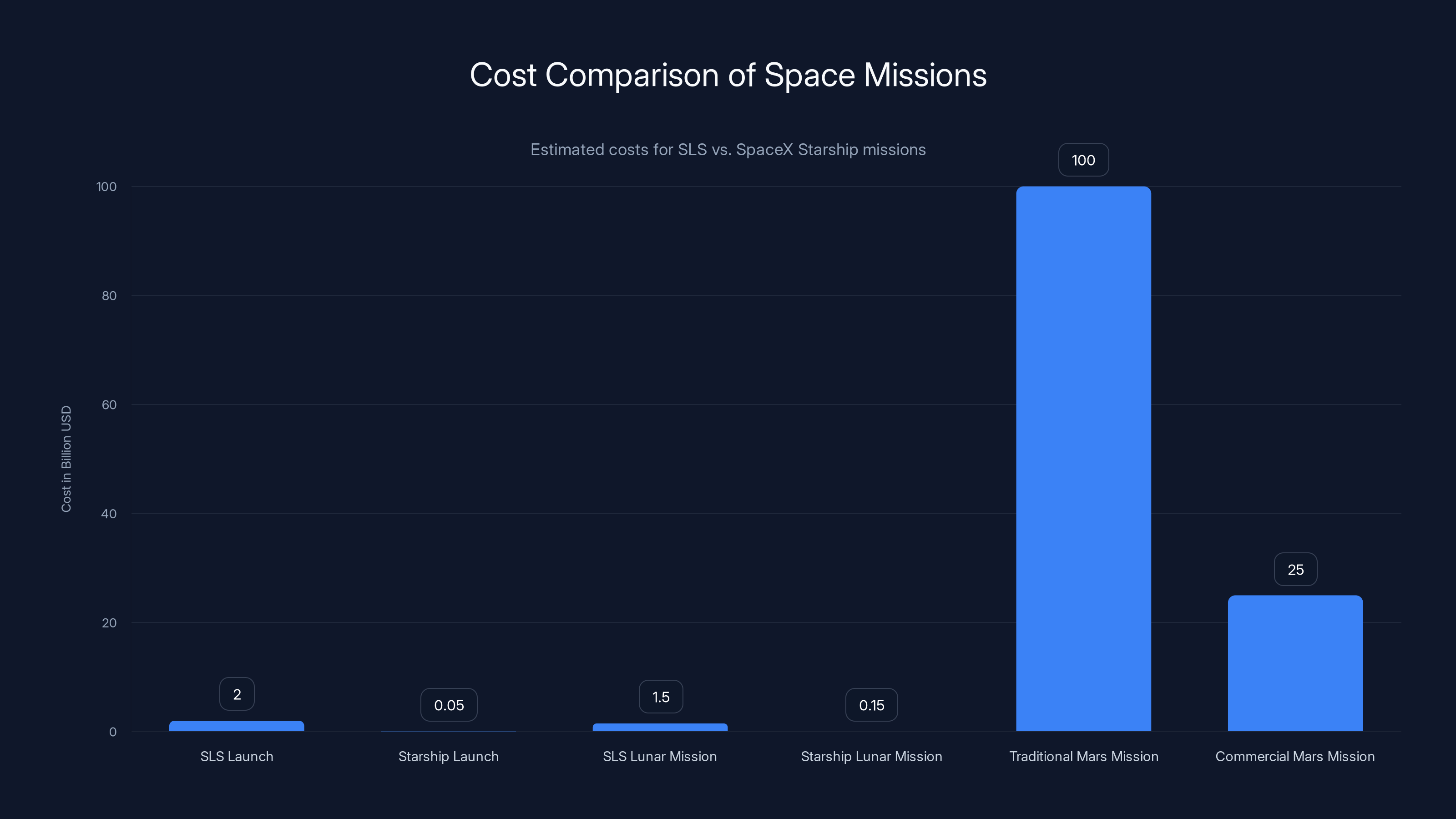

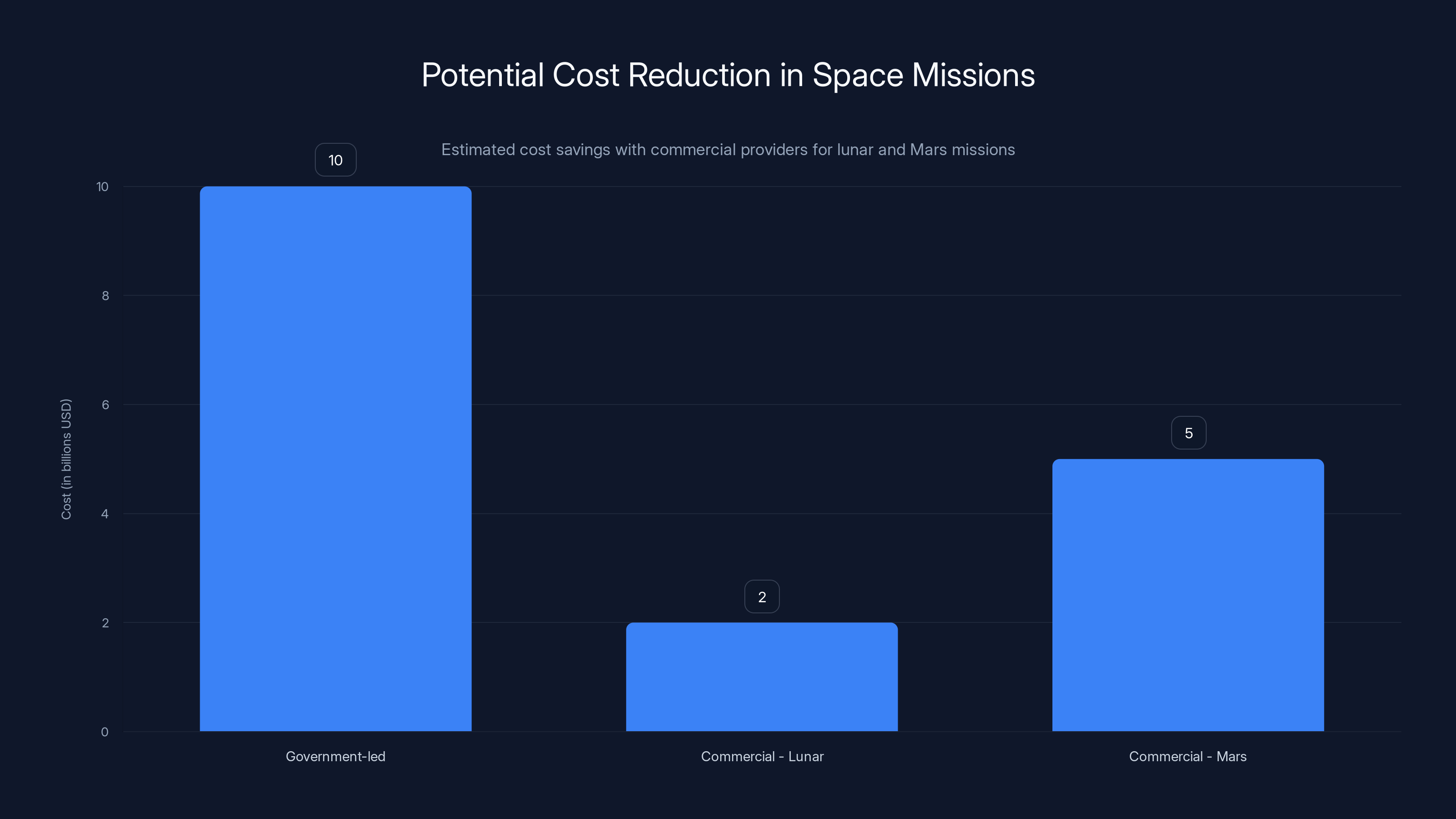

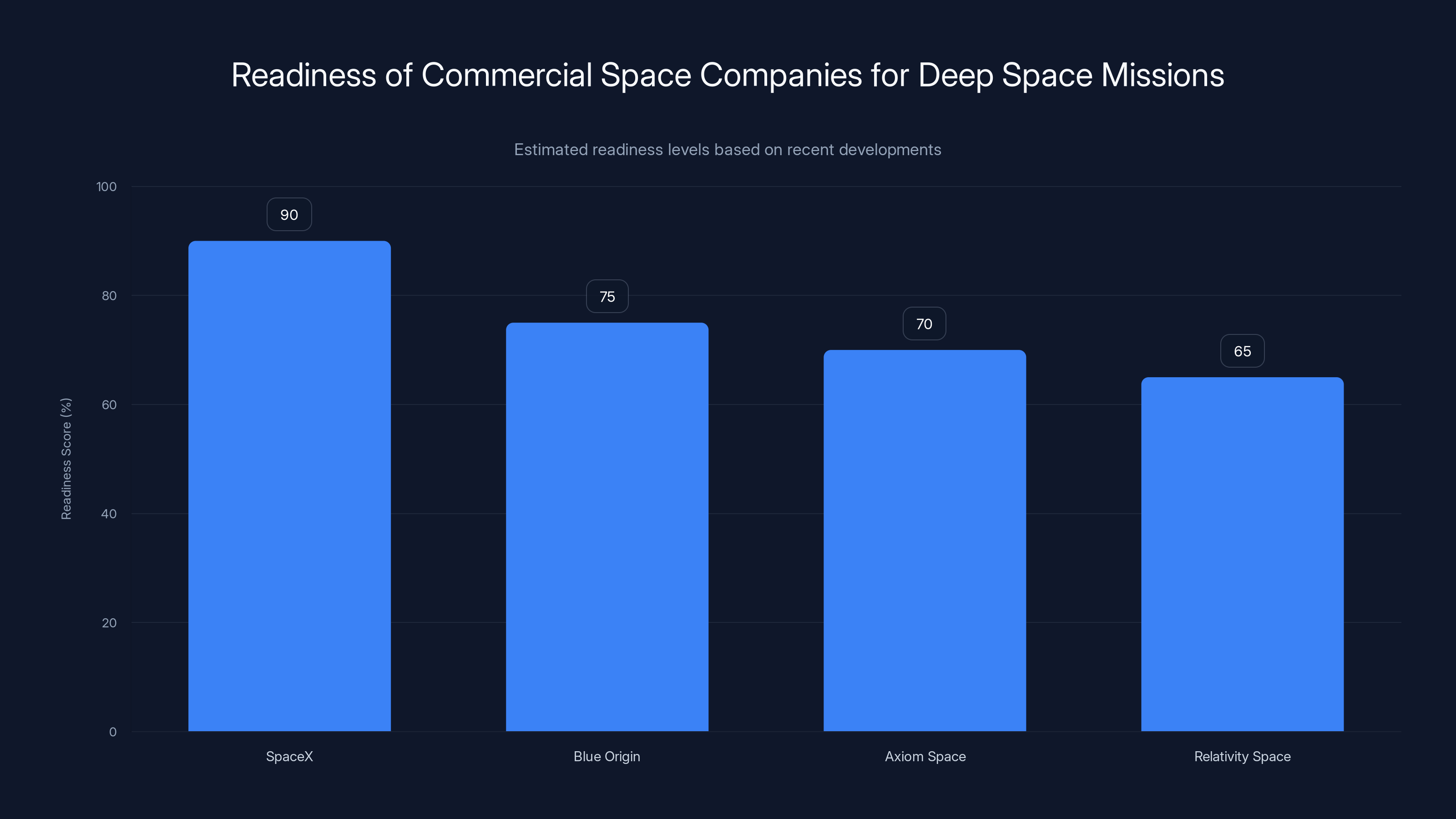

Commercial providers like SpaceX and Blue Origin could reduce deep space mission costs by up to 75% compared to government-operated systems. Estimated data based on projected costs.

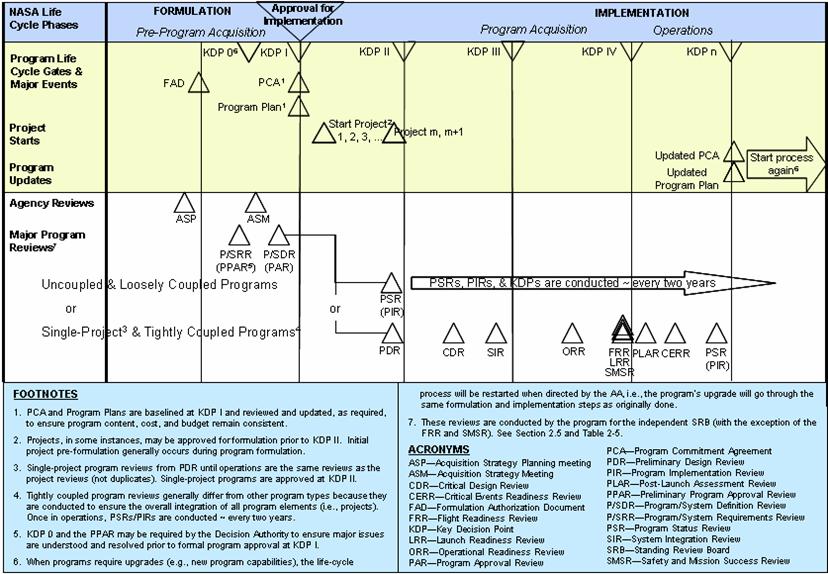

Understanding the NASA Reauthorization Process

Before diving into what this amendment means, you need to understand what a NASA reauthorization actually does. It's one of those legislative mechanisms that people gloss over because it's not as flashy as a rocket launch or as immediately consequential as an appropriations bill.

Here's the core distinction: reauthorization bills set policy direction. They tell the space agency what Congress wants it to do, what priorities matter, and what capabilities should be developed. Appropriations bills, by contrast, are where the actual money shows up. You can authorize NASA to build a Mars lander all day long, but if Congress doesn't appropriate funding for it, nothing happens.

Congress passes NASA reauthorization bills roughly every two years. They're comprehensive legislative packages that address the full scope of the space agency's mission: human spaceflight, Earth science, planetary exploration, astrophysics, aeronautics research, and everything in between. These bills also establish or modify acquisition authorities, which is where Amendment No. 01 comes in.

Acquisition authority is the legal permission structure that lets NASA buy things from contractors. Without explicit congressional authorization, NASA has limited ability to procure services from private companies. You might think a government agency could just buy whatever it needs, but space is different. The sensitivity of the technology, the national security implications, and the historical relationship between NASA and large defense contractors mean Congress maintains tight control over how and from whom NASA can purchase.

When Congress grants new acquisition authorities, it's essentially expanding NASA's shopping list. The 2010 reauthorization granted NASA the authority to rely on commercial providers for crew and cargo to the ISS. That's why SpaceX and Boeing now fly regular missions to the station. Congress said: NASA, you can buy this service from private companies instead of doing it ourselves.

Amendment No. 01 extends that principle outward. It's saying: NASA, you can now buy deep space transportation from commercial providers too. Not just Earth orbit anymore. Deep space.

The Current Artemis Architecture Lock

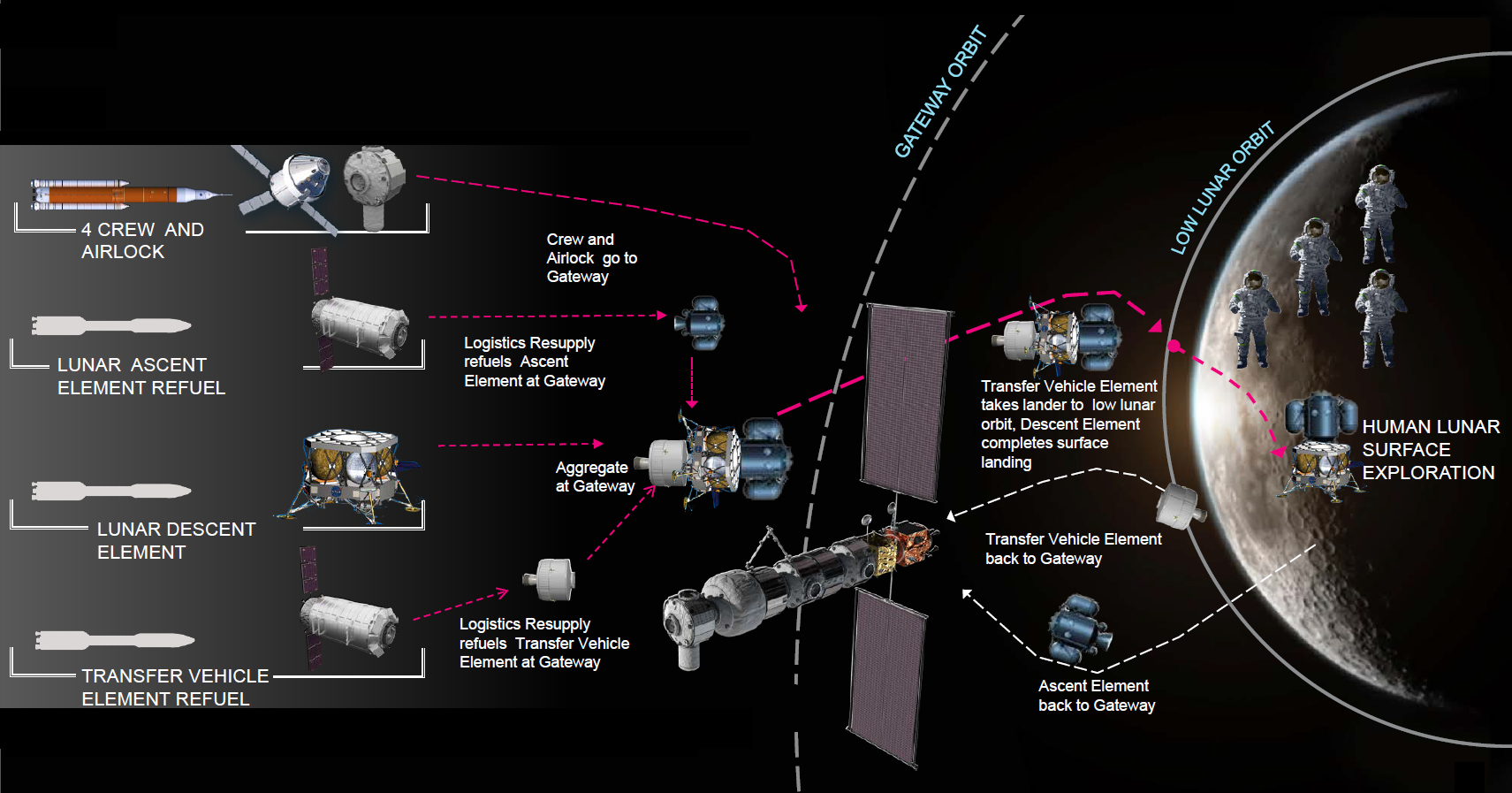

To understand why this amendment matters, you need to know what Artemis currently requires. The Artemis program is NASA's initiative to return humans to the Moon and eventually reach Mars. It's the successor to Apollo and the strategic foundation for American human spaceflight.

Artemis I through V have a strictly defined architecture. Every single component is specified by Congress and mandate:

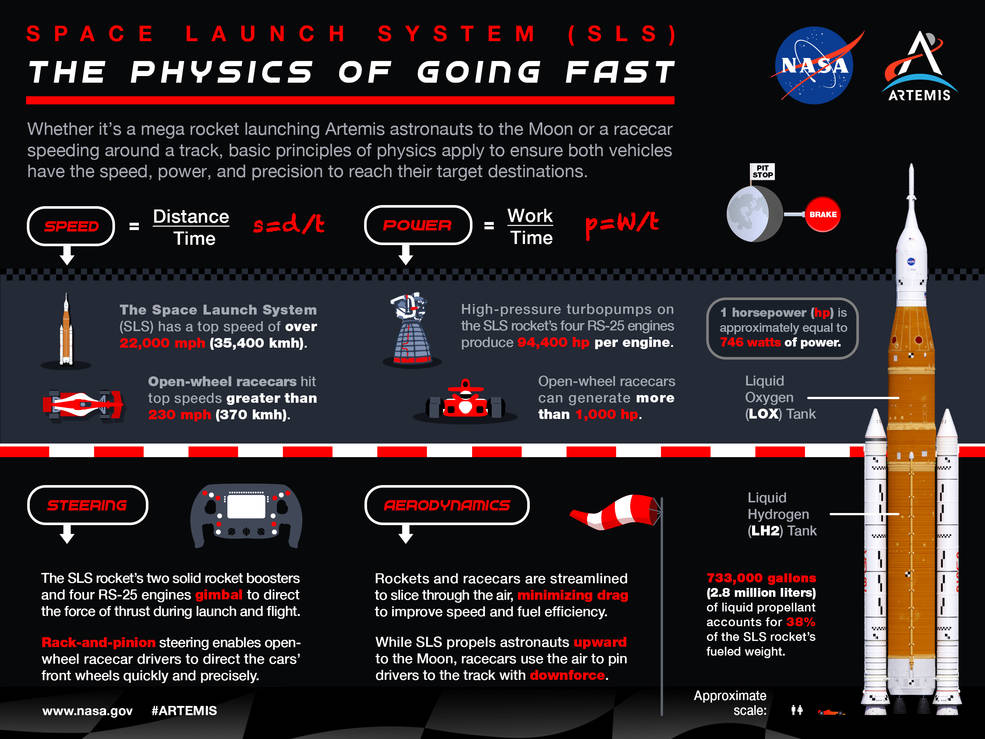

Launch Vehicle: Space Launch System. That massive, expensive, partially-reusable super heavy-lift rocket that NASA has been developing since 2011. No alternatives allowed.

Crew Spacecraft: Orion. The capsule designed for deep space missions. It's modular, cone-shaped, built around proven Apollo heritage principles. NASA controls this.

Lunar Lander: This is where some flexibility exists, but it's minimal. The contract went to either SpaceX or Blue Origin, but the architecture was determined by NASA. SpaceX won with Starship HLS (Human Landing System), but the broader framework was predetermined.

This architecture lock is why the Space Launch System, despite overruns and delays, continues to get funded. Congress mandated it. Changing it would require Congress to pass new legislation. As a result, NASA is locked into a transportation system that costs somewhere in the range of $2 billion per mission, with rockets that are expended rather than reused.

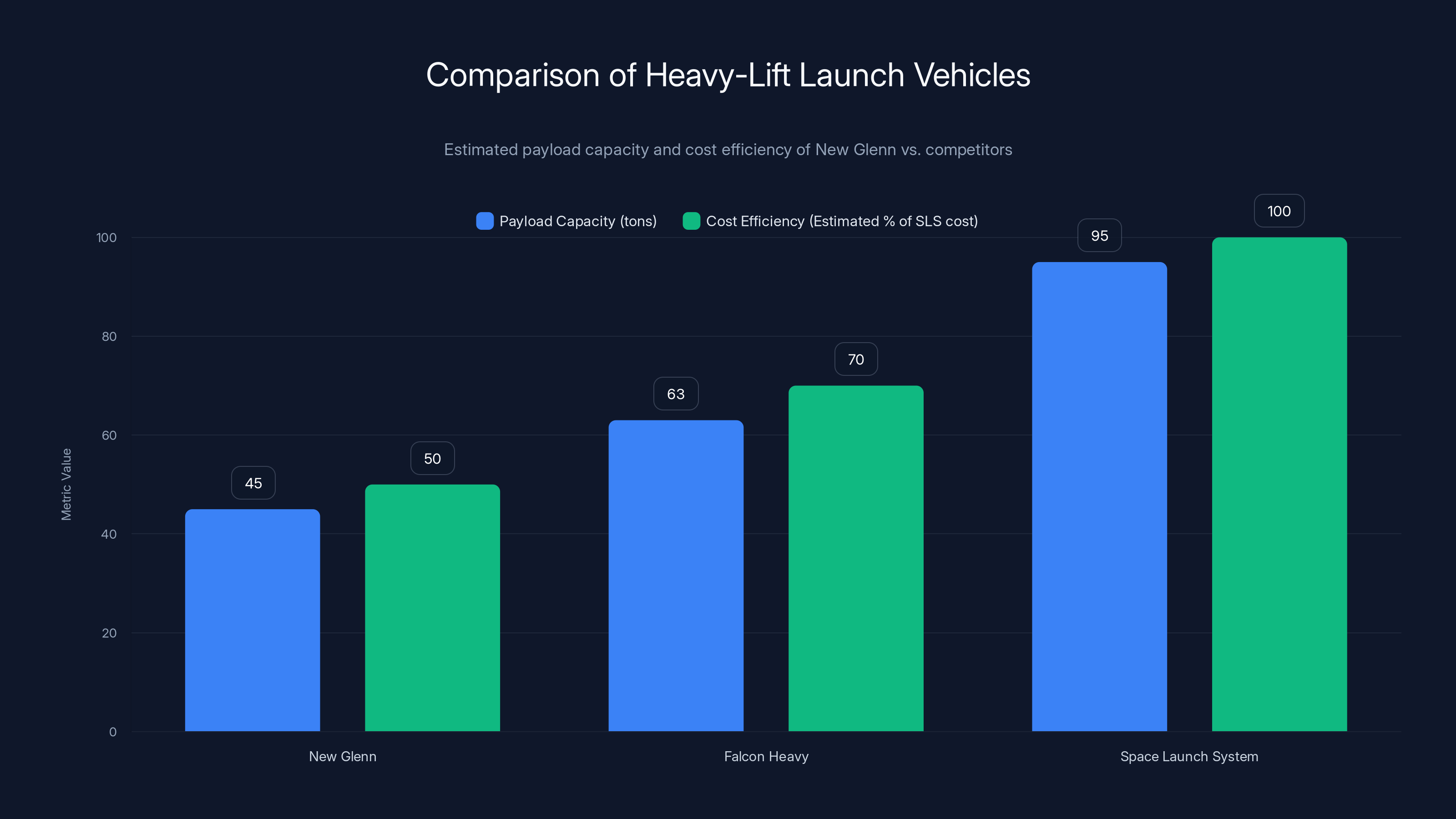

By contrast, SpaceX's Starship, still in development, is designed to be fully reusable. Blue Origin's New Glenn isn't mandated for anything but is being developed with the assumption of heavy-lift needs. These systems represent different philosophies: cost through reusability versus traditional expendable architecture.

Amendment No. 01 doesn't change the Artemis I-V structure. Those missions will proceed with SLS, Orion, and the designated lander. But it opens the door for Artemis VI and beyond. If SpaceX wanted to bid a full end-to-end Starship lunar mission, it could. If Blue Origin wanted to launch Orion on New Glenn, that's now on the table. If an in-space transportation company like Impulse Space wanted to propose a lunar cargo delivery service, they could submit a bid.

This is the seismic shift. Not an immediate change to existing programs, but permission for competition in future ones.

Estimated data shows SpaceX Starship could reduce costs by up to 50x compared to SLS, significantly impacting mission feasibility.

What Amendment No. 01 Actually Says

Let's examine the amendment's language precisely, because the devil lives in the details with legislation.

"The Administrator may, subject to appropriations, procure from United States commercial providers operational services to carry cargo and crew safely, reliably, and affordably to and from deep space destinations, including the Moon and Mars."

Break this down into components:

"The Administrator may": This gives NASA's leadership discretionary authority. It's not a mandate. NASA doesn't have to use commercial providers for every deep space mission. It could choose to stick with traditional approaches. But it can now pursue commercial options if leadership decides it's advantageous.

"Subject to appropriations": This is critical. The permission exists, but Congress still controls the money. Any commercial deep space program would need to be funded through appropriations bills. This prevents runaway spending but doesn't guarantee funding.

"United States commercial providers": There's specificity here. It's not any company. It's specifically U.S.-registered commercial entities. This protects American industry and maintains national security considerations. Foreign companies, even allied ones, wouldn't qualify.

"Operational services": The language uses "services" rather than specific hardware. This is intentional and expansive. It's not saying NASA can buy a rocket or a spacecraft. It's saying NASA can buy transportation services. That's different. A service can be delivered through various architectures.

"To carry cargo and crew": Both unmanned (cargo) and crewed missions. Nothing excluded.

"Safely, reliably, and affordably": Three criteria that any commercial provider would need to meet. These aren't vague terms; they can be measured and contractually enforced.

"To and from deep space destinations, including the Moon and Mars": This is the geographic scope. Not limited to Earth orbit. Not limited to cislunar space. Specifically includes lunar and Martian destinations. The "including" phrasing suggests those are examples, not an exhaustive list. In-space transfer, asteroid missions, and other deep space destinations could potentially qualify.

The generality of "operational services" and "deep space destinations" is the amendment's genius. It doesn't prescribe specific rockets, spacecraft, or architectures. It just opens a door and says if you can provide the transportation service safely, reliably, and affordably, you can bid for it.

That's why in-space companies get excited about this. Impulse Space, for instance, doesn't build rockets. It builds orbital transfer vehicles and propulsion systems. Under this amendment, a mission architecture could look like: SpaceX launches Starship from Earth. Impulse Space provides in-space transportation to the lunar surface. NASA procures the complete service even though it involves multiple commercial providers.

The Commercial Spaceflight Federation's Response

Amendment No. 01 didn't emerge from Congress in a vacuum. It was backed by industry advocates who have spent years building the case for commercial deep space capabilities.

Dave Cavossa, president of the Commercial Spaceflight Federation, released a statement immediately after the committee vote: "This is quite a step in the right direction for the future of commercial space transportation options for deep space. It is also very much in line with this administration's focus on commercial solutions and competition. This provides NASA with flexibility to procure additional services for the Moon and Mars in the future."

Notice the framing. Not revolutionary. Not game-changing. "A step in the right direction." That's measured language from someone who understands Congress. You don't oversell these things. You acknowledge the progress, you note the alignment with administration priorities, you emphasize what it enables.

The Commercial Spaceflight Federation has been the organized voice of the commercial space industry for years. Its membership includes SpaceX, Blue Origin, Relativity Space, Axiom Space, Sierra Space, and dozens of other companies. These aren't fringe operators. They're the actual entities building the next generation of launch systems and spacecraft.

What Cavossa's statement highlights is something that has been true but not formally acknowledged in legislation: the commercial space industry is ready. SpaceX has demonstrated it can launch heavy-lift cargo reliably. Blue Origin is building New Glenn specifically for heavy-lift applications. Axiom Space is building commercial space station modules. Relativity Space is developing 3D-printed rockets.

For years, the argument from NASA and traditional contractors was that the commercial sector wasn't mature enough for deep space missions. Too risky. Unproven. The technology isn't ready. But that argument gets harder to make when SpaceX is regularly landing orbital-class rockets, when Starship is iterating toward full reusability, when Blue Origin's New Glenn is on track for 2025-2026 operational status.

The Commercial Spaceflight Federation's response to Amendment No. 01 reflects a strategic calculation: this permission is valuable, but only if NASA actually uses it. The real work comes next. The amendment grants authority. Now NASA has to establish the process, set the requirements, and actually invite bids from commercial providers.

Rep. Brian Babin's Role as Committee Chair

Amendment No. 01 was offered jointly by Rep. Brian Babin (R-Texas), chair of the House Committee on Science, Space, and Technology, and Zoe Lofgren (D-Calif.), the ranking member, plus three other legislators. That's significant. It's not a partisan amendment. It's backed by both the chair and the ranking member. That's consensus-level support in Congress.

Babin has been deeply involved in space policy for years. His district includes NASA's Johnson Space Center in Houston, so space isn't abstract for him. It's a major employer and a fundamental part of his community. But Babin isn't a reflexive defender of legacy space programs. He's genuinely interested in what works.

During the committee hearing where the amendment was debated, Babin said: "When America returns to the Moon as part of Artemis, we will do so in partnership with our innovative commercial sector. As we venture farther into space, we will continue to rely on the ingenuity of the private sector as new capabilities come online."

That's not boilerplate language. That's a specific acknowledgment of a shift in strategy. The language moves from government-led deep space exploration to government-commercial partnership. The Moon and Mars get reached through collaboration, not solely through government execution.

Babin's framing also hints at something implicit in the amendment: government exploration programs are expensive and slow. Commercial partnerships are faster and cheaper. If you want a sustainable long-term presence on the Moon, you don't build that through a series of government-funded flagship missions. You enable commercial companies to offer services, and they compete on price and performance.

This aligns with broader policy thinking. Traditional NASA programs like the Space Shuttle and Space Launch System were government-owned and operated. They achieved remarkable things, but they were also very expensive and slow to evolve. Commercial Crew and Cargo shifted the model to government purchasing services from private providers. That worked better in terms of cost and schedule. Deep space exploration could benefit from the same model.

Commercial providers could reduce lunar mission costs by 80-90% and make Mars missions feasible within a decade. (Estimated data)

Rep. Zoe Lofgren's Industry Perspective

Rep. Lofgren, the ranking member on the committee, provided another important perspective during the hearing. She highlighted the transformation of American commercial spaceflight capabilities:

"It wasn't that long ago that the commercial launch business was dominated by foreign launch providers, and now the reverse is true. So this makes America stronger."

That's a striking observation. Twenty years ago, if you wanted to launch a satellite commercially, you'd probably use Arianespace (European), or possibly Sea Launch (Russian-Ukrainian joint venture). American commercial launch options were limited. Space Shuttle was government-only. Delta and Atlas rockets were expensive and limited in availability.

Today, if you want to launch something into space cheaply and reliably, you use SpaceX. If you need heavy-lift capacity, you're considering SpaceX Starship or Blue Origin New Glenn. American commercial launch dominance is overwhelming.

Lofgren's point is that this success story, which happened in low Earth orbit with cargo and crew services, should extend to deep space. The same model that worked for the ISS supply chain can work for lunar and Mars missions. That's not speculation. That's extrapolation from proven success.

What's interesting about Lofgren's framing is the national security dimension. She emphasizes that American commercial dominance "makes America stronger." That's not just about economic capability. It's about strategic independence. When America relies on foreign launch providers, it's strategically vulnerable. When American companies dominate global commercial spaceflight, America maintains advantage.

Amendment No. 01, from this perspective, isn't just about getting to the Moon cheaper. It's about ensuring that America's space capabilities remain competitive, advanced, and independent. Congress is saying: we want American companies to win in deep space, and we're going to give NASA the authority to let that happen.

SpaceX's Potential Role in Deep Space

SpaceX is the obvious beneficiary of this amendment. The company already has major contracts: crew and cargo to the ISS through Commercial Crew and Cargo programs, a lunar lander contract through Artemis, and government contracts for national security launches.

But SpaceX's transformational potential lies with Starship. This is a fully reusable super heavy-lift system designed from the ground up for rapid reusability. Once operational, Starship could theoretically launch a lunar mission for a fraction of what Space Launch System costs.

Amendment No. 01 opens the door for SpaceX to bid on Artemis VI and beyond using Starship instead of requiring SLS and Orion. The company could propose: we'll launch Starship with lunar payload, land on the Moon, return to Earth. One company, start to finish, potentially cheaper and faster than the government-mandated architecture.

This creates competitive pressure on NASA and on traditional contractors. Not in a negative way, but in the way competition usually works: better performance, lower costs, faster innovation.

SpaceX is also developing capabilities beyond just launch. The company is working on in-space refueling, which would be essential for Mars missions using Starship. Starship could launch Earth-orbit refueling depots, enable fuel transfer in orbit, and then launch to Mars with full tanks. This is a capability that doesn't exist yet in operational form, but SpaceX is actively developing it.

The commercial deep space amendment essentially says: if you can execute this, we'll buy it from you. That's powerful incentive alignment.

Blue Origin's New Glenn and Deep Space Ambitions

Blue Origin's strategic position is somewhat different from SpaceX. The company is further back in development timelines. New Glenn, its heavy-lift launch vehicle, isn't yet operational. But it's coming, targeted for 2025-2026 launches.

New Glenn is designed from the ground up for heavy-lift applications. Blue Origin has been explicit about this. The rocket is bigger than Falcon Heavy, with payload capacity that rivals Space Launch System but at a fraction of the cost. New Glenn is also partially reusable, with the first stage intended for multiple flights.

Amendment No. 01 opens the possibility for Blue Origin to bid on deep space missions using New Glenn. The company could propose launching Orion spacecraft on New Glenn instead of SLS. Or launching cargo to lunar orbit. Or supporting Mars missions.

Further out, Blue Origin is developing Blue Moon, a lunar lander program. Combined with New Glenn for launch, Blue Moon for landing, Blue Origin could bid on a complete lunar transportation system. This would directly compete with SpaceX's Starship-based approach.

Blue Origin's situation is interesting because the company has been less flashy about space launches than SpaceX but has maintained steady progress on heavy-lift capabilities. New Glenn is a serious engineering project backed by significant resources. When it becomes operational, it immediately becomes relevant to deep space missions.

The amendment benefits Blue Origin specifically because it allows alternative launch vehicles. If Congress had continued to mandate Space Launch System for Artemis missions, New Glenn's development would be interesting academically but less commercially compelling. By opening competition, Amendment No. 01 creates immediate market demand for New Glenn's capabilities.

New Glenn is projected to offer competitive payload capacity and cost efficiency, potentially operating at 50% of the Space Launch System's cost. Estimated data.

In-Space Transportation and Emerging Providers

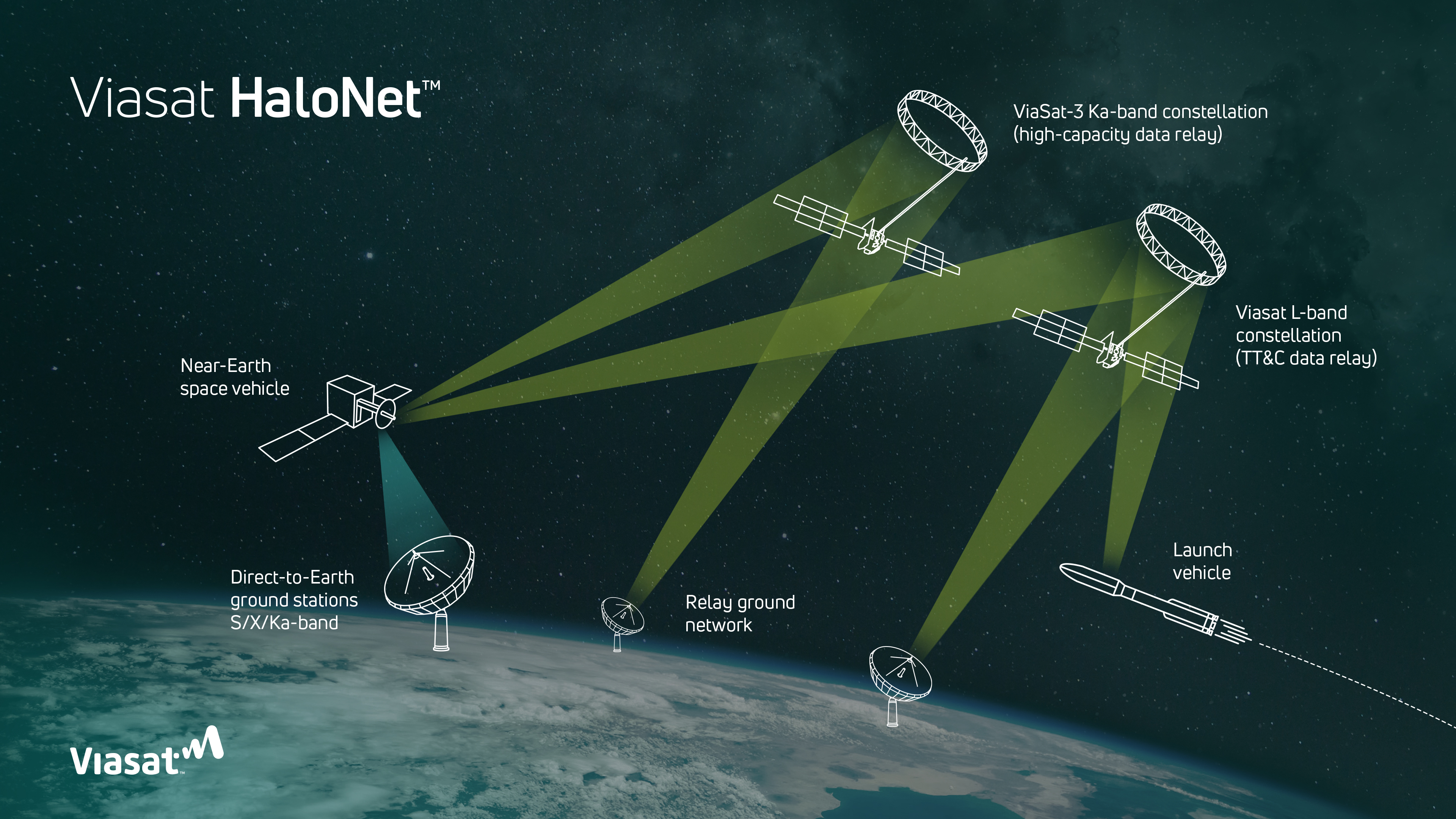

One of the most interesting aspects of Amendment No. 01 is that it doesn't limit competition to launch vehicles and spacecraft. The language about "operational services" and "in-space" destinations opens the door for specialized companies in the in-space transportation sector.

Companies like Impulse Space are developing orbital transfer vehicles and advanced propulsion systems. These aren't launch vehicles. They're not landing systems. They're specialized platforms designed to move cargo and crew between orbital locations efficiently.

Consider a mission architecture: SpaceX launches a lunar payload on Starship to Earth orbit. Impulse Space's orbital transfer vehicle docks with the payload and propels it to lunar orbit. A separate lunar lander takes it to the surface. NASA procures the complete service, but it involves multiple commercial providers.

This modular, competitive approach to deep space transportation is something the traditional government program structure couldn't easily accommodate. There was no mechanism to integrate services from multiple commercial providers into a cohesive mission. Amendment No. 01 enables that. It says NASA can procure services, and those services can be delivered by whomever can do it best.

This matters because specialized companies can innovate in their niches. An in-space transfer company focuses obsessively on efficient orbital mechanics, reliable engine performance, and rapid development. A launch company focuses on launch. A landing company focuses on landing. Each can excel in their domain.

The emerging in-space transportation sector is still small, but it's growing. Companies recognize that deep space logistics will be critical for sustained lunar operations and Mars missions. Amendment No. 01 essentially signals that commercial providers in this space should keep developing. NASA will be a customer.

Implementation: How NASA Will Execute This Authority

Amendment No. 01 grants authority, but Congress doesn't specify how NASA should use it. That leaves significant flexibility for NASA leadership to determine implementation.

The most likely path is that NASA would establish a new program office specifically for commercial deep space services. Similar to how NASA has a Commercial Crew and Cargo program office, it could create a Commercial Deep Space program office.

This office would likely:

Establish requirements: What capabilities does NASA need? How much payload to the Moon? How often? What reliability standards? What timeline? These requirements would be codified.

Issue solicitations: NASA would announce to the market that it's looking to procure deep space transportation services. Companies would bid. Proposals would be evaluated on technical capability, cost, schedule, and company track record.

Award contracts: NASA would select providers and establish long-term service contracts. Similar to how SpaceX and Boeing have ongoing Commercial Crew contracts.

Manage oversight: NASA would monitor performance, conduct reviews, and ensure the service providers maintain safety and reliability standards.

The Commercial Crew Program provides a useful template for how this could work. When NASA first transitioned from flying Space Shuttle to purchasing crew services from commercial providers, it was a big cultural shift. Contracts had to be structured differently. Oversight mechanisms had to be redesigned. But it worked. The system is now proven.

Deep space services would likely follow a similar path, though with additional complexity. Deep space missions are more challenging than Earth orbital missions. The failure modes are higher. The technical challenges are greater. But the basic contracting model is well-established.

There are probably 12-18 months of work ahead if NASA wants to establish a Commercial Deep Space Services program. Requirements development, contract language, oversight framework, and industry engagement. But the legislative authority is now in place to enable it.

The Role of Appropriations: Funding the Future

Amendment No. 01 is enabling legislation, not a funding mechanism. This is crucial to understand. The amendment says NASA can procure deep space services from commercial providers, but it doesn't allocate money to do it.

Funding comes through appropriations bills. Every year, Congress passes appropriations legislation that allocates specific dollar amounts to specific programs. NASA's budget goes through this process. If NASA wants to establish a Commercial Deep Space program, it would need to request funding in its appropriations request, and Congress would need to approve that funding.

This creates a potential disconnect. Amendment No. 01 might grant authority, but if Congress doesn't appropriate money for commercial deep space services, the authority sits unused.

However, the political dynamics suggest funding is likely. Reauthorization and appropriations are usually handled by different committees, but they're closely coordinated. If a committee has unanimously passed an amendment, that typically signals that broader support exists for the underlying goal. Appropriations committees usually respect these signals.

Additionally, if commercial providers can deliver deep space services cheaper than traditional government approaches, the fiscal argument is strong. In an era of budget constraints, lower-cost options for achieving strategic objectives tend to get funded.

The appropriations dynamic also explains why the amendment language is general rather than specific. Congress doesn't want to mandate a particular commercial provider or architecture. It wants to leave that to NASA and the competitive process. But it signals that it's willing to fund commercial deep space services if they're genuinely more cost-effective.

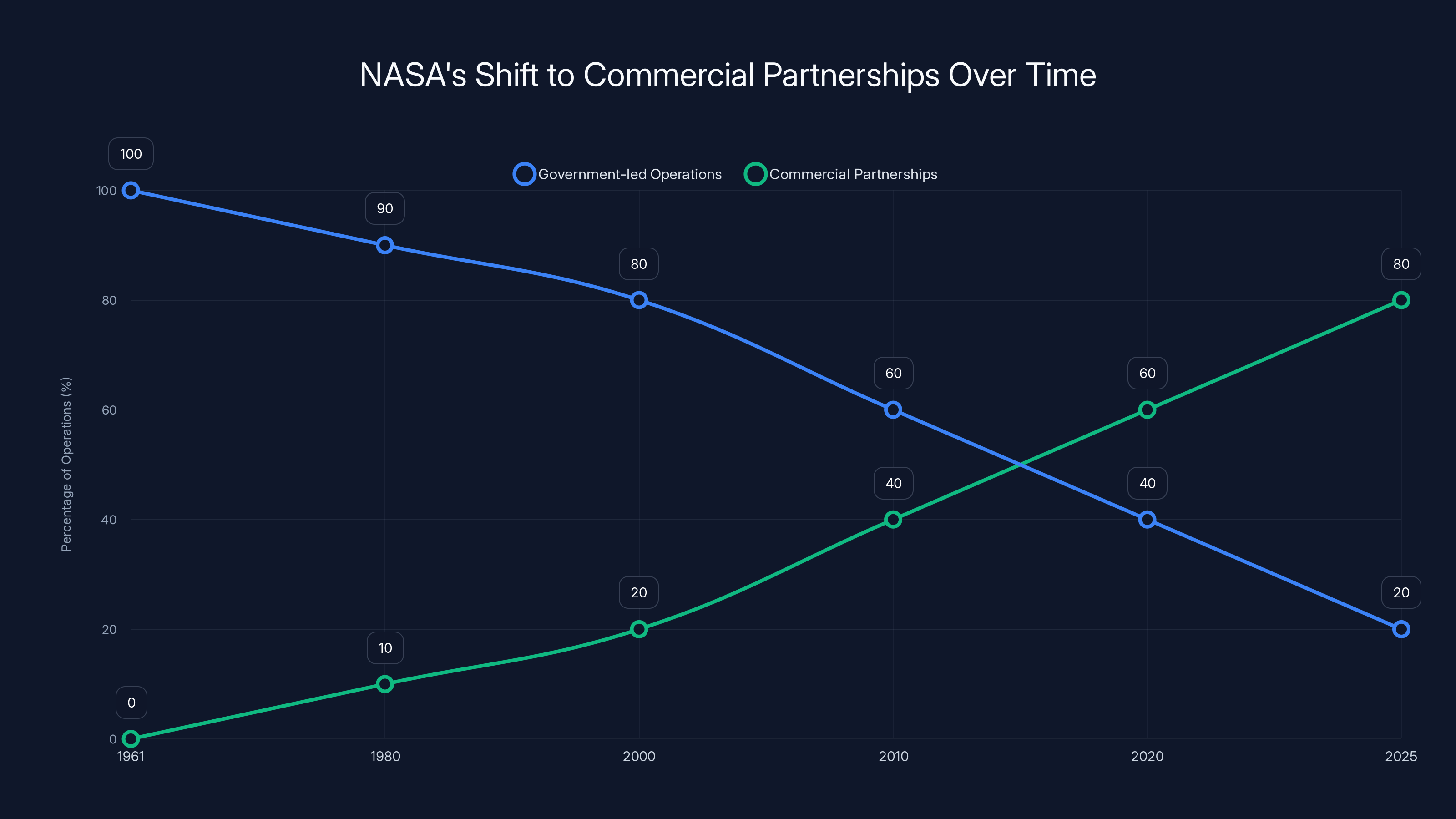

Estimated data shows a significant shift from government-led operations to commercial partnerships in NASA's strategy, particularly from 2005 to 2025.

National Security and Foreign Competition Considerations

Amendment No. 01 specifies "United States commercial providers," which raises an important point: space policy has significant national security dimensions.

Launch vehicles and spacecraft are sensitive technologies. They involve rocket engines, control systems, structures that can handle extreme environments, and integration engineering that few organizations possess. Allowing foreign companies to bid on deep space missions would be strategically problematic. You're not just buying a transportation service. You're sharing significant operational details about lunar and Mars missions with another country.

So the "United States commercial providers" language is both a nationalism preference and a security requirement. NASA can buy services from American companies, which advances American economic interests and maintains strategic independence.

There's also an international dimension worth considering. The amendment represents a shift in how America approaches deep space exploration. Historically, other spacefaring nations (Russia, Europe) had government-led programs. Some still do. But the shift to commercial competition is distinctly American. It reflects confidence in the American commercial space sector and a preference for market-driven solutions.

This could set a pattern that other countries follow, or it could create divergence. If American commercial deep space services become dominant globally, it extends American strategic influence in space.

National security implications also explain why Amendment No. 01 has bipartisan support. Space security isn't a left-right issue. Both parties care about American dominance in space. The amendment advances that goal by empowering American commercial providers.

Comparison to International Deep Space Programs

To understand the significance of this shift, it's worth comparing how other spacefaring nations approach deep space exploration.

European Space Agency: Government-led Ariane launch program, funded by member states. Governance is slow, consensus-based, expensive. But reliable and well-established.

Russia: Government Roscosmos controls launches and deep space capability. Commercial services exist but are limited and state-controlled.

China: Government-led, five-year plans, centralized execution. Increasingly advanced but not commercially oriented.

Japan: Mix of government agency (JAXA) and commercial providers. Smaller scale than other major powers.

India: Government-led ISRO with growing competence and improving costs through engineering efficiency.

United States: Government-led NASA + private commercial sector in partnership. Competition between providers, rapid iteration, cost reduction through reusability.

The American approach, as formalized by Amendment No. 01, is essentially: government sets objectives and budget, commercial providers compete to meet those objectives, and the market mechanism drives innovation and cost reduction.

This approach has proven successful in Earth orbital markets. Why not extend it to deep space? That's the underlying logic.

Future Mission Architectures Enabled by This Amendment

Amendment No. 01 doesn't specify what future missions should look like, but we can envision some possibilities based on current capabilities and stated goals.

Lunar cargo missions: NASA needs to supply lunar bases with equipment, fuel, food, water. Commercial providers could operate cargo services to the Moon, similar to how they operate cargo services to the ISS. SpaceX Starship could launch lunar cargo. Competition would drive down costs.

Crewed lunar missions: Beyond Artemis V, NASA could procure end-to-end crewed lunar missions from commercial providers. SpaceX or Blue Origin could bid. Multiple providers could offer different approaches. Missions could happen more frequently than traditional government-led programs.

Lunar surface infrastructure: Commercial providers could develop and operate lunar landers, habitats, and equipment depots. NASA would purchase access rather than own and operate the systems.

Mars cargo missions: Future Mars missions would require delivering cargo to Mars in advance of human arrival. Commercial providers could operate these cargo missions. SpaceX is already developing capabilities for this with Starship's Mars transit architecture.

In-space refueling depots: Orbital refueling depots would be essential for efficient Mars missions. Commercial companies could develop and operate these depots. NASA would purchase fuel services.

Asteroid missions: Beyond Moon and Mars, Amendment No. 01 could enable commercial deep space services to asteroids for scientific study or resource assessment.

These architectures represent a fundamentally different approach to deep space exploration. Instead of government-led flagship missions, you'd have continuous operations enabled by multiple commercial providers competing on performance and cost.

The timeline for these capabilities varies. Lunar cargo services could begin within 5-7 years. Mars cargo missions would take longer, perhaps 10+ years. But the legislative permission is now in place. Companies can plan development with confidence that NASA will be a customer.

Estimated readiness scores suggest SpaceX leads in deep space mission capability, with others making significant progress. Estimated data.

The Political Path Forward: Full House and Senate

Amendment No. 01 passed the House committee unanimously. That's politically significant. But the legislative journey isn't over.

The amendment must now be incorporated into the full NASA reauthorization bill. That bill goes to the full House for a vote. Assuming it passes (which is likely given the committee vote), it then goes to the Senate.

The Senate would consider the bill, potentially offer amendments, debate, and vote. If the Senate passes an identical version, the bill goes to the President for signature, and Amendment No. 01 becomes law.

If the Senate passes a different version, the bill goes to a conference committee to reconcile differences. The House and Senate would then vote again on the compromise version.

Historically, NASA reauthorization bills are not particularly controversial. They usually pass with broad bipartisan support because space exploration has broad public support and benefits multiple districts. The full House passage is likely. Senate passage is likely. Presidential signature is likely.

The timeline could extend several weeks. House floor time is limited. Senate floor time is even more limited. But the political trajectory suggests Amendment No. 01 will become law.

Once it becomes law, implementation would follow. NASA would develop its approach, establish program offices, issue solicitations, and begin contracting with commercial providers. This could take 12-24 months.

So if everything moves quickly, we could see the first NASA solicitations for commercial deep space services sometime in 2026-2027.

Budget Implications and Cost Scenarios

One of the most compelling arguments for commercial deep space services is cost. Preliminary estimates suggest dramatic savings compared to government-mandated architectures.

Space Launch System is expensive. A single SLS launch, when fully accounting for development and operational costs, costs somewhere in the range of $2 billion. Maybe more. It's hard to pin down exactly because costs are allocated across multiple appropriations and programs, but the figure is consistently large.

By contrast, SpaceX Starship is projected to cost $10-50 million per launch once operational and achieving rapid reusability. That's a 20-50x cost difference.

Even accounting for the fact that Starship hasn't achieved full operational reusability yet, the cost differential is enormous. A lunar mission on Starship might cost

That kind of cost difference changes the equation for sustained exploration. If lunar missions cost

For Mars missions, the economics are even more dramatic. A human Mars mission using traditional architecture might cost

These cost projections are estimates based on current trends. Actual costs depend on market competition, performance reliability, and technological maturation. But the direction is clear: commercial competition drives costs down.

Congress understands this. That's why Amendment No. 01 has bipartisan support. It's not just about philosophy or preference for commercial solutions. It's about getting better results with the tax dollars Congress appropriates.

Technological Risk and Reliability Considerations

One objection to shifting deep space missions to commercial providers is risk. Space is dangerous. Failure is catastrophic. Can you really trust commercial companies with human spaceflight beyond low Earth orbit?

This is a legitimate concern, but the evidence suggests the answer is yes. Commercial Crew and Cargo programs have operated successfully for years. SpaceX has demonstrated reliability comparable to or exceeding traditional government programs. Blue Origin, while newer to crewed spaceflight, has shown competent engineering.

Deep space missions would certainly require rigorous certification. NASA would need to verify that commercial providers have demonstrated the reliability, redundancy, and safety culture necessary for these missions. But the basic capability exists.

Furthermore, competition can actually enhance reliability. If two companies are bidding for lunar missions, both have incentive to achieve excellent reliability. A company that has failures won't get future contracts. This creates market pressure for high reliability.

Arguably, the traditional government-led approach has been more risk-averse to the point of inefficiency. Multiple layers of oversight, extensive testing, long development timelines. Commercial companies sometimes move faster because they're not hamstrung by bureaucratic requirements.

But for deep space missions, the reliability bar would be set high. NASA would specify requirements: what redundancy is needed? What reliability must be demonstrated? What failure modes are unacceptable? Companies would bid to meet those requirements. The contracts would be structured to incentivize high reliability.

This isn't new territory. NASA has been managing contractor relationships and performance standards for decades. The difference with Amendment No. 01 is that there would be multiple contractors competing, rather than a single mandated provider.

Timeline Projections for Mission Availability

Assuming Amendment No. 01 becomes law and NASA receives appropriations to implement it, when could actual commercial deep space missions begin?

2026-2027: NASA establishes Commercial Deep Space Services program office, develops requirements, issues first solicitations.

2027-2029: Companies bid, contracts are awarded, development of mission-specific hardware and software, manufacturing and testing.

2029-2031: First crewed or cargo missions using commercial deep space services. SpaceX Starship lunar cargo is probably the leading candidate. Blue Origin might offer lunar services once New Glenn is operational.

2031-2035: Expanded commercial deep space operations, multiple providers offering services, sustained lunar exploration enabled by commercial transportation, initial Mars cargo missions.

2035-2040: Human missions to Mars potentially enabled by robust commercial deep space infrastructure.

These timelines are optimistic in assuming good execution and adequate appropriations. Reality could extend these by years. But they illustrate the possible trajectory if Amendment No. 01 is implemented.

Compare this to the current Artemis program: Artemis III (first lunar landing with new systems) was originally planned for 2025 but has slipped to the early 2030s. Artemis IV and beyond would continue through the 2030s-2040s. The SLS-mandated approach is slower.

Commercial competition could accelerate this. If SpaceX can fly lunar missions more frequently and cheaply, sustained exploration becomes more feasible. If Blue Origin offers an alternative, pricing improves through competition. The timeline could actually advance rather than slip.

Industry Investment and Development Signals

Amendment No. 01 doesn't directly fund commercial deep space development, but it sends a signal to the market. Companies now know that NASA is open to procuring deep space services from commercial providers. This encourages private investment in deep space capabilities.

SpaceX has already invested billions in Starship development. The company believes the rocket will have applications beyond government contracts. Enabling lunar and Mars missions through commercial services is exactly the kind of large market that justifies that investment.

Blue Origin's New Glenn development is similarly justified by heavy-lift demand. If the amendment opens demand from NASA for deep space services, that justifies New Glenn's development and operational costs.

Emerging companies in the in-space transportation sector need these signals. They're developing specialized hardware and software for deep space logistics. Amendment No. 01 indicates that NASA will purchase these services. That's the market signal these companies need to attract investment and justify development.

In a sense, Amendment No. 01 is a soft industrial policy. Congress is saying: we want a vibrant commercial deep space sector. We're going to create demand as a customer. Companies can invest with confidence that the market will exist.

This differs from traditional government procurement where the government develops specifications and companies bid to meet them. Here, Congress is opening the door and saying: innovate, develop capabilities, and NASA will be a customer. The market mechanism does the work of spurring development.

Sustainability and Long-Term Implications

The deeper implication of Amendment No. 01 is about sustainability of deep space exploration.

Traditional government-led programs are episodic. You develop a system, fly several missions, the political environment changes, the program gets redirected. Apollo achieved something remarkable but then ended. The Space Shuttle was operationalized but became unaffordably expensive.

Commercial systems have the potential to be sustained because they operate on market principles. If SpaceX can profitably operate lunar cargo services, it will continue. If there's demand for lunar surface operations, companies will develop that capability. The market sustains it.

For the Moon and Mars, this matters enormously. You don't establish a scientific research station or resource extraction operation with a few flagship missions. You need sustained access, regular resupply, continuous improvement. Commercial providers, operating on market principles, can provide that.

Amendment No. 01 is therefore a foundational step toward making deep space exploration sustainable. It shifts the burden from government execution to market demand. NASA becomes a customer and priority setter, but not the sole operator.

Long-term, this could lead to a flourishing commercial deep space economy. Companies operating space tourism, scientific research facilities on the Moon, resource extraction, in-space manufacturing. NASA as an anchor customer, supporting initial development, but not the entire market.

This vision is perhaps 10-20 years away. But Amendment No. 01 puts the pieces in place.

Challenges and Implementation Hurdles

Despite the optimistic outlook, significant challenges remain for implementation.

Funding uncertainty: Appropriations are never guaranteed. Amendment No. 01 might grant authority, but Congress could consistently decline to appropriate funding for commercial deep space services. This would make the authority irrelevant.

Technical maturity: Companies still need to prove they can execute deep space missions reliably. Starship hasn't yet landed on the Moon. New Glenn hasn't flown. These systems need to demonstrate capability before NASA trusts them with complex missions.

Organizational culture: NASA has been structured around government-led programs for decades. Shifting to a commercial partnership model requires cultural change, new contracting approaches, and rethinking of roles. This isn't fast or easy.

Competition preservation: For commercial competition to work, multiple providers need to compete. If only SpaceX succeeds at providing deep space services, we've just substituted SpaceX for SLS as the mandated provider. Real benefits require multiple competitors.

International coordination: Deep space exploration often involves international partners (ESA, JAXA, etc.). Integrating commercial providers into these partnerships requires agreement and coordination.

Long-term commitment: If political priorities shift and deep space exploration gets deprioritized, the whole mechanism breaks down. Commercial providers won't invest in capability if demand is uncertain.

These challenges are real, but they're not insurmountable. NASA has successfully navigated the transition to commercial crew and cargo. Similar challenges existed. But the fundamental interest in space, supported by political consensus, enabled success.

Amendment No. 01 represents that same consensus for deep space. As long as that holds, the challenges are manageable.

The Broader Policy Shift This Represents

Amendment No. 01 fits into a broader policy shift toward reliance on commercial capabilities. This has been occurring for years, but this amendment formalizes it for deep space.

ISS resupply: Commercial cargo has been resupplying the ISS since 2012. NASA no longer operates cargo services.

Crewed Earth orbit: Commercial crew providers (SpaceX, Boeing) fly NASA astronauts to the ISS. NASA no longer operates crewed spaceflight in LEO.

Commercial space stations: NASA is encouraging private companies to develop commercial space stations. Eventually, NASA will buy services from private providers rather than operating ISS.

In-space logistics: Companies are developing refueling services, orbital transfer, space tug services. NASA will eventually purchase these from commercial providers.

Manufacturing and research in space: Commercial companies are developing in-space manufacturing platforms. NASA will eventually host experiments on these platforms rather than maintaining government-owned facilities.

Amendment No. 01 extends this model to deep space. The logic is consistent: government identifies objectives, commercial providers compete to meet those objectives, market mechanisms drive innovation and cost reduction.

This represents a long-term shift in how NASA operates. From 1961 to roughly 2005, NASA was predominantly government-led and government-operated. From 2005 to 2025, NASA has been transitioning to a partnership with commercial providers in low Earth orbit. From 2025 onward, Amendment No. 01 suggests NASA will extend that partnership to deep space.

This isn't a temporary trend. It reflects genuine structural advantages of commercial competition over government monopoly. Unless that changes, the trend will continue.

Final Perspectives: What This Means for Space Exploration

When you zoom out and look at Amendment No. 01 in the context of the broader space industry and exploration objectives, what does it mean?

First, it's a validation of commercial space companies. SpaceX, Blue Origin, and emerging providers have demonstrated capability. Congress is saying: we see what you've done, we're impressed, and we're ready to let you take on bigger challenges.

Second, it's a down payment on sustained deep space exploration. Government-led programs are episodic. Commercial services can be sustained. By opening the door to commercial deep space providers, Congress is betting that America can establish a long-term presence on the Moon and eventually Mars through market mechanisms rather than episodic government programs.

Third, it's recognition of fiscal reality. The era of unlimited budgets for flagship space programs is over. If you want sustained exploration on a reasonable budget, you need efficiency. Commercial competition provides that.

Fourth, it's a strategic choice about American competitiveness. China is advancing rapidly in space. Russia is geopolitically isolated but technically capable. By empowering American commercial space companies, Congress is investing in American dominance in a domain increasingly important to national security and scientific discovery.

Amendment No. 01 is modest in appearance but significant in implication. It's not a revolutionary document. It doesn't mandate anything or guarantee anything. It simply opens a door and says: if you can provide the service, NASA can buy it from you.

But that small change in procurement authority could reshape how humanity explores deep space for decades to come.

FAQ

What is Amendment No. 01 to the NASA Reauthorization Act?

Amendment No. 01 is legislative language that grants NASA the authority to procure deep space transportation services from United States commercial providers for cargo and crew missions to the Moon and Mars. Passed unanimously by the House Committee on Science, Space, and Technology, it opens the door for companies like SpaceX and Blue Origin to bid on deep space missions beyond the currently mandated Artemis V architecture.

How does this amendment change NASA's current deep space strategy?

Currently, Artemis I through V missions are locked into a specific architecture: Space Launch System rocket, Orion spacecraft, and a designated lunar lander. Amendment No. 01 doesn't change these mandated missions, but it enables future missions (Artemis VI and beyond) to use alternative systems and providers. NASA can now accept bids from commercial providers for complete deep space transportation services rather than using only government-mandated systems.

What are the cost implications of commercial deep space services?

Commercial providers could potentially reduce costs by 50-75% compared to government-operated systems. Space Launch System missions cost approximately

When will commercial deep space services actually become available?

If Amendment No. 01 becomes law and Congress appropriates funding, NASA could issue the first commercial deep space solicitations in 2026-2027, with actual missions potentially beginning between 2029-2031. SpaceX Starship lunar cargo missions are the leading candidate for initial commercial deep space services, potentially followed by Blue Origin offerings once New Glenn becomes operational.

How does this affect SpaceX and Blue Origin specifically?

The amendment directly benefits both companies by opening opportunities to bid on deep space missions using their developing systems. SpaceX can now propose end-to-end Starship lunar missions to compete with the SLS-Orion architecture. Blue Origin can bid on missions using New Glenn and Blue Moon once these systems are operational, creating genuine competition in the deep space market.

Will Amendment No. 01 change the Artemis program schedule?

No, Artemis I through V remains locked into the current architecture with Space Launch System, Orion, and the designated lunar lander. However, if commercial providers prove they can deliver deep space services more efficiently, subsequent Artemis missions could potentially accelerate compared to current timelines because more frequent missions would be cost-feasible with commercial providers.

What does this amendment mean for smaller space companies?

In-space transportation companies like Impulse Space benefit from the amendment's language about "operational services." The amendment doesn't mandate specific hardware, so mission architectures could involve multiple commercial providers working together. A SpaceX launch, Impulse Space in-space transfer, and a separate lunar lander represents a complete service that NASA could procure under this amendment.

Has Congress actually passed this amendment into law yet?

Amendment No. 01 passed the House Committee on Science, Space, and Technology unanimously on Wednesday and is now part of the broader NASA reauthorization bill. The full House must still vote on the bill, followed by Senate consideration. Once both chambers pass the bill and the President signs it, Amendment No. 01 becomes law. Full passage is expected but would take several weeks to months.

Why does the amendment specify "United States commercial providers"?

The restriction to U.S. commercial providers serves both national security and economic goals. Deep space technology is sensitive, and sharing operational details with foreign companies could create strategic vulnerabilities. Additionally, Congress wants American economic benefits and maintains American dominance in commercial space capabilities rather than relying on foreign providers.

How is this different from how NASA currently buys spacecraft and rockets?

Currently, NASA has specific contractors for specific systems under government development. With Amendment No. 01, NASA shifts to a service procurement model where it specifies what capability it needs (safe transportation to the Moon) and lets commercial providers bid on how to deliver that service. This distinction enables competition and innovation in ways that component-by-component government contracting doesn't.

Conclusion: The Gateway to Commercial Deep Space

Amendment No. 01 might not make headlines like a rocket launch, but it could prove more consequential. Congressional permission to procure deep space transportation from commercial providers represents a fundamental shift in American space policy. For the first time, Congress is formally opening deep space exploration to market competition rather than maintaining government monopoly.

This shift is grounded in proven success. Commercial crew and cargo to the ISS have demonstrated that private companies can outperform government programs on cost, schedule, and reliability. The logic is straightforward: if commercial competition works in low Earth orbit, why not extend it to the Moon and Mars?

The companies positioned to benefit from this amendment are impressive. SpaceX has demonstrated reusable rocket capability and is developing Starship specifically for lunar and Mars missions. Blue Origin is building New Glenn and Blue Moon, a complete heavy-lift and landing system. Emerging companies in in-space transportation are developing specialized capabilities that fit into commercial mission architectures.

The financial implications are dramatic. Lunar missions could cost 80-90% less with commercial providers. Mars missions could become feasible within a decade rather than a generation. Sustained deep space exploration transitions from government flagship programs to market-driven operations.

But the amendment is only the beginning. It grants authority, not funding. NASA must establish program offices, define requirements, and issue solicitations. Companies must demonstrate capability and win contracts. Congress must appropriate the money to make it real.

Those steps will take years. But Amendment No. 01 puts the pieces in place. It says to American space companies: develop your deep space capabilities, prove your reliability, and we'll be a customer. That's the signal the industry needs.

When historians look back at the origin of sustained commercial deep space exploration, Amendment No. 01 will likely be marked as a key moment. Not the flashy launch, not the dramatic landing, but the quiet legislative step that opened the door and said: American industry, the Moon and Mars are yours to explore if you can do it right.

That's the real significance. The future of deep space exploration, it seems, will be written by the commercial sector, with NASA as anchor customer and objective-setter. Whether that future arrives as planned depends on execution, funding, and political commitment. But Amendment No. 01 makes it possible.

Key Takeaways

- House committee unanimously passed Amendment No. 01 granting NASA authority to procure deep space transportation from U.S. commercial providers, fundamentally shifting exploration strategy

- Artemis I-V remains locked to SLS-Orion architecture, but Artemis VI and beyond can use alternative systems from SpaceX, Blue Origin, and emerging providers enabling competition

- Commercial deep space services could reduce mission costs by 75-90% compared to SLS, enabling 10-15x more frequent missions and sustainable long-term lunar and Mars exploration

- SpaceX Starship and Blue Origin New Glenn positioned as primary commercial alternatives, with emerging in-space logistics companies also eligible to bid on deep space services

- Implementation requires full House and Senate passage, presidential signature, and subsequent congressional appropriations to become operational, likely resulting in first commercial solicitations in 2026-2027

Related Articles

- SpaceX Starship V3 Test Flight: What the Mid-March Launch Means [2026]

- Artemis II Wet Dress Rehearsal: NASA's Final Test Before Moon Launch [2025]

- Blue Origin Pauses Space Tourism for NASA Lunar Lander Development [2025]

- NASA's Mars Orbiter Decision: What's at Stake [2025]

- Northwood Space Lands 50M Space Force Contract [2026]

- The Space Launch Race Heats Up: Ariane 6, India's Falcon 9 Clone, and the Future [2025]

![Commercial Deep Space Program: Congress Shifts NASA Strategy [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/commercial-deep-space-program-congress-shifts-nasa-strategy-/image-1-1770241306048.jpg)