Iran's Digital Isolation: Why VPNs May Not Survive This Crackdown

It's happening slowly, then all at once. In October 2022, Iran pulled the internet offline. Completely. No Instagram, no WhatsApp, no Twitter, no anything. It lasted days. But this wasn't just another crackdown. This was practice.

Now, the Iranian government isn't hiding its endgame anymore. It's building something far more permanent: a national intranet. A completely separate internet controlled entirely by the state, disconnected from the global web. And here's the kicker: they're being surprisingly open about it.

This isn't censorship as you understand it. This is digital isolation. It's a different animal entirely. And traditional tools like VPNs? They might not stand a chance against it.

Let me walk you through what's actually happening, why it matters beyond Iran's borders, and what the broader implications are for internet freedom worldwide.

The Scale of What's Coming

When Iran killed the internet for 40 million people in 2022, it made headlines. The protests that sparked the blackout were triggered by the death of Mahsa Amini in police custody. But what actually made the regime nervous wasn't just the protests themselves. It was how they were coordinated. Through encrypted apps. Through VPNs. Through the uncensored internet.

The regime learned a hard lesson: as long as Iranians could access the global internet—even with difficulty—they had a lifeline. A way to organize. A way to see information the government didn't control. A way to communicate without surveillance.

So they decided to build a solution. Not a firewall. A wall.

The National Information Network, also called the Halal Internet, is Iran's answer to complete digital control. The basic architecture is this: a separate, parallel internet owned and operated entirely by Iran's government. Inside it: state-approved services, state-approved content, state-approved everything. Outside it: nothing you can access.

This is different from the Great Firewall of China, though they share DNA. China's firewall still connects to the global internet. It blocks and monitors traffic. But it can be circumvented. VPNs work there. Tor works there (sometimes). There are cracks in the wall.

Iran's proposed system doesn't have cracks. It has an off switch.

How a National Intranet Actually Works

Imagine the internet, but smaller. Closed. Every website runs on Iranian servers. Every email gets routed through Iranian infrastructure. Every data connection stays inside Iran's borders. You can't access Google because Google doesn't exist in this network. You can't reach your cousin in Toronto because international connectivity is… not available.

The technical implementation requires hardware at the border. Deep Packet Inspection (DPI) equipment that examines every piece of data leaving or entering Iran. Routers that only allow approved destinations. BGP (Border Gateway Protocol) configurations that blackhole any attempt to reach foreign servers.

Here's the thing that makes this different from a regular censorship system: you can't bypass it with encryption. Encryption hides what you're doing. It doesn't change where you're doing it. When your connection tries to reach a server outside Iran, the DPI equipment sees the attempt itself. It doesn't need to decrypt your traffic. It just refuses the route entirely.

A VPN might hide your traffic from ISPs. But if the ISP's entire routing infrastructure refuses to route to the destination you're trying to reach, the VPN's encryption doesn't matter. You're still blocked. The VPN can't create a route that doesn't exist.

The Iranian government has been testing this for years. They've run trial blackouts. They've practiced disconnecting from international internet backbones. They've built redundant internal infrastructure so a disconnection doesn't crash their own systems.

They're serious about this. And they're almost ready.

The Immediate Casualties: What Iranians Lose

Let's get concrete about what happens when you disconnect a country of 89 million people from the global internet.

First: communication collapses for anyone with family outside Iran. WhatsApp? Gone. Telegram? Gone. Facebook Messenger? Gone. Video calls? Theoretical. Your cousins in the diaspora don't get to video call their kids' grandparents. Families that have been separated by emigration, by asylum, by work, lose their connection thread.

Second: access to knowledge vanishes. No international news sites. No foreign universities' online libraries. No Wikipedia (the actual Wikipedia). No Google Scholar for researchers. No access to global scientific databases. Iranian students competing internationally? They start from a disadvantage no VPN can overcome. They can't read the research their peers are reading.

Third: economic friction multiplies. Global payment systems stop working. International banking becomes nearly impossible. Small business owners selling goods on Etsy? No platform. Freelancers working for Western companies? Communication breaks. You lose access to tools like Stripe, PayPal, international escrow services. Remote work becomes theoretical.

Fourth: surveillance becomes inescapable. In the current system, at least Iranians can access encrypted communications platforms. Telegram, despite repeated attempts to block it, still functions through workarounds. Signal gets through. Inside a national intranet? Every service is government-run. Every message is logged. Every search is recorded. There's no privacy available at all.

Fifth: innovation gets a cage. You can't build a startup that relies on cloud services. You can't use GitHub. You can't access npm packages from the public registry. You can't integrate with AWS. You can't tap into the global open-source ecosystem. Iranian developers, once connected to the global tech community, get isolated.

These aren't abstract losses. These are daily friction. Accumulated pain. For millions of people.

Why VPNs Can't Fix This

Here's where a lot of analysis goes wrong. People think about VPNs as tools that hide traffic. Make it encrypted. Route it through a different country. And sure, that works great against ISP-level monitoring.

But VPNs can't solve a routing problem.

When the Iranian government implements the National Information Network, they're not just monitoring traffic. They're controlling where that traffic can go. At the border level. At the physical infrastructure level.

Let's say you're in Iran with a VPN enabled. Your connection tries to reach a VPN server in Singapore. That traffic has to physically leave Iran's borders. It does that through undersea cables, through land routes, through specific chokepoints that Iran's infrastructure controls.

The DPI equipment at those chokepoints doesn't need to see inside your encrypted tunnel. It just sees: "This packet is leaving Iran. This packet is trying to reach a non-approved destination. Block it."

The VPN never connects. The tunnel never forms. You're disconnected before the encryption even matters.

Some analysts suggest using obfuscation protocols like those used in Tor. Shadowsocks. V2Ray. Making the VPN traffic look like regular HTTPS traffic or other innocent protocols. But here's the problem: Iran has had years to study these techniques. They've watched how activists in other countries use obfuscation. They've tested defenses against it. And more importantly, they're building infrastructure from the ground up specifically designed to prevent exit to the global internet.

Obfuscation might have worked five years ago, when Iran's technical capacity was lower. Now? They have teams of engineers designing systems specifically to counter these tools. They're not starting from zero.

The Government's Justification (And Why It's a Smokescreen)

Iran's government frames this as security and self-sufficiency. The narrative goes: Iran shouldn't depend on foreign tech companies. Iran shouldn't be vulnerable to international sanctions that target internet infrastructure. Iran should build indigenous technology and control its own digital destiny.

There's actually a grain of truth buried in there. Iran did get hit hard by sanctions. Iranian banks can't easily connect to international payment systems. Sanctions pressure is real. The 2022 internet blackout was partly a response to that anxiety.

But let's be honest about what's really happening. The government isn't building a national intranet because it's worried about economic independence. It's doing it because it can't control a connected population. Every protest, every moment of resistance, is coordinated through apps the government can't see into. Through communities the government can't monitor. Through information the government can't shape.

A truly independent internet wouldn't require disconnection. It would just require local alternatives to global platforms. But that's not what they're building. They're building a total surveillance infrastructure dressed up as independence.

Consider what happens next: once the intranet is complete, every website runs on servers the government owns. Every ISP is state-controlled. Every router logs everything. The government doesn't just know what you're accessing. It knows when, how long, what you looked at, and can correlate that with location data and phone records.

There's nowhere to hide. Not technically. Not really.

How Iran Tested the Plan (And Nearly Broke It)

Iran didn't wake up one day and decide to build a national intranet. It was forced into this path through a series of escalations.

2009: Green Movement. Protesters coordinated through Twitter. The government was shocked at how effectively information moved through the network it couldn't control. First response: blocking websites.

2012-2014: Turmoil. Sanctions hit hard. Internet infrastructure degraded. The government ran experiments with selective disconnections. They discovered that total blackout was possible but economically devastating. They needed something more surgical.

2019: Fuel Protests. The government tried a temporary national blackout. Shutting down internet for hours to days killed the protests but created economic havoc. Banks couldn't process transactions. Hospitals couldn't access records. Businesses ground to a halt.

2022: Mahsa Amini. The full blackout lasted almost a week. The government learned that it could control a population this way, but the cost was enormous. Loss of tax revenue. Loss of economic productivity. International embarrassment.

So they started building the alternative: a parallel internet that's functional (so the economy keeps running) but isolated (so political organization becomes impossible).

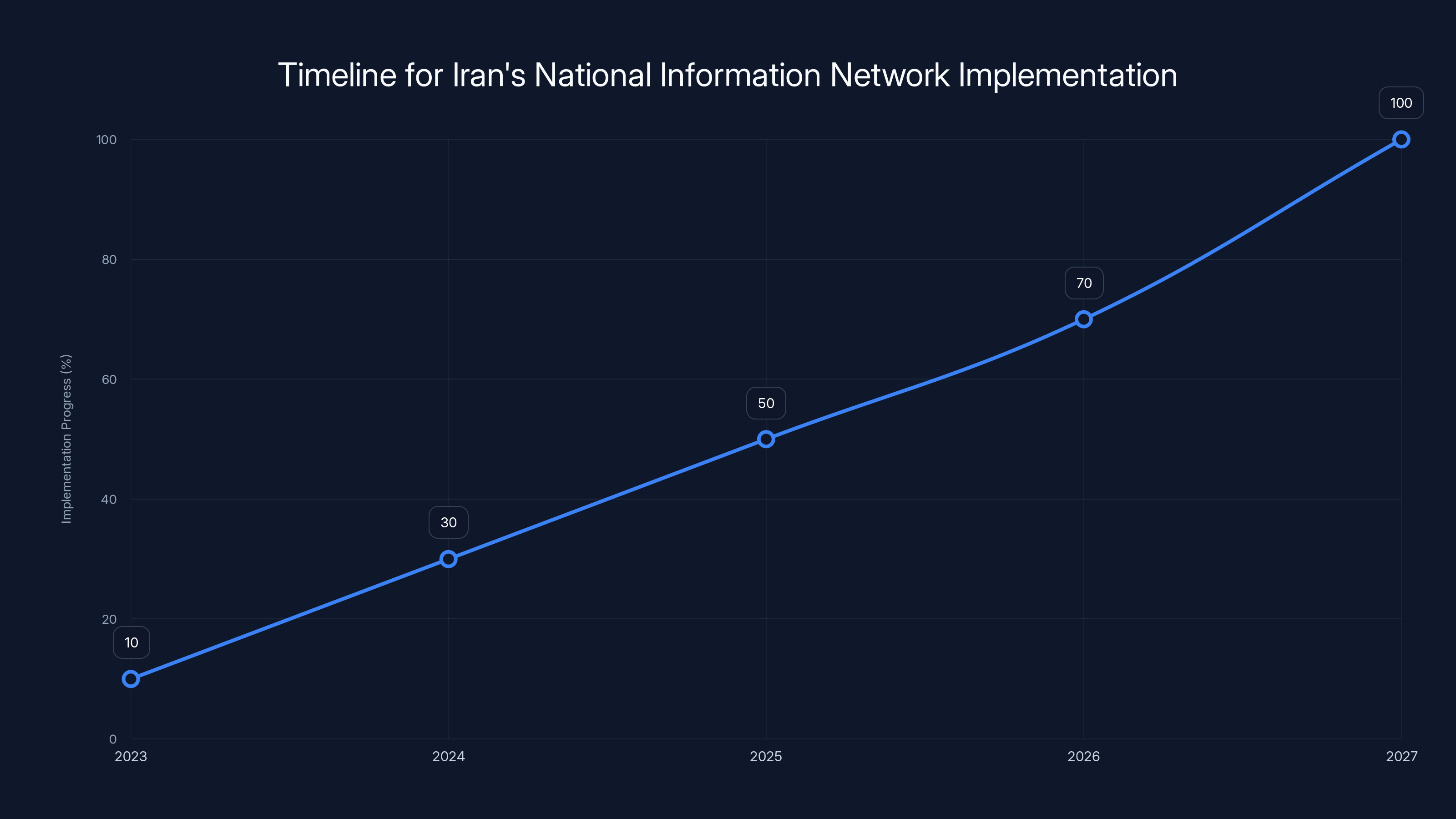

They're not done. The National Information Network is still in development. Estimates suggest 2024-2026 for partial implementation, with full rollout taking years. But pieces are already in place.

What Happens to the Global Internet Structure

Here's what doesn't get enough attention: if Iran successfully implements a national intranet, it doesn't just affect Iranians. It changes the internet architecture itself.

Iran sits on major internet backbone routes. Fiber optic cables that connect Europe to Asia pass through Iranian territory (or close to it). If Iran completely disconnects, traffic reroutes. New cables get laid. Alternative pathways get reinforced.

It's like a river suddenly being blocked. The water has to find another way around. And that costs money. It creates inefficiencies. It fragments the internet into distinct regions.

China already demonstrated this is possible. Despite heavy censorship, China remains connected to the global internet. But if more countries follow Iran's model—actually disconnecting rather than just filtering—you start seeing a fundamental shift in internet architecture. A fragmented, regionalized internet instead of a truly global one.

This is the Splinternet scenario. Multiple internets. The Western internet. The Chinese internet. The Russian internet. The Iranian internet. They barely communicate. Information stops flowing between regions. The "World Wide" Web becomes a collection of closed networks.

That's a massive shift in how the internet works. And once that precedent is set, other authoritarian governments will copy it. If Iran can build a functional isolated internet, so can Russia. So can Venezuela. So can others.

The global internet was built on the assumption of connectivity. Openness. Networks linking to networks. A national intranet model breaks that assumption. And once enough countries do it, the internet as we've known it effectively ends.

The Human Cost: Lives Disrupted

Let's zoom in on specific people, because statistics sanitize what's actually happening.

Maryam is a researcher at Tehran University. She specializes in climate science. Most current climate research is published in international journals behind paywalls. She accesses them through institutional access and ResearchGate, a global network. Under a national intranet, she can't. Her university can't subscribe to these journals in a disconnected network. She loses access to the field she studies.

Reza is a web developer in Tehran. He freelances for companies in Europe. He uses GitHub for code sharing. He uses npm to pull in open-source packages. He uses Stack Overflow when he gets stuck. All of that is off the table in a national intranet. His income source evaporates unless he can find local clients, which are rare in a disconnected market.

Nasrin is 16. She's on TikTok, where she watches educational content in English. She's teaching herself programming through YouTube tutorials. She communicates with friends globally. A national intranet doesn't just isolate her from entertainment. It cuts her off from education. It limits her options in life.

Kaveh is gay. He can't live openly in Iran due to harsh laws. He uses encrypted apps to communicate with a support community online. It's not ideal, but it's a lifeline. A national intranet means that lifeline disappears. The isolation becomes total.

These aren't edge cases. Millions of Iranians have adapted to the censored internet by learning workarounds, finding global communities, accessing information through cracks in the system. A truly isolated national intranet closes all those cracks at once.

The human cost is enormous. And it's intentional.

Precedent: What China Teaches Us

China's approach to internet control is often cited as a model. And in some ways, Iran is learning from China. But there are crucial differences.

China's Great Firewall filters traffic but doesn't disconnect completely. Chinese internet users can technically access the global web, but it's blocked. Slow. Monitored. In practice, most Chinese internet use happens within Chinese borders.

But it's not a hard disconnect. VPNs work in China (sometimes). Tor works (sometimes). There are vulnerabilities. Cracks. Over decades, Chinese citizens and international activists have developed workarounds.

Iran's proposed system goes further. It's not a firewall. It's a border. You can't circumvent a border by routing around it. If the border doesn't allow international traffic, you're stuck.

Russia, after 2022, moved toward the Iranian model. Building domestic infrastructure. Planning for potential disconnection. Reducing dependency on international services. It's a slower process than Iran's, but the direction is the same.

What makes Iran's approach different is speed and urgency. China spent decades building its Great Firewall. Iran is trying to do it in 2-3 years. That creates security vulnerabilities. Rushed systems have bugs. Gaps. But it also shows how serious the government is.

What This Means for Digital Rights Globally

If Iran succeeds in building a functional national intranet, it proves something to every authoritarian government on Earth: you don't have to tolerate a connected internet.

For decades, the assumption was: internet connectivity requires global connection. You can't have a modern economy without being plugged into the global internet. Trade requires it. Banking requires it. Communication requires it.

If Iran builds a fully functional parallel internet, it breaks that assumption. Your population can still do banking. Still do some commerce. Still do basic online services. Everything happens within your borders. Your government has total control.

That's not an argument for why it's a good idea. It's a warning about why other governments will copy it.

Venezuela might try. Myanmar's military government might consider it. Pakistan during political crises might test it. Russia might accelerate its plans. The model is now proven possible.

And the implications for digital rights are catastrophic. Right now, digital freedom advocates can appeal to international standards. Internet openness. Freedom of information. But if countries can functionally disconnect without destroying their economy, those arguments lose force.

They lose force because economic pressure stops working. When a country disconnects from the global internet, international sanctions on digital services don't matter. You can't sanction a service that doesn't exist in your country.

VPN companies can't help. Tor can't help. Any tool that relies on accessing the global internet becomes useless. And repression becomes impossible to resist through technical means.

This is the future of digital control. Not constant surveillance (though that's part of it). Not blocking specific content (though that's part of it). But physical disconnection masked as independence.

The Practical Reality: Building a National Intranet

Let's talk about the actual technical challenges Iran faces. Because implementing a national intranet is harder than it sounds.

First, the infrastructure. Iran needs to replicate major internet services. Not just copy them. Actually build versions that work at scale. Gmail competitors. YouTube competitors. Google competitors. Banking systems. E-commerce platforms. All of it has to be built domestically. That's not a trivial engineering challenge.

Second, transition complexity. You can't just switch off the global internet. Too much would break. Instead, you do a gradual transition. Slowly disconnecting from global networks while bringing local services online. That process could take years. And it's a window where tech-savvy Iranians might migrate data, back up critical information, or move their lives to other countries.

Third, international pressure. Cutting off a country of 89 million people creates international pressure. Humanitarian concerns. Economic sanctions. Diplomatic isolation. The government has to decide if that pressure is worth the control gain.

Fourth, technical talent drain. Once the intranet is built, skilled engineers and tech workers will leave. Why stay in a country where you can't use global tools? Can't collaborate internationally? Can't access the latest technologies? The people most capable of maintaining the system are the most likely to emigrate.

Fifth, economic cost. Building this infrastructure costs billions. Maintaining it costs billions. And it probably doesn't fully replace global connectivity's economic benefit. There's a real cost-benefit analysis happening inside the Iranian government.

But here's the thing: for a government focused on control, that cost might be worth it. The economic hit might be acceptable if it means the government survives the next wave of protests.

The Looming 2024-2026 Timeline

Based on public statements from Iranian officials and infrastructure projects that have been announced, the National Information Network is moving toward implementation faster than most analysts expected.

Early phases are already underway. Government services are being moved to domestic servers. Banking systems are being tested on intranet-only infrastructure. Content delivery networks are being built domestically to cache copies of approved content.

By late 2024, we expect significant portions of Iranian internet to be segregated. Government services operating on the intranet. Critical infrastructure disconnected from the global web.

By 2025-2026, expect the ability for Iran to execute a near-total disconnect if needed. Not a controlled blackout. A strategic migration to a closed system.

That doesn't mean it happens immediately. The government will probably do trials. Test disconnections of specific sectors. See what breaks. Fix it. Gradually expand the scope.

But the window for Iranians to prepare is closing. Once the intranet is built and tested, the option to keep the internet globally connected becomes a political choice, not a technical limitation. And a government that builds this infrastructure almost certainly plans to use it.

What Activists and Ordinary Iranians Are Doing

Despite the grim outlook, there's resistance. Understanding how it works now is important because it reveals what might still be possible.

Decentralized communication. Activists are moving toward peer-to-peer systems. Briar, for example, is a messaging app that works without internet. It uses Bluetooth. It works offline. It's designed specifically for scenarios where the internet is unavailable.

Data preservation. Journalists, researchers, and activists are archiving content before it potentially disappears. Backing up blogs. Recording videos. Downloading papers. Creating offline copies of information that might be deleted from the national intranet.

Diaspora coordination. Iranians abroad are creating infrastructure that allows organizing from outside the country. International networks of resistance. It doesn't fix the isolation problem, but it creates external support.

Technical skill building. Universities and informal networks are teaching basic IT security. Not to circumvent censorship (which becomes impossible), but to avoid identification. To communicate more safely within constraints. To document repression digitally.

None of this solves the fundamental problem. But it creates friction. It makes control harder. It preserves information. It keeps resistance possible even in a scenario where technical tools fail.

The broader lesson: if the internet can be disconnected by governments, then digital resistance has to adapt to a post-internet world. Decentralized. Offline. Mesh networks. Physical dead drops. The tools of digital resistance become the tools of an offline resistance.

The Broader Implications for Internet Freedom

Here's what keeps security researchers up at night: Iran might succeed.

Not instantly. Not perfectly. But over the next 3-5 years, Iran could build a functional national intranet that allows governance, basic economy, and public services while maintaining total government control.

If Iran succeeds, every authoritarian government learns that this is possible. That you can have internet services without having the internet. That connectivity isn't mandatory.

The internet was supposed to be a force for liberation. In theory, it still is. But tools are neutral. A network that connects billions of people can also isolate them. A system designed for freedom can be repurposed for control.

And that's happening now. In real time. In Iran.

The people losing access to the global internet aren't statistics. They're researchers who can't read papers. Students who can't take online courses. Activists who can't coordinate. Families separated by distance and politics who can't communicate. Ordinary people who used the internet to make their lives better in whatever small ways were available to them.

VPNs can't save them. Tor can't save them. Technology can't save them. Because the problem isn't encryption. It's not routing. It's the removal of the route itself.

What might save them is sustained international pressure. Economic consequences for the government. Technical support from other countries. But honestly? If Iran's government decides control is worth the cost, technology alone can't stop it.

What You Should Know Before This Becomes News Again

Iran's digital isolation isn't coming. It's already here. It's being built. It's being tested. And the people in charge are open about it.

When the next major disruption happens, when the next blackout or disconnect occurs, people will be surprised. They shouldn't be. The pieces are in place. The infrastructure is being built. The government has made clear what's coming.

What happens in Iran matters beyond Iran. Because if it works, others will copy it. And the internet as a global, connected system will fragment into isolated networks controlled by individual governments.

That's not inevitable. It requires continued investment by Iran's government. It requires international conditions that allow disconnection. It requires technology that works (which is harder than it sounds).

But it's not impossible. And the window to prevent it is closing.

The internet gave billions of people something they didn't have before: connection. Access. Information. Community across borders. In Iran, and potentially elsewhere, that's being deliberately dismantled.

Understanding why VPNs won't help matters. Understanding the technical reality matters. Understanding what's actually being built matters. Because only then can people prepare. Plan. Adapt. Resist.

The future of internet freedom isn't being decided in Silicon Valley. It's being decided in government buildings in Tehran. And ordinary people need to understand what's happening before they lose the ability to do anything about it.

TL; DR

- Iran is building a National Information Network: A separate, isolated internet completely disconnected from the global web, designed to give the government total control and eliminate ways for the population to coordinate resistance.

- VPNs won't work: Traditional VPN encryption hides traffic, but it can't solve a routing problem. If the government's infrastructure refuses to route data to foreign servers, encryption doesn't matter—the connection simply never forms.

- This is different from censorship: China's Great Firewall filters traffic but keeps connectivity. Iran's model completely disconnects. There are no cracks to exploit. No borders to route around.

- The human cost is enormous: Researchers lose access to global journals. Freelancers lose clients. Students lose educational resources. Families lose the ability to communicate. Activists lose coordination tools. Everyone loses privacy.

- If Iran succeeds, others will copy: This proves to every authoritarian government that you can have internet services without global connectivity. It could trigger a fragmentation of the internet into isolated regional networks.

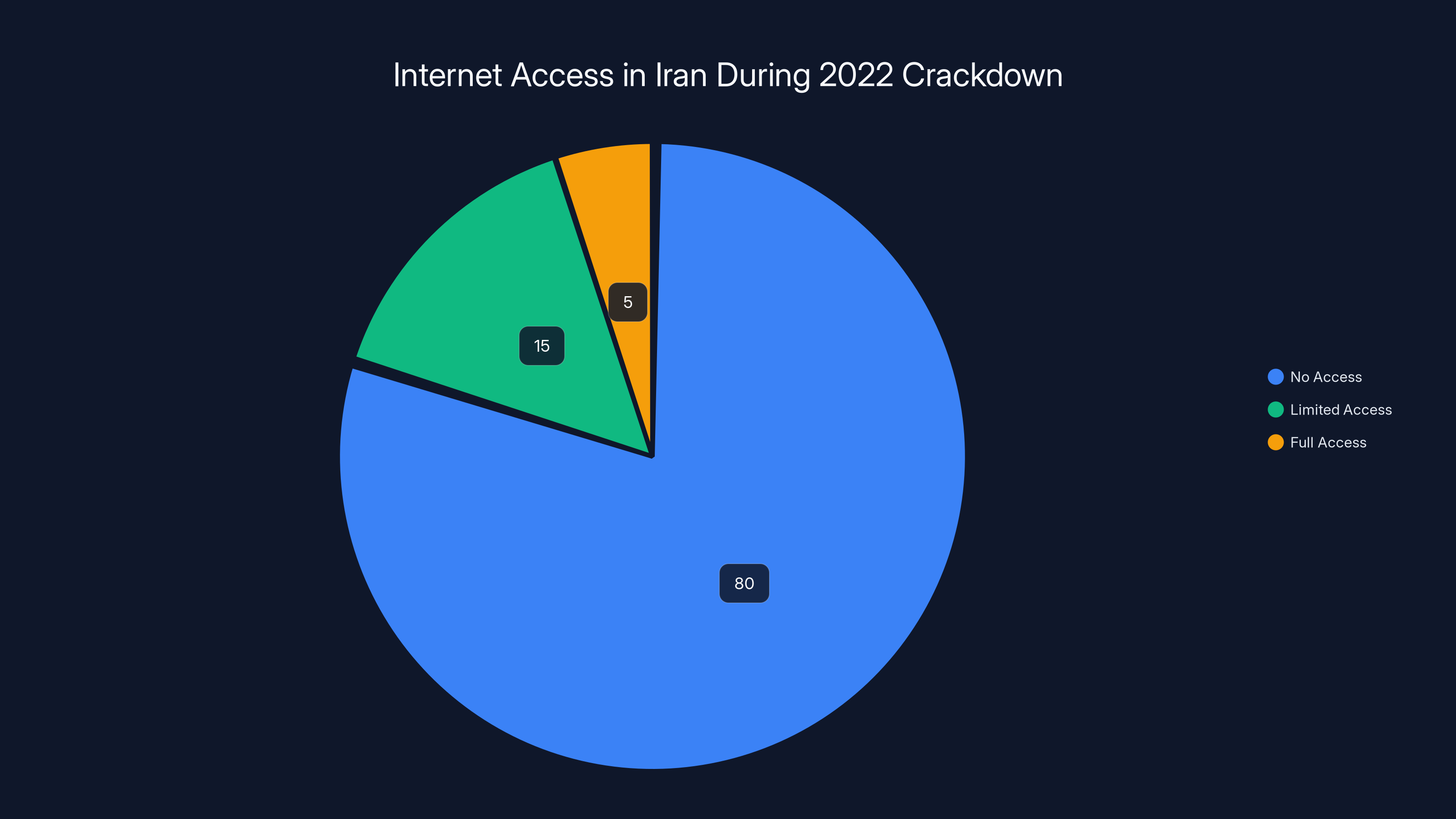

During the October 2022 internet blackout in Iran, an estimated 80% of the population had no access to the internet, highlighting the regime's capability to enforce digital isolation. Estimated data.

FAQ

What exactly is Iran's National Information Network?

Iran's National Information Network, sometimes called the "Halal Internet," is a planned parallel internet owned and operated entirely by the Iranian government. Instead of connecting to the global internet, it would be a closed system with government-approved websites and services. Everything stays within Iranian borders. Nothing connects internationally. The government envisions having domestic versions of email, search engines, social media, and banking.

How does Iran plan to enforce a complete internet disconnect?

Iran would use Deep Packet Inspection (DPI) equipment and router configurations at national borders to examine and block all data attempting to leave the country. Unlike censorship that filters specific content, this approach prevents traffic from even attempting to reach foreign servers. The infrastructure simply refuses the route. This makes it fundamentally harder to circumvent than traditional censorship.

Why wouldn't a VPN work in this scenario?

VPNs encrypt traffic and route it through external servers, which works when the infrastructure allows international connections. But if Iran's border routers refuse to allow any traffic to reach foreign servers—encrypted or not—the VPN connection can't form in the first place. The encryption becomes irrelevant because the route is blocked before encryption even matters. VPNs solve surveillance problems, not routing problems.

What's the timeline for Iran's implementation?

Partial implementation is expected between 2024 and 2026, with government services already being migrated to domestic servers. Full implementation would likely take longer, involving a gradual transition rather than an instant switch. The government is testing pieces of the system now and will probably conduct trial disconnections of specific sectors to work out technical problems before going fully operational.

How would this affect ordinary Iranians' daily lives?

Iranians would lose access to most international services: no global social media, no international banking, no foreign universities' resources, no global communication apps, no access to international news sources. Researchers lose academic journals. Freelancers lose international clients. Families with members abroad lose communication options. Everyone experiences total surveillance of their online activity since every service would be government-run.

Could Tor or other anonymity tools help?

Tor exit nodes are based outside Iran. If the border routers refuse to allow traffic to reach external Tor servers, Tor connections can't form either. Obfuscation tools like V2Ray or Shadowsocks might have slightly more resistance since they can disguise traffic as regular HTTPS, but Iran's government has spent years studying these techniques and is building infrastructure specifically designed to counter them. Over time, as the system matures, these workarounds would likely become less effective.

What happens if Iran successfully builds this system?

It would prove to every authoritarian government that a functional national intranet is technically possible. Other countries would likely copy the model. Russia has already begun building similar infrastructure. The result could be a fragmented internet split into isolated regional networks controlled by individual governments, which would fundamentally change how information flows globally and eliminate the internet as a unified global system.

Are there any technical challenges that might stop Iran from implementing this?

Yes. Building alternative services for 89 million people is expensive and complex. Transitioning without breaking the economy is difficult. Tech talent will emigrate. Maintenance costs are substantial. International sanctions could complicate infrastructure. But from the Iranian government's perspective, these costs might be worth the control gained. The real question isn't whether it's technically possible—it is—but whether the government will bear the political and economic costs.

What can Iranians do to prepare or resist?

Activists are already using decentralized tools like Briar that work offline or via Bluetooth. Journalists and researchers are archiving information before potential disconnection. People are building technical skills for offline resistance. Iranians abroad are coordinating external support networks. But honestly, technical tools have limits. The best preparation is data preservation, skill-building, and maintaining international connections while they still exist.

Iran's National Information Network is expected to reach full implementation by 2027, with partial implementation starting in 2024. Estimated data based on projected plans.

Future Outlook: What Comes Next

The trajectory is clear. Iran's government sees digital isolation as a solution to its control problem. The infrastructure is being built. The timeline is accelerating. The technology is mature enough to work at national scale.

Within 3-5 years, Iran could have a fully functional alternative to global internet connectivity. That's not a distant future scenario. That's next-decade planning that's happening now.

The question isn't whether Iran will try. It's whether they'll succeed, and what happens globally if they do.

Because the internet you know—the connected, open, global network—might be the internet's adolescent phase. The experimental period before governments figured out how to control it. Once that control becomes technically feasible and politically acceptable, the internet fragments. Pieces break off. Regional networks form.

Iran might be the first domino. Or it might not. But the model is proven. The path is clear. And the rest of the world is watching.

Key Takeaways

- Iran is building a National Information Network—a completely separate, government-controlled internet disconnected from the global web by 2024-2026, with partial implementation already underway

- VPNs cannot bypass border-level routing blocks. Encryption hides content but can't solve infrastructure-level refusal to route traffic to foreign destinations

- This model differs fundamentally from China's Great Firewall: it's total disconnection rather than traffic filtering, eliminating any technical circumvention routes

- An isolated national intranet enables total government surveillance while allowing basic economic function, creating unprecedented control over a population

- If Iran succeeds, other authoritarian governments will copy the model, potentially fragmenting the internet into isolated regional networks and fundamentally changing global information flow

Related Articles

- Russia's VPN Crackdown 2026: New Laws & Blocking Tactics [2025]

- UK Pornhub Ban: Age Verification Laws & Digital Privacy [2025]

- Pornhub's UK Shutdown: Age Verification Laws, Tech Giants, and Digital Censorship [2025]

- Pegasus Spyware, NSO Group, and State Surveillance: The Landmark £3M Saudi Court Victory [2025]

- Best VPN Services 2025: Tested, Reviewed, and Ranked [2025]

- Meta Blocks ICE List: Content Moderation, Privacy & Free Speech [2025]

![Iran's Digital Isolation: Why VPNs May Not Survive This Crackdown [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/iran-s-digital-isolation-why-vpns-may-not-survive-this-crack/image-1-1769621942826.jpg)