Building a Winning Founding Team: VC's Essential Playbook

You're sitting in a coffee shop with an idea that won't leave you alone. You've validated it with potential customers. The market timing feels right. But now comes the hardest part: who do you want to build this with for the next five to ten years?

This decision matters more than your initial product, more than your first round of funding, and arguably more than your business plan. The founding team you assemble sets the cultural foundation, hiring standards, and risk tolerance that will shape your company for years to come. Get this wrong, and you'll spend the next eighteen months untangling misaligned incentives, equity disputes, and cultural friction. Get it right, and you've got a force multiplier that can accelerate growth exponentially.

Venture capitalists see hundreds of teams every year. They watch which ones succeed spectacularly, which ones slowly implode from internal conflict, and which ones plateau because the founding team can't scale themselves. The patterns are remarkably consistent. Yet most founders make the same mistakes their predecessors did, often because nobody told them what to actually optimize for when assembling a team.

This guide distills the most valuable lessons from experienced investors about founding team composition, equity allocation, hiring strategy, and compensation design. These aren't theoretical frameworks pulled from business school case studies. These are patterns that separate the companies building market-defining products from the ones that eventually sell for acqui-hire prices.

TL; DR

- Investor quality matters more than check size: The best VCs help you recruit, go-to-market, and build culture, regardless of how much they invest

- Equity splits should hedge future misalignment: Use a slight plus-or-minus one share structure to prevent deadlocks and future resentment

- First hires must be missionaries, not mercenaries: They're joining for equity upside and mission belief, not just salary

- Communication about risk is non-negotiable: Be honest with early employees about failure odds and what that means for their financial future

- Founding team sets the hiring bar forever: Your first five to ten employees establish standards for quality, values fit, and work ethic that are nearly impossible to change later

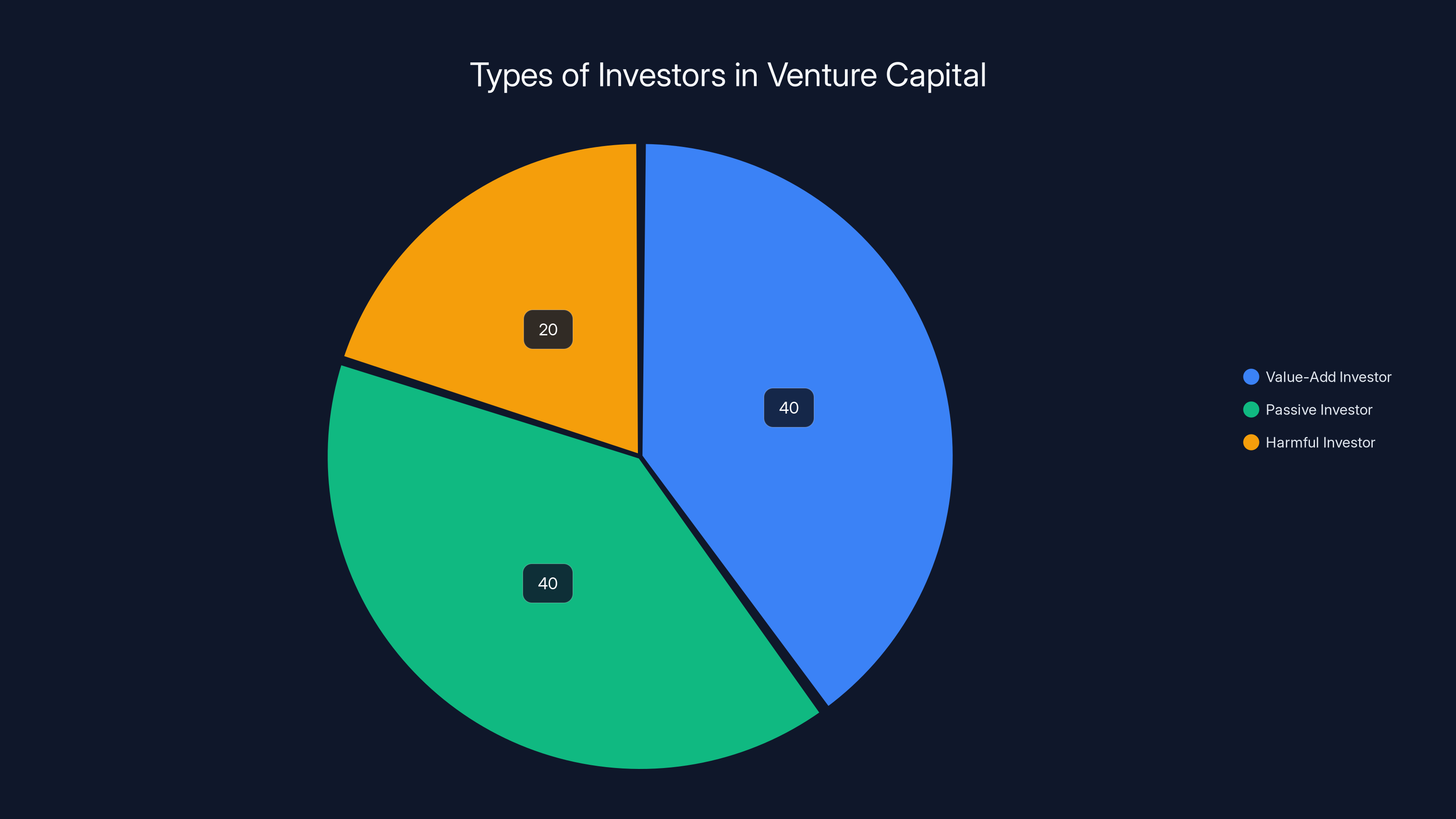

Estimated data suggests that Value-Add and Passive Investors each make up approximately 40% of the venture capital landscape, while Harmful Investors constitute about 20%.

The Most Consequential Decision You'll Make as a Founder

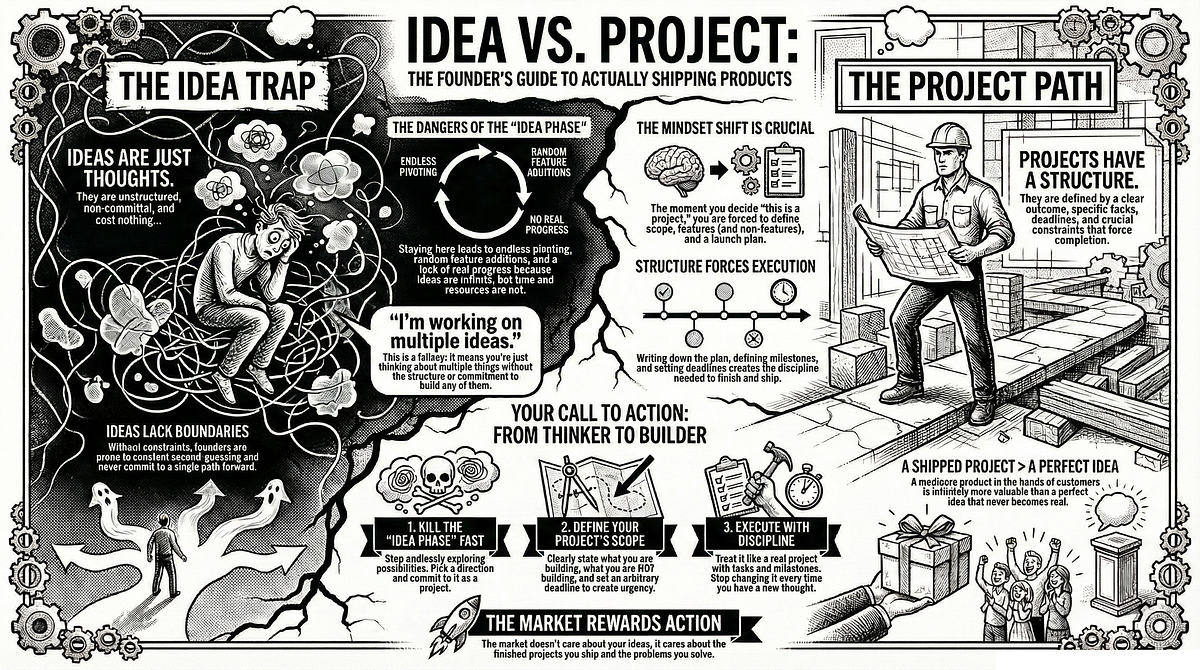

When most founders think about the early days, they obsess over product-market fit. They stress about runway. They worry about whether their first customers will renew. These concerns matter, but they're downstream from a more fundamental decision: who's going to help you solve these problems?

Your founding team isn't just your co-founders. It's your first five to ten employees. These people will shape your engineering practices, hiring culture, product philosophy, and how you handle crisis. A single bad early hire can set a precedent that's remarkably hard to reverse. When you hire someone unqualified because you're desperate, the next manager thinks that's the bar. When you hire someone toxic because they're technically brilliant, your best people notice and leave. When you hire someone misaligned on values, they'll eventually recruit people who match their priorities, not yours.

Conversely, the right early team compounds every other decision you make. They'll recruit better people because they understand your standards. They'll challenge your product decisions in constructive ways. They'll stay through the difficult middle phase of the company when growth stalls temporarily. They'll refer their networks when you're raising capital.

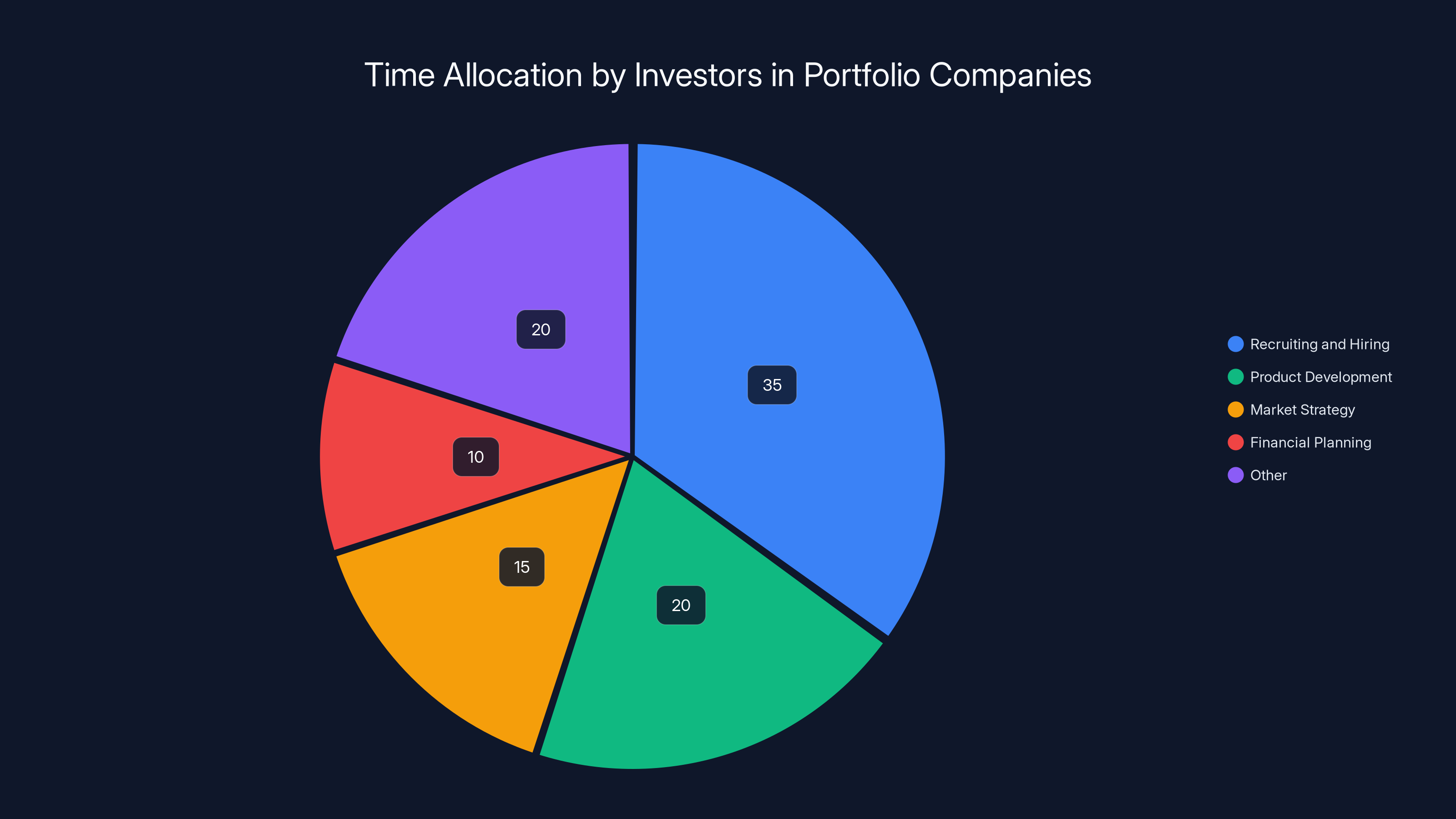

Investors spend roughly thirty to forty percent of their time helping portfolio companies with recruiting and hiring. This isn't because investors love HR. It's because getting the team right is the primary determinant of success or failure. Everything else flows from team quality.

Why Your Founding Team Matters More Than Your Idea

There's a phenomenon in venture that gets discussed in hushed tones among partners: how many successful companies exist that technically have "worse" ideas than the companies that failed. Airbnb's core idea was "trust strangers with your apartment." That sounded insane in 2008. Yet the team was exceptional, and they built product-market fit that made the idea work. Snapchat's disappearing messages seemed gimmicky compared to competitors with richer features. The team's execution and design vision proved the skeptics wrong.

Meanwhile, there are countless examples of founders with genuinely great ideas, clear market demand, and solid early metrics who failed because the team couldn't execute at the required velocity. They hired too slowly when they needed to move fast. They hired too quickly and brought in people who slowed everything down. They assembled a team where half wanted to build long-term and half wanted to flip the company in five years.

The team compounds over time. A great team with an okay idea will iterate to a great idea. A mediocre team with a great idea will either fail or sell early. This is why VCs can often tell whether a company will succeed within the first thirty minutes of meeting the founding team. Not because the idea is obviously great, but because the people have demonstrated they can learn, adapt, execute, and collaborate under pressure.

The Hidden Cost of Team Misalignment

You've probably heard the statistic that approximately fifty percent of startups fail due to team conflict. That number sounds high, but it's actually conservative. Most startups that fail to "team conflict" technically fail for product reasons, fundraising reasons, or market reasons. But zoom in, and you'll find team dysfunction at the root.

A founder with a clear vision but a co-founder who wants to take a different approach wastes mental energy on internal politics instead of external execution. An engineer who doesn't believe in the product ships features half-heartedly. A head of sales who disagrees with the pricing strategy won't evangelize it to customers. These aren't dramatic failures. They're slow bleeds where everyone's effort is partially nullified by internal friction.

The cost compounds because each layer of misalignment makes it harder to hire the next level of talent. Great people want to join companies where they trust leadership and believe in the mission. When there's obvious dysfunction at the founding team level, the best candidates smell it and take other opportunities.

Investors dedicate approximately 35% of their time to recruiting and hiring, highlighting the critical importance of building the right team. Estimated data.

Choosing the Right Co-Founder: It's Not About Your Friend

The conventional wisdom says start companies with people you trust. That's incomplete advice. You need to trust them, but trust isn't sufficient. You need to trust them to do this specific thing at this specific stage of the company.

The co-founder relationship is arguably the most important partnership in your life during the company's early years. You'll spend more time with them than your spouse. You'll make decisions that affect both of your net worth together. You'll argue about strategy, hiring, product direction, and values. You'll experience periods of doubt where one founder's belief props up the other. You'll celebrate wins together and suffer through losses together.

This relationship needs to be built on three foundations: complementary skills, aligned values, and proven ability to work together.

Complementary Skills, Not Identical Talents

The worst founding team composition is two people with identical skill sets and perspectives. If you both are product people, who's building the go-to-market strategy? If you both are engineers, who's talking to customers and raising capital? If you both have identical risk tolerance, who asks hard questions about whether you're taking too much risk?

The best teams have founders where each person has deep expertise in different domains, but enough overlap that they can evaluate and challenge each other's thinking. A technical co-founder should know enough about business and sales to understand why you're making certain product decisions. A business-focused founder should know enough about technology to understand technical debt and engineering velocity. This overlap creates the ability to truly collaborate instead of just dividing and conquering.

Complementary doesn't mean opposite. It means different primary strengths. A common pattern in successful startups is a product-focused founder and a distribution-focused founder. A technical founder and a business founder. An operator and a visionary. These pairings work because neither person can succeed alone, so they're incentivized to make the partnership work.

Aligned Values, Especially About Ambition and Risk

Skills can be learned or hired. Values either align or they don't. This is where most founder partnerships break down. One founder views the company as a lifestyle business that will generate comfortable income. The other views it as a potential category-defining opportunity that requires aggressive risk-taking. One founder wants to maximize profit margins. The other wants to spend aggressively on product quality and team culture.

These value misalignments don't matter when the company is small and growing. Everyone's too busy to think about the long-term philosophical differences. They become catastrophic once the company has some traction. Suddenly, the lifestyle founder is pushing to take profits or be acquired. The ambitious founder wants to raise a Series B and continue scaling. What was a philosophical difference becomes an irreconcilable conflict with significant financial implications.

The way to screen for value alignment is to have explicit conversations about your long-term vision. Not some vague vision statement for the company. Your personal vision. What does success look like? Would you be happy with a fifty-million-dollar exit? Do you want to build the next hundred-billion-dollar company? Are you willing to fail, or do you need a backup plan? How important is work-life balance? How much financial runway do you need before you start to panic?

These conversations feel vulnerable. That's exactly why you need to have them. If you can't be honest about your ambitions and concerns with a co-founder, you shouldn't be co-founders.

Proven Ability to Work Together

Complementary skills and aligned values are necessary but not sufficient. You also need demonstrated evidence that you can actually work together. This means you need a track record of collaboration, ideally in a high-pressure context.

The best co-founder relationships often come from people who have worked together for years. You've seen how they respond to failure. You know whether they take feedback or get defensive. You understand how they make decisions under time pressure. You've observed whether they care about other people or just their own success.

If you don't have a demonstrated history of working together, create one before you formalize the partnership. Work on a side project for three months. Build a prototype together. Go through a mock-fundraising process. Write a business plan together and argue through the differences. See whether you can disagree, find common ground, and move forward, or whether disagreements become personal.

Many co-founder relationships fail because they're predicated on hypothetical compatibility rather than proven track records. You think you'll work well together based on conversations and interviews. Turns out you have completely different communication styles or decision-making frameworks. By the time you discover this, you've already raised capital, hired a team, and moved to a new city together.

Investor Selection: The Difference Between Helpful and Harmful

Venture capital is not a commodity. Two VCs with the same check size and valuation can have completely different impacts on your company. One will open doors, introduce you to key hires, help you think through go-to-market strategy, and become a trusted sounding board for difficult decisions. The other will periodically check in, offer unsolicited opinions, stress you out when metrics dip, and slow you down with unnecessary feedback loops.

The irony is that the most helpful VCs often aren't the ones writing the biggest checks. There's no correlation between check size and value-add. Some of the most impactful VCs in the ecosystem are known for writing relatively small checks but having disproportionately large influence on their portfolio companies' success.

The Three Types of Investors

Investors generally fall into three categories, and understanding which one you're dealing with is crucial before you take their money.

The Value-Add Investor: This investor views their role as extending their network and expertise to help you succeed. They introduce you to key customers, potential hires, and strategic partners. They help you think through go-to-market decisions. They challenge your assumptions when you're about to make a mistake. Critically, their helpfulness is often disconnected from the size of their check. They're helpful because they view it as their job and because your success reflects on their judgment.

These investors are most valuable during the messy middle phase of company building, when you're no longer riding the wave of early excitement but haven't yet achieved undeniable product-market fit. They're the ones who will listen to your concerns about a key hire who isn't working out and actually help you think through the conversation. They're the ones who'll introduce you to a potential distribution partner when you're stuck on customer acquisition.

The Passive Investor: This investor provides capital and occasionally useful advice, but they're not deeply involved in your company's operations. They took the meeting because they thought the idea was interesting and the team was capable. They expect that you'll keep them updated quarterly, and they'll help if you ask, but they're not going to be proactive about introducing you to people or pushing you to make certain strategic decisions.

Passive investors are fine. They're not problematic. They just aren't going to be a meaningful part of your support system. The value you get from them is the capital itself, not the network or operational experience.

The Meddling Investor: This investor gives you money but then periodically gets "in your kitchen," as one experienced VC puts it. They have opinions on everything. They think your pricing is wrong. They think you should have hired that candidate you rejected. They stress out when metrics dip and question your strategy. They create pressure and friction without providing actual value.

The meddling investor is often the most damaging type, precisely because they're not completely absent. They're involved enough to slow you down but not involved enough to actually be helpful. They create meetings where you're defending your strategy instead of executing it. They plant seeds of doubt. They make phone calls to other investors suggesting the company is off track when you're actually progressing normally.

How to Identify Which Type You're Getting

During the fundraising process, everyone is on their best behavior. Investors are charming, supportive, and full of helpful ideas. You can't reliably distinguish between value-add and meddling investors just by meeting with them. You need to talk to their existing portfolio companies.

Before committing to an investor, explicitly request introductions to their other portfolio companies at similar stages. Then ask the founders some specific questions. What does the investor actually help with? Can you give me a concrete example of how they've been helpful? Can you give me an example of when they pushed back on a decision you made?

Most importantly, ask what they're like when things are going poorly. Investors are great when growth is accelerating and metrics are hitting targets. The revealing question is what they're like when revenue dips by thirty percent, your top engineer quits, or you're struggling to find product-market fit. Do they panic and add pressure? Do they help you think through the challenge? Do they go silent?

The founders who've been through a difficult period with an investor will give you the most honest feedback. They'll tell you whether the investor was a calming presence or whether the pressure made everything worse.

The Subtle Damage of Wrong Investor Selection

Taking capital from the wrong investor doesn't just mean you get less operational help. It can actively slow you down. A meddling investor creates a situation where you're managing their expectations instead of managing your company. You're preparing board presentations that defend your strategy instead of analyzing whether your strategy is correct. You're stressed about disappointing them instead of focused on solving customer problems.

This stress compounds over time. It affects how you think about hiring, because you're worried about making a mistake that the investor will judge. It affects how you approach product development, because you're thinking about what will impress the investor instead of what will impress customers. It affects your fundraising strategy, because you're trying to hit metrics that will convince the investor the company is on track instead of metrics that actually reflect business health.

The subtle damage is that you never actually find out whether your strategy works, because you're constantly adjusting it to manage investor expectations. By the time you realize the investor was wrong about a key decision, you've lost eight months of momentum.

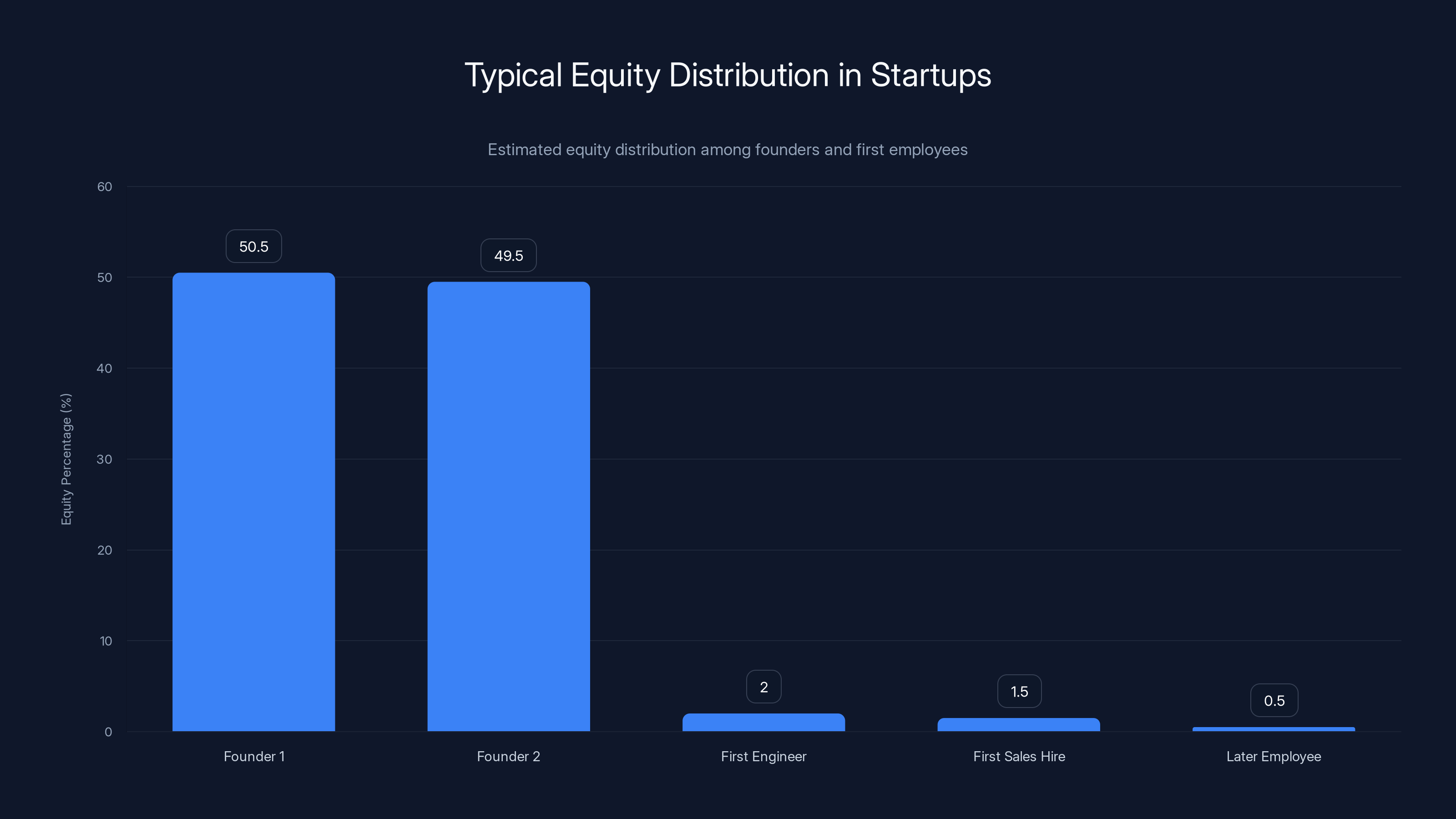

In a typical startup, founders often split equity nearly equally, while first employees receive between 0.5% to 2%, depending on their role and seniority. Estimated data.

Equity Distribution: Setting Up Incentives That Last

Equity is one of the most important levers you have as a founder. It's your way of saying to someone, "I believe in this vision so much that I'm literally giving you ownership." It's also one of the most fraught decisions because it has to work for your company at very different stages: when it's just you and a co-founder with nothing, when you're a fifty-person company trying to hire your next great engineer, and when you're a five-hundred-person company about to go public.

Many founders make equity decisions based on intuition or conversations with other founders, without understanding the second and third-order effects. They give up too much equity early to the wrong people. They don't leave enough room to incentivize the team members who'll actually make the company successful. They create equity structures that look fair at the founding stage but become obviously unfair once the company has some traction.

Co-Founder Equity Splits: Hedging Against Future Misalignment

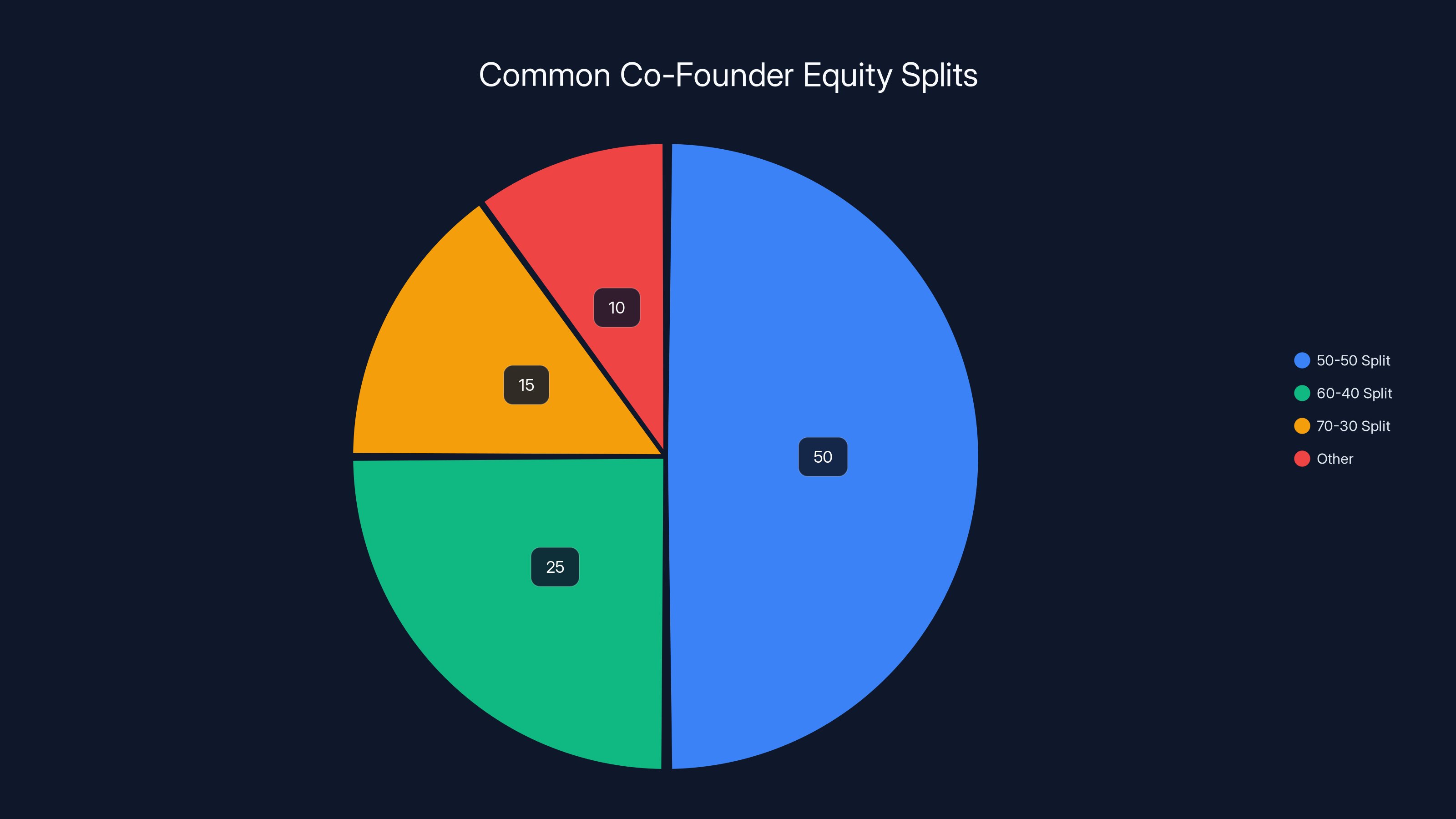

The most common co-founder equity split is fifty-fifty. It's also often the wrong split, not because fifty-fifty is inherently unfair, but because it doesn't account for the reality that companies evolve and people's contributions change over time.

Consider a common scenario: Founder A comes up with the idea and spends three months thinking about it before recruiting Founder B. Founder A feels like they should get sixty-forty. Founder B feels like that's unfair because the real work hasn't happened yet. Idea contribution shouldn't count for much. The split becomes a contentious negotiation right before you're trying to raise capital and hit product milestones.

Or consider this scenario: You and your co-founder are equal partners early on. But over the first two years, one of you becomes much more engaged and the other becomes less involved. Maybe they're dealing with a health issue, or they have a family crisis, or they just lose enthusiasm. But the equity split remains equal, which now feels unfair to the more engaged founder.

The solution that experienced investors recommend is to use a structure that's equal but with a slight plus-or-minus one share differentiation. If you have a hundred shares total, one founder gets 50.5 and the other gets 49.5. Or one gets 60 and the other gets 40. The specific percentages matter less than the principle: there's a clear way to break deadlocks.

This structure acknowledges that both founders are critical (so they're roughly equal) but recognizes that someone needs to be the tiebreaker. It's not about being fair to the person with the extra share. It's about avoiding situations where fundamental disagreements on strategy grind the company to a halt because neither founder can outvote the other.

The Founder Resentment Problem

One of the most insidious problems in founding teams happens five years into the company when a founder realizes they own significantly less of the company than they deserve, relative to the work they've put in. They've been grinding it out since day one. They've given up other opportunities. They've made personal financial sacrifices. And they own fifteen percent of the company because they joined as a "co-founder" but came on a few months after the other two.

This resentment doesn't manifest immediately. It emerges once the company has real value. Suddenly, that fifteen percent feels like a dramatically unfair outcome relative to the contribution. The founder starts asking whether they should be taking their equity to a competitor. They become less engaged. They stop referring candidates they know are qualified. They disengage emotionally from the mission.

The way to prevent this is to have explicit conversations early about what equity means and how it might need to adjust over time. If someone is joining as a co-founder but hasn't been there from the very start, what percentage reflects their contribution relative to the people who were there from day one? How will you handle the scenario where someone's engagement level changes?

Some founders use vesting schedules tied to tenure. Some use performance-based adjustments. Some use conversations every year to check whether the equity split still feels right. The specific mechanism matters less than the principle of being intentional instead of just accepting whatever number felt right at the time.

Early Employee Equity: Enough to Matter, Not Enough to Distract

Your first few hires will own somewhere between one and five percent of the company combined, depending on how many you hire and how you distribute equity. This is enough to matter financially if the company succeeds but not so much that it'll create generational wealth.

The goal is for equity to be meaningful enough that it provides real upside but not so significant that it becomes the primary reason someone joins. You want missionaries who are motivated by equity plus mission. If equity is their primary motivation, you've probably given them too much, because now they're financially incentivized to take shortcuts or rush to an acquisition rather than build the long-term company you envision.

A common pattern is to give early employees between zero-point-five percent and two percent depending on seniority and contribution. For an engineer joining as the first engineer, one to two percent is reasonable. For an operations hire joining when you already have three engineers, zero-point-five to one percent is more appropriate.

The key is consistency. If you give the first engineer two percent and the second engineer one percent, you're signaling that contribution matters and later people will be less important. If you give the first engineer two percent and later employees zero-point-one percent because you "don't want to give away the company," you're creating a situation where later employees don't have meaningful equity upside.

Hiring Your First Five to Ten Employees: Setting the Tone

The recruiting and hiring decisions you make in your first year set a precedent that's remarkably difficult to change. If you hire someone because they're technically brilliant but didn't interview well and won't fit the culture, you're training your hiring team that technical skill overrides culture fit. If you hire someone unqualified because you desperately need to fill a role, you're setting a precedent about the hiring bar.

These precedents compound because each hiring manager was trained by the people who hired them. If the founding team made hiring decisions based on urgency and skill gaps, the first engineering manager will likely do the same. If the founding team was disciplined about culture fit and values alignment, the first engineering manager will inherit that standard.

This is why the hiring philosophy you establish in your first fifty employees will largely determine your hiring quality at five hundred employees. You're not just hiring people. You're creating a training ground for future hiring managers and establishing standards that become the company's default.

Missionaries vs. Mercenaries: What Motivates Early Employees

Your first few employees are taking on enormous risk. The company might fail. They might need to take a significant pay cut relative to what they could make at an established company. They'll work much harder than they would at a larger organization because there are far fewer people and everything needs to get done.

People who take on this risk are fundamentally different from people who join companies that already have established product-market fit and significant capital. The people who join early are either missionaries (deeply motivated by the mission and the potential upside) or mercenaries (primarily motivated by money or title).

Mercenaries are dangerous in early-stage companies because they're not incentivized by the mission. If things get difficult, they have a lower tolerance for adversity because they didn't sign up for the mission anyway. They signed up for compensation. Once they realize the early-stage grind is harder than they expected, they leave.

Missionaries stay through the difficult periods because the mission matters to them. They believe in the problem the company is solving. They might get frustrated with specific decisions or execution, but they don't question whether they should be there.

The way to attract missionaries is to be transparent about both the upside potential and the downside risk. Don't oversell the opportunity. Don't downplay the difficulty. Tell them exactly what you're optimizing for and who you're building this for. Tell them what success looks like if everything goes right, and tell them what failure looks like.

Missionaries are also attracted to founders who seem like they actually know what they're doing, who care deeply about the problem, and who are willing to listen to and learn from the people they hire. If you're genuinely curious about their perspective and willing to adjust your thinking, they'll stay. If you're just looking for people to execute your vision, they'll sense it and leave.

The Recruiting and Sourcing Strategy That Works

Most first-time founders underestimate how hard recruiting is. They think they can post a job and get quality candidates. They think they can rely on job boards. They think they can hire locally because remote work is complicated.

All of these instincts are wrong. The best candidates are not looking at job boards. They're not scrolling through Linked In for new opportunities. They're in their jobs, doing good work, and they're not actively looking. The only way to recruit great people is through personal networks and referrals from people they trust.

This is why your first recruiting resource should be your own network and the networks of your founding team. Who do you know who's exceptionally talented? Who do you know who cares about this specific problem? Who do you know who would consider leaving their current job if the opportunity was compelling enough?

Your second recruiting resource should be your investors. Good VCs know hundreds of talented people. They can introduce you to people who have directly expressed interest in leaving to join an early-stage company in your space. They can make warm introductions instead of cold recruiting.

Your third resource should be employees who've already joined. They know talented people from their previous jobs. They have referral incentives (usually cash bonuses). They're much more selective about who they refer because they're putting their reputation on the line.

Only after you've exhausted these warm sourcing methods should you start with job boards and recruiting agencies. And even then, you should be aware that you're selecting for people who are actively looking rather than the best people in your market.

Cultural Red Flags During the Interview Process

Before you hire someone, pay attention to how they interview. The interview process is a constrained situation where both parties are trying to make a good impression. If someone is difficult, evasive, or disrespectful during the interview, that's a preview of how they'll be when things are stressful.

Red flags include:

- Someone who talks all the time and doesn't ask questions about the role, company, or vision

- Someone who becomes defensive when you push back on a technical claim or past decision

- Someone who seems primarily motivated by compensation and doesn't ask about the mission or product

- Someone who makes negative comments about previous employers or colleagues

- Someone who seems more interested in impressing you than in understanding whether the role is right for them

- Someone who is dismissive of ideas that challenge their approach

- Someone who doesn't seem curious about how the company will actually succeed

None of these red flags mean someone is a bad person. They might indicate that someone's motivations aren't aligned with what you're looking for in an early employee, or that they're not in a great headspace for this particular opportunity.

Green flags include:

- Someone who asks thoughtful questions about the product, market, and business model

- Someone who seems genuinely curious about how you're thinking about problems

- Someone who pushes back respectfully on your ideas and explains their reasoning

- Someone who is transparent about their concerns and what would need to be true for them to join

- Someone who seems excited about the mission, not just the opportunity

- Someone who asks about other people on the team and company culture

- Someone who is willing to learn and adapt rather than trying to impose their way of doing things

Early-stage companies often offer salaries at 75-85% of market rates, supplemented by equity, to balance budget constraints with competitive compensation. Estimated data.

Compensation Strategy: Creating Fairness Across Stages

Compensation in early-stage companies is a weird mix of market rates (you need to pay enough to compete with other options) and equity (which provides the long-term upside that makes the low salary worth it). Get this balance wrong, and you'll either overpay and run out of capital, or underpay and lose people to better-funded competitors.

Salary: Paying Enough Without Breaking the Budget

Your compensation strategy should be tied to what you're trying to optimize for. In the earliest stages of a company, every dollar of payroll is a dollar that's not going toward product development or customer acquisition. But if you pay significantly below market rate, you'll attract people who are okay with below-market compensation, which often correlates with below-market quality.

The strategy that works best is to pay a reasonable but not exceptional salary (roughly seventy-five to eighty-five percent of market rate for the role and location) and make up the difference with equity. This way, you're communicating that the equity is real and meaningful, but you're not taking advantage of people who need cash to live on.

Market rate varies significantly by location, role, and experience level. A senior engineer in San Francisco has a market rate roughly double that of a junior engineer in the Midwest. You need to understand what competitive compensation looks like for the specific role you're hiring for.

One approach is to gather benchmark data from multiple sources: surveys like Blind and Levels.fyi that show real compensation, conversations with other founders who've hired similar roles, and analysis of what competing companies are offering. You don't need to hit the exact market rate, but you should be within ten to fifteen percent of it.

Equity: Making It Real and Transparent

Equity is supposed to provide the long-term incentive to stay and build the company. But in many startups, equity is treated as an abstract concept. The employee doesn't understand how much it's worth, what happens to it if the company is acquired, or what happens if the company fails.

The way to make equity feel real is to have explicit conversations about the math. If you're raising a Series A at a twenty-million-dollar post-money valuation, and you're handing out equity to employees such that they own zero-point-five percent of the company, that equity is worth approximately one hundred thousand dollars at the current valuation (before taxes, vesting, and assuming the company doesn't fail).

You don't need to be this specific every time, but you should make sure employees understand the relationship between equity size and company valuation. You should also explain what happens to equity if the company is acquired, if there's a down round, or if the company fails.

Most importantly, you should make sure employees understand that equity is speculative. There's a material risk that the company fails and their equity is worth nothing. That's not a weakness of your offer. That's the honest truth about early-stage investing. If employees can't handle that level of risk, they're probably better off at an established company.

The Conversation You Must Have With Early Employees

Before someone joins your company, they need to understand the risk-return profile. They're trading the certainty of a larger salary at an established company for the uncertainty of equity upside in an early-stage startup. Some people will make that trade happily. Others will join and then panic when they realize how much risk they've taken on.

The conversation should cover:

- What the base salary is and how it compares to market rate

- What the equity grant is and what it represents as a percentage of the company

- What the equity could be worth if the company succeeds (in multiple scenarios: acquired for ten million, fifty million, five hundred million)

- What the equity is worth if the company fails (zero dollars)

- The probability of each scenario (you can't know this, but you can be honest about your beliefs)

- How long they need to stay vested (typically four-year vesting with a one-year cliff)

- What happens to equity if they leave (unvested equity disappears, vested equity belongs to them)

- What happens to equity if the company is acquired (typically paid out proportionally unless there are special provisions)

- What happens to equity in a down round (it might be subject to down-round protection, or it might dilute significantly)

This conversation feels heavy. That's good. You want people who understand the risk they're taking and are still excited about the opportunity. If someone can't handle this level of transparency, they'll eventually become a source of conflict when the company encounters difficulty.

Building a Team That Scales With You

Your founding team is hiring itself every time you make a hiring decision. You're not just adding a new person to the team. You're establishing a precedent for hiring, compensation, performance standards, and culture.

This is why the hiring philosophy you develop in the first year is so critical. If you're disciplined about hiring, subsequent managers will be disciplined. If you make desperate hires, the next manager will think that's acceptable.

The Hiring Manager Training You're Doing

When you hire someone to lead engineering, you're not just hiring an engineer. You're hiring the person who will hire the next twenty engineers. That person will look at the engineers you hired and assume that's the quality bar. If you hired one excellent engineer and one mediocre engineer to save money, the engineering manager will think that's the acceptable range.

If you want your company to have great engineering practices in five years, you need to hire engineering managers now who understand what great looks like. Same with product, design, sales, and operations.

This means that many of your early hiring decisions should be about finding people who are not just good at their functional role but also good at building and evaluating teams. A great engineering manager is worth multiple great individual contributors because they compound across everyone they hire.

Culture as a Competitive Advantage

Culture is often treated as a soft skill, something that matters once the company is large enough to have an HR department. In reality, culture is a critical competitive advantage in the early stage precisely because you can establish it intentionally.

Culture is the set of norms and expectations about how decisions get made, how conflicts are resolved, how people treat each other, and what excellence looks like. It's not the casual Friday policy or the office foosball table. Those are nice to have, but they're not culture.

The culture you establish in your first year determines the culture your company will have at five hundred people. This is why so many fifty-person companies feel completely different from each other. They went through fundamentally different cultural training in the first year.

To establish the culture you want, be intentional about:

- How you make decisions (by consensus? by autocratic founder? by data? by majority vote?)

- How you handle disagreement (are people encouraged to push back? do they get defensive? do you actually change your mind when someone makes a good point?)

- How you treat mistakes (do you blame people, or do you learn from them? do you make a big deal about small errors, or do you only care about pattern mistakes?)

- How you prioritize (do you chase every opportunity, or do you say no to things? do you celebrate progress toward the long-term goal, or do you panic about every short-term metric?)

- How you define excellence (what does good work look like? what's the bar for acceptable? how do you reward great performance?)

- How you handle conflict (do you ignore it? do you address it directly? do you involve other team members?)

All of these norms are established through what you do, not what you say. If you say you want people to be decisive but then you second-guess decisions constantly, your actual culture is indecisive. If you say you value people having life outside work but then you send Slack messages at midnight expecting immediate responses, your actual culture is always-on.

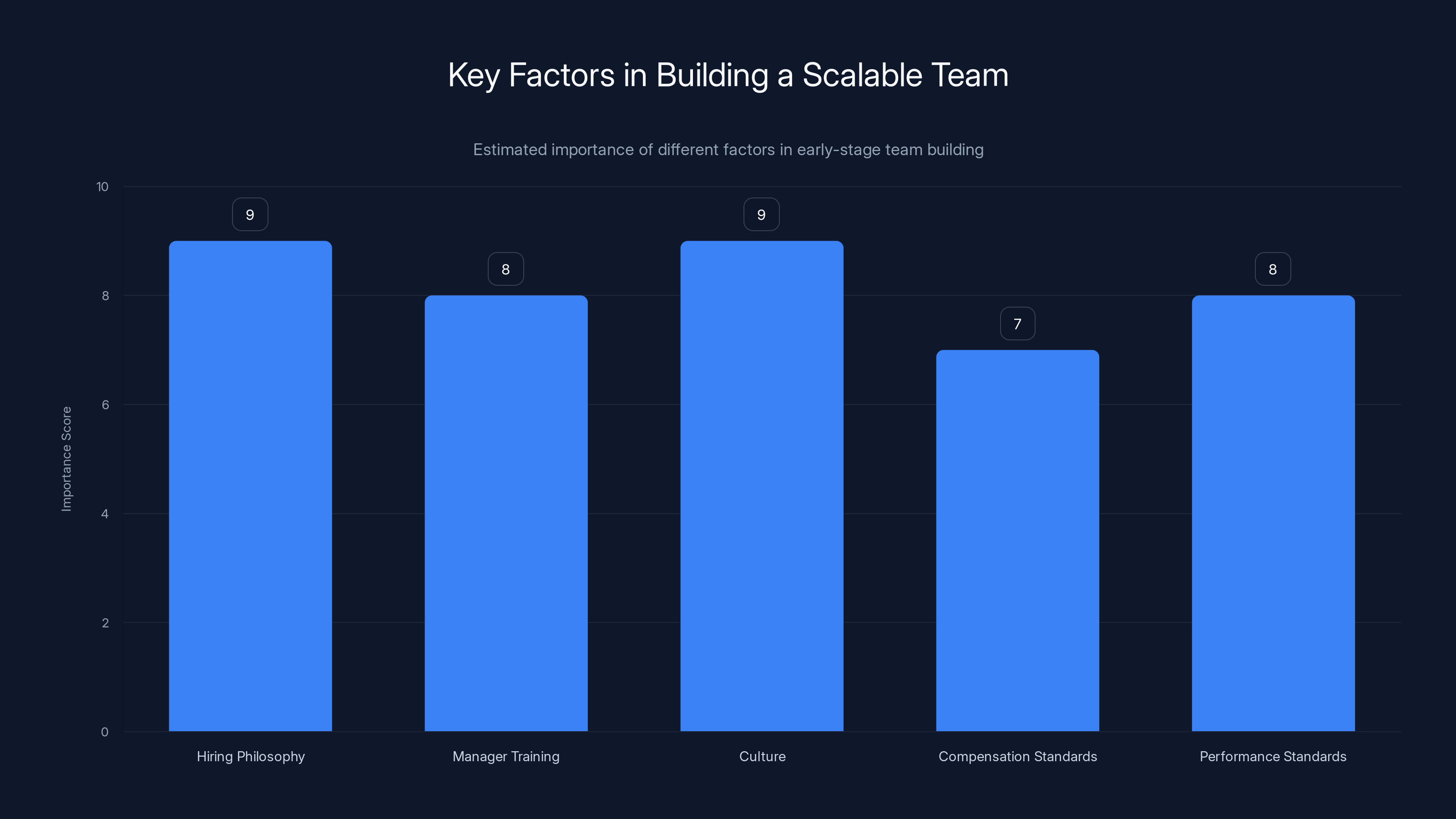

Establishing a strong hiring philosophy and culture are crucial for building a scalable team. Estimated data shows these factors score highly in importance.

Common Mistakes: What Founders Get Wrong About Founding Teams

If you're building a founding team, you're probably aware of some of these pitfalls. Others might seem counterintuitive until you've experienced them firsthand.

Hiring for Current Needs Instead of Future Growth

The most common mistake is hiring based on what you need right now instead of who you'll need in six months. You're drowning in work, so you hire someone to help with the immediate crisis. But you don't check whether that person can grow with the role or whether they'll be a good fit when the company is larger.

This creates a situation where you quickly outgrow your early hires. They were perfect for putting out fires at ten people. They're not the right person to lead the function at fifty people. So you hire above them, which creates an awkward reporting structure, or you fire them, which is painful and expensive.

The solution is to hire people who are one level better than what you currently need. If you need someone to do individual contributor work, hire someone who can do that and also mentor other people and think about process improvement. You're not paying them extra money to do these things, but you're being intentional about hiring people who can grow.

Hire to Fill Gaps, Not to Hire Quickly

When you're growing fast, there's constant pressure to hire. Your engineering team is overwhelmed, so you need more engineers. Sales is struggling to hit targets, so you need more salespeople. Support is drowning in tickets, so you need more support.

The instinct is to solve these problems by hiring as quickly as possible. But the wrong hire in a critical role causes more damage than no hire at all. An engineer who writes code that others have to maintain, a salesperson who promises things product can't deliver, or a support person who gives customers incorrect information, these hires destroy culture and create extra work for the rest of the team.

The solution is to slow down hiring slightly and be intentional about it. Yes, you'll be constrained for a while longer. But you'll avoid making a hire that creates problems for the next two years.

Confusing Hustle with Sustainable Work Ethic

Early-stage companies require a lot of work. That's real. But there's a difference between people who are capable of intense work when it's needed and people who think constant chaos is how business works.

Some founders hire people who thrive in chaos and reward them with rapid promotion and bigger roles. What they've actually done is hire people who create chaos. Once the company gets a little structure and process, these people get bored because they're not constantly fighting fires anymore.

The people you want are those who are capable of intense work when needed but who actually want to build systems and processes that reduce the chaos over time. They're willing to work hard for a period to hit a deadline or solve a crisis. But they're not trying to create permanent crisis.

Hiring Clones Instead of Complementary People

There's a natural tendency to hire people who think like you do, work like you do, and have similar experiences. They're easier to work with because you understand them. But they create blind spots.

The strongest teams have people with diverse backgrounds, thinking styles, and approaches. Someone who's more structured in their thinking can balance someone who's more intuitive. Someone who's focused on the details can balance someone who's always thinking about the big picture. Someone who values relationships can balance someone who values efficiency.

These differences create friction sometimes. But they also create a team that's more resilient and more likely to catch mistakes or think about problems from multiple angles.

Deferring Culture Until You're Larger

Many founders tell themselves that they'll worry about culture once the company reaches a certain size. They'll have explicit values once they're fifty people. They'll have clear communication practices once they're twenty. They'll formalize how decisions get made once they're established.

What actually happens is that the culture gets set by default during the early stage, and it's very hard to change later. If you make decisions autocratically now, that becomes the expectation for how decisions work. If you're disorganized and reactive now, that becomes the culture.

The best time to intentionally establish culture is right now, with your first few employees. It takes the same amount of effort to establish good culture as bad culture. You might as well be intentional about it.

Equity Structures That Actually Scale

As you build your founding team, the equity structure you create needs to work at very different company stages. It needs to be simple enough that you can explain it to someone in ten minutes. It needs to be flexible enough that you can adjust it as the company evolves.

The Option Pool Problem

One of the most important but overlooked decisions is how large to make your option pool. The option pool is equity reserved for future employees. When you raise a seed round, investors will ask what percentage of the company is reserved for employee options. When you raise a Series A, investors will expect you to increase the pool to facilitate future hiring.

If your option pool is too small, you won't have enough equity to hire the people you need later. If it's too large, it dilutes all the early employees unnecessarily.

The standard is to reserve roughly ten to twenty percent of the post-raise company for employee options. So if you raise capital and the investors own thirty percent, the company is effectively split into seventy percent founder and employee equity and thirty percent investor equity. Of that seventy percent, the founders might own forty percent and fifty percent is reserved for employee options (current and future).

This structure works because it ensures you always have equity available to recruit, but it doesn't go overboard and dilute everyone unnecessarily.

Vesting Schedules That Make Sense

Vesting is the process by which employees earn their equity over time. The standard is four-year vesting with a one-year cliff. This means that after one year of employment, the employee becomes fully vested in twenty-five percent of their grant (the cliff prevents people who leave in the first year from taking any equity). After four years, they're fully vested in one hundred percent.

The reason for the cliff is to make sure that people who leave very early don't get rewarded for it. If you join a company for three months and decide it's not for you, you shouldn't get vested equity.

The four-year schedule is long enough to provide meaningful incentive to stay (if you leave after three years, you only get seventy-five percent of your grant) but short enough that people can actually get most of their equity while they're still at the company.

Some companies do different vesting schedules. Three-year vesting is becoming more common in certain markets. Some companies do two-year vesting for senior executives. But four-year with one-year cliff is the standard and is what investors expect.

Double-Trigger Acceleration

Double-trigger acceleration is a provision that accelerates vesting if certain events happen, typically a change of control (acquisition) combined with termination.

For example, you might have a provision that says if the company is acquired and the employee is not offered a role at the acquirer, their unvested equity becomes fully vested. This protects employees from situations where an acquisition prevents them from finishing their vesting schedule.

This is important for employee morale because it ensures they're not completely locked in if external events prevent them from vesting naturally. It also makes sense from a fairness perspective: if someone has been with you for three years and then you're acquired, they've earned most of that equity anyway, so why would you take it away just because the company changed hands?

Estimated data shows that the 50-50 equity split is the most common among co-founders, but other splits like 60-40 and 70-30 are also prevalent.

Building Advisory Boards and Early Mentorship

Your founding team isn't just the people you employ. It also includes advisors and mentors who contribute knowledge and networks without being part of the day-to-day operations.

The right advisors can be extraordinarily valuable. They've been through what you're going through. They've made mistakes and learned from them. They have networks and can introduce you to customers, investors, or potential hires. They provide perspective when you're too close to the problem.

The wrong advisors are distractions. They have opinions but don't understand your specific situation. They expect a lot of communication and attention without providing proportional value.

Who Should Be on Your Advisory Board

Your advisors should be selected based on what you need, not who's famous or impressive. If you're building a B2B Saa S company and none of your founders have sales experience, you might want a sales advisor. If you're building something technically complex and your founders are all business-focused, you might want a technical advisor.

The best advisors are people who have directly succeeded in your space. They understand the market because they've sold into it or built products in it. They can provide tactical advice that's actually relevant instead of generic advice that applies to everything.

Advisors should also be people who are actually willing to spend time with you. Some very successful people agree to be advisors as a status thing but never respond to emails or take meetings. These advisors are net negative. They make your company look credible, but they don't actually help.

Advisor Equity and Compensation

Advisors are typically given a small amount of equity (zero-point-one to zero-point-five percent of the company) and no salary. The equity is an incentive to actually care about your success and to encourage them to help you recruit and fundraise.

If someone is going to spend significant time (five to ten hours per month) on your company, you might offer a small equity grant plus a monthly retainer. But most advisors work for equity only.

The key is to make sure that advisor equity is small enough that it doesn't significantly dilute your employee option pool. You're not trying to give away the company to advisors. You're giving them a stake large enough to align incentives but small enough that they're not meaningfully diluted.

Red Flags That Your Founding Team Isn't Working

Sometimes despite your best efforts in hiring and team building, you realize that someone on the founding team isn't working out. The earlier you recognize this, the better, because the cost of a bad founding team member increases exponentially over time.

The Obvious Red Flags

Some red flags are obvious: someone isn't doing their job, they're creating conflict with other team members, or they're behaving unethically. These are reasons to act quickly, because they're damaging the team.

The more subtle red flags are the dangerous ones. Someone is technically competent but their heart isn't in it. Someone is producing output but they're demoralizing everyone around them. Someone is doing their job but they've fundamentally misaligned with the vision and they're pulling the company in a different direction.

The Conversation You Need to Have

If you're sensing that someone isn't working out, you need to have an explicit conversation about it. Not a vague feedback conversation. A direct conversation about whether you both still think this is the right situation.

The conversation should acknowledge the issue clearly: "I've noticed that you seem less engaged than you were six months ago." Or: "I'm concerned that your approach to hiring is different from what we agreed on." Or: "I'm not sure you're excited about this anymore."

Then give them the opportunity to be honest with you. Sometimes they'll confirm your concern and tell you they're ready to move on. Sometimes they'll explain what's going on and you'll realize there's a misunderstanding you can fix. Sometimes they'll react with defensiveness, which itself is information about whether you can actually work together.

The goal of this conversation isn't to fire them (although that might be the outcome). The goal is to create clarity about whether this partnership still makes sense.

How to Recruit When You Have Nothing

One of the most challenging times to recruit is when the company is tiny, pre-product, and you're living on personal savings and early investor capital. How do you convince great people to join when there's no traction and plenty of downside risk?

Clarity of Vision Is Your Most Attractive Resource

When you have no product and no revenue, the only thing that matters is the vision and the people. If you can articulate clearly why this company needs to exist and what it will mean for the world if you succeed, you'll attract people who care about that mission.

The founders who raise capital most easily and attract the best early employees are those who can explain their vision in a way that makes people think, "Oh, that's obviously right. I'm surprised nobody's done this yet." Not because the vision is revolutionary, but because it's so clear and well-reasoned that it's hard to disagree.

Working on a pre-product startup is incredibly hard. People take on this difficulty because they believe in the mission. If your mission is unclear or unconvincing, you have no lever to recruit people.

Social Proof From Day One

Social proof is the best recruiting tool you have. When someone knows that smart people have already joined or are already advising the company, they're more likely to take the opportunity seriously.

This is why it's important to get public commitments from people early. When you tell someone, "I'm thinking about starting a company in this space," they might be interested but they're not sold. When you tell them, "I've already recruited Sarah to be our first engineer and we've raised a seed from Andreessen Horowitz," suddenly it feels real.

You're not making up social proof. You're amplifying real proof that already exists. Get your first investor's commitment and tell people about it. Get your first engineer's commitment and tell people about it. Each piece of social proof makes the next recruit easier.

The Narrative About Why Now

Great people want to work on things that matter at a moment when they can actually matter. Part of your recruiting pitch should be about why this is the right time to build this company.

If you're building in a market that's just starting to have product-market fit, you can explain why it's now possible to succeed (versus five years ago when it wasn't). If you're building on top of a new technology that just became available, you can explain why the timing is right. If you're addressing a problem that's become more acute in the last year, you can explain the timing.

The best recruiting pitches tie the personal opportunity (we're building something meaningful with smart people) to the market opportunity (this market is starting to move) to the timing opportunity (this is the window when we can build something defensible).

FAQ

What is the most important factor when building a founding team?

The most important factor is having founders with complementary skills, aligned values about the company's ambitions, and a proven track record of working together. While having great ideas and market opportunity matter, the quality of the founding team is the single best predictor of whether a company succeeds or fails. Venture capitalists can often tell whether a company will succeed within thirty minutes of meeting the founding team, not because the idea is obviously great, but because they've seen enough teams to recognize which ones have the attributes that drive success.

How should co-founders split equity?

The most common approach is an equal or near-equal split with a slight plus-or-minus one share differentiation to break deadlocks. For example, one founder might get 50.5% and the other 49.5%, or one might get 60% and the other 40%. The specific percentages matter less than the principle of having a clear tiebreaker for major disagreements. More importantly, founders should avoid basing equity split on "I came up with the idea so I deserve more," because the real work of building the company is ahead of you. Both founders should feel like their contribution will be valued fairly based on what they actually do, not what they did before the company existed.

How much equity should I give to my first employees?

First employees typically receive between one-half percent and two percent of the company, depending on seniority and the specific role. The first engineer or sales hire might get one to two percent, while a later employee might get zero-point-five percent. The key is consistency and clarity. All employees should understand how much equity they're getting, what it represents as a percentage of the company, and what the potential financial upside could be at different company valuations. Equity should be enough to matter financially if the company succeeds but not so much that it's the primary motivation for joining.

What types of investors should I avoid?

You should avoid investors who give you money but then get "in your kitchen," as VCs put it. These investors have opinions on everything, stress you out when metrics dip, but don't provide enough value to justify the pressure they create. The best way to identify these investors is to talk to their other portfolio companies before taking their money. Ask founders what the investor is like when things are going poorly, not just when things are going well. You'll get much more honest feedback from founders who've been through a difficult period with the investor than from founders in good times.

How should I structure compensation for early employees?

The typical structure is a salary at roughly seventy-five to eighty-five percent of market rate for the role, plus equity that provides the real upside. This communicates that the equity is meaningful and valuable. Before hiring someone, you should have an explicit conversation about the risk-return profile: what's the salary, what's the equity grant and what it could be worth at different valuations, what's the probability of different outcomes, and what happens to their equity if the company fails. People who can handle this level of transparency and are still excited are the right fit for early-stage companies.

How do I know if someone is going to be a good culture fit?

Pay attention to how people interview. The interview is a constrained situation where both parties are trying to make a good impression. If someone is defensive when you challenge their ideas, gets stuck talking about themselves without asking questions, seems primarily motivated by money, or makes negative comments about previous employers, those are red flags. Green flags include being genuinely curious about the company and mission, asking thoughtful questions about product and strategy, being willing to push back respectfully on your ideas, and being transparent about their concerns and what would need to be true for them to join.

What should I do if a founding team member isn't working out?

You should have an explicit conversation about it sooner rather than later. Don't hint at the problem or give vague feedback. Be direct: "I've noticed you seem less engaged" or "I'm concerned about our alignment on the vision." Give them the opportunity to be honest about what's going on. Sometimes they'll confirm your concern and tell you they're ready to move on. Sometimes they'll explain something you didn't understand. Sometimes they'll get defensive, which itself is information about whether you can actually work together. The goal is clarity about whether the partnership still makes sense.

How do I recruit great people when the company is very early stage and I have no traction?

Clarity of vision is your most powerful recruiting tool when you have no product or revenue. If you can articulate why this company needs to exist and why now is the right time to build it, you'll attract missionaries who care about the mission. Use social proof from day one: get your first investor's commitment and tell people. Get your first technical advisor's commitment and tell people. Make public commitments that signal the company is real and people are already believing in it. Finally, explain why the timing is right. The best recruiting pitches tie the personal opportunity (building something meaningful with smart people) to the market opportunity (the market is starting to move) to why now (this is the window when you can build something defensible).

What is vesting and why does it matter?

Vesting is the process by which employees earn their equity over time. The standard is four-year vesting with a one-year cliff, meaning employees become fully vested in twenty-five percent of their grant after one year (the cliff), then earn the rest monthly over the remaining three years. The cliff prevents people who leave in the first few months from getting vested equity. The four-year schedule is long enough to provide meaningful incentive to stay but short enough that people can actually earn most of their equity while still at the company. This structure aligns the long-term incentives of employees with company success.

How large should I make my employee option pool?

The standard is to reserve ten to twenty percent of the post-investment company for employee options. So if investors own thirty percent after a funding round, that thirty percent comes out of what would have been founder and employee equity. You then allocate a portion to current employees and reserve the rest for future hiring. This structure ensures you always have equity available to recruit people later without diluting early employees unnecessarily. Talk to a startup lawyer about the specific structure for your situation, as there are tax and legal implications that vary by jurisdiction.

Conclusion: The Multiplier Effect of a Great Founding Team

Building a company is one of the hardest things you'll ever do. Nothing in business school, no amount of preparation, fully readies you for the intense pressure of early-stage company building. The difference between founders who thrive and founders who burn out, between companies that scale and companies that plateau, often comes down to one factor: did you build a founding team that could handle the pressure and keep you grounded when things got crazy?

The decisions you make in your first few months about who joins your founding team will echo through the company for years. You're not just hiring people. You're establishing precedents about hiring quality, compensation structures, values alignment, and what excellence looks like. These precedents become the training ground for every future manager in your company.

This is why the most successful founders spend as much time on founding team selection as they do on strategy and product. They recognize that the people are the lever that makes everything else possible. A brilliant strategy executed by a mediocre team produces mediocre results. A decent strategy executed by an exceptional team produces exceptional results.

The specific advice in this guide (split equity slightly unequal to break deadlocks, recruit missionaries not mercenaries, choose investors who are actually helpful) matters less than the underlying principle: be intentional. Don't accept defaults. Don't hire because you're desperate. Don't partner with someone because you're friends. Don't raise from investors just because they'll write a big check. Make conscious choices based on what you're actually optimizing for.

When you look back on the early days of your company, you'll remember the product decisions and the customer conversations and the near-death experiences with fundraising. But what you'll actually credit for survival and success will be the people. You'll think about the engineer who stayed even when their old company offered them a big raise. You'll think about the early customer who became an advisor and helped you think through product strategy. You'll think about the investor who called at the right moment and told you the company was going to be okay. These people matter more than anything else.

Building a winning founding team isn't about finding perfect people. It's about finding the right people for this moment of the company. It's about being honest about what you're looking for and what you're offering. It's about recognizing that early decisions have lasting consequences and being willing to invest time in getting them right. It's about building a team that believes in the mission enough to endure the difficulty, trusts you enough to take risks, and is capable enough to actually succeed.

Start here. Get the team right. Everything else flows from that decision.

What's Next?

If you're actively building a founding team, consider using tools that help automate administrative tasks and keep your team aligned. Platforms that handle document creation, presentation generation, and workflow automation can free up mental energy for the real work of building. Runable offers AI-powered automation for presentations, documents, reports, and more, starting at $9/month, helping growing teams focus on what matters.

The founding team you build today will determine the company you become in five years. Make the decision intentional. Take the time to get it right. Because once you have the right team, everything else becomes possible.

Key Takeaways

- Investor quality matters far more than check size—the best VCs help with recruiting and strategy regardless of capital amount

- Equity splits should be equal or near-equal with a plus-or-minus one share difference to break deadlocks, preventing future resentment

- First hires must be missionaries motivated by mission and equity upside, not mercenaries primarily seeking salary

- Founding team selection is the primary determinant of startup success, even more important than product or initial market opportunity

- Culture and hiring standards are set in the first year and are nearly impossible to change later, so establish them intentionally

- Early employee compensation should balance reasonable salary (75-85% market rate) with meaningful equity to attract the right people

- Vesting schedules should follow the standard four-year vesting with one-year cliff to align long-term incentives

Related Articles

- TechCrunch Founder Summit 2026: Speaker Guide & Application Tips [2025]

- Startup Battlefield 200 2026: Complete Guide to Apply & Win [2025]

- How to Get Into a16z's Speedrun Accelerator: Insider Tips [2025]

- Why B2B Software Isn't Dead: What AI Really Means for SaaS [2025]

- Why Top Talent Is Walking Away From OpenAI and xAI [2025]

- How Rivian's Software Strategy Saved the Company in 2025

![Building a Winning Founding Team: VC's Essential Playbook [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/building-a-winning-founding-team-vc-s-essential-playbook-202/image-1-1771506577808.png)