Introduction: The Speedrun Reality Check

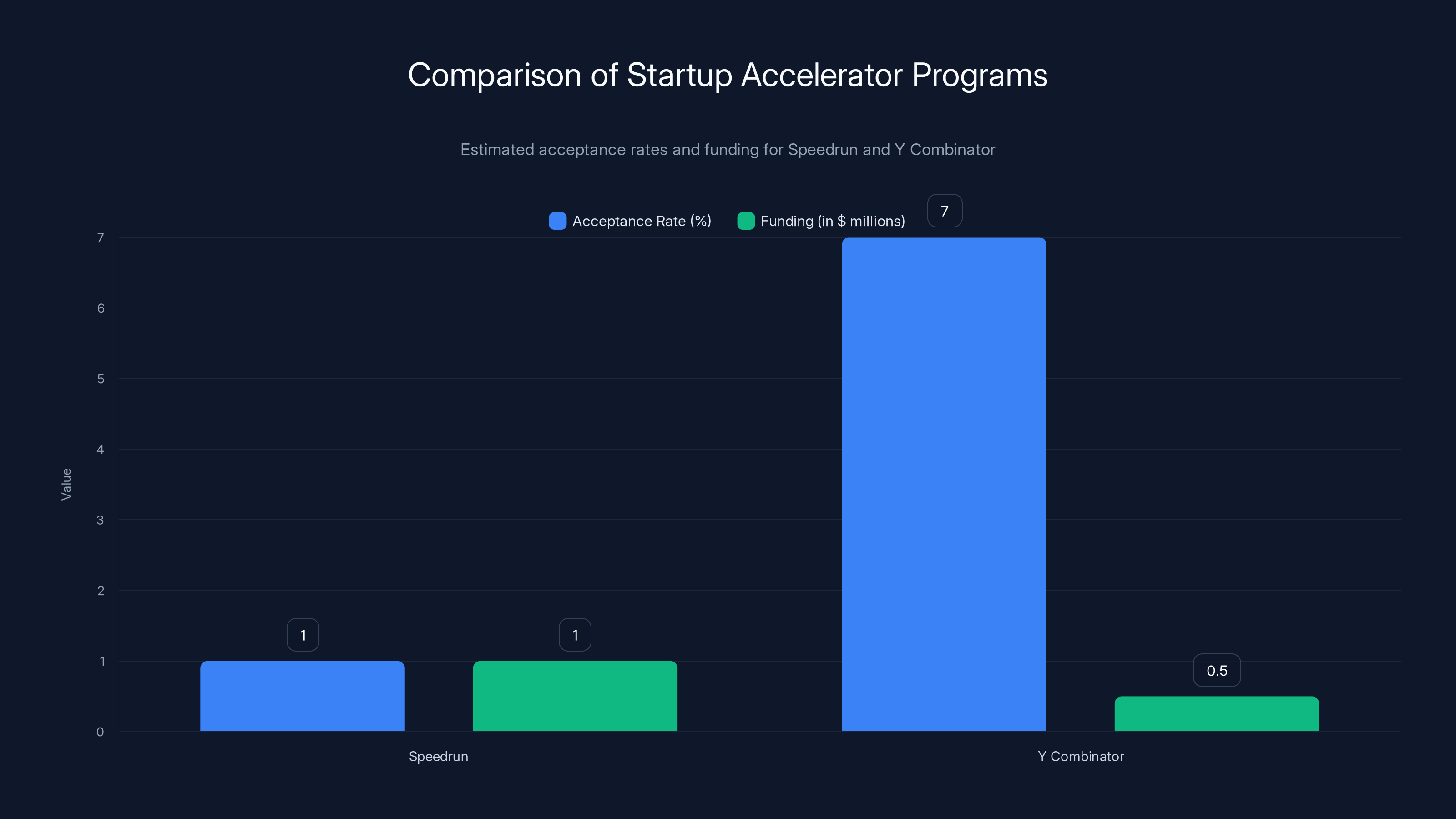

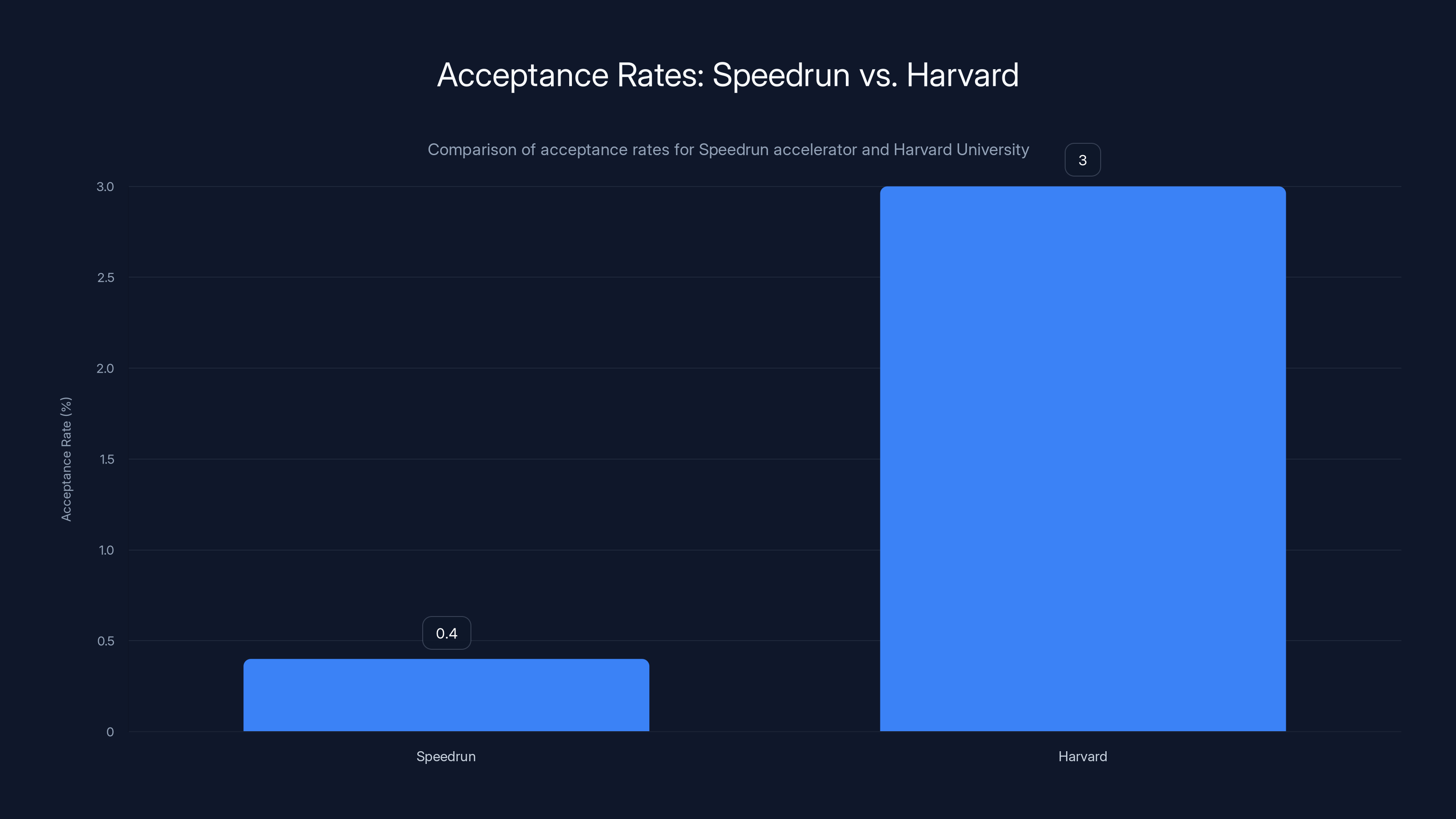

Last year, over 19,000 startups applied to Andreessen Horowitz's Speedrun accelerator program. Fewer than 80 got in. That's a 0.4% acceptance rate. To put that in perspective, Harvard's acceptance rate hovers around 3%. Getting into Speedrun is genuinely harder than getting into an Ivy League school.

Here's the brutal part: most founders don't understand why they're rejected. They build decent products, have decent ideas, and send in what feels like a solid application. Then they get a rejection email and move on, never knowing what went wrong.

The difference between those who make it and those who don't? It's often not what you'd expect. It's not always about the product-market fit, the market size, or even the technology. Instead, a16z's leadership team focuses on something more fundamental: whether your founding team is genuinely exceptional, whether you've done the work to validate your idea beyond theory, and whether you can articulate your vision without leaning too heavily on AI-generated pitch decks.

Speedrun launched in 2023 as a gaming-focused accelerator, then expanded into entertainment and media. Today, it's a horizontal program accepting founders from any industry. The program runs for roughly 12 weeks in San Francisco, with two cohorts per year accepting between 50 and 70 startups each. That means about 100 to 140 founders get this opportunity annually. If you're one of the thousands applying, you're competing in the most selective startup accelerator in North America right now.

The good news? The selection process is transparent. a16z doesn't rely on opaque algorithms or hidden criteria. Instead, they've shared their exact framework, priorities, and common mistakes. Understanding what they're actually looking for—rather than what you think they want—is the first step toward standing out.

This guide breaks down exactly how to position yourself as a Speedrun candidate, what a16z evaluates, and the tactical mistakes to avoid.

TL; DR

- Founding team composition matters more than your product: a16z prioritizes complementary skills, shared history, and self-awareness over market theory

- Traction beats theory: Even small validation signals prove you've tested your assumptions, not just hypothesized about market problems

- Market theory kills applications: Spending too much time explaining why the problem exists wastes space you should use demonstrating why your team is exceptional

- AI as a tool, not a crutch: Use AI for grammar and clarity, but founders must articulate their vision without it during interviews

- Timing and cohort fit matter: Off-season applications get reviewed, but alignment with cohort themes increases acceptance odds

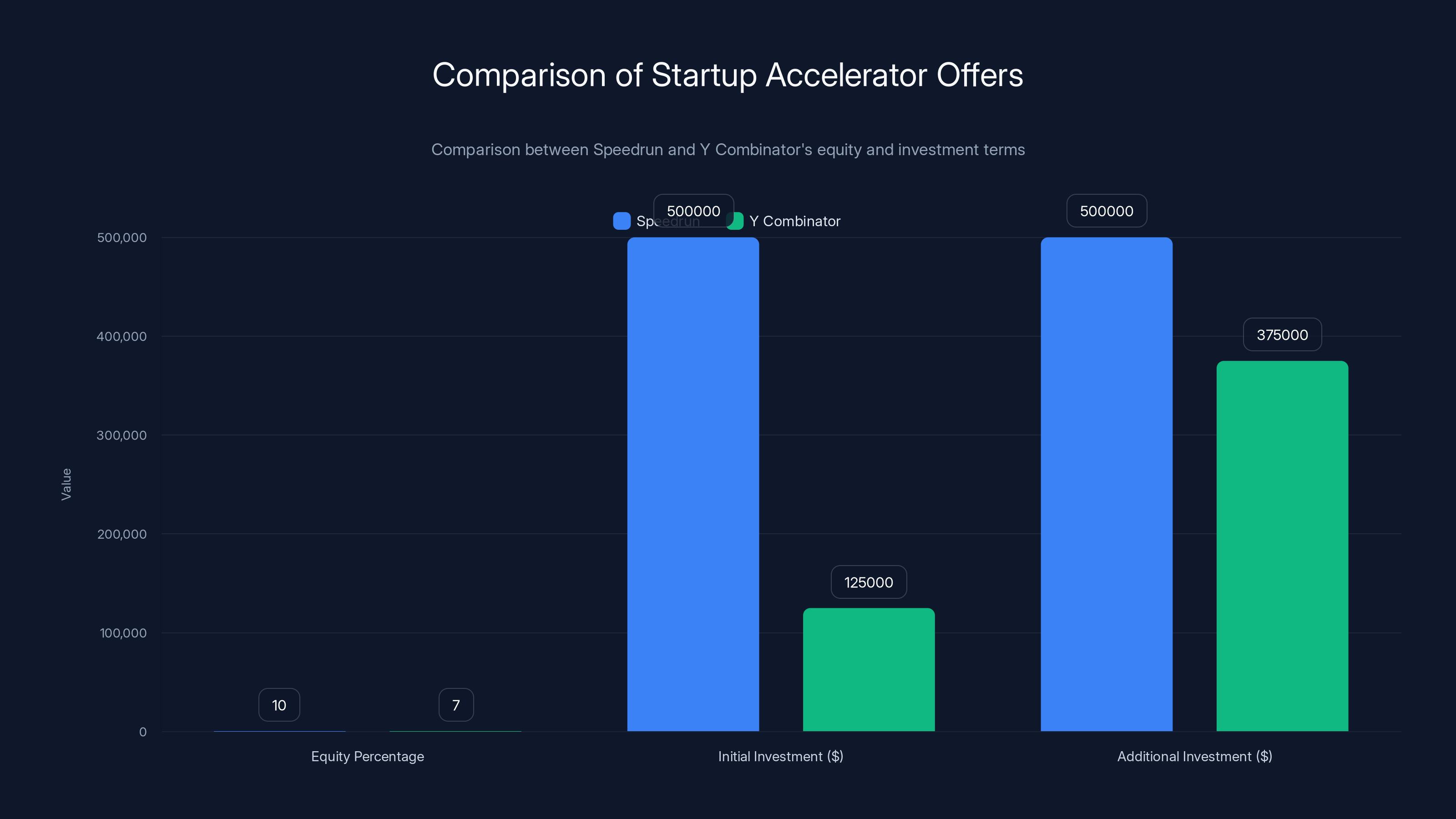

Speedrun is more selective with an acceptance rate of less than 1%, compared to Y Combinator's estimated 7%. Speedrun offers up to

Why Speedrun Matters: More Than Just Money

When people think about startup accelerators, they often fixate on the check size. Speedrun offers up to $1 million, which is substantial. But the money is only part of the story.

The program works like this: a16z invests

But here's what those numbers don't capture: a16z's portfolio network, brand value, and operational support. Speedrun founders get access to vendor credits worth $5 million across platforms like AWS, OpenAI, Nvidia, and Deel. That's not a vanity perk. For AI startups, AWS and OpenAI credits alone can reduce your runway burn by 30 to 40% in the early months.

More importantly, a16z doesn't just write checks and disappear. Speedrun partners work directly on go-to-market strategy, brand positioning, media narrative, and talent sourcing. These aren't side activities. Founders consistently report that a16z's operational input accelerates decisions that would normally take months. When you're running 12-week cohorts, having someone who's built companies before telling you "stop exploring that, focus here" is worth significantly more than the equity cost.

The program also confers legitimacy. Getting accepted to Speedrun signals to future investors, enterprise customers, and top-tier talent that your startup passed a brutal selection gauntlet. That credibility opens doors.

Final advantage: the cohort effect. You're surrounded by other founders who've also passed the 0.4% filter. That peer group becomes an invaluable network. Some Speedrun companies have partnered with each other, shared customers, and referred talent. The cohort becomes part of your company's trajectory long after Demo Day.

Speedrun offers a higher initial investment but requires more equity compared to Y Combinator. Estimated data for additional investment terms.

The Founding Team: Why Everything Else Comes Second

If there's one thing that separates accepted founders from rejected ones, it's this: a16z obsesses over team composition.

Joshua Lu, Speedrun's general manager and a partner at a16z, puts it plainly: for an early-stage startup, the team is the primary signal. Products can pivot. Markets can shift. But the founding team's ability to navigate uncertainty, work through disagreements, and adapt is what determines whether a startup survives.

This doesn't mean you need a specific formula. It doesn't require one technical cofounder and one business cofounder and one marketing cofounder. Instead, a16z evaluates whether your team has complementary capabilities and, critically, whether there are any glaring holes.

When they review an application, they're asking: "Can this team independently solve the first 20 problems they'll encounter without external help?" If you're missing a core competency—and everyone on the team knows it but hasn't addressed it—that's a red flag.

Worse is when founders don't seem aware of their gaps. If you claim your team can handle everything perfectly without acknowledging where you might struggle, reviewers assume you haven't thought deeply about execution.

What a16z actually prefers is founder self-awareness. Applications that say something like, "We're strong on product and engineering. We know distribution is our biggest risk, and here's our plan to hire for that" are far more compelling than applications claiming superhuman competence across all domains.

Second, a16z favors teams with shared history. This isn't a hard requirement, but it's a meaningful signal. Teams that have worked together before know how to disagree productively. They understand each other's working styles. They have pattern recognition about who will make what call under pressure.

Think about the last few major disagreements you had with people. How did they resolve? Did people take feedback well? Did conversations build on each other, or did they devolve into posturing? Founders who've already navigated that with each other have a documented track record. Founders meeting for the first time are taking on unknown risk.

This doesn't mean you can't have cofounders meeting for the first time at the accelerator. But if you do, you'll need to compensate for that risk elsewhere. Maybe you have substantial traction. Maybe you're solving a problem with unprecedented clarity. Maybe you're attacking a market that's moving so fast that relative speed matters more than team chemistry. But all else equal, a16z will prefer the team with history.

The Technical Co-Founder Question: AI Changes Everything

One application question comes up constantly: "Do we need a technical cofounder?"

Traditionally, the answer was yes. Non-technical founders building software startups faced skepticism. How do you manage engineering if you can't code? How do you make product decisions? How do you evaluate technical feasibility?

AI has genuinely changed this calculus. Tools like Claude, GPT-4, and GitHub Copilot have lowered the barrier to building working prototypes. A non-technical founder can now partner with a contractor or AI-assisted developer and validate core assumptions in weeks rather than months.

But here's the nuance: a16z still prefers technical founders. It's not a dealbreaker to lack technical cofounders if you've compensated elsewhere. But all else equal, having someone on the team who understands software, can read code, and can contribute directly to product decisions is an advantage.

Why? Because technical founders tend to make faster decisions on core product questions. They can evaluate whether a feature is technically complex or simple. They understand scaling constraints earlier. They catch architectural mistakes before they become expensive. In a 12-week accelerator, that speed is valuable.

The real signal a16z looks for is whether your team can actually build what you claim you'll build. If you're a non-technical founder claiming you'll have a sophisticated AI system up and running in 3 months, but your technical partner is a junior developer with no AI experience, there's friction. That's the gap that gets flagged.

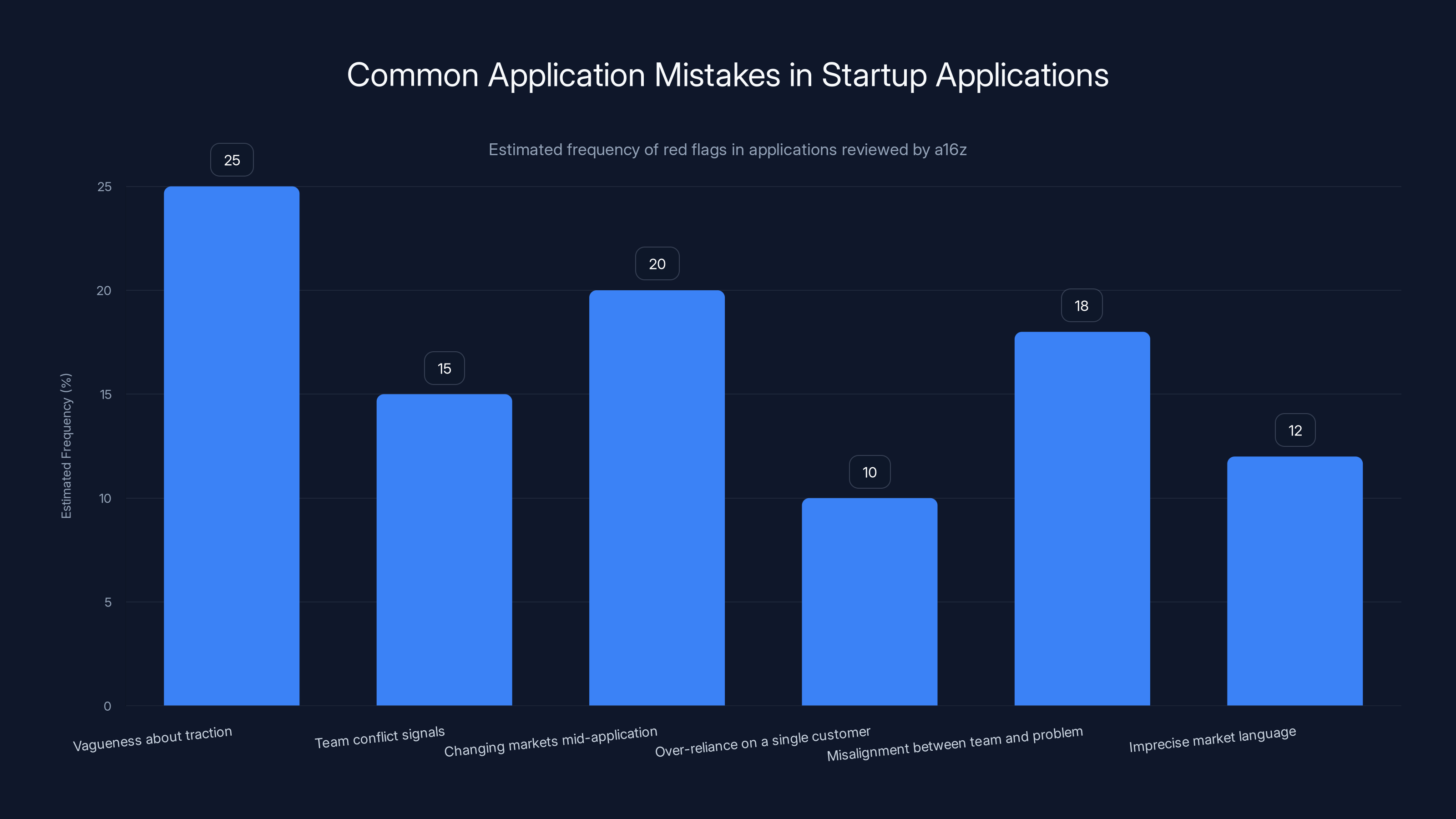

Vagueness about traction is the most common mistake, estimated at 25%, while over-reliance on a single customer is less frequent at 10%. Estimated data based on common red flags.

Traction Is Your Cheat Code: Why Validation Matters

Here's what separates many accepted applications from rejected ones: traction.

And here's the misunderstanding most founders have: traction doesn't mean you need 100,000 users or millions in revenue. It means you've demonstrated that actual humans care about your problem.

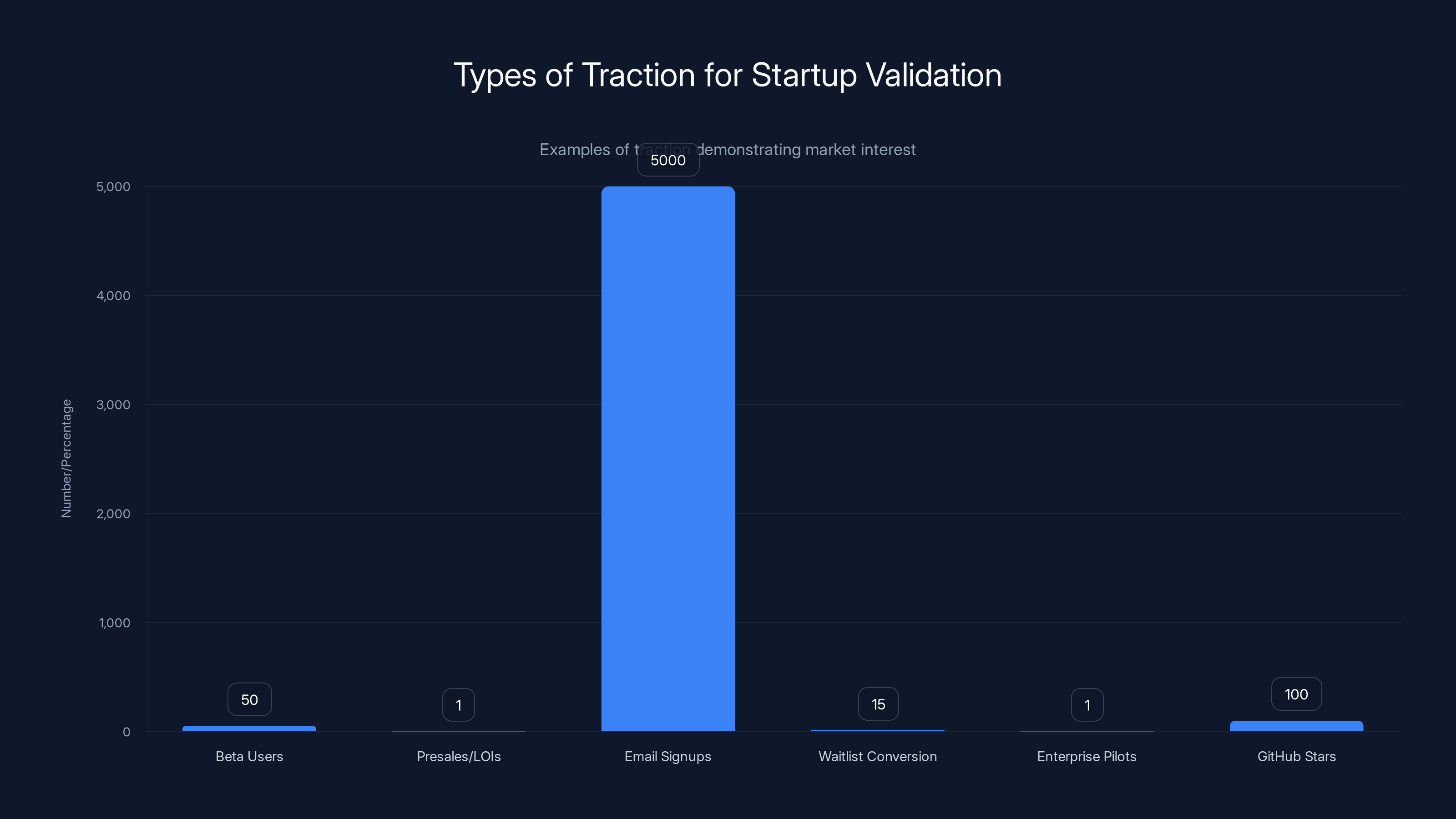

Traction might be:

- 50 beta users engaging weekly: Not massive, but real validation

- Presales or LOIs from target customers: Someone signed up to pay you

- 5,000 email signups with 20% open rates on your updates: People are actually interested

- A waitlist converting at 15%+ when you launch: Your messaging resonates

- Enterprise pilots in motion: One customer testing you at scale

- GitHub stars and community engagement: For open-source plays, real adoption

What these have in common is that they're not theoretical. You didn't survey 100 people asking "would you pay for this?" You actually put friction in front of them and watched whether they followed through.

Here's why a16z obsesses over traction: it proves you've tested your assumptions. Most founders come in with a thesis about a market problem and a solution. Traction proves your thesis isn't pure speculation. It proves you've talked to customers, iterated based on feedback, and found something that works.

In a 12-week program, that's gold. If you come in with product-market fit signals already visible, a16z's job becomes simpler: help you scale faster. If you come in with pure theory, they have to help you find product-market fit, which is slower and riskier.

Lu describes Speedrun's sweet spot as "teams that have a very small spark or fire, and we help pour gasoline on it." The spark is traction. The gasoline is a16z's network and capital. Without the spark, the gasoline is wasted.

The Market Theory Trap: What Kills Most Applications

Walk into any startup pitch, and you'll hear something like this:

"The enterprise software market is worth

It's a standard pitch framework. Every accelerator founder learns it. And it's exactly what kills most Speedrun applications.

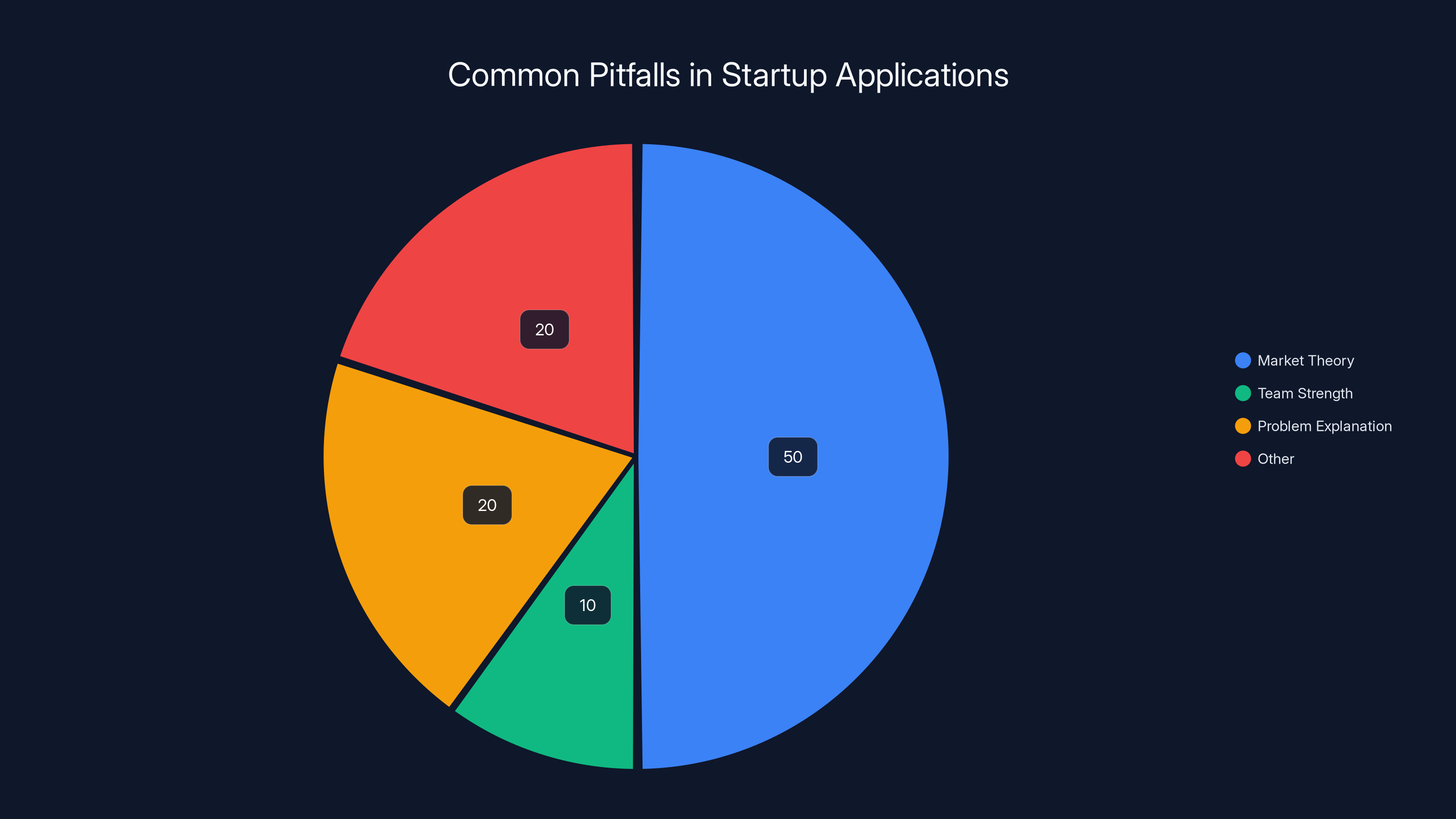

Lu is unusually candid about this. He says founders spend too much energy in applications explaining market theory: why the problem exists, why the market is growing, why their solution is right. They'll dedicate half the application to the thesis.

Here's the truth: none of that distinguishes you.

Every founder applying has done market sizing. Every founder has researched TAM, SAM, and SOM. Every founder thinks they're attacking a problem worth solving. What you're not seeing in those applications is what actually matters: whether your founding team is exceptional.

Worse, that market theory often proves wrong. Slack wasn't targeting the "team chat market" because it didn't exist. Figma didn't hit product-market fit because VCs correctly predicted the design tool TAM. Airbnb faced years of skepticism that the "vacation rental market" was big enough.

Speedrun sees this constantly. Founders come in certain they're solving a problem worth billions, then discover six weeks into the program that they misunderstood customer needs entirely. The market theory was sound. The execution was wrong.

So what should you actually emphasize?

First, briefly explain the problem and why you're solving it. Be concise. You don't need a 500-word market analysis. Two or three paragraphs suffices. Investors understand the market dynamics. If you're building an AI agent for legal contract review, your audience knows that's a real problem. You don't need to convince them of that.

Second, focus the bulk of your application on demonstrating why your team is exceptional. Why are you, specifically, the right person to solve this? What have you built before? What do you understand about customer psychology that others miss? What's your unfair advantage?

Third, emphasize validation. Don't theorize about whether customers want your solution. Show that they do. That's the entire competitive advantage in your application.

Estimated data suggests that startup applications often overemphasize market theory (50%) at the expense of demonstrating team strength (10%).

The AI Application Question: When It Helps, When It Hurts

Founders increasingly use AI to draft and refine applications. Claude helps them think through positioning. Chat GPT cleans up grammar. AI tools reorganize arguments for clarity. The question a16z gets constantly: is that okay?

Lu's answer is clear: yes, use AI for editing and refinement. There's no excuse for typos or grammatical errors anymore. AI can make your application more readable, more concise, and more coherent. That's utility.

Where it becomes a problem is when AI does the thinking for you.

Here's why: if you make it past the application stage, you'll have a live video interview. In that call, you need to articulate your startup's vision without notes, without a polish pass, and without AI refinement. You need to tell the story naturally, respond to unexpected questions, and think on your feet.

If your application was written entirely by AI, there's a mismatch. The interviewer reads something articulate and coherent, then hops on a call and finds you can't explain your own business clearly. That mismatch is a red flag. It signals either dishonesty or detachment from your own founding story.

What a16z actually wants is to hear your voice in the application. Not perfect language necessarily. Not flawless structure. But your authentic perspective on why this problem matters to you, why your team is right for it, and what you've already validated.

Use AI as a tool. Don't let AI become your voice.

Cohort Timing: When to Apply and Why It Matters

Speedrun runs two cohorts per year. Typically, the application windows open in January and July. The program itself runs for about 12 weeks.

But here's what most founders don't realize: a16z reviews applications year-round. They have an "off-season" intake process where they continuously evaluate founders who apply outside the main windows. Those off-season applications aren't ignored. They're reviewed alongside the next cohort's submissions.

So when should you apply?

If your startup aligns with the current cohort's focus or theme, apply in the main window. If Speedrun's marketing mentions they're emphasizing AI tools one quarter, and you're building AI tools, that's alignment. Reviewers will naturally spend more time on applications that fit.

If your startup is strong but doesn't perfectly align with the current cohort theme, consider timing your application for off-season review. You might face less competition. You might face more scrutiny. The trade-off varies.

In either case, don't wait until the last day of the application window. Speedrun reads applications continuously. Early applications get reviewed by fresh reviewers with more attention bandwidth. Applications submitted hours before deadline get reviewed by tired reviewers optimizing for speed.

Is that fair? No. But it's how human review works. Your advantage is understanding that submitting early, with a strong application, is better than submitting late with an optimized one.

Traction types such as 50 beta users or 5,000 email signups with 20% open rates are key indicators of market interest and validation. Estimated data.

Application Structure: How to Actually Organize Your Pitch

Most Speedrun applications follow a structured format with specific sections. Here's how to think about each one:

The One-Line Description: This is your positioning statement. It should be clear enough that someone unfamiliar with your space understands what you do immediately. Bad: "We're building the future of work." Good: "We automate contract review for in-house legal teams, reducing turnaround time from days to minutes."

The Problem Statement: Briefly explain what you're solving and who has the problem. Avoid market theory here. Focus on the human experience. What frustration does your target customer experience? What gap do they currently work around?

Your Team: This is your main real estate. Dedicate significant space here. List founder backgrounds, relevant experience, and what each person brings. Explain why your skills are complementary. If there are gaps, acknowledge them and explain how you'll hire to fill them.

Traction and Validation: Show what you've done to test your assumptions. User numbers, customer conversations, presales, pilot deals, beta engagement. Be specific about what the traction means.

Your Go-To-Market Approach: How will you actually acquire customers? Not theoretically, but practically. Do you have relationships with key decision makers? Do you have a distribution channel? What's your customer acquisition cost assumption?

Why Now: Is there a timing element? Has a regulatory change opened a door? Has a new technology matured? Or is this just a good problem to solve regardless of timing? Be honest. Not every idea needs a "why now" hook.

Why You: Why can your team execute this better than anyone else? What's your unfair advantage?

The key principle: minimize market theory, maximize founder credibility and proof of concept.

The Founder Interview: What Actually Gets Asked

If your application makes it past initial screening, you'll get a video interview. This is where founders often struggle the most.

They've spent weeks perfecting their application. They've worked with AI to make everything sharp and concise. Then they hop on a Zoom call and freeze. The interviewer asks something slightly unexpected, and suddenly they can't articulate their own business.

This happens because most founders prepare to present their narrative. They don't prepare to defend it.

A16z's interview style isn't pitch-focused. It's conversation-focused. The interviewer wants to understand how you think, how you respond to challenge, and whether your prepared narrative holds up under scrutiny.

Expect questions like:

- "Your application says X. But I just heard the opposite from three other founders in your space. What do you think they're missing?"

- "If I called your beta users today, what would they say about your product? What would they criticize?"

- "You claim your TAM is 100K budgets. How does that math work?"

- "Walk me through the last time a customer told you your core assumption was wrong. What did you change?"

- "Why are you the right person to solve this problem specifically?"

These aren't gotcha questions. They're designed to see whether you've really thought deeply about your startup or whether you've memorized talking points.

How do you prepare? Interview your own assumptions. Play devil's advocate with yourself. Ask a trusted mentor to challenge your narrative. Record yourself explaining your startup and listen back. That self-awareness transfers to the actual interview.

One more thing: interviewers value founders who can say "I don't know" when they don't know something. Trying to BS your way through a technical question about your own company signals a problem. Saying "I don't know that metric, but here's how I'd find out" signals maturity.

Speedrun's acceptance rate of 0.4% is significantly lower than Harvard's 3%, highlighting the intense competition for the accelerator program.

The Competitive Advantage Question: What Actually Sets You Apart

In application after application, founders claim competitive advantages that don't exist.

"Our team is more experienced." (So are 50 other teams applying.)

"We're building this for a massive market." (So is everyone else.)

"Our product is better." (Everyone's product is "better" in some dimension.)

Here's what actually matters: what can your specific team do that's genuinely difficult to replicate?

Sometimes it's domain expertise. You spent 10 years as a lawyer and understand legal workflows at a depth that someone without that background can't match. That's real.

Sometimes it's relationships. You've built a network of CTOs at Fortune 500 companies. You can get pilot deals that competitors can't access. That's real.

Sometimes it's technical insight. You invented a novel approach to a problem that's now becoming feasible because of new tools or frameworks. That's real.

What's not real: working harder, being smarter, or having a passion for the problem. Everyone in your applicant pool works hard. Most are smart. Nearly all have passion.

As you write your application, ask yourself: "What can we do that our top three competitors literally cannot do?" If you can't answer that question, you don't have a defensible competitive advantage yet. Which is fine—you might develop one in the program. But don't claim one you don't have.

The 12-Week Arc: What Speedrun Actually Does

Understanding the program structure helps you understand what a16z is actually optimizing for in selection.

Speedrun is a 12-week program. The first two weeks are onboarding and relationship building. You're meeting other founders, getting to know the a16z partners working with your cohort, and clarifying what problems you need help with most urgently.

Weeks three through ten are execution and support. You're working with a16z partners on specific problems: go-to-market strategy, raising your next round, hiring, customer discovery. Partners are checking in on your progress, pushing you on core assumptions, and connecting you with their network.

The final two weeks are preparation for Demo Day and investor meetings. You're refining your pitch, meeting with investors a16z has introduced, and preparing for whatever comes after the accelerator.

Given that structure, here's what a16z selects for: founders who can move fast and take feedback well. If you come in defensive, convinced that your original plan is perfect, the program will be frustrating. If you come in curious, willing to test assumptions and change direction, you'll get the most value.

This explains why product-market fit matters less than you'd expect. A16z knows that in 12 weeks, they can help you find it if you're willing to look. But they can't help you if you're locked into a particular direction.

The founders who get accepted—and who succeed—are the ones who come in with strong conviction about the problem they're solving, but flexible conviction about the solution.

Common Application Mistakes: The Red Flags Reviewers See

Lu didn't explicitly list these, but they emerge when you understand how a16z reviews applications.

Vagueness about traction: "We're generating buzz" and "lots of people are interested" aren't traction. Specific numbers are. "We have 47 beta users, they're opening our emails at 28% rates, and we're converting 3% of signups to paid pilots." That's traction.

Team conflict signals: If your application reveals friction between founders—even subtly—it's a problem. If one founder claims they're the "idea person" and another is the "execution person," with minimal overlap, reviewers wonder whether you'll actually work together well.

Changing markets mid-application: "We started building for healthcare, but realized hospitality is better." That's fine. But if your narrative doesn't clearly explain why you changed, it looks like you're directionless.

Over-reliance on a single customer or contract: "We're closing a $2 million enterprise deal." That's great traction. But if your entire narrative is built on that one customer, reviewers wonder whether you have a repeatable business model or a consulting project.

Misalignment between team and problem: You're building an enterprise software company, but your founding team has no enterprise sales experience, no relationships with enterprise buyers, and no plan to hire someone who does. That gap is flagged.

Imprecise market language: Using terms incorrectly or oversimplifying how your market actually works signals that you haven't done the homework. Know your competitor landscape. Know the alternatives customers currently use. Know why they'd switch to you.

Fundraising Context: Understanding Speedrun's Position

Speedrun exists in an interesting spot in the startup ecosystem. It's not Y Combinator, which focuses on volume and brand. It's not a micro fund, which cares mainly about allocation. It's a16z's aggressive bet on finding exceptional founders early.

That positioning matters because it explains what a16z is optimizing for. They have more capital available than they'll ever deploy. They can afford to be highly selective. Their constraint is finding founders they want to bet on.

This means that impressive metrics matter less than impressive founder conviction. A founder with 1 million users and weak conviction might lose to a founder with 5,000 users but crystal-clear vision and execution speed.

It also means that timing, from a fundraising ecosystem perspective, can matter. If a16z just deployed capital heavily into a specific category, they might be less eager to do it again. If a category is heating up, they might be more eager. This isn't something you can control, but it's worth knowing exists.

For you, this means: don't optimize your entire pitch around what you think a16z wants. Instead, build an exceptional startup and communicate it clearly. If a16z thinks you're the best thing coming through, they'll find reasons to say yes.

Building a Compelling Narrative: The Art and Science

All the tactical advice in the world won't matter if your fundamental narrative is weak.

Your narrative is the through-line that connects your background, your insight about the problem, your solution, and your team. It's the story that makes a reviewer want to understand more rather than move to the next application.

Good narratives often have a moment of insight. "I spent five years managing operations at a legal firm and realized that 30% of our budget went to contract review, and we were still missing half the risks. That's when I understood the problem actually existed."

Or: "I tried to build an internal tool for this problem and couldn't find existing solutions. Then I realized other teams at my company had built the same tool independently. That's when I knew this was a real market opportunity."

These aren't flashy. They're credible. They're specific. They explain why you, specifically, have insight into this problem that others don't.

Contrast that with: "This is the future of work. Every company will need this eventually."

That's not narrative. That's aspiration.

As you build your narrative, ask:

- What specific experience or observation triggered your insight?

- Why haven't others solved this problem?

- What are you betting on that might be wrong?

- What's the first thing you'd change about your approach if customer feedback contradicted your assumptions?

Answering those questions will strengthen every part of your application.

After Acceptance: What Comes Next

If you get accepted, what should you know?

First: the real work starts. Speedrun isn't a credential that guarantees success. It's 12 weeks of intense support from operators who've been in your position before. What you do with that support matters enormously.

Second: Demo Day is an event, not the goal. The goal is to have a compelling story and traction that attracts investors. Demo Day happens to be the venue where you pitch that story to many investors at once. But building the actual business matters more than the pitch.

Third: the a16z network is real, but it's not automatic. Partners will help open doors, but they won't close deals for you. The value is access and introduction, not guarantee.

Fourth: other Speedrun cohort members will become your peers and sometimes collaborators. Invest in those relationships. Some of your best future hires, customers, or partners will come from your cohort.

Fifth: be prepared to change direction. Many accepted founders come in with a confident vision and leave with a different one. That's not failure. That's the accelerator working.

The Bigger Picture: Accelerators in 2025

Speedrun matters because it's one of the hardest startup accelerators to get into. But it also matters because it represents a shift in how top-tier accelerators think about founder selection.

Instead of predicting winners based on metrics, they're focusing on founder quality, execution speed, and learning velocity. Those are harder to assess from an application, which is why Speedrun's screening is so rigorous.

If you're not accepted to Speedrun, that doesn't mean your startup won't succeed. It means you didn't make it through this specific filter. Build your startup anyway. Get traction. Build an exceptional team. Raise capital through other channels. Most successful founders never attended a top accelerator.

But if Speedrun is genuinely where you want to go, understanding their actual criteria—founder quality over market size, traction over theory, team over product—gives you the best possible chance.

FAQ

What exactly is Speedrun, and how is it different from other accelerators?

Speedrun is Andreessen Horowitz's highly selective startup accelerator program that runs two cohorts per year, accepting 50-70 startups per cohort. The program is about 12 weeks long and provides up to

What does a16z actually look for in Speedrun applications?

A16z prioritizes three things: founding team quality and complementary skills, evidence of traction or customer validation (even if small), and clarity on why your specific team is the right one to solve the problem. They explicitly de-emphasize market theory and rely less on product metrics than you'd expect. The program's leadership looks for teams that demonstrate self-awareness about their gaps, have worked together before or have documented shared history, and have done at least preliminary customer validation. They avoid applications that spend disproportionate time on market sizing and TAM analysis without demonstrating that real customers actually care.

Do I need a technical cofounder to apply to Speedrun?

No, but it helps. While AI tools have lowered the barrier to building prototypes without a technical cofounder, a16z still prefers technical founders because they make faster product decisions and catch scaling problems earlier. If you don't have a technical cofounder, you'll need to compensate with other strengths like significant customer traction, domain expertise, or proven relationships with your target market. The key is demonstrating that your team can actually execute the vision you're pitching.

How much traction do I need to be competitive in Speedrun?

There's no minimum. Speedrun accepts some startups with almost no traction but exceptional founders and clear market insight. However, any traction whatsoever significantly strengthens your application. This could be 50 beta users, 5,000 email signups with good engagement metrics, presales to customers, or even pilot agreements in motion. The point is showing that real humans care about your problem, not just theorizing that they might. Even 20 focused customer conversations with specific feedback can constitute meaningful traction.

Should I use AI to write my application?

Use AI as an editing and refinement tool, not as your voice. AI can improve grammar, clarify your arguments, and help you think through positioning. But if your application is entirely written by AI, interviewers will notice the mismatch when they talk to you live and you can't articulate your business naturally. A16z wants to hear your authentic perspective and reasoning in your application, not polished text that doesn't reflect how you actually think and communicate. The red flag is when the application is eloquent but the founder can't back it up verbally.

How competitive is the acceptance process really?

Very. With an acceptance rate below 1%, Speedrun is harder to get into than Harvard University. Over 19,000 startups applied to the most recent cohort, with fewer than 80 accepted. This means your application needs to be exceptional, but it also means you're competing for access to a program with intense support and an extremely high-quality peer group. The competitiveness is partly about the quality bar and partly about visibility—many founders simply don't know about Speedrun or understand the selection criteria.

What are the biggest mistakes founders make in Speedrun applications?

Common mistakes include: spending too much space on market theory rather than founder credibility, claiming competitive advantages that aren't defensible, using vague language about traction ("we're generating buzz" instead of specific numbers), revealing team friction or unclear roles, overselling a product that hasn't been customer-validated, and showing misalignment between the problem being solved and the team's actual experience. Reviewers also flag applications where founders seem detached from their own business narrative or where the core assumption hasn't been tested with actual customers.

If I don't get accepted to Speedrun, does that mean my startup won't succeed?

Absolutely not. Speedrun is one of many paths to building a successful startup. Most founders never attend a top accelerator, and plenty of successful companies were built by teams rejected from competitive programs. Speedrun acceptance is one filtering mechanism among many. If you're rejected, the feedback might help you strengthen your company, but lack of Speedrun acceptance is not predictive of startup failure or success. Build your company, get customer traction, demonstrate team execution, and raise capital through other channels.

When should I apply to Speedrun relative to my startup's stage?

Apply when you have something to show beyond just the idea. Ideally, you'd have at least some customer conversations, a working prototype, and early traction signals, but these don't need to be extensive. Speedrun accepts startups in various stages as long as founders are exceptional. Main application windows open in January and July, but a16z reviews off-season applications year-round. Apply as soon as your application is strong rather than waiting for the next window. Early in the application cycle is better than last-minute submissions.

What happens if I'm accepted? How should I prepare?

If accepted, understand that the 12-week cohort is intensive. You'll be working with a16z partners on specific business challenges, not just optimizing your pitch. Come prepared to test and potentially change your core assumptions about customers and product direction. Build relationships with other cohort members seriously—they'll often become valuable peers and collaborators. The real value of Speedrun is the operational support and network access, not just the capital, so position yourself to extract maximum learning from partners' guidance during those 12 weeks.

Conclusion: The Reality of Getting Into Speedrun

Getting into Speedrun is hard because Speedrun is designed to be hard. A16z isn't trying to democratize startup funding. They're trying to concentrate capital and operational support on founders they believe have exceptional potential.

That means the bar is legitimately high. But it also means it's transparent. You know what they're looking for. You know what kills applications. You know that team quality, executed traction, and authentic founder insight matter more than impressive market sizing or slick pitch decks.

If you apply, apply with your actual startup story, not the story you think a16z wants to hear. Build something people care about. Get customers, even if it's just a handful. Form a team where people genuinely work well together and complement each other's skills. Know what you don't know. Be honest about gaps and your plans to fill them.

Do those things, and your application will be competitive. You might still not get in. 99.6% of applicants won't. But you'll have built something real in the process, which matters more than any accelerator credential.

The founders who succeed in accelerators, and in startups generally, are the ones who would be building anyway. Speedrun acceptance is an accelerant, not a prerequisite. Build the startup first. The accelerator is optional.

But if you want to maximize your chances: focus on team. Show traction. Stop explaining markets and start explaining why your team is exceptional. Use AI as a tool, not a crutch. And apply knowing that you're competing for something genuinely scarce. That context will help you build a stronger application than founders who think Speedrun is just another accelerator.

It isn't. That's why it's worth the effort to try.

Key Takeaways

- A16z selects for exceptional founding teams with complementary skills and shared history, not market theory or impressive metrics

- Any traction beats theory—even 50 beta users or presales prove your assumptions aren't pure speculation

- Most applications fail because founders spend too much time on market sizing and not enough demonstrating team capability

- AI can refine your application, but using it as a crutch is obvious during live interviews and signals detachment

- The 12-week program is about execution and support, not just capital—founders who stay flexible outperform those locked into original plans

Related Articles

- How to Get Into a16z's Speedrun Accelerator: Insider Strategies [2025]

- Cherryrock Capital's Contrarian VC Bet on Overlooked Founders [2025]

- Cohere's $240M ARR Milestone: The IPO Race Heating Up [2025]

- xAI Engineer Exodus: Inside the Mass Departures Shaking Musk's AI Company [2025]

- Inertia Fusion: $450M Funding Boom and the Race to Grid-Scale Power [2025]

- Meridian AI's $17M Raise: Redefining Agentic Financial Modeling [2025]

![How to Get Into a16z's Speedrun Accelerator: Insider Tips [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/how-to-get-into-a16z-s-speedrun-accelerator-insider-tips-202/image-1-1771171580645.jpg)