Ring's Search Party Surveillance Feature Sparks Mass Backlash [2025]

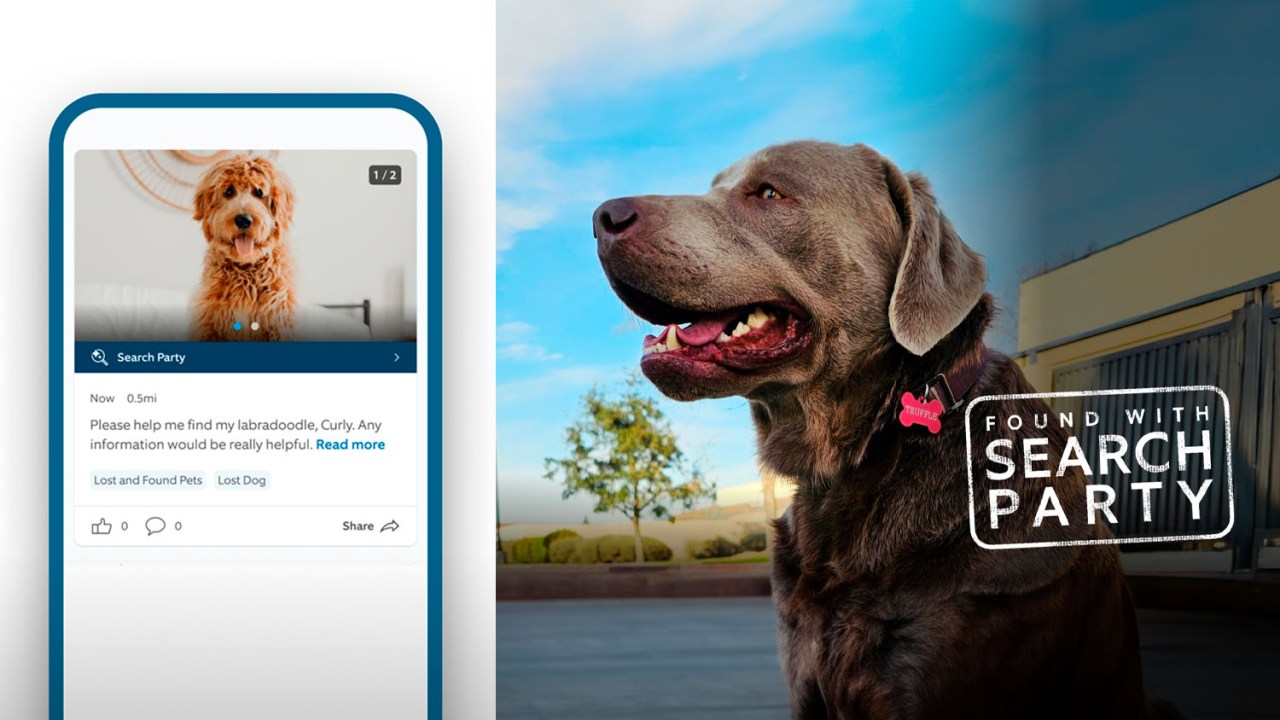

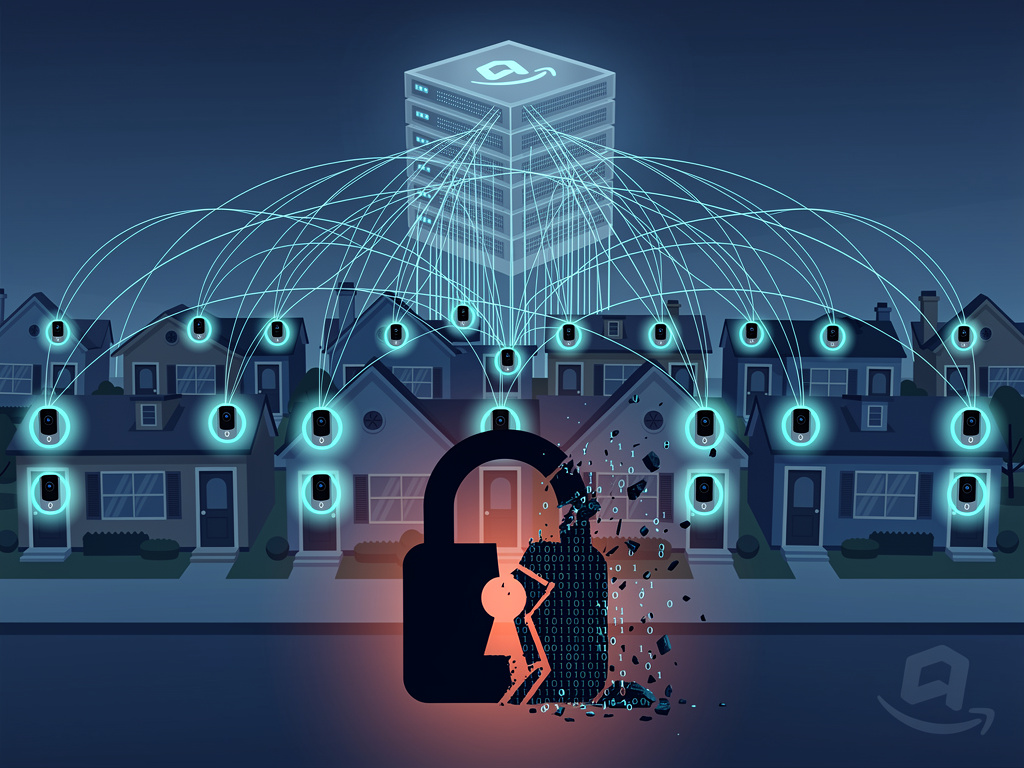

It was a 30-second Super Bowl ad that seemed innocent enough on the surface. A lost dog. Concerned neighbors. Ring cameras coordinating across a neighborhood to locate the missing pet. Then the cameras activated, scanning the streets in synchronized fashion like some kind of benevolent neighborhood watch program.

But the internet saw something different. What Amazon Ring presented as a heartwarming story about community and technology felt, to many observers, like a glossy commercial for mass surveillance disguised as pet recovery. According to GeekWire, the ad's portrayal of coordinated surveillance raised significant privacy concerns.

This wasn't paranoia. This was a legitimate concern rooted in the actual capabilities of the technology, the company's actual partnerships with law enforcement, and the real trajectory of surveillance infrastructure in America. As noted by Truthout, the ad highlighted the growing integration of AI surveillance in everyday life.

When you step back and look at what's actually happening here, you're staring at something that should make you uncomfortable. A massive network of residential cameras. AI that can identify and track subjects across multiple feeds. Integration with law enforcement databases. Default-enabled features that process footage without explicit user consent. These aren't conspiracy theories. These are shipping features, as detailed in Amazon's official announcement.

The backlash to Ring's Search Party ad reveals something important about how Americans are starting to feel about the surveillance infrastructure being built around them. It's not just about Ring. It's about the ecosystem of interconnected cameras, databases, and law enforcement partnerships that's being assembled piece by piece, with each new feature presented as solving a specific, sympathetic problem.

What Is Ring's Search Party Feature?

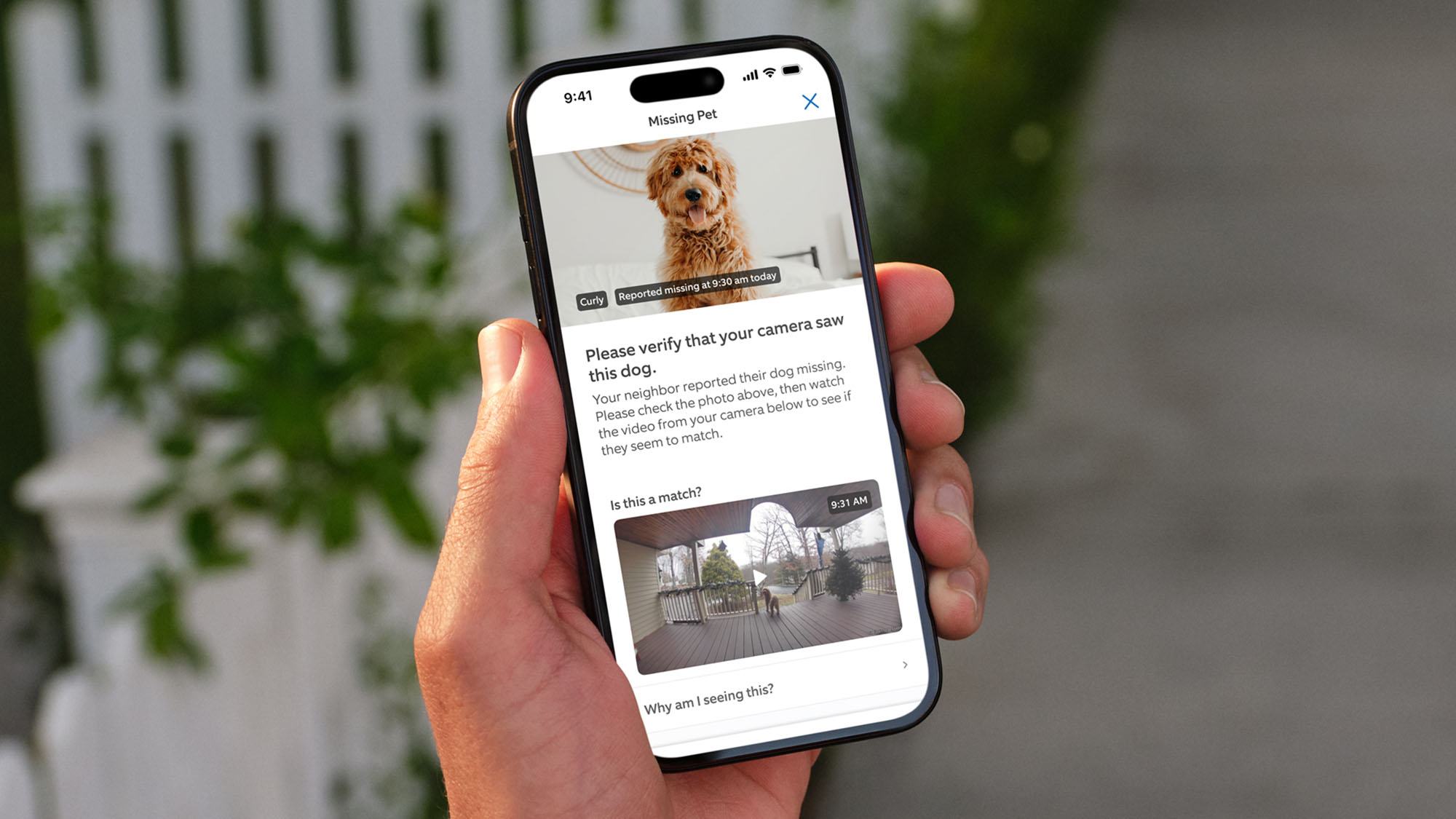

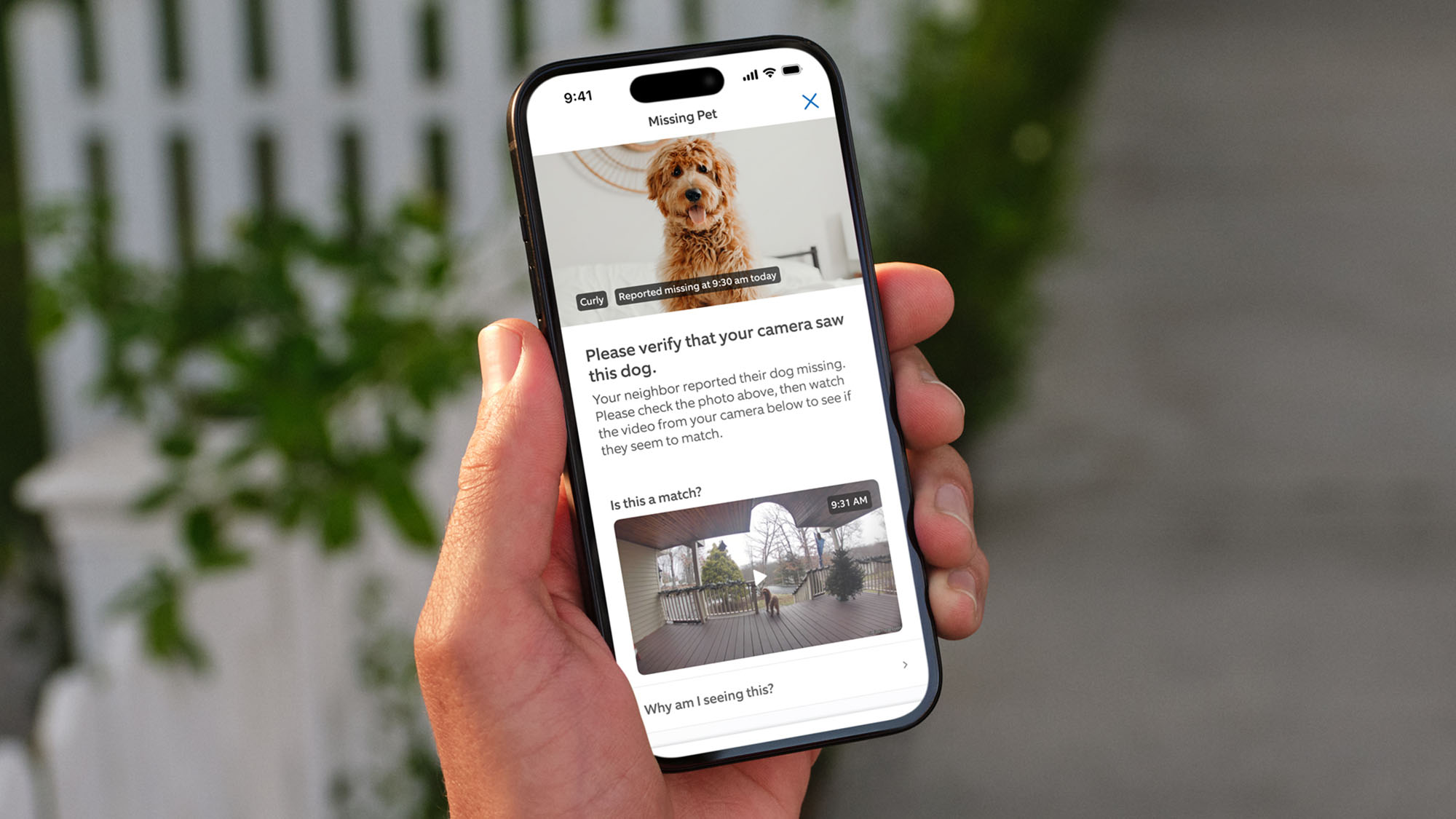

Ring's Search Party is an AI-powered feature that scans footage from neighborhood Ring cameras to locate missing animals. The way it works on paper is straightforward: a pet owner reports their dog missing through Ring's Neighbors app, uploads a photo of the dog, and the system automatically searches through video footage collected by other Ring cameras in the neighborhood. This process is explained in detail in CNET's coverage.

When the AI identifies a potential match, it alerts the camera owner who captured the footage. That person can then choose to share the video with the missing pet's owner through the app. Theoretically, this creates a community-powered search network without requiring human intervention to sift through hours of video.

The feature represents Ring's continued investment in artificial intelligence and computer vision technology. The company has been expanding its AI capabilities for years, but Search Party marks a significant escalation: it's the first Ring feature that automatically scans video footage across multiple households without explicit per-incident consent, as reported by Amazon.

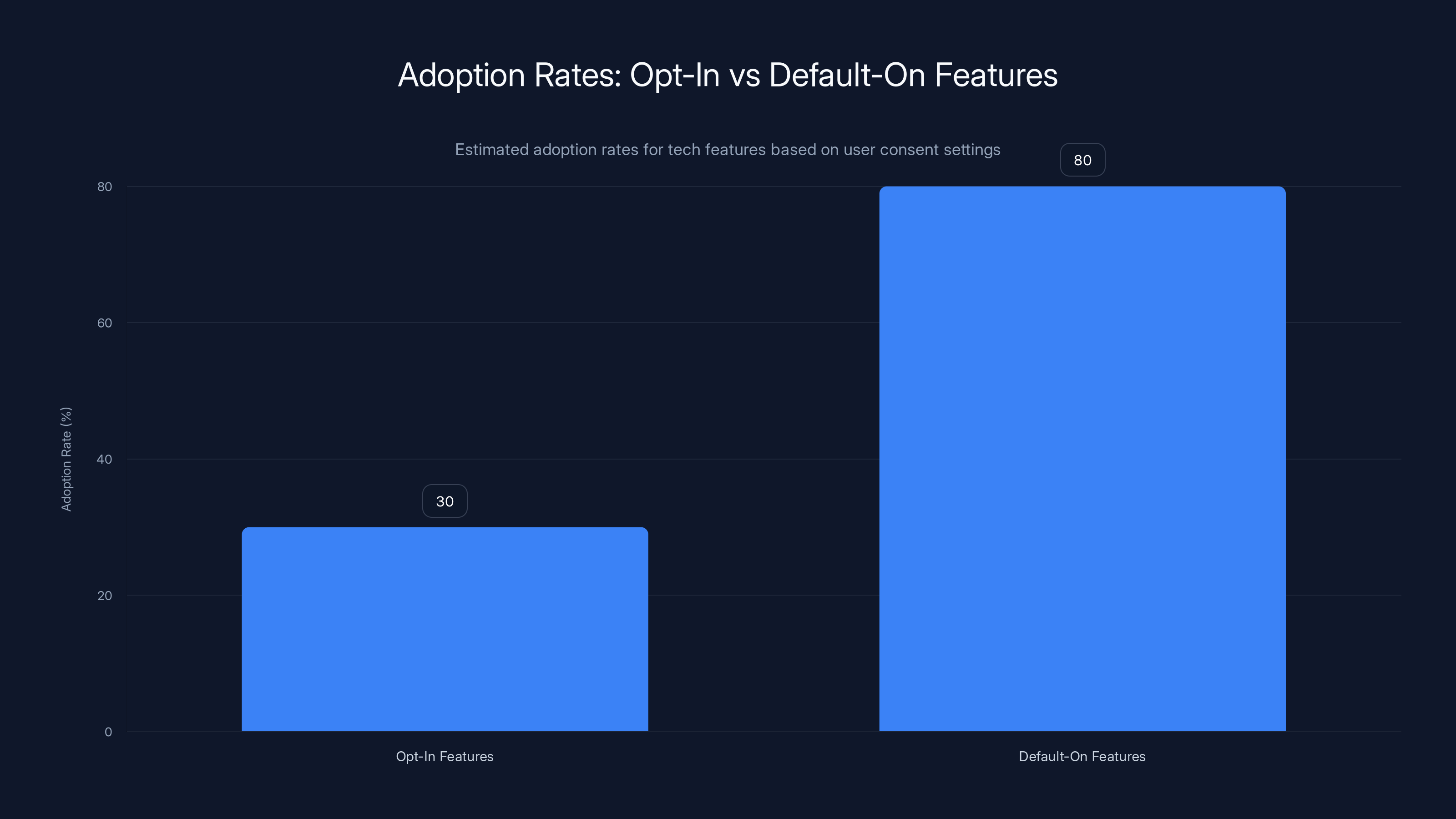

What makes Search Party different from previous Ring features is its default-on status. If you have an outdoor Ring camera and an active Ring Protect subscription, Search Party is enabled automatically. You have to actively opt out to disable it. This represents a shift from Ring's typical approach, where most AI features require user activation, as highlighted by Lifehacker.

The company has emphasized that Search Party is currently designed to match dog images specifically and cannot process human biometrics. Ring spokesperson Emma Daniels told media outlets that the feature is "not capable of processing human biometrics" and that it operates as a separate system from Ring's Familiar Faces facial recognition capability, according to GeekWire.

But that distinction matters less than you might think. The infrastructure is there. The capability exists. And once a technology infrastructure exists, regulatory barriers to expanding it tend to erode over time.

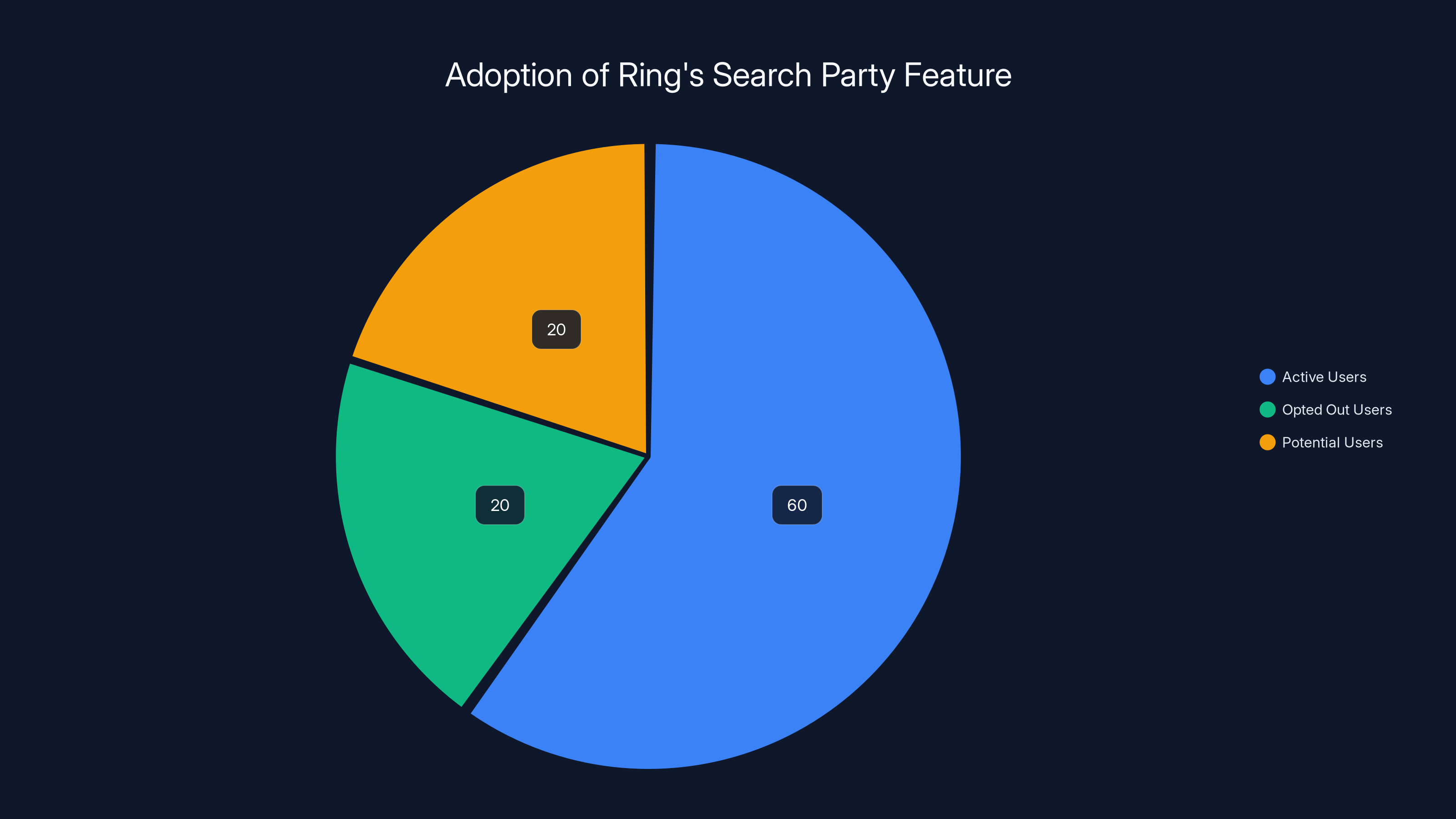

Estimated data suggests that 60% of Ring users with outdoor cameras have the Search Party feature active, while 20% have opted out. Another 20% are potential users who may adopt the feature.

The Super Bowl Ad That Backfired

The timing of Ring's Super Bowl ad in early February 2025 couldn't have been worse. The company had apparently decided that a prime-time commercial featuring neighborhood surveillance systems was the perfect way to promote Search Party to millions of viewers, as discussed in The Verge.

The ad showed Ring cameras activating across a suburban neighborhood, each one recording and scanning for the lost dog. The visual presentation made the surveillance feel coordinated, automated, and total. No privacy zones. No opt-in from the camera owners whose footage was being scanned. Just a network of devices working together to identify and locate a specific subject.

The marketing department probably thought they'd created something heartwarming. Neighbors helping neighbors. Technology solving a real problem. Community values expressed through connected devices.

What they actually created was a perfect visualization of the mass surveillance infrastructure that privacy advocates have been warning about for years, as noted by Truthout.

The response on social media was swift and brutal. Comments on the YouTube video ranged from "This is a huge problem disguised as a solution" to "Smart way to gaslight people into accepting mass surveillance." On X (formerly Twitter), the backlash gained momentum as privacy advocates, lawmakers, and ordinary people expressed alarm at what the ad represented.

Senator Ed Markey, a vocal critic of Ring's law enforcement partnerships, posted: "This definitely isn't about dogs — it's about mass surveillance." Markey has long pressed the company for greater transparency about its relationships with law enforcement and stronger privacy protections, as reported by GeekWire.

The problem Ring faced was that they'd essentially created a commercial for their critics. They'd built and demonstrated exactly the system that privacy advocates feared: an AI-powered platform that could identify and track specific subjects across an interconnected network of cameras covering an entire neighborhood.

The fact that it's currently limited to dogs is almost beside the point. The infrastructure is AI-agnostic. The same system that identifies dogs can identify people. It's not a matter of capability—it's purely a matter of training data and policy.

The Flock Safety Partnership and Law Enforcement Ties

Understanding the backlash requires understanding Ring's partnership with Flock Safety, a company that operates one of America's largest private surveillance networks, as detailed in American Immigration Council.

Flock Safety manufactures automated license plate readers (ALPRs) and fixed camera systems that are deployed in neighborhoods across the country. The company operates what amounts to a nationwide database of vehicle movements and visual surveillance data. More importantly for this story, Flock has extensive relationships with law enforcement agencies that use its platform to investigate crimes.

Ring's partnership with Flock connects two massive surveillance networks. Ring brings the residential camera footage. Flock brings the ALPR data and the law enforcement integration. Together, they create a more comprehensive surveillance infrastructure, as reported by GeekWire.

The concern here isn't hypothetical. Flock Safety has, according to reporting from multiple outlets, allowed immigration and customs enforcement (ICE) to access its camera network data. The company has denied some of these claims, but the basic fact remains: Flock has law enforcement relationships that extend beyond local police departments.

When Ring announced the partnership, they positioned it as improving the capabilities of Community Requests, a feature that allows Ring users to share footage with law enforcement during active investigations. Previously, Community Requests went through Axon (the company behind Taser) as an intermediary. Now Flock handles some of that integration.

On the surface, this seems like a technical detail. In reality, it's the integration point between residential surveillance and professional law enforcement surveillance. It's the connection that turns a collection of individual camera networks into something more like a unified surveillance system.

Privacy experts have pointed out that this partnership, combined with Search Party's capabilities, creates concerning possibilities. If law enforcement could get access to the same AI-powered search capability that finds lost dogs, they could use it to identify and track specific individuals across an entire neighborhood or city, as highlighted by EPIC.

Ring maintains that Search Party is separate from law enforcement integration and that it's not designed to process human facial data. But the company has also said they "don't comment on feature roadmaps," which leaves open the possibility that future versions could work differently.

Privacy and law enforcement partnerships are the top concerns about Ring's Search Party feature. Estimated data based on public discourse.

Facial Recognition and the Familiar Faces Feature

Ring's broader context includes its existing facial recognition system, called Familiar Faces. This feature allows Ring users to upload photos of people they want to monitor, and the camera will alert them when those people appear on their doorbell camera.

Familiar Faces is, in theory, an opt-in feature that operates at the account level. You choose to enroll in it, you upload the photos you want to monitor, and you receive alerts when matches are detected on your camera.

But here's where the concern becomes more acute: Familiar Faces is currently separate from Search Party, but there's nothing preventing Ring from integrating these systems in the future. The technology stack exists. The AI models exist. What would prevent Ring from applying the same search logic that finds dogs to Familiar Faces and allowing users to search for specific people across neighborhood cameras?

Ring has consistently denied that they're planning to build human search capabilities. Emma Daniels stated: "The way these features are built, they are not capable of that today. We don't comment on feature road maps, but I have no knowledge or indication that we're building features like that at this point," as reported by GeekWire.

That statement contains some important caveats. "At this point" suggests future possibilities. "We don't comment on feature roadmaps" is corporate-speak for "we're not telling you what we're building." And "not capable of that today" emphasizes present tense, not permanent incapability.

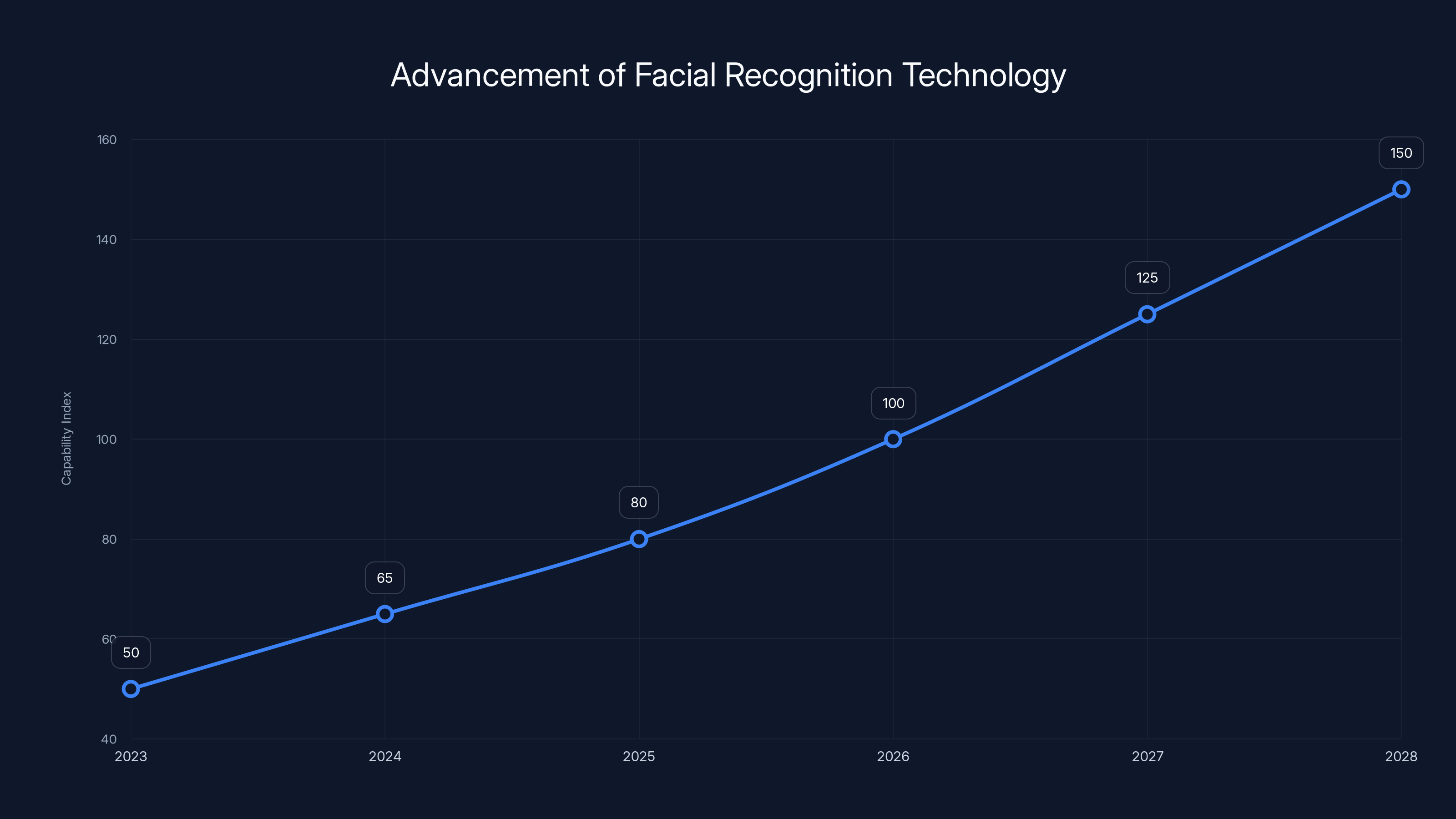

The trajectory matters here. Facial recognition technology has become exponentially more powerful over the past five years. Ring's own AI capabilities have advanced substantially. What seems implausible today might feel inevitable in 2027 or 2028.

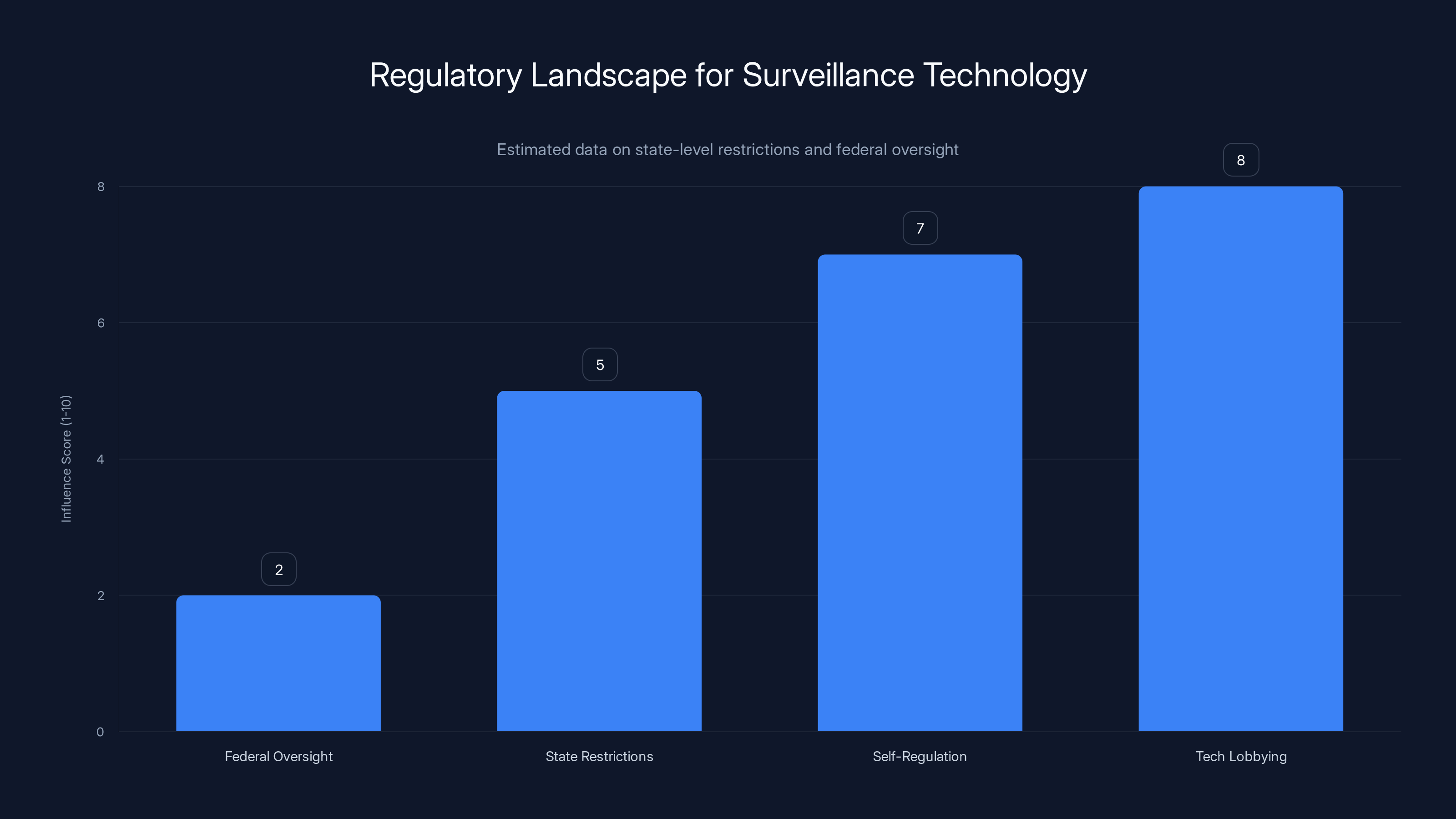

Meanwhile, the legal and regulatory framework hasn't kept pace. There are no federal laws explicitly prohibiting facial recognition. Individual states have passed some restrictions, but the patchwork of regulations is fragmented. Ring is operating in a space where the technology is advancing faster than the governance.

The Default-On Problem

One of the most controversial aspects of Search Party is that it's enabled by default. This represents a shift from how Ring has approached AI features in the past.

Familiar Faces requires users to explicitly opt in. The feature is not active unless you decide to activate it. Search Party, by contrast, is active on any camera with an active Ring Protect subscription unless you specifically disable it.

This distinction is significant because default-on features change the privacy calculus. When a feature is opt-in, you're making an active choice to participate. When a feature is default-on, you're participating unless you take action to stop it. Most users never change default settings.

The default-on approach means that Ring is automatically enrolling millions of households in a surveillance system they may not have actively consented to. Yes, technically you can opt out. But how many of the millions of Ring users even know Search Party exists? How many have gone into their settings to disable it?

Even Ring seemed to acknowledge this issue when they recommended that users review their Search Party settings. If the feature wasn't controversial, why would the company need to tell people to check their settings?

The default-on issue also raises questions about informed consent. When you purchase a Ring doorbell, you're not buying it with the expectation that your video feeds will automatically be scanned and processed by AI systems searching for missing dogs. That feature is added later, often through firmware updates that most users never actively review.

This approach to defaults has become a common pattern in tech. Make the invasive feature default-on, bury the opt-out in a settings menu, and most users won't disable it. The company gets the data and functionality they want. Users get a slightly easier experience. Privacy takes a back seat.

Senator Ed Markey's Ongoing Campaign

Senator Ed Markey from Massachusetts has emerged as one of Ring's most persistent critics in Congress. Long before the Search Party backlash, Markey had been pressing the company on its law enforcement partnerships and privacy practices.

Markey's concerns are rooted in detailed investigation into Ring's actual practices. The company has shared footage with law enforcement through a program that provided law enforcement with special access to Ring's customer database. The company has partnered with police departments in hundreds of cities. These aren't theoretical concerns—they're documented facts about how Ring operates.

In 2022, Markey sent a formal letter to Amazon asking for detailed information about Ring's law enforcement partnerships, data retention practices, and security measures. The company responded, but advocates argued the response lacked crucial transparency, as noted by GeekWire.

When Search Party was announced, Markey was quick to voice concerns. His public statement—"This definitely isn't about dogs — it's about mass surveillance"—captured the core concern many people shared. The feature's framing doesn't match its functionality.

Markey has also advocated for stronger privacy legislation that would require companies like Ring to get explicit consent before sharing data with third parties, including law enforcement. He's pushed for requirements that law enforcement obtain warrants before accessing footage, rather than relying on the voluntary cooperation that currently exists.

The senator's criticism carries weight in Washington because he's backed it up with detailed investigation and concrete legislative proposals. He's not just complaining about Ring—he's actively working on regulatory solutions.

Facial recognition technology is projected to grow significantly, with capabilities potentially tripling by 2028. Estimated data based on current trends.

Privacy Expert Chris Gilliard's Assessment

Privacy researcher Chris Gilliard, speaking to media outlets about Ring's Search Party ad, offered a particularly cutting assessment. He called the commercial "a clumsy attempt by Ring to put a cuddly face on a rather dystopian reality: widespread networked surveillance by a company that has cozy relationships with law enforcement and other equally invasive surveillance companies," as reported by GeekWire.

Gilliard's critique cuts to the heart of the issue. The ad isn't just marketing a product feature. It's presenting a vision of how neighborhood surveillance should function. Cameras everywhere. AI identifying subjects. Information flowing through networked systems. All presented as normal, beneficial, and community-focused.

But that vision, if fully realized, represents something closer to a panopticon than a neighborhood watch program. And the concerning part is that Ring doesn't have to trick people into accepting it. The company can just make Search Party default-on, market it sympathetically, and let inertia do the heavy lifting.

Gilliard's work has consistently focused on how surveillance technology gets embedded into communities with minimal resistance because it's presented through the frame of solving specific, sympathetic problems. Lost dogs. Catching porch pirates. Finding missing persons. Each individual feature seems reasonable. But collectively, they add up to comprehensive neighborhood surveillance.

The power of Gilliard's critique is that he's not arguing that Ring is necessarily planning something nefarious. He's arguing that the infrastructure they're building could easily be repurposed for that, and the company's law enforcement partnerships suggest at least openness to such repurposing.

How Search Party Actually Works: The Technical Reality

Understanding the technical reality of Search Party is important for evaluating the privacy concerns people are raising.

When a dog goes missing and the owner uploads a photo to the Neighbors app, that image is processed by Ring's cloud-based AI systems. The AI generates a computer vision model of the dog's identifying characteristics: size, color, shape, distinctive markings, posture, movement patterns.

That model is then queried against the entire database of footage from Ring cameras in the relevant geographic area. The AI scans through hours of video footage looking for frames that match the dog profile. When potential matches are found, the system scores them based on confidence levels. High-confidence matches are then surfaced to the camera owners.

This is undeniably sophisticated technology. The AI has to be able to identify specific subjects across different camera angles, lighting conditions, and video qualities. It has to work with partial matches and poor-quality footage. It has to do this at scale across thousands of cameras.

But here's the thing: this same technical approach works equally well for finding people instead of dogs. You swap out the dog identification model for a facial recognition model, and you have a system for searching for specific individuals across an entire neighborhood.

The training data would be different. The confidence thresholds might need adjustment. But the fundamental infrastructure is the same.

Ring maintains they're not building this capability, and there's no publicly available evidence that they are. But the fact that they're not building it today doesn't mean it won't exist tomorrow. And once the technology exists and the user base is accustomed to this style of searching, regulatory and legal barriers to expanding it are much lower.

The Community Requests Integration and Law Enforcement Access

Ring's Community Requests feature is where the law enforcement integration becomes explicit. When police are investigating a crime, they can request footage from Ring users in a specific geographic area. Ring users receive a notification that law enforcement has requested footage and can choose whether to share it.

On the surface, this seems reasonable. If someone's been robbed or a vehicle stolen, law enforcement should be able to ask for relevant footage. The user still has the choice whether to share.

But the integration with Flock Safety changes the nature of this feature. Community Requests now goes through Flock rather than directly from law enforcement. Flock becomes the intermediary managing these requests.

The concern is that this integration creates the infrastructure for police to access not just individual pieces of footage that users choose to share, but potentially to query the entire database using law enforcement capabilities. A police officer could, theoretically, use Flock's systems to search Ring's database for footage matching a specific person or vehicle across a broader area.

Ring says that's not how it works today. Community Requests still requires user consent. But again, we're dealing with infrastructure that could enable broader access if policies changed.

The Flock partnership also raises questions about data retention and deletion. How long does Flock retain data from the Ring network? What happens when a user deletes footage from their Ring app? Does it get deleted from Flock's systems? These details matter but are rarely disclosed in any transparent way.

Default-on features typically have higher adoption rates (80%) compared to opt-in features (30%), highlighting the impact of user consent settings on feature utilization. Estimated data.

The Difference Between Search Party and Familiar Faces

Ring has been at pains to explain that Search Party is separate from Familiar Faces and operates under different rules. This distinction is important for understanding the company's current stance on facial recognition.

Familiar Faces is a facial recognition system that operates at the account level. You upload photos of people you want to monitor. Your camera alerts you when those people appear in its field of view. No one else's cameras participate. No data is shared. It's a personal surveillance tool.

Search Party, by contrast, is a communal system. When you search for your lost dog, you're querying video from other people's cameras. Other people's footage is being scanned by the system. This creates a shared surveillance infrastructure.

The technical difference is significant. Familiar Faces doesn't require integration with other cameras because it only operates on your own footage. Search Party requires integration across multiple households and devices.

Ring's claim is that you can't use Familiar Faces for the kind of communal searching that Search Party enables. You can't upload a photo of someone you want to find and have it search across neighborhood cameras.

But why not? Technically, the same AI models that power Search Party's dog identification could, with different training data, power a person-finding system. And technically, it could operate on a communal basis just like Search Party.

The reason you can't do this today is policy, not technical capability. Ring's current policy says Search Party is for dogs only and Familiar Faces is for personal monitoring only. But policies change. Regulations change. Competitive pressures change.

What the Super Bowl Ad Revealed About Marketing a Surveillance Network

The fact that Ring decided to feature Search Party in a Super Bowl ad tells you something about how the company views this technology. They don't see it as creepy or concerning. They see it as a feature worth celebrating during the most-watched advertising event in America.

This confidence might be justified. Most people are genuinely indifferent to surveillance when it's presented as solving a problem they care about. The guy whose bike got stolen doesn't care if Ring cameras are tracking neighborhood activity. He cares about finding his bike. And if facial recognition systems could help catch thieves, many people would probably support that.

The marketing strategy here is sophisticated. Feature a sympathetic problem (lost dog). Show technology solving it. Present the solution as community-oriented and helpful. Avoid mentioning law enforcement relationships or the default-on nature of the feature. Imply that this is how neighborhoods should work.

Done well, this marketing can reshape norms around surveillance. If enough people see Search Party as a normal neighborhood feature, then expanding it to other purposes becomes easier. "We already scan for dogs. Scanning for missing people is just a logical extension. You've already accepted this surveillance paradigm; now we're just applying it more broadly."

The backlash to the ad suggests that not everyone is convinced by this framing. But the marketing will probably work on most people most of the time. It's effective propaganda because it's rooted in something true: the technology can be genuinely useful.

Default Settings and User Consent Issues

One of the most significant concerns raised about Search Party is the default-on status. This raises broader questions about how tech companies should handle consent and privacy.

When you buy a Ring doorbell, you understand that it will record video. Recording is the primary function of the device. You're buying it partly because it records. So when you activate a Ring camera, you're consenting to recording.

But you're not necessarily consenting to have that recording scanned by AI systems searching for other people's lost dogs. That's a secondary, derivative use of the data. It's more invasive than simple recording because it involves AI processing, cross-camera correlation, and information sharing with other households.

Default-on settings for secondary uses raise ethical questions. If Ring really believed Search Party was innocuous and widely acceptable, why make it default-on? Why not make it opt-in like Familiar Faces?

The answer is probably that opt-in features have lower adoption rates. If Search Party were opt-in, many fewer people would have it active. That would limit the feature's utility because you need critical mass of cameras across a neighborhood for the search function to work.

So Ring faced a choice: make the feature opt-in and accept lower adoption, or make it default-on and maximize its reach. They chose the latter. This is a reasonable business decision, but it comes at the cost of privacy for users who never explicitly agreed to participate.

The problem becomes more acute when you consider that most Ring users don't actively engage with their privacy settings. They buy a doorbell, set it up, and forget about it. They don't regularly review settings to see what new features have been added or enabled. Default-on features capture those passive users and enroll them in systems they never explicitly agreed to.

Estimated data suggests that self-regulation and tech lobbying have higher influence scores compared to federal oversight and state restrictions in the surveillance technology sector.

Regulatory Response and Political Pressure

The backlash to Search Party has attracted political attention beyond Senator Markey. Multiple legislators have called for stronger oversight of Ring's practices and clearer restrictions on how surveillance data can be used.

The problem is that the regulatory landscape for surveillance technology is fragmented and slow-moving. No federal law explicitly restricts facial recognition or AI-powered surveillance. Individual states have passed varying restrictions, but they're inconsistent and often contain loopholes.

Meanwhile, companies like Ring are operating in this regulatory gray zone, building more sophisticated surveillance infrastructure and expanding its capabilities. By the time regulations catch up, the technology and the user behavior patterns are already established.

Congress could pass legislation restricting how Ring can use video data, requiring warrants for law enforcement access, or prohibiting certain types of AI processing without explicit consent. But legislative action is slow and faces resistance from tech industry lobbying.

So for now, companies like Ring largely police themselves. Ring says Search Party is separate from law enforcement integration. Ring says they're not building facial recognition search capabilities. Ring says they're being transparent about their practices.

But transparency and self-regulation only go so far when the incentives point toward building more surveillance capability and the competitive pressure from other companies doing the same is substantial.

The Broader Surveillance Ecosystem

Ring doesn't exist in isolation. It's one piece of a larger surveillance infrastructure that's being built across America.

Cities are installing public surveillance cameras. Businesses are deploying their own systems. Vehicle tracking technology is becoming ubiquitous. License plate readers are proliferating. Facial recognition is being deployed in airports and other public spaces. Cell phone location data is being bought and sold.

Individually, each of these systems might seem justifiable. Cameras help catch criminals. Location data helps businesses understand customer patterns. Public safety is important.

But collectively, they add up to something quite different: comprehensive surveillance coverage of most urban and suburban Americans. You're tracked when you leave your house. You're recorded on your doorbell. Your vehicle is photographed by dozens of systems as you drive. Your location is logged and sold. Your face is identified and matched against databases.

Ring is a significant part of this ecosystem because of its residential reach. Ring has hundreds of millions of cameras across neighborhoods in thousands of cities. When that network is integrated with other surveillance systems—Flock's license plate readers, law enforcement databases, traffic cameras—you get comprehensive surveillance.

The concerning part is that much of this infrastructure is being built incrementally, with each individual component presented as solving a specific, relatively benign problem. The fact that it all adds up to comprehensive surveillance is often obscured by the framing of individual features.

What Ring Says vs. What the Technology Enables

There's always a gap between what a tech company says its product does and what the technology could potentially do. Ring is being careful to narrow that gap by explicitly stating that Search Party can't currently identify humans and that it's not designed to work with law enforcement.

But the technology is agnostic. The AI models that identify dogs can be retrained to identify people. The infrastructure that searches across communal cameras can be applied to any subject. The integration with Flock and law enforcement access points already exist.

Ring's current limitations are policy-based, not technical limitations. And policies change. They change when companies decide they need to change. They change when regulators mandate change. They change when competitors are doing something similar.

So when Ring says "Search Party is not capable of processing human biometrics," that's technically true today. But that statement also contains an implicit future possibility: someday it might be capable.

This is why privacy advocates are concerned. They're not arguing that Ring is currently using facial recognition to search for people. They're arguing that the infrastructure is being built to enable exactly that, and the company's track record with law enforcement suggests they'd be open to such applications.

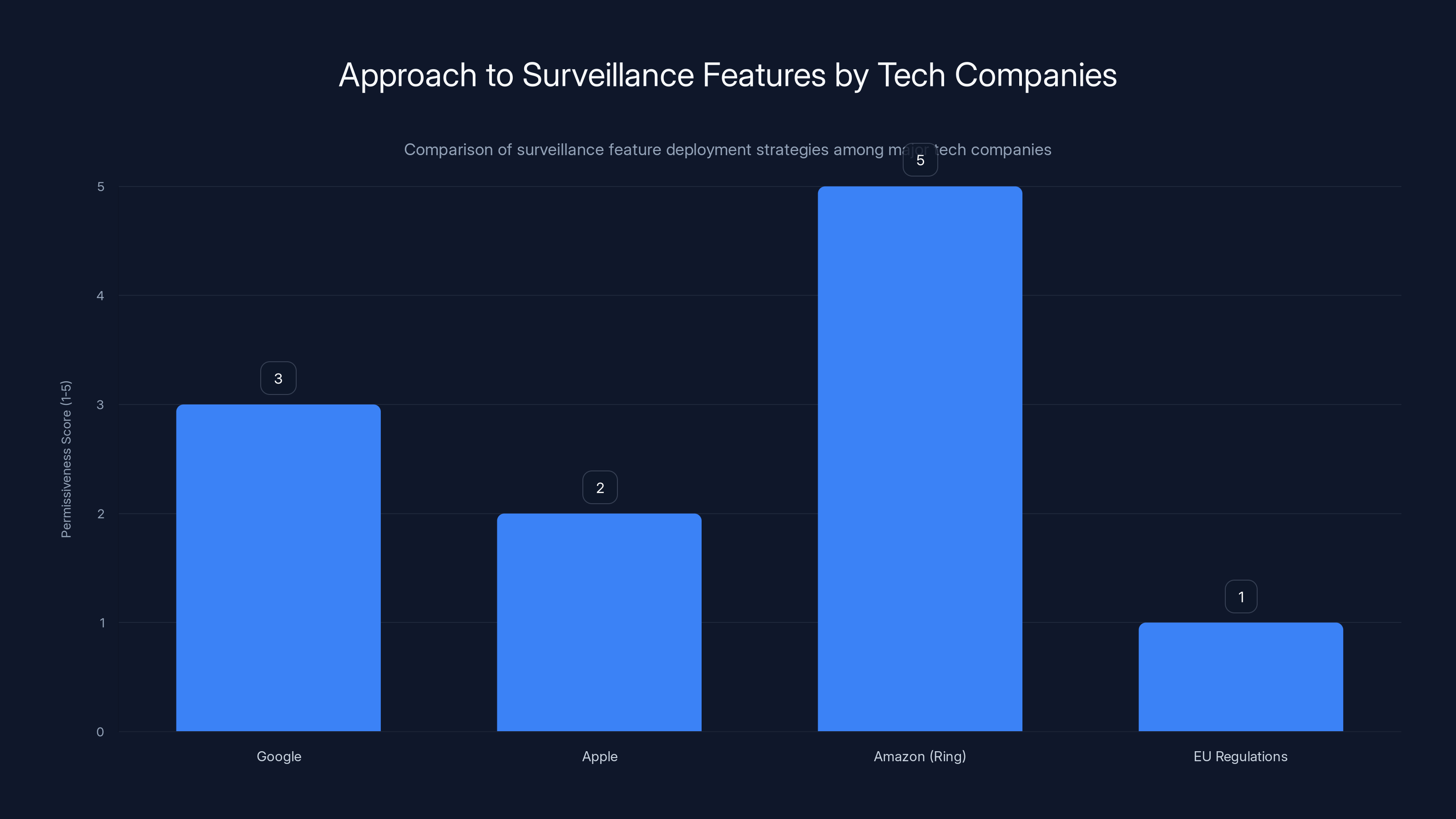

Amazon's Ring is the most permissive with surveillance features, while the EU regulations enforce the strictest controls. Estimated data based on qualitative analysis.

The Lost Dog Use Case: Genuinely Useful or Trojan Horse?

Here's the thing that complicates the criticism of Search Party: it actually is useful for finding lost dogs.

If you're a dog owner and your pet goes missing, having an AI system search through neighborhood footage to find them is genuinely valuable. It's better than the previous option of calling shelters and putting up physical posters.

So is Search Party a good feature? In isolation, yes. Does it solve a real problem? Yes. Would most people welcome the ability to find their lost pet more effectively? Probably yes.

But that genuine utility doesn't negate the concerns about the broader surveillance infrastructure it's part of. Something can be simultaneously useful and concerning. Something can be helping people find their pets while also establishing infrastructure that could be misused.

This is the hardest thing about surveillance technology criticism: the features often work and are often genuinely helpful. You can't argue that Search Party is ineffective. The AI is sophisticated and works well. The communal search network is actually a clever use of already-existing camera infrastructure.

The problem isn't that Search Party is useless. The problem is that it's useful in ways that establish precedent for broader surveillance capabilities.

Once people are accustomed to AI scanning neighborhood cameras looking for specific subjects (dogs), expanding that to other purposes becomes easier. Once the integration with law enforcement exists (through Flock), accessing that system for broader purposes becomes easier. Once the default-on infrastructure is in place, maintaining it for other applications becomes easier.

This is how surveillance infrastructure tends to grow: one useful application at a time, each one establishing precedent for the next.

Comparative Context: How Other Tech Companies Handle Surveillance Features

Ring is not the only company building surveillance technology, and understanding how other companies approach these issues provides useful context.

Google has facial recognition capabilities in its Nest camera system but has been more cautious about deploying them broadly. Google disabled certain facial recognition features and maintains tighter controls over which features are available in which markets, partly in response to privacy concerns and regulatory pressure.

Apple has invested heavily in on-device processing to avoid centralizing sensitive data. Apple's approach is to do as much processing as possible on the device itself rather than sending data to Apple's servers. This is partly a privacy feature and partly a marketing positioning.

Amazon's approach with Ring is more permissive. The company is willing to deploy features more aggressively and deal with backlash afterward. Amazon has also been more comfortable with law enforcement partnerships and data sharing.

These different approaches suggest that there's a spectrum of how companies can handle surveillance technology. Ring is toward the permissive end of that spectrum.

Regulatory developments in the European Union provide another comparative point. The EU's regulations on facial recognition are stricter than anything in the US. Companies operating in Europe have to be more careful about deploying facial recognition systems, which suggests that stricter regulation is feasible.

The Missing Piece: Clear Legal Framework

Underlying all of these concerns is a missing element: clear legal framework governing surveillance technology.

In many European countries, facial recognition is heavily regulated or outright banned in certain contexts. Police use of facial recognition requires warrants. Companies have strict obligations around consent and data processing. The legal framework established before the technology became widespread.

In the US, the approach has been more reactive. Technology gets deployed. People complain. Regulators slowly develop rules. By that time, the technology is already embedded in millions of devices and millions of people's lives.

This reactive approach advantages companies like Ring. They get to build out their infrastructure while the regulatory environment is still developing. Once the infrastructure is established and users are accustomed to it, regulatory intervention becomes harder.

What's needed is proactive legislation that establishes clear rules about what surveillance features are permissible, what consent is required, how data can be shared, and what access law enforcement can have.

Some states have started moving in this direction. Illinois has strict biometric data laws. California has facial recognition restrictions. But the patchwork is fragmented and full of loopholes.

Federal legislation would help, but it seems unlikely in the current political environment. Tech industry lobbying is formidable, and surveillance tends not to be a top political priority until there's a specific incident that catches public attention.

What Users Can Actually Do About Ring Search Party

If you own Ring cameras and are concerned about Search Party, there are actual steps you can take.

First, you can disable Search Party in your Ring app settings. Go to the device settings for each outdoor camera, find the Search Party option, and toggle it off. It requires going into settings for each device individually, which is inconvenient, but it's doable.

Second, you can delete your Ring footage more aggressively. Ring stores footage in the cloud, and longer retention means more data available for searches. Adjusting your video storage settings to delete older footage more quickly limits what's available to search.

Third, you can be thoughtful about what you capture. Position your cameras to capture your own property but not neighboring properties. The less footage you're capturing of your neighborhood, the less data you're contributing to the communal search infrastructure.

Fourth, you can contact Ring and express your concerns about privacy practices. Ring pays attention to public backlash, as evidenced by their response to the Search Party controversy. Customer feedback does influence company behavior.

Fifth, you can support legislative efforts to strengthen privacy protections around surveillance technology. Contact your representatives about surveillance regulation. Vote for politicians who prioritize privacy. This seems distant but is probably the most impactful thing you can do.

Finally, you can consider whether Ring's ecosystem aligns with your privacy values. If you're deeply concerned about surveillance, Ring might not be the right choice, regardless of the specific features you disable. Competitors like Logitech, Arlo, and others offer security cameras with different privacy approaches.

The Future of Ring's Surveillance Infrastructure

Where does Ring go from here? The company has demonstrated that it's willing to deploy surveillance features even when they attract backlash. Search Party attracted significant criticism, but Ring is not backing down or removing the feature. They're defending it as separate from law enforcement systems.

Based on the company's trajectory, we can expect them to continue expanding their AI capabilities. They'll probably eventually move into areas like package theft detection, vehicle identification, and anomaly detection. These are all technically feasible extensions of their current infrastructure.

The law enforcement integration will probably deepen. Flock Safety is a strategic partner, and integration between Ring's residential cameras and Flock's professional surveillance systems makes sense from Ring's perspective.

Facial recognition might eventually be deployed for communal searches, though Ring will probably frame it very carefully and emphasize limited use cases. "Finding missing persons" is a sympathetic use case, for example.

Meanwhile, competitive pressure from other surveillance companies will push the entire industry in the direction of more capability. If Ring doesn't deploy certain features, competitors will, and they'll gain market advantage by offering more comprehensive surveillance.

So the trajectory seems clear: more surveillance capability, deeper integration with law enforcement systems, and expansion of the data being collected and processed.

The Underlying Values Question

At its core, the Ring Search Party backlash is about values. It's about what kind of society we want to live in.

On one side: more surveillance means more safety. Lost dogs are found. Stolen packages are recovered. Criminals are caught. Crimes are solved. If you value safety and security, more surveillance infrastructure is appealing.

On the other side: comprehensive surveillance creates opportunities for misuse. Authoritarian governments have used surveillance technology to control populations. Minority groups have been disproportionately targeted by surveillance systems. The power to monitor everyone is inherently dangerous, regardless of current intentions.

These perspectives don't have to be mutually exclusive, but they point in different directions when you're building infrastructure. Do you build toward comprehensive surveillance with safeguards? Or do you build with privacy and consent as the primary values?

Ring seems to be building toward the former. That's a legitimate business choice, but it's worth being explicit about it. Ring is building toward comprehensive, networked neighborhood surveillance. The Search Party feature for dogs is part of that trajectory.

The backlash suggests that many people don't want that future. They want to find lost dogs without building comprehensive surveillance infrastructure. They want safety without comprehensive monitoring. They want technology that solves specific problems without establishing precedent for broader surveillance.

Whether that preference translates into actual regulatory or market change remains to be seen. But the Super Bowl ad backlash showed that the public is increasingly aware of what's being built and increasingly uncomfortable with it.

FAQ

What is Ring's Search Party feature?

Ring's Search Party is an AI-powered feature that scans footage from neighborhood Ring cameras to locate missing pets. When a pet owner reports their dog missing through Ring's Neighbors app and uploads a photo, the system automatically searches through video footage collected by other Ring cameras in the area and alerts owners if matches are found.

How does Ring's Search Party work technically?

Search Party uses cloud-based artificial intelligence and computer vision to generate a profile of the missing dog based on identifying characteristics like size, color, markings, and posture. That profile is then queried against the entire database of footage from Ring cameras in the relevant geographic area. When potential matches are found and scored with appropriate confidence levels, the system surfaces them to the camera owners who captured the footage.

Why are people concerned about Search Party if it only searches for dogs?

Critics worry that the infrastructure Ring is building to search for dogs could easily be repurposed to search for people using the same AI and computer vision technology. The capability to identify and track subjects across multiple camera feeds at scale could be adapted for facial recognition searches, especially given Ring's existing partnerships with law enforcement agencies and Flock Safety, a surveillance company with law enforcement contracts.

What is Flock Safety and why does it matter for Ring's Search Party?

Flock Safety operates one of America's largest private surveillance networks using automated license plate readers and fixed camera systems deployed across neighborhoods. Ring's partnership with Flock integrates Ring's residential camera network with Flock's professional surveillance infrastructure and law enforcement connections, potentially creating a more comprehensive surveillance system that links home cameras with law enforcement data.

Is Search Party enabled by default, and what does that mean for privacy?

Yes, Search Party is enabled by default on any outdoor Ring camera with an active Ring Protect subscription. This means users are automatically enrolled in the feature unless they specifically disable it. The default-on approach is controversial because most users never actively review or change default settings, effectively enrolling millions of people in a surveillance system without explicit individual consent.

How is Search Party different from Ring's Familiar Faces facial recognition feature?

Familiar Faces is an opt-in, account-level facial recognition system where you upload photos of people you want to monitor on your own camera. Search Party is a communal system that automatically scans multiple households' cameras for a subject. Familiar Faces currently only works on your own footage, while Search Party searches across neighborhood cameras and doesn't currently support human facial recognition, though the underlying technology could theoretically be adapted for that purpose.

Can I disable Search Party, and if so, how?

Yes, you can disable Search Party in your Ring app settings. For each outdoor camera, go to device settings, find the Search Party option, and toggle it off. You'll need to do this for each camera individually. You can also delete your Ring footage more aggressively by adjusting video storage settings, which limits the amount of data available for searches.

What has Senator Ed Markey said about Ring and Search Party?

Senator Markey has been a vocal critic of Ring's surveillance practices and law enforcement partnerships. Following the Search Party announcement, he stated "This definitely isn't about dogs — it's about mass surveillance." Markey has pushed for greater transparency about Ring's law enforcement relationships and advocated for stronger privacy legislation requiring explicit consent before data sharing with third parties.

What does Amazon Ring say about concerns that Search Party could be used to track people?

Ring spokesperson Emma Daniels stated that Search Party is "not capable of processing human biometrics" and operates separately from Ring's Familiar Faces facial recognition feature. She said the company has no plans to expand Search Party to search for people "at this point" but acknowledged the company doesn't comment on future feature roadmaps, leaving open the possibility of future changes.

What's the broader context of surveillance infrastructure that makes Search Party concerning?

Search Party exists within a larger ecosystem of interconnected surveillance systems including public cameras, license plate readers, law enforcement databases, and data brokers. Individually, each piece might seem justifiable for solving specific problems. Collectively, they create comprehensive surveillance coverage of most Americans, and Ring's residential network is a significant piece of that infrastructure when integrated with law enforcement access points and other surveillance systems.

Final Thoughts: The Future of Privacy in Connected Neighborhoods

The backlash to Ring's Search Party ad represents a moment of public awareness about surveillance infrastructure being built around us. For a brief moment, millions of people watching the Super Bowl were confronted with a visualization of neighborhood surveillance systems working in concert.

But awareness alone doesn't change corporate behavior. Ring will continue deploying features. The surveillance infrastructure will continue expanding. Competitive pressures will push other companies to build similar capabilities.

What might actually change things is if awareness translates into regulatory action. If states and the federal government establish clear rules about consent, data sharing, and law enforcement access, that would reshape what Ring can build.

Otherwise, we're likely headed toward the future that Search Party visualizes: neighborhoods with comprehensive camera coverage, AI systems identifying and tracking subjects, and data flowing to law enforcement and third parties. It might be useful in many ways. Finding lost dogs. Solving crimes. Catching package thieves.

But it will also represent a profound shift in what privacy means when you leave your house. And once that infrastructure is built and normalized, it becomes very hard to unbuild.

Key Takeaways

- Ring's Search Party feature automatically scans neighborhood camera footage to find missing dogs, but critics fear the AI infrastructure could be repurposed for human surveillance

- The feature is enabled by default on all Ring cameras with active subscriptions, raising consent and privacy concerns without explicit user opt-in

- Ring's partnership with Flock Safety, a law enforcement surveillance company, integrates residential cameras with professional surveillance networks and police data access

- The Super Bowl advertisement visualized comprehensive neighborhood surveillance, sparking backlash from privacy advocates and politicians like Senator Ed Markey

- The underlying technology used to identify dogs could technically be adapted for facial recognition searches, making current policy limitations potentially temporary

- Regulatory frameworks for surveillance technology lag behind deployment, allowing companies to build infrastructure that later becomes difficult to restrict

Related Articles

- Amazon Alexa+ Free on Prime: Full Review & Early User Warnings [2025]

- Microsoft Handed FBI Encryption Keys: What This Means for Your Data [2025]

- TikTok's Immigration Status Data Collection Explained [2025]

- Ring's AI Intelligent Assistant Era: Privacy, Security & Innovation [2025]

- Why "Catch a Cheater" Spyware Apps Aren't Legal (Even If You Think They Are) [2025]

- Digital Rights 2025: Spyware, AI Wars & EU Regulations [2025]

![Ring's Search Party Surveillance Feature Sparks Mass Backlash [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/ring-s-search-party-surveillance-feature-sparks-mass-backlas/image-1-1770773807956.png)