Cybersecurity & Surveillance Threats in 2025: A Deep Dive Into Privacy, Smart Devices, and Government Overreach

We're living in a surveillance paradox. On one hand, we willingly hand over our privacy to tech giants in exchange for convenience—Ring doorbells that watch our neighborhoods, Meta smart glasses that record our daily lives, smartphones that track our location constantly. On the other hand, we're rightfully terrified when governments weaponize these same technologies against dissidents, immigrants, and ordinary citizens.

Earlier this year, a major security story shook the tech industry when Ring, the Amazon-owned surveillance company, quietly killed its partnership with Flock Safety, a company that operates dragnet surveillance networks of license plate readers used by law enforcement nationwide. The decision came after intense public backlash following Ring's Super Bowl advertisement featuring a new AI-powered "Search Party" feature designed to help find lost pets. But here's where it gets dark: viewers immediately recognized that the same technology could easily be weaponized to track people, not dogs.

This moment crystallizes the central tension we're facing in 2025. Technology that could help rescue missing children can equally be used to suppress political dissent. Facial recognition that helps locate lost elders can just as easily target immigrant communities. The line between helpful innovation and dystopian surveillance has become impossibly blurry.

The broader security landscape in early 2025 reveals how deeply interconnected our digital lives have become with government power structures, corporate surveillance networks, and emerging AI threats. From Iranian internet shutdowns that reveal a chilling surveillance apparatus, to US immigration enforcement weaponizing biometric technology, to cryptocurrency becoming the currency of human trafficking, the security challenges we face transcend traditional cybersecurity. They're about power, control, and the future of privacy itself.

Let's walk through what's happening right now—and what it means for you.

TL; DR

- Ring cancels Flock Safety partnership after public outcry over AI-powered surveillance integration that could track people, not just lost pets

- Meta plans face recognition in smart glasses despite ethical concerns, citing a "dynamic political environment" that favors new surveillance features

- ICE taps Flock's license plate reader network to hunt immigrants, revealing how private surveillance infrastructure becomes government weapon

- Nuclear weapons inspections may soon use AI instead of in-person verification, fundamentally changing global security verification

- Cryptocurrency trafficking networks doubled in 2024, with hundreds of millions in crypto facilitating human trafficking and forced labor

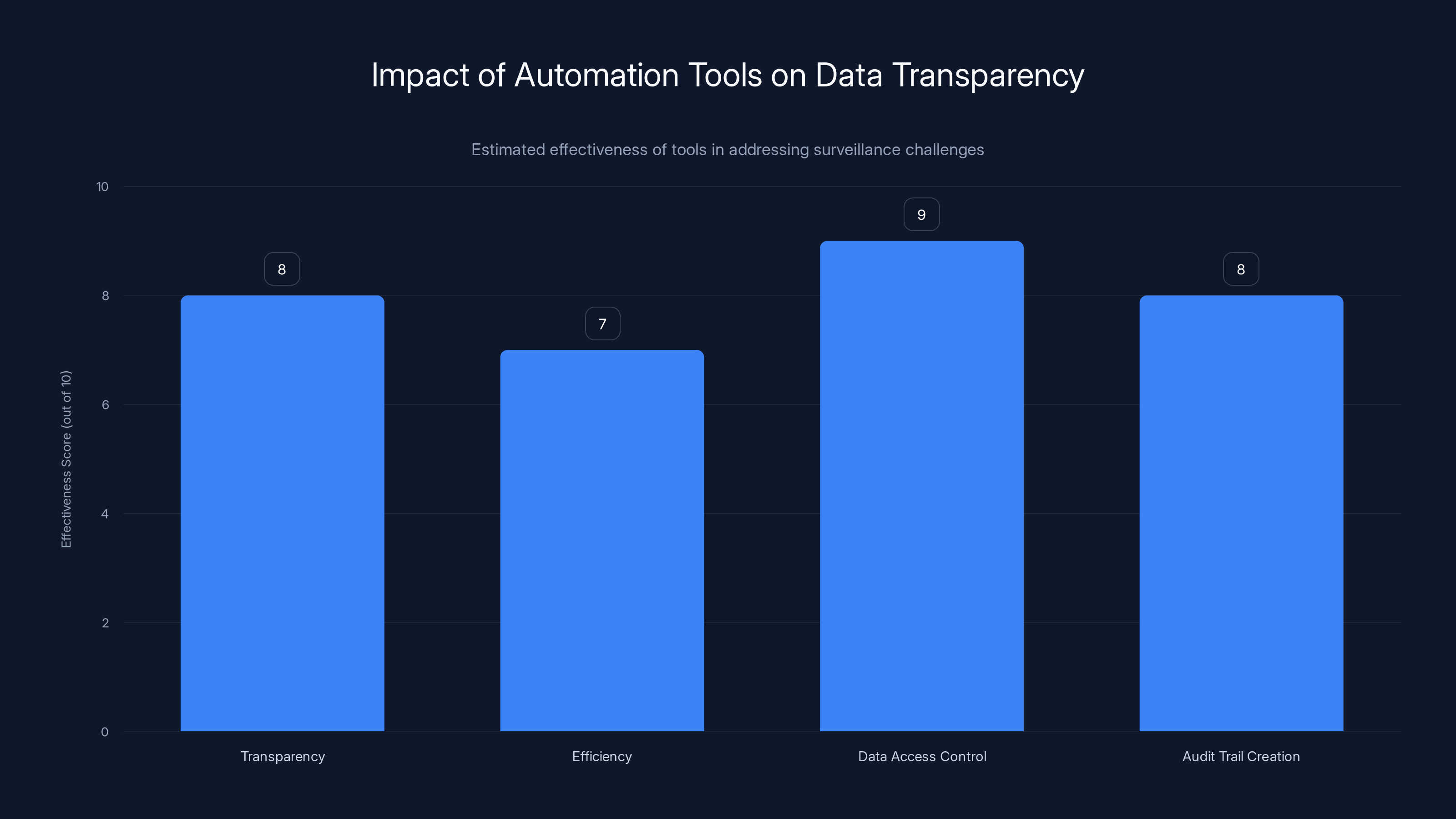

Automation tools like Runable can significantly enhance transparency and control over data access, with high effectiveness in creating audit trails and improving overall efficiency. Estimated data.

Ring's Failed Partnership: When Surveillance Becomes Too Obvious

Ring's decision to kill the Flock Safety partnership represents a rare moment where public pressure actually made a corporation back down on a surveillance integration. But don't mistake this for a victory. It's really just a tactical retreat.

Here's what happened: Ring announced it would integrate its sprawling network of millions of privately owned surveillance cameras with Flock Safety's license plate reader technology. The idea was simple and terrifying in equal measure. Imagine every doorbell camera, every home security camera that Ring owns footage from, getting cross-referenced against every license plate reader that Flock operates across the country. If you drove past a Ring customer's home, that data could be captured, stored, and made searchable to law enforcement.

But then Ring aired that Super Bowl commercial. The ad showcased Search Party, a new AI feature that helps people find lost dogs by scanning surveillance footage from nearby Ring cameras. The feature is genuinely clever from a technical standpoint. It uses computer vision to identify dogs in video feeds, helping owners locate lost pets.

What Ring didn't anticipate was the immediate and obvious public response: "If this finds dogs, it will absolutely be used to find people."

Within days, privacy advocates, civil rights organizations, and ordinary people on social media pointed out the obvious logical extension. A feature that scans video footage to identify animals could identify humans. A system designed to find lost dogs could find hiding immigrants, fugitives, or protest organizers. The technology itself is agnostic about its target.

Ring responded by killing the Flock partnership, claiming in a statement that "after a comprehensive review, we determined that [the] integration would require significantly more time and resources than anticipated." Translation: We're stopping this because the public relations nightmare isn't worth it.

But here's the critical thing to understand: this isn't really about Ring or Flock making an ethical choice. It's about Ring, owned by Amazon, calculating that maintaining customer trust is more valuable than the short-term benefits of the partnership. The technology itself hasn't changed. The capability exists. The infrastructure is there.

What matters is that Ring for years built relationships with law enforcement agencies, allowing police to request footage from Ring customers without warrants. The company only eliminated this practice in early 2024—and only after sustained public pressure. Before that elimination, police could essentially bypass judicial oversight by asking Ring directly for footage instead of obtaining a warrant.

This pattern reveals something crucial about how surveillance capitalism actually works. The features and partnerships don't happen because they're inherently necessary. They happen because they're profitable and technically possible. They only stop when the reputational cost exceeds the financial benefit.

The Mechanics of Modern Surveillance Networks

To understand why the Ring-Flock partnership mattered so much, you need to understand how modern surveillance networks function. They're fundamentally different from the old spy-novel model where a government agency maintains its own surveillance apparatus.

Instead, we have an ecosystem where private companies build surveillance infrastructure under the guise of consumer convenience, and then government agencies tap into that infrastructure when they need it. Flock Safety is perhaps the most explicit example of this model.

Flock operates a vast network of license plate readers installed on traffic cameras, streetlights, and toll booths across the United States. The company has equipped thousands of law enforcement agencies with searchable access to this license plate data. Want to find where a car was at a specific time and place? Just query Flock's database.

The problem is that this technology isn't surgically precise. It's a dragnet. Everyone's movements get captured and stored. And as investigative journalism from 404 Media revealed, Immigration and Customs Enforcement has been surreptitiously tapping into Flock's network to track down immigrants.

ICE didn't ask for special permission. Didn't go through a formal process. The agency simply gained access to a tool that was built and operates as a private commercial service. This is the crucial innovation of modern surveillance: you don't need the government to build the surveillance state when private companies will do it for profit, and law enforcement can simply use what's already there.

Now imagine if Ring's cameras were integrated into this network. Every time a car drove down a residential street with Ring cameras installed—which is most middle-class neighborhoods now—that vehicle's presence would be logged. The potential for abuse becomes exponentially greater.

Flock has argued that its system is necessary for public safety. License plate readers can help police find stolen vehicles, locate crime victims, or track dangerous suspects. These arguments aren't entirely wrong. The technology does have legitimate law enforcement applications.

But here's the problem: there's no meaningful oversight. No process ensures that Flock's data is only used for the legitimate purposes it claims. No restriction prevents it from being used to suppress political dissent or target specific communities. This is why the Ring-Flock integration felt like such a crucial moment to privacy advocates. It represented the expansion of an already-existential surveillance network into even more intimate territory: our homes.

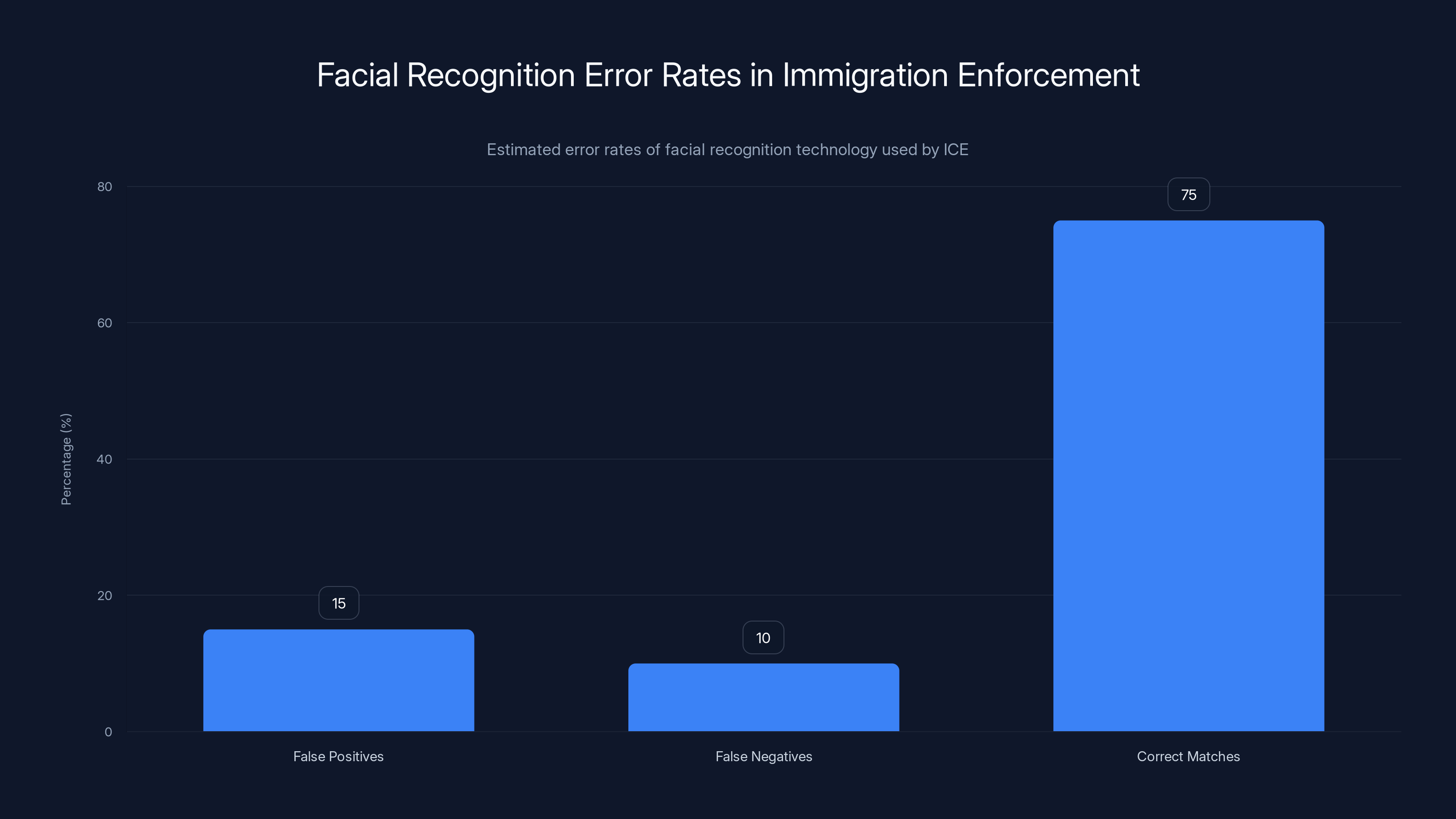

Estimated data shows a significant error rate in facial recognition technology used by ICE, with 15% false positives and 10% false negatives. This highlights the potential for wrongful detention based on incorrect matches.

Meta's Face Recognition Play: Ethical Concerns Go on Pause

While Ring was quietly backing away from mass surveillance expansion, Meta was doing the opposite. The company announced plans to add face recognition capabilities to its smart glasses, specifically a feature internally called "Name Tag."

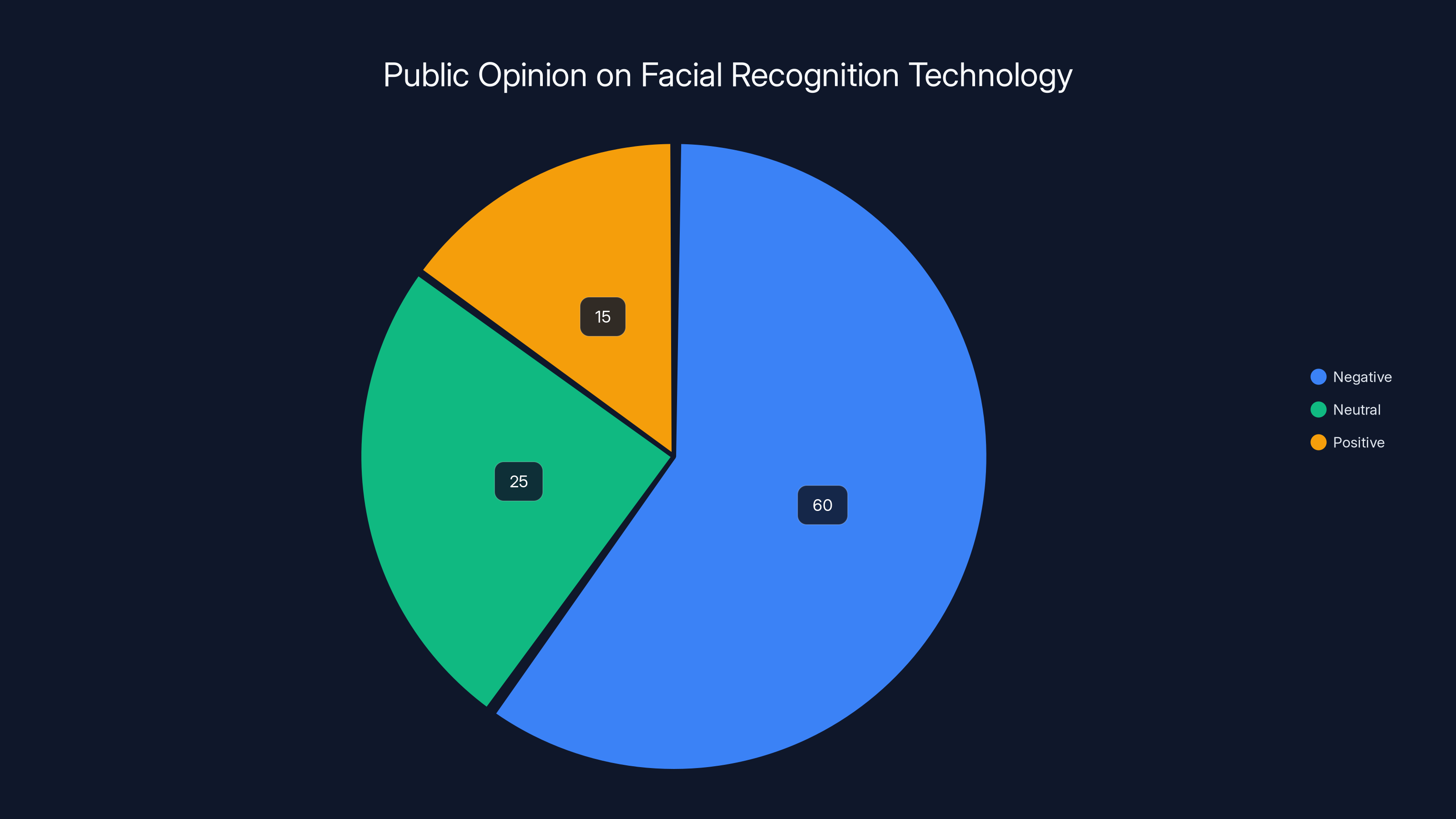

The timing is almost absurdly brazen. Democratic lawmakers have been pushing Immigration and Customs Enforcement to stop using face recognition in the streets. Biometric civil rights organizations have been sounding alarms about the discriminatory impact of facial recognition technology, which performs significantly worse on people with darker skin tones. Public opinion on face recognition in general has turned sharply negative.

So why would Meta introduce this feature now?

According to an internal memo obtained by the New York Times, Meta's reasoning is remarkably cynical: "Many civil society groups that we would expect to attack us would have their resources focused on other concerns." In other words, Meta is banking on the fact that public attention is elsewhere—distracted by immigration enforcement, political chaos, and economic uncertainty. While everyone's looking at immigration policy, maybe nobody will notice when we ship face recognition in the most intimate consumer device available.

Meta's smart glasses, made in partnership with Ray-Ban, are already camera-equipped devices that record the wearer's perspective of the world. Adding face recognition to these glasses would enable something previously relegated to science fiction: real-time identification of anyone you look at.

For perspective, consider what this means in practice. You're walking through a shopping mall wearing Meta smart glasses. You make eye contact with someone at the other end of the corridor. Your glasses identify them by name. Maybe you tap your temple to open their social media profile. Maybe you share what you see with others.

For stalkers, this is a weapon. For employers trying to identify and suppress union organizers, this is a tool. For authoritarian governments, this is infrastructure for total surveillance.

Meta's 2021 decision to exclude face recognition from its first-generation Ray-Ban glasses was presented as an ethical stance. The company said it wanted to avoid the obvious dystopian implications. Now, in 2025, that caution has evaporated.

What changed? Partly, it's the political environment. The Trump administration, which took office in 2025, has been more permissive about surveillance technology. ICE has been actively using face recognition for immigration enforcement. The political pressure that previously constrained Meta's surveillance ambitions has partially dissolved.

But there's another factor: Meta's business model depends on data. The company survives by knowing as much as possible about human behavior. Face recognition data—the ability to identify people in the wild, to track attention patterns, to understand social networks and relationship structures—is incredibly valuable. From Meta's perspective, this isn't just about advertising, though it certainly matters there. It's about building an unprecedented dataset of human interaction and behavior.

The company is betting that by the time the public realizes what's happening, face recognition in smart glasses will already be ubiquitous. That's how technology adoption typically works. The feature seems normal to early adopters. Then it becomes standard. Then it's everywhere. By the time the general public understands the implications, reversing the change becomes nearly impossible.

The Jared Kushner Whistleblower: When Intelligence Agencies Fight Themselves

Beneath the surface of the Ring and Meta stories lies a more shadowy battle over surveillance, intelligence, and political power. An intercepted conversation involving Jared Kushner, the Trump administration's son-in-law and a key figure in some of the most sensitive national security matters, became the subject of a confidential whistleblower complaint against Tulsi Gabbard, the Director of National Intelligence.

The complaint, which has been kept extremely classified, allegedly involved Gabbard limiting the distribution of intelligence about a conversation between two foreign nationals. The conversation partially concerned Iran and national security matters related to Trump administration relatives.

This story is crucial because it reveals how intelligence agencies use surveillance capabilities to fight each other. When you have the technical ability to intercept international communications, you get access to information that's politically explosive. The question becomes not "what should we do with this information?" but "who should we tell about it?"

Kushner has been involved in extraordinarily sensitive national security work, including efforts related to Iran's nuclear program. If a foreign entity was discussing Kushner or Trump family members in communication with Kushner, intelligence agencies would naturally want to track and analyze that conversation. But what happens next is where politics enters intelligence work.

The whistleblower accused Gabbard of deliberately limiting distribution of the intercept, potentially for political reasons. Gabbard's team called the allegations "baseless and politically motivated." But the underlying dispute reveals something important: surveillance creates power. When you control what information gets distributed through intelligence channels, you control what decision-makers know, and thus how decisions get made.

The complaint itself has been heavily redacted, kept secret from Congress and the general public. Congress members were allowed to view a "highly redacted version," meaning the actual details remain unknown outside a tiny circle of officials. This is the reality of national security surveillance: the public is perpetually kept in the dark about how surveillance powers are actually being used.

Iran's Internet Shutdown: Surveillance as a Tool of Political Control

While American debates about surveillance revolve around civil liberties and privacy, in Iran, surveillance has become a tool of literal state murder.

During widespread anti-government protests in 2024, the Iranian regime didn't just kill thousands of demonstrators in the streets. It also cut off internet access to prevent coordination and international attention.

But here's what's particularly chilling: Iran shut down not just access to the global internet, but also access to the country's own internal internet infrastructure, the National Information Network, also known as the Intranet.

New research has found that this internal network is becoming a mechanism of constant, pervasive surveillance. Unlike the fragmented, somewhat-anonymous internet, where data travels through multiple nodes, the National Information Network is centralized. Every packet of data that travels through it can be monitored. Every user activity can be logged. Every interaction can be tracked.

For Iranians, this creates an impossible choice: either stay completely offline, or use the Intranet and accept total surveillance. The network becomes the only way to participate in digital society while the regime maintains complete visibility and control.

This is where surveillance technology reaches its logical endpoint: not as a tool to prevent crime or improve services, but as a mechanism to systematically suppress dissent and maintain authoritarian control. The Iranian model is exactly what privacy advocates worry will happen in democracies if surveillance is normalized and accepted incrementally.

Each small expansion—a security camera network here, a license plate reader network there, facial recognition in smart glasses—seems individually justifiable. But collectively, they create the infrastructure for exactly the kind of total surveillance that Iran has built intentionally.

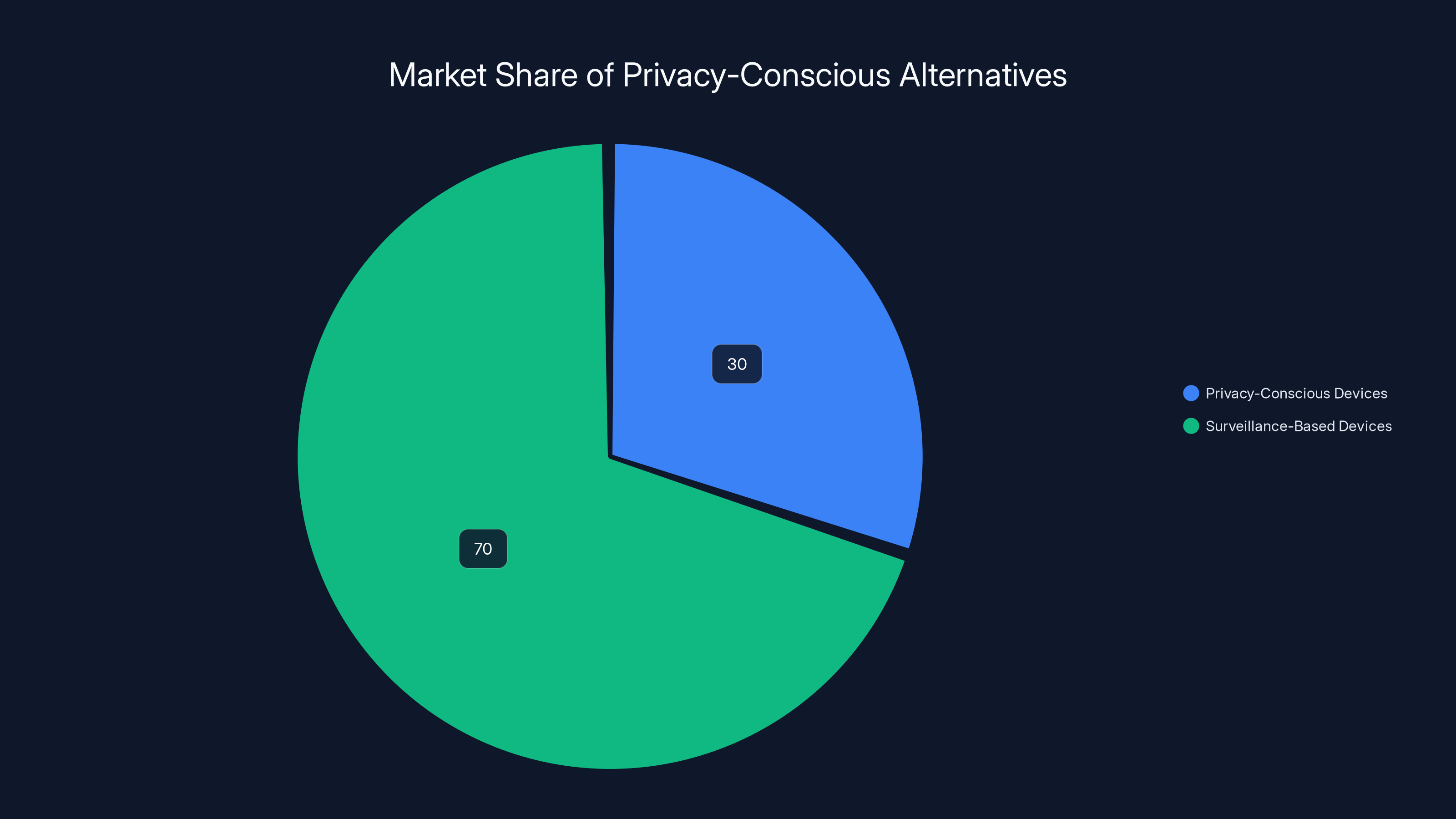

Estimated data shows privacy-conscious devices hold about 30% of the market, reflecting growing awareness but still trailing behind surveillance-based systems.

Nuclear Weapons Inspection Gets an AI Upgrade

We live in a moment of profound transition in how we verify international security agreements. The New START treaty, the last major nuclear weapons agreement between the United States and Russia, just expired. That treaty relied on on-site inspections, where representatives from each country could physically visit the other's nuclear weapons facilities and verify that warhead numbers matched agreed-upon limits.

With the treaty expired, some researchers and analysts are proposing an alternative: AI-powered inspection systems combined with satellite imagery and human reviewers.

The logic seems sound. Instead of sending inspectors to physically tour a weapons facility, you could use satellite imagery combined with AI analysis to detect changes in the facility's infrastructure. Have new buildings been constructed? Has activity increased? Has the facility's heat signature changed in ways suggesting increased weapons production? AI systems can spot patterns in satellite imagery faster and more comprehensively than human analysts.

But here's the problem: this system would constitute permanent, automatic surveillance of both countries' most sensitive military facilities.

With on-site inspections, there's human judgment. An inspector visits, takes a tour, talks to facility managers, asks questions. There's negotiation and flexibility. But with AI-powered surveillance, you have constant, automated monitoring. If the AI flags a potential violation, who makes the determination about what it means? How is conflict resolved?

The proposal reveals how AI is becoming a replacement not just for human labor, but for human judgment and negotiation in critical domains. We're outsourcing decisions about potential nuclear weapons violations to algorithms. That's a profound shift.

Cryptocurrency's Dark Turn: Trafficking and Forced Labor

Cryptocurrency is only 16 years old. For most of that history, it's been pitched as liberatory technology—a way to escape government financial control, to bank the unbanked, to democratize finance.

But reality has been considerably darker.

According to Chainalysis, a crypto-tracing firm that analyzes blockchain transactions, the amount of cryptocurrency involved in human trafficking, prostitution, and forced scamming has nearly doubled in the past year. The company estimates hundreds of millions of dollars in annual cryptocurrency transactions related to these crimes.

That estimate is likely low.

Why has cryptocurrency become the currency of human trafficking? Because it offers exactly what traffickers need: the appearance of anonymity, the ease of cross-border transfer, and the difficulty of regulatory enforcement.

When you sell a person into prostitution or forced labor, you need to move money across borders without detection. Traditional banking systems have reporting requirements and fraud detection. Cryptocurrency offers a workaround. You can receive payment in crypto, convert it to fiat currency in a jurisdiction with weak enforcement, and move the proceeds across borders. Each step of the way, you're obscured by layers of technical obfuscation.

This is the dark side of decentralization: when nobody's in charge, nobody stops the worst abuses either. Cryptocurrency's resistance to government regulation makes it perfectly suited for criminal activity that thrives on regulatory arbitrage.

Chainalysis and other firms are developing better techniques to trace cryptocurrency transactions through the blockchain, even when they're obscured through mixing services or privacy coins. But this creates a new arms race: criminals developing better obfuscation techniques, regulators developing better detection techniques, in an endless cycle.

The broader implication is that certain technologies, when used at scale, will inevitably be co-opted for human harm. Cryptocurrency's supporters originally pitched it as a way to resist tyranny. It's become, in part, a way to facilitate exploitation.

Immigration Enforcement and Facial Recognition: The Weaponization of Biometrics

While we've been debating whether Meta should include face recognition in smart glasses, Immigration and Customs Enforcement has already been weaponizing facial recognition for months.

ICE has signed contracts with facial recognition companies and has been using the technology to identify immigrants in the wild. The agency uses a database of driver's license photos, mugshots, visa applications, and other government-collected biometric data to identify people.

The technology is imperfect, and the consequences are severe. People have been detained based on facial recognition matches that were later determined to be false positives. But the agency has continued expanding the practice because it dramatically increases the number of people it can identify and arrest.

Democratic lawmakers have asked ICE to stop using facial recognition in public, arguing (correctly) that the technology's error rate is unacceptable when the consequences include detention and potential deportation. The agency has largely ignored these requests.

What's happening here is particularly revealing about how surveillance technology actually gets used in practice. It's not that there's some careful consideration of whether facial recognition should be used for immigration enforcement. It's that ICE has the capability to do it, so the agency does it. Oversight is minimal. The error rate is acceptable as long as it's not too publicly embarrassing. And the political will to restrict ICE's surveillance capabilities is weak.

Furthermore, Customs and Border Protection has signed a $225,000 contract with Clearview AI, a controversial facial recognition company that scraped billions of photos from social media to build its database. This contract gives Border Patrol intelligence units access to Clearview's technology for identifying people at the border and beyond.

Clearview AI has been the subject of lawsuits and investigations because its business model essentially amounts to mass biometric scraping without consent. The company argues its work is legal because it's using publicly posted photos. But there's a difference between a photo being public on one platform and that photo being incorporated into a government facial recognition database.

The erosion of privacy happens incrementally. One contract at a time. One feature addition at a time. One database integration at a time. Until suddenly, the government has the ability to identify anyone, anywhere, and you didn't even realize it was happening.

Estimated data suggests that public opinion on facial recognition technology is predominantly negative, with 60% expressing concerns, particularly regarding privacy and discrimination.

The Minnesota Immigration Surge: When Enforcement Breaks the Courts

While the nation debated ICE's use of facial recognition, the Trump administration was simultaneously conducting an immigration enforcement surge in Minnesota that revealed something even more troubling: our court system simply cannot handle the volume of cases that mass immigration enforcement generates.

A WIRED analysis of court filings found that petitions seeking release from ICE custody skyrocketed in January. These are habeas corpus petitions—legal documents arguing that people are being illegally detained and should be released. The system was completely overwhelmed.

Here's what happens in practice: someone gets arrested by ICE. Their family files a habeas corpus petition asking a court to review whether the detention is legal. These petitions are supposed to be handled quickly—ideally within days, certainly within weeks. But when ICE is conducting mass enforcement operations, the courts get buried.

US attorneys, the officials responsible for defending the government's position in these cases, found themselves stretched to the breaking point. They literally didn't have enough resources to respond to the petitions. People were left imprisoned far beyond the legal limits because the court system couldn't process the cases.

This is the hidden cost of mass enforcement: it doesn't just affect the people being detained. It gums up the entire judicial system. It prevents other cases from being heard. It creates a backlog that can take months or years to clear.

The Broader Pattern: How Surveillance Normalizes

Looking at all these stories together—Ring killing Flock, Meta planning face recognition, ICE using facial recognition, Iran shutting down the internet—a pattern emerges.

Surveillance doesn't arrive as some obvious dystopia. It arrives as incrementalism. A feature that seems useful, a partnership that seems logical, a technology that seems inevitable. Each individual piece seems justifiable. "We're just trying to help find lost dogs." "We're just trying to identify criminals." "We're just trying to secure the border."

But collectively, these pieces create infrastructure. They create systems. They create a world where dissent becomes risky, where privacy becomes impossible, where the powerful can see everything while the powerless are watched constantly.

The Ring-Flock partnership dying in public is actually the exception. Most surveillance expansion happens quietly. Most partnerships are formed before the public even knows they're possible. Most features get released and then people slowly adapt to their reality.

The question we face in 2025 is whether this is inevitable or whether we actually have the ability to shape what surveillance infrastructure we build.

Understanding Your Digital Footprint in a Surveillance-First World

If all this sounds fatalistic, it doesn't have to be. There are concrete steps you can take to protect your privacy in a world where surveillance capabilities are expanding.

First, understand what data you're creating. Every Ring camera owner should understand that their footage is being created and stored. Every Meta smart glasses wearer should understand that they're recording video. Every person using GPS-enabled devices is leaving a location trail. The data exists whether you think about it or not.

Second, make conscious choices about which platforms you use. You don't have to own a Ring camera. You don't have to wear Meta smart glasses. You don't have to use every app that requests location data. These choices matter, both individually and collectively. If fewer people adopt a surveillance device, that device becomes less valuable to both the company and law enforcement.

Third, stay informed about policy changes. Surveillance laws and practices change constantly. A practice that's currently restricted might become legal under a new administration. A company that currently limits data sharing might be forced to expand it. Staying aware of these changes gives you the information you need to make informed decisions.

Fourth, support privacy advocacy organizations. Groups like the Electronic Frontier Foundation, the American Civil Liberties Union, and countless smaller organizations are fighting for privacy protections. They need support, both financial and political.

Fifth, push back on the false choice between privacy and security. You'll constantly hear arguments that "if you have nothing to hide, you have nothing to fear," or that privacy advocates are opposing necessary security measures. This is a false dichotomy. Privacy and security are not opposites. In fact, strong privacy protections are essential for genuine security. A surveillance state is not a secure state.

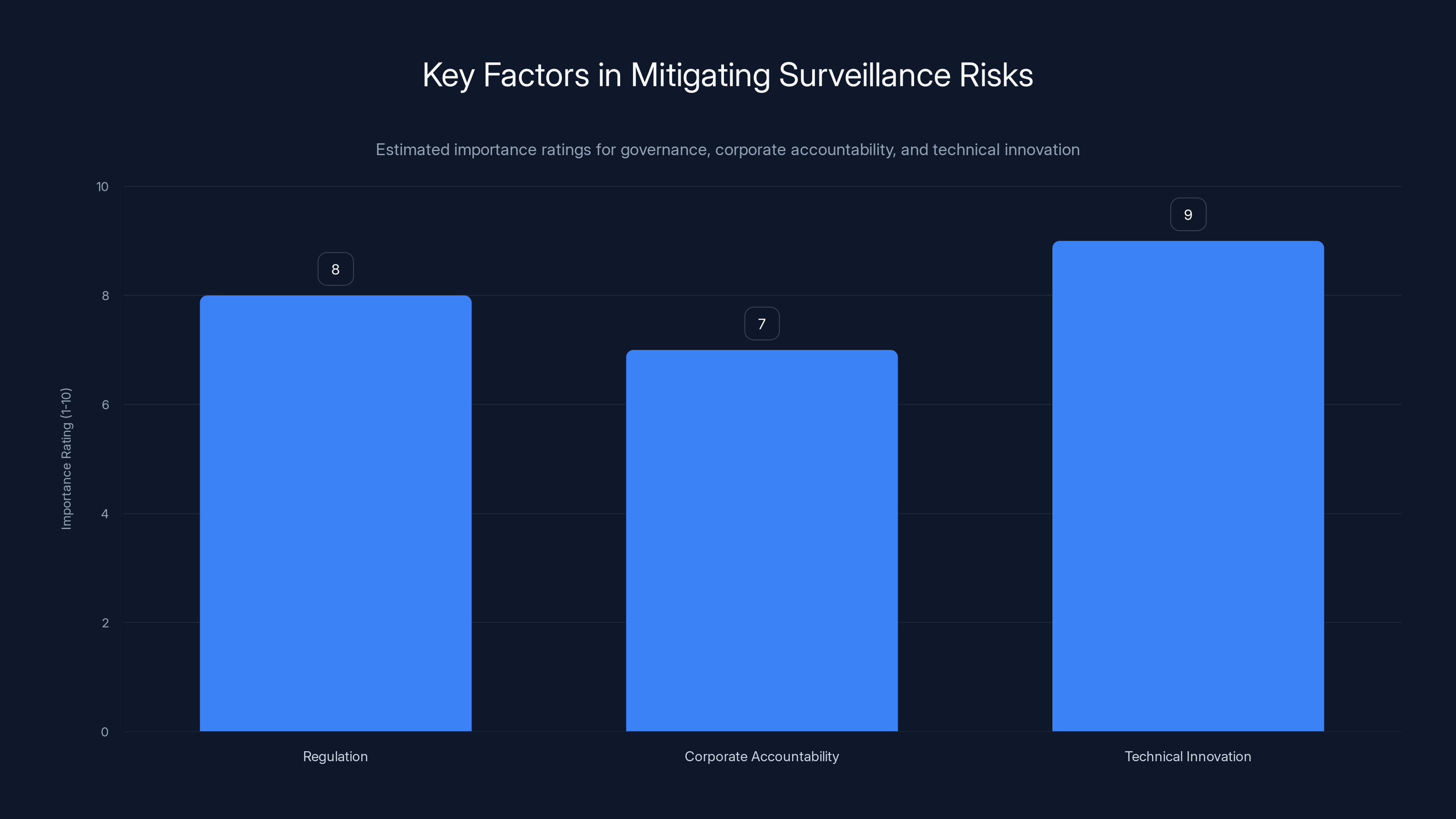

Estimated data suggests that technical innovation is perceived as the most crucial factor in mitigating surveillance risks, followed closely by regulation and corporate accountability.

The Path Forward: Technology, Governance, and Human Agency

We're at an inflection point. The technologies that enable total surveillance are now mature and widespread. The infrastructure is largely in place. The question is not whether surveillance is possible—it obviously is. The question is whether we'll accept it as inevitable or whether we'll choose a different path.

This requires three things simultaneously:

First, better regulation. Governments need to establish clear legal frameworks around surveillance technology. What data can be collected? Who can access it? What oversight exists? How do people get redress if their data is misused? Right now, in most jurisdictions, these questions don't have clear answers.

Second, corporate accountability. Companies like Ring, Meta, and Clearview AI need to face real consequences when they abuse surveillance capabilities. This means both regulatory enforcement and market pressure. People should understand what they're buying and what data they're surrendering.

Third, technical innovation around privacy. The same engineers who build surveillance systems can build privacy-preserving systems. End-to-end encryption, differential privacy, decentralized data storage—these technologies exist. The problem is they're economically disadvantageous for companies built on data collection. We need to change those incentives.

The surveillance stories of 2025 aren't accidents. Ring's Search Party feature wasn't designed with some hidden malicious purpose. Meta's face recognition wasn't created to suppress dissent. But all of these technologies can be and will be used for those purposes unless we build governance structures that prevent it.

The good news is that we actually have more agency than it feels. The Ring-Flock partnership died because of public pressure. That was a moment where the normal march of surveillance expansion was actually interrupted. It's possible. It takes sustained attention and pressure, but it's possible.

The bad news is that the opposite is true too. Every day that surveillance technology exists without clear regulation, without meaningful oversight, without public understanding of how it works, its normalization accelerates. Pretty soon, facial recognition in smart glasses will feel normal. Dragnet license plate surveillance will feel routine. Government access to private security camera networks will seem reasonable.

The choice we face is not between a world with surveillance technology and one without it. That choice has already been made; the technology exists. The choice is whether we'll govern it democratically or let it govern us.

How Automation and Integration Tools Address the Surveillance Problem

While surveillance presents obvious challenges, there's an interesting counterpoint worth considering: how better automation and integration tools can actually increase transparency and reduce surveillance abuse.

When surveillance data is fragmented and difficult to access, it's less likely to be misused at scale. But when fragmentation creates inefficiency, organizations push for better integration—which is exactly what Ring and Flock were attempting.

This is where tools that emphasize transparency in data flow become valuable. Runable, for instance, offers AI-powered automation for creating reports, documents, and presentations that can actually help organizations understand and audit their own data practices.

When a company like Ring needs to document its data sharing policies, understand the implications of new integrations, or create compliance reports, better workflow automation tools can help. They can speed up the process of creating audit trails, documenting what data goes where, and who has access to what.

Runable's capabilities with AI-generated presentations and reports starting at $9/month can help organizations create transparency documentation. When your company needs to prove you're not sharing data inappropriately, when you need to audit your own surveillance practices, when you need to document that you eliminated police access to footage without warrants—better documentation tools help you do that.

Use Case: Creating transparent audit reports on data sharing practices to verify compliance with privacy policies

Try Runable For FreeThe irony is that surveillance expansion often gets stopped not by preventing the technology, but by forcing transparency and documentation. When companies have to clearly document what they're doing and why, when the implications become obvious, public pressure increases.

The Economics of Surveillance: Why It's Expanding

To understand why surveillance keeps expanding despite repeated public outcry, you need to understand the economics.

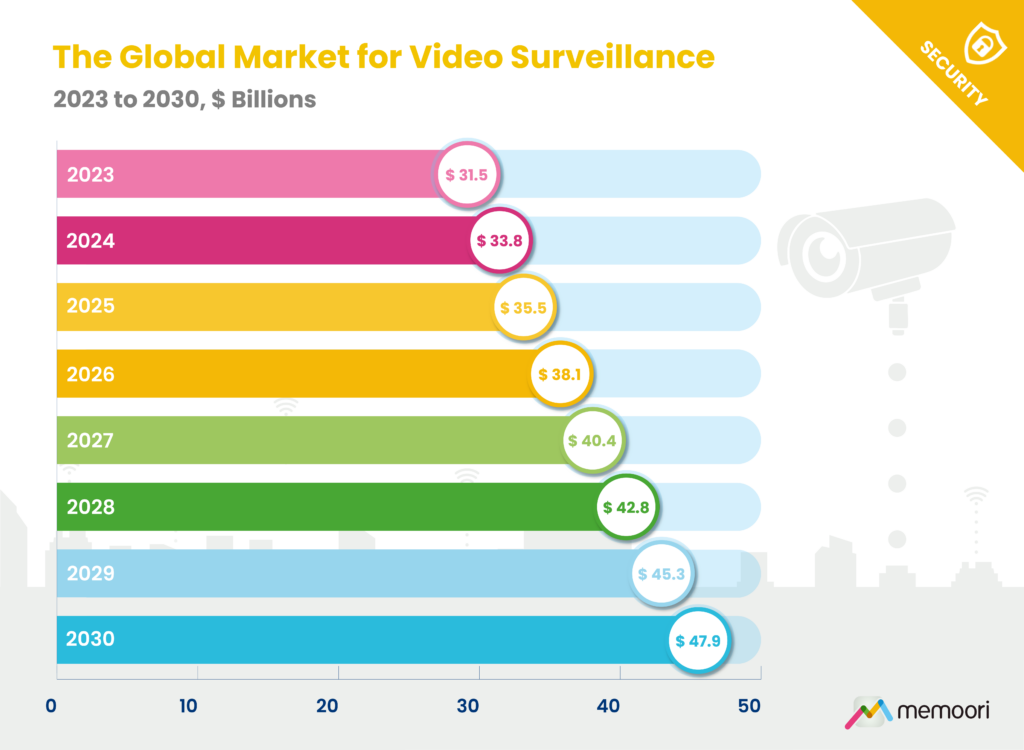

Surveillance is profitable. When you own a network of cameras, that data has value. When you operate license plate readers, law enforcement will pay you for access. When you build facial recognition databases, governments will contract with you. Surveillance is a business, and like all businesses, it expands because it's economically advantageous to do so.

The question of whether surveillance should expand legally is secondary to whether it can expand profitably. As long as there's money in surveillance, companies will pursue it. As long as there's a demand for surveillance capabilities, companies will build them.

This is why regulation matters. Right now, the default is expansion. Surveillance expands unless someone stops it. For it to not expand, you need actual legal restrictions, not just hoping that companies will voluntarily limit themselves.

Ring's cancellation of the Flock partnership is not evidence that the market is self-correcting. It's evidence that sufficient public pressure can temporarily override economic incentives. But that pressure needs to be sustained and widespread. For the vast majority of surveillance expansion, that pressure never materializes.

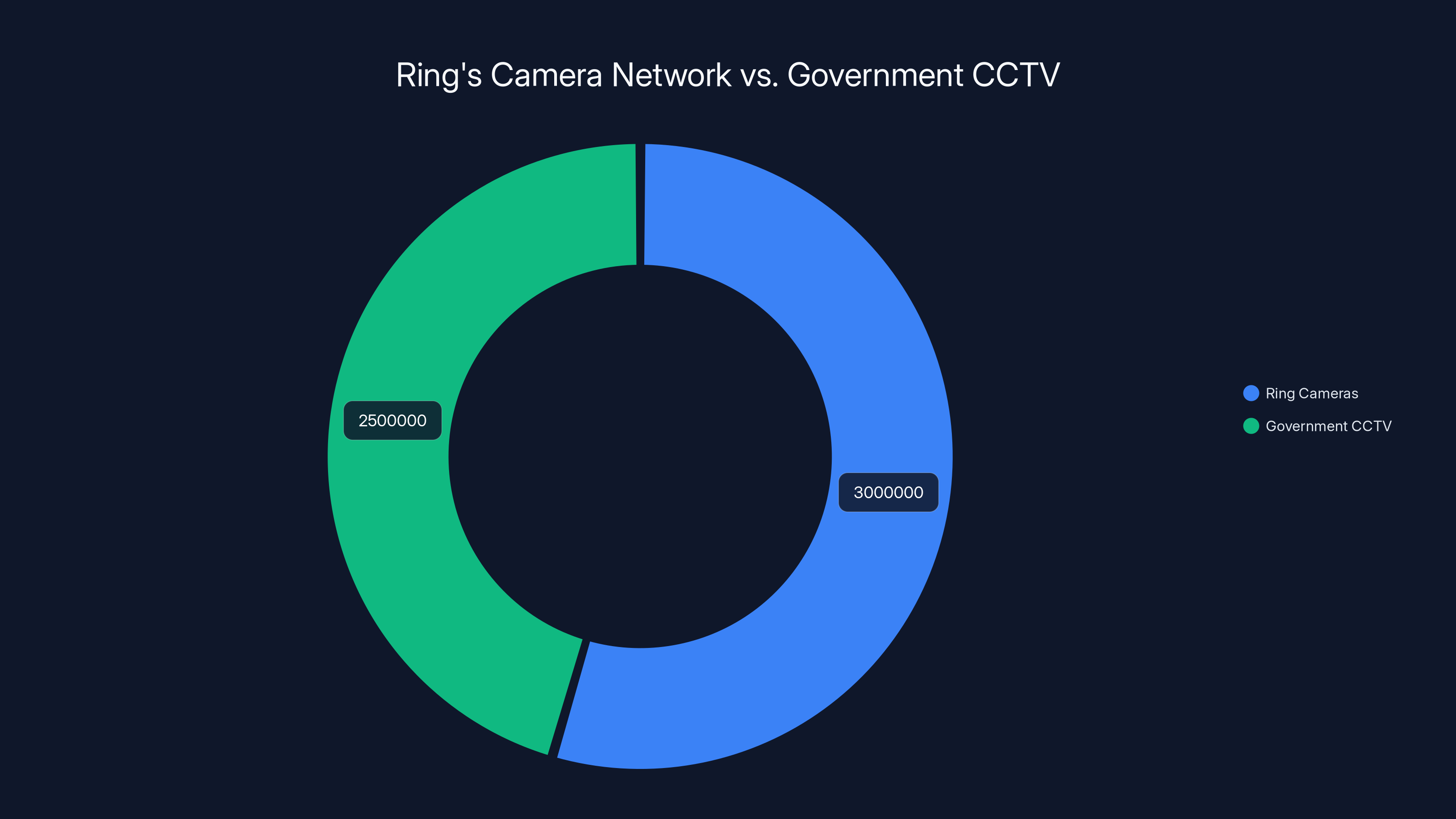

Ring's network of over 3 million cameras surpasses many government CCTV systems, highlighting its extensive reach in private surveillance. Estimated data.

Global Perspectives: How Different Countries Address Surveillance

The United States is not alone in grappling with surveillance challenges. Different countries are taking radically different approaches.

Europe has taken a more restrictive stance with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which gives individuals broad rights to control their data and imposes significant penalties on companies that abuse those rights. The regulation is imperfect, but it's substantially more protective than anything in the US.

China has embraced surveillance as an explicit tool of governance, with camera networks and facial recognition deployed nationwide. Uyghur Muslims in Xinjiang region have experienced particularly pervasive surveillance, with studies documenting the use of surveillance technology as a tool of ethnic suppression.

Russia uses surveillance selectively—heavily in major cities against political dissidents, less so elsewhere. The country has been building an extensive surveillance infrastructure, partly in response to US sanctions and partly as a tool of political control.

India has been rapidly building biometric infrastructure, with Aadhaar, a national ID system that includes iris scans and fingerprints for over a billion people. The system was pitched as a way to improve government services and reduce fraud, but it's become a surveillance tool as well.

These different approaches reveal something important: there's no universal inevitability to how surveillance develops. Countries are making choices about what level of surveillance to accept and what protections to put in place. Some countries chose strong privacy protections; others chose surveillance expansion.

The US is currently trending toward the latter. That's not inevitable. It's a choice.

Emerging Surveillance Technologies on the Horizon

Just when you think surveillance has reached its limits, new technologies emerge that expand the possibilities further.

Emotion detection: AI systems are being trained to detect emotional states from facial expressions, tone of voice, and behavioral patterns. Companies are marketing emotion detection technology to law enforcement, arguing it can identify dangerous individuals. The accuracy is questionable, but the potential for abuse is enormous.

Gait recognition: Computer vision systems can identify people by the way they walk. Unlike facial recognition, which requires a clear view of the face, gait recognition can work from far away and through crowds. Several companies are developing this technology, and China has already deployed it.

Drone surveillance: Flying surveillance drones equipped with cameras can hover over an area and track all movement within it. In US cities, police departments are increasingly deploying these for crowd monitoring. On the border, customs agencies use them for immigration enforcement.

Neural surveillance: Companies are researching how to infer what's happening in someone's brain from their external behavior and biometric signals. This is highly speculative, but the research is active, and the implications would be truly dystopian if successful.

Voice biometrics: Your voice is unique and increasingly can be captured and analyzed at scale. This enables silent speaker identification—knowing who's talking even when you can't see them. It enables emotion detection from voice. It enables authentication based on voice.

Each of these technologies is advancing rapidly. Each one expands the scope of what can be surveilled. And in each case, the trajectory is likely from research prototype to commercial deployment to government adoption.

The Role of Transparency and Journalism in Restraining Surveillance

One of the few effective checks on surveillance expansion is journalism and public disclosure. When the public understands what's happening, when journalists document abuses, when the implications become obvious, pressure increases.

This is exactly what happened with the Ring-Flock partnership. The story might have moved quietly through regulatory and business channels without public knowledge. But when journalism connected the Search Party feature to the larger surveillance implications, public outcry forced a response.

Similarly, the 404 Media investigation revealing ICE's use of Flock Safety's license plate reader network increased scrutiny of the partnership.

The challenge is that surveillance often happens in environments where journalism is difficult. Government agencies classify surveillance programs as national security matters. Private companies treat surveillance infrastructure as proprietary business information. The public has limited visibility into how these systems are actually deployed and used.

This is why supporting independent journalism and investigative reporting is essential. When nobody's paying attention, surveillance expands without constraint. When journalists document what's happening, accountability becomes possible.

Building Privacy-Conscious Alternatives

Another approach to constraining surveillance is building and supporting privacy-conscious alternatives to surveillance-based systems.

For smart home devices, there are companies building cameras and doorbells that store footage locally on encrypted devices, rather than sending it to cloud servers. For GPS tracking, there are phones and services that minimize location data collection. For facial recognition, there are biometric systems that work on-device without sending facial data to cloud servers.

These alternatives typically cost more or offer fewer features than surveillance-heavy equivalents. But they exist, and as privacy awareness increases, they're gaining market share.

The barrier to adoption is often information: people don't know these alternatives exist. They don't understand the implications of the surveillance alternatives they're using. When awareness increases, adoption of privacy-conscious options increases too.

This is where community building and education matter. Every person you tell about privacy-conscious alternatives is a potential adopter. Every community forum or website that documents these options helps people make informed decisions. Every expert who takes time to explain why privacy matters contributes to a culture where privacy is valued.

Policy Solutions: What Actually Works

If you want to stop surveillance expansion, you can't just hope companies will do the right thing and count on public pressure to occasionally slow things down. You need actual policy solutions.

Here are approaches that have shown some effectiveness:

Data minimization requirements: Laws that require organizations to collect only the data they actually need, and delete data when they no longer need it. This reduces the damage when data is misused or breached.

Purpose limitation: Rules that restrict data to specific, legitimate purposes and prohibit repurposing data without consent. This would prevent Ring footage from being integrated with Flock, for example.

Consent requirements: Making it illegal to use personal data without explicit consent. This shifts the burden from "you have to prove we violated your privacy" to "we have to prove you agreed to this."

Transparency obligations: Requiring companies to clearly disclose what data they collect, how they use it, and who they share it with. When implications become obvious, pressure increases.

Algorithmic accountability: For AI systems used in consequential decisions (facial recognition for immigration enforcement, emotion detection for security screening), requirements to validate accuracy, test for bias, and demonstrate that systems actually work before deployment.

Data breach notification: Laws requiring immediate notification to affected individuals when personal data is compromised. This makes breaches costly to companies, incentivizing better security.

Right to deletion: Laws giving individuals the right to request that their data be deleted from databases. This is particularly important for biometric data.

Audit rights: Provisions allowing independent auditors to examine how surveillance systems are deployed and used. This creates accountability.

Europe's GDPR incorporates many of these elements. The US has fragmented protections that vary by state and sector. More comprehensive policy frameworks would significantly constrain surveillance expansion.

FAQ

What exactly did Ring's Search Party feature do?

Search Party is an AI-powered feature that scans Ring camera footage to identify dogs. When you mark a dog as lost in the Ring app, Search Party uses computer vision to search nearby Ring cameras' video feeds for that dog, helping you locate it. The feature is genuinely useful for the intended purpose, but privacy advocates immediately recognized it could be adapted to identify people as well.

Why did the Ring-Flock partnership matter so much?

The partnership would have integrated Ring's camera network (millions of privately owned surveillance cameras) with Flock Safety's license plate reader database. This would have created the ability to cross-reference people's physical movements past homes with their vehicle movements across the broader city. The surveillance implications were enormous because it combined two different types of tracking into one system.

Is Meta's face recognition feature in smart glasses actually coming?

According to internal memos obtained by the New York Times, Meta is actively developing a feature called Name Tag that would add real-time face recognition to Ray-Ban smart glasses. The feature hasn't been released yet, but the company is planning to introduce it, banking on reduced public scrutiny of surveillance issues.

How is ICE using facial recognition exactly?

Immigration and Customs Enforcement uses facial recognition databases built from driver's licenses, mugshots, visa applications, and other government databases to identify immigrants. The agency uses these matches to locate and arrest individuals. The accuracy rate is imperfect, leading to false positives and wrongful detentions, but the practice continues to expand.

What's the difference between surveillance and normal security?

Security systems typically focus on preventing specific harms—theft, unauthorized entry, violent crime. Surveillance systems typically involve continuous monitoring of broad populations. The distinction is important because security can often be achieved with less invasive means. Surveillance often collects far more data than is necessary for security purposes.

Can I protect my privacy from facial recognition?

Technically, facial recognition is difficult to defeat completely, but you can reduce exposure: avoid government databases when possible, be mindful of photos you post publicly (they can be scraped), wear sunglasses and masks in public spaces if you want to reduce facial recognition accuracy, and support privacy legislation that restricts the technology's use. Realistically, protection is limited unless you have policy-level changes.

Why is cryptocurrency popular with criminals?

Cryptocurrency enables cross-border money transfer without traditional banking oversight, offers some technical obfuscation (though the blockchain itself is transparent), and operates in jurisdictions with weak enforcement. For criminals engaged in trafficking or forced labor, these properties are attractive because they enable moving money without detection.

What's the most important thing I can do about surveillance?

Stay informed and support privacy advocacy. Make conscious choices about which devices and services you use. Vote for politicians who support privacy protections. Support journalism that investigates surveillance abuses. Individual choices matter, but systemic change requires political action.

Are there jobs in privacy protection and surveillance resistance?

Yes. Privacy has become a significant area of concern and investment. There are opportunities in privacy consulting, privacy law, security research focused on privacy, and technical roles building privacy-preserving technologies. As awareness of surveillance issues increases, demand for privacy expertise grows.

Why do governments keep expanding surveillance if people hate it?

Because surveillance is useful for governments. It helps enforce laws, identify threats (real or perceived), and suppress dissent. Politicians often use "security" and "law and order" as justifications, even when the surveillance isn't actually necessary for those purposes. And because surveillance expansion often happens quietly, it doesn't generate the political opposition needed to stop it.

The Stakes: Why This Matters Beyond Privacy

There's a tendency to frame surveillance as a privacy issue, as if it's fundamentally about whether you care about your personal data. But that's too narrow. Surveillance is ultimately about power.

When governments and corporations can see everything, when they can track movements, identify individuals, monitor communications, detect emotions—they hold power over those whose activities are being monitored. This power is asymmetrical. The powerful can see the powerless; the powerless cannot see the powerful.

History demonstrates repeatedly that this asymmetry is weaponized. Surveillance is used to suppress dissent, target minorities, enable discrimination, and maintain oppressive systems. It's not incidental; it's fundamental.

This is why Iran shut down the internet during protests. This is why China built surveillance infrastructure in Xinjiang. This is why the US government is eager to use facial recognition for immigration enforcement. Surveillance is a technology of control.

The question of whether we'll accept normalized surveillance infrastructure in democracies is therefore not a technical question or even primarily a privacy question. It's a political question about what kind of society we want to live in.

Do we want a society where everyone can be tracked, identified, and monitored at all times? Where dissent is risky because your movements are recorded? Where minorities can be targeted because surveillance makes discrimination more efficient?

Or do we want a society where privacy is protected, where people have the freedom to move, communicate, and associate without constant monitoring?

This choice is real. It's not predetermined. But it requires sustained attention and political action to preserve privacy in a world where surveillance technology is cheap and powerful.

The Ring-Flock partnership dying was a tiny victory in a much larger struggle. But it was a victory, and it proves that resistance is possible.

Conclusion: Resistance is Possible, But Fragile

The security news of early 2025 reveals a surveillance apparatus that's simultaneously expansive and fragile. Expansive because the technical capabilities are enormous and spreading rapidly. Fragile because it depends on normalization, and when the public suddenly becomes aware of what's possible, the political support evaporates.

Ring killing the Flock partnership, Meta hesitating on smart glasses face recognition, Congress questioning ICE's facial recognition use—these are all moments where the default march of surveillance expansion was temporarily interrupted. These interruptions matter. They prove that the trajectory isn't predetermined.

But they also show how thin the margin is. Ring's cancellation came only after a Super Bowl ad made the implications obvious. Meta's face recognition is still being planned; the hesitation is tactical, not principled. ICE continues expanding biometric surveillance despite congressional criticism.

The challenge ahead is maintaining attention and pressure on these issues. Surveillance expands when people aren't paying attention. It contracts when they are. This means the work is never finished. Every day requires staying informed, making conscious choices, and supporting those fighting for privacy protections.

The good news is that this isn't a hopeless fight. The Ring-Flock story proves it. Technology doesn't have a destiny. We choose what technology becomes, what it's used for, and what limits we place on it. Right now, that choice is up for grabs.

Make it wisely.

Key Takeaways

- The line between helpful innovation and dystopian surveillance has become impossibly blurry

- Png)

*Automation tools like Runable can significantly enhance transparency and control over data access, with high effectiveness in creating audit trails and improving overall efficiency

- " Translation: We're stopping this because the public relations nightmare isn't worth it

- But here's the critical thing to understand: this isn't really about Ring or Flock making an ethical choice

- It's about Ring, owned by Amazon, calculating that maintaining customer trust is more valuable than the short-term benefits of the partnership

Related Articles

- DJI Romo Security Flaw: How 7,000 Robot Vacuums Were Exposed [2025]

- Tenga Data Breach: What Happened and What Customers Need to Know [2026]

- WPvivid Plugin Security Flaw: Nearly 1M WordPress Sites at Risk [2025]

- Testing OpenClaw Safely: A Sandbox Approach [2025]

- Fake Chrome AI Extensions: How 300K+ Users Got Compromised [2025]

- iRobot's Chinese Acquisition: How Roomba Data Stays in the US [2025]

![Cybersecurity & Surveillance Threats in 2025 [Complete Guide]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/cybersecurity-surveillance-threats-in-2025-complete-guide/image-1-1771070802037.jpg)