NASA Crew-12 Mission to ISS: Everything About February 11 Launch [2025]

It's not every day that NASA adjusts a space mission launch date by four days. But that's exactly what happened with Crew-12. Originally scheduled for February 15, the mission got moved up to February 11, and for good reason—the International Space Station needed reinforcements sooner rather than later. According to NASA's official announcement, this adjustment was crucial to maintain the station's operations.

Here's what you need to know: four astronauts are about to blast off from Florida's Cape Canaveral Space Force Station aboard a SpaceX Dragon capsule. They're heading to an orbiting laboratory where just three people are currently holding down the fort. The situation wasn't always this understaffed. Crew-11's mission ended earlier than planned because of a medical concern with one of the crew members. NASA made the conservative call to bring everyone home on January 15, more than a month ahead of schedule.

This creates an interesting moment in human spaceflight. The ISS is still operating, still conducting experiments, still being maintained. But with fewer hands on deck, every day without additional crew members means longer work hours for those already up there. Crew-12 is the relief crew everyone's been waiting for.

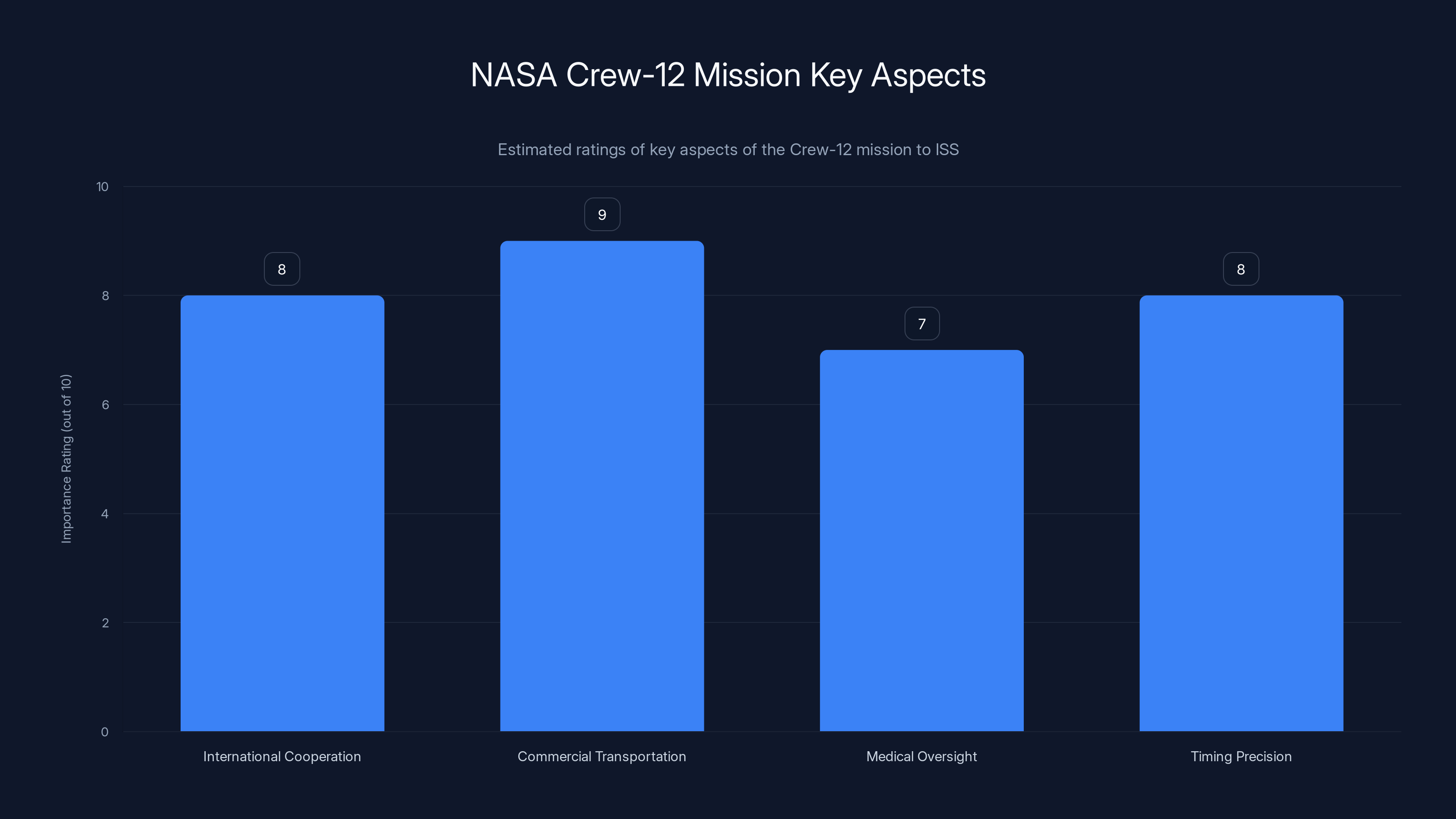

The mission represents everything modern crewed spaceflight has become: international cooperation, commercial transportation, careful medical oversight, and split-second timing. SpaceX's involvement makes this possible. The company has moved from startup status to NASA's primary contractor for crew rotations. That's a remarkable transformation in just over a decade.

But there's more to this story than just a simple crew swap. This mission tells you something important about how space operations actually work—the contingencies, the safety protocols, the international partnerships, and the technical challenges that rarely make headlines.

TL; DR

- Launch Date & Time: February 11, 2025, no earlier than 6:01 AM Eastern from Cape Canaveral

- Crew Members: NASA astronauts Jessica Meir and Jack Hathaway, ESA astronaut Sophie Adenot, and Roscosmos cosmonaut Andrey Fedyaev

- Docking Time: Dragon capsule expected to dock with ISS at approximately 10:30 AM Eastern on February 12

- Why Moved Up: Crew-11 mission ended early due to medical concern; ISS currently has only three crew members

- SpaceX Role: NASA's partner for crew transport; Falcon 9 rocket recently cleared for flight after upper stage inspection

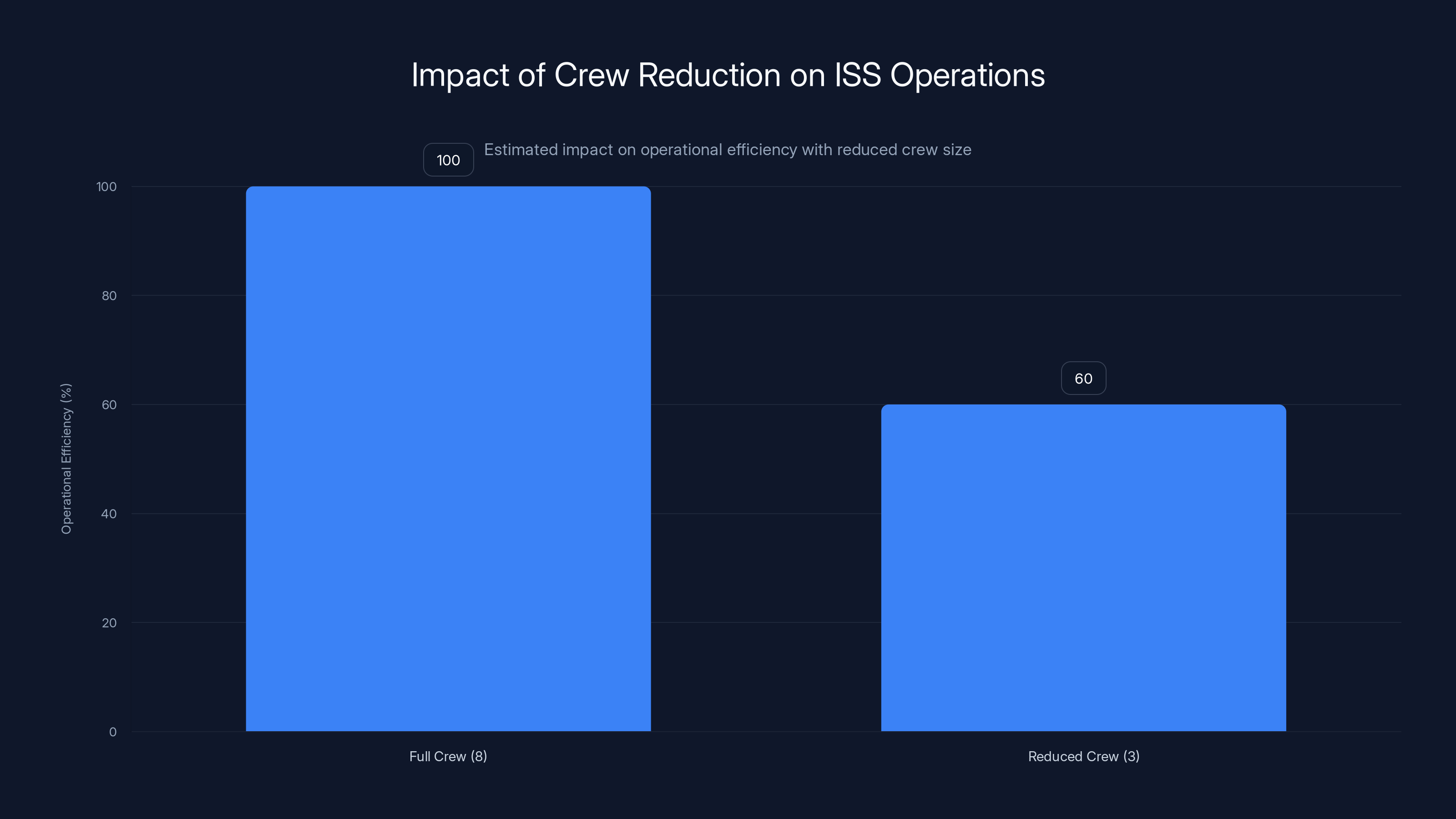

Estimated data: Reducing the ISS crew from 8 to 3 members decreased operational efficiency by approximately 40%, impacting maintenance and scientific output.

Understanding the Crew-12 Mission Context

Crew rotations at the ISS aren't random events. They're choreographed operations involving dozens of organizations, thousands of people, and months of preparation. Crew-12 is no exception, but its accelerated timeline makes it particularly interesting to examine.

The mission sits at the intersection of human spaceflight's past and future. The past involves Russian participation—Roscosmos cosmonaut Andrey Fedyaev is part of the crew. Despite geopolitical tensions on Earth, space agencies continue working together on the ISS. This partnership, established in the 1990s after the Cold War, represents one of humanity's most ambitious diplomatic achievements.

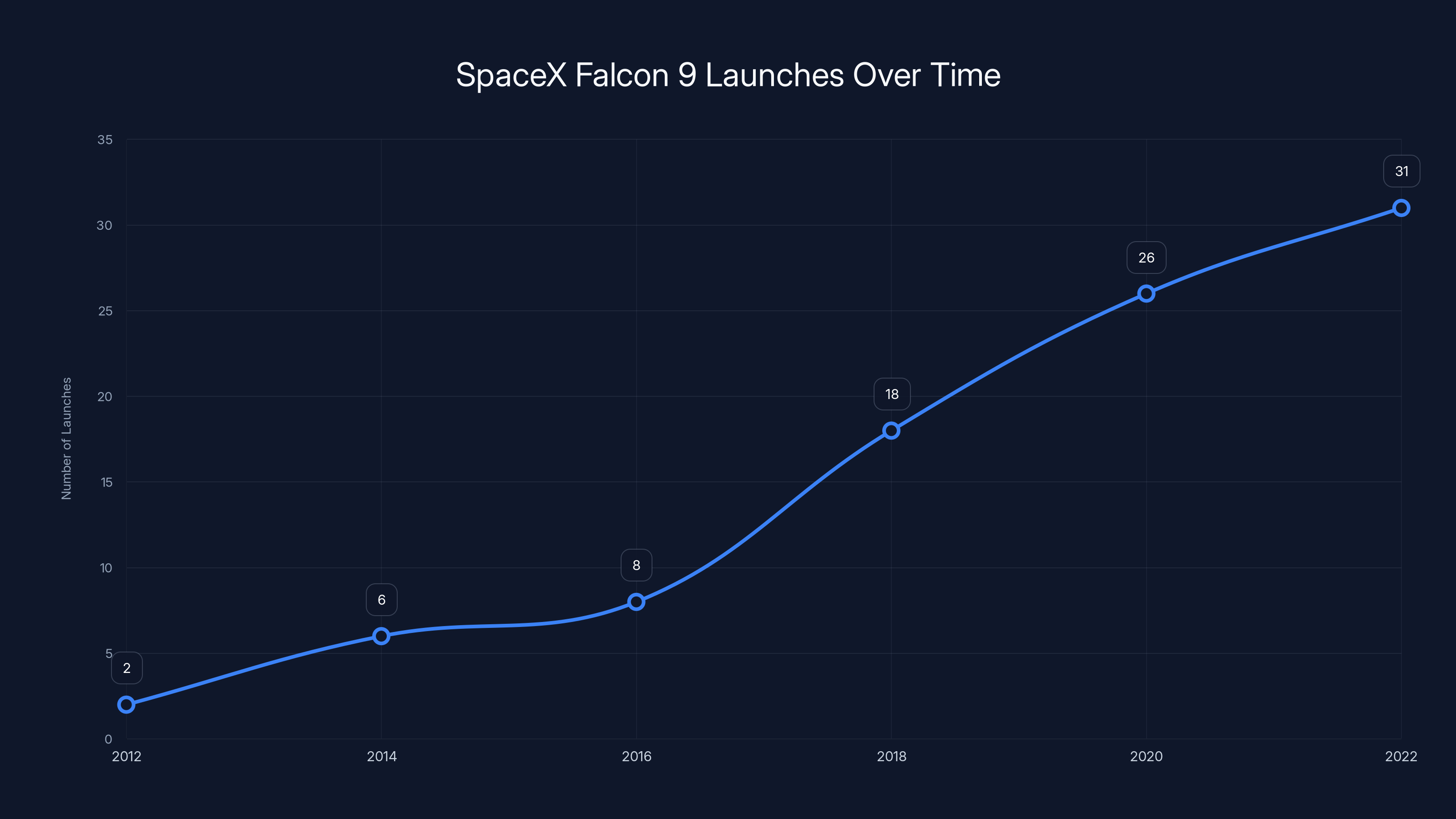

The future involves commercial spaceflight. SpaceX didn't exist as a company when the ISS was being constructed. Now the company is essential to the station's operation. Every crew rotation depends on Falcon 9 rockets and Dragon capsules. This commercial-government partnership has fundamentally changed how humanity accesses space.

Crew-12 also demonstrates NASA's commitment to safety over schedule. When one Crew-11 member experienced a medical concern, NASA didn't hesitate to bring everyone home early. Some space agencies might have pushed forward. NASA chose the conservative path. That's a cultural choice that matters—it signals that human wellbeing outweighs launch schedules.

The four-day acceleration from February 15 to February 11 shows something else: flexibility in a complex system. Moving a space launch isn't like rescheduling a dentist appointment. It requires checking weather forecasts, fuel readiness, ground crew scheduling, international coordination, and dozens of other variables. NASA and SpaceX did all that analysis and decided February 11 was better. That's operational maturity.

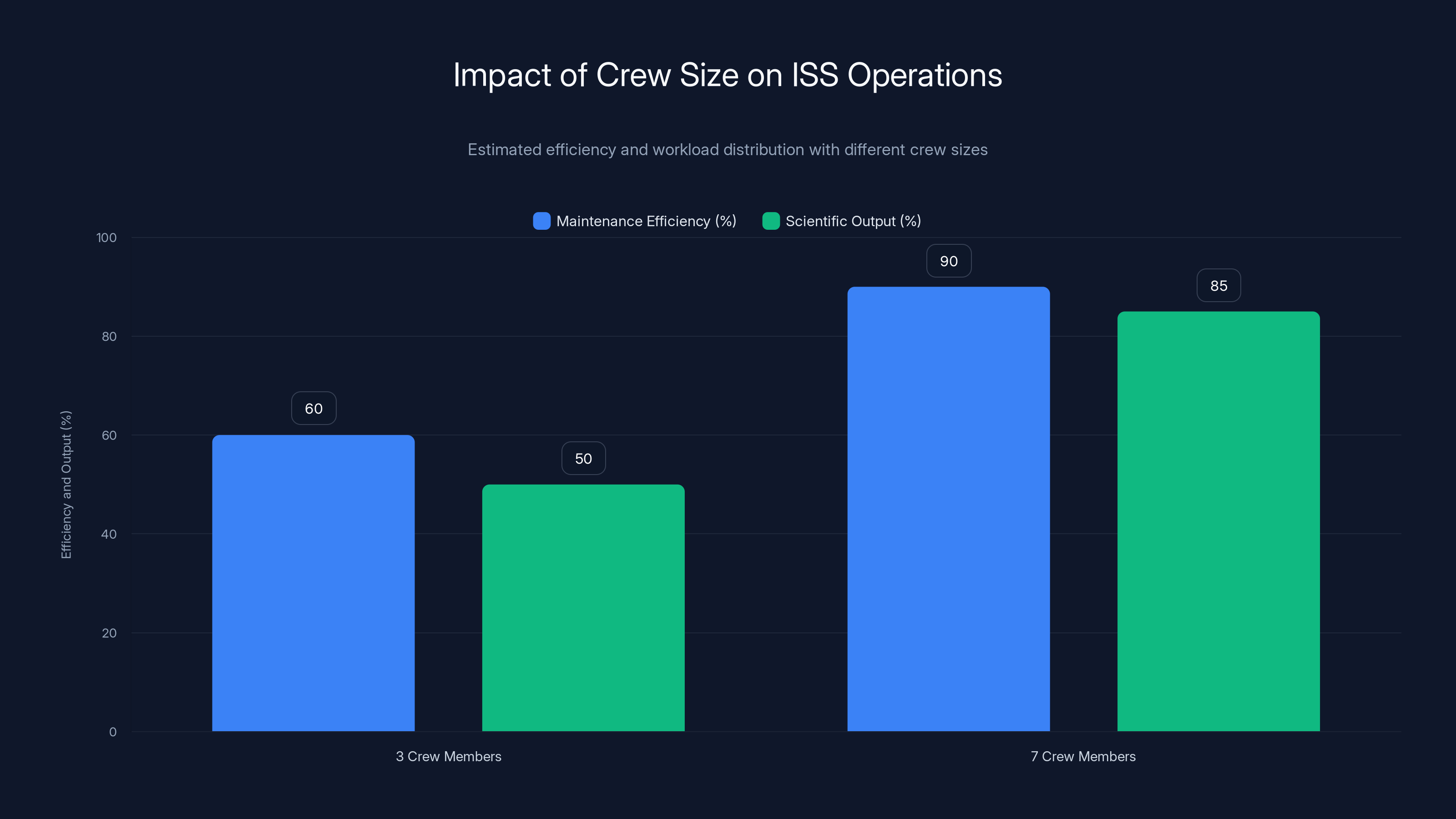

Estimated data shows that increasing the crew size from 3 to 7 significantly boosts maintenance efficiency and scientific output on the ISS.

The Crew Members: Who's Going to the ISS

Let's talk about the people actually making this journey. Four individuals are about to spend months orbiting Earth at 17,500 miles per hour. Understanding who they are adds humanity to the technical mission details.

Jessica Meir is a NASA astronaut with serious credentials. She's a marine biologist by training, which might seem odd for space exploration until you realize how much oceanography and space science overlap. Both involve extreme environments, remote sensing, and sample collection. Meir has already spent time on the ISS during previous missions. This isn't her first rodeo in orbit.

Jack Hathaway represents the newer generation of NASA astronauts. He's an engineer who joined the astronaut corps more recently. His background includes work in challenging technical environments. Unlike Meir, this will be his first time in space. That's actually typical—space agencies rotate experienced and first-time astronauts to balance expertise with fresh perspective.

Sophie Adenot brings European Space Agency expertise. She's trained extensively at multiple space agencies, understanding different approaches to spacecraft operation and experiment management. ESA's participation in crew rotations reflects the ISS's truly international character. No single nation owns or operates the station. It's a shared resource.

Andrey Fedyaev is the Roscosmos cosmonaut. His presence emphasizes that despite everything happening in the news, space agencies maintain operational partnerships. The ISS remains one of humanity's few genuinely collaborative achievements. The station orbits above all borders, operated jointly by agencies from multiple countries.

Together, these four people represent the diversity of modern spaceflight. Two Americans, one European, one Russian. Backgrounds in biology, engineering, and cosmonaut training. Some with ISS experience, some without. This balance is intentional—space agencies believe mixed crews with varying backgrounds perform better.

The crew has already entered quarantine as of the announcement. That's standard procedure. Space agencies want to minimize any possibility of illness during the mission. If someone develops flu symptoms, that could delay the launch. Quarantine prevents those situations.

Why Crew-11 Came Home Early: The Medical Concern

The ISS had eight crew members normal. It was operating at full capacity. Then in January, NASA made an unusual announcement: Crew-11 would return home on January 15, a full month earlier than planned. The reason was a medical concern with one crew member.

NASA didn't provide specific details about what the medical concern was. That's standard practice—space agencies protect astronaut medical privacy. What they did say was important: the affected crew member was stable, and returning them to Earth was the appropriate medical response.

Here's the crucial detail: the ISS didn't have the diagnostic equipment necessary to properly evaluate the condition. Space stations have medical capabilities, but they're limited. You can't do every test or procedure in microgravity that you can do on the ground. For conditions requiring proper diagnosis and treatment, Earth is the only option.

This decision highlights something about spaceflight that often gets overlooked. Space is dangerous. Not just during launch and landing, but during long-duration missions too. Astronauts face radiation exposure, bone density loss, fluid shifts, vision problems, and other physiological changes. A medical concern that develops in space requires real medical infrastructure to evaluate properly.

Bringing Crew-11 home early meant the ISS suddenly operated with fewer people. All eight crew members went home. That left the station in the hands of Chris Williams and two Russian cosmonauts—just three people to maintain a football-field-sized facility packed with experiments, life support systems, and equipment.

Three people can keep the ISS running. It's been done before. But it's inefficient. Daily maintenance takes longer. Experiment work slows down. Scientific output decreases. From a mission efficiency standpoint, having only three people is like running a research hospital with one doctor and two nurses.

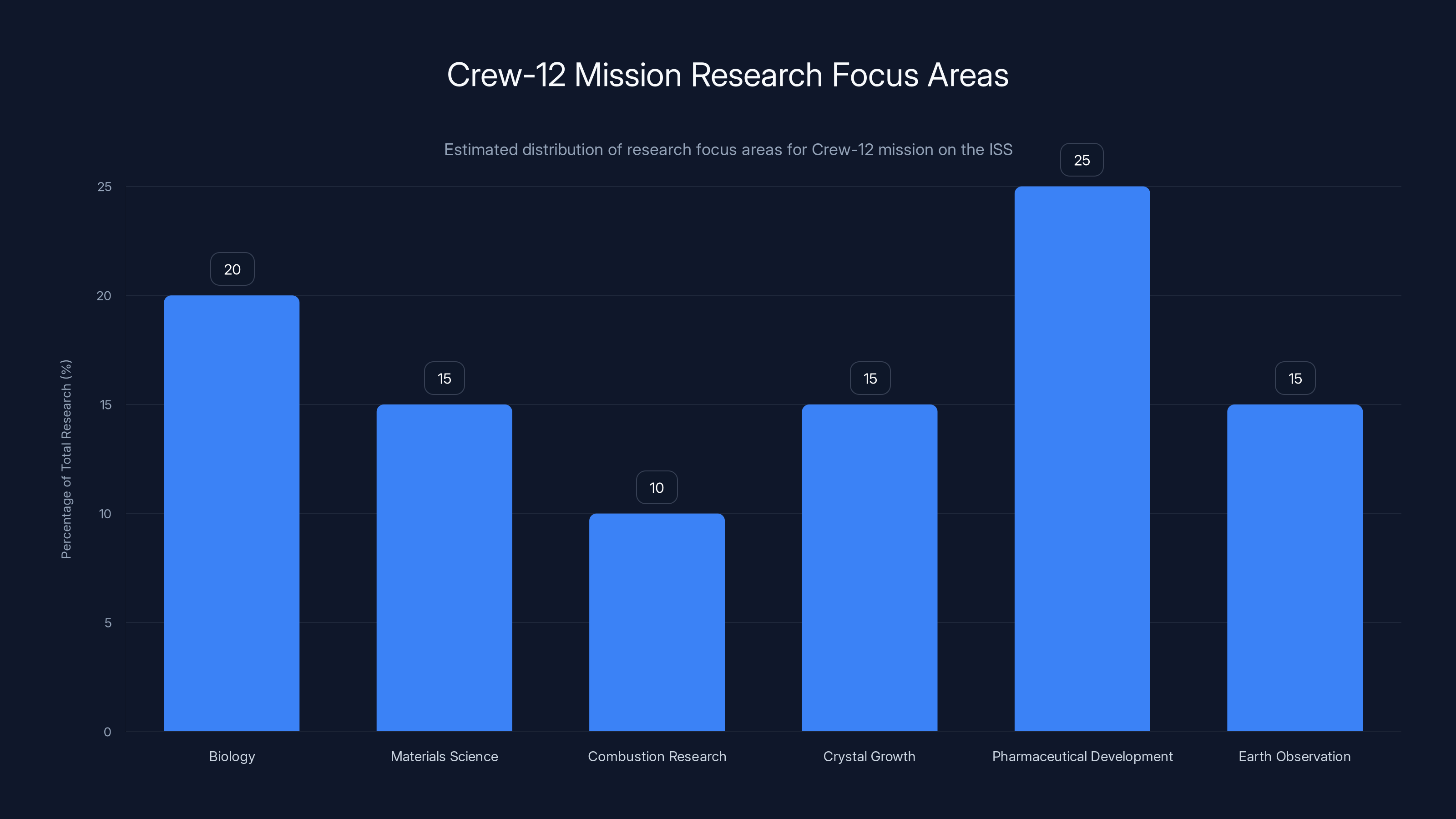

The Crew-12 mission will focus on a diverse range of scientific investigations, with pharmaceutical development and biology being primary areas of research. Estimated data.

The SpaceX Dragon and Falcon 9: Getting There

Crew-12 won't be traveling via Russian Soyuz spacecraft. Instead, they'll fly aboard SpaceX's Dragon capsule, launched atop a Falcon 9 rocket. This commercial approach to crew transportation would have seemed like science fiction two decades ago.

SpaceX has been launching cargo to the ISS since 2012. The company has proven itself with hundreds of successful flights. But crew transportation is different. It's the most scrutinized, safety-critical work SpaceX does. NASA doesn't hand over astronaut lives lightly.

The Falcon 9 rocket has evolved considerably since its early flights. The first stage boosters land themselves, returning to Earth and being reflown. This dramatically reduces launch costs compared to traditional expendable rockets. SpaceX has launched the same booster dozens of times. The reliability is there.

For Crew-12, SpaceX recently had to ground the Falcon 9 temporarily due to an issue with the rocket's upper stage. The Federal Aviation Administration halted flights until the issue was investigated and resolved. On February 6, the FAA cleared the rocket for flight again. The specific technical issue wasn't publicly detailed, but the point is important: safety protocols work. When something suspicious appears, operations halt until everyone confirms it's safe.

The Dragon capsule itself is a marvel of engineering. It carries the crew of four, supplies, and experiment equipment to the ISS. The capsule is reusable—the same Dragon that carried Crew-12 might be used for Crew-13 or other missions down the road. This reusability is central to SpaceX's economic model and to NASA's long-term ISS strategy.

Once Crew-12 launches at 6:01 AM Eastern on February 11, the Dragon will follow a carefully choreographed trajectory. The rocket will achieve orbit, separate from the upper stage, and the Dragon will coast toward the ISS. Docking is scheduled for approximately 10:30 AM Eastern on February 12.

That 28-hour journey isn't accidental. The exact phasing and timing of orbital transfers follow precise mathematical calculations. SpaceX and NASA have rehearsed this sequence countless times in simulators. When launch day arrives, the actual sequence will feel almost routine to the astronauts—even though they're traveling at 17,500 miles per hour through the vacuum of space.

Launch Timeline and Key Events

Launch days follow precise schedules. Every minute is planned. Every second counts. Here's how Crew-12's launch day will unfold.

T-Minus Four Hours (2:01 AM Eastern): NASA coverage begins on NASA+, Amazon Prime, and YouTube. Coverage includes expert analysis, mission specialists explaining what's happening, and live views of the rocket and launch pad.

T-Minus Two Hours: Final weather briefing. The launch director meets with weather officers to review current conditions and forecasts. If there's any chance of violating launch criteria, NASA will delay.

T-Minus One Hour: Crew members arrive at the launch pad. They board the Dragon capsule, perform final system checks, and get comfortable in their seats. The interior of Dragon is compact—there's not much extra space.

T-Minus Thirty Minutes: Final holds for any last-minute issues. Ground crews perform final checks. Everything must show green before proceeding.

T-00:00 (6:01 AM Eastern, February 11): Ignition. Falcon 9's nine Merlin engines on the first stage ignite. The rocket accelerates upward, climbing through the atmosphere.

T+Plus 8 Minutes: First stage separation. The main engines shut down, and the Dragon separates from the first stage. The booster performs a controlled descent back to Earth, landing on a droneship in the Atlantic Ocean.

T+Plus 11 Minutes: Upper stage engine cutoff. The second stage completes the push to orbital velocity. Dragon is now in space, coasting toward the ISS.

T+28 Hours (approximately 10:30 AM Eastern, February 12): Dragon docking with the ISS. The capsule approaches the station gradually, with crew members inside monitoring systems and ground control providing guidance.

Once docked, the hatches open, and the Crew-12 members float into the station. The station now has seven crew members instead of three. Work pace accelerates. Scientific output increases. The ISS returns to full operational capacity.

The number of Falcon 9 launches has increased significantly since 2012, highlighting SpaceX's growing role in space transportation. Estimated data.

International Space Station: Operating Understaffed

The ISS orbits Earth every 90 minutes. It's never stationary. It's never dormant. Even with three crew members, the station requires constant attention.

Let's break down what three people do on a facility this complex. Chris Williams, the NASA astronaut who remained with the station, is responsible for overseeing American systems, equipment, and experiments. The two Russian cosmonauts manage Roscosmos systems. Together, they keep everything running.

Basic maintenance dominates their time. The ISS has thousands of systems that can fail. Water recycling systems need monitoring. Oxygen generation systems need checking. Thermal control systems need adjustment. Equipment on the exterior requires scheduled maintenance. Treadmills need fixing. Computers need updating.

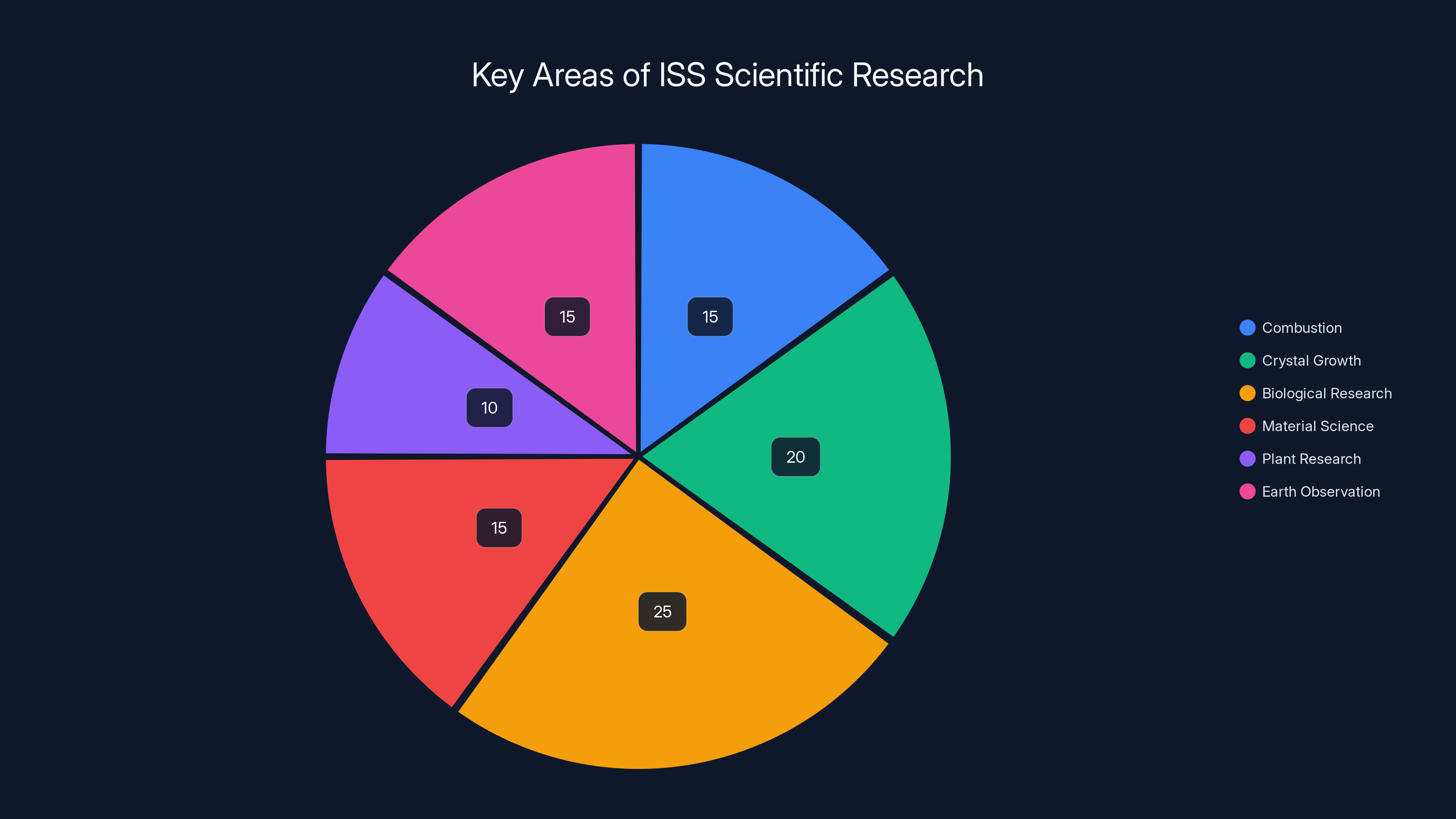

Then there's the science. The ISS is fundamentally a research facility. Experiments in microgravity produce data impossible to obtain on Earth. Crystal growth, combustion dynamics, biological research, materials science, pharmaceutical development—all of it depends on uninterrupted operation.

With eight people, this work distributes across the crew. Each person specializes in certain areas. With three people, specialists have to operate outside their usual domains. Efficiency drops. Frustration increases. But the work continues.

Crew-12's arrival changes everything. Seven people means more hands for maintenance. It means specialists can return to their areas of expertise. It means experiments get proper attention. Scientific output increases. The station returns to optimal operation.

This understaffing situation, while manageable, demonstrates why crew rotations are so critical. The ISS isn't a static facility that can operate indefinitely with reduced staff. It's a living, breathing laboratory that requires human attention and expertise to function properly.

The ISS Crew Composition and International Partnership

Once Crew-12 docks, the ISS crew composition becomes truly international. You'll have American astronauts, Russian cosmonauts, and European space agency personnel all working together 250 miles above Earth.

This international makeup isn't accidental. It's the result of deliberate policy. After the Cold War ended, space agencies decided that orbital collaboration was safer than competition. The ISS represents this principle physically—Americans and Russians, former adversaries, orbiting together.

The crew structure reflects this partnership. NASA manages some modules. Roscosmos manages others. Both agencies have equal say in station operations. Experiments come from multiple countries. Research benefits flow to all participating nations.

Crew members receive cross-training in each other's systems. An American astronaut might need to operate Russian life support equipment. A Russian cosmonaut might need to conduct an American experiment. This cross-training ensures continuity if one space agency has problems launching replacement crew.

Language is standardized—Russian and English are both used, depending on the system being operated. When conducting American experiments, English dominates. When working on Russian systems, Russian takes priority. Astronauts become fluent in both languages and in the specific terminology of space operations.

This multinational, multicultural approach to spaceflight is actually quite unusual. Most human endeavors segregate along national lines. The ISS shows that in space, international cooperation isn't just idealistic—it's operationally superior. More perspectives, more expertise, more problem-solving approaches.

Biological research and crystal growth are major focus areas on the ISS, benefiting from unique microgravity conditions. Estimated data.

Medical Screening and Quarantine Protocols

Before any astronaut gets near a launch pad, they undergo intensive medical screening. Crew-12 members have been evaluated by teams of physicians for months before launch.

These aren't standard annual physicals. Space medicine is specialized. Physicians need to understand how the human body responds to launch G-forces, zero gravity, and the vacuum environment. They evaluate cardiovascular fitness, bone density, radiation tolerance, and psychological readiness.

As launch approaches, medical screening intensifies. Crew members undergo daily health checks. Any sign of illness triggers additional testing. If they have a common cold? They might be grounded. Space agencies cannot risk having an astronaut sick during launch or orbital operations.

Quarantine is implemented starting several days before launch. Crew members isolate from the public. They interact only with other crew members and essential personnel. This minimizes exposure to pathogens. The goal is simple: get four healthy people into space.

The quarantine protocol sounds harsh, but it's necessary. Space missions cost hundreds of millions of dollars and years of planning. Delaying a launch due to illness is enormously disruptive. By quarantining, space agencies prevent that disruption.

Once in orbit, astronauts don't have access to comprehensive medical facilities. They can perform basic first aid. They can manage minor conditions. But serious illness requires returning to Earth. That's why prevention—through quarantine and health monitoring—matters so much.

Medical expertise doesn't end at launch. NASA has spaceflight medical personnel monitoring crew members throughout the mission. They analyze how each person adapts to microgravity. They monitor vital signs. They provide guidance for any health concerns that arise. Space medicine is continuous, not just pre-launch.

Launch Weather and Environmental Factors

February in Florida brings weather variability. Rain, storms, and wind can delay launches. NASA has strict criteria for launch conditions.

The primary weather concerns are wind speeds, lightning potential, and visibility. The Falcon 9 is a tall rocket—about 230 feet from base to Dragon capsule. Wind loads matter. If wind speed exceeds certain thresholds, the rocket becomes unstable during initial ascent.

Lightning is deadly to rockets. The ascent trajectory takes the rocket through the lower atmosphere where lightning typically forms. A lightning strike can disable guidance systems, fuel pumps, or engine controllers. NASA waits for clear conditions with minimal thunderstorm potential.

Visibility matters for cameras and external monitoring. If rain or fog obscures the launch pad, mission controllers can't see the rocket visually. In modern spaceflight, most operations are computer-controlled, but humans monitor visually as a backup.

The launch window for February 11 opens at 6:01 AM Eastern. But that's not a fixed time—it's the earliest possible liftoff. If weather doesn't cooperate, the launch window extends several hours. SpaceX and NASA can launch anytime within that window when weather conditions permit.

Historically, weather causes about half of launch delays. Sometimes it takes multiple days to find conditions that meet all criteria. Crew members wait in their launch suits, mentally preparing, knowing another delay happened due to factors completely outside their control.

This is space exploration—sometimes you get weather. Sometimes you wait. The caution matters. Launching in marginal conditions has never improved a mission. Waiting for good conditions always does.

The Crew-12 mission highlights key aspects of modern spaceflight, with commercial transportation and international cooperation rated highly. (Estimated data)

The Technical Innovation Behind Modern Crew Transport

Crew-12 traveling aboard Dragon represents technological achievement that would have amazed space pioneers. The Dragon capsule combines lessons from decades of spaceflight with cutting-edge automation.

Docking with the ISS used to be incredibly complex. Human pilots manually maneuvered the spacecraft into position, using visual references and intuition developed through extensive training. Modern Dragon performs most docking automatically using sensors, GPS, and guidance computers.

The human crew monitors this process but doesn't control it unless something goes wrong. This automation reduces crew workload during critical operations. It also increases reliability—computers don't get distracted or tired during the complex approach sequence.

Inside Dragon, life support systems keep the crew alive during the journey. These systems are redundant—if one fails, another takes over. Oxygen generation, carbon dioxide scrubbing, pressure regulation, temperature control—all of these operate automatically, maintaining a shirt-sleeve environment for the crew.

Dragon's heat shield uses ablative material—specially designed compounds that burn away controllably during reentry, dissipating heat and protecting the capsule and crew from the extreme temperatures of atmospheric reentry. This technology traces back to Mercury-era spacecraft, but it's been continuously improved.

The spacecraft communicates with ground control through multiple channels. Voice, telemetry data, video feeds—everything travels through ground stations around the world. If one ground station loses signal, another picks up seamlessly.

This level of redundancy and automation wasn't available in earlier spaceflight eras. The Mercury capsules were essentially capsules—limited automation, extensive manual control. The Shuttle was more capable but more complex. Dragon represents a different approach: effective automation, manual override capability, extensive redundancy.

Cargo and Supplies: What Goes Up With Crew

Crew-12 isn't traveling alone. Dragon carries cargo—supplies, equipment, experiments, and consumables needed on the ISS.

For a crewed Dragon flight, the cargo capacity is limited compared to cargo-only flights. Crew members take up volume that could otherwise carry supplies. But some critical items come up with the crew.

These include fresh food, replacement equipment parts, experiment hardware, and scientific instruments. The ISS has storage space, but supplies run low when crew rotations happen. New crew members bring what the station needs most urgently.

Experiments scheduled for the Crew-12 mission were designed months ago. Scientists submitted proposals, went through peer review, and received approval to conduct their work on the ISS. Some experiments are short-duration—completed within days. Others continue throughout the crew's six-month stay.

Cargo manifest details are publicly available. NASA publishes information about what flies on each mission. If you're curious about specific experiments or equipment, you can find that information through NASA's mission websites.

When Dragon undocks to return to Earth at the end of the mission, it carries different cargo—experiment results, completed hardware, research samples. This material is protected during reentry and retrieved shortly after splashdown in the Atlantic Ocean.

The cargo exchange—bringing up supplies, bringing down results—is a critical part of the ISS operation. Without this regular cycling of supplies and research samples, the station couldn't function effectively.

The Return Journey: What Happens at Mission's End

Crew-12 will spend approximately six months on the ISS. This is standard for contemporary crew rotations. Not too short to be inefficient, not too long to cause excessive physiological strain.

At mission's end, Crew-12 will board the Dragon capsule for the journey home. The return is more dramatic than the journey to orbit. Dragon has to survive reentry—the extreme heat and G-forces of plunging back through the atmosphere.

The reentry sequence is automated but monitored closely by Mission Control. The capsule orients itself to maximize heat shield protection. Temperature on the heat shield reaches 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit. Inside, the crew cabin stays pressurized and cool.

Parachutes deploy at lower altitude, slowing the capsule from 150 miles per hour to about 20 miles per hour—still a significant impact, but survivable. The capsule splashes down in the Atlantic Ocean, where recovery ships wait to retrieve it.

The crew emerges after months in microgravity. Their muscles have atrophied. Their bones have lost calcium. Their balance systems have adapted to zero gravity. But they're home. They're safe. They can begin rehabilitation.

Post-mission medical monitoring continues for weeks. Researchers study how the crew adapted to spaceflight and how they readapt to Earth gravity. This data informs our understanding of human physiology and helps design better countermeasures for future long-duration spaceflight.

ISS Scientific Research: Why This Mission Matters

Crew-12's primary role isn't just station maintenance. It's conducting the scientific research that justifies the ISS's continued operation and expense.

With full crew capacity, the ISS can conduct experiments impossible to replicate on Earth. Combustion in microgravity behaves differently than on the ground—fire burns spherically instead of upward. This research improves furnace design and understanding of fuel properties.

Crystal growth experiments benefit from microgravity. Gravity-driven settling normally disrupts crystal formation. In microgravity, crystals grow more perfectly. This research produces better semiconductors and other crystalline materials.

Biological research thrives in microgravity. Proteins organize themselves differently without gravity's influence. Cells organize into patterns impossible on Earth. This research advances our understanding of fundamental biology and leads to better pharmaceuticals.

Material science benefits from conditions possible only in space. Certain alloys and composites develop superior properties when processed in microgravity. These materials find applications in aerospace and other demanding industries.

Plant research on the ISS examines how vegetation grows without gravity. Future lunar bases and deep space missions will need to grow food. Research on the ISS provides critical data for that challenge.

Earth observation is another major ISS mission. The station carries instruments that monitor Earth's climate, land use, and ocean health. This data guides climate science and environmental management.

All of this research requires human presence. Experiments need to be set up, monitored, adjusted, and taken down. Samples need to be managed. Equipment needs maintenance. A full crew of seven makes this possible. A reduced crew of three makes it extremely difficult.

Crew-12's arrival restores the ISS to full scientific productivity. That's not just about crew rotation—it's about humanity's ability to conduct research that advances our knowledge of physics, biology, materials science, and Earth science.

Future Crew Rotations and ISS Sustainability

Crew-12 is one mission in a series. NASA plans continuous crew rotations to keep the ISS staffed. Crew-13, Crew-14, and beyond are already in training.

This continuous operation model requires reliable launch capabilities. SpaceX must successfully launch crew missions regularly. Falcon 9 reliability has been proven, but spaceflight always carries risk. NASA maintains contingency plans—if SpaceX faces problems, Russian Soyuz spacecraft can still transport crew members.

The rotation schedule is designed so that crew members overlap. When Crew-13 arrives, Crew-12 doesn't immediately leave. There's a handoff period where both crews are aboard. Knowledge transfers. Outgoing crew members help incoming crew members acclimate to the station.

Then Crew-12 boards Dragon and heads home while Crew-13 remains. This staggered approach prevents the knowledge loss that would occur if an entire crew left simultaneously.

NASA plans to maintain ISS operations through at least 2030. That's a decade away, but it's closer than many realize. Discussions about eventual decommissioning and replacement stations are already happening in space agency planning circles.

Whatever comes after the ISS, the lessons learned from continuous operations—resupply, crew rotation, international collaboration—will carry forward. Human spaceflight is evolving. The ISS represents one chapter of a long story.

Crew-12 is a crew rotation. But it's also a moment in human spaceflight history—a demonstration that reliable, routine access to space is becoming real.

Watching the Launch: How to Experience Crew-12

If you're interested in actually watching the February 11 launch, NASA makes this accessible to anyone with internet access.

NASA+ is a dedicated streaming service featuring NASA content. Coverage of Crew-12 launch begins at 4 AM Eastern on February 11. You'll see the rocket on the launch pad, hear expert analysis, and follow the mission in real time.

Amazon Prime Video also streams the launch through a channel. This is accessible if you have a Prime membership, or you can watch through other means.

YouTube hosts NASA's official channel, which streams the launch live. This is free, accessible worldwide, and doesn't require any subscription or account.

For the best experience, here's what to know: Get comfortable. Launch coverage is long. Mission Control communications are technical and include jargon. Annotators explain what's happening, but following every detail requires attention.

The visual payload—actual rocket launch—is concentrated in the first few minutes. Everything before that is preparation and background. Everything after initial stages is orbital operations, which is less visually dramatic but equally important.

If live viewing isn't possible, video recordings of the launch typically become available within hours. NASA archives all mission videos. You can watch on your own schedule.

The experience of watching a launch, even through a screen, connects you to something profound—humans leaving Earth, traveling to the frontier, advancing knowledge. It's worth the 4 AM wake-up, honestly.

Common Questions About Crew Rotations

People often wonder about the basics of how crew rotations work and what they mean for space operations.

How often does NASA rotate crew on the ISS?

Mission durations are approximately six months. Crew rotations happen roughly twice per year—when one crew comes home and another arrives. However, overlap periods mean multiple crews are aboard simultaneously for handoff periods. This continuous rotation keeps the station staffed without operational gaps.

Can crew members stay longer if needed?

Yes, in emergencies. If return vehicle availability becomes constrained, crew members can extend missions. However, six months is near the physiological limit for safe long-duration spaceflight without additional countermeasures. Beyond that, bone density loss and muscle atrophy become concerning. Longer missions require more intensive exercise and sometimes additional medical interventions.

Why does the ISS need seven crew members?

The station covers a large area and requires continuous maintenance across multiple systems. With seven people, crew members can specialize—some focus on experiments, some on American systems, some on Russian systems, some on maintenance. This specialization increases efficiency compared to smaller crews where everyone does everything.

What happens if someone gets sick during a mission?

If illness is minor, the crew manages it with onboard medical supplies. If illness is serious, the affected crew member returns to Earth early aboard Dragon capsule. This happened with Crew-11—one member developed a medical concern that required return and proper diagnosis on Earth.

How do astronauts adapt to returning to Earth after six months?

The transition is difficult. Astronauts lose muscle mass and bone density in microgravity despite exercise. Upon return, gravity feels overwhelming—astronauts can barely walk initially. Physical rehabilitation takes weeks. Over time, the body readapts to Earth gravity. Within a few months, astronauts typically return to normal function, though some effects persist longer.

FAQ

What is Crew-12 and why is it launching to the ISS?

Crew-12 is a NASA crewed spaceflight mission that launches four astronauts—Jessica Meir, Jack Hathaway, Sophie Adenot, and Andrey Fedyaev—to the International Space Station to relieve and replace the current crew. The mission accelerated from a February 15 date to February 11 because Crew-11 returned home early due to a medical concern with one crew member, leaving the ISS with only three people. Crew-12 restores the station to full operational capacity with seven crew members.

How does the SpaceX Dragon capsule get Crew-12 to the ISS?

The Dragon capsule launches atop a Falcon 9 rocket from Cape Canaveral Space Force Station in Florida at 6:01 AM Eastern on February 11, 2025. The rocket achieves orbit, separates from Dragon, and the capsule coasts toward the ISS for approximately 28 hours. Automated systems guide the capsule to dock with the station at approximately 10:30 AM Eastern on February 12. The journey takes this long because the capsule must catch up to the ISS's orbit through a series of calculated orbital maneuvers rather than a direct flight path.

Why did Crew-11 return home early and what was the medical concern?

Crew-11 returned early in January due to a medical concern affecting one crew member. NASA did not disclose specific details about the condition to protect astronaut privacy. The affected crew member was stable, but the ISS lacked the diagnostic equipment needed to properly evaluate and treat the condition on orbit. Medical emergencies in space are managed by returning crew members to Earth where comprehensive medical care is available. This conservative approach prioritizes crew safety over mission schedules.

What experiments and research will Crew-12 conduct?

Crew-12 will conduct multiple scientific investigations across biology, materials science, combustion research, crystal growth, pharmaceutical development, and Earth observation. Research benefits from microgravity conditions impossible to replicate on Earth. Crew-12 members will also maintain station systems, perform external spacewalks if necessary, and oversee equipment that gathers data on Earth's climate and environmental conditions. The full crew of seven can dedicate more time to experiments compared to the understaffed period when only three crew members were aboard.

How long will Crew-12 stay on the ISS?

Crew-12 is expected to remain on the ISS for approximately six months. This duration balances mission efficiency with astronaut physiological constraints. Longer stays require more intensive exercise and countermeasures to prevent excessive bone density loss and muscle atrophy. At the end of their mission, Crew-12 will board the Dragon capsule and return to Earth, splashing down in the Atlantic Ocean where recovery teams await.

What makes this mission different from previous crew rotations?

Crew-12's accelerated timeline—moving from February 15 to February 11—reflects operational flexibility and the priority of restoring full crew capacity to the ISS. The mission also demonstrates the routine nature of modern crew rotations using commercial spaceflight providers like SpaceX. However, every mission is unique in its crew composition, specific experiments, and operational challenges. Crew-12 is notable for restoring the station to full scientific productivity after the abbreviated Crew-11 mission.

Can I watch the Crew-12 launch live?

Yes, NASA provides free, live streaming of the launch through multiple platforms. NASA+ (a dedicated streaming service) will begin coverage at 4 AM Eastern on February 11. Amazon Prime Video also streams the launch. YouTube hosts NASA's official channel with live coverage. Coverage includes expert commentary explaining the mission, technical details, and real-time updates. Video recordings of the launch are archived and available for later viewing if live viewing isn't possible.

What is the ISS and why is it important to maintain crew rotations?

The International Space Station is a large spacecraft in low Earth orbit housing scientific research facilities, life support systems, and habitation modules. It's jointly operated by NASA, Roscosmos, ESA, JAXA, and CSA. Continuous crew rotations keep the station staffed, conduct critical scientific research, maintain equipment, and demonstrate international cooperation in space. The ISS serves as a testbed for technologies needed for lunar bases and deep space missions, making crew rotations essential for advancing human spaceflight capabilities.

How does the international partnership work on the ISS during Crew-12?

Crew-12 includes two NASA astronauts, one European Space Agency astronaut, and one Roscosmos cosmonaut. These crew members operate both American and Russian systems, conduct experiments from multiple countries, and work collaboratively despite geopolitical tensions on Earth. The ISS demonstrates that space agencies can maintain operational partnerships focused on shared scientific goals. Crew members receive cross-training in each other's systems, speak multiple languages, and manage the station jointly according to agreements established in the 1990s.

What are the risks of the Crew-12 mission?

Every spaceflight carries inherent risks—launch G-forces, ascent hazards, potential mechanical failures, and reentry challenges. NASA and SpaceX have conducted extensive analysis, testing, and simulations to minimize these risks. Redundant systems back up critical functions. Weather delays the mission if conditions don't meet safety criteria. Medical screening ensures crew health before launch. Despite these precautions, spaceflight remains inherently risky—a reality space agencies acknowledge openly while working continuously to improve safety.

How will the return of Crew-12 work at the end of their mission?

After approximately six months on the ISS, Crew-12 will board the Dragon capsule and undock from the station. The capsule will perform atmospheric reentry using heat shields to dissipate extreme temperatures. Parachutes will deploy at lower altitude, slowing the descent to approximately 20 miles per hour. The capsule will splash down in the Atlantic Ocean where recovery ships retrieve it. Crew members will exit the capsule and begin medical evaluations and rehabilitation to readapt to Earth gravity. Post-mission health monitoring continues for weeks as researchers study physiological adaptations to spaceflight.

Looking Ahead: The Future of Human Spaceflight

Crew-12 represents a moment where spaceflight is becoming routinized. Launches happen regularly. Crew rotations are planned events. Commercial companies handle transportation. This wasn't always the reality.

Two decades ago, spaceflight was episodic. Missions were rare events. Each launch was a major news story. Now, Crew-12 might be overlooked by mainstream media. It's routine.

That normalization is significant. It means spaceflight is maturing. It means humans are achieving regular, reliable access to orbit. It means the frontier is becoming inhabited.

But challenges remain. The ISS has a planned lifetime. Decisions about what comes next are being made now. Will there be commercial space stations? Will agencies build new dedicated research facilities? Will spaceflight shift toward lunar operations and deep space exploration?

Crew-12 is one mission in a longer story. It's a chapter where human spaceflight is reliable enough to schedule crew rotations months in advance. It's a moment where international cooperation persists despite political differences. It's a demonstration that reaching space, once impossible, is now routine.

Watching Crew-12 launch, if you get the chance, connects you to that broader story. Four people will leave Earth. They'll orbit for six months. They'll conduct experiments. They'll make discoveries. Then they'll come home.

That simple arc—up, work, return—represents hundreds of years of human aspiration finally realized. Spaceflight is becoming real. Crew-12 is proof.

The future of human spaceflight is being written in real time. Crew-12 is part of that narrative. So are the dozens of other missions being planned, tested, and prepared. So are the space agencies, commercial companies, and thousands of people working to make spaceflight safer, more reliable, and more routine.

From that perspective, February 11 isn't just another launch date. It's a day when humanity continues reaching beyond our planet, exploring, learning, and advancing knowledge in the environment where we can't naturally survive. That's worth paying attention to.

Key Takeaways

- Crew-12 launches February 11, 2025 at 6:01 AM Eastern from Cape Canaveral aboard SpaceX Dragon, docking with ISS 28 hours later

- Mission accelerated from February 15 to February 11 because Crew-11 returned early, leaving ISS with only three crew members instead of eight

- Four crew members (two NASA astronauts, one ESA astronaut, one Roscosmos cosmonaut) restore ISS to full seven-person operational capacity

- ISS requires continuous crew rotation every six months to maintain scientific research productivity and station operations

- SpaceX's reusable Dragon and Falcon 9 have made crew transportation routine, representing a major evolution in commercial spaceflight

Related Articles

- NASA Astronauts Can Now Take Smartphones to Space [2025]

- NASA Astronauts Can Now Bring Smartphones to the Moon [2025]

- Blue Origin Pauses Space Tourism for NASA Lunar Lander Development [2025]

- Lunar Spacesuits: The Massive Challenges Behind Artemis Missions [2025]

- NASA's Fraggle Rock Space Adventure: Muppets Meet Moon Exploration [2025]

- Why NASA Finally Allows Astronauts to Bring iPhones to Space [2025]

![NASA Crew-12 Mission to ISS: Everything About February 11 Launch [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/nasa-crew-12-mission-to-iss-everything-about-february-11-lau/image-1-1770480403629.jpg)