David Greene Sues Google Over Notebook LM Voice: The AI Voice Cloning Crisis [2025]

David Greene was doing what he does best on a Tuesday morning, preparing for another episode of his radio show, when his phone started buzzing. Texts from friends. Emails from family. Messages from colleagues all asking the same question: "Did you know your voice is in Google's Notebook LM?"

He didn't. And that's exactly the problem.

Greene, the longtime host of NPR's "Morning Edition" and current host of KCRW's "Left, Right, & Center," has spent decades building an instantly recognizable voice. It's warm, conversational, authoritative yet accessible. It's the voice that wakes up millions of Americans every morning. And according to Greene's lawsuit, Google used that voice without permission to create the male podcast host voice in its Notebook LM AI tool.

This isn't just a legal dispute between a media personality and a tech giant. It's a watershed moment in the artificial intelligence revolution. As AI tools become increasingly sophisticated at mimicking human voices, the lines between inspiration, imitation, and outright theft are blurring at unprecedented speed. The Greene lawsuit throws a spotlight on fundamental questions that will define the next decade of AI development: Who owns a voice? Can a voice be copyrighted or trademarked? What rights do public figures have when their distinctive characteristics are replicated by machines?

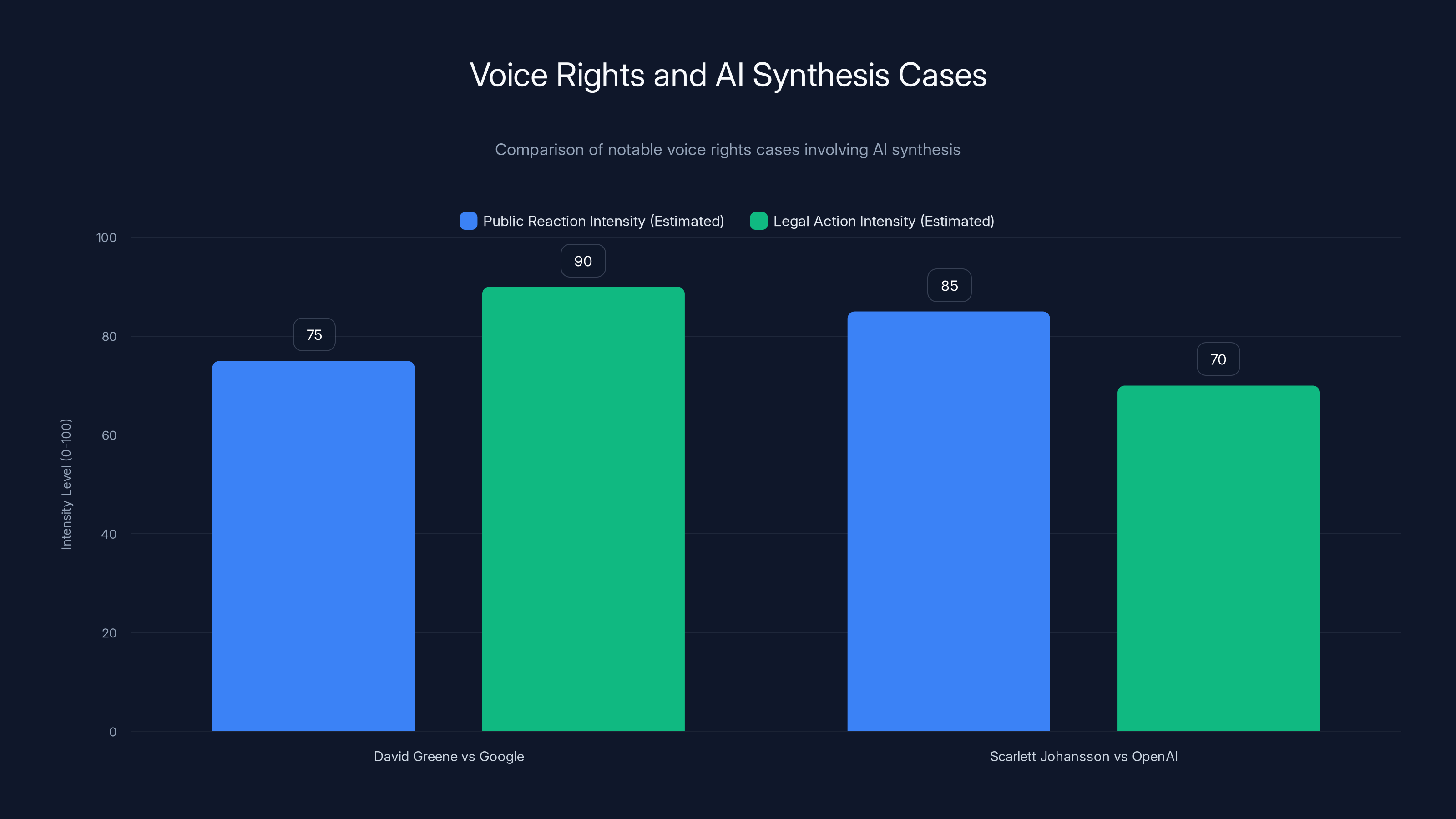

What started as a few confused emails has become one of the most significant legal challenges to AI voice technology since Scarlett Johansson's complaint against Open AI. And it's raising uncomfortable questions about whether the current legal framework can actually protect people from having their essence digitized and repurposed without consent.

TL; DR

- The Lawsuit: NPR host David Greene sued Google, claiming Notebook LM's male voice mimics his cadence, intonation, and distinctive filler words like "uh"

- The Defense: Google claims it hired a paid professional actor and the voice is unrelated to Greene

- The Precedent: Similar to Scarlett Johansson's complaint against Open AI, which led to voice removal

- The Bigger Issue: No clear legal framework exists for protecting voice identities in the AI era

- The Stakes: This case could reshape how AI companies source and train voice models

The David Greene case shows higher legal action intensity, while Scarlett Johansson's case had a stronger public reaction. Estimated data based on case impact.

Understanding the David Greene Notebook LM Lawsuit

The lawsuit emerged in early 2025 as Greene, along with his legal team, filed formal complaints against Google alleging that the company had replicated his voice without authorization. The specificity of the complaint is crucial. Greene didn't just say the voice sounded similar. He pointed to particular vocal characteristics: the distinctive cadence, the specific intonation patterns, the frequent use of filler words like "uh," and the overall conversational tone that has become his trademark.

Notebook LM itself is actually a genuinely useful tool. Launched by Google in 2023, it allows users to upload documents, articles, research papers, or other text materials and then generate audio podcasts where AI hosts discuss the content. The tool gained significant attention in mid-2024 when Google introduced the Audio Overviews feature, which automatically transforms written content into engaging podcast-style conversations between two AI hosts.

The male voice in this feature became immediately recognizable to anyone who listened. It had warmth, personality, and that conversational quality that makes podcast listening feel like hanging out with someone knowledgeable. Which is probably why so many of Greene's friends and colleagues noticed the resemblance. Greene has been on the radio for decades. His voice is familiar to millions. When that same voice suddenly appears in your AI tool, the similarities don't go unnoticed.

What makes this lawsuit particularly interesting is the timing and the evidence Greene reportedly gathered. According to accounts, Greene didn't immediately rush to his lawyers. Instead, he did what any reasonable person would do: he investigated. He listened to the Notebook LM voice repeatedly. He compared it to his own voice. He had others listen and offer their opinions. The consistency of external confirmation—that his friends, family, and colleagues all independently noticed the similarity—became part of his evidence.

This isn't a case where someone is claiming a vague similarity. This is a case where multiple independent observers recognized specific vocal characteristics. That distinction matters legally because it suggests the similarity isn't in the listener's imagination but in actual acoustic properties of the voice itself.

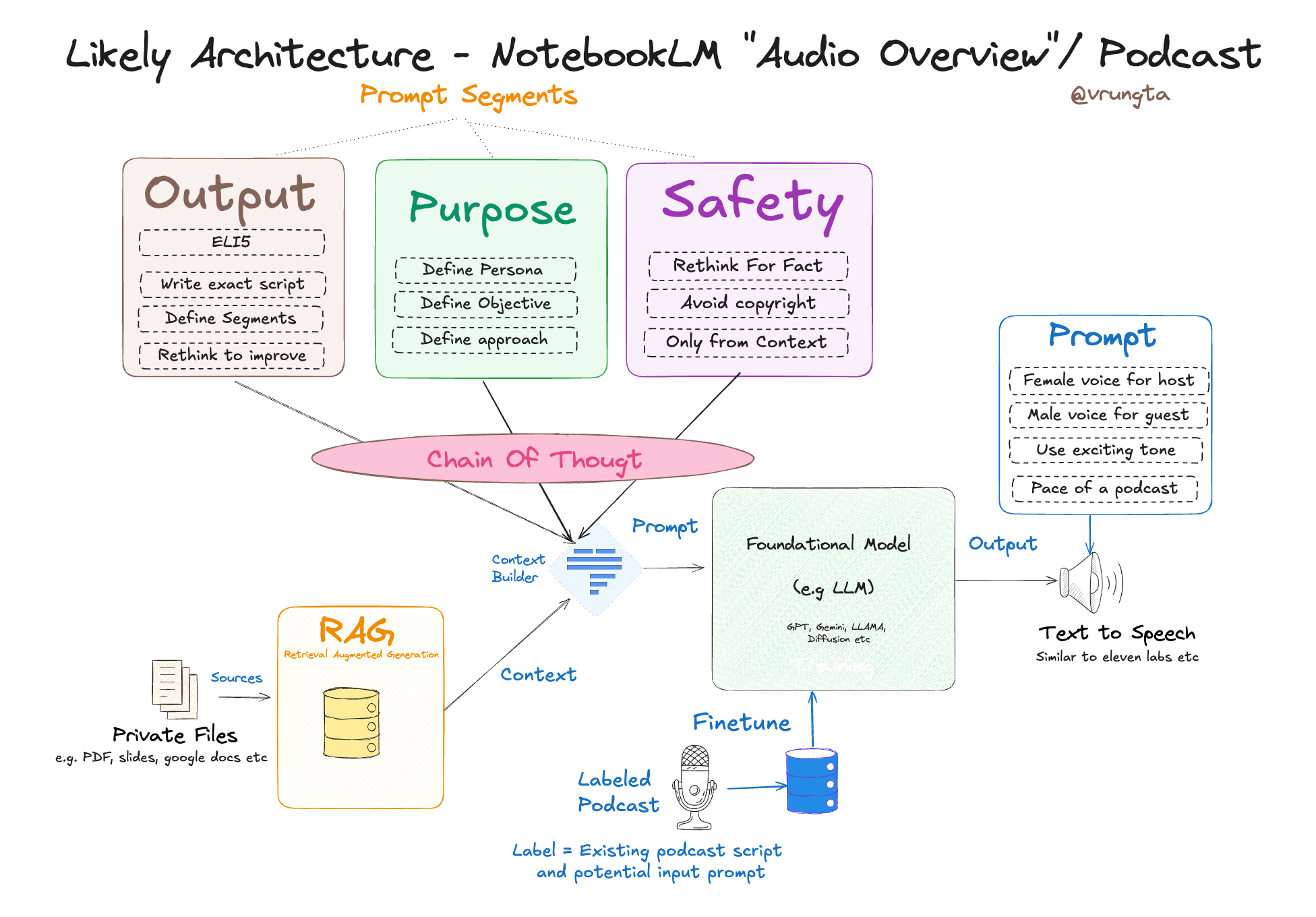

How Notebook LM's Audio Overviews Technology Works

Understanding the technical foundation of Notebook LM is essential to understanding why this lawsuit might succeed or fail. The tool uses sophisticated text-to-speech and voice synthesis technology, but it's not as simple as just running text through a generic voice model.

When a user uploads a document to Notebook LM, the AI first reads and analyzes the content. It identifies key concepts, themes, and structure. Then it generates a script for two AI hosts to discuss. This script includes natural conversational elements—interruptions, agreements, questions, and tangents—that make the output sound less like a robot reading facts and more like two smart people having a genuine conversation about the topic.

The voice synthesis component is where things get legally complicated. Google's Audio Overviews feature uses what the company calls "personalized voice synthesis." This means the AI doesn't just convert text to speech in a generic voice. It generates speech that has personality, inflection variation, emotion, and the kind of vocal quirks that make someone sound like a specific person.

The company has stated that the male voice was created based on a "paid professional actor" that Google hired. This is Google's defense. They're saying the voice came from an actual human being who was compensated for providing voice data. This is a legitimate approach to voice synthesis. Many companies, from audiobook publishers to video game developers to commercial AI voice services, work with professional voice actors who consent to having their voices recorded and used for synthesis models.

But here's where it gets murky. If Google did hire a professional actor, why does the resulting synthetic voice sound so much like David Greene? There are a few possibilities. One is coincidence, though that seems unlikely given the specificity of the complaint. Another is that Google trained the model on audio that included Greene's voice. Another is that the professional actor they hired was instructed to emulate Greene's vocal style. Or Greene's voice was used as reference material during the voice development process.

The technical process of creating a voice synthesis model typically involves recording hundreds of hours of a real person speaking. The AI then analyzes the audio at multiple levels: phonetic characteristics, pitch variations, timing, stress patterns, and all the subtle features that make a voice distinctive. Once trained, this model can generate new speech that sounds like that person saying things they never actually said.

This technology is incredibly powerful. It's also incredibly dangerous when misused. Because once a voice model is trained, it can generate completely new utterances that sound authentic to the original speaker. David Greene never recorded himself discussing Google's Notebook LM tool. But if you have a well-trained voice model based on his voice, you can make him say anything.

The lawsuit against Google by David Greene highlights key events from the launch of NotebookLM in 2023 to the lawsuit in early 2025. Estimated data.

The Scarlett Johansson Precedent and AI Voice Disputes

Greene's lawsuit didn't emerge in a vacuum. It follows a significant precedent that happened just a year earlier, when actress Scarlett Johansson publicly complained about a voice in Chat GPT that she believed was imitating her without consent.

Open AI released Chat GPT with voice capabilities in September 2023. One of the voice options, called "Sky," had a warm, intimate, conversational tone. Johansson heard the voice and was immediately concerned. According to her account, the voice was remarkably similar to her own. More importantly, she said she had previously been approached by Open AI leadership about licensing her voice for Chat GPT, and she had declined. Yet here was a voice that sounded very much like her.

Johansson took action. She sent a cease-and-desist letter. She went public with her complaint. Open AI initially defended the voice, explaining that it was developed by a real voice actor and was unrelated to Johansson. But the pressure was immense. Users of Chat GPT were saying the same thing Johansson said: the voice sounded like her. Within days, Open AI removed the Sky voice from Chat GPT entirely.

The incident was revealing in several ways. First, it showed that even Open AI, one of the most technologically sophisticated companies in the world, apparently didn't anticipate that a voice created from a professional actor could so closely resemble a celebrity. Second, it demonstrated that public pressure and reputational risk can move companies faster than legal threats. Third, it highlighted the fact that there's no clear legal precedent protecting voice identity rights in the AI era.

Open AI never formally admitted wrongdoing. They never paid Johansson. They never provided detailed technical information about how the Sky voice was created. They simply removed it to avoid further controversy. This approach worked for Open AI but set a worrying precedent: if you're important enough, you can get tech companies to change their behavior, but there's no legal framework ensuring accountability or compensation.

The Johansson case also revealed something important about how voice similarity happens. When people listen to two voices, they're not just comparing basic acoustic properties. They're comparing personality, style, emotional tone, and distinctive mannerisms. A voice that hits the same emotional notes and has similar timing and rhythm patterns can feel like an imitation even if the actual acoustic frequencies are slightly different.

This is why Greene's case is so compelling. He's not just claiming acoustic similarity. He's pointing to behavioral vocal characteristics: the way he uses pauses, the filler words he prefers, the rhythm of his speech. These are learned patterns that are absolutely replicable in a trained voice model. And if someone intentionally or unintentionally trained a model to capture these patterns, the resulting voice would indeed sound like Greene.

Why Voice Identity Matters: The David Greene Perspective

Greene's statement during this controversy is worth examining in detail. He said, "My voice is, like, the most important part of who I am." This isn't hyperbole from a performer. It's a profound truth about voice work, particularly in radio and podcasting.

Radio is an intimate medium. When you listen to a radio host, you're not getting visual cues. You can't see their face, their gestures, their appearance. You only have their voice. Everything you know about them, everything you connect with, comes through acoustic signals. A radio host's voice is their entire brand, their complete identity in the medium. This is why radio hosts often sound the same whether they're on the air or just talking to friends. The voice is the person.

For someone like Greene, who has spent decades building a career in radio, the voice is not just a tool. It's the core asset of his professional identity. His voice has value. When people hear it, they know it's him. That recognition has been built through hundreds of hours of broadcasting, through consistent presence, through the development of a distinctive style.

When Google allegedly used a voice based on Greene's characteristics without permission, they weren't just using a voice. They were using his brand, his identity, his years of work building recognition and trust. Every person who heard the Notebook LM male voice and thought of Greene was having their mental association of that voice exploited by Google.

Moreover, there's a potential competitive harm. If users associate the Notebook LM voice with Greene, they might assume he endorses the tool or is involved with it. They might think Greene is being paid for this. The unauthorized use of someone's distinctive voice could constitute endorsement by implication, which is a form of commercial exploitation.

There's also the question of voice rights more broadly. If you develop a distinctive voice over decades of professional work, shouldn't you have some legal protection over that asset? The law already recognizes this principle in other contexts. Musicians have rights to their recordings and compositions. Actors have rights to their likenesses. But voice rights are murky. Radio personalities have long worked under the assumption that their voices were part of their professional property, but the law hasn't always backed this up.

The Legal Framework: What Protects Voice Rights?

This is where things get complicated. The legal landscape around voice rights in the United States is fragmented and underdeveloped. There's no clear federal law that says, "You cannot replicate someone's voice without permission." Instead, legal protection for voices comes from a patchwork of different statutes and legal theories.

Right of Publicity and Voice Identity

The most relevant legal framework is the "right of publicity," which is a state-level right (not federal) that protects against the unauthorized commercial use of a person's identity. This right has been extended in many jurisdictions to include distinctive voices. The idea is that if your voice is distinctive and recognizable, it's part of your identity, and its commercial exploitation without permission is illegal.

However, the right of publicity varies significantly by state. Some states have very strong protections. California, for example, has broad right of publicity statutes that explicitly include voice and vocal characteristics. Other states have weaker protections or none at all. This creates a patchwork problem where the same conduct might be legal in one state and illegal in another.

Moreover, the right of publicity requires proving that your voice is distinctive and that the imitation is recognizable. This is where expert testimony becomes crucial. Acoustic experts can analyze voices and testify about similarities. But ultimately, a judge or jury has to decide whether the similarity is substantial enough to constitute a violation.

Copyright and Voice Protection

Another possible legal avenue is copyright. If Greene recorded himself speaking, those recordings are protected by copyright. Google can't simply copy his recordings and use them. But what if Google created a voice model that synthesizes Greene-like speech without using his actual recordings?

Copyright becomes much weaker in this scenario. Copyright protects specific creative works, not the style or characteristics of creative works. If you write a song in the style of Bob Dylan, Dylan can't sue you for copyright infringement just because your song sounds like his. He can only sue if you copied his actual song.

The same principle applies to voices. If Google created a new voice that happens to sound like Greene but didn't actually copy his audio files, copyright might not provide protection. This is where the legal system falls short for voice rights in the AI era.

Unfair Competition and Trade Dress

Another possible legal theory is unfair competition. If Greene can prove that Google deliberately created a voice to ride on his reputation and confuse consumers, he might have a claim for unfair competition or trade dress violation. Trade dress protects distinctive characteristics of products or services that consumers use to identify the source.

A distinctive voice could potentially be protected as trade dress if it's consistently used to identify a particular service or personality. But this requires proving that consumers actually use the voice to identify the source and that Google's use is likely to confuse them.

Vocal Likeness Rights and the AI Gap

The fundamental problem is that none of these existing legal frameworks were designed for AI voice synthesis. They were designed when voice imitation meant finding a skilled impressionist who could mimic someone. Now, voice imitation is something any company with AI training data and computing resources can do at scale.

This legal gap is exactly what Johansson's complaint highlighted and what Greene's lawsuit is trying to address. If the existing legal framework doesn't clearly protect voice rights, then courts need to extend that protection or legislatures need to create new laws.

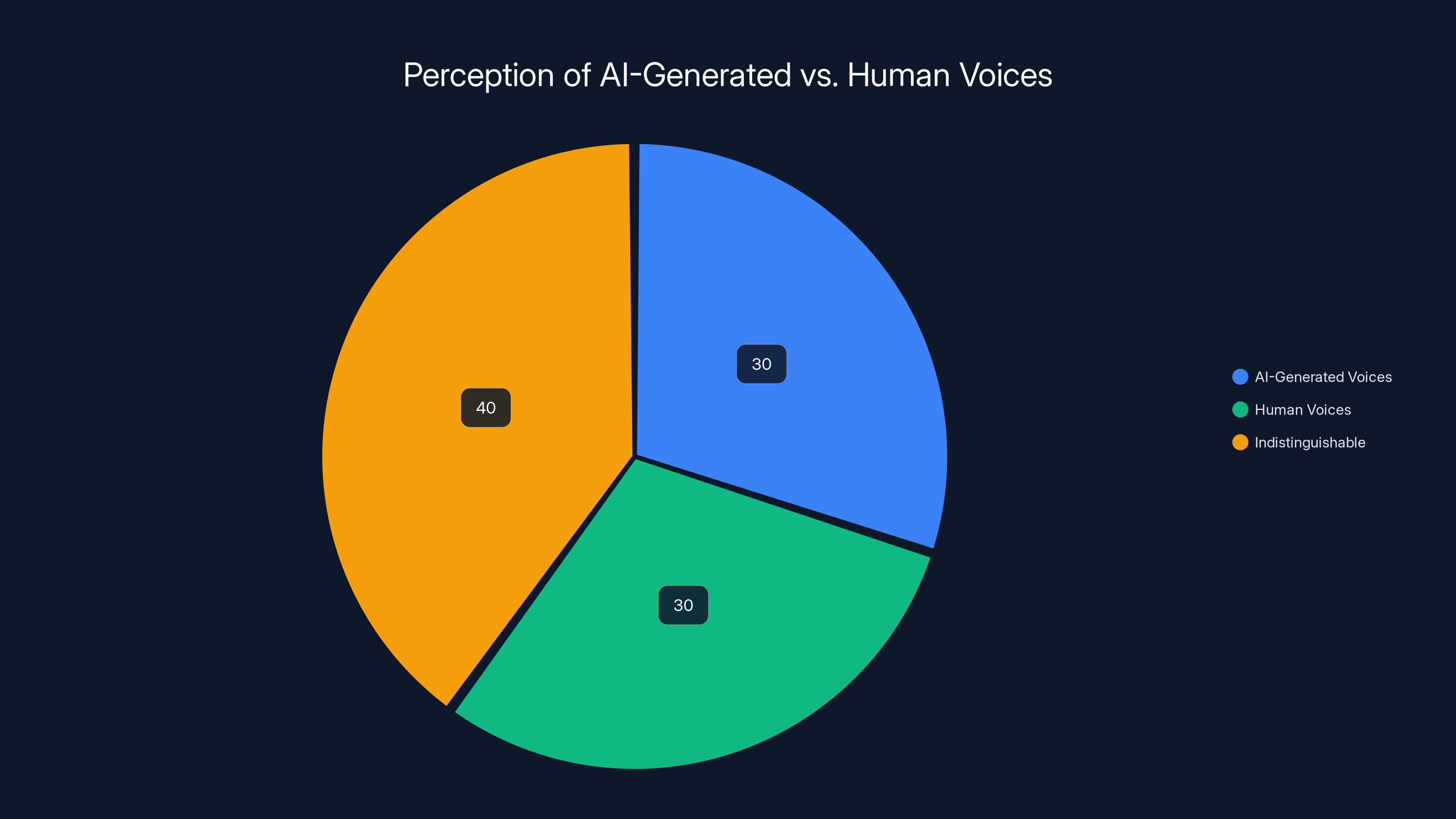

In blind listening tests, 40% of participants found AI-generated voices indistinguishable from human voices, highlighting the advanced state of voice synthesis technology by 2024. (Estimated data)

How AI Companies Source Voice Data: The Technical Reality

Understanding how AI companies actually source voice data is crucial to understanding whether Google's defense holds water. When Google says it hired a professional actor, what does that actually mean? And could that process inadvertently result in a voice that resembles a specific celebrity?

The Professional Voice Actor Route

The standard approach to creating a voice synthesis model is to hire a voice actor with distinctive qualities and record them reading scripts for many hours. The AI then learns to mimic that voice. This is a legitimate, consensual process. The actor knows they're being recorded and consents to their voice being used for AI synthesis.

Companies like Amazon (for Polly), Google (for Cloud Text-to-Speech), and others use this approach. They hire professional voice actors, often people who have done commercial voice work or audiobook narration. The actors are compensated for their work, and the resulting voice models become commercial products.

The defense makes sense on the surface. But there are several ways this process could result in a voice that resembles a celebrity without that celebrity being involved.

The Reference Material Problem

Here's where it gets murky. What if the voice actor Google hired was given reference material? What if the direction was something like, "We want a voice that sounds warm and personable like NPR hosts. Study these clips and develop a voice in that style." If those reference clips included David Greene, then the resulting voice model might intentionally or unintentionally capture Greene's distinctive characteristics.

This scenario isn't hypothetical. In creative fields, reference material is standard. Animators study movements to learn how to animate. Musicians study recordings to learn style. Voice actors study existing voices to develop new ones. If Google was trying to create a voice suitable for a podcast AI (which is what Notebook LM does), they would logically have studied successful podcast and radio voices. And David Greene is one of the most successful, recognizable radio voices in America.

The Training Data Contamination Issue

Another possibility is more technical. AI voice models are trained on large datasets of audio. What if the training data included David Greene's voice without explicit inclusion? If Google trained their voice synthesis model on a general dataset of podcasts, radio broadcasts, and interview audio that happened to include thousands of hours of Greene's voice from NPR broadcasts, the model might learn to mimic his distinctive characteristics.

This is actually a serious problem in AI development. Training datasets often contain audio from publicly available sources, and companies might not explicitly identify every voice in their training data. If a voice model is trained on hundreds of thousands of hours of audio, it will learn patterns from all the voices in that data. A distinctive voice that appears frequently in the training data will be more strongly represented in the model.

The Transfer Learning Possibility

There's also the possibility of transfer learning. Maybe Google created the base voice model using a professional actor, but then they fine-tuned the model using other audio data. Fine-tuning is a technique where you take an existing trained model and train it further on a new dataset. This can shift the characteristics of the model. If they fine-tuned on data that included Greene's voice, the model might have shifted toward his vocal characteristics.

The Commercial Implications: Why This Matters Beyond Law

Beyond the legal questions, there are significant commercial implications of voice cloning in AI tools. If companies can create AI voices that sound like celebrities without compensation, it devalues the commercial worth of distinctive voices.

Voice as a Commercial Asset

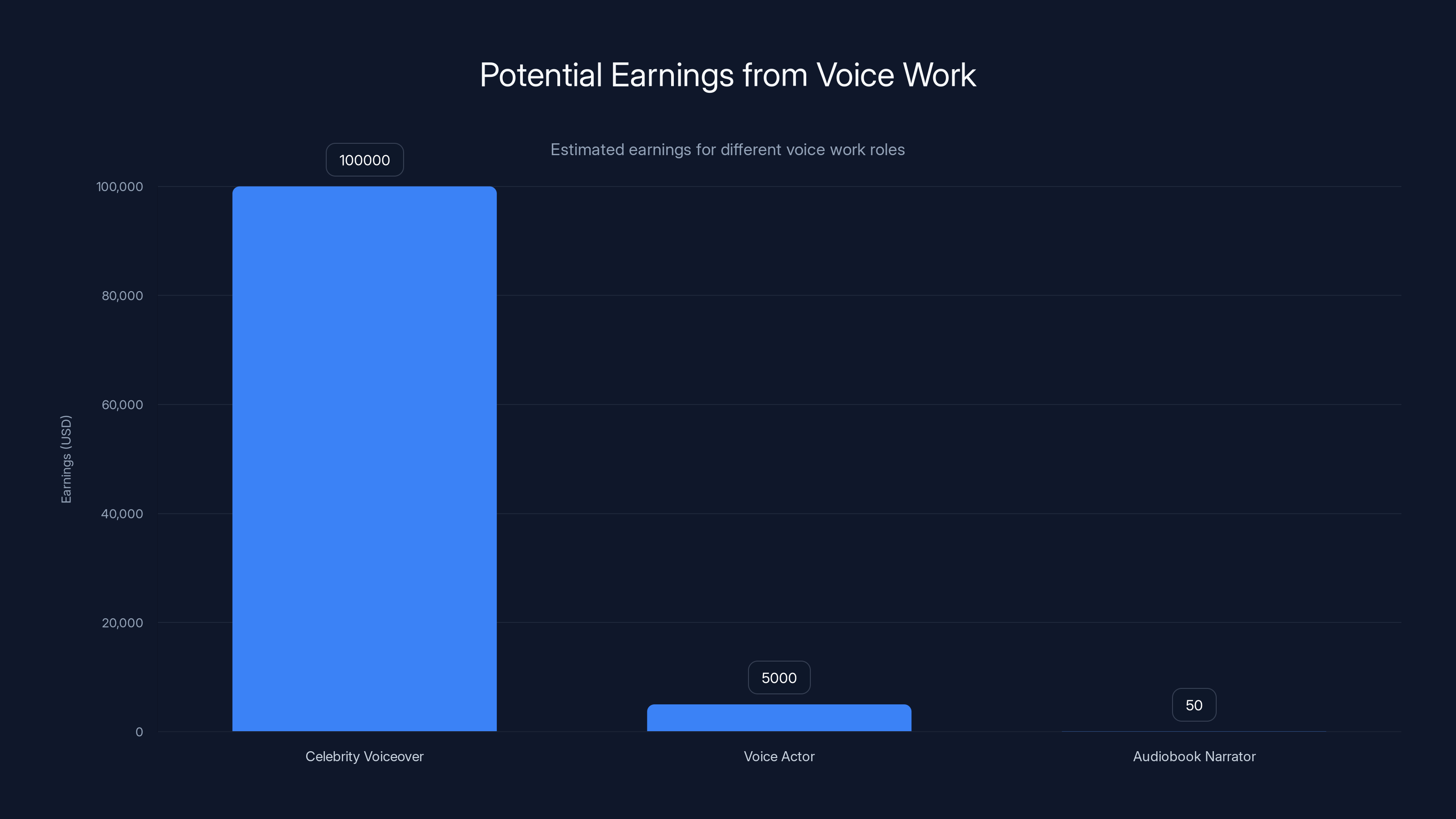

Professional voices have been commercial assets for decades. Voice actors, celebrities, and media personalities have long been able to monetize their voices. A celebrity might charge six figures to do a voiceover for a commercial. A voice actor might earn thousands per hour for commercial recording work. An audiobook narrator might earn 50 percent or more of the profits from a book they narrate.

These earnings exist because distinctive voices have value. People want to hear famous voices. They'll pay for audiobooks narrated by celebrities. They'll watch commercials because they feature celebrity voices. The distinctive characteristics that make a voice valuable are what enable this monetization.

But if AI companies can create synthetic versions of these voices without compensation, the commercial value evaporates. Why hire David Greene to do a voiceover when you can generate his voice for free using AI? This isn't hypothetical. This is exactly what's starting to happen.

The Gig Worker Problem

There's also a parallel issue affecting non-famous voice workers. Voice actors and narrators are worried that their voices will be captured, synthesized, and then used in ways they never consented to. Some voice actors are starting to refuse to work with companies that want to create voice synthesis models. Others are demanding significantly higher compensation.

This creates a labor market distortion. If companies can use AI to replace voice actors, voice acting becomes less valuable as a profession. This is why some in the voice acting community are calling for stronger legal protections and regulations on voice synthesis in AI.

The Brand Extension Risk

For celebrities and media personalities, there's also a brand extension risk. If an AI tool using your voice makes statements you disagree with or appears in contexts you don't approve of, it could damage your reputation. Greene apparently didn't endorse Notebook LM or appear in any marketing for it. Yet his voice was associated with the product. This is a form of unauthorized brand exploitation.

Consider the implications if the Notebook LM voice had said something controversial. Greene would be the one receiving criticism, even though he had nothing to do with it. This is why voice rights matter beyond just financial compensation. They're about protecting someone's ability to control their own reputation and brand associations.

Industry Response: How Tech Companies Are Reacting

The Greene lawsuit is coming at a critical moment for AI voice technology. Several major tech companies are grappling with similar issues, and the industry response reveals how contested this terrain is.

Google's Position and Defense

Google has maintained that the Notebook LM voice was created from a professional actor and is unrelated to Greene. But the company has been relatively quiet beyond this initial defense. They haven't published detailed technical documentation about how the voice was created or provided the kind of transparency that might satisfy concerns.

This silence might be strategic. Full transparency about how voice models are created could expose Google to liability. If they revealed that they used reference material or training data that included Greene's voice, they'd be admitting to some level of involvement with his vocal characteristics. By remaining vague, they maintain plausible deniability.

However, this approach also invites speculation and conspiracy thinking. When companies don't provide clear information about how they created something controversial, people assume the worst. Public trust in Google's explanation is likely lower than it would be if they provided detailed technical transparency.

Open AI's Approach: Removal Over Explanation

Open AI's handling of the Scarlett Johansson voice issue set a different precedent. Instead of defending the voice, Open AI simply removed it. This approach—remove the controversial product and move on—has become a pattern in tech industry responses to voice cloning concerns.

But this approach also avoids accountability. By removing the voice without investigation or explanation, Open AI avoided clarifying whether the similarity was intentional, accidental, or coincidental. They avoided setting a clear precedent about what's acceptable. They just made the problem disappear.

Industry Calls for Standards

There's growing momentum in the tech industry for developing standards around voice synthesis. Industry groups are working on principles for ethical AI voice development. These often include commitments to disclose when voice synthesis is being used, to get explicit consent from people whose voices are used as reference material, and to maintain transparency about training data sources.

But industry standards are voluntary and weak. Without legal enforcement, they're mostly PR exercises. A company can sign onto an industry standard and then violate it with minimal consequences.

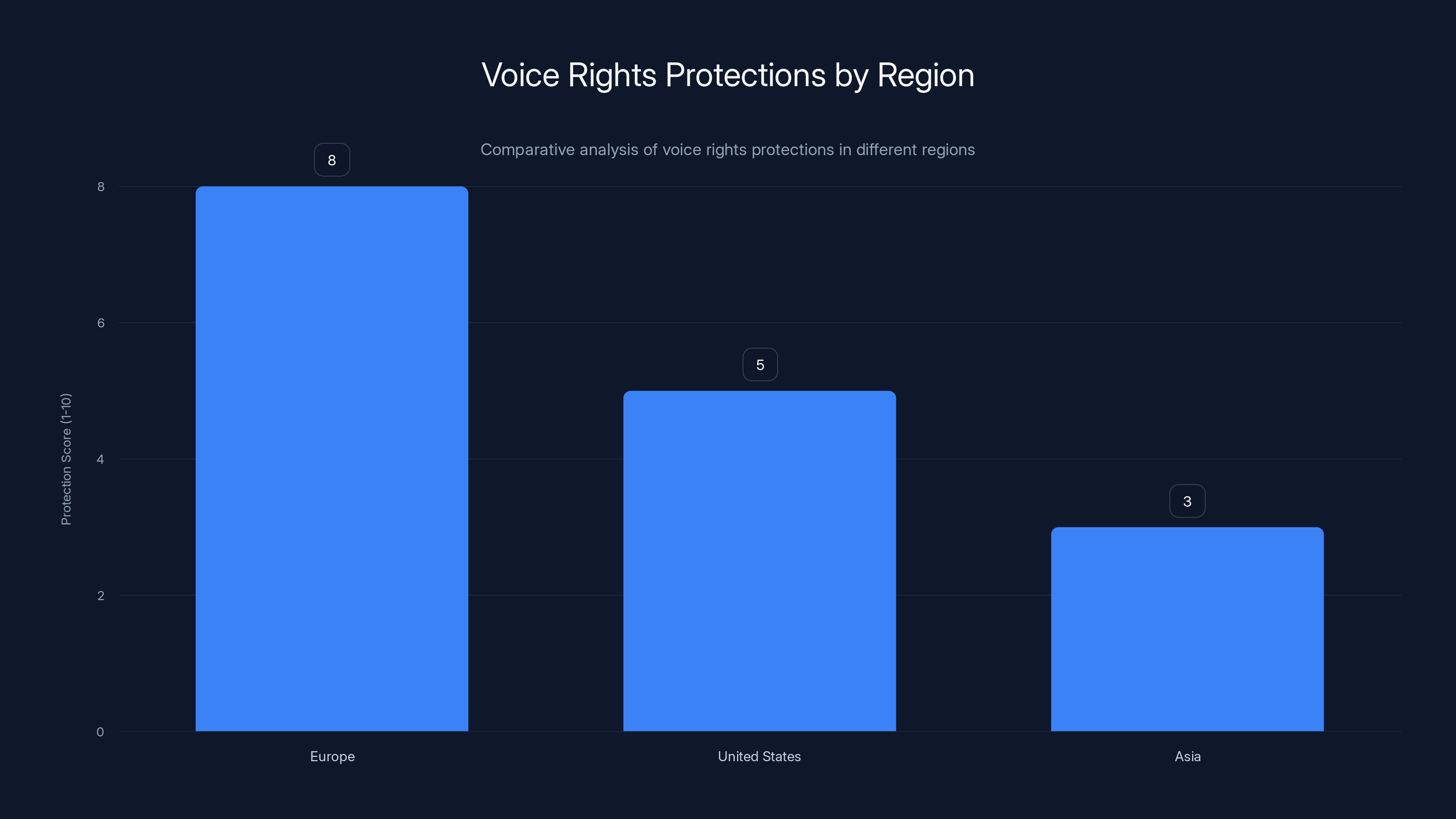

Europe leads in voice rights protections with a score of 8, followed by the U.S. at 5, and Asia at 3, reflecting their focus on innovation over privacy. Estimated data.

The Broader AI Voice Cloning Ecosystem

The Greene lawsuit isn't just about Google and Notebook LM. It's happening in the context of an entire ecosystem of voice cloning and synthesis technologies that are becoming increasingly accessible and sophisticated.

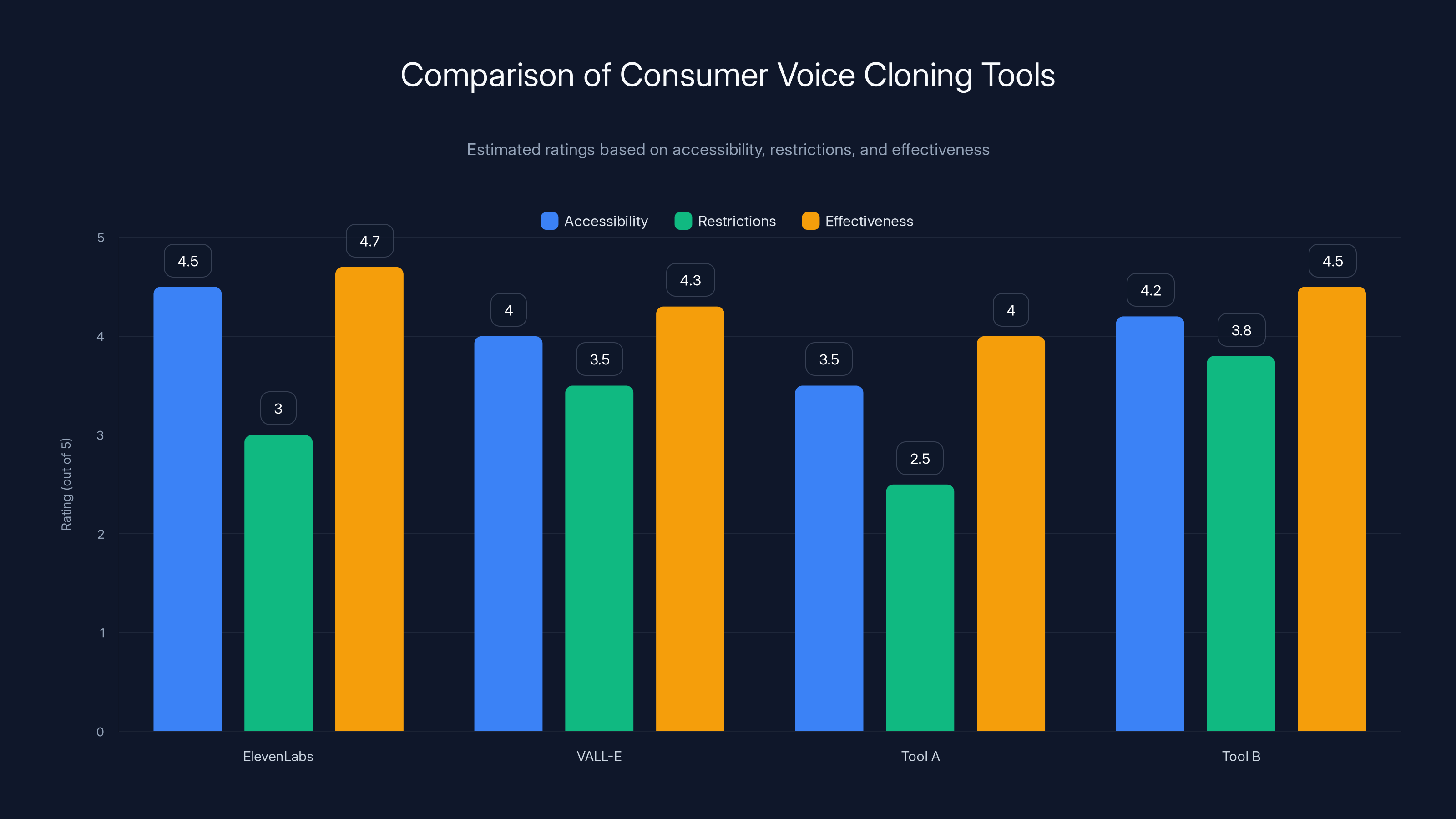

Consumer Voice Cloning Tools

There are now dozens of consumer-facing voice cloning tools. Services like Eleven Labs, VALL-E, and others allow anyone to upload a few seconds of audio and create a voice synthesis model that can generate new speech in that voice. Some of these services explicitly require consent and have terms of service prohibiting the cloning of celebrity voices. Others are much looser about restrictions.

The democratization of voice cloning technology means that anyone can now create a synthetic version of anyone else's voice. You don't need a tech company's resources. You just need the internet and a small amount of money. This makes the problem exponentially larger than just what Google is doing with Notebook LM.

Deepfake Voice Risk

Voice cloning technology is also being used to create deepfake audio. Criminals and malicious actors are using voice synthesis to impersonate people in phone calls, audio messages, and other contexts. Police have reported cases where voice cloning was used to impersonate officials or commit fraud. Voice cloning enables a new category of crime that existing laws don't adequately address.

This criminal use of voice synthesis puts additional pressure on the legal system to develop clearer rules around voice rights and voice synthesis.

Legitimate Applications and the Boundaries

Not all voice synthesis is problematic. There are genuinely beneficial applications. Text-to-speech tools help people with disabilities. AI narration makes audiobooks more accessible. Synthetic voices in customer service applications improve user experience for many people. The challenge is distinguishing between legitimate applications and exploitative ones.

The distinction usually comes down to consent and transparency. If someone consents to their voice being synthesized and knows how it will be used, that's generally acceptable. If the synthesis happens without consent or without transparency about how the voice will be used, that's problematic.

Legal Precedent and What Courts Might Decide

If the Greene lawsuit makes it to trial, what might courts decide? We can look to similar cases and legal principles to make educated guesses.

The Voice Distinctiveness Standard

Courts that have dealt with voice-related intellectual property issues have generally required proving that a voice is distinctive and recognizable. This is sometimes called the "secondary meaning" test. The idea is that a voice has secondary meaning if the public associates it with a particular person or product.

Greene likely meets this standard. His voice is distinctive. The public associates it with him and with NPR. This would help his case.

The Confusion Standard

Another standard courts use is whether the imitation is likely to confuse consumers or create false association. If people listening to the Notebook LM voice think it's David Greene or think he's endorsing the product, that's a form of confusion that courts care about.

Greene's complaint that his friends and colleagues immediately recognized the voice suggests there's a real confusion issue. If random listeners are thinking it's Greene, that's a serious problem for Google's defense.

The Intent Question

Courts often consider whether the defendant intended to create confusion or capitalize on someone's reputation. If Greene can prove that Google deliberately chose to create a voice resembling his, that strengthens his case. If it was accidental, it weakens it.

But here's the problem: proving intent in a technical process involving AI is extremely difficult. How do you prove intent when the final voice emerges from complex machine learning processes? Did someone explicitly decide to make the voice sound like Greene, or did it just happen as a side effect of the training process?

Damages and Remedy

If Greene wins, what would be the remedy? Courts typically award damages, which could include:

- Compensatory damages: Money to compensate for harm, which might include lost licensing fees for voice work, damage to professional reputation, or emotional distress.

- Statutory damages: Some intellectual property laws allow statutory damages in addition to actual damages.

- Injunctive relief: A court order requiring Google to stop using the voice or change it.

- Accounting of profits: Requiring Google to account for and return profits made from using the voice.

Google would certainly appeal any unfavorable ruling, and the case might end up in appellate courts where higher stakes precedent gets set.

Legislative Solutions: What Laws Might Be Coming

Even if Greene wins, it won't solve the broader problem. A single lawsuit against Google won't prevent other companies from creating voice synthesis models based on celebrities or voice professionals. What's needed is legislation that clearly addresses voice rights in the AI era.

Proposed Legislation and Industry Calls

Various groups are calling for new legislation. Voice actors, unions, and advocacy groups want laws that would:

- Require explicit consent before creating voice synthesis models based on someone's voice

- Require disclosure when AI-generated voices are being used

- Establish clear penalties for unauthorized voice synthesis

- Create a licensing framework for consensual voice synthesis

- Protect voice data from being used in training data without consent

Some states and countries are already exploring these rules. The European Union's AI Act includes provisions about voice synthesis and biometric data. Several U.S. states are considering voice protection laws.

The Consent and Transparency Framework

Most proposed legislation centers on two principles: consent and transparency. The consent principle says you should have to get explicit permission before using someone's voice for synthesis. The transparency principle says if you use an AI voice, you need to disclose that fact.

These principles make sense, but they're also challenging to implement at scale. How do you verify consent in an era when voice data is abundant and transferable? How do you ensure transparency when AI voices are embedded in products?

The International Dimension

Voice protection laws also have international implications. If the U.S. passes strict voice protection laws but the EU passes even stricter ones, companies will have to navigate multiple regulatory regimes. This could slow innovation but also create stronger protections for voice rights globally.

Estimated earnings show the high commercial value of distinctive voices, which AI voice cloning threatens to devalue.

The Celebrity Effect: Why This Case Matters

One reason the Greene lawsuit is significant is that it involves a celebrity with resources to pursue legal action. David Greene is a well-known figure with access to legal teams and media attention. Not everyone in this situation has these advantages.

The Access to Justice Problem

Most voice professionals, even successful ones, don't have the resources to sue Google. A lawsuit against a major tech company is expensive and time-consuming. It requires expert witnesses, months or years of litigation, and the ability to absorb potential losses.

Greene has these resources because he's a prominent NPR personality. But what about the voice actor who was unknowingly used as reference material? What about the podcaster whose voice was accidentally included in training data? They might have the same legal claims as Greene but lack the resources to pursue them.

This creates a system where only celebrities can actually enforce voice rights. That's a problem because it means the law exists in theory but not in practice for most people.

The Media Attention Factor

Greene's lawsuit also benefits from media attention. Major news outlets are covering the case. People are talking about it. This creates pressure on Google that wouldn't exist for a lesser-known plaintiff.

But this also means the precedent from this case, if it sets one, might be limited. Judges sometimes rule narrowly for celebrity plaintiffs, trying to protect their rights without creating broader implications. A court might decide in Greene's favor while still leaving unclear what the general rules are for voice protection.

Practical Implications for Content Creators and Podcasters

If you're a podcaster, voice professional, or media personality, the Greene lawsuit has immediate practical implications.

Protecting Your Voice

First, document your distinctive voice. Record samples of yourself speaking naturally. Have people testify that your voice is distinctive. Build a record that proves you have a recognizable vocal identity. This documentation could be valuable if you ever need to prove voice infringement.

Second, think about the commercialization of your voice. If your voice is valuable, protect that value. Don't license your voice to companies for synthesis without explicit contracts specifying how your voice will be used. Don't consent to having your voice included in training data without understanding what that means.

Third, monitor how your voice is being used. Search for clips of your voice online. Use voice recognition tools to see if your voice appears in unexpected places. Be alert to the possibility that your voice might be used without permission.

Contractual Protections

If you're a voice professional or you're considering voice synthesis work, insist on contractual protections. Your contract should specify:

- Exactly what your voice will be used for

- Where it won't be used

- How long the usage rights extend

- What compensation you'll receive

- Whether you retain any rights or control over how your voice is used

Standard voice acting contracts weren't designed for the AI era. They often don't address synthesis, retraining on new data, or other modern uses. You need to negotiate specific protections.

Building a Distinctive Voice

Paradoxically, building an even more distinctive voice can be a form of protection. The more unique and recognizable your voice is, the easier it is to prove infringement. A distinctive voice is more likely to be protected by law than a generic one. So if you're building a career as a voice professional, lean into your distinctive qualities.

The Artificial Intelligence Development Community's Perspective

While celebrities and voice professionals worry about voice rights, the AI development community has a different perspective. They see voice synthesis as a frontier technology with enormous potential benefits that could be stifled by overregulation.

The Innovation Argument

AI researchers point out that voice synthesis technology enables incredible applications. Accessibility tools for people with speech disabilities. Personalized education. Customer service applications. Emotional support chatbots that are more engaging because they can speak in a natural voice.

They worry that strict voice protection laws could slow innovation by making it difficult to train voice synthesis models. If companies can't use any voice data without explicit consent, how do they build models robust enough to work for diverse speakers?

This is a genuine tension. Protecting people's voice rights and enabling beneficial AI innovation are both legitimate goals, but they can conflict.

The Fair Use and Training Data Argument

Some in the AI community argue that using publicly available voice data for AI training falls under fair use. Fair use is a legal doctrine that allows limited use of copyrighted material for purposes like research, education, and commentary. If voice synthesis training falls under fair use, then companies might have the right to train on any publicly available voice data without consent.

But courts haven't definitively ruled on whether AI training falls under fair use, and it's probably not universal. Using someone's voice in a commercial product is different from using it for research.

The Transparency and Consent Middle Ground

Many thoughtful voices in the AI community actually agree that some protections are needed, but they prefer solutions that enable innovation while protecting people. Their preferred approach is transparency and consent:

- Disclose when voices are AI-generated

- Get consent when possible, but allow exceptions for legitimate research

- Provide ways for people to opt out of having their voice used in training data

- Create legal frameworks that are clear enough for companies to comply with

This middle ground approach is probably where legislation will eventually land. Not a ban on voice synthesis, but clear rules about consent, transparency, and permitted uses.

This chart compares consumer voice cloning tools based on accessibility, restrictions, and effectiveness. ElevenLabs and VALL-E are among the top performers in effectiveness, while restrictions vary significantly. (Estimated data)

Timeline and Current Status of the Greene Lawsuit

As of early 2025, the Greene lawsuit is in early stages. Here's what we know about the legal process ahead:

Initial Filings and Responses

Greene's legal team has filed initial complaints. Google will respond with their defense, likely repeating their claim that the voice came from a professional actor. The legal teams will exchange discovery documents, where both sides provide evidence to each other.

Expert Testimony and Voice Analysis

One of the most important parts of this case will be expert testimony about the voices. Voice forensics experts will likely be hired to analyze the Notebook LM voice and Greene's voice, comparing acoustic characteristics. These experts can identify whether there are unusual similarities that go beyond coincidence.

This technical analysis will be crucial. If experts can identify specific characteristics that are unusual to find together in accidental similarity, that strengthens Greene's case. If experts testify that the similarities could easily occur randomly, that helps Google.

Timeline Expectations

Civil cases in federal court typically take 2-3 years from filing to trial, sometimes longer. Discovery alone can take a year. There will be motions, depositions, and opportunities for settlement. Google will likely file motions to dismiss the case before it ever reaches trial, arguing that the claims don't state a legal cause of action.

So realistic expectations are that this case will take years to fully resolve. If either side appeals an unfavorable ruling, it could take even longer.

Global Perspective: Voice Rights Around the World

The Greene lawsuit is primarily a U.S. legal issue, but voice rights are being debated globally. Different countries are taking different approaches.

European Approach: Stricter Protections

Europe has generally been more protective of individual rights in the face of AI. The GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation) already provides some voice protections under biometric data rules. The AI Act includes specific provisions about voice synthesis and requires disclosure when AI-generated voices are used.

European courts might be more sympathetic to voice rights claims than U.S. courts. This could create an interesting situation where voice rights are stronger in Europe than in the U.S.

Asian Markets: Innovation First

Many Asian countries, particularly China and Japan, are prioritizing AI innovation over privacy concerns. Voice synthesis is flourishing in these markets with minimal regulation. This could create a situation where voice synthesis technology advances rapidly in Asia while being more restricted in Western countries.

The International Standard Problem

This creates a complex situation where different regions have different rules. A company might need to obtain consent for voice synthesis in Europe but not in Asia. This fragmentation makes it harder to develop global products and standards.

The Future of Voice Rights in the AI Era

The Greene lawsuit will set precedent, but the broader future of voice rights will depend on how courts interpret existing laws, how legislatures respond with new laws, and how the technology continues to evolve.

Possible Outcomes and Implications

If Greene wins decisively: It will establish that distinctive voices are protected intellectual property that can't be used without consent. Other companies will have to obtain explicit consent before creating voices based on specific people. This will slow some innovation but provide strong protection for voice rights.

If Google wins: It will suggest that voice synthesis based on reference material is legal as long as the company didn't directly copy the person's voice. This would give companies more freedom to create synthetic voices but could lead to more legal challenges using different legal theories.

If there's a settlement: The terms might remain confidential, leaving the legal questions unresolved. This often happens in high-profile cases, but it's unsatisfying from a precedent perspective.

The Longer-Term Trajectory

Regardless of this specific case, the longer-term trajectory is probably toward stronger voice protections. As voice synthesis technology becomes more accurate and more widespread, pressure will grow for legal protection. People will increasingly encounter situations where their voice is used without permission, and that will drive demand for legal remedies.

Technology companies, for their part, will probably eventually welcome clearer rules. Uncertainty is expensive. If companies knew exactly what they could and couldn't do with voice data, they could plan accordingly. Current ambiguity actually hurts innovation because companies have to be overly cautious.

Key Lessons from the Greene Lawsuit

Beyond the specific legal questions, the Greene lawsuit teaches some broader lessons about AI development, rights, and technology accountability.

Lesson 1: Distinctive Identity Is Valuable

Greene spent decades building a distinctive voice. That voice has real commercial and personal value. This case affirms that distinctive identity assets deserve protection.

Lesson 2: Reputational Risk Matters More Than Legal Risk

Open AI removed the Scarlett Johansson voice not because they definitely did something illegal, but because the controversy was damaging their reputation. Companies respond to reputational pressure even when legal liability is unclear.

Lesson 3: Transparency Is Cheaper Than Controversy

Google's relative silence about how the Notebook LM voice was created invited suspicion. A more transparent explanation might have defused some concerns. In the future, companies would be better served by proactively explaining how they created controversial products.

Lesson 4: Legal Frameworks Lag Behind Technology

The Greene lawsuit exists precisely because the legal framework hasn't caught up with AI voice technology. Courts are trying to apply laws written for different contexts to situations the laws never contemplated. This gap between law and technology is a recurring problem in AI regulation.

Lesson 5: Early Precedent Shapes Everything

How this case is decided will shape the entire industry. The first major voice rights case sets the template for all the cases that follow. That's why both Greene and Google are probably thinking about broader implications, not just their own dispute.

Industry Impact and Company Response

The Greene lawsuit is already having impacts beyond the specific case. Companies working on voice synthesis are taking notice and adjusting their practices.

Increased Caution on Voice Synthesis

Some companies that were planning to release voice synthesis features are becoming more cautious. They're adding more explicit disclosures that voices are AI-generated. They're being more selective about whose voice characteristics they're trying to replicate. Some are pausing voice synthesis products entirely until the legal landscape is clearer.

Insurance and Legal Preventive Measures

Companies are also adding legal safeguards. Enhanced insurance coverage for voice-related lawsuits. More careful documentation of how voice models were created. Explicit statements that their synthetic voices came from professional actors or that they're entirely original creations.

Public Advocacy and Messaging

Tech companies are also engaging in public advocacy about voice synthesis. They're arguing for the importance of the technology for accessibility and other beneficial uses. They're calling for balanced regulations that protect people without unnecessarily restricting innovation.

FAQ

What is the David Greene Notebook LM lawsuit about?

David Greene, the longtime host of NPR's "Morning Edition," is suing Google because he believes the male podcast voice in the company's Notebook LM tool was created based on his distinctive vocal characteristics, including his cadence, intonation, and use of filler words. Greene claims Google replicated his voice without permission, while Google maintains they used a professional actor. The lawsuit raises fundamental questions about voice rights and AI voice synthesis in the modern era.

How does Notebook LM's Audio Overviews feature work?

Notebook LM uses artificial intelligence to transform written documents into podcast-style conversations between two AI hosts. When a user uploads a document, the AI analyzes the content, generates a script, and then synthesizes speech using voice models to create natural-sounding podcast episodes. The technology includes personalized voice synthesis, which means the AI generates voices with personality, inflection, and distinctive characteristics rather than generic robotic speech.

What is the Scarlett Johansson precedent?

In 2023, actress Scarlett Johansson complained that a Chat GPT voice option called "Sky" closely resembled her own voice, particularly her distinctive warmth and intimate tone. She had previously declined when Open AI approached her about licensing her voice. After Johansson's complaint went public, Open AI removed the Sky voice from Chat GPT without ever formally admitting wrongdoing or providing detailed explanation of how the voice was created. This case established that public pressure and reputational concerns can move tech companies faster than legal threats.

What legal frameworks protect voice rights in the U.S.?

Voice rights in the United States are primarily protected through the "right of publicity," which is a state-level right that protects against unauthorized commercial use of someone's distinctive identity characteristics, including voice. However, this right varies significantly by state, with some states like California offering strong protections and others offering minimal protection. Copyright can also protect voice recordings, but it doesn't protect the style or characteristics of a voice. The existing legal framework was not designed for AI voice synthesis and leaves significant gaps in protection.

Can voice be trademarked or copyrighted?

Voice cannot be directly trademarked in the traditional sense, but distinctive voices can receive protection under trademark law if they function as source identifiers for specific goods or services. Voice recordings can be copyrighted, meaning companies can't copy the actual recordings without permission. However, creating a new synthetic voice that mimics someone's distinctive vocal characteristics but doesn't copy the actual recordings is a gray area where current copyright law provides minimal protection.

How can content creators protect their distinctive voices?

Content creators should document their distinctive voice characteristics by recording professional samples and gathering testimony that their voice is recognizable and distinctive. They should carefully negotiate contracts for any voice synthesis work, specifying exactly how their voice will be used and preventing unauthorized retraining or modification. Content creators should monitor the internet for unauthorized uses of their voice and consider using voice recognition tools to detect when their voice appears in unexpected contexts. Building an even more distinctive vocal style provides stronger legal protection because distinctiveness is a key factor courts consider.

What are the implications of this lawsuit for AI companies?

The Greene lawsuit sends a clear signal to AI companies that using distinctive voices without permission carries legal risk. Companies are responding by becoming more cautious about voice synthesis features, adding more explicit disclosures that voices are AI-generated, being more selective about whose voice characteristics they attempt to replicate, and investing in better documentation of how they created voice models. The uncertainty about the legal landscape is driving some companies to pause voice synthesis products until clearer rules emerge.

What legislation might be coming for voice protection?

Various groups are calling for legislation that would require explicit consent before creating voice synthesis models, mandate disclosure when AI-generated voices are used, establish clear penalties for unauthorized voice synthesis, create licensing frameworks for consensual voice synthesis, and protect voice data from being used in training data without consent. The European Union's AI Act already includes provisions addressing voice synthesis, while several U.S. states are considering voice protection laws. Most proposed legislation centers on two principles: consent and transparency.

Could voice cloning lead to fraud or crime?

Yes, voice cloning technology is already being used for malicious purposes. Criminals use voice synthesis to impersonate people in phone calls and commit fraud. Police have reported cases where voice cloning was used to impersonate officials or in other fraudulent schemes. The democratization of voice cloning technology makes this risk increasing. These criminal uses of voice synthesis add urgency to the need for clearer legal protections and regulations.

What's the difference between voice synthesis and deepfake audio?

Voice synthesis is the technology of generating speech that sounds like a particular person using AI models. It's neither inherently good nor bad. Deepfake audio specifically refers to synthesized speech created to deceive or mislead people into believing someone said something they didn't actually say. All deepfakes use voice synthesis technology, but not all voice synthesis creates deepfakes. Legitimate uses of voice synthesis include accessibility tools, entertainment, and education.

How long will the Greene lawsuit take to resolve?

Civil lawsuits against major companies typically take 2-3 years from filing to trial, sometimes longer when discovery is extensive. The Greene case will go through initial filings, responses, discovery where evidence is exchanged, expert testimony about voice analysis, and likely multiple motions before reaching trial. If either side appeals an unfavorable ruling, the case could extend several more years. Realistically, a final resolution is probably years away.

Conclusion: The Voice Rights Revolution Is Here

The David Greene lawsuit against Google over the Notebook LM voice isn't just a legal dispute between one person and one company. It's a watershed moment that signals the beginning of a broader reckoning with how AI technology intersects with identity, rights, and commercial value.

For decades, voice professionals assumed their voices were their own property. They could monetize them, control how they were used, and prevent unauthorized use. That assumption seemed reasonable because voice imitation required actual talent. You needed a skilled impressionist. You needed intent. You needed effort.

AI changed everything. Now voice imitation is just a matter of data and computing power. Anyone with access to voice synthesis tools can create a voice that sounds like someone else. Companies can train on publicly available data and generate synthetic versions of celebrities. The friction that once protected voice rights has disappeared.

Greene's lawsuit is the legal system's first serious attempt to restore that protection. Will he win? That depends on how courts interpret existing law, what new legislation gets passed, and how the technology continues to evolve. But regardless of this specific case's outcome, the trajectory is clear. People will increasingly demand protection for voice rights, and the law will eventually catch up.

What makes this moment important is that we still have time to shape how voice rights develop. We can create legal frameworks that protect people without unnecessarily restricting beneficial AI applications. We can develop technologies that include consent mechanisms and transparency protections. We can build an AI voice synthesis ecosystem that respects rights while enabling innovation.

But that requires thinking beyond just this lawsuit. It requires asking hard questions about what rights people should have over their distinctive voices, how companies should source and use voice data, what transparency means in an AI-driven world, and how to balance innovation with protection.

The Greene lawsuit is just the opening move in a much longer game. How the industry and the legal system respond will shape voice rights for the next decade. Everyone involved in voice work, everyone building voice synthesis technology, and everyone affected by the growing sophistication of AI voices should be paying close attention.

Because the stakes are higher than just one person's voice. They're about whether individuals can maintain control over their identity and reputation in an age of AI. They're about whether technology companies will be held accountable for their tools and practices. They're about whether the law can evolve fast enough to protect rights in a rapidly changing technological landscape.

Those are the real questions the Greene lawsuit forces us to confront. And they're questions that won't be resolved in a courtroom alone.

Key Takeaways

- David Greene's lawsuit against Google over NotebookLM voice establishes whether distinctive voices are protected intellectual property in the AI era

- The case follows Scarlett Johansson's successful pressure on OpenAI to remove the 'Sky' ChatGPT voice, setting precedent for reputational accountability

- Current legal frameworks (right of publicity, copyright, trade dress) were not designed for AI voice synthesis and leave significant gaps in protection

- Voice synthesis technology has become so accessible that anyone can now clone voices from just seconds of audio without consent or knowledge

- The outcome will likely reshape how tech companies source voice data and what legal protections voice professionals and celebrities receive

Related Articles

- Seedance 2.0 and Hollywood's AI Reckoning [2025]

- Seedance 2.0 Sparks Hollywood Copyright War: What's Really at Stake [2025]

- SAG-AFTRA vs Seedance 2.0: AI-Generated Deepfakes Spark Industry Crisis [2025]

- xAI's Mass Exodus: What Musk's Spin Can't Hide [2025]

- OpenAI Disbands Alignment Team: What It Means for AI Safety [2025]

- OpenAI Researcher Quits Over ChatGPT Ads, Warns of 'Facebook' Path [2025]

![David Greene Sues Google Over NotebookLM Voice: The AI Voice Cloning Crisis [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/david-greene-sues-google-over-notebooklm-voice-the-ai-voice-/image-1-1771195035913.jpg)