Introduction: The Perfect Storm in PC Memory

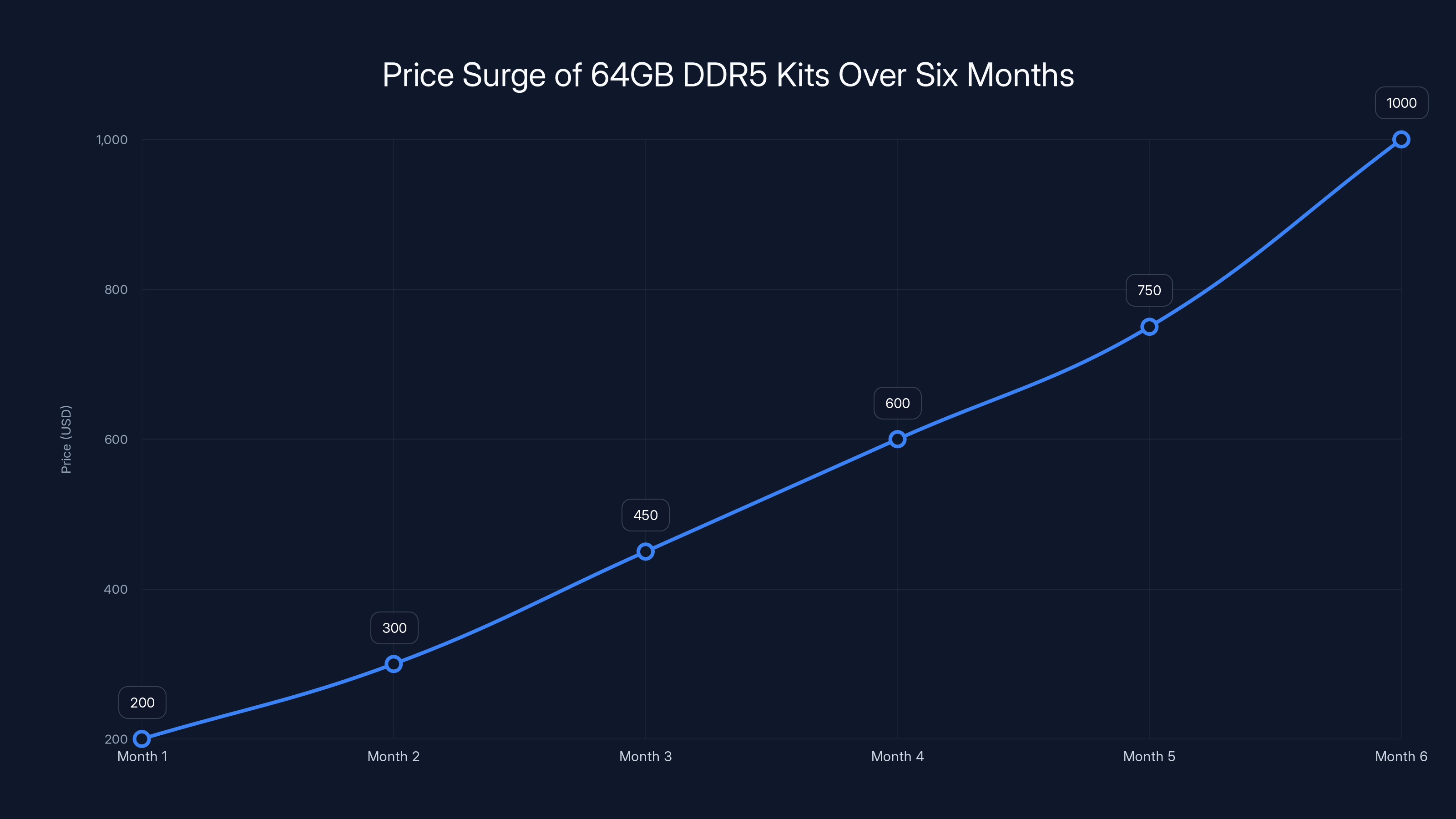

Let me paint a picture for you. Six months ago, building a solid PC with 64GB of DDR5 RAM was something you'd do without losing sleep over the budget. You'd spend maybe

This isn't just inflation. This isn't even normal market fluctuation. What we're witnessing is the fastest price escalation in PC component history, and it's forcing builders, gamers, and professionals to make genuinely difficult financial decisions about something that was once treated as commodity hardware.

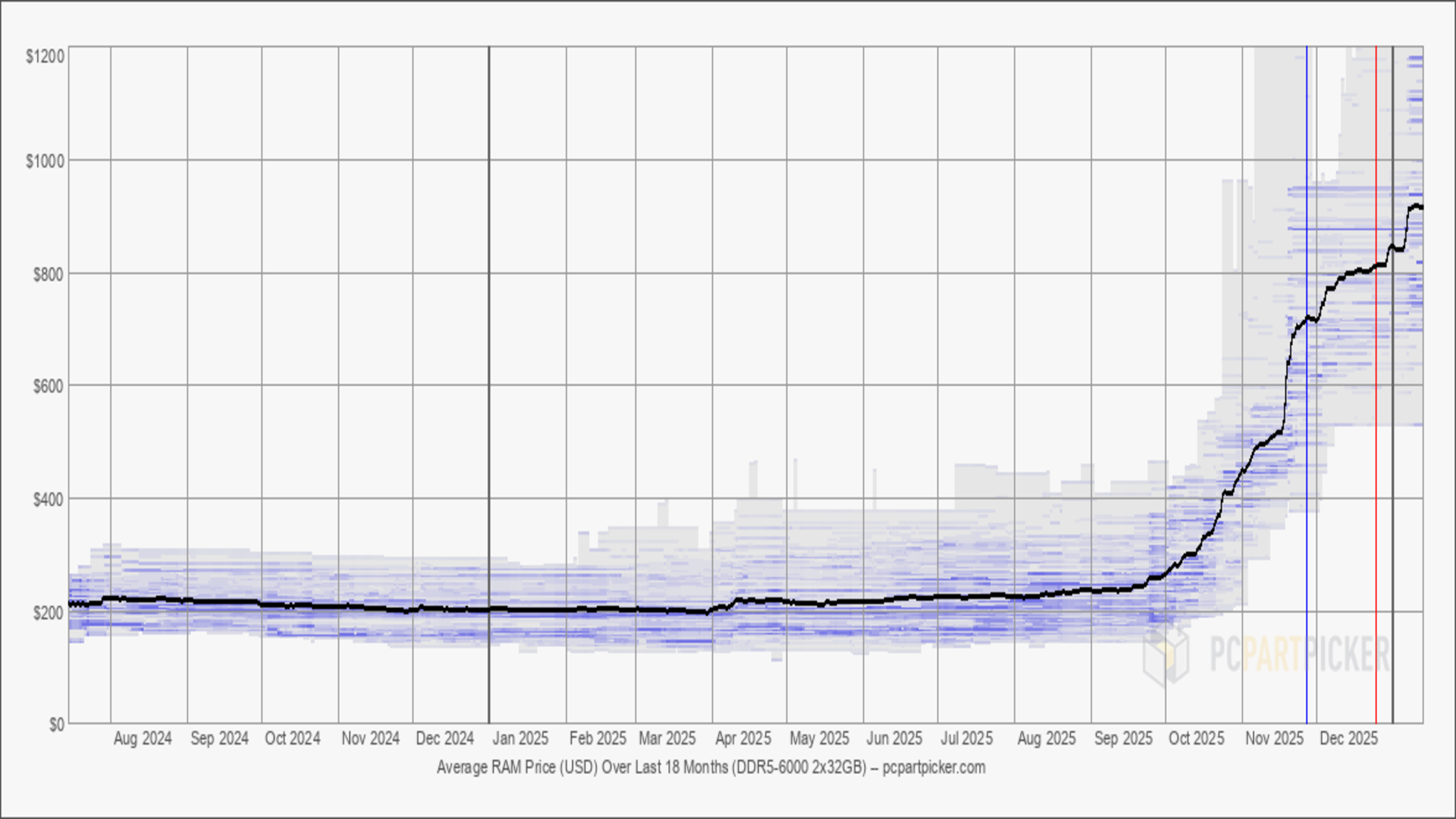

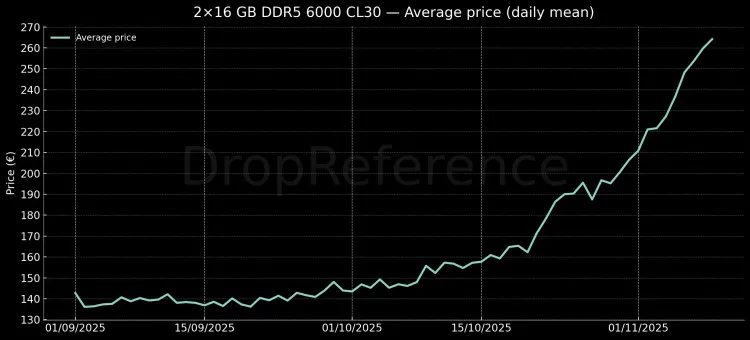

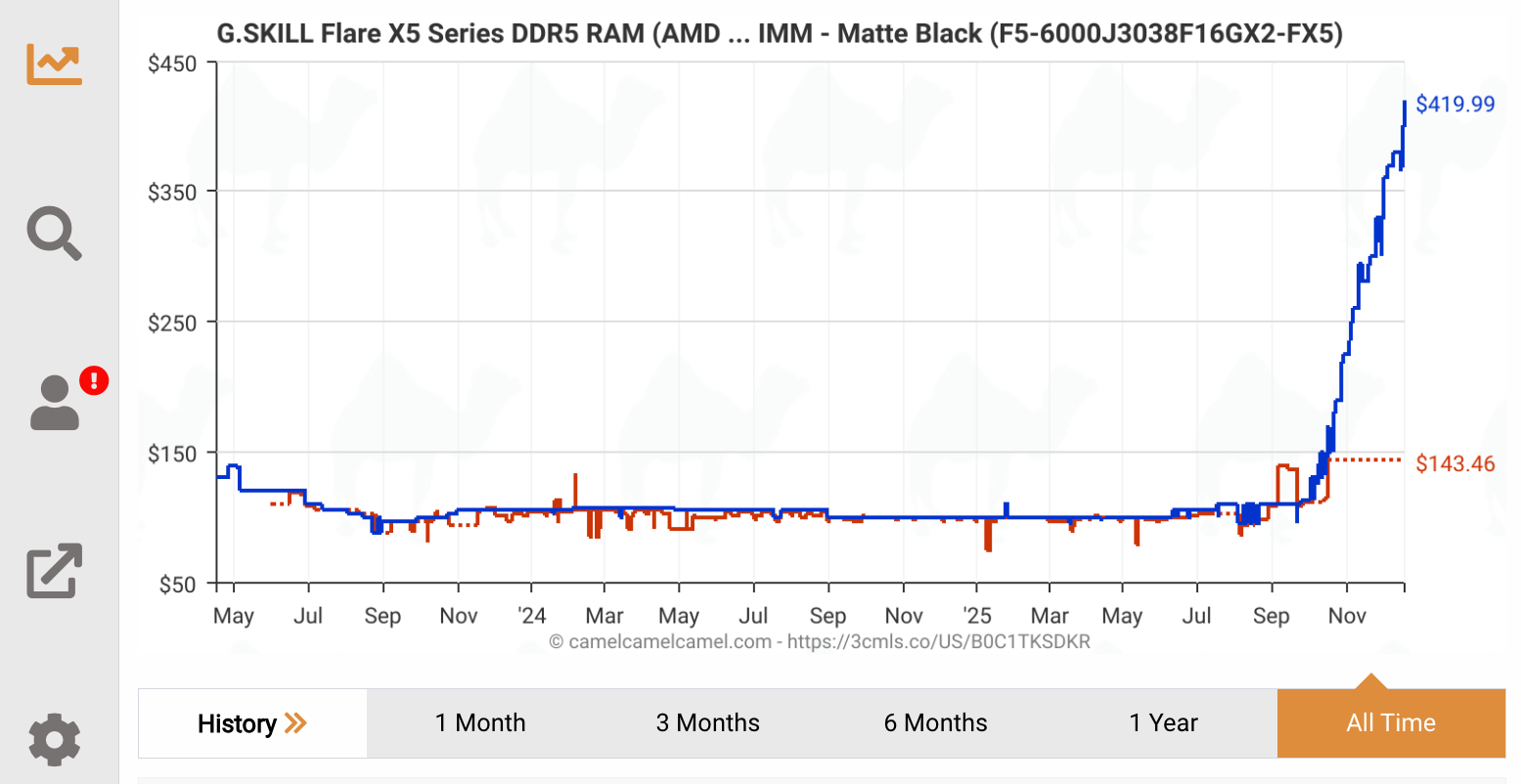

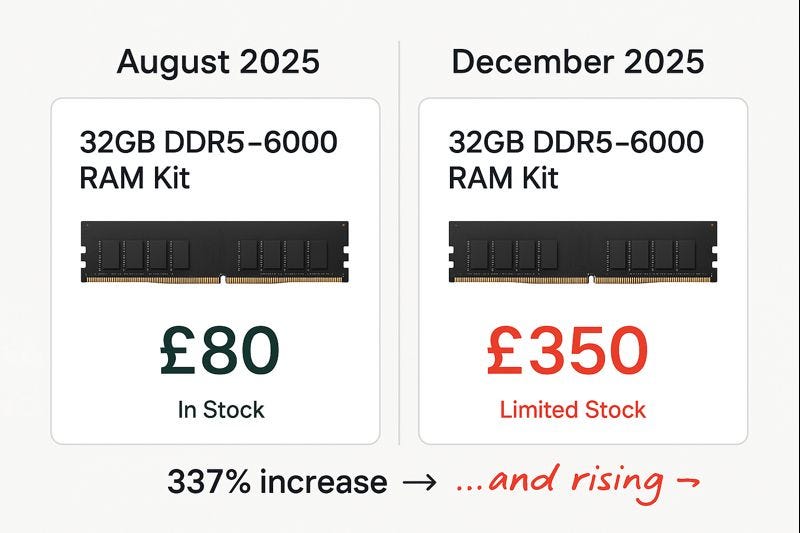

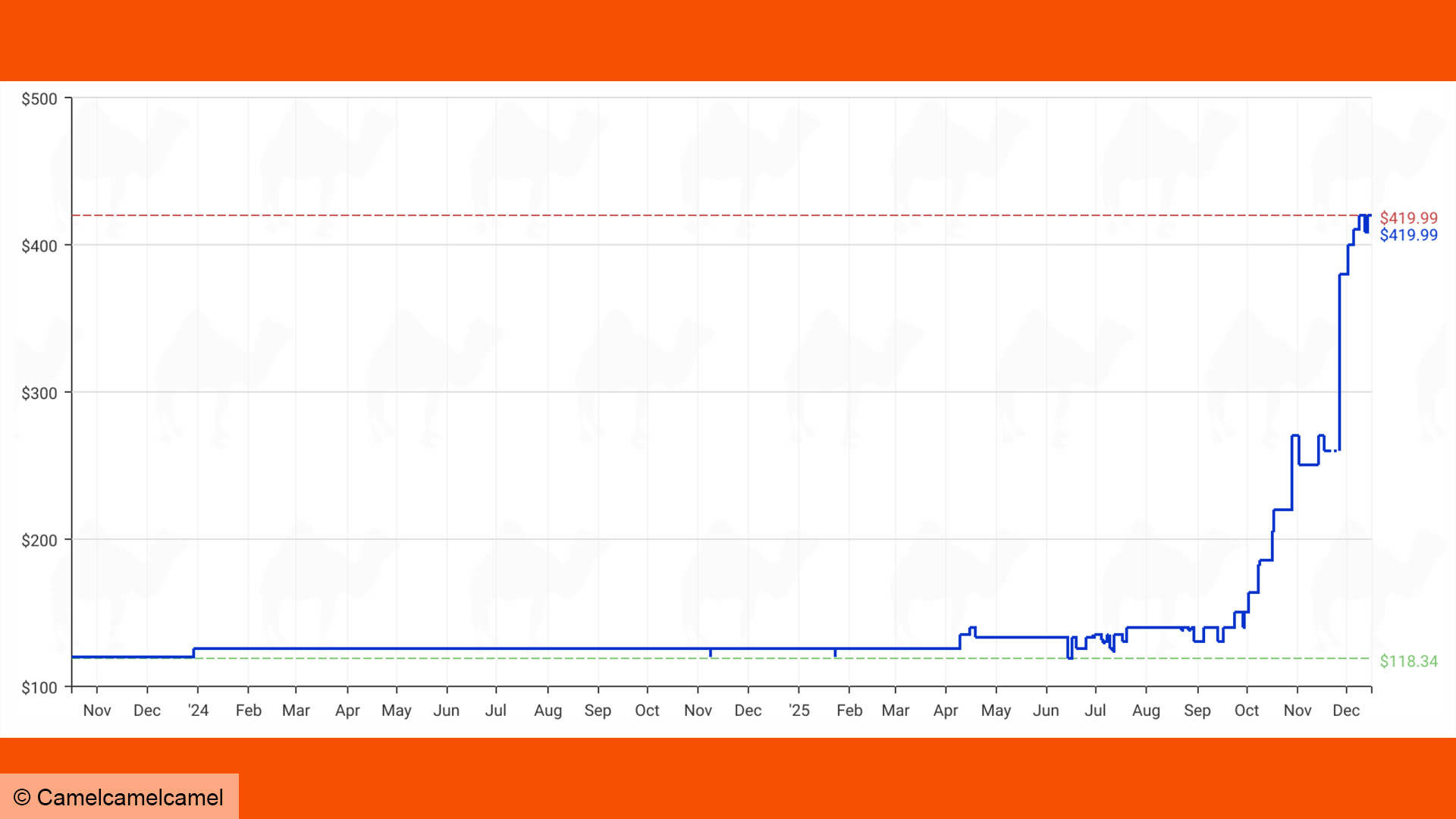

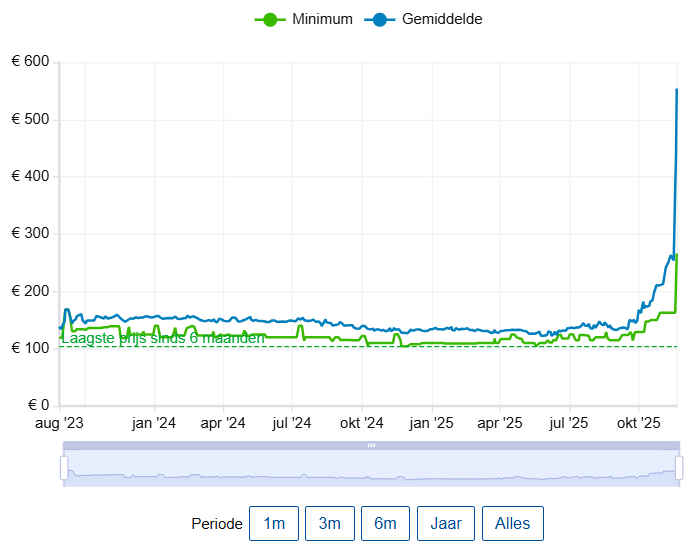

Here's what makes this crisis so jarring: in August 2025, a 64GB DDR5 kit sat comfortably under

The problem isn't that nobody saw this coming. The supply issues have been brewing for years. The problem is that everything converged at once: exploding AI demand, production constraints, memory transitions, and a supply chain that simply couldn't respond fast enough.

But here's what most coverage misses: the RAM crisis tells a much bigger story about how modern technology actually works. It reveals the fragility of supply chains. It shows how demand from one industry (AI) can weaponize prices against every other consumer. And it raises a genuinely uncomfortable question: what happens when critical hardware becomes luxury goods?

In this guide, we're diving deep into what caused the DDR5 disaster, who's actually getting hit hardest, and whether things will actually get better. Because the answer might surprise you.

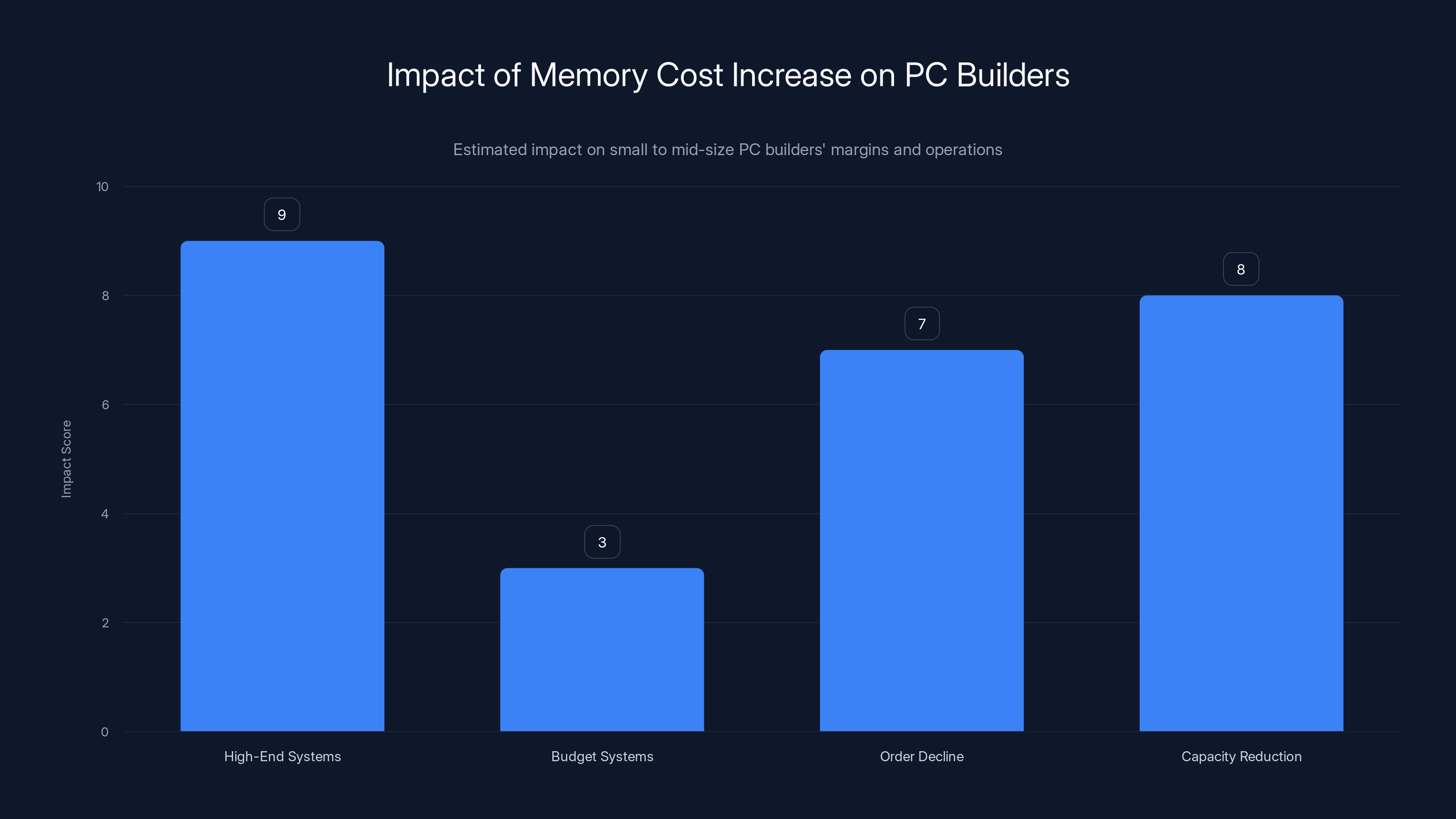

Small PC builders face significant challenges with high memory costs, leading to reduced margins and operational shifts. (Estimated data)

TL; DR

- 64GB DDR5 kits jumped from 1000+ in six months, with a 50% spike in the last month alone

- AI data center demand is the primary culprit, but DRAM production bottlenecks and older memory phase-outs made it catastrophic

- Consumer RAM is systematically deprioritized when supply tightens, leaving PC builders exposed

- Price stabilization won't happen soon, and the path back to "normal" pricing will take years

- Memory theft has become a real industry problem as module values skyrocket

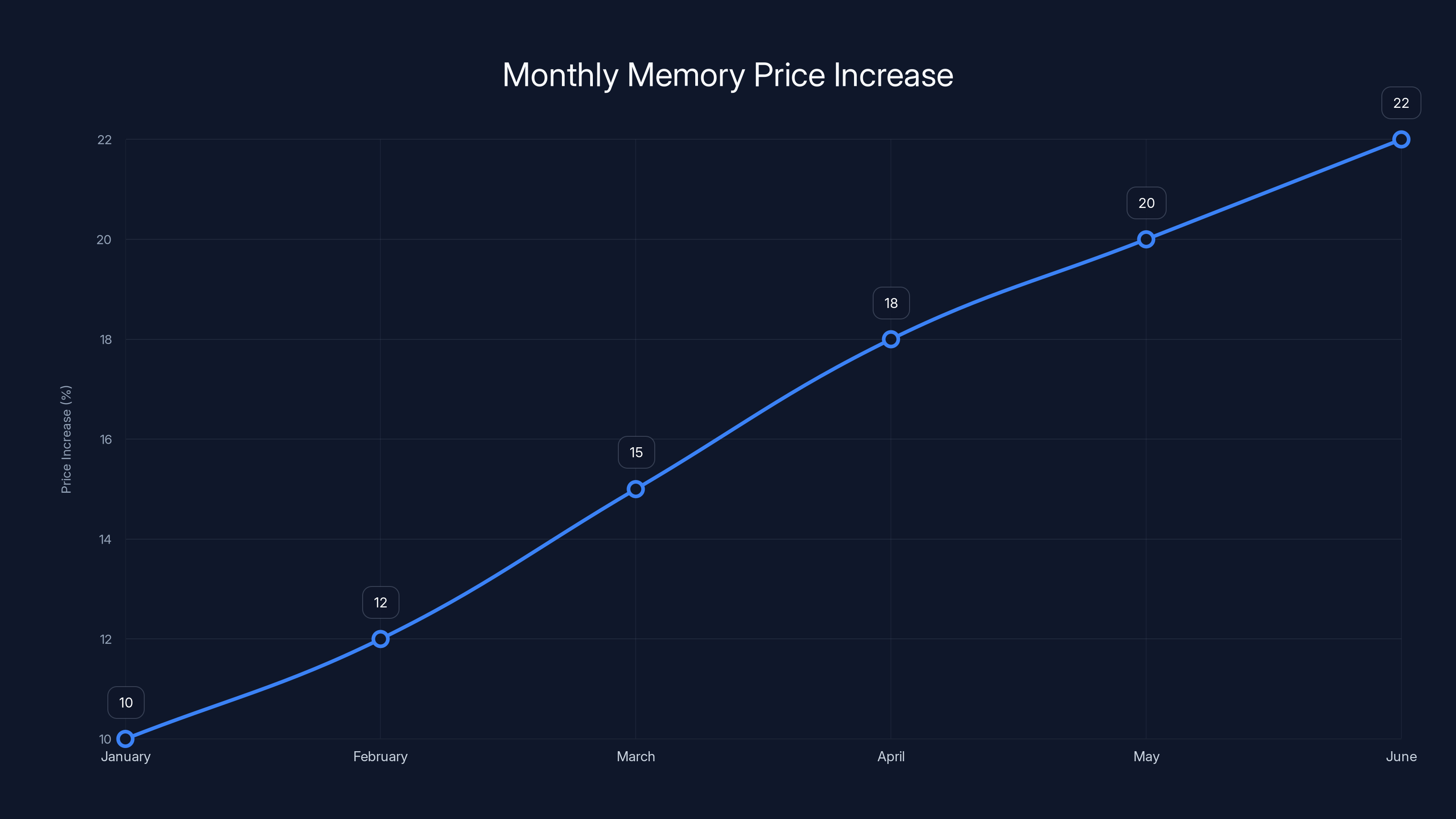

Memory prices are estimated to increase by 10-22% monthly due to panic buying and speculative hoarding. Estimated data.

How We Got Here: The Perfect Convergence

The AI Demand Explosion Nobody Planned For

Let's start with the obvious culprit: artificial intelligence. The rise of large language models and generative AI hasn't just transformed software. It's fundamentally warped hardware demand in ways the industry simply wasn't prepared for.

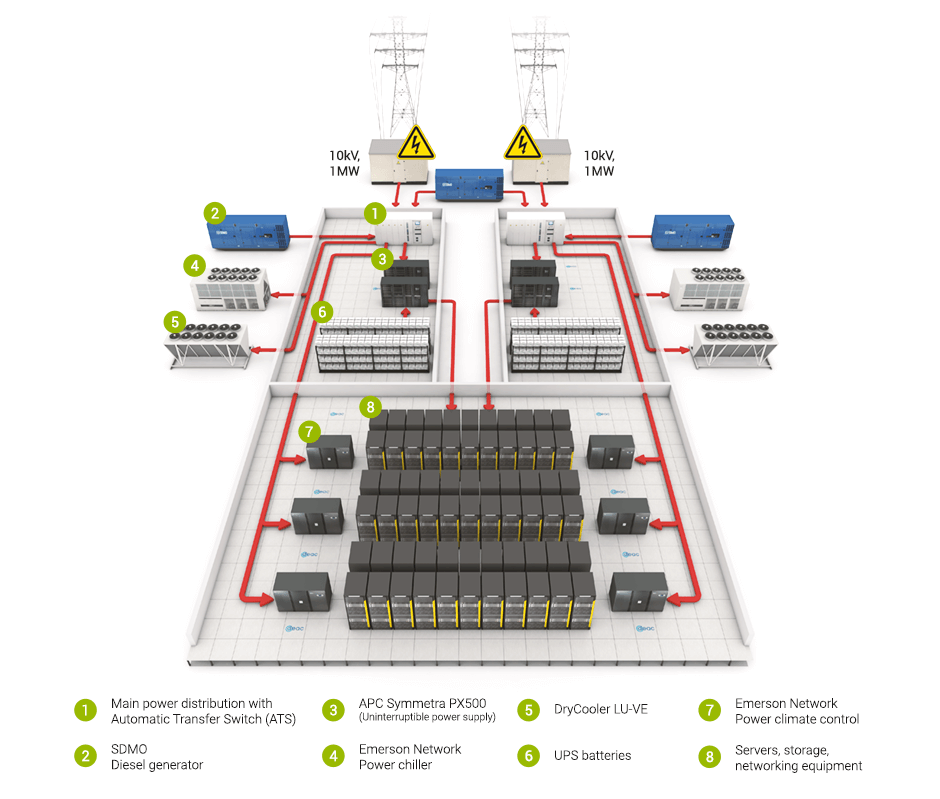

Data centers running models like those from leading AI companies need absolutely staggering amounts of DRAM. We're talking about systems that require tens of gigabytes just to load model parameters into memory. And when you're running thousands of these systems simultaneously, doing inference for millions of users, the memory requirements become genuinely incomprehensible to most people.

The problem is that this happened fast. Within 12-18 months, AI workloads went from "interesting niche" to "the dominant force shaping datacenter architecture." DRAM manufacturers couldn't have predicted this. Their production pipelines take months to ramp up. Their fabrication facilities are massively expensive. You don't just spin up new wafer plants because demand unexpectedly quintupled. The lag between recognizing the problem and actually solving it measured in quarters, not weeks.

Here's the thing that really matters: datacenter customers have different purchasing patterns than consumers. When a cloud provider needs memory, they don't call their local retailer. They contact DRAM manufacturers directly and negotiate bulk pricing. They have contracts. They have commitments. And critically, they have budgets that dwarf consumer purchases by orders of magnitude.

When you're a major cloud provider and memory is constraining your ability to deploy the most profitable product (AI), you don't just ask nicely. You order in massive volumes and ensure supply. Manufacturers, seeing these enormous contracts, naturally prioritize them. Consumer RAM? That gets whatever's left.

DRAM Production Constraints and the Transition Problem

But here's where the crisis gets worse: production capacity hasn't just failed to keep up with demand. It's actually shrinking in some ways.

Traditional DRAM manufacturing is expensive. Incredibly expensive. You need multi-billion dollar fabrication plants. You need expertise. You need quality control that borders on obsessive. There are only a handful of companies in the world that can do this: Samsung, SK Hynix, and Micron. That's it. Three companies control virtually all DRAM production globally.

This concentration means any supply disruption hits everyone hard. And right now, there are multiple disruptions happening simultaneously. Older DRAM technologies like DDR4 are being phased out. Manufacturers want to move everything to DDR5 because it's newer, higher margin, and commands better pricing. But that transition creates a squeeze where neither enough DDR4 nor enough DDR5 is being produced for all the demand.

Manufacturers face a genuine business choice: should they produce DDR4 for consumer PC builders at lower margins, or focus everything on DDR5 and higher-value products? The economics point in one direction, and consumers experience the consequences.

Production geometry is also becoming a constraint. Each generation of memory gets smaller, denser, and more complex to manufacture. Moving to smaller process nodes is harder. Yields are lower initially. It takes time to ramp. During ramp periods, production capacity is tight even if the plants are running at maximum capacity.

Supply Chain Fragility and Logistics Breakdown

There's another layer to this that doesn't get enough attention: the supply chain itself is fragile in ways that transcend simple supply and demand.

Global memory production is concentrated in Asia. Most of it gets distributed through a handful of logistics chains. When demand at the top (data centers) becomes urgent and massive, it crowds out everything else. Shipping gets redirected. Priority orders get fulfilled first. Standard consumer orders that used to get reliable 30-day lead times suddenly stretch to 60 or 90 days.

And here's where it gets really interesting: there's actually a cascading effect. When memory gets scarce, system integrators and retailers start hoarding. They place bigger orders than they normally would because they're afraid of running out. That hoarding, even if it's rational from an individual perspective, makes the shortage worse for everyone else. It's like the toilet paper panic from 2020, except it's happening in slow motion with industrial equipment.

The other problem is that smaller distributors and regional markets lose access faster. A major electronics chain in North America can negotiate directly with manufacturers. An independent PC builder supply shop can't. When supply tightens, the big players get allocation first. Everyone else gets whatever crumbs are left.

The Market Response: Why Prices Keep Climbing

Panic Buying and Speculative Hoarding

Prices don't just respond to supply and demand. They respond to expectations about supply and demand. And right now, expectations are absolutely dire.

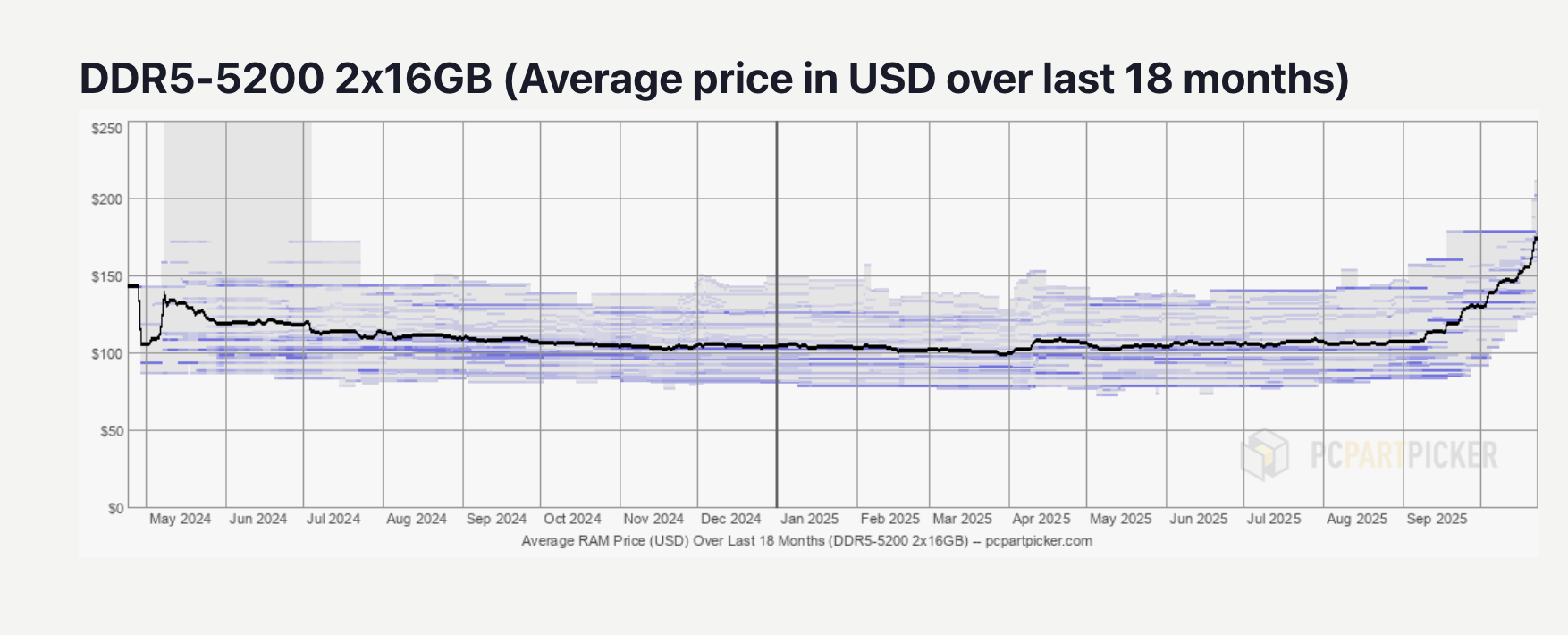

When PC builders and system integrators see memory prices rising 10-15% per month, they face a genuine decision: should I buy more now before prices climb further, or should I wait and hope for stabilization? For most of them, the rational choice is to buy now. If memory is a significant component of your cost structure, and you believe it's going to be 20% more expensive next month, you're going to load up today.

That buying, in turn, creates the scarcity that justifies the price increase. It's a feedback loop. And it's one that's genuinely difficult to break without either massive supply increases or some external shock that convinces buyers that prices have peaked.

We're already seeing this play out in the data. Order volumes have become volatile. Sometimes they spike as everyone tries to lock in current prices. Sometimes they collapse because buyers are waiting for a bottom that never comes. Retailers are playing this game too. They increase prices faster than their costs increase because they know the next shipment will cost more. They're buying low and selling high, which is rationally appropriate, but it amplifies the price moves in both directions.

Manufacturer Pricing Power

Here's something that's often overlooked: DRAM manufacturers aren't passive actors responding to constraints. They're active participants with enormous pricing power, and they're using it.

When supply is limited and demand is explosive, manufacturers have leverage. They can raise prices. And unlike consumer-facing companies that worry about price sensitivity and market share, DRAM manufacturers care about something different: maximizing revenue per unit of production capacity.

If you can only produce 100 units of memory this month, would you rather sell them at

Manufacturers have instituted minimum order quantities for many products. They've raised prices faster than simple supply-demand curves would predict. They've shifted production toward higher-margin products. These aren't mistakes or defensive measures. They're conscious business decisions to maximize profitability during a constrained period.

The reason manufacturers can do this is because they have limited direct competitors. If there were ten DRAM manufacturers competing aggressively, price wars would eventually bring prices down. But with only three major players, the competitive pressure is more muted. And when all three are facing the same supply constraints, they all have the same incentive to maintain high prices.

Regional Price Variations and Market Segmentation

One interesting dynamic that's emerged is that prices aren't uniform globally. Different regions are experiencing different levels of price pressure.

North America has generally seen higher price increases than Europe or Asia-Pacific regions. This is partly because North America's supply chains are more reliant on certain distribution channels that got squeezed harder. It's partly because US retailers have different purchasing patterns. And it's partly pure chance in how shipments get allocated.

For international buyers, this creates weird arbitrage opportunities. Savvy folks have been buying memory in cheaper regions and shipping it elsewhere. But that only works at small scales. For large volume buyers, they can't rely on random imports. They need reliable, contractual supply. And that supply is being rationed based on existing relationships and contract terms.

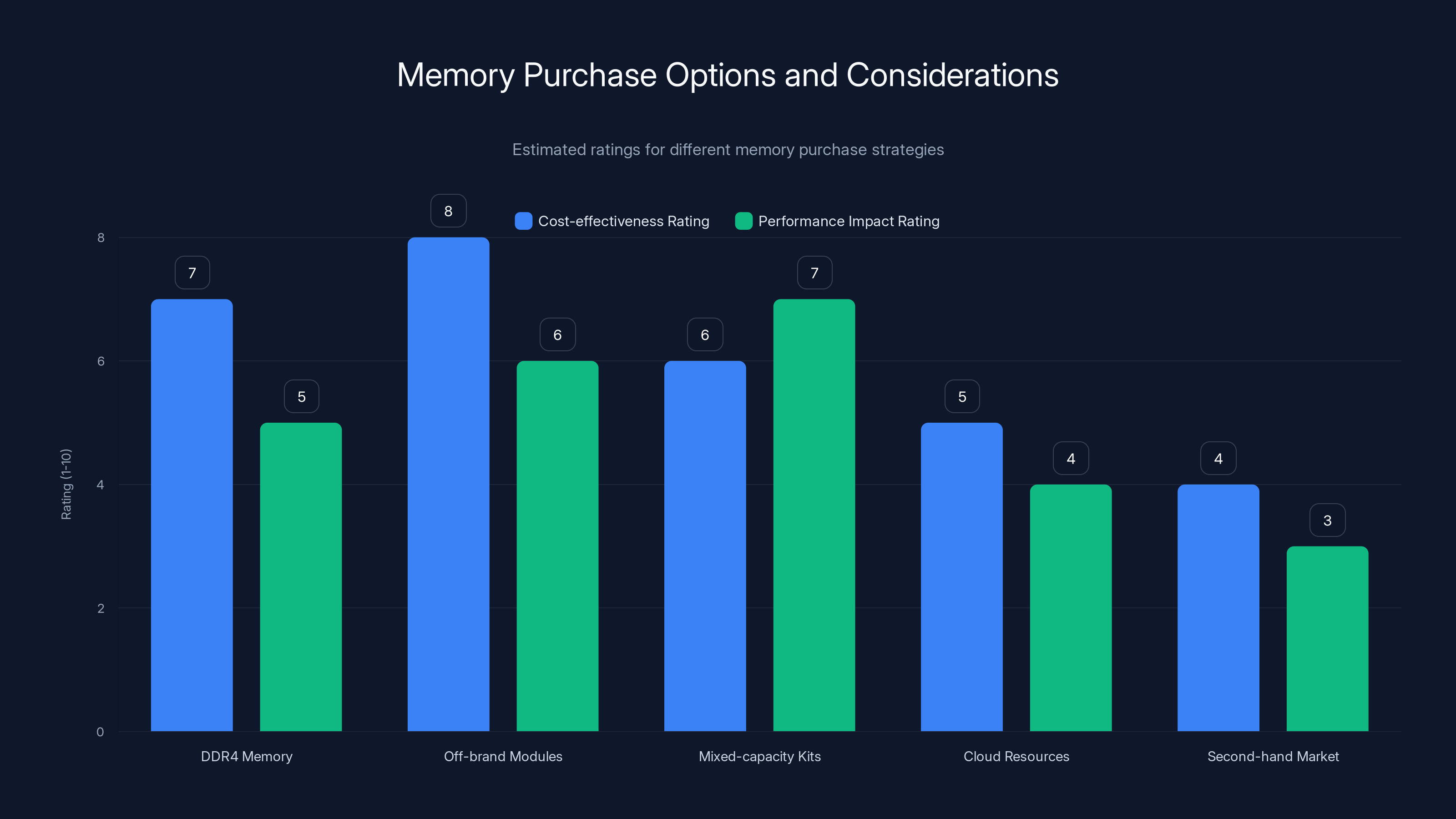

Estimated data shows off-brand modules as the most cost-effective, while mixed-capacity kits offer balanced performance and cost. Second-hand markets are risky but can be cheaper.

Who Gets Hit Hardest: The Collateral Damage

Small PC Builders and System Integrators

When supply tightens, the pain is distributed unequally. Large enterprises with established relationships with manufacturers and bulk buying power? They're fine. They have contracts that stipulate pricing. They can go to the front of the line. Small builders? They get crushed.

A small to mid-size system integrator that builds 50-100 custom PCs per month has a problem. Their margins on high-end systems are maybe 15-20%. If memory costs go from

Some of them have started declining orders for high-memory systems. Others have shifted their product mix away from gaming and professional workstations toward budget systems with lower memory requirements. A few have simply closed down or significantly reduced capacity. It's brutal but rational.

Gaming and Content Creation Markets

Gaming has been marginally affected. Most modern games don't require more than 32GB of RAM. You don't need to upgrade memory for gaming in most cases. The crisis hits harder in professional workloads where more memory is genuinely useful.

Content creation is different. Video editing, 3D rendering, AI-assisted image generation, and similar workloads absolutely benefit from more RAM. Creators who could have justified a 64GB upgrade at

The market for high-end consumer workstations has contracted noticeably. Some of that demand is shifting to Mac Studio systems with integrated memory (you can't upgrade those, so the pricing structure is different). Some of it's shifting to cloud services where memory costs are amortized across projects. Some of it's just going away as professionals decide that the marginal benefit of 64GB isn't worth the cost.

Data Scientists and Machine Learning Practitioners

Interestingly, AI researchers and machine learning practitioners are seeing this play out differently. Many professional ML workloads have already transitioned to cloud GPU services or specialized AI accelerators. They're not buying consumer-grade memory anyway. But freelancers, hobbyists, and small ML teams that want to run models locally are completely priced out. A setup that was viable for

Casual Upgrades Have Basically Stopped

The subtlest impact might be the most important: the casual PC upgrade market has essentially paused. There are people who would spend

PC manufacturers know this. They know that upgradeability is becoming less relevant for most consumers. This actually shifts incentives toward thinner, more integrated systems where you can't upgrade memory anyway. It's a vicious cycle where the market failure (high prices) drives product design changes that make the problem permanent.

Timeline: When Will Prices Actually Normalize?

The Optimistic Scenario

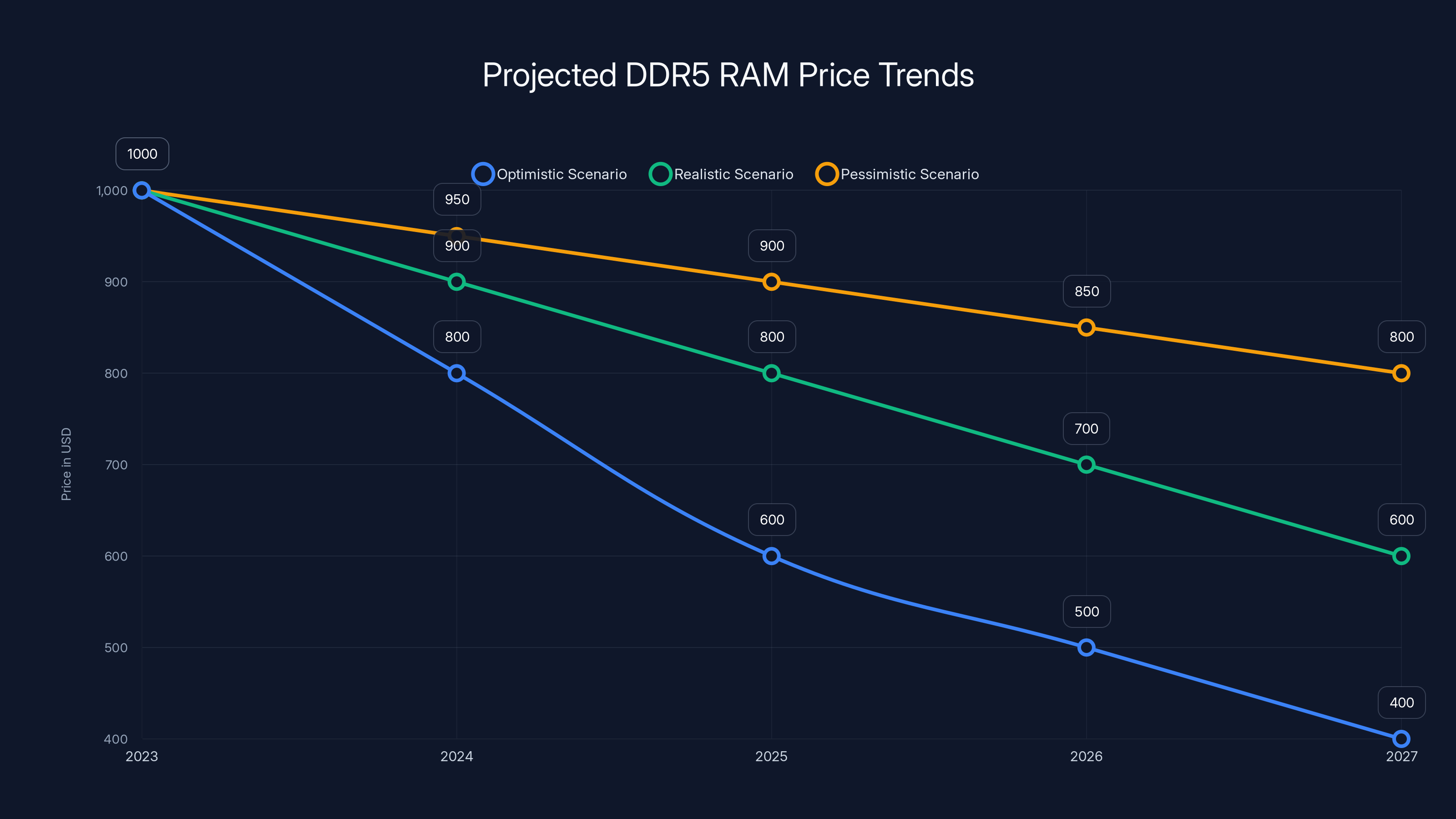

In the best case, here's how this resolves: by mid-2026, DRAM production ramps up enough that supply actually exceeds demand for the first time in 12 months. Manufacturers realize that prices have peaked and that they need to cut prices to stimulate demand and clear inventory. Within 3-4 months, prices start falling back toward historical norms.

For this to happen, two things need to occur: first, the AI data center demand growth needs to moderate (not disappear, but stop growing exponentially). Second, manufacturers need to successfully ramp new production capacity and improve yields.

If this happens, we might see 64GB kits back in the

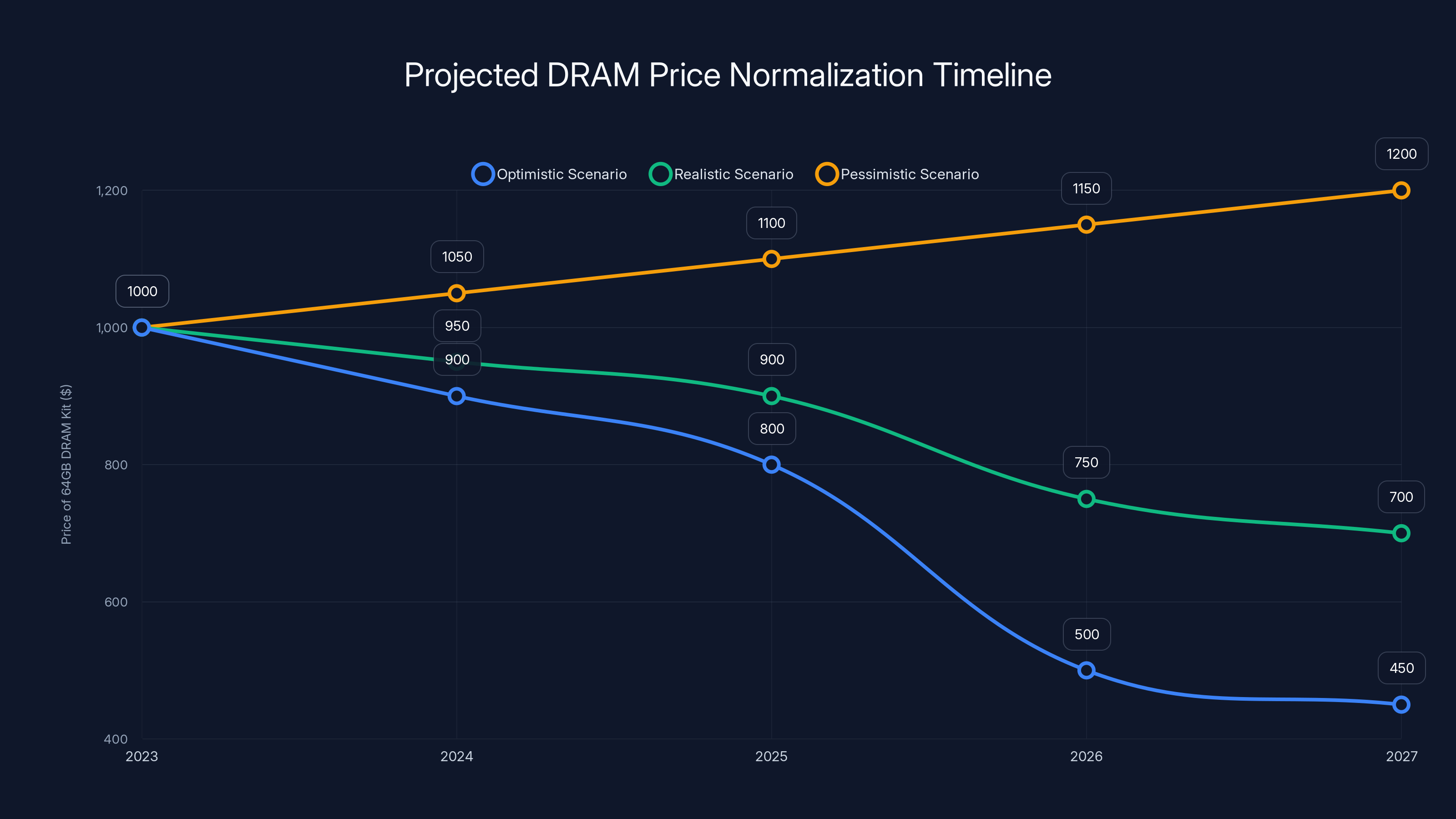

The Realistic Scenario

More likely is that prices stabilize at elevated levels for much longer. Manufacturers will keep production directed toward higher-margin professional and data center uses. Consumer DRAM will remain constrained. Prices might settle in the $600-800 range for 64GB kits and stay there through 2026. Maybe into 2027.

The reason is path dependence. Once DRAM manufacturing processes have been optimized for higher-margin products, and customer relationships have been established at those price points, there's no incentive to shift back to competing for the low-margin consumer segment. Manufacturers will produce enough consumer memory to keep the market functional but not so much that supply exceeds demand and prices have to fall.

This is actually profitable for manufacturers. A 64GB kit at

The Pessimistic Scenario

And then there's the scenario that keeps industry observers up at night: what if nothing solves this? What if AI demand continues growing, production constraints persist, and consumer memory becomes a perpetual luxury item?

In this case, prices could remain at current levels indefinitely, or even drift higher. Consumer PC upgrades become rarer. System integrators shift toward low-memory systems. The consumer PC market bifurcates: ultra-budget systems with 16GB, and ultra-premium systems for people who absolutely need more.

This has historical precedent. When specific components or materials become bottlenecks, they sometimes just stay expensive. There's no law of physics that says memory must ever come back down to $200 for 64GB. That price was what the market would bear when supply was abundant. It might never be abundant again.

DDR5 RAM prices are projected to stabilize between

What This Says About Modern Supply Chains

Concentration Risk Is Real

The DRAM crisis reveals something uncomfortable about modern technology: critical components are concentrated in the hands of a few manufacturers, on a few continents, with only a handful of major distribution channels.

In theory, you'd think there'd be competition to enter the DRAM market. The profit margins are excellent. The demand is constant. But the barrier to entry is astronomical. A competitive DRAM fab costs $10-20 billion to build. It takes 3-4 years to construct. It requires expertise that's concentrated in a handful of countries. And by the time you finish building it, the technology has moved forward and your fab might already be semi-obsolete.

This concentration means that supply disruptions aren't self-correcting through market mechanisms. A normal competitive market would see high prices trigger new entrants or expansion by existing players. In DRAM, high prices just trigger higher prices because there's nowhere else to buy from.

This is especially concerning because memory is becoming more critical to almost every computing workload. AI makes it worse, but it's a broader trend. If a bottleneck in one critical component can hold the entire industry hostage, that's a structural problem with no easy fix.

The Precedent for Future Crises

What happened with DDR5 memory will probably happen again with other critical components. As AI grows, it will create bottlenecks in other parts of the supply chain. GPUs are already getting tight. Advanced packaging and substrate capacity are constrained. Power delivery components are becoming scarce.

Each of these will play out similarly: demand spikes, supply can't respond quickly enough, prices spike, smaller customers get squeezed out, and the market doesn't normalize until something breaks. It's a pattern we're going to see repeat.

Lessons for Buyers and Builders

If you're building systems or planning component purchases in this environment, the lessons are brutal but clear: buy when you can, not when you need to. Treat high-demand components like they're going to get more expensive. Build more conservatively than you might normally, because upgrading later is going to hurt. And consider alternative architectures that don't rely on easily-bottlenecked components.

Alternative Solutions and Workarounds

Shifting to Cloud-Based Memory

For professional workloads that need significant memory, cloud computing is increasingly attractive. Instead of buying a system with 64GB of RAM, you can rent cloud compute with as much memory as you need, whenever you need it.

This isn't ideal for latency-sensitive workloads or applications that need persistent memory. But for batch processing, machine learning training, data analysis, and many other tasks, cloud is becoming cost-competitive even against locally-owned systems that would have been cheaper 6 months ago.

The dynamics are interesting here: cloud providers have the same access to DRAM that enterprise data centers do. They negotiate directly with manufacturers. So cloud pricing for memory-intensive workloads has gone up, but not as dramatically as retail prices. For some use cases, cloud is actually the cheaper option now.

Optimizing Software for Memory Efficiency

When hardware becomes expensive, software gets more efficient. Engineers who used to write casual memory-intensive code now optimize heavily. Databases get configured for lower memory footprints. Caching strategies get refined. It's not pleasant work, but it's economically rational.

For existing systems, software optimization is actually the best path forward. If you've got a system with 32GB that's hitting memory limits, sometimes clever software changes can reduce peak memory usage by 20-30%, which might be enough to avoid the upgrade entirely.

Hardware Alternatives

NVME SSDs have gotten dramatically faster and cheaper. For some workloads, using fast NVMe storage as a memory extension (via page filing or swap) becomes viable when it wasn't before. It's not as fast as real DRAM, but it's better than nothing if you're desperate.

Integrated graphics and purpose-built accelerators are also becoming more interesting. If you don't need all the flexibility of general-purpose compute, specialized hardware often requires less memory. An ASIC designed for a specific task might need 1/10th the memory of a general-purpose GPU, which makes it much cheaper to deploy at scale.

Projected DRAM prices vary significantly based on different scenarios. The optimistic scenario suggests prices could drop to

The Bigger Picture: What Memory Prices Tell Us About AI's True Cost

Hidden Infrastructure Costs

When everyone talks about AI being expensive, they're usually talking about GPU costs or cloud compute bills. But the infrastructure that supports AI is much broader. Memory is just one component of a much larger problem: AI requires enormous amounts of physical hardware, and that hardware is resource-constrained.

The DDR5 crisis is a visible manifestation of AI's hidden costs. Each large language model deployment requires not just computation but memory at scales that previous applications never needed. The infrastructure had to be built. The resources had to be sourced. And that created bottlenecks throughout the supply chain.

If memory costs can spike 300% in six months, what happens when processing power or bandwidth become bottlenecks? The answer is probably: the same thing. We'll see price spikes and supply shortages until capacity catches up.

Sustainability Questions

There's also an uncomfortable sustainability dimension to this. The DRAM factories that are ramping production to meet AI demand consume enormous amounts of energy and water. The new fabs being built will consume more. At some point, it's worth asking whether the infrastructure can actually support the scaling that AI requires.

It's not a near-term problem. But if every new AI advancement requires more memory, more compute, and more power than the previous generation, and if we're already seeing supply constraints, the trajectory is concerning.

Economic Concentration

The DRAM crisis also highlights a broader trend: more of the value and control in computing is concentrating in fewer hands. The companies that can buy memory directly from manufacturers and lock in favorable pricing are winning. Everyone else is paying retail prices that keep rising.

This tilts the playing field toward the largest players. Startups and smaller companies find it harder to compete because their hardware costs keep rising. This could actually slow down innovation if the landscape becomes more dominated by a few mega-platforms that have privileged access to constrained resources.

How to Navigate Memory Purchases Right Now

If You Absolutely Need Memory Now

You have some options, none of them great. First, check if you can actually wait. If your system works okay with 32GB or 48GB for a few more months, waiting is the best decision. Prices probably won't come down, but they might stabilize, and that's something.

If you can't wait, explore these alternatives in order: First, look at DDR4 memory. It's older, requires an older motherboard, but prices haven't spiked nearly as much because it's being phased out. If you can build around DDR4 now and upgrade to DDR5 in a year when prices have hopefully settled, that might make economic sense.

Second, consider off-brand or less popular memory modules. Popular brands like Corsair and G. Skill command premiums. Lesser-known manufacturers with good reviews are often significantly cheaper. The performance difference is negligible for most workloads.

Third, look at mixed-capacity kits. A 48GB kit (32GB + 16GB) might be cheaper than a matched 64GB kit, and it gives you flexibility. You can always add more RAM later when prices come down.

Fourth, if you're building a professional system, explore whether cloud resources could partially replace local memory. Sometimes hybrid approaches are actually cheaper than buying enough local RAM for worst-case scenarios.

If You Can Wait

If your system is functional and you can delay upgrades, your best bet is patience. Set a price target (maybe $400-500 per 64GB kit) and wait for prices to hit that level before buying. Monitor prices weekly on PCPart Picker or similar sites.

This might take until late 2026 or 2027. It's frustrating. But buying at current prices and then watching prices drop by 50% a few months later is more frustrating.

Looking Ahead for Future Upgrades

As you build or upgrade systems going forward, think about memory headroom. Buy systems with a bit more memory than you strictly need today, specifically because memory is expensive right now. It's cheaper to buy extra memory now at a fixed price than to upgrade later when prices might be even higher.

Also, consider whether integrated or soldered memory might actually be a benefit now. Systems where you can't upgrade memory can't hit you with upgrade costs. It's a different trade-off when upgrades are expensive.

The price of 64GB DDR5 kits increased fivefold in six months, with a significant 50% rise in the last month. Estimated data based on market trends.

Industry Response and What Manufacturers Are Actually Doing

Samsung's Capacity Plans

Samsung, the largest DRAM manufacturer, has publicly discussed plans to expand capacity through 2026. But the timing is deliberate: they're expanding fast enough to prevent shortages from getting catastrophically worse, but slow enough that supply and demand stay tight. This is rational from their perspective because tight supply allows them to maintain high margins.

Samsung's been shifting production toward HBM (High Bandwidth Memory) which is used in AI accelerators. This is higher margin and higher demand. Consumer DDR5 gets what's left. This allocation strategy is likely to continue as long as AI demand remains explosive.

SK Hynix's Selective Expansion

SK Hynix has been more cautious about expansion. They've indicated they'll increase capacity, but slowly. They're also emphasizing specialty memory products over commodity DRAM. This is a reasonable strategy when margins are high: you don't necessarily want to flood the market with cheap commodity memory that would lower your per-unit profit.

Micron's Strategic Positioning

Micron has been caught between the US and China in terms of geopolitical considerations (they have significant operations in both regions, with restrictions on what they can do). They've been increasing capacity, but dealing with export restrictions and tariffs that complicate their supply planning. Their expansion is real but constrained by factors outside the pure supply-demand equation.

No New Competitors Emerging

Despite the high prices and strong demand, no new competitors have emerged. TSMC (the world's leading chip manufacturer) has talked about potentially entering the DRAM market, but nothing concrete. The barrier to entry is simply too high. Even with motivation, it would take 5+ years and $15+ billion to build a competitive DRAM fab. By the time it's operational, the market dynamics could be entirely different.

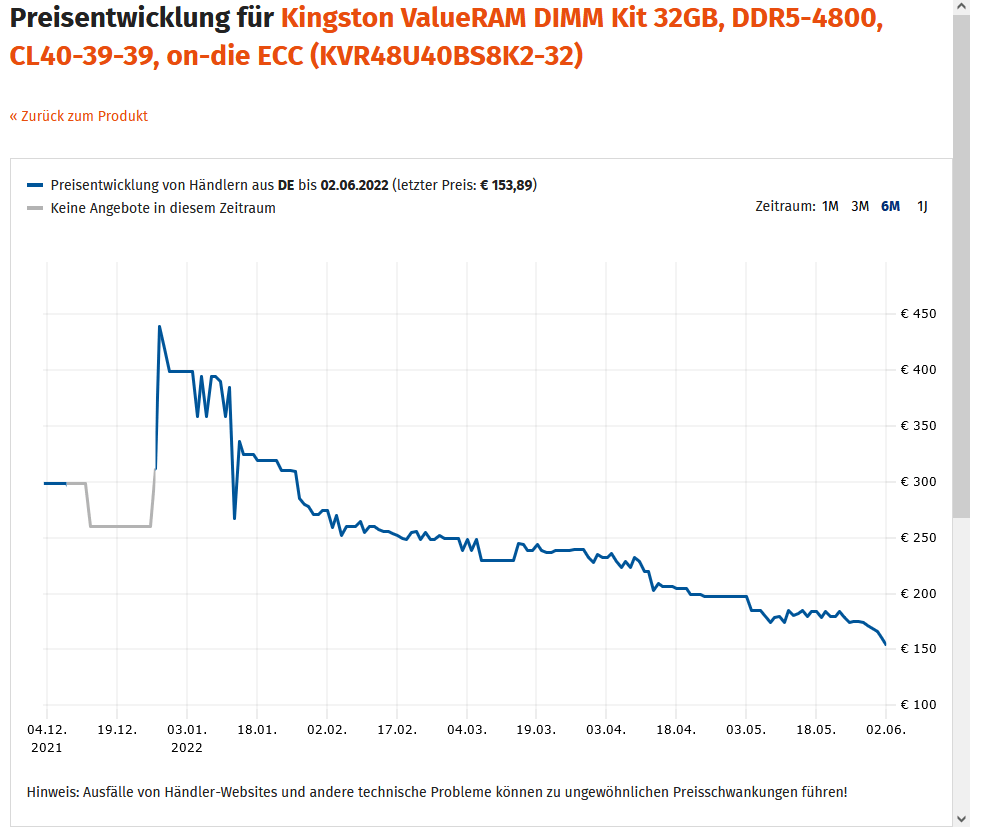

Comparisons to Other Component Price Spikes

GPU Market (2021-2023)

The GPU shortage of 2021-2023 is the most recent comparable crisis. Prices spiked dramatically, supply was constrained, and mining was a contributing factor. But the recovery was faster. Within 12-18 months of the crypto collapse, GPU prices normalized substantially.

Why the difference? Partially because GPU manufacturing is more distributed (multiple companies, multiple countries). Partially because consumer GPUs are higher volume and higher priority for manufacturers (higher margins). Partially because the demand shock (crypto mining) was more ephemeral.

The DRAM crisis is more persistent because the demand (AI data centers) isn't going away. It's structural, not speculative.

SSD Price Dynamics

SSDs experienced similar dynamics during the pandemic, but the recovery was faster and more complete. Within 2-3 years, prices were back to normal. The difference is that SSD manufacturing has many more competitors and many more fabs globally. When supply got tight, more players ramped production and competed prices down.

Memory is less competitive, so price recovery is slower.

Processor Cycles

CPU prices have been relatively stable despite increasing demand for computation. Why? Because there's competitive pressure from AMD, Intel, and ARM. Overpriced processors lose market share. Memory has no such competition at the high-end enterprise and data center level.

What Happens If This Doesn't Get Better?

The Consumer PC Becomes a Niche Product

If memory prices stay high indefinitely, consumer PC building as a hobby and practice probably declines. People move toward laptops with integrated memory (can't upgrade), consoles, and cloud-based computing. The enthusiast community shrinks.

This has cultural implications. PC building has been the gateway drug to computer science and engineering for many people. If it becomes too expensive, you lose some of that talent pipeline.

Enterprise Systems Get Weaker

Servers and enterprise systems still get memory because businesses need it. But at current prices, they'll build more efficiently. Smaller footprint servers, more aggressive memory compression, more reliance on tiered storage. These are all optimizations that work, but they make systems less flexible and potentially less performant.

AI Becomes More Expensive to Deploy

Paradoxically, high memory costs hurt AI deployment. Data centers need enormous amounts of memory to run AI workloads. If memory stays expensive, AI services stay expensive, adoption slows. This creates a feedback loop where constrained resources limit the growth of the demand that created the constraint.

FAQ

Why did DDR5 RAM prices spike so dramatically?

DDR5 prices spiked due to a convergence of factors: explosive AI data center demand created massive DRAM orders, production capacity couldn't ramp fast enough, older DDR4 was being phased out creating additional supply pressure, and DRAM manufacturers have limited competitors so high prices persist. The spike accelerated when supply tightness triggered panic buying and hoarding, creating a feedback loop that pushed prices from

When will DDR5 RAM prices return to normal levels?

Price stabilization won't happen quickly. The optimistic scenario has prices settling in the

Should I buy DDR5 RAM right now or wait?

If your system works adequately, waiting is the better choice. Prices are unlikely to decrease significantly in the next few months. If you absolutely need to upgrade now, consider DDR4 as an alternative, explore used modules from reputable sellers, or look at cloud-based solutions as workarounds. If you need a complete system soon and can't delay, budget for higher memory costs and adjust expectations about other components accordingly.

Why are only DRAM manufacturers producing DRAM?

Building a competitive DRAM fab requires $15-20 billion in capital investment and takes 3-4 years to construct. Only three companies (Samsung, SK Hynix, and Micron) have the expertise, capital, and existing fabs to compete. The barrier to entry is so high that even during a crisis with exploding prices, new competitors haven't emerged. This concentration creates structural inflexibility in supply.

How does the DRAM shortage affect AI development?

The DRAM shortage increases the cost of AI infrastructure, which increases the cost of training models and running services. However, large AI companies have direct relationships with DRAM manufacturers and long-term contracts that insulate them from retail price spikes. This creates an ironic situation where the DRAM shortage that was partly caused by AI demand actually hurts smaller AI companies and researchers more than it hurts the mega-platforms.

What components should I avoid buying right now due to supply constraints?

Beyond DRAM, watch out for advanced packaging capacity (used in high-end chips), specialized memory like HBM (High Bandwidth Memory used in AI accelerators), and substrate materials. Anything used in data center and AI applications is experiencing some supply pressure. Consumer-targeted components like gaming GPUs and gaming-focused SSDs are holding up better because competitive pressure keeps prices reasonable.

Can I build a functional PC system without upgrading RAM?

Absolutely. Start with 32GB DDR5 or even 48GB if you can find it at reasonable pricing. For gaming, streaming, and general productivity, 32GB is plenty. Only professional workloads (video editing, 3D rendering, machine learning) really need 64GB. If you're not doing those things, you're paying a premium for capacity you don't need.

What are my best alternatives to buying expensive DDR5 RAM?

Your options include: exploring DDR4 and compatible motherboards, waiting for prices to drop before upgrading, using cloud resources for memory-intensive workloads, optimizing existing software to use less memory, considering integrated GPU solutions that don't require as much system RAM, or looking at specialized hardware (ASICs, FPGAs) designed for specific tasks that need less memory than general-purpose compute.

Looking Forward: Lessons for the Industry

The DDR5 crisis reveals uncomfortable truths about modern computing infrastructure. When critical components are controlled by a tiny number of manufacturers on a single continent, supply shocks ripple through every layer of the industry. When one use case (AI data centers) can completely dominate allocation of a resource, everyone else suffers.

For manufacturers, the lesson is that building capacity is an existential question. The DRAM manufacturers who succeed over the next 2-3 years will be those that recognized the structural nature of AI demand and invested heavily in capacity. Those who didn't are watching market share slip away to companies that did.

For system builders and professionals, the lesson is that resource constraints are the new normal. You need to design systems assuming that future component prices will be higher than current ones. You need to optimize software assuming hardware will remain expensive. You need to build in flexibility so you're not locked into specific configurations when those specific components become scarce.

For consumers, the brutal lesson is that you can't assume technology prices follow a simple trajectory of always getting cheaper. Sometimes they get worse. Sometimes the improvement stops. And sometimes what you thought was a stable, commoditized market reveals itself to be surprisingly fragile.

The path out of the DRAM crisis is clear in theory but uncertain in practice. Manufacturing capacity needs to increase. AI demand needs to moderate or at least stabilize. And the entire industry needs to accept that some components will remain expensive because they're now strategic bottlenecks in a competitive environment.

Until that happens, if you need memory, you're paying the premium. And honestly, you'd better get used to it.

Key Takeaways

- 64GB DDR5 RAM kits exploded from 1000+ in six months, driven by AI data center demand and constrained DRAM manufacturing

- Only three companies (Samsung, SK Hynix, Micron) control DRAM production, eliminating competitive pressure and allowing high prices to persist

- Consumer memory is systematically deprioritized when supply tightens because data centers pay more and have direct manufacturer relationships

- Price normalization won't happen until 2026-2027 at earliest, with realistic scenario seeing prices stabilize at 200

- The crisis reveals structural fragility in computing supply chains where single bottlenecks can hold entire industries hostage

Related Articles

- RAM Price Surge 2025: What's Driving Costs Up and How to Cope [2025]

- GPU Memory Crisis: Why Graphics Card Makers Face Potential Collapse [2025]

- Intel Nova Lake 700W Power Consumption: What You Need to Know [2025]

- Nvidia RTX 50 Super Delayed: RTX 60 Series May Miss 2027 [2025]

- Raspberry Pi Price Hikes: The RAM Crisis Explained [2025]

- Raspberry Pi Price Increases 2025: Impact of Global Memory Shortage

![DDR5 RAM Price Crisis: From $200 to $1000+ in 6 Months [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/ddr5-ram-price-crisis-from-200-to-1000-in-6-months-2025/image-1-1770851287648.jpg)