The Graphics Card Memory Crisis Explained: What You Need to Know

Last year, something quietly shifted in the semiconductor world. Not gradually. Suddenly. Zotac—one of the world's largest independent graphics card manufacturers—went public with a warning that sent shockwaves through the industry: the current situation is "extremely serious" as reported by TechRadar. And they weren't exaggerating.

The problem isn't that memory chips don't exist. It's far worse than that. The architecture of modern graphics cards has created a bottleneck so severe that manufacturers are struggling to source the specific types of memory needed to build GPUs at scale. We're talking about high-bandwidth memory (HBM), memory systems that can deliver insane amounts of data in fractions of a second. Without it, you can't make a competitive graphics card. And right now, there's nowhere near enough to go around.

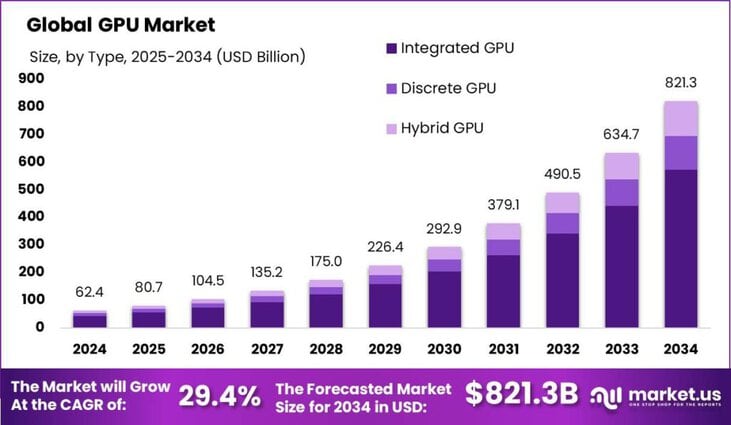

What makes this crisis particularly dangerous is its cascading effect. Nvidia, AMD, and Intel all depend on the same memory suppliers. Add in the explosion of demand from artificial intelligence workloads—where every data center wants the fastest GPUs possible—and you've created a perfect storm. GPU manufacturers are bidding against each other, prices are climbing, and smaller players who can't negotiate bulk orders are getting squeezed out entirely.

Here's the thing: this isn't a temporary supply blip like we saw with semiconductors during COVID. This is a structural problem with how the memory supply chain works. And if the major manufacturers can't solve it, we're looking at a scenario where only the biggest, most resourced companies survive. Nvidia will be fine. Most everyone else? That's where it gets scary.

TL; DR

- HBM shortage is critical: High-bandwidth memory production can't keep pace with GPU demand from AI and gaming

- Zotac sounded the alarm: Independent GPU makers are facing potential collapse due to supply constraints

- AI demand is reshaping supply chains: Data centers and AI companies are outbidding traditional PC gamers for memory allocation

- Smaller manufacturers face extinction: Only companies with massive negotiating power can secure stable memory supplies

- Bottom line: The GPU market consolidation is accelerating, potentially eliminating dozens of independent board partners

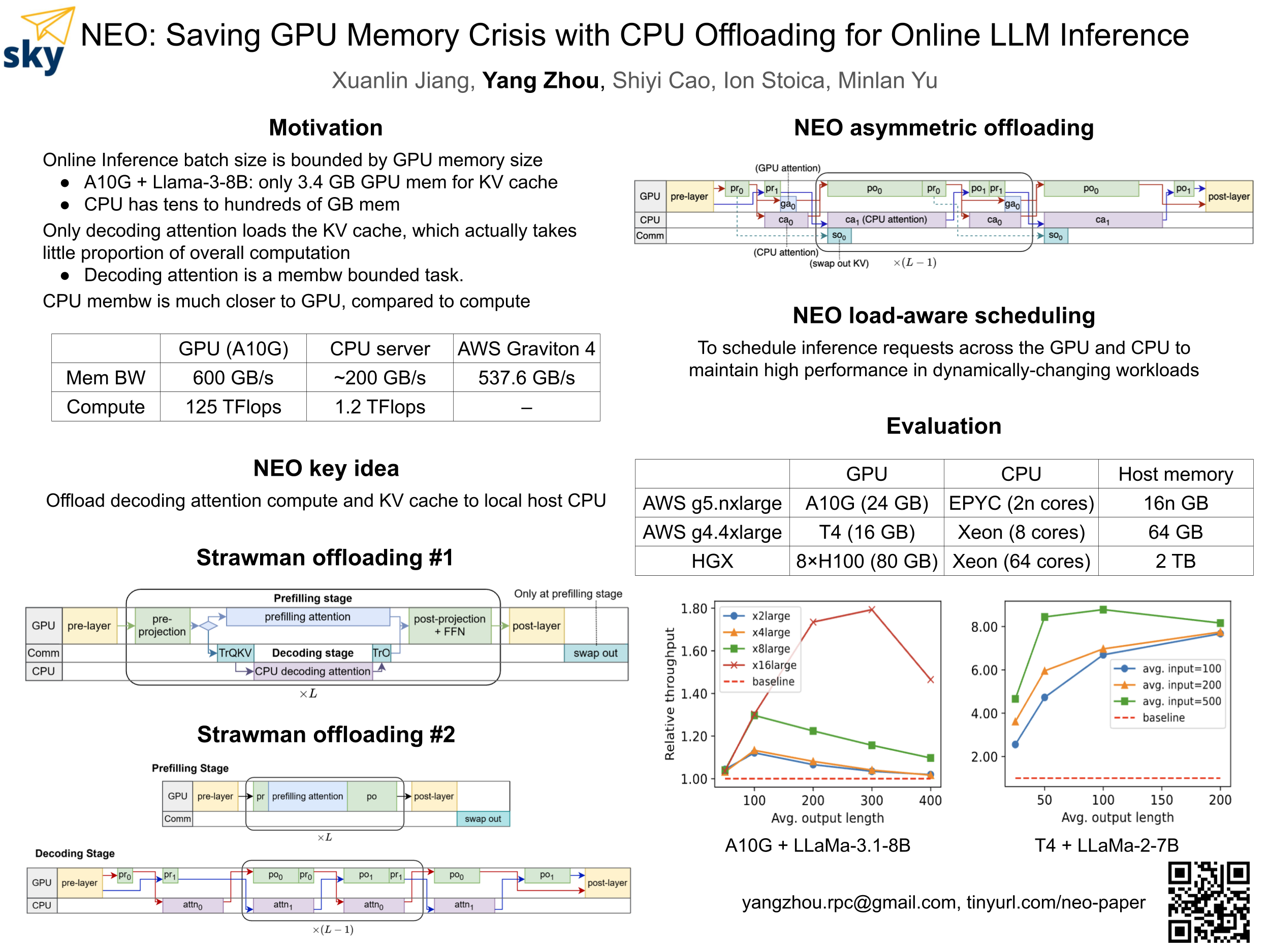

SK Hynix, Samsung, and Micron dominate the HBM market, with SK Hynix holding the largest share. Estimated data based on industry trends.

Understanding High-Bandwidth Memory: The Bottleneck Nobody Saw Coming

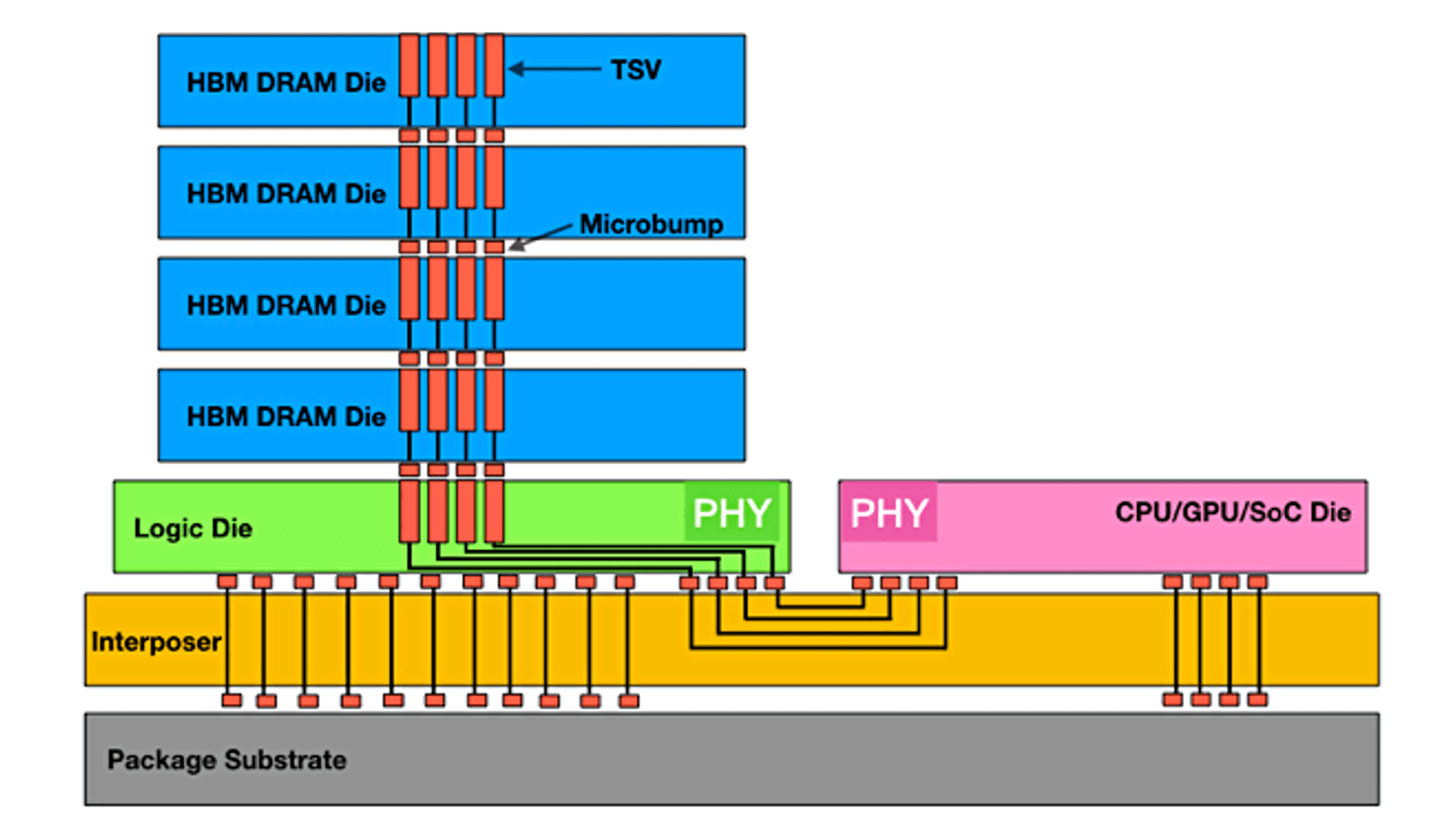

Let's start with what HBM actually is, because the technical distinction matters here. Standard memory—the GDDR6 or GDDR6X you find in most consumer GPUs—moves data at impressive speeds, sure. But it's got limits. When you're running massive AI models or complex 3D rendering tasks, that bandwidth becomes a constraint.

HBM solves this problem by stacking multiple memory chips vertically, connecting them with tiny copper pillars instead of traditional circuits. The result: massive increases in bandwidth with smaller physical footprints. A single GPU using HBM can move terabytes of data per second. For comparison, GDDR6 maxes out around 576 GB/s on most consumer cards. HBM can hit 2+ terabytes per second.

But here's the catch: HBM is ridiculously hard to manufacture. You need precision equipment. You need specialists. You need fab capacity that's been specifically configured for this exact process. And right now, only a handful of companies can produce it: SK Hynix, Samsung, and Micron. That's it. Three companies. Producing memory for billions of devices worldwide.

The yields are brutal too. Not every HBM stack comes off the production line working perfectly. Manufacturing defects are more common than with traditional memory. That means the three suppliers producing HBM are constantly dealing with rejected batches, rework scenarios, and production inefficiencies. Meanwhile, demand keeps climbing.

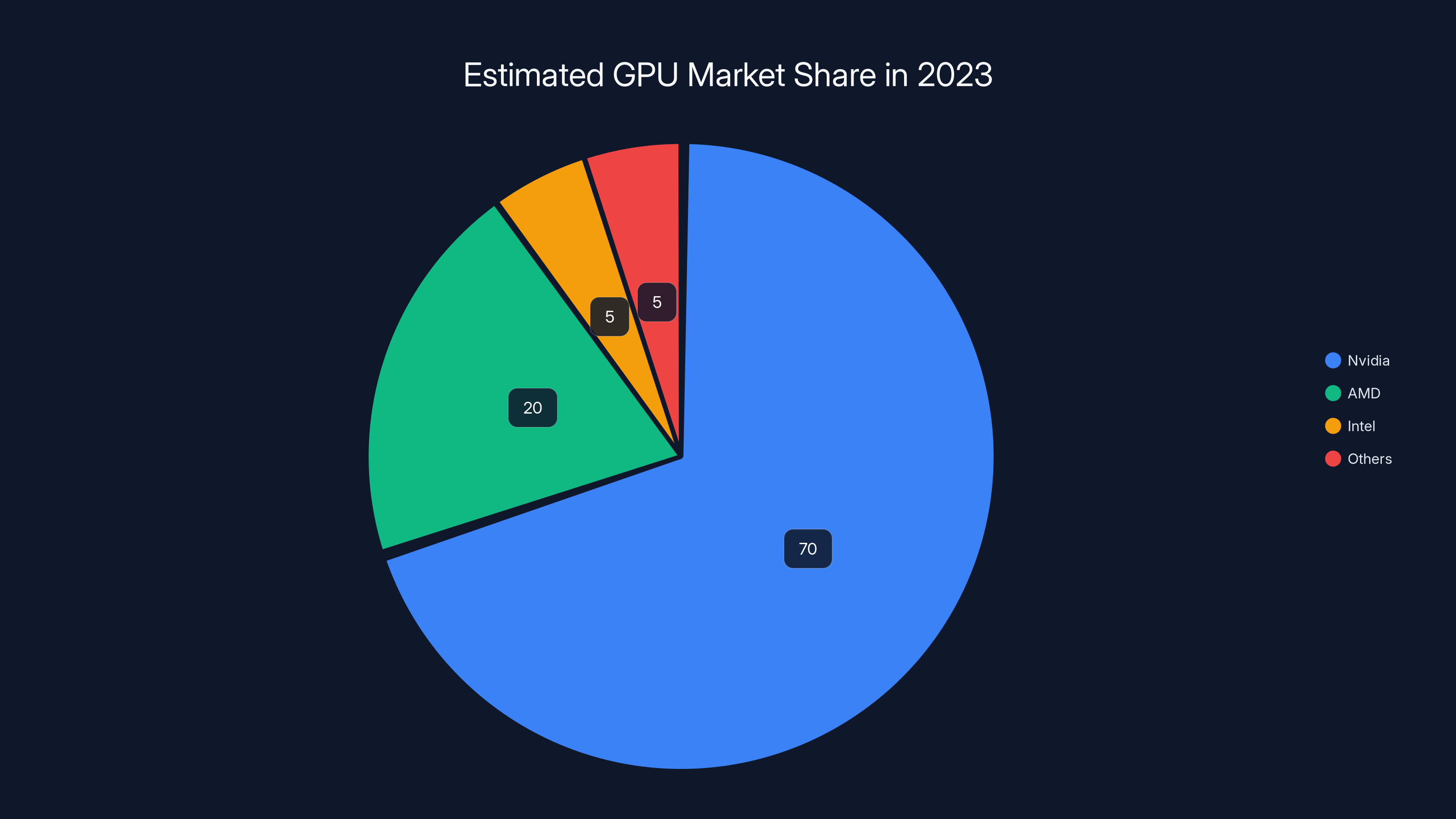

Nvidia's hoarding the supply they can get. They're the biggest player, they've got the strongest relationships with Samsung and SK Hynix, and they're essentially locking up future allocations. AMD is doing the same, just at smaller scale. Intel is desperately trying to secure supplies for their Arc GPUs. And independent board partners? They're fighting for table scraps.

The Artificial Intelligence Explosion: How AI Changed Everything

Two years ago, HBM demand was predictable. You had gaming GPUs, some data center orders, a few workstation builds. Manageable. Then Chat GPT happened. Then Claude. Then every tech company on Earth decided they needed to train their own large language models.

Suddenly, demand for high-end GPUs went vertical. Not just for training, but for inference—running those models in production environments where billions of requests need answers in milliseconds. Every request needs to move massive amounts of weights through memory. Without HBM, your latency kills your economics.

Data centers started ordering Nvidia H100s and H200s in quantities that made previous years look like rounding errors. Each H100 uses 80GB of HBM. A single data center expansion might require thousands of them. That's 80,000+ gigabytes of HBM, all going to one customer.

The math gets ugly fast. SK Hynix's annual HBM production capacity is in the range of 300,000-400,000 wafers. Samsung is similar. Micron is just ramping up capacity. When you do the math on how much HBM each modern AI GPU requires, you realize production can't expand fast enough to meet demand. It's not a shortage—it's a structural impossibility.

Gaming demand got shoved down the priority list almost overnight. Why would Samsung sell HBM to a board partner making consumer graphics cards when they can sell the exact same memory to Nvidia for data center GPUs at 2-3x the price? The economics don't even compete. Nvidia and the cloud providers pay premium rates, and they get the allocation. Everyone else waits.

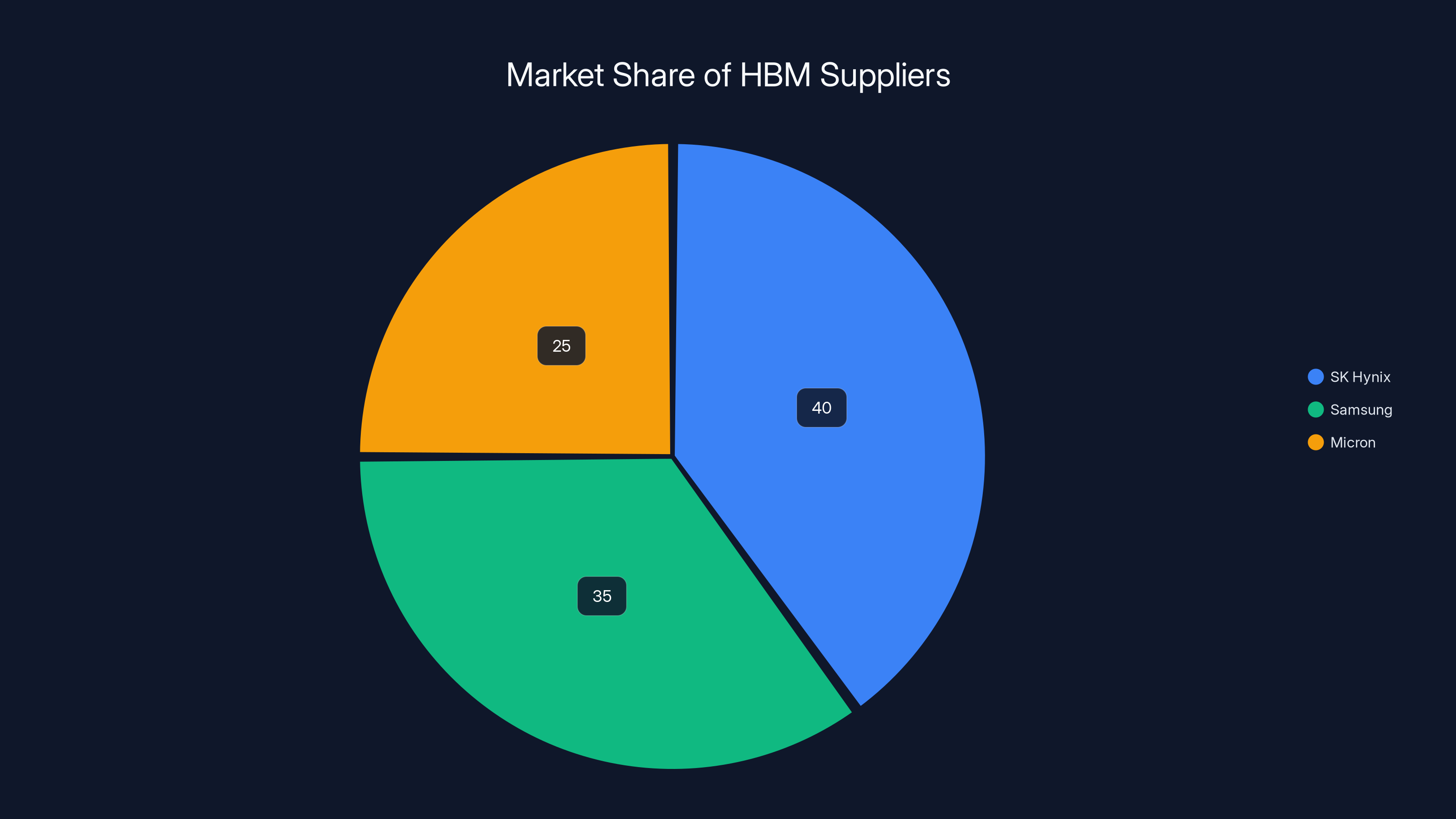

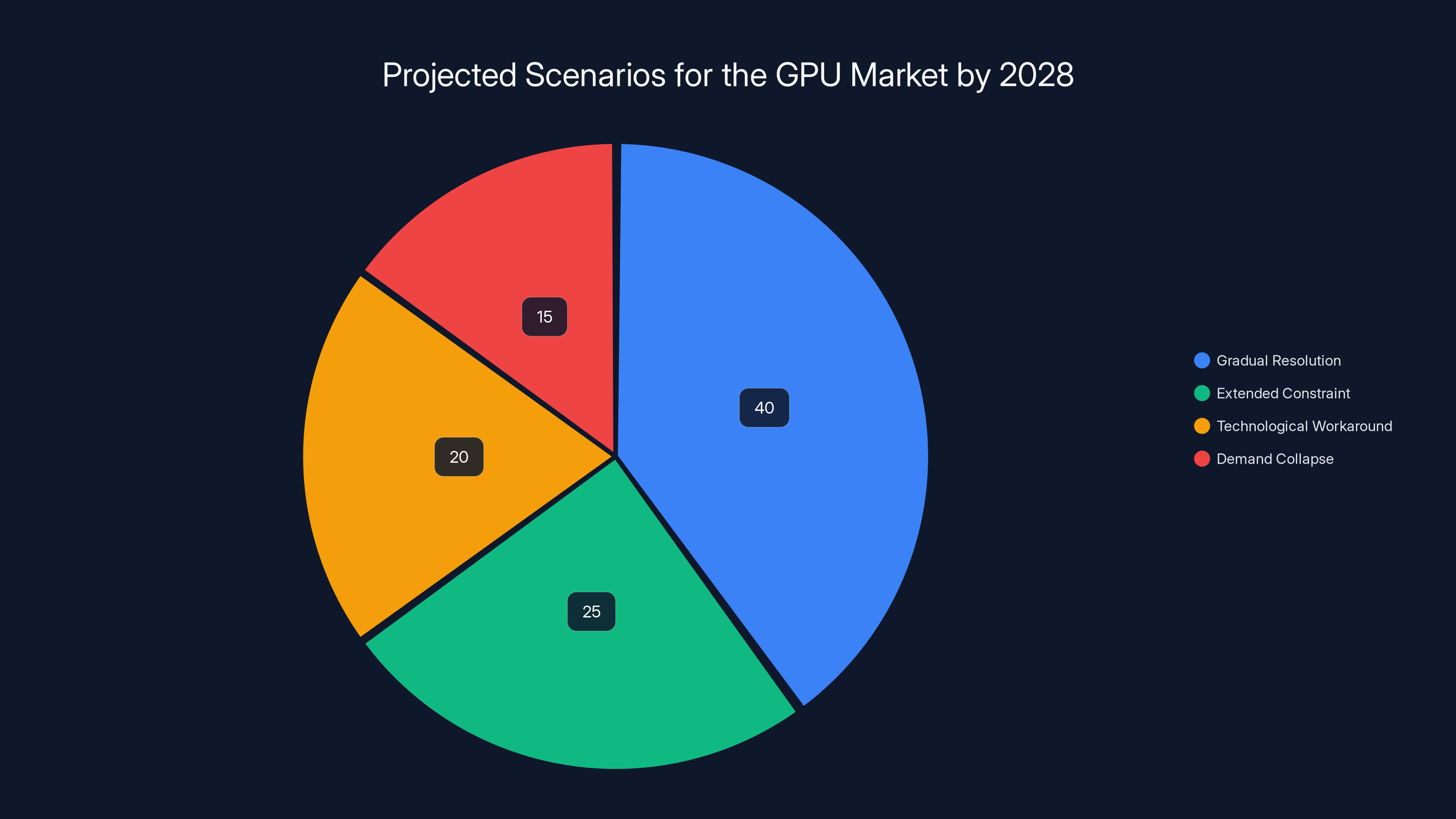

Industry observers estimate a 40% probability for a gradual resolution in the GPU market by 2028, with other scenarios having lower probabilities. Estimated data.

Zotac's Warning: What Independent Manufacturers Are Actually Facing

When Zotac said the situation was "extremely serious," they weren't being dramatic. They were describing an existential threat. Zotac is among the largest GPU board partners globally—they've been making graphics cards since the early 2000s, they have deep expertise in thermal design and PCB engineering, and they've built real brand recognition in the enthusiast community.

None of that matters if they can't get memory.

Zotac's supply agreements with Samsung and SK Hynix are minuscule compared to Nvidia's. When allocation decisions happen, Nvidia's orders get fulfilled first. AMD negotiated better deals early. Intel is burning through their allocated supplies trying to compete. That leaves Zotac competing with Palit, Gainward, Asus, Gigabyte, MSI, PNY, and dozens of other partners for whatever crumbs remain.

This creates a vicious cycle. If Zotac can't source memory consistently, they can't make products. If they can't make products, they can't maintain supply relationships with retailers. If they lose retail relationships, consumers start buying from competitors. Eventually, they lose market share, which weakens their negotiating position even further, which gets them allocated even less memory.

The timeline here matters. We're not talking about problems emerging in 2030. Zotac's warning suggests the crunch is already happening now. Board partners are making hard choices: raise prices (losing customers), reduce production (losing market share), or exit the market entirely.

Smaller players are exiting. Colorful is scaling back. Sapphire is focusing on AMD exclusively. Zotac is looking for ways to survive. The consolidation is happening in real time, and it's happening because of memory allocation, not because better companies are winning. It's survival of the best-negotiated deals, not survival of the best-engineered products.

The Supply Chain Architecture: Why This Problem Is Structural

Understanding why this crisis happened requires looking at how the memory supply chain is actually structured. And it's more fragile than most people realize.

Historically, memory production was geographically distributed. You had multiple manufacturers in South Korea, Taiwan, Japan, the US, and elsewhere. If one had capacity issues, others could step in. That redundancy was built into the system almost by accident.

Then consolidation happened. SK Hynix acquired Intel's NAND business. Samsung merged operations. Micron acquired Crucial and other brands. The industry went from having 20+ serious memory manufacturers to roughly 3 that matter for HBM production. Consolidation made the industry more efficient, more profitable, and catastrophically more brittle.

Add in geopolitical complications. SK Hynix is South Korean. Samsung is South Korean. Micron is American. If tensions rise between the US and China, if there's a conflict in Taiwan (where semiconductor equipment comes from), if there are export restrictions, the entire system seizes up. There's no backup plan because the backup plan was supposed to be "use a different manufacturer," except there basically aren't any.

The HBM production process specifically requires equipment from companies like ASML in the Netherlands. ASML's capacity is constrained. They're already producing equipment for TSMC, Samsung, and SK Hynix's other operations. Getting more capacity requires 2-3 year waits and billions in capex. Nobody wants to invest that capital when demand might be a temporary spike from AI hype, right?

Except it's not temporary. The demand is real. Data centers are building out AI infrastructure permanently. They're going to need more GPUs every single year for the foreseeable future. The suppliers know this. They're investing, but they're investing slowly, cautiously, because they've been burned before by demand spikes that evaporated.

Meanwhile, the clock is ticking for GPU manufacturers who can't get memory. Six months without supplies, you start losing customers. Twelve months, and you might not recover.

Gaming GPUs vs. Data Center GPUs: The Priority Mismatch

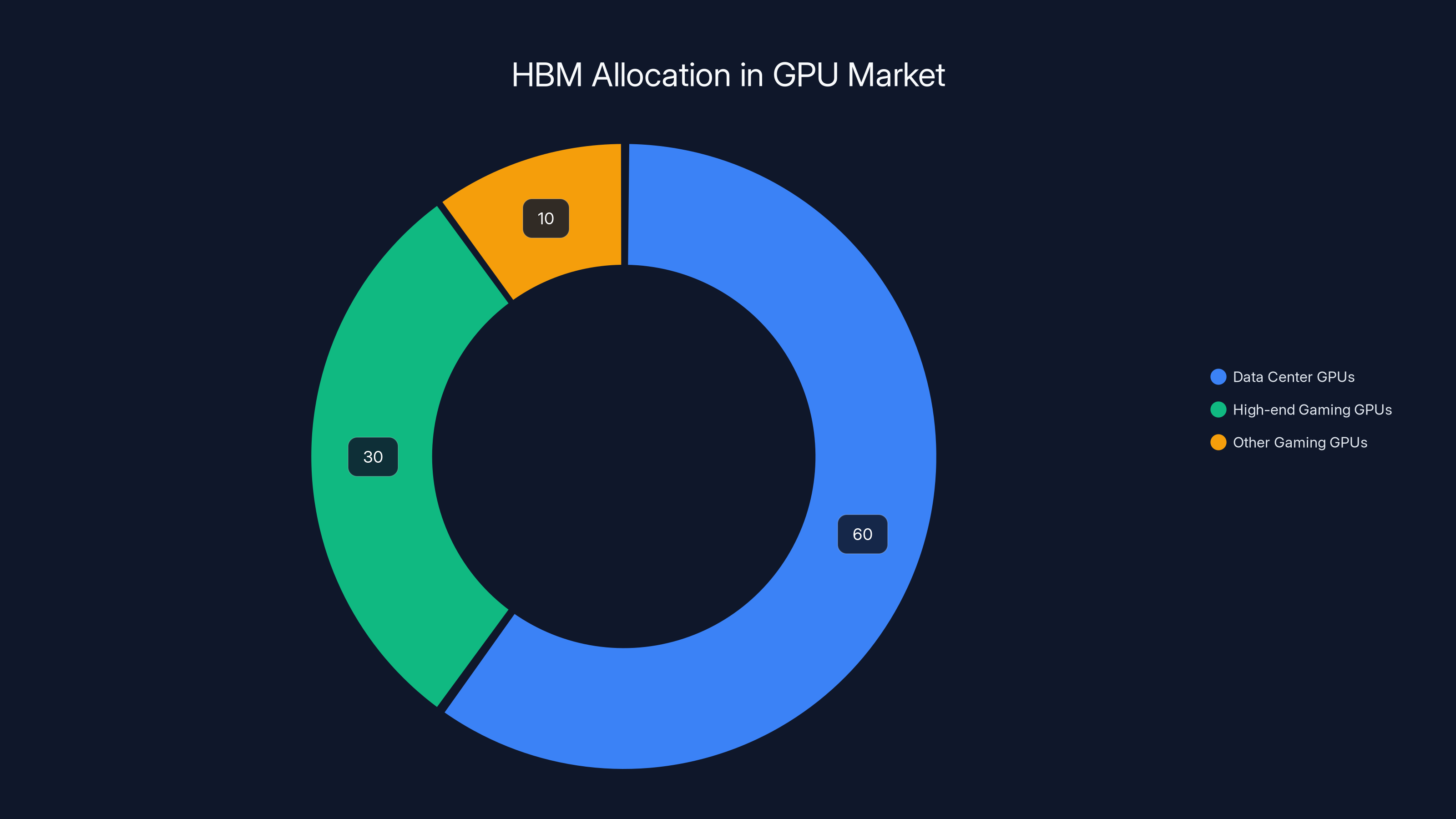

Here's where the market gets divided in ways most consumers don't understand. There are essentially two classes of GPUs right now: gaming GPUs and data center GPUs. They're often based on the same silicon, but the allocation priorities are completely different.

Gaming GPUs (Nvidia RTX 40-series, AMD Radeon RX 7000-series) use HBM in some models but often use GDDR6X for cost and yield reasons. This gives Nvidia and AMD flexibility. They can produce gaming cards without competing for scarce HBM. They use HBM where it matters most—in high-end gaming cards that command premium prices.

Data center GPUs are different. The H100, H200, L40S, and similar professional cards demand HBM because the workloads demand it. You're moving gigabytes of model weights through memory every second. GDDR6 becomes a bottleneck that kills performance. These cards are too expensive and too performance-critical to accept memory compromises.

So Nvidia makes both, and when HBM allocations come in, they fulfill professional GPU orders first. Gaming cards that use HBM get what's left. Gaming cards that use GDDR6 get what they need. And independent board partners? They're trying to make both, but they can't guarantee either, so they're getting decimated.

AMD has a different problem. Their MI300 and MI300X accelerators use HBM exclusively. There's no GDDR6 alternative. If they can't get HBM, they can't make those chips. And AMD has been pushing aggressively into AI/data center markets because that's where the growth is. Gaming GPUs feel like the legacy business to them now.

This creates a strange situation for the gaming market. Nvidia can theoretically keep supplying gaming GPUs by using GDDR6 and leaning on professional GPUs for HBM consumption. But board partners don't have that luxury. If they want to make competitive gaming GPUs, they need HBM. If they can't get HBM, they either make weaker products that get crushed by Nvidia's offerings, or they exit the market.

Nvidia is estimated to hold a dominant 70% market share in 2023, with AMD at 20% and Intel emerging at 5%. Smaller players are increasingly marginalized. (Estimated data)

The Economics of Scarcity: Why Prices Are Rising

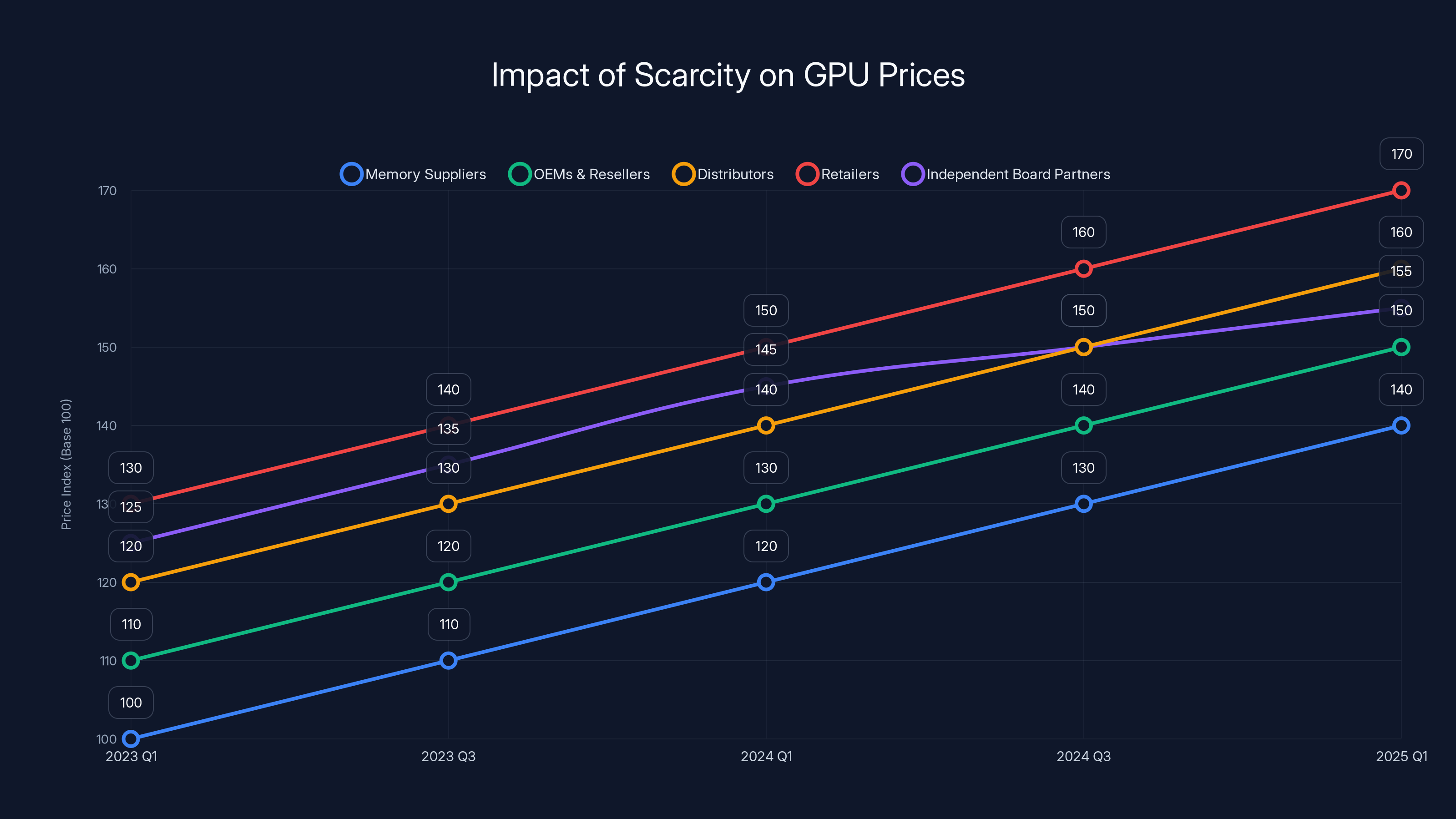

Basic economics: limited supply plus increased demand equals rising prices. But the price story here is more complex because it's not just end-user prices that are rising. It's happening throughout the supply chain.

Memory suppliers are raising prices to buyers. Nvidia is passing those costs through to OEMs and resellers. AIBs and board partners are raising prices to distributors. Distributors are raising prices to retailers. Retailers are raising prices to consumers. By the time a GPU reaches a consumer, multiple markup layers have stacked on top of the core memory cost increases.

But there's a twist: independent board partners can't necessarily pass those costs through the same way Nvidia can. Nvidia has brand power. Consumers pay a premium for Nvidia's reference designs. But if Asus or MSI raises prices on their RTX 4070 Super design because HBM costs are up, consumers might just buy the Nvidia Founders Edition instead.

So the squeeze hits independent partners hardest. They're paying more for scarce memory, but they can't raise prices as much as their costs are rising, because they don't have brand inelasticity. Their margins compress. Eventually, if the situation persists long enough, their margins disappear entirely.

We're already seeing this play out. In late 2024 and early 2025, several smaller board partners announced they were deprioritizing GPU manufacturing and focusing on other product categories. That's not a strategic pivot. That's margin death. They looked at the memory costs, the pricing power they actually have, and concluded the GPU business wasn't worth it anymore.

Nvidia, by contrast, can sustain higher costs because their professional segment has almost unlimited pricing power. Data centers will pay whatever is necessary to get the latest GPUs because they're essential infrastructure for AI workloads. That pricing power funds the gaming segment's losses. For independent partners, they don't have that cross-subsidy. Every segment has to stand on its own.

Capacity Expansion: The Slow-Motion Solution

SK Hynix, Samsung, and Micron are all investing in HBM capacity. They're not ignoring the problem. But they're approaching it cautiously, and the timeline is long.

Micron is building new fabs. SK Hynix is expanding existing facilities. Samsung is allocating more wafer starts to HBM production. But all of this takes time. A new fab might take 3-4 years to build and qualify. Expanding existing capacity takes 18-24 months minimum. And nobody wants to invest massive capital without confidence demand will sustain.

Here's the chicken-and-egg problem: memory suppliers are reluctant to expand capacity aggressively without long-term contracts guaranteeing they'll sell the output. GPU manufacturers and AI companies are reluctant to sign long-term memory contracts at premium prices without knowing if they'll need that much capacity in 2-3 years. So capacity expansion happens slowly, conservatively, always slightly behind actual demand growth.

Micron is the most aggressive. They're betting that AI demand is real and structural, and they're committing capital to HBM production at scale. If their bet is right, they'll eventually have significant HBM market share and can compete with SK Hynix and Samsung. But that's 2027 at the earliest.

In the meantime, the crunch continues. Production might grow 15-20% per year, which sounds good until you realize demand is growing 40-50% per year. The gap actually widens for the next 18-24 months before starting to narrow.

GPU manufacturers are hedging by diversifying. Some are looking at 2.5D packaging techniques that can mimic HBM density without requiring pure HBM. Others are designing custom architectures that reduce memory bandwidth requirements. Nvidia is exploring chiplet designs that split memory and compute. But all of these require new designs, new validation, new manufacturing processes. They're 12+ month projects at best.

For board partners, this is a nightmare scenario. They don't have resources to design custom architectures. They're stuck buying reference designs from Nvidia or AMD and adding their own thermal solutions and cosmetics. When Nvidia can't deliver enough HBM-based designs, neither can the board partners.

The Consolidation Narrative: Market Structure Is Changing

Historically, the GPU market had room for independent players. Nvidia dominated, sure, but AMD competed credibly, and dozens of board partners added value through thermal engineering, software bundles, warranty programs, and community reputation.

That market structure is collapsing in real time.

The crisis isn't creating the consolidation—it's accelerating consolidation that was already happening. For years, Nvidia's dominance made the market less interesting for competitors. Data center players chose Nvidia almost by default. Gaming consolidated around Nvidia's Ge Force lineup. The board partner ecosystem became commoditized, with most partners essentially making identical designs with different coolers and stickers.

The memory crisis is just the final blow. Once supply constraints hit, the board partners with the best supplier relationships survive. Those relationships typically exist for manufacturers who have scale and credibility. Asus, Gigabyte, and MSI are massive companies—they can survive. Smaller players get crushed.

This has real competitive implications. Innovation in GPU design often came from board partners experimenting with unusual cooling approaches, aggressive binning strategies, or custom PCB layouts. As those players disappear, that experimentation disappears too. The market becomes more homogeneous. Consumers get fewer choices. Prices likely stay higher longer because there's less competition to undercut.

Intel is in an interesting position here. Arc GPUs are new, so their supply chains aren't as established. But Intel is investing heavily in both Arc GPU development and memory production. They have captive NAND production and are looking at HBM production paths. In theory, Intel could become a significant GPU player by 2026-2027 if they solve the memory constraints that plague independent partners. But that's a big if.

For Nvidia, consolidation is great. More market share. Less competition. Stronger pricing power. Nvidia's probably being careful not to be too obvious about it, but they're definitely not incentivized to solve the memory crisis quickly. A gradual shortage that kills competitors while they maintain supply? That's the optimal scenario from their perspective.

Estimated data shows that data center GPUs receive the majority of HBM allocation (60%), followed by high-end gaming GPUs (30%), with other gaming GPUs receiving minimal HBM (10%).

Geopolitical Risks: One Crisis Away From Catastrophe

The memory supply chain is global, and global means vulnerable to geopolitical shocks.

SK Hynix and Samsung both have significant manufacturing in South Korea. South Korea's relationship with North Korea is tense. South Korea's relationship with China is complicated by ongoing US-China tensions. If something escalates—sanctions, conflict, export restrictions—HBM production gets disrupted immediately. There's no buffer. No alternate source. Just crisis.

Taiwan produces most of the semiconductor manufacturing equipment globally. TSMC is in Taiwan. A cross-strait conflict would devastate global semiconductor production for years. Memory wouldn't be the only constraint—it would be everything. But memory would be part of that systemic collapse.

Micron production is in the US, which provides some geographic diversification. But Micron's HBM ramp is slower than SK Hynix or Samsung. If those suppliers faced disruption, we wouldn't have American capacity to backfill the gap.

Export controls are a constant threat too. The US has been tightening restrictions on advanced semiconductor exports to China. If those restrictions expand to encompass HBM, or if other nations impose reciprocal restrictions, the implications are severe. China can't buy the latest GPUs. That eliminates a significant portion of potential data center demand. Suppliers are stuck with excess capacity they invested billions to build.

These aren't abstract risks. They're present threats in the geopolitical environment. A US-Taiwan conflict, a Korea crisis, escalating US-China tensions—any of these would make the current memory shortage look quaint by comparison.

GPU manufacturers are aware of this. They're trying to build supply chain redundancy where possible. But you can't really redundify something that's structurally constrained. You can't have backup suppliers when there are only three meaningful suppliers globally.

This might push more investment toward domestic production in the US, South Korea, and Europe. That's economically inefficient but geopolitically necessary. You might see government subsidies for memory production on "allied" soil even if it's not the most efficient use of capital. Strategic autonomy is becoming a real priority.

The GPU Market's Future: What Happens Next

Projecting forward, there are a few scenarios.

Scenario One: Gradual Resolution. Memory capacity expands enough to meet demand by 2026-2027. Prices stabilize. Independent board partners mostly survive, though many are smaller and weaker. The market consolidates but doesn't collapse. This requires everything to go relatively smoothly—capacity expansion stays on schedule, geopolitical tensions don't escalate, and AI demand grows but doesn't hit additional explosive growth curves.

Scenario Two: Extended Constraint. Memory capacity expansion hits obstacles. Delays accumulate. Shortages persist through 2027-2028. More board partners exit. The GPU market becomes almost entirely Nvidia (gaming) and Nvidia/AMD (data center). Consumers have minimal choice. Prices stay elevated. Independent innovation in GPU design becomes nearly extinct.

Scenario Three: Technological Workaround. GPU designers find ways to reduce memory bandwidth requirements or use hybrid memory architectures that don't depend entirely on HBM. This accelerates the timeline for resolution. Board partners who can implement these designs survive. Nvidia and AMD have to actually compete on architecture and software, not just memory allocation. This is probably the best scenario for competition and consumer choice, but it requires significant R&D investment and a 18-24 month timeline minimum.

Scenario Four: Demand Collapse. AI investment hits diminishing returns. The explosive growth in data center demand slows or reverses. GPU demand drops 30-40%. Memory suppliers suddenly have excess capacity. But board partners are already gone, so there's no competitive alternative to Nvidia. Nvidia basically owns the market, sets whatever prices they want, and market consolidation is permanent.

Most industry observers think Scenario One is most likely, with probabilities of Scenario Two or Three creeping up as more disruptions happen.

For consumers, none of these scenarios is ideal. Best case, prices decline modestly and choice improves slightly by 2027. Worst case, we're stuck with Nvidia-only options and whatever pricing Nvidia wants to charge. Most likely, we get something in between: slightly improved choice, slightly declining but still-elevated prices, and a GPU market that's fundamentally less competitive than it was five years ago.

What This Means For Different Audiences

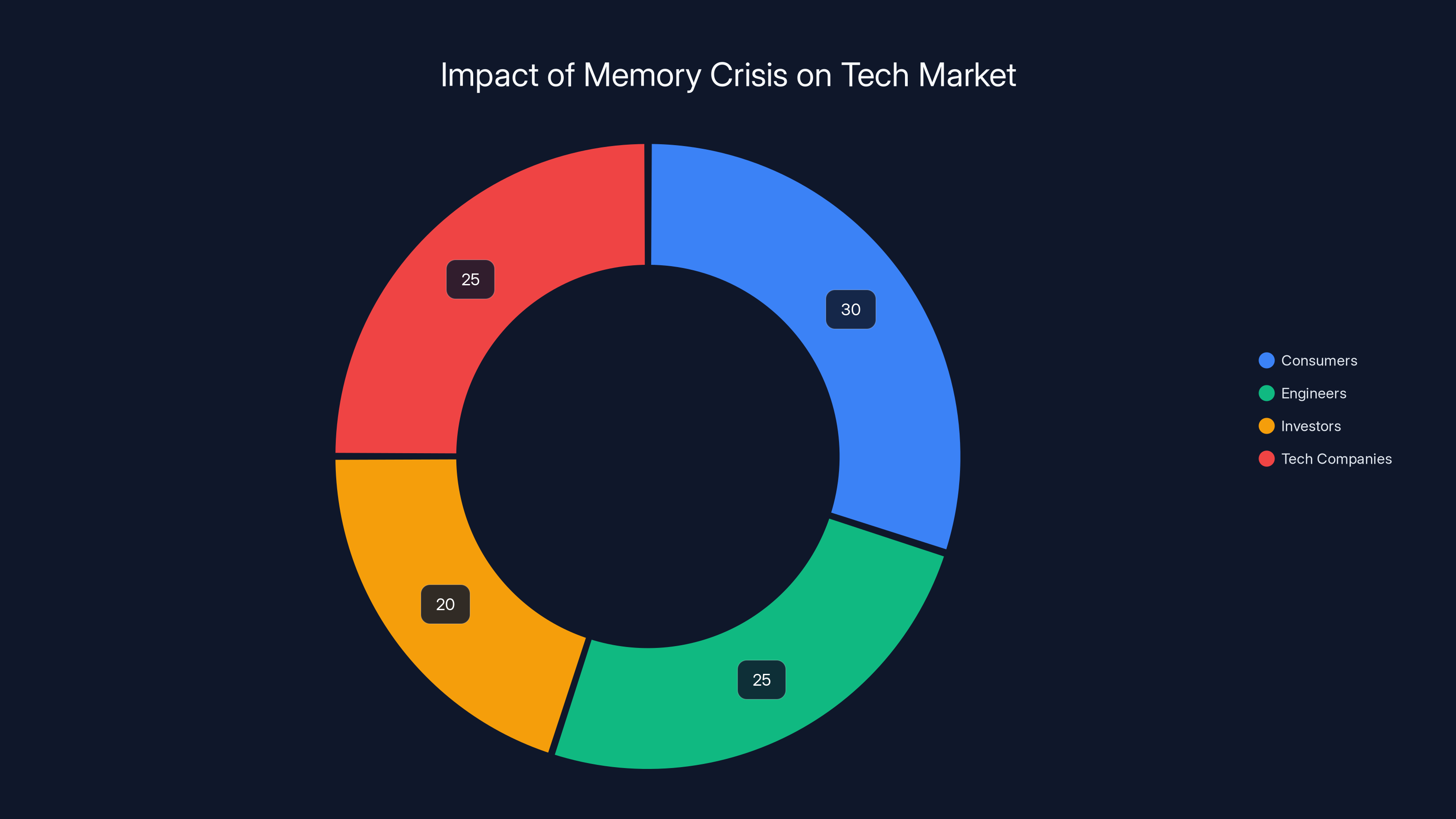

The memory crisis affects different groups in completely different ways.

For Gamers: This is annoying but manageable. Gaming GPUs can still be made with GDDR6 memory even if HBM becomes unavailable. You might see higher prices and fewer enthusiast options, but high-end gaming GPUs will remain available. The real issue is that fewer board partners means fewer custom cooler designs, fewer binned/sorted variants, and fewer price competition points.

For AI/Data Center Buyers: This is severe. Data center GPUs absolutely require HBM. There's no workaround. If you need AI accelerators and they're constrained by HBM supply, you're stuck waiting in allocation queues or paying premium prices. This directly impacts AI infrastructure expansion timelines and costs.

For GPU Manufacturers: This is existential. Nvidia can probably survive without major changes, but AMD needs to execute perfectly on their MI300 architecture, and Intel absolutely needs their Arc GPUs to break through, or they'll be squeezed out by supply constraints and competitive dynamics.

For Board Partners: This is extinction level. Most independent partners don't have the negotiating power or financial resources to survive 3+ years of constrained supply. The ones that do will be dramatically smaller and weaker than they were in 2023.

For Component Suppliers: This creates opportunity for companies that can provide alternative solutions—custom memory systems, chiplet designs, new packaging technologies, anything that reduces HBM dependency. Companies executing on these paths could become valuable M&A targets.

Estimated data shows that consumers and tech companies are equally affected by the memory crisis, each facing 25-30% of the impact, while engineers and investors experience slightly less impact.

The Efficiency Paradox: Why Scarcity Creates Stagnation

Here's a counterintuitive element to all this. Scarcity should theoretically drive innovation. When supply is constrained, companies race to invent alternatives, efficiency improvements, and workarounds. This should accelerate the pace of GPU innovation.

Instead, the opposite is happening. Scarcity is reducing innovation.

Why? Because the companies with the most resources to innovate (Nvidia, AMD, Intel) are too busy managing allocation crises to invest significantly in architectural innovation. They're focusing on maximizing output from existing designs, not designing new ones. It's all hands on deck for supply chain management and customer relationship management.

Board partners would normally drive innovation through experimentation and custom designs. But they're too busy fighting for survival. No board partner is going to invest in a novel cooling system or custom PCB design when they don't know if they'll be able to source the GPUs to build at all.

This creates a stagnation effect. The GPU market is likely going to see slower architectural innovation over the next 2-3 years despite enormous computational demand growth. That's inefficient at a systemic level—we could be solving harder problems with better tools, but instead resources are going toward allocation logistics.

Once the memory crisis resolves (or becomes the "new normal" and companies adapt to it), innovation will probably accelerate again. But there's likely a 18-24 month window of relative stagnation where GPU architecture doesn't advance as quickly as it could.

Mitigation Strategies: What Players Are Actually Doing

Companies affected by the memory crisis aren't just accepting it—they're implementing strategies to mitigate the impact.

Nvidia's Approach: Secure supply first, everyone else second. Nvidia signed long-term contracts with SK Hynix and Samsung that guarantee significant allocation. In exchange, they're probably paying premium prices, but they're ensuring supply certainty. They're also diversifying their product portfolio so high-end professional GPUs use HBM while mainstream gaming GPUs use GDDR6. This lets them fulfill consumer demand even when HBM is constrained.

AMD's Approach: Double down on professional GPU architecture where HBM is essential and pricing power is strongest. De-emphasize gaming GPUs where they were losing to Nvidia anyway. This is partially a strategic choice but partially a necessity—AMD doesn't have the negotiating power Nvidia does, so they're focusing on segments where they can operate profitably even with constrained supply.

Intel's Approach: Invest vertically. Intel is trying to secure memory supply by building HBM production capacity themselves. They're not there yet, but they're committed. They're also designing Arc GPUs with efficiency in mind—getting more performance per unit of memory bandwidth. If they can execute this, they break the supply constraint that affects everyone else.

Board Partners' Approach: Consolidate or exit. That's not a strategy so much as a reality. Small board partners don't have the resources to weather extended supply constraints, so they're either consolidating with larger partners, exiting the discrete GPU market entirely, or focusing on other product categories (SSDs, motherboards, cooling solutions) where they can compete without being constrained by Nvidia or AMD's supply decisions.

These strategies are all second-best solutions. The optimal solution would be more memory suppliers and more production capacity. But that requires capital investment and a multi-year timeline. So companies are doing what they can with the constraints they face.

The Macro Picture: Why Supply Chains Are Fragile

Zooming out, the memory crisis is a symptom of something larger: global supply chains optimized for efficiency are extraordinarily fragile when facing disruption.

The semiconductor industry spent decades consolidating and specializing. SK Hynix became the expert in DRAM and HBM. Samsung became the diversified memory powerhouse. TSMC became the foundry. This specialization drove incredible efficiency gains. Prices fell. Performance improved. Consumers got better products cheaper.

But specialization creates vulnerability. When demand patterns change suddenly—as they have with AI—the specialized suppliers can't easily respond. They've optimized for the old demand pattern. Scaling to the new pattern requires capital investment, facility buildout, and supply relationships that take years to establish.

There's also been a general trend toward just-in-time manufacturing and inventory reduction. Companies keep minimal inventory because inventory is expensive and ties up capital. But minimal inventory means zero buffer for disruptions. When something changes, there's no buffer to smooth the transition.

The memory crisis is partly a manifestation of these systemic supply chain dynamics. It's not unique to memory or GPUs. You see the same pattern across chips, rare earths, energy, agriculture. Specialized, efficient, optimized supply chains that break catastrophically when conditions change.

Solving this requires building in redundancy, which is economically inefficient but strategically necessary. It requires having backup suppliers even when they're more expensive. It requires maintaining inventory buffers even though they don't make financial sense. It requires building production capacity in geopolitically diverse locations even though it increases costs.

None of this is being done systematically because it's economically irrational from a company-level perspective. But from a systemic perspective, it's essential. We're probably going to keep seeing these crises until there's a forcing mechanism that makes companies prioritize resilience over pure efficiency.

Estimated data shows rising prices across the GPU supply chain from 2023 to 2025, with independent board partners facing the most significant margin compression.

The Human Cost: What Happens to Engineers and Employees

The abstract discussion of supply chains and market consolidation masks real human impacts.

When smaller GPU companies exit the market or get acquired, engineers lose their jobs. Designers who spent years developing custom thermal solutions or mastering specific manufacturing processes suddenly have skills that are less in-demand. Small companies that couldn't compete on supply chains had to compete on talent and innovation. Those advantages evaporate when the company exits.

Board partners employ thousands of people. Engineers, product managers, thermal designers, quality assurance specialists, customer service teams. As these companies consolidate or exit, those jobs disappear. Some talented engineers probably find roles at bigger companies, but smaller, regional players often can't easily relocate or don't have roles available.

This also affects innovation pipelines. Small companies are often where designers and engineers take bigger risks, try unconventional approaches, develop expertise in specialist areas. As the board partner ecosystem shrinks, those innovation pipelines shrink. Future GPU designers will mostly come from Nvidia, AMD, and Intel. The diversity of backgrounds and approaches gets narrower.

There's also a question of geographic impact. Some GPU board partners are based in regions with limited semiconductor expertise otherwise. As they disappear, those regions lose expertise centers and technical talent pools. Consolidation tends to concentrate talent in major tech hubs, reducing diversity of geographic innovation centers.

It's not catastrophic disruption like factory closures in declining industries. These are well-paid tech jobs in the semiconductor field, so displaced workers often do find new roles. But there's definitely friction, geographic disruption, and loss of specialized expertise.

Lessons From History: Consolidation in Semiconductors

This isn't the first time semiconductor markets have consolidated under supply pressure. There are historical lessons worth examining.

Memory, especially, has a history of boom-bust cycles and consolidation. DRAM used to have dozens of manufacturers. Now it's basically Samsung, SK Hynix, Micron, and small players in China. NAND flash went from dozens of manufacturers to maybe five major players. Each consolidation was triggered by overcapacity, price wars, or supply constraints that smaller players couldn't survive.

GPUs have been resistant to consolidation for longer than most semiconductor categories—the board partner ecosystem has remained relatively diverse even as Nvidia's market share climbed. But that's unusual. The historical pattern is toward consolidation.

The CPU market saw consolidation too. There used to be multiple x86 manufacturers. Now it's essentially Intel and AMD with Intel dominant. ARM has licensed designs, but the manufacturing is consolidated to a few players. ARM's success comes from not manufacturing at all—letting everyone use the same instruction set while competing on design. That's actually a clever way to maintain competitive diversity despite consolidated manufacturing.

GPU architecture could theoretically move in that direction. Instead of Nvidia designing GPUs and board partners just adding coolers, you could have standardized GPU instructions with multiple designers competing on architecture. That might preserve competitive diversity even if manufacturing becomes consolidated. But that would require architectural openness from Nvidia (unlikely) or a new architecture becoming dominant (possible but slow to achieve).

Historically, consolidation tends to be permanent. Once market leadership establishes, it's hard to dislodge. So if Nvidia becomes extremely dominant through this crisis, they'll probably stay dominant for years. That's not necessarily bad—Nvidia might deliver great products and fair pricing. But less competition is never ideal long-term.

What Could Save Independent Board Partners

Board partners aren't necessarily doomed. A few strategies could allow them to survive and even thrive.

Differentiation Beyond Coolers: Instead of just adding different thermal solutions to Nvidia's reference designs, board partners could develop deep optimization software, game profiles, overclocking utilities, or driver customizations that add real value. Asus has been moving in this direction with their software ecosystem. If that creates sufficient stickiness, it could sustain a price premium even with limited choices.

Vertical Integration: Partners could invest in memory production or partner with memory companies for secure supply. This requires capital and patience, but it could create competitive advantage. If Micron eventually becomes a major HBM supplier, they could favor partners they have financial relationships with.

Specialization: Instead of trying to make everything, partners could specialize. Make professional GPUs for data centers. Make custom solutions for specific industries. Make mining-optimized cards. Find niches where Nvidia and AMD don't want to compete, where supply constraints matter less.

Innovation in Packaging: If partners can develop superior cooling, better power delivery, or novel form factors, those become defensible differentiators. Laptop GPU modules for gaming laptops, for instance, where custom engineering is actually needed.

Regional Consolidation: Instead of global players, board partners could become regional powerhouses. Companies dominating Asia, Europe, and North America separately, rather than trying to compete globally. Regional logistics and customer relationships become competitive advantages.

Most likely, surviving board partners will combine several of these strategies. But the fact that they need strategies at all, rather than just being able to compete on product quality and innovation, shows how distorted the current situation is.

The Role of Open Source and Alternative Architectures

Open source GPU projects and alternative architectures like RISC-V could theoretically provide paths for smaller players to compete.

Projects like Mesa, LLVM, and open source driver development have reduced the barriers to entry for GPU software. You don't need proprietary compiler technology anymore—you can build on community open source. That levels the playing field for some dimensions.

ARISC-V GPUs (open source instruction set) could theoretically let smaller companies design GPUs without paying licensing fees to Nvidia. But RISC-V GPUs are early stage and not yet competitive on performance. It could take 5+ years for open ISA GPUs to compete credibly.

The challenge is that architectural innovation still requires massive R&D investment. Nvidia spends billions on GPU architecture research and development. That's not something a small board partner can compete with. Open source helps on the software side, but hardware design is still capital-intensive.

That said, if open GPU architectures eventually become competitive, it could reshape the industry. You could have competition among designers working on the same open instruction set. Similar to ARM's model. This would preserve competitive diversity even if manufacturing became consolidated.

This is probably a 5-10 year trajectory though. In the immediate term, open source and open ISA don't solve the current crisis.

The Investment Thesis: Where Capital Should Flow

If you're thinking about semiconductor or GPU-adjacent investments, this crisis has clear implications.

Bet on capacity expansion: Companies expanding HBM production—SK Hynix, Samsung, Micron—will benefit. Their memory products will be in chronic shortage, which means pricing power. Invest in the suppliers, not the consumers.

Bet on integration: Companies becoming more vertically integrated—Intel being the obvious example—can protect themselves from supply constraints. That's usually economically inefficient but strategically valuable in crisis conditions. Capital markets eventually reward this.

Bet on specialization: Companies that specialize in specific high-value niches (professional GPUs, AI accelerators, custom solutions) will survive better than those trying to serve everything. Look for GPU companies moving toward specialization.

Avoid commodity board partners: Traditional board partners without unique differentiation are in structural decline. Investing in them is betting on a turnaround that may not come.

Look for alternative memory technologies: Companies developing approaches that reduce HBM dependency—chiplet designs, optical interconnects, 3D packaging—are solving fundamental problems. That creates value.

Watch geopolitical moves: Government subsidies for semiconductor manufacturing in politically favorable locations will likely accelerate. Companies positioned to benefit from these subsidies will get capital injections. That's worth tracking.

The crisis is creating both challenges and opportunities. Investors who understand the structural dynamics can position capital accordingly.

Future-Proofing: What to Buy If You Need GPUs Now

If you actually need to purchase GPUs in the current environment, here's what matters.

For Gaming: Buy Nvidia or AMD directly (Founders Edition or reference designs). These have the most stable supply. Third-party designs might have supply issues. Don't buy specific board partner brands hoping for exclusive cooler designs—supply uncertainty isn't worth marginal thermal improvements.

For AI/Data Center: Secure allocation directly from Nvidia or AMD if possible. If you need third-party sellers, work with large, established partners (Asus, Gigabyte, MSI) rather than smaller specialists. They have better supply relationships. Consider long-term supply contracts even if they lock in higher prices—price certainty beats supply uncertainty.

For Professional Workstations: Professional GPU options are slightly less constrained than consumer cards because professional markets are smaller and more predictable. Invest in professional cards if your workload supports them. Better supply situation and total cost of ownership is usually lower.

For Laptops: Laptop GPUs are less constrained because they use mobile-optimized memory with different supply chains. If you need GPU compute power, laptops might be easier to get than discrete desktop cards.

For Storage/Caching: If you're building systems that need GPU memory bandwidth, consider whether you can solve the problem through clever caching, CPU optimization, or storage solutions. This might sound weird, but sometimes architectural optimization beats trying to buy expensive hardware in shortage conditions.

The common thread: prioritize supply certainty over feature optimization. Buy from established suppliers. Accept slightly higher prices as the cost of reliability. Plan for longer delivery times. These are the constraints of the current environment.

FAQ

What exactly is high-bandwidth memory (HBM) and why is it critical for modern GPUs?

HBM is a specialized memory architecture that stacks multiple memory chips vertically with direct copper connections, enabling data transfer rates exceeding 2 terabytes per second—roughly 3-4x faster than traditional GDDR6 memory. Modern AI GPUs and high-end gaming cards rely on HBM because they process massive datasets at extreme speeds. Without HBM, memory bandwidth becomes the bottleneck that kills performance in AI workloads where you're moving gigabytes of model parameters through memory continuously. For gaming, HBM provides headroom that keeps frame rates smooth even with massive textures and computational effects.

How does the memory shortage directly impact GPU manufacturers and board partners?

The shortage creates an allocation crisis because only three global suppliers produce HBM (SK Hynix, Samsung, Micron), and demand far exceeds supply. Large companies like Nvidia negotiate favorable long-term contracts, securing their allocation first. Independent board partners get whatever supply remains—which is often insufficient. This forces difficult choices: either raise prices (losing customers to cheaper competitors), reduce production (losing market share), or exit the market entirely. Many have chosen to exit.

Why can't GPU manufacturers just use alternative memory types to solve this problem?

Gaming GPUs have some flexibility and can use GDDR6 memory as an alternative, but professional and AI-focused GPUs absolutely need HBM's bandwidth. GDDR6 creates a performance ceiling that makes these specialized GPUs uncompetitive for their intended workloads. You could theoretically make an HBM-less AI GPU, but it would be slower and require multiple cards where one HBM card would suffice. The economics don't work. For board partners making consumer gaming cards, they can theoretically work around the shortage, but Nvidia and AMD prioritize their own products first, leaving partners with whatever reference designs remain available.

What timeline should we expect for the memory crisis to resolve or improve significantly?

Capacity expansion from SK Hynix, Samsung, and Micron should meaningfully reduce constraints by 2026-2027, assuming everything stays on schedule. Micron is the most aggressive with expansion plans. However, meaningful relief requires: no major geopolitical disruptions, memory suppliers maintaining investment momentum, and AI demand growth moderating slightly. If any of these assumptions break, the timeline extends. Most optimistic scenario has prices stabilizing by late 2026. Most pessimistic scenario has constraints persisting through 2028. Count on elevated GPU prices and limited options through at least 2025.

Which GPU manufacturers and board partners are most vulnerable to being eliminated by this crisis?

Smaller, independent board partners without strong supplier relationships face existential threats. Companies like Colorful, some smaller regional partners, and specialists without diversified revenue streams are most vulnerable. AMD has some vulnerability in gaming GPUs but is defending with data center focus. Intel is investing heavily to survive through custom solutions. Nvidia and the largest board partners (Asus, Gigabyte, MSI) are least vulnerable. The consolidation is already underway—by 2026, the industry will have significantly fewer GPU manufacturers than in 2023.

How does geopolitical tension (US-China, Taiwan, Korea) affect the memory supply situation?

The entire HBM supply chain has critical geopolitical concentration: SK Hynix and Samsung are in South Korea (tense with North Korea, complicated US-China relationships), TSMC in Taiwan (flashpoint for potential US-China conflict), and most semiconductor equipment from Netherlands and Japan. A Korea crisis, Taiwan conflict, or escalated trade restrictions could instantly cripple HBM production for months or years. There's no geographic redundancy. This risk is driving some governments to subsidize domestic memory production even at higher cost—strategic autonomy is becoming a real priority.

What does this crisis mean for gaming GPUs and prices for consumers?

Gaming GPU prices should gradually decline as HBM constraints ease, but don't expect dramatic drops. Nvidia will maintain strong pricing power regardless of supply situations. Third-party gaming cards will have fewer options as board partners consolidate. In the next 1-2 years, expect prices to stay elevated and choices to narrow. By 2027, if the crisis eases, consumer GPUs could see more competition and price pressure. Most optimistic outcome: 10-15% price declines by 2027. Most realistic outcome: prices stay flat or rise slightly, just with fewer vendor options.

Are there any technological solutions or architectural innovations that could bypass the HBM bottleneck?

Yes, several approaches could help: chiplet designs splitting memory and compute across separate dies, 2.5D packaging using high-speed interconnects instead of traditional HBM, optical memory systems using light instead of electrical signals, and software optimizations reducing bandwidth requirements. These are all 18-36 month projects at minimum. Chiplet designs are most practical near-term—AMD and Intel are already exploring these. Optical systems are longer-term research. None of these eliminate the need for HBM, but they could reduce how much is needed, easing allocation pressure.

Should I buy a GPU now before the crisis gets worse, or wait for supply to improve?

Depends on your actual need. If you need GPU compute power for work or serious hobbies, buy now from established manufacturers (Nvidia, AMD, or major board partners). Prices probably won't drop meaningfully for 12+ months, and you get value from using the hardware. If you're speculative about needs, wait. Prices won't improve dramatically in the next year, but options and availability will improve. Avoid smaller board partner brands—supply is unreliable. Professional GPUs have better supply situations than gaming cards. Laptop GPUs are easier to source than desktop cards.

What happens to smaller GPU companies and board partners in the long term—do any survive or adapt successfully?

Some adapt through specialization (professional workloads, regional markets), differentiation (software, customer service, vertical integration), or consolidation with larger companies. Generic board partners just adding thermal solutions to Nvidia's reference designs face extinction. Those investing in differentiation, software ecosystems, or novel approaches have survival paths. Expect the industry to have 1/3 to 1/2 as many independent players by 2027 as in 2023. The survivors will be either very large or very specialized.

Conclusion: Understanding the Gravity of the Situation

Zotac's warning wasn't hyperbole. The memory crisis is genuinely serious, and the implications ripple far beyond GPU enthusiasts checking specs online.

At its core, the crisis reflects fundamental shifts in technology markets. AI's explosion created demand that supply chains optimized for consumer gaming never anticipated. A specialized, efficient, geopolitically vulnerable supply chain that worked perfectly for gradual demand growth breaks catastrophically when demand suddenly doubles. And unlike past technology transitions, there's no obvious pivot—you can't just redesign around HBM shortage because HBM capacity is the bottleneck, and capacity takes years to expand.

The consolidation accelerating because of this crisis will be permanent. Once Nvidia establishes dominant market position and board partners disappear, getting them back requires new entrants rebuilding entire supply relationships and engineering teams from scratch. That's economically rational for new companies to avoid. The market stays consolidated.

For consumers, this means higher prices, fewer choices, and less innovation in the immediate term. For engineers and technologists, it means fewer companies competing for top talent, more concentration in major tech centers, and less room for novel approaches. For investors, it means understanding that supply chain dynamics matter more than technology quality or architectural innovation in determining who wins.

The crisis doesn't represent a fundamental problem with GPU technology. Nvidia's H100s work great. AMD's MI300 is competitive. Gaming GPUs deliver amazing performance. The problem is that supply chain realities have become the binding constraint on who can compete, not technology or engineering quality. That's a market dysfunction that usually resolves through consolidation, government intervention, or new competitors solving the constraint through vertical integration.

Zotac and other board partners are caught in the worst position: they can't solve the supply chain problem themselves, they can't compete with Nvidia's negotiating power, and they don't have the capital to invest in alternative solutions. For them, the current situation isn't just serious—it's likely terminal.

Understanding this context matters whether you're buying GPUs, investing in semiconductor companies, thinking about strategic technology decisions for your organization, or just trying to understand why GPU prices haven't fallen despite exponential performance improvements over the past few years.

The memory crisis is happening now. It'll likely persist for 18-24 months minimum. By 2027, it might ease, or it might have created market structures so consolidated that "ease" becomes permanent scarcity with Nvidia as a near-monopoly supplier. Watch this space, because it's reshaping the entire competitive landscape of computing hardware.

Key Takeaways

- Only three companies globally produce HBM (SK Hynix, Samsung, Micron), and production capacity can't match explosive AI and gaming GPU demand

- Data center GPU orders from AI companies are consuming HBM allocations, leaving consumer board partners with insufficient supply

- Independent GPU manufacturers like Zotac face existential threats because they lack negotiating power with memory suppliers compared to Nvidia

- GPU market consolidation is accelerating permanently, with dozens of board partners exiting or consolidating as supply constraints eliminate weaker competitors

- Price relief for consumer GPUs unlikely before 2026-2027, as HBM capacity expansion takes 18-24 months minimum and geopolitical risks could extend timelines further

Related Articles

- Samsung RAM Prices Doubled: What's Causing the Memory Crisis [2025]

- US Semiconductor Market 2025: Complete Timeline & Analysis [2025]

- Kioxia Memory Shortage 2026: Why SSD Prices Stay High [2025]

- Data Centers to Dominate 70% of Premium Memory Chip Supply in 2026 [2025]

- Asus Phone Exit: Why the Zenfone Era is Ending [2025]

- IT Spending Hits $1.4 Trillion in 2026: Where Money Really Goes [2025]

![GPU Memory Crisis: Why Graphics Card Makers Face Potential Collapse [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/gpu-memory-crisis-why-graphics-card-makers-face-potential-co/image-1-1769605919806.png)